ABSTRACT

Expression of human epidermal growth factor family member 3 (HER3), a critical heterodimerization partner with EGFR and HER2, promotes more aggressive biology in breast and other epithelial malignancies. As such, inhibiting HER3 could have broad applicability to the treatment of EGFR- and HER2-driven tumors. Although lack of a functional kinase domain limits the use of receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors, HER3 contains antigenic targets for T cells and antibodies. Using novel human HER3 transgenic mouse models of breast cancer, we demonstrate that immunization with recombinant adenoviral vectors encoding full length human HER3 (Ad-HER3-FL) induces HER3-specific T cells and antibodies, alters the T cell infiltrate in tumors, and influences responses to immune checkpoint inhibitions. Both preventative and therapeutic Ad-HER3-FL immunization delayed tumor growth but were associated with both intratumoral PD-1 expressing CD8+ T cells and regulatory CD4+ T cell infiltrates. Immune checkpoint inhibition with either anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 antibodies increased intratumoral CD8+ T cell infiltration and eliminated tumor following preventive vaccination with Ad-HER3-FL vaccine. The combination of dual PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA4 blockade slowed the growth of tumor in response to Ad-HER3-FL in the therapeutic model. We conclude that HER3-targeting vaccines activate HER3-specific T cells and induce anti-HER3 specific antibodies, which alters the intratumoral T cell infiltrate and responses to immune checkpoint inhibition.

KEYWORDS: Adenovirus, anti-PD-1, anti-PD-L1, HER2, HER3, immunotherapy

Abbreviations

- Ad

Adenovirus

- CTLA4

Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte-Associated Protein 4

- ECD

Extracellular domain

- EGFR

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

- ELISA

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

- ELISPOT

Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSpot

- FL

Full length

- HER3

Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 3

- HER2

Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2

- ICD

Intracellular domain

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- OS

Overall survival

- PD-1

Programmed Death Receptor 1

- PD-L1

Programmed Death Receptor Ligand 1

- TIL

Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes

Introduction

The human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER) family, consisting of HER1 (also known as EGFR), HER2, HER3, and HER4, drives the progression of many epithelial malignancies.1 EGFR and HER2 have been extensively studied as mediators of poor prognosis and are credentialed therapeutic targets of both small molecule inhibitors and monoclonal antibody therapy.2 In contrast, HER3, overexpressed in breast, lung, gastric, head and neck, and ovarian cancers and melanoma, is associated with poor prognosis,3-9 but has not been a credentialed therapeutic target, because it lacks catalytic kinase activity10-12 and is not transforming by itself. However, HER3 is thought to function as a signaling substrate for other HER proteins with which it heterodimerizes.13,14 Not only are these HER3 heterodimers potent oncogenic signaling drivers, but also they have been described as a cause of therapeutic resistance to anti-EGFR, anti-HER2, and hormonal therapies.15-19 Therefore, HER3 is an attractive therapeutic target. Although the lack of a catalytic kinase domain limits direct inhibition with small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), HER3 may be targeted with antibodies that either block binding of its ligand neuregulin-1 (NRG-1) (also called heregulin) or cause the internalization of HER3, inhibiting downstream signaling.20 Additionally, the anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody pertuzumab disrupts neuregulin-induced HER2–HER3 dimerization and signaling21; however, it is less effective at disrupting the elevated basal state of ligand-independent HER2–HER3 interaction and signaling in HER2-overexpressing tumor cells.22,23 Alternatives to monoclonal antibodies are vaccines activating antibody and T cell responses. In addition to the induction of cytolytic antigen-specific T cells, vaccines generate polyclonal antibodies that may have multiple functions including antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, complement-mediated cytotoxicity, and mediate profound receptor internalization and degradation, providing a therapeutic effect in vitro and in vivo.24

Challenges for immunotherapies, in general, and cancer vaccines in particular are host and tumor factors that limit antitumor immune responses. Among these are the interaction of CTLA4 on activated T cells and CD80/CD86 on antigen presenting cells, which limits the proliferation of antigen-specific T cells.25 Upregulation of other immune checkpoint ligands such as PD-L1 on tumor cells or infiltrating immune cells and their receptors such as PD-1 on effector T cells limit antitumor T-cell function.26 Antibodies blocking these immune checkpoint receptor-ligand interactions have improved the clinical outcome in multiple tumor types27; however, the majority of malignancies do not respond. One observation that may account for this is a requirement for pre-existing intratumoral CD8+ T cells to be negatively regulated by PD-1/PD-L1-interactions in order for tumors to regress in response to checkpoint blockade.28 We hypothesized that the activation of T cells by a vaccine against a tumor antigen would lead to increased tumor infiltration of antigen-specific T cells and the antitumor activity of these T cells would be enhanced by checkpoint blockade.

In order to activate immune responses against HER3, we generated a recombinant adenoviral vector expressing full length human HER3 (Ad-HER3-FL) and demonstrated that it elicited HER3-specific humoral and cellular immune responses in HER3-transgenic mice, thus breaking tolerance. We also developed breast cancer models expressing HER3 and demonstrated that delayed tumor progression with preventive and therapeutic vaccination was associated with an accumulation of PD-1 expressing-tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL). A combination of the Ad-HER3 vaccine with either anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 antibodies suppressed or eliminated HER3-expressing breast cancer more effectively than either alone when used in preventive models but had only a modest antitumor effect in therapeutic models. A combination of anti-CTLA4 and Ad-HER3 vaccine demonstrated a greater antitumor effect in the therapeutic model.

Results

Adenoviral vectors encoding HER3 elicit anti-HER3 T cell and antibody responses in HER3-transgenic mice

In order to develop a potent, clinically relevant vaccine to induce HER3-specific T and B cell responses, we modified the well-characterized first generation adenovirus serotype 5 vector Ad5[E1-E3-] by inserting the gene for full length human HER3 to generate a viral vector construct referred to subsequently as Ad[E1-]HER3. A recognized challenge with first generation adenoviral vectors is that pre-existing or induced neutralizing antibodies reduce their immunogenicity. Because we have previously demonstrated potent immunogenicity despite anti-vector neutralizing antibodies by using recombinant adenovirus serotype 5 vectors deleted of the early gene E2b in addition to the deletion of E1 and E3 genes (Ad5[E1-E2b-]),29 we generated an Ad5[E1-E2b-] vector expressing full length human HER3 (Ad-HER3-FL). To test the immunogenicity of this HER3 vaccine in the stringent setting where human HER3 is a self-antigen, we first developed a human HER3-transgenic mouse. Furthermore, we crossed the human HER3-transgenic mice to a BALB/c background (F1 Hybrid mice; BALB/c x MMTV-neu/MMTV-hHER3) and created a new human HER3 expressing tumor model based on the BALB/c-derived JC murine breast cancer cell line (JC-HER3).

These human HER3-transgenic mice were immunized with the Ad-HER3-FL vector following which their splenocytes were analyzed for HER3-specific cellular immune responses by the IFNγ ELISPOT assay. Fig. S1A demonstrates an equally strong cellular response against epitopes from the HER3 extracellular domain (ECD) and intracellular domain (ICD) following Ad-HER3-FL vaccination. The vaccine also induced an anti-HER3 antibody response as measured by the binding of serum polyclonal antibodies to human HER3-transfected 4T1 murine breast cancer cells (4T1-HER3) compared with antibody binding after control Ad-GFP vaccination, Fig. S1B.

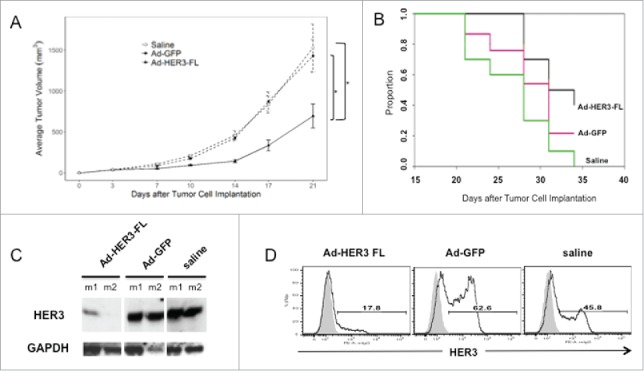

Ad-HER3 immunization reduces growth of established HER3+ breast cancer

We tested the antitumor effects of vaccination with the Ad-HER3-FL construct in therapeutic models following JC-HER3 tumor cell implantation. We found that the Ad-HER3-FL vaccine effectively suppressed JC-HER3 tumor growth compared to the controls, specifically saline (p < 0.001), and an irrelevant vaccine, Ad-GFP (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1A), and this was associated with improved survival compared to saline treatment (p = 0.005) (Fig. 1B) and demonstrated a trend toward improved survival when compared to the Ad-GFP vector, though we did not observe any tumor regression with Ad-HER3-FL vaccination.

Figure 1.

Combined JC-HER3 tumor growth and mouse survival data following treatment with Ad[E1-E2b-]HER3 vaccine. (A) Antitumor Effect: JC-HER3 tumor cells were implanted in HER3-transgenic F1 hybrid mice (5 × 105 cells/mouse) and mice were immunized on days 3 and 10 with Ad-HER3-FL, Ad[E1-E2b-]GFP (2.6 × 10E10 vp/injection) or saline. The longitudinal mixed effects model with the maximum likelihood variance estimation method was used to model tumor volume over time. Mean ± SE is shown. (Ad-HER3 FL and Ad-GFP: 15 mice/group, saline: 10 mice) *p < 0.001 (B) Effect of Ad[E1-E2b-]HER3-FL vaccine on mouse survival. JC-HER3 tumor cells were implanted in HER3-transgenic F1 hybrid mice and immunized as above in (A). Mice were considered censored at the time the tumor volume reached humane endpoint and were euthanized. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate overall survival and treatments were compared using a two-sided log-rank test. (C) Effect of Ad-HER3 vaccine on HER3 expression by JC-HER3 tumors. When tumor volume reached humane endpoint, mice were sacrificed, and tumor tissues were collected. Western blot was performed with anti-hHER3 antibody (Santa Cruz), followed by HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Cell Signaling) and chemiluminescent development. (D) Effect of Ad-HER3 vaccine on HER3 expression by flow cytometry. JC-HER3 tumors were collected and digested after a vaccine prevention model experiment and pooled by group. hHER3 expression was determined by FACS using PE-anti-hHER3 antibody. Open histograms show HER3 expression, and gray filled histograms show the staining with PE-conjugated isotype control.

In order to investigate potential sources for tumor escape from the HER3-specific immune response, we first analyzed tumor expression of HER3. In this model of HER3 immunotherapy, tumor expression of HER3 is not critical to maintaining the malignant phenotype. Therefore, one mechanism of immune escape in the presence of HER3-specific T cells and anti-HER3 antibodies would be HER3 antigen loss. We performed western blot on tumor lysates and flow cytometry on tumor cells remaining 21 d after the first vaccination. As shown in Fig. 1C, tumors from mice immunized with the Ad-HER3-FL vaccine, have downregulation of HER3 expression, but it is not completely lost in all Ad-HER3-FL vaccinated mice. Similarly, on flow cytometric analysis, HER3 decreased but some HER3 expression persisted after Ad-HER3-FL vaccination (Fig. 1D). These data demonstrate that one mechanism of escape is antigen downregulation but it is not the only explanation.

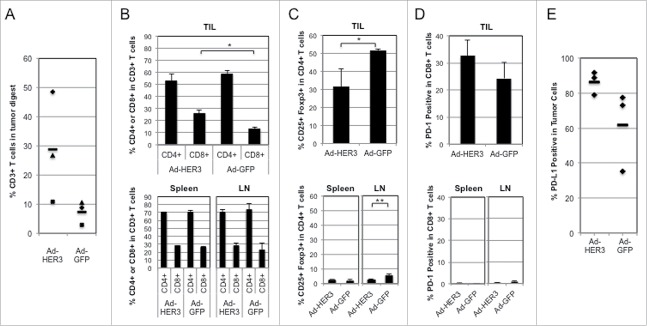

Ad-HER3-FL vaccination increases T cell infiltration into tumors

We sought to evaluate other potential explanations of tumor progression despite robust T cell responses against HER3. First, we wished to determine if there was T cell infiltration of tumor by analyzing TIL in all vaccinated mice and found a greater number of CD3+ TILs in Ad-HER3-FL immunized mice compared to the Ad-GFP immunized mice (Fig. 2A). Among these TILs, there was a greater percentage of CD8+ (p < 0.05) but not CD4+ TILs in the Ad-HER3-FL immunized mice. In contrast, there was no difference in the CD4+ and CD8+ T cell content within splenocytes or distant (non-tumor draining) lymph nodes in these Ad-HER3-FL vaccinated mice (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Analysis of tumor-infiltrating T cells in comparison with splenocytes and lymph node cells. HER3-transgenic mice bearing JC-HER3 tumor and immunized with either Ad-HER3-FL or Ad-GFP were euthanized, and tumors, spleen, and lymph nodes were collected from each mouse. Tumors were digested and tumor cells were stained with viability dye and anti-CD3, CD4+, CD8+, PD-1, and PD-L1 antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) CD3+ T cells as a percentage of total cells in the tumor digest. Percentage of T cells from the tumor of each mouse. Bars show the mean. (B) CD4+ and CD8+ T cell population in tumors, spleen, and lymph nodes. Bars represent mean +/− SD percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ cells in CD3+ T cell population for each site. *p < 0.05. (C) CD25+FOXP3 cells in tumor, spleens, and lymph nodes. Bars represent mean +/− SD percentages of CD25+FOXP3+ cells in CD4+ T cell population for each site. Student's t test: *p = 0.026 and **p = 0.008. (D) PD-1 expression by T cells in tumors, spleens, lymph nodes, and tumors. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from each site were analyzed for their expression of PD-1 by flow cytometry. Bars represent mean +/− SD for n = 3 mice. (E) PD-L1 expression by tumor cells after Ad-HER3-FL or Ad-GFP vaccination. Expression of PD-L1 by tumor cells were analyzed for each mouse treated with Ad-HER3-FL or Ad-GFP vaccine and shown as percentage. Bars show the mean.

Other proposed mechanisms for immunosuppression involve the presence of regulatory T cells (Treg). We noted fewer intratumoral Tregs in the Ad-HER3-FL vaccinated mice compared to the Ad-GFP treated mice, p = 0.026 (Fig. 2C), resulting in a greater intratumoral CD8+ to Treg ratio (data not shown). These data suggest that the immunosuppression did not involve activation of Tregs by the vaccine. Another well-established immunosuppressive mechanism is the presence of PD-1 on activated T cells.

The analysis of PD-1 expression on TILs, splenocytes, and distant (non-tumor draining) lymph nodes after Ad-HER3-FL or Ad-GFP vaccination confirmed that PD-1 tended to be overexpressed by CD8+ TILs after Ad-HER3-FL vaccination compared to PD-1 expression by CD8+ T cells isolated from splenocytes and non-tumor draining lymph nodes in these same mice (Fig. 2D). Similarly, we noted a trend for higher tumor cell PD-L1 expression after Ad-HER3-FL vaccination compared to control, Fig. 2E. These data suggest that activated TILs induced by Ad-HER3-FL vaccination are at risk of being suppressed through the PD-1/PD-L1 signaling axis due to both tumor PD-L1 expression and their own high PD-1 expression.

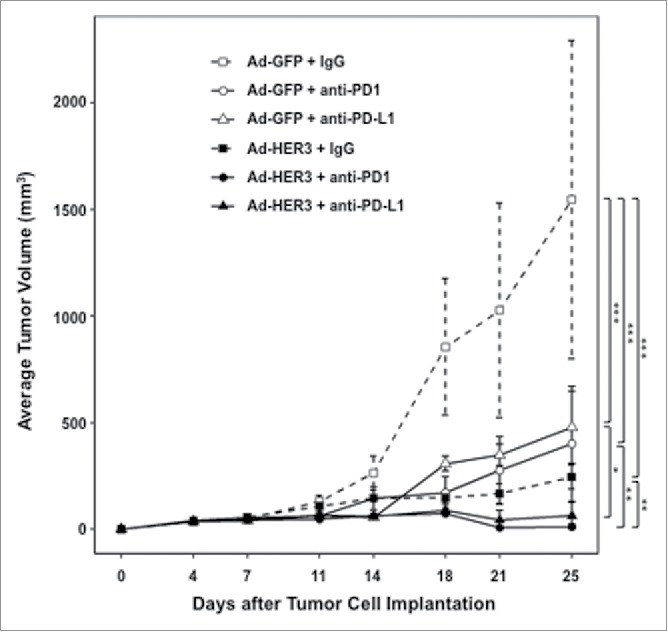

Enhanced antitumor activity with checkpoint blockade plus Ad-HER3 vaccine

In order to study the functional consequences of PD-1 expression by intratumoral T cells, we tested whether blockade of the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction in combination with Ad-HER3-FL immunizations would have greater antitumor efficacy than either alone. We first evaluated this effect in a tumor prevention model. In this model, mice were first immunized with the Ad-HER3-FL vaccine, tumor was then implanted, and tumor implantation was followed by anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 antibody administration. While Ad-HER3-FL alone or anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 with control vector resulted in some delayed tumor growth, there was no tumor regression (Fig. 3). In contrast, vaccination with Ad-HER3-FL prior to tumor implantation followed by either anti-PD-L1 or anti-PD-1 antibodies after tumor implantation induced tumor regression (p < 0.01 for the comparison of Ad-HER3-FL + IgG versus Ad-HER-FL + anti-PD1; p < 0.01 for the comparison of Ad-HER3-FL + IgG vs. Ad-HER3-FL + anti-PD-L1).

Figure 3.

Antitumor effect of Ad-HER3-FL vaccine and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in HER3 transgenic mice bearing JC-HER3 tumors. Tumor growth inhibition in a prevention model. HER3-transgenic mice were vaccinated with Ad-HER3-FL (2.6 × 1010 vp/mouse) on days -11 and -4 and then implanted with JC-HER3 cells (0.5 × 106 cells/mouse) in the flank on day 0. Mice received intraperitoneal injections of anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 antibody (200 µg/injection) on days 3, 6, 10, 13, 17, and 20. Mean ± 2SE is shown. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

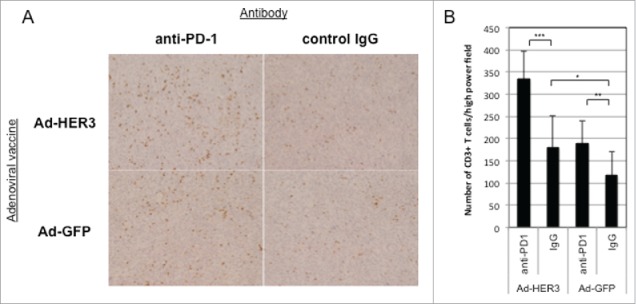

We next wanted to determine whether tumor regression was due to the modulation of the intratumoral T cell infiltrate by checkpoint blockade after vaccination in the prevention model. The addition of anti-PD-1 antibodies to Ad-HER3-FL vaccination significantly increased the number of CD3+ T cells/hpf within the tumor compared to Ad-HER3-FL vaccination alone (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4A and B). Interestingly, there was an increase in the T cell infiltrate caused by anti-PD-1 antibody treatment regardless of whether the anti-PD-1 antibody was administered with either Ad-HER3-FL or Ad-GFP. However, the combination of Ad-HER3-FL plus anti-PD-1 antibody induced the greatest T cell infiltrate/hpf.

Figure 4.

Enhanced T cell infiltration into JC-HER3 tumors in mice treated with Ad-HER3-FL vaccine and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. JC-HER3 tumors from mice immunized with HER3 or control vaccine and treated with/without PD-1/PD-L1 blockade were analyzed for CD3+ T cell infiltration by immunohistochemistry. (A) Increased CD3+ T cell infiltration with Ad-HER3-FL and anti-PD-1 therapy. High power fields were selected randomly at magnification of x200, and 10 fields that did not include necrotic area were evaluated. Representative high power fields of tumor sections for each group are shown. (B) Highest CD3+ T cell infiltration with combination of Ad-HER3-FL and anti-PD-1 therapy. Two independent observers counted the number of CD3+ T cells in the fields, and the average of 10 fields for each group were shown. Error Bar: SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.0001.

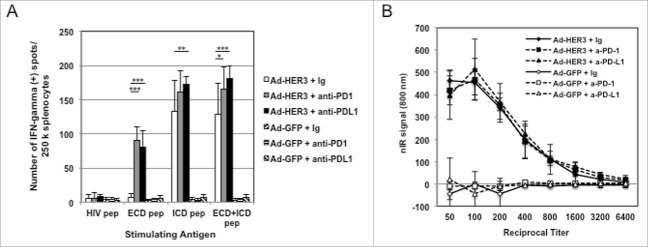

We next interrogated if anti-PD-1 treatment could augment the magnitude of both the HER3-specific T cell and anti-HER3 antibody response induced by Ad-HER3-FL alone. In the prevention model, splenocytes from mice treated with either the Ad-HER3-FL vaccine, Ad-HER3-FL vaccine + anti-PD-1 antibody, or Ad-HER3-FL vaccine + anti-PD-L1 antibody demonstrated an increased frequency of T cells specific for HER3 ECD and ICD peptides (Fig. 5A). However, neither anti-PD-1 nor anti-PD-L1 antibodies given with control vaccine affected the serum titer of anti-HER3 antibodies induced by Ad-HER3-FL-immunization (Fig. 5B). These data support a role for PD-1/PD-L1 blockade as an additional strategy to further increase antigen-specific T cell activation induced by Ad-HER3-FL vaccination.

Figure 5.

Immune responses induced by combination of Ad-HER3-FL vaccine and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. (A) HER3-specific Cellular Immune Response. HER3-transgenic mice were immunized with Ad-HER3-FL or Ad-GFP and tumor was implanted followed by anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 antibody therapy. At day 25, when mice were euthanized, an IFNγ ELISPOT assay was performed with splenocytes from individual mice (n = 3 mice per group). HER3 ECD, HER3 ICD, and ECD+ICD peptide pool were used as stimulating antigens. Bars represent the number of spots (representing IFNγ secreting T cells) +/− SD. p-value: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. (B) Anti-HER3 Humoral Immune Response. When mice were euthanized on day 25, blood was collected from individual mice (n = 3 mice per group), and a cell-based ELISA was performed using the serum. Sera from immunized mice were applied at serial dilutions of 1:50 to 1:6,400. nIR-conjugated secondary antibody was added at 1:2,000 dilution. nIR signals were detected by the LI-COR Odyssey imager at 700 nm channel. The average of difference of nIR signals between the 4T1-HER3 wells and 4T1 wells are shown.

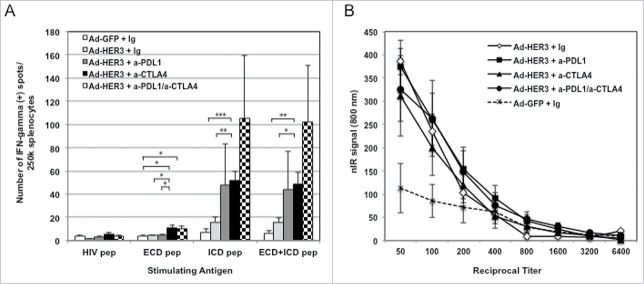

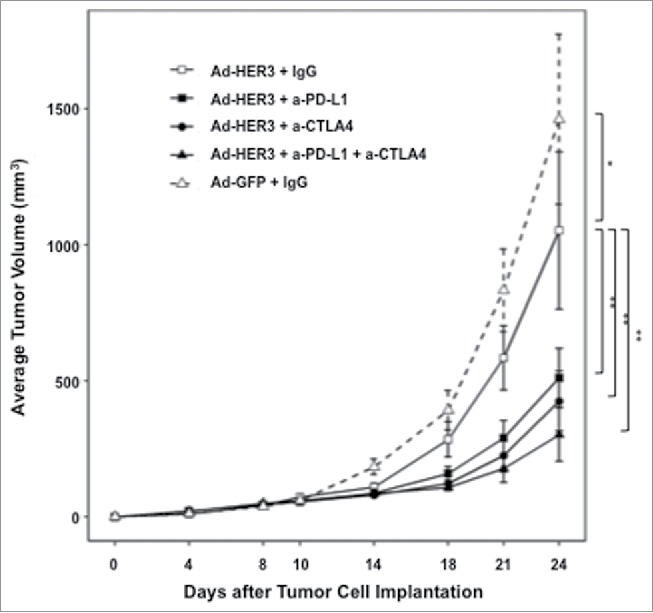

Combination of checkpoint blockade and Ad-HER3-FL has enhanced antitumor activity in tumor bearing mice

Having demonstrated that checkpoint blockade enhanced the antitumor activity of the Ad-HER3-FL in the less stringent prevention model, we wished to evaluate the efficacy of these antibodies in enhancing the antitumor activity of Ad-HER3-FL immunization in tumor-bearing mice (treatment model). We focused on anti-PD-L1 and anti-CTLA4 in these experiments. HER3 transgenic mice implanted with JC-HER3 cells were vaccinated with Ad-HER3-FL or control Ad-GFP simultaneously with anti-PD-L1, anti-CTLA4 or both. There was slowing of tumor growth by Ad-HER3-FL plus either antibody alone (p < 0.001, for both comparisons) or with the combination of both antibodies (p < 0.001) compared with Ad-HER3-FL alone (Fig. 6). Analysis of splenocytes from this experiment suggested that anti-PD-L1 or anti-CTLA4 or their combination plus the HER3 vaccine increased the magnitude of HER3-specific T cell response compared with vaccine alone (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, there was no apparent difference in the titer of antibodies induced with Ad-HER3 vaccine with or without the addition of the checkpoint antibodies (Fig. 7B).

Figure 6.

Tumor growth inhibition improved with sequential Ad-HER3 vaccination followed by immune checkpoint blockade. HER3 transgenic mice were implanted with JC-HER3 cells (0.5 × 106 cells/mouse) in the flank on day 0, and then vaccinated with Ad-HER3-FL or control Ad-GFP (2.6 × 1010 vp/mouse) on days 3 and 10. Mice received intraperitoneal injection of anti-PD-L1 antibody and/or anti-CTLA4 antibody or control IgG (200 µg/injection) twice a week (on days 3, 7, 10, 14, 17, and 21). Mean ± 2SE is shown. *p < 0.005, **p < 0.001

Figure 7.

Immune responses induced by combination of Ad-HER3-FL vaccine and either PD-1/PD-L1 blockade or CTLA4 blockade. (A) Anti-HER3 Cellular Immune Response: IFNγ ELISPOT assay was performed using splenocytes collected at the euthanasia of mice. HER3 ECD, HER3 ICD, or mixture of ECD and ICD peptide pool were used as stimulating antigens. HIV peptide pool was used as negative control. Numbers of spots in medium alone (no stimulating antigen) were subtracted and shown. Error bars: SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005. (B) Anti-HER3 Humoral Immune Response: Cell-base ELISA for anti-HER3 antibody was performed using mouse serum collected at the euthanasia of mice. Titrated mouse sera were added to 4T1 cell-coated 96-well plate or 4T1-HER3 cell-coated 96-well plate. After incubation, nIR-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody was added. nIR signals were detected by the LI-COR Odyssey imager at 700 nm channel. The average of difference of nIR signals between the 4T1-HER3 wells and 4T1 wells are shown.

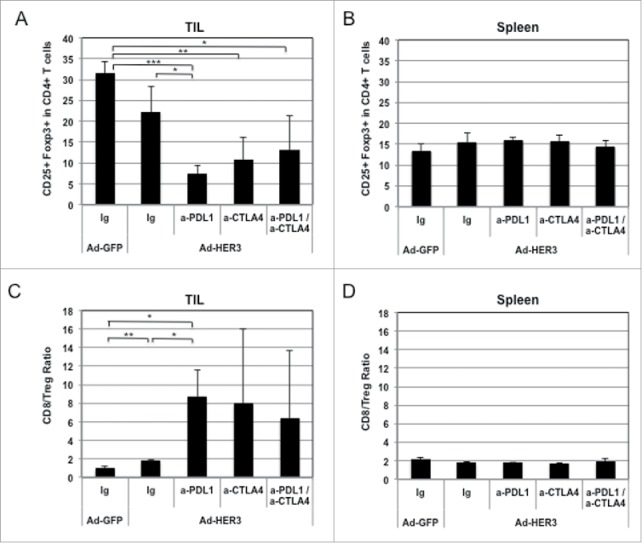

Furthermore, each antibody and their combination when administered with the Ad-HER3-FL vaccine decreased the intratumoral Treg content (Fig. 8A) and increased the CD8+ to Treg ratio (Fig. 8C) in established tumors compared with Ad-HER3-FL alone. In contrast, there was no significant difference in the splenic Treg content (Fig. 8B) or the CD8+ to Treg ratio (Fig. 8D) when comparing the different treatment conditions, suggesting that the effect of the checkpoint antibodies occurs at the site of the tumor.

Figure 8.

Effect of Ad-HER3-FL vaccine and checkpoint inhibitors on T cell subpopulations in spleens and tumors of vaccinated mice. (A) Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) were isolated from tumor tissues. Percentages of CD25+ Foxp3+ in CD4+ T cells in TILs. (B) Spleens were harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry assay. Percentages of CD25+ Foxp3+ in CD4+ T cells in splenocytes. (C) CD8+/Treg ratio in tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) are shown. (D) and CD8+/Treg ratio in splenocytes. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Discussion

HER3 mediates resistance to EGFR-, HER2-, and endocrine-directed therapies in breast cancer and other epithelial malignancies but has been challenging to target. Our initial objective was to develop a vaccine capable of inducing HER3-specific immune effectors, which would have antitumor efficacy against resistant tumors. We chose an adenoviral backbone deleted of the E1 and E2b genes that we previously demonstrated in clinical studies to activate immune responses against the encoded transgene despite the development of anti-Ad neutralizing antibody.30 We developed a model of human HER3 expressing murine breast cancer (JC-HER3) implantable into immune competent human HER3 transgenic mice to test the adenoviral vaccines. The E1, E2b-deleted vector induced T cells with specificities against both intracellular and ECDs of HER3 in HER3-transgenic mice. The Ad-HER3 vaccine also demonstrated the ability to modulate the immune cell content of tumors. Specifically, Ad-HER3 vaccination resulted in an increased percentage of intratumoral CD8+ T cells and a decreased percentage of intratumoral Tregs, yielding an increased CD8+ to Treg ratio, a trend favorable for inducing immune mediated antitumor activity. This resulted in a delay in tumor growth; however, we wished to develop a strategy that led to greater tumor regression.

One strategy to enhance the antitumor activity of the vaccine was suggested by the observation that although the Ad-HER3-FL immunization caused an increase in TILs compared to control immunizations, these TILs demonstrated high expression of PD-1 compared with splenocytes or T cells from non-tumor draining lymph nodes. It has been previously suggested that T cells specific for a vaccinating antigen upregulate PD-1.30,31 As the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction is well established to impair T cell-mediated antitumor activity, we sought to enhance the antitumor activity of the Ad-HER3-FL vaccine by blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction. Indeed, there was the elimination of tumor when we immunized mice with the Ad-HER3-FL prior to tumor implantation and then delivered the anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 antibody after tumor implantation. In this setting, there was sufficient time to generate a robust intratumoral antigen-specific immune response that could be further enhanced by checkpoint blockade. The robust immune response generated by vaccination before tumor cell implantation may model the clinical scenario of the vaccination of patients with resected tumors at high risk of recurrence. In this setting if tumor were to recur, anti-PD-1/PD-L1 blockade may lead to tumor regression because of the presence of intratumoral T cells activated by previous vaccination. This may also model the clinical scenario of tumors controlled by standard therapy, which then grow upon the development of resistance due to upregulation of molecules such as HER3. In this setting, tumors that upregulate HER3 and contain infiltrates with HER3-specific T cells would be rapidly eliminated upon application of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade.

In contrast to the prevention model, vaccination therapies of established malignancies have had modest success in pre-clinical and clinical testing; as other groups have reported greater antitumor activity for vaccines combined with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in murine treatment models,32-34 we wished to test the administration of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade with Ad-HER3-FL in established tumors. In the stringent treatment models, there was slowing of tumor growth with either PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. We reasoned that in treatment models, there would be little time for a T cell response following vaccination alone to achieve a frequency necessary to eradicate tumor. Therefore, we also tested the addition of anti-CTLA4 to determine if this alone or in conjunction with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade could cause rapid T cell expansion after vaccination.

In poorly immunogenic tumor models, it has been demonstrated that anti-CTLA4 therapy strongly enhances the amplitude of vaccine induced antitumor activity.35,36 We observed in the treatment model that anti-CTLA4 or blockade of the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction (anti-PD-L1) and their combination plus the Ad-HER3 vaccine similarly enhanced immune-mediated tumor control.

Our data suggest that current cancer vaccine strategies would be enhanced by checkpoint blockade. Single and dual checkpoint blockade appear to enhance antitumor response to the Ad-HER3 vaccine similarly. Therefore, the choice of checkpoint antibody may depend more on their indication. For example, if single agent checkpoint blockade is the standard therapy for a malignancy where HER3 would also be relevant (e.g., triple negative breast cancer), then combining the HER3 vaccine with the standard single agent checkpoint blockade antibody would be appropriate. However, where dual checkpoint is the standard, our data suggest that this leads to similar enhancement in antitumor activity to the HER3-FL vaccine.

Our data now warrant clinical testing of the Ad-HER3-FL vaccine with anti-PD-1/PD-L1, anti-CTLA4 therapy, or both in the setting of established malignancy and with anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 antibodies in the adjuvant setting. As our pre-clinical testing has demonstrated minimal side effects from this vaccine, we anticipate that our planned first-in-human clinical trial of this vaccine will be well tolerated. A phase I study of the Ad-HER3 full-length vaccine will open shortly in order to evaluate the safety and immunogenicity of this vaccine in metastatic cancer patients with a planned expansion cohort for hormone receptor positive breast cancer. As HER3 is recognized to mediate anti-HER2 therapy resistance, we plan to open a clinical trial of the Ad-HER3 vaccine given in combination with anti-HER2 therapy in metastatic HER2+ breast cancer. Our prior studies have also revealed that in HER2+ breast cancer, activation of the HER3 signaling axis is associated with a poor outcome.37 Lastly, there is increasing evidence that single agent check point blockade is clinically active in a portion of TNBC patients.38 In addition, there is evidence that HER3 expression is associated with worse DFS and OS in TNBC.39 Based on these observations, we will open a trial of concurrent Ad-HER3 vaccination and check point blockade in TNBC to assess the safety and immunogenicity of this combination therapy.

Materials and methods

Adenoviral vector preparation

The human HER3 cDNA was excised from a pCMVSport6-HER3-HsIMAGE6147464 plasmid (cDNA clone MGC:88033/IMAGE:6147464) from the ATCC (Manassas, VA). Construction of a first-generation [E1-, E3-] Ad vector containing human full length HER3 under control of human CMV promoter/enhancer elements was performed using the pAdEasy system (Agilent technologies, Santa Clara, CA) as previously described.40 The modified adenoviral vector, [E1-,E2b-] Ad, was constructed as previously described.41 This vector has multiple deletions of the early region 1 (E1) and E2b regions (DNA polymerase and pTP genes) and was engineered to express the identical human CMV promoter/enhancer-transgene cassette as utilized for the [E1−E3−] Ad-HER3 vector. Ad[E1-E2b-]-HER3 FL vector was constructed with the full length of HER3 cDNA. Complementing C-7 cell lines were used to support the growth and production of high titers of these vectors, and cesium chloride double banding was performed to purify the vectors, as previously reported.42

Reagents and peptides

Mixtures of HER3 peptides containing 15mer peptides, each overlapping the next by 11 amino acids, spanning ECD plus transmembrane segment (ECD-TM) of HER3 protein and ICD of HER3 protein, were purchased from JPT Peptide Technologies (Berlin, Germany), and were used for the IFNγ ELISPOT assay. An HIV peptide mix representing HIV gag protein was purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA) and was used as a negative control. Anti-murine PD-1 (BE0146, clone J43) and anti-murine PD-L1 (BE0101, clone 10F.9G2) and anti-murine CTLA4 (BE0164, clone 9D9) monoclonal antibodies were purchased from Bio X Cell (West Lebanon, NH) for animal experiments. Collagenase III (cat# 4183) was purchased from Worthington Biochemical (Lakewood, NJ), and hyaluronidase (H3884) and DNase (D5025) from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Mice

Female wild-type BALB/c mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were bred and maintained in the Duke University Medical Center pathogen-free Animal Research Facility, and used at 6 to 8 weeks of age. Human HER3-transgenic mice (MMTV-neu/MMTV-hHER3) with FVB background were a kind gift from Dr. Stan Gerson at Case Western Reserve University. FVB mice homozygous for the HER3 gene were established at Duke University and crossed with BALB/c mice to generate F1 hybrid HER3 transgenic mice (FVB x BALB/c) for use in tumor implantation experiments. All animal studies described were approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee and the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (USAMRMC) Animal Care and Use Review Office (ACURO) and performed in accordance with guidelines published by the Commission on Life Sciences of the National Research Council.

Detecting HER3 expression by western blotting

Tumor tissues were collected at the termination of animal experiments and minced and homogenized in RIPA buffer in the presence of proteinase inhibitors. After centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatant was pooled, filtered through a 0.22 μm filter, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C until needed. Protein concentration was determined by a BCA assay. Thirty µg of protein was applied for each lane, run on 12% Tris-HCl acrylamide gel, and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. Membranes were incubated with anti-HER3 antibody (1:1,000 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) or anti-GAPDH antibody (1:1,000 dilution, Santa Cruz) for 1 h, followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:2,000 dilution, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The chemiluminescent substrate kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) was used for the development.

Flow cytometry of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes and tumor HER3 expression

Tumors were excised from mice at the termination of tumor implantation experiments, minced with surgical blades, and digested with triple enzyme buffer (collagenase III, hyaluronidase, DNase) for 1.5 h at 37°C. The cell suspension was washed three times with PBS and resuspended in PBS. Cells were first labeled with viability dye (Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain Kit, Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) for 5 min, and then with PerCP/Cy5.5-anti-CD3, APC/Cy7-anti-CD8+, Alexa Fluor 700-anti-CD4+, FITC-anti-CD25, APC-anti-PD-1, and PE-anti-PD-L1, or PE-anti-HER3 antibody (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were washed twice with PBS and analyzed on a LSRII machine (BD Biosciences) using FlowJo software.

IFNγ enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISpot) assay

Mouse IFNγ ELISPOT assay (Mabtech Inc., Cincinnati, OH) was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. At the end of the mouse experiments, their spleens were collected and lymphocytes were harvested by mincing and passing through a 40 µm Cell Strainer. Red blood cells were lysed with red blood cell lysis buffer (Sigma). Splenocytes (500,000 cells/well) were incubated in RPMI-1640 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% horse serum, and HER3 ECD-TM peptide mix and/or HER3 ICD peptide mix (1.3 µg/mL) were used as stimulating antigens. HIV peptide mix was used as a negative control, and a mixture of PMA (50 ng/mL) and Ionomycin (1 µg/mL) was used as a positive control for the assay. Membranes were read with a high-resolution automated ELISpot reader system (Carl Zeiss, Inc., Thornwood, NY, USA) using the KS ELISpot version 4.2 software.

Cell-based ELISA

4T1 cells were transduced with HER3 gene by lentiviral vectors to express human HER3 on the cell surface (4T1-HER3 cell). 4T1 and 4T1-HER3 cells were incubated overnight at 37°C in 96 well flat bottomed plates (3 × 104 cells in 100 µL medium/well). Mouse sera were prepared by diluting with DMEM medium (final titrations 1:50–1:6,400), and 50 µL of mouse sera-containing media were added to the wells and incubated for 1 h on ice. The plates were gently washed with PBS twice, and then, cells were fixed with diluted formalin (1:10 dilution of formalin in 1% BSA in PBS) for 20 min at room temperature. After washing three times with PBS, 50 µL of 1:2,000 diluted HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG was added to the wells, and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. After washing three times with PBS, TMB substrate was added to the wells (50 µL/well) and incubated for approximately 20 min. The color development was stopped by adding 50 µL of 1M H2SO4 buffer. Absorbance at 450 nm was read using a BioRad Microplate Reader (Model 680). As the alternative method for the detection of HER3-specific antibody, near infrared red (nIR) dye-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (IRDye 800CW, LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) was used as a secondary antibody, and the nIR signal was detected by a LI-COR Odyssey Imager (LI-COR) using the 800 nm channel.

Prophylactic antitumor model in HER3-transgenic mice

HER3-transgenic F1 hybrid mice were immunized by footpad injection on days −11, −4, and 14 with 2.6 × 1010 particles of the Ad[E1-,E2b-]-HER3-FL or Ad-GFP control in 40 μL of saline. On day 0, mice were inoculated with 5 × 105 JC-HER3 cells in 100 μL saline subcutaneously into the flank. Tumor dimensions were measured serially, and tumor volumes calculated using the following formula: long axis × (short axis)2 × 0.5. For the combination treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors, mice were vaccinated with Ad-HER3-FL or Ad-GFP on days −11, −4, and 14, and received peritoneal injection of anti-PD-1 antibody, anti-PD-L1 antibody, or control IgG (200 µg/injection) twice a week (on days 3, 6, 10, 13, 17, and 20) after tumor implantation.

Therapeutic antitumor model in F1 hybrid HER3 transgenic mice

HER3 transgenic F1 hybrid mice were inoculated with 5 × 105 JC-HER3 cells in 100 μL saline subcutaneously into the flank on day 0. On days 3 and 10, mice were immunized via footpad injection with Ad-HER3-FL or Ad-GFP control vector (2.6 × 1010 particles/mouse for each injection). Tumor dimensions were measured serially and tumor volumes were calculated as described above. Mice were euthanized when the tumor size reached the humane endpoint, or by day 34. For the combined treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors (anti-PD-1, anti-PD-L1, or anti-CTLA4 antibody), mice received peritoneal injection of the checkpoint inhibitor (200 µg/injection) twice a week after tumor implantation.

Tissue analysis of tumor-infiltrating T cells

Tumor tissue collected at the time mice were euthanized was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for a minimum of 24 h. The tissue was then processed and embedded in paraffin. Sections with 5 µm thickness were made for hemotoxylin and eosin staining and CD3+ T cell staining. For immunohistochemistry using anti-CD3 antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), heat-induced antigen retrieval was performed using sodium citrate buffer for 20 min after deparaffinization of tissue sections. Following quenching of endogenous peroxidase activity with 3% H2O2, 10% normal horse serum was used to block nonspecific binding sites. Anti-CD3 antibody (1:150 dilution) was applied to the sections, which were incubated overnight at 4°C. After three washes with PBS, anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (ImmPRESS anti-Rabbit IgG Polymer, Vector Lab, Burlingame, CA) was applied for 30 min, and then color was developed using the DAB Peroxidase substrate kit (Vector Lab). Counterstaining was performed with hematoxylin. After assessment of adequate staining by two independent observers, 10 high power fields (magnification x200; objective lens x20, ocular x10) of tumor tissue for each group, avoiding necrotic area, were randomly selected and photographed using an IX73 Inverted Microscope with Dual CCD Chip Monochrome/ Color Camera (Olympus). CD3-positive spots were counted for each field by two observers who had no previous knowledge of treatments performed for individual groups.

Statistical analysis

For the ELISpot and ELISA assays, differences in IFNγ production and antibody binding, respectively, were analyzed using the Student's t-test. Tumor volume measurements for in vivo models were analyzed under a cubic root transformation to stabilize the variance. Welch t-tests were used to assess differences between mice injected with HER3-VIA or control GFP-VIA.

To compare tumor growth volumes over time, a multivariable Generalized Additive Model for Location, Scale and Shape (GAMLSS)43 considering Group, Experiment, Time and interaction between Time and Group as covariables for Tumor Volume location and Time for Tumor Volume scale was applied. The Normal distribution was considered for the effectiveness of Ad-HER3 FL vaccine model and the Zero Adjusted Gamma distribution for the effectiveness of antibodies model. Time was modeled using penalized cubic spline44 and the interaction between Time and Group was modeled using Varying Coefficient.45 Areas under tumor growth curve were calculated under spline interpolation43 and adaptive quadrature for the tumor prevention model. A simple GAMLSS with Gamma distribution quantifies the relationship between mean of area under tumor growth curve and the covariable Group.

Contrasts were calculated using the Wald statistic and multiples comparisons were corrected as suggested by Holm.46 Model diagnostics was performed based on Worm-plots47 and fitted values were compared considering 95% Bootstrap Confidence Intervals.48

The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate overall survival and treatments were compared using a two-sided log-rank test. Analyses were performed using R version 2.10.1, SAS v. 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary NC) and R version 3.2.5,49 survival plots were created using Spotfire S+ v. 8.1 (TIBCO, Palo Alto, CA). All tests of hypotheses will be two-sided considering a significance level of 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program Clinical Translational Research Award [W81XWH-12-1-0574 to HKL].

References

- 1.Roskoski R., Jr The ErbB/HER family of protein-tyrosine kinases and cancer. Pharmacol Res 2014; 79:34-74; PMID:24269963; https://doi.org/20850557 10.1016/j.phrs.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cai Z, Zhang H, Liu J, Berezov A, Murali R, Wang Q, Greene MI. Targeting erbB receptors. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2010; 21(9):961-6; PMID:20850557; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takikita M, Xie R, Chung JY, Cho H, Ylaya K, Hong SM, Moskaluk CA, Hewitt SM. Membranous expression of Her3 is associated with a decreased survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Transl Med 2011; 9:126; PMID:21801427; https://doi.org/ 10.1186/1479-5876-9-126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiu CG, Masoudi H, Leung S, Voduc DK, Gilks B, Huntsman DG, Wiseman SM. HER-3 overexpression is prognostic of reduced breast cancer survival: A study of 4046 patients. Ann Surg 2010; 251(6):1107-16; PMID:20485140; https://doi.org/ 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181dbb77e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayashi M, Inokuchi M, Takagi Y, Yamada H, Kojima K, Kumagai J, Kawano T, Sugihara K. High expression of HER3 is associated with a decreased survival in gastric cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14(23):7843-9; PMID:19047113; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giltnane JM, Moeder CB, Camp RL, Rimm DL. Quantitative multiplexed analysis of ErbB family coexpression for primary breast cancer prognosis in a large retrospective cohort. Cancer 2009; 115(11):2400-9; PMID:19330842; https://doi.org/ 10.1002/cncr.24277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Begnami MD, Fukuda E, Fregnani JH, Nonogaki S, Montagnini AL, da Costa WL Jr., Soares FA. Prognostic implications of altered human epidermal growth factor receptors (HERs) in gastric carcinomas: HER2 and HER3 are predictors of poor outcome. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29(22):3030-6; PMID:21709195; https://doi.org/ 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.6313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reschke M, Mihic-Probst D, van der Horst EH, Knyazev P, Wild PJ, Hutterer M, Meyer S, Dummer R, Moch H, Ullrich A. HER3 is a determinant for poor prognosis in melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14(16):5188-97; PMID:18698037; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee CH, Huntsman DG, Cheang MC, Parker RL, Brown L, Hoskins P, Miller D, Gilks CB. Assessment of Her-1, Her-2, and Her-3 expression and Her-2 amplification in advanced stage ovarian carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2005; 24(2):147-52; PMID:15782071; https://doi.org/ 10.1097/01.pgp.0000152026.39268.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kol A, Terwisscha van Scheltinga AG, Timmer-Bosscha H, Lamberts LE, Bensch F, de Vries EG, Schröder CP. HER3, serious partner in crime: Therapeutic approaches and potential biomarkers for effect of HER3-targeting. Pharmacol Ther 2014; 143(1):1-11; PMID:24513440; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sergina NV, Rausch M, Wang D, Blair J, Hann B, Shokat KM, Moasser MM. Escape from HER-family tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy by the kinase-inactive HER3. Nature 2007; 445(7126):437-41; PMID:17206155; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nature05474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frogne T, Benjaminsen RV, Sonne-Hansen K, Sorensen BS, Nexo E, Laenkholm AV, Rasmussen LM, Riese DJ 2nd, de Cremoux P, Stenvang J et al. Activation of ErbB3, EGFR and Erk is essential for growth of human breast cancer cell lines with acquired resistance to fulvestrant. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009; 114(2):263-75; PMID:18409071; https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10549-008-0011-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Musgrove EA, Sutherland RL. Biological determinants of endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2009; 9(9):631-43; PMID:19701242; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nrc2713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tovey S, Dunne B, Witton CJ, Forsyth A, Cooke TG, Bartlett JM. Can molecular markers predict when to implement treatment with aromatase inhibitors in invasive breast cancer? Clin Cancer Res 2005; 11(13):4835-42; PMID:16000581; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arpino G, Wiechmann L, Osborne CK, Schiff R. Crosstalk between the estrogen receptor and the HER tyrosine kinase receptor family: Molecular mechanism and clinical implications for endocrine therapy resistance. Endocr Rev 2008; 29(2):217-33; PMID:18216219; https://doi.org/ 10.1210/er.2006-0045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu B, Ordonez-Ercan D, Fan Z, Edgerton SM, Yang X, Thor AD. Downregulation of erbB3 abrogates erbB2-mediated tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer cells. Int J Cancer 2007; 120(9):1874-82; PMID:17266042; https://doi.org/ 10.1002/ijc.22423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsieh AC, Moasser MM. Targeting HER proteins in cancer therapy and the role of the non-target HER3. Br J Cancer 2007; 97(4):453-7; PMID:17667926; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Folgiero V, Avetrani P, Bon G, Di Carlo SE, Fabi A, Nistico C, Vici P, Melucci E, Buglioni S, Perracchio L et al. Induction of ErbB-3 expression by alpha6beta4 integrin contributes to tamoxifen resistance in ERbeta1-negative breast carcinomas. PLoS One 2008; 3(2):e1592; PMID:18270579; https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0001592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frogne T, Jepsen JS, Larsen SS, Fog CK, Brockdorff BL, Lykkesfeldt AE. Antiestrogen-resistant human breast cancer cells require activated protein kinase B/Akt for growth. Endocr Relat Cancer 2005; 12(3):599-614; PMID:16172194; https://doi.org/ 10.1677/erc.1.00946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gala K, Chandarlapaty S. Molecular pathways: HER3 targeted therapy. Clin Cancer Res 2014; 20(6):1410-6; PMID:24520092; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakai K, Yokote H, Murakami-Murofushi K, Tamura T, Saijo N, Nishio K. Pertuzumab, a novel HER dimerization inhibitor, inhibits the growth of human lung cancer cells mediated by the HER3 signaling pathway. Cancer Sci 2007; 98(9):1498-503; PMID:17627612; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00553.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cai Z, Zhang G, Zhou Z, Bembas K, Drebin JA, Greene MI, Zhang H. Differential binding patterns of monoclonal antibody 2C4 to the ErbB3-p185her2/neu and the EGFR-p185her2/neu complexes. Oncogene 2008; 27(27):3870-4; PMID:18264138; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/onc.2008.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Junttila TT, Akita RW, Parsons K, Fields C, Lewis Phillips GD, Friedman LS, Sampath D, Sliwkowski MX. Ligand-independent HER2/HER3/PI3K complex is disrupted by trastuzumab and is effectively inhibited by the PI3K inhibitor GDC-0941. Cancer Cell 2009; 15(5):429-40; PMID:19411071; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ren XR, Wei J, Lei G, Wang J, Lu J, Xia W, Spector N, Barak LS, Clay TM, Osada T et al. Polyclonal HER2-specific antibodies induced by vaccination mediate receptor internalization and degradation in tumor cells. Breast Cancer Res 2012; 14(3):R89; PMID:22676470; https://doi.org/ 10.1186/bcr3204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stamper CC, Zhang Y, Tobin JF, Erbe DV, Ikemizu S, Davis SJ, Stahl ML, Seehra J, Somers WS, Mosyak L. Crystal structure of the B7-1/CTLA-4 complex that inhibits human immune responses. Nature 2001; 410(6828):608-11; PMID:11279502; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/35069118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Topalian SL, Drake CG, Pardoll DM. Immune checkpoint blockade: A common denominator approach to cancer therapy. Cancer Cell 2015; 27(4):450-61; PMID:25858804; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin DS, Ribas A. The evolution of checkpoint blockade as a cancer therapy: What's here, what's next? Curr Opin Immunol 2015; 33:23-35; PMID:25621841; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.coi.2015.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tumeh PC, Harview CL, Yearley JH, Shintaku IP, Taylor EJ, Robert L, Chmielowski B, Spasic M, Henry G, Ciobanu V et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature 2014; 515(7528):568-71; PMID:25428505; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nature13954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Osada T, Yang XY, Hartman ZC, Glass O, Hodges BL, Niedzwiecki D, Morse MA, Lyerly HK, Amalfitano A, Clay TM. Optimization of vaccine responses with an E1, E2b and E3-deleted Ad5 vector circumvents pre-existing anti-vector immunity. Cancer Gene Ther 2009; 16(9):673-82; PMID:19229288; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/cgt.2009.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fourcade J, Sun Z, Pagliano O, Chauvin JM, Sander C, Janjic B, Tarhini AA, Tawbi HA, Kirkwood JM, Moschos S et al. PD-1 and Tim-3 regulate the expansion of tumor antigen-specific CD8(+) T cells induced by melanoma vaccines. Cancer Res 2014; 74(4):1045-55; PMID:24343228; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong RM, Scotland RR, Lau RL, Wang C, Korman AJ, Kast WM, Weber JS. Programmed death-1 blockade enhances expansion and functional capacity of human melanoma antigen-specific CTLs. Int Immunol 2007; 19(10):1223-34; PMID:17898045; https://doi.org/ 10.1093/intimm/dxm091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karyampudi L, Lamichhane P, Scheid AD, Kalli KR, Shreeder B, Krempski JW, Behrens MD, Knutson KL. Accumulation of memory precursor CD8 T cells in regressing tumors following combination therapy with vaccine and anti-PD-1 antibody. Cancer Res 2014; 74(11):2974-85; PMID:24728077; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soares KC, Rucki AA, Wu AA, Olino K, Xiao Q, Chai Y, Wamwea A, Bigelow E, Lutz E, Liu L et al. PD-1/PD-L1 blockade together with vaccine therapy facilitates effector T-cell infiltration into pancreatic tumors. J Immunother 2015; 38(1):1-11; PMID:25415283; https://doi.org/ 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Binder DC, Engels B, Arina A, Yu P, Slauch JM, Fu YX, Karrison T, Burnette B, Idel C, Zhao M et al. Antigen-specific bacterial vaccine combined with anti-PD-L1 rescues dysfunctional endogenous T cells to reject long-established cancer. Cancer Immunol Res 2013; 1(2):123-33; PMID:24455752; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Elsas A, Hurwitz AA, Allison JP. Combination immunotherapy of B16 melanoma using anti-cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)-producing vaccines induces rejection of subcutaneous and metastatic tumors accompanied by autoimmune depigmentation. J Exp Med 1999; 190(3):355-66; PMID:10430624; https://doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.190.3.355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li B, VanRoey M, Wang C, Chen TH, Korman A, Jooss K. Anti-programmed death-1 synergizes with granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor–secreting tumor cell immunotherapy providing therapeutic benefit to mice with established tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15(5):1623-34; PMID:19208793; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xia W, Petricoin EF, 3rd Zhao S, Liu L, Osada T, Cheng Q, Wulfkuhle JD, Gwin WR, Yang X, Gallagher RI et al. An heregulin-EGFR-HER3 autocrine signaling axis can mediate acquired lapatinib resistance in HER2+ breast cancer models. Breast Cancer Res 2013; 15(5):R85; PMID:24044505; https://doi.org/ 10.1186/bcr3480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nanda R, Chow LQ, Dees EC, Berger R, Gupta S, Geva R, Pusztai L, Pathiraja K, Aktan G, Cheng JD et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced triple-negative breast cancer: Phase Ib KEYNOTE-012 study. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34(21):2460-7; PMID:27138582; https://doi.org/ 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.8931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bae SY, La Choi Y, Kim S, Kim M, Kim J, Jung SP, Choi MY, Lee SK, Kil WH, Lee JE et al. HER3 status by immunohistochemistry is correlated with poor prognosis in hormone receptor-negative breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013; 139(3):741-50; PMID:23722313; https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10549-013-2570-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.He TC, Zhou S, da Costa LT, Yu J, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. A simplified system for generating recombinant adenoviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998; 95(5):2509-14; PMID:9482916; https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hodges BL, Serra D, Hu H, Begy CA, Chamberlain JS, Amalfitano A. Multiply deleted [E1, polymerase-, and pTP-] adenovirus vector persists despite deletion of the preterminal protein. J Gene Med 2000; 2(4):250-9; PMID:10953916; https://doi.org/ 10.1002/1521-2254(200007/08)2:4%3c250::AID-JGM113%3e3.0.CO;2-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amalfitano A, Hauser MA, Hu H, Serra D, Begy CR, Chamberlain JS. Production and characterization of improved adenovirus vectors with the E1, E2b, and E3 genes deleted. J Virol 1998; 72(2):926-33; PMID:9444984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rigby RA, Stasinopoulos DM. Generalized additive models for location, scale and shape. J Roy Stat Soc C (Appl Stat) 2005; 54(3):507-54; https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1467-9876.2005.00510.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eilers PHC, Marx BD. Flexible smoothing with B-splines and penalties. 1996:89-121. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Varying-coefficient models. J Roy Stat Soc B (Methodol) 1993; 55(4):757-96. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat 1979; 6(2):65-70. [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Buuren S, Fredriks M. Worm plot: A simple diagnostic device for modelling growth reference curves. Stat Med 2001; 20(8):1259-77; PMID:11304741; https://doi.org/ 10.1002/sim.746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DiCiccio TJ, Efron B. Bootstrap confidence intervals. Statistical Science 1996:189-228. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Team RDC R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.