Abstract

Introduction: Losing items is a time-consuming occurrence in nursing homes that is ill described. An explorative study was conducted to investigate which items got lost by nursing home residents, and how this affects the residents and family caregivers. Method: Semi-structured interviews and card sorting tasks were conducted with 12 residents with early-stage dementia and 12 family caregivers. Thematic analysis was applied to the outcomes of the sessions. Results: The participants stated that numerous personal items and assistive devices get lost in the nursing home environment, which had various emotional, practical, and financial implications. Significant amounts of time are spent on trying to find items, varying from 1 hr up to a couple of weeks. Numerous potential solutions were identified by the interviewees. Discussion: Losing items often goes together with limitations to the participation of residents. Many family caregivers are reluctant to replace lost items, as these items may get lost again.

Keywords: nursing home, losing, lost, found, finding, technology, searching, personal items, personal belongings, hiding, hoarding, Alzheimer, dementia

Introduction

Everyone loses things once in a while, such as keys, one’s mobile phone, or a wallet. Despite the fact that losing items is an integral part of daily life, it is not studied in great detail. According to the British insurance company Esure Verzekeringsmaatschappij (2012), people spend about 10 min per day looking for lost items. In addition, people lose about nine items per day, which counts up to about 3,285 items per annum. “Losing” in this sense implies looking for lost items, such as keys, mobile phones, bank cards, and wallets. Other items that get lost on a regular basis are glasses, clothes, books, agendas, purses, gloves, umbrellas, laptops, tablets, and even cars. About three quarters of these items are found back inside the home, at the office, or inside the car. The most common causes for losing items are a hectic way of life, carelessness, or a bad memory (Esure Verzekeringsmaatschappij, 2012).

Looking for lost items is a time-consuming activity in the health care sector as well. Research in hospitals has shown that a care professional spends about 20 min on average per day looking for items (Repoint, 2016). It is expected that this duration is much higher in nursing homes, given the psychogeriatric population in many of the wards, and less well-supported logistics. Nursing home residents can lose items in their own apartment, or in other common rooms. They may also “hide” items in random places that seem illogical to others, for instance, when displaying a hoarding behavior or when having a sense of suspicion. Sometimes, items stored in waste containers may be disposed of permanently. In addition, nursing staff may lose items during their intensive care tasks, such as blood pressure meters, patient hoists, scales, and infusion pumps. The facility managers, when available, have little insight in the actual use of nursing home equipment. Some items may be used more frequently than others and may need maintenance checks more often. This more individualized approach to maintenance is not yet taken care of.

In the Netherlands, there are about 120,000 residents of nursing homes, and more than two thirds have a form of dementia. Memory loss is one of the symptoms in people with dementia syndrome, which can result in losing items. Another problem area is formed by behavioral problems, like hiding objects to keep these items safe. In other cases, people with dementia syndrome accuse others, including relatives, falsely of stealing items. In the private rooms of people residing in nursing homes, we see a large number of personal possessions that contribute to a sense of home (van Hoof et al., 2016), including pieces of furniture and small items such as picture frames. In addition, the rooms can be equipped with assistive technologies necessary for the provision of care. The chances of losing personal items may be limited by a number of care-related solutions. First of all, people should not be punished for losing or hiding items. It is important to find out what and where the favorite hiding place of a person with dementia is, to find back the lost items. Sometimes, having spare items can be a solution, including wallets, glasses, keys, and hearing aids. Giving possessions a fixed position in the home or room is another way of improving familiarity and structure.

An explorative field study was conducted to investigate which items get lost by nursing home residents, and how this affects the residents and family caregivers in an emotional, financial, or practical sense.

Method

A mixed methods research approach was applied for the study. Semi-structured interviews and card sorting tasks were conducted with the research participants, consisting of both residents with early-stage dementia and their family caregivers. The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme’s (CASP; 2013) checklist for qualitative research was used as a guide for this study.

Participants and Setting

The research population consisted of 12 residents with early-stage dementia and their family caregivers. The study population was 24 persons in total. The study was conducted in two nursing home organizations in Eindhoven in Schaijk in the Netherlands, in November 2015. At both locations, six sessions were done, consisting of joint interviews with both residents and family caregivers. Participants were recruited by the principal investigator (B.D.) in consultation with the professional caregivers of the two nursing home organizations that joined in the study. Prior to the study, potential participants received an information letter and documentation regarding the type of study. Informed consent was obtained from the participants in conjunction with their initial family caregivers by signing the given consent forms. The participants are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants of the Study and Their Characteristics.

| Resident | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (m/f) | f | f | f | f | f | f | m | f | f | f | m | f |

| Age (years) | 85 | 87 | 90 | 86 | 87 | 85 | 92 | 85 | 88 | 87 | 82 | 83 |

| Location (rural/urban) | Rural | Urban | Urban | Urban | Urban | Urban | Urban | Rural | Rural | Rural | Rural | Rural |

| Family caregiver | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L |

| Relationship to resident | Daughter | Daughter | Daughter | Daughter | Daughter-in-law | Spouse | Spouse | Daughter | Daughter | Daughter | Daughter | Daughter |

| Type of care | All tasksa | All tasks | All tasks | All tasks | All tasks | Visiting and doing activities together | Visiting and doing activities together | Financial tasks | All tasks | All tasks | All tasks | All tasks |

All tasks means doing laundry, taking care of financial and administrative tasks, making visits, doing groceries, assisting in hospital visits, and so forth.

Interviewing and Card Sorting and Data Analyses

The field study comprised 12 combined interviews and prioritization sessions with both residents and family caregivers. During the 45-min sessions, participants could assist each other in providing answers. Noteworthy is that persons with dementia may have a short attention span and have trouble staying focused during the interview. In this study, the use of two methods was a way of method triangulation.

A list of topics was used during the semi-structured interviews. This list consisted of items that related to losing objects, the emotions that followed upon losing these objects, the consequences of losing objects, and the solutions people came up with. Each interview started with general questions about living in a nursing home as an introduction to the questions relating to the goal of this study.

Card sorting is a method that allows participants to order topics (written on cards) in a logical order (Baxter, Courage, & Caine, 2015). It helps to structure topics or prioritize items. During a card sorting session, the researcher can also ask why certain choices are being made, and which associations are being made. In this study, card sorting was applied to rank the personal items that got lost most often by residents and the items that had the most value in terms of a financial, emotional, or practical perspective. To keep the options for the residents limited, the selection of items was maximized to a number of five to six items.

After the sessions, transcripts were made of the interviews and the outcomes of the card sorting assignment. Member check was applied for the data, as verbatim transcripts of the interviews were shared with the participants. The data of the interview sessions were analyzed through thematic analyses as described by Braun and Clarke (2006). This data analysis was conducted on the transcriptions of the sessions. The outcomes of the prioritization task were analyzed by making large matrices of the cards (vertical sorting) versus groups (horizontal sorting). Based on the procedure of ranking, a matrix was made of the personal items lost by residents.

Results

Losing Items in the Nursing Home

The participants stated that numerous items get lost in the nursing home environment. Examples of such items are clothes, handbags, keys, hearing aids, glasses, dentures, remote controls, and wheeled walkers (Table 2). All of these items are categorized in terms of the emotional, financial, and practical impact their loss has.

Table 2.

Overview of Lost Items and Items That Are Considered Essential by the Residents.

| Resident | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lost items | Glasses, remote control, wallet | Hearing aids, handbag | Clothes, entry ticket for ballet performance | Hearing aids, underwear, clothes, chairs | Jewelry, cigarettes (package), dentures | Jewelry, money, personal care items | Magazines, mirror, glasses, wheeled walker, clothes, needlework | Clothes, keys | Glasses, underwear | Clothes, underwear, dentures, photographs | Wallet, keys, clothes | Remote control, clothes, handbag, wallet, money, keys |

| Items which should not get lost according to clients and family caregivers | Glasses, hearing aids, wheeled walker, jewelry, figurines, photographs | Hearing aids, handbag, wallet, jewelry, glasses, wheeled walker, wedding pictures | Picture frames, jewelry, memorabilia, handbag, wallet, wheelchair | Necklace, chairs, wheeled walker | Glasses, wallet, handbag, jewelry, painting, clock, wheeled walker, pictures | Glasses, wheeled walker, hearing aids, dolls, jewelry, photographs | Necklace, neat pieces of clothing, glasses, ocular prosthesis, hearing aids, wheeled walker | Glasses, jewelry, handbag, wallet, keys | Glasses, jewelry, dentures | Wheeled walker, clothes, jewelry, keys, wallet, glasses, photographs | Wallet, keys, glasses, photo albums, wheeled walker, wheelchair, dentures | Glasses, jewelry, dentures, wallet, handbag |

| Emotional impact | Jewelry, figurines, photographs | Jewelry, wedding pictures | Entry ticket for ballet performance, memorabilia, jewelry | Chairs, necklace | Jewelry, painting, clock, photographs | Jewelry, dolls, photographs | Needlework | Jewelry | Jewelry | Jewelry, photographs | Picture albums | Jewelry |

| Practical impact | Glasses, hearing aids, wheeled walker, wallet, remote control | Hearing aids, handbag, wallet, glasses, wheeled walker | Handbag, wallet, wheelchair, clothes | Clothes, underwear, wheeled walker, hearing aids | Glasses, walker, wheeled walker, cigarettes | Glasses, hearing aids, wheeled walker, personal care items, money | Glasses, hearing aids, wheeled walker, clothes, mirror, ocular prosthesis | Glasses, handbag, wallet, keys, clothing | Glasses, dentures, underwear | Wheeled walker, clothing, underwear, keys, wallet, glasses | Glasses, wheeled walker, wheelchair, dentures, wallet, keys, clothes | Glasses, dentures, wallet, handbag, money, keys, remote control, clothes |

| Financial impact | Glasses, hearing aids | Glasses, hearing aids | — | Hearing aids | Dentures, glasses | Glasses, hearing aids | Glasses, hearing aids, ocular prosthesis | Glasses | Dentures, glasses | Dentures, glasses | Dentures, glasses | Dentures, glasses |

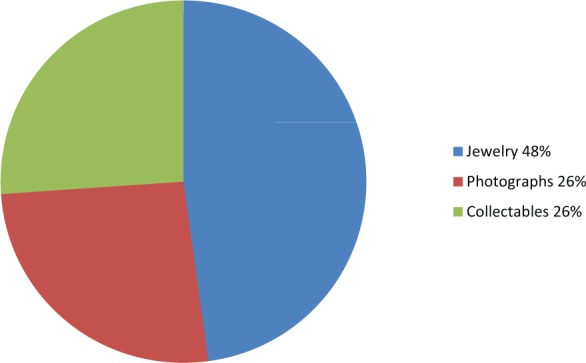

The items that have an emotional impact when lost are pieces of jewelry, collectables, and pictures of relatives (Figure 1). These items are mentioned by both residents and their family caregivers.

Figure 1.

Overview of items that have an emotional impact when lost.

Yes, things that I made during activity sessions. It was one of the first pieces of creative arts that I made. I put it up the wall and it is gone now. (Resident A)

It was a golden hanger. Well, she only wears a necklace now, but the golden cross is gone. (Relative E)

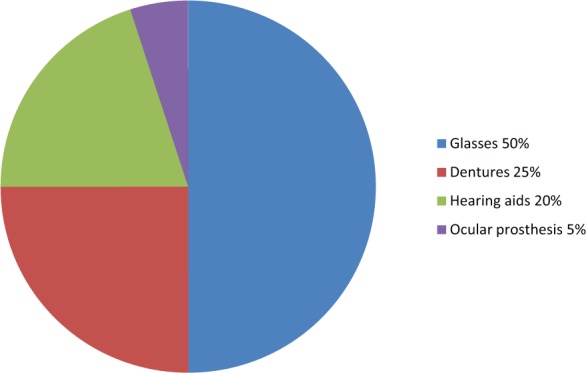

From a financial perspective (Figure 2), hearing aids, glasses, and dentures, and in one case, an ocular prosthesis, are costly to replace when lost. Apart from the financial implications that come with replacing such lost items, the residents cannot function properly without them. There are thus both financial and practical implications of losing these items. When someone loses a hearing device, he or she can no longer participate in activities or communicate properly, and function well in daily life. Replacing hearing aids, dentures, or glasses often comes at high costs, and some of the relatives indicated that they do not have sufficient financial means to purchase replacements. On top of that, some of the relatives stated that they do not purchase replacements as they fear that their loved-ones will lose the item again. Apart from the financial implications, relatives are faced with the logistics of replacement, for instance, visiting shops or having to consult a specialist (store). The process of acquiring replacements can take a considerable amount of time, sometimes as much as several days or weeks. When biophysical measurements have to be carried out to eyes or ears (glasses, hearing aids) or when molds have to be made (dentures), these measurements cannot always be conducted inside the nursing home. Residents have to travel with their relative to a specialized workshop. This can be a source of concern or behavioral symptoms.

Figure 2.

Overview of items that have a financial impact when lost.

Oh well, right in the beginning of my stay here, I lost my glasses. Well, we found them back again. It was right on top of a cabinet inside my room. I fear the day that I would lose my glass eye. (Resident A)

Well, yes, she lost her hearing aids. She hides them everywhere. Even in her purse. Even if we buy new ones, she will lose them soon after. (Relative B)

We applied for new hearing aids, and it was a total fiasco. Two days later they were gone again. (Relative D)

At a certain moment in time, I arrived in the morning, and the day before she had lost her dentures. We took action right away, and about a week later she had a replacement. (Relative E)

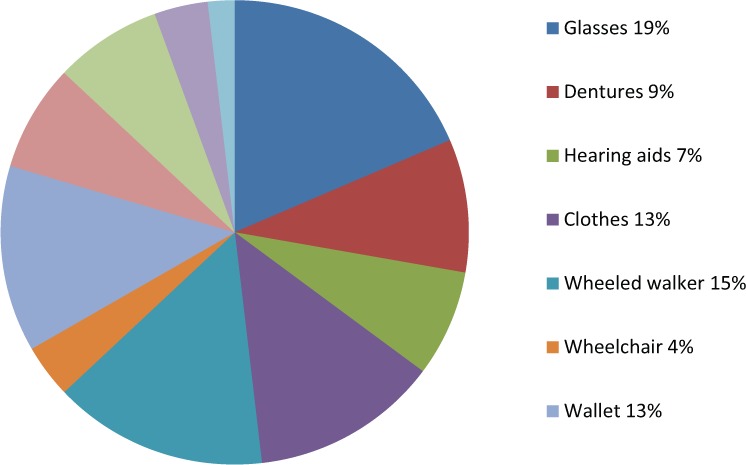

There are many items which have a practical implication when lost or missing (Figure 3). Among these items are wheeled walkers, glasses, dentures, wallets, handbags, remote controls, keys, and pieces of clothing. These items are essential for daily functioning and carrying out tasks. The number of items mentioned by the participants is larger than that for the emotional and financial categories.

Figure 3.

Overview of items that have a practical impact when lost.

Well, recently she lost her handbag. She puts a lot of items in her bag. He had put her bag inside a laundry basket, and it had been sent off to the laundry facility. Luckily, they found the handbag there, and sent it back to her. (Relative B)

He loses his wallet on a regular basis, and his keys too. (Relative K)

I never miss large pieces of clothing, except for the underwear, which I miss quite regularly. (Relative I)

For the potential causes of losing items, relatives indicated that it happens because their loved-ones hide items themselves, or because fellow residents take items away from their loved-ones’ rooms, or because of inattentiveness of the care professionals.

Well, there are bags over there; she puts a lot of stuff in them. (Relative L)

Well, these are the bags in which I put my stuff. Whenever I can go home again, I don’t have to pack all of my stuff at once. (Resident L)

Well, let’s say that people are laxer these days. I have nothing against the care staff, but when it happened, I just noticed that the staff were just lax and I feel bad about it. (Relative D)

Time Spent Searching for Items

Significant amounts of time are spent on trying to find items that went missing. Relatives indicated that the search duration varied from 1 hr up to a couple of weeks.

We have spent over 2 weeks looking everywhere. All closets were searched. In the end, I looked into the bag of the wheeled walker and I found them in there. (Relative D)

Well, quite a while. The remote control went missing a couple of times. And right now we have been looking for the remote control for a couple of weeks. And the bras, we found them some days ago, together with the panty hoses that had been gone for some days too. (Relative L)

Both residents and their family caregivers mentioned that they received help in trying to find their lost items. Residents often first looked for items themselves, but when they were not able to find them back independently, they usually went asking for help from relatives and professional caregivers.

The hair dresser was about to call a nursing aide to tell her that I had lost my wheeled walker. But I was sure I had brought it with me. A nursing aide took me back to my room, and went looking for the walker all over the place, but was not able to find it. And apparently they continued searching all through the night, because early in the morning, the wheeled walker was back in my room. (Resident A)

The staff thought I was busy working, because we did not even know the wheeled walker went missing. (Relative A)

In most cases, the nursing aides went looking for you, didn’t they? (Relative K)

Yes, and they were often able to find it again. (Resident K)

In other cases, residents were not aware that items went missing. Here, the relatives were the ones who found out that something was missing or had been lost.

I was about to pre-arrange clothing outfits, because my parents were about to celebrate their 50th wedding anniversary. I then noticed that the bras went missing. I went looking, and I found them in one of the bags that are over there. (Relative L)

Emotions Among Residents and Family Caregivers

Losing and looking for items has an emotional impact on residents and family caregivers. Residents tend to become restless or upset and angry when they find out that items have gone missing. They may even panic, or be upset for the rest of day or even for a period of several weeks when they cannot find a missing possession.

It made her very restless, because she missed her chairs. She was totally upset, and she could not be brought back to her senses. It stayed that way until the chairs were returned to her room. (Relative D)

Yes, and he gets a little nervous and a bit upset. The other week he was like that too. (Relative G)

Relatives mostly respond mildly or reluctantly when items have gone missing. They sometimes regret that items went missing but are more concerned about the emotions and responses of their loved-ones, for instance, restlessness. A response to such emotions is an extra attempt to find the lost items, and help provide consolation.

It is all replaceable. Just like this little mirror, it can all be replaced. (Relative A)

Well, I noticed my mother was restless. It was, after all, her handbag that went missing. I tried to calm her down, which sort of worked out. I just felt bad for her. More than just providing consolation is not possible. (Relative B)

A number of family caregivers become angry or frustrated when things get lost. It takes hours of searching before items are found, and too often, missing items are expensive, such as hearing aids and dentures. These are the relatives who consider stopping to replace missing items if they feel that replaced items will go missing short after. Health insurance companies will not reimburse the costs of lost glasses or hearing aids, especially if the costs have been claimed before. This is a great cause of frustration for relatives.

It made me feel grumpy. Searching all over the place, and not just once, but many times, because every time I think that I missed out on a spot. I took the sofa apart, removed the cushions, and I went looking in between the seams, and even in bed, and still I could not find the stuff. Then, I get really annoyed. (Relative E)

It made me angry. I understand that the staff cannot do much about it that people tamper with things, but then again, it is still about my mum and her stuff. The staff tried to help but at first I felt pissed off. (Relative J)

Solutions to Prevent Items From Getting Lost

Relatives have come up with a range of solutions to retrieve lost items, such as finding out what the main hiding places of their loved-ones were. In the case of a lost item, relatives went looking in these places first. If items were not found in these places, other places were searched. If items could not be found there either, replacements were bought.

I would think: She has put them somewhere and then forgot, for example, in the bathroom or bedroom. I often knew where to look for them, and usually found them. (Relative C)

Yes, we often buy it again. But for a while, I won’t buy a new wallet. We will probably find it again, won’t we, dad? (Relative K)

Two of the family caregivers have decided not to buy replacement items after losing the first, in this case, hearing aids.

Yes, she hides her stuff until she really loses it, such as her hearing aids. We can, of course, buy new ones, but she will lose those too. (Relative B)

The costs are simply too substantial. We already pay a monthly fee for care services. After replacing the hearing aids twice, we end up in financial problems. And, as we are certain that the moment we buy new ones, she will lose them again, then we consider not replacing them at all. (Relative D)

Some relatives have come up with solutions to prevent their loved-ones from losing things. The most frequently mentioned solutions are labeling garments, doing laundry oneself, taking away valuables from the room, putting a lock on the closets, and locking the doors of the private rooms. Another solution was creating awareness among professional caregivers to pay attention to personal belongings of the residents during care tasks.

If my mother misses a piece of clothing, I know for sure if it is the laundry basket. It is different from a laundry service taking care of dirty clothes. (Relative A)

She does not have many valuable possessions that other can take away from her. It is much safer this way. (Relative D)

Well, I told the nursing aides that when they go assist in showing, they need to remove the wallet from the trousers and put the wallet in the pocket of a second, clean pair of trousers. (Relative G)

We got you a key to lock the closet doors. There was already a lock on the door. (Relative H)

At a given moment in time, we put in sticky labels [on the clothes] on the ironing board. (Relative J)

Discussion and Conclusion

The interviews showed that many residents do no longer bring valuable items to the nursing home. Family caregivers choose to keep valuables, including jewelry, with relatives so that these items cannot go missing in the nursing home. One of the reasons indicated by family caregivers was that many residents walk around and enter a fellow resident’s room and take away goods. Theft was not mentioned by the participants as a cause of items getting lost. Moreover, family caregivers indicated that their own loved-ones displayed hoarding or hiding behaviors. This led to keeping certain belongings outside of the nursing home, most often with relatives. On the contrary, there were some residents who still kept valuable jewelry in the nursing home, and wore these items continuously, only taking bracelets and rings off during showering or during sleep. The family caregivers stated that they did not want to take everything away from their loved-ones, especially items which had a special or emotional meaning. Still, items do get lost, and no one seems to know what happened to these belongings. Staff can get accused of taking these missing items, even though the resident himself or herself may be the person responsible for losing the item, or for giving it away to someone else. Having lockers inside the nursing home or inside the private rooms may be a solution to this problem, and which may prevent relatives for taking the most valuable possessions.

The list of lost items reported by Esure Verzekeringsmaatschappij (2012) is a different list than the one found in this study. Among the items getting lost regularly in nursing homes by the residents are hearing aids, glasses, dentures, handbags, jewelry, wheeled walkers, clothing, wallets, and keys. The main reason for losing items is that residents no longer know that they actually lost items, and because of hoarding and hiding behavior. Staff not paying attention is mentioned as a reason for items getting lost.

The impact of losing items is twofold. Family caregivers indicated that they feel bad about losing items but that they feel more sorry for their loved-ones than for themselves. Many items do not have a financial value and can be replaced easily. Valuable items such as glasses, dentures, and hearing aids are a cause of greater concern, both financially and practically. Residents need these items to function properly in daily life. When such items get lost, it is considered whether replacement is worth the investment, as replaced items may get lost again on the short term. Some family caregivers lack financial resources to replace these items, and hope that the lost items are found again. Residents worry most about jewelry, mainly from an emotional point of view, often as a memory of someone dear to them, for instance, wedding rings. From a practical perspective, persons with dementia can be very attached to their personal belongings. Handbags and wallets can have a special meaning and are being carried all of the time. A handbag may strengthen the feeling of self-worth and provide structure for female nursing home residents. Losing these items may be a cause of problematic behavior, such as restlessness. As mentioned before, some items have a high financial value, such as glasses, hearing aids, and dentures. Most residents are not at all aware of the value of these items. When they lose these items, it is the family caregivers who have to take care of replacements, both procedurally and financially. This study showed a shift from financial toward emotional concerns when losing items. During the interviews, it was mentioned that not too many valuable items were taken to the nursing home. Relatives chose to safeguard these items in their own homes on behalf of their parent, as there were no facilities to keep the valuables safe inside the nursing home, such as safes and vaults. There were objections to keeping these valuables away from a loved-one, as these belongings often have a sentimental value and in principle still belong to a parent, not to a child. The coping strategies seen in family caregivers can be quite rigid from the perspective of a layman, ranging from the aforementioned nonreplacement of lost items to keeping items at their own home. In the case of residents with dementia, the people do not only “break down inside,” but their exterior appearance may also crumble due to losing personal items which provide these people with an identity.

This study showed that the items most often mentioned by residents and family caregivers concern personal items, which are small and get lost easily. Care technologies, apart from hearing aids, wheelchairs, and wheeled walkers, are not mentioned by these two groups of stakeholders. Here, there may be a difference with care professionals, who may lose larger items that they need for carrying out their professional tasks. This could be a step in future research, namely, the investigation of items that get lost by nursing aides and how much time they spend on finding these lost items back. This would provide a full image of the scale and type of problem of losing items in the nursing home.

The answers given in this study have an emphasis on personal items. There are a number of solutions that can be implemented to support nursing home residents. Some of them are low-tech interventions, which include putting items in a fixed place or position, which enables people to quickly find items. Routines seem to be an important day-to-day solution. Searching in places often used for storage, including laundry baskets, is another solution. Labeling of pieces of clothing is a strategy that can be applied, as well as labeling items (van Hoof, Kort, van Waarde, & Blom, 2010). When items are being sent off to a laundry station, pieces of garment should ideally be checked by care professionals if pockets are all empty. During an intake when someone is being admitted, it might be valuable to ask where soon-to-be residents kept their items at home, for instance, if glasses were kept near a sofa, if hearing aids were placed next to bed, and if a wheeled walker was always parked near the coatrack.

Next to organizational solutions, there are technological solutions to this problem that can be used in the present day and in the near future (van Hoof et al., 2014). So-called real-time location systems (RTLSs) are systems that are able to track the locations of tagged items indoors, via wireless sensor networks (Malik, 2009). These systems are often based on radio frequency identification (RFID) and quite commonly deployed in the hospital context. Within the hospital, these systems are used to track patients and staff as well as assets, such as IV pumps and wheeled walkers (Fisher & Monahan, 2012; Kamel Boulos & Berry, 2012). These assets are tagged and traceable via a computer. Most commercially available tags are still quite large. However, tag size is decreasing. Madrid, Korsvold, Rochat, and Abarca (2012) presented a study in which small RFID tags are placed in dentures for 6 months. After this time, the tags were still readable. With such a system, tagged items in nursing homes can be tracked 24/7. A high-tech approach like this would enable nursing aides to quickly find lost items back, personal items of residents as well as nursing home assets. Facility managers would have a tool to see how often items are used, and have benefits related to maintenance, repair, and inventory. There would, however, be a set of ethical and privacy-related dilemmas, as tracking items that are often carried around by a person also reveals a personal pattern of movement (Al Ameen, Liu, & Kwak, 2012).

Finally, it is important that family caregivers are always notified when items are lost. It is a first step in trying to find the lost items back, as relatives may assist professional caregivers in search actions, or take care of replacing lost items. This prevents a resident from being without an assistive device for too long, which may have negative impact to one’s quality of life.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants of the sessions at BrabantZorg and Vitalis WoonZorg Groep for their willingness to volunteer and share their views.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: The RAAK (Regional Attention and Action for Knowledge Circulation) aims to improve knowledge exchange between subject matter experts (SMEs) and Universities of Applied Sciences in the Netherlands. Stichting Innovatie Alliantie (SIA)-RAAK had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The RAAK (Regional Attention and Action for Knowledge Circulation) scheme, which is managed by the Foundation Innovation Alliance (Stichting Innovatie Alliantie [SIA]) with funding from the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (OCW), is thanked for their financial support (SIA Project Number 2015-02-24M, Project SCHAT—Smart Care Homes and Assistive Technologies).

References

- Al Ameen M., Liu J., Kwak K. (2012). Security and privacy issues in wireless sensor networks for healthcare applications. Journal of Medical Systems, 36, 93-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter K., Courage C., Caine K. (2015). Chapter 11: Card sorting. In Understanding your users: A practical guide to user research methods (2nd ed., pp. 302-337). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101. [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). (2013).Qualitative Research Checklist 31.05.13 Oxford, UK. Retrieved from http://media.wix.com/ugd/dded87_29c5b002d99342f788c6ac670e49f274.pdf

- Esure Verzekeringsmaatschappij. (2012). We zoeken ons 10 minuten per dag suf [We are looking for our stuff 10 minutes per day]. Retrieved from http://www.ad.nl/ad/nl/1003/You/article/detail/3229521/2012/03/22/We-zoeken-ons-per-dag-10-minuten-suf.dhtml

- Fisher J. A., Monahan T. (2012). Evaluation of real-time location systems in their hospital contexts. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 81, 705-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamel Boulos M. N., Berry G. (2012). Real-time locating systems (RTLS) in healthcare: A condensed primer. International Journal of Health Geographics, 11, Article 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madrid C., Korsvold T., Rochat A., Abarca M. (2012). Radio frequency identification (RFID) of dentures in long-term care facilities. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry, 107, 199-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik A. (2009). RTLS for dummies. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Repoint. (2016). Available from http://www.repoint.nl/

- van Hoof J., Janssen M. L., Heesakkers C. M. C., van Kersbergen W., Severijns L. E. J., Willems L. A. G., . . . Nieboer M. E. (2016). The importance of personal possessions for the development of a sense of home of nursing home residents. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 30, 35-51. [Google Scholar]

- van Hoof J., Kort H. S. M., van Waarde H., Blom M. M. (2010). Environmental interventions and the design of homes for older adults with dementia: An overview. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias, 25, 202-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hoof J., Wetzels M. H., Dooremalen A. M. C., Wouters E. J. M., Nieboer M. E., Sponselee A. A. M., . . . Overdiep R. A. (2014). Technological and architectural solutions for Dutch nursing homes: Results of a multidisciplinary mind mapping session with professional stakeholders. Technology in Society, 36, 1-12. [Google Scholar]