Abstract

The challenge of crystallizing single-pass plasma membrane receptors has remained an obstacle to understanding the structural mechanisms that connect extracellular ligand binding to cytosolic activation. For example, the complex interplay between receptor oligomerization and conformational dynamics has been, historically, only inferred from static structures of isolated receptor domains. A fundamental challenge in the field of membrane receptor biology, then, has been to integrate experimentally observable dynamics of full-length receptors (e.g. diffusion and conformational flexibility) into static structural models of the disparate domains. In certain receptor families, e.g. the ErbB receptors, structures have led somewhat linearly to a putative model of activation. In other families, e.g. the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptors, structures have produced divergent hypothetical mechanisms of activation and transduction. Here, we discuss in detail these and other related receptors, with the goal of illuminating the current challenges and opportunities in building comprehensive models of single-pass receptor activation. The deepening understanding of these receptors has recently been accelerated by new experimental and computational tools that offer orthogonal perspectives on both structure and dynamics. As such, this review aims to contextualize those technological developments as we highlight the elegant and complex conformational communication between receptor domains. This article is part of a Special Issue entitled: Interactions between membrane receptors in cellular membranes edited by Kalina Hristova.

Keywords: Membrane receptors, Epidermal growth factor receptor, ErbB receptors, Tumor necrosis factor receptors

1. Introduction

While there are many available structures of isolated extracellular or intracellular domains of single-pass membrane receptors, to date there are no atomistic-resolution structures of full-length, single-pass receptors. The isolated domain structures, often oligomeric, do not easily translate into a unified view of the structural mechanism of signal transduction [1–3]. Therefore, building a seamless model that captures the complex structural and dynamic coordination between the extracellular and intracellular domains, as transduced by the α-helical transmembrane (TM) domain remains a major challenge. Recently, NMR and computational modeling have provided an essential link to crystallography by making available structures of TM domain α-helical oligomers (typically dimers and/or trimers) [4–6]. These structural models of TM domains have significantly helped the process of connecting disjointed domain structures. This link has become especially important recently, as TM domains are increasingly known to play an active role in both receptor oligomerization and in the conformational changes that transduce a signal across the membrane [7].

The process of piecing together these three disparate domains (ecto-, TM, and cytosolic) has often been confounded by stoichiometric disparities between available structures, raising questions about the precise mechanism of signal initiation. For example, there are well-known instances within the structurally homologous tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) superfamily where ligands and receptor ectodomains are trimeric but cytosolic domains are dimeric or oligomeric [1–3,8–11]. In those cases, what is the relevant signaling unit? What role, if any, does the TM domain play in linking ectodomain trimers and cytosolic dimers? How do we reconcile the existence of both dimeric and oligomeric structures of intracellular domains bound to downstream signaling proteins? And, perhaps most importantly, how does receptor oligomerization relate to backbone conformational changes in the receptors? Recent advances in high-resolution imaging, including Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET), electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR), single molecule tracking, super-resolution imaging, and electron microscopy, are allowing us to answer these and other questions. Moreover, coupling these biophysical and imaging modalities with quantitative analysis and modeling, we can begin to clarify the connection between receptor oligomeric states and conformational changes across the membrane.

In this review, we first highlight early and recent structural studies of soluble receptor ectodomains and cytoplasmic domains, specifically focused on growth factor receptors (epidermal and fibroblast growth factor receptors, EGFR and FGFR, respectively) and the TNFR superfamily. The number of structures for each of these families is vast, however these structures have given rise to two very different outcomes, one—ErbB and other growth factor receptors—in which the stoichiometry of available structures generally points to a putative model for activation, and one—TNFRs—in which they do not. We then discuss recently published NMR structures of TM domains. These structures provide a physical basis for TM domain involvement in signaling. However, in isolation it remains far from trivial to conclude how the TM domains link extracellular and intracellular structures and relate to signaling. Thus, we then review recent developments in cell-based biophysical measurements that address these unknowns. Do TM domains simply serve to stabilize the overall oligomeric architecture of the receptors? Or do they themselves undergo conformational changes (e.g. opening or twisting) that perturb the connected cytosolic domains?

To fully elucidate the complex relationship between receptor structure, conformational dynamics, and dynamic structural assemblies will require ongoing and high-resolution studies of full-length membrane receptors. As such, we conclude with a brief overview of new technologies that hold promise to fill in the gaps, and to boost efforts to build unified and predictive molecular models of receptor activation.

2. Crystal structures of isolated soluble domains offer an alluring but incomplete view of the mechanism of activation of full-length membrane receptors

Signaling via membrane receptors is fundamentally linked to the structure of the receptor and the dynamic changes in structure and interactions upon binding to ligand. Typical mechanisms of ligand-induced signaling include ligand-mediated conformational changes, either through induced-fit or conformational selection [12], the nucleation of oligomeric receptor assemblies, and in many cases both. X-ray crystallography has long been the predominant method for structure determination of soluble protein domains, providing angstrom resolution structures of ectodomains and intracellular domains in a range of conformations representing different states of activation. However, it is critical that these crystal structures be viewed and interpreted for what they are: static assemblies of isolated receptor domains. We know, however, that receptor signaling involves dynamic changes in protein structure and interactions. How do we create models of dynamic signaling events of full-length membrane proteins from static and segmented structures? In some instances, multiple lines of evidence, including fragmented structures, lead to a putative mechanism of activation. This is the case for the ligand-induced dimer model of EGFR and other growth factor receptors, though this hypothesis has been repeatedly challenged. In other instances, such as TNFRs, the collection of structural and biochemical data points to a mechanism of activation that is less clear. Specific TNFR assemblies that lead to signaling are not precisely known, and conflicting structures yield multiple hypothetical models of activation. In this section we will review a handful of available crystal structures of EGFR (and other ErbB receptors) as well as TNFRs. We discuss how such structures of both extracellular and intracellular domains suggest a model of activation, or lead to multiple divergent hypotheses.

2.1. EGFR and other ErbB receptors: A model for ligand-induced dimerization and activation

In the case of EGFR signaling, crystal structures of extracellular ligand binding domains and intracellular kinase domains point to a common mechanism of signal initiation. Ligand binding causes a receptor conformational change from an autoinhibited structure to a dimer-competent structure. Ectodomain dimerization ultimately leads to dimerization and activation of intracellular kinase domains [13]. Early biochemical and biophysical studies using titration calorimetry and small angle X-ray scattering of the soluble EGFR ectodomain demonstrated that EGFR dimerization occurs via a two-step process. First, a single EGF ligand binds EGFR forming a stable intermediate 1:1 EGF-EGFR ligand-receptor structure. Second, dimerization of two monomeric EGF-EGFR complexes forms the 2:2 EGF-EGFR complex [14]. The first crystal structures of the EGFR ectodomain, in complex with TGFα and EGF, confirmed the stable 2:2 ligand-receptor complex via receptor-mediated dimerization in a “back-to-back” conformation (Fig. 1A, right) [15–17].

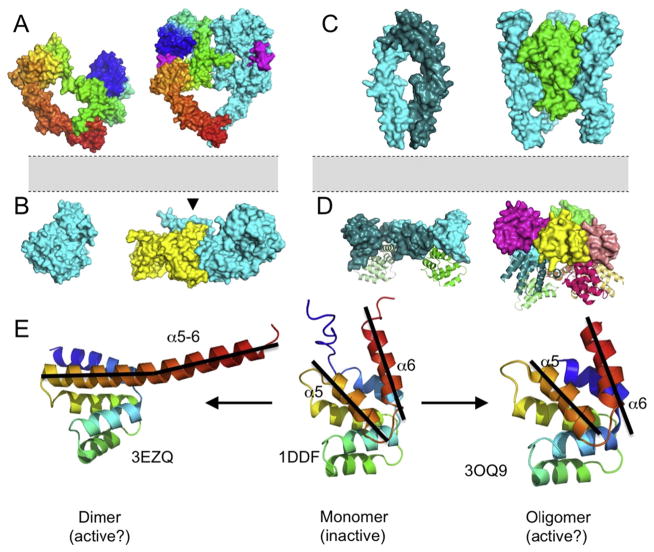

Fig. 1. Representative crystal structures of ErbB and TNFR receptor families.

(A–B) Crystal structures of EGFR give a view of receptor activation across the membrane, where ligand binding stabilizes a dimer competent structure leading to ectodomain dimerization followed by asymmetric dimerization and allosteric activation of the intracellular kinase domains. (A) Crystal structures of the EGFR extracellular domain in the tethered, autoinhibited conformation (left, PDB ID 1NQL) [18], and the ligand-bound, extended receptor dimer (PDB ID 3NJP) [17]. The receptor is colored from N-terminus (blue) to TM-proximal C-terminus (red), and the membrane is represented in gray. The second protomer of the EGFR dimer is shown in cyan, and the EGF ligand is shown in magenta. (B) The structure of the EGFR kinase domain monomer (left, PDB ID 1M14) [26] and active asymmetric dimer (right, PDB ID 3gop). The EGFR kinase domain is activated via an allosteric mechanism resulting from formation of an asymmetric kinase dimer, initially shown structurally by Zhang et al. [27], showing extensive interactions between the N-lobe of one kinase protomer with the C-lobe of a second kinase. The critical juxtamembrane (JM) residues, which further stabilize the active kinase dimer, are highlighted by the arrowhead. A similar structure including JM interactions was simultaneously solved by an independent group [44]. For review of the role of the JM region see ref. [39]. (C) Crystal structure of a TNFR1 ectodomain receptor dimer shows extensive contacts in the membrane distal cysteine rich domain (left, PDB ID 1NCF) [73], commonly referred to as the pre-ligand assembly domain for its role in mediating receptor self-association in the absence of ligand stimulation [74]. Crystal structure of the LTα-TNFR1 trimer (right, PDB ID 1TNR) [72]. The trimeric LTα ligand is shown in green and the three receptor protomers are shown in cyan. In this conformation, the tightly packed ligand trimer coordinates the assembly of three non-interacting receptor protomers separated by a distance of ~50 angstroms. Structurally homologous ligand-receptor trimer structures exist for TNFR2 [78], DR5 [9–11], DcR3 [79], and RANKL/Osteoprotegerin [80]. (D) Crystal structure of the dimeric (left, PDB ID 3EZQ) [3] and oligomeric (right, PDB ID 3OQ9) [1] Fas intracellular death domain in complex with the downstream Fas-associated death domain (FADD). The Fas-DD is shown as surface representation, and the downstream FADD is shown as a cartoon representation. (E) Structural overlay of the dimeric (left) and oligomeric (right) Fas-DD:FADD complexes with the monomeric Fas intracellular death domain (center, PDB ID 1DDF) [88]. The Fas-DD dimer undergoes a conformational change with an elongated C-terminal α-helix which provides a binding groove for downstream FADD. Conversely, the oligomeric Fas-DD is nearly identical to the monomeric Fas-DD, and the complex contains FADD. These results suggest that FADD may be recruited in a number of structural conformations.

A crystal structure of EGFR in the absence of ligand provided a first glimpse into the receptor conformational dynamics involved in ligand binding and dimerization. In the absence of ligand, the structure of EGFR solved by Ferguson et al. demonstrated that the unliganded receptor adopts a tethered, autoinhibited structure where the dimerization interface is buried and inaccessible (Fig. 1A, left) [18]. Structural alignment of the resting EGFR (Fig. 1A, left) and ligand-bound receptor (Fig. 1A, right) demonstrates that the N-terminal region of the receptor undergoes a 130° rotation and 20 angstrom translation to accommodate ligand binding. By extension, these structures suggest that EGFR exists in a thermodynamic equilibrium between the tethered, autoinhibited and extended, dimer-competent states. The tethered structure of EGFR is considered the predominant conformation in the absence of ligand, and EGF stabilizes the extended conformation, exposing the dimerization interface and leading to ligand-dependent, receptor mediated dimerization.

The four members of the ErbB family of growth factor receptors are highly homologous both at a sequence level and a structural level [19]. Interestingly, crystal structures of the various receptors point to differing receptor dynamics that play a key role in signaling. For example, a similar autoinhibited structure exists for ErbB3 [20] and ErbB4 [21], suggesting a common mechanism of structural autoinhibition among the ErbB receptors. In contrast, the unliganded structure of ErbB2 (HER2) resembles the extended and dimer-competent conformation of EGFR [22], suggesting that, in contrast to other ErbB receptors, ErbB2 lacks autoinhibitory interactions and exhibits an altered equilibrium of conformations highly biased toward the extended, activated state. Additionally, ErbB2 has no known ligand, and the crystallographic observation that the ligand-independent structure is dimer-competent is consistent with the suggested role of ErbB2 as a heterodimeric partner for other ErbB receptors [23]. The nuanced structural mechanism of heterodimerization may vary among the ErbB receptors [24], but they all exhibit activation by dimerization. The presumed thermodynamic equilibrium of the ErbB2 ectodomain is biased toward the extended conformation, therefore its role as a heterodimeric ErbB receptor partner exemplifies how changes in structure and dynamics alter receptor interactions to drive signal transduction.

It is critical to view EGFR (or other ErbB receptor) structural dynamics and interactions of the ectodomain in the context of what we know about the intracellular machinery. A number of crystal structures of the intracellular kinase domain support the model in which dimerization activates the receptor (Fig. 1B). The structure of the monomeric kinase domain illustrates a two-lobed architecture characteristic of protein kinases and kinase domains [25] (Fig. 1B, left) with a N-lobe comprised primarily of β-strands and a C-lobe comprised primarily of α-helices [26]. The molecular mechanism of kinase activation, which leads to autophosphorylation of key tyrosine residues in the receptor tail, was revealed through crystallography of the kinase dimer by Zhang et al. [27]. The structure, along with biochemical evidence, showed clearly that activation follows the formation of an asymmetric kinase dimer, where the C-lobe of one kinase (the activator kinase) interacts with the N-lobe of the adjacent kinase (the receiver kinase), causing displacement of an activation loop and the catalytically critical αC-helix within the N-lobe of the receiver kinase, which forms extensive interactions with the activator kinase. Therefore, the monomeric kinase domain is intrinsically autoinhibited, and asymmetric dimerization leads to activation via an allosteric mechanism [27]. Furthermore, crystal structures of the kinase dimer demonstrate how EGFR mutations, such as those associated with non-small cell lung carcinoma [28–30], lead to conformational changes in kinases that are similar to those associated with activation [27,31,32].

Similar to the ectodomain, which forms heterodimeric complexes, asymmetric kinase dimerization is also not exclusively homotypic in nature. A recent crystal structure of the EGFR:ErbB3 asymmetric kinase dimer shows a similar mechanism of allosteric activation [33]. Interestingly, ErbB receptors show relative preferences toward heterodimerization [34], specifically with ErbB2 [35], however it is unknown whether propensities for homodimerization or heterodimerization are primarily driven via interactions within the ectodomain, intracellular domain, or transmembrane domain. Furthermore, it remains unknown whether heterodimerization of kinase domains leads to a preferred activator/receiver orientation of the different kinases within an asymmetric heterodimer. The critical step in understanding activation via homodimerization and/or heterodimerization will be to elucidate the relative homo-and heterotypic affinities of the different receptor domains within the cell membrane. Recent experiments have similarly extracted the relative contributions of various domains in FGFR and VEGFR [36,37].

One critical question that remains is how ectodomain dimerization translates across the membrane to asymmetric kinase dimerization. Recent results demonstrated that the explanation likely lies in the structure and dynamics of the TM and membrane proximal domains [38]. The juxtamembrane (JM) domain plays an important role in both receptor autoinhibition as well as in activation [39,40]. Mutation of the JM domain abolishes EGFR activity, suggesting the JM domain plays a role in activation [41,42]. A crystal structure of the EGFR kinase dimer which included JM residues demonstrated that residues within the JM region form extensive interactions with the neighboring kinase and stabilize the kinase dimer (Fig. 1B, right, see arrowhead) [43,44]. Biochemical results suggested an autoinhibitory role of a second region in the JM domain consisting of a series of basic residues that interact with the negatively charged plasma membrane surface [45]. Therefore, this previously unstudied stretch of amino acids may simultaneously play a role in receptor autoinhibition and activation via protein-lipid and protein-protein interactions, respectively. The competing roles of the JM domain suggests that the key to signal propagation likely includes subtle changes within the TM domain—whether oligomerization, conformational change, or both—and highlights the need for structural and biophysical experiments of the intact receptor within the native plasma membrane.

2.2. EGFR activation – Alternative hypotheses

Crystal structures as well as biochemical and biophysical results collectively suggest a mechanism by which ligand-induced dimerization of EGFR and other ErbB receptors initiates signaling, however this model has historically been challenged by alternative hypotheses. For example, the ligand-induced EGFR dimer model fails to capture the observed complexities in EGF binding, including the curious concave-up Scatchard binding plots [46] and the presence of high- and low-affinity receptor states [47,48]. However, these different affinity receptor states cannot be explained in the context of the tethered and extended receptor structures alone [49–51] nor can they be explained purely within an equilibrium of receptor monomers and dimers [52]. More recent models suggest the complexities in ligand-receptor interactions arise from negative cooperativity of EGF-EGFR binding [53], which requires binding of one EGF ligand to a preformed receptor dimer (after which, a second ligand binds with lower affinity). The hypothesis of preformed, ligand-independent receptor dimers has been part of the activation mechanism for decades [54]. Several groups have shown that EGFR exists as preformed dimers [55–57], and these results include the use of advanced imaging modalities [58–61]. It remains unknown what fraction of EGFR within the plasma membrane exists as preformed dimers—estimates range between 5% and 100%—however, preformed dimers are nonetheless a requisite for negative cooperativity. A crystal structure of the Drosophila EGFR ectodomain solidifies this negative cooperativity model by illustrating that the first ligand binding event imposes steric constraints within the opposite ligand binding pocket, reducing the affinity for a second ligand [62]. Although human and Drosophila EGFR are primarily monomeric in solution, LET-23, the C. elegans orthologue of EGFR, is constitutively dimeric and is activated in the absence of changes in oligomeric state [63]. Further unifying models of C. elegans, Drosophila, and human EGFR, it was found that that a single ligand is sufficient for activation of EGFR dimers [64]. More recently, it has been suggested that EGFR forms organized aggregates within the plasma membrane [65,66], including the possibility of EGFR tetramers [67] and multimers [68], and such higher order association and organization is also suggested for other ErbB receptors [69–71].

2.3. Tumor necrosis factor receptors: Dimers, trimers and oligomers

Unlike the ErbB family, discussed above, the mechanism of activation of TNFRs is still not clear, nor does the range of crystal structures converge to a single model. A crystal structure of lymphotoxin-α (LTα) bound to TNFR1 was solved in 1993, showing an axisymmetric complex of three tightly interacting ligand protomers and three noninteracting receptors, each found at the groove formed by two adjacent ligand units (Fig. 1C, right) [72]. Separately, the unliganded TNFR1 crystalized as a receptor dimer with extensive interactions in the membrane distal region, known as the pre-ligand assembly domain (PLAD, Fig. 1C, left) [73]. Importantly, there are no immediately apparent differences in backbone conformation of the monomers in the unliganded dimer and ligand-bound trimer structures. This led to the conclusion that TNFR1 activation involves no conformational changes, an assumption we have challenged and that we will discuss at length below. Additionally, the residues in TNFR1 responsible for dimeric receptor-receptor interactions are structurally distinct from those that bind ligand [74–76]. This has left open the somewhat complicated possibility that receptor dimers and ligand-mediated trimers may both be part of an as-yet-undetermined signaling complex. Below, we will discuss in detail recent progress that has been made in reconciling the dimeric and trimeric structures.

TNFR members are structurally homologous in their ligand-bound complexed state, largely owing to the trimeric nature of the apo ligands such as LTα, Fas ligand (FasL), and the TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) [8,77]. Structurally homologous complexes of other TNFR ectodomains were solved, including TNFR2 [78], death receptor 5 (DR5, or TRAIL-R2) [9–11], decoy receptor 3 (DcR3) [79], and RANKL/Osteoprotegerin [80]. Among these, the structural homology is striking; three tightly interacting ligand molecules coordinate the assembly of three distal and non-interacting receptor molecules. Based on these crystal structures, the physical mechanism of TNFR signal initiation was believed to occur by ligand-induced and ligand-mediated coordination of three receptor units into an axisymmetric trimer. However many TNFRs, including Fas and TRAIL receptors, also contain homologous PLADs in their membrane distal region, the first of several modular Cys-rich domains (CRDs) [81,82]. In the case of TNFR1, structures demonstrate pre-ligand dimerization via the PLAD [73], however other experiments suggest pre-ligand trimerization [76]. Despite the early focus on the PLAD, we and others have recently demonstrated a clear role for the TM domain and intracellular contacts in dimerization and activity of TNFRs [3,83–85]. However, whether these non-PLAD interactions are conserved and how essential they are among all TNFRs remains to be seen.

Receptor dimerization in response to ligand is critical for the activity of other TNFR members, notably the neurotrophin receptor p75-NTR, for which a dimeric ligand-receptor crystal structure exists [86]. Within the cell a series of recent crystal structures of the p75-NTR intracellular death domain (DD), including the DD dimer and the DD in complex with downstream factor RIP2, shows that DD dimerization occludes the RIP2 binding site [87]. This suggests a mechanistic model in which the DD dimer inhibits signaling, while separation or breaking of these dimers allows for the recruitment of downstream factors necessary for activation of the NF-kB pathway. This model is consistent with our simulations and experiments of the TNFR1 complex that showed that activation correlates with separation of the intracellular regions [84].

Crystal structures of TNFR intracellular domains give a similarly opaque view of the mechanism of activation of TNFRs. The most widely crystalized intracellular domain belongs to Fas (CD95, Apo-1), a death-inducing member of the TNFR superfamily. Fas is activated upon extracellular binding to FasL and initiates apoptosis via activation of the intracellular DD and subsequent DD-mediated recruitment of the Fas-associated death domain (FADD). FasL was crystalized as a trimer (PDB ID 4MSV) and thus the ligand-receptor complex is presumed to be trimeric. Confounding this, the intracellular Fas-DD structure has been solved in a range of stoichiometries. Monomeric Fas-DD is comprised of six antiparallel and amphipathic helices (Fig. 1E, middle, PDB ID 1DDF) [88]. Interestingly, the Fas-DD has also been crystalized as a dimer (Fig. 1E, left, PDB ID 3EZQ) [3] and as a pentamer (Fig. 1E, right, PDB ID 3OQ9) [1]. In both the dimeric and pentameric structure, the Fas-DD is complexed with downstream FADD molecules, suggesting both structures are signaling competent. In the case of dimeric Fas-DD, there is a significant conformational shift relative to the monomeric Fas-DD, specifically, the C-terminal α-helix undergoes a rotation and becomes an extension of the previous α-helix (Fig. 1E, compare α6, center and left panels). This conformational change exposes the dimer interaction surface within the Fas-DD and also creates a binding pocket for FADD [3]. Conversely, the oligomeric Fas-DD undergoes no conformational change; RMSD of alignment is ~0.3 angstroms between Fas-DD in monomeric and oligomeric conformations (Fig. 1E, compare α5/α6 center and right), and the interface for FADD is created by three adjacent Fas-DD protomers within the circular, pentameric assembly. These two crystal structures suggest radically different models for the mechanism of activation; it remains unclear whether extracellular trimerization of Fas receptor by FasL leads to intracellular dimers, pentamers, or both. Furthermore, it is unknown whether the dimer-induced conformational change within the Fas-DD is necessary for activity.

2.4. ErbB receptor crystal structures offer a putative model of dimer-driven activation whereas TNFR crystal structures provide a multitude of oligomeric assemblies and no consensus mechanism of activation

Structures of EGFR and other ErbB receptors suggest activation via ligand-induced, receptor-mediated dimerization [13], although additional lines of evidence suggest alternative hypotheses, as described above. In contrast, TNFRs show considerable structural divergence. Given the diverse set of TNFR receptor structures and stoichiometries, it remains difficult to attribute any subset of structures to a particular activation state. In light of the stoichiometric mismatches between the outside and inside of the cell, what are we missing? It is certainly possible for ectodomain dimers and trimers to exist simultaneously since the residues involved in each interaction are spatially distinct. But is it possible that the mechanism of death domain activation includes both the formation of dimers and also higher order oligomers? Is it likely that the downstream FADD protein binds to the death domain regardless of its conformation? These questions are not easily answered, but they point to the need to study full-length proteins using non-crystallographic techniques. Furthermore, it is possible that the key to connecting these disparate structures lies within the membrane.

3. The often overlooked transmembrane domain and the emergence of NMR

Physical and biochemical properties of the plasma membrane play a critical role in determining structure, conformational dynamics, and oligomerization of membrane receptors [89–91]. As such, it is critical to understand and characterize the structure and dynamics of the TM domain within the plasma membrane. However, the notable rarity of TM domain structures from single-pass membrane receptors reflects the difficulty in obtaining atomistic detail of TM domains within a native membrane or membrane-like environment. Thus, until recently it has been exceedingly difficult to establish the connection between the TM domain and the structure, conformational dynamics and activation of the full-length receptor.

Solution-state NMR has emerged as the primary method to resolve single-pass TM helices of membrane receptors. These structures include monomeric, dimeric, trimeric, and oligomeric assemblies of TM domains, and offer a first glimpse into the role of TM helices in receptor signal transduction. To date, there are 17 NMR structures of the helical TM domains of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs): primarily ErbB receptors, Eph receptors, and VEGFR2 (see Table 1, acquired from the Orientations of Proteins in Membranes, OPM, database [92]). By contrast, only four structures from two separate proteins are available from the TNFR family. While some of the available TM domain structures corroborate models of activation derived from the structures of extracellular and intracellular domains, in other instances it is not as clear whether or how the observed TM interaction(s) are compatible with other known structures.

Table 1.

List of available NMR structures of α-helical TM domains for Receptor Tyrosine Kinase (RTK) and Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNFR) receptor families. Obtained from the OPM database [92].

| Protein Family | Species | PDB ID | Description | Oligomeric state | Thickness (Å) | Tilt ° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RTK | Human | 2ks1 | ErbB1:ErbB2 | Heterodimer | 32±2.5 | 15±5 |

| Human | 2l2t | ErbB4 | Dimer | 32.4±1.5 | 4±2 | |

| Human | 2jwa | ErbB2 | Dimer | 31.9±2.9 | 13±9 | |

| Human | 2k1k | EphA1 | Dimer | 30.2±1.5 | 0±5 | |

| Human | 2k9y | EphA2 | Dimer | 31.8±3.2 | 12±14 | |

| Human | 2l9u | ErbB3 | Dimer | 33.8±2.4 | 16±5 | |

| Rat | 1iij | ErbB2 | Monomer | 31.8±2.8 | 27±2 | |

| Human | 2l6w | PDGFR | Dimer | 34.8±0.8 | 18±1 | |

| Human | 2m20 | ErbB1 | Dimer | 34±3 | 0±3 | |

| Human | 2lzl | FGFR3 | Dimer | 30±4.2 | 1±3 | |

| Human | 2m0b | ErbB1 | Dimer | 31.8±2.5 | 15±2 | |

| Human | 2m59 | VEGFR2 | Dimer | 31.8±1.2 | 2±2 | |

| Human | 2mfr | Insulin receptor | Monomer | 29.8±4.8 | 41±1 | |

| Human | 2meu | VEGFR2 | Dimer | 32±1.7 | 0±2 | |

| Human | 2met | VEGFR2 | Trimer | 31.8±1.5 | 1±1 | |

| Human | 2k1l | EphA1 | Dimer | 28.8±1.2 | 5±3 | |

| Human | 2n2a | ErbB2 | Dimer | 35±3.6 | 14±2 | |

|

| ||||||

| TNFR | Rat | 2mic | p75-NTR | Dimer | 29.2±2.5 | 7±4 |

| Rat | 2mjo | p75-NTR | Dimer | 22.6±3.5 | 2±1 | |

| Mouse | 2na6 | Fas | Trimer | 27.6±2.1 | 6±2 | |

| Human | 2na7 | Fas C178S mutant | Trimer | 26.8±0.6 | 1±1 | |

The atomistic structure of EGFR/ErbB receptor TM interactions have only recently been resolved [93–95]. The EGFR TM domain structure was solved and found to be dimeric. Two unique conformations were observed, each utilizing a different TM dimer interface (Fig. 2A,B). Endres et al. solved the structure of ErbB1 residues 618–673, representing the complete TM domain and the first ~30 residues of the intracellular JM region in DMPC/DHPC bicelles [96]. The structure shows that TM helices interact via an N-terminal GxxxG (GG4)-like motif [97], and the intracellular JM residues are helical and associate in an antiparallel conformation, consistent with the active receptor conformation (Fig. 2A). The N-terminal GG4-like TM association is similar to an ErbB1:ErbB2 TM heterodimer structure [93], a curiously asymmetric TM dimer given the differing helical lengths, and provides a basis by which to study heterodimeric assembly between EGFR and ErbB2. Recently, an additional structure of the EGFR TM domain was solved using NMR of EGFR in its inactive state (Fig. 2B) [95]. Here, Bocharov et al. use the isolated TM domain with only a small number of intracellular JM residues, and the NMR structure was solved in DPC micelles. The resulting structure shows TM association via the C-terminal GG4-like motif and close proximity of the JM residues [95], consistent with previous models of this TM/JM conformation [7,96] and a likely inactive receptor state. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that the physical properties of the local TM environment (DMPC/DHPC bicelles vs. DPC micelles) directly influences the structure of the TM and membrane proximal domains [98].

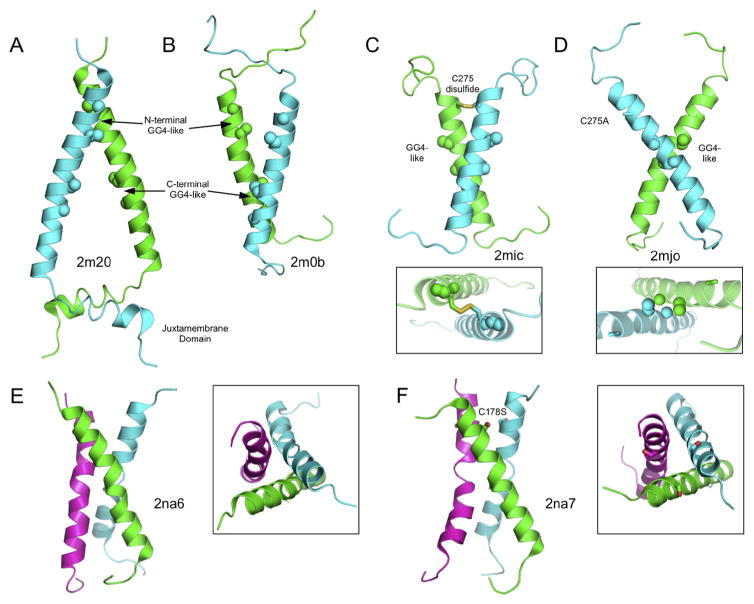

Fig. 2. NMR structures offer a view of physical interactions within the membrane and provide a link between extra- and intracellular structures.

(A–B) NMR structures of EGFR with and without the juxtamembrane (JM) residues highlight the structures of active and inactive TM dimers, and further exemplify the importance of membrane proximal residues in TM structure and function. (A) The NMR structure of the EGFR TM domain including intracellular JM residues (PDB ID 2M20) [96] represents the active TM dimer and illustrates the TM interaction via the N-terminal GG4-like motif and anti-parallel helix dimer structure of the intracellular JM domain. (B) By excluding the JM residues, Bocharov et al. found an alternative interaction interface via the C-terminal GG4-like motif (PDB ID 2M0B) [95], representing the inactive TM dimer conformation. (C–D) NMR structures of wild type and mutated TM domains of the p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75-NTR) suggest two independent and stable interaction motifs. (C) The wild type p75-NTR TM domain forms a disulfide-linked dimer via C275 (PDB ID 2MIC) [101] that is critical for ligand-induced signaling. (D) Structure of the mutated C275A p75-NTR TM domain (PDB ID 2MJO) [101] renders the receptor functionally inactive. However, the TM domains still interact via an alternative AxxxG motif on the opposite face of the TM α-helix and in a left-handed helical dimer configuration. The AxxxG does not play a role in TM interactions within the plasma membrane, but is rather involved in p75-NTR intracellular processing and cleavage by γ-secretase [101]. (E–F) NMR structures of mouse (E, PDB ID 2NA6) and human (F, PDB ID 2NA7) Fas TM domains in bicelles showing trimeric assemblies suggesting a role for TM interactions in Fas activation [2]. Notably the human Fas TM domain, but not the mouse, contains a cysteine residue, though there is no known functional role of this Cys disulfide bond formation in Fas as there is with DR5 and p75-NTR. Interestingly, by mutating this Cys residue, Fu et al. were able to retain trimer formation, however it is not clear what structure the native purified human Fas TM domain adopts. While this Cys residue is primarily conserved only in primates, it is interesting to speculate about a potential role of disulfide bond formation in Fas signaling.

Activation of p75-NTR is mediated by ligand-induced dimerization of ectodomains, discussed above. Vilar et al. previously demonstrated that p75-NTR dimerization is stabilized by a covalent and ligand-dependent disulfide bond within the TM domain [99,100]. Mutation of the conserved TM Cys residue did not alter the receptor oligomeric state but did cause changes in intracellular receptor conformation, determined by fluorescence anisotropy imaging, and prevented recruitment of intracellular factors [99]. These results clearly demonstrate that receptor activation is highly sensitive to the TM domain. A recent set of NMR structures in DPC micelles show these receptor conformational states manifested in multiple structures of the TM domain of p75-NTR [101]. The structure of the wild type TM domain forms a disulfide (C257)-linked, right-handed parallel dimer and most likely represents the active conformation (Fig. 2C). The structure of the mutated C257A TM domain shows interesting structural changes, including engagement of the GG4-like motif in a left-handed dimer configuration (Fig. 2D), however the primary function of this GG4-motif dimer lies in proteolysis rather than signaling-related interactions [101,102]. Changes in receptor structure or conformational dynamics in receptor processing events remain unexplored.

The specific role, prevalence, and evolutionary conservation of Cys-mediated disulfide bonds between TM domains is largely unknown. Ligand-induced, disulfidemediated dimers exist within the silkworm RTK, Torso, a receptor for prothoracicotropic hormone (PTTH) [103]. DR5 also exhibits ligand-dependent disulfide bond formation with the TM domain [83]. However this Cys residue is missing from an alternative, but active, isoform of DR5, suggesting that disulfide bond formation may be dispensable in signaling (discussed further below).

The Fas TM domain has a single Cys residue in a position similar to that of DR5, though it is unknown whether this residue causes disulfide linked dimers nor whether it is involved in signaling. Recent NMR structures of Fas TM domains suggest the TM forms trimeric assemblies (Fig. 2E,F), although the TM Cys is mutated in the structure of the human Fas TM domain [2]. The authors argue that this Cys residue is not conserved, and indeed it is primarily conserved only in primate mammals. In the absence of this TM Cys residue, for example in the C178S mutated human TM (Fig. 2F) or the mouse TM (Fig. 2E), NMR structures show the formation of helical trimers, however given that the TM helices interact in their N-terminal region and the Cys residues are less than 10 angstroms apart, it is interesting to consider the possibility of TM disulfides in human Fas. Furthermore, while the TM trimer fits the model of ligand-receptor ectodomain trimer structures, it is unknown whether the extracellular residues immediately adjacent to the TM domain provide enough conformational flexibility for TM domain interactions from a single trimeric ligand-receptor, as each receptor ectodomain protomer is separated by ~50 angstroms. Additionally, the Fas TM trimer is difficult to reconcile with the dimeric and oligomeric structure of the intracellular Fas-DD, as discussed above.

4. From the ectodomain to the cytosol via the transmembrane domain: oligomerization and conformational dynamics

Piecing together available data of disparate receptor domains becomes possible because of tools that simultaneously report on structure, dynamics, and interactions of intact membrane receptors within the plasma membrane. The application of advanced imaging techniques allows for high spatial and temporal resolution experiments of transmembrane receptors. Collectively, these tools complement X-ray and NMR by offering biophysical insights into receptor behavior at both an ensemble level as well as at the single molecule level.

4.1. FRET/FLIM and quantitative imaging provide nanometer-scale information about receptor structure and interactions in response to ligand-binding in FGFR

Extracellular ligand binding serves to stabilize receptor dimers in many systems, however increasing lines of evidence suggest the formation of pre-ligand assemblies. These ligand-independent interactions, whether stable or transient, challenge the long-standing view that activation by ligand drives membrane receptors from a purely inactive and monomeric state to an active oligomeric state. Such pre-ligand interactions have been characterized in a number of receptor families that bear no sequence or structural homology including TNFRs [75,76,104], growth factor receptors including ErbB receptors (described above), FGFRs [37], VEGFRs [36], and even cytokine receptors such as IL-17Rs [105]. Furthermore, targeting pre-ligand interactions as a means to disrupt signaling may have clinical value, for example in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis by targeting TNFR pre-ligand assembly [106].

The formation of favorable receptor interactions in the absence of ligand suggests that ligand-induced signaling events are driven in part by subtle structural changes in the ectodomain that are propagated through the TM domain and into the cell. FRET analysis using strategically placed fluorescent probes allows for quantification of ligand-independent and ligand-bound structure and oligomerization dynamics. For example, placement of donor and acceptor probes within the intracellular region allows for nanometer-scale assessment of intracellular structural changes that result from extracellular perturbations, such as ligand binding.

FGFR signaling, like other growth factor receptors, was initially thought to be triggered by ligand-induced receptor dimerization (for review see [107]). However, like EGFR, FGFR signal initiation is more complex than a ligand-induced monomer-to-dimer transition, and recent time-resolved FRET results have challenged this hypothesis by demonstrating the presence of stable, pre-ligand dimers of FGFR1 on the surface of live cells independent of surface expression [108]. Dimerization of FGFR3 is driven in part by interactions in the TM and JM domains [109, 110], however the relative contribution of each domain is unknown. Such results yield critical questions about the ligand-independent and ligand-bound state of FGFRs. Is pre-ligand assembly a conserved mechanism among FGFRs? What domain(s) contribute to ligand-independent FGFR interactions? How does binding to ligand alter the receptor dimer stability or structure, and do changes in dimer structure and stability differ among FGFR ligands?

In light of these questions, Sarabipour et al. recently established the relationship between ligand occupancy, receptor structure, and function of FGFR1, FGFR2, and FGFR3 (Fig. 3) [37]. By conjugating a FRET pair downstream of the transmembrane domain, ligand-independent interactions were observed for FGFR1, FGFR2 and FGFR3 using time-resolved FRET and quantitative imaging. One particularly useful aspect of dynamic measurements like FRET is that they allow for thermodynamic analysis of oligomerization and conformational changes associated with activation. Rather than a structure-based approach, an alternative way to effectively piece together domains is through energy decomposition: to reconstruct the full energetics of activation from the energetics of individual domains. For full-length receptors, the ligand-independent free energy of association ranged from −4.3 kcal/mol (FGFR1) to −6.3 kcal/mol (FGFR3) (Fig. 3A). The isolated TM domain strongly dimerized in all three receptors (Fig. 3B, red lines) with free energy of association between −5 and −6 kcal/mol, suggesting the TM domains provide a tremendous driving force for interaction that are negatively regulated by soluble receptor domains. Removal of the intracellular domain decreased dimer formation for FGFR2 and FGFR3 but not FGFR1 relative to their respective full-length receptors (Fig. 3B, green lines) indicating that the ectodomain plays a different role in ligand-independent dimerization of each receptor type.

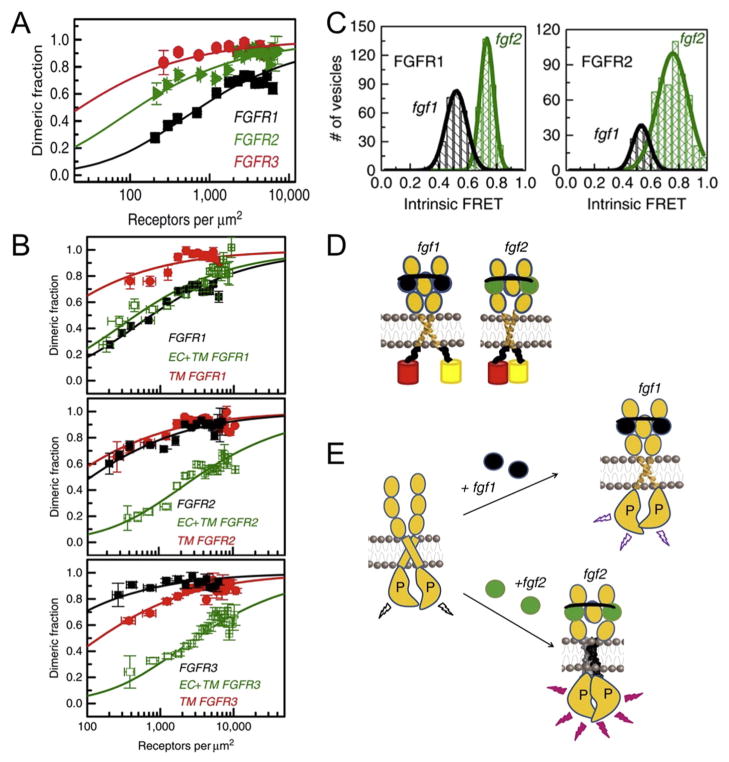

Fig. 3. Using quantitative imaging FRET (QI-FRET), FGF receptors were shown to form dimers in the absence of ligand, and these receptor dimers are minimally phosphorylated. Signal initiation by fgf1 and fgf2 ligands trigger distinct structural changes leading to different levels of phosphorylation.

(A) FGFR1, FGFR2, and FGFR3 receptor dimer fraction as a function of receptor concentration in the plasma membrane shows ligand-independent dimerization of all FGFRs. (B) Truncation of FGFR1 (top), FGFR2 (middle), and FGFR3 (bottom) demonstrates the relative contribution of different receptor domains toward ligand-independent dimerization. (C) Histograms and distributions of intrinsic FRET values for FGFR1 and FGFR2 in the presence of ligands fgf1 and fgf2, extracted from the two component fit. (D) Graphical representation summarizing the results establishing a relationship between receptor ectodomain ligand occupancy and the separation of the TM and intracellular domains. Ligands fgf1 and fgf2 cause distinguishable structural changes within a preformed receptor dimer leading to interactions within the cytoplasmic domains and subsequent phosphorylation. (E) A model of activation for FGFRs where receptors form minimally active ligand-independent dimers. Binding of the receptor dimer to fgf1 or fgf2 causes structural changes that bring the cytoplasmic domains in close proximity leading to activation and phosphorylation. The figure is adapted from Sarabipour et al. (2016) [37], reproduced with the author’s permission.

Given the extent to which FGFRs interact in the absence of ligand, the critical unanswered question is precisely how the ligands alter the receptor structure or interaction kinetics to induce signaling. Comparison of the intrinsic FRET for FGFRs bound to their ligands, fgf1 or fgf2, demonstrated a consistent structural difference depending on ligand occupancy. The fgf2:FGFR complex showed a higher intrinsic FRET, and therefore a tighter packing of TM and intracellular domains relative to fgf1:FGFR (Fig. 3C,D), and FRET was proportional to FGFR phosphorylation, indicating a relationship between kinase separation and activity [37]. Collectively, these results clearly demonstrate the presence of three structurally distinct receptor conformations: unliganded, fgf1-bound, and fgf2-bound (Fig. 3D). The resulting mechanism of activation in pre-assembled FGFRs couples extracellular domain and TM domain structure with the activation of intracellular domains primarily via changes in receptor conformation as opposed to simply dimerization (Fig. 3E). The structure of the FGFR3 TM domain in DPC/SDS micelles confirms this hypothesis, where a number of pathogenic mutations fall outside the TM interaction interface [111], suggesting a complex structural rearrangement and the presence of multiple modes of TM dimerization. Similar mechanisms were found for insulin-like growth factor receptor 1 [112] and VEGFR-2 [36], and it is interesting to speculate whether such mechanisms exist in other receptors, even those with no structural homology to growth factor receptors or other RTKs.

4.2. A unifying model of TNFR architecture? Reconciling DR5 trimers and dimers

The structural mechanism of activation of TNFRs remains unknown, and the divergence between the extracellular and intracellular regions of TNFRs, described above, raises several confounding questions. Does the crystalized soluble ectodomain in isolation lack key residues that mediate dimeric receptor interactions? Does engagement by TRAIL ligand (or antibody agonist) induce structural changes leading to receptor dimerization? Does the full-length DR5, including TM and intracellular domains, somehow simultaneously engage in dimeric and trimeric interactions via a ligand-receptor network model (Fig. 4A, and as previously described for TNFR1 [73])? The key to answering these questions lies in combining experiments in cells using the full-length receptor, and simultaneously characterizing stoichiometry and dynamics.

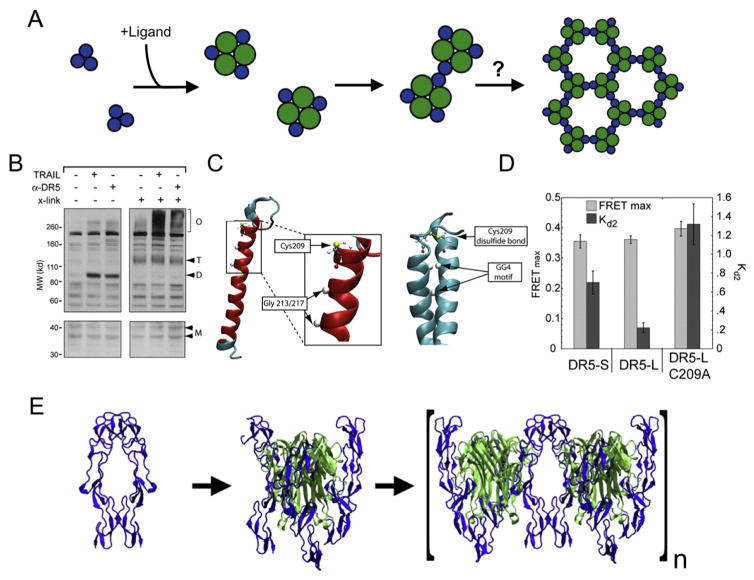

Fig. 4. Death receptor 5 functions within networks organized by trimeric ligands and dimeric receptors.

(A) A schematic model for TNFR1 and structurally homologous TNFR superfamily members where signal initiation occurs via the formation of a dimer-of-trimers or via hexagonal networks. (B) Activation of DR5 by either TRAIL ligand or an antibody agonist causes the formation of disulfide-linked receptor dimers as shown by non-reducing SDS-PAGE (left). Monomer, dimer, trimer and oligomer species are noted by M, D, T, and O, respectively. Upon crosslinking using a non-specific chemical crosslinker (right), the disulfide dimer is found within high molecular weight species, indicating the formation of large networks organized by receptor dimers and ligand trimers as in (A). (C) Molecular modeling of the Cys-containing TM domain monomer (left) and disulfide-linked dimer (right) shows the cysteine residue on the same interface as a GG4-motif. Residues within the membrane, including both the Cys residue and the GxxxG motif, are shown in red. (D) FRET data extracted parameters are the maximum FRET efficiency, FRETmax, and the relative dissociation constant (Kd2), yielding information about the structure and dynamics of complex formation. (E) A structural model of activation based on TNFR1, from ligand-independent dimers (left) to ligand-receptor trimers, and ultimately a dimer-of trimers interacting via receptor-receptor interactions. Panels (A)-(D) of this figure are adapted from Valley et al. (2012) [83], reproduced with the author’s permission.

By using a unique combination of cross-linkers, we showed that TRAIL and antibody agonists induce dimerization of DR5 TM domains, and that these dimers exist within larger ligand-receptor complexes [83]. We found that either TRAIL or antibody agonist induces disulfide-mediated dimerization of DR5 (Fig. 4B, lanes 1–3). Inclusion of a non-specific cross-linker eliminates the DR5 dimer band, as the dimer species exists within higher oligomers (Fig. 4B, lanes 4–6). These results demonstrate that the non-covalent interaction between either TRAIL or agonist and DR5 induces a structural and/or oligomeric change that allows for covalent, disulfide dimerization of the receptor. Furthermore, these data are consistent with a model in which trimeric ligand-receptor complexes are held together at dimeric receptor junctions (Fig. 4A).

A single Cys residue (C209) in the TM region of the longer isoform of DR5 (DR5-L) was identified as responsible for this disulfide-linked dimer. Molecular modeling of DR5-L, both monomeric (Fig. 4C, left) and in a disulfide-linked dimer (Fig. 4C, right), demonstrates engagement of a GG4 motif on the same helical face as the disulfide Cys residue. The GG4-mediated dimer is likely important in TM domain dimer stability of both isoforms of DR5. FRET analysis of the DR5 isoforms and a C209A mutant showed a decrease in FRET between probes placed immediately inside the membrane suggesting a difference in structure and/or dimerization affinity. Elucidation of structural (FRETmax) and kinetic (i.e. relative receptor affinity, Kd2) parameters via curve fits to FRET data showed a nearly identical FRETmax (Fig. 4D), indicating the resulting dimer structure is indistinguishable for both DR5 isoforms (without and with a TM disulfide) as well as in the Cys mutant. The difference in ensemble-averaged FRET is primarily a result of changes in receptor-receptor interaction affinity, shown as differences in Kd2 (Fig. 4D), with the weakest propensity for dimerization belonging to DR5-L C209A. These results lead to a model of activation similar to TNFR1 whereby receptors in the absence of ligand are dimeric. Ligand binding results in trimerization and ultimately in clusters of trimers tethered via dimeric receptor interactions (Fig. 4E). We are left still with an unanswered and somewhat vexing question, namely what is the evolutionary advantage of a Cys residue within the TM domain in DR5-L?

Whether these dimers, subsumed in larger oligomeric ligand-receptor complexes, are essential to signaling has been an open question. We have recently produced a first piece of evidence for this, somewhat unexpectedly by studying the relationship between DR5 oligomerization, membrane cholesterol, and activation. A number of TNFR members have been shown to signal via migration to cholesterol-rich membrane regions. TNFR1 was shown to relocate to cholesterol- and sphingolipid-rich membrane domains upon binding to TNFα, and within these microdomains the receptor recruits downstream components [113]. Fas has similarly been shown to migrate to cholesterol-rich membrane regions in response to ligand [114], however there are additional results suggesting this is a ligand-independent mechanism to increase ligand sensitivity [115]. Results by Song et al. showed that TRAIL-induced activation of DR5, measured by activation of Caspase-8, is sensitive to the presence of cholesterol in the membrane [116]. Our recent results demonstrate that plasma membrane physical and biochemical properties facilitate DR5 dimer formation [85]. We first showed in cells that DR5 agonists induce migration of the receptor to cholesterol-rich membrane regions, and depletion of membrane cholesterol using methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) reduces ligand-induced activity. Using a novel quantification scheme, we then showed that cholesterol extraction from the membrane does not prevent the formation of ligand-receptor networks. This implies that networks are not just random aggregates, but rather have a specific structural architecture that can be active or inactive. The cholesterol extraction does, on the other hand, significantly diminish the level of disulfide-linked receptor dimers. This suggests that TM domain dimers are a critical component in activation of DR5 [85].

These results with full-length receptors in cells were corroborated using the isolated TM domain in synthetic bilayers. We showed that the degree of disulfide dimerization of DR5 was directly related to bilayer thickness, which is determined by the mol fraction of cholesterol in the bilayer. Using molecular dynamics simulations, we then showed that thicker bilayers (e.g. those containing cholesterol) increase the length of the TM domain helix by adding helical turns at the N-terminal region of the TM domain. This increases the likelihood that C209 sits within a stable helical turn [85]. We hypothesized that this results in an increased propensity for dimerization by stabilizing a potential Cys-Cys interaction interface.

4.3. Combining experiments and simulations; a multi-scaled approach to connect structure and dynamics

The combination of benchtop experiments and computational modeling has the power to bridge our understanding of phenomenological, live-cell observations and the molecular level details of receptor dynamics, interactions, and ultimately activation. Predictive insights from molecular simulations can guide experimental design, while experiments can support modeling predictions and lend legitimacy to those findings. This multi-technology, multi-scale approach has been used to describe structural coupling of EGFR across the plasma membrane as well as to propose a novel activation mechanism for members of the TNFR superfamily.

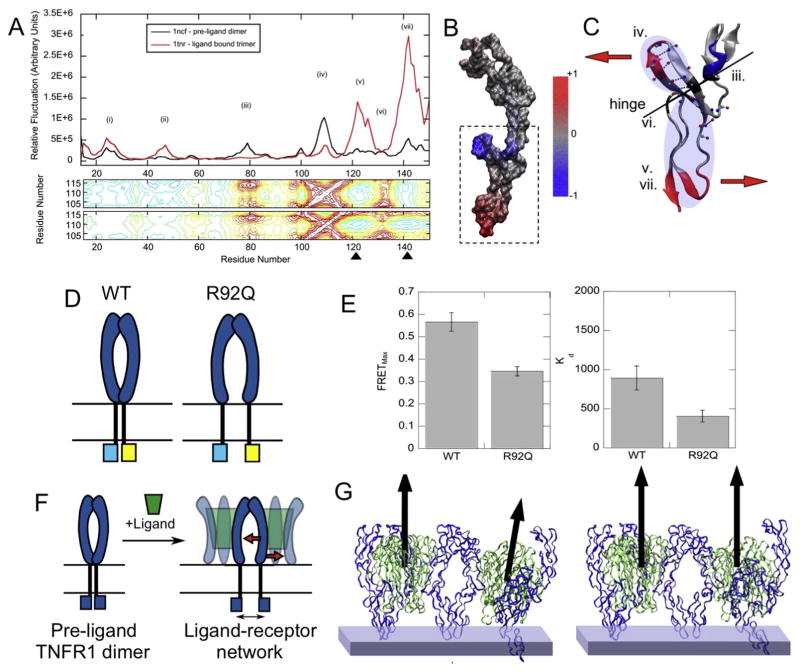

In order to begin to build a putative model of the structural coupling and dynamics across the plasma membrane during TNFR activation, we combined FRET experiments in cells on full-length TNFR1 and DR5, EPR on isolated TM domains and several modes of computational modeling. Our major conclusion has been that activation involves ligand-induced separation, or ‘opening’ of TM helices in a scissors-like manner. We started with a structural alignment of dimeric TNFR1 and trimeric LTα-TNFR1 to create a dimer-of-trimers model (see Fig. 4E). Surprisingly, this process revealed that a ligand-receptor lattice did not remain flat as we expect it should in the membrane plane, with a measured angle of ~35° between adjacent ligand-receptor trimers, a considerable and unlikely structural contortion [84]. To accommodate both ligand-receptor trimers and receptor-receptor dimers, a backbone conformational change in the receptor extracellular domain is required. Computational normal mode analysis of the receptor dimer and ligand-receptor trimer indicated an increase in residue mobility in the membrane-proximal residues (Fig. 5A, residues ~120–150) and retained mobility in the ligand-binding loop. The cross-correlation analysis showed that these two domains are dynamically coupled and anti-correlated, rotating about a hinge (Fig. 5B,C). Indeed, when we re-examined the overlay of dimer and trimer structures, we noted a far more significant deviation in the membrane proximal region than was previously recognized. Therefore, the computational modeling predicted that ligand binding acts as a lever on the membrane proximal and transmembrane domains, and could influence the arrangement of the cytosolic domains [84] (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5. Combinations of computational biology and structural biochemistry illustrate the subtle structural changes that initiate pathogenic TNFR1 signaling and suggest a mechanism for ligand-induced activity.

(A) Normal mode analysis of the ligand-bound TNFR1 trimer (red) and pre-ligand dimer (black) crystal structures. The ligand binding (iv) and membrane-proximal domains (v, vii) retain mobility in the ligand-bound structure and their motions are anti-correlated (black arrowheads). (B) The change in residue mobility between the pre-ligand and ligand-bound structures is color coded on a surface representation of the receptor. (C) The anti-correlated motion between the ligand-binding and membrane-proximal domains is shown schematically. (D) A schematic representation of the hypothetical mechanism of activation and placement of FRET probes. Separation of the cytosolic domains, as observed by FRET, is hypothesized to result in a signaling-competent architecture. (E) Live-cell FRET fits to a two-parameter saturable binding curve yielding FRETmax and Kd2. Results indicate a reduction of both in the constitutively active, R92Q mutant relative to the wild type. (F) A hypothetical mechanism of activation for ligand-induced TNFR1 where TM domains and cytosolic domains within a receptor dimer separate to accommodate ligand binding. (G) Normal mode analysis of two ligand-bound trimers coupled by the receptor dimer interface. The transition from the tilted, unmodified structure to the structure that would lay in-plane with the membrane can be achieved by applying the first and third lowest frequency normal modes. The figure is adapted from Lewis et al. (2012) [84], reproduced with the author’s permission.

This hypothesis was tested experimentally using FRET to compare the structure of TNFR1 with a constitutively active mutant, R92Q, to determine whether the cytosolic domains assume different configurations in the active and inactive states (Fig. 5D). The cytosolic domains were more separated in the active R92Q mutant than the inactive wild-type receptor (Fig. 5E). A similar conformational rearrangement of ectodomains translated through the membrane would flatten the assembled network formed by ligand and receptor (Fig. 5F,G). We did not perform these FRET experiments in the presence of ligand because the formation of larger oligomeric complexes confounds interpretation of FRET due to too high a density of FRET probes.

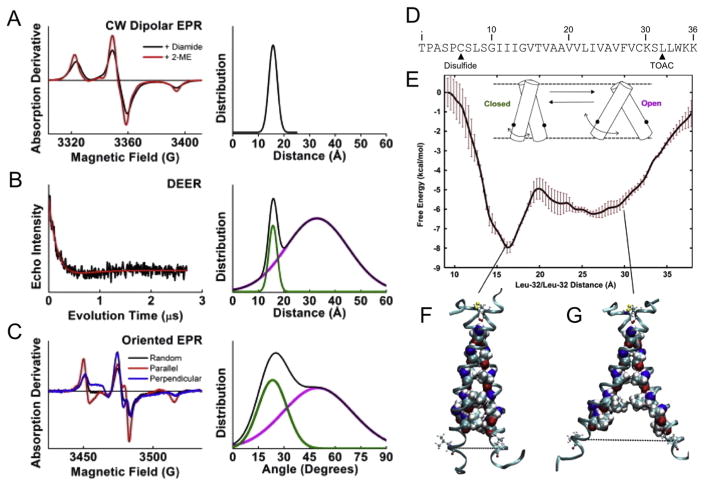

A conformational change in the extracellular domain, made manifest in the cytosolic domain, must be coupled to the receptor TM domain. Here, we switched to DR5 because little is known about the structure of the TNFR1 TM domain, whereas we had shown the existence of a di-sulfide linked TM domain dimer in DR5. EPR experiments on isolated TM domain dimers (Fig. 6A–C), supported by potential of mean force (PMF) calculations using computational molecular dynamics simulations (Fig. 6D,E), further promoted the likelihood of a conformational change in the DR5-L TM domain (Fig. 6F,G) [117]. DR5-L is both disulfide linked and has an obvious GG4 dimerization interface (Fig. 6D, discussed above), allowing the prediction of the dimer structure [83] and simplifying the selection of a reaction coordinate for our PMF calculation. A PMF calculated along a closed-to-open reaction coordinate revealed two energy minima matching remarkably well the distributions from the EPR measurements – a narrow minimum at 16 Å corresponding to a closed state and a broader, less favorable minimum centered at 27 Å corresponding to an open state (Fig. 6E). Analysis of the conformations along this reaction coordinate revealed that the GG4 domain remained intact in both the open and closed states. The ~3 kcal/mol free energy barrier separating the two states is accounted for by the loss of packing interactions in the cytosolic half of the protein along the dimer-dimer interface (Fig. 6F,G) [117]. It is yet unknown how the presence of the extracellular or intracellular domains influences this free energy landscape. Collectively, these results support a new mechanism of activation for TNFRs, where activation involves a structural change in the dimer, propagated via conformational rearrangement of the TM domains.

Fig. 6. Open and closed conformations of the isolated DR5-L TM domain of death receptor 5 support a new model of activation.

(A–C) EPR spectra (left) and the resulting structural distributions (right). (A) CW dipolar EPR spectra (left) and single Gaussian fit centered at 16 ± 2 angstroms (right). (B) DEER waveform (left) and two Gaussian fit (right). (C) CW EPR spectra (left) with the membrane-normal oriented parallel (red) and perpendicular (blue) to the field, and the resulting two Gaussian fit (right). Closed and open components are shown in green and magenta, respectively. The overall signal is shown in black. (D) The DR5-L sequence with the disulfide bonding cysteine and spin labeling sites indicated. (E) The potential of mean force along the closed-to-open conformational change and snapshots of the closed (F) and open (G) states. The relative broadness and depth of the low-energy minima correspond remarkably well with the observed populations in EPR experiments. The figure is adapted from Lewis et al. (2014) [117], reproduced with the author’s permission.

The difference in free energy between DR5 TM domain conformations represents an entirely different mechanism than the free energy of TM oligomerization presented above for FGFRs. The free energy of oligomerization of DR5 TM domains is unknown, however the receptors interact in the absence of ligand [81], and we have proposed a mechanism where ligand binding induces a conformational change within the TM domains [117] which alters the separation between intracellular domains [84]. FGFRs also interact in the absence of ligand, and the decomposed free energies presented are associated with oligomerization (Fig. 3A,B). Addition of ligand induces a structural change in FGFRs, similar to a proposed mechanism for IGFR activation [112], however the energy of this transition is unknown.

Two recent and coordinated studies combined experimental and simulation approaches to address EGFR conformation coupling between intracellular and extracellular domains. Recall that NMR structures of the TM and adjacent residues revealed the importance of JM residues in maintaining an active TM dimer (see Fig. 2A, above) [96]. Using the NMR structure, a model of the full-length EGFR was hand-built and then simulated in a lipid bilayer. The simulations revealed differences in the TM domain dimerization motif in the resting and ligand-bound states, as well as a critical activating role for membrane proximal residues through interaction with the lipid bilayer [7]. Furthermore, by simulating the full-length protein, a critical structural link was observed between the modes of TM interactions, JM structure, and kinase dimerization. Specifically, the active receptor conformation involves engagement via the N-terminal GG4-like motif, antiparallel JM helix interactions, and asymmetric kinase dimer conformation. In contrast, the inactive conformation yields TM domain interactions via the C-terminal GG4-like motif, a disordered JM, and the asymmetric kinase dimer is lost to a symmetric and inactive dimer, consistent with previously proposed models [118]. Collectively, these results challenge the model by which ligand binding induces dimerization of EGFR and propose a complex model where ligand induces subtle structural changes in the ectodomain that causes rotation of TM and cytosolic domains [55,119,120]. This model has been proposed for EGFR and other ErbB receptors [54] and reiterates the importance of the local lipid environment in signal transduction by organizing receptor assemblies [60,121–124]. Furthermore, such preformed interactions, subtle structural changes and TM rotations may be a common mechanism of activation among single-pass TM receptors, as previously proposed [125].

5. New experimental techniques are changing the game: single molecule tracking, super-resolution imaging, and electron microscopy

Recent advances in imaging have revolutionized the fields of fluorescence microscopy and structural biology. The incorporation of electron multiplying CCD or CMOS cameras [126,127] have led to the emergence of single molecule imaging, enabling the fluorescence-based imaging of individual receptor molecules within the membrane [128]. Furthermore, advances in data collection and image processing have enabled high-throughput methods in electron microscopy resulting in nanometer-scale reconstructions of large biological assemblies by incorporating crystal structural data [129,130]. Single molecule imaging provides a novel link between structural and cellular biology by contextualizing models of receptor interactions within the dynamic cellular environment. Electron microscopy enables near atomistic resolution imaging of full-length transmembrane receptors and thus provides a fundamental structural link across the plasma membrane. Collectively, these methods allow us to develop precise, though static, structural models of receptor interactions across extracellular, TM, and intracellular domains, and to subsequently test the dynamics and stability of those interactions within the dynamic cellular membrane.

5.1. Single particle tracking and super-resolution imaging offer a view of individual receptor molecules in the plasma membrane

Single particle tracking (SPT) emerged as a powerful tool to study diffusional dynamics and interactions of individual membrane receptors. While the nanometer resolution of FRET represents the highest attainable by fluorescence imaging, results are obscured by time- and ensemble averaging. In SPT, fluorescently-labeled receptor molecules are individually localized and tracked over time with tremendous spatial (~20 nm) and temporal (millisecond) resolution within the complex and crowded plasma membrane. The resulting molecular trajectories give information about the diffusional dynamics [131] and protein interactions [132].

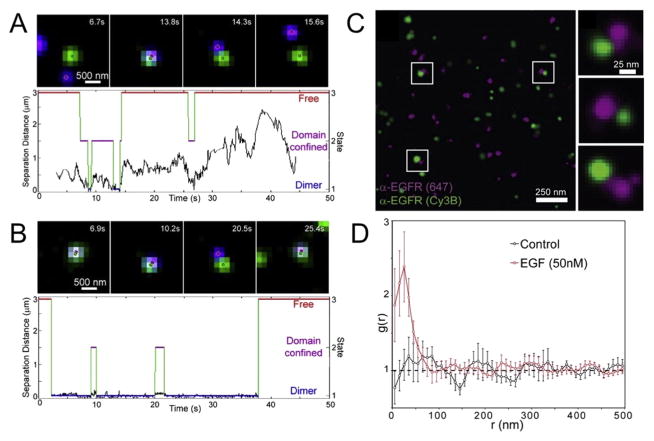

SPT and super-resolution imaging methods have been used extensively to study interactions of EGFR and ErbB receptors [61,132–136] and to a lesser extent TNFRs [137–139]. EGFR structure, dynamics and oligomerization/interactions have been widely studied using a variety of biophysical methods which also includes localization microscopy (discussed below), number and brightness [58], FRET and/or FLIM [120,133,135,140], fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) [141–144], fluorescence correlation/cross-correlation spectroscopy (FCS, FCCS) [59,60,145], photon counting histogram (PCH) and fluorescence intensity distribution analysis (FIDA) [146], spatial intensity distribution analysis (SpIDA) [147], and single molecule photobleaching and single molecule localization and photobleaching [61,66–68,135]. SPT results have collectively confirmed that ligand stabilizes receptor dimers within the plasma membrane. The earliest single molecule tracking experiments observed EGF binding, receptor dimerization, and phosphorylation of individual receptor molecules on the cell surface [61]. Other single molecule tracking experiments used a single color to quantify receptor dimerization kinetics by identifying dimers solely based on receptor diffusion [134]. However, the assumptions inherent in identifying dimers based on diffusion are problematic as diffusion is additionally related to intracellular signaling events [132].

The two-color SPT experiments by Low-Nam et al. were more illustrative, directly observing interactions of individual EGFR molecules within the plasma membrane based upon the proximity and correlated motion of spectrally distinct receptors [132]. The stability of receptor interactions was extracted using a Hidden Markov Model (HMM) analysis and maximum likelihood estimation to identify underlying ‘hidden’ biological states (i.e. dimeric or free receptor, and an intermediate co-confined state) based on the observable distance between receptors. Using the ligand-bound EGFR crystal structure dimer (Fig. 1A, right), dimers in SPT were identified based upon the separation between localized receptors. The experiments and HMM analysis demonstrated that EGFR forms highly transient dimers in the absence of ligand (Fig. 7A), whereas the EGF-EGFR complex shows stable receptor dimer formation (Fig. 7B) [132,133]. Such methods were also used to study interactions of other ErbB receptors [136], and constitutively active EGFR mutants that stabilize EGFR dimers in the absence of ligand [133]. Clinical tyrosine kinase inhibitors that target these mutants increased in the fraction and stability of EGFR homodimers [135], consistent with previous biochemical and structural studies [148]. These two-color SPT experiments with HMM analysis critically provide a quantitative and dynamic basis for receptor interactions. Static crystal structures give the false impression that receptor interactions are irreversible. SPT demonstrates their true dynamic behavior: individual receptors are continually associating and dissociating, and ligand merely biases this equilibrium toward a complexed state. Therefore, ligand-induced signal transduction does not depend on the formation of irreversible receptor interactions, but only on the formation of many moderately stable interactions that result in sustained signaling from the membrane.

Fig. 7. Single particle tracking, super-resolution imaging, and FRET offer a view of the relationship between receptor structure, dynamics and interactions.

(A–B) Single particle tracking of unliganded EGFR (A) and EGF:EGFR complex (B), and quantification of receptor interactions using HMM analysis. Shown are representative images from a 50 second trajectory (top images), including the overlayed raw data (pixelated green and magenta particles) and corresponding localizations (green and magenta dots). The distance between two distinguishable receptors plotted over time and subsequent HMM analysis (bottom plots). The three hidden states are shown as solid lines overlaid on the separation plot (red, free receptor; magenta, domain confined receptor; and blue, dimerized receptor). Note that receptor dimers in the absence of ligand are highly transient (A, bottom) whereas dimers in the presence of EGF are stable (B, bottom). (C) Two-color super-resolution reconstruction of EGFR imaged using Alexa647- and Cy3B-labeled receptors. The super-resolution reconstruction is shown as a Gaussian representation. Highlighted in white boxes are three potential individual receptor interactions, and these three regions are enlarged at right. Note the scale bar represents 25 nm. (D) Cross-correlation analysis between the two channels using individual localizations was used to generate two-dimensional radial distribution plots. The results show a near random distribution of receptors in the membrane in the absence of EGF (i.e. g(r) ~1 for all values of r). Addition of saturating EGF results in a sharp peak (i.e. g(r) > 1) at short distances, indicating organization in receptors at short length scales (< 50 nm), interpreted as receptor interactions induced by EGF ligand. The figure is adapted from Valley et al. (2015) [133], reproduced with the author’s permission.

Super-resolution imaging illuminates the nanometer-scale distribution and organization of membrane receptors in the plasma membrane. Acquisition of these sub-diffraction-limit resolution images can be achieved through a number of different methods (for review see refs. [149–152]). Localization-based super-resolution microscopy yields a set of coordinates that is ideally suited for quantification of molecular distribution in the plasma membrane [153,154]. Super-resolution imaging via direct stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (dSTORM) [155] demonstrated quantifiable changes in the distribution of EGFR in response to ligand [133]. A two-color dSTORM super-resolution reconstructed image shows the distribution of receptors, including distinct receptors separated by less than 25 nm (Fig. 7C) [133]. Localization-based cross-correlation analysis demonstrated that unliganded EGFR is nearly randomly distributed in the membrane (Fig. 7D, black line). Addition of saturating concentrations of EGF caused a high degree of correlation at short distances, less than 50 nm, consistent with receptor clustering (Fig. 7D, red line) [133], and possibly suggesting the formation of larger assemblies, as identified using other single molecule techniques [68].

In addition to showing the spatial distribution of signaling clusters in the membrane, super-resolution imaging can be combined with FRET to simultaneously show specific interactions within larger receptor clusters [156]. Moving forward, future experiments will likely combine these imaging methods with recent approaches in super-resolution microscopy to image membrane microdomains using spectral shifting membrane dyes [157]. Such experiments would provide tremendous utility in correlating membrane receptor signaling, including receptor interactions and clustering, with the specific local membrane environment.

Single molecule tracking experiments of TNFR have largely been used to demonstrate changes in receptor mobility. Heidbreder et al. demonstrated that the ensemble average mobility of TNFR1 in the presence of TNFα is indistinguishable from the resting receptor, however the distribution of mobilities of individual receptor molecules showed a small but significant shift toward faster moving receptors [137]. This shift in the distribution of receptor mobilities is accompanied by an overall decrease in the percentage of nearly-immobile receptors upon the addition of ligand, and the change is exacerbated when cells are pre-treated with MβCD [137]. This raises an interesting question: If membrane cholesterol facilitates interactions between TNFR TM helices, as described above [85], does this increase in TNFR1 mobility reflect a change in the oligomeric state of the receptor? Looking forward, single molecule tracking experiments should be performed to quantify the stoichiometry and kinetics of TNFR interactions.

Super-resolution imaging of TNFα-TNFR1 demonstrated a ligand-induced reorganization to higher order oligomers. Using super-resolution photoactivated localization microscopy (PALM), Fricke et al. simultaneously imaged TNFR1 and its ligand TNFα and quantified the size and localization density of ligand-receptor clusters [138]. It was shown that unliganded TNFR1 was dimeric, consistent with the crystal structure (Fig. 1C, left) [73], having a peak cluster size of ~20 nm, roughly the resolution of PALM. The ligand-bound TNFR1 displayed a shifted peak cluster size, indicating an increase in the size of an oligomeric assembly roughly 2-fold, furthermore these clusters contained a higher density of receptors per cluster. Rules-based modeling further confirmed these clusters as ligand-receptor trimers and receptor-mediated dimers, and parameter scanning converged to a model where TNFα-TNFR1 form clusters with ~3–6 receptor molecules. We and others previously suggested the formation of extensive ligand-receptor networks based on diffraction-limited imaging and crystallography [73,83,84, 158]. These results using super-resolution imaging and rules-based modeling suggest that clusters are likely comprised of a single dimer-of-trimers (i.e. two trimeric ligands coordinating up to six receptor protomers). The receptor-mediated dimer of TNFα-TNFR1 trimers may therefore represent the signaling cluster, with the joining receptor dimer being the minimal signaling unit within the cell (Fig. 5G). In retrospect, the formation of extensive ligand-receptor networks may be unlikely; the overall energy required to stabilize such extensive networks would likely not overcome the significant reduction in entropy associated with a hexagonal protein lattice in a fluid membrane bilayer.

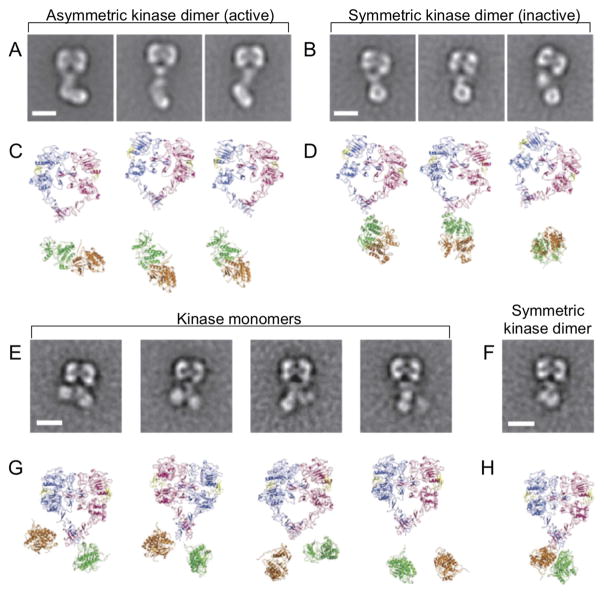

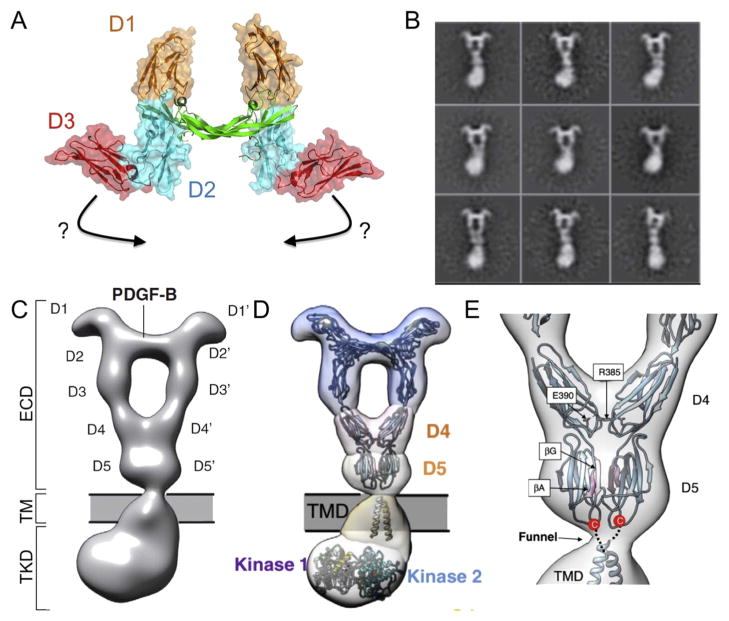

5.2. Putting the pieces together: Electron microscopy provides high resolution imaging of full-length receptors and a tool to link fragmented structures

Recent technical advances in EM now provide near-atomistic resolution structures of full-length membrane proteins and give a more complete picture of the complex structural link between extracellular, TM, and intracellular domains. Negative stain EM of EGFR provided the first simultaneous visualization of extracellular and intracellular domains [159]. Contrary to previous notions, these structures demonstrated that in a ligand-bound dimer a single ectodomain conformation allows for multiple kinase domain conformations (Fig. 8) [159]. Class averages showed both asymmetric (Fig. 8A) and symmetric kinase dimers (Fig. 8B), with the active asymmetric dimer the predominant kinase conformation. Crystal structures were fit to the resulting class averages using cross-correlation analysis (Fig. 8C,D) giving rise to a structural model of the nearly full-length EGFR. Introduction of mutations at the asymmetric kinase dimer interface resulted in a substantial change in the range of kinase structures. A single residue mutation at the asymmetric interface prevents the formation of asymmetric kinase dimers, and the resulting class averages illustrate the presence of kinase monomers (Fig. 8E) and symmetric kinase dimers (Fig. 8F). Interestingly, in all cases, the EGFR ectodomain remains unchanged, indicating a previously unpredicted degree of flexibility across the plasma membrane.

Fig. 8. Putting the pieces together: Simultaneous visualization of EGFR ectodomain and intracellular domain via negative-stain EM demonstrates that a single ectodomain conformation allows for multiple kinase domain conformations.