Abstract

Background

Women who experience significant premenstrual symptoms differ in the extent to which these symptoms cause cyclical impairment. This study clarifies the type and number of symptoms that best predict premenstrual impairment in a sample of women undergoing prospective assessment for premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) in a research setting. Central research goals were to determine (1) which emotional, psychological, and physical symptoms of PMDD are uniquely associated with premenstrual impairment, and (2) how many cyclical symptoms optimally predict the presence of a clinically significant premenstrual elevations of impairment.

Methods

267 naturally cycling women recruited for retrospective report of premenstrual emotional symptoms completed daily symptom reports using the Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP) and occupational, recreational, and relational impairment for 1–4 menstrual cycles (N = 563 cycles).

Results

Multilevel regression revealed that emotional, psychological, and physical symptoms differ in their associations with impairment. The core emotional symptoms of PMDD were predictors of impairment, but not after accounting for psychological symptoms, which were the most robust predictors. The optimal number of premenstrual symptoms for predicting clinically significant premenstrual impairment was four.

Conclusion

Results enhance our understanding of the type and number of premenstrual symptoms associated with premenstrual impairment among women being evaluated for PMDD in research contexts. Additional work is needed to determine whether cognitive symptoms should receive greater attention in the study of PMDD, and to revisit the usefulness of the five-symptom diagnostic threshold.

Introduction

Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD) is characterized by clinically significant emotional symptoms emerging in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and resolving with the onset of menses (APA 2013). Roughly 5.5% of reproductive age women meet criteria for DSM-5 PMDD, which requires that at least five total symptoms per cycle follow this perimenstrual on-off pattern (Gehlert et al. 2009). Given the poor prospective validity of retrospectively-reported premenstrual symptoms (Rubinow et al. 1984), this cyclical symptom pattern must be confirmed by prospective daily symptom ratings. The recent inclusion of PMDD into DSM-5 was based on prospective epidemiological evidence for the existence of PMDD, experimental evidence for the pathophysiological role of ovarian steroid changes in PMDD, and evidence that PMDD is associated with significant societal burden and impairment (Epperson et al. 2012).

In addition to requiring the presence of marked premenstrual increases in five total premenstrual symptoms, the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria require that these symptoms are associated with “clinically significant distress or interference with work, school, usual activities, or relationships with others (e.g., avoidance of social activities; decreased productivity and efficiency at work, school, or home)” (APA 2013, p. 172). Therefore, in contrast to the preliminary PMDD criteria in DSM-IV-TR, which required impairment (APA 2000, p. 774), life impairment is optional for DSM-5 PMDD diagnosis if clinically significant distress is present. On the other hand, the text of DSM-5 emphasizes the high prevalence of impairment in PMDD, and highlights impairment as an additional metric for determining the clinical significance of symptoms. Further, previous work demonstrates that the average impairment and reduced quality of life found in PMDD is similar in severity to that of dysthymic disorder, and is not much lower than that of major depressive disorder (MDD; Halbreich et al. 2003).

Study Aim 1: Identify Unique Content Predictors of Premenstrual Relational, Occupational, and Recreational Impairment

The DSM-5 definition of PMDD differentiates between three different types of impairment: occupational (at work, at home, or in school), recreational (in social activities and hobbies), and relational (in relationships with others), and previous studies have compared the prevalence of these three types of impairment. One cross-national study of women reporting severe premenstrual symptoms found that relational impairment in the home (specifically in relationships with one’s partner and/or children) was the most commonly reported type of impairment, followed by impairment in one’s social life more generally (mapping onto both recreational and relational impairment), and finally occupational impairment (Hylan et al. 1999). As mentioned above, Halbreich et al. (Halbreich et al. 2003) compared the severity of the three types of impairment in PMDD to that of women affected by dysthymia and MDD. While impairment in social activities and hobbies (recreational) was worse in PMDD than in dysthymia, marital and parental impairment (relational) was equally severe in both disorders. When comparing women with PMDD to women diagnosed with MDD, women with PMDD showed similar relational impairment in social, marital, and parental relationships, while women with MDD had greater impairment occupationally and recreationally. Therefore, there is some evidence that relational impairment may be a particularly strong feature of PMDD, followed by significant impairment in both recreational and occupational arenas.

No work to date has examined which specific PMDD symptoms are uniquely linked to which specific types of impairment. From a therapeutic standpoint, a clearer understanding of the types of symptoms that drive different types of impairment would allow more targeted interventions aimed at reducing the impact of specific symptoms that underlie particularly troubling types of premenstrual impairment. Therefore, the first aim of the present study is to examine the unique relationships between premenstrual elevations in each DSM-5 PMDD symptom and premenstrual elevations in relational, occupational, and recreational impairment.

Study Aim 2: Identify the Optimal Number of Cyclic Symptoms for the Prediction of Clinically Significant Premenstrual Impairment

In addition to investigating the nature of the symptoms that cause impairment, we also utilized a standardized PMDD diagnostic protocol and Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves to investigate the number of premenstrual symptoms that best predicts significant premenstrual impairment. Several research groups have described the DSM-5 numerical requirement of five symptoms as “arbitrary” (Halbreich et al. 2003). Premenstrual functional impairment, though not required for diagnosis, can be seen as a “minimum threshold” at which diagnosis is necessary; should the number of symptoms required to predict premenstrual impairment be lower than the five symptoms required for DSM-5 diagnosis, this would signal a need for further investigation about the appropriateness of reducing the threshold of 5 total symptoms. Indeed, a small number of studies are suggestive of the presence of significant premenstrual impairment in women with fewer than five total cyclical symptoms per cycle (Halbreich et al. 2003; Dean et al. 2006; Hartlage et al. 2012). Therefore, the present study uses a dimensional, cycle-level analysis to pinpoint the number of symptoms at which clinically significant functional impairment can be most accurately predicted.

Hypotheses

The following hypotheses were generated prior to data analysis:

Hypothesis 1: Premenstrual elevations in core emotional symptoms will uniquely predict concurrent premenstrual elevations in impairment of all types.

Hypothesis 2: Premenstrual elevations in secondary psychological symptoms (especially cognitive symptoms) will uniquely predict concurrent premenstrual elevations in occupational domains, but will not uniquely predict recreational and relational impairment.

Hypothesis 3: Premenstrual elevations in physical symptoms will uniquely predict concurrent premenstrual elevations of recreational and occupational impairment, but will not predict relational impairment.

Hypothesis 4: When investigating the optimal number of symptoms to predict the presence of clinically significant premenstrual impairment, we predict that ROC curves will identify an optimal number of symptoms in a given cycle to predict concurrent impairment that is fewer than the five symptoms described in the DSM-5.

Methods

Between 2009 and 2015, naturally-cycling women ages 18–47 (M = 32.70, SD = 8.21) with regular cycles (21–35 days) were recruited through flyers and emails seeking women with premenstrual emotional symptoms. At a baseline visit, participants reported their medical and medication history and completed the SCID-I. Women were excluded for the following; an absence of self-reported premenstrual emotional symptoms; chronic medical disorders; histories of mania, substance dependence, or psychosis; any current SCID-I diagnosis; and certain medications (antidepressants, benzodiazepines, neuroleptics, or hormonal preparations). Next, eligible women completed daily reports of symptoms on the 24-item Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP; Endicott et al. 2006) for 1–4 menstrual cycles. The DRSP measures all symptoms of DSM-5 PMDD, as well as 3 items assessing relational, occupational, and recreational impairment. Participants noted daily external events they believed to have impacted daily mood; days in which participants reported the occurrence of a stressor not caused by symptoms (e.g., “my wallet was stolen”) were coded as missing so as not to confound analyses (<1% of daily data). Participants mailed in forms weekly to minimize retrospective reporting.

Characterizing and Diagnosing Premenstrual Changes at the Cycle Level

The Carolina Premenstrual Assessment Scoring System (C-PASS; Eisenlohr-Moul et al. 2016) is a standardized, computerized scoring system for diagnosing symptoms, cycles, and women with the DSM-5 PMDD symptom pattern on the basis of daily DRSP symptom ratings. For each symptom in each cycle, two C-PASS output variables were generated and used in the present study: (1) a dimensional variable representing the degree to which the symptom is elevated in the premenstrual week (days -7 to -1 where day -1 is the day prior to menses) relative to the following postmenstrual week (days 4 to 10, where day 1 is the first day of menses), and (2) a diagnostic decision variable (yes/no) reflecting whether or not the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for a clinically significant premenstrual elevation in that symptom have been met. For each item, the percent premenstrual elevation variable was calculated as: the average rating during the premenstrual week minus the average rating during the postmenstrual week, divided by the range of scale used by the participant across all observations and multiplied by 100. The dichotomous diagnostic decision variable was determined on the basis of the following criteria (C-PASS symptom diagnostic criteria; Eisenlohr-Moul et al., 2016): First, the symptom must show a relative premenstrual symptom elevation that is greater than or equal to 30%. Second, the symptom must show absolute clearance, defined as a maximum postmenstrual week value less than or equal to 3 (“Mild”). Third, the symptom must show sufficient absolute severity, defined as a premenstrual week maximum severity level greater than or equal to 4 (“Moderate”). Finally, these clinically significant symptoms must show sufficient premenstrual duration, defined as at least two days in the premenstrual week in which the symptom is greater than or equal to 4 (“Moderate”). If all four of these criteria are met, the symptom meets criteria for the symptom pattern described in DSM-5 PMDD in the present cycle. For the purposes of the present study, each DRSP item in each cycle received both a premenstrual elevation score and a dichotomous diagnostic decision. At the cycle level, we further calculated (1) the number of DSM-5 symptoms meeting the C-PASS diagnostic criteria outlined above, and (2) a binary outcome variable indicating whether or not at least one of the three impairment items met the four C-PASS criteria described above (coded as 0 = No,1 = Yes)1.

Symptom Content Domains

DSM-5 PMDD symptoms are heterogeneous. In our analyses of the nature of symptoms predicting impairment, we considered as predictors of impairment only the DRSP items that are not behaviorally consistent with impairment themselves in order to avoid criterion contamination. These decisions are outlined in Table 1. The DSM-5 definition of PMDD offers the following structure for organizing the symptoms: Criterion B covers the core emotional symptoms (depression, hopelessness, worthlessness/guilt, anxiety, mood swings, rejection sensitivity, anger/irritability), while Criterion C includes the secondary psychological symptoms (less interest, difficulty concentrating, overwhelm/can’t cope, and out of control) along with the physical symptoms (lethargy/tired, breast tenderness, swelling and bloat, headache, and joint or muscle pain).

Table 1.

Mapping the DSM-5 PMDD Content onto the Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP) and Symptom Categories for the Present Paper

| DSM-5 | DRSP | Symptom Content Domain in this Paper |

|---|---|---|

| CRITERION B: CORE EMOTIONAL SYMPTOMS | ||

| 1. Marked affective lability (e.g., mood swings; feeling suddenly sad or tearful, or increased sensitivity to rejection) | DRSP 5. Had mood swings (e.g. suddenly felt sad or tearful) | Included as core emotional symptoms |

| DRSP 6. Was more sensitive to rejection or my feelings were easily hurt | ||

| 2. Marked irritability or anger or increased interpersonal conflicts | DRSP 7. Felt angry, irritable | |

| DRSP 8. Had conflicts or problems with people | Not included, since interpersonal conflicts are a behavioral symptom which constitutes impairment in and of itself | |

| 3. Marked depressed mood, feelings of hopelessness, or self-deprecating thoughts | DRSP 1. Felt depressed, sad, “down” or blue | Included as core emotional symptoms |

| DRSP 2. Felt hopeless | ||

| DRSP 3. Felt worthless or guilty | ||

| 4. Marked anxiety, tension, and/or feelings of being keyed up or on edge | DRSP 4. Felt anxious, “keyed up”, or “on edge” | |

| CRITERION C: SECONDARY PSYCHOLOGICAL AND PHYSICAL SYMPTOMS | ||

| 1. Decreased interest in usual activities (e.g. work, school, friends, hobbies) | DRSP 9. Had less interest in usual activities (e.g. work, school, friends, hobbies) | Included as secondary psychological symptoms |

| 2. Subjective difficulty in concentration | DRSP 10. Had difficulty concentrating | |

| 3. Lethargy, easy fatigability, or marked lack of energy | DRSP 11. Felt lethargic tired, fatigued, or had a lack of energy | Included as physical symptom |

| 4. Marked change in appetite; overeating; or specific food cravings | DRSP 12. Had increased appetite or overate | Not included, since changes in eating and sleeping are behavioral symptoms which constitute impairment in and of themselves |

| DRSP 13. Had specific food cravings | ||

| 5. Hypersomnia or Insomnia | DRSP 14. Slept more, took naps, found it hard to get up | |

| DRSP 15. Had trouble getting to sleep, staying asleep | ||

| 6. A sense of being overwhelmed or out of control | DRSP 16. Felt overwhelmed, that I couldn’t cope | Included as secondary psychological symptoms |

| DRSP 17. Felt out of control | ||

| 7. Physical symptoms such as breast tenderness or swelling, joint or muscle pain, sensation of “bloating”, or weight gain | DRSP 18. Had breast tenderness | Included as physical symptoms |

| DRSP 19. Had breast swelling, felt bloated, or had weight gain | ||

| DRSP 21. Had joint or muscle pain | ||

| Not included in DSM-5 PMDD | DRSP 20. Had headache | |

Analytic Plan

The first aim of the present study was to determine which DSM-5 premenstrual symptoms are most uniquely and robustly tied to premenstrual elevations in impairment. Analyses serving this purpose were carried out in two-level multilevel models (in SAS PROC MIXED) with cycles nested within women. Indices of premenstrual impairment elevation (relational, occupational, and recreational) were each predicted in a series of three increasingly complex models: (Model 1) a model predicting premenstrual elevation of impairment from premenstrual elevation of each of the core emotional symptoms, (Model 2) a similar model adding premenstrual elevation of secondary psychological symptoms as additional predictors, and (Model 3) a model further adding premenstrual elevation of physical symptoms as predictors. As outlined in table 1, three symptoms listed within the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria (interpersonal conflict, sleeping more or trouble sleeping, and food cravings or increased appetite or overeating) were not included in these analyses, as they were considered to constitute impairment themselves and their inclusion may have led to criterion contamination2. These symptoms were only included as predictors in zero-order individual models.

The second aim of the present paper was to estimate the optimal number of symptoms per cycle for predicting a pattern of premenstrual impairment consistent with the DSM-5 PMDD diagnosis (Eisenlohr-Moul et al. 2016). Corresponding analyses firstly included multilevel logistic models in SAS PROC GLIMMIX (cycles nested within women) predicting the presence of a C-PASS-defined PMDD pattern in any of the three impairment variables from the number of DSM-5 PMDD symptoms showing the same C-PASS-defined pattern in the same cycle. Next, receiver operating curves were constructed using the SAS ROCPLOT macro, and associated area under the curve (AUC) values were calculated for the prediction of the presence of significant cyclical impairment from the number of symptoms meeting criteria in the same cycle. Finally, the ROCPLOT macro was also used to calculate the efficiency criterion; this criterion is a prevalence (p)-weighted method of deriving an optimal cut point (Efficiency = p×Sensitivity + (1−p)×Specificity) for predicting the presence of a binary outcome (in this case, the presence of significant cyclical impairment). The percentage of cycles showing significant cyclical impairment in at least one of the three categories (occupational, recreational, or relational; as defined by the C-PASS criteria for a given symptom; see above) was 30.2%; therefore, the efficiency of each cut point was calculated as (.30 × Sensitivity) + (.70 × Specificity). For one, this efficiency method was chosen over methods (e.g., Youden index) that utilize a 50% base rate, since such a base rate is clearly inaccurate on the basis of our sample prevalence of cyclical impairment. This method was also chosen over methods that consider the cost benefit ratio of false positives and false negatives, because it is not yet clear that under- or over-diagnosis of premenstrual impairment has a greater cost.

Results

Two hundred and sixty-seven women contributed 563 cycles. At the cycle level, 149 cycles (26.4%) met C-PASS symptom criteria on at least one of the impairment items. 170 cycles (30.2% of the sample) received a PMDD diagnosis (i.e., >=5 cyclical symptoms, with at least one cyclical affective symptom). 200 women provided a sufficient number of cycles (i.e., at least two) to make a person-level diagnosis. At the person level, 38 women (19%) of women met C-PASS criteria for DSM-5 PMDD (as previously reported in Eisenlohr-Moul et al., 2016). As noted above, the prevalence of PMDD is roughly 5.5% of the population; the higher prevalence rate demonstrated here is indicative of the fact that women were recruited for retrospective self-report of premenstrual symptoms.

Which Symptoms Most Strongly Predict Severity of Premenstrual Impairment?

Results of multilevel regressions predicting the degree of premenstrual elevation in each type of impairment from the degree of premenstrual elevation in each of the DRSP items separately can be found in Table 2. Severity of premenstrual elevation in each of the DRSP items were significantly related to severity of each type of premenstrual impairment elevation in the same cycle. Next, in order to determine which DRSP items explained unique variance in the severity of each premenstrual impairment outcome, we conducted three-step multiple regressions for each type of impairment to investigate which premenstrual symptom content domain is most tightly linked with premenstrual impairment elevations in the same cycle. Results of these models are summarized in the following sections.

Table 2.

Fixed Effects Estimates for Individual Predictor Models Predicting Degree of Premenstrual Elevation in Three Different Types of Impairment from Premenstrual Elevations in all other DRSP Items

| Premenstrual Impairment Elevation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| DRSP Item | Occupational | Recreational | Relational |

| Premenstrual Elevation of Core Emotional Symptoms | |||

| Depression | .15*** | .14*** | .13*** |

| Hopelessness | .15*** | .14*** | .13*** |

| Worthlessness/Guilt | .14*** | .14*** | .14*** |

| Anxiety | .13*** | .13*** | .15*** |

| Mood Swings | .16*** | .15*** | .16*** |

| Rejection Sensitivity | .16*** | .15*** | .17*** |

| Anger/Irritability | .15*** | .14*** | .17*** |

| Interpersonal Conflict | .14*** | .15*** | .20*** |

| Premenstrual Elevation of Secondary Symptoms | |||

| Low Interest | .18*** | .17*** | .15*** |

| Poor Concentration | .18*** | .16*** | .14*** |

| Lethargic/Tired | .17*** | .15*** | .12*** |

| Appetite/Overate | .12*** | .12*** | .12*** |

| Food Cravings | .12*** | .11*** | .11*** |

| Slept More | .16*** | .14*** | .11*** |

| Trouble Sleeping | .12*** | .12*** | .10*** |

| Overwhelm | .18*** | .17*** | .18*** |

| Out of Control | .17*** | .16*** | .17*** |

| Breast Tenderness | .10*** | .10*** | .12*** |

| Swelling/Bloating | .12*** | .12*** | .12*** |

| Headache | .09*** | .11*** | .08*** |

| Joint/Muscle Pain | .12*** | .13*** | .11*** |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Predictors are standardized using the full sample; therefore, estimates can be interpreted as the impact of a one standard-deviation increase in the predictor on premenstrual elevation of the outcome (e.g., Estimate = .15 can be interpreted as meaning that a one standard deviation increase in the predictor is associated with a 15% greater premenstrual elevation of impairment over one’s follicular baseline).

Predicting Premenstrual Elevations in Occupational Impairment

In the first step of this multiple multilevel regression depicted in Table 3, greater premenstrual elevations in core emotional symptoms significantly predicted greater premenstrual elevation of occupational impairment in the same cycle. However, when secondary psychological symptoms were added as predictors, these core emotional symptoms were no longer predicted unique variance in occupational impairment—in contrast, all of the secondary psychological premenstrual symptoms uniquely predicted greater premenstrual occupational impairment over and above variance accounted for by the core emotional symptoms. When physical symptoms were added in the third step, all secondary psychological symptoms remained significant predictors of premenstrual occupational impairment, and several of the physical symptoms (lethargy/tiredness, swelling/bloating, and headache) also predicted unique variance in premenstrual occupational impairment. To summarize, secondary cognitive and psychological symptoms and physical symptoms, and not the core emotional symptoms, were uniquely linked with the degree of premenstrual occupational impairment in the same cycle.

Table 3.

Fixed Effects Estimates for Multiple Multilevel Regression Models Predicting Degree of Premenstrual Elevation in Impairment from Premenstrual Elevations in Core Emotional, Secondary Psychological, and Secondary Physical Symptoms in the Same Cycle

| Parameter | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |

|

|

||||||

| Outcome: Premenstrual Elevation in Occupational Impairment this Cycle | ||||||

| Intercept | .174 | .009 | .173 | .007 | .173 | .007 |

| Premenstrual Elevation of Core Emotional Symptoms | ||||||

| Depression | .029* | .014 | .021 | .012 | .019 | .012 |

| Hopelessness | .024 | .016 | −.013 | .014 | −.004 | .014 |

| Worthlessness/Guilt | .035* | .015 | .002 | .013 | .000 | .012 |

| Anxiety | .005 | .013 | −.015 | .011 | −.019 | .011 |

| Mood Swings | .030 | .016 | .000 | .014 | −.006 | .013 |

| Rejection Sensitivity | .040** | .015 | .015 | .013 | .012 | .012 |

| Anger/Irritability | .052*** | .014 | .019 | .012 | .011 | .012 |

| Premenstrual Elevation of Secondary Psychological Symptoms | ||||||

| Low Interest | .058*** | .012 | .040*** | .012 | ||

| Poor Concentration | .061*** | .012 | .044*** | .012 | ||

| Overwhelm/Can’t Cope | .047*** | .013 | .041** | .013 | ||

| Out of Control | .046*** | .012 | .040*** | .012 | ||

| Premenstrual Elevation of Secondary Physical Symptoms | ||||||

| Lethargic/Tired | .040*** | .011 | ||||

| Breast Tenderness | −.010 | .010 | ||||

| Swelling/Bloating | .023* | .011 | ||||

| Headache | .018* | .008 | ||||

| Joint/Muscle Pain | .015 | .008 | ||||

| Parameter | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |

|

|

||||||

| Outcome: Premenstrual Elevation in Recreational Impairment this Cycle | ||||||

| Intercept | .153 | .008 | .154 | .007 | .154 | .007 |

| Premenstrual Elevation of Core Emotional Symptoms | ||||||

| Depression | .019 | .014 | .016 | .013 | .017 | .012 |

| Hopelessness | .021 | .016 | −.026 | .014 | −.021 | .014 |

| Worthlessness/Guilt | .051*** | .014 | .029* | .013 | .028* | .012 |

| Anxiety | .009 | .012 | −.017 | .011 | −.019 | .011 |

| Mood Swings | .023 | .015 | −.006 | .014 | −.014 | .013 |

| Rejection Sensitivity | .031* | .014 | .015 | .013 | .010 | .012 |

| Anger/Irritability | .051*** | .014 | .024* | .012 | .019 | .012 |

| Premenstrual Elevation of Secondary Psychological Symptoms | ||||||

| Low Interest | .069*** | .012 | .059*** | .012 | ||

| Poor Concentration | .033** | .012 | .023* | .011 | ||

| Overwhelm/Can’t Cope | .050*** | .013 | .039** | .013 | ||

| Out of Control | .039** | .012 | .029* | .012 | ||

| Premenstrual Elevation of Secondary Physical Symptoms | ||||||

| Lethargic/Tired | .016 | .011 | ||||

| Breast Tenderness | −.001 | .010 | ||||

| Swelling/Bloating | .014 | .011 | ||||

| Headache | .023** | .008 | ||||

| Joint/Muscle Pain | .033*** | .008 | ||||

| Parameter | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |

|

|

||||||

| Outcome: Premenstrual Elevation in Relational Impairment this Cycle | ||||||

| Intercept | .196 | .008 | .194 | .007 | .195 | .007 |

| Premenstrual Elevation of Core Emotional Symptoms | ||||||

| Depression | −.020 | .012 | −.018 | .011 | −.016 | .011 |

| Hopelessness | .005 | .013 | −.030* | .013 | −.030* | .013 |

| Worthlessness/Guilt | .040*** | .012 | .022** | .009 | .023* | .011 |

| Anxiety | .025* | .011 | .009 | .010 | .009 | .010 |

| Mood Swings | .022 | .013 | .005 | .012 | .004 | .012 |

| Rejection Sensitivity | .056*** | .012 | .043*** | .011 | .040*** | .011 |

| Anger/Irritability | .092*** | .012 | .076*** | .011 | .074*** | .011 |

| Premenstrual Elevation of Secondary Psychological Symptoms | ||||||

| Low Interest | .030** | .010 | .031** | .011 | ||

| Poor Concentration | −.023* | .010 | −.022* | .011 | ||

| Overwhelm/Can’t Cope | .081*** | .012 | .080*** | .012 | ||

| Out of Control | .037*** | .011 | .032*** | .011 | ||

| Premenstrual Elevation of Secondary Physical Symptoms | ||||||

| Lethargic/Tired | −.012 | .010 | ||||

| Breast Tenderness | −.001 | .009 | ||||

| Swelling/Bloating | .016 | .010 | ||||

| Headache | .003 | .007 | ||||

| Joint/Muscle Pain | .010 | .008 | ||||

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Several items of the DRSP are not included in this analysis due to their behavioral nature, which would be expected to overlap with the impairment outcome. Predictors are standardized using the full sample; therefore, estimates can be interpreted as the impact of a one standard-deviation increase in the predictor on premenstrual elevation of the outcome (e.g., Estimate = .052 can be interpreted as meaning that a one standard deviation increase in the predictor is associated with a 5.2% greater premenstrual elevation of impairment over one’s follicular baseline).

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Several items of the DRSP are not included in this analysis due to their behavioral nature, which would be expected to cause substantial overlap with the impairment outcome. Predictors are standardized using the full sample; therefore, estimates can be interpreted as the impact of a one standard-deviation increase in the predictor on premenstrual elevation of the outcome (e.g., Estimate = .092 can be interpreted as meaning that a one standard deviation increase in the predictor is associated with a 9.2% greater premenstrual elevation of impairment).

Predicting Premenstrual Elevations in Recreational Impairment

In the first step of this multiple multilevel regression depicted in Table 4, greater premenstrual elevations in the core emotional symptoms predicted greater premenstrual elevation of recreational impairment. When secondary psychological symptoms were added, rejection sensitivity no longer predicted unique variance in recreational impairment, whereas each of the secondary psychological symptoms predicted greater premenstrual recreational impairment. When physical symptoms were added in the third step, all secondary psychological symptoms remained significant predictors of premenstrual recreational impairment, and of the core emotional symptoms only worthlessness/guilt remained a significant predictor. Two physical symptoms (headache and joint/muscle pain) also accounted for unique variance in recreational impairment. To summarize, the core emotional symptom of worthlessness/guilt, each of the secondary psychological symptoms, and some physical symptoms were uniquely linked with the degree of premenstrual impairment in recreational activities in the same cycle.

Predicting Premenstrual Elevations in Relational Impairment

In the first step of this multilevel regression depicted in Table 5, the core emotional symptoms significantly predicted greater premenstrual relational impairment. When secondary psychological symptoms were added, anxiety was no longer uniquely predictive of relationship impairment, and most of the secondary psychological symptoms (low interest, overwhelm, and feeling out of control) uniquely predicted greater premenstrual relational impairment. Adding physical symptoms in the third step did not significantly alter the results; physical symptoms were not uniquely linked to premenstrual relational impairment. Of note, two counterintuitive effects also emerged in the second step; when secondary psychological symptoms were added to the model, both hopelessness and poor concentration were associated with less premenstrual relational impairment. To summarize, premenstrual relational impairment was uniquely predicted by the core emotional symptoms of worthlessness/guilt, rejection sensitivity, and anger/irritability, as well as the secondary psychological symptoms of low interest, overwhelm, and feeling out of control; none of the physical symptoms were uniquely predictive of premenstrual relational impairment.

What is the Optimal Total Number of DSM-5 Symptoms in a Given Cycle to Predict the Presence of Clinically Significant Premenstrual Impairment?

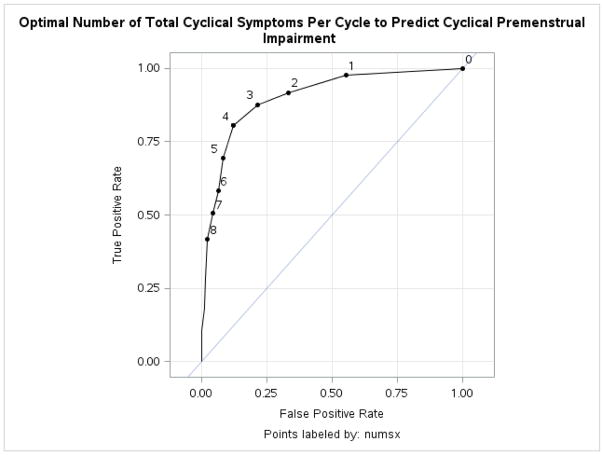

As expected, multilevel models revealed that the total number of symptoms meeting criteria in a given cycle was indeed predictive of whether or not that same cycle demonstrated significant premenstrual impairment (Estimate = .59, SE = .049, t(295) = 11.99, p < .0001; Odds Ratio = 1.76, 95% CI: 1.76 to 3.05). This odds ratio indicates that, for each one-symptom increase in the number of total DSM-5 symptoms meeting C-PASS criteria per cycle, there is a 76% increase in the odds of meeting C-PASS criteria for impairment (in at least one impairment domain) in the same cycle. The area under the ROC curve was .90 (95% CI: .87 to .92). Based on the efficiency criterion, the optimal number for predicting the presence of clinically significant cyclical impairment was 4 symptoms per cycle (see Figure 1). Sensitivity decreased and specificity increased as the threshold total number of symptoms was increased; true positive (hit) rate decreased linearly from 3–6 symptoms (3: 87%, 4: 80%, 5: 69%, 6: 58%), and false positive rate also decreased linearly from 3–6 symptoms (3: 21%, 4: 12%, 5: 24%, 6: 6.4%). Therefore, despite the fact that the DSM-5 does not require the presence of cyclical impairment to make the diagnosis of PMDD, this ROC analysis suggests that the number of DSM-5 symptoms per cycle at which significant cyclical impairment might be optimally predicted (in a typical research sample of women recruited for retrospective report of premenstrual emotional symptoms) is four symptoms—fewer than the five symptoms per cycle currently required for the official diagnosis of DSM-PMDD. Of note, results were identical when the criteria for impairment cycles were adjusted to require both one emotional symptom meeting criteria and one impairment symptom meeting criteria.

Figure 1.

ROC Curve Describing the Optimal Number of Total Cyclical DSM-5 Symptoms in a Given Cycle for Predicting Premenstrual Functional Impairment in the Same Cycle

Note. N = 563 Cycles; AUC = .90; Cut point Based on Efficiency Criterion = 4; Points are labeled by number of DSM-5 PMDD symptoms meeting C-PASS criteria.

Discussion

Recently, the American Psychiatric Association (2013) has acknowledged accumulating evidence regarding the validity and clinical significance of severe premenstrual affective symptoms in some women (Epperson et al. 2012) by making PMDD a full diagnostic category in DSM-5. Despite the fact that impairment is not strictly required for the diagnosis of PMDD in DSM-5, previous work has highlighted the high prevalence and impact of relational, recreational, and occupational impairment associated with premenstrual symptoms, with several studies indicating that PMDD is associated with impairment similar to that of other major affective disorders (Halbreich et al. 2003). The present study sought to provide information about the types and number of premenstrual symptoms that are most relevant to premenstrual impairment.

Results of hypothesis tests were mixed. Hypothesis 1 predicted that premenstrual elevations in core emotional symptoms would account for unique variance in concurrent premenstrual elevations in all three types of impairment; this was partially supported, although only interpersonal emotions such as shame, anger, and rejection sensitivity were consistently associated with impairment, and these associations were often not significant after controlling for secondary psychological symptoms. Hypothesis 2 predicted that premenstrual elevations in secondary psychological symptoms (especially the cognitive symptoms) would predict unique variance in concurrent premenstrual elevations in occupational function, but not in relational or recreational domains. This hypothesis was also partially supported; secondary psychological symptoms were robustly and uniquely predictive of all three types of impairment over and above the influences of emotional and physical symptoms. Hypothesis 3 predicted that premenstrual elevations in physical symptoms would account for unique variance in concurrent premenstrual elevations of recreational and occupational impairment, but would not predict relational impairment. This hypothesis was supported; physical symptoms predicted the degree of recreational and occupational, but not relational, impairment. Finally, hypothesis 4 predicted that the optimal number of symptoms in a given cycle to predict concurrent impairment would be fewer than the five symptoms described in the DSM-5; this hypothesis was also supported, as four symptoms consistently emerged as the most defensible numeric threshold for predicting the presence of premenstrual impairment, even when a number of modifications were made to the impairment criterion.

Zero-order relationships revealed that premenstrual increases in all symptoms were significantly associated with premenstrual increases in all three types of impairment, indicating general covariation of premenstrual increases in distress, cognitive dysregulation, physical discomfort, and general life impairment among these women. Further, multiple multilevel regression models identified a variety of unique predictors of impairment in each domain. Surprisingly, although core emotional symptoms were often unique predictors of impairment outcomes in the first model, they usually became nonsignificant predictors with the inclusion of psychological and physical symptom predictors in later models. In contrast, results indicated that the secondary DSM-5 psychological symptoms predicted unique variance in premenstrual functional impairment in a given cycle over and above the variance accounted for by both emotional and physical symptoms. These secondary psychological symptoms could be broadly characterized as representing failures of executive cognitive functions, such as failures of attention (“difficulty concentrating”), failures of goal direction (“less interest in usual activities”; this may also reflect deficits in reward processing), and failures to initiate or sustain self-regulation (“overwhelmed, can’t cope” and “out of control”). The strong predictive validity of these items in the present study may indicate that the status of these psychological symptoms as “secondary” should be reconsidered in future iterations of PMDD diagnostic criteria. On the other hand, these results may simply indicate that core emotional symptoms exert their effects on premenstrual impairment by increasing expression of secondary psychological symptoms (i.e., mediation of primary emotional effects via secondary cognitive failures). Additional work with finer-grained measurements (e.g., ecological momentary assessment) across the symptomatic luteal phase will be needed in order to accurately model the direction of relationships between specific emotional, psychological, and physical symptoms and experiences of functional impairment.

Among the emotional symptoms, premenstrual elevations in social emotional experiences, such as shame and guilt (“felt worthless, guilty”), rejection sensitivity, and anger and irritability consistently emerged as unique emotional predictors of premenstrual impairment across domains. These findings are consistent with previous work emphasizing the centrality of disturbed interpersonal experiences in women with PMDD (Hylan et al. 1999), and highlights the need for treatments that specifically target cyclical changes in interpersonal emotions, cognitions, and behaviors. In addition, both hopelessness and difficulty with concentration were linked with lower relational impairment, suggesting the possibility that interpersonal dysregulation also takes the form of social withdrawal in response to internalizing and cognitive symptoms. Meta-analytic analyses of RCT data demonstrate that cognitive behavioral therapies (CBT) can be helpful for PMDD (Busse et al. 2008; Kleinstäuber et al. 2012). However, the present results indicate that some women with PMDD may benefit from more targeted psychosocial interventions aimed specifically at resolving interpersonal affective and behavioral disturbances, which are often not directly addressed in CBT. Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT; Linehan, 2014), a skills-based intervention developed to treat pervasive emotional and interpersonal dysregulation such as that found in borderline personality disorder (BPD), could be useful to address deficits in the regulation of interpersonal emotions and behavior in PMDD. DBT includes traditional CBT skills for improving general emotion regulation; however, it also provides additional structure and skills for the therapist and the patient, including skills for promoting awareness of mood changes, maintaining the therapeutic relationship in the context of anger toward the therapist or urges to quit therapy, remaining functional in the face of emotional lability, and protecting key relationships in the context of strong emotional changes. Therefore, DBT may offer more targeted solutions for reducing premenstrual impairment–especially interpersonal impairment.

Consistent with the DSM-5 definition of PMDD as a psychiatric disorder, no physical symptoms were uniquely predictive of relational impairment in the present study, and physical symptoms had only small unique influences on recreational and occupational impairment. Severe physical symptoms in the form of dysmenorrhea must be ruled out prior to the making a diagnosis of DSM-5 PMDD; however, significant premenstrual physical complaints were common in the present study. Regardless, cycle-to-cycle variance in premenstrual physical symptoms does not appear to be strongly predictive of functional impairment in women being assessed for PMDD.

Regarding the number of symptoms predictive of impairment, results indicated that the number of DSM-5 symptoms meeting criteria per cycle (assessed for each cycle using the C-PASS (Eisenlohr-Moul et al. 2016) strongly predicted the presence of cyclical, clinically significant impairment in the same cycle. ROC analyses using the efficiency method indicated that four symptoms per cycle yielded the best prediction of cyclical impairment. This finding suggests that the five symptom threshold specified in DSM-5 may be too stringent, especially considering that the mere presence of clinically significant cyclical distress, without impairment, is sufficient for DSM-5 diagnosis (APA 2013). While the threshold of four symptoms may be optimal for predicting the presence of cyclical problems in functioning, a threshold of four is almost certainly too stringent to allow many women with clinically significant cyclical distress but no impairment to receive a necessary PMDD diagnosis. Therefore, the current DSM-5 threshold of five symptoms may lead to a “false negative” scenario among many women. These findings replicate previous findings (Hartlage et al. 2012), where four symptoms per cycle optimally predicted the presence of impairment. Notably, the present study replicated previous results despite utilizing a fine-grained, multilevel analytic approach and a cut point analysis (i.e., efficiency method) that accounted for the actual base rate of cyclical impairment in our sample.

There are limitations of the present study that should be acknowledged. There were no alternative instruments employed to collect prospective daily ratings on distress and impairment in addition to the DRSP. When further validating the DSM-5 PMDD diagnosis, future studies should evaluate the PMDD DSM-5 criteria of five total cyclical symptoms per cycle against other measures of clinically-significant cyclical distress and impairment. In addition, the results of the current study can be generalized only to the population of women seeking assessment for PMDD in research contexts.

The present work has important implications for the definition and diagnosis of PMDD. Further reflection on the prevalence, diagnostic significance, and causes of impairment in this disorder are clearly warranted. The present results suggest the need for more refined behavioral treatments that target the emotional, cognitive, and behavioral factors linked with relational impairment. In addition, the total number of symptoms per cycle required to warrant diagnosis may be fewer than previously thought.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH099076, T32MH093315, K99MH109667).

Footnotes

Some have argued that even mild premenstrual impairment is clinically significant; others have argued that impairment may persist into the postmenstrual phase even after the resolution of primary emotional symptoms. Therefore, all analyses were repeated using two alternative versions of the impairment criterion. The first alternative version removes the C-PASS requirement of absolute clearance (of impairment, in this case) during the postmenstrual week. The second alternative version alters the C-PASS threshold for absolute severity (premenstrual) from a rating of “4 – Moderate” to “3 – Mild”. Substitution of either of these alternative definitions for the impairment criterion did not substantively alter the results of ROC cut point selection of 4 symptoms presented in the Results section; therefore, the original definition of impairment cyclicity (using the original C-PASS criteria) was retained.

Inclusion of sleeping symptoms (sleeping more, trouble sleeping) and eating symptoms (food cravings, overeating) in predictive models did not substantively alter the effects of other symptoms on impairment. Only premenstrual elevations in the symptom of sleeping more were a significant predictor of greater premenstrual impairment in occupational (Estimate = .035, SE = .010, p = .0010) and recreational (Estimate = .033, SE = .010, p = .0021), but not relational domains. Premenstrual increases in trouble sleeping (i.e., insomnia) and eating symptoms (food cravings, overeating) were not uniquely associated with any type of impairment.

None of the authors have conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

Katja M. Schmalenberger, Heidelberg University, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Tory A. Eisenlohr-Moul, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Pallavi Surana, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

David R. Rubinow, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Susan S. Girdler, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®) American Psychiatric Association; Washington, D.C: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Busse JW, Montori VM, Krasnik C, Patelis-Siotis I, Guyatt GH. Psychological intervention for premenstrual syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2009;78:6–15. doi: 10.1159/000162296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean BB, Borenstein JE, Knight K, Yonkers K. Evaluating the Criteria Used for Identification of PMS. Journal of Women’s Health. 2006;15:546–555. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenlohr-Moul TA, Girdler SS, Schmalenberger KM, Dawson DN, Surana P, Johnson JL, Rubinow DR. Toward the Reliable Diagnosis of DSM-5 Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: The Carolina Premenstrual Assessment Scoring System (C-PASS) American Journal of Psychiatry. 2016 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15121510. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W. Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP): reliability and validity. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2006;9:41–49. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0103-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epperson CN, Steiner M, Hartlage SA, Eriksson E, Schmidt PJ, Jones I, Yonkers KA. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: evidence for a new category for DSM-5. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169:465–475. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11081302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbreich U, Borenstein J, Pearlstein T, Kahn LS. The prevalence, impairment, impact, and burden of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMS/PMDD) Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28:1–23. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartlage SA, Freels S, Gotman N, Yonkers K. Criteria for Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: Secondary Analyses of Relevant Data Sets. American Medical Association Archives of general psychiatry. 2012;69:300–305. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hylan T, Sundell K, Judge R. Impact of premenstrual symptoms on functioning and treatment-seeking: Experience from the United States, United Kingdom, and France. Journal of Women’s Health and Gender-Based Medicine. 1999;8:1043–1052. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1.1999.8.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinstäuber M, Witthöft M, Hiller W. Cognitive-Behavioral and Pharmacological Interventions for Premenstrual Syndrome or Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2012;19:308–319. doi: 10.1007/s10880-012-9299-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinow DR, Roy-Byrne P, Hoban MC, Gold PW, Post RM. Prospective assessment of menstrually related mood disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1984;141:684–686. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.5.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]