To the Editor

The C57BL/6 mouse inbred strain is the preferred strain for generating various knockout, knock-in, and genetic glomerular disease models. A review of published literature in nephrology journals reveals that C57BL/6 and C57BL/6J have been used interchangeably, largely ignoring the fact that there are significant substrain differences within the C57BL/6 strain.1,2 Thus, it is critical that the nephrology community is well aware of the genetic variations among C57BL/6 substrains3 that result in varying susceptibility toward various injury-inducing agents and may have important implications for results and their interpretation. When the C57BL/6J substrain was shown to resist adriamycin-induced glomerulopathy,4,5 it led to a widespread notion that the C57BL/6 strain is resistant to adriamycin.4 In the present investigation, we demonstrate that unlike C57BL/6J, the C57BL/6N substrain is susceptible to adriamycin-induced glomerulopathy. Adriamycin or saline was retro-orbitally administered in 10-week-old C57BL/6J and C57BL/6N mice. Pre- and post-injection urine samples were collected and analyzed by sodium dodecylsulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for albuminuria estimation. While C57BL/6J mice showed complete absence of albuminuria as reported previously (data not shown),2,4 the C57BL/6N mice displayed significant albuminuria at 4 weeks (Figure 1a and b). Further analysis by scanning and transmission electron microscopy showed significant loss of podocyte morphology and foot process effacement that is consistent with adriamycin-induced glomerulopathy (Figure 1c and d). These results are consistent with recent genetic analysis that suggests these 2 substrains are genetically distinct and vary in their susceptibility to a number of factors.3 We believe that these results should persuade investigators and reviewers to consider the substrain differences when reporting their results and during the review of manuscripts where such a difference could have significant implications.

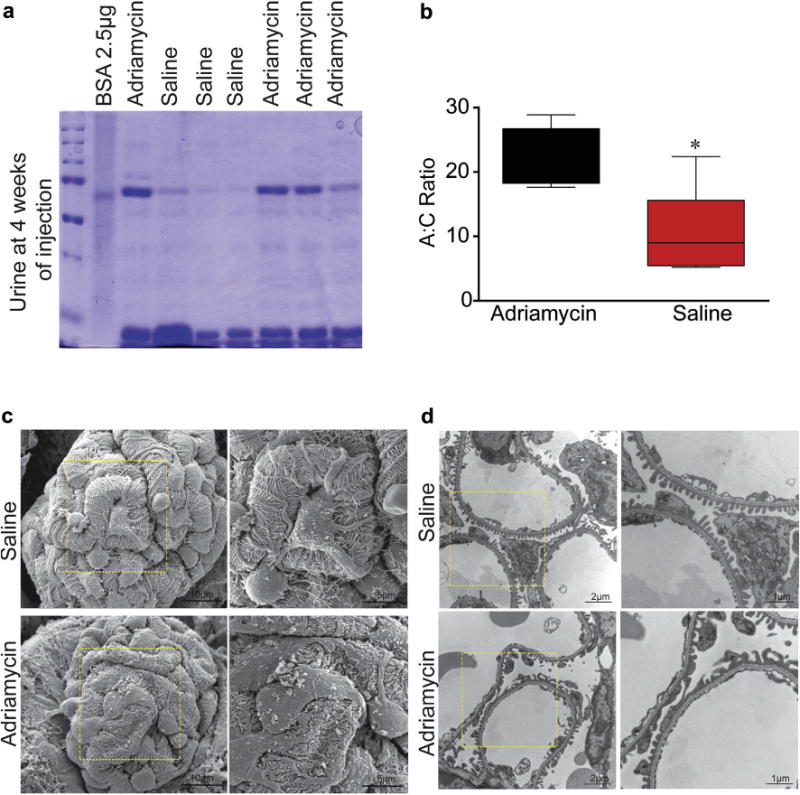

Figure 1. C57BL/6N mice are susceptible to adriamycin-induced injury.

Adriamycin or saline was retro-orbitally injected in anesthetized C57BL/6N mice (n = 6–8) (15 mg/kg of body weight). Urine from each mouse was collected at 1-week intervals, and the 4-week urine samples were analyzed by sodium dodecylsulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by Coomassie blue staining and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to calculate albumin-creatinine ratios. Albuminuria was noted only in adriamycin-injected mice (a and b; *P < 0.05). Scanning and transmission electron microscopy analysis of kidney tissues from these mice further confirms podocyte damage in adriamycin-injected mice only (c and d). BSA, bovine serum albumin.

References

- 1.Hakroush S, Cebulla A, Schaldecker T, et al. Extensive podocyte loss triggers a rapid parietal epithelial cell response. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:927–938. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013070687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnstone DB, Zhang J, George B, et al. Podocyte-specific deletion of Myh9 encoding nonmuscle myosin heavy chain 2A predisposes mice to glomerulopathy. Mol Cell Bi006Fl. 2011;31:2162–2170. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05234-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simon MM, Greenaway S, White JK, et al. A comparative phenotypic and genomic analysis of C57BL/6J and C57BL/6N mouse strains. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R82. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-7-r82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeansson M, Bjorck K, Tenstad O, Haraldsson B. Adriamycin alters glomerular endothelium to induce proteinuria. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:114–122. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007111205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simons M, Hartleben B, Huber TB. Podocyte polarity signalling. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2009;18:324–330. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32832e316d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]