Abstract

A Thoroughbred mare was presented for stallion-like behavior. Reproductive and ultrasonographic evaluation, testosterone assays, and karyotyping confirmed a diagnosis of androgen insensitivity syndrome (64, XY — testicular feminization). Surgery to remove abdominal testicles was successful in alleviating the behavioral abnormality. This condition is discussed with reference to the current literature.

Abstract

Résumé — Syndrome d’insensibilité aux androgènes chez une jument Thoroughbred (64, XY — féminisation testiculaire). Une jument Thoroughbred a été présentée parce qu’elle avait un comportement d’étalon. Une évaluation reproductrice et échographique, des dosages de testostérone et un caryotypage ont confirmé un diagnostic de syndrome d’insensibilité aux androgènes (64, XY — féminisation testiculaire). Une excision chirurgicale des testicules abdominaux a corrigé le comportement anormal. Cette pathologie est discutée en référant à la littérature actuelle.

(Traduit par Docteur André Blouin)

A 14-year-old, Thoroughbred show hunter mare was referred to Edmonton Equine Veterinary Services for the evaluation of stallion-like behavior. The mare was reported to exhibit the Flehman response and vocalize when in the presence of cycling mares, act aggressively towards other horses, and defecate in a pile in her enclosure. She had been handled like a stallion throughout her performance career and was housed in an individual paddock because of this behavior. During the show season, she was routinely placed on altrenogest (Regumate Solution 0.22%; Intervet Canada, Whitby, Ontario), 0.044 mg/kg bodyweight (BW), PO, q24h, which appeared to decrease her aggression and behavior towards cycling mares. Signs of estrus had never been observed and she had the more classic physical appearance of a stallion, with well-developed muscling of her neck and shoulder regions.

Examination of the reproductive tract revealed normal female external genitalia. On trans-rectal palpation neither a cervix nor a uterus was identifiable. Two firm, smooth oval structures were present within the abdomen where ovaries would normally lie. On manual and speculum examination of the vaginal vault, a shortened vagina with no appreciable cervix was observed. On ultrasonographic evaluation of the abdomen, 2 abdominal testicles were observed in the general proximity of normal female ovaries. Again, neither a uterus nor a cervix was identified.

Serum from the mare was submitted for a mid- afternoon baseline testosterone assay. In the non pregnant female, the normal reference range for testosterone is 20 to 45 pg/mL (Clinical Endocrinology Laboratory, University of California, Davis, California, USA). In this case, the circulating testosterone level was 1154 pg/mL. A human chorionic gonadotropin stimulation test was not carried out, as the results of the baseline testosterone assay were sufficiently elevated to confirm the presence of testicular tissue.

Based on the reproductive, hormonal, and ultrasonographic findings, a tentative diagnosis of 64, XY —testicular feminization was made. Blood was submitted to the Veterinary Genetics Laboratory at the University of California, Davis for karyotyping. A decision to surgically remove the abdominal testicles was made because of the severity of the behavioral condition and the increased frequency for tumor development in abdominally retained testicles.

The mare was fasted overnight and administered sodium penicillin (Penicillin G Sodium; Novopharm Limited, Toronto, Ontario), 106 IU, IV, 1 h prior to surgery. The horse was restrained in stocks and sedated with detomidine hydrochloride (Dormosedan; Pfizer Animal Health, London, Ontario), 0.02 mg/kg BW, IV, and butorphanol tartrate (Torbugesic; Ayerst Laboratories, Montreal, Quebec), 0.02 mg/kg BW, IV. Both left and right flank regions were clipped and prepared for surgery. A sterile field of approximately 20 × 20 cm was isolated as far dorsad as possible in the left and right paralumbar fossae. To achieve adequate analgesia, 30 mL of 2% lidocaine (Lidocaine; Langford, Guelph, Ontario), was infused, SC, and into the muscle tissue. Initially, the mare was administered balanced polyionic fluids, IV, at a rate of 5 mL/kg BW/h.

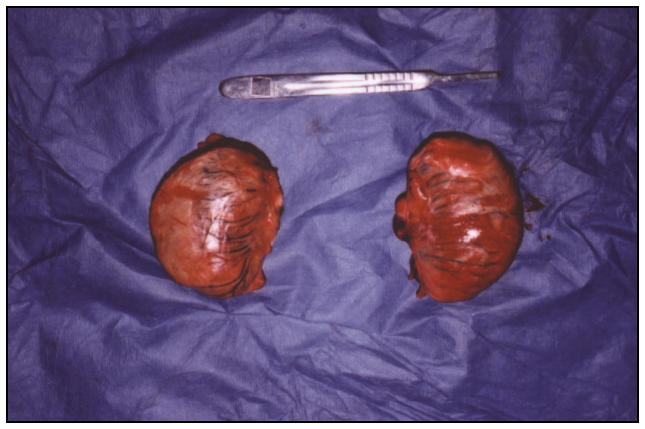

A 10-cm vertical flank incision was made through the skin and subcutis on the right side. Blunt dissection through the external and internal abdominal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles was continued until the peritoneum was visualized. The peritoneum was bluntly punctured with a finger stab and the right testicle was manually located. Five milliliters of 2% lidocaine was infused into the base of the testicle and, by using an ecraseur, the testicle was severed from its attachment. The removed testicle was firm and ovoid, with no appreciable evidence of an associated epididymis (Figure 1). The cord was inspected for hemorrhage and the incision closed routinely. The procedure was repeated on the left side, utilizing the same technique and without incident. Both testicles were submitted for histopathologic examination. The entire procedure lasted approximately 40 min.

Figure 1.

Left and right testes after surgical removal from the abdomen. Note the absence of an associated epididymis.

Postsurgery, the mare received ketoprofen (Anafen; Merial Canada, Baie d’Urfe, Quebec), 2.2 mg/kg BW, IV, q24h, and ceftiofur sodium (Excenel; Pharmacia & Upjohn Animal Health, Orangeville, Ontario), 2.0 mg/kg BW, IM, q24h. The mare was monitored closely over the next 24 h. She appeared to be comfortable and alert, and was eating well. No signs of colic or hemorrhage were apparent. The mare was discharged 72 h later without complications.

Histopathologic examination confirmed the surgically removed tissue was testicular in origin. Sections were composed of seminiferous tubules surrounded by proliferative and numerous Leydig’s interstitial cells. There was a generalized fibrotic reaction with an interstitial fibrosis and very marked interlobular trabecular fibrosis. The seminiferous tubules appeared to have atrophied spermatozoic epithelium, which was primarily replaced by Sertoli cells (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph of section of abdominal testis showing seminiferous tubules, containing atrophied spermatozoic epithelium replaced by Sertoli cells, surrounded by numerous Leydig’s cells. Hematoxylin and eosin.

Ten days postsurgery, the result of a mid-afternoon testosterone assay (< 86.5 pg/mL) was markedly decreased from that of the initial submission. Chromosomal analysis of the mare was reported as 64, XY, confirming our suspected diagnosis. Follow-up communication with the trainer 3 mo postsurgery revealed resolution of the stallion-like behavior, with the horse now being housed with other mares and performing well.

The diploid chromosome number of the domestic horse is 64 (2n = 64). The normal karyotype of the female domestic horse is designated as 64, XX and the male as 64, XY. Chromosomal sex (either XX or XY) is determined at time of fertilization, depending on whether the male gamete that fertilizes the X-bearing female gamete contains an X or a Y chromosome. During normal early embryonic development, the chromosomal sex of the zygote determines the eventual gonadal sex. It is the presence of genetic information borne on the Y chromosome that directs the XY embryo to become a male. The result is conversion of the indifferent gonad to a testis, inhibition of the Mullerian duct development, and stimulation of Wolffian ducts to form vasa deferentia and epididymides (1).

Once testes are formed, they begin to produce testosterone, which results in masculinization of the external genitalia. Masculinization is an active process; it requires the positive or active intervention of androgens for it to take place. If these male hormones are absent, or the tissues do not respond to them (as occurs in androgen insensitivity syndrome [AIS]), then the passive tendency is for the external genitals to differentiate as female. Thus, female physical development is not due to the presence and influence of estrogens, but to the absence or ineffectiveness of androgens (2). The inherent trend is for any fetus to develop female external genitals and general body form in the absence of the masculinizing effects of male hormones.

Female conditions with an XY karyotype have been grouped under the umbrella term “male pseudohermaphroditism.” This is in contrast to the true hermaphrodite, which possesses both testicular and ovarian tissue. The XY female condition can occur as a result of failure of formation of testes (Swyer Syndrome, XY gonadal dysgenesis), underdevelopment of androgen producing cells in testes, enzymatic defects in testosterone biosynthesis, or insensitivity of genital tissues to androgens (AIS) (3).

The 64, XY pseudohermaphrodite condition has been diagnosed in Thoroughbred, Arabian, Appaloosa, Morgan, standardbred and quarter horses, and in the Shetland pony. Such mares have been noted to be of normal or even large size and may have had a successful show and performance career (1). The 2 most commonly diagnosed genetic entities to this condition, in both the human and the horse, are XY gonadal dysgenesis and AIS (testicular feminization). In XY gonadal dysgenesis, there is a failure of formation of active gonads. There are no true ovaries or testes, instead there is the presence of “streak” gonads that lack both germ cells and hormone producing cells. When examined histologically these inactive gonads are comprised primarily of fibrous tissue. A flaccid cervix and uterus are present with normal external genitalia. Serum testosterone levels are minimal, as there is a lack of functional Leydig’s cells (4). This syndrome may be caused by transfer of the SRY (sexual differentiation gene) from the Y to the X chromosome, due to abnormal meiotic exchange (5).

Androgen insensitivity syndrome is the term used by human clinical geneticists and is synonymous with testicular feminization. This syndrome is well documented in the human literature where 2 forms of the condition are reported: complete AIS, where the tissues are completely insensitive to androgens, and partial AIS, where there are varying degrees of sensitivity (2). Androgen insensitivity syndrome is not a disorder of the sex chromosomes, because the sex chromosomes are those of a normal male, XY. The deficiency lies in the androgen receptor gene on the X chromosome received from the dam. This affects the responsiveness, or sensitivity, of the fetus’s body tissues to androgens. Molecular genetic testing has demonstrated a mutation in the androgen receptor gene. Androgen insensitivity syndrome has been determined to be inherited in both human and horses in an X-linked recessive manner (6,7).

In AIS, there may be a spectrum of clinical entities dependent on whether the tissues are completely or partially insensitive to androgens. Most commonly the external genitalia are female with the cervix and uterus lacking. Testes in the inguinal canal, labia, or abdomen are present, as is evidence of normal or increased synthesis of testosterone. In cases of partial resistance to androgens, there may be both male and female physical characteristics, and masculine behavior may be observed (1,2,7).

This report serves to clarify the genetic entities that may result in the XY female horse. This case should also serve to remind clinicians that chromosomal abnormalities may manifest as behavioral or infertility concerns; thus it stresses the need for thorough patient evaluation prior to recommending treatment. Karyotyping should be recommended as a diagnostic aid in infertile mares and mares mended with atypical anatomy. CVJ

References

- 1.Bowling AT, Hughes JP. Cytogenetic abnormalities. In: McKinnon AO, Voss JL, eds. Equine Reproduction. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1993:258–261.

- 2.Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome Support Group Website. What is AIS? http://www.medhelp.org/www/ais/21_OVERVIEW.HTM Last accessed Nov 11, 2003.

- 3.AIS Support Group Australia Website. Diagnosis and Related Conditions. http://home.vicnet.net.au/~aissg/Diagnosis.htm Last accessed January 16, 2004.

- 4.Power MM. XY sex reversal in a mare. Equine Vet J. 1986;18:233–236. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1986.tb03609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bungo M, Klulowska J, Stota E, Tischner M, Switonski M. A sporadic case of the sex-reversed mare (64, XY; SRY-negative): molecular and cytogenetic studies of the Y chromosome. Theriogenology. 2003;59:1597–1603. doi: 10.1016/s0093-691x(02)01197-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buergelt CD. Pathology of the Reproductive System. http://vetmed.ufl.edu/path/teach/vem5162/reproductive/lec1.htm Last accessed Nov 11, 2003.

- 7.Jones WE. Sex reversal syndrome. Equine Vet Data 1983;4–23: 353–359.