Abstract

Classification of condition severity can be useful for discriminating among sets of conditions or phenotypes, for example when prioritizing patient care or for other healthcare purposes. Electronic Health Records (EHRs) represent a rich source of labeled information that can be harnessed for severity classification. The labeling of EHRs is expensive and in many cases requires employing professionals with high level of expertise. In this study, we demonstrate the use of Active Learning (AL) techniques to decrease expert labeling efforts. We employ three AL methods and demonstrate their ability to reduce labeling efforts while effectively discriminating condition severity. We incorporate three AL methods into a new framework based on the original CAESAR (Classification Approach for Extracting Severity Automatically from Electronic Health Records) framework to create the Active Learning Enhancement framework (CAESAR-ALE). We applied CAESAR-ALE to a dataset containing 516 conditions of varying severity levels that were manually labeled by seven experts. Our dataset, called the “CAESAR dataset,” was created from the medical records of 1.9 million patients treated at Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC). All three AL methods decreased labelers’ efforts compared to the learning methods applied by the original CAESER framework in which the classifier was trained on the entire set of conditions; depending on the AL strategy used in the current study, the reduction ranged from 48% to 64% that can result in significant savings, both in time and money. As for the PPV (precision) measure, CAESAR-ALE achieved more than 13% absolute improvement in the predictive capabilities of the framework when classifying conditions as severe. These results demonstrate the potential of AL methods to decrease the labeling efforts of medical experts, while increasing accuracy given the same (or even a smaller) number of acquired conditions. We also demonstrated that the methods included in the CAESAR-ALE framework (Exploitation and Combination_XA) are more robust to the use of human labelers with different levels of professional expertise.

Keywords: Active learning, Electronic Health Records, Phenotyping, Condition, Severity

1. Introduction

Condition severity is an important aspect of medical conditions that can be useful for discriminating among sets of conditions or phenotypes. For example, a condition’s severity status can enable public health researchers to easily identify conditions that require higher prioritization and an allocation of resources. For the purposes of our research, we define severe conditions as those that are life-threatening or permanently disabling. Such conditions would be considered high priority in terms of the need to generate phenotype definitions for tasks including pharmacovigilance [44,45,47].

A prioritized list of conditions (disease codes) classified by severity at the condition-level is needed. Condition-level severity classification distinguishes acne (mild condition) from myocardial infarction (severe condition). In contrast, patient-level severity determines whether a given patient has a mild or severe form of a condition (e.g., acne). The bulk of the literature focuses on patient-level severity. Patient-level severity generally requires individual condition metrics [8–11], although whole-body methods exist [11–13]. None of the prior severity metrics or classification methods use condition-level severity metrics. Condition-level severity is important for prioritizing phenotypes.

Condition-level severity is useful for prioritizing conditions that are important for specialized phenotyping algorithms. Although several consortiums and partnerships, including the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership [1] and the Electronic Medical Records and Genomics Network [2,3], have developed phenotype extraction methods that utilize Electronic Health Records (EHRs), only a little more than 100 conditions/phenotypes have been successfully defined. Unfortunately, this represents a small fraction of the approximately 401,2001 conditions recorded in EHRs. Hurdles faced by experts when defining phenotype-extraction algorithms include overcoming definition discrepancies [4], data sparseness, data quality [5], bias [6], and healthcare process effects [7]. Condition severity can be a way for prioritizing conditions worthy of developing a specialized phenotype-extraction algorithm.

In our previous work we developed an algorithm which we refer to as the Classification Approach for Extracting Severity Automatically from Electronic Health CAESARecords (CAESAR) [13,47], which uses standard machine learning (also referred to as passive learning) to classify condition severity based on metrics extracted from EHRs [13]. This method requires medical experts to manually review all of the conditions and assign a severity status to each condition (i.e., severe or mild) independently from EHR metrics.

In the current study, we describe the development and validation of an active learning approach for classifying condition severity from EHRs, the Active Learning Enhancement of CAESAR or CAESAR-ALE. We recently introduced this approach which enhances our previous CAESAR framework [13] in a preliminary fashion [49]. We now provide a detailed description of the new methodology and our results. Using our new AL methods, we demonstrate that decreasing the number of labeled conditions required to train a classifier can reduce the theoretical burden on medical experts.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. In Section 2 we provide background and related work to this study. In Section 3 we describe our new methods which is followed by the evaluation in Section 4.

2. Background

In this study we use the SNOMED-CT ontology [14–16], because it is an expressive clinical ontology that is useful for retrieval [17]. Each coded clinical event is considered a “condition” or “phenotype,” with the knowledge that this is a broad definition [4]. In biomedicine, condition classification follows two main approaches: (1) manual approaches in which experts manually assign labels to conditions; and (2) passive classification approaches that require a labeled training set. Manual approaches include the development of the Chronic Condition Indicator (CCI) [18] involving expert assignment of chronicity categories (acute versus chronic) to the International Classification of Diseases – version 9 (ICD-9) codes. The CCI was built on original work by Hwang et al. [19] and was used successfully in multiple studies [19,20].

Other researchers have employed standard learning approaches in the biomedical domain, including a classification approach that leveraged the ICD-9 hierarchy for improved performance [21]. Another study classified conditions into chronicity categories [22]. Other machine learning approaches have been used in biomedicine for classifying text into condition hierarchies [48] to improve subsequent retrieval [55] compared to traditional free text [56]. Torii et al. [23] showed that performance improved when classifier was trained on a dataset based on multiple data sources and noted that having more documents available during training improved performance [23]. Nguyen et al. built an algorithm for classifying lung cancer stages using pathology reports and SNOMED-CT [24].

2.1. Mining Electronic Health Records

Secondary use of EHRs through data mining [57] has become a trendy area of biomedical informatics research [58] and the data mining literature [59,60,67]. Learning predictive models in clinical medicine through data mining is an important and developing field [58]. Ng et al. [61] introduced a distributed platform for healthcare analytics for EHR data that consists of the MapReduce principles that distributes and parallels the entire process of cohort construction, feature construction, and selection and classification in a cross validation fashion. Sun et al. [62] used this framework to predict hypertension transition points in EHR data without temporal representation. Rana et al. [64] introduced a framework that models the change in interventions over time to predict outcome events and considers the temporal evolution of the events that were shown to be useful. To handle temporal data [63] a comprehensive framework was introduced that enables learning patients’ behavior over time, including discovery of frequent temporal patterns [60], learning classification models [65], and acquiring cutoffs to discretize the variables into states to increase classification performance [66].

2.2. Active learning applications in biomedical data

Labeled examples, crucial for classification, are generally expensive to acquire, since they require medical experts for annotation. Active learning (AL) approaches are useful for selecting (for labeling) the most discriminative and informative conditions from a dataset during the learning process. This selection is expected to decrease the number of conditions that experts need to manually review and label. Studies in several domains have successfully applied AL to reduce the resources (i.e., time and money) required for labeling examples [25–27,68–71].

AL is divided roughly into two major approaches: (1) membership queries [28] in which examples are artificially generated from the problem space; and (2) selective-sampling [29] in which examples are selected from a pool. This paper only focuses on the selective-sampling approach. AL algorithms have been widely utilized in multiple domains, although applications in the biomedical domain remain limited. Liu described a method similar to relevance feedback for cancer classification [30]. Warmuth et al. used a similar approach to separate compounds for drug discovery [31]. AL was also used for cell image pathology [53] and assay classification [54]. More recently, AL was applied in biomedicine for text [32] and radiology report classification [33].

3. Methods

In this section we present the methods and techniques upon which our framework is based. We aim to provide a solution to an existing challenge in the area of efficient condition severity classification, and our framework is based on a combination of methods and techniques derived from previous research (ours and research conducted by others) that we believe will be most appropriate for achieving the goals of this study.

3.1. Support vector machines classification algorithm

The support vector machines (SVM) [46] classifier is a binary classifier that finds a linear hyperplane that separates given examples into two specific classes, yet is also capable of handling multiclass classification [50]. As Joachims [51] demonstrated, the SVM is widely known for its ability to handle a large amount of features, a capability which is useful in the textual domain.

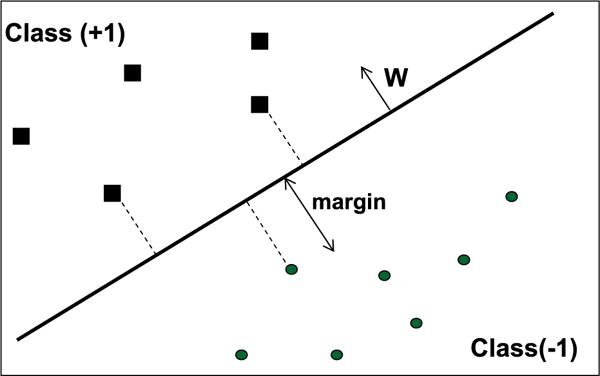

Given a training set in which an example is a vector xi = 〈f1, f2,…,fm〉, in which fi is a feature labeled by yi = {1,+1}, the SVM attempts to specify a linear hyperplane with the maximal margin defined by the maximal (perpendicular) distance between the examples of the two classes. Fig. 1 illustrates a two-dimensional space where the examples are positioned according to their features. The hyperplane splits them based on their labels.

Fig. 1.

An SVM with a maximal margin which separates the training set into two classes in a two-dimensional space (two features).

The examples lying closest to the hyperplane are the “supporting vectors.” W, the Normal of the hyperplane, is a linear combination of the most important examples (supporting vectors) multiplied by LaGrange multipliers (α), as can be seen in Eq. (3). Since the dataset in the original space cannot always be linearly separated, a kernel function K is used. SVM actually projects the examples into a higher dimensional space in order to create a linear separation of the examples. Note that when the kernel function satisfies Mercer’s condition, as Burges [52] explained, K can be presented using Eq. (1), where Φ is a function that maps the example from the original feature space into a higher dimensional space, while K relies on the “inner product” between the mappings of examples x1, x2. For the general case, the SVM classifier will be in the form shown in Eq. (2), where n is the number of examples in the training set, K is the kernel function, α is the LaGrange multiplier that defines the linear combination of the Normal W, and yi is the class label of support vector Xi.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Two commonly used kernel functions are used: (1) the polynomial kernel, as shown in Eq. (4)), creates polynomial values of degree p, where the output depends on the direction of the two vectors, examples x1, x2, in the original problem space (note that a private case of a polynomial kernel, where p = 1, is actually the linear kernel), and (2) the radial basis function (RBF), as shown in Eq. (5), in which a Gaussian function is used as the RBF, and the output of the kernel depends on the Euclidean distance of examples x1, x2.

| (4) |

| (5) |

3.2. Random selection

Random selection is not an active learning method, but it is the “lower bound” of the selection methods that will be discussed. As far as we know, no biomedical machine learning based solution has used an active learning method to reduce the labeling efforts of medical doctors in the task of condition severity classification. Random selection doesn’t have a sophisticated selection strategy; consequently, we expect that all of the AL methods we examine will perform better than a selection process based on the random selection of conditions. Thus, in the context of our framework, the random selection method will feed the SVM classifier with conditions that were randomly selected from the pool of unlabeled conditions. In our experiments we called this method Random Selection or just Random.

3.3. The SVM-Simple-Margin AL method (SVM-Margin)

The SVM-Simple-Margin method [35] (or SVM-Margin) is based on SVM classifier principles. Using a kernel function, the SVM implicitly projects the training examples into a different (usually a higher dimensional) feature space. In this space there is a set of hypotheses that are consistent with the training set, creating a linear separation of the training set. The SVM identifies the best hypothesis with the maximal margin from among the consistent hypotheses (referred to as the version-space [VS]). To achieve a situation in which the VS contains the most accurate and consistent hypothesis, the SVM-Margin AL method selects examples from a pool of unlabeled examples, thereby reducing the number of hypotheses. The SVM-Margin method selects examples according to their distance from the separating hyperplane to explore and acquire informative conditions, disregarding their labels. Examples that lie closest to the separating hyperplane (see Fig. 2 in which the selected examples from both classes are colored in red and lie inside the margin) are more likely to be informative (may improve the classifier’s capabilities) and therefore are acquired and labeled. SVM-Margin is fast; yet, as its authors indicate [35], this agility is achieved because of its rough approximation and assumptions that the VS is fairly symmetric and the hyperplane’s Normal, W (Eq. (3)), is centrally placed. These assumptions have been shown to fail significantly [36], because SVM-Margin may query instances whose hyperplane does not intersect with the VS and therefore may not be informative.

Fig. 2.

The examples (colored in red) that will be selected according to the SVM-Margin AL method’s criteria. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.4. The CAESAR-ALE framework

The purpose of our enhanced method, CAESAR-ALE, is to decrease the experts’ labeling efforts using AL methods. CAESAR-ALE does this by only asking experts to label informative conditions. Fig. 3 illustrates the process of labeling and acquiring new conditions by maintaining the updatability of the classification model within CAESAR-ALE. Conditions are introduced to the classification model, which is induced by an SVM algorithm on which AL methods are based. The classification model scrutinizes conditions and provides two values for each condition: a classification decision using the SVM classification algorithm and a calculation of the distance from the separating hyperplane. Informative conditions are defined as conditions that are expected to improve the classification model’s predictive capabilities when added to the training set. A condition that is identified as potentially informative by the AL method is sent to a human expert for labeling. In this manner, most potentially informative conditions are labeled and added to the training set so that a new and updated model will be induced.

Fig. 3.

The process of using AL methods to detect discriminative conditions requiring medical expert labeling.

By selecting the most informative conditions, the use of an AL method leads to a theoretical decrease in the labeling efforts, as compared to learning from the entire set of conditions. Using the AL approach, we can maintain an accurate model while decreasing the labeling efforts, since the induction method requires fewer examples, i.e., conditions, since the input instances are more informative. Accordingly, in our context, there are two types of conditions that may be considered informative. The first type includes conditions that the classifier has identified with a low level of confidence. Here, the probability of being mild is close to the probability of being severe. The calculation of probability in based on the distance of the example from the separating hyperplane of the SVM classifier – thus a maximal distance from the separating hyperplane represents a high level of confidence, while minimal distance from the separating hyperplane represents low confidence. Eq. (6) represents the distance of example x from the separating hyperplane of the SVM classifier (note that Eq. (2) makes use of this distance and provides a classification decision regarding the sign of the distance in which a positive sign means a positive class classification, while a negative sign means a negative class classification).

| (6) |

In order to calculate this probability using the distance of example x from the separating hyperplane according to the given classifier’s knowledge, we use a transformation function that converts distance value into probability [42], see Eq. (7):

| (7) |

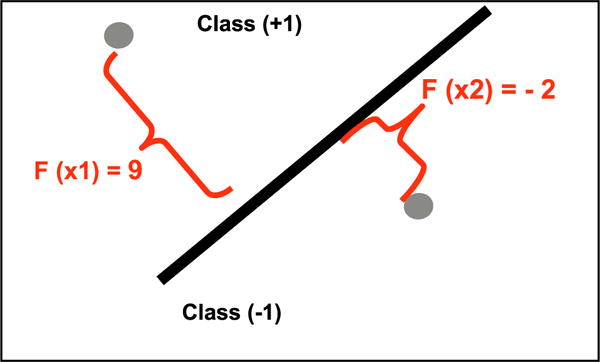

where y is an optional label of example x. {+1, −1}, h(x) is the decision value provided by Eq. (6). An illustration can be seen in Fig. 4, which shows two examples for which the SVM produced classification decision values.

Fig. 4.

Decision values given to two examples.

For instance: P (y = −1|X2) = 0.8 means that the classifier is quite confident that x2 belongs to class (−1). While P (y = +1|X2) = 0.2 means that the classifier is quite confident that X2 does not belong to class (+1); if P is (y = −1|X2) = (y = +1|X2) = 0.5, the classifier has a severe lack of confidence regarding the class of X2. A graphical analysis of Eq. (7) can be seen in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Analysis of Eq. (7) – the larger the distance the example is from the separating hyperplane, the higher the probability and the more confidence of the classifier.

The second type of informative conditions include conditions that are at a maximal distance from the separating hyperplane; these conditions are deep within the severe instances sub-space of the SVM’s separating hyperplane. Nevertheless, some mild conditions may still exist within this space of otherwise severe conditions (although, of course, their being mild is unknown to the algorithm, until they are selected and labeled). Consequentially, presenting these mild conditions to the induction algorithm is expected to greatly inform and improve the resulting classification model.

The overall CAESAR-ALE framework includes a repetition of two main phases: training and classification/updating, which includes the selection of potentially informative examples (i.e., conditions), labeling them, and then training the model with the new labeled conditions.

Training

The model is trained using an initial pool of severe and mild conditions. The model is evaluated against a test set consisting of conditions that were not used during training to estimate the classification accuracy.

Classification and updating

The AL method estimates and ranks how potentially informative each condition is within the pool of unlabeled conditions left, based on the classification model’s prediction. Only the most informative are selected and labeled by the expert. These conditions are added to the training set and removed from the pool. The model is then retrained using the updated training set, and this process repeats iteratively until a sufficient level of accuracy is reached or alternatively, until the entire pool of conditions have been acquired.

We employed the SVM classification algorithm using the radial basis function (RBF) kernel in a supervised learning approach. This combination had been shown to be very efficient when combined with AL methods [26,27]. We use the Lib-SVM implementation [34] and modify it to implement our AL methods.

Although our focus in this study is on reducing the condition labeling efforts while maintaining similar or enhanced classification performance, the detection of severe conditions – even during the learning phase (as opposed to the detection of mild conditions) – has some advantages, due to their value for training and insurance reporting purposes.

3.5. CAESAR-ALE’s active learning methods

CAESAR-ALE uses two AL methods (Exploitation and Combination_XA). We describe each of these, along with the SVM-Margin and Random methods below.

3.5.1. Exploitation

One of the AL methods implemented in CAESAR-ALE is called Exploitation, referred to as such because it exploits the current separating hyperplane to find condition instances that are most likely to be severe. Exploitation has shown efficiency at detecting unknown malicious code content, files [37–40], and documents [41]. Exploitation is based on SVM classifier principles and selects examples more likely to be severe, those lying further from the separating hyperplane, as can be seen in Fig. 2. Thus, this method aims at boosting the classification capabilities of the model through the acquisition of as many new severe conditions as possible. For every condition x, Exploitation measures its distance from the separating hyperplane using Eq. (8), based on the Normal (W) of the separating hyperplane of the SVM classifier. The separating hyperplane of the SVM is represented by W, which is a linear combination of the most important examples (supporting vectors), multiplied by LaGrange multipliers (α) and by the kernel function K that assists in achieving linear separation in higher dimensions. Accordingly, the distance in Eq. (8) is calculated between example x and the Normal (W) presented in Eq. (3). The distance calculation required for each instance in Exploitation is equal to the time it takes to classify an instance using SVM-Margin.

| (8) |

Acquiring several severe conditions that are highly similar to each other (i.e., which have similar values for all of the meaningful features, and of course, belong to the same target class) would waste labeling resources, while not contributing much to the future classification capabilities (generality) of the induced classifier; therefore, acquiring one representative condition from this set is preferable. In the Exploitation method, conditions are acquired if they are classified as severe and have maximal distance from the separating hyperplane (marked with a red2 circle in Fig. 6). To enhance the training set as much as possible, we also check the similarity among selected conditions using the kernel farthest-first (KFF) method suggested by Baram et al. [42], enabling us to avoid acquiring similar conditions. Consequently, only potentially informative conditions likely to be labeled as severe are selected. In Fig. 6, it can be seen that there are several sets of highly similar conditions, based on their distance in the kernel space. However, only representative conditions that are more likely to be severe are acquired. Contrary to SVM-Margin, Exploitation explores the “severe space” to discover potentially more informative severe conditions, a process which enables further detection of severe conditions. Fig. 6 also illustrates an additional ability of Exploitation as it sometimes discovers conditions located far inside the severe side (i.e., class) that were ultimately labeled by the expert as mild. Finding such a surprise is useful – this type of confusing condition will become a new support vector of the SVM classifier and update the classification model with the new discovery and knowledge, and therefore these “surprises” play an important role in increasing the accuracy of the resultant classifier.

Fig. 6.

Diagram showing the Exploitation method’s criteria for acquiring new severe conditions.

3.5.2. Combination_XA: a combined active learning method

The “Combination_XA” method is a hybrid of SVM-Margin and Exploitation. It conducts a cross acquisition (XA) of potentially informative conditions. That means that during the first trial (and all odd-numbered trials) it acquires conditions according to the SVM-Margin method’s criteria, while during the next trial (and all even-numbered trials) it selects conditions using the Exploitation method’s criteria. This strategy alternates between the exploration phases (conditions acquired using SVM-margin) and the exploitation phase (conditions acquired using Exploitation) to select the most informative conditions, both mild and severe, while boosting the classification model with severe conditions or very informative mild conditions that lie deep inside the severe side of the SVM’s hyperplane.

4. Evaluation

The objective of our two experiments is to evaluate and compare the performance of CAESAR-ALE’s two proposed AL methods to the three alternatives (SVM-Margin, Random Selection, and learning from the entire set of conditions) based on the following three tasks:

Improving the predictive capabilities (accuracy) of the classification model that serves as the knowledge store of the AL methods and its ability to efficiently identify the most informative unlabeled conditions.

Evaluating the proposed AL methods in comparison to the baseline methods based on their ability to correctly classify severe conditions (TPR) with minimal errors (FPR).

Evaluating all of the selection methods using seven different labelers (experts who labeled the conditions) and measuring the variance of their learning curves.

These three tasks raise two research questions:

-

-

Is it possible to efficiently create a condition severity classification model that uses AL methods to significantly reduce the labeling efforts of the medical expert?

Experiment 1

Our first experiment aims to evaluate and compare the selection methods in the task of the efficient creation of an accurate severity classification model while reducing the labeling efforts of medical experts. In our first acquisition experiment we use a repository of 516 conditions (CAESAR dataset) consisting of 372 mild and 144 severe conditions. Ten randomly selected datasets are created in order to perform 10-fold cross-validation evaluation. Each fold contains three elements: (1) an initial set of six conditions that are used to induce the initial classification model, (2) a test set of 200 conditions on which the induced classifier is tested and evaluated in each active learning iteration, and (3) a pool of 310 unlabeled conditions from which the conditions are selected to be labeled by each one of the examined selection methods. The process is repeated, through the iterative acquisition steps, until the entire pool is acquired. The performance of the classification models is averaged over the ten runs of the 10-fold cross-validation.

The experiment’s steps are as follows:

Inducing the initial classification model from the initial training set containing six conditions.

Evaluating the classification model using the 200 condition test set to measure its initial performance.

Introducing the pool of 310 unlabeled conditions to the sampling methods. During every trial the five most informative conditions are selected according to the selection method’s preferences, and their labels are revealed by the single gold standard labeler used in the original CAESAR system (in a real system the selected conditions will be labeled by an expert, but in our dataset all of the conditions are already labeled).

Adding the acquired conditions to the training set and removing them from the pool.

Inducing an updated classification model using the updated training set and applying the updated model to the conditions remaining in the pool.

This process iterates until the entire pool is acquired.

Based on the results of this first experiment we are able to determine the potential cost savings associated with the use of CAESER-ALE by estimating the cost of labeling the condition-level severity for all conditions contained in SNOMED-CT (10,529 conditions) by three expert labelers. To do this, we kept track of the number of conditions labeled per minute by our physician collaborators in our second experiment (described below). We then use the customary estimate for physicians’ time ($120 per hour) [43] to estimate the cost of labeling the entire dataset (Eq. (9)). We calculate the estimated savings as the entire cost * reduction in labeling efforts (Eq. (10)).

| (9) |

| (10) |

Experiment 2

Our second experiment is aimed at assessing the differences in the learning curves of the severity classification models induced from conditions that were labeled by each one of the seven different labelers. The conditions are selected using the same acquisition process described in the first experiment, however here, in experiment 2, they are actively selected only by the three AL methods in order to provide a more focused comparison between the AL methods. We use a dataset containing 100 conditions labeled by seven different labelers as our pool (three labelers are medical doctors who have completed their residency training, and the remaining four labelers are informatics experts with at least a master’s degree). We follow the same steps outlined in our first experiment in which we established our initial set of six seeds conditions from the gold standard. The initial classification model is trained on six randomly selected conditions. After each acquisition step we evaluate the performance of each of the labelers using the remaining 410 conditions from the gold standard (516 conditions 6 seed conditions) (100 conditions given to all seven labelers) = 410 remaining conditions in the gold standard. This allows us to compare differences among the various labelers at each acquisition step. This experiment is also evaluated using 10-fold cross-validation. Note that the conditions are presented to the labelers in a different order, depending on the learning algorithm used and on the labels assigned by the labeler to previous condition instances.

CAESER dataset

We obtain a dataset of conditions, along with six severity-related metrics related to each condition. These metrics or features consist of: average number of comorbidities, average number of procedures, average number of medications, average cost of procedures, average treatment time, and a proportion term [47]. Each of these severity-related metrics was computed using an underlying dataset of over 1.9 million patients. The proportion term is calculated to normalize each severity metric using the entire corpora and combine all five metrics into one weighted term.

Each condition’s proportion term was calculated previously as part of CAESAR’s construction, additional details are found in that study [47]. The method for calculating the proportion term is as follows. To calculate the proportion term we first calculate a proportion for each of the five measures. We then sum these individual proportions and divide by the total (i.e., five). It is easiest to illustrate this with an example. Let us assume the condition “myocardial infarction” has an average procedure cost of $10,000, and an average treatment length of 30 days, an average number of medications of 10, an average number of procedures of 6, and an average number of comorbidities of 3. Each of these values would be divided by their respective maximums. Therefore, the proportions are as follows: average procedure cost – $10,000/$50,000; average treatment length – 30/1406 days; average number of medications – 10/25; average number of procedures – 6/15; and average number of comorbidities – 3/100. Each of these proportions are then summed:

This yields the proportion index term for this condition.

5. Results

We evaluate the efficiency and effectiveness of CAESAR-ALE by comparing the two CAESAR-ALE selective sampling methods, Exploitation and Combination_XA, to the two other selective sampling methods: Random Selection (Random) and SVM-Simple-Margin (SVM-Margin) [27]. For all methods, results are averaged over ten different runs of the 10-fold cross-validation.

We now present results for the core evaluation measures used in this study: accuracy, TPR, FPR, and AUC. In addition, we also measure the number of new severe conditions discovered and acquired into the training set at each trial. As explained above, five conditions are selected from a pool of unlabeled conditions during each trial of CAESAR-ALE. It is well known that selecting more conditions per trial will improve accuracy. We use a low acquisition amount of five conditions per trial, because our primary goal is to minimize the number of conditions sent to medical experts for manual labeling and thereby reduce costs.

Fig. 7 presents accuracy levels and their trends in the 62 trials with an acquisition amount of five conditions per trial (62 * 5 = 310 conditions in pool). In most trials, the AL methods outperformed the Random selection method, illustrating that by using the AL methods, one can reduce the number of conditions required to achieve a rate of accuracy similar to that achieved by learning from the entire set of conditions. The classification model had an initial accuracy rate of 0.72, and all methods converged at an accuracy rate of 0.975 after the pool was fully acquired. Combination_XA arrived at a 0.95 rate of accuracy first, after requiring only 23 acquisition trials (115/310 conditions), while other AL methods required 26 trials. Further, Combination_XA performed almost twice as well as Random (23 versus the 44 trials that Random required), while achieving the same accuracy rate of 0.95. Summarizing the results regarding rates of accuracy, Combination_XA’s performance represents a reduction of 48% in labeling efforts compared to Random.

Fig. 7.

The accuracy of CAESAR-ALE AL methods versus SVM-Margin and Random over 62 trials (five conditions acquired during each trial).

Considering the overall learning phase, Exploitation outperformed the Combination_XA method up to trial 35, while after trial 35 Combination_XA presented slightly better performance – indicating that the cross-acquisition strategy is superior for the long run.

Fig. 8 shows TPR levels (severe is the positive class) and their trends over 62 trials. Both Exploitation and Combination_XA outperformed the other selection methods, achieving a TPR rate of 0.85 after only 17 trials (85/310 conditions), while Random achieved the same TPR rate after 47 trials. Summarizing the results regarding TPR rates, the performance of Exploitation and Combination_XA represents a reduction of 64% in labeling efforts compared to Random Selection. As can also be seen in Fig. 8, the performance improved as more conditions were acquired. After 36 trials, all AL methods converged to TPR rates around 0.92. Our results demonstrate that using AL methods for condition selection can reduce the number of trials required in training the classifier. This will reduce the total number of conditions requiring medical expert labeling and thereby reduce costs.

Fig. 8.

TPR for active learning and random selection methods over 62 trials.

The cumulative number of severe conditions acquired for each trial is shown in Fig. 9. By the fifth trial, CAESAR-ALE’s methods, Exploitation and Combination_XA, outperformed the other selection methods with respect to the rate of acquiring severe condition instances (both lines overlap in Fig. 9). After 23 trials (115 conditions), both of CAESAR-ALE’s methods acquired 73 out of the 82 severe conditions in the pool, compared to 42 trials (210 conditions) for the SVM-Margin method and 60 trials (300 conditions) for the Random method. This represents a 46% reduction in the number of trials required to acquire the same number of severe condition instances compared to the SVM-margin method, and a 62% reduction in the labeling efforts compared to the Random method. After 23 trials (Fig. 9), we observed the largest difference between CAESAR-ALE’s methods and Random - a difference of 43 severe conditions.

Fig. 9.

The accumulated number of severe conditions acquired into the training set by each AL method over 62 trials.

In Fig. 10, it can be observed that the variance among the learning curves induced for each labeler depends in part on the AL method used (Fig. 10A–C). Fig. 10D shows the overall variance among labelers by method and the methods’ average variance. Combination_XA was lowest with a variance of 0.0197, followed closely by Exploitation with a variance of 0.0209. In contrast, SVM-Margin had the highest variance (almost 50% greater than Combination_XA).

Fig. 10.

The learning curves of the three AL methods for each of the expert labelers.

We performed a single-factor Anova statistical test on the standard deviation of the labelers for both Combination_XA and Exploitation. The Anova test provided a P-Value of 67.93% which is much higher than the 5% (alpha) of the significance level; thus the difference between the methods is not statistically significant, confirming that Exploitation is as robust as Combination_XA to the different clinical training levels of the labelers.

We also estimate the cost to label the severity of the 10,529 conditions contained in SNOMED-CT by the three physician labelers. Based on our experiments and experience, physicians were able to label 2.5 conditions per minute. Based on the typical physician salary of $2 per minute of time ($120 per hour), we calculate the estimated savings achieved by utilizing the CAESAR-ALE framework to select meaningful conditions (for labeling) from the entire 10,529 condition set. Based on our calculations, the entire set would cost $13161.25 per physician labeler, with a total cost of $39483.75 for three labelers. We found that CAESAR-ALE reduced labeling efforts by at least 48%, resulting in a savings of at least $18,952.

6. Discussion

We introduce CAESAR-ALE, an active learning based framework used to identify informative conditions for medical expert labeling. The overall task is to classify conditions into severe and mild, based on features extracted from an EHR database. In our dataset, each condition is further represented by five features/metrics including: average number of comorbidities, average number of procedures, average number of medications, average cost, average treatment time, and a proportion term. Based on these metrics, conditions can be categorized as severe or mild, and this information can be used to train a classifier with good classification performance. However, labeling the conditions requires the expertise and involvement of medical experts which is costly. In response to this issue, we developed CAESAR-ALE, a framework based on active learning methods that decreases the need for labeling by medical experts. In this paper, we propose two active learning based methods (Combination_XA and Exploitation) oriented at the acquisition of potentially severe conditions. We define severe conditions as those that are life-threatening or permanently disabling. Acquiring such severe conditions is beneficial because of their value for training purposes and insurance reporting needs. In addition, we also assume that favoring potentially severe conditions will decrease the chances of misclassifying a severe condition as mild, which is often the more costly mistake.

We evaluate these two methods and compare them to two baselines methods: (1) a very basic method using random selection, and (2) SVM-Margin, an existing active learning method; our evaluation also includes comparison to learning from the entire set of conditions. Several measures are used to evaluate CAESAR-ALE: accuracy, TPR, FPR, and AUC. Combination_XA and Exploitation achieved a TPR of 0.85 after only 17 trials during which 85 conditions were acquired. Therefore, in this scenario only these 85 conditions will require manual expert labeling. In contrast, Random Selection required 47 trials or 235 conditions to achieve the same TPR. This comparison demonstrates that by using our AL methods, a reduction of 64% in labeling efforts can be achieved. This reduction also results in significant cost savings (almost two-thirds of the cost), allowing medical experts to focus their energy elsewhere.

In terms of accuracy rates, as expected, all of the AL methods performed better than the Random Selection method, while Combination_XA performed slightly better than the others, with a meaningful reduction in the number of trials from 44 to 23 (23 trials when using the Random Selection method). The Combination_XA method required only 115 conditions versus the 220 required by Random (representing a 48% reduction), to achieve the same rate of accuracy. For our purposes, FPR is less important (we don’t mind calling some mild conditions severe, as long as we accurately capture all severe conditions), therefore we can focus on the TPR measure and reduce efforts and cost by 64% without compromising the classification performance. However, in some instances we may desire maximal accuracy, and in those cases we will still achieve a reduction of 48% in the number of trials required when using CAESAR-ALE’s Combination_XA AL method versus Random Selection.

Note that in some cases it might be beneficial, even during the training phase, to increase the rate and number of severe conditions acquired, (e.g., for the purpose of reporting them to insurance companies). By using the Combination_XA and Exploitation AL methods within CAEASER-ALE, one can achieve a reduction of 62% in labeling efforts. CAEASER-ALE’s AL methods acquired severe conditions much more quickly than baseline methods. In the 23rd trial, our Al methods managed to acquire almost 90% of the severe conditions (73out of 82) after investing only 37% of the time and labeling efforts required to acquire all of the severe conditions by Random or by labeling the entire pool of conditions. As can be seen, the use of AL methods, and our two AL methods in particular, results in a very significant improvement in the number of severe conditions acquired, compared to the linear and poor improvement demonstrated by the Random Selection method. The best example of the strength of our AL methods can be found in the performance demonstrated during the early acquisition stages, when again in the 23rd trial, our AL methods acquired almost 2.5 times more severe conditions than Random (72 compared to 30).

The acquisition results achieved by the Exploitation and Combination_XA methods were superior compared to Random and SVM-Margin, can be explained by the way they function. Both methods have an exploitation phase during which they attempt to acquire more severe conditions. Thus, both methods occasionally acquire mild conditions which initially were thought to be severe. These mild conditions are very informative to the classification model, because they lead to a major modification of the SVM classifier’s margin and its separating hyperplane. Consequently, acquiring these conditions improves the performance of the model.

Alternatively, traditional AL methods (e.g., SVM-Margin) focus on acquiring examples (in our study conditions) that lead to only small changes in the separating hyperplane and thus contribute less to the improvement of the classification model. We understand from this phenomenon that there are often noisy “mild” conditions lying deep within what seems to be the sub-space of the severe conditions, as was explained in a recent study that focused on the detection of PC Malware [37]. As noted, these “surprising” cases are very informative and valuable in contributing to the improvement of the classification model. They are helpful in acquiring severe conditions that eventually update and enrich the knowledge store. It should be noted that these conditions are more informative than severe conditions, because they provide relevant information that was previously not considered (they were initially tentatively classified as severe by the classifier when in fact they are mild). The CAESAR-ALE framework induces a better classification model by acquiring more severe conditions within the same number of iterations.

Furthermore, the SVM-Margin method acquires examples that the classification model cannot confidently classify (there is low confidence regarding their correct class). Consequently, they are informative but are not necessarily severe. In contrast, the CAESAR-ALE framework is oriented toward acquiring the most informative severe conditions by obtaining conditions from the severe side of the SVM classifier’s margin. As a result, more new severe conditions are acquired in earlier trials. Additionally, if an acquired mild condition lies deep within the severe side of the margin, it is still informative and can be used to improve the classification capabilities of the model for the upcoming trial.

In addition to the above mentioned results and improvements, we observed that after acquiring 95 conditions (19trials), CAESAR-ALE achieved a 93.1% Positive Predictive Value (PPV), compared to a 80.1% PPV achieved using Random Selection. This represents more than a 13% absolute improvement in the predictive capabilities of CAESAR-ALE for classifying conditions as severe. This improvement was achieved with a significant reduction in labeling efforts, a 51% reduction for equivalent accuracy (92.5%).

Importantly, we demonstrate that our AL methods in the CAESAR-ALE framework (Exploitation and Combination_XA) are more robust to the use of different human labelers, having different levels of domain knowledge. In fact, our method, Combination_XA, acquired conditions in such a way that the variance between the classifiers created by individual labelers was 50% lower than the variance of learning curves that were based on the acquisition of the traditional SVM-Margin AL method.

7. Conclusion and future work

We present the CAESAR-ALE framework which uses AL methods to identify important conditions for labeling. CAESAR-ALE reduced labeling efforts by 48% when classifying conditions into severe and mild conditions while achieving equivalent classification accuracy. CAESAR-ALE reduced labeling efforts by 48% when classifying conditions into severe and mild conditions, while achieving equivalent classification accuracy comparable to a scenario in which a passive learning is being applied. Use of the CAESAR-ALE framework has the potential to result in significant monetary savings. In future work, we would like to develop an online tool for medical experts to label condition severity. This will facilitate a more extensive condition severity labeling experiment that will enable us to examine labeling differences based on the experts’ clinical background or geographical location.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the labelers who patiently labeled condition severity status in our dataset. This research was paritally supported by the National Cyber Bureau of the Israeli Ministry of Science, Technology and Space. Support for portions of this research was provided by R01 LM006910 (GH) and R01 GM107145 (NPT). MRB is supported by the National Library of Medicine training grant T15 LM00707.

Abbreviations

- CAESAR

Classification Approach for Extracting Severity Automatically from Electronic Health Records

- CAESAR-ALE

Classification Approach for Extracting Severity Automatically from Electronic Health Records – Active Learning Enhancement

- EHR

Electronic Health Record

- AL

Active Learning

- SVM

Support Vector Machines

- VS

Version Space

- SNOMED-CT

Systemized Nomenclature of Medicine-Clinical Terms

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases – Version 9

- SVM-Margin

Support Vector Machines-Margin Method – an existing AL method oriented towards acquiring informative conditions that lie closest to the separating hyperplane (inside the margin)

- Exploitation

an AL method included in the CAESAR-ALE framework that is oriented towards acquisition of severe conditions

- Combination_XA

an AL method included in the CAESAR-ALE framework that combines elements of the Exploitation method and the SVM-Margin method, so that it applies a hybrid acquisition strategy for enhanced improvement of the CAESER method

Footnotes

The number of SNOMED-CT codes as of September 9, 2014. Accessed via: http://bioportal.bioontology.org/ontologies/SNOMEDCT.

For interpretation of color in Fig. 6, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.

References

- 1.Stang PE, Ryan PB, Racoosin JA, et al. Advancing the science for active surveillance: rationale and design for the observational medical outcomes partnership. Ann Intern Med. 2010 Nov 2;153(9):600–606. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-9-201011020-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kho AN, Pacheco JA, Peissig PL, et al. Electronic medical records for genetic research: results of the eMERGE consortium. Sci Translational Med. 2011 Apr 20;3(79):79re1. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denny JC, Ritchie MD, Basford MA, et al. PheWAS: demonstrating the feasibility of a phenome-wide scan to discover gene–disease associations. Bioinformatics. 2010 May 1;26(9):1205–1210. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boland MR, Hripcsak G, Shen Y, Chung WK, Weng C. Defining a comprehensive verotype using electronic health records for personalized medicine. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013 Dec 1;20(e2):e232–e238. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-001932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiskopf NG, Weng C. Methods and dimensions of electronic health record data quality assessment: enabling reuse for clinical research. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(1):144–151. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hripcsak G, Knirsch C, Zhou L, Wilcox A, Melton GB. Bias associated with mining electronic health records. J Biomed Discov Collab. 2011;6:48. doi: 10.5210/disco.v6i0.3581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hripcsak G, Albers DJ. Correlating electronic health record concepts with healthcare process events. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013 Dec 1;20(e2):e311–e318. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-001922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rich P, Scher RK. Nail psoriasis severity index: a useful tool for evaluation of nail psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(2):206–212. doi: 10.1067/s0190-9622(03)00910-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the insomnia severity index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2(4):297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al. The fifth edition of the addiction severity index. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9(3):199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rockwood TH, Church JM, Fleshman JW, et al. Patient and surgeon ranking of the severity of symptoms associated with fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42(12):1525–1531. doi: 10.1007/BF02236199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horn SD, Horn RA. Reliability and validity of the severity of illness index. Med Care. 1986;24(2):159–178. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198602000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boland MR, Tatonetti NP, Hripcsak G. CAESAR: a Classification Approach for Extracting Severity Automatically from Electronic Health Records. 2014 doi: 10.1186/s13326-015-0010-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elkin PL, Brown SH, Husser CS, et al. Evaluation of the content coverage of SNOMED CT: ability of SNOMED clinical terms to represent clinical problem lists, Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 2006, Elsevier. 2006:741–748. doi: 10.4065/81.6.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stearns MQ, Price C, Spackman KA, Wang AY. SNOMED clinical terms: overview of the development process and project status. Proceedings of the AMIA Symposium, 2001, American Medical Informatics Association. 2001:662. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elhanan G, Perl Y, Geller J. A survey of SNOMED CT direct users, 2010: impressions and preferences regarding content and quality. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011 Dec 1;18(Suppl 1):i36–i44. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000341. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moskovitch R, Shahar Y. Vaidurya: a multiple-ontology, concept-based, context-sensitive clinical-guideline search engine. J Biomed Inform. 2009 Feb;42(1):11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.HCUP Chronic Condition Indicator for ICD-9-CM. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) 2011 http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/chronic/chronic.jsp> accessed on February 25, 2014.

- 19.Hwang W, Weller W, Ireys H, Anderson G. Out-of-pocket medical spending for care of chronic conditions. Health Aff. 2001 Nov 1;20(6):267–278. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.267. 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chi M-j, Lee C-y, Wu S-c. The prevalence of chronic conditions and medical expenditures of the elderly by chronic condition indicator (CCI) Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;52(3):284–289. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perotte A, Pivovarov R, Natarajan K, Weiskopf N, Wood F, Elhadad N. Diagnosis code assignment: models and evaluation metrics. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014 Mar 1;21(2):231–237. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-002159. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perotte A, Hripcsak G. Temporal properties of diagnosis code time series in aggregate. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2013 Mar;17(2):477–483. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2013.2244610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torii M, Wagholikar K, Liu H. Using machine learning for concept extraction on clinical documents from multiple data sources. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011 Jun;27 doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000155. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen AN, Lawley MJ, Hansen DP, et al. Symbolic rule-based classification of lung cancer stages from free-text pathology reports. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2010 Jul 1;17(4):440–445. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2010.003707. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nissim N, Moskovitch R, Rokach L, Elovici Y. Novel active learning methods for enhanced PC malware detection in windows OS. Expert Syst Appl. 2014;41(13):5843–5857. 10/1/ [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nissim N, Moskovitch R, Rokach L, Elovici Y. Detecting unknown computer worm activity via support vector machines and active learning. Pattern Anal Appl. 2012;15:459–475. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nissim N, Cohen A, Glezer C, Elovici Y. Detection of malicious PDF files and directions for enhancements: a state-of-the art survey. Comput Secur. 2015;48:246–266. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Angluin D. Queries and concept learning. Mach Learn. 1988;2:319–342. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis D, Gale W. A sequential algorithm for training text classifiers. Proceedings of the Seventeenth Annual International ACM-SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Springer-Verlag. 1994:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y. Active learning with support vector machine applied to gene expression data for cancer classification. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 2004;44(6):1936–1941. doi: 10.1021/ci049810a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warmuth MK, Liao J, Rätsch G, Mathieson M, Putta S, Lemmen C. Active learning with support vector machines in the drug discovery process. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 2003;43(2):667–673. doi: 10.1021/ci025620t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Figueroa RL, Zeng-Treitler Q, Ngo LH, Goryachev S, Wiechmann EP. Active learning for clinical text classification: is it better than random sampling? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012 doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000648. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Nguyen DH, Patrick JD. Supervised machine learning and active learning in classification of radiology reports. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014 doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-002516. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/amiajnl-2013-002516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Chang CC, Lin CJ. LIBSVM: a library for support vector machines. ACM Trans Intell Syst Technol (TIST) 2011;2(3):27. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tong S, Koller D. Support vector machine active learning with applications to text classification. J Mach Learn Res. 2000–2001;2:45–66. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ralf H, Graepel T, Campbell C. Bayes point machines. J Mach Learn Res. 2001;1:245–279. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nissim N, Moskovitch R, Rokach L, Elovici Y. Novel active learning methods for enhanced PC malware detection in windows OS. Expert Syst Appl. 2014;41(13) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nissim N, Moskovitch R, Rokach L, Elovici Y. Detecting unknown computer worm activity via support vector machines and active learning. Pattern Anal Appl. 2012;15(4):459–475. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moskovitch R, Nissim N, Elovici Y. ACM SIGKDD Workshop in Privacy, Security and Trust in KDD. Las Vegas: 2008. Malicious code detection using active learning. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moskovitch R, Stopel D, Feher C, Nissim N, Japkowicz N, Elovici Y. Unknown malcode detection and the imbalance problem. J Comput Virol. 2009;5(4) [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nissim N, Cohen A, Moskovitch R, et al. ALPD: active learning framework for enhancing the detection of malicious PDF files aimed at organizations, in. Proceedings of JISIC. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baram Y, El-Yaniv R, Luz K. Online choice of active learning algorithms. J Mach Learn Res. 2004;5:255–291. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Herman R. 72 Statistics on Hourly Physician Compensation. 2013 http://www.beckershospitalreview.com/compensation-issues/72-statistics-on-hourly-physician-compensation.html accessed in January 2015.

- 44.Boland MR, Tatonetti NP. AMIA Summits on Translational Science Proceedings 2015. San Francisco, CA, USA: 2015. Are all vaccines created equal? Using electronic health records to discover vaccines associated with clinician-coded adverse events, in; pp. 196–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boland MR, Tatonetti NP, Hripcsak G. Intelligent Systems for Molecular Biology Phenotype Day. Boston, MA: 2014. CAESAR: a classification approach for extracting severity automatically from electronic health records, in. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vapnik V. Statistical Learning Theory. Springer; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boland MR, Tatonetti NP, Hripcsak G. Development and validation of a classification approach for extracting severity automatically from electronic health records. J Biomed Semantics. 2015;6(14) doi: 10.1186/s13326-015-0010-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moskovitch R, Cohen-Kashi S, Dror U, Levy I, Maimon A, Shahar Y. Multiple hierarchical classification of free-text clinical guidelines. Artif Intell Med. 2006;37:177–190. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nissim N, Boland MR, Moskovitch R, Tatonetti NP, Elovici Y, Shahar Y, Hripcsak G. An active learning framework for efficient condition severity classification, in. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine (AIME-15), Springer International Publishing. 2015:13–24. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vapnik VN. Estimation of Dependences Based on Empirical Data. Vol. 41. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Joachims T. Making large scale SVM learning practical. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burges CJ. A tutorial on support vector machines for pattern recognition. Data Min Knowl Disc. 1998;2(2):121–167. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berthold Michael. The fog of data: data exploration in the life sciences. Invited Talk at 11th AIME Conference. 2007 In Artificial Intelligence in Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cebron Nicolas, Berthold Michael R. Active learning for object classification: from exploration to exploitation. Data Min Knowl Discov. 2009 Jul 27;18(2):283–299. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moskovitch Robert, Hessing Alon, Shahar Yuval. Vaidurya – a concept-based, context-sensitive search engine for clinical guidelines, MedInfo 2004. San Francisco, USA: 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moskovitch Robert, Martins Suzana, Behiri Eytan, Weiss Aviram, Shahar Yuval. A comparative evaluation of a full-text, concept based, and context sensitive search engine. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14:164–174. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jensen PB, Jensen LJ, Brunak S. Mining electronic health records: towards better research applications and clinical care. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13(6) doi: 10.1038/nrg3208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bellazzi R, Zupan B. Predictive data mining in clinical medicine: current issues and guidelines. Int J Med Inform. 2008;77(2) doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Batal I, Fradkin D, Harrison J, Moerchen F, Hauskrecht M. Proceedings of Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD) Beijing, China: 2012. Mining recent temporal patterns for event detection in multivariate time series data, in. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moskovitch R, Shahar Y. Fast time intervals mining using transitivity of temporal relations. Knowl Inf Syst. 2015;42:1. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ng K, Ghoting A, Steinhubl SR, Stewart WF, Malin B, Sun J. PARAMO: a PARAllel predictive MOdeling platform for healthcare analytic research using electronic health records. J Biomed Inform. 2014;48:160–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sun J, McNaughton CD, Zhang P, Perer A, Gkoulalas-Divanis A, Denny JC, Kirby J, Lasko T, Saip A, Malin BA. Predicting changes in hypertension control using electronic health records from a chronic disease management program. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21:337–344. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-002033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hripcsak G. Physics of the Medical Record: Handling Time in Health Record Studies, Artificial Intelligence in Medicine. Pavia, Italy: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rana S, Gupta S, Phung D, Venkatesh S. A predictive framework for modeling healthcare data with evolving clinical interventions. Stat Anal Data Min: ASA Data Sci J. 2015;8(3):162–182. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moskovitch R, Shahar Y. Classification of multivariate time series via temporal abstraction and time intervals mining. Knowl Inf Syst. 2015;45(1):35–74. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moskovitch R, Shahar Y. Classification driven temporal discretization of multivariate time series. Data Min Knowl Disc. 2015;29(4):871–913. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Huang Z, Dong W, Bath P, Ji L, Duan H. On mining latent treatment patterns from electronic medical records. Data Min Knowl Disc. 2015;29:914–949. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nissim N, Moskovitch R, BarAd O, Rokach L, Elovici Y. ALDROID: efficient update of android anti-virus software using designated active learning methods. Knowl Inf Syst. 2016:1–39. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moskovitch R, Nissim N, Elovici Y. IEEE International Conference on Intelligence and Security Informatics (IEEE ISI-2007) Rutgers University; New Jersey, USA: 2007. Malicious code detection and acquisition using active learning. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nissim Nir, Cohen Aviad, Moskovitch Robert, Barad Oren, Edry Mattan, Shabatai Assaf, Elovici Yuval. ALPD: active learning framework for enhancing the detection of malicious PDF files, in: Intelligence and Security Informatics Conference (JISIC) 2014 IEEE Joint. 2014:91–98. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moskovitch R, Nissim N, Englert R, Elovici Y. The 11th International Conference on Information Fusion. Cologne, Germany: 2008. Detection of unknown computer worms activity using active learning, in. [Google Scholar]