Abstract

Objective To compare the efficacy and safety of rectal artemether with intravenous quinine in the treatment of cerebral malaria in children.

Design Randomised, single blind, clinical trial.

Setting Acute care unit at Mulago Hospital, Uganda's national referral and teaching hospital in Kampala.

Participants 103 children aged 6 months to 5 years with cerebral malaria.

Intervention Patients were randomised to either intravenous quinine or rectal artemether for seven days.

Main outcome measures Time to clearance of parasites and fever; time to regaining consciousness, starting oral intake, and sitting unaided; and adverse effects.

Results The difference in parasitological and clinical outcomes between rectal artemether and intravenous quinine did not reach significance (parasite clearance time 54.2 (SD 33.6) hours v 55.0 (SD 24.3) hours, P = 0.90; fever clearance time 33.2 (SD 21.9) hours v 24.1(SD 18.9 hours, P = 0.08; time to regaining consciousness 30.1 (SD 24.1) hours v 22.67 (SD 18.5) hours, P = 0.10; time to starting oral intake 37.9 (SD 27.0) hours v 30.3 (SD 21.1) hours, P = 0.14). Mortality was higher in the quinine group than in the artemether group (10/52 v 6/51; relative risk 1.29, 95% confidence interval 0.84 to 2.01). No serious immediate adverse effects occurred.

Conclusion Rectal artemether is effective and well tolerated and could be used as treatment for cerebral malaria.

Introduction

Cerebral malaria is the most severe and life threatening complication of Plasmodium falciparum malaria and carries a case fatality rate1 of 5-40%, with most deaths occurring within the first 24 hours.2 Although the recommended treatment of cerebral malaria is intravenous quinine,1 alternative drugs are necessary where intravenous treatment is not possible.3 Most studies comparing rectal artemether with intravenous quinine were carried out in adults.4-6 The results were variable, and information on the use of artemether in children is limited.6 One recent study found that a single dose of rectal artesunate is associated with rapid reduction in parasite density in children and adults with moderately severe malaria.7

If found effective, rectal artemether might be particularly useful for treating severely ill children at peripheral health units,2 where facilities for intravenous treatment are often lacking.3,8 Using rectal formulations might prevent potentially life threatening complications arising from delays in administering effective antimalarial treatment to children with cerebral malaria. We compared the efficacy and safety of rectal artemether with that of intravenous quinine in the treatment of children, aged 6 months to 5 years, with cerebral malaria.

Methods

This study was carried out in Mulago Hospital, Uganda's national referral and teaching hospital, from July 2002 to February 2003. We recruited patients from the acute care unit (the paediatric emergency unit of the hospital) and followed them up for seven days.

Randomisation and blinding

Instructions for treatment were produced according to a randomisation scheme in blocks of eight, generated by a statistician not involved in study design, data processing, or analysis, who used SAS, version 8.1 (SAS Institute Inc, 100 SAS Campus Drive, Cary, NC 27513-2414,USA). An independent doctor prepared the instructions for each patient in advance, in sealed envelopes with unique identification numbers according to the randomisation code. Sealed codes were kept safely in the paediatrics department and were opened only once data analysis was complete.

The rectal artemether “suppogels” were similar in appearance and packaging to the rectal placebo. In effect this was a single blind study, since the children received placebo but the treatment nurses were aware of the treatment allocations.

Both groups had intravenous lines and received 5% dextrose given as 10 ml/kg every eight hours, run in for two to four hours until they regained consciousness. When patients receiving rectal artemether regained consciousness they were, in addition to their artemether treatment, given oral placebo tablets containing lactose and starch, since the children receiving intravenous quinine were given oral quinine as soon as they regained consciousness.

Patients

We recruited children aged 6 months to 5 years who were admitted to the acute care unit during the study period with cerebral malaria (seizures and unarousable coma lasting more than 30 minutes after seizures have stopped, with asexual forms of P falciparum on the blood film, with no other cause of coma) and whose carers gave informed consent. We excluded children who had received derivatives of artemesinin or quinine or had had more than four bowel motions in the 24 hours before admission.

Enrolment

In the acute care unit, a nurse arranged for a blood test for malaria and identified possible cases of cerebral malaria. One of the investigators (JRA) further assessed patients with P falciparum on the thick blood film. All patients had a lumbar puncture to obtain cerebrospinal fluid, to exclude other causes of coma. We assumed that children with normal cerebrospinal fluid had only cerebral malaria. Carers in whose children cerebral malaria had been confirmed received further explanation about the study and provided written informed consent. They picked one envelope each from the block and handed it over to the nurse, who administered drugs to the children according to the protocol in the envelope.

Drugs and placebos

Rectal artemether suppogels (Dafra Pharma, Belgium, batch No 02E01) were oblong capsules containing soya oil in which 40 mg of artemether was dissolved. The rectal placebos contained only soya oil. Intravenous quinine hydrochloride was manufactured in France by Laboratoire Renaudin (batch No 12589). The oral placebos containing only lactose and starch came from Rene Pharmaceuticals in Uganda.

Drug administration

Treatment was started as soon as the patient was enrolled and lasted seven days to avoid relapse. Patients in the quinine arm received a loading dose of 20 mg/kg of intravenous quinine in 20 ml/kg of 5% dextrose in water for two to four hours. This was reduced to 10 mg/kg in 10 ml/kg of 5% dextrose in water every eight hours until a patient regained consciousness. Quinine was then given orally (10 mg/kg, every eight hours) until seven days of treatment had been completed.

Patients receiving rectal artemether were treated according to the manufacturer's guidelines. Children weighing up to 8.9 kg received 40 mg immediately (one suppository) and continued to be given 40 mg daily for seven days. Children weighing 9-18.9 kg received 80 mg immediately and continued to be given 40 mg daily for seven days, and those weighing 19-27.9 kg received 120 mg immediately and continued to be given 80 mg daily.

Sample size calculation

We calculated a sample size of 50 patients in each group for 90% power and 95% confidence. In the calculation, we assumed that the children receiving intravenous quinine would have a mean parasite clearance time of 51.2 (SD 23.2) hours and those receiving rectal artemether would have a mean parasite clearance time of 37.9 (SD 17.4) hours (26% effect size), according to a study by Hien and Arnold in Vietnam.5

Laboratory tests

We used Giemsa stained thick films to determine the density of asexual malaria parasites, which we counted per 200 white blood cells and expressed as parasites per μl—assuming a total white blood cell count9 of 8000 × 106/l. We recorded parasite density at 0 hours, and microscopists who were blinded to the patients' clinical situation or treatment examined subsequent smears in two independent laboratories every 12 hours. We recorded a smear as negative when we found no asexual forms.

Main outcome measures

We used six main outcome measures. Parasite clearance time was the time from starting antimalarial treatment to the first negative blood slide. Fever clearance time was from the start of antimalarial treatment until the patient had a body temperature below 37.5°C for 24 hours. We used the Blantyre coma scale daily to assess time to regain consciousness10 and took this as the time from onset of treatment to the time when the patient regained consciousness. We recorded time to starting oral intake of feeds and time to sitting up unaided as time from onset of treatment to beginning of these activities. We recorded complications and side effects of the drugs.

Data management and analysis

We entered our data into Epi-Info, version 6 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA 30333, USA) and used SPSS, version 11.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL 60606, USA) to analyse them. Student's t test and the log rank test were our testing tools for significance of the differences in means between the two treatment groups for continuous outcomes, and χ2 and Fisher's exact tests for categorical outcomes. We considered P < 0.05 significant.

Results

From July 2002 to February 2003, we enrolled 103 patients with cerebral malaria and randomly assigned them to treatment with either intravenous quinine or rectal artemether (fig 1). The patients in the two groups were comparable in sociodemographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics.

Fig 1.

Flow of participants through the trial

The distribution of the patients' clinical symptoms and signs were comparable on admission between the two treatment groups (tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Baseline symptoms and signs of patients in both treatment arms on admission. Values are numbers (percentages) of patients

| Variable | Artemether (n=51) | Quinine (n=52) |

|---|---|---|

| Cough | 29 (57) | 32 (62) |

| Vomiting | 19 (37) | 28 (54) |

| Difficulty breathing | 12 (24) | 11 (21) |

| Abnormal posture | 6 (12) | 4 (8) |

| Blantyre coma score* | ||

| 2 | 38 (75) | 39 (75) |

| 1 | 12 (23) | 12 (23) |

| 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Blood transfusion | 30 (59) | 31 (60) |

Minimum score 0 (poor); maximum score 5 (good); abnormal score ≤4.

Table 2.

Baseline clinical and laboratory characteristics before treatment for patients with cerebral malaria for both treatment arms. Values are means with standard deviations unless otherwise indicated

| Variable | Artemether (n=51) | Quinine (n=52) |

|---|---|---|

| Age in months | 28.0 (14.6) | 26 (16.4) |

| Weight in kg | 11.0 (2.8) | 10.8 (2.4) |

| Temperature in degrees Celsius | 38.3 (1.3) | 38.9 (8.9) |

| Coma duration in hours | 11.8 (9.6) | 11.3 (10.3) |

| Systolic blood pressure in mm Hg | 89.2 (12.7) | 91.0 (11.9) |

| Diastolic blood pressure in mm Hg | 62.0 (11.4) | 61.0(13.7) |

| Haemoglobin in mmol/l | 1.0 (0.3) | 0.9 (0.4) |

| Alanine amino transferase (ALT) in IU/l | 31.8 (44.2) | 85.0 (40.0) |

| Aspartate amino transferase (AST) IU/l | 70.7 (67.4) | 166.0 (70.8) |

| Total bilirubin in μmol/l | 22.7 (17.1) | 29 (37.6) |

| Creatinine in μmol/l | 8.84 (5.5) | 7.96 (2.7) |

| Potassium in mmol/l | 4.6 (0.77) | 4.2 (0.85) |

| White blood cells ×106/l | 9614 (6469) | 9347 (5029) |

| Median parasite density per μl (interquartile range) | 84 474 (16 622-208 010) | 75 526 (13 145-324 600) |

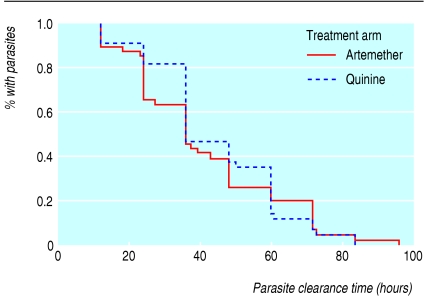

The main outcome measures were comparable between the two groups (table 3). Kaplan-Meier curves (fig 2) and the log rank test for parasite clearance time showed no significant difference between the two groups. The times to regaining consciousness and fever clearance did not differ significantly between the two groups ((P = 0.01 and P = 0.08, respectively).

Table 3.

Clinical and parasitological outcomes of treatment for patients with cerebral malaria in the two treatment arms. Values are means with standard deviations

| Outcome in hours | Artemether (n=45) | Quinine (n=42) | P value*(Student's t test) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parasite clearance time | 54.2 (33.6) | 55.0 (24.3) | 0.48 |

| Fever clearance time | 33.2 (21.9) | 24.1 (18.9) | 0.08 |

| Time to regaining consciousness | 30.1 (24.1) | 22.7 (18.5) | 0.10 |

| Time to starting oral intake | 37.9 (27.0) | 30.3 (21.1) | 0.14 |

| Time to sitting unsupported | 51.7 (30.8) | 43.5 (29.3) | 0.22 |

The difference of clinical and parasitological outcomes between intravenous quinine and rectal artemether did not reach significance.

Fig 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve for parasite clearance time for children receiving artemether or quinine. The difference in parasite clearance rates between the two treatment groups did not reach significance by the log rank test (P=0.666)

Adverse effects

We did not observe drug side effects such as skin rash, hypotension, jaundice, and diarrhoea in either treatment arm. Five children developed vomiting when they regained consciousness: three (7.1%) receiving quinine and two (4.4%) receiving artemether (P = 0.235, Fisher's exact test). This did not last for more than 24 hours. None of the children showed allergy to either drug, complained of tenesmus, or had rectal bleeding. Liver and renal function tests, altered on admission, had normalised by discharge (table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of admission with discharge biochemical characteristics of children treated for cerebral malaria for the two treatment groups. Values are means with standard deviations

|

Artemether (n=45)

|

Quinine (n=42)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Admission | Discharge | Admission | Discharge |

| Alanine transferase (ALT) in IU/l | 31.8 (44.2) | 21.0 (12.3) | 85.0 (40.0) | 28.0 (44.4) |

| Aspartate amino transferase (AST) in IU/l | 70.7 (67.4) | 35.6 (29.8) | 166.0 (70.8) | 46.0 (41.2) |

| Bilirubin in μmol/l | 22.2 (17.1) | 5.1 (3.76) | 29.0 (37.6) | 20.5 (82) |

| Creatinine in μmol/l | 8.84 (5.3) | 6.2 (1.68) | 7.96 (2.65) | 6.2 (2.12) |

| Potassium in mmol/l | 4.6 (0.77) | 4.5 (0.79) | 4.2 (0.85) | 4.7 (1.62) |

Mortality was higher in the quinine group than in the artemether group (10/52 v 6/51, relative risk 1.29, 95% confidence interval 0.84 to 2.01). Postmortem findings in eight of the children who died included intense petechial haemorrhages affecting the white matter and cerebellar surface; parasitised red blood cells and malaria pigment in the brain tissue; and parasitised red blood cells in the liver.

Discussion

Rectal artemether is effective and well tolerated and could be used to treat cerebral malaria. The clinical and parasitological outcomes of rectal artemether and intravenous quinine were similar.

Parasite clearance time

The mean parasite clearance time for rectal artemether was shorter than for intravenous quinine, although the difference did not reach significance. This agrees with similar studies comparing rectal artemether with intravenous quinine,4-6 although the parasite clearance time for artemether in our study was slightly higher. This could be due to thick blood films for asexual parasitaemia being taken every 12 hours, whereas other studies took them every four hours, every six hours, and then every 12 hours. The accuracy of parasite clearance has been shown to improve with frequent (four to six hourly) measurement of parasitaemia.11-13 The parasite clearance time after oral, intramuscular, or rectal artemether is shorter in patients with uncomplicated malaria than in those with complicated malaria.14

Fever clearance time

The fever clearance time for intravenous quinine was shorter than for rectal artemether, but the difference did not reach significance, which echoes findings from Kenya.6 The longer fever clearance time with artemether could be due to the time it took to reach therapeutic plasma concentrations after rectal artemether had been administered.15 Another possible reason might be artemether's less inhibitory activity against tumour necrosis factor α compared with quinine, as shown in one vitro study.16 Fever clearance time has been variable within studies; some reported a faster clearance with artemether than with quinine,4,5 whereas others found no difference.6,17-18

What is already known on this topic

Rectal artemether has a faster parasite clearance time than quinine

Patients with higher parasite density clear their parasites more slowly than patients with lower density parasite

Intravenous quinine is the treatment of choice for cerebral malaria

What this study adds

Rectal artemether could be used to treat cerebral malaria in settings where qualified staff and equipment for intravenous therapy is not readily available

Rectal artemether is easy to administer

Time to start oral intake and time to sit unsupported

The clinical outcomes of times to starting oral intake and sitting unsupported were similar in both groups. Most studies comparing rectal artemether with intravenous quinine were in adults, and these outcome measures were not documented.4,5 Hence there are no studies with which to compare the current results.

Adverse events

Both drugs had few side effects. Vomiting was more common in the quinine group, but the difference did not reach significance (P = 0.24). Persistent hypoglycaemia was seen in one child receiving quinine. This patient had poor liver function before starting treatment and died within 12 hours of admission despite intravenous 25% dextrose in water given every four hours. Strict, two hourly feeding could explain the low incidence of hypoglycaemia. Renal and liver function tests and haematological variables, which were altered on admission, improved in both groups. This agrees with other studies5,6,17,18 and reiterates the fact that neither drug has any adverse effects on these functions.

We did not observe unwanted side effects of artemether suppogels, such as tenesmus after bowel irritation. This finding is at odds with observations on adults receiving rectal artemether in Ethiopia,4 possibly because adults are more likely to report variations in their body function.

Mortality was higher in the quinine group than in the artemether group (10/52 v 6/51; relative risk 1.29, 95% confidence interval 0.84 to 2.01). The reason for the lower death rate with artemether is not clear. Several trials in south east Asian adults with severe malaria indicated that treatment with artemesinin derivatives might halve mortality.12,13

The overall fatality rate of 15.5% is comparable to that of other cerebral malaria studies: 17% in Kenya6 and 15% in Malawi.19

Editorial by Whitty et al and p 347

We thank the doctors, nurses, doctors, laboratory staff, and Paul Ekwaru for help with statistical issues.

Contributors: JRA, JSB, and JKT designed and coordinated the study. JRA supervised enrolment and follow up of patients. JRA and JKT analysed and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. JSB helped in interpreting the data and revising the manuscript. JKT is guarantor.

Funding: World Health Organization, Uganda country office; Uganda Malaria surveillance Project; Regional Center for Quality of Health Care; Ministry of Health, Uganda; and the Nuffield Foundation, United Kingdom, provided financial support. Dafra Pharma (Belgium) supplied the suppogels (rectal artemether and rectal placebos). Rene Pharmaceuticals (Uganda) provided the oral placebos.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Makerere Faculty of Medicine Ethics and Research Committee and Uganda National Council for Science and Technology.

References

- 1.Warrell D, ME M, Beales P. Severe and complicated malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1990;84: 1-65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D'Alessandro U. Treating severe and complicated malaria. BMJ 2004;328: 155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simoes E, Peterson S, Gamatie Y, Kisanga F, Mukasa G, Nsungwa-Sabiiti J, et al. Management of severely ill children at first-level health facilities in sub-Saharan Africa when referral is difficult. Bull World Health Organ 2003;81: 522-3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birku Y, Makonnen E, Bjorkman A. Comparison of rectal artemesinin with intravenous quinine in the treatment of severe malaria in Ethiopia. East Afr Med J 1999;76: 154-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hien T, Arnold K, Vinh H, Cuong B, Phu N, Chau T, et al. Comparison of artemesinin suppositories with intravenous artesunate and intravenous quinine in the treatment of cerebral malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1992;86: 582-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esamai F, Ayuo P, Owino-Ongor W, Rotich J, Ngindu A, Obala A, et al. Rectal dihyroartemesinin versus intravenous quinine in the treatment of severe malaria: a randomised clinical trial. East Afr Med J 2000;77: 273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes KI, Mwenechanya J, Tembo M, McIlleron P, Folb P, Ribeiro I, et al. Efficacy orf rectal artesunate compared with parenteral quinine in initial treatment of moderately severe malaria in African children and adults: a randomised study. Lancet 2004;363: 1598-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peterson S, Nsungwa-Sabiiti J, Were W, Nsabagasani X, Magumba G, Nambooze J, et al. Coping with paediatric referral—Ugandan parents' experience. Lancet 2004;363: 1955-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorsey G, Njama D, Kamya MR, Cattamanchi A, Kyabayinze D, Staedke S, et al. Sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine alone or with amodiaquine or artesunate for treatment of uncomplicated malaria. Lancet 2002;360: 2031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newton C, Chokwe T, Schellenberg J, Winstanley P, Forster D, Peshu N, et al. Coma scales for children with severe falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1997;91: 161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang J, Li G, Guo X, Kong Y, Arnold K. Antimalarial activity of mefloquine and qinghaosu. Lancet 1982;2: 285-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pe Than Myint TS. The efficacy of artemether (qinghaosu) in Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax in Burma. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 1986;17: 19-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shwe T, Myint P, Htut Y, Myint W, Soe L. The effect of mefloquine-artemether compared with quinine on patients with complicated falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1988;82: 665-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alin M, Kihamia C, Bjorkman A, Bwijo B, Premji Z, Mtey G, et al. Efficacy of oral and intravenous artesunate in male Tanzanian adults with Plasmodium falciparum malaria and in vitro susceptibility to artemesinin, chloroquine, and mefloquine. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1995;53: 693-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hien T, White N. Qinghaosu. Lancet 1993;341: 603-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwiatkowski D, Bate C. Inhibition of tumour necrosis factor (TNF) production by antimalarial drugs used in cerebral malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1995;89: 215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker O, Salako L, Omokhodion I, Sowunmi A. An open randomized comparative study of intramuscular artemether and intravenous quinine in cerebral malaria in children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1993;87: 564-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Hensbroek MB, Onyiorah E, Jaffar S, Schneider G, Palmer A, Frenkel J, et al. A trial of artemether or quinine in children with cerebral malaria. N Engl J Med 1996;335: 69-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor T, Wills B, Kazembe P, Chisale M, Wirima J, Ratsma E, et al. Rapid coma resolution with artemether in Malawian children with cerebral malaria. Lancet 1993;341: 661-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]