Abstract

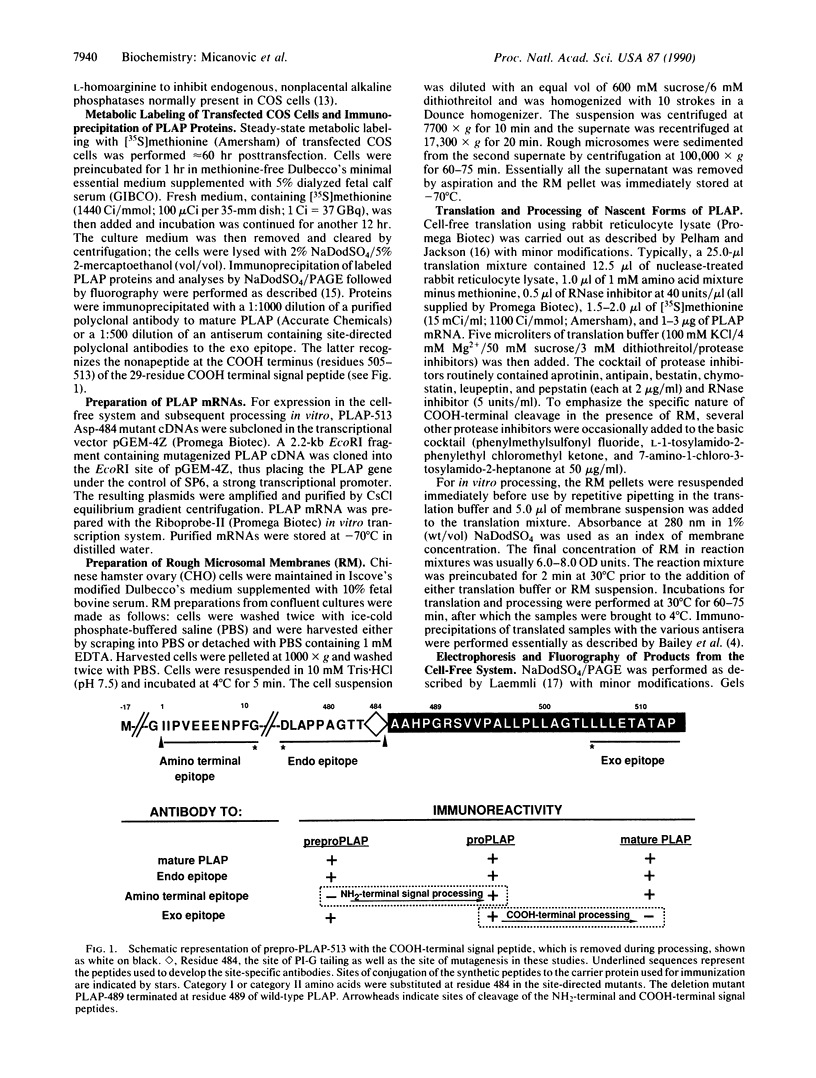

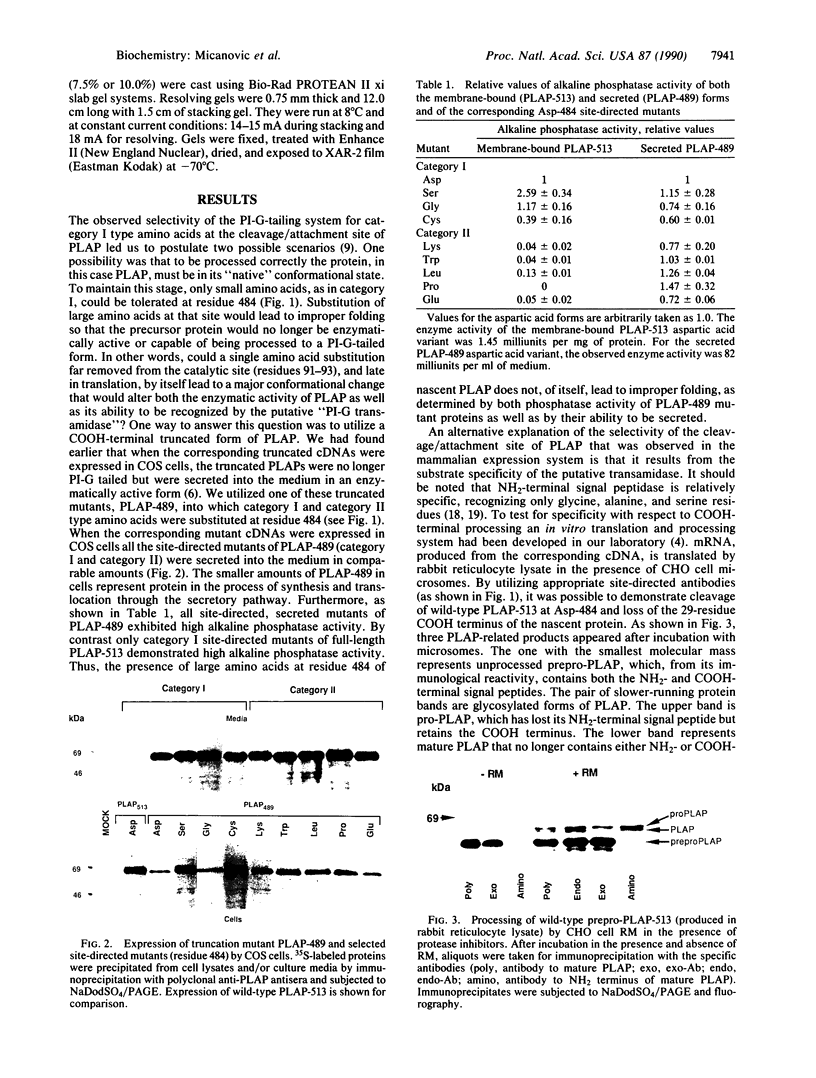

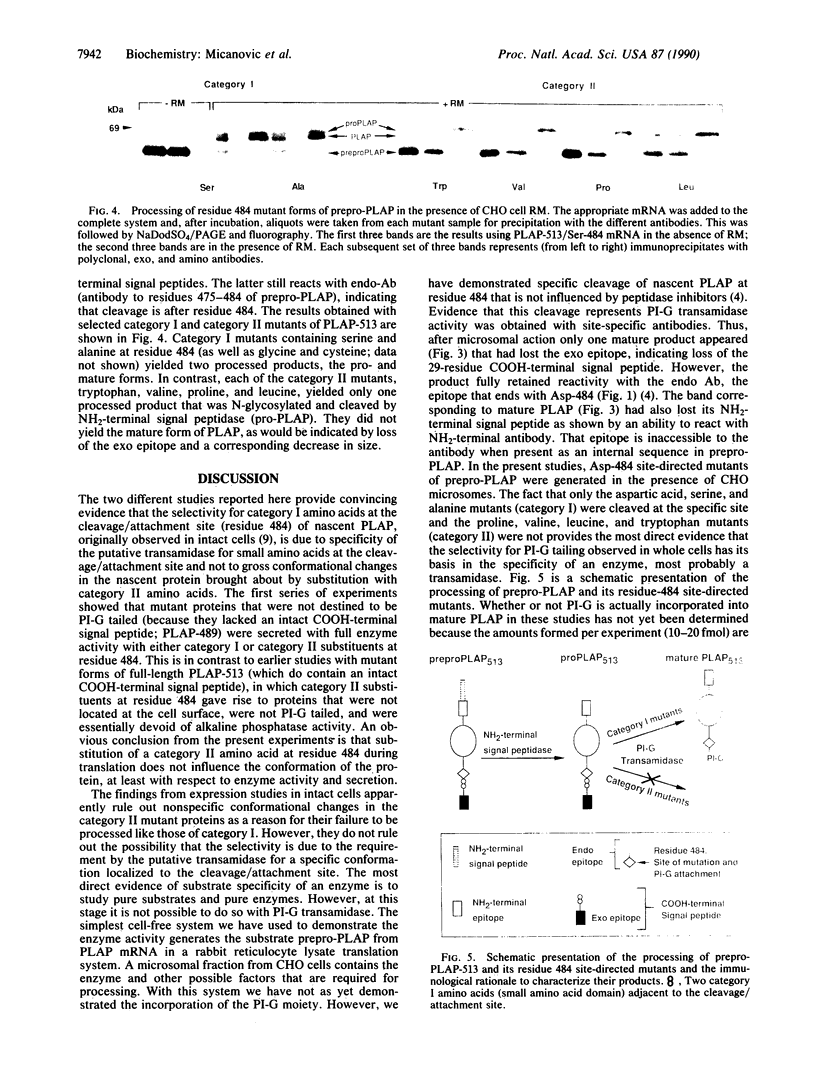

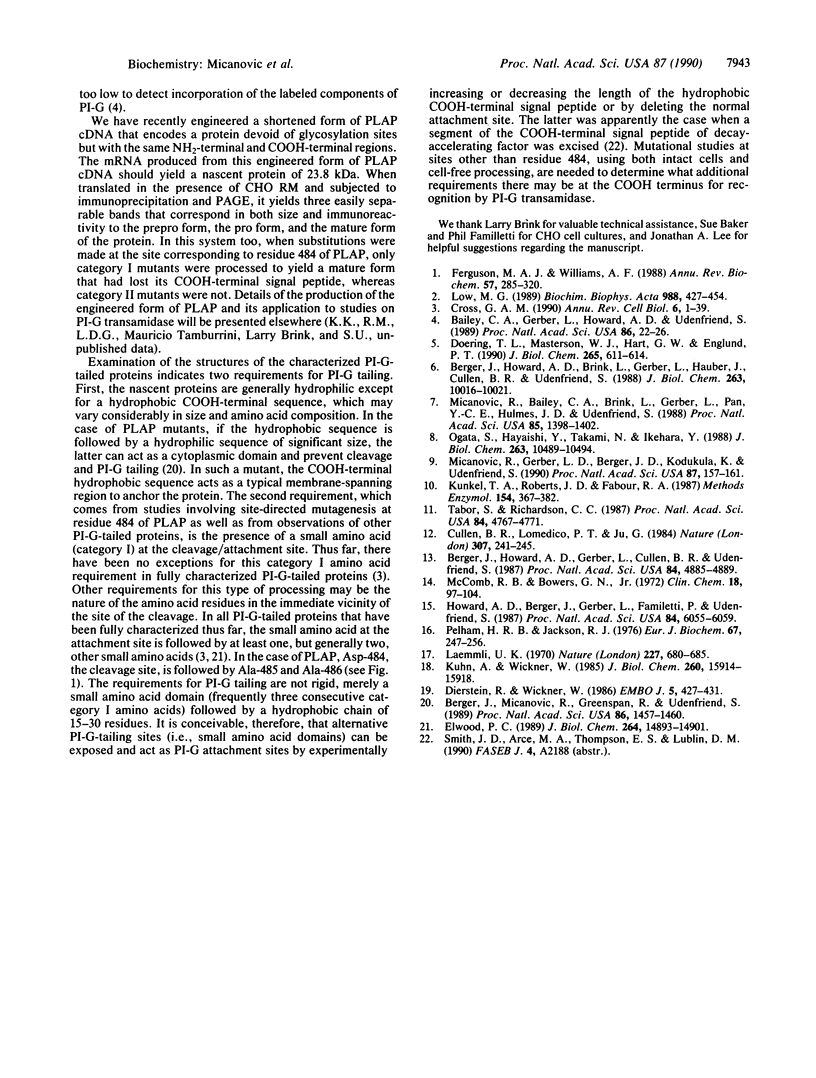

Nascent precursors of phosphatidylinositol-glycan (PI-G)-linked membrane proteins contain a hydrophobic COOH-terminal sequence of 15-30 residues that is eliminated during processing to yield a newly exposed COOH terminus to which the PI-G moiety is added. There is no consensus as to the primary structure of the terminal peptide but there is a specific requirement for the amino acid destined to become the COOH terminus. In nascent human placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP), the PI-G tail is attached to Asp-484. Site-directed mutants with glycine, alanine, cysteine, serine, or asparagine (category I) at residue 484 become PI-G tailed, appear in the plasma membrane, and are enzymatically active when expressed in COS cells. Although mutants with glutamic acid, glutamine, proline, tryptophan, leucine, valine, phenylalanine, threonine, methionine, and tyrosine (category II) are expressed equally well, only small amounts appear on the plasma membrane. Furthermore, they are not PI-G tailed and have little alkaline phosphatase activity. Studies with truncated PLAP-489 rule out nonspecific conformational changes in category II mutant proteins as a reason for their failure to be processed in COS cells and point to a specific COOH-terminal processing enzyme. Direct evidence that the selectivity for category I amino acids is enzymatically determined was obtained in a cell-free translation/processing system by using rabbit reticulocyte lysate and CHO cell rough microsomal membranes. In this in vitro system, both category I and category II mutants of PLAP-513 were translated, glycosylated, and cleaved by NH2-terminal signal peptidase. However, an additional and selective cleavage at residue 484 was observed only with category I mutants.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bailey C. A., Gerber L., Howard A. D., Udenfriend S. Processing at the carboxyl terminus of nascent placental alkaline phosphatase in a cell-free system: evidence for specific cleavage of a signal peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Jan;86(1):22–26. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger J., Howard A. D., Brink L., Gerber L., Hauber J., Cullen B. R., Udenfriend S. COOH-terminal requirements for the correct processing of a phosphatidylinositol-glycan anchored membrane protein. J Biol Chem. 1988 Jul 15;263(20):10016–10021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger J., Howard A. D., Gerber L., Cullen B. R., Udenfriend S. Expression of active, membrane-bound human placental alkaline phosphatase by transfected simian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Jul;84(14):4885–4889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.14.4885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger J., Micanovic R., Greenspan R. J., Udenfriend S. Conversion of placental alkaline phosphatase from a phosphatidylinositol-glycan-anchored protein to an integral transmembrane protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Mar;86(5):1457–1460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.5.1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross G. A. Glycolipid anchoring of plasma membrane proteins. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1990;6:1–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.06.110190.000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen B. R., Lomedico P. T., Ju G. Transcriptional interference in avian retroviruses--implications for the promoter insertion model of leukaemogenesis. Nature. 1984 Jan 19;307(5948):241–245. doi: 10.1038/307241a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierstein R., Wickner W. Requirements for substrate recognition by bacterial leader peptidase. EMBO J. 1986 Feb;5(2):427–431. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04228.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doering T. L., Masterson W. J., Hart G. W., Englund P. T. Biosynthesis of glycosyl phosphatidylinositol membrane anchors. J Biol Chem. 1990 Jan 15;265(2):611–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwood P. C. Molecular cloning and characterization of the human folate-binding protein cDNA from placenta and malignant tissue culture (KB) cells. J Biol Chem. 1989 Sep 5;264(25):14893–14901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson M. A., Williams A. F. Cell-surface anchoring of proteins via glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol structures. Annu Rev Biochem. 1988;57:285–320. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.001441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard A. D., Berger J., Gerber L., Familletti P., Udenfriend S. Characterization of the phosphatidylinositol-glycan membrane anchor of human placental alkaline phosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Sep;84(17):6055–6059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.17.6055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn A., Wickner W. Conserved residues of the leader peptide are essential for cleavage by leader peptidase. J Biol Chem. 1985 Dec 15;260(29):15914–15918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel T. A., Roberts J. D., Zakour R. A. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Methods Enzymol. 1987;154:367–382. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)54085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low M. G. The glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol anchor of membrane proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989 Dec 6;988(3):427–454. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(89)90014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McComb R. B., Bowers G. N., Jr Study of optimum buffer conditions for measuring alkaline phosphatase activity in human serum. Clin Chem. 1972 Feb;18(2):97–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micanovic R., Bailey C. A., Brink L., Gerber L., Pan Y. C., Hulmes J. D., Udenfriend S. Aspartic acid-484 of nascent placental alkaline phosphatase condenses with a phosphatidylinositol glycan to become the carboxyl terminus of the mature enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Mar;85(5):1398–1402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.5.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micanovic R., Gerber L. D., Berger J., Kodukula K., Udenfriend S. Selectivity of the cleavage/attachment site of phosphatidylinositol-glycan-anchored membrane proteins determined by site-specific mutagenesis at Asp-484 of placental alkaline phosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Jan;87(1):157–161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata S., Hayashi Y., Takami N., Ikehara Y. Chemical characterization of the membrane-anchoring domain of human placental alkaline phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 1988 Jul 25;263(21):10489–10494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham H. R., Jackson R. J. An efficient mRNA-dependent translation system from reticulocyte lysates. Eur J Biochem. 1976 Aug 1;67(1):247–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1976.tb10656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabor S., Richardson C. C. DNA sequence analysis with a modified bacteriophage T7 DNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Jul;84(14):4767–4771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.14.4767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]