Abstract

Managing perioperative pain effectively is one the most important tasks that clinical veterinarians perform on a daily basis. The purpose of this article is to provide veterinarians with a basic understanding of the pathophysiology of perioperative pain and a working knowledge of the principles of effective therapy. First, the concepts of nociception, inflammatory pain, and neural plasticity are introduced. Second, the nociceptive and antinociceptive pathways that mediate normal physiological pain are described. Next, neural plasticity and the development of pathological pain are explained. And last, the concepts of preemptive, multimodal, and mechanism-based therapy are discussed.

Abstract

Résumé — Compréhension de la physiopathologie de la douleur périopératoire. Le traitement efficace de la douleur périopératoire est l’un des devoirs les plus importants dans le fonctionnement quotidien d’une clinique vétérinaire. Le but de cet article est de permettre au vétérinaire une compréhension de base de la physiopathologie de la douleur périopératoire et d’apporter une connaissance appliquée des principes d’une thérapie efficace. En premier lieu, les concepts de nociception, de douleur inflammatoire et de plasticité neurale sont abordés. Dans un deuxième temps, les voies nociceptives et anti-nociceptives qui transmettent la douleur physiologique normale sont décrites. Ensuite, la plasticité neurale et l’émergence des douleurs pathologiques sont expliquées. Enfin les concepts de thérapies préventives et multimodales et leurs mécanismes d’action sont discutés.

(Traduit par Docteur André Blouin)

Introduction

Managing perioperative pain effectively is one the most important tasks that clinical veterinarians perform on a daily basis. It is also a task that they are ethically obligated to perform well. A basic understanding of the pathophysiology of pain is needed before practitioners can manage perioperative pain in a safe and effective manner. With this understanding, the principles of pain management can be appreciated, and analgesic drugs and techniques can be selected on a more rational basis.

The terminology used to describe the pathophysiology of pain is confusing, so defining a few terms that are relevant to the management of perioperative pain is helpful. Nociception is defined as the neural response to noxious stimuli. The neural response is initiated by detection of a noxious stimulus and is completed by the subsequent transmission of encoded information to the brain. Pain, on the other hand, is a complex sensation that requires integration of nociceptive and other sensory information at the cortical level. Therefore, pain is defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience that is associated with actual or potential tissue damage.

Pain can be classified in several different ways. Anatomic (somatic or visceral pain) and temporal (acute or chronic pain) classification schemes have some clinical utility, but do not suggest appropriate analgesic therapy. Mechanistically, pain can also be classified as either inflammatory or neuropathic. As the names suggest, inflammatory pain is associated with tissue trauma and inflammation, while neuropathic pain is associated with nerve injury. Both types of pain can occur as a result of surgical trauma, but inflammatory pain is by far the most common type of pain and its physiology is better understood. Therefore, this article will focus on the pathophysiology of inflammatory pain during the perioperative period.

Perioperative pain is probably best classified as either physiological or pathological (1). Physiological pain is defined as the type of pain that animals experience on a regular basis. This type of pain requires noxious (highthreshold) input, is discrete (well-localized) and transient, and serves a protective function. Pathological pain, on the other hand, is defined as the type of pain that animals experience following severe trauma (surgical trauma). This type of pain requires non-noxious (lowthreshold) input, is diffuse and prolonged, and does not serve a protective function. Classifying pain in this way has 3 distinct advantages. First, this classification scheme is based on an understanding of normal nociceptive and antinociceptive pathways. Second, it recognizes that nociceptive processing changes, or demonstrates plasticity, in response to tissue trauma and inflammation. And third, it provides a conceptual framework for effective therapeutic intervention.

The purpose of this article is to provide clinical veterinarians with a basic understanding of the pathophysiology of perioperative pain and a working knowledge of the principles of effective therapy. This article begins by describing the nociceptive and antinociceptive pathways that mediate normal physiological pain. Next, neural plasticity and the development of pathological pain are explained. And last, the concepts of preemptive, multimodal, and mechanism-based therapy are discussed.

Nociceptive pathway

Nociception is a sequential process that includes transduction of noxious stimuli into electrical signals by duction peripheral nociceptors, conduction of encoded signals by afferent neurons to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, and subsequent transmission and modulation of the signals at both spinal and supraspinal levels (2,3). In its simplest form, the nociceptive pathway is a 3-neuron chain. The 1st neuron in the chain — the primary afferent neuron — is responsible for transduction of noxious stimuli and conduction of signals from the peripheral tissues to neurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. The 2nd neuron in the chain — the projection neuron — receives input from the primary afferent neurons and projects to neurons in the medulla, pons, midbrain, thalamus, and hypothalamus. These 3rd order, supraspinal neurons integrate signals from the spinal neurons and project to the subcortical and cortical areas where pain is finally perceived.

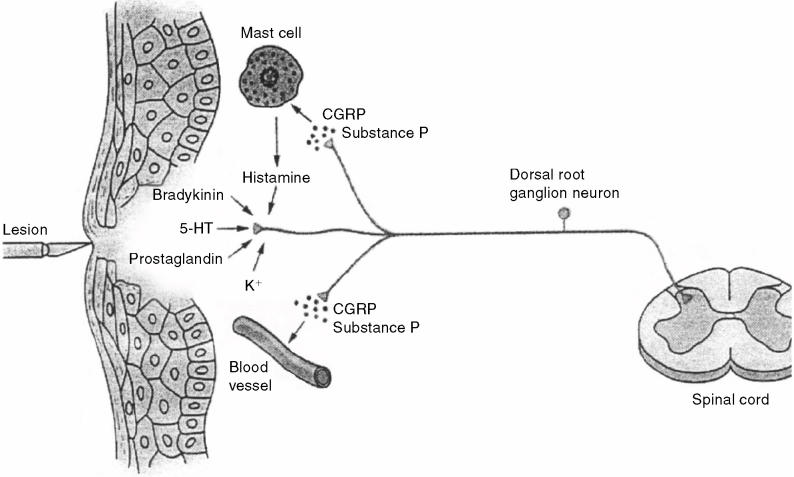

Primary afferent neurons are bipolar neurons. The cell bodies of these bipolar neurons are located in the dorsal root ganglia and their axons project peripherally to somatic and visceral tissues and centrally to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord (Figure 1). Some afferent neurons respond to noxious (high-threshold) stimuli and are called nociceptive neurons. These neurons have free nerve endings or nociceptors that are activated by noxious stimuli, and change or transduce these stimuli into electrical signals. Transduction is mediated by membranebound receptors that are activated by noxious mechanical (acid-sensing ion channel [ASIC]), thermal (vanilloid receptor-1 [VR1]), and chemical (purinergic receptor subtype-3 [P2X3]) stimuli (4). Somatic tissues have more nociceptors and smaller receptive fields, while visceral tissues have fewer nociceptors and larger receptive fields. These anatomic differences may account for some of the qualitative differences between somatic (discrete) and visceral (diffuse) pain. Other types of afferent neurons (large, myelinated A βfibers) respond to nonnoxious stimuli (touch) but not to noxious stimuli directly (2). However, they do help to shape (discriminate between mechanical and thermal) and attenuate (gate) nociceptive input at the spinal level.

Figure 1.

Peripheral nociceptors and primary afferent neurons. Peripheral nociceptors respond to mechanical, thermal, and nociceptive stimuli, and primary afferent neurons conduct encoded signals to neurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Tissue trauma leads to the release of inflammatory mediators that activate and sensitize nociceptors. Antidromal activation of nociceptive nerve terminals causes the release of substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide. Release of these neuropeptides causes mast cell degranulation, vasodilation and edema, and further activation and sensitization of nociceptors. 5-HT = serotonin, CGRP = calcitonin gene-related peptide (from Kandel Schwartz and Jessell, Principles of Neural Science, 4th edition, 2000, McGraw-Hill. Reproduced with permission of the McGraw-Hill Companies).

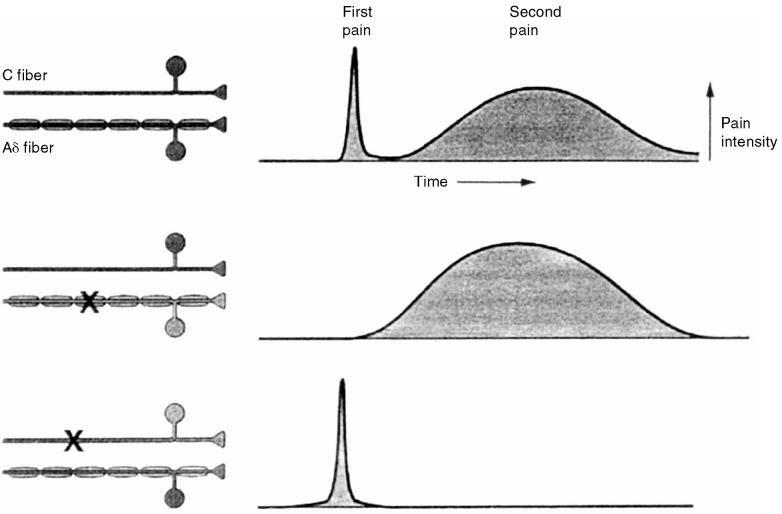

Four classes of nociceptors: mechanical, thermal, polymodal, and silent, have been described (2,5). Mechanical nociceptors respond to intense pressure and have small, myelinated A δfibers that conduct impulses at a velocity of 3 to 30 m/s. Thermal nociceptors respond to extreme temperatures and also have small, myelinated A δfibers that conduct impulses at a velocity of 3 to 30 m/s. Collectively, these 2 types of nociceptors are referred to as A δmechano-thermal nociceptors. Polymodal nociceptors respond to noxious mechanical, thermal, and chemical stimuli and have small, unmyelinated C fibers that conduct impulses at a velocity of less than 3 m/s. Small, myelinated A δfibers carry the nociceptive input responsible for the fast, sharp pain (first pain) that occurs immediately after injury; and small, unmyelinated C fibers carry the nociceptive input responsible for the prolonged, dull pain (second pain) that occurs several seconds later (Figure 2). Silent nociceptors are activated by chemical stimuli (inflammatory mediators) and respond to mechanical and thermal stimuli only after they have been activated. These nociceptors also have small, unmyelinated C fibers that conduct impulses at a velocity of less than 3 m/s. Sodium channels are responsible for membrane depolarization and impulse conduction in nociceptive and nonnociceptive afferent fibers. Nociceptive A δand C fibers have a type of sodium channel (tetrodotoxin [TTX]-resistant) that differs from that found in nonnociceptive A δfibers (TTX-sensitive), and are potential targets for therapeutic intervention (6).

Figure 2.

Nociceptive fibers. Small, myelinated A δ fibers carry the nociceptive input responsible for the fast, sharp pain (1st pain) that occurs immediately after injury. Small, unmyelinated C fibers carry the nociceptive input responsible for the prolonged, dull pain (2nd pain) that occurs several seconds later. X = fiber blockade (from Kandel Schwartz and Jessell, Principles of Neural Science, 4th edition, 2000, McGraw-Hill. Reproduced with permission of the McGraw-Hill Companies).

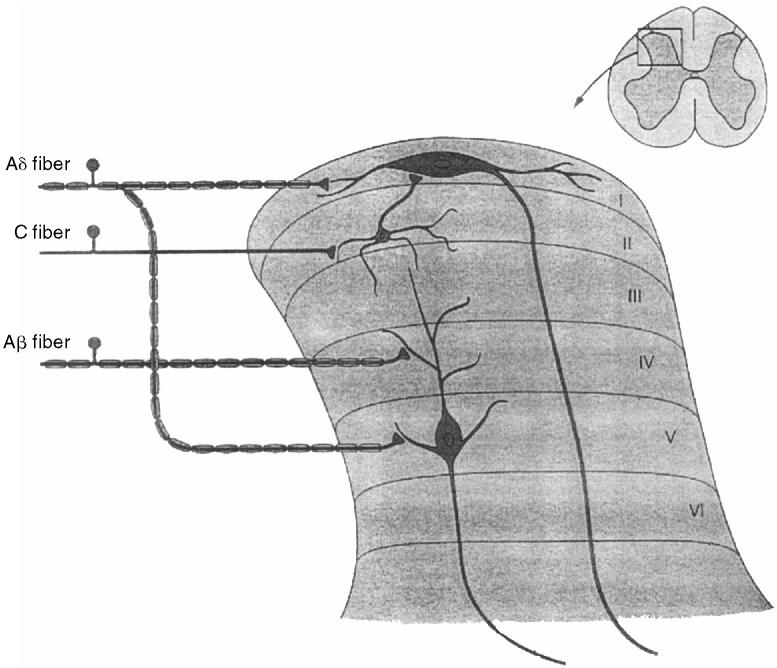

Nociceptive fibers synapse with 2nd order nociceptive neurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. There are 2 main types of nociceptive neurons in the dorsal horn (projection neurons and interneurons), and these neurons are organized into layers or laminae. Neurons that mediate nociception are located primarily in lamina I ate (substantia gelatinosa), lamina II (marginal layer), and lamina V (Figure 3). Projection neurons are located in laminae I and V and have axons that “project” to supraspinal 3rd-order neurons. Neurons located primarily in lamina I receive input directly from nociceptive A δand C fibers and are called nociceptive-specific neurons. Neurons located primarily in lamina V receive both nociceptive and nonnociceptive input (Aβ fibers) and are classified as wide dynamic range neurons. Inhibitory and excitatory interneurons are located in lamina II and receive input from nociceptive and nonnociceptive fibers. These interneurons play a key role in gating and modulating nociceptive input (7). A 3rd type of dorsal horn neuron (propriospinal neurons) extends over several spinal segments; it is responsible for segmental reflexes associated with nociception.

Figure 3.

Dorsal horn neurons. Nociceptive (A δand C) and nonnociceptive (Aβ) fibers synapse with projection neurons and interneurons located in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Dorsal horn neurons are organized into layers or laminae. Neurons that mediate nociception are located primarily in laminae I, II, and V. Neurons in lamina I receive input from nociceptive fibers and are called nociceptive-specific neurons. Neurons in lamina V receive input from both nociceptive and nonnociceptive fibers and are called wide dynamic range neurons. Inhibitory and excitatory interneurons are located in lamina II (from Kandel Schwartz and Jessell, Principles of Neural Science, 4th edition, 2000, McGraw-Hill. Reproduced with permission of the McGraw-Hill Companies).

Nociceptive Aδ and C fibers, as well as nonnociceptive fibers, corelease excitatory amino acids (glutamate, aspartate), and neuropeptides (substance P, neurokinin A, calcitonin gene-related peptide) that bind to receptors on dorsal horn neurons (8). With normal afferent input, glutamate binds to α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4- isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors and neuropeptides bind to neurokinin receptors. Activation of AMPA receptors is responsible for the generation of fast postsynaptic potentials that last a few milliseconds. Reuptake of glutamate from the synapse is rapid and its effects are restricted to neurons in the immediate area. Activation of neurokinin receptors is responsible for the generation of slow synaptic potentials that last several seconds, and it reinforces the effects of AMPA receptor activation. In addition to having a prolonged duration of action, neuropeptides diffuse away from the synapse and activate neurons outside of the immediate area. With intense afferent input, prolonged activation of AMPA and neurokinin receptors leads to progressive cellular depolarization and activation of additional types of glutamate larization receptors (N-methyl-D-aspartate [NMDA], metabotropic [G-protein-coupled]) on dorsal horn neurons.

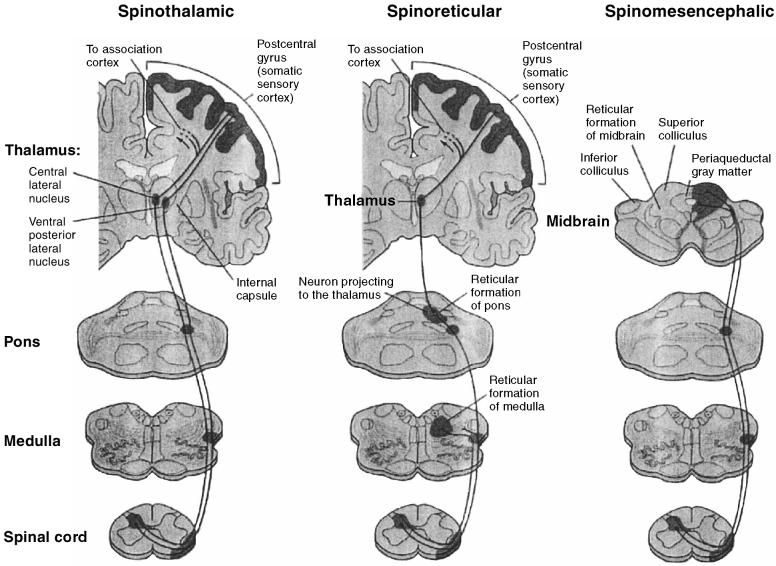

Most axons from nociceptive-specific and wide dynamic range neurons cross midline and communicate with supraspinal centers through 1 of 3 major ascending nociceptive pathways (Figure 4). The spinothalamic pathway is the major ascending nociceptive pathway; it is divided into medial and lateral components. The medial component projects to medial thalamic nuclei and then (via 3rd-order neurons) to the limbic system; it is responsible for transmission of nociceptive input involved with the affective-motivational aspect of pain. The lateral component projects to lateral thalamic nuclei and then to the somatosensory cortex; it is responsible for transmission of nociceptive input involved with the sensory-discriminative aspect of pain. The spinoreticular pathway projects to the reticular formation in the medulla and pons, to thalamic nuclei, and then to the somatosensory cortex. The reticular formation is critical to the integration of nociceptive input. Ascending reticular activity increases cortical activity, while descending reticular activity blocks other sensory activity. The spinomesencephalic tract projects to the reticular formation and to the periaqueductal gray matter. The periaqueductal gray matter plays a central role in the integration and modulation of nociceptive input at the supraspinal level. Two smaller ascending pathways are also involved in nociception. The cervicothalamic tract originates from neurons in the upper 2 cervical segments and projects to thalamic nuclei. The spinohypothalamic tract originates from neurons in dorsal horn and projects to autonomic control centers in the hypothalamus. The spinohypothalamic pathway is responsible for transmission of nociceptive input involved with cardiovascular and neuroendocrine responses to noxious stimuli, and it probably mediates some of the autonomic responses (changes in heart rate, arterial blood pressure, and respiratory rate) observed in animals anesthetized for surgical procedures.

Figure 4.

Ascending nociceptive pathways. Most axons from nociceptive-specific and wide dynamic range neurons cross midline and communicate with supraspinal centers through 1 of 3 major ascending nociceptive pathways. The spinothalamic pathway has medial and lateral components that project to the thalamus and then to the limbic system and somatosensory cortex. The spinoreticular pathway projects to the reticular formation in the medulla and pons, and then to the thalamus and somatosensory cortex. The spinomesencephalic pathway projects to the reticular formation and to the periaqueductal gray matter (from Kandel Schwartz and Jessell, Principles of Neural Science, 4th edition, 2000, McGraw-Hill. Reproduced with permission of the McGraw-Hill Companies).

Antinociceptive pathways

In addition to having ascending nociceptive pathways, animals have descending antinociceptive pathways that modulate nociceptive input at supraspinal and spinal levels (2,3). Practitioners must have a working knowledge of these normal pain-control pathways before they edge can appreciate the effects of anesthestic and analgesic drugs on these pathways and understand many of the principles of perioperative pain management.

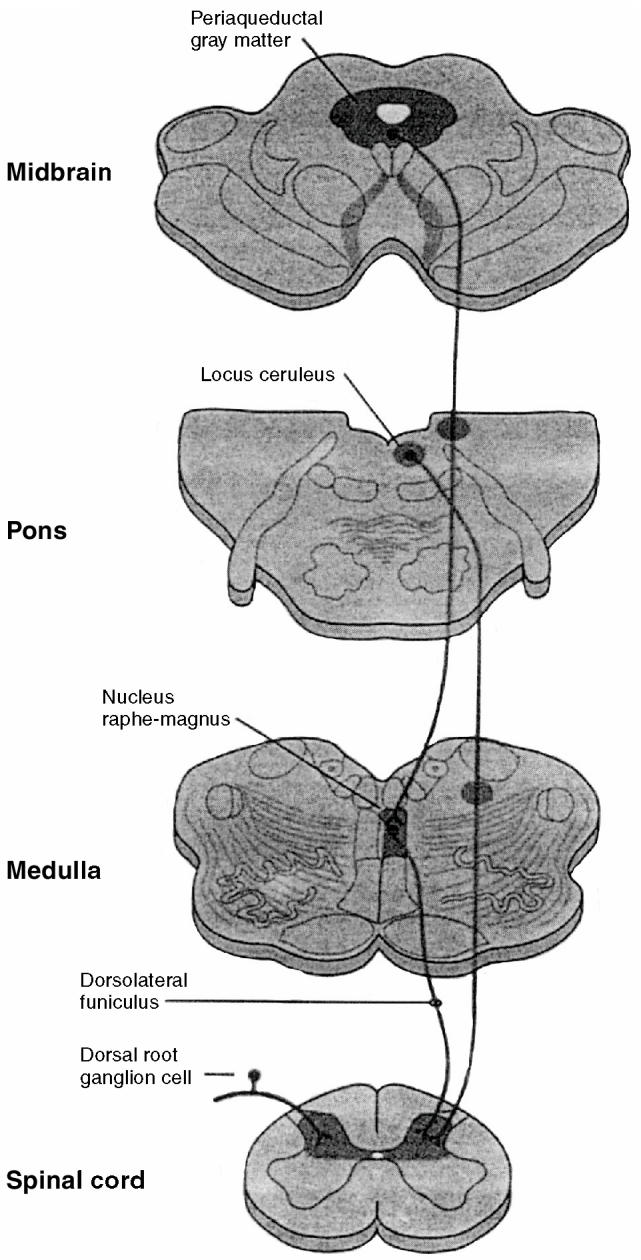

The descending antinociceptive pathways begin at the supraspinal level and project to neurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord (Figure 5). The periaqueductal gray matter (midbrain), locus ceruleus (pons), and nucleus raphemagnus (medulla) are important structures in the modulation of nociceptive input. The periaqueductal gray matter receives direct input from the thalamus, hypothalamus, and reticular formation, and indirect input thalamus, from the cerebral cortex. These midbrain neurons send projections to the nucleus raphemagnus and then to neurons in the dorsal horn. The locus ceruleus sends projections directly to dorsal horn neurons, and it may also receive input from the periaqueductal gray matter.

Figure 5.

Descending antinociceptive pathways. Serotonergic and noradrenergic neurons project from supraspinal levels to the neurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. The periaqueductal gray matter receives from higher centers and sends projections to the nucleus raphemagnus and then to dorsal horn neurons. The locus ceruleus sends projections directly to dorsal horn neurons and may also receive input from the periaqueductal gray matter (from Kandel Schwartz and Jessell, Principles of Neural Science, 4th edition, 2000, McGraw-Hill. Reproduced with permission of the McGraw-Hill Companies).

Endogenous opioids (β-endorphins, enkephalins, dynorphins), serotonin (5-HT), and norepinephrine are the main neurotransmitters involved in the descending antinociceptive pathways (9). Axons that originate in the nucleus raphemagnus release serotonin in the dorsal horn and comprise the “serotonergic” pathway. Similarly, axons that originate in the locus ceruleus release norepinephrine in the dorsal horn and comprise the “noradrenergic” pathway. Supraspinal release of opioid peptides activates both antinociceptive pathways, and supraspinal release of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) (mediated -by GABAA receptors) inhibits both antinociceptive pathways.

Opioid peptides modulate nociceptive input at spinal and supraspinal levels. All 3 types of opioid receptors (μ, κ, and δ) are present on nociceptive afferents (1st-order neurons) and on dorsal horn projection neurons, order and μand δreceptors are more common in the periaqueductal gray matter. At the supraspinal level, opioid queductal peptides not only activate the descending antinociceptive pathways, they also inhibit GABA-mediated inhibition of these same pathways (disinhibition). At the spinal level, opioid peptides act presynaptically to inhibit release of glutamate and neuropeptides from primary afferent neurons, and postsynaptically to inhibit (hyperpolarize) projection neurons.

Norepinephrine and alpha-2 adrenergic receptors also modulate nociceptive input at spinal and supraspinal levels, and they play a central role in modulation of nociceptive input. Alpha-2 receptors on noradrenergic neurons are sometimes called autoreceptors, and those on nonnoradrenergic neurons (nociceptive afferents) are called heteroceptors. At the supraspinal level, noradrenergic neurons in the locus ceruleus tonically inhibit the neurons of the noradrenergic pathway. Release of norepinephrine within the locus ceruleus activates postsynaptic autoreceptors, inhibiting the tonically active inhibitory neurons and activating the noradrenergic pathway (another example of disinhibition). At the spinal level, norepinephrine activates heteroceptors presynaptically, to inhibit release of glutamate and neuropeptides from primary afferent neurons, and postsynaptically, to inhibit (hyperpolarize) projection neurons. Other receptors (GABAB, gabapentin, cannabinoid) also appear to , play important roles in spinal modulation of nociceptive input, and they are potential targets for therapeutic intervention (6).

Neural plasticity and the development of pathological pain

Plasticity is defined as the ability of the nervous system to modify its function in response to different environmental stimuli. Peripheral and central sensitization occur mental in response to the barrage of nociceptive input that accompanies tissue trauma and play a central role in the development of pathological pain (1). Animals that have limited perioperative tissue trauma and inflammation will experience pain that is discrete, proportionate, and protective, and that resolves once the inflammatory response has subsided (physiological pain). Those that have extensive trauma and inflammation will have varying degrees of peripheral and central sensitization, and will experience pain that is diffuse, disproportionate, and debilitative, and that continues beyond resolution of the inflammatory process (pathological pain).

Peripheral sensitization occurs as a direct consequence of tissue trauma and inflammation (Figure 1) (4). Tissue trauma leads to the release of inflammatory mediators from damaged cells (H+, K+), plasma (bradykinin), platelets (serotonin), mast cells (histamine), and macrophages (cytokines). Damage to cell membranes also activates the arachidonic acid pathway, which leads to the production of prostaglandins and leukotrienes. Some inflammatory mediators activate nociceptors directly (bradykinin), while others sensitize nociceptors (prostaglandins). Stimulation of nociceptors also leads to antidromal (reverse) activation of nociceptive nerve terminals and release of substance P and calcitonin generelated peptide. Release of these peptides causes mast cell degranulation, vasodilation and edema, and further sensitization and activation of nociceptors (neurogenic inflammation). Sympathetic nerve terminals also contribute to the activation and sensitization of nociceptors by releasing norepinephrine and prostaglandins. Ultimately, the inflammatory response produces a “sensitizing soup” of chemical mediators that act synergistically to convert high-threshold nociceptors to low-threshold nociceptors. In other words, peripheral sensitization is characterized by a reduction in the activation threshold of peripheral nociceptors.

Central sensitization occurs as an indirect consequence of tissue trauma and inflammation, and it is contingent, to a large degree, on the development of peripheral sensitization (4). Repetitive stimulation of peripheral nociceptors leads to sustained release of glutamate and neuropeptides from afferent nerve fibers. Sustained activation of AMPA and neurokinin receptors on dorsal horn projection neurons leads to progressive cellular depolarization and activation of additional types of glutamate receptors (NMDA, metabotropic). These receptors are responsible for activating 2nd messenger systems, increasing intracellular calcium, and phosphorylating ion channels. These changes cause an activity-dependent increase in the excitability of dorsal horn projection neurons to subsequent nociceptive input. This process, which includes activation of NMDA receptors and the initial increase in the excitability of projection neurons, is called “windup,” and is the physiological trigger for central sensitization (10). Further stimulation of peripheral nociceptors causes additional long-term cellular changes in projection neurons that lead to an expansion of receptive fields and a reduction in activation thresholds for nonnoxious stimuli. Central sensitization, therefore, is characterized by an activity-dependent increase in excitability, an expansion of receptive fields, and an exaggerated response to both nociceptive and nonnociceptive stimuli (1).

Principles of effective therapy

As noted earlier, animals are presented for surgery with varying degrees of tissue trauma and inflammation. As a result, they have varying degrees of peripheral and central sensitization. Those admitted for elective surgical procedures (castration), which involve no preoperative tissue trauma and inflammation and have very little postoperative trauma and inflammation, will have a normal “physiological” response to pain that can be managed with conventional analgesic therapy (antiinflammatory drugs, opioids). Alternately, those admitted for nonelective surgical procedures (femoral fracture), which involve extensive tissue trauma and inflammation that has been present for several hours or days, will have a “pathological” response to pain that requires more aggressive analgesic therapy. Further, those admitted for nonelective surgical procedures (total ear canal ablation), which have extensive tissue trauma and inflammation that has been present for weeks or months, will have an extremely “pathological” response to pain that may be refractory to traditional types of analgesic therapy. Therefore, practitioners should examine animals closely on admission to determine the extent and duration of tissue trauma and inflammation, to estimate the degree of peripheral and central sensitization that is present, and to plan an effective pain management strategy that begins with preoperative analgesic therapy and continues through the intraoperative and postoperative periods.

At first glance, the notion that analgesics and local anesthetics should be given to animals that are already anesthethized and that are unable to consciously perceive pain seems irrational. However, practitioners must remember that most injectable (thiopental, propofol) and inhalational (halothane, isoflurane, sevoflurane) anesthetics simply produce unconciousness and do not substantially alter nociceptive processing. In fact, many injectable and inhalational anesthetics activate GABAA receptors and may inhibit the activation of descending antinociceptive pathways that should occur during surgery (11). The benzodiazepines (diazepam, midazolam) also activate GABAA receptors and may interfere with receptors and may interfere with supraspinal activation of these descending pathways. Alternately, the opioids and alpha-2 agonists act supraspinally to activate the descending antinociceptive pathways and spinally to inhibit transmission of ascending nociceptive input. Further, ketamine (an NMDA receptor antagonist) can prevent and, in some cases, reverse the development of central sensitization. Therefore, veterinarians should use anesthetic drugs that inhibit endogenous pain control mechanisms with discretion, and select drugs that activate these control mechanisms when possible.

Because the development of central sensitization is contingent on the development of peripheral sensitization, pain management strategies that target peripheral sensitization and conduction of nociceptive input by primary afferent fibers are generally more effective than those that target central sensitization directly. Atraumatic tissue handling is one of the most effective, as well as one of the most benign, methods to limit the development of peripheral and central sensitization and to reduce pain postoperatively. Regional anesthetic techniques are also relatively safe techniques, and they have the unique ability to produce complete blockade of peripheral nociceptive input and to prevent the development of central sensitization (1,12,13). In selected cases, nonsteroidal and steroidal antiinflammatory drugs can also be used perioperatively to reduce inflammation and peripheral sensitization.

In recent years, 3 perioperative pain management strategies have evolved that focus on limiting or preventing the development of peripheral and central sensitization, and, ultimately, pathological pain. The 1st strategy is called preemptive analgesia; it is based on the assumption that analgesic therapy initiated before surgery is more effective than therapy initiated after surgery (1,14–16). In other words, postoperative pain is easier to manage if peripheral and central sensitization can be limited or prevented by preoperative administration of analgesic drugs. This strategy also recognizes that most injectable and inhalation anesthetics do not alter nociceptive processing and that analgesic drugs and techniques should be used to prevent the development of central sensitization during anesthesia and surgery. Clinically, preemptive analgesia can be achieved by administering alpha-2 agonists and opioids as preanesthetics and by performing local anesthetic techniques before surgical procedures are started. The 2nd strategy is called multimodal analgesia; it is based on the theory that simultaneous administration of 2 or more classes of analgesic drugs is safer and more effective than monotherapy with a single class of drugs (17–19). This strategy exploits the synergistic effects of different classes of analgesic drugs (alpha-2 agonists and opioids), and it is associated with fewer side-effects because lower doses of individual drugs are used. Clinically, multimodal analgesia can be achieved by selecting drugs that produce sequential blockade of ascending nociceptive pathways (antiinflammatory drugs, local anesthetics, opioids) and activation of descending antinociceptive pathways (alpha-2 agonists). The 3rd strategy is called mechanism-based therapy; it is based on the theory that specific molecular mechanisms involved in nociception, antinociception, and the development of peripheral and central sensitiza- sensitization sensitization can be targeted to manage perioperative pain (6,20). Clinically, opioids and alpha-2 agonists can be used to target several different molecular mechanisms involved in nociception and antinociception at spinal and at supraspinal levels. Ketamine targets the NMDA receptor and spinal can prevent or reverse the development of central sensitization at the spinal level. In the near future, new classes of analgesic drugs that target novel receptors (GABAB, gabapentin, cannabinoid, TTX resistant sodium channels) involved in nociception may be developed.

With an understanding of the pathophysiology of perioperative pain and a working knowledge of the principles of therapy, veterinarians can manage pain more effectively by using drugs and techniques that are currently available. Anesthetic and pain management plans that illustrate the concepts of preemptive, multimodal, and mechanism-based therapy are outlined in Appendix 1. CVJ

Appendix 1. Anesthetic and pain management plans that illustrate the concepts of preemptive, multimodal, and mechanism-based therapy

| Healthy, 3 kg, female domestic shorthair scheduled for an onychectomy | |

|---|---|

| Premedication | Acepromazine: 0.1 mg/kg, IM |

| Oxymorphone: 0.05 mg/kg, IM | |

| Induction | Ketamine: 10 mg/kg, IM |

| Mask with 2% isoflurane. | |

| Place an endotracheal tube. | |

| Maintenance | 1% to 2% isoflurane delivered with oxygen using a nonrebreathing circuit |

| Regional anesthesia | Front paw blocks (12) |

| 0.5% bupivacaine: 0.1 mL/site | |

| Do not exceed a total dose of 2 mg/kg. | |

| Postoperative pain management | Ketoprofen: 1 to 2 mg/kg, SC |

| Comments | Use a surgical technique that minimizes tissue trauma and inflammation. |

| This is an elective procedure with no preexisting peripheral or central sensitization. | |

| Some of these drugs are not approved for use in cats in Canada. | |

| Healthy, 30 kg, male Labrador retriever scheduled for repair of a ruptured cranial cruciate ligament | |

|---|---|

| Premedication | Atropine: 0.05 mg/kg, IM |

| Medetomidine: 0.005 mg/kg, IM | |

| Hydromorphone: 0.05 mg/kg, IM | |

| Induction | Thiopental: 5 mg/kg, IV slowly to effect |

| Place endotracheal tube. | |

| Maintenance | 1% to 2% isoflurane delivered with oxygen using a rebreathing circuit |

| Regional anesthesia | Lumbosacral epidural (13) |

| 0.5% bupivacaine (preservative-free): 1 mL/5 kg | |

| 2.5% morphine (preservative-free): 0.2 mg/kg | |

| Use strict aseptic technique. | |

| Postoperative pain management | Meloxicam: 0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg, SC |

| Comments | Use a surgical technique that minimizes tissue trauma and inflammation. |

| This is an elective procedure with limited preexisting peripheral and central sensitization. | |

| Some of these drugs are not approved for use in dogs in Canada. | |

kg — kg bodyweight

Footnotes

Reprints will not be available from the author.

This paper was presented at the symposium on Perioperative Pain Control held at the Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph in November 2002, sponsored by Novartis Animal Health Canada and run by Lifelearn.

References

- 1.Woolf CJ, Chong MS. Preemptive analgesia — treating postoperative pain by preventing the establishment of central sensitization. Anesth Analg. 1993;77:362–379. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199377020-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basbaum AI, Jessel TM. The perception of pain. In: Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, Jessel TM, eds. Principles of Neural Science. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000:472–491.

- 3.Lamont LA, Tranquilli WJ, Grimm KA. Physiology of pain. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2000;30:703–728. doi: 10.1016/s0195-5616(08)70003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kidd BL, Urban LA. Mechanisms of inflammatory pain. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:3–11. doi: 10.1093/bja/87.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dray A. Pharmacology of peripheral afferent nerve terminals. In: Yaksh TL, Lynch C, Zapol WM, et al, eds. Anesthesia: Biologic Foundations. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1997:543–556.

- 6.Muir WW, III, Woolf CJ. Mechanisms of pain and their therapeutic implications. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2001;219:1346–1356. doi: 10.2460/javma.2001.219.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melzack R, Wall PD. Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science. 1965;150:971–979. doi: 10.1126/science.150.3699.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilcox GL, Seybold V. Pharmacology of spinal afferent processing. In: Yaksh TL, Lynch C, Zapol WM, et al, eds. Anesthesia: Biologic Foundations. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1997:557–576.

- 9.Stamford JA. Descending control of pain. Br J Anaesth. 1995;75:217–227. doi: 10.1093/bja/75.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woolf CJ. Windup and central sensitization are not equivalent. Pain. 1996;66:105–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammond DL, Grahm BA. Gabaergic drugs and the clinical management of pain. In: Yaksh TL, Lynch C, Zapol WM, et al, eds. Anesthesia: Biologic Foundations. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1997:969–975.

- 12.Lemke KA, Dawson SD. Local and regional anesthesia. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2000;30:839–857. doi: 10.1016/s0195-5616(08)70010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torske AE, Dyson DH. Epidural analgesia and anesthesia. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2000;30:859–874. doi: 10.1016/s0195-5616(08)70011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katz J, Kavanagh BP, Sandler AN, et al. Preemptive analgesia. Clinical evidence of neuroplasticity contributing to postoperative pain. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:439–446. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199209000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kissin I. Preemptive analgesia. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:1138–1143. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200010000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moiniche S, Kehlet H, Dahl JB. A qualitative and quantitative systematic review of preemptive analgesia for postoperative pain relief: the role of timing of analgesia. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:725–741. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200203000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kehlet H, Dahl JB. The value of “multimodal” or “balanced analgesia” in postoperative pain treatment. Anesth Analg. 1993;77:1048–1056. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199311000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kehlet H. Multimodal approach to control postoperative pathophysiology and rehabilitation. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78:606–617. doi: 10.1093/bja/78.5.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome. Am J Surg. 2002;183:630–641. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)00866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woolf CJ, Max MB. Mechanism-based pain diagnosis: issues for analgesic drug development. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:241–249. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200107000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]