Abstract

Purpose

Despite the growing presence of social media in graduate medical education (GME), few studies have attempted to characterize their effect on residents and their training. The authors conducted a systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature to understand the effect of social media on resident (1) education, (2) recruitment, and (3) professionalism.

Method

The authors identified English-language peer-reviewed articles published through November 2015 using Medline, Embase, Cochrane, PubMed, Scopus, and ERIC. They extracted and synthesized data from articles that met inclusion criteria. They assessed study quality for quantitative and qualitative studies through, respectively, the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument and the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies.

Results

Twenty-nine studies met inclusion criteria. Thirteen (44.8%) pertained to residency education. Twitter, podcasts, and blogs were frequently used to engage learners and enhance education. YouTube and wikis were more commonly used to teach technical skills and promote self-efficacy. Six studies (20.7%) pertained to the recruitment process; these suggest that GME programs are transitioning information to social media to attract applicants. Ten studies (34.5%) pertained to resident professionalism. Most were exploratory, highlighting patient and resident privacy, particularly with respect to Facebook. Four of these studies surveyed residents about their social network behavior with respect to their patients, while the rest explored how program directors use it to monitor residents’ unprofessional online behavior.

Conclusions

The effect of social media platforms on residency education, recruitment, and professionalism is mixed and the quality of existing studies is modest at best.

Social media, which consists of Web-based technologies that facilitate idea sharing through collaboration, interaction, and discussion, have increasingly been incorporated into health care and medical education.1 Little is known about the use of social media in graduate medical education (GME).

The millennial generation of residents is unique in both the learning environment in which they train and the ways in which they learn.2 Thanks, at least in part, to the Internet, they are tasked with digesting vast amounts of ever-increasing information while still caring for individuals with complex medical conditions. Duty hours limit the time they are permitted to be in the hospital, leaving fewer opportunities for traditional classroom and ward-based learning. Social media platforms, which offer ways to address these challenges, are progressively being introduced into GME.

Social media platforms have the potential to influence several domains of GME. Platforms, including wikis (i.e., Websites offering collaborative modification of content), social networking sites (e.g., Facebook), microblogs (i.e., Twitter), and blogs—to name just a few—offer a venue through which trainees communicate, exchange ideas, learn evidence-based medicine, and promote their scholarship.3,4 Beyond providing educational content, social media are being used by residency programs to establish an online presence and recruit potential applicants.5 Residents are less frequently turning to mailings and the backs of journals to search for jobs; rather, many are using social media sites to obtain information on possible postgraduate opportunities. In addition to its effect on scholarship and recruitment, the use of social media—due to the public nature of platforms6,7—has also brought forth issues related to online professionalism in GME, and the potential for dissemination of protected health information.

Despite the incorporation and use of social media in GME, no study has sought to understand if the use of these Web-based technologies influences residents during their training—and if so, how. In recent years, a few studies have attempted to characterize the effect of social media platforms on medical education at large. A systematic review by Cheston and colleagues (2013) examined the effect of social media on medical education, specifically knowledge and skill attainment.1 The authors of the study, however, defined medical education, as all levels of physician training.1 Two other studies examined the impact of social media on online professionalism. Again, however, they focused on the medical community at large.8,9 While these studies do capture the opinions and attitudes of some resident physicians, they did not concentrate on GME trainees. Although informative, these reviews focused on only one area in which social media have had an effect, leaving other domains unexamined.

Here, we aim to fill this gap by conducting a systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature in order to examine the effect of social media platforms on residency education, recruitment, and professionalism. In doing so, we hope to shed light on the use of social media in GME.

Method

We conducted a systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature to explore the use of social media platforms in GME. We sought to understand how social media platforms effect (1) resident education and learning, (2) resident recruitment, and (3) resident professionalism.

Search strategy

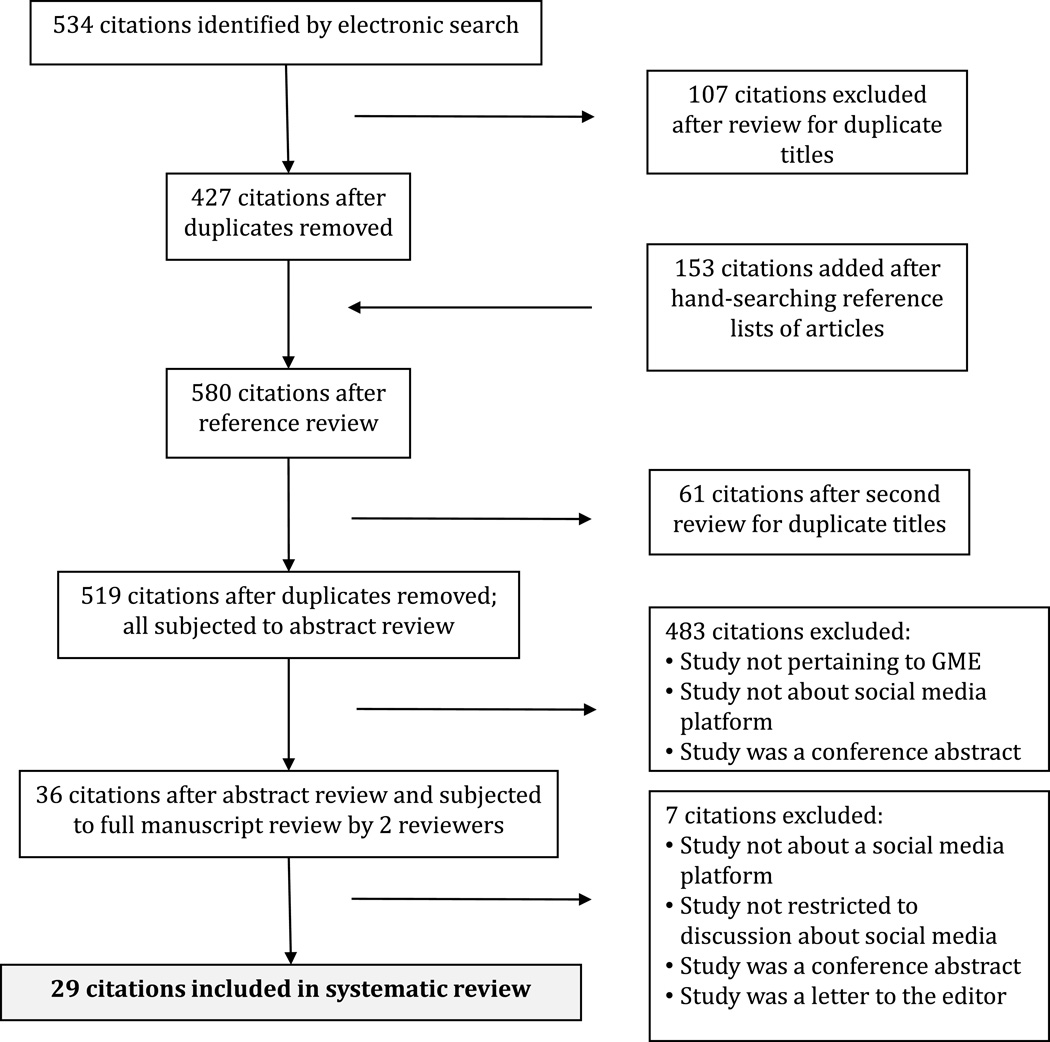

Figure 1 shows the selection and review process for this systematic review. In consultation with a health sciences librarian (D.W.), we performed comprehensive searches of Medline, Embase, and Cochrane, between October and November of 2015. Major search terms for all databases included social media, graduate medical education, and residency (List 1). We conducted reference and related article searches in Scopus, PubMed, and ERIC. To identify additional manuscripts, we hand searched the bibliographies of included manuscripts.

Figure 1.

The selection and review process for a 2015 systematic review of the Evidence-Based Literature Examining the Influence of Social Media on Resident Education, Resident Recruitment, and Resident Professionalism.

List 1.

Search Terms Used in 2015 Search of the Evidence-Based Literature Examining the Influence of Social Media on Resident Education, Resident Recruitment, and Resident Professionalism

| Social Media |

| Social Media/ |

| social adj2 media |

| social adj2 network* |

| blog* |

| Tumblr |

| wiki* |

| podc* |

| Graduate Medical Education |

| Education, Medical, Graduate/ |

| Schools, Medical/ |

| grad* adj2 med* adj2 education |

| med* adj2 school |

| Residency |

| "Internship and Residency"/ |

| residen* |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included any English-language articles published through November 2015 that pertained to social media platforms including blogs, microblogs (e.g., Twitter), social networking sites (e.g., Facebook, Yammer), podcasts, video-sharing sites (YouTube), and wiki platforms. We included studies that pertained to residents in any year of training and from any specialty. We did not limit studies to those conducted to the United States. To focus this review on social media platforms, we excluded online and electronic resources that were not interactive (e.g., e-learning modules). We also excluded conference abstracts and letters to the editor. We included only full-text articles in the review, and we identified and excluded duplicates. Two reviewers (M.S. and P.L.) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of the retrieved articles. With a third (T.F.B.), they selected items for full text review (see also Results / Study selection).

Data extraction

Two of us (M.S. and P.L.) performed data extraction for each study independently, and a third author (T.F.B.) resolved differences. We extracted the following variables from each study: study authors, year of publication, study design, setting, population studied, control population, social medial platform used, research approach, intervention, key outcomes, and study quality.

Quality assessment

For quantitative studies, we used the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI),10 a validated instrument that assesses the quality of medical education research. This 10-item scale assesses the methodological quality of studies in 6 domains: study design, sampling, type of data, validation of evaluation instrument, data analysis, and outcomes measured. Two of us (M.S and P.L) separately assigned points to each study, such that 6 represented the lowest quality and 18, the highest (See supplemental digital Table 1). Using this tool, we created a standardized form to extract the data from included studies.

For qualitative studies, we used the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ), a checklist that consists of 32 criteria, developed to promote explicit and comprehensive reporting of interviews and focus groups. The checklist is divided in 3 domains; research team and reflexivity, study design, and analyses and findings. Two of us (P.L. and M.S.) separately assessed the presence or absence of each of the 32 items on the COREQ checklist (See supplemental digital Table 2).

We reconciled scoring differences for both the MERSQI and COREQ instruments through discussion.

Results

Study selection

Our initial search yielded 534 English language titles, of which, we excluded 107 as duplicates, leaving 427 remaining in our initial search. Next, we hand searched forward citations, which yielded 153 new titles, of which we excluded 61 duplicates. After combining and deleting duplicates, we were thus left with a total of 519 articles. Initially, two of us (M.S. and P.L) disagreed about the inclusion of 5 additional studies (kappa = 0.86); we resolved these conflicts through discussion with a third reviewer (T.F.B.). We excluded two additional studies upon full-text review based on initial exclusion criteria. Ultimately, we included 29 studies11–39 in our analysis (Figure 1).

Tables 1–3 presents the characteristics of the studies including the following: study design, setting, participants, social media platform, intervention, outcomes, and the MERSQI and COREQ scores (as applicable). The mean MERSQI score was 9.57 and ranged from 7.5 to 14.5 (Tables 1–3). The number of items reported on the COREQ checklist ranged from 21 to 29 (out of 32 items). Supplemental Digital Table 1 provides the MERSQI score components for each of the 22 quantitative studies11–15,17–20,23–33,36,38, and Supplemental Digital Table 2 provides the COREQ checklist for components of the 7 qualitative studies.16,21,22,34,35,37,39

Table 1.

Summary of Evidence Regarding the Influence of Social Media on Resident Education, Based on a 2015 Literature Reviewa

| Author, Year | Study details | Intervention | Results | MERSQI scoreb | COREQ scorec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bergl, 201511 |

|

2 chief residents and 1 APD tweeting about resident education and academic activities |

|

9.5 | N/A |

| Bensalem-Owen, 201112 |

|

Podcasts for resident EEG instruction |

|

13 | N/A |

| Bogoch, 201213 |

|

Blog of morning report session generated/ uploaded after each session with detailed discussion on clinical topics, and links to journal articles and medical images |

|

10 | N/A |

| Desai, 201414 |

|

Analysis of tweets at the conference |

|

14 | N/A |

| Fischer, 201315 |

|

2 reviewer team (1 internal medicine resident and 1 rheumatologist) in Switzerland |

|

12 | N/A |

| Jalali, 201516 |

|

Description of tweets at this annual medical education conference; 2 reviewers qualitatively coded each tweet into cognitive themes |

|

N/A | 21 |

| Karimkhani, 201517 |

|

Dermatology wiki with educational materials for medical students and dermatology residents |

|

7.5 | N/A |

| Kohli, 201118 |

|

Radiology wiki for radiology residents with educational content and logistic information regarding the program |

|

8 | N/A |

| Langenau, 201419 |

|

Web-based objective structured clinical examination with remote standardized patients through Skype |

|

9 | N/A |

| Matava, 201320 |

|

Survey about podcast use and preferences |

|

9 | N/A |

| Shaughnessy, 201321 |

|

Residents were asked to participate in 1 of 2 focus groups to share their experiences with reflective exercises; investigators used open coding to analyze the focus group transcripts and to identify themes |

Four main themes noted: (1) Blogging (reflecting) as a method of enhanced personal and professional self- development; (2) An inherent conflict between self- development and professional duties; (3) Writing about emotional issues is difficult for some residents; and (4) Clinical blogging has not reached its potential due to the way it was introduced (lack of structure) |

N/A | 29 |

| Sherbino, 201522 |

|

A discussion forum across multiple social media platforms, engaging authors, content experts, and the health professions education community, then a 2-week post-blog time period for analysis of engagement |

|

N/A | 28 |

| Vasilopoulos, 201523 |

|

|

|

14.5 | N/A |

Abbreviations: APD indicates Associate Program Director; N/A, not applicable; and EEG, electroencephalogram.

Two authors (P.L. and M.S.) scored each article independently using the MERSQI and COREQ instruments, as appropriate. They reconciled any differences through discussion.

The MERSQI or Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument is a validated instrument which assesses the quality of quantitative medical education research. Scores may range from 6 to 18; higher scores represent higher quality.

The COREQ or Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ) is a checklist that consists of 32 criteria, developed to promote explicit and comprehensive reporting of qualitative studies. Scores may range from 0 to 32; higher scores represent higher quality.

The aforementioned tools embeds tracking codes on to webpages in efforts to measure frequency of site visits and viewer demographics

Table 3.

Summary of Evidence Regarding the Influence of Social Media on Resident Professionalism, Based on a 2015 Literature Reviewa

| Author, Year | Study details | Intervention | Results | MERSQIb | COREQc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ben-Yakov, 201530 |

|

Survey to explore attitudes about searching the Web for patient information |

|

10 | N/A |

| Cook, 201331 |

|

Survey about ethics and professionalism practices |

|

8.5 | N/A |

| Ginory, 201232 |

|

Survey regarding Facebook use |

|

9 | N/A |

| Jent, 201133 |

|

Survey about social media use and thoughts regarding seven fictional social media profiles |

|

8 | N/A |

| Landman, 201034 |

|

Evaluation of online profiles of general surgery residents and faculty members |

|

N/A | 26 |

| Langenfeld, 201435 |

|

Reviewed Facebook profiles to assess whether they were in alignment with professionalism guidelines |

|

N/A | 23 |

| Moubarak, 201136 |

|

Survey about Facebook and its impact on the doctor-patient relationship |

|

8.5 | N/A |

| Ponce, 201337 |

|

Reviewed Facebook profiles and rated them based on professionalism |

|

N/A | 25 |

| Schulman, 201338 |

|

Survey to assess familiarity with, usage of, and attitudes towards social media Websites of admissions offices at U.S. medical schools and residency programs |

|

8 | N/A |

| Thompson, 201139 |

|

Reviewed Facebook profiles to assess for possible privacy violations and adherence to professional norms |

|

N/A | 22 |

Abbreviations: ED indicates emergency department; AMA, American Medical Association; HIPAA, Health Insurance Portability and Accountabilit Act.

Two authors (P.L. and M.S.) scored each article independently for both the MERSQI and COREQ instruments. They reconciled any differences through discussion.

The MERSQI or Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrumentis a validated instrument which assesses the quality of quantitative medical education research. Scores may range from 6 to 18; higher scores represent higher quality.

The COREQ or Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ) is a checklist that consists of 32 criteria, developed to promote explicit and comprehensive reporting of qualitative studies. Scores may range from 0 to 32; higher scores represent higher quality.

All of the studies were published in 2010 or later. Most studies (n = 22, 75.8%) were descriptive14–16,18,20,22,24–39 (cross-sectional, survey designs, or case studies). The remaining seven (24.1%) articles evaluated an intervention with pre and post measures.11–13,17,19,21,23 We uncovered no randomized control trials (RCTs). Among the platforms studied, Facebook25,28,30–32,34–37,39 (n = 8, 27.6%), blogs13,21,22 (n = 3, 10.3%), Twitter11,14,16 (n = 3, 10.3%), and podcasts12,20,23 (n = 3, 10.3%) were the four most common. While the focus of each study pertained to residents, 9 studies13,17,23,25,28–30,33,39 (31.0%) included medical students and 9 studies14,24,26,27,30,31,33,34,38 (31.0%) included faculty members and program directors (PDs). Among the GME residencies, studies on social media most frequently focused on residents of general/sub-specialty surgery27,28,34,35,37 (n = 5, 17.2%), internal medicine11,13,14 (n = 3,10.3%) and anesthesia12,20,23 (n = 3,10.3%); radiology, emergency medicine, pediatrics, family medicine, and dermatology residents were studied, albeit less frequently with respect to social media.

Resident education and knowledge

Of the 29 studies, 1311–23 (44.8%) attempted to use social media to enhance the educational value that residents receive (Table 1). Of these, Twitter11,14,16 (n = 3, 23.1%), podcasts12,20,23 (n = 3, 23.1%), and blogs13,21,22 (n = 3, 23.1%) were the most frequently used platforms. Wikis17,18 (n = 2, 15.4%), Skype19 (n = 1, 7.7%), and YouTube15 (n = 1, 7.7%) were studied less frequently. The average MERSQI score for studies pertaining to residency education was 10.65; the range was 7.5 to 14.5.

Within the domain of education, social media platforms, particularly Twitter and blogs, have been used to promote clinical concepts, disseminate evidence-based medicine, and circulate conference material to residents. We found that blogs13 were used both to complement case-based teaching during morning report and as a vehicle to support online journal clubs22 through which residents, authors, and other members of the health community could discuss research content. Bergl and colleagues surveyed internal medicine residents regarding their attitudes towards a 1-year chief-run Twitter feed.11 Residents generally found the chief residents’ tweets informative, and 69% of 61 residents agreed that Twitter enhanced their overall education in residency. Residents reported that Tweets about ‘pearls’ from morning report, medical news, grand rounds, and EBM were most informative to their learning.11

In addition to serving as an adjunct to traditional residency learning, Twitter is being adapted at medical conferences that residents attend.14,16 A high-quality (MERSQI of 14) case study by Desai and colleagues sought to determine the reach of Tweets from participants at the 2013 Association of Program Directors in Internal Medicine meeting in 2013,14 whose attendance included a mixture of internal medicine faculty members, PDs, and residents. The authors found that most Tweets were from faculty rather than from residents and that faculty members more frequently had their messages retweeted, compared to those of residents. However, predicting the influence that Tweets had on resident learners at the conference was difficult, and the investigators could not gauge how amplified tweets (i.e., tweets retweeted by conference attendees) affect learners after the conference since they did not measure such outcomes.

Several studies examined the effects of podcasts and Wiki platforms on resident knowledge and skills. One of the first studies to examine the effects of podcasts on residency education was a small (n = 10), intervention-based pilot from the University of Kentucky.12 Bensalem-Owen and colleagues studied the effect of electroencephalogram (EEG) podcasts on resident knowledge outcomes. Ultimately, they found no significant difference in mean test scores compared to conventional lectures on EEG interpretations.12 A few years later, a high quality study (MERSQI = 14.5) by Vasilopoulos and colleagues tested the effect of an EEG podcast on residents’ comfort using the technology as well as on resident knowledge acquisition, which the investigators measured with test scores.23 In this small study population (n = 21), EEG interpretation scores improved after viewing the podcasts, and 100% of the residents found the experience either positive or neutral. A cross-sectional study by Matava and colleagues, in which the authors surveyed 169 Canadian anesthesia residents, also aimed to assess the impact of podcasts on education.20 The authors found that 60% had used medical podcasts in the past, and 72.3% of these users found podcasts valuable because they afforded residents the "ability to review material whenever" they wanted.

Although Wikis are familiar to most residents, their use and effect on resident education appear to be minimal. Kohli and colleagues conducted a case study at the University of Indiana to evaluate radiology residents’ comfort with, access to, and use of an internal Wiki site.18 They found that 78% of 51 residents knew how to edit pages, and only 12% using it for educational content. A University of Colorado study by Karimkhani and colleagues of medical students and residents found that a Wiki about dermatology was highly rated among medical students, but less so among residents who favored patient-based exposure to cases and skin findings, rather than online content.17

YouTube, known for its online video-sharing capability, appears to be another social media platform being used to promote scholarship in GME. A study conducted by Fischer and colleagues evaluated the educational value and accuracy of arthrocentesis videos published by health institutions from 2008–2012.15 Of the 13 videos reviewed, the majority (n = 8, 61.5%) were considered to be of moderate quality by two reviewers (one internal medicine resident and one rheumatologist) and eight (61.5%) were considered useful with respect to resident education. Although nearly half (n = 6, 46.1%) demonstrated sterile techniques, only 1 video (7.7%) was rated to be of excellent quality. Overall, five of the videos (38.5%) were classified as educationally unhelpful.

Resident recruitment

Of the studies, 6 (20.7%) explored how social media platforms are being used to address residency recruitment24–29 (Table 2). The majority of the studies24–27,29 (n = 5, 83.3%) used surveys to ascertain the attitudes of trainees or PDs towards social media as either (1) a mechanism for residency programs to enhance their online visibility or (2) a means of screening residency applicants. The average MERSQI score for resident recruitment studies was 8.66 with range of 7.5 to 10.

Table 2.

Summary of Evidence Regarding the Influence of Social Media on Resident Recruitment, Based on a 2015 Literature Review

| Author, Year | Study details | Intervention | Results | MERSQIa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deloney, 201224 |

|

Survey about electronic social media site use |

|

8 |

| George, 201425 |

|

Survey about medical student opinions on the use of Facebook profile screening by residency admission committees |

|

9 |

| Go, 201226 |

|

Survey about social networking and selection of residency candidates |

|

9 |

| Go, 201227 |

|

Survey about attitudes on using social media in application review |

|

7.5 |

| Golden, 201228 |

|

Reviewed publically searchable Facebook profiles of ENT applicants and scored each profile on professionalism based on content available |

|

8.5 |

| Schweitzer, 201229 |

|

Web-based survey to evaluate use of social media among osteopathic trainees |

|

10 |

Abbreviations: APDR indicates Association of Program Directors in Radiology; AAMC, Association of American Medical Colleges; ACGME, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; PD, program director; USIMG, United States international medical graduate; and ENT, ear nose and throat.

All of the articles about social media and resident recruitment were quantitative. Two authors (P.L. and M.S.) scored each article independently using the MERSQI instrument. They reconciled any differences through discussion. Since all of the articles about social media and resident recruitment were quantitative in measure. The MERSQI or Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument is a validated instrument which assesses the quality of quantitative medical education research. Scores may range from 6 to 18; higher scores represent higher quality.

Across GME, programs are acknowledging the presence of social media platforms and appear to be integrating them into aspects of their training programs. In one study of radiology PDs,24 38% of 132 associate PDs report social media use and roughly a quarter felt that program Facebook pages would be of value. Similarly, a cross-sectional survey study by Schweitzer and colleagues of osteopathic applicants, interns, and residents found that a majority of applicants and residents are using social media sites for application information and post-graduate job searches.29 Commonly used platforms include Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, and Student Doctor Network blogs.

In addition to offering information about programs or jobs, several studies demonstrated the extent to which social media are being used by GME PDs to screen applicants during the selection process.26–28 In a study in the Journal of Surgical Education, Go and colleagues surveyed 250 PDs of general surgery and surgery sub-specialty residency programs on their use of social media sites (Facebook, Twitter, MySpace, etc) to screen applicants.27 They reported that 17% visit social media sites to gain info about applicants, and that upon doing so, 33.3% of those PDs ranked applicants lower after a review of their social media profile/s. Similarly, another study by Go and colleagues in Medical Education surveyed Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) PDs on their use of social media platforms during the intern selection process.26 They found that 16.3% of 196 PDs had reviewed Internet resources to learn more about a candidate’s application. In this study, a high proportion (38.1%) of PDs ranked applicants lower as a result of their social media profile/s. Of the platforms used, the majority of PDs used Facebook to screen applicants. A case series by Golden and colleagues of ear, nose, and throat (ENT) residency applicants at University of Alabama at Birmingham found that of 112 profiles searched, 11% of ENT applicants had questionable content (e.g., alcohol intoxication and wearing Halloween costumes portraying specific negative ethnic stereotypes); however, the content did not affect the applicants' match outcomes.28

Resident professionalism

Ten studies30–39 (34.5%) explored the effects of social media on professionalism in residency (Table 3). Most of these studies were exploratory in nature and highlighted issues of patient and resident privacy, particularly with respect to Facebook. The average MERSQI score for studies on resident professionalism was 8.67, and the range was 8.0 –10.0.

Four of these studies (40%)30–32,36 surveyed residents about their social network behavior with respect to their patients (searching for patients or accepting friend requests). A study by Ginory and colleagues surveyed 182 psychiatry residents through the American Psychiatric Association about their social media (Facebook) usage in the context of clinical care.32 Of those surveyed, 18.7% reported looking up patient profiles on Facebook and 9.7% reported having received a friend request from a current patient; none of the residents accepted these requests. In addition, the majority of residents reported not having guidance regarding social media use during clinical training and that more guidance would be welcome. A case series by Jent and colleages in the Journal of Adolescent Health explored the attitudes of pediatric residents (n = 80) and pediatric faculty members (n = 29) toward social media usage in general and toward seven specific fictional social media profiles.33 They found that more trainees used social media compared with faculty, but that both groups generally believed it was not an invasion of privacy to look at social media profiles of colleagues and patients. Only trainees, however, reported conducting social media site searches of patients.

In addition, six studies explored the use of social network sites by residency programs as a vehicle for identifying and censoring unprofessional behavior of trainees.33–35,37–39 A study by Langenfeld and colleagues in the Journal of Surgical Education searched Facebook profiles of 319 general surgery residents for unprofessional behavior.35 The study, which was of higher quality (MERSQI 10), found that 73.7% of residents had profiles with no unprofessional content; 14.1% had profiles with potentially unprofessional content (drinking alcoholic beverages); and 12.2% of residents had profiles with clearly unprofessional content (e.g., Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act violations, binge drinking, and sexually suggestive material). Another study by Ponce and colleagues assessed the effect of unprofessional online content on residency match outcomes.37 They reviewed the Facebook profiles of 153 orthopedic surgery applicants to the University of Alabama at Birmingham and rated profiles on a subjective professionalism scale of one to three, where 3 = “no professionalism issues,” 2 = “questionable content,” and 1 = “definite violations of professionalism.” They were guided by ACGME’s “Components of Professionalism.”40 They found that applicants had a mean professionalism score of 2.82 and that 16% of applicants had at least some unprofessional content on their Facebook profile. The authors reported no significant difference in professional scores among those who matched compared to those who did not. In their research, Landman and colleagues took surveying for unprofessional social media content one step further.34 In addition to analyzing the use of Facebook among general surgery residents and faculty members, they also discussed the formulation of and proposed individual and department-wide guidelines for social media usage at Vanderbilt University.34

Discussion

We conducted this systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature to examine the use of social media platforms in GME. Of the 29 studies we reviewed, most (n = 13; 44.8%) studied the effect of a particular social media platform on residency education. Within the context of resident education, we found Twitter, podcasts, and blogs to be the most frequently used platforms. Across studies, these platforms were used to share clinical teaching points, disseminate evidence-based medicine, and circulate conference materials to residents. At medical conferences, Twitter was the most frequently used platform to promote conference themes (via hashtags) and research content to attendees of whom some were residents. The majority of studies, however, were exploratory and used hashtags to analyze the frequency with which conference attendees accessed the platform, not its effect on learning. Studies that examined the effects of wikis and podcasts on resident education found that residents are most often using the platforms as a mechanism to review material on their own, at any point in time. For residents, one advantage of podcasts and wikis seems to be their comfort with these platforms. In several studies, trainees reported prior exposure to these platforms, and we wonder if perhaps this familiarity aided in reducing program-wide start-up costs when programs adopted them to promote learning or improve skillsets. However, comfort with a particular platform does not appear to always translate into frequent, sustained use or increased knowledge.

In general, most studies which pertained to social media and education were of modest quality and offered mixed results in terms of resident satisfaction and knowledge attainment. Additionally, six of the thirteen studies that pertained to residency education had a mixed sample population that contained input from residents as well as faculty members and medical students. Thus to assess the true effect of social media platforms on residency education is difficult—and generalizing these findings is even more difficult.

The majority of the studies assessing residency recruitment sought to examine the attitudes of trainees or PDs toward social media platforms, particularly through institutional-specific surveys. In addition, the authors of several studies interviewed PDs regarding the degree to which they screen applicants on the content of their social media platforms, such as Facebook. Results seemed to vary minimally across GME programs (e.g., medicine vs. surgery). Among the 10 studies that focused on resident professionalism, the majority used Facebook and explored the extent to which residents posted or disseminated information on this platform. A few of these studies raised concerns about privacy, but only one offered an attempt at providing guidelines. Overall, the studies focusing on residency recruitment and professionalism were of poor quality, and half were generated from single institution-based surveys focusing on just one type of social media platform.

Whereas previous reviews have explored the use of social media in the health care environment and on undergraduate medical education, few have done so with respect to GME. Residents are a unique population of physicians, with a different set of needs and goals than their undergraduate counterparts and members of the medical community at large. As such, examining the literature that pertains to the use of social media platforms in GME is an important first step in understanding the effect of this relatively new phenomenon.

In doing so, we highlight a few notable themes. First, residents and residency programs across specialties are increasingly using social media. Today’s residents train in a complex learning environment characterized by a high volume of information and fast-paced delivery. Further, because of duty hours, residents have less time for formal, classroom-based learning. For this generation of millennial trainees, who are both comfortable and versatile with technology, the incorporation of social media into GME appears logical. Second, we found that despite many conference abstracts and editorials calling for research about social media and residency, few studies have attempted to formally study the adoption and/or use of social media in GME. Of those that have, few have used rigorous methods. Third, of the studies we reviewed, most offer mixed results and provide medical educators and residents with little guidance on how best to incorporate social media platforms into the residency experience. Finally, within the three domains we examined (education, recruitment, and professionalism), study design and outcomes varied tremendously.

Our study is not without limitations. Given the relatively recent emergence of social media and the rapid rate in which platforms develop, we have possibly missed studies published since our search that pertain to GME. Moreover, despite our efforts to include all relevant search terms, we may have unintentionally excluded keywords and thus relevant studies. An additional limitation is that much of the relevant works that emerged from our initial search were ultimately excluded because they were not peer-reviewed but rather they constituted conference abstracts. Finally, our intent was to capture the effect of social media platforms on GME, with a focus on residents. Some of the studies included—even though they pertained directly to GME—captured the attitudes of PDs, not residents. Additionally, a small percentage of the studies included some medical students in their study population.

In spite of these limitations, our systematic review adds to the current understanding of social media use in GME. Although interest in social media across GME seems to be wide and growing, its effect on education, recruitment, and professionalism remains inconclusive and understudied. Of the peer-reviewed studies we analyzed, most are descriptive in nature, highlighting resident attitudes toward social media in these three domains. Of the few studies that did include an intervention, the sample sizes were small and often lacked controls. Moreover, the results realized few tangible benefits for trainees—either in knowledge gains or in satisfaction scores. Among the studies that pertained to recruitment and professionalism, most were cross-sectional in design and used online surveys to capture resident attitudes towards platform-based content. Apart from the identification of trends, these studies do not allow for any associations or causal inferences.

Despite increasing use of these technologies by residents and medical educators, the adoption of social media into GME remains in its early stages. Further high-quality research is necessary such that the effectiveness of the platforms can be measured with validated instruments. In addition to moving towards intervention-based studies, researchers ought to be consistent in the outcomes they use so that results across studies can be compared. Given that this is a relatively new area of research, a qualitative approach offers value, particularly with hypothesis generation. However, among the qualitative studies included here16,21,22,34,35,37,39, only two 21,22 of the seven used focus groups or one–on-one interviews. Additionally, only one study conveyed their findings to the participants in which they studied. Future studies might follow the lead of Sherbino and colleagues22 and re-engage the GME community such that findings can shape attitudes and practice.

Beyond improvements in methodology, future studies might also focus on pragmatism. What might be most useful to residents is if study findings offered practical instruction on how they should incorporate social media platforms into their resident experience in real-time. Overall, further research is needed such that a best practice approach can be developed for trainees and program leaders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Dr. Madeline Sterling is supported by T32HS000066 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Bishop is supported by a National Institute On Aging Career Development Award (K23AG043499) and by funds provided as Nanette Laitman Clinical Scholar in Public Health at Weill Cornell Medical College.

Footnotes

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: Reported as not applicable.

Disclaimers: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the National Institutes of Health.

Previous presentations: The content in this paper was presented at the national Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) meeting in Hollywood, Florida on May 11th in the Scientific poster session.

Contributor Information

Madeline Sterling, Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York.

Peggy Leung, Department of Medicine, New York Presbyterian Hospital – Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York.

Drew Wright, Samuel J. Wood Library & C. V. Starr Biomedical Information Center, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York.

Tara F. Bishop, Division of Healthcare Policy and Economics, Department of Healthcare Policy and Research, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York.

References

- 1.Cheston CC, Flickinger TE, Chisolm MS. Social media use in medical education: A systematic review. Academic Medicine. 2013;88:893–901. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828ffc23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wutoh R, Boren SA, Balas EA. eLearning: A review of Internet-based continuing medical education. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. 2004;24:20–30. doi: 10.1002/chp.1340240105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGowan BS, Wasko M, Vartabedian BS, Miller RS, Freiherr DD, Abdolrasulnia M. Understanding the factors that influence the adoption and meaningful use of social media by physicians to share medical information. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e117. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choo EK, Ranney ML, Chan TM, et al. Twitter as a tool for communication and knowledge exchange in academic medicine: A guide for skeptics and novices. Med Teach. 2015;37:411–416. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.993371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schlitzkus LL, Schenarts KD, Schenarts PJ. Is your residency program ready for Generation Y? J Surg Educ. 2010;67:108–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chretien KC, Farnan JM, Greysen SR, Kind T. To friend or not to friend? Social networking and faculty perceptions of online professionalism. Academic Medicine. 2011;86:1545–1550. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182356128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chretien K, Kind T, Goldman E, Beckman L. It's your own risk: Medical students' views on online posting. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25:S321. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gholami-Kordkheili F, Wild V, Strech D. The impact of social media on medical professionalism: A systematic qualitative review of challenges and opportunities. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e184. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chretien KC, Tuck MG. Online professionalism: A synthetic review. International review of psychiatry. 2015;27:106–117. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1004305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cook DA, Reed DA. Appraising the quality of medical education research methods: The Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale-Education. Academic Medicine. 2015;90:1067–1076. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergl PA, Narang A, Arora VM. Maintaining a Twitter feed to advance an internal medicine residency program’s educational mission. JMIR Medical Education. 2015;1:e5. doi: 10.2196/mededu.4434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bensalem-Owen M, Chau DF, Sardam SC, Fahy BG. Education research: Evaluating the use of podcasting for residents during EEG instruction A pilot study. Neurology. 2011;77:e42–e44. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31822b0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bogoch II, Frost DW, Bridge S, et al. Morning Report Blog: A Web-Based Tool to Enhance Case-Based Learning. Teaching and Learning in Medicine. 2012;24:238–241. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2012.692273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desai T, Patwardhan M, Coore H. Factors that contribute to social media influence within an Internal Medicine Twitter learning community. F1000Research. 2014;3(4283.1) doi: 10.12688/f1000research.4283.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer J, Geurts J, Valderrabano V, Hugle T. Educational quality of YouTube videos on knee arthrocentesis. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology. 2013;19:373–376. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e3182a69fb2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jalali A, Sherbino J, Frank J, Sutherland S. Social media and medical education: Exploring the potential of Twitter as a learning tool. International Review of Psychiatry. 2015;27:140–146. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1015502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karimkhani C, Boyers LN, Ellis LZ, et al. Impact of a dermatology wiki website on dermatology education. Dermatology Online Journal. 2015;21(1) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohli M, Bradshaw J. What is a wiki, and how can it be used in resident education? Journal of Digital Imaging. 2011;24:170–175. doi: 10.1007/s10278-010-9292-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langenau E, Kachur E, Horber D. Web-based objective structured clinical examination with remote standardized patients and Skype: Resident experience. Patient Education and Counseling. 2014;96:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matava CT, Rosen D, Siu E, Bould DM. eLearning among Canadian anesthesia residents: A survey of podcast use and content needs. BMC medical education. 2013;13:59. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaughnessy AF, Duggan AP. Family medicine residents' reactions to introducing a reflective exercise into training. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2013;26:141–146. doi: 10.4103/1357-6283.125987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sherbino J, Joshi N, Lin M. JGME-ALiEM Hot Topics in Medical Education Online Journal Club: An analysis of a virtual discussion about resident teachers. Journal of Graduate Medical Education. 2015;7:437–444. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-15-00071.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vasilopoulos T, Chau DF, Bensalem-Owen M, Cibula JE, Fahy BG. Prior podcast experience moderates improvement in electroencephalography evaluation after educational podcast module. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2015;121:791–797. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deloney LA, Rozenshtein A, Deitte LA, Mullins ME, Robbin MR. What program directors think: Results of the 2011 Annual Survey of the Association of Program Directors in Radiology. Academic Radiology. 2012;19:1583–1588. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.George DR, Green MJ, Navarro AM, Stazyk KK, Clark MA. Medical student views on the use of Facebook profile screening by residency admissions committees. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:251–253. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2013-132336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Go PH, Klaassen Z, Chamberlain RS. Residency selection: Do the perceptions of US programme directors and applicants match? Medical Education. 2012;46:491–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Go PH, Klaassen Z, Chamberlain RS. Attitudes and practices of surgery residency program directors toward the use of social networking profiles to select residency candidates: A nationwide survey analysis. J Surg Educ. 2012;69:292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Golden JB, Sweeny L, Bush B, Carroll WR. Social networking and professionalism in otolaryngology residency applicants. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:1493–1496. doi: 10.1002/lary.23388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schweitzer J, Hannan A, Coren J. The role of social networking web sites in influencing residency decisions. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2012;112:673–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ben-Yakov M, Kayssi A, Bernardo JD, Hicks CM, Devon K. Do emergency physicians and medical students find it unethical to 'Look up' their patients on Facebook or Google? Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2015;16:234–239. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2015.1.24258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cook AF, Sobotka SA, Ross LF. Teaching and assessment of ethics and professionalism: A survey of pediatric program directors. Academic Pediatrics. 2013;13:570–576. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ginory A, Sabatier LM, Eth S. Addressing therapeutic boundaries in social networking. Psychiatry. 2012;75:40–48. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2012.75.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jent JF, Eaton CK, Merrick MT, et al. The decision to access patient information from a social media site: What would you do? The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;49:414–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Landman MP, Shelton J, Kauffmann RM, Dattilo JB. Guidelines for maintaining a professional compass in the era of social networking. J Surg Educ. 2010;67:381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Langenfeld SJ, Cook G, Sudbeck C, Luers T, Schenarts PJ. An assessment of unprofessional behavior among surgical residents on Facebook: A warning of the dangers of social media. J Surg Educ. 2014;71:e28–e32. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moubarak G, Guiot A, Benhamou Y, Benhamou A, Hariri S. Facebook activity of residents and fellows and its impact on the doctor-patient relationship. Journal of Medical Ethics. 2011;37:101–104. doi: 10.1136/jme.2010.036293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ponce BA, Determann JR, Boohaker HA, Sheppard E, McGwin G, Jr, Theiss S. Social networking profiles and professionalism issues in residency applicants: An original study-cohort study. J Surg Educ. 2013;70:502–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schulman CI, Kuchkarian FM, Withum KF, Boecker FS, Graygo JM. Influence of social networking websites on medical school and residency selection process. Postgrad Med J. 2013;89(1049):126–130. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thompson LA, Black E, Duff WP, Paradise Black N, Saliba H, Dawson K. Protected health information on social networking sites: Ethical and legal considerations. Journal of medical Internet research. 2011;13:e8. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ludwig S, Day S. Accrediation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME; 2011. [Accessed January 10, 2017]. Chapter 7: New Statndards for RSident Professionalims: Descussion and JustificationAccreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/jgme-11-00-47-51[1].pdf. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.