Abstract

Genera of Phytopathogenic Fungi (GOPHY) is introduced as a new series of publications in order to provide a stable platform for the taxonomy of phytopathogenic fungi. This first paper focuses on 21 genera of phytopathogenic fungi: Bipolaris, Boeremia, Calonectria, Ceratocystis, Cladosporium, Colletotrichum, Coniella, Curvularia, Monilinia, Neofabraea, Neofusicoccum, Pilidium, Pleiochaeta, Plenodomus, Protostegia, Pseudopyricularia, Puccinia, Saccharata, Thyrostroma, Venturia and Wilsonomyces. For each genus, a morphological description and information about its pathology, distribution, hosts and disease symptoms are provided. In addition, this information is linked to primary and secondary DNA barcodes of the presently accepted species, and relevant literature. Moreover, several novelties are introduced, i.e. new genera, species and combinations, and neo-, lecto- and epitypes designated to provide a stable taxonomy. This first paper includes one new genus, 26 new species, ten new combinations, and four typifications of older names.

Key words: DNA barcodes, Fungal systematics, Phytopathogenic fungi, Plant pathology, Taxonomy, Typifications

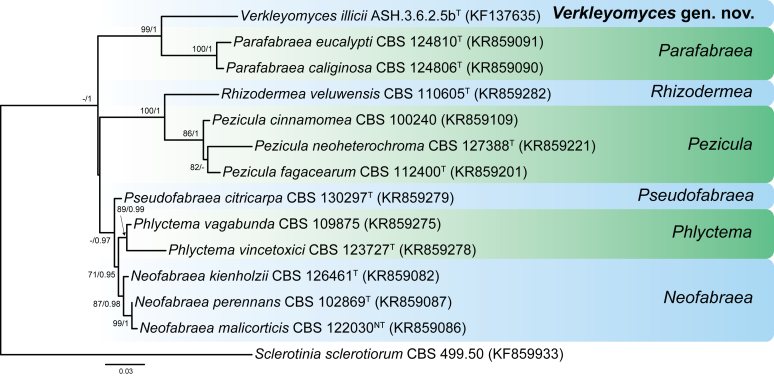

Taxonomic novelties: New genus: Verkleyomyces Y. Marín & Crous

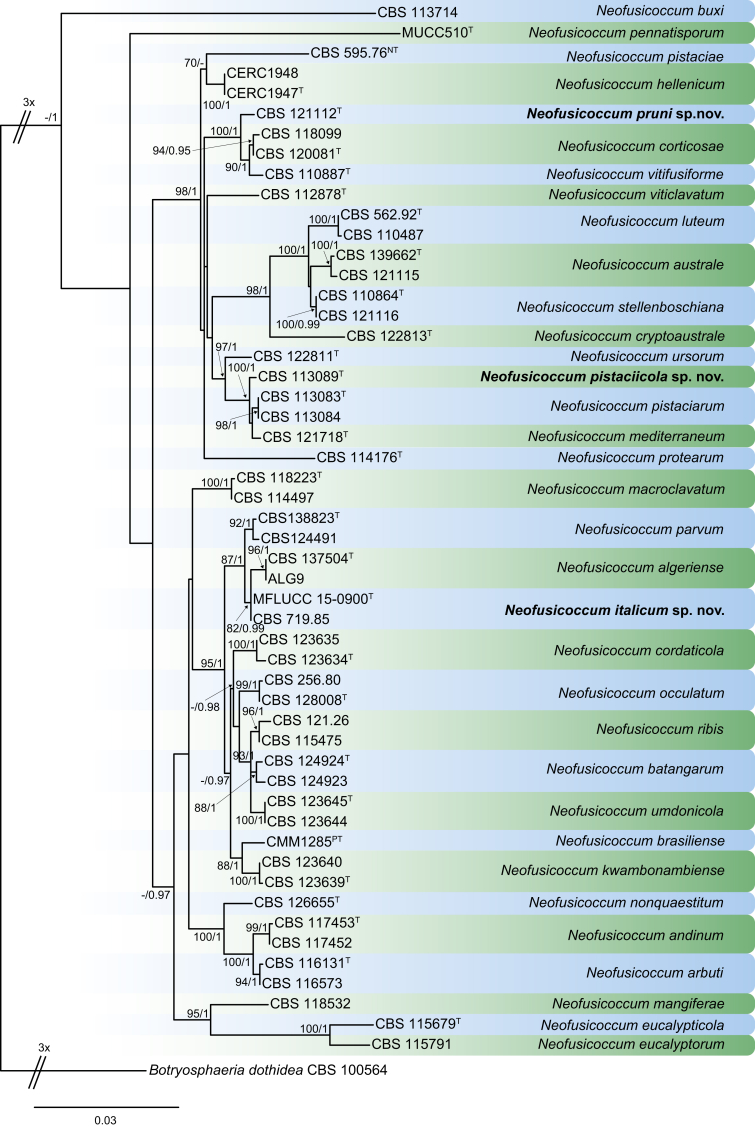

New species: Bipolaris saccharicola Y. Marín & Crous; Bi. variabilis Y. Marín, Y.P. Tan & Crous; Boeremia trachelospermi Q. Chen & L. Cai; Calonectria ecuadorensis L. Lombard & Crous; Ca. longiramosa L. Lombard & Crous; Ca. nemoralis L. Lombard & Crous; Ca. octoramosa L. Lombard & Crous; Ca. parvispora L. Lombard & Crous; Ca. tucuruiensis L. Lombard & Crous; Cladosporium chasmanthicola Bensch, U. Braun & Crous; Cl. kenpeggii Bensch, U. Braun & Crous; Cl. welwitschiicola Bensch, U. Braun & Crous; Colletotrichum sydowii Damm; Curvularia pisi Y. Marín & Crous; Cu. soli Y. Marín & Crous; Neofusicoccum italicum Dissanayake & K.D. Hyde; Nm. pistaciicola Crous; Nm. pruni Crous; Pilidium septatum Giraldo & Crous; Pleiochaeta carotae Hern.-Rest., van der Linde & Crous; Plenodomus deqinensis Q. Chen & L. Cai; Protostegia eucleicola Crous; Saccharata leucospermi Crous; S. protearum Crous; Thyrostroma franseriae Crous; Venturia phaeosepta Y. Zhang ter & J.Q. Zhang

New combinations: Coniella hibisci (B. Sutton) Crous, Monilinia mumeicola (Y. Harada et al.) Sandoval-Denis & Crous, M. yunnanensis (M.J. Hu & C.X. Luo) Sandoval-Denis & Crous, Pseudopyricularia bothriochloae (Crous & Cheew.) Y. Marín & Crous, Puccinia dianellae (Dietel) McTaggart & R.G. Shivas, Pu. geitonoplesii (McAlpine) McTaggart & R.G. Shivas, Pu. merrilliana (Syd. & P. Syd.) McTaggart & R.G. Shivas, Pu. rhagodiae (Cooke & Massee) McTaggart & R.G. Shivas, Venturia martianoffiana (Thüm.) Y. Zhang ter & J.Q. Zhang, Verkleyomyces illicii (X. Sun et al.) Y. Marín & Crous

Typification: Epitypification: Ceratophorum setosum Kirchn., Coniella musaiaensis var. hibisci B. Sutton, Helminthosporium carpophilum Lév.

Lectotypification: Ceratophorum setosum Kirchn

Introduction

Since the advent of molecular DNA techniques, many species of phytopathogenic fungi have been shown to represent species complexes or to be included in genera that are poly- or paraphyletic (Crous et al. 2015b). Resolving these generic and species concepts is thus of the utmost importance for plant health and global trade in food and fibre (Crous et al., 2015b, Crous et al., 2016a). The present project focused on genera of fungi that have members causing plant diseases (phytopathogenic), links to a larger initiative called the “The Genera of Fungi project” based on Clements & Shear (1931) (www.GeneraOfFungi.org, Crous et al., 2014a, Crous et al., 2015a, Giraldo et al., 2017), which aims to revise the generic names of all currently accepted fungi (Kirk et al. 2013).

Of the approximately 18 000 fungal genera that have thus far been described, only around 8 000 are in current use. However, the majority of these were described before the DNA era. To validate the application of these names, their type species need to be recollected and designated as epi- or neotypes with a MycoBank Typification (MBT) number to ensure traceability of the nomenclatural act (Robert et al. 2013). Furthermore, to move to a single nomenclature for fungi (Wingfield et al., 2012, Crous et al., 2015b), their sexual–asexual links also need to be confirmed.

The present initiative forms part of the activities of the International Subcommission for the Taxonomy of Phytopathogenic Fungi [Pedro Crous and Amy Rossman (co-chairs), of the International Committee for the Taxonomy of Fungi (www.fungaltaxonomy.org/)].

The aims of this project are to:

-

1.

Establish a new website, www.plantpathogen.org, to host a database that will link metadata to other databases such as MycoBank, Index Fungorum, FacesofFungi, U.S. National Fungus Collections Databases, etc., and associated DNA barcodes (ITS, LSU and other loci as needed) to GenBank (Schoch et al. 2014).

-

2.

Source type specimens and cultures of the type species of genera from fungaria and Biological Resource Centres (BRCs), and generate the required metadata as explained below.

-

3.

Recollect fresh material of the type species if not already available, and as far as possible derive DNA barcodes and cultures from this material.

-

4.

Designate type species, and type specimens of those species, for those genera where this has not been indicated in the original publications.

-

5.

Fix the application of the type species of generic names by means of lecto-, neo-, or epitypification as appropriate, and at the same time deposit cultures in at least two Microbial Biological Resource Centres (M-BRCs) from which they would be widely available to the international research community.

-

6.

Publish modern generic descriptions, and provide DNA barcodes for all accepted species, with reference to appropriate literature.

Authors with new submissions should ensure that all new species and typification events are registered in MycoBank (MB and MBT numbers), respectively. It is recommended that the following issues are addressed in each genus:

-

1.

Modern generic description, and phylogenetic placement of the type species of the genus.

-

2.

Higher order phylogeny.

-

3.

New nomenclature merging asexual and sexual generic names (see Rossman et al., 2013, Johnston et al., 2014).

-

4.

Description of novel taxa, with a reference collection (e.g. fungarium), and MycoBank and GenBank sequence accession numbers.

-

5.

Name changes that result from the new phylogenetic placement.

-

6.

Notes discussing the relevance and implications of the phylogeny, and importance of the genus.

Authored generic contributions will be combined into scientific papers to be published online in Studies in Mycology, and also placed in a database displayed on www.plantpathogen.org. Preference will be given to genera that include novel DNA data and/or novel species or typifications. Authors that wish to contribute to future issues of this project are encouraged to first contact Pedro Crous (p.crous@westerdijkinstitute.nl) before final submission, to ensure there is no potential overlap with activities arising from other research groups. The genera chosen in the first paper were randomly selected, based on the fact that their phylogenetic position was resolved, DNA data were available for those species known from culture, and novel species or typifications were available for inclusion.

Material and methods

Isolates and morphological analysis

Descriptions of the new taxa and typifications are based on cultures obtained from the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, Utrecht, the Netherlands (CBS), the working collection of P.W. Crous (CPC), housed at the Westerdijk Institute, Herbarium Mycologicum Academiae Sinicae (HMAS), BIOTEC Culture Collection (BCC), the Queensland Plant Pathology Herbarium (BRIP), the Chinese General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (CGMCC), the Mae Fah Luang University Culture Collection (MFLUCC), and the Victorian Plant Pathogen Herbarium (VPRI). For fresh collections, we followed the procedures previously described in Crous et al. (1991). Colonies were transferred to different media, i.e. carnation leaf agar (CLA), cornmeal agar (CMA), 2 % malt extract agar (MEA), 2 % potato-dextrose agar (PDA), synthetic nutrient-poor agar (SNA), oatmeal agar (OA), water agar (WA) (Crous et al. 2009c), autoclaved pine needles on 2 % tap water agar (PNA) (Smith et al. 1996), and incubated at different conditions depending on the taxon to induce sporulation (requirements of media and conditions of incubations specified in each genus). Reference strains and specimens are maintained at the BCC, CBS, CGMCC, HMAS and MFLUCC.

Vegetative and reproductive structures were mounted in clear lactic acid, Shear's mounting fluid and lactophenol cotton blue, either directly from specimens or from colonies sporulating on CLA, MEA, OA, PDA, PNA, or SNA. Sections of conidiomata were made by hand for examination purposes. For cultural characterisation, isolates were grown and incubated on different culture media and temperatures as stipulated for each genus. Colour notations were rated according to the colour charts of Rayner (1970). For some taxa, NaOH pot test was carried out on MEA cultures to detect the production of metabolite E (Boerema et al. 2004). Taxonomic novelties were deposited in MycoBank (www.MycoBank.org; Crous et al. 2004b).

DNA isolation, amplification and analyses

Fungal DNA was extracted and purified directly from the colonies or host material according to the Wizard® Genomic DNA purification kit protocol (Promega, Madison, USA). Primers and protocols for the amplification and sequencing of gene loci can be found in the bibliography related to the phylogeny presented for each genus. Phylogenetic analyses consisted of Maximum-Likelihood (ML), Bayesian Inference (BI), and Maximum Parsimony (MP). The ML was carried out using methods described by Hernández-Restrepo et al. (2016), and the MP using those described by Crous et al. (2006b). The BI was inferred as described by Hernández-Restrepo et al. (2016), or on the CIPRES portal (www.phylo.org) using MrBayes on XSEDE v. 3.2.6. Sequence data generated in this study were deposited in GenBank and ENA databases, and the alignments and trees in TreeBASE (http://www.treebase.org).

Results

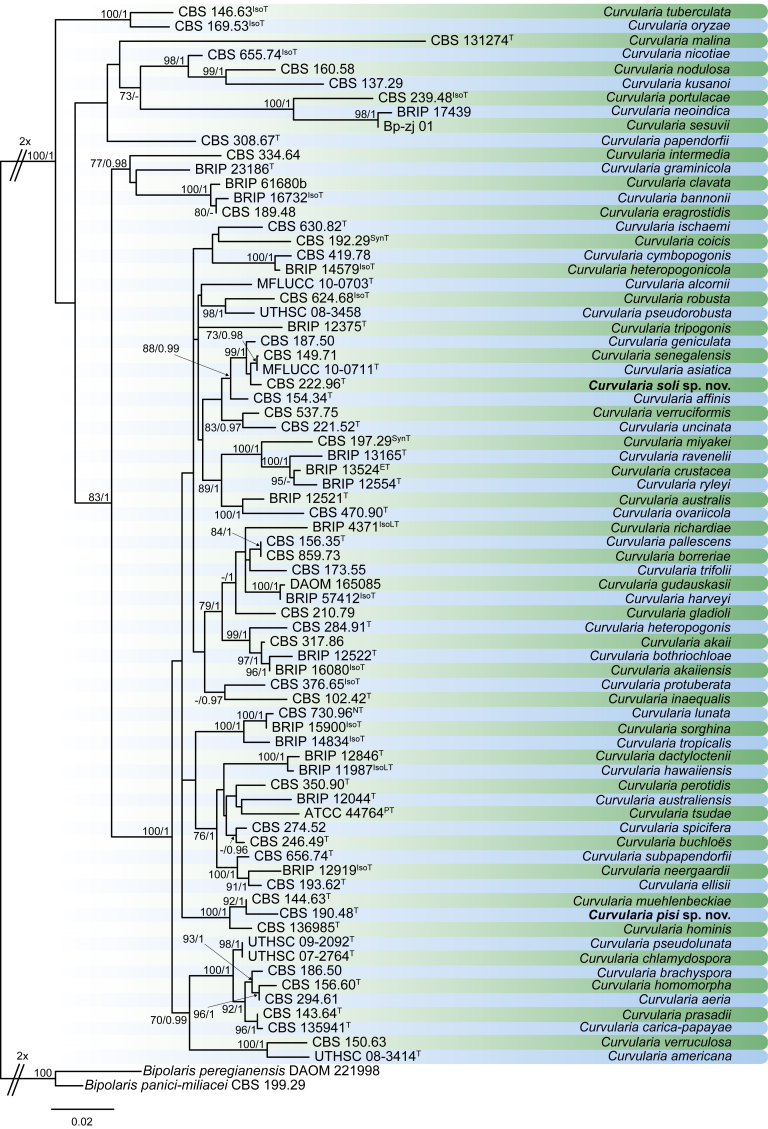

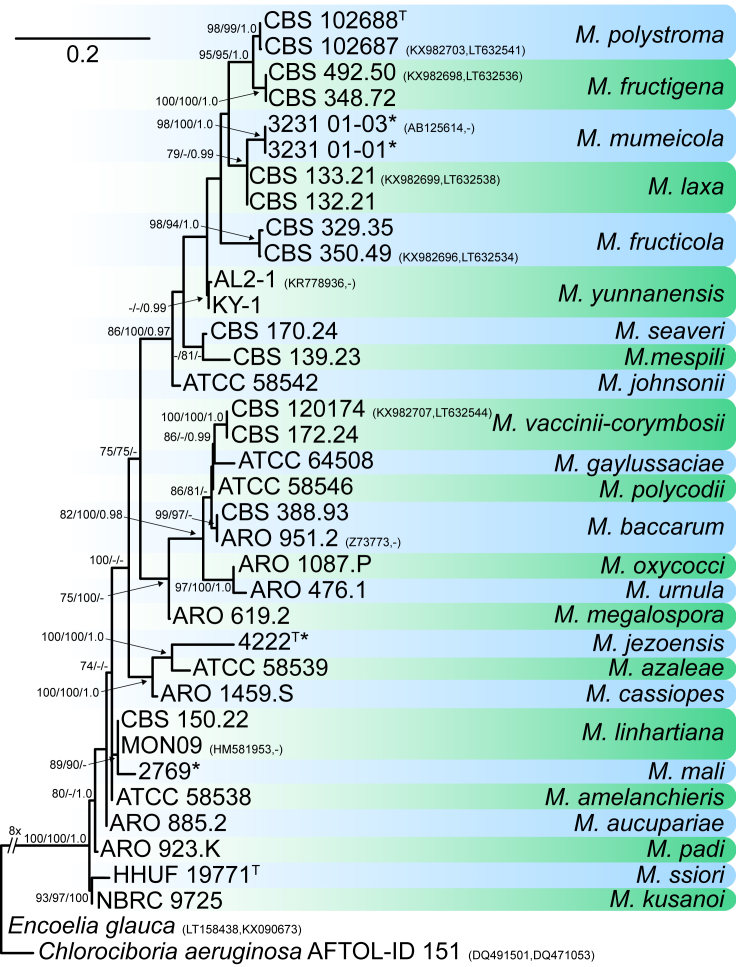

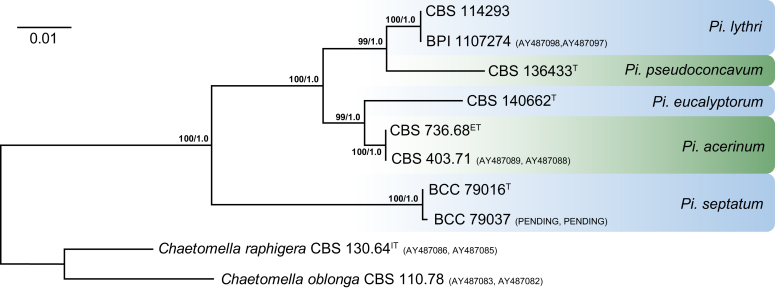

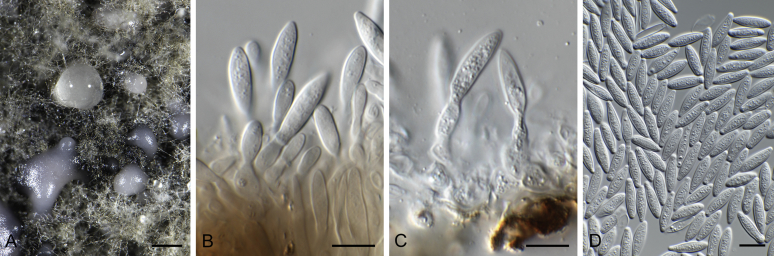

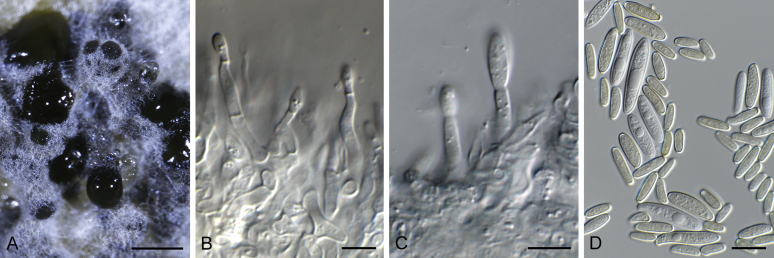

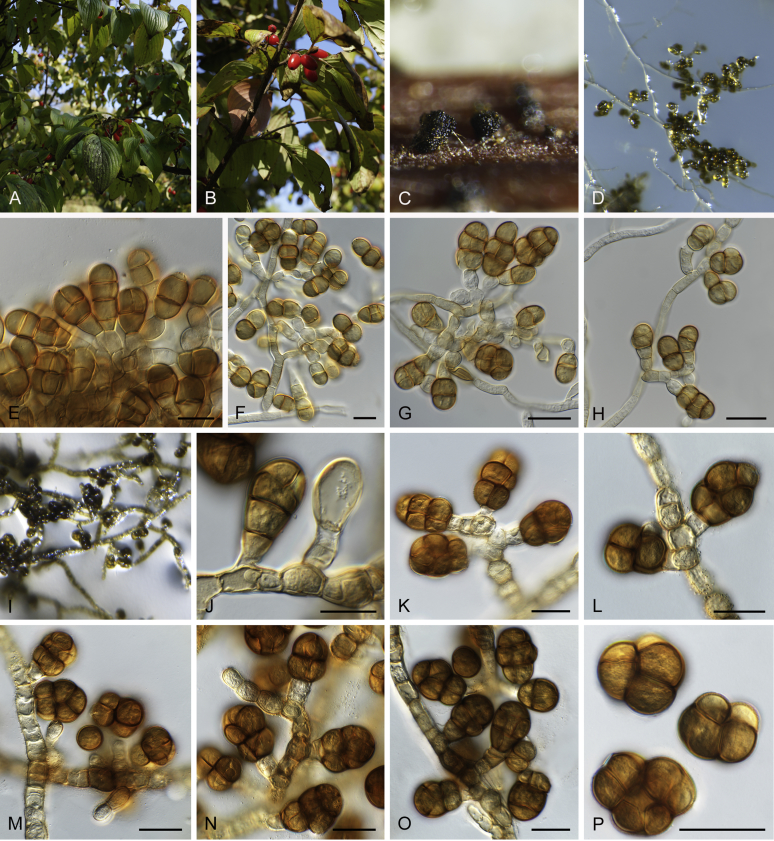

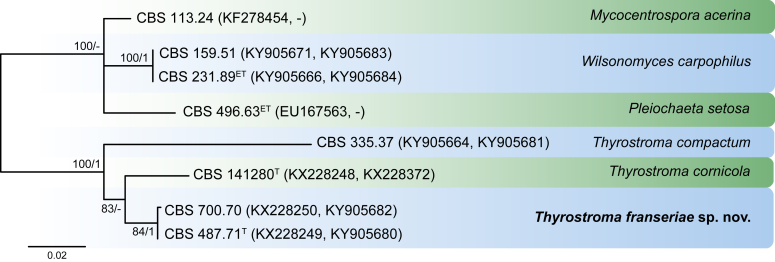

Bipolaris Shoemaker, Canad. J. Bot. 37: 882. 1959. Fig. 1.

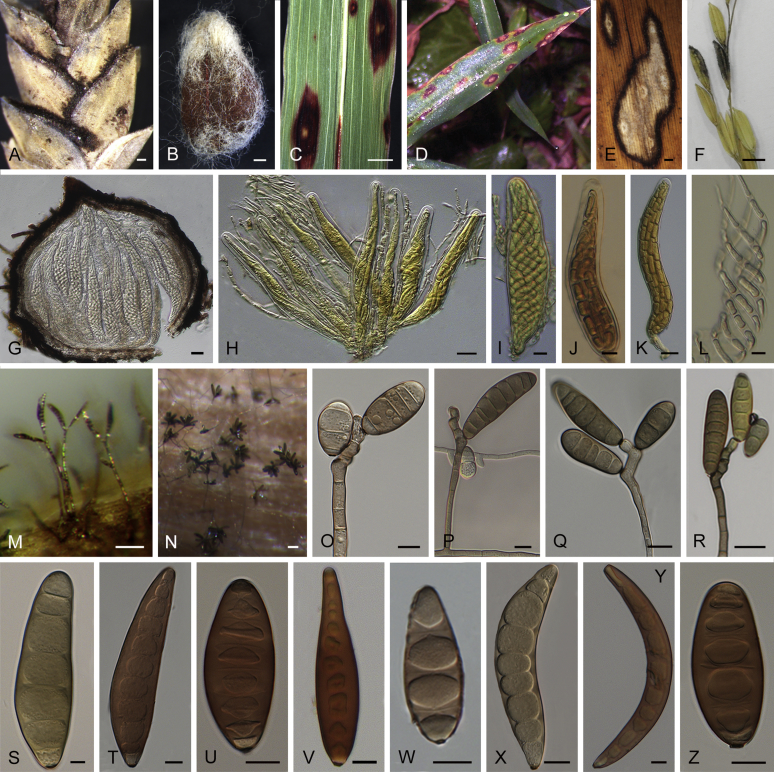

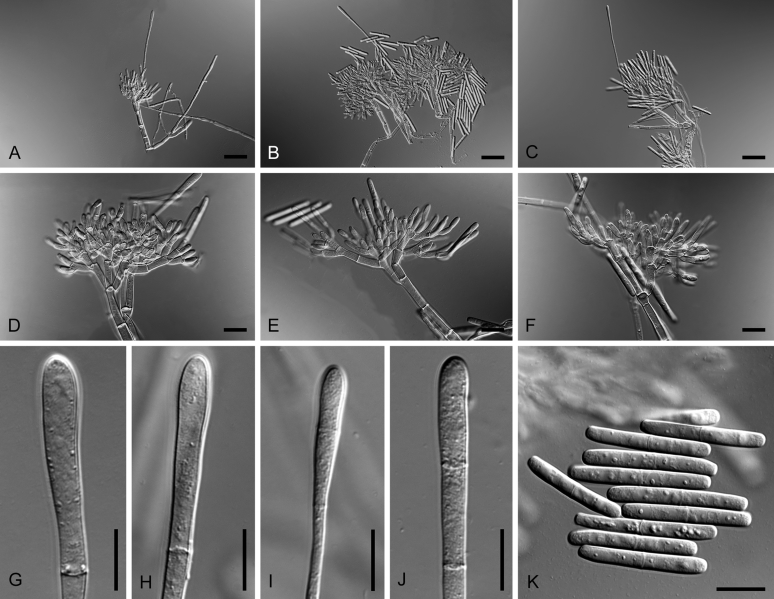

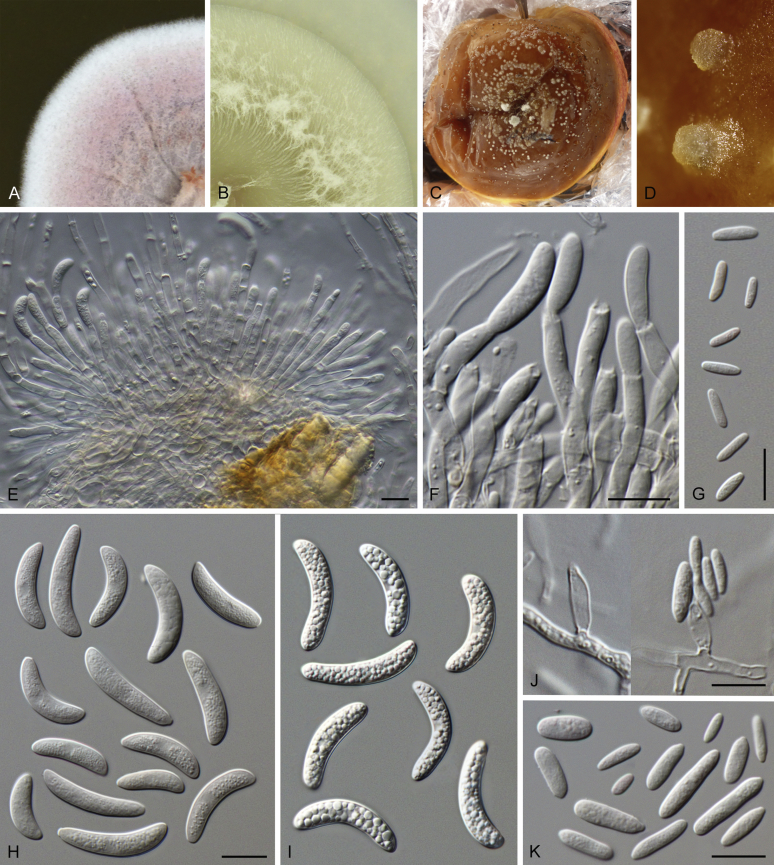

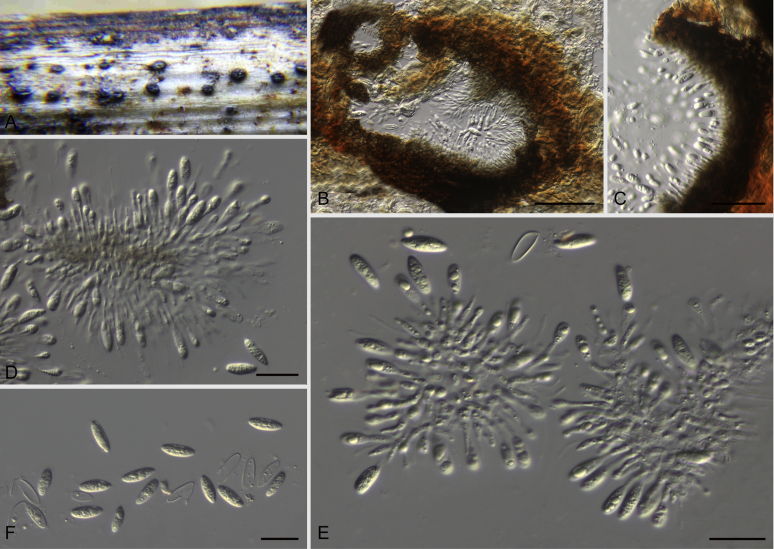

Fig. 1.

Bipolaris spp. A–F. Disease symptoms. A. Symptoms caused by Bipolaris eragrostiellae (ex-type IMI 155931). B. Symptoms caused by Bipolaris gossypina (IMI 123377). C. Symptoms caused by Bipolaris halepensis (ex-type BPI 1103129). D. Symptoms caused by Bipolaris microstegii. E. Symptoms caused by Bipolaris musae-sapientium (ex-type K (M) 181466). F. Symptoms caused by Bipolaris oryzae (ex-neotype MFLUCC 10-0715). G–L. Sexual morphs. G. Ascoma of Bipolaris luttrellii (IMI 345516). H–K. Asci. H.Bipolaris chloridis (ex-type IMI 213865). I.Bipolaris luttrellii (IMI 345516). J.Bipolaris maydis (CBS 241.92). K.Bipolaris microlaenae (IMI 338218). L. Ascospores of Bipolaris maydis (CBS 241.92). M–Z. Asexual morphs. M–R. Conidiophores and conidia. M.Bipolaris setariae (BPI 880305B). N.Bipolaris zeae (ex-type IMI 202085). O.Bipolaris bicolor (CBS 690.96). P.Bipolaris heveae (CBS 241.92). Q.Bipolaris sorokiniana (ex-type CBS 110.14). R.Bipolaris zeicola (ex-type BPI 626668). S–Z. Conidia. S.Bipolaris cookei (ex-type BPI 428852). T.Bipolaris costina (ex-type IMI 256417). U.Bipolaris crotonis (ex-type IMI 223682). V.Bipolaris gossypina (IMI 123377). W.Bipolaris obclavata (ex-type IMI 331725). X.Bipolaris oryzae (ex-neotype MFLUCC 10-0715). Y.Bipolaris salviniae (DAR 35056). Z.Bipolaris sorokiniana (ex-type CBS 110.14). Scale bars: A, N = 100 μm; B, E, F = 500 μm; C = 1 cm; G, H = 20 μm; I–L, O–Z = 10 μm; M = 50 μm. All pictures except for D taken from Manamgoda et al. (2014).

Synonym: Cochliobolus Drechsler, Phytopathology 24: 973. 1934.

Classification: Dothideomycetes, Pleosporomycetidae, Pleosporales, Pleosporaceae.

Type species: Bipolaris maydis (Y. Nisik. & C. Miyake) Shoemaker. Neotype and ex-neotype culture: ATCC 48332, CBS 137271.

DNA barcodes (genus): LSU, ITS.

DNA barcodes (species): ITS, gapdh, tef1. Table 1. Fig. 2.

Table 1.

DNA barcodes of accepted Bipolaris spp.

AR, FIP: Isolates housed in Systematic Mycology and Microbiology Laboratory, United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Beltsville, Maryland, USA; Bi: Isolates housed in the Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agricultural Sciences and Engineering, University College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of Tehran, Karaj, Iran (TUPP); ATCC: American Type Culture Collection, Virginia, USA; BRIP: Queensland Plant Pathology Herbarium, Brisbane, Australia; CBS: Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, Utrecht, the Netherlands; ICMP: International Collection of Micro-organisms from Plants, Landcare Research, Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand; MFLUCC: Mae Fah Luang University Culture Collection, Chiang Ria, Thailand. T, ET, IsoT, IsoLT, IsoPT, LT and NT indicate ex-type, ex-epitype, ex-isotype, ex-isolectotype, ex-isoparatype, ex-lectotype and ex-neotype strains, respectively.

ITS: internal transcribed spacers and intervening 5.8S nrDNA; gapdh: partial glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene; tef1: partial translation elongation factor 1-alpha gene.

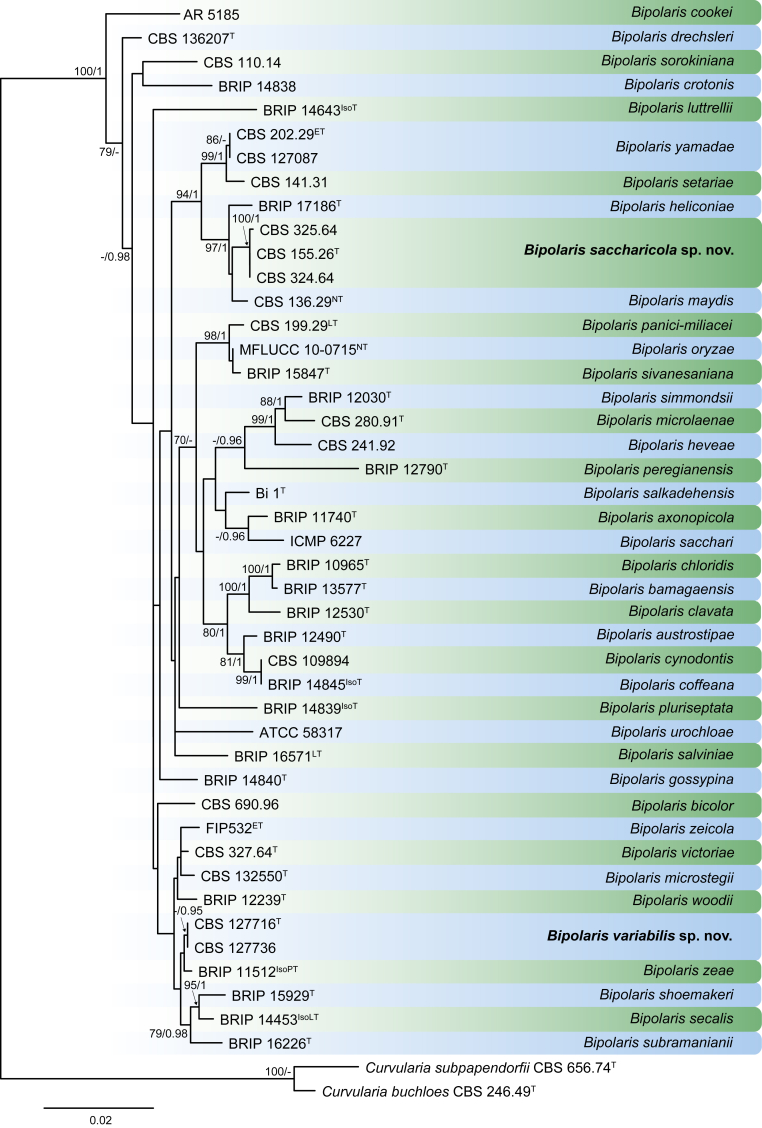

Fig. 2.

RAxML phylogram obtained from the combined ITS (478 bp), gapdh (472 bp) and tef1 (892 bp) sequences of all the accepted species of Bipolaris. The tree was rooted to Curvularia buchloës CBS 246.49 and Curvularia subpapendorfii CBS 656.74. The novel species described in this study are shown in bold. RAxML bootstrap support (BS) values above 70 % and Bayesian posterior probability scores ≥ 0.95 are shown at the nodes. GenBank accession numbers are indicated in Table 1. T, ET, IsoT, IsoLT, IsoPT, LT and NT indicate ex-type, ex-epitype, ex-isotype, ex-isolectotype, ex-isoparatype, ex-lectotype and ex-neotype strains, respectively. TreeBASE: S20877.

Ascomata pseudothecial, mostly globose to ellipsoidal, sometimes flask-shaped or flattened on hard substrata, brown or black, immersed, erumpent, partially embedded or superficial, free, smooth or covered with vegetative hyphae; ostiole central, papillate or with a sub-conical, conical, paraboloid or cylindrical neck; ascomatal wall comprising pseudoparenchymatous cells of equal thickness or slightly thickened at apex of the ascoma. Hamathecium comprising septate, filiform, branched pseudoparaphyses. Asci bitunicate, clavate, cylindrical-clavate or broadly fusoid, straight or slightly curved, thin-walled, fissitunicate, often becoming more or less distended prior to dehiscence, short pedicellate, rounded at apex. Ascospores multiseriate, filiform or flagelliform, hyaline or sometimes pale yellow or pale brown at maturity, septate, helically coiled within ascus, ascospore coiling moderate to strongly, often with a mucilaginous sheath. Conidiophores single, sometimes arranged in small groups, straight to flexuous or geniculate, pale to dark brown, branched, thick-walled, septate. Conidiogenous nodes smooth to slightly verruculose. Conidia canoe-shaped, fusoid or obclavate, mostly curved, hyaline, pale or dark brown, reddish brown or pale to deep olivaceous, thick-walled, smooth-walled, 3–14-distoseptate, germinating by production of one or two germination tubes by polar cells; hila often slightly protruding or truncate, sometimes inconspicuous; septum ontogeny first septum median to sub-median, second septum delimits basal cell and third delimits distal cell (adapted from Manamgoda et al. 2014).

Culture characteristics: Colonies on PDA white or pale grey when young, brown or dark grey when mature, fluffy, cottony, raised or convex with papillate surface, margin lobate, undulate, entire or sometimes rhizoid.

Optimal media and cultivation conditions: Sterilised Zea mays leaves placed on 1.5 % WA or slide cultures of PDA under near-ultraviolet light (12 h light, 12 h dark) at 25 °C to induce sporulation of the asexual morph, while for the sexual morph Sach's agar with sterilised rice or wheat straw at 25 °C is used.

Distribution: Worldwide.

Hosts: Mainly pathogens of grasses, but some also on non-grass hosts, causing devastating diseases on cereal crops in the Poaceae, including rice, maize, wheat and sorghum and on various other host plants. Moreover, this genus can occur on at least 60 other genera in Anacardiaceae, Araceae, Euphorbiaceae, Fabaceae, Malvaceae, Rutaceae and Zingiberaceae as either saprobes or pathogens.

Disease symptoms: Leaf spots, leaf blight, melting out, root rot, and foot rot, among others.

Notes: Species delimitation based on morphology alone is limited since many species have overlapping characters. Moreover, the morphology of the sexual morph is of limited value due to difficulties to induce this morph in culture, or find it in nature. The genus is morphologically similar to Curvularia, and distinguishing these genera can be problematic. Both genera contain species with straight or curved conidia, but in Bipolaris the curvature is continuous throughout the length of the conidium, while the conidia of Curvularia have intermediate cells inordinately enlarged which contributes to their curvature. Moreover, conidia in Bipolaris are usually longer than in Curvularia. Another morphological difference is the presence of stromata in some species of Curvularia, a feature not observed in species of Bipolaris. In order to properly delineate both genera, phylogenetic studies using ITS, gapdh and tef1 sequences were recently performed (Manamgoda et al., 2014, Manamgoda et al., 2015).

References: Ellis, 1971, Sivanesan, 1987 (morphology and pathogenicity); Manamgoda et al., 2011, Tan et al., 2016 (morphology, phylogeny and pathogenicity); Manamgoda et al. 2014 (morphology, phylogeny, pathogenicity and key of all Bipolaris spp.).

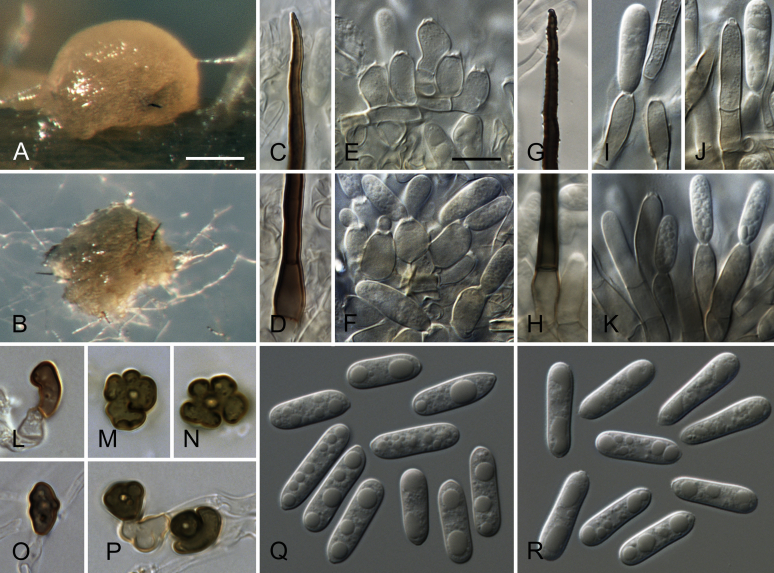

Bipolaris saccharicola Y. Marín & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB820809. Fig. 3.

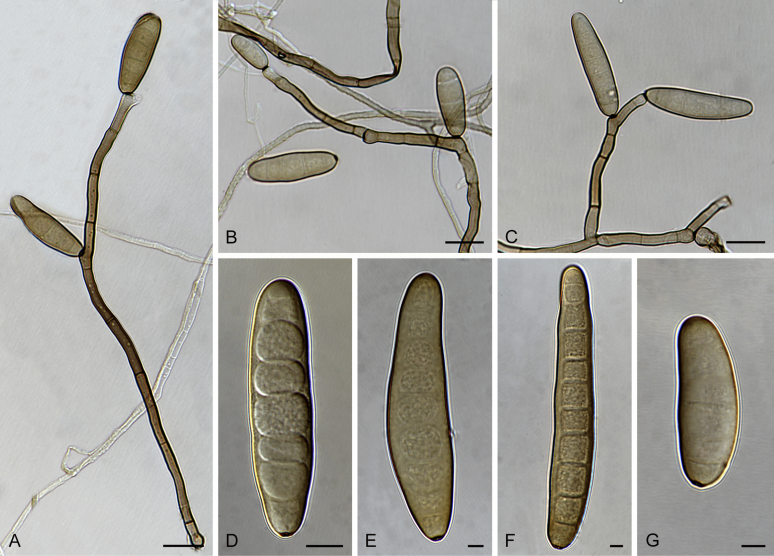

Fig. 3.

Bipolaris saccharicola (ex-type CBS 155.26). A–C. Conidiophores and conidia. D–H. Conidia. Scale bars: A–C = 20 μm; H applies to D–H = 10 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to the host genus it was isolated from, Saccharum.

Hyphae hyaline to pale brown, branched, septate, thin-walled, 2.5–5.5 μm. Conidiophores arising in smalls groups, septate, straight or flexuous, smooth-walled, sometimes branched, cell walls thicker than those of vegetative hyphae, mononematous, semi- to macronematous, pale brown to brown, paler towards apex, rarely swollen at base, up to 900 μm tall. Conidiogenous cells smooth-walled, terminal or intercalary, subhyaline to pale brown or brown, subcylindrical to swollen, 10–27(–47) × 4–8 μm. Conidia verruculose, curved, rarely straight, fusiform, subhyaline to pale brown or brown, (2–)4–9(–11)-distoseptate, (30–)45–120 × 10.5–20(–21.5) μm; hila inconspicuous, brown, slightly protuberant, flat, darkened, slightly thickened, 2–4 μm. Chlamydospores and sexual morph not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies on PDA reaching 41–53 mm diam after 1 wk, moderate aerial mycelium giving a cottony appearance, margin lobate; surface olivaceous grey to olivaceous black; reverse olivaceous black.

Material examined: Unknown country, unknown substratum, 1926, H. Atherton (holotype CBS H-23114, culture ex-type CBS 155.26 = MUCL 9693); Unknown country, from Saccharum officinarum, unknown date, R.R. Nelson, CBS 324.64; CBS 325.64 = DSM 62597 = MUCL 18220 = MUCL 9694 = NRRL 5241.

Notes: This species is closely related to Bi. maydis. However, Bi. saccharicola can easily be distinguished by the absence of a sexual morph, longer conidiophores and verruculose, more prominently curved conidia. Both species can be found on the same host, Saccharum officinarum. Other species of Bipolaris isolated from this host include Bi. cynodontis, Bi. sacchari, Bi. setariae, Bi. stenospila and Bi. yamadae (Manamgoda et al. 2014). Bipolaris saccharicola is morphologically similar to Bi. sacchari, but Bi. saccharicola can be distinguished by its much longer and non-geniculate conidiophores and wider and more septate conidia.

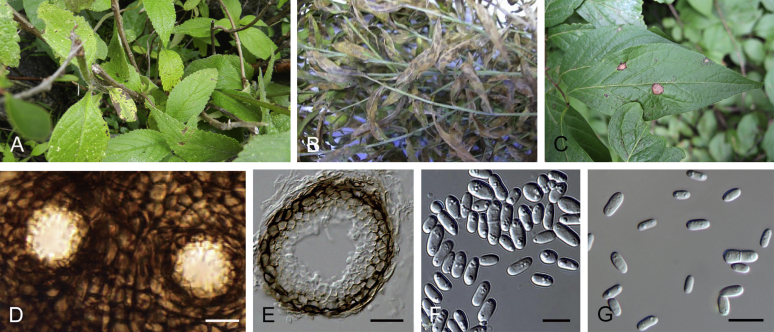

Bipolaris variabilis Y. Marín, Y.P. Tan & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB820810. Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Bipolaris variabilis (ex-type CBS 127716). A–C. Conidiophores and conidia. D–M. Conidia. Scale bars: A = 20 μm; B, C = 15 μm; H applies to D–H, M applies to I–M = 5 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to the highly variable conidial morphology.

Leaf spots brown to reddish, elongated, often confluent and following veins, some with central part brown, 2.5 × 1–2 mm. Hyphae subhyaline to pale brown, branched, septate, thin-walled, 3–6 μm. Conidiophores arising in groups, septate, straight or flexuous, sometimes geniculate at upper part, smooth to verruculose, branched, cells walls thicker than those of vegetative hyphae, mononematous, semi- to macronematous, pale brown to brown, paler towards apex, slightly swollen at base, up to 1 600 μm tall. Conidiogenous cells smooth-walled, terminal or intercalary, proliferating sympodially, subhyaline or pale brown to brown, subcylindrical to swollen, (6.5–)8–26(–35) × 5.5–11 μm. Conidia verruculose, straight or slightly curved, globose, subglobose, ellipsoidal to obclavate, pale brown to brown, apical and basal cells paler than middle cells being subhyaline to pale brown, (1–)3–7(–9)-distoseptate, 13.5–77 × 10–19.5 μm; hila inconspicuous, slightly protuberant, flat, darkened, thickened, 3–6 μm diam. Chlamydospores and sexual morph not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies on PDA reaching 90 mm diam within 1 wk, with sparse to moderate aerial mycelium giving a cottony appearance, margin lobate; surface olivaceous grey to iron-grey; reverse olivaceous black.

Material examined: Argentina, from leaf spots on Pennisetum clandestinum, 28 Jul. 1986, col. M.N. Sisterna, isol. J.L. Alcorn (holotype CBS H-23115, culture ex-type CBS 127716 = BRIP 15349). Brazil, from Pennisetum clandestinum, Apr. 1987, J.J. Muchovej, CBS 127736 = BRIP 15702 = ATCC 62423.

Notes: Bipolaris variabilis can easily be distinguished based on its highly variable conidial size, shape and septation. Hitherto, this species has only been found on Pennisetum clandestinum in South America. Other species of Bipolaris can be found on Pennisetum spp., i.e. Bi. bicolor, Bi. colocasiae, Bi. cynodontis, Bi. maydis, Bi. mediocris, Bi. sacchari, Bi. setariae, Bi. sorokiniana, Bi. stenospila, Bi. urochloae and Bi. zeae; however, only Bi. mediocris is restricted to that host (Manamgoda et al. 2014). Bipolaris mediocris and Bi. variabilis are morphologically similar, but Bi. variabilis produces smaller, verruculose conidia. Moreover, Bi. mediocris is characterised by much shorter conidiophores (up to 150 μm tall), and has only been reported in Africa (Farr & Rossman 2017). Bipolaris variabilis is closely related to Bi. zeae, but the latter is characterised by shorter conidiophores (up to 370 μm tall), and less septate conidia that are less variable in shape than those of Bi. variabilis.

Bipolaris yamadae (Y. Nisik.) Shoemaker, Canad. J. Bot. 37: 884. 1959. Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Bipolaris yamadae (CBS 127087). A–C. Conidiophores and conidia. D–G. Conidia. Scale bars: A–C = 20 μm; D–G = 10 μm.

Basionym: Helminthosporium yamadae Y. Nisik., Rept. Ohara. Inst. Agr. Research 4: 120. 1928.

Synonyms: Drechslera yamadai (Y. Nisik.) Subram. & B.L. Jain, Curr. Sci. 35: 355. 1966.

Helminthosporium euphorbiae Hansf., Proc. Linn. Soc. London 155: 49. 1943.

Bipolaris euphorbiae (Hansf.) J.J. Muchovej & A.O. Carvalho, Mycotaxon 35: 160. 1989.

Drechslera euphorbiae (Hansf.) M.B. Ellis, Dematiaceous Hyphomycetes (Kew): 440. 1971.

Notes: Bipolaris euphorbiae was originally described in Helminthosporium (Hansford 1943), then transferred to Drechslera (Ellis 1971), and finally placed in Bipolaris based on the bipolar germination and hilum structure (Muchovej & Carvalho 1989). In their revision of Bipolaris, Manamgoda et al. (2014) accepted this species in the genus despite the lack of molecular data. In the present study, the neotype strain of Bi. euphorbiae CBS 127087 (=BRIP 16567; see Fig. 5), which was designated by Muchovej & Carvalho (1989), clustered with the ex-epitype strain of Bi. yamadae. Both species are morphologically similar differing only in the size of the structures that are usually overlapping. Based on these data, we propose to reduce Bi. euphorbiae to synonymy under Bi. yamadae. Moreover, we emended the description of Bi. yamadae to include the morphology of its new synonym, as well as the new host and distribution records.

Leaf spots on Panicum sp. ovoid, oblong, pale brown at margin and pale brown at centre, with an irregular concentric zone. Hyphae hyaline, branched, septate, anastomosing, thin-walled, 1.5–4.5 μm. Conidiophores arising singly or in small groups, septate, rarely branched, straight or flexuous, sometimes geniculate at upper part, smooth walled, mononematous, semi- to macronematous, olive-brown to pale brown, sometimes paler towards apex, swollen at base, 40–650 × 3–10.5 μm. Conidiogenous cells smooth-walled, sometimes slightly verruculose, terminal or intercalary, subhyaline to pale brown or dark brown, subcylindrical to slightly swollen, 7–30(–40) × 5.5–9.5 μm. Conidia smooth-walled, straight or curved, ellipsoidal, cylindrical, fusiform or obclavate, sometimes obovoid, with rounded ends, subhyaline to pale brown or olive-brown, (3–)5–7(–11)-distoseptate, 27–100(–120) × 11.5–20 μm; hila 2.5–4.5 μm, non or slightly protuberant, flat, darkened; germination at both ends.

Culture characteristics: Colonies on PDA reaching 30–65 mm diam after 1 wk, cottony, with irregular margins; surface pale olivaceous grey to olivaceous grey; reverse olivaceous black.

Distribution: Brazil, Cuba, China, India, Japan, Sudan, Tanzania, USA (IA, ID, ND, WI).

Hosts: Panicum capillare, Pa. implicatum, Pa. maximum, Pa. miliaceum, Euphorbia sp., Oryza sp., Saccharum sp., Setaria plicata (Farr & Rossman 2017).

Authors: Y. Marin-Felix, P.W. Crous & Y.P. Tan

Boeremia Aveskamp et al., Stud. Mycol. 65: 36. 2010. Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Boeremia spp. A. Symptoms of Boeremia lilacis (LC 8116) on Ocimum sp. B. Symptoms of Boeremia exigua var. rhapontica (ex-type CBS 113651) on Rhaponticum repens. C. Symptoms of Boeremia lilacis (LC 5178) on Lonicera sp. D. Ostiole configuration of Boeremia exigua var. exigua (CBS 431.74). E. Section of young pycnidium of Boeremia exigua var. pseudolilacis (ex-type CBS 101207). F. Conidia of Boeremia exigua var. pseudolilacis (ex-type CBS 101207). G. Conidia of Boeremia exigua var. heteromorpha (ex-neotype CBS 443.94). Scale bars: D–E = 20 μm; F = 5 μm; G = 10 μm. Picture B taken from Berner et al. (2015); D–F from Aveskamp et al. (2010); G from Chen et al. (2015a).

Classification: Dothideomycetes, Pleosporomycetidae, Pleosporales, Didymellaceae.

Type species: Boeremia exigua (Desm.) Aveskamp et al. Representative strain: CBS 431.74.

DNA barcodes (genus): LSU, ITS.

DNA barcodes (species): act, cal, rpb2, tef1, tub2. Table 2. Fig. 7.

Table 2.

DNA barcodes of accepted Boeremia spp.

CBS: Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, Utrecht, the Netherlands; CGMCC: Chinese General Microbiological Culture Collection Center, Beijing, China. T and NT indicate ex-type and ex-neotype strains, respectively.

ITS: internal transcribed spacers and intervening 5.8S nrDNA; act: partial actin gene; cal: partial calmodulin gene; rpb2: partial RNA polymerase II second largest subunit gene; tef1: partial translation elongation factor 1-alpha gene; tub2: partial β-tubulin gene.

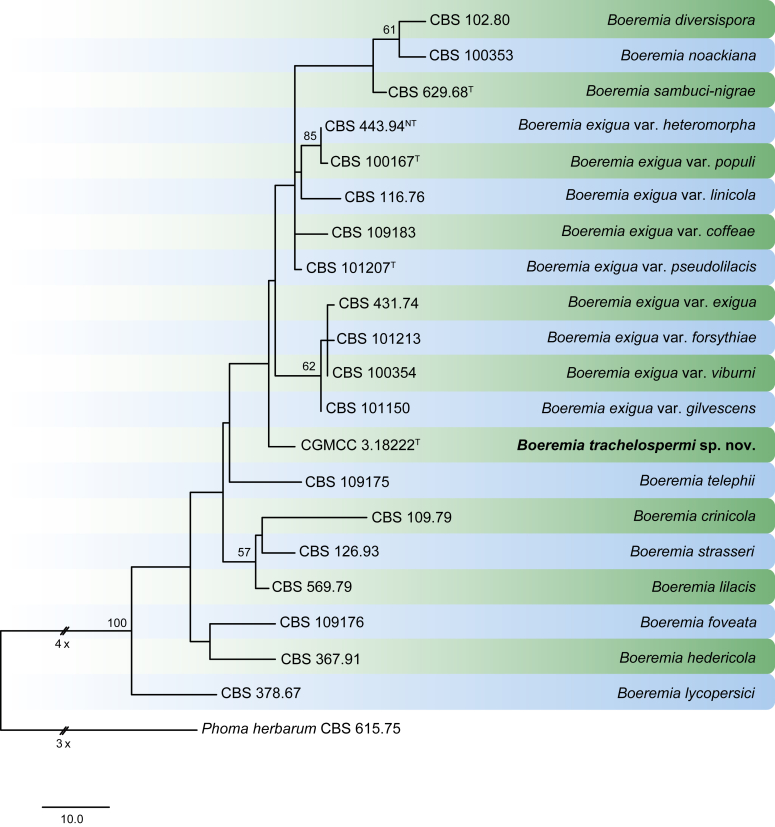

Fig. 7.

Phylogenetic tree generated from a maximum parsimony analysis based on the combined LSU, ITS, tub2 and rpb2 sequences. Values above the branches represent parsimony bootstrap support values (> 50 %). The novel species are shown in bold. The tree is rooted with Phoma herbarum CBS 615.75. GenBank accession numbers are indicated in Table 2. T and NT indicate ex-type and ex-neotype strains, respectively. TreeBASE: S21048.

Ascomata pseudothecial, subglobose. Asci cylindrical or subclavate, 8-spored, biseriate. Ascospores ellipsoidal, 1-septate. Conidiomata pycnidial, variable in shape and size, mostly globose to subglobose, superficial or immersed into agar, solitary or confluent; ostiole non-papillate or papillate, lined internally with hyaline cells when mature; conidiomatal wall pseudoparenchymatous, multi-layered, outer wall brown pigmented. Conidiophores reduced to conidiogenous cells. Conidiogenous cells phialidic, hyaline, smooth, ampulliform to doliiform. Conidia variable in shape, hyaline, smooth- and thin-walled, mainly aseptate, but 1(–2)-septate larger conidia may be found (adapted from Aveskamp et al. 2010).

Culture characteristics: Colonies on OA white to dull green, grey olivaceous to olivaceous or smoke-grey, velvety, floccose to woolly, margin often regular, sometimes lobate and irregular scalloped.

Optimal media and cultivation conditions: OA or PNA at 25 °C under near-ultraviolet light (12 h light, 12 h dark) to promote sporulation.

Distribution: Worldwide.

Hosts: Seed-borne pathogens of Phaseolus vulgaris (Fabaceae) and noxious pathogens of Coffea arabica (Rubiaceae). Species on more than 200 host genera including Amaryllidaceae, Apocynaceae, Araliaceae, Asteraceae, Caprifoliaceae, Chenopodiaceae, Crassulaceae, Fabaceae, Lamiaceae, Linaceae, Oleaceae, Salicaceae, Solanaceae, Ulmaceae, Umbelliferae.

Disease symptoms: Leaf spots, stem lesions, black node, bulb rot, root rot, shoot dieback.

Notes: The genus Boeremia was established by Aveskamp et al. (2010) to accommodate phoma-like species that are morphologically similar and closely related to Ph. exigua. Taxa in this genus are characterised by having ostioles with a hyaline inner layer of cells and producing aseptate and septate conidia (Aveskamp et al. 2010). To date only Bo. lycopersici has been reported to have a sexual morph. Recently, Chen et al. (2015a) and Berner et al. (2015) further examined the phylogenetic relationships of taxa in Boeremia in two combined multilocus analyses, the first one based on LSU, ITS, tub2 and rpb2 sequences, and the second on ITS, act, cal, tef1 and tub2 sequences.

References: Boerema et al. 2004 (morphology and pathogenicity); Aveskamp et al., 2010, Chen et al., 2015a (morphology and phylogeny); Berner et al. 2015 (morphology, pathogenicity and phylogeny).

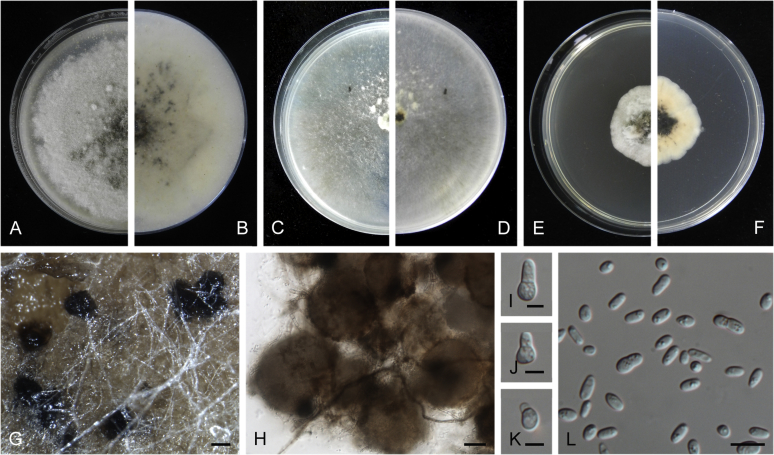

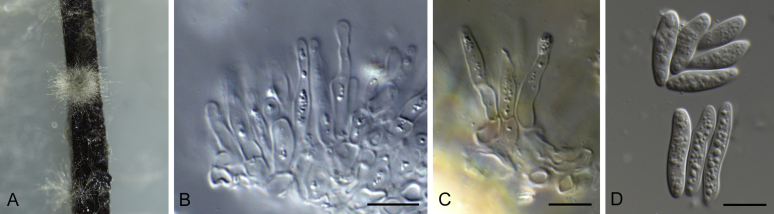

Boeremia trachelospermi Q. Chen & L. Cai, sp. nov. MycoBank MB818819. Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Boeremia trachelospermi (ex-type CGMCC 3.18222). A, B. Colony on OA (front and reverse). C, D. Colony on MEA (front and reverse). E, F. Colony on PDA (front and reverse). G. Pycnidia forming on OA. H. Pycnidia. I–K. Conidiogenous cells. L. Conidia. Scale bars: G = 200 μm; H = 50 μm; I–K = 5 μm; L = 10 μm.

Etymology: Named for the host genus from which the holotype was collected, Trachelospermum.

Conidiomata pycnidial, solitary or aggregated, globose to subglobose, glabrous or with few hyphal outgrowths, superficial, with a short neck, 75–255 × 60–225 μm; ostiole single, papillate or non-papillate; conidiomatal wall pseudoparenchymatous 2–4-layered, 16.5–37 μm thick, composed of isodiametric cells. Conidiophores reduced to conidiogenous cells. Conidiogenous cells phialidic, hyaline, smooth, ampulliform to doliiform, 4.5–12.5 × 4.5–6 μm. Conidia variable in shape, mostly ovoid, ellipsoidal to cylindrical, smooth- and thin-walled, hyaline, mainly aseptate, occasionally 1-septate large conidia, 4.5–9.5 × 2.5–4.5 μm, with 1–8 guttules. Conidial matrix cream-coloured.

Culture characteristics: Colonies on OA, reaching 47–55 mm diam after 1 wk, margin regular, floccose, white, dark grey near centre; reverse white to buff, dark grey near centre. Colonies on MEA 40–60 mm diam after 1 wk, margin regular, woolly, pale olivaceous grey; reverse concolourous. Colonies on PDA, reaching 20–25 mm diam after 1 wk, margin regular, floccose, compact, white to olivaceous; reverse white to buff, olivaceous near centre. NaOH test negative.

Material examined: USA, on seedlings of Trachelospermum jasminoides, 2014, W.J. Duan (holotype HMAS 246706, culture ex-type CGMCC 3.18222 = LC 8105).

Notes: Boeremia trachelospermi represents the first report of a Boeremia species on Trachelospermum (Apocynaceae). Phylogenetically, it forms a distinct lineage separate from Bo. diversispora, the Bo. exigua varieties, Bo. noackiana and Bo. sambuci-nigrae (Fig. 7), and morphologically it often produces longer conidiogenous cells and conidia than the other taxa.

Authors: Q. Chen & L. Cai

Calonectria De Not., Comm. Soc. crittog. Ital. 2(fasc. 3): 477. 1867. Fig. 9, Fig. 10.

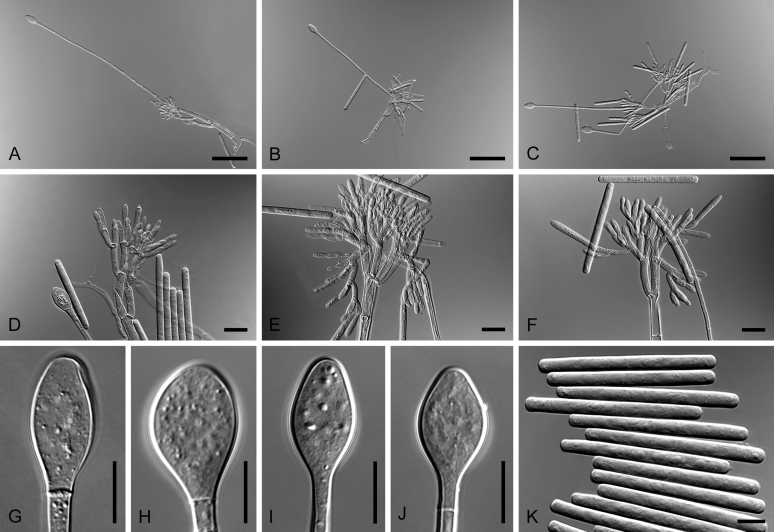

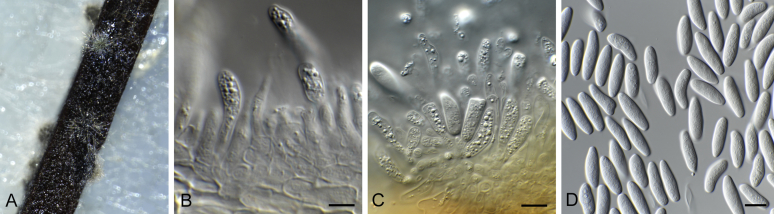

Fig. 9.

Calonectria spp. A−H. Sexual morphs. A−D. Perithecia. A.Calonectria asiatica (ex-type CBS 114073). B.Calonectria braziliensis (ex-type CBS 230.51 × CBS 114257). b Calonectria fujianensis (ex-type CBS 127201). D. Section through perithecium of Calonectria asiatica (ex-type CBS 114073). E−F. Asci. E.Calonectria crousiana (ex-type CBS 127198). F.Calonectria asiatica (ex-type CBS 114073). G−H. Ascospores. G.Calonectria fujianensis (ex-type CBS 127201). H.Calonectria acicola (ex-type CBS 114813). I−AB. Asexual morphs. I−L. Macroconidiophores. I.Calonectria malesiana (ex-type CBS 112752). J.Calonectria macroconidialis (ex-type CBS 114880). K.Calonectria spathulata (ex-type CBS 555.92). L.Calonectria ovata (CBS 111307). M−O. Conidiogenous apparatus. M.Calonectria brachiatica (ex-type CBS 123700). N.Calonectria ecuadoriae (ex-type CBS 111406). O.Calonectria hurae (CBS 114551). P. Microconidiophore of Calonectria reteaudii (ex-type CBS 112144). Q. Megaconidia of Calonectria hurae (CBS 114551). R, S. Macroconidia. R.Calonectria angustata (ex-type CBS 109065). S.Calonectria chinensis (ex-type CBS 114827). T. Microconidia of Calonectria pteridis (ex-type CBS 111793). U−AB. Terminal vesicles of stipe extensions. U.Calonectria brassicae (ex-type CBS 111869). V.Calonectria rumohrae (CBS 109062). W.Calonectria cylindrospora (CBS 119670). X.Calonectria hongkongensis (ex-type CBS 114828). Y.Calonectria chinensis (ex-type CBS 114827). Z.Calonectria humicola (ex-type CBS 125251). AA.Calonectria mexicana (ex-type CBS 110918). AB.Calonectria spathulata (ex-type CBS 555.92). Scale bars: A−C = 500 μm; D−F = 100 μm; G, H, M−P, R−AB = 10 μm; I−L, Q = 20 μm.

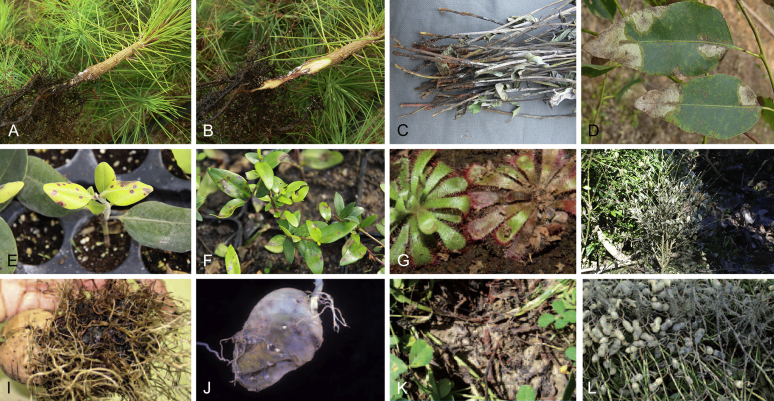

Fig. 10.

Disease symptoms associated with Calonectria spp. A−B. Root and collar rot of Pinus spp. C. Cutting rot of Eucalyptus sp. D. Calonectria leaf blight of Eucalyptus sp. E. Calonectria leaf blight of Metrosideros thomasii. F. Calonectria leaf blight of Myrtus communis. G. Seedling blight of Drosera sp. H. Buxus blight. I. Root rot of Persea americana.J. Potato tuber rot. K−L. Calonectria black rot of Arachis hypogaea.

Synonyms: Cylindrocladium Morgan, Bot. Gaz. 17: 191. 1892.

Candelospora Rea & Hawley, Proc. R. Ir. Acad., Sect. B, Biol. Sci. 13: 11. 1912.

Classification: Sordariomycetes, Hypocreomycetidae, Hypocreales, Nectriaceae.

Type species: Calonectria pyrochroa (Desm.) Sacc. Holotype: Italy, leaves of Magnolia grandiflora, Daldini (as Ca. daldiniana); Lectotype: France, litter of Platanus, Autumn. Desm., Pl. Crypt. France Ed. 2 (2) # 372 (fide Rossman 1979); no culture or DNA data available.

DNA barcodes (genus): LSU, ITS.

DNA barcodes (species): cmdA, his3, tef1, tub2, and rpb2. Table 3. Fig. 11.

Table 3.

DNA barcodes of accepted Calonectria spp.

CBS: Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, Utrecht, the Netherlands; CPC: Culture collection of Pedro Crous, housed at Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute. T indicates ex-type strains.

tub2: partial β-tubulin gene; cmdA: partial calmodulin gene; tef1: partial translation elongation factor 1-alpha gene; his3: partial histone H3 gene; rpb2: RNA polymerase II second largest subunit; ITS: internal transcribed spacers and intervening 5.8S nrDNA; LSU: 28S large subunit RNA gene.

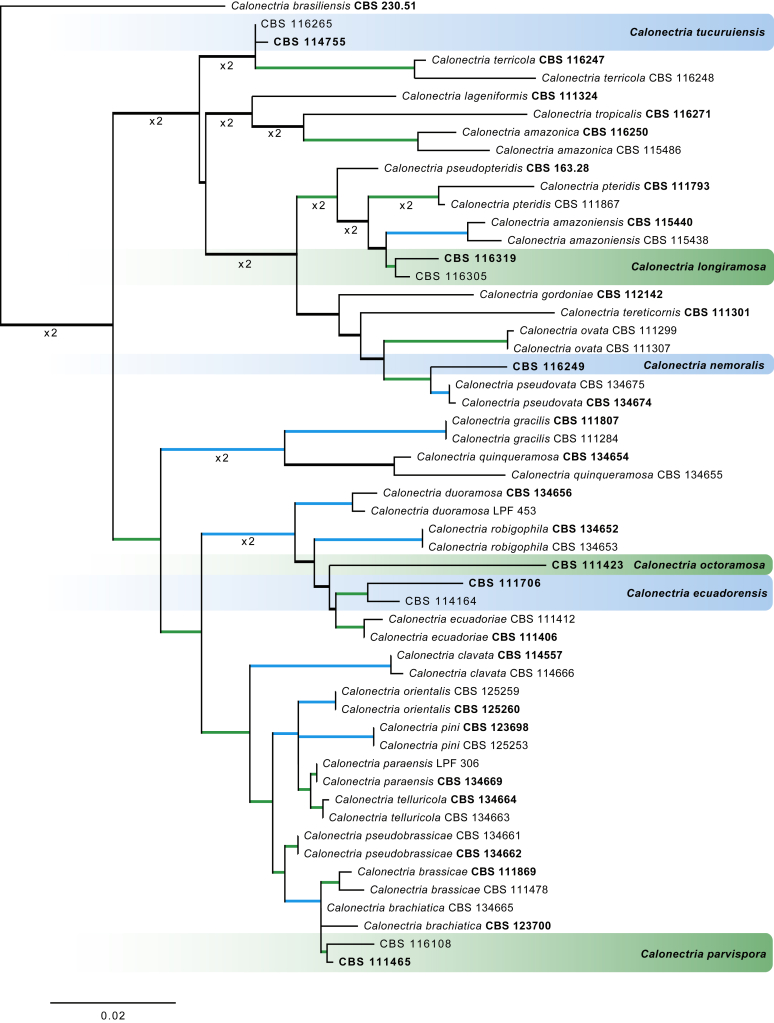

Fig. 11.

The Maximum Likelihood (ML) consensus tree inferred from the combined cmdA, tef1 and tub2 sequence alignments. Thickened lines indicate branches present in the ML, Maximum parsimony (MP) and Bayesian consensus trees. Branches with ML-bootstrap (BS) & MP-BS = 100 % and posterior probabilities (PP) = 1.00 are in blue. Branches with ML-BS & MP-BS ≥ 75 % and PP ≥ 0.95 are in green. The scale bar indicates 0.02 expected changes per site. The tree is rooted to Calonectria braziliensis (CBS 230.51). Ex-type strains are indicated in bold. GenBank accession numbers are indicated in Lombard et al., 2010a, Lombard et al., 2015, Lombard et al., 2016 and Alfenas et al. (2015). TreeBASE: S20877.

Ascomata perithecial, solitary or in groups, globose to subglobose to ovoid, yellow to orange to red or red-brown to brown, turning dark red to red-brown in KOH, rough-walled; ascomatal apex consisting of flattened, thick-walled hyphal elements with rounded tips forming a palisade, discontinuous with warty wall, gradually becoming thinner towards ostiolar canal, and merging with outer periphyses; ascomatal base consisting of dark brown-red, angular cells, merging with an erumpent stroma, cells of outer wall layer continuing into pseudoparenchymatous cells of erumpent stroma. Asci 8-spored, clavate, tapering to a long thin stalk. Ascospores aggregated in upper third of ascus, hyaline, smooth, fusoid with rounded ends, straight to sinuous, unconstricted, or constricted at septa. Megaconidiophores, if present, borne on agar surface or immersed in agar; stipe extensions mostly absent; conidiophores unbranched, terminating in 1–3 phialides, or sometimes with a single subterminal phialide; phialides straight to curved, cylindrical, seemingly producing a single conidium, periclinal thickening and an inconspicuous, divergent collarette rarely visible. Megaconidia hyaline, smooth, frequently remaining attached to phialide, multi-septate, widest in middle, bent or curved, with a truncated base and rounded apical cell. Macroconidiophores consist of a stipe, a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, a stipe extension, and a terminal vesicle; stipe septate, hyaline or slightly pigmented at base, smooth or finely verruculose; stipe extensions septate, straight to flexuous, mostly thin-walled, terminating in a thin-walled vesicle of characteristic shape. Conidiogenous apparatus with 0–1-septate primary branches, up to eight additional branches, mostly aseptate, each terminal branch producing 1–6 phialides; phialides cylindrical to allantoid, straight to curved, or doliiform to reniform, hyaline, aseptate, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous divergent collarette. Macroconidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight or curved, widest at base, middle, or first basal septum, 1- to multi-septate, lacking visible abscission scars, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by colourless slime. Microconidiophores consist of a stipe and a penicillate or subverticillate arrangement of fertile branches; primary branches 0–1-septate, subcylindrical; secondary branches 0–1-septate, terminating in 1–4 phialides; phialides cylindrical, straight to slightly curved, apex with minute periclinal thickening and marginal frill. Microconidia cylindrical, straight to curved, rounded at apex, flattened at base, 1(–3)-septate, held in asymmetrical clusters by colourless slime.

Culture characteristics: Colonies on MEA white to pale brick when young, becoming pale brick to dark sepia when mature, fluffy, cottony, effuse to convex with papillate surface, margin entire, undulate, lobate, or fimbriate, sometimes with abundant chlamydospores forming microsclerotia within medium.

Optimal media and cultivation conditions: CLA to induce sporulation of the asexual morph at 25 °C, while for the sexual morph sterile toothpicks placed on SNA is used at 20 °C.

Distribution: Worldwide.

Hosts: Soil-borne pathogens of forestry, agricultural and horticultural crops representing approximately 100 plant families and 340 plant host species (Crous, 2002, Lombard et al., 2010c).

Disease symptoms: Leaf spots, leaf and shoot blights, cutting rot, stem cankers, damping-off and root rot.

Notes: The genus Calonectria presently includes 151 species of which only Ca. hederae and Ca. pyrochroa are not supported by ex-type cultures and supplementary DNA barcodes. Species delimitation based on morphology alone is complicated by the large number of cryptic taxa recognised in this genus (Lombard et al. 2016). The perithecia of several Calonectria spp. are morphologically similar. The cylindrocladium-like asexual morph, the life phase most commonly found in nature, is extensively used for taxon identification, although it is complicated by the morphological overlap of some cryptic species. For accurate species delimitation, phylogenetic inference of the cmdA, tef1 and tub2 (or combinations of these) is required.

References: Crous 2002 (morphology, pathogenicity and monograph); Lombard et al., 2010a, Lombard et al., 2010b, Lombard et al., 2010c, Lombard et al., 2010d, Lombard et al., 2010a, Lombard et al., 2010b, Lombard et al., 2010c, Lombard et al., 2010d, Lombard et al., 2010a, Lombard et al., 2010b, Lombard et al., 2010c, Lombard et al., 2010d (morphology, phylogeny and key of Calonectria spp.); Alfenas et al. 2015 (morphology and phylogeny).

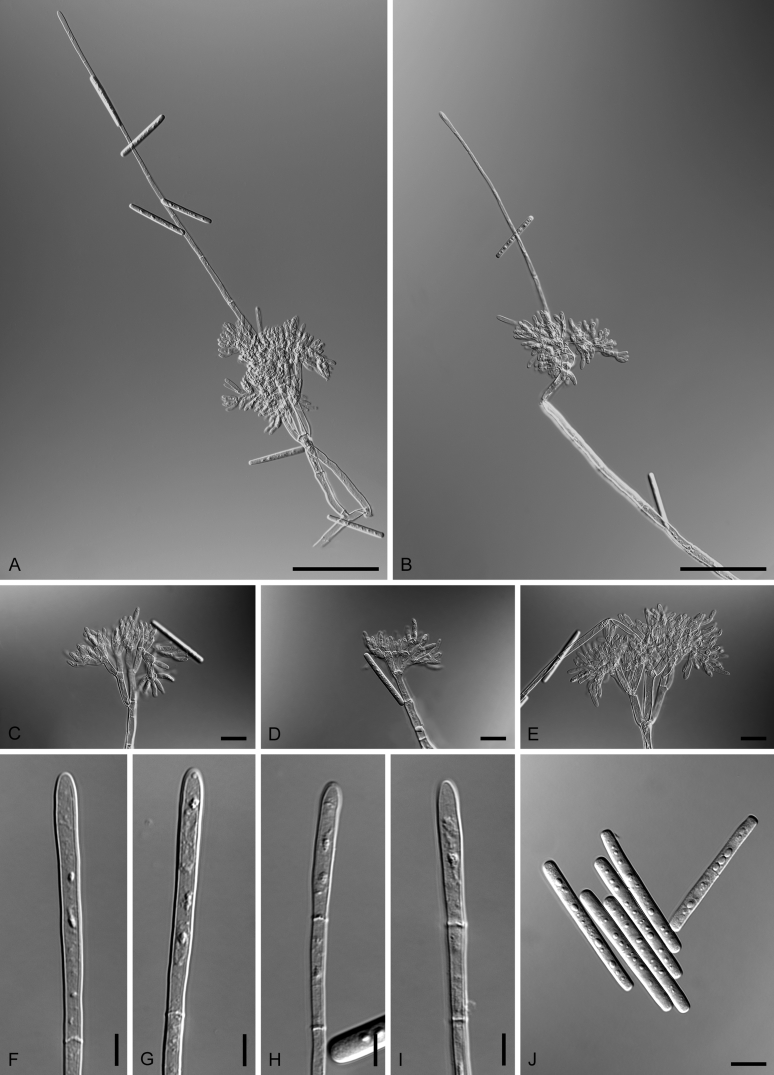

Calonectria ecuadorensis L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB820849. Fig. 12.

Fig. 12.

Calonectria ecuadorensis (ex-type CBS 111706). A, B. Macroconidiophores. C−E. Conidiogenous apparatus with conidiophore branches and doliiform to reniform phialides. F−I. Clavate vesicles. J. Macroconidia. Scale bars: A, B = 50 μm; C−J = 10 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to Ecuador, the country where this fungus was collected.

Macroconidiophores consist of a stipe bearing a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and a stipe extension terminating in a vesicle; stipe septate, hyaline, smooth, 55–70 × 6–10 μm; stipe extension septate, straight to flexuous, 130–280 μm long, 3–6 μm wide at apical septum, terminating in a clavate vesicle, 4–6 μm diam. Conidiogenous apparatus 45–90 μm wide, and 20–90 μm long; primary branches aseptate, 13–31 × 4–6 μm; secondary branches aseptate, 13–23 × 4–5 μm; tertiary branches aseptate, 9–15 × 3–4 μm, each terminal branch producing 2–6 phialides; phialides doliiform to reniform, hyaline, aseptate, 6–11 × 2–4 μm, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Macroconidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight, (34–)35–39(–44) × (3–)3.5–4.5(–5) μm (av. 37 × 4 μm), 1-septate, lacking a visible abscission scar, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by colourless slime. Mega- and microconidia not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies moderately fast growing (35–55 mm diam) on MEA after 1 wk at room temperature; surface rosy-buff to cinnamon with sparse white woolly aerial mycelium and abundant sporulation on aerial mycelium and colony surface; reverse rosy-buff to cinnamon to sepia with abundant chlamydospores throughout medium, forming microsclerotia.

Material examined: Ecuador, from soil, 20 Jun. 1997, M.J. Wingfield (holotype CBS H-23134, culture ex-type CBS 111706 = CPC 1636); ibid., culture CBS 114164 = CPC 1634.

Notes: Calonectria ecuadorensis can be distinguished from Ca. ecuadoriae (Crous et al. 2006a) by its fewer branches in the conidiogenous apparatus. Also, the conidia of Ca. ecuadorensis [(34–)35–39(–44) × (3–)3.5–4.5(–5) μm (av. 37 × 4 μm)] are smaller than those of Ca. ecuadoriae [(45–)48–55(–65) × (4–)4.5(–5) μm (av. 51 × 4.5 μm); Crous et al. 2006a].

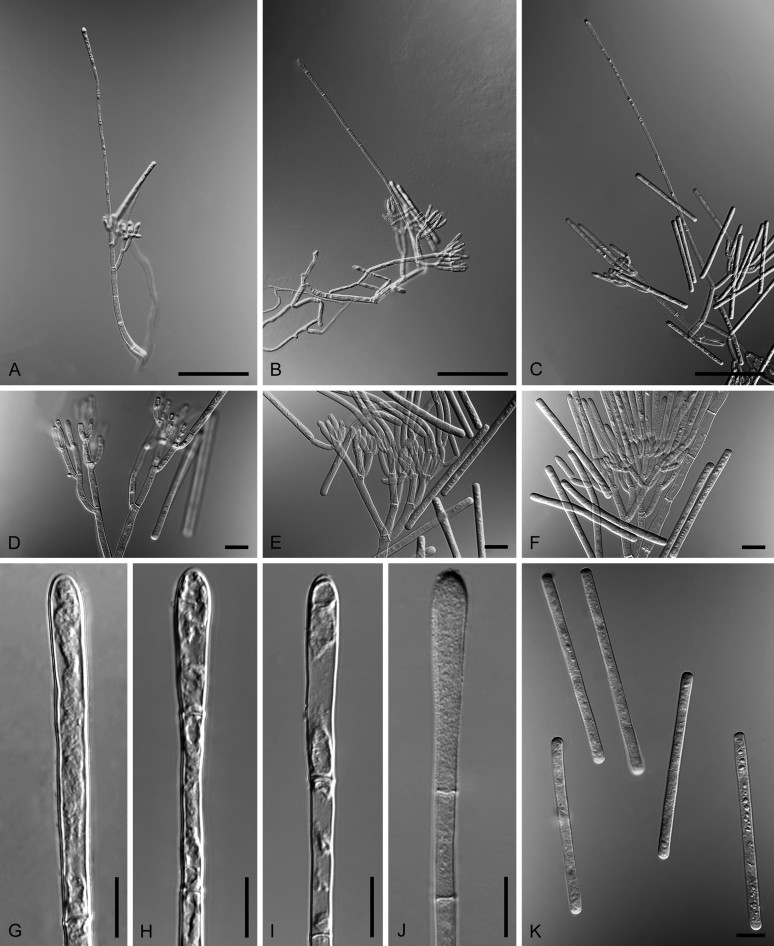

Calonectria longiramosa L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB820843. Fig. 13.

Fig. 13.

Calonectria longiramosa (ex-type CBS 116319). A−C. Macroconidiophores. D−F. Conidiogenous apparatus with conidiophore branches and elongate doliiform to allantoid phialides. G−J. Clavate vesicles. K. Macroconidia. Scale bars: A−C = 50 μm; D−K = 10 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to the characteristic long fertile branches of the conidiogenous apparatus in this fungus.

Macroconidiophores consist of a stipe bearing a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and a stipe extension terminating in a vesicle; stipe septate, hyaline, smooth, 100–245 × 6–9 μm; stipe extension septate, straight to flexuous, 155–310 μm long, 4–6 μm wide at apical septum, terminating in a clavate vesicle, 5–8 μm diam. Conidiogenous apparatus 50–85 μm wide, and 60–140 μm long; primary branches aseptate to 1-septate, 22–42 × 4–6 μm; secondary branches aseptate, 15–35 × 3–6 μm; tertiary branches aseptate, 12–30 × 3–6 μm; quaternary branches aseptate, 11–19 × 3–6 μm each terminal branch producing 2–4 phialides; phialides elongate doliiform to allantoid, hyaline, aseptate, 8–16 × 2–4 μm, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Macroconidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight to slightly curved, (57–)66–76(–84) × (3–)4.5–5.5(–6) μm (av. 71 × 5 μm), 1-septate, lacking a visible abscission scar, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by colourless slime. Mega- and microconidia not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies moderately fast growing (35–70 mm diam) on MEA after 1 wk at room temperature; surface amber with moderate white, woolly aerial mycelium and moderate sporulation on the aerial mycelium and colony surface; reverse amber with abundant chlamydospores throughout the medium, forming microsclerotia.

Material examined: Brazil, Amazon, from Eucalyptus sp., 1993, P.W. Crous & A.C. Alfenas (holotype CBS H-22759, culture ex-type CBS 116319 = CPC 3761); ibid., cultures CBS 116305 = CPC 3765.

Notes: Calonectria longiramosa is a new species in the Ca. pteridis complex. This species is characterised by the long fertile branches of the conidiogenous apparatus distinguishing it from the other species in this complex (Alfenas et al. 2015).

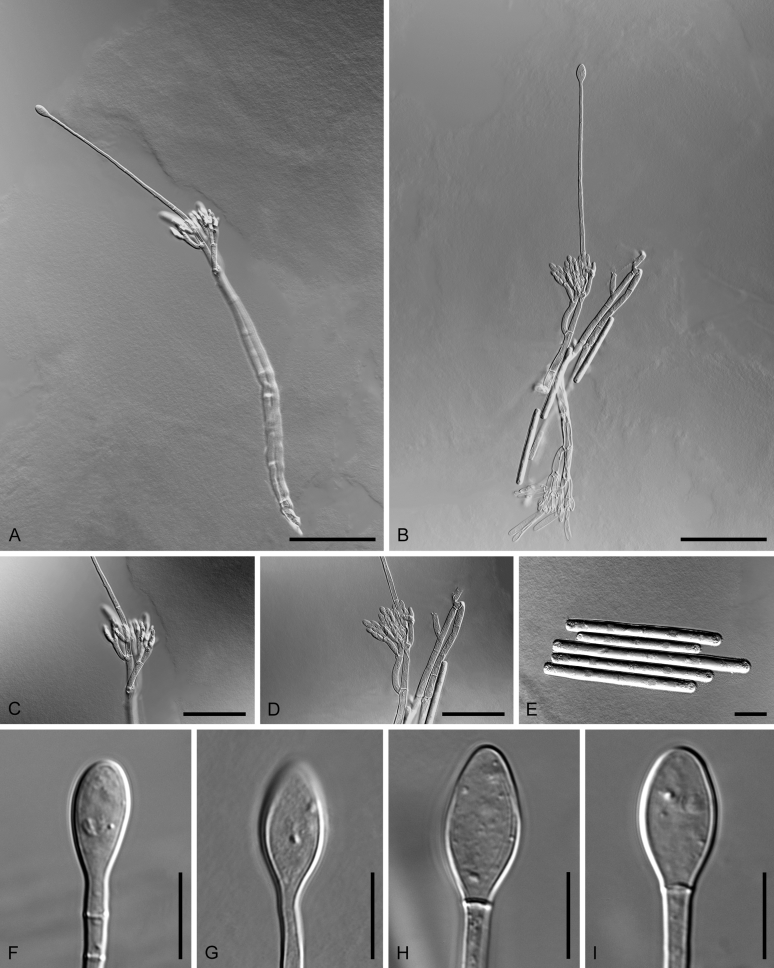

Calonectria nemoralis L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB820850. Fig. 14.

Fig. 14.

Calonectria nemoralis (ex-type CBS 116319). A, B. Macroconidiophores. C−D. Conidiogenous apparatus with conidiophore branches and doliiform to reniform phialides. E. Macroconidia. F−I. Fusiform to ovoid vesicles. Scale bars: A, B = 50 μm; C−I = 10 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to the environment, a Eucalyptus plantation, from where this fungus was collected.

Macroconidiophores consist of a stipe bearing a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and a stipe extension terminating in a vesicle; stipe septate, hyaline, smooth, 40–165 × 6–8 μm; stipe extension septate, straight to flexuous, 140–210 μm long, 3–5 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in a fusiform to ovoid vesicle, 7–9 μm diam. Conidiogenous apparatus 20–45 μm wide, and 40–55 μm long; primary branches aseptate, 18–24 × 3–6 μm; secondary branches aseptate, 11–19 × 3–5 μm, each terminal branch producing 2–4 phialides; phialides elongate doliiform to reniform, hyaline, aseptate, 6–14 × 2–4 μm, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Macroconidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight, (44–)47–59(–71) × (3–)3.5–4.5(–6) μm (av. 53 × 4 μm), 1-septate, lacking a visible abscission scar, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by colourless slime. Mega- and microconidia not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies moderately fast growing (35–55 mm diam) on MEA after 1 wk at room temperature; surface sienna with sparse buff to white, woolly aerial mycelium with moderate sporulation on the aerial mycelium and colony surface; reverse sienna with abundant chlamydospores throughout the medium, forming microsclerotia.

Material examined: Brazil, from soil in Eucalyptus plantation, 1996, P.W. Crous (holotype CBS H-23135, culture ex-type CBS 116249 = CPC 3533).

Notes: Calonectria nemoralis is closely related to Ca. pseudovata. The macroconidia of Ca. nemoralis [(44–)47–59(–71) × (3–)3.5–4.5(–6) μm (av. 53 × 4 μm)] are smaller than those of Ca. pseudovata [(55–)67–70(–80) × (4–)5 (–7) μm (av. 69 × 5 μm); Alfenas et al. 2015]. Furthermore, no microconidiophores and microconidia were observed in Ca. nemoralis, although they are readily produced by Ca. pseudovata (Alfenas et al. 2015).

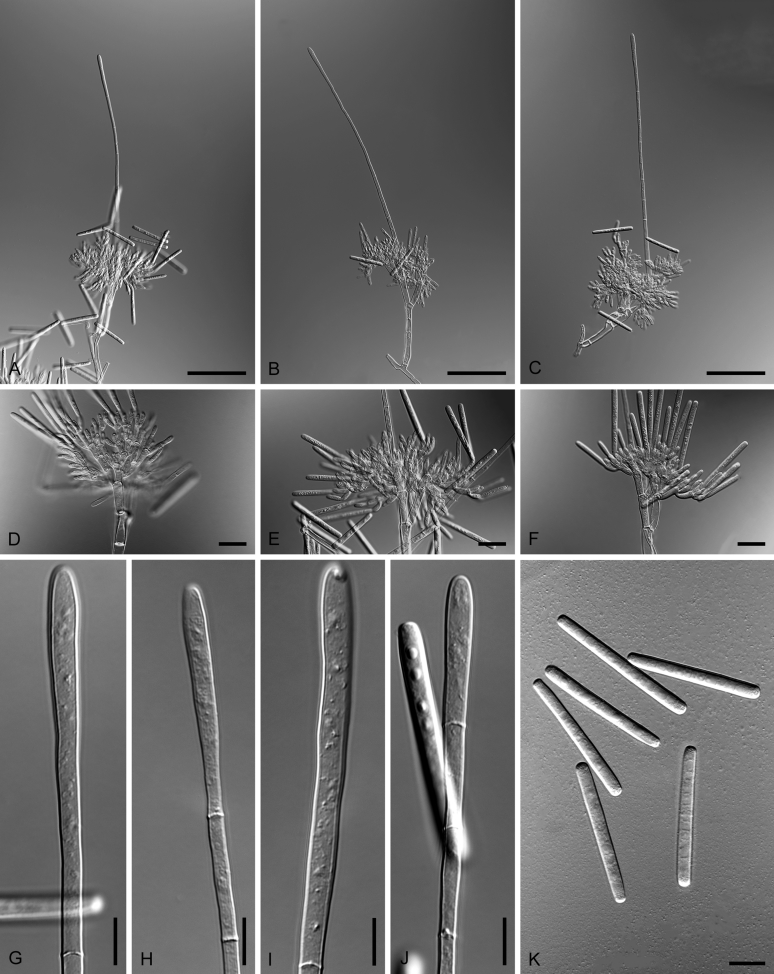

Calonectria octoramosa L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB820851. Fig. 15.

Fig. 15.

Calonectria octoramosa (ex-type CBS 111423). A−C. Macroconidiophores. D−F. Conidiogenous apparatus with conidiophore branches and doliiform to reniform phialides. G−J. Clavate vesicles. K. Macroconidia. Scale bars: A−C = 20 μm; D−K = 10 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to the eight levels of branching of the conidiogenous apparatus.

Macroconidiophores consist of a stipe bearing a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and a stipe extension terminating in a vesicle; stipe septate, hyaline, smooth, 34–170 × 6–10 μm; stipe extension septate, straight to flexuous, 118–262 μm long, 3–8 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in a clavate vesicle, 4–8 μm diam. Conidiogenous apparatus 58–128 μm wide, and 50–90 μm long; primary branches aseptate, 14–31 × 5–8 μm; secondary branches aseptate, 10–23 × 4–6 μm; tertiary branches aseptate, 7–19 × 3–5 μm; quaternary branches and additional branches (–8) aseptate, 8–14 × 3–5 μm, each terminal branch producing 2–6 phialides; phialides doliiform to reniform, hyaline, aseptate, 6–12 × 3–5 μm, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Macroconidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight, (32–)34–38(–39) × 4–5 μm (av. 36 × 4 μm), 1(–3)-septate, lacking a visible abscission scar, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by colourless slime. Mega- and microconidia not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies fast growing (60–75 mm diam) on MEA after 1 wk at room temperature; surface cinnamon to brick with abundant white woolly aerial mycelium and abundant sporulation on the aerial mycelium and colony surface; reverse brick to sepia with abundant chlamydospores throughout the medium, forming microsclerotia.

Material examined: Ecuador, from soil, 20 Jun. 1997, M.J. Wingfield (holotype CBS H-23136, culture ex-type CBS 111423 = CPC 1650).

Notes: Calonectria octoramosa is a new species in the Ca. brassicae complex. It can be distinguished from other species in this complex by having eight levels of branching in its conidiogenous apparatus.

Calonectria parvispora L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB820844. Fig. 16.

Fig. 16.

Calonectria parvispora (ex-type CBS 111465). A−C. Macroconidiophores. D−F. Conidiogenous apparatus with conidiophore branches and doliiform to reniform phialides. G−J. Clavate vesicles. K. Macroconidia. Scale bars: A−C = 20 μm; D−K = 10 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to the small macroconidia of this fungus.

Macroconidiophores consist of a stipe bearing a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and a stipe extension terminating in a vesicle; stipe septate, hyaline, smooth, 36–152 × 7–9 μm; stipe extension septate, straight to flexuous, 137–277 μm long, 3–6 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in a clavate vesicle, 4–8 μm diam. Conidiogenous apparatus 56–92 μm wide, and 50–70 μm long; primary branches aseptate, 16–34 × 4–7 μm; secondary branches aseptate, 11–20 × 4–6 μm; tertiary branches aseptate, 7–15 × 3–5 μm; quaternary branches and additional branches (–6) aseptate, 8–16 × 3–5 μm, each terminal branch producing 2–6 phialides; phialides doliiform to reniform, hyaline, aseptate, 7–12 × 3–5 μm, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Macroconidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight, (24–)26–32(–36) × (3–)3.5–4.5(–5) μm (av. 29 × 4 μm), 1-septate, lacking a visible abscission scar, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by colourless slime. Mega- and microconidia not observed.

Culture characteristics. Colonies fast growing (50–75 mm diam) on MEA after 1 wk at room temperature; surface umber to sepia with abundant buff to white, woolly aerial mycelium and abundant sporulation on the aerial mycelium and colony surface; reverse amber to sepia with abundant chlamydospores throughout the medium, forming microsclerotia.

Material examined: Brazil, from soil, Jun. 1998, A.C. Alfenas (holotype CBS H-22765, culture ex-type CBS 111465 = CPC 1902). Colombia, La Paz, Rodal Seuiller, from soil, Jan. 1994, P.W. Crous, CBS 116108 = CPC 726.

Notes: Calonectria parvispora is a new species in the Ca. brassicae complex (Lombard et al., 2009, Alfenas et al., 2015). The macroconidia of Ca. parvispora [(24–)26–32(–36) × (3–)3.5–4.5(–5) μm (av. 29 × 4 μm)] are smaller than those of Ca. clavata [(44–)50–70(–80) × (4–)5–6 μm (av. 65 × 5 μm); Crous 2002], Ca. brachiatica [(37–)40–48(–50) × 4–6 μm (av. 44 × 5 μm); Lombard et al. 2009], Ca. brassicae [(38–)40–55(–65) × (3.5–)4–5(–6) μm (av. 53 × 4.5 μm); Crous 2002], Ca. ecuadoriae [(45–)48–55(–65) × (4–)4.5(–5) μm (av. 51 × 4.5 μm); Crous et al. 2006a], Ca. gracilipes [(35–)40–48(–60) × 4–5(–6) μm (av. 45 × 4.5 μm); Crous 2002] and Ca. gracilis [(40–)53–58(–65) × (3.5–)4–5 μm (av. 56 × 4.5 μm); Crous 2002].

Calonectria tucuruiensis L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB820845. Fig. 17.

Fig. 17.

Calonectria tucuruiensis (ex-type CBS 114755). A−C. Macroconidiophores. D−F. Conidiogenous apparatus with conidiophore branches and elongate doliiform to reniform phialides. G−J. Fusiform to ovoid to ellipsoid vesicles. K. Macroconidia. Scale bars: A−C = 50 μm; D−K = 10 μm.

Etymology: Name refers to Tucuruí, the region in Brazil from which this fungus was collected.

Macroconidiophores consist of a stipe bearing a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and a stipe extension terminating in a vesicle; stipe septate, hyaline, smooth, 35–105 × 6–9 μm; stipe extension septate, straight to flexuous, 165–290 μm long, 4–6 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in a fusiform to ovoid to ellipsoid vesicle, 9–12 μm diam. Conidiogenous apparatus 40–95 μm wide, and 40–90 μm long; primary branches aseptate, 19–32 × 4–7 μm; secondary branches aseptate, 10–28 × 3–5 μm; tertiary branches aseptate, 11–16 × 3–6 μm; quaternary branches aseptate, 8–14 × 3–4 μm each terminal branch producing 2–4 phialides; phialides elongate doliiform to reniform, hyaline, aseptate, 8–17 × 3–5 μm, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Macroconidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight, (51–)57–69(–71) × (4–)4.5–5.5(–6) μm (av. 63 × 5 μm), 1-septate, lacking a visible abscission scar, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by colourless slime. Mega- and microconidia not observed.

Culture characteristics. Colonies fast growing (55–75 mm diam) on MEA after 1 wk at room temperature; surface cinnamon to amber with sparse, buff to white, woolly aerial mycelium and abundant sporulation on the aerial mycelium and colony surface; reverse sienna to amber with abundant chlamydospores throughout the medium, forming microsclerotia.

Material examined: Brazil, Tucuruí, from leaves of Eucalyptus tereticornis, 8 Aug. 1996, P.W. Crous (holotype CBS H-22777, culture ex-type CBS 114755 = CPC 1403); ibid., CBS 116265 = CPC 3552.

Notes: Calonectria tucuruiensis is closely related to Ca. terricola (Fig. 11). The macroconidia of Ca. tucuruiensis [(51–)57–69(–71) × (4–)4.5–5.5(–6) μm (av. 63 × 5 μm)] are larger than those of Ca. terricola [(40–)43–49(–53) × (3–)4–5(–6) μm (av. 46 × 4.5 μm); Lombard et al. (2016)].

Authors: L. Lombard & P.W. Crous

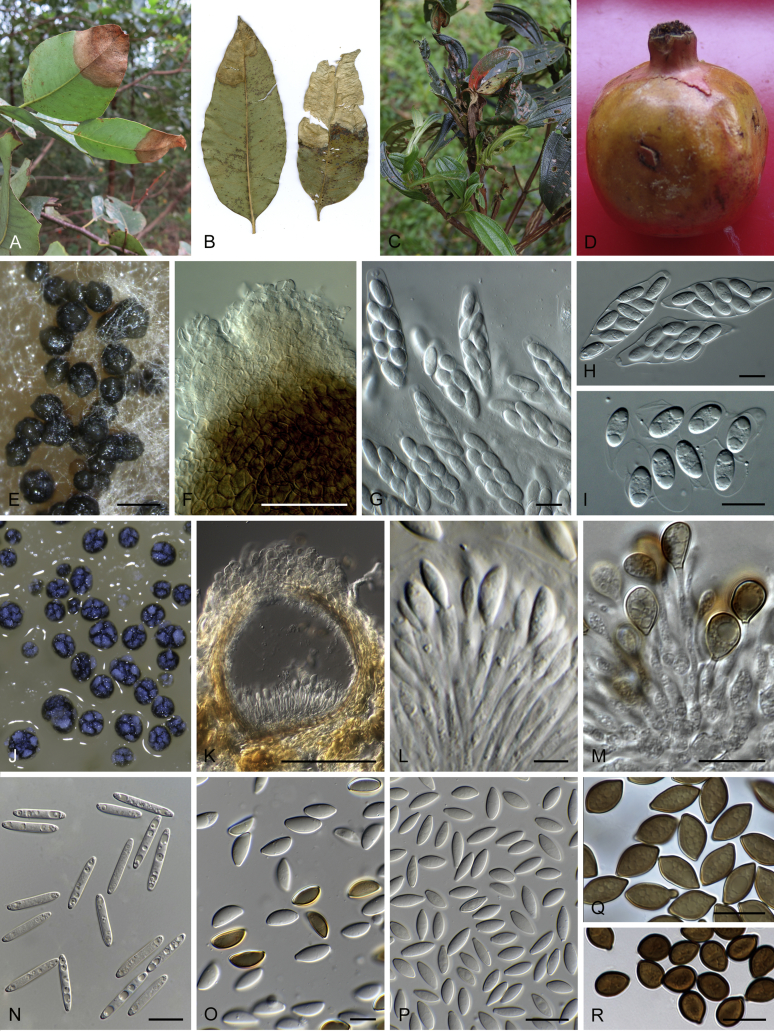

Ceratocystis Ellis & Halst., New Jersey Agric. Coll. Exp. Sta. Bull. 76: 14. 1890. Fig. 18.

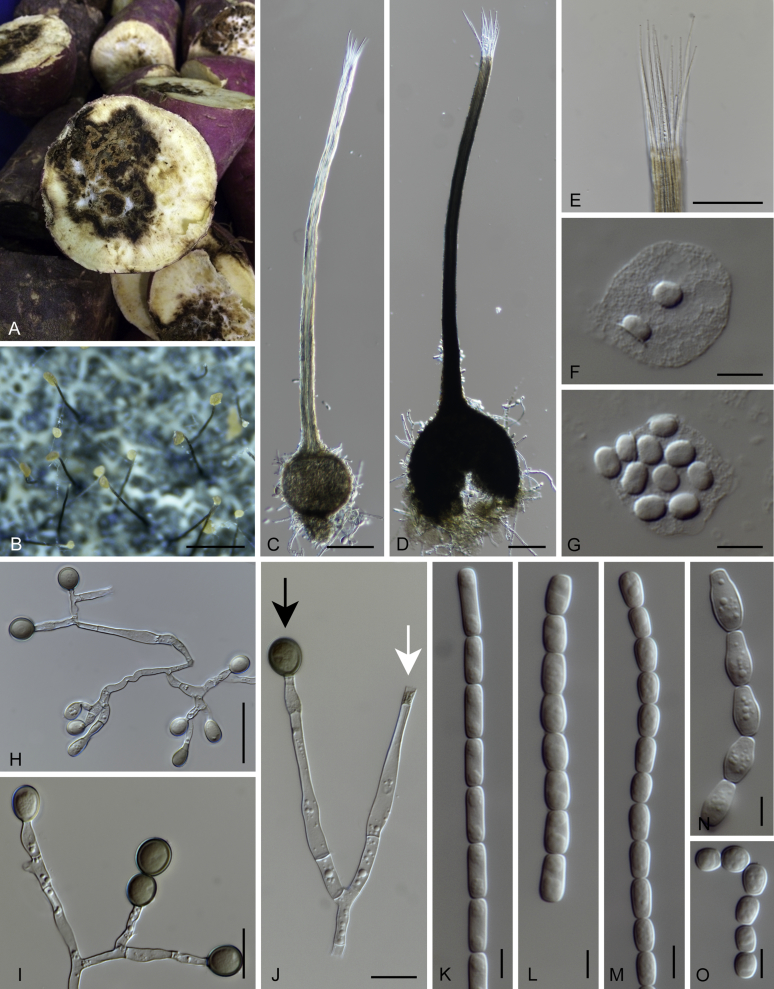

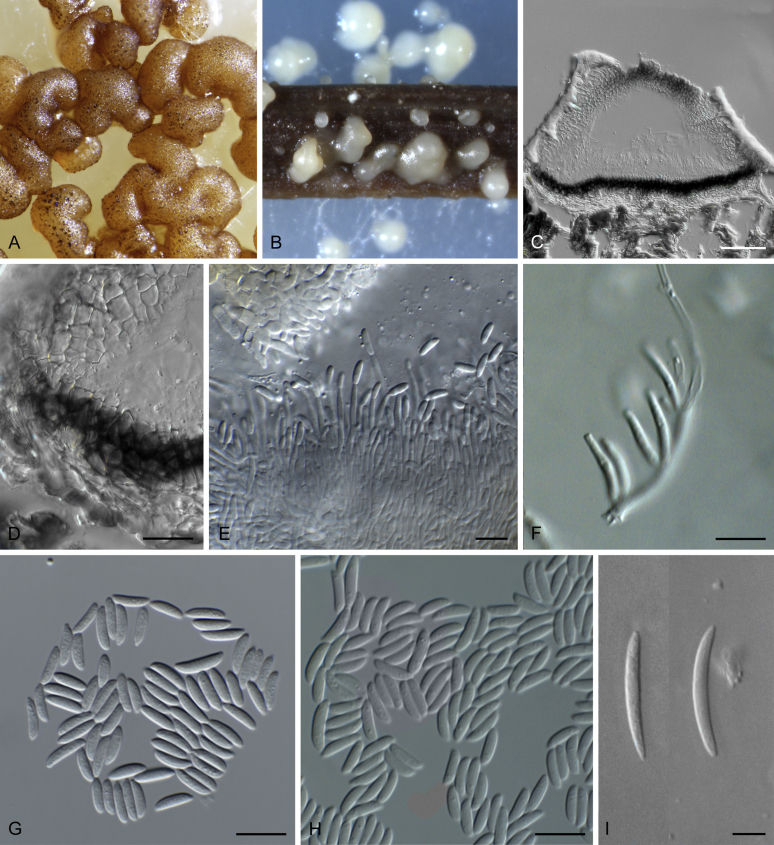

Fig. 18.

A. Sweet potatoes (Ipomea batatas) infected with Ceratocystis fimbriata. B−O. Microscopic features of Ceratocystis fimbriata (CBS 114723 = CMW 14799) on 2 % MEA. B. Ascomata with yellowish droplets of ascospores at tips of necks, with asexual state (white background). C. Young ascoma. D. Mature ascoma. E. Ostiolar hyphae. F, G. Ascospores. H, I. Aleurioconidia. J. Conidiogenous cells producing aleurioconidia (black arrow) and cylindrical-shape conidia (white arrow). K–O. Conidia of various shapes in chains. Scale bars: B = 500 μm; C, D = 100 μm; E = 50 μm; F, G, K–O = 10 μm; H = 50 μm; I, J = 25 μm.

Synonym: Rostrella Zimm., Meded. Lands Plantentuin 37: 24, 41. 1900.

Classification: Sordariomycetes, Hypocreomycetidae, Microascales, Ceratocystidaceae.

Type species: Ceratocystis fimbriata Ellis & Halst. Neotype: BPI 595863.

DNA barcodes (genus): 60S, LSU, mcm7.

DNA barcodes (species): ITS, bt1, tef1, rpb2, ms204. Table 4.

Table 4.

DNA barcodes of accepted Ceratocystis spp.

CBS: Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, Utrecht, the Netherlands; MAFF: Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan. T and PT indicate ex-type and ex-paratype, respectively.

ITS: internal transcribed spacers and intervening 5.8S nrDNA; bt1: partial β-tubulin gene; tef1: partial translation elongation factor 1-alpha gene, ms204: partial guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit beta-like protein gene; rpb2: partial RNA polymerase II second largest subunit gene. ∗Multiple ITS types reported.

Ascomata perithecial, scattered or gregarious, immersed, partially embedded or superficial on the substrate; bases subglobose to globose or obpyriform, brown to black, covered with undifferentiated hyphae; ostiolar necks central, long, tapering towards apex; ascomatal apex straight or undulate, unbranched or branched, brown to black and becoming paler; ostiolar hyphae divergent or convergent, non-septate, straight, tapering towards apex, hyaline to light brown. Asci evanescent. Ascospores hyaline, 1-celled, ellipsoidal with gelatinous sheath which gives hat-shaped impression, accumulating in white, creamy to yellow masses at tips of necks. Conidiophores branched, straight or flexuous, hyaline to pale brown. Conidiogenous cells endophialidic, flask-shaped (lageniform) producing various shapes of cylindrical conidia or tubular-form producing barrel-shaped (doliiform) conidia, either lageniform alone or both forms present. Conidia hyaline, 1-celled, doliiform to cylindrical. Aleurioconidia (in some literature as chlamydospores) absent or present, pale brown to dark brown, pyriform, ellipsoidal to globose, singly or in chains.

Culture characteristics: Colonies showing circular growth with undulate margins, mycelium submerged to aerial, colour ranging from moderate yellowish brown to greyish or brownish olive when mature, releasing sweet fruity aroma. No growth on cycloheximide.

Optimal media and cultivation conditions: 2 % MEA incubated at 25 °C. Addition of thiamin stimulates the development of sexual morph.

Distribution: Worldwide.

Hosts: Herbaceous root crops, Ipomea batatas (sweet potato), wounds or larval tunnels of woody angiosperms, Acacia, Annona, Carya, Citrus, Coffea, Colocacia, Colophospermum, Combretum, Corymbia, Cunninghamia, Dalbergia, Eucalyptus, Coffea, Mangifera, Platanus, Populus, Prosopis, Punica, Quercus, Rapanea, Saccharum, Schizolobium, Schotia, Styrax, Syzygium, Terminalia, Theobroma. Some known to be vectored by flies (Diptera), non-specific ambrosia beetles (Scolytinae), or nitidulid beetles (Nitidulidae), but without specific insect associates.

Disease symptoms: Root rot, cankers and vascular stain.

Notes: Ceratocystis sensu lato included a heterogeneous group of fungi classified under this generic name due to similar morphology resulting from convergent evolution, despite their diverse ecological and biological features (Upadhyay 1981). The group has recently been divided into seven more narrowly defined homogeneous genera, supported by multigene phylogenies, morphological similarities and ecological commonality (Wingfield et al., 2013a, De Beer et al., 2014). The family Ceratocystidaceae includes nine genera, namely Ambrosiella, Ceratocystis, Chalaropsis, Davidsoniella, Endoconidiophora, Huntiella, Thielaviopsis, Meredithiella and Phialophoropsis (De Beer et al., 2014, Mayers et al., 2015). Ceratocystis sensu stricto is now restricted to those species producing ascomata with smooth bases, ascospores with hat-shaped sheaths, and thielaviopsis-like asexual morphs, which differentiate them from other genera (De Beer et al. 2014). Within Ceratocystis, morphological differences between species are insignificant and phylogenies based on multiple gene regions are used to distinguish them from each other (Fourie et al. 2015). The ITS region has been widely used for delimiting species of Ceratocystis (Schoch et al. 2012). However, discovery of multiple ITS types within single species in the genus (Al Adawi et al., 2013, Naidoo et al., 2013, Harrington et al., 2014) raised an awareness that the ITS region alone should not be applied to delimit species in Ceratocystis, and that additional gene regions should also be considered. Loci such as bt1 and tef1 do not provide good species resolution on their own, but provide strong support in combination with ITS (Fourie et al. 2015). The loci rpb2 and ms204 give stronger resolution than tef1 and bt1, but also need to be used in combination with ITS (Fourie et al. 2015).

References: Hunt, 1956, Upadhyay, 1981 (morphology); Nag Raj and Kendrick, 1975, Paulin-Mahady et al., 2002 (asexual morphs and species); Kile, 1993, Van Wyk et al., 2013 (pathogenicity); De Beer et al. 2013a (higher classification); De Beer et al. 2013b (nomenclator); Wilken et al., 2013, Van der Nest et al., 2014a, Van der Nest et al., 2014b, Wingfield et al., 2015, Wingfield et al., 2016a, Wingfield et al., 2016b (genomes); Wingfield et al., 2013a, De Beer et al., 2014 (generic definitions and phylogenetic relationships); Wingfield et al. 2013b (international spread).

Authors: I. Barnes, S. Marincowitz, Z.W. de Beer, & M.J. Wingfield

Cladosporium Link, Mag. Gesell. naturf. Freunde, Berlin 7: 37. 1816 (1815). Fig. 19.

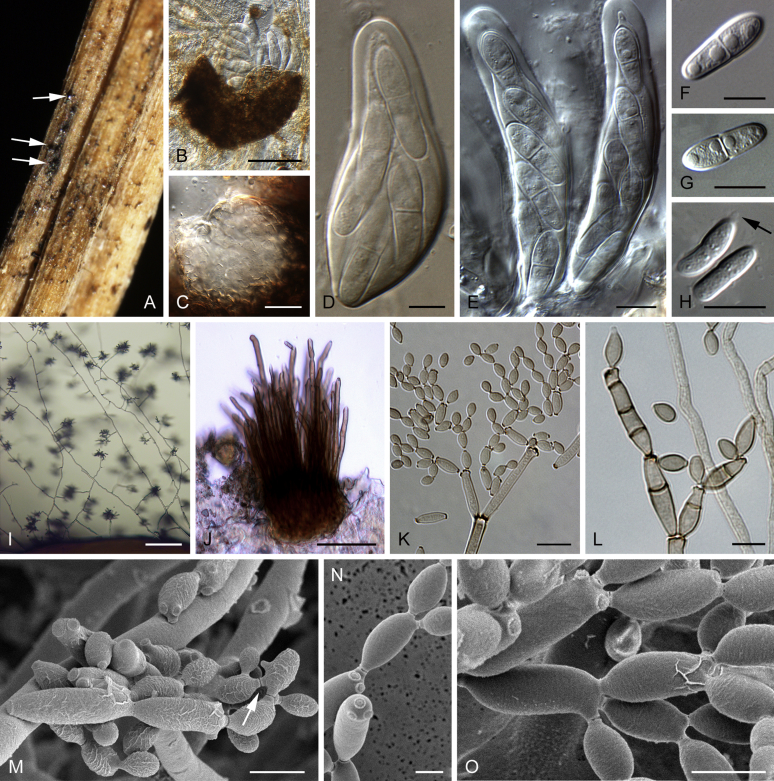

Fig. 19.

Cladosporium spp. A–H. Sexual morphs. A. Ascomata on host tissue (arrows) of Cladosporium silenes (holotype CBS H-19874). B. Ascoma and asci of Cladosporium herbarum (CPC 11600). C. Ostiole of Cladosporium macrocarpum (CBS 299.67). D, E. Asci of Cladosporium herbarum (CPC 11600). F, G. Ascospores of Cladosporium herbarum (CPC 11600). H. Ascospores (arrow denotes mucoid appendage) of Cladosporium silenes (holotype CBS H-19874). I–O. Asexual morphs. I. Conidiophores of Cladosporium halotolerans (ex-type CBS 119416). J. Fascicle of conidiophores of Cladosporium soldanellae (BPI 427476). K. Macronematous conidiophores and conidial chains of Cladosporium cladosporioides (ex-neotype CBS 112388). L. Conidial chains, septa of secondary ramoconidia distinctly darkened of Cladosporium paracladosporioides (ex-type CBS 171.54). M. CryoSEM of different types of conidia on aerial structures of Cladosporium exile (ex-type CBS 125987). Note a remarkable pattern of blastoconidium formation (backwards) (arrow). N. Secondary ramoconidia, conidia and scars of Cladosporium perangustum (ex-type CBS 125996). O. Whorls of secondary ramoconidia and conidia of Cladosporium scabrellum (ex-type CBS 126358). Scale bars: B, C, M, O = 5 μm; D–H, K, L = 10 μm; I = 100 μm; J = 50 μm; N = 2 μm. Pictures taken from Bensch et al. (2012).

For synonyms see Bensch et al. (2012).

Classification: Dothideomycetes, Dothideomycetidae, Capnodiales, Cladosporiaceae.

Type species: Cladosporium herbarum (Pers. : Fr.) Link. Lectotype: L 910.225-733. Epitype and ex-epitype culture: CBS H-19853, CPC 12100 = CBS 121621.

DNA barcodes (genus): LSU.

DNA barcodes (species): act and tef1; in a few cases tub2. Table 5. Fig. 20.

Table 5.

DNA barcodes of accepted Cladosporium spp.

ATCC: American Type Culture Collection, Virginia, USA; CBS: Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, Utrecht, the Netherlands; CPC: Culture collection of Pedro Crous, housed at Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute. T, ET, NT and RS indicate ex-type, ex-epitype, ex-neotype and reference strains, respectively.

ITS: internal transcribed spacers and intervening 5.8S nrDNA; act: partial actin gene; tef1: partial translation elongation factor 1-alpha gene.

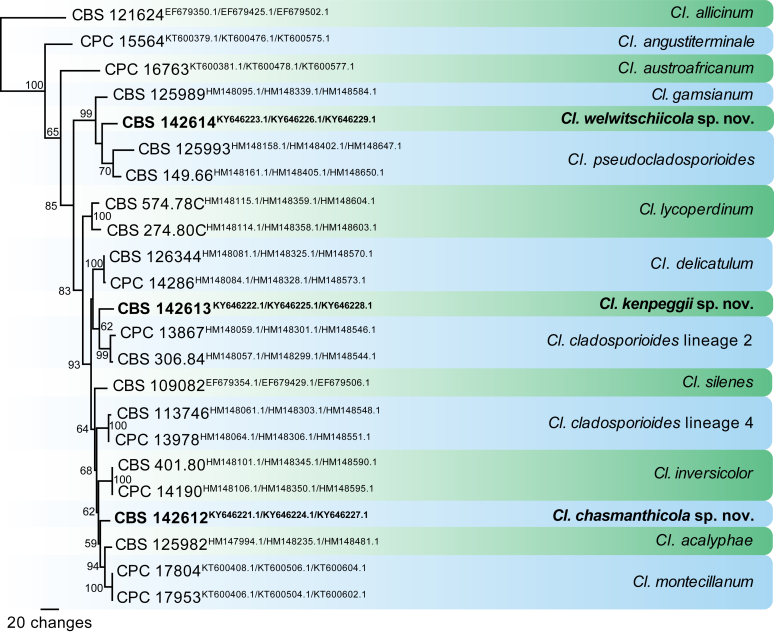

Fig. 20.

The first of two equally most parsimonious trees obtained from a heuristic search of the combined ITS/tef1/actA alignment. The tree was rooted to Cladosporium allicinum CBS 121624 and the novel species described in this study are shown in bold. Bootstrap support values from 1000 replicates are shown at the nodes and the scale bar represents the number of changes. GenBank accession numbers are indicated in superscript (ITS/tef1/actA). TreeBASE: S20877.

Ascomata pseudothecial, black to red-brown, globose, inconspicuous and immersed beneath stomata to superficial, situated on a reduced stroma, with 1(–3) short, periphysate ostiolar necks; periphysoids frequently growing down into cavity; ascomatal wall consisting of 3–6 layers of textura angularis. Pseudoparaphyses frequently present in mature ascomata, hyaline, septate, subcylindrical. Asci fasciculate, short-stalked or not, subsessile, bitunicate, obovoid to broad ellipsoid or subcylindrical, straight to slightly curved, 8-spored. Ascospores bi- to multiseriate, hyaline, obovoid to ellipsoid-fusiform, with irregular luminar inclusions, mostly thick-walled, straight to slightly curved, frequently becoming brown and verruculose in asci, at times covered in mucoid sheath. Dematiaceous hyphomycetes. In vivo: Mycelium internal or external, superficial; hyphae branched, septate, subhyaline to usually pigmented, smooth, sometimes slightly rough-walled to verruculose. Stromata absent to sometimes well-developed. Conidiophores mononematous, usually macronematous, solitary, fasciculate, in small to large fascicles, loosely to densely caespitose, usually erect, occasionally subdecumbent, decumbent or repent, straight to flexuous, unbranched or branched, continuous to septate, subhyaline to usually distinctly pigmented, smooth to verruculose, proliferation holoblastic, occasionally enteroblastic (after a period when growth has stopped and then resumed), usually sympodial, rarely monopodial (sometimes leaving coarse annellations from repeated enteroblastic proliferation). Conidiogenous cells integrated, terminal or intercalary, monoblastic or usually polyblastic, mostly sympodially proliferating, more or less cylindrical, geniculate-sinuous or nodulose, sometimes with unilateral swellings; conidiogenous loci usually conspicuous, protuberant, composed of a central convex dome surrounded by a more or less raised periclinal rim (coronate), thickened, refractive or barely to distinctly darkened; conidial formation holoblastic. Conidia solitary or catenate, in unbranched or branched acropetal chains, amero- to phragmosporous, shape and septation variable, usually subglobose, ovoid, obovoid, ellipsoid, fusiform, limoniform to cylindrical, aseptate or with several transverse eusepta, rarely with a single longitudinal septum, subhyaline to usually pigmented, smooth, verruculose, verrucose, echinulate, cristate; hila protuberant, coronate, with a central convex dome and raised periclinal rim, thickened, refractive to darkened; microcyclic conidiogenesis often occurring. In vitro: Stromata usually lacking. Conidiophores usually solitary, arising terminally or laterally from plagiotropous or ascending hyphae, often longer than in vivo. Micronematous conidiophores, lacking in vivo, are often formed in culture. Conidial chains often longer than in vivo (species with solitary conidia are often capable of forming conidial chains in culture).

Culture characteristics: Colonies on SNA often grey olivaceous or olivaceous grey, reverse leaden-grey or black, flat, velvety with fluffy or cottony patches, margin irregular or undulate, aerial mycelium loose diffuse or more abundantly formed, often with abundant submerged mycelium.

Optimal media and cultivation conditions: For morphological examinations SNA incubated under continuous near-ultraviolet light at 25 °C proved to be best suited to promote sporulation. The sexual morph can be induced by inoculating plates of 2 % WA onto which autoclaved stem pieces of Urtica dioica (European stinging nettle) are placed. Inoculated plates have to be incubated on the laboratory bench for 1 wk, after that period they have to be further incubated at 10 °C in the dark for 1–2 mo to stimulate sexual morph development.

Distribution: Worldwide.

Hosts: Asparagaceae, Asteraceae, Fabaceae, Myrtaceae, Orchidaceae, Poaceae and many other hosts, including fungi and insects.

Disease symptoms: Leaf spots, leaf blight, discolourations, necrosis, or shot-hole symptoms, on stems and fruits, but also saprobic, endophytic or isolated from numerous substrates and environments, e.g. indoor environments, salterns and human and animal infections.

Notes: The monophyletic genus Cladosporium is well characterised by the coronate structure of its conidiogenous loci and conidial hila, consisting of a central convex dome surrounded by a raised periclinal rim (David, 1997, Braun et al., 2003). At the moment it comprises about 200 species. Cladosporium was previously extremely heterogeneous and encompassed 772 names assigned to this genus (Dugan et al. 2004). Heuchert et al. (2005) examined Cladosporium spp. dwelling on other fungi, and Schubert (2005) provided a comprehensive treatment of foliicolous species. Crous et al. (2007a) encompassed a series of papers dealing with a reassessment and new circumscription of Cladosporium s. str. and treatments of several cladosporioid genera. Bensch et al. (2012) published a taxonomic monograph of the genus Cladosporium which can be consulted for further information on the history and many other aspects of this genus.

Species delimitation in Cladosporium based on morphology alone is limited since many species have overlapping characters. Some key differential features have been identified and detailed in a series of monographic papers (Schubert et al., 2007, Zalar et al., 2007, Bensch et al., 2010, Bensch et al., 2012). The most relevant differential morphological traits are the shape, width and complexity of conidiophores, the presence of ramoconidia, and the formation and ornamentation of conidia. However, given the overlapping of these features, and the need for standardisation using special culture media and scanning electron microscopy procedures, the use of a molecular approach should be mandatory for correct identification of the species in this complex fungal group (Sandoval-Denis et al. 2016).

Three different species complexes are recognised within the genus, mainly based on morphology, and used for practical purposes. The Cl. cladosporioides species complex is characterised by mainly narrowly cylindrical or cylindrical-oblong, non-nodulose, mostly non-geniculate conidiophores and conidia with a quite variable surface ornamentation ranging from smooth to irregularly verrucose-rugose or rough-walled (reticulate or embossed stripes under SEM); the Cl. herbarum species complex includes species mainly having nodulose conidiophores, with conidiogenesis confined to swellings, and verruculose, verrucose or echinulate conidia; and the Cl. sphaerospermum complex is most remarkable due to forming numerous globose or subglobose terminal and intercalary conidia with variable surface ornamentation and often poorly differentiated conidiophores in most of the species (Bensch et al., 2012, Bensch et al., 2015). Morphologically similar genera have been treated in Crous et al. (2007b).

Members of Cladosporiaceae: Cladosporium, Graphiopsis, Neocladosporium, Rachicladosporium, Toxicocladosporium, Verrucocladosporium.

References: Braun et al. 2003 (sexual morph); Crous et al., 2007a, Crous et al., 2007b (cladosporium-like genera); Schubert et al. 2007 (morphology, phylogeny Cl. herbarum complex); Zalar et al. 2007 (morphology, phylogeny Cl. sphaerospermum complex); Bensch et al. 2010 (morphology, phylogeny Cl. cladosporioides complex); Bensch et al. 2012 (morphology, phylogeny and key of all Cladosporium species); Bensch et al. 2015 (morphology, additions to the three species complexes); Sandoval-Denis et al. 2016 (morphology, phylogeny of clinical samples).

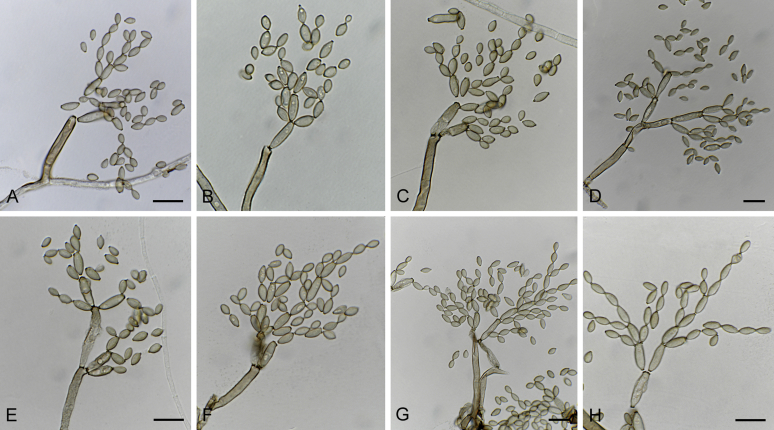

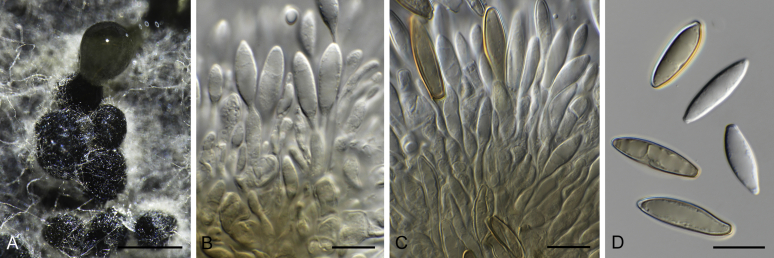

Cladosporium chasmanthicola Bensch, U. Braun & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB819978. Fig. 21.

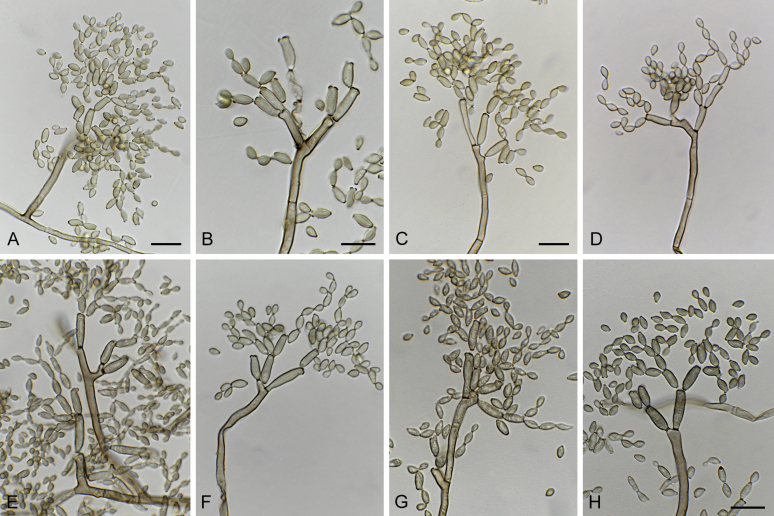

Fig. 21.

Cladosporium chasmanthicola (ex-type CBS 142612). A–H. Conidiophores and conidial chains. Scale bars = 10 μm; C applies to C–G.

Etymology: Epithet composed of the name of the host genus, Chasmanthe, and -cola, dweller.

Leaf spots solitary, distributed over leaf surface, amphigenous, ellipsoid, 1–2 mm diam, pale brown with dark red-brown margin, some spots also associated with uredinia of Uromyces kentaniensis. On SNA: Mycelium loosely branched, filiform, narrowly cylindrical-oblong or irregular in outline due to swellings and constrictions, 0.5–4 μm wide, septate, subhyaline or pale olivaceous or olivaceous brown, almost smooth, verruculose, distinctly verrucose or irregularly rough-walled. Conidiophores solitary, formed terminally or laterally from hyphae, straight or somewhat flexuous, macro- and micronematous; macronematous conidiophores cylindrical, sometimes geniculate, often irregular in outline due to lateral outgrowths, swellings and constrictions (not connected with conidiogenesis), mostly unbranched, 20–100(–140) × 3.5–5(–6) μm, up to 6 μm wide at the base, 1–6-septate, septa sometimes in short succession, not constricted at septa, pale olivaceous or pale to medium olivaceous brown, smooth, walls slightly thickened; micronematous conidiophores shorter, narrower and paler than macronematous ones, 15–30(–80) × 2–3 μm, 0–2-septate, subhyaline or pale olivaceous. Conidiogenous cells integrated, terminal and intercalary, 8–24 μm long, short cylindrical or often irregular in outline due to lateral prolongations and shoulders and numerous conidiogenous loci often crowded at or towards the apex, up to eight loci in terminal cells, 1–3 loci in intercalary cells, loci conspicuous, subdenticulate, 1–2 μm diam. Ramoconidia commonly formed, subcylindrical or irregular due to numerous loci at the distal end, 15–33 × 3–4.5 μm, 0–1(–3)-septate, base broadly truncate, 2.5(–3.5) μm wide. Conidia numerously formed, especially small terminal and intercalary conidia, in branched chains, branching in all directions with 1–3 conidia in the terminal unbranched part of the chain; terminal conidia very small, ovoid or obovoid, very pale, subhyaline or pale olivaceous brown, 2.5–4.5 × 2–2.5(–3) μm (av. ± SD: 3.4 ± 0.6 × 2.2 ± 0.3), apex rounded; intercalary conidia ovoid, limoniform, ellipsoid or irregular due to lateral outgrowths, 4–10.5 × (2–)3–3.5(–4) μm (av. ± SD: 7.2 ± 2.0 × 3.1 ± 0.5), aseptate, with 1–4 distal hila; secondary ramoconidia ellipsoid, subcylindrical or irregular in outline due to numerous hila crowded at or towards the distal end, sometimes located on lateral shoulders or lateral prolongations, those formed on micronematous conidiophores shorter and narrower, (5–)8–23 × (2.5–)3–4.5 μm (av. ± SD: 13.3 ± 5.4 × 3.5 ± 0.6), 0–1(–3)-septate, very pale olivaceous or pale olivaceous brown, smooth, walls unthickened, with (2–)3–6(–7) distal scars; hila conspicuous, 0.5–2 μm diam, darkened-refractive and somewhat thickened; conidia sometimes germinating.

Culture characteristics: Colonies on PDA reaching 28–35 mm diam after 2 wk, olivaceous grey, grey olivaceous with several smoke-grey patches of dense, felty aerial mycelium, reverse leaden-grey to olivaceous grey, powdery, margin white, broad, glabrous, colony centre somewhat folded and wrinkled, growth flat. Colonies on MEA attaining 29–35 mm diam, whitish, smoke-grey to pale olivaceous grey, reverse greyish sepia or olivaceous grey, velvety; margin glabrous, to somewhat feathery, radially furrowed, colony centre elevated, wrinkled and folded; aerial mycelium abundant, covering large parts of the colony surface, dense, fluffy. Colonies on OA reaching 20–28 mm diam, olivaceous grey with patches of smoke-grey, grey olivaceous or glaucous-grey towards margins, reverse leaden-grey to iron-grey, fluffy-felty; margin glabrous, undulate, colony centre somewhat elevated; aerial mycelium loose, diffuse to dense and fluffy in a few spots. On all media without prominent exudates, sporulation profuse.

Material examined: South Africa, Western Cape Province, Cape Town, Brackenfell, Bracken Nature Reserve, isol. from leaf spots on Chasmanthe aethiopica, 25 Sep. 2012, A.R. Wood (holotype CBS H-23117, culture ex-type CBS 142612 = CPC 21300).

Note: Cladosporium chasmanthicola is closely related to Cl. acalyphae, but the latter species has much longer and narrower conidiophores (150–430 × 3–4 μm) and smooth to loosely verruculose, irregularly verruculose-rugose or rough-walled conidia (Bensch et al. 2010).

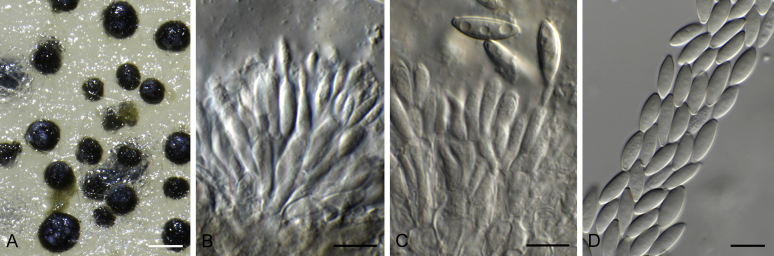

Cladosporium kenpeggii Bensch, U. Braun & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB819979. Fig. 22.

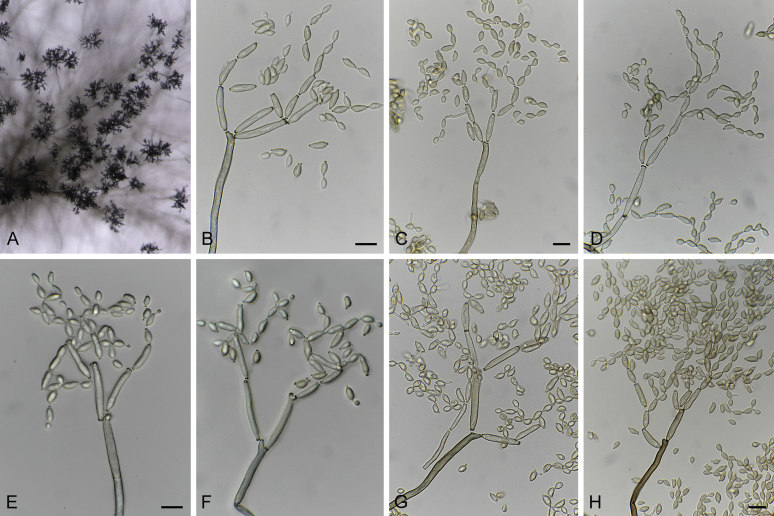

Fig. 22.

Cladosporium kenpeggii (ex-type CBS 142613). A. Part of the colony on SNA. B–H. Conidiophores and conidial chains. Note the microcyclic conidiogenesis in C, forming a secondary conidiophore at a still attached conidium with giving rise to secondary conidia and the germinating conidia in C and G. Scale bars = 10 μm; C applies to C, D; E applies to E–G.

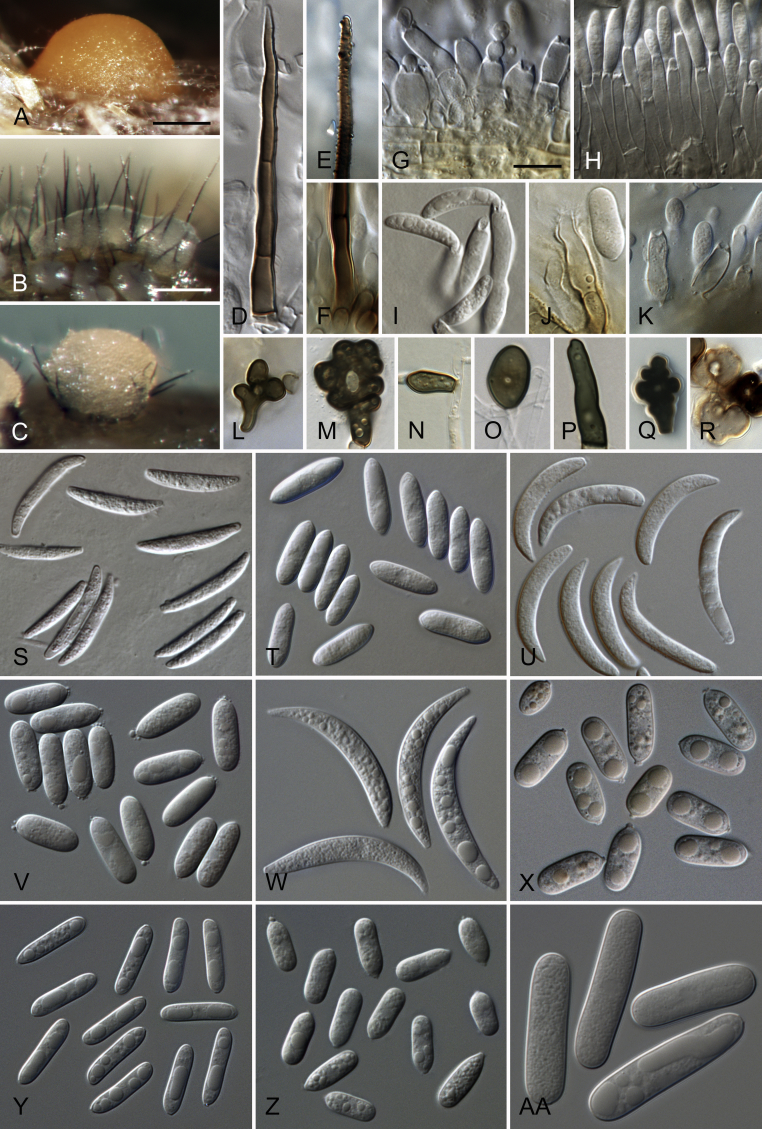

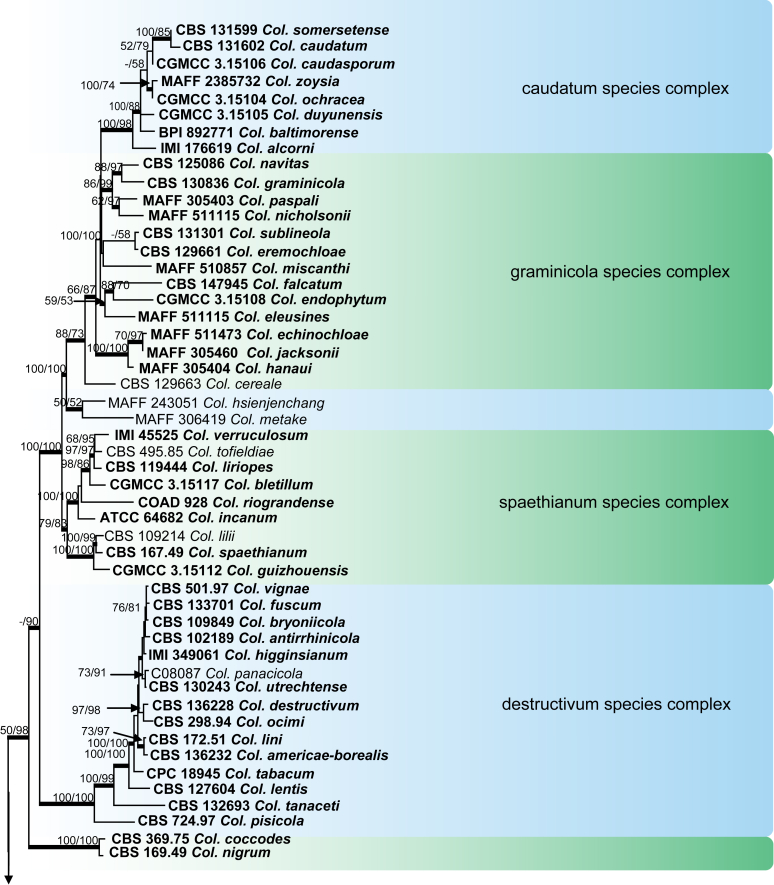

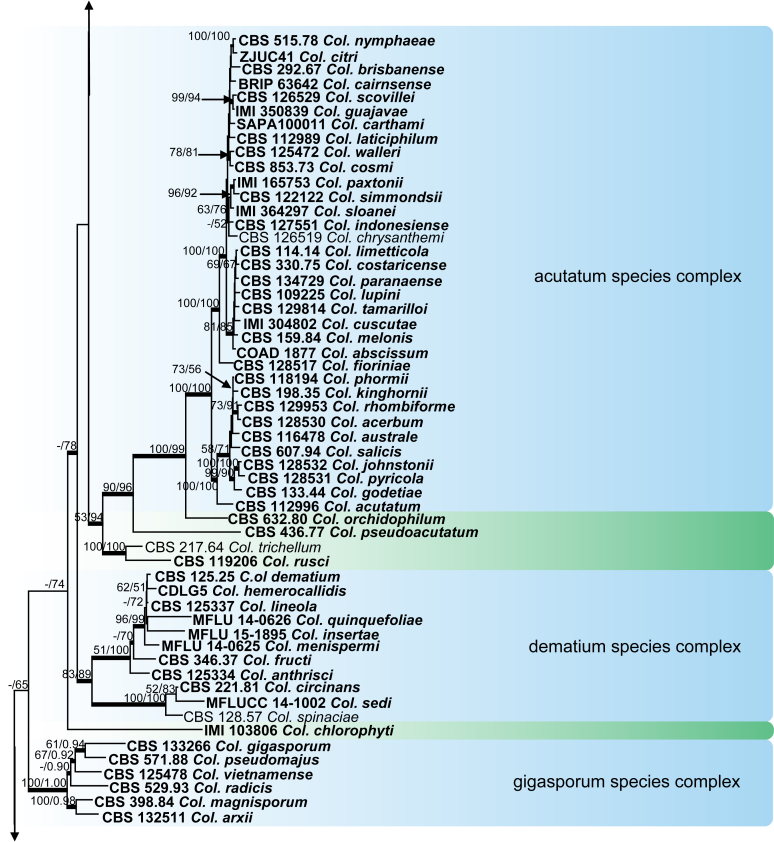

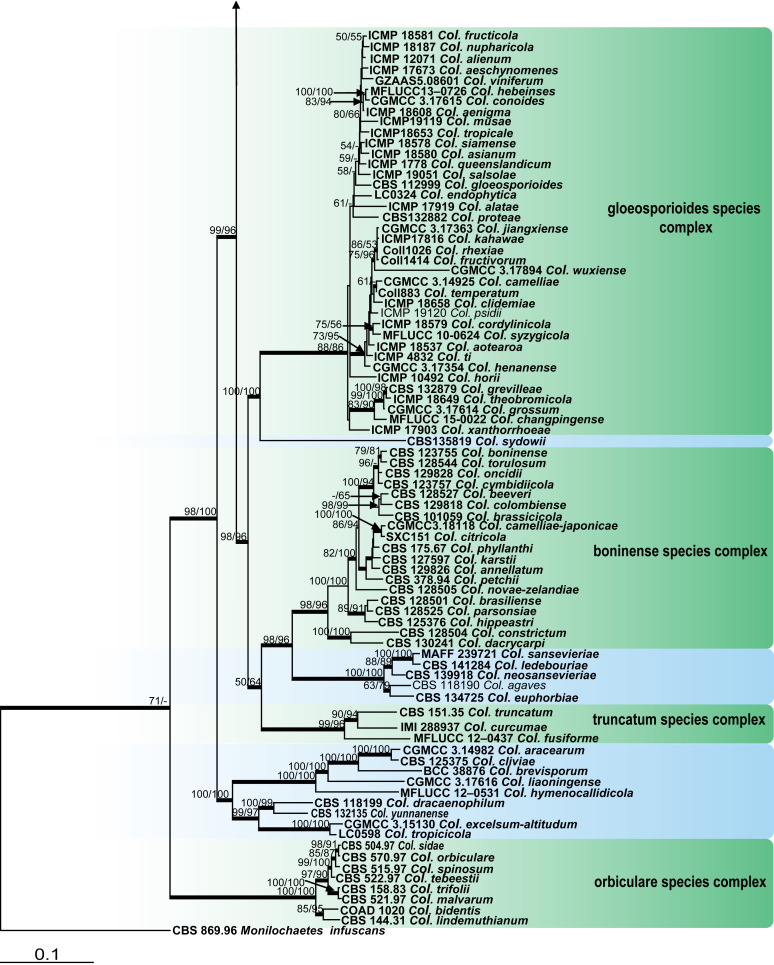

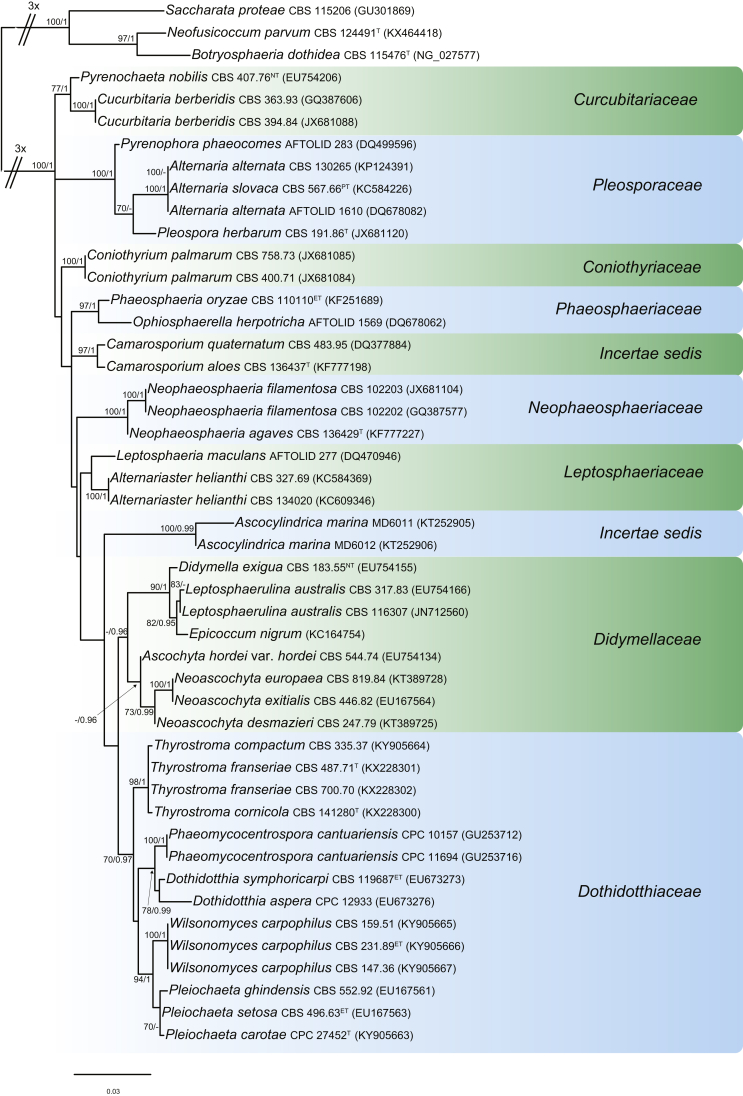

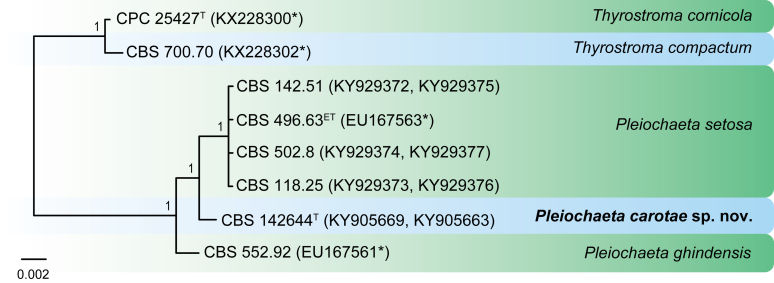

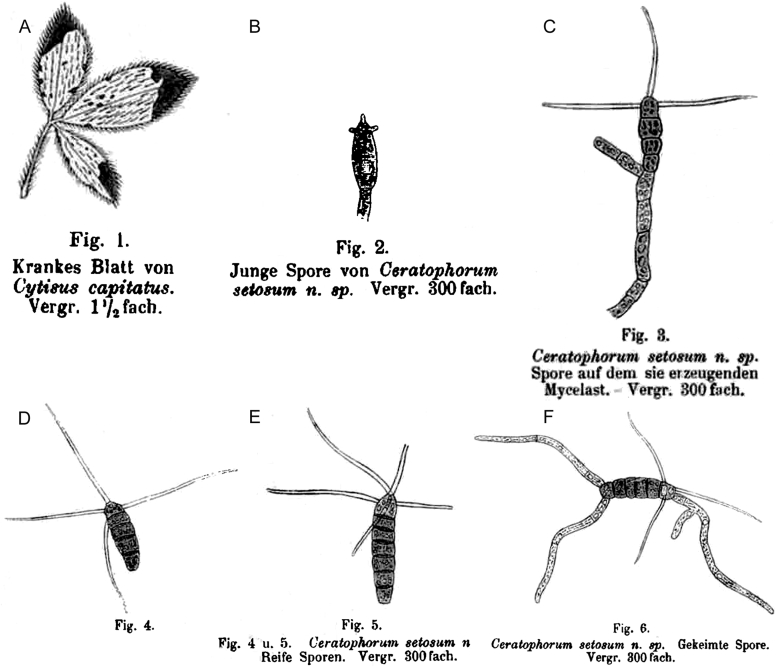

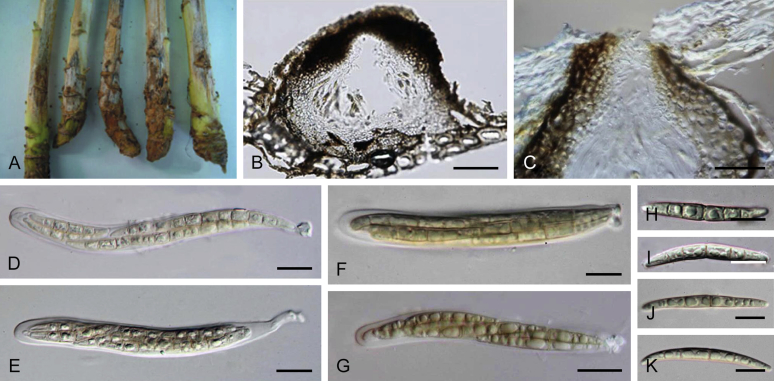

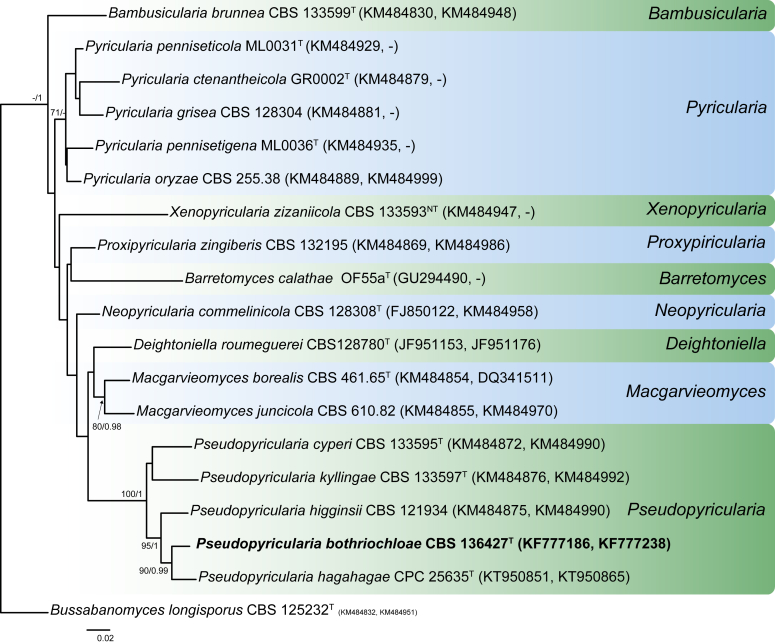

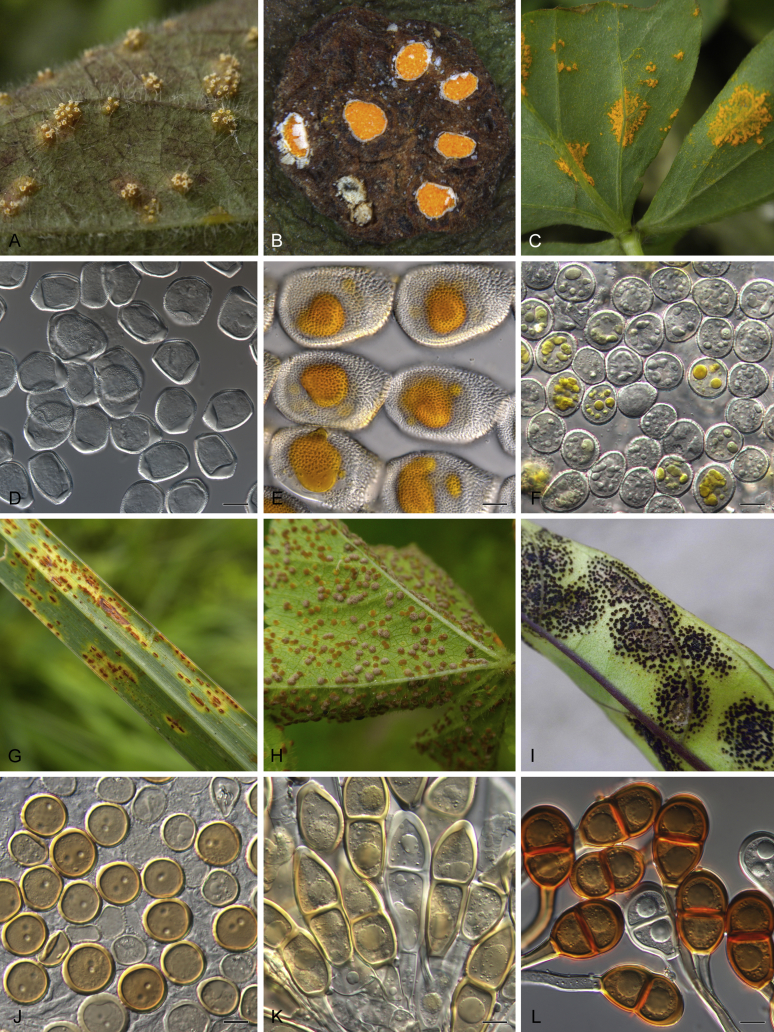

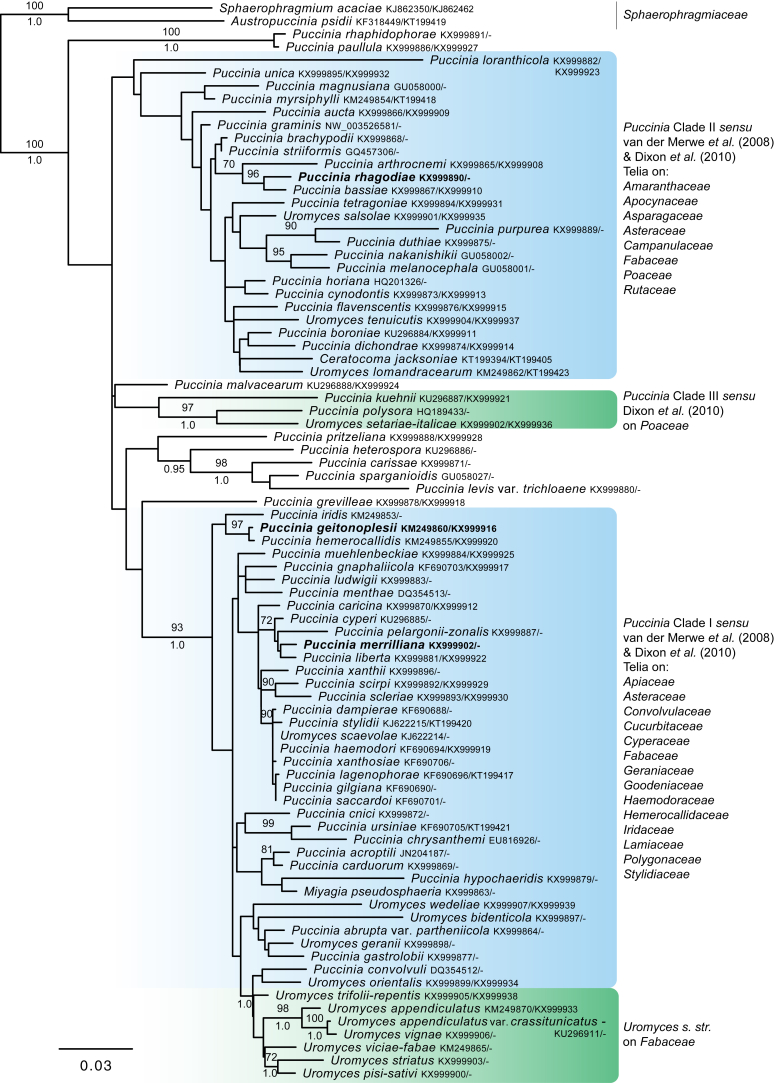

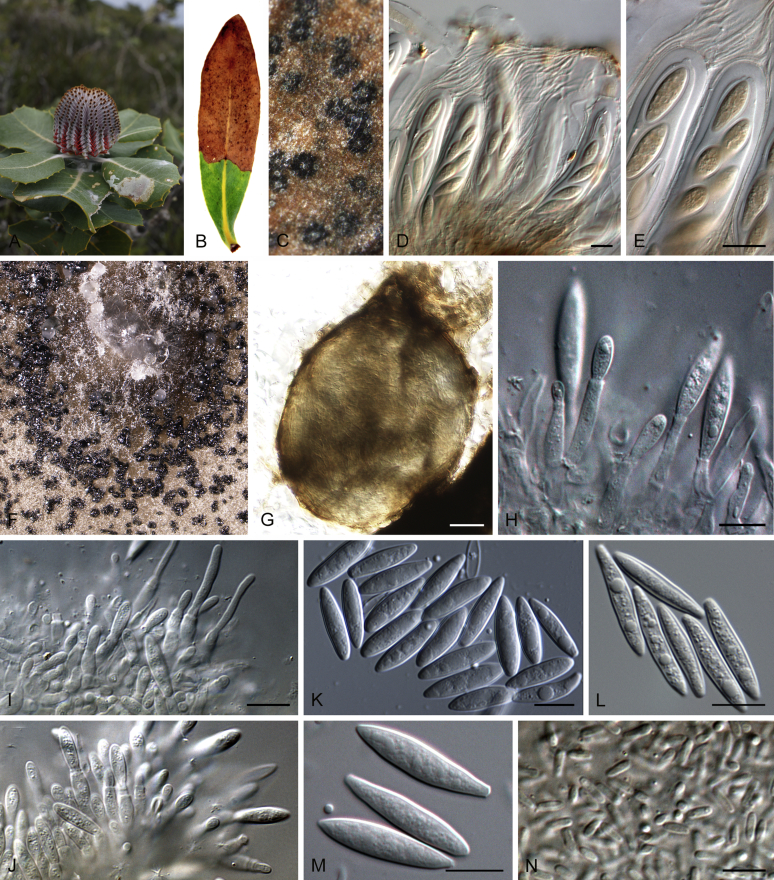

Etymology: Named after Dr Ken Pegg (Agri-Science and Biosecurity Queensland, Australia), the collector of the species, who celebrates his 80th birthday this year.