Abstract

Bifidobacteria are one of the major components in human microbiota that are suggested to function in maintaining human health. The colonization and cell number of Bifidobacterium species in human intestine vary with ageing. However, sequential changes of Bifidobacterium species ranging from newborns to centenarians remain unresolved. Here, we investigated the gut compositional changes of Bifidobacterium species over a wide range of ages. Faecal samples of 441 healthy Japanese subjects between the ages of 0 and 104 years were analysed using real-time PCR with species-specific primers. B. longum group was widely detected from newborns to centenarians, with the highest detection rate. B. breve was detected in approximately 70% of children under 3 years old. B. adolescentis and B. catenulatum groups were predominant after weaning. B. bifidum was detected at almost all ages. The detection rate of B. dentium was higher in the elderly than in other ages. B. animalis ssp. lactis was detected in 11.4% of the subjects and their ages were restricted. B. gallinarum goup was detected in only nine subjects, while B. minimum and B. mongoliense were undetected at any age. The presence of certain Bifidobacterium groups was associated with significantly higher numbers of other Bifidobacterium species/subspecies. Inter-species correlations were found among each species, exception for B. animalis ssp. lactis. These results revealed the patterns and transition points with respect to compositional changes of Bifidobacterium species that occur with ageing, and the findings indicate that there may be symbiotic associations between some of these species in the gut microbiota.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00284-017-1272-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Introduction

Members of the genus Bifidobacterium naturally inhabit human gastrointestinal tract (GIT), and are thought to play pivotal roles in maintaining human health [4, 12]. Bifidobacterium is the most predominant genus of the breast-fed infant gut microbiota. However, the numbers of this genus substantially decrease after weaning and continue to decrease with age [33, 40, 44]. In addition, bifidobacterial composition at species level was reported to vary between life stages. To date, approximately ten species/subspecies Bifidobacterium have been found in human intestine. Previous reports have shown that Bifidobacterium breve and B. longum are the predominant species of the infant intestinal microbiota [2, 16]. Avershina et al. [1] evidently demonstrated that a switch occurs from a childhood- to an adult-associated microbial profile between one and two years of age. They further suggested that this change was driven by the keystone of B. breve strains. Bifidobacterium breve was highly prevalent in infant gut microbiota population during the first year of life, and showed negative correlation with B. longum in the adult population.

In contrast to the infant gut, the adult gut microbiota is predominated by B. adolescentis and B. catenulatum groups, in addition to the infant-associated B. longum ssp. longum [1, 8, 15]. These adult-type predominant Bifidobacterium species persisted in elderly, with an increase in the prevalence of B. dentium species [8, 21, 28]. Recently, Wang et al. [39] revealed that the faecal Bifidobacterium species in centenarians of Chinese descent were different from those of young elderlies. Despite the common faecal Bifidobacterium species, including B. dentium, B. longum ssp. longum, B. thermophilum, members of the B. catenulatum group, and B. adolescentis in younger elderlies and centenarians, centenarians were reported to possess certain unique species, such as B. minimum, B. gallinarum/B. pullorum/B. saecularmay and B. mongoliense, which were absent in the younger elderlies [39].

Although some studies have compared the Bifidobacterium species present in healthy adults to those in infants and/or elderly individuals [8, 10, 41], no reports have examined the sequential changes that occur in Bifidobacterium species during life spans ranging from newborns to centenarians.

The aim of this study was to improve the current understanding of the compositional changes of Bifidobacterium species along with ageing. Here, we investigated the sequential changes that occur in the composition of Bifidobacterium species in 441 healthy Japanese subjects over a wide age range, including individuals from 0 to 104 years old.

Materials and Methods

Subject

Four hundred forty-six faecal samples were collected from 441 community-dwelling Japanese volunteers (essentially one sample per time point per subject, except for two samples that were collected from two boys and one from one girl at only pre-weaning and weaning and three samples from one girl at pre-weaning, weaning and 5 years old) between 0 and 104 years of age (180 men, 261 women). Subjects aged over 80 years were recruited and confirmed to be community dwellers. Faecal samples were collected from subjects who participated in three different studies. Two study protocols [25, 26] included the collection of faeces from subjects aged 21 to 65 years or from community-dwelling elderly individuals, were approved by the Local Ethics Committee of the non-profit organization Japan Health Promotion Supporting Network (Wakayama, Japan). The third study protocol [25] including the collection of faeces from subjects aged 0 to 100 years old was approved by the ethical committee of the Kensyou-kai Incorporated Medical Institution (Osaka, Japan). Written and informed consent was obtained from all subjects or their legal guardians or relatives. The subjects were divided into 10-year age groups according to their age, except for subjects who were younger than 10 years old. Infants and children were divided into four groups: pre-weaning, weaning, weaned to 3 years old and 4–9 years old. The distribution of subjects according to age is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample distribution

| Group | Age | Number of samples | (Male/female) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Segmentation | (Mean ± SD) | |||

| 1 | Pre-weaning | (0.3 ± 0.1) | 16 | (9/7) |

| 2 | Weaning | (0.8 ± 0.4) | 12 | (7/5) |

| 3 | Weaned-3 years old | (2.4 ± 0.6) | 21 | (10/11) |

| 4 | 4–9 years old | (5.9 ± 1.8) | 17 | (7/10) |

| 10 | 10–19 years old | (14.1 ± 3.6) | 10 | (7/3) |

| 20 | 20–29 years old | (25.8 ± 2.7) | 42 | (16/26) |

| 30 | 30–39 years old | (34.3 ± 2.5) | 114 | (54/60) |

| 40 | 40–49 years old | (43.7 ± 3.1) | 37 | (13/24) |

| 50 | 50–59 years old | (53.5 ± 2.7) | 29 | (13/16) |

| 60 | 60-69 years old | (64.2 ± 2.9) | 42 | (14/28) |

| 70 | 70–79 years old | (75.5 ± 2.9) | 31 | (12/19) |

| 80 | 80–89 years old | (83.2 ± 2.4) | 51 | (17/34) |

| 90 | 90–99 years old | (94.2 ± 2.7) | 19 | (4/15) |

| 100 | Over 100 years old | (101.6 ± 1.8) | 5 | (0/5) |

| Total | (44.9 ± 27.8) | 446 | (183/263) | |

Gut microbiota was analysed in one sample per subject, except for two samples that were obtained from one boy and one girl at pre-weaning and weaning and three samples that were obtained from one girl at pre-weaning, weaning and 5 years of age

DNA Extraction from Faecal Samples

The collection and storage of faecal samples and DNA extraction were performed using previously described methods [25].

Real-Time PCR

Real-time PCR was performed using an ABI PRISM 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific K.K., Uppsala, Sweden) with SYBR Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa Bio, Shiga, Japan). Table 2 shows the primer sets that were used in this study. Since B. longum ssp. infantis, B. longum ssp. longum and B. longum ssp. suis are closely related in their 16S rDNA similarity [16, 18, 29], these three species are treated as the members of the B. longum group. Similarly, B. catenulatum and B. pseudocatenulatum are detected as the members of B. catenulatum group. B. adolescentis consisting genotypes A and B are detected with the primer sets for B. adolescentis group. Primer sets for B. gallinarum group, B. mongoliense and B. minimum were designed based on the sequences of a house keeping gene, clpC, with the sequences of related species/subspecies acquired from GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). After multiple alignments by MEGA 6 [31], unique regions were selected as a target for the specific primers. Since the genomic information of B. gallinarum, B. pullorum and B. saeculare is closely related [11], these three species are treated as B. gallinarum group and the primer set for B. gallinarum is designed to detect these three species.

Table 2.

The PCR primers used to detect each species

| Target species | Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bifidobacterium adolescentis group | BiADOg-1a | CTCCAGTTGGATGCATGTC | [16] |

| BiADOg-1b | TCCAGTTGACCGCATGGT | ||

| BiADOg-2 | CGAAGGCTTGCTCCCAGT | ||

| Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. lactis | Bflact2 | GTGGAGACACGGTTTCCC | [37] |

| Bflact5 | CACACCACACAATCCAATAC | ||

| Bifidobacterium bifidum | BiBIF-1 | CCACATGATCGCATGTGATTG | [17] |

| BiBIF-2 | CCGAAGGCTTGCTCCCAAA | ||

| Bifidobacterium breve | BiBRE-1 | CCGGATGCTCCATCACAC | [17] |

| BiBRE-2 | ACAAAGTGCCTTGCTCCCT | ||

| Bifidobacterium catenulatum group | BiCATg-1 | CGGATGCTCCGACTCCT | [17] |

| BiCATg-2 | CGAAGGCTTGCTCCCGAT | ||

| Bifidobacterium dentium | BiDEN-1 | ATCCCGGGGGTTCGCCT | [16] |

| BiDEN-2 | GAAGGGCTTGCTCCCGA | ||

| Bifidobacterium gallinarum group | BiGall_clpC_F2 | TGTGACGATCACCGATGC | This study |

| BiGall_clpC_R2 | GCTTGTGCAGCTCGCTCT | ||

| Bifidobacterium longum group | BiLONg-1 | TTCCAGTTGATCGCATGGTC | [17] |

| BiLONg-2 | TCSCGCTTGCTCCCCGAT | ||

| Bifidobacterium longum ssp. longum | BiLON-1 | TTCCAGTTGATCGCATGGTC | [16] |

| BiLON-2 | GGGAAGCCGTATCTCTACGA | ||

| Bifidobacterium minimum | BiMini_clpC_F | GGTCTTCGCAGCCGGTAT | This study |

| BiMini_clpC_F | CGACAACCATGCTGACGTTC | ||

| Bifidobacterium mongoliense | BiMong_clpC_F | ACGTGACCATCACCGACAAG | This study |

| BiMong_clpC_R | CATCTTCACATCGGAACCAC |

The amplification programme consisted of one cycle of 95 °C for 20 s, then 40 cycles of 95 °C for 20 s, 55 °C for 20 s and 72 °C for 50 s, and one final cycle of 95 °C for 15 s. The fluorescent product was detected in the last step of each cycle. Following amplification, a melting temperature analysis of the PCR products was performed to determine the specificity of the PCR. Melting curves were obtained by slow heating at 0.2 °C/s increments from 60 to 95 °C, with continuous collection of fluorescence data. To determine the number of Bifidobacterium species that were present in each sample, we compared the results to a standard curve that was generated using standard DNA in the same experiment. The following Bifidobacterium species were used as the standard strains for species-specific quantification: B. adolescentis JCM1275T, B. animalis ssp. lactis JCM1190T, B. bifidum JCM1255T, B. breve JCM1192T, B. dentium JCM1195T, B. gallinarum JCM6291T, B. longum ssp. longum JCM1217T, B. minimum JCM5821T, B. mongoliense JCM 15461T and B. pseudocatenulatum JCM1200T.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics, version 22.0, statistical software package (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Intergroup differences in the number of species were analysed using unpaired t-tests. Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used to determine the relationships among Bifidobacterium species by substituting the data with 6 log10 for individuals under the detection limits. For all statements, P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Quantitative PCR Detection of Bifidobacterium Species

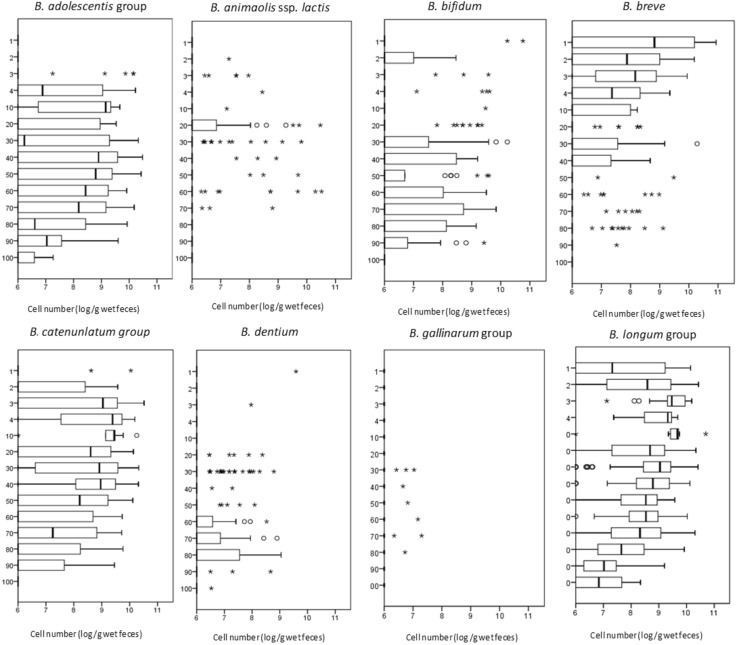

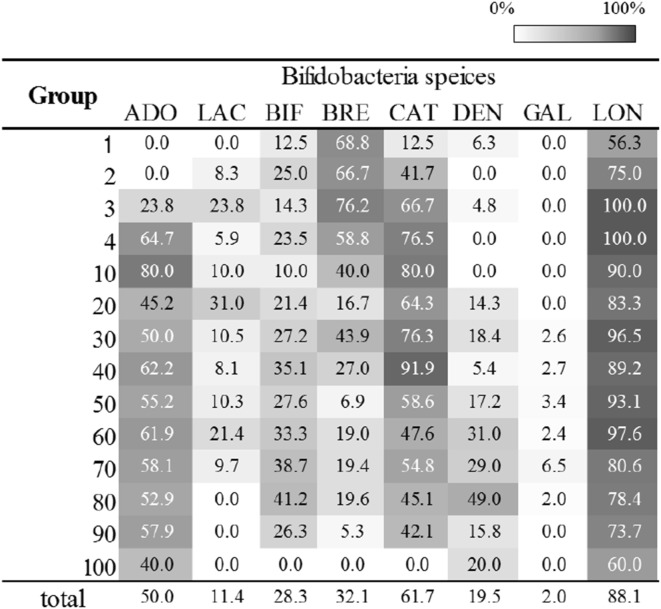

Figures 1 and 2 show the distributions and detection rates, respectively, of the eight Bifidobacterium species that were found in the faeces of 441 subjects. B. longum group was widely detected (8.7 ± 0.9 log10 cells per gram of wet faeces) in the majority of individuals, from infants before weaning to centenarians, and its detection rate was the highest of the investigated species (88.1%). The distribution of B. longum ssp. longum was nearly equal to those of B. longum group (Online Resource 1). B. catenulatum group species and B. bifidum were also commonly detected at all ages except for the centenarians, but their detection rates were lower (61.7 and 28.3%, respectively) than the rate for B. longum group. The B. catenulatum group and the B. adolescentis group were predominant after weaning. Conversely, B. breve was detected in 71.4% of children under 3 years old. The number of B. breve cells decreased with age, although its detection rate was consistently high in individuals younger than 10 years old. B. dentium was detected in some of the subjects who were over 20 years old, and its detection rate increased until the subjects reached 90 years old. B. animalis ssp. lactis, which is not considered a species of the human gut microbiota, was also detected in 11.4% of the subjects, but it was restricted to individuals between weaning and less than 80 years old. Both B. dentium and B. animalis ssp. lactis were present as relatively small populations of 7.4 ± 0.7 and 7.9 ± 1.2 log10 cells per gram of wet faeces, respectively. B. gallinarum goup was detected in only nine subjects aged 31–84 years, while B. minimum and B. mongoliense were not detected at any age.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of seven Bifidobacterium species in the faeces of healthy Japanese subjects aged 0–104 years. Cell numbers were determined as the log10 of cells per gram wet weight of faecal samples. The box plots show the interquartile range (IQR) of the cell numbers shown in each section. Open circles and asterisks indicate outliers between 1.5- and 3.0-fold IQR and over 3.0-fold IQR, respectively. The age of each group is as shown in Table 1. The detection limits for each bacterial species were determined using real-time PCR to be 106/g wet weight of faeces

Fig. 2.

Detection rate of each bifidobacteria species in each segmented age group. ADO, B. adolescentis group; LAC, B. animalis spp. lactis; BIF, B. bifidum; BRE, B. breve; CAT, B. catenulatum group; DEN, B. dentium; GAL, B. gallinarum group;LON, B. longum group. The age of each group is as shown in Table 1

Differences in Bifidobacterium Species Across Individuals

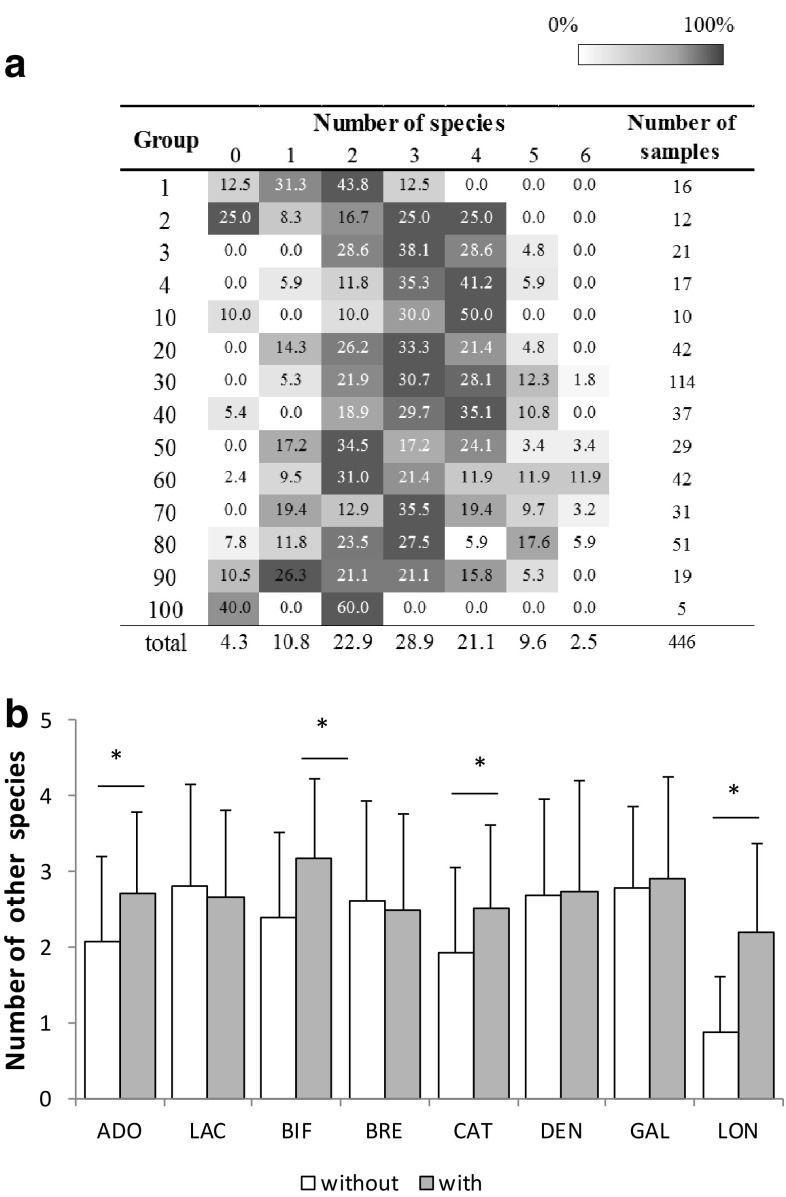

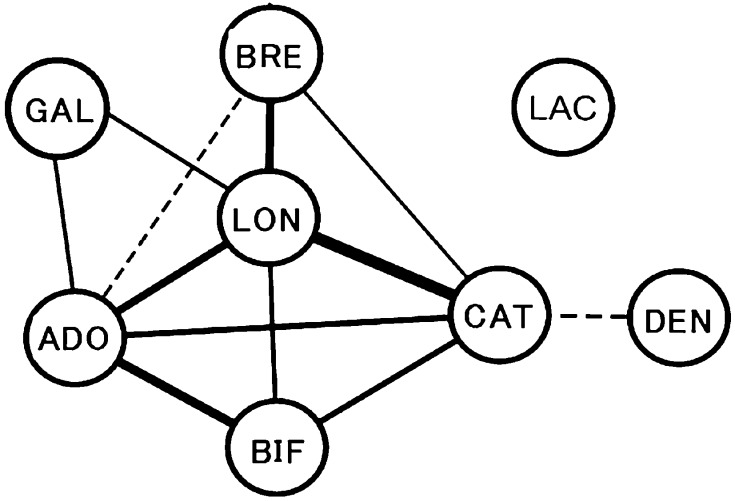

We then investigated the number of species that were detected in each individual. The mode for the species number was 2 to 4 in almost all segmented age groups (Fig. 3a). We found that the presence of B. longum group, B. adolescentis group, B. catenulatum group or B. bifidum led to the detection of significantly higher numbers of other Bifidobacterium species (Fig. 3b). The difference was the largest between subjects with (2.18 ± 1.17) or without (0.92 ± 0.75) B. longum group. A correlation analysis revealed that the presence of B. longum group was significantly associated with the presence of B. catenulatum group (r = 0.414, P < 0.001), B. breve (r = 0.320, P < 0.001), B. adolescentis group (r = 0.239, P < 0.001), B. bifidum (r = 0.139, P = 0.003) and B. gallinarum group (r = 0.123, P = 0.009, Fig. 4). B. breve, which was defined as an infant-type species, showed the significant negative correlation with B. adolescentis group species (r = −0.124, P = 0.009), which were defined as adult-type species. B. adolescentis group was significantly associated with B. gallinarum group (r = 0.145, P = 0.002) and B. catenulatum group (r = 0.119, P < 0.001). Another significant negative correlation was observed in B. dentium, which was defined as an elderly type species, and B. catenulatum group species (r = −0.142, P < 0.001). B. animalis ssp. lactis was not significantly correlated with other Bifidobacterium species.

Fig. 3.

Number of Bifidobacterium species. a Distribution of the numbers of Bifidobacterium species that were found in individuals in each age group. The age of each group is as shown in Table 1. b Differences in species numbers between subjects with or without the presence of identical species (i.e. the number of species excluding the identical species). ADO, B. adolescentis group; LAC, B. animalis spp. lactis; BIF, B. bifidum; BRE, B. breve; CAT, B. catenulatum group; DEN, B. dentium; GAL, B. gallinarum group; LON, B. longum group

Fig. 4.

Possible ecological compatibility among Bifidobacterium species. The solid and dashed lines indicate positive and negative correlations, respectively. The widths of the connected lines indicate the abundance of the coefficient value. ADO, B. adolescentis group; LAC, B. animalis spp. lactis; BIF, B. bifidum; BRE, B. breve; CAT, B. catenulatum group; DEN, B. dentium; GAL, B. gallinarum group; LON, B. longum group. Online Resource 1. Distribution of B. longum ssp. longum in the faeces of healthy Japanese subjects aged 0–104 years. The age of each group is as shown in Table 1

Discussion

The composition of the gut microbiota changes with age [22]. Recent studies using molecular methods have also indicated that there are clear differences in the composition of the gut microbiota between infants, toddlers, adults and the elderly [3]. Some reports have shown that there are intermittent differences between age groups [3, 8, 27, 41]. However, few reports have investigated the long-term, sequential changes in the composition of gut microbiota. Recently, we showed that there are sequential changes in the composition of the gut microbiota at the genus level in Japanese subjects over a wide range of ages, from 0 to 104 years old [25]. In this study, we focused on the genus Bifidobacterium and investigated the details of the changes that occurred in these species at the species level over the study age range. Our results are in agreement with those of previous studies indicating that there are differences in the proportions and types of Bifidobacterium species in the gut microbiota between infants, adults and the elderly [1, 8, 41].

Our results show the patterns and transition points that occur with ageing in the prevalence of each Bifidobacterium species. There is a decrease in the cell numbers of B. breve in subjects over 50 years old. Conversely, there is an increase in the cell numbers of B. dentium, a bacteria species whose genomic sequence has been reported to reflect its adaptation to human oral cavities [38], in subjects over 60 years old. We have found that certain oral bacteria that have been suggested to have difficulty in reaching the intestinal tract due to the GIT barriers, such as gastric juices and bile acid, were enriched in the elderly gut microbiota [25]. Our data imply that the decline in GIT functionality in the elderly might lead to significant changes in the presence of B. dentium and other oral bacteria in the gut.

Bifidobacterium longum group was the major species that were detected in all segmented age groups. Among B. longum group, B. longum ssp. longum and B. longum ssp. infantis have been reported to be detected in human gut microbiota [14, 16]. The distribution of B. longum ssp. longum was nearly equal to those of B. longum group, suggesting that the majority of B. longum group in human gut microbiota was B. longum ssp. longum at least in this study. Some strains of B. longum ssp. longum were shown to be genetically equipped to utilize both plant-derived and human milk oligosaccharide (HMO)-derived sugars [24, 42]. This characteristic might explain why B. longum ssp. longum is a widespread species at all ages. We also tried to evaluate the distribution of B. longum ssp. infantis, which has been reported to be a champion colonizer from the perspective of genomic information [36] and was frequently found in infants [16, 21]. However, we failed to enumerate them precisely due to a cross-reactivity of the reported specific primers, which were designed based on the sequence of type strain B. longum ssp. infantis [16, 30], against some strains of B. breve (data not shown). In addition, recent studies based on genomic information have indicated some mismatches between phenotype and genotype property, e.g. B. longum ssp. infantis 157 F and CCUG 52,486, which are assigned to infantis subspecies based on the phenotypes but are genetically longum subspecies [23]. Future studies such as taxonomical investigation as well as development of primers with high specificity are necessary to accurately estimate the cell numbers of B. longum ssp. infantis in the human gut microbiota.

B. animalis ssp. lactis, which is not considered a species of the human gut microbiota [35], was also detected in 11.4% of the subjects. Because this taxon is predicted to have a limited number of hypothetical glycosyl hydrolases/carbohydrate pathways [19, 20, 24], it seems to be unsuitable for using the carbon resources in the human gut environment. However, because B. animalis ssp. lactis is commonly applied as a probiotic in dairy products, its detection might be a reflection of food intake such as yogurt. Further identification of the B. animalis ssp. lactis strain found in the subjects and/or information regarding the dietary habits of the subjects would clarify the reason of this finding. The correlation analysis indicated that all of the species investigated in this study, with the exception of B. animalis ssp. lactis, were significantly correlated with other species. These results also suggest that B. animalis ssp. lactis is not a commensal component in the human gut. Previous study reported the detection of B. gallinarum/B. pullorum/B. saecularmay, B. minimum and B. mongoliense in Chinese centenarian [39]. However, these species were not detected in the five Japanese centenarians in the present study.

We found that subjects in whom B. longum group, B. bifidum, B. adolescentis group or B. catenulatum group species were detected to possess a significantly higher number of other Bifidobacterium species, suggesting that there may be symbiotic associations between Bifidobacterium species. B. breve was reportedly to be capable of cross-feeding on sugars released during the mucin-degrading activity of B. bifidum, which can utilize host-derived glycans, including those present in mucin [34] or HMOs [5], via two secreted N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidases and two secreted sialidases, respectively [20]. In a clinical study, Tannock et al. [32] also reported that breast milk-fed infants who harboured B. bifidum comprising greater than 10% of the total microbiota, had the highest abundances of total bifidobacteria. Interestingly, Ferrario et al. [7] found that co-cultivating Bifidobacterium species in media that simulated the adult and infant human gut environments resulted in an increase in the transcription of key genes required for biosynthesis of exopolysaccharides, which have been reported to have some important roles for modulating various aspects of bifidobacterial–host interaction, including the ability of commensal bacteria to remain immunologically silent and in turn provide pathogen protection [6]. However, it is still unclear whether these positive relationships are consistent among the Bifidobacterium species studied in this study as it is possible that these species which possess a positive correlation might just grow well under the same environmental conditions without sharing a mutualistic relationship. The results of our statistical analysis must therefore be interpreted cautiously because they are based on a limited dataset. An advanced culture method is necessary to clarify the relationships between each set of Bifidobacterium species.

Similar to what was found in a previous report [16], we found that the average number of species detected per individual was two and three in infants and adults, respectively. The average number of species was not different between adults and the elderly, until they reached 81–90 years old, at which point the number was slightly decreased with age in individuals over 91 years old. The average number of species and the cell numbers of each species in centenarians were relatively lower, but B. longum group, B adolescentis group and B. dentium were detected in centenarians. In previous reports, B. longum ssp. longum and B. adolescentis group were isolated from Chinese centenarians [9, 13], and these species have been suggested to improve intestinal digestion and the ability to enhance immune-barrier functions in mouse models [43]. These species may have important functions that contribute to the maintenance of a healthy condition in centenarians.

In conclusion, we provide a picture of the changes of Bifidobacterium species that occur with ageing in the gut microbiota. Our results indicate that there are patterns and transition points with respect to age-related changes in the composition of Bifidobacterium species. The positive correlations of our findings highlighted that there may be symbiotic associations between human residential species.

Our findings contribute to clarifying what is known about the composition of bifidobacteria in the gut of healthy populations at each age period. Further analyses that investigate genomic information and in vitro co-cultivation experiments would be valuable for evaluating the relationships between Bifidobacterium species.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr. Chyn Boon Wong for her critical check of this manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

Kumiko Kato, Toshitaka Odamaki, Eri Mitsuyama, Hirosuke Sugahara and Jin-zhong Xiao were employed by Morinaga Milk Industry Co., Ltd.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00284-017-1272-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Avershina E, Lundgård K, Sekelja M, Dotterud C, Storrø O, Øien T, Johnsen R, Rudi K. Transition from infant- to adult-like gut microbiota. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18:2226–2236. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avershina E, Storrø O, Øien T, Johnsen R, Wilson R, Egeland T, Rudi K. Bifidobacterial succession and correlation networks in a large unselected cohort of mothers and their children. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:497–507. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02359-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conlon MA, Bird AR. The impact of diet and lifestyle on gut microbiota and human health. Nutrients. 2015;7:17–44. doi: 10.3390/nu7010017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Gioia D, Aloisio I, Mazzola G, Biavati B. Bifidobacteria: their impact on gut microbiota composition and their applications as probiotics in infants. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:563–577. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5405-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egan M, O’Connell Motherway M, Ventura M, van Sinderen D. Metabolism of sialic acid by Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:4414–4426. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01114-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fanning S, Hall LJ, Cronin M, Zomera A, MacSharrya J, Gouldingd D, O’Connell Motherway M, Shanahana F, Nallya K, Dougand G, van Sinderena D. Bifidobacterial surface-exopolysaccharide facilitates commensal-host interaction through immune modulation and pathogen protection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:2108–2113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115621109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrario C, Milani C, Mancabelli L, Lugli GA, Duranti S, Mangifesta M, Viappiani A, Turroni F, Margolles A, Ruas-Madiedo P, van Sinderen D, Ventura M. Modulation of the eps-ome transcription of bifidobacteria through simulation of human intestinal environment. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2016 doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiw056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gavini F, Cayuela C, Antoine JM, Lecoq C, Lefebvre B, Membré J, Neut C. Differences in the distribution of bifidobacterial and enterobacterial species in human faecal microflora of three different (children, adults, elderly) age groups. Microb Ecol Health D. 2001;13:40–45. doi: 10.1080/089106001750071690. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hao Y, Huang D, Guo H, Xiao M, An H, Zhao L, Zuo F, Zhang B, Hu S, Song S, Chen S, Ren F. Complete genome sequence of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum BBMN68, a new strain from a healthy Chinese centenarian. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:787–788. doi: 10.1128/JB.01213-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hopkins MJ, Sharp R, Macfarlane GT. Age and disease related changes in intestinal bacterial populations assessed by cell culture, 16S rRNA abundance, and community cellular fatty acid profiles. Gut. 2001;48:198–205. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.2.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim BJ, Kim H-Y, Yun Y-J, Kim BJ, Kook YH. Differentiation of Bifidobacterium species using partial RNA polymerase {beta}-subunit (rpoB) gene sequences. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60:2697–2704. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.020339-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leahy SC, Higgins DG, Fitzgerald GF, Van Sinderen D. Getting better with bifidobacteria. J Appl Microbiol. 2005;98:1303–1315. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu S, Zhao L, Ren F, Sun E, Zhang M, Guo H. Complete genome sequence of Bifidobacterium adolesentis BBMN23, a probiotic strain from healthy centenarian. J Biotechnol. 2015;198:44–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makino H, Kushiro A, Ishikawa E, et al. Transmission of intestinal Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum strains from mother to infant, determined by multilocus sequencing typing and amplified fragment length polymorphism. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:6788–6793. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05346-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuki T, Watanabe K, Fujimoto J, Kado Y, Takada T, Matsumoto K, Tanaka R. Quantitative PCR with 16S rRNA-gene-targeted species-specific primers for analysis of human intestinal bifidobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:167–173. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.1.167-173.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuki T, Watanabe K, Tanaka R, Fukuda M, Oyaizu H. Distribution of Bifidobacterial species in human intestinal microflora examined with 16S rRNA-gene-targeted species-specific primers. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4506–4512. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.10.4506-4512.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsuki T, Watanabe K, Tanaka R, Oyaizu H. Rapid identification of human intestinal bifidobacteria by 16S rRNA-targeted species- and group-specific primers. FEMS Microbiol Oct. 1998;167:113–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mattarelli P, Bonaparte C, Pot B, Biavati B. Proposal to reclassify the three biotypes of Bifidobacterium longum as three subspecies: Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum subsp. nov., Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis comb. nov. and Bifidobacterium longum subsp. suis comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2008;58:767–772. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65319-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milani C, Duranti S, Lugli GA, Bottacini F, Strati F, Arioli S, Foroni E, Turroni F, van Sinderen D, Ventura M. Comparative genomics of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis reveals a strict monophyletic bifidobacterial taxon. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:4304–4315. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00984-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milani C, Lugli GA, Duranti S, Turroni F, Mancabelli L, Ferrario C, Mangifesta M, Hevia A, Viappiani A, Scholz M, Arioli S, Sanchez B, Lane J, Ward DV, Hickey R, Mora D, Segata N, Margolles A, van Sinderen D, Ventura M. Bifidobacteria exhibit social behavior through carbohydrate resource sharing in the gut. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15782. doi: 10.1038/srep15782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitsuoka T. Human microbiota research - present and future- J Intest Microbiol. 2005;19:179–192. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitsuoka T. Establishment of intestinal bacteriology. Biosci microbiota, food Heal. 2014;33:99–116. doi: 10.12938/bmfh.33.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Callaghan A, Bottacini F, O’Connell Motherway M, van Sinderen D. Pangenome analysis of Bifidobacterium longum and site-directed mutagenesis through by-pass of restriction-modification systems. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:832. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1968-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Odamaki T, Horigome A, Sugahara H, Hashikura N, Minami J, Xiao JZ, Abe F. Comparative genomics revealed genetic diversity and species/strain-Level differences in carbohydrate metabolism of three probiotic bifidobacterial species. Int J Genomics. 2015;2015:567809. doi: 10.1155/2015/567809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Odamaki T, Kato K, Sugahara H, Hashikura N, Takahashi S, Xiao JZ, Abe F, Osawa R. Age-related changes in gut microbiota composition from newborn to centenarian: a cross-sectional study. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16:90. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0708-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Odamaki T, Sugahara H, Yonezawa S, Yaeshima T, Iwatsuki K, Tanabe S, Tominaga T, Togashi H, Benno Y, Xiao JZ. Effect of the oral intake of yogurt containing Bifidobacterium longum BB536 on the cell numbers of enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis in microbiota. Anaerobe. 2012;18:14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ottman N, Smidt H, de Vos WM, Belzer C. The function of our microbiota: who is out there and what do they do? Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:104. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ouwehand AC, Bergsma N, Parhiala R, Lahtinen S, Gueimonde M, Finne-Soveri H, Strandberg T, Pitkälä K, Salminen S. Bifidobacterium microbiota and parameters of immune function in elderly subjects. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2008;53:18–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakata S, Kitahara M, Sakamoto M, Hayashi H, Fukuyama M, Benno Y. Unification of Bifidobacterium infantis and Bifidobacterium suis as Bifidobacterium longum. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol Nov. 2002;52:1945–1951. doi: 10.1099/00207713-52-6-1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheu SJ, Hwang WZ, Chiang YC, Lin WH, Chen HC, Tsen HY. Use of tuf gene-based primers for the PCR detection of probiotic Bifidobacterium species and enumeration of bifidobacteria in fermented milk by cultural and quantitative real-time PCR methods. J Food Sci Oct. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2010.01816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(12):2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tannock GW, Lawley B, Munro K, Gowri Pathmanathan S, Zhou SJ, Makrides M, Gibson RA, Sullivan T, Prosser CG, Lowry D, Hodgkinson AJ. Comparison of the compositions of the stool microbiotas of infants fed goat milk formula, cow milk-based formula, or breast milk. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:3040–3048. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03910-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsuji H, Oozeer R, Matsuda K, Matsuki T, Ohta T, Nomoto K, Tanaka R, Kawashima M, Kawashima K, Nagata S, Yamashiro Y. Molecular monitoring of the development of intestinal microbiota in Japanese infants. Benef Microbes. 2012;3:113–125. doi: 10.3920/BM2011.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turroni F, Bottacini F, Foroni E, Mulder I, Kim JH, Zomer A, Sánchez B, Bidossi A, Ferrarini A, Giubellini V, Delledonne M, Henrissat B, Coutinho P, Oggioni M, Fitzgerald GF, Mills D, Margolles A, Kelly D, van Sinderen D, Ventura M. Genome analysis of Bifidobacterium bifidum PRL2010 reveals metabolic pathways for host-derived glycan foraging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:19514–19519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011100107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Turroni F, Foroni E, Pizzetti P, Giubellini V, Ribbera A, Merusi P, Cagnasso P, Bizzarri B, de Angelis GL, et al. Exploring the diversity of the bifidobacterial population in the human intestinal tract. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:1534–1545. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02216-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Underwood MA, German JB, Lebrilla CB, Mills DA. Bifidobacterium longum subspecies infantis: champion colonizer of the infant gut. Pediatr Res. 2015;77:229–235. doi: 10.1038/pr.2014.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ventura M, Reniero R, Zink R. Specific identification and targeted characterization of Bifidobacterium lactis from different environmental isolates by a combined multiplex-PCR approach. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:2760–2765. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.6.2760-2765.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ventura M, Turroni F, Zomer A, Foroni E, Giubellini V, Bottacini F, Canchaya C, Claesson MJ, He F, Mantzourani M, Mulas L, Ferrarini A, Gao B, Delledonne M, Henrissat B, Coutinho P, Oggioni M, Gupta RS, Zhang Z, Beighton D. The Bifidobacterium dentium Bd1 genome sequence reflects its genetic adaptation to the human oral cavity. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000785. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang F, Huang G, Cai D, Li D, Liang X, Yu T, Shen P, Su H, Liu J, Gu H, Zhao M, Li Q. Qualitative and Semiquantitative analysis of fecal Bifidobacterium species in centenarians living in Bama, Guangxi, China. Curr Microbiol. 2015;71:143–149. doi: 10.1007/s00284-015-0804-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woodmansey EJ. Intestinal bacteria and ageing. J Appl Microbiol. 2007;102:1178–1186. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woodmansey EJ, McMurdo ME, Macfarlane GT, Macfarlane S. Comparison of compositions and metabolic activities of fecal microbiotas in young adults and in antibiotic-treated and non-antibiotic-treated elderly subjects. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:6113–6122. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.10.6113-6122.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamada C, Gotoh A, Sakanaka M, et al. Molecular insight into evolution of symbiosis between breast-fed infants and a member of the human gut microbiome Bifidobacterium longum. Cell Chem Biol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang H, Liu A, Zhang M, Ibrahim SA, Pang Z, Leng X, Ren F. Oral administration of live Bifidobacterium substrains isolated from centenarians enhances intestinal function in mice. Curr Microbiol. 2009;59:439–445. doi: 10.1007/s00284-009-9457-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Dominguez-Bello MG, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Baldassano RN, Anokhin AP, Heath AC, Warner B, Reeder J, Kuczynski J, Caporaso JG, Lozupone CA, Lauber C, Clemente JC, Knights D, Knight R. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. 2012;486:222–227. doi: 10.1038/nature11053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.