ABSTRACT

The progressive tumor microenvironment (TME) coordinately supports tumor cell expansion and metastasis, while it antagonizes the survival and (poly-)functionality of antitumor T effector cells. There remains a clear need to develop novel therapeutic strategies that can transform the TME into a pro-inflammatory niche that recruits and sustains protective immune cell populations. While intravenous treatment with tumor-primed CD4+ T cells combined with intraperitoneal delivery of agonist anti-glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor (α-GITR) mAb results in objective antitumor responses in murine early stage disease models, this approach is ineffective against more advanced tumors. Further subcutaneous co-administration of a vaccine consisting of tumor antigen-loaded dendritic cells (DC) failed to improve the antitumor efficacy of this approach. Remarkably, these same three therapeutic agents elicited significant antitumor benefits when the antitumor CD4+ T cells and tumor antigen-loaded DC were co-injected directly into tumors along with intratumoral or intraperitoneal delivery of α-GITR mAb. This latter protocol induced the production of an array of antitumor cytokines and chemokines within the TME, supporting increased tumor-infiltration by antitumor CD8+ T cells capable of mediating tumor regression and extended overall survival.

KEYWORDS: Cancer immunotherapy, tumor microenvironment, vaccine

Abbreviations

- ACT

adoptive cell transfer

- DC

dendritic cells

- GITR

glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor

- IL

interleukin

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- i.t.

intratumoral

- i.v.

intravenous

- s.c.

subcutaneous

- Th1

T helper 1

- Th2

T helper 2

- TIL

tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

- TME

tumor microenvironment

Introduction

The tumor microenvironment (TME) represents a formidable obstacle to the success of cancer immunotherapy as it concomitantly promotes tumor progression while impeding the effectiveness and durability of antitumor T cells in vivo.1,2 In this context, the development of combination immunotherapies that effectively recondition the TME to be less hostile to protective immune cells remains a major unmet clinical need.3-5

CD4+ T cells play multiple roles in regulating the immune system and/or they may act as direct antitumor effector cells.6-8 The adoptive transfer of tumor-reactive CD4+ T cells expanded in vivo or in vitro represents a promising approach for treating cancer-bearing hosts in translational models and in the clinical trial setting.9-11 GITR, a co-stimulatory receptor expressed on a broad range of immune cells including CD4+ T cells and DC,12 has been highly ranked as an interventional target for the treatment of cancer. GITR ligation achieved using an agonist α-GITR mAb has been shown to enhance spontaneous and/or therapy-induced antitumor immunity via multiple mechanisms.13-24 While either adoptive CD4+ T-cell transfer or GITR ligation alone has been shown to mediate antitumor activity when applied as therapies in “immunogenic” tumor models, neither single modality has demonstrated consistent efficacy against poorly immunogenic tumors.17,19,21 DC represent central players in the initiation, regulation and maintenance of tumor antigen-specific immune responses, and have been extensively investigated for their therapeutic potential against cancer.25 However, DC-based monotherapies have resulted in only modest benefits to cancer patients treated on clinical trials,25 providing an impetus to combine such strategies with complementary approaches (such as adoptive CD4+ T-cell transfer and GITR ligation) to improve the clinical impact of such immunotherapeutic interventions.

The murine 4T1.2-Neu breast carcinoma and B16 melanoma models share many characteristics with human cancers, including poor immunogenicity and aggressive growth in vivo.15,22,26-29 As such, effective interventional strategies defined in these translational models may portend greater clinical efficacy when applied to cancer patients. In this regard, we observed that while neither adoptive tumor-primed CD4+ T-cell transfer nor administration of a GITR agonist antibody significantly impacted early stage tumor growth, treatment of tumor-bearing mice with both agents led to a CD8+ T-cell-dependent reduction in tumor progression.21 However, this combination immunotherapy approach failed to impact the growth of more advanced tumors, suggesting the need to further modify the existing protocol in such cases.

Results from the current study suggest that combined adoptive cell transfer (ACT) using tumor-primed CD4+ T cells and α-GITR mAb enhance: (i) tumor antigen-loaded DC activation in vivo resulting in the effective cross-priming of specific CD8+ T cells systemically, and (ii) the production of cytokines and chemokines within the TME that recruit and sustain antitumor CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) that are critical to the antitumor efficacy of this immunotherapeutic approach.

Results

Tumor-primed CD4+ T cells and agonist α-GITR mAb sequentially activate DC

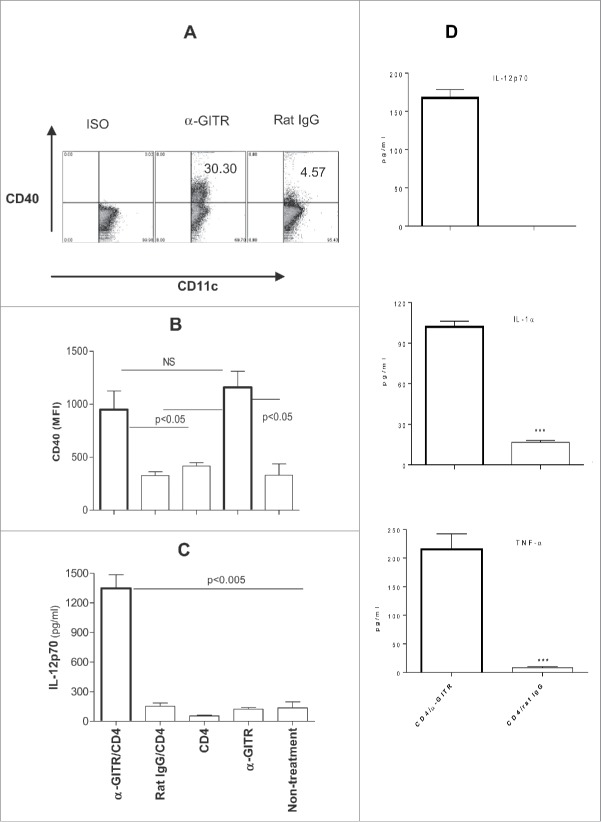

Since IFNγ is required for the immune-mediated rejection of established tumors such as 4T1.2-Neu,30 we sought preferred means by which to promote IFNγ production by antitumor T effector cells. Both DC and α-GITR mAb are competent to stimulate activated GITR+ T cells; hence, we examined the impact of these stimuli alone and in combination on IFNγ secretion from CD4+CD25− T cells isolated from tumor-bearing mice (tumor-primed CD4+ T cells). Fresh tumor-primed CD4+ T cells produced IFNγ and IL-5 (Fig. S1), suggesting they are the mixtures of Th1 and Th2. Tumor antigen (lysate)-loaded DC and α-GITR mAb were each capable of promoting enhanced IFNγ production from responder CD4+ T cells (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, stimulation of CD4+ T cells using both tumor antigen-loaded DC and α-GITR mAb led to the synergistic production of IFNγ in vitro (Fig. 1A). While tumor antigen-loaded DC were shown to constitutively express GITR, co-culture with tumor-primed CD4+ T cells led to an upregulation in expression of GITR on DC (Fig. 1B), potentially enhancing DC responsiveness to activation by the agonist α-GITR mAb.

Figure 1.

(A) In vitro GITR ligation enhances IFNγ production by tumor-primed CD4+ T cells in the presence of tumor antigen-loaded DC. BALB/c mice were inoculated with 4T1.2-Neu. After 9–21 d, tumor-primed CD4+ T cells were cultured alone, in the presence of α-GITR mAb, or co-cultured with 4T1.2-Neu lysate-loaded naive splenic CD11c+DC in the presence or absence of α-GITR mAb for 2 d. The concentration of IFNγ in the culture supernatants was determined by ELISA. Data represents three independent experiments and were statistically analyzed. (B) In vitro tumor-primed CD4+ T cells upregulates GITR expression on TDLN DC. TDLN DC were cultured alone (none) or with tumor-primed CD4+ T cells (CD4+) for 2 d and subsequently stained with α-CD11c and α-GITR or ISO and analyzed by flow cytometry. GITR expression on gated CD11c+ DC is shown in one representative of three experiments with similar results obtained.

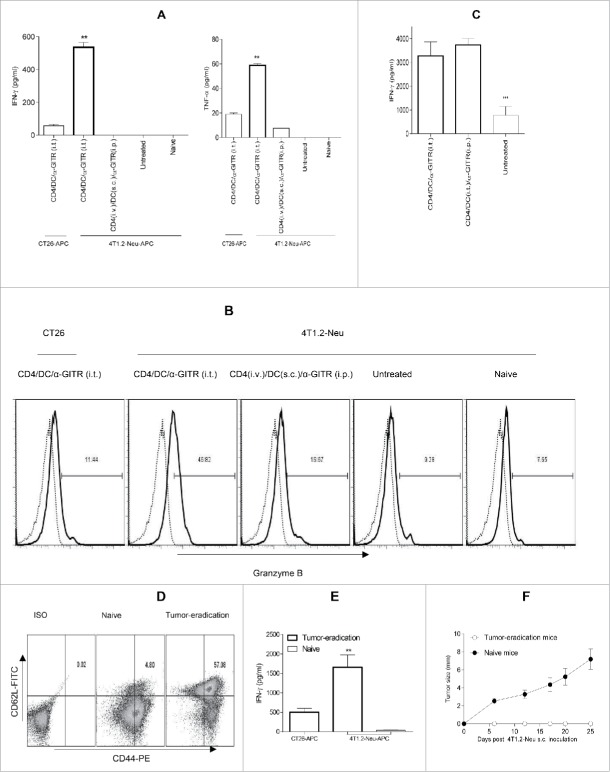

To further determine the impact of GITR ligation on DC in vivo, tumor-bearing mice were treated with tumor-primed CD4+ T cells +/− agonist α-GITR mAb. Treatment with α-GITR mAb led to increased expression of CD40 on tumor draining LN (TDLN) DC (Fig. 2A and B); however, monotherapy using either α-GITR mAb or tumor-primed CD4+ T cells did not result in DC production of IL-12p70 in situ (Fig. 2C). Notably, a combined treatment with both agents led to elevated production of IL-12p70 by TDLN DC in vivo (Fig. 2C) and to augmented production of IL-12p70, TNF-α and IL-1α by tumor antigen-loaded DC in vitro (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, while IL-12p70 production from activated DC is typically transient,31 we observed extended (up to 3 d) production of this Type-1 cytokine from TDLN DC isolated from CD4/α-GITR Ab-treated mice (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that tumor-primed CD4+ T cells and α-GITR mAb coordinately promote prolonged Type-1 DC function in vitro and in vivo, a requirement for the induction of robust, durable antitumor CD8+ T-cell responses.32

Figure 2.

(A) In vitro α-GITR mAb upregulates CD40 expression on TDLN DC. TDLN DC (Fig. 1) were cultured in the presence of α-GITR mAb or ISO-matched rat IgG for 48 h and then stained with α-CD11c and α-CD40 or an ISO-matched Abs and analyzed by flow cytometry. Representative results from one of three independent experiments performed are presented. (B) In vivo α-GITR mAb enhances CD40 expression on TDLN DC. 4T1.2-Neu-bearing mice were left untreated or they were treated with tumor-primed CD4+ T cells (CD4+), α-GITR mAb (α-GITR), α-GITR/CD4+ or Rat IgG/CD4+. Two days later, single-cell suspensions of TDLN were stained by α-CD11c and α-CD40 or ISO-matched Abs and subsequently analyzed by flow cytometry. The expression (MFI) of CD40 on gated CD11c+ DC is presented from a representative experiment of three performed. (C) In vivo α-GITR/CD4-modulated TDLN DC produce IL-12p70. Tumor-bearing mice were treated as in (B). Forty-eight hours later, DC were purified from pooled TDLN and cultured for 3 d before the analysis of cytokine production. (D) In vitro CD4/α-GITR-modulated tumor antigen-loaded DC produce IL-12p70, IL-1α and TNF-α. In vitro-generated CD11c+ DC were loaded with 4T1.2-Neu lysates and co-cultured with 4T1.2-Neu-primed CD4+ T cells, along with α-GITR mAb or an ISO-matched Rat IgG for 48 h. Concentrations of IL-12p70, IL-1α and TNF-α in culture supernatants were then determined by ELISA. (C, D) Data representing three independent experiments were statistically analyzed.

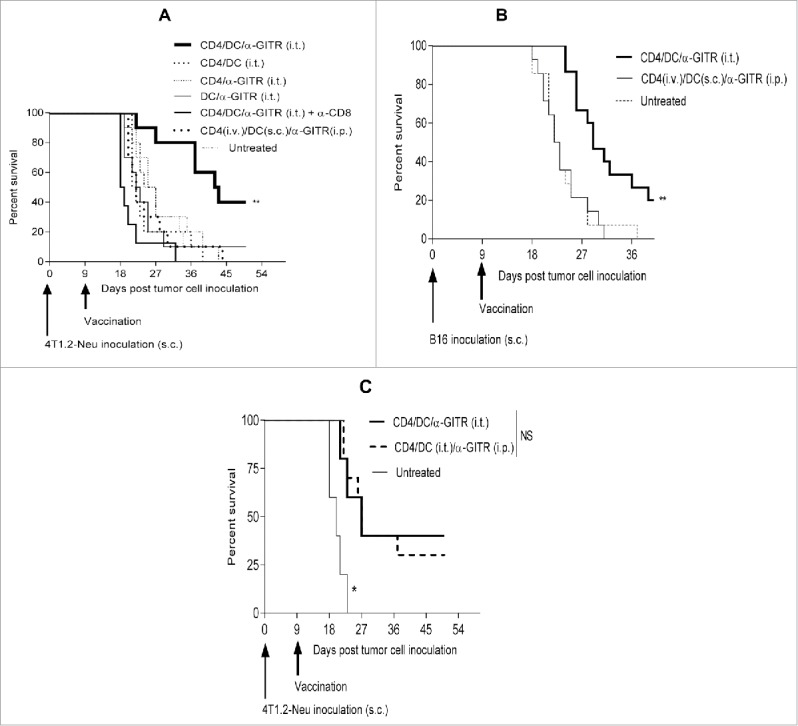

Intratumoral delivery of tumor-primed CD4+ T cells and tumor antigen-loaded DC combined with α-GITR mAb treatment (i.e., combination i.t. immunotherapy) promotes CD8+ T-cell-dependent immunotherapeutic efficacy against solid tumors

We have previously shown that ACT using tumor-primed CD4+ T cells (i.v.) in combination with i.p. administered α-GITR mAb can be a curative therapy against the murine breast carcinoma 4T1.2-Neu at an early-stage of disease,21 and we have also observed that this regimen inhibits the growth of B16 melanoma when applied at an early-stage of disease (Fig. S2), but not later in the disease process (i.e., tumors were established; Fig. 3A and B).

Figure 3.

Intratumoral delivery of tumor-primed CD4+ T cells, tumor antigen-loaded DC and α-GITR mAb elicits CD8+ T-cell-dependent therapeutic immunity. Exponentially growing tumor cells (4T1.2-Neu: A, C; B16: B) were inoculated s.c. into BALB/c or B6 mice (4–5/group) on day 0. On day 9 post-tumor inoculation, mice bearing tumor (∼50 mm2) were left untreated or they were treated once with tumor-primed CD4+ T cells (i.v.), tumor lysate-loaded DC (s.c.) and/or α-GITR mAb (i.p.), or by the mixture of these CD4+ T cells, DC and/or α-GITR mAb (i.t.). In some experiments in (A), α-CD8 mAb was injected i.p. on days 8, 10 and 12. In some experiments in (C), the mixtures of CD4+ T cells and DC were given i.t. and α-GITR mAb was injected i.p. Tumor size was monitored every 3–4 d, and animals were killed if tumors exceeded 400 mm2 or if they exhibited signs of distress. Animal survival (i.e., time-to-euthanasia) is presented in Kaplan–Meier plots. Data representing two (A, C) or three (B) independent experiments were statistically analyzed.

DC in the suppressive TME are likely inefficient in processing and presenting tumor antigens.25 Based on our finding that treatment with tumor-primed CD4+ T cells and α-GITR mAb synergistically promotes Type-1 DC (Figs. 1 and 2), we hypothesized that the further inclusion of ex vivo tumor antigen-pulsed DC in this regimen might improve antitumor CD8+ T cell cross-priming in vivo and therapeutic efficacy against more established tumors. Surprisingly, while systemic administration of tumor-primed CD4+ T cells (i.v.), tumor antigen-loaded DC (s.c.) and α-GITR mAb (i.p.) did not elicit therapeutic immunity against established 4T1.2-Neu or B16 tumors, coordinate delivery of these three agents directly into tumors was highly therapeutic (Fig. 3A and B). The efficacy of this intratumoral therapy was subsequently shown to be CD8+ T cell dependent, with all three components of the combination regimen being required for objective responses (Fig. 3A). Additional studies confirmed the requirement for i.t. delivery of cellular components (DC and CD4+ T cells), while α-GITR mAb could be administered either i.t. or systemically (i.p.), with comparable overall antitumor efficacy observed for the three-agent immunotherapy (Fig. 3C).

Combination i.t. therapeutic impact on the TME

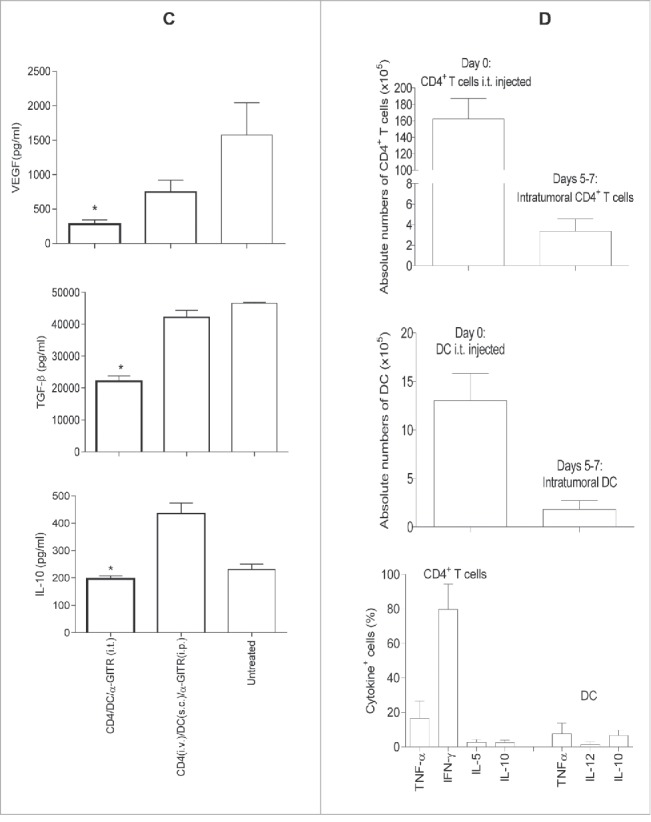

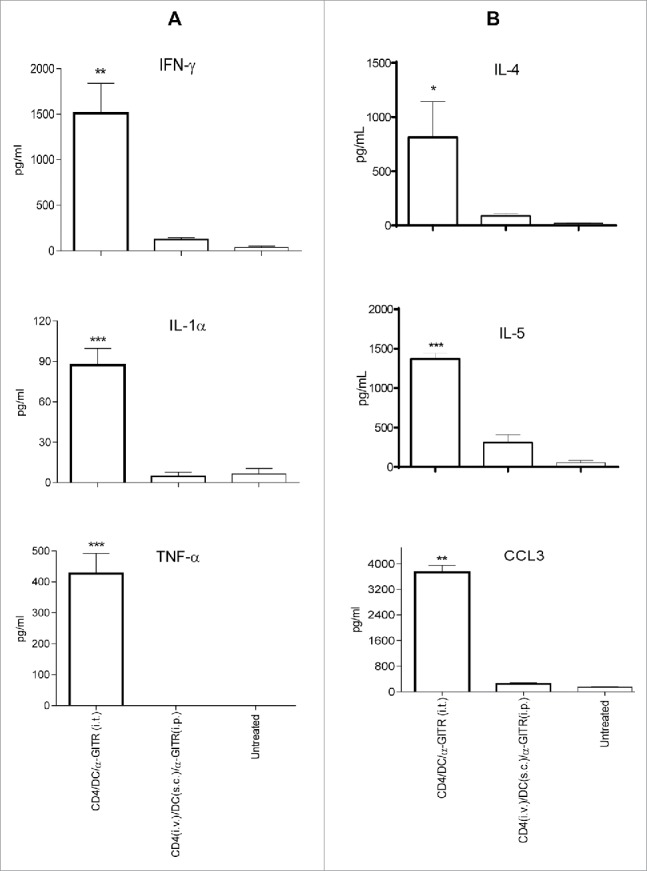

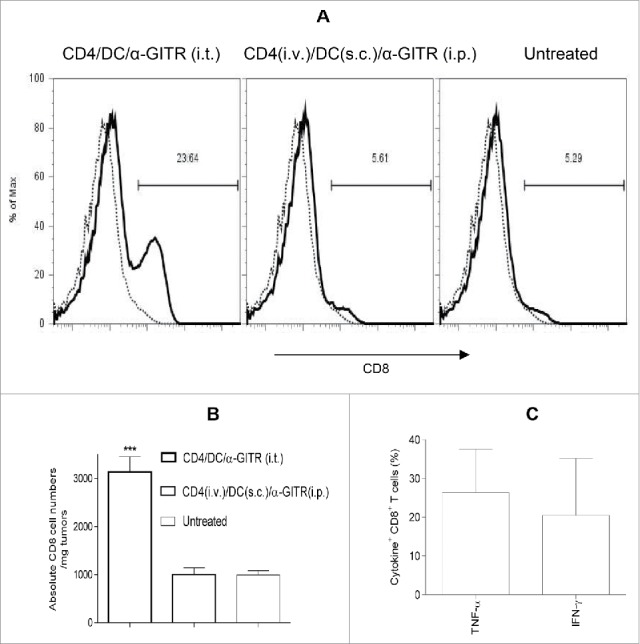

To determine the influence of immunotherapy on the TME, we examine locoregional production of cytokines/chemokines by ELISA or intracellular staining from cultured single cell suspensions of harvested tumors after enzymatic dissociation. We observed that only the three-agent treatment protocol including i.t.-delivered tumor-specific CD4+ T cells, tumor antigen-pulsed DC and α-GITR mAb led to production of the cytokines such as IFNγ, TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-4 and IL-5 and chemokine CCL3 from TME isolates (Fig. 4A and B). These soluble mediators have been previously reported to play important roles in modulating the TME by activating DC and vascular endothelial cells, and promoting the lymphocyte recruitment.33-37 The three-agent immunotherapy also preferentially reduced TME production of pro-angiogenic VEGF and limited production of the immunosuppressive cytokines TGF-β and IL-10 (Fig. 4C). After 5–7 d of the combination i.t. treatment, substantial CD4+ T cells and CD11c+ DC existed in the primary tumors (Fig. S3). The absolute numbers of these cells within tumors were around 2% injected CD4+ T cells and 10% injected CD11c+ DC (Fig. 4D). Intracellular cytokine staining shows that intratumoral CD4+ T cells produced significant antitumor cytokines IFNγ and TNF-α (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, freshly isolated CD4+ T cells produced IL-5 (Fig. S1), but intratumoral CD4+ T cells did not produce IL-5 (Fig. 4D), suggesting that intratumorally injected IL-5+Th2 might be converted to IFNγ+ and/or TNF-α+Th1. However, IL-5 was detected in the culture supernatants of whole primary tumor cells (Fig. 4B), indicating the existence of undefined IL-5-producing cell population(s) in the primary tumors. Also, the combination i.t. treatment decreased Foxp3+CD4+Treg in tumors (Fig. S4). Importantly, the three-agent protocol led to superior levels of IFNγ+ and/or TNF-α+CD8+ TIL (based on both frequency and absolute number and IFNγ/TNF-α production; Fig. 5A and C). When taken together, these results indicate that the combination i.t. immunotherapy conditions the TME to become more receptive to protective antitumor CD8+ TIL activation, recruitment and sustained functional activity (based on reduced suppression).

Figure 4B.

(Continued)

Figure 4.

Intratumoral delivery of tumor-primed CD4+ T cells, tumor antigen-loaded DC and α-GITR mAb induces an array of antitumor cytokines/chemokine in the TME. Tumor-bearing BALB/c mice (3/group) were left untreated or they were treated once by i.t. or systemic delivery of antitumor CD4+ T cells, tumor antigen-loaded DC and α-GITR mAb (per Fig. 3). Five days post-treatment (A–C), single-cell suspensions generated from dissociated tumors were prepared and cultured for an additional 72 h. Concentrations of IFNγ, TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, VEGF, TGF-β and CCL3 in the culture supernatants were determined by ELISA. Data (A–C) representing three independent experiments were statistically analyzed. Five to seven days post-treatment with i.t. delivery of antitumor CD4+ T cells, tumor antigen-loaded DC and α-GITR mAb, single cell suspensions of primary tumors were analyzed by flow cytometry (D). The absolute numbers of injected (day 0) or intratumoral (days 5–7 after the combination i.t. treatment) CD4+ T cells and CD11c+ DC and the intracellular cytokine+ CD4+ T cells or CD11c+ DC among CD45+ gated cells from two independent experiments (with total 11 mice) are shown (D).

Figure 5.

Intratumoral delivery of tumor-primed CD4+ T cells, tumor antigen-loaded DC and α-GITR mAb recruits CD8+ TIL. Single-cell suspensions of primary tumors (per Fig. 4) were stained using mAbs against CD45 and CD8+ or ISO-matched mAbs and analyzed by flow cytometry. CD8+ T cells among CD45+ gated cells are reported from a representative experiment of three performed (A). Thin dot line: ISO; Thick hair line: CD8+. The absolute numbers of CD8+ T cells in per mg of primary tumor tissue from three independent experiments are shown and were statistically analyzed in (B). The intratumoral IFN-α+ or IFNγ+CD8+ T cells among CD45+ gated cells (per Fig. 4D) from two independent experiments (with total 11 mice) are shown (C).

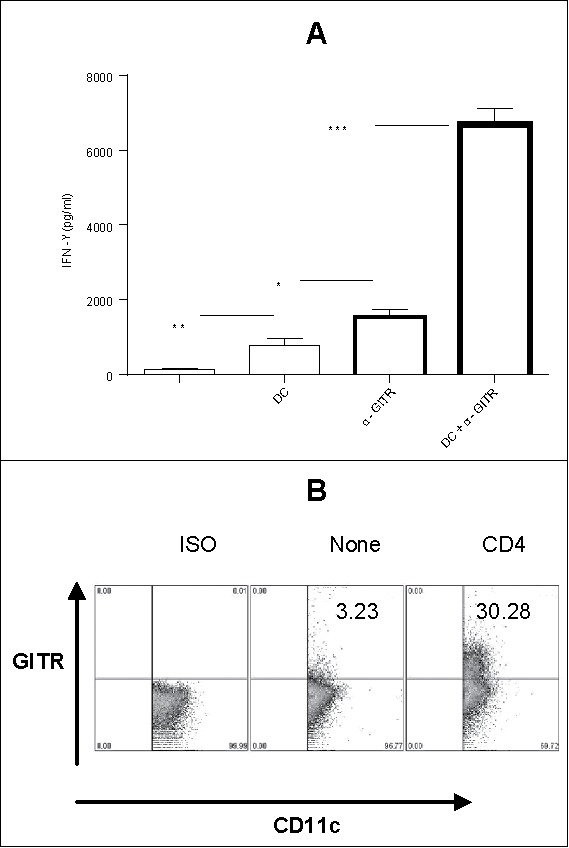

Combination i.t. immunotherapy elicits robust, durable antitumor CD8+ T-cell responses in vivo

To examine the three-agent i.t. therapy on systemic tumor-specific CD8+ T-cell responses, mice bearing established 4T1.2-Neu tumors were left untreated or they were treated as described in Fig. 5. Five days after treatment, CD8+ T cells were purified from the spleens and TDLN of mice and re-stimulated in vitro with mitomycin C-treated 4T1.2-Neu or syngenic CT26 colon carcinoma cell (irrelevant tumor control)-pulsed APC for 3 d, at which time culture supernatants were surveyed for contents by ELISA. Notably, the three-agent i.t. immunotherapy elicited superior Type 1 T-cell effector cell poly-functionality based on production of IFNγ, TNF-α and Granzyme B (Figs. 6A and B and S5A). The α-GITR mAb could be provided either i.t. or i.p., with a comparable degree of improved Type-1 CD8+ T-cell responses primed in situ (Figs. 6C and S5B), consistent with observed therapeutic benefits (Fig. 3C).

Figure 6.

Intratumoral delivery of tumor-primed CD4+ T cells, tumor antigen-loaded DC and α-GITR mAb induces robust, durable antitumor CD8+ T-cell responses. Tumor-bearing BALB/c mice were left untreated or they were treated once as indicated in Figs. 3C and 5. Five days later, CD8+ T cells were purified from spleen/TDLN of treated mice (with naive mice used as a negative control) and re-stimulated with mitomycin C-treated 4T1.2-Neu or CT26 tumor cells (as tumor-specificity controls) in the presence of irradiated naive splenic cells (serving as APC) for 72 h (A, C). In another set of experiments, single-cell suspensions of spleen/TDLN were re-stimulated with mitomycin C-treated 4T1.2-Neu or CT26 for 5 d. BD GolgiStop™ (monensin) was added into cultures for the final 4–6 h. Cells were stained with α-CD8 mAb and then be washed, fixed, permeabilized and further stained with α-Granzyme B mAb and analyzed by flow cytometry (B). ISO: dot line; Granzyme B: hair line. One hundred-eighty days after tumor-eradication, single-cell suspensions of spleen/LN were stained with antibodies against CD8+, CD44 and CD62L and analyzed by flow cytometry (D). At the same time, CD8+ T cells purified from spleen/TDLN of these same animals (using age-matched naive mice as controls) were re-stimulated as indicated in (A, E). The concentrations of IFNγ and TNF-α in the culture supernatants were determined by ELISA, and data represent three independent experiments and were statistically analyzed (A, C, E). One representative of three independent experiments is shown (B, D). Thirty days after tumor-eradication, these mice (with naive mice used as controls) were s.c. rechallenged with exponentially growing 4T1.2-Neu tumor cells (F). Data represents six tumor-eradication mice and four naive mice (F).

Since approximately 40% of tumor-bearing animals treated with the three-agent i.t. immunotherapy were rendered disease-free (Fig. 3A), we further investigated the durability of the therapeutic immune response. The frequency of CD8+ central memory T cells (CD8+ Tcm) and their capacity to produce IFNγ upon tumor-specific re-stimulation was examined 180 d after disease eradication. We observed substantial residual populations of CD8+ Tcm in regressor animals (vs. age-matched naive mice as controls; Fig. 6D) that were competent to produce IFNγ upon antigen-specific re-activation (Fig. 6E). Importantly, these tumor-eradication mice were fully protected in the rechallenge of cognate tumor (Fig. 6F).

Discussion

The progressive TME is characterized by a preponderance of immunosuppressive molecules (e.g., TGF-β, IL-10, CTLA-4, PD1, and PD-L1) and regulatory cell populations (e.g., myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) and regulatory T cells (Treg) among others) that serve to prevent or neutralize protective antitumor immunity.1,2,5 An increasing range of single-agent as well as combination agent strategies targeting angiogenesis, suppressive cytokines, immune checkpoint molecules and regulatory cells has been explored in translational models and clinical trials with the intent of reconditioning the TME into a milieu that is conducive for Type-1 DC and T-cell recruitment and antitumor activity in vivo.3-5,38-51

Tumor-associated immune subversion extends beyond the TME and also impacts TDLN, where antitumor CD8+ T-cell responses are ineffectively cross-primed by dysfunctional DC.52,53 In this regard, the (conditioned) TME is emerging as a preferred site in which to elicit systemic antitumor immunity.39,42,54,55 Based on our current results, delivery of an operational vaccine unit (i.e., tumor-specific CD4+ T cells and tumor antigen-pulsed DC) directly into the TME, along with local or systemic α-GITR mAb, proved competent to drive systemic activation of therapeutic CD8+ T cells capable of mediating tumor regression. Notably, the superior antitumor efficacy of this three-agent protocol required the presence of all three components to optimally activate DC, to turn on locoregional production of TIL-recruiting chemokines and for the arrival of polyfunctional CD8+ T-cell effectors into the TME. Remarkably, the delivery of the agents in non-TME tissue reservoirs also failed to yield objective antitumor effect, supporting the importance of the therapeutically conditioned TME as a potentially preferred site of vaccination.

The three-agent i.t. immunotherapy uniquely promoted local production of an array of cytokines (i.e., IFNγ, TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-4 and IL-5) and the chemokine CCL3. These pro-inflammatory cytokines (i.e., IFNγ, TNF-α and IL-1α) play important roles in the development of Type-1 polarized DC and T-cell responses, although they may also promote compensatory expression of regulatory molecules, such as PD-L1 among others.56 The Th2-associated cytokines IL-4 and IL-5 may also promote antitumor immune responses, although these tend to be weaker than those affiliated with pro-inflammatory cytokines.57,58 Interestingly, local production of an alternate Th2-associated IL-13 was not preferentially associated with treatment using the three-agent i.t. immunotherapy (Fig. S6). CCL3 has been previously reported to be critical in improving DC-based vaccine efficacy within sites of vaccination.37 We also determined that the three-agent i.t. therapy preferentially reduced production of pro-angiogenic VEGF as well as immunosuppressive IL-10 and TGF-β in the TME. The combination i.t. treatment decreased Treg in tumors (Fig. S4). As suggested that α-GITR reduces the suppression by Treg, whether this treatment dampens the suppressive activity of Treg needs to be further examined.

It remains unclear how the three-agent i.t. therapy initiates the reconditioning of the TME. One theoretical possibility is that the local vaccine nucleates the formation of tertiary lymph structures (TLS;59,60) within the TME, allowing for both CD8+ T-cell cross-priming and the reactivation of “exhausted” antitumor T cells to occur within the disease site in association with treatment benefit. In this context, DC and CD4+ have been reported to be required for the formation of TLS in non-lymphoid sites such as the thyroid and lung where T priming occurs under conditions of chronic inflammation.61-65 Alternatively, the intratumorally injected ex vivo tumor antigen-loaded DC might migrate to TDLN for cross-priming of CD8+ T cells.

We believe that this three-agent protocol may be effectively translated into the clinic using patient-derived (autologous) DC/CD4+ T cells and in-clinic α-GITR mAb (i.e., as applied in phase I clinical trials NCT02583165, NCT02628574) for treating accessible solid tumors such as breast tumor and melanoma and probably other types of solid tumors such as prostate and brain tumors during surgery. Further combination with immune checkpoint blockade might be expected to further expand the magnitude, durability and antitumor effectiveness of therapy-induced CD8+ T effector cells, a hypothesis that we will investigate in prospective studies.

Materials and methods

Mice, cell lines and reagents

BALB/c and C57BL/6 (B6) mice [female (f), 6–8 weeks (wks)] were purchased from JAX (Bar Harbor, ME) or Taconic (Rensselaer, NY). Mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions in the University of Pittsburgh DLAR, and handled under aseptic conditions as per the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC)-approved protocol and in accordance with recommendations for the proper care and use of laboratory animals.

Mouse breast cancer cell line 4T1.2-Neu was cultured in DMEM (IRVINE Scientific, Santa Ana, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone, Logan, UT), 2 mmol/L glutamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 1X antibiotic/antimycotic solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and G-418 (500 µg/mL) (Invitrogen).21,27 Mouse melanoma (B16) and colon carcinoma (CT26) cell lines (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were cultured in the same media excluding G-418.

Agonist α-GITR mAb (DTA-1) used in experiments was purchased from eBioscience (functional grade) or Protein A purified from culture supernatants harvested from the hybridoma cell line following the protocol provided by Dr. S. Sakaguchi with endotoxin-free reagents such as water and PBS purchased from Sigma, and LPS in purified α-GITR mAb measured by Limulus amebocyte lysate was < 0.1 ng/μg protein.21

Tumor-primed CD4+ T cells and tumor antigen-loaded DC

Tumor-primed CD4+ T cells: BALB/c or B6 mice were inoculated subcutaneous (s.c.) with 105 4T1.2-Neu breast carcinoma cells in the 4th mammary fat pad or with 105 B16 melanoma cells s.c. in the left flank on day 0 as described previously.21 After 9–21 d (as indicated), tumor-primed CD4+CD25− T cells were obtained by negative selection from spleen and lymph nodes (LN) using a mouse CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec). Only freshly purified tumor-primed CD4+CD25− T cells were used in experiments.

Tumor antigen-loaded DC: Bone marrow-derived DC were generated from naive BALB/c or B6 mice in cultures containing rmGM-CSF and rmIL-4.28 On day 5 of culture, DC were purified using anti-mouse CD11cmicro-beads (Miltenyi Biotec) and subsequently loaded with 4T1.2-Neu or B16 tumor lysates for 24 h at 37°C as described previously.21,28 Prior to injection, tumor antigen-loaded DC were washed using PBS. In some experiments (where indicated), DC were also purified from the spleen/LN of naive BALB/c mice using anti-mouse CD11cmicro-beads before loading with 4T1.2-Neu or B16 tumor lysates, washing with PBS and use in studies.

CD4+ T cell, DC and/or α-GITR mAb co-cultures

Tumor-primed CD4+ T cells (106) were cultured in the absence or presence of α-GITR mAb (50 μg/mL) and/or tumor antigen-loaded (spleen/LN) DC (4 × 105) in 200 μL culture media (CM) [RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mmol/L glutamine and 1X antibiotic/antimycotic solution] at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 48 h. The concentration of IFNγ in culture supernatants was then determined by ELISA (eBioscience). In another set of experiments, tumor antigen loaded (bone marrow derived) DC (4 × 105) were cultured with CD4+ T cells (106) in the presence of α-GITR mAb or isotype (ISO)-matched rat IgG (50 μg/mL) in 500 μL CM at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 48 h. The concentrations of IL-12p70, TNF-α and IL-1α in the culture supernatants were then determined by ELISA (BD Bioscience and, eBioscience). In some experiments, tumor antigen-loaded (spleen/LN) DC (4 × 105) were cultured alone, with tumor-primed CD4+ T cells (4 × 105) or in the presence of 50 μg/mL α-GITR mAb (or ISO-matched rat IgG) in 200 μL CM at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 48 h. Cells were then harvested, washed and stained with α-CD11c-APC (HL3) and α-CD40-PE (1C10) or α-GITR-PE (DTA-1) (Fc receptor binding of Abs was minimized by pre-incubation with rat anti-mouse CD16/CD32 mAb and ISO control Abs) (BD Biosciences, eBioscience and R&D Systems), before analysis by flow cytometry. Propidium iodide (BD Biosciences) was used to check cell viability. Forward scatter and side scatter was used to exclude cell debris. After three final washes using FACS staining buffer, the cells were resuspended in 500 μL 1% PFA. Sample data were acquired on a BD LSRII with CellQuest software (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star).

TDLN-derived DC

4T1.2-Neu cells (105) were s.c. inoculated into BALB/c mice (5 mice/group) on day 0. Tumor-bearing mice were left untreated or treated once with tumor-primed by CD4+ T cells, α-GITR mAb, α-GITR + CD4+ T cells or ISO-matched rat IgG + CD4+ T cells on day 3 as described previously.21 Forty-eight hours later, single-cell suspensions of TDLN were stained with α-CD11c and -CD40 Abs and analyzed by flow cytometry as described above. DC were also purified from pooled TDLN using anti-mouse CD11cmicro-beads. Purified TDLN DC (5 × 104) were subsequently cultured in 200 μL CM at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 72 h, with the resulting cell supernatants analyzed for levels of IL-12p70 using a specific ELISA.

Cytokines, chemokine and CD8+ T cells in tumors

BALB/c mice were inoculated s.c. with 4T1.2-Neu (105) day 0. On day 9, tumor-bearing mice were left untreated or treated once with tumor-primed CD4+ T cells (107, i.v.), DC (5 × 106, s.c.) and α-GITR mAb (800 μg, i.p.), or by the mixtures (30 μL) of CD4+ T cells (107), DC (5 × 106) and α-GITR (50 μg), which were injected within and around the tumor. Five days later, primary tumors from each group were removed, weighed, then minced and suspended in HBSS buffer supplemented with 2% FBS, 2.7% collagenase, 0.25% Hyaluronidase and 20 Unit/mL DNase (Sigma) for 2 h at 37°C. Cell suspensions were collected by pipetting up and down to further dissociate cells and passed through a 70 μm Nylon mesh filter to yield single cell suspensions that were then stained using 7AAD, α-CD45-APC and α-CD8-FITC or ISO-matched mAbs and subsequently analyzed by flow cytometry. Control experiments were used to confirm gated viable cells (using 7AAD) were > 95% CD45+ cells. At the same time, single-cell suspensions of primary tumors (5 mg) were cultured in 1 mL CM for 72 . The concentrations of IFNγ, TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-13, VEGF, TGF-β and CCL3 in the culture supernatants were then determined by ELISA (BD Biosciences and eBioscience).

Intracellular cytokine staining

Freshly isolated tumor-primed CD4+ T cells (106) were cultured in CM in the presence of Brefeldin A (BFA) (10 µg/mL) (Sigma) at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 4 h. These cells were washed and stained with α-CD4-V500 for 30 min, and then washed, fixed and permeabilized with perm/fix buffer (eBioscience), and intracellularly stained with α-IL-2-V450, -IFNγ-PE and -TNF-α-Alexa Flour®647 or α-IL-4-APC, -IL-5-PE and -IL-10-V450 for 15 min. In another set of experiments, after 5–7 d of the combination i.t. therapeutic treatment, single cell suspensions of primary tumors were obtained as described above and cultured in CM at 37°C, 5% CO2 for overnight. During the last 4 h of culture, BFA (10 µg/mL) was added into the culture. Surface and intracellular staining were performed as described above with two sets of antibodies (α-CD45-PerCP/Cy5.5, -CD4-V500, -CD8-Alexa Flour®700, -IFNγ-V450, -TNF-α-Alexa Flour®647, -IL-5-PE and -IL-10-FITC or α-CD45-PerCP/Cy5.5, -CD11c-PE-Cy7, -IL-12-V450, -TNF-α-Alexa Flour®647, -IL-10-PE). All antibodies excluding CD8-Alexa Flour®700 (BioLegend) were purchased from BD Biosciences. After three final washes using FACS staining buffer, the cells were resuspended in 500 μL 1% PFA and analyzed by flow cytometry as described above.

Analysis of tumor-specific CD8+ T-cell responses

4T1.2-Neu-bearing BALB/c mice were left untreated or they were treated as described above. Five days after treatment, splenic CD8+ T cells were purified from treated vs. naive mice using α-CD8 micro-beads (Miltenyi Biotec). Purified CD8+ T cells (4 × 105) were then re-stimulated in vitro with mitomycin C-treated 4T1.2-Neu or CT26 colon tumor cells (4 × 104) in the presence of irradiated naive splenic cells (serving as antigen-presenting cells [APC]) (2 × 106) for 72 hours as described previously.21 The concentrations of IFNγ and TNF-α in the culture supernatants were then determined by ELISA (BD Biosciences and eBioscience: TNF-α: detection limit = 8 pg/mL). Coordinately, single cell suspensions of spleen/TDLN (106/mL) were re-stimulated with mitomycin C-treated 4T1.2-Neu or CT26 tumor cells (105/mL) in CM at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 5 d. Responder cells were then treated with 10 μg/mL of BD GolgiStop™ (monensin) (BD Biosciences) over the final 4–6 h of the culture period. After washing, harvested cells were Fc-blocked using α-CD16/32 and stained with PE-α-mouse CD8+ (53-6.7). Cells were then washed, fixed, permeabilized and intracellularly stained with α-Granzyme B-Alexa Fluor® 647 (16G6) for 15 min. After three final washes using FACS staining buffer, the cells were resuspended in 500 μL 1% PFA and analyzed by flow cytometry. In mice rendered tumor-free by therapy, single-cell suspensions of spleen/LN were isolated 180 d after tumor-eradication (with age-matched naive mice used as controls) and stained with α-CD8-APC, α-CD44-PE and α-CD62L-FITC mAbs, then analyzed by flow cytometry. Coordinately, CD8+ T cells were purified from the spleen/LN of these animals and re-stimulated with mitomycin C-treated 4T1.2-Neu or CT26 tumor cells in the presence of irradiated naive splenic cells (serving as APC) for 72 h as described above. Harvested culture supernatants were then analyzed for levels of IFNγ and TNF-α using cytokine-specific ELISAs.

Combination therapies

Exponentially growing 4T1.2-Neu or B16 tumor cells (105) were inoculated into the 4th mammary fat pad of BALB/c mice or s.c. into the left flank of B6 mice on day 0, respectively. On day 9 post-tumor inoculation, mice were randomized (mean tumor size of ∼50 mm2) and treated with tumor-primed CD4+ T cells (107, i.v.), tumor antigen-loaded DC (5 × 106, s.c.)29 +/− α-GITR mAb (800 μg, i.p.), or with perilesional injections of mixtures (30 μL) of CD4+ T cells (107), DC (5 × 106) and α-GITR (50 μg). In some experiments (where indicated), depleting α-CD8 mAb (53-6.7, 200 μg/injection) was injected i.p. on days 8, 10 and 12 post-tumor inoculation. Thirty days after tumor-eradication, these mice (with naive mice used as controls) were s.c. rechallenged with exponentially growing 4T1.2-Neu tumor cells (105). Primary tumors were measured using an electronic caliper every other day to determine orthogonal diameters to calculate tumor areas. Mice were killed if tumors exceed a size of 10 mm in diameter, when tumor became ulcerated or bled, or when mice displayed signs of disease-associated distress.

Statistical analyses

Differences between groups were analyzed using a Student's t-test (immune assays and tumor size; Graph Pad Prism version 6). Data from animal survival experiments were statistically analyzed using Log rank test (Graph Pad Prism version 6) and presented in Kaplan–Meier survival curves. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; NS: not significant.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to Dewayne Falkner in the Department of Immunology Flow Cytometry Core for his assistance in study performance.

Funding

This work was supported by the Department of Dermatology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and by NIH grants R21CA191522 (ZY) and P50CA121973 (LDF).

Author contributions

ZL, XH, YZ, JZ and CDC performed/coordinated the experiments, LZ, XH, YZ, LDF, WJS and ZY analyzed the data, WJS edited the manuscript and ZY supervised the study and wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Gajewski TF. Failure at the effector phase: immune barriers at the level of the melanoma tumor microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13:5256-61; PMID:17875753; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joyce JA, Fearon DT.. T cell exclusion, immune privilege, and the tumor microenvironment. Science 2015; 348:74-80; PMID:25838376; https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.aaa6204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellone M, Mondino A, Corti A.. Vascular targeting, chemotherapy and active immunotherapy: teaming up to attack cancer. Trends in Immunol 2008; 29:235-41; PMID:18375183; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.it.2008.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Disis ML. Enhancing cancer vaccine efficacy via modulation of the tumor microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15:6476-8; PMID:19861446; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pitt JM, Marabelle A, Eggermont A, Soria JC, Kroemer G, Zitvogel L. Targeting the tumor microenvironment: removing obstruction to anticancer immune responses and immunotherapy. Ann Oncol 2016; 27:1482-92; PMID:27069014; https://doi.org/ 10.1093/annonc/mdw168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hung K, Hayashi R, Lafond-Walker A, Lowenstein C, Pardoll D, Levitsky H. The central role of CD4(+) T cells in the antitumor immune response. J Exp Med 1998; 188:2357-68; PMID:9858522; https://doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.188.12.2357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ostrand-Rosenberg S. CD4+ T lymphocytes: a critical component of antitumor immunity. Cancer Investig 2005; 23:413-9; PMID:16193641; https://doi.org/ 10.1081/CNV-67428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laidlaw BJ, Craft JE, Kaech SM. The multifaceted role of CD4+ T cells in CD8+ T cell memory. Nat Rev Immunol 2016; 16:102-11; PMID:26781939; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nri.2015.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunder NN, Wallen H, Cao J, Hendricks DW, Reilly JZ, Rodmyre R, Jungbluth A, Gnjatic S, Thompson JA, Yee C. Treatment of metastatic melanoma with autologous CD4+ T cells against NY-ESO-1. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:2698-703; PMID:18565862; https://doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa0800251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zanetti M. Tapping CD4 T cells for cancer immunotherapy: the choice of personalized genomics. J Immunol 2014; 194:2049-56; PMID:25710958; https://doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.1402669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tran E, Turcotte S, Gros A, Robbins PF, Lu YC, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Somerville RP, Hogan K, Hinrichs CS et al. Cancer immunotherapy based on mutation-specific CD4+ T cells in a patient with epithelial cancer. Science 2014; 344:641-5; PMID:24812403; https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1251102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nocentini G, Ronchetti S, Cuzzocrea S, Riccardi C. GITR/GITRL: more than an effector T cell co-stimulatory system. Eur J Immunol 2007; 37:1165-9; PMID:17407102; https://doi.org/ 10.1002/eji.200636933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimizu J, Yamazaki S, Takahashi T, Ishida Y, Sakaguchi S. Stimulation of CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells through GITR breaks immunological self-tolerance. Nat Immunol 2002; 3:135-42; PMID:11812990; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/ni759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McHugh RS, Whitters MJ, Piccirillo CA, Young DA, Shevach EM, Collins M, Byrne MC. CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells: gene expression analysis reveals a functional role for the glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor. Immunity 2002; 16:311-23; PMID:11869690; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00280-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turk MJ, Guevara-Patiño JA, Rizzuto GA, Engelhorn ME, Sakaguchi S, Houghton AN. Concomitant tumor immunity to a poorly immunogenic melanoma is prevented by regulatory T cells. J Exp Med 2004; 200:771-82; PMID:15381730; https://doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.20041130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ko K, Yamazaki S, Nakamura K, Nishioka T, Hirota K, Yamaguchi T, Shimizu J, Nomura T, Chiba T, Sakaguchi S. Treatment of advanced tumors with agonistic anti-GITR mAb and its effects on tumor-infiltrating Foxp3+CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells. J Exp Med 2005; 202:885-91; PMID:16186187; https://doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.20050940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen AD, Diab A, Perales MA, Wolchok JD, Rizzuto G, Merghoub T, Huggins D, Liu C, Turk MJ, Restifo NP et al. Agonist anti-GITR antibody enhances vaccine-induced CD8+ T-cell responses and tumor immunity. Cancer Res 2006; 66:4904-12; PMID:16651447; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramirez-Montagut T, Chow A, Hirschhorn-Cymerman D, Terwey TH, Kochman AA, Lu S, Miles RC, Sakaguchi S, Houghton AN, van den Brink MR. Glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor family related gene activation overcomes tolerance/ignorance to melanoma differentiation antigens and enhances antitumor immunity. J Immunol 2006; 176:6434-42; PMID:16709800; https://doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.6434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou P, L'italien L, Hodges D, Schebye XM. Pivotal roles of CD4+ effector T cells in mediating agonistic anti-GITR mAb-induced-immune activation and tumor immunity in CT26 tumors. J Immunol 2007; 179:7365-75; PMID:18025180; https://doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishikawa H, Kato T, Hirayama M, Orito Y, Sato E, Harada N, Gnjatic S, Old LJ, Shiku H. Regulatory T cell-resistant CD8+ T cells induced by glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor signaling. Cancer Res 2008; 68:5948-54; PMID:18632650; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Z, Tian S, Falo LD Jr, Sakaguchi S, You Z. Therapeutic immunity by adoptive tumor-primed CD4+ T Cell transfer in combination with in vivo GITR ligation. Mol Ther 2009; 17:1274-81; PMID:28178474; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/mt.2009.100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen AD, Schaer DA, Liu C, Li Y, Hirschhorn-Cymmerman D, Kim SC, Diab A, Rizzuto G, Duan F, Perales MA et al. Agonist Anti-GITR monoclonal antibody induces melanoma tumor immunity in mice by altering regulatory T cell stability and intra-tumor accumulation. PLoS One 2010; 5:e10436; PMID:20454651; https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0010436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schaer DA, Budhu S, Liu C, Bryson C, Malandro N, Cohen A, Zhong H, Yang X, Houghton AN, Merghoub T et al. GITR pathway activation abrogates tumor immune suppression through loss of regulatory T-cell lineage stability. Cancer Immunol Res 2013; 1:1-12; PMID:24416730; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahne AE, Mauze S, Joyce-Shaikh B, Xia J, Bowman EP, Beebe AM, Cua DJ, Jain R. Dual roles for regulatory T cell depletion and co-stimulatory signaling in agonistic GITR targeting for tumor immunotherapy. Cancer Res 2017; 77:1108-18; PMID:28122327; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palucka K, Banchereau J. Dendritic-cell-based therapeutic cancer vaccines. Immunity 2013; 39:38-48; PMID:23890062; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lelekakis M, Moseley JM, Martin TJ, Hards D, Williams E, Ho P, Lowen D, Javni J, Miller FR, Slavin J et al. A novel orthotopic model of breast cancer metastasis to bone. Clin Exp Metastasis 1999; 17:163-70; PMID:10411109; https://doi.org/ 10.1023/A:1006689719505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim JH, Majumder N, Lin H, Chen J, Falo LD Jr, You Z. Enhanced immunity by NeuEDhsp70 DNA vaccine is needed to combat an aggressive spontaneous metastatic breast cancer. Mol Ther 2005; 11:941-9; PMID:15922965; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Tian S, Liu Z, Zhang J, Zhang M, Bosenberg MW, Kedl RM, Waldmann TA, Storkus WJ, Falo LD Jr et al. Dendritic cell-derived interleukin-15 is crucial for therapeutic cancer vaccine potency. OncoImmunology 2014; 3:e959321; PMID:25941586; https://doi.org/ 10.4161/21624011.2014.959321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mullins DW, Sheasley SL, Ream RM, Bullock TN, Fu YX, Engelhard VH. Route of immunization with peptide-pulsed dendritic cells controls the distribution of memory and effector T cells in lymphoid tissues and determines the pattern of regional tumor control. J Exp Med 2003; 198:1023-34; PMID:14530375; https://doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.20021348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Z, Noh HS, Chen J, Kim JH, Falo LD Jr, You Z. Potent Tumor-specific protection ignited by adoptively transferred CD4+ T cells. J Immunol 2008; 181:4363-70; PMID:18768895; https://doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.4363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langenkamp A, Messi M, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Kinetics of dendritic cell activation: impact on priming of TH1, TH2 and nonpolarized T cells. Nat Immunol 2000; 1:311-6; PMID:11017102; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/79758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12 and the regulation of innate resistance and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2003; 3:133-46; PMID:12563297; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nri1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blankenstein T. The role of tumor stroma in the interaction between tumor and immune system. Curr Opin Immunol 2005; 17:180-6; PMID:15766679; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.coi.2005.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bellone M, Mondino A, Corti A. Vascular targeting, chemotherapy and active immunotherapy: teaming up to attack cancer. Trends in Immunol 2008; 29:235-41; PMID:18375183; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.it.2008.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koide SL, Inaba K, Steinman RM. Interleukin 1 enhances T-dependent immune responses by amplifying the function of dendritic cells. J Exp Med 1987; 165:515-30; PMID:2950198; https://doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.165.2.515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castellino F, Huang AY, Altan-Bonnet G, Stoll S, Scheinecker C, Germain RN. Chemokines enhance immunity by guiding naïve CD8 T cells to sites of CD4 T cell-dendritic cell interaction. Nature 2006; 440:890-5; PMID:16612374; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nature04651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitchell DA, Batich KA, Gunn MD, Huang MN, Sanchez-Perez L, Nair SK, Congdon KL, Reap EA, Archer GE, Desjardins A et al. Tetanus toxoid and CCL3 improve dendritic cell vaccines in mice and glioblastoma patients. Nature 2015; 519:366-9; PMID:25762141; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nature14320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang B, Bowerman NA, Salama JK, Schmidt H, Spiotto MT, Schietinger A, Yu P, Fu YX, Weichselbaum RR, Rowley DA et al. Induced sensitization of tumor stroma leads to eradication of established cancer by T cells. J Exp Med 2007; 204:49-55; PMID:17210731; https://doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.20062056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jackaman C, Lew AM, Zhan Y, Allan JE, Koloska B, Graham PT, Robinson BW, Nelson DJ. Deliberately provoking local inflammation drives tumors to become their own protective vaccine site. Int Immunol 2008; 20:1467-79; PMID:18824504; https://doi.org/ 10.1093/intimm/dxn104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Epardaud M, Elpek KG, Rubinstein MP, Yonekura AR, Bellemare-Pelletier A, Bronson R, Hamerman JA, Goldrath AW, Turley SJ. Interleukin-15/interleukin-15R complexes promote destruction of established tumors by reviving tumor-resident CD8+ T cells. Cancer Res 2008; 68:2972-83; PMID:18413767; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quezada SA, Peggs KS, Simpson TR, Shen Y, Littman DR, Allison JP. Limited tumor infiltration by activated T effector cells restricts the therapeutic activity of regulatory T cell depletion against established melanoma. J Exp Med 2008; 205:2125-38; PMID:18725522; https://doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.20080099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Currie AJ, van der Most RG, Broomfield SA, Prosser AC, Tovey MG, Robinson BW. Targeting the effector site with IFN-alphabeta-inducing TLR ligands reactivates tumor resident CD8 T cell responses to eradicate established solid tumors. J Immunol 2008; 180:1535-44; PMID:18209049; https://doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ueda R, Fujita M, Zhu X, Sasaki K, Kastenhuber ER, Kohanbash G, McDonald HA, Harper J, Lonning S, Okada H. Systemic inhibition of transforming growth factor-β in glioma-bearing mice improves the therapeutic efficacy of glioma-associated antigen peptide vaccines. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15:6551-9; PMID:19861464; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hirschhorn-Cymerman D, Rizzuto GA, Merghoub T, Cohen AD, Avogadri F, Lesokhin AM, Weinberg AD, Wolchok JD, Houghton AN. OX40 engagement and chemotherapy combination provides potent antitumor immunity with concomitant regulatory T cell apoptosis. J Exp Med 2009; 206:1103-16; PMID:19414558; https://doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.20082205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lapteva N, Aldrich M, Weksberg D, Rollins L, Goltsova T, Chen SY, Huang XF. Targeting the intratumoral Dendritic cells by the oncolytic adenoviral vaccine expressing RANTES elicits potent antitumor immunity. J Immunother 2009; 32:145-56; PMID:19238013; https://doi.org/ 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318193d31e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ali OA, Emerich D, Dranoff G, Mooney DJ. In situ regulation of DC subsets and T cells mediates tumor regression in mice. Sci Transl Med 2009; 1:8ra19; PMID:20368186; https://doi.org/ 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qu Y, Chen L, Pardee AD, Taylor JL, Wesa AK, Storkus WJ. Intralesional delivery of dendritic cells engineered to express T-bet promotes protective Type 1 immunity and the normalization of the tumor microenvironment. J Immunol 2010; 185:2895-902; PMID:20675595; https://doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.1001294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang X, Zhang X, Fu ML, Weichselbaum RR, Gajewski TF, Guo Y, Fu YX. Targeting the tumor microenvironment with interferon-beta bridges innate and adaptive immune responses. Cancer Cell 2014; 25:37-48; PMID:24434209; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee Y, Auh SL, Wang Y, Burnette B, Wang Y, Meng Y, Beckett M, Sharma R, Chin R, Tu T et al. Therapeutic effects of ablative radiation on local tumor require CD8+ T cells: changing strategies for cancer treatment. Blood 2009; 114:589-95; PMID:19349616; https://doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2009-02-206870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ebos JM, Kerbel RS. Antiangiogenic therapy: Impact on invasion, disease progression, and metastasis. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2011; 8:210-21; PMID:21364524; https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garg AD, Vandenberk L, Koks C, Verschuere T, Boon L, Van Gool SW, Agostinis P. Dendritic cell vaccines based on immunogenic cell death elicit danger signals and T cell-driven rejection of high-grade glioma. Sci Transl Med 2016; 8:328ra27; PMID:26936504; https://doi.org/ 10.1126/scitranslmed.aae0105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chaput N, Darrasse-Jèze G, Bergot AS, Cordier C, Ngo-Abdalla S, Klatzmann D, Azogui O. Regulatory T cells prevent CD8+ T cell maturation by inhibiting CD4+ Th cell at tumor sites. J Immunol 2007; 179:4969-78; PMID:17911581; https://doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.4969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu Z, Kim JH, Falo LD Jr, You Z. Tumor treg potently abrogate antitumor immunity. J Immunol 2009; 182:6160-7; PMID:19414769; https://doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.0802664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Piconese S, Valzasina B, Colombo MP. OX40 triggering blocks suppression by regulatory T cells and facilitates tumor rejection. J Exp Med 2008; 205:825-39; PMID:18362171; https://doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.20071341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kilinc MO, Gu T, Harden JL, Virtuoso LP, Egilmez NK. Central role of tumor-associated CD8+ T effector/memory cells in restoring systemic antitumor immunity. J Immunol 2009; 182:4217-25; PMID:19299720; https://doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.0802793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Spranger S, Spaapen RM, Zha Y, Williams J, Meng Y, Ha TT, Gajewski TF. Up-regulation of PD-L1, IDO, and Tregs in the melanoma tumor microenvironment is driven by CD8+ T Cells. Sci Transl Med 2013; 5:200ra116; PMID:23986400; https://doi.org/ 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tepper RI, Coffman RL, Leder P. An eosinophil-dependent mechanism for the antitumor effect of interleukin-4. Science 1992; 257:548-51; PMID:1636093; https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1636093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dobrzanski MJ, Reome JB, Dutton RW. Role of effector cell-derived IL-4, IL-5, and perforin in early and late stages of type 2 CD8 effector cell-mediated tumor rejection. J Immunol 2001; 167:424-34; PMID:11418679; https://doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.167.1.424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dieu-Nosjean MC. Tertiary lymphoid structures in cancer and beyond. Trends Immunol 2014; 35:571-80; PMID:25443495; https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.it.2014.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hiraoka N, Ino Y, Yamazaki-Itoh R. Tertiary lymphoid organs in cancer tissues. Front immunol 2016; 7:244; PMID:27446075; https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marinkovic T, Garin A, Yokota Y, Fu YX, Ruddle NH, Furtado GC, Lira SA. Interaction of mature CD3+CD4+ T cells with dendritic cells triggers the development of tertiary lymphoid structures in the thyroid. J Clin Invest 2006; 116:2622-32; PMID:16998590; https://doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI28993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.GeurtsvanKessel CH, Willart MA, Bergen IM, van Rijt LS, Muskens F, Elewaut D, Osterhaus AD, Hendriks R, Rimmelzwaan GF, Lambrecht BN. Dendritic cells are crucial for maintenance of tertiary lymphoid structures in the lung of influenza virus-infected mice. J Exp Med 2009; 206:2339-49; PMID:19808255; https://doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.20090410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Halle S, Dujardin HC, Bakocevic N, Fleige H, Danzer H, Willenzon S, Suezer Y, Hämmerling G, Garbi N, Sutter G et al. Induced bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue serves as a general priming site for T cells and is maintained by dendritic cells. J Exp Med 2009; 206:2593-601; PMID:19917776; https://doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.20091472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goc J, Germain C, Vo-Bourgais TK, Lupo A, Klein C, Knockaert S, de Chaisemartin L, Ouakrim H, Becht E, Alifano M et al. Dendritic cells in tumor-associated tertiary lymphoid structures signal a Th1 cytotoxic immune contexture and license the positive prognostic value of infiltrating CD8+ T cells. Cancer Res 2014; 74:705-15; PMID:24366885; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shimizu K, Yamasaki S, Shinga J, Sato Y, Watanabe T, Ohara O, Kuzushima K, Yagita H, Komuro Y, Asakura M et al. Systemic DC activation modulates the tumor microenvironment and shapes the long-lived tumor-specific memory mediated by CD8+ T cells. Cancer Res 2016; 76:3756-66; PMID:27371739; https://doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-3219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.