Abstract

Background

Reduced reward responsiveness, measured via the event-related potential (ERP) component the reward positivity (RewP), has been linked to several internalizing psychopathologies (IPs). Specifically, prior studies suggest that a reduced RewP is robustly related to depression and to a lesser extent anxiety. No studies to date, however, have examined the relation between the RewP and IP symptom dimensions in a heterogeneous, clinically representative patient population that includes both depressed and/or anxious subjects. The primary aim of the current study was to examine the relation between the RewP and specific internalizing symptom dimensions among patients with a variety of IP diagnoses and symptoms.

Methods

A total of 80 treatment seeking adults from the community completed a battery of questionnaires assessing a range of IP symptoms and a well-validated reward processing task known to robustly elicit the RewP.

Results

A principal components analysis (PCA) on clinical assessments revealed two distinct factors that characterized the patient sample: affective distress/misery and fear-based anxiety. Results showed that within this sample, an attenuated RewP was associated with greater affective distress/misery based symptoms; however, the RewP was unrelated to fear-based anxiety symptoms.

Conclusions

The current findings suggest that patients with higher distress/misery symptoms are characterized by decreased responsivity to rewards at the physiological level, and that this response tendency distinguishes distress/misery symptoms from fear-based symptoms. The RewP may be one promising transdiagnostic biological target for intervention efforts for individuals with distress-based symptoms of psychopathology.

Keywords: reward positivity, internalizing symptoms, fear, distress, event-related potentials

Internalizing disorders, such as anxiety and depression, are highly comorbid and overlapping in symptoms (Kessler et al., 2005; Watson, 2005), and share many common biological and neurological underpinnings (e.g., Etkin, & Schatzberg, 2011; Tambs et al., 2009). Issues surrounding the categorical nature of internalizing psychopathologies (IPs) and overlap among them have been widely recognized (e.g., Regier et al., 2009; Sanislow et al., 2010). To address these matters, the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) initiative was developed by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in order to promote the development of dimensional constructs that integrate elements of psychology and biology (Kozak & Cuthbert, 2016). Specifically, the RDoC initiative seeks to move toward a personalized medicine approach and find novel ways of classifying psychiatric disorders that are based on dimensions of observable behavior and neurobiological measures (Cuthbert & Insel, 2011).

Several IPs are characterized by deficits in reward and effort valuation, reward outcome, and decision-making processes (e.g., Craske et al., 2016). As a result, RDoC identified a number of reward-related biologically based constructs within the Positive Valence System, including initial responsiveness to reward attainment. To examine reward responsiveness at the psychophysiological level, researchers have utilized the event-related potential (ERP) component the reward positivity (RewP). The RewP, previously referred to as the feedback negativity, is maximal at frontocentral electrode sites approximately 250–350 ms following the receipt of a reward and reflects processing of positive feedback (e.g., monetary reward) versus breaking even or losing (for reviews, see Proudfit, 2015; Proudfit et al., 2015). The RewP has demonstrated excellent psychometric properties (Bress et al., 2015a), and there is growing evidence that it is a valid measure of individual differences in reward processing, as it has been correlated with self-report reward sensitivity (Bress & Hajcak, 2013a), positive emotionality (Kujawa et al., 2015), and activation in brain regions implicated in reward, such as the ventral striatum and medial prefrontal cortex (Carlson et al., 2011; Foti et al., 2011; Gehring, & Willoughby, 2002).

Notably, the RewP has consistently been linked to IPs. The most robust finding in the literature is the relationship between an attenuated RewP and depression. For instance, less differentiation between gains and losses (i.e., a reduced RewP) has been shown to be related to concurrent symptoms of depression among youth (Bress et al., 2015b) and adults (Foti & Hajcak, 2009), and also future depressive symptoms and diagnoses among youth in a prospective study (Nelson et al., in press). An attenuated RewP to gains has also been observed in preschoolers (Belden et al., 2016) and adults (Liu et al., 2014) with depression, and shown to prospectively predict future depressive symptoms and diagnoses in children and adolescents (Bress et al., 2013b; 2015a).

Despite the common comorbidity between depression and anxiety (Kessler et al., 2005; Watson, 2005), fewer studies have examined the association between the RewP and anxiety, and findings have been less consistent relative to studies with depression. In one study of college undergraduates, a smaller RewP was associated with greater trait anxiety (Gu et al., 2010). Conversely, researchers failed to find a relation between the RewP and anxiety symptoms among children and adolescents (Bress et al., 2012; Bress et al., 2015b) and college undergraduates (Foti & Hajcak, 2009). In a study of children, however, youth with higher generalized anxiety symptoms exhibited an attenuated RewP to losses, whereas children with higher social anxiety symptoms in this study exhibited an enhanced RewP to gains (Kessel et al., 2015).

Taken together, prior studies suggest that a reduced RewP is robustly related to depression. However, findings from studies with anxious populations tend to be less consistent, and there is some evidence that different types of anxiety disorders (i.e., social anxiety versus generalized anxiety) may yield a different RewP response (i.e., attenuated versus enhanced). One interpretation from these previous studies is that an attenuated RewP response may not distinguish depression from anxiety, per se, but rather distress-misery versus fear disorders. Specifically, in large samples of patients with comorbid IPs (Hettema et al., 2005; Slade & Watson, 2006; Vollebergh et al., 2001), co-occurrence of disorders is usually best explained by two factors, including distress-misery (i.e., depression, dysthymia, and generalized anxiety) and fear-based anxiety (i.e., panic disorder, social phobia, specific phobia). However, the majority of prior studies examining the RewP and IPs have either focused on single IP diagnostic groups (e.g., Liu et al., 2014) or undergraduate college samples (e.g., Foti & Hajcak, 2009; Gu et al., 2010) making it difficult to directly test whether the RewP is more strongly associated with distress-misery versus fear-based anxiety symptoms. In order to adequately test this question, it is necessary to include a large heterogeneous sample of patients with depressive and anxiety disorders and thus, variable distress and fear-based symptoms. This type of investigation will ultimately assist with the RDoC initiative of finding novel ways to classify psychiatric disorders based on neurological measures (i.e., RewP). Moreover, examining these relationships in a representative sample of comorbid and treatment-seeking patients will also advance current understandings of the RewP as a potential tool for informing prevention or intervention efforts.

Thus, the primary aim of the current study was to examine the relation between the RewP and specific internalizing symptom dimensions within a clinically representative patient population with a variety of IP diagnoses and symptoms. The study included treatment-seeking adults with one or more current IP diagnoses and a range of IP symptoms. We first sought to replicate the previously demonstrated two-factor model of internalizing psychopathologies (i.e., fear-based anxiety and distress-misery) in a treatment-seeking population utilizing a principal components analysis (PCA) on several well-validated self-report measures of IPs. Consistent with previous studies (e.g., Belden et al., 2016; Bress et al., 2013b, 2015a, 2015b; Foti & Hajcak, 2009; Kessel et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2014), we hypothesized that less differentiation between gains and losses (i.e., the RewP) would be more strongly associated with symptoms of distress and misery, relative to fear-based symptoms of psychopathology. Specifically, we expected that there would be a negative relation between RewP and distress-misery symptoms, whereas there would be no relation between the RewP and fear-based symptoms of anxiety.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The current study was funded by, and designed to be consistent with, the NIMH RDoC Initiative (RFA-MH-13-080). Thus, the study was comprised of a clinically representative patient population, with a full range of IPs and symptoms who consented to treatment with pharmacotherapy (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors/SSRIs) or cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Participants were required to be between 18 and 65 and have a current full-threshold or sub-threshold DSM-5 depressive or anxiety disorder, report a total score of ≥23 on the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995), and a Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score of ≤60. Exclusionary criteria included an inability to provide consent and read and write in English, having a major active medical or neurological problem, a lifetime history of mania or psychosis, current OCD, a current substance dependence, a history of an intellectual disability or pervasive developmental disorder, any contraindication to receiving SSRIs, being already engaged in psychiatric treatment (including medication), a history of traumatic brain injury, and being pregnant. All subjects were free of psychotropic/psychoactive medications and tested negative on a urine drug screen at the time of screening. The University of Illinois at Chicago Institutional Review Board approved the study, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Eighty-seven patients were enrolled in the study; however, seven were excluded due to poor quality EEG data, defined as having fewer than 15 artifact-free trials per condition. The final sample included eighty individuals. All data used in the current study were collected at baseline, prior to treatment.

Assessment of Diagnoses

Lifetime Axis I diagnoses were assessed via the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders (SCID-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) by trained research staff. After the evaluation, a consensus panel of at least 3 study staff/trained clinicians determined subjects’ eligibility and if there were co-occurring disorders, the principal disorder warranting treatment was identified. Consistent with the RDoC strategy (Kozak & Cuthbert, 2016), individuals were not excluded for comorbid disorders but instead classified by their clinician-determined principal diagnosis, as determined by the most severe and impairing symptoms (see Table 1). Panic disorder (PD), social anxiety disorder (SAD), and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were coded as ‘fear-based disorders’ whereas major depressive disorder (MDD), dysthymia, and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) were coded as ‘distress/misery’ disorders consistent with our prior studies (Gorka et al., in press).

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of the sample.

| M (SD) or % (n = 80) | |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age (years) | 28.15 (9.1) |

| Sex (female) | 68.8% |

| Education (years) | 16.26 (3.3) |

| Race (Caucasian) | 70.0% |

| Clinical Variables | |

| Total Number of Current IPs (mean) | 2.49 (1.1) |

| Principal Fear IP | 31.3% |

| Principal Distress IP | 68.8% |

| MDD (Principal, Present) | 22.5%, 52.5% |

| Dysthymia (Principal, Present) | 3.8%, 16.3% |

| GAD (Principal, Present) | 35.0%, 66.3% |

| PTSD (Principal, Present) | 5.0%, 16.3% |

| SAD (Principal, Present) | 20.0%, 61.3% |

| PD (Principal, Present) | 2.5%, 25% |

| Reward Task Variables (Mean Amplitude) | |

| Gain | 15.77 (9.7) |

| Loss | 11.45 (8.7) |

| RewP | 4.32 (6.2) |

Note. IP = internalizing psychopathology; Fear disorders include panic disorder (PD), social anxiety disorder (SAD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD); Distress disorders include major depressive disorder (MDD), dysthymia, and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD); RewP = reward positivity.

Internalizing Symptom Measures

All participants completed a battery of standardized measures. By intention, some of the measures captured broad internalizing symptoms, whereas others were relatively specific to the principal disorders included in the sample.

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck et al., 1998)

The BAI is a 21-item scale that measures the severity of anxiety symptoms over the past two weeks using a 0–3 scale. Items are summed to produce a total score.

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996)

The 21-item BDI-II is a measure of depressive symptoms over the past two weeks. Respondents rate each depressive symptom on a 0–3 scale to create a total score.

Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995)

The DASS-21 is comprised of 21-items and three subscales measuring symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress. Respondents rate the severity of each symptom during the past week on a 0–3 scale.

Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A; Hamilton, 1959)

The HAM-A is a 14-item clinician-administered measure of anxiety symptom severity. Items are coded on a 0–4 scale to create a total score.

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D; Hamilton, 1960)

The HAM-D is also clinician-administered and includes 21-items assessing severity of current depressive symptoms. Items are coded on a 0–4 scale to produce a total score.

Inventory for Depression and Anxiety Symptoms-II (IDAS-II; Watson et al., 2012)

The IDAS-II includes 99 items assessing IP symptoms during the previous two weeks. Participants rate each item using a 1–5 scale. Scores are summed to create 18 distinct scales: depression, dysphoria, lassitude, insomnia, suicidality, appetite gain, appetite loss, ill-temper, well-being, panic, social anxiety, claustrophobia, euphoria, mania, traumatic intrusions, traumatic avoidance, and tendencies for checking, ordering and cleaning.

Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS; Liebowitz, 1987)

The LSAS is a 24-item scale of social phobia symptoms. Responses are made on a 0–3 scale. Two LSAS subscales were created: total fear/anxiety and total avoidance.

Overall Depression Severity and Impairment Scale (ODSIS; Bentley et al., 2014)

The 5-item ODSIS measures the severity of current depressive symptoms and level of functional impairment on a 0–4 scale. Items are summed to create a total score.

Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (OASIS; Norman et al., 2006)

The OASIS is a 5-item scale assessing anxiety severity and related impairment. Responses are made on a 0–4 scale and items are summed to create a total score.

Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS; Shear et al., 1997)

The PDSS is a 7-item scale assessing the frequency, severity, and functional impairment associated with panic disorder and panic attacks. Responses are made on a 0–4 scale and summed to create a total score.

Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ; Meyer et al., 1990)

This instrument contains 16 items that measure trait levels of worry. Each item is scored from 1–5 to produce a total score.

Ruminative Response Styles Scale (RRS; Treynor et al., 2003)

The RRS includes 22-items measuring depressive rumination styles. Participants rate the extent to which they typically engage in each ruminative response on a 1–4 scale. Responses are summed to create a total score.

State Trait Anxiety Inventory – Trait Subscale (STAI-T; Spielberger et al., 1990)

The STAI-T is a subscale of the STAI that includes 20-items assessing trait anxiety. Responses are made on a 1–4 scale and summed to create a total score.

Data Reduction

A principal components analysis (PCA) was conducted using each of the measures described above in order to identify unique symptom dimensions and reduce the number of measures for each participant. The IDAS subscales assessing symptoms of mania and OCD-like behaviors were omitted from the PCA due to the fact that diagnoses of bipolar disorder and OCD were exclusionary and relatedly, these subscales were skewed (all skew values >1.5). For the PCA, direct oblimin rotation was used, permitting correlation between components. The PCA analysis resulted in two factors with eigenvalues greater than two and explaining 41.7% of the variance. The two factors were correlated (r = .19) and reflected: 1) affective distress-misery (λ=6.51; 23.2% of variance) and 2) fear-based anxiety (λ=4.85; 17.3% of variance). The factor loadings for individual questionnaires are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Questionnaire factor loadings across patients.

| Scale/Subscale | Component 1: Distress/Misery | Component 2: Fear-based Anxiety | Internal Consistency (α) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IDAS Dysphoria | .81 | −.32 | .74 |

| RRS Total | .71 | −.33 | .92 |

| BDI Total | .67 | −.45 | .87 |

| ODSIS Total | .66 | −.56 | .92 |

| STAI-T Total | .68 | −.22 | .85 |

| IDAS Lassitude | .58 | −.34 | .77 |

| DASS Depression | .53 | −.61 | .88 |

| HAM-D Total | .56 | −.22 | .64 |

| HAM-A Total | .63 | .32 | .72 |

| IDAS Well-Being | −.51 | .55 | .87 |

| OASIS Total | .51 | .39 | .81 |

| PSWQ Total | .49 | .28 | .89 |

| IDAS Intrusions | .40 | .11 | .66 |

| IDAS Temper | .42 | .12 | .85 |

| IDAS Suicidality | .37 | −.28 | .81 |

| IDAS Insomnia | .32 | .00 | .86 |

| IDAS Appetite Loss | .30 | .06 | .80 |

| IDAS Avoidance | .31 | .02 | .87 |

| IDAS Appetite Gain | .11 | −.07 | .91 |

| DASS Anxiety | .19 | .77 | .77 |

| IDAS Panic | .34 | .69 | .79 |

| PDSS Total | .45 | .61 | .89 |

| BAI Total | .46 | .63 | .89 |

| IDAS Social Anxiety | .38 | .51 | .83 |

| DASS Stress | .38 | .39 | .68 |

| IDAS Claustrophobia | .29 | .46 | .84 |

| LSAS Anxiety | .30 | .45 | .92 |

| LSAS Avoidance | .35 | .38 | .90 |

Note. IDAS = Inventory of Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms; RRS = Ruminative Response Styles; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory-II; ODSIS = Overall Depression Severity and Impairment Scale; DASS = Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale; STAI-T = State Trait Anxiety Inventory – Trait Subscale; HAM-A = Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; HAM-D = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; OASIS = Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale; PSWQ = Penn State Worry Questionnaire; PDSS = Panic Disorder Severity Scale; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory; LSAS = Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale. Factor loadings greater than .45 are bolded.

Reward Task

Participants completed a computerized guessing task that consisted of 40 trials. On each trial, participants were asked to choose one of two doors shown side by side on a computer monitor; the graphic remained visible until a choice was made. A fixation mark then appeared for 1000 ms, followed by feedback screen for 2000 ms. Feedback consisted of either a green “↑”, indicating a gain of $0.50, or a red “↓”, indicating a loss of $0.25; these amounts were chosen to give gains and losses equivalent subjective values (Tversky & Kahneman, 1992). After receiving feedback, a fixation mark was presented for 1500 ms, followed by a screen reading “Click for the next round,” which remained onscreen until participants responded. Participants received 20 trials each of gain and loss feedback, presented in a random order.

EEG Data Acquisition and Processing

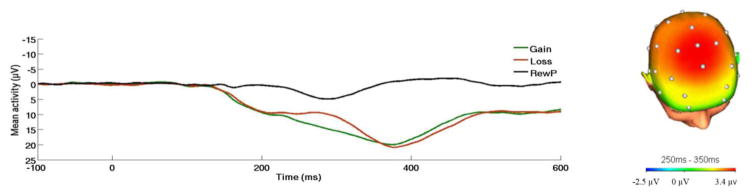

Continuous EEG was recorded during the task using an elastic cap and the ActiveTwo BioSemi system (BioSemi, Amsterdam, Netherlands). Thirty-four standard electrode sites were used. One electrode was placed on each mastoid. The EEG signal was pre-amplified at the electrode to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. The data were digitized at 24-bit resolution with a Least Significant Bit (LSB) value of 31.25nV and a sampling rate of 1024Hz, using a low-pass fifth order sinc filter with a −3dB cutoff point at 204.8Hz. Off-line analyses were performed using Brain Vision Analyzer 2 software (Brain Products, Gilching, Germany). Data were re-referenced to the average of the two mastoids and high-pass (0.1Hz) and low-pass (30Hz) filtered. Standard eyeblink and ocular corrections were performed (Miller, Gratton & Yee, 1988) and semiautomated artifact rejection procedures removed artifacts with the following criteria: voltage step of more than 50 μV between sample points, a voltage difference of 300 μV within a trial, and a maximum voltage difference of less than 0.5 μV within 100 ms intervals. Additional artifacts were removed using visual inspection. Data were baseline corrected using the 100 ms interval prior to feedback. ERPs were averaged across gain and loss trials, and the RewP was scored as the mean amplitude 250–350 ms following feedback at a pooling of frontal sites (FCz and Fz), where the gain minus loss difference was maximal (Fig. 1). The mean number of artifact-free trials for FCz and Fz in each condition was 19.46 (SD = 1.92). Consistent with previous research (for reviews, see Proudfit, 2015; Proudfit et al., 2015), analyses focused on the gain minus loss difference score (RewP); more positive values for the difference score indicate greater reactivity to reward. Analyses were also computed to evaluate effects on loss or gain trials individually.

Figure 1.

On the left, response-locked ERP waveform for gain and loss trials, as well as the difference waves (reward positivity; RewP) across the entire sample (n = 80). On the right, topographic map of activity (gain minus loss) across the entire sample.

Results

Demographics and Descriptives

Demographic and descriptive statistics of the sample are presented in Table 1. The patients had a high rate of comorbid diagnoses, which is reflected by 78.8% of the adults having co-occurring IPs and participants having an average of 2.5±1.1 IP diagnoses. There were no differences in number of diagnoses or current symptom severity/impairment (assessed via the Global Assessment of Functioning [GAF] during the SCID) between individuals with principal distress/misery and fear disorders.

RewP and Symptom Dimensions

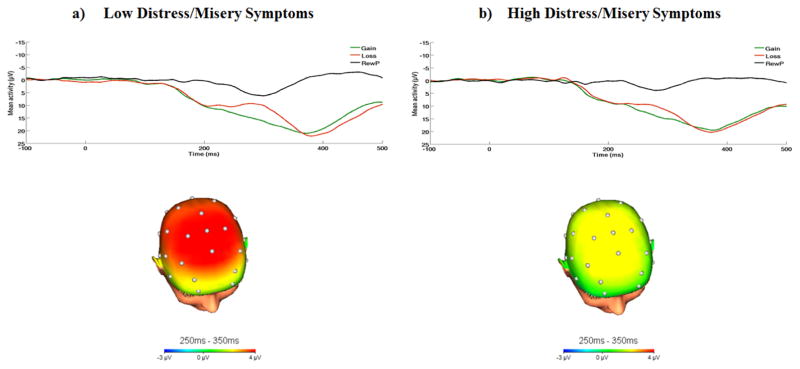

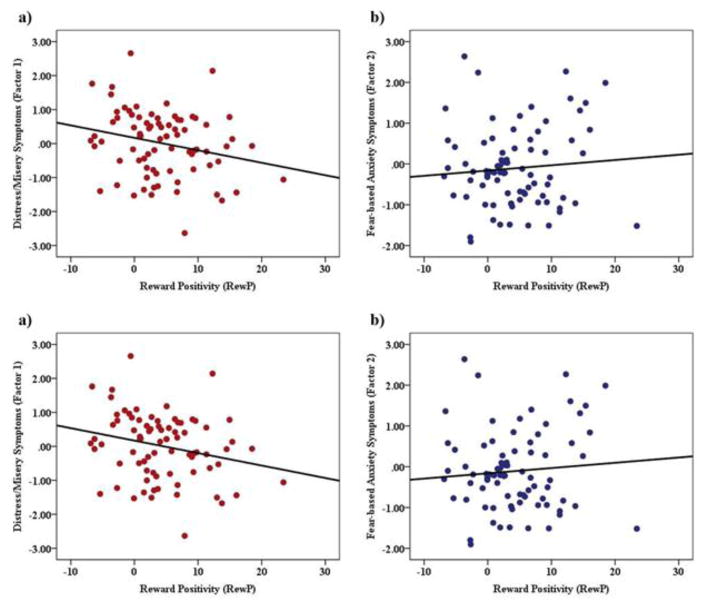

Across all participants, the response to gains was significantly more positive compared to the response to losses, t(79) = 6.19, p < .001 (gains: M = 15.77 μV, SD = 9.62 μV; losses: M = 11.44 μV, SE = 8.71 μV). Next, we tested the effect of RewP on each factor using linear regression analyses. Results revealed a significant negative relation between the RewP and distress/misery symptoms, such that individuals with greater distress/misery symptoms (i.e., factor 1) exhibited a greater reduction in the RewP, β =−0.24, t = −2.17, p = 0.03, r = −.24. Notably, this relation remained significant after adjusting for current GAF scores among patients, p < .05, r = −.23, suggesting that this effect was partially independent of patient’s current functioning levels. To illustrate these results, waveforms and scalp topographies depicting differences in mean amplitude (μV) from 250ms–350ms for gain minus loss responses for individuals with low and high distress/misery symptoms (based on median split) are displayed in Figure 2. Results revealed that the relation between the RewP and fear-based anxiety symptoms (i.e., factor 2) was non-significant, β = 0.08, t= 0.73, p = 0.47, r = .47.1 The scatter-plots depicting the relation between the two factors and RewP are depicted in Figure 3.2 Neither the ERP response to gains alone or losses alone was associated with distress/misery or fear-based anxiety symptoms (ps > .19).

Figure 2.

On the top, response-locked ERP waveforms for gain and loss trials, as well as the difference waves (reward positivity; RewP) and on the bottom, topographic maps of activity (gain minus loss) for individuals with a) low (n = 40) and b) high (n = 40) distress/misery symptoms (defined by a median split for Factor Component 1).

Figure 3.

Scatter plot depicting the association between RewP and a) distress/misery symptoms (factor 1) and b) fear-based anxiety symptoms (factor 2).

Exploratory analyses were conducted to determine whether patient age or sex moderated the relation between RewP and symptom dimensions. The repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of patient sex, F(1, 76) = 8.41, p < 0.01, np2 = 0.10, such that females had higher IP symptoms than males. However, results revealed no other significant main effects or interactions (ps > 0.20).

Finally, we conducted additional exploratory analyses to examine the influence of patient’s diagnostic history on the RewP. Specifically, we examined whether principal distress/misery and fear disorders were related to the RewP. Results revealed a non-significant trend, such that patients with primary distress and misery disorders (M = 3.48, SD = 5.20) exhibited a more attenuated RewP, relative to patients with primary fear disorders (M = 6.27, SD = 7.97), t(78) = −1.85, p = .07, r = −.21. Notably, the relation between the distress/misery factor and RewP remained significant when adjusting for primary fear/distress diagnosis (p = .03).

Discussion

The current study sought to examine the relation between the RewP and specific internalizing symptom dimensions within a clinically representative patient population seeking treatment for depression and anxiety. Utilizing PCA analyses, the current study found that a two-factor solution consisting of distress/misery and fear-based anxiety best characterized the current sample. This two-factor profile is consistent with several previous factor analytic and family studies providing additional evidence that IP disorders cluster into separate and discrete distress/misery and fear factors (Hettema et al., 2005; Slade & Watson, 2006; Vollebergh et al., 2001). Results from the current study also suggest that an attenuated RewP is associated with greater distress/misery symptoms and is not significantly related to fear-based anxiety symptoms. These findings indicate that the RewP distinctly tracks distress/misery symptoms and may serve as an objective, biological assay of distress-based psychopathology.

The current findings are consistent with our initial hypotheses and prior literature. As previously discussed, the RewP has been robustly linked to depressive symptoms and diagnoses among young children and adults (e.g., Bress et al., 2013b, 2015a, 2015b; Belden et al., 2016; Foti & Hajcak, 2009; Liu et al., 2014). In the current sample, depressive symptoms (e.g., BDI, IDAS dysphoria, lassitude) had the highest loading on the distress/misery factor but the factor also included symptoms of worry and trait anxiety. Our findings fit with previous studies showing that the RewP is negatively related to generalized anxiety symptoms in youth (Kessel et al., 2015) and trait anxiety in adults (Gu et al., 2015). These results suggest that the RewP may not be specific to pure depression and may extend more broadly across the distress/misery spectrum. At the same time, we found that the RewP was not related to fear-based anxiety symptoms. Notably, several studies show that the RewP is not related to anxiety symptoms when using self-report measures of anxiety that encompass several anxiety disorders (Bress et al., 2012; Bress et al., 2015b; Foti & Hajcak, 2009). Thus, the current results highlight the utility of separating out fear-based versus distress/misery symptoms of psychopathology and add to a growing body of literature indicating that affective distress-based psychopathology is characterized by decreased responsivity to reward and that this phenotypical profile may distinguish distress/misery from fear-based psychopathology.

Importantly, this attenuated response to reward at the psychophysiological level may be a useful transdiagnostic target for prevention or intervention efforts. Specifically, a blunted RewP has been observed among preschoolers with depression (Belden et al., 2016), and shown to predict the onset of depressive symptoms and diagnoses in youth (Bress et al., 2013; Nelson et al., in press) suggesting that it is a trait-like vulnerability factor. Given this, the RewP may be an economical and brain-based target for screening and prevention efforts. In the context of the current study, psychiatric treatments that target reward responsivity may prove to be the most beneficial for individuals with a range of affective distress-based symptoms. A reduced RewP may indicate a deficient reward sensitivity system that diminishes an individual’s tendency to engage in approach-oriented behaviors (e.g., pursue pleasant activities). Therefore, interventions that are comprised of behavioral activation or distress-based exposures may prove to be the most beneficial treatment for patients who present with reward processing deficits. We also recently demonstrated that a more blunted RewP among adult patients with depression and anxiety predicted greater treatment gains with cognitive behavior therapy (Burkhouse et al., 2016), supporting the notion that this measure can also be useful in identifying those most likely to benefit from intervention. Future research would benefit from examining whether the RewP also demonstrates state-like properties and can be altered through treatment or environmental factors (i.e., stress).

There were limitations to the current study, which provide important avenues for future research. First, the sample included individuals with a range of IP diagnoses but some principal disorders were under-represented (i.e., specific phobia and panic disorder). Moreover, the current study had a larger number of principal distress-based versus fear-based disorders. Therefore, future studies would benefit from validating these results in a larger IP sample with a balanced range of IP questionnaires and diagnoses. Next, the sample size of the current study is considered small for PCA analysis and the two observed factors only accounted for approximately 42% of the symptom variance in the sample, which suggests that there may be other important symptoms dimensions not captured in the current analyses. Therefore, future larger studies would benefit from considering not only relations regarding fear vs. distress/misery but also other unique symptom profiles. Next, although the RewP has been suggested as a good candidate measure of the positive valence system construct of reward responsiveness (for a review, see Proudfit, 2012), future research is needed to determine whether the RewP indexes other subconstructs of the positive valence system (e.g., reward valuation, initial reward learning). This would help to identify which psychological treatments may be most successful and precise in targeting the RewP to reduce distress-based symptoms. Lastly, given the highly comorbid nature of the sample, we did not have the power to test differences in the RewP across specific IP diagnoses (i.e., depression, social anxiety, etc.). Although the design of the current study was dimensionally focused, it may also be useful to determine whether a reduced RewP is categorically specific for distress versus fear disorders.

The current findings suggest that patients with higher distress/misery symptoms are characterized by an attenuated RewP response, and that this response tendency distinguishes distress/misery symptoms from fear-based symptoms. These results complement previous studies suggesting that distress-based symptoms of psychopathology are characterized by reduced responsivity to reward, and contribute to the RDoC initiative by linking physiologic and self-report dimensional units in a broad clinical sample. This deficit in reward sensitivity at the psychophysiological level may be one promising transdiagnostic target for prevention or intervention efforts for individuals with greater distress-based symptoms of psychopathology.

Highlights.

The current study examined the relation between the RewP and specific internalizing symptom dimensions among a heterogeneous patient sample.

A principal components analysis (PCA) on clinical assessments revealed two distinct factors that characterized the sample: affective distress/misery and fear-based anxiety.

An attenuated RewP was associated with greater affective distress/misery based symptoms, but the RewP was unrelated to fear-based anxiety symptoms.

The RewP may be one promising transdiagnostic biological target for intervention efforts for individuals with distress-based symptoms of psychopathology.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health grant R01MH101497 (to KLP) and Center for Clinical and Translational Science (CCTS) UL1RR029879. KLB is supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant T32- MH067631 (Training in the Neuroscience of Mental Health; PI: Mark Rasenick).

Footnotes

We also examined whether there was an interaction between distress/misery and fear symptoms in predicting the RewP. However, this analysis was not significant (p = .97).

When removing one participant with a high leverage RewP data point (i.e., RewP > 20), the significant effects were maintained and the pattern of results was identical.

Author Contributions

K. L. Burkhouse, S. Gorka, and K. L. Phan developed the initial study concept and design. K.L. Burkhouse, S. Gorka, K. Afshar, and K. L. Phan developed and analyzed study hypotheses. K.L. Burkhouse had primary responsibility for drafting the paper. All authors revised the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belden AC, Irvin K, Hajcak G, Kappenman ES, Kelly D, Karlow S, … Barch DM. Neural Correlates of Reward Processing in Depressed and Healthy Preschool-Age Children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2016;55(12):1081–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.09.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley KH, Gallagher MW, Carl JR, Barlow DH. Development and validation of the Overall Depression Severity and Impairment Scale. Psychological Assessment. 2014;26(3):815–830. doi: 10.1037/a0036216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bress JN, Foti D, Kotov R, Klein DN, Hajcak G. Blunted neural response to rewards prospectively predicts depression in adolescent girls. Psychophysiology. 2013b;50(1):74–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2012.01485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bress JN, Hajcak G. Self-report and behavioral measures of reward sensitivity predict the feedback negativity. Psychophysiology. 2013a;50(7):610–616. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bress JN, Meyer A, Hajcak G. Differentiating anxiety and depression in children and adolescents: Evidence from event-related brain potentials. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2015b;44(2):238–249. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.814544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bress JN, Meyer A, Proudfit GH. The stability of the feedback negativity and its relationship with depression during childhood and adolescence. Development and psychopathology. 2015a;27:1285–1294. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414001400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhouse KL, Kujawa AK, Kennedy AE, Shankman SA, Langenecker SA, Phan KL, Klumpp H. Neural reactivity to reward as a predictor of cognitive behavioral therapy response in anxiety and depression. Depression and Anxiety. 2016;33:281–288. doi: 10.1002/da.22482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson JM, Foti D, Mujica-Parodi LR, Harmon-Jones E, Hajcak G. Ventral striatal and medial prefrontal BOLD activation is correlated with reward-related electrocortical activity: a combined ERP and fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2011;57(4):1608–1616. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Meuret AE, Ritz T, Treanor M, Dour HJ. Treatment for anhedonia: A neuroscience driven approach. Depression and Anxiety. 2016;33:927–938. doi: 10.1002/da.22490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert BN, Insel TR. Toward the future of psychiatric diagnosis: The seven pillars of RDoC. BMC medicine. 2013;11:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin A, Schatzberg AF. Common abnormalities and disorder-specific compensation during implicit regulation of emotional processing in generalized anxiety and major depressive disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168(9):968–978. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10091290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foti D, Hajcak G. Depression and reduced sensitivity to non-rewards versus rewards: Evidence from event-related potentials. Biological psychology. 2009;81(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foti D, Weinberg A, Dien J, Hajcak G. Event-related potential activity in the basal ganglia differentiates rewards from nonrewards: Temporospatial principal components analysis and source localization of the feedback negativity. Human brain mapping. 2011;32(12):2207–2216. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring WJ, Willoughby AR. The medial frontal cortex and the rapid processing of monetary gains and losses. Science. 2002;295(5563):2279–2282. doi: 10.1126/science.1066893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorka SM, Lieberman L, Shankman SA, Phan KL. Startle potentiation to uncertain threat as a psychophysiological indicator of fear-based psychopathology: An examination across multiple internalizing disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. doi: 10.1037/abn0000233. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton G, Coles MG, Donchin E. A new method for off-line removal of ocular artifact. Electroencephalogram Clinical Neurophysiology. 1983;55:468–484. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(83)90135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu R, Huang YX, Luo YJ. Anxiety and feedback negativity. Psychophysiology. 2010;47:961–967. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2010.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry JD, Crawford JR. The 21-item version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Normative data and psychometric evaluation in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;44:227–239. doi: 10.1348/014466505X29657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. The assesment of anxiety states by rating. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1959;32:50–55. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, & Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema JM, Prescott CA, Myers JM, Neale MC, Kendler KS. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for anxiety disorders in men and women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(2):182–189. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.2.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessel EM, Kujawa A, Hajcak Proudfit G, Klein DN. Neural reactivity to monetary rewards and losses differentiates social from generalized anxiety in children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2015;56(7):792–800. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak MJ, Cuthbert BN. The NIMH research domain criteria initiative: Background, issues, and pragmatics. Psychophysiology. 2016;53(3):286–297. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa A, Proudfit GH, Kessel EM, Dyson M, Olino T, Klein DN. Neural reactivity to monetary rewards and losses in childhood: Longitudinal and concurrent associations with observed and self-reported positive emotionality. Biological psychology. 2015;104:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebowitz MR. Social phobia. Modern Problems of Pharmacopsychiatry. 1987;22:141–173. doi: 10.1159/000414022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu WH, Wang LZ, Shang HR, Shen Y, Li Z, Cheung EF, Chan RC. The influence of anhedonia on feedback negativity in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychologia. 2014;53:213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. Manual for the depression anxiety stress scale. 2. Psychology Foundation; Sydney: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, Borkovec TD. Development and validation of the Penn State worry questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1990;28(6):487–495. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson BD, Perlman G, Klein DN, Kotov R, Hajcak G. Blunted Neural Response to Rewards as a Prospective Predictor of the Development of Depression in Adolescent Girls. American Journal of Psychiatry. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15121524. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman SB, Hami Cissell S, Means-Christensen AJ, Stein MB. Development and validation of an overall anxiety severity and impairment scale (OASIS) Depression and Anxiety. 2006;23(4):245–249. doi: 10.1002/da.20182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudfit GH. The reward positivity: From basic research on reward to a biomarker for depression. Psychophysiology. 2015;52(4):449–459. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudfit GH, Bress JN, Foti D, Kujawa A, Klein DN. Depression and event-related potentials: emotional disengagement and reward insensitivity. Current opinion in psychology. 2015;4:110–113. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2014.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Narrow WE, Kuhl EA, Kupfer DJ. The conceptual development of DSM-V. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;6:645–650. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09020279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanislow CA, Pine DS, Quinn KJ, Kozak MJ, Garvey MA, Heinssen RK, … Cuthbert BN. Developing constructs for psychopathology research: Research domain criteria. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119(4):631–639. doi: 10.1037/a0020909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear MK, Brown TA, Barlow DH, Money R, Sholomskas DE, Woods SW, … Papp LA. Multicenter collaborative panic disorder severity scale. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154(11):1571–1575. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade TIM, Watson D. The structure of common DSM-IV and ICD-10 mental disorders in the Australian general population. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36(11):1593–1600. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Self-Evaluation Questionnaire) Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Tambs K, Czajkowsky N, Røysamb E, Neale MC, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Aggen SH, … Kendler KS. Structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for dimensional representations of DSM–IV anxiety disorders. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;195(4):301–307. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.059485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treynor W, Gonzalez R, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27:247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 1992;5:297–323. [Google Scholar]

- Vollebergh WAM, Iedema J, Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Smit F, Ormel J. The structure and stability of common mental disorders: The NEMESIS study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:597–603. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D. Rethinking the mood and anxiety disorders: a quantitative hierarchical model for DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114(4):522–536. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]