Abstract

Background

Despite the high prevalence of childhood sexual abuse (CSA) among men who have sex with men (MSM) and its well-documented association with substance use in adulthood, little research has examined the psychological mechanisms underlying this association. The current study utilized a large, multinational sample of MSM in Latin America to examine the role of distress intolerance (i.e., decreased capacity to withstand negative psychological states) in the relationship between childhood sexual abuse history and problematic alcohol use.

Methods

As part of an online survey conducted among members of the largest social/sexual networking website for MSM in Latin America, participants (N = 19,451) completed measures of childhood sexual abuse history, distress intolerance, and problematic alcohol use (CAGE score >= 2).

Results

Participants who reported a history of childhood sexual abuse indicated higher levels of distress intolerance, which was in turn associated with greater odds of engaging in problematic alcohol use. A mediation analysis further showed that distress intolerance partially accounted for the significant association between childhood sexual abuse history and problematic alcohol use.

Conclusion

These findings provide initial evidence for the role of distress intolerance as a process through which early trauma shapes MSM health later in life. These findings also underscore the potential utility of addressing distress intolerance in alcohol use prevention and intervention efforts that target MSM with a history of childhood sexual abuse.

Keywords: childhood sexual abuse, distress intolerance, alcohol use, MSM

1 Introduction

A high prevalence of childhood sexual abuse (CSA) has been consistently documented among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM). Compared with the general male population, MSM are two to four times as likely to experience CSA, with rates closer to those of heterosexual women than heterosexual men (Lloyd and Operario, 2012; Mimiaga et al., 2009; Paul et al., 2001; Schafer et al., 2013). Such pervasive early trauma has a wide range of adverse long-term health consequences. For example, among MSM in the United States, those who were sexually abused as children reported greater depressive symptoms and were more likely to engage in substance use and sexual risk-taking than MSM who were not sexually abused as children (Boroughs et al., 2015; Lloyd and Operario, 2012; Marshall et al., 2015; Mimiaga et al., 2009). These findings have been replicated among MSM from Latin America (Carballo-Diéguez et al., 2012; Mimiaga et al., 2015a), where MSM routinely face high rates of discrimination and lifelong adversity associated with their sexual orientation (Geibel et al., 2010). Despite these well-documented associations, little research has examined the psychological mechanisms underlying the relationship between CSA history and poor health behaviors among MSM. This limitation is noteworthy given that CSA history is considered part of a syndemic of co-occurring psychosocial factors that contribute to MSM’s vulnerability to HIV (Mimiaga et al., 2015b) and that has been identified as a major public health concern (Halkitis et al., 2013). A better understanding of the processes through which CSA experiences operate to adversely influence MSM health would significantly inform HIV prevention efforts targeting this population. The present research, utilizing a large, multinational sample of MSM in Latin America, examined the role of distress intolerance (i.e., decreased capacity to withstand negative psychological states) as a potential mediator underlying the association between CSA history and problematic alcohol use.

Distress intolerance shapes various aspects of emotional and behavioral regulation, including attention deployment, appraisals of distress, and modulation of responses to distress (Leyro et al., 2010; Simons and Gaher, 2005). Specifically, individuals high in distress intolerance tend to perceive the experience of emotional distress as unbearable and unacceptable; as a result, they are often inclined to engage in impulsive, avoidant coping strategies in order to rapidly alleviate any emotional distress. Across a number of studies, distress intolerance has been identified as a significant predictor of substance use. For example, distress intolerance was prospectively associated with alcohol-related problems among male social drinkers, even after controlling for negative affect and alcohol problems at baseline (Simons and Gaher, 2005). Furthermore, distress intolerance has been linked to problematic alcohol use among both college students experiencing depressive symptoms (Buckner et al., 2007) and HIV-positive individuals (O’Cleirigh et al., 2007).

Although limited research has examined the developmental origins of distress intolerance, a general tendency to avoid negative emotional states has been observed among adult CSA survivors. For example, individuals with a CSA history reported greater avoidance of aversive thoughts and feelings (Marx and Sloan, 2002) and demonstrated lower perseverance on psychologically distressing laboratory tasks (Gratz et al., 2007) than those without such a history. This inclination to engage in emotional avoidance has important psychological and behavioral implications. As explained by Polusny and Follette (1995), CSA survivors tend to engage in a wide range of maladaptive coping strategies, including substance use, risky sexual behaviors, and self-injury, in order to suppress and distract themselves from the intense, aversive internal experiences associated with abuse-related affective states and memories. Of particular relevance to the present research, numerous studies utilizing both community and clinical samples have documented increased alcohol consumption and elevated rates of alcohol-related problems among women with CSA histories relative to their non-abused counterparts (see Sartor et al., 2008, for a review). Furthermore, young adult women with CSA histories were more likely to engage in alcohol use as a means to alleviate emotional distress than their non-abused peers (Goldstein et al., 2010; Hannan et al., 2015).

The present research extends previous work on the correlates and consequences of CSA by examining the associations among CSA history, distress intolerance, and problematic alcohol use among a multinational sample of gay, bisexual, and other MSM in Latin America. Although research on MSM health has consistently identified CSA as a risk factor for substance use in both U.S. and Latin American samples (Boroughs et al., 2015; Mimiaga et al., 2015a; Mimiaga et al., 2009; Paul et al., 2001), little empirical research to date has examined the mechanisms underlying this association. Given that MSM are disproportionately exposed to CSA (e.g., Paul et al., 2001) and a high prevalence of problematic alcohol use has been reported among Latin American MSM (Balán et al., 2013; Vagenas et al., 2013), an examination of the processes through which such trauma shapes the drinking behaviors of MSM can facilitate our understanding of how CSA influences the mental and behavioral health of MSM in adulthood. Drawing from previous findings linking CSA experiences to emotional avoidance (Gratz et al., 2007; Marx and Sloan, 2002), we hypothesized that MSM with CSA histories would have higher distress intolerance than those without such histories. Furthermore, given that individuals with higher distress intolerance are more inclined to engage in avoidant coping strategies such as substance use (Buckner et al., 2007; O’Cleirigh et al., 2007; Simons and Gaher, 2005), we hypothesized that distress intolerance would be positively associated with problematic alcohol use, even after controlling for CSA history. Lastly, in line with the proposition that early exposure to trauma and adversity associated with one’s sexual orientation might adversely impact MSM's health through its association with emotional avoidance (Pachankis, 2015), we proposed that distress intolerance would partially account for the association between CSA status and problematic alcohol use among the MSM sampled.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Participants and Procedures

From October to November 2012, members of one of the largest Internet sites for men seeking social or sexual interactions with other MSM in Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking countries in Latin America were sent an e-mail recruitment message to complete a survey related to sexual health. The recruitment email, which was sent to members by the website administrator, included a description of the study purpose and a link to the study website. Upon visiting the study website, individuals were able to read a more detailed description of the study procedures and, if interested, proceed to the study consent form.

Those who decided to participate were able to move directly from the consent form to the study questionnaire, completion of which took approximately 28 minutes. To minimize duplicate responses, we programmed the survey to allow access only from a unique Internet provider address on a single occasion. We did not provide any incentive for study participation. The recruitment message remained in each individual’s e-mail box for 30 days. Additional details of this study have been published elsewhere (Mimiaga et al., 2015a).

For this analysis, we limited the analytic sample to respondents who reported living in any Latin American country, male sex at birth and currently identified as a male, as well as those who reported having had sex with another man in the past year. A complete case analysis was conducted for participants who had valid responses for the primary variables of interest (i.e., childhood sexual abuse, distress intolerance, and problematic alcohol use), leaving a final analytic sample of 19,451. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Fenway Institute at Fenway Health in Boston, MA.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Childhood sexual abuse (CSA)

CSA history was assessed using measures previously developed to assess childhood sexual abuse among U.S. MSM (Mimiaga et al., 2009). Participants were asked a series of eight questions regarding experiences of unwanted or forced sexual touching or intercourse with a person when they were 17 years old or younger. Questions included items such as, “Before your 13th birthday, did an adult or someone at least five years older than you ever have sexual intercourse (including vaginal or anal intercourse) with you when you did not want this?; Before your 13th birthday, did an adult or someone at least five years older than you ever make you touch the sex organs of their body when you did not want this?; Since your 13th birthday and before your 17th birthday, did anyone (of any age) ever touch the sex organs of your body by using force or threatening to harm you?”; “Since your 13th birthday and before your 17th birthday, did anyone (of any age) ever make you touch the sex organs of their body by using force or threatening to harm you?” CSA history was coded dichotomously such that participants responding yes to any of the eight questions were considered to have experienced one or more form of childhood sexual abuse.

2.2.2 Problematic alcohol use

Problematic alcohol use was assessed using the CAGE Questionnaire (Ewing, 1984; Fiellin et al., 2000), a brief screening instrument for detecting problematic alcohol use commonly used in primary care settings. Participants indicated “yes:” or “no” to four questions, including “Have you ever felt you should cut down on your drinking?”, “Have people annoyed you by criticizing you on your drinking?”, “Have you ever felt bad or guilty by your drinking?”, and “Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning to steady your nerves or to get rid of a hangover?” Scores range from 0 to 4, with a score of 2 or higher (i.e., two or more positive responses) indicating problematic alcohol use.

2.2.3 Distress intolerance

Distress intolerance was assessed using four items from the 15-item Distress Tolerance Scale (Simons and Gaher, 2005). Designed to assess individual differences in the capacity to withstand negative psychological states, the original measure consists four subscales: Tolerance (i.e., the perceived ability to tolerate emotional distress), Appraisal (i.e., subjective appraisal of distress), Absorption (i.e., attention being absorbed by negative emotions), and Regulation (i.e., regulation efforts to alleviate distress). In order to minimize response burden, the subscale item with the highest factor loading in the original validation study (Simons and Gaher, 2005) was selected from each of the four subscales, resulting in a four-item measure: “I can’t handle feeling distressed or upset,” “My feelings of distress or being upset scare me,” “When I feel distressed or upset, I cannot help but concentrate on how bad the distress actually feels,” and “I will do anything to stop feeling distressed or upset.” Participants rated each item on a 10-point scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 10 (Strongly Agree). Responses are summed and range from 4 to 40, with higher scores indicating greater distress intolerance. The measure demonstrated strong internal consistency in the current sample (Cronbach α = .85). To facilitate the detection of statistical trends with respect to the dichotomous problematic alcohol use variable, we also categorized distress intolerance scores into quartiles as follows: 4 (Very Low); 5–11 (Low); 12–20 (Medium); 21–40 (High).

2.2.4 Covariates

Respondents were asked about their age (categorized as 18–25, 26–35 36–50, 51 and older), self-identified sexual orientation (coded as heterosexual/straight, bisexual, homosexual/gay, and unsure/questioning/other), and socioeconomic status (SES; no income, low income/lower class, middle income/middle class, and high income/upper class). Current country of residence was also assessed.

2.3 Data analysis

The mean, standard deviation (SD), and frequency of each variable are summarized in Table 1. We conducted a series of linear and logistic regression models to examine associations among CSA history, distress intolerance, and problematic alcohol use while controlling for demographic covariates (i.e., age, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation; see Table 2). In addition to examining the association between the continuous distress intolerance variable and problematic alcohol use, we also examined whether the odds of problematic alcohol use increased with each quartile of distress intolerance (ref = very low distress intolerance; see Table 3). Lastly, we tested the hypothesis that CSA history would be indirectly associated with problematic alcohol use through distress intolerance, such that, when distress intolerance is accounted for, the magnitude of the relationship between CSA history and problematic alcohol use would be reduced. Specifically, using a series of linear and logistic regression models, we assessed whether CSA history was directly associated with distress intolerance (path A) and problematic alcohol use (path C) and whether distress intolerance was directly associated with problematic alcohol use (path B). We then assessed the relationship between CSA history and problematic alcohol use while including distress intolerance as an additional variable in the model (path C’). Following the recommendations of Hayes (2013), bootstrapping was used to test whether path C’ is significantly weaker than path C, with statistical significance indicating evidence for full (relationship between CSA history and problematic alcohol use no longer significant) or partial mediation (relationship between CSA history and problematic alcohol use still significant, but magnitude of the association is reduced). For all analyses, regression coefficients were fit using generalized estimating equations (GEE) to account for clustering by country.

Table 1.

Demographic and psychosocial characteristics of Latin American MSM (n = 19,451).

| Total n =19,451 |

||

|---|---|---|

| CAGE score | Mean | SD |

|

|

||

| Range 0–4 | 0.5 | 0.9 |

| Distress intolerance | ||

| Range 4–40 | 14.0 | 10.0 |

|

|

||

| Age | n | % |

|

|

||

| 18–25 | 7213 | 37.1 |

| 26–35 | 7177 | 36.9 |

| 36–50 | 4365 | 22.4 |

| >50 | 696 | 3.6 |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Homosexual/gay | 15270 | 78.5 |

| Bisexual | 3626 | 18.6 |

| Unsure/questioning/other | 555 | 2.9 |

| SES | ||

| No income | 1501 | 7.7 |

| Low income/lower class | 1574 | 8.1 |

| Middle income/middle class | 14149 | 72.7 |

| High income/upper class | 1637 | 8.4 |

| Prefer not to answer | 590 | 3.0 |

| Country | ||

| Argentina | 1867 | 9.6 |

| Bolivia | 104 | 0.5 |

| Brazil | 2915 | 15.0 |

| Chile | 1214 | 6.2 |

| Colombia | 2593 | 13.3 |

| Costa Rica | 326 | 1.7 |

| Ecuador | 312 | 1.6 |

| El Salvador | 98 | 0.5 |

| Guatemala | 163 | 0.8 |

| Honduras | 41 | 0.2 |

| Mexico | 6679 | 34.3 |

| Nicaragua | 53 | 0.3 |

| Panama | 242 | 1.2 |

| Paraguay | 113 | 0.6 |

| Peru | 555 | 2.9 |

| Uruguay | 173 | 0.9 |

| Venezuela | 2003 | 10.3 |

| Childhood sexual abuse | ||

| Yes | 11020 | 56.7 |

| No | 8431 | 43.3 |

| Distress intolerance | ||

| Very low | 5227 | 26.9 |

| Low | 4663 | 24.0 |

| Medium | 4927 | 25.3 |

| High | 4634 | 23.8 |

| Problematic alcohol use (CAGE >=2) | ||

| Yes | 3060 | 15.7 |

| No | 16391 | 84.3 |

Table 2.

Distress intolerance as a mediator of childhood sexual abuse and problematic alcohol use among Latin American MSM (n = 19,451).

| Distress intolerance Path A

|

Problematic alcohol use Path B

|

Problematic alcohol use Path C

|

Problematic alcohol use Path C′

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aBeta | 95% CI | P-value | aOR | 95% CI | P-value | aOR | 95% CI | P-value | aOR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Childhood sexual abuse | 0.20 | 0.18–0.21 | <0.0001 | — | — | 1.37 | 1.27 – 1.47 | <0.0001 | 1.30 | 1.21–1.41 | <0.0001 | |

| Distress intolerance | — | — | — | 1.33 | 1.29–1.36 | <0.0001 | — | — | — | 1.31 | 1.28–1.35 | <0.0001 |

+ Path A had a continuous outcome, linear regression analyses were used, adjusted beta coefficient; Paths B, C, and C’ have binary outcomes - logistic regression used, adjusted odds ratios are presented.

aOR= Odds ratio adjusted for age, sexual orientation, and SES. All models adjusted for clustering by country using GEE.

Bootstrapping: The indirect effect estimate is 0.05 (95% CI is 0.05, 0.07).

Table 3.

Association of levels of distress intolerance and childhood sexual abuse by problematic alcohol use among Latin American MSM (n = 19,451).

| Problematic alcohol use | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P-value | aOR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Childhood sexual abuse | ||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Yes | 1.37 | 1.27–1.47 | <0.0001 | 1.30 | 1.21–1.41 | 0.001 |

| Distress intolerance | ||||||

| Very low | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Low | 1.46 | 1.28–1.66 | <0.0001 | 1.41 | 1.25–1.59 | <0.0001 |

| Medium | 1.78 | 1.61–1.97 | <0.0001 | 1.71 | 1.55–1.89 | <0.0001 |

| High | 2.47 | 2.28–2.68 | <0.0001 | 2.33 | 2.13–2.55 | <0.0001 |

+ aOR= Odds ratio adjusted for age, sexual orientation, and SES. All models adjusted for clustering by country using GEE. Distress intolerance scores were categorized by quartile: 4=Very Low; 5–11=Low; 12–20=Medium; 21–40 = High.

3 Results

Table 1 presents characteristics of the study sample. The majority of participants (74.0%) were between the ages of 18 and 35. More than three quarters identified as homosexual/gay (78.5%) and 18.6% identified as bisexual. The majority of participants (72.7%) were middle income/middle class relative to their country’s economy. Participants came from 17 countries in Latin America, with the greatest proportion of participants residing in Mexico (34.3%), followed by Brazil (15.0%). More than half of the participants (56.3%) reported experiencing childhood sexual abuse. The mean distress intolerance score was 14.0 (SD = 10.0). The mean CAGE score was 0.5 (SD = 0.9), and 15.7% of the sample had a CAGE score of 2 or higher (indicative of problematic alcohol use).

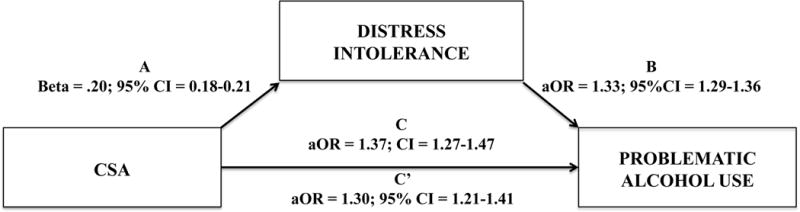

Table 2 presents a series of linear and logistic regression analyses testing the hypothesized associations among CSA history, distress intolerance, and problematic alcohol use. As expected, CSA was positively associated with distress intolerance, aBeta = .20, 95% CI = [0.18, 0.21], p < 0.001. Additionally, distress intolerance was associated with increased odds of reporting problematic alcohol use, aOR = 1.33, 95% CI = [1.29, 1.36], p < 0.001. As shown in Table 3, a statistical trend was detected for distress intolerance and problematic alcohol use: Compared to participants who scored in the “very low” category with respect to the distress intolerance measure, those who scored in the “low”, “medium”, and “high” categories were at increasing odds of engaging in problematic alcohol use. Participants who had experienced childhood sexual abuse were at increased odds of reporting problematic alcohol use compared to those without histories of childhood sexual abuse, aOR = 1.37, 95% CI = [1.27, 1.47], p < 0.001. However, this association was significantly reduced when distress intolerance was entered into the model, aOR = 1.30, 95% CI = [1.21, 1.41], p < 0.001. Bootstrapping indicates that distress intolerance partially mediated the association between CSA history and problematic alcohol use, 95% CI = [.05, .07]. The mediation model with all path coefficients is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mediation Model of Distress Intolerance: Childhood sexual abuse is associated with distress intolerance, which in turn is associated with problematic alcohol use. Model adjusted for age, sexual orientation, SES, and country.

4 Discussion

Utilizing a large, multinational sample of gay, bisexual, and other MSM in Latin America, the present investigation examined the role of distress intolerance as a psychological mechanism underlying the association between CSA history and problematic alcohol use. Consistent with our hypotheses, we found that individuals with CSA histories reported higher levels of distress intolerance, which was in turn associated with greater odds of reporting problematic alcohol use. In particular, as the level of distress intolerance increased, the odds of engaging in problematic alcohol use also increased, suggesting a dose-response relationship. Mediation analyses further supported our proposition that distress intolerance partially accounted for the association between CSA history and problematic alcohol use, highlighting its role as an important process linking early life trauma to alcohol-related problems in adulthood.

In the past decade, increasing empirical attention has been devoted to understanding the psychosocial mechanisms underlying the significant health disparities experienced by MSM relative to their heterosexual counterparts (Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Pachankis, 2015). In particular, early trauma and adversity associated with one’s sexual orientation has been posited to interfere with effective emotion regulation, thereby prompting emotional avoidance and maladaptive coping behaviors, such as self medicating with drugs or alcohol and engaging in risky sex (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008; Pachankis et al., 2015). Despite the prevalence of childhood sexual abuse among MSM and its well-documented associations with adverse health outcomes in adulthood (e.g., Boroughs et al., 2015; Mimiaga et al., 2009), little research has examined potential pathways through which CSA history might operate to influence mental and sexual health. The current study represented the first empirical attempt, to our knowledge, to examine the associations among CSA history, distress intolerance, and problematic alcohol use among MSM. Our findings provide initial evidence for the role of distress intolerance, both as a factor associated with problematic alcohol use and as a potential psychological mechanism underlying the association between CSA history and problematic alcohol use.

The current findings have important theoretical and clinical implications. Given that substance use problems often co-occur with other health threats as syndemics (e.g., depression, PTSD, risky sexual behaviors) among MSM who were sexually abused as children (Boroughs et al., 2015; Mimiaga et al., 2015a; Stall et al., 2003), identifying mechanisms underlying any of these health threats (e.g., substance use) can potentially inform research on other threats (e.g., risky sexual behaviors) (Pachankis, 2015). For example, the current findings regarding distress intolerance might be of particular relevance to future efforts to understand and address PTSD symptoms, which are characterized by avoidance of highly distressing thoughts, feelings, and memories concerning the trauma. Furthermore, because higher levels of distress intolerance can drive various maladaptive coping strategies (Leyro et al., 2010; Simons and Gaher, 2005), distress intolerance might serve as a promising treatment target for interventions designed to improve the mental and behavioral health of MSM who were sexually abused as children. Consistent with this possibility, clinical interventions that focus on non-judgmental awareness and acceptance of emotional distress (e.g., dialectical behavioral therapy, mindfulness-based stress reduction) have demonstrated efficacy in addressing trauma-related symptoms among women with CSA experiences (Kimbrough et al., 2010; Steil et al., 2011) as well as in treating substance use problems (Dimeff et al., 2000). Further, intervention research with MSM who have experienced CSA and are at risk for HIV (Project THRIVE) suggests that cognitive behavioral therapy, together with sexual risk reduction counseling, can help mitigate the mental health sequelae of CSA; the efficacy of this intervention is currently being tested in an randomized controlled trial (National Institute of Mental Health, 2011). Future research should explore the utility of dialectical behavioral therapy, mindfulness-based stress reduction, and other similar treatment approaches in addressing substance use and co-occurring mental health problems among MSM childhood sexual abuse survivors.

The present investigation has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of our data precluded predictive, causal conclusions. In particular, although distress intolerance has been prospectively linked to problematic alcohol use in previous research (Simons and Gaher, 2005), it is possible that, by providing temporary relief from emotional distress, problematic alcohol use might reinforce emotional avoidance in the long term and contribute to heightened distress intolerance over time. Future research could further clarify the relations among CSA history, distress intolerance, and problematic alcohol use by utilizing longitudinal and experimental methodologies. For example, prospective designs that include measures of distress intolerance and problematic alcohol use at repeated assessment points over time could help elucidate the mediating role of distress intolerance underlying the association between CSA history and problematic alcohol use. Furthermore, determining whether an intervention designed to reduce distress intolerance can alleviate the association between CSA history and problematic alcohol use represents another important direction for future research.

Second, given the need to minimize participant burden in a large, web-based survey and the lack of brief distress intolerance measures in the existing literature, a four-item measure was constructed by abbreviating the 15-item Distress Tolerance Scale (Simons and Gaher, 2005) for use in the current study. Although our item selection process was systematic (i.e., representing each of the four subscales with one item that had the highest factor loading) and the resulted scale demonstrated good internal consistency in the current sample (i.e., α = 0.85), it is not clear how the abbreviated scale might compare to the original scale in terms of its psychometric properties. Thus, the current findings regarding distress intolerance should be interpreted with caution and confirmed in future studies using the full-length Distress Tolerance Scale, especially in light of the relatively small effect sizes. Future research could also productively examine the abbreviated measure’s convergent, discriminant, and predictive validity across diverse samples, with the goal of developing an alternative, easy-to-administer measure of distress intolerance. Third, we note that the CSA history variable used in the current analyses was dichotomized based on whether participants reported experiencing one or more acts of sexual abuse before age 17. Although this dichotomization is common in the existing literature on CSA and MSM health (e.g., Boroughs et al., 2015; Mimiaga et al., 2009) and lends parsimony to data interpretation, it does not capture variations in abuse frequency or severity. Statistically, it might have also contributed to the small, though significant, effect sizes observed in our model (MacCallum et al., 2002). Future research could explore the association of CSA history with distress intolerance and problematic alcohol use among MSM using more nuanced measures that capture the frequency and severity of childhood sexual abuse experiences.

Lastly, given that the current sample only included MSM from Latin America, it is unclear whether the associations observed among CSA history, distress intolerance, and problematic alcohol use would generalize to MSM from other regions of the world. Future research could examine the generalizability of the current findings across cultural contexts by testing our mediation model using diverse, international samples of MSM from non-Latin-American countries. Additional work is also needed to assess whether other forms of trauma commonly faced by MSM, such as intimate partner violence and peer victimization, might relate to problematic alcohol use through heightened levels of distress intolerance.

In sum, the present study supports existing research on the high prevalence of alcohol-related problems among MSM in Latin America (Balán et al., 2013) as well as the positive association between childhood sexual abuse and alcohol use problems among this population (Carballo-Diéguez et al., 2012; Mimiaga et al., 2015a). The present research also extends existing work by providing initial evidence for the role of distress intolerance as a potential psychological mechanism underlying the association between CSA history and problematic alcohol use. Taken together, these findings underscore the potential utility of targeting distress intolerance in substance use prevention and intervention efforts geared towards MSM survivors of childhood sexual abuse.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported with funding from the Miller Foundation. Katie Wang is supported by grant 3R01MH109413-01S1 from National Institute of Mental Health. Jaclyn White Hughto is supported by grant 1F31MD011203-01 from National Institute on Minority Health Disparities. Funding sources had no role in study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

- Balán IC, Carballo-Diéguez A, Dolezal C, Marone R, Pando MA, Barreda V, Ávila MM. High prevalence of substance use among men who have sex with men in Buenos Aires, Argentina: Implications for HIV risk behavior. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:1296–1304. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0377-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boroughs MS, Valentine SE, Ironson GH, Shipherd JC, Safren SA, Taylor SW, Dale SK, Baker JS, Wilner JG, O’Cleirigh C. Complexity of childhood sexual abuse: Predictors of current post-traumatic stress disorder, mood disorders, substance use, and sexual risk behavior among adult men who have sex with men. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44:1891–1902. doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0546-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Keough ME, Schmidt NB. Problematic alcohol and cannabis use among young adults: The roles of depression and discomfort and distress tolerance. Addict Behav. 2007;32:1957–1963. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carballo-Diéguez A, Balan I, Dolezal C, Mello MB. Recalled sexual experiences in childhood with older partners: A study of Brazilian men who have sex with men and male-to-female transgender persons. Arch Sex Behav. 2012;41:363–376. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9748-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff L, Rizvi SL, Brown M, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy for substance abuse: A pilot application to methamphetamine-dependent women with borderline personality disorder. Cogn Behav Pract. 2000;7:457–468. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism: The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252:1905–1907. doi: 10.1001/jama.252.14.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiellin DA, Reid MC, O’Connor PG. Screening for alcohol problems in primary care: A systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1977–1989. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.13.1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geibel S, Tun W, Tapsoba P, Kellerman S. HIV vulnerability of men who have sex with men in developing countries: Horizons studies, 2001–2008. Public Health Rep. 2010:316–324. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein AL, Flett GL, Wekerle C. Child maltreatment, alcohol use and drinking consequences among male and female college students: An examination of drinking motives as mediators. Addict Behav. 2010;35:636–639. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Bornovalova MA, Delany-Brumsey A, Nick B, Lejuez C. A laboratory-based study of the relationship between childhood abuse and experiential avoidance among inner-city substance users: The role of emotional nonacceptance. Behav Ther. 2007;38:256–268. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Wolitski RJ, Millett GA. A holistic approach to addressing HIV infection disparities in gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. Am Psychol. 2013;68:261–273. doi: 10.1037/a0032746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannan S, Orcutt H, Miron L, Thompson K. Childhood sexual abuse and later alcohol-related problems: Investigating the roles of revictimization, PTSD, and drinking motivations among college women. J Interpers. 2015 doi: 10.1177/0886260515591276. Violence Ahead of Print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychol Bull. 2009;135:707–730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Emotion regulation and internalizing symptoms in a longitudinal study of sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49:1270–1278. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01924.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrough E, Magyari T, Langenberg P, Chesney M, Berman B. Mindfulness intervention for child abuse survivors. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66:17–33. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyro TM, Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A. Distress tolerance and psychopathological symptoms and disorders: A review of the empirical literature among adults. Psychol Bull. 2010;136:576–600. doi: 10.1037/a0019712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd S, Operario D. HIV risk among men who have sex with men who have experienced childhood sexual abuse: Systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Educ Prev. 2012;24:228–241. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2012.24.3.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Zhang S, Preacher KJ, Rucker DD. On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:19–40. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall BD, Shoveller JA, Kahler CW, Koblin BA, Mayer KH, Mimiaga MJ, den Berg JJ, Zaller ND, Operario D. Heavy drinking trajectories among men who have sex with men: A longitudinal, group‐based analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39:380–389. doi: 10.1111/acer.12631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx BP, Sloan DM. The role of emotion in the psychological functioning of adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Behav Ther. 2002;33:563–577. [Google Scholar]

- Mimiaga MJ, Biello KB, Robertson AM, Oldenburg CE, Rosenberger JG, O’Cleirigh C, Novak DS, Mayer KH, Safren SA. High prevalence of multiple syndemic conditions associated with sexual risk behavior and HIV infection among a large sample of Spanish-and Portuguese-speaking men who have sex with men in Latin America. Arch Sex Behav. 2015a;44:1869–1878. doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0488-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimiaga MJ, Noonan E, Donnell D, Safren SA, Koenen KC, Gortmaker S, O’Cleirigh C, Chesney MA, Coates TJ, Koblin BA. Childhood sexual abuse is highly associated with HIV risk–taking behavior and infection among MSM in the EXPLORE study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51:340–348. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a24b38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimiaga MJ, OʼCleirigh C, Biello KB, Robertson AM, Safren SA, Coates TJ, Koblin BA, Chesney MA, Donnell DJ, Stall RD. The effect of psychosocial syndemic production on 4-year HIV incidence and risk behavior in a large cohort of sexually active men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015b;68:329–336. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health. ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet] Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); 2011. HIV prevention and trauma treatment for men who have sex with men with childhood sexual abuse histories (THRIVE) [cited 2016 Oct26]. NLM Identifier: NCT01395979. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01395979?term=childhood+sexual+abuse+%26+MSM &rank=1. [Google Scholar]

- O’Cleirigh C, Ironson G, Smits JA. Does distress tolerance moderate the impact of major life events on psychosocial variables and behaviors important in the management of HIV. Behav Ther. 2007;38:314–323. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE. A transdiagnostic minority stress treatment approach for gay and bisexual men’s syndemic health conditions. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44:1843–1860. doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0480-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Rendina HJ, Restar A, Ventuneac A, Grov C, Parsons JT. A minority stress—emotion regulation model of sexual compulsivity among highly sexually active gay and bisexual men. Health Psychol. 2015;34:829–840. doi: 10.1037/hea0000180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul JP, Catania J, Pollack L, Stall R. Understanding childhood sexual abuse as a predictor of sexual risk-taking among men who have sex with men: The Urban Men’s Health Study. Child Abuse Negl. 2001;25:557–584. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00226-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polusny MA, Follette VM. Long-term correlates of child sexual abuse: Theory and review of the empirical literature. Appl Prev Psychology. 1995;4:143–166. [Google Scholar]

- Sartor CE, Agrawal A, McCutcheon VV, Duncan AE, Lynskey MT. Disentangling the complex association between childhood sexual abuse and alcohol-related problems: A review of methodological issues and approaches. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69:718–727. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer KR, Gupta S, Dillingham R. HIV-infected men who have sex with men and histories of childhood sexual abuse: Implications for health and prevention. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2013;24:288–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM. The Distress Tolerance Scale: Development and validation of a self-report measure. Motiv Emotion. 2005;29:83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Stall R, Mills TC, Williamson J, Hart T, Greenwood G, Paul J, Pollack L, Binson D, Osmond D, Catania JA. Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:939–942. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steil R, Dyer A, Priebe K, Kleindienst N, Bohus M. Dialectical behavior therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder related to childhood sexual abuse: A pilot study of an intensive residential treatment program. J Trauma Stress. 2011;24:102–106. doi: 10.1002/jts.20617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagenas P, Lama JR, Ludford KT, Gonzales P, Sanchez J, Altice FL. A systematic review of alcohol use and sexual risk-taking in Latin America. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2013;34:267–274. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]