Abstract

Abscisic acid (ABA) plays an essential role in root hair elongation in plants, but the regulatory mechanism remains to be elucidated. In this study, we found that exogenous ABA can promote rice root hair elongation. Transgenic rice overexpressing SAPK10 (Stress/ABA-activated protein kinase 10) had longer root hairs; rice plants overexpressing OsABIL2 (OsABI-Like 2) had attenuated ABA signaling and shorter root hairs, suggesting that the effect of ABA on root hair elongation depends on the conserved PYR/PP2C/SnRK2 ABA signaling module. Treatment of the DR5-GUS and OsPIN-GUS lines with ABA and an auxin efflux inhibitor showed that ABA-induced root hair elongation depends on polar auxin transport. To examine the transcriptional response to ABA, we divided rice root tips into three regions: short root hair, long root hair and root tip zones; and conducted RNA-seq analysis with or without ABA treatment. Examination of genes involved in auxin transport, biosynthesis and metabolism indicated that ABA promotes auxin biosynthesis and polar auxin transport in the root tip, which may lead to auxin accumulation in the long root hair zone. Our findings shed light on how ABA regulates root hair elongation through crosstalk with auxin biosynthesis and transport to orchestrate plant development.

Keywords: ABA, auxin, crosstalk, root hair elongation, transport, biosynthesis, Oryza sativa

Introduction

Roots have important functions in uptake of nutrients and water, and anchoring plants in the soil. Root hairs, extensions from single root epidermal cells, constitute up to an estimated 70% of the root surface area in crops (Richardson et al., 2009; Pereg and McMillan, 2015). Root hairs help plants maintain sufficient levels of water and nutrients; for example, in different plant species under phosphate (P)-limiting conditions, up to 90% of the mineral nutrients appear to be taken up by root hairs (Föhse et al., 1991). In addition, root hairs play important roles in the uptake and transport of NO3- and NH4+ (Gilroy and Jones, 2000). Compared to bald roots, a root 1 mm in diameter with root hairs 0.5 or 1 mm in average length, growing in sand, will improve the soil water uptake rate by 30 to 55% in barley (Segal et al., 2008).

Phytohormones and abiotic stresses affect root hair formation and elongation in Arabidopsis and crops. ABA, a major abiotic stress-responsive hormone, plays an important role in root hair elongation. The application of exogenous ABA leads to root swelling and root hair formation in the tips of young and seminal rice roots, and this process requires de novo synthesis of proteins (Chen et al., 2006). Rice and Arabidopsis plants under moderate water stress (treated with polyethylene glycol) accumulate ABA and grow root hairs with high intensity (Xu et al., 2013).

Work in Arabidopsis has identified a core ABA signaling pathway (Ma et al., 2009; Park et al., 2009; Umezawa et al., 2009; Cutler et al., 2010). The ABA receptors PYRABACTIN RESISTANCE1 (PYR1)/PYRABACTIN RESISTANCE1-LIKE (PYL)/REGULATORY COMPONENTS OF ABA RECEPTOR (RCAR) bind to ABA and then interact with the subclass A type 2C protein phosphatases (PP2Cs), which can suppress SNF1-RELATED PROTEIN KINASE 2 (SnRK2s). As a result, SnRK2s phosphorylate and activate bZIP transcription factors to regulate ABA-responsive gene expression.

Bioinformatics work in rice has identified orthologs of these Arabidopsis ABA signaling components (Kim et al., 2012; He et al., 2014). Rice contains 10 members of the OsPYL/RCAR family, 9 members of the subclass A PP2Cs, 10 SAPKs (Stress/ABA-activated protein kinases), and 10 members of the group A bZIP transcription factors (Kim et al., 2012). OsABIL2, a rice ortholog of AtABI1 and AtABI2, plays a negative role in rice ABA signaling, as OsABIL2 can interact with and dephosphorylate SAPK10 to form an OsPYL1–OsABIL2–SAPK8/10 ABA signaling module (Li et al., 2015). Furthermore, the root hair length of OsABIL2 overexpression lines is significantly reduced (Li et al., 2015). However, little is known about the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms of ABA in regulating root hair development.

Auxin also regulates root hair elongation. Exogenous auxin enhances root hair length, and inhibition of auxin signaling represses root hair elongation (Pitts et al., 1998; Rahman et al., 2002). In Arabidopsis, active polar auxin transport moves auxin to the root tip to regulate root hair elongation, and blocking auxin transport results in short root hair (Pitts et al., 1998; Rahman et al., 2002). Auxin efflux mediated by PIN2 facilitates auxin supply through basipetal auxin transport from the root apex to the root hair differentiation zone (Cho et al., 2007; Cheng et al., 2013). Modeling of auxin flow suggests that auxin influx carrier AUX1-dependent transport through non-hair cells can maintain auxin supply for developing hair cells and sustain root hair outgrowth (Jones et al., 2009). These studies showed that changes in the endogenous or exogenous auxin content through auxin transport in root tip and root hair cells affected root hair elongation.

Formation of the auxin gradient in root tips depends on auxin transport and requires local auxin biosynthesis. Auxin can be synthesized locally in the root tip (Ljung et al., 2005; Petersson et al., 2009), and a simple two-step pathway that converts tryptophan to IAA acts as the main auxin biosynthesis pathway in Arabidopsis (Mashiguchi et al., 2011; Zhao, 2012). Trp is first converted to indole-3-pyruvate (IPA) by the TAA family of amino transferases, and IPA is converted into IAA by the YUCCA (YUC) family of flavin monooxygenases. Accordingly, overexpression of the auxin biosynthesis gene YUCCA1 in Arabidopsis enhanced root hair growth compared to wild type (Zhao et al., 2001) and inhibition of auxin biosynthesis using L-amino-oxyphenypropionic acid (AOPP) blocked the formation of root hairs, which can be rescued by the application of exogenous IAA (Soeno et al., 2010).

Many studies have suggested that ABA interacts with auxin to regulate root growth and development (Kobayashi et al., 2005; Vanstraelen and Benková, 2012). For example, the mutants of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 2 (ARF2), which affects auxin-mediated responses, show enhanced ABA sensitivity during seed germination and primary root growth, and ABA treatment alters auxin distribution in Arabidopsis primary root tips (Wang et al., 2011). ABI4 mediates ABA’s inhibition of lateral root formation via reduction of polar auxin transport, resulting in decreased auxin levels in roots (Shkolnik-Inbar and Bar-Zvi, 2010). Auxin may act as an organizer of hormonal signals for root hair growth (Lee and Cho, 2013). However, it remains unclear whether the ABA-induced root hair elongation in rice occurs through polar auxin transport or local auxin biosynthesis in the root tip.

In this study, we used transgenic lines with enhanced ABA signaling (SAPK10 overexpression) or attenuated ABA signaling (OsABIL2 overexpression) to study how ABA signaling regulates root hair elongation. We found that ABA signaling promotes root hair length in root tips and that the ABA-promoted root hair elongation requires polar auxin transport. Our RNA-seq analysis found that ABA enhances both auxin transport and auxin biosynthesis in root tips and identified a set of genes co-regulated by ABA and auxin to promote root hair length.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

The wild-type rice Dongjin (O. sativa L. cv. japonica) was used in this work. The OsABIL2 and OsSAPK10 overexpression transgenic lines were in the Dongjin background, and the detail of OsABIL2 overexpression transgenic lines were introduced in previous study (Li et al., 2015). The auxin-related transgenic rice lines DR5-GUS (ZH11 background), OsPIN1b-GUS, OsPIN1c-GUS, OsPIN2-GUS, OsPIN5a-GUS, and OsPIN10a-GUS were from a previous study (Wang et al., 2009). For polar auxin transport assays by crown root GUS staining, the F1 hybrid of OsABIL2-OE X DR-GUS and DJ X DR5-GUS lines was used.

For physiological analysis, the rice seeds were imbibed for 2 days at 30°C, and the germinated seeds were then transferred to bottom-cut 96-well PCR plates. Seedlings were grown on water with a 16-h (light, 28°C)/8-h (dark, 25°C) rhythm for the indicated days, which was defined as normal conditions in this study.

Generation of Transgenic Rice Plants

For overexpressing SAPK10, the genomic sequence of Os03g0610900 was cloned into the binary vector pCAMBIA1306 fused with a FLAG-tag at the C-terminus. The primers used for cloning OsSAPK10 are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Phytohormone and Chemical Treatments of Plant Materials

For measurement of SAPK10-OE expression level, roots of the 7-day-old wild-type and transgenic seedlings grown under normal conditions were cut, and the samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C for RNA extraction.

For root hair induction assays, the 5-day-old normal grown seedlings were transferred to solutions with or without the following additions: ABA (100 mM dissolved in ethanol and in order to add the same amount of ethanol between treatment group and mock, we gradient dilution ABA to 20 mM, 10 mM, 5 mM, 2 mM, and 1 mM solution), NAA (100 mM dissolved in ethanol, and in order to add the same amount of ethanol, we gradient dilution NAA to 5 and 1 mM solution), the ABA biosynthesis inhibitor fluridon (FLU) (100 mM dissolved in ethanol), the auxin efflux inhibitor NPA (100 mM dissolved in DMSO), and the control added the same amount of ethanol and/or DMSO. After 24 h, the crown roots were fixed in FAA solution (ethanol: acetic acid: 37% formaldehyde: H2O = 50:5:10:35, v/v), and then photographed with a stereoscopic microscope (Carl Zeiss Discovery V20).

For β-glucuronidase (GUS) staining, crown roots were immersed in the GUS staining solution (1 mg/ml X-glucuronide in 100 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.2, 0.5 mM ferricyanide, 0.5 mM ferrocyanide, and 0.1% Triton X-100), briefly subjected to a vacuum, and then incubated at 37°C in the dark. The stained plant roots were photographed using Carl Zeiss Discovery V20 stereomicroscope.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Crown roots of the 6-day-old seedlings were cut and fixed in FAA solution overnight. The fixed samples were dehydrated in an ethanol series of 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, and 100% ethanol for 1 h each, and then treated with ethanol: tert-butyl alcohol (v/v), 3:1, 1:1, and 1:3 for 1 h each. Finally, the samples were kept in pure tert-butyl alcohol. After vacuum freeze-drying, the samples were sputter-coated with Au-Pd and further visualized with a scanning electron microscope (Hitachi TM3000). For observation of root hair initiation, we screened the root tip from the root apex to the root hair zone.

Root-Hair Length Measurement

Root hairs were observed, and images were captured with a Discovery V20 Stereomicroscope (Carl Zeiss). The zone of root hair growth is 4–5 mm from the root apex. At least 15 crown roots were measured, and 20 root hairs of each root were measured. Root-hair length measurements were performed with ImageJ1.

Quantification of IAA

To analyze IAA concentrations, firstly, according to the root hair phenotype, we divided the root tips of rice crown roots into three regions: short root hair zone (SRH), long root hair zone (LRH), and root tip zone (Tip) (Supplementary Figure 3). Each region was excised from at least 96 five-day-old seedlings treated with 0.5 μM ABA for 24 h, or not treated as a control. Samples were separated under Carl Zeiss Discovery V20 stereomicroscope and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, afterward stored at -80°C. Samples were powdered in liquid nitrogen and at least 30 mg powder homogenized in 750 μl of cold extraction buffer 1 [methanol: H2O: acetonitrile = 80:19:1 (v/v), 10 ng/ml d5-IAA], then shade and shake at 4°C 16 h (300 rpm). Samples were centrifuged at 4°C at 13,000 rpm for 10 min, the supernatant is transferred to another Eppendorf tube. Add 450 μl of cold extraction buffer 2 [methanol: H2O: acetonitrile = 80:19:1 (v/v)] into precipitate, shade and shake at 4°C 4 h (300 rpm), centrifuged at 4°C at 13,000 rpm for 10 min, combine two supernatants, transfer supernatant through 0.22 μm filter to a new Eppendorf tube. Then each sample was dried using nitrogen flow and re-dissolved in 200 μl of 30% cold methanol 3–6 h. Quantification was performed in an ABI 4000Q-TRAR LC-MS system (Applied Biosystems, United States) with stable, isotope-labeled auxin as the standard (OlChemIm, Czech Specials) according to a method described previously (Liu et al., 2012).

Quantitative Real-Time PCR Assays

The qRT-PCR assays were carried out as described previously with small modifications (Zhang et al., 2009). The primers for qRT-PCR were designed with NCBI Primer-Blast2 to avoid the homologous regions, shown in Supplementary Table 1. Total RNA was extracted with the Plant RNAprep Kit (Tiangen). About 2 μg DNase-treated RNA was used for reverse transcription (M-MLV reverse transcriptase, TaKaRa). The RT-PCR amplifications were carried out with a Bio-Rad CFX system, and PCR products were monitored with SYBR green dye. The expression level was normalized by the expression of OsACTIN1 (LOC_Os03g50885, internal control), and RT-qPCR results were analyzed by the 2-ΔΔCT method using Bio-Rad CFX Manager 3.1 software.

Sample Collection and RNA Isolation for RNA-Seq

According to the root hair phenotype, we divided the root tips of rice crown roots into three regions: short root hair zone (SRH), long root hair zone (LRH), and root tip zone (Tip). Each region was excised from at least 96 five-day-old seedlings treated with 0.5 μM ABA for 24 h, or not treated as a control. Samples were separated and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and afterward stored at -80°C until RNA isolation. Total RNA was extracted from each tissue using TRIzol (Invitrogen). RNA purity was checked with a NanoPhotometer spectrophotometer (IMPLEN, Munich, Germany) and RNA integrity was assessed with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA, United States).

The cDNA Library Preparation and Transcriptome Sequencing

Two biological replicates were used for RNA-seq experiments for each tissue type. A total amount of 3 μg RNA per sample was used as input material for the RNA sample preparations. The samples were sent to Beijing Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The sequencing libraries were constructed using a NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB, Ipswich, MA, United States) following the manufacturer’s recommendations, and index codes were added to attribute sequences to each sample. Briefly, mRNA was purified from total RNA using poly(T) magnetic beads. Quality of these libraries was assessed with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer system. The clustering of the index-coded samples was performed with a cBot Cluster Generation System using a TruSeq PE Cluster Kit v3-cBot-HS (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After cluster generation, the libraries were sequenced on an Illumina Hiseq 4000 platform and 150-bp paired-end reads were generated.

In this study, the genes with a significant (P ≤ 0.05) fold change > 2 or < -2 between the control and ABA treatment were defined as differentially expressed genes responding to ABA stimulation.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS 20.0 software. One-way analysis of variance was used, and comparison between the two groups was performed using the least significant difference (LSD) test. Differences were considered significant if P < 0.05.

Functional Enrichment Analysis

Gene ontology analysis was carried out using the Singular Enrichment Analysis (SEA) tool offered by agriGO (Du et al., 2010) at default settings of Fisher t-test (P < 0.05), False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction by Hochberg method and five minimum number of mapping entries against the rice-specific precomputed background reference.

Results

ABA Regulates Root Hair Growth in Rice

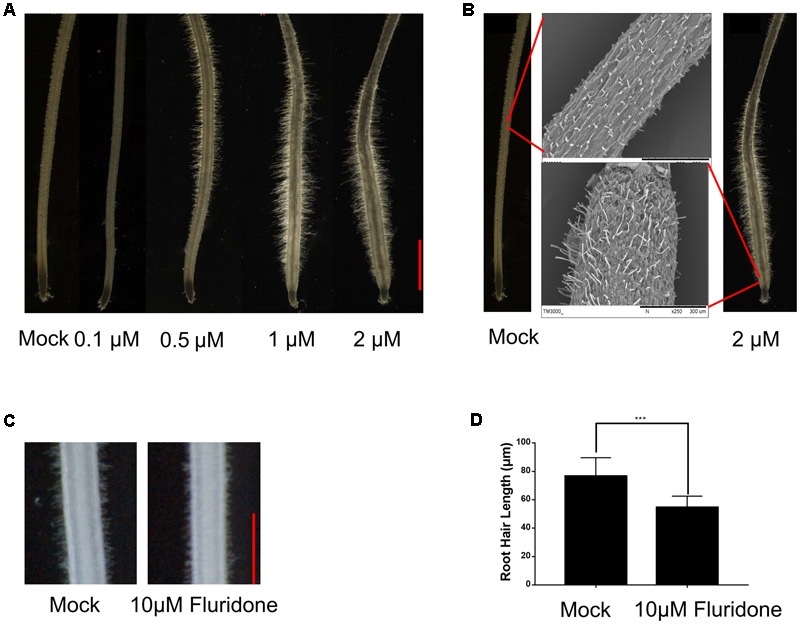

To understand how plants adapt to environmental stresses, we tested whether the stress-responsive hormone ABA affects root hair growth in the Dongjin (DJ) cultivar of rice. Crown roots of the 5-day-old seedling were treated with exogenous ABA at concentrations of 0.1, 0.5, 1, and 2 μM for 24 h. As shown in Figure 1A, in the seedlings treated with 0.1 μM ABA, the root hair length was significantly less than in the control seedlings not treated with ABA. However, treatments with 0.5, 1, and 2 μM ABA significantly enhanced root hair elongation, indicating higher concentrations of ABA can promote root hair elongation, and we used the ABA concentrations of 0.5 and 2 μM for further studies.

FIGURE 1.

ABA promotes root hair elongation in the rice root tips. (A) The 5-day-old rice root tips grown in solution containing the indicated concentrations of ABA for 24 h. Scale bar = 1 mm. (B) Morphology of root hair initiation zones in the 6-day-old crown roots treated with mock or 2 μM ABA for 24 h. (C) Root hair morphology of the wild type with or without Fluridon (10 μM) treatment. Scale bar = 500 μm. (D) Quantification of root hair length of the wild type with or without Fluridon treatment. Data are means ± SD.

We also used SEM to observe root hair morphology. We found that most root hairs initiated in the region about 3 mm from the root apex under normal growth conditions, but most root hairs initiated in the region about 0.2 mm from the apex in roots treated with 2 μM ABA for 24 h. We also further confirmed that the root hair length increased in response to ABA treatment (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure 1). These results indicated that exogenous ABA not only enhances root hair length, but also promotes earlier root hair initiation. In addition, fluridone as an ABA biosynthetic inhibitor (10 μM) was used to investigate the effect of ABA on root tip responses under moderate water stress in rice and Arabidopsis (Yoshioka et al., 1998; Xu et al., 2013). The treatment of fluridon significantly repress the root hair length (Figures 1C,D). We measured the root hair length which located 4–5 mm distant from root apex in Figure 1D, this because considering the several ABA concentration treatment of root hair phenotype, we found that the best region to measure root hair length located at 4–5 mm distant from root tip.

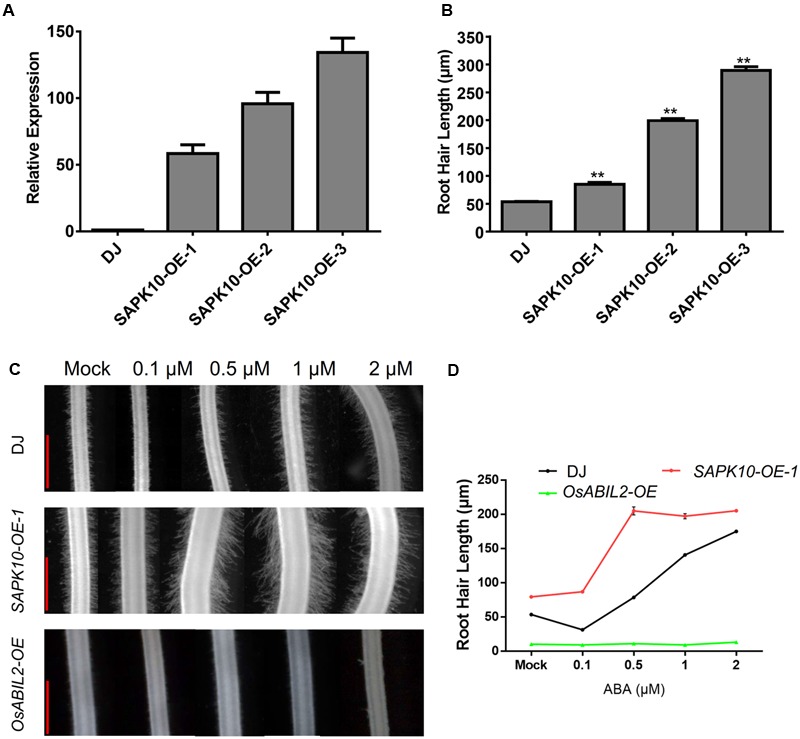

ABA Signaling Promotes Root Hair Elongation

To investigate whether ABA promotes root hair elongation through the major ABA signaling components, we constructed rice lines overexpressing SAPK10, which plays a positive role in the ABA signaling. Three of the SAPK10 overexpression lines showed ∼60-fold, ∼100-fold, and ∼130-fold increases in SAPK10 expression in the roots of the 7-day-old seedlings (Figure 2A). Then we measured the length of root hairs in these lines and found that the SAPK10 overexpression significantly enhanced root hair elongation (Figure 2B and Supplementary Figure 2). However, root hairs were rarely observed in the transgenic lines expressing OsABIL2, which is a negative regulator of rice ABA signaling (Figure 2C). The next to detect the root hair of SAPK10-OE and OsABIL2-OE response to ABA treatment, we would like to clarify the SAPK10-OE-1 was used in this study. Because this SAPK10-OE-1 line has moderate overexpression level of SAPK10 gene, which lead to moderate response to ABA treatment suitable for comparison with the wild type. While the other two lines SAPK10-OE-2, and -3 have much higher level expression of SAPK10 than the SAPK10-OE-1 line (Figure 2A), which lead to root hair elongation in the region very close to the root tip in the other two lines, rather than in the region 4–5 mm from the root tip after ABA treatment (Supplementary Figure 2). Considering these factors, we choose the SAPK10-OE-1 line for all other experiments for better comparison to the wild type after ABA treatments. With the 0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, and 2 μM ABA treatments (Figures 2C,D), the root hair length of the SAPK10-OE-1 line increased much more than that of the wild-type DJ. In contrast, ABA treatment did not increase root hair elongation of the OsABIL2-OE plants, which is a negative regulator of rice ABA signaling. This indicated that the effect of ABA on root hair elongation largely depends on the major PYR/PP2C/SnRK2 signaling pathway.

FIGURE 2.

ABA-induced root hair elongation is dependent on ABA signaling. (A) Expression level of SAPK10 in the SAPK10-OE lines determined by quantitative RT-PCR. Seven-day-old roots were used. (B) Root hair length of the SAPK10-OE line. The root hairs located about 4–5 mm from the root apex were measured. About 20 longest root hairs from each of the 15 crown roots were measured. Data are means ± SE. (C) Root hair morphology of the wild type, and the SAPK10-OE-1 and OsABIL2-OE transgenic lines. Five-day-old seedlings were treated with different concentrations (0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, and 2 μM) of ABA for 24 h. Scale bar = 500 μm. (D) Quantification of root hair length of the wild type, SAPK10-OE, and OsABIL2-OE lines. Data are means ± standard error (SE).

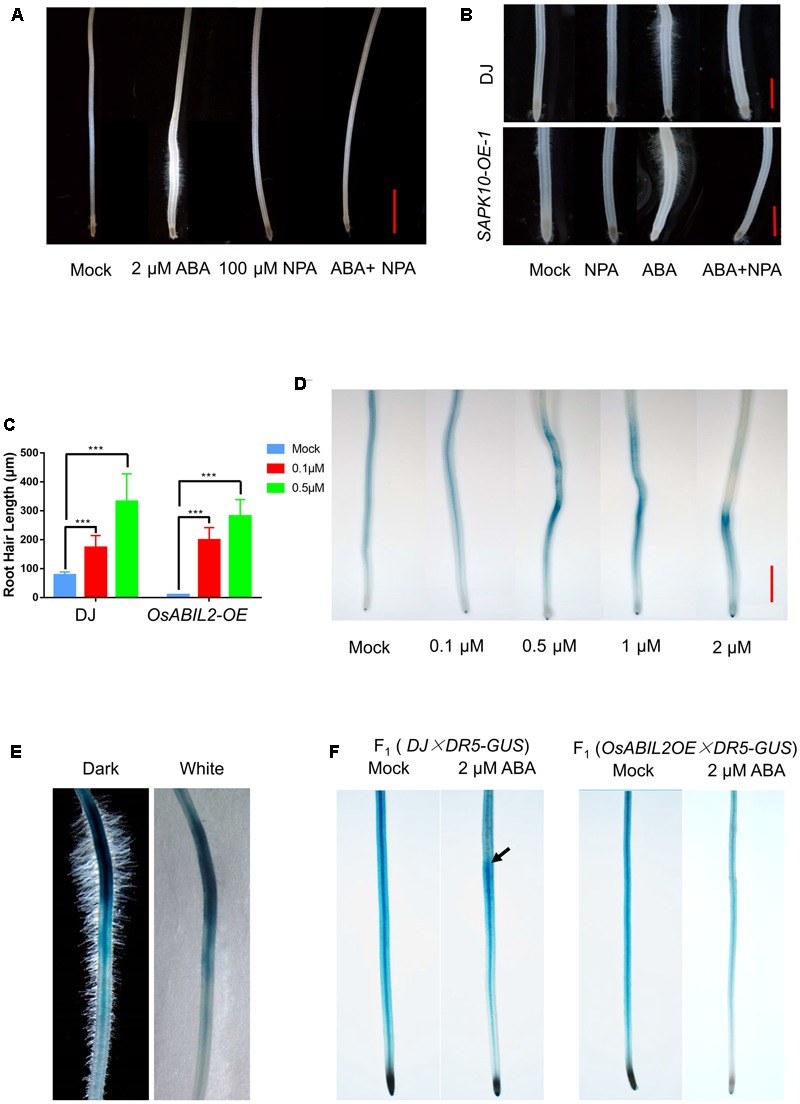

Polar Auxin Transport Is Required for the ABA-Mediated Root Hair Elongation

Auxin has a positive effect on root hair elongation without affecting the determination of root hair cell fate in Arabidopsis (Masucci and Schiefelbein, 1994, 1996; Pitts et al., 1998; Cho and Cosgrove, 2002). Therefore, we asked whether the ABA-regulated root hair elongation in rice also requires auxin transport. Then we used the auxin efflux inhibitor NPA to examine this. The 5-day-old wild-type seedlings were treated with ABA, NPA, or ABA plus NPA for 24 h. As shown in Figure 3A, ABA plus NPA treatment inhibited root hair elongation as compared with ABA alone. Similarly, in the SAPK10-OE line, ABA plus NPA also severely inhibited the root hair elongation as compared with the wild type shown in Figure 3B. We then examined whether additional auxin can rescue the reduced root hair elongation in the OsABIL2-OE, using the 5-day-old seedlings of OsABIL2-OE treated with 0.1 μM or 0.5 μM NAA for 24 h. As shown in Figure 3C, compared with Mock, 0.5 μM of NAA can significantly rescue the root hair length of OsABIL2-OE. Taken together, these results indicated that auxin acts downstream of ABA to mediate the ABA-induced root hair elongation.

FIGURE 3.

Auxin acts downstream of ABA signaling to promote root hair elongation. (A) Effect of the polar auxin transport inhibitor NPA on root hair elongation. Five-day-old seedlings were grown in solutions containing the indicated concentrations of ABA and/or NPA for 24 h. Scale bar = 2 mm. (B) Root hair elongation of the SAPK10-OE plants in response to ABA and NPA treatments. Five-day-old seedlings were grown in solutions containing the indicated concentrations of ABA and/or NPA for 24 h. Scale bar = 1 mm. (C) Quantification of root hair length of the OsABIL2-OE plants and wild type in response to the exogenous auxin. Five-day-old seedlings were grown in solutions containing 0, 0.1, or 0.5 μM NAA for 24 h. Data are means ± SD. (D) ABA affects the concentration and distribution of auxin indicated by the DR5-GUS reporter. Five-day-old seedlings were grown in solutions containing different concentrations of ABA for 24 h. Scale bar = 2 mm. (E) Close-up view of the long root hair zone of the DR5-GUS line treated with 0.5 μM ABA for 24 h. Images with dark (left) and white (right) backgrounds are shown. (F) The GUS activity in the F1 seedlings in response to treatment with 2 μM ABA for 24 h. Wild type (DJ) and the OsABIL2-OE plants were crossed with the DR5-GUS line (Zhonghua11 background,  ). Five-day-old seedlings were used. Black arrows indicate the accumulation of DR5-GUS in the long root hair zone.

). Five-day-old seedlings were used. Black arrows indicate the accumulation of DR5-GUS in the long root hair zone.

To address whether ABA influences local auxin concentrations, we used a DR5-GUS rice line, which has been widely used as a marker line for monitoring endogenous auxin levels in plants (Yamamoto et al., 2007). The 5-day-old DR5-GUS seedlings were treated with 0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, or 2 μM ABA for 24 h, then we stained their roots for GUS activity. We found that DR5 was widely expressed in the crown roots, especially in their steles, and with increased concentrations of exogenous ABA, the GUS staining gradually accumulated close to the root tip and in the outer layers of the roots (Figure 3D). With a higher magnification, we observed that the region with the strongest GUS signal produced the longest root hairs (Figure 3E), suggesting that the ABA-promoted local auxin accumulation may lead to the specified root hair elongation.

We further tested whether the ABA-induced auxin response is dependent on ABA signaling by crossing the DR5-GUS into the OsABIL2-OE background; the wild type crossed with DR5-GUS (ZH11 background) was used as a control. The GUS staining showed that ABA treatment did not cause auxin redistribution in the OsABIL2-OE crown roots (Figure 3F), indicating that ABA signaling promotes auxin accumulation in the root tip to induce root hair elongation. The DR5-GUS staining patterns look different between Figures 3D,F. There may be two reasons. First, in Figure 3F, F1 seeds were used for the observation, which contains half dosage of the reporter gene GUS. Therefore, the GUS staining apparently is weaker in Figure 3F than in Figure 3D. In general, the relative staining density and the trends of DR5-GUS expression pattern between Figures 3D,F are similar.

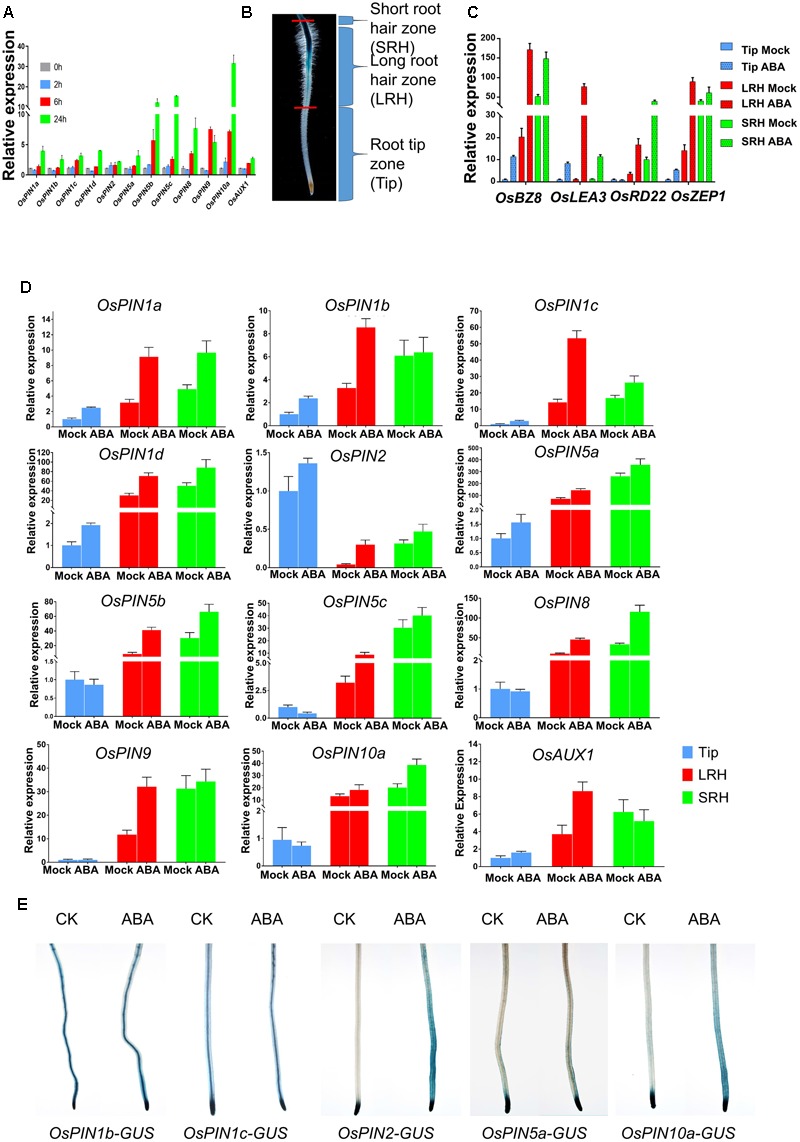

ABA Modulates the Expression Level and Pattern of Genes Involved in Auxin Transport

Auxin redistribution is mainly controlled by auxin transporters, which include the influx transporters of the AUXIN1/LIKE AUX1 (AUX1/LAX) family (Kerr and Bennett, 2007; Swarup et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2015), and efflux transporters of the PIN-FORMED (PIN) families (Petrasek et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2009). To test how ABA signaling regulates auxin transport, we investigated the ABA-regulated expression of the major genes involved in auxin transport. We found that the mRNA levels of OsPINs and OsAUX1 were induced by treatment with 2 μM ABA at 6 and 24 h (Figure 4A).

FIGURE 4.

ABA regulates the expression of OsPINs to promote polar auxin transport in root tips. (A) Expression of OsPINs is induced by ABA in 5-day-old rice roots. Expression of each PIN gene was determined by quantitative RT-PCR and 2 μM ABA was used in this assay. OsActin1 was used as an internal control. Three replicates were conducted. Data are means ± SD. (B) Definition of the root hair zones. Root tips were divided into three regions: short root hair zone (SRH), long root hair zone (LRH), and root tip zone (Tip). Each region was cut and collected from at least 96 five-day-old seedlings with or without 0.5 μM ABA treatment for 24 h. (C) Expression of ABA-responsive genes OsLEA3, OsBZ8, OsZEP1, and OsRD22 in the Tip, LRH and SRH zones after ABA treatment. Data are means ± SD. (D) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of OsPINs in the SRH, LRH and Tip treated with or without 0.5 μM ABA for 24 h. The expression level of each gene in the untreated Tips was defined as “1.” Data are means ± SD. (E) The GUS activity of the OsPINs-GUS in the 5-day-old rice seedlings in response to 0.5 μM ABA for 12 h.

To examine the spatial expression of these genes, we divided the root tip into three zones according to the root hair distribution and DR5-GUS activity: the short root hair zone (SRH), long root hair zone (LRH), and root tip zone (Tip) (Figure 4B and Supplementary Figure 3). First, we tested expression of the ABA marker genes OsLEA3, OsBZ8, OsZEP1, and OsRD22 after ABA treatments (Figure 4C), and the result showed that all of the ABA marker genes (except OsRD22 in Tip) were induced in the three different zones. We then detected the expression of OsPINs in the three zones and found that most of the OsPINs were induced by the ABA treatment (Figure 4D). Second, we used the GUS reporter lines driven by various OsPIN promoters (OsPIN1b-GUS, OsPIN1c-GUS, OsPIN2-GUS, OsPIN5a-GUS, and OsPIN10a-GUS) (Wang et al., 2009) to visualize the OsPIN expression pattern. We found that the expression of OsPIN1b-GUS, OsPIN1c-GUS, and OsPIN5a-GUS was not dramatically altered by ABA treatment, but the expression of OsPIN2-GUS and OsPIN10a-GUS was significantly enhanced by ABA treatment, especially in the outer layers of the root (Figure 4E). In this assay, we indeed found that there were some different between real-time RT-PCR and GUS staining. In general, real-time RT-PCR or promoter-GUS has their own advantages and disadvantages. First, real-time RT-PCR cannot distinguish the specific expression tissue, which may mask some tissue specific signals. Second, the promoter-GUS approach has a defect on the specificity of promoter, because some times, ones do not known what the exact promoter size in plants. Therefore, the combination of these two approaches will show the expression pattern more accurately. This assay we wanted to show the genes expression fold change used the real-time RT-PCR, and GUS staining to show tissue specificity. In Arabidopsis, PIN2 is expressed in the epidermal cells (Wisniewska et al., 2006). We also checked the rice microarray expression database (RiceXPro3, OsPIN2 Locus ID: Os06g0660200, OsPIN10a Locus ID: Os01g0643300), and found that OsPIN2 and OsPIN10a were especially expressed in the epidermal cells (Supplementary Figures 4A,B). Therefore, we concluded that ABA-promoted root hair elongation likely requires functional basipetal auxin transport.

RNA-Seq Analyses of the ABA-Treated Root Tips

To obtain a global view of the differential expression of genes related to ABA-induced root hair elongation, the 5-day-old seedlings were treated without or with 0.5 μM ABA for 24 h, then the three different zones (SRH, LRH, and Tip) of root tips were collected to analyze transcript profiles (Supplementary Figure 3). We conducted two biological replicates and analyzed their repeatability by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient (Supplementary Figure 5A), which indicates these results are consistent and repeatable.

To confirm the result that ABA promotes auxin transport and to validate the RNA-seq accuracy, we used RNA-seq to analyze the expression of OsPINs, OsAUX, and PINOID (PID). Arabidopsis PID encodes a serine/threonine protein kinase that regulates auxin redistribution through control of the subcellular localization of PINs (Robert and Offringa, 2008). As shown in Supplementary Figure 5B, ABA treatment promotes auxin transport by enhancing expression of OsPINs, OsAUX, and OsPID, especially in the Tip and LRH zones, consistent with the qRT-PCR (Figure 4D) and OsPINs-GUS staining results (Figure 4E). The results also showed a high correlation (R2 = 0.84, Supplementary Table 2) between the RNA-seq and qRT-PCR data.

ABA Promotes Auxin Biosynthesis

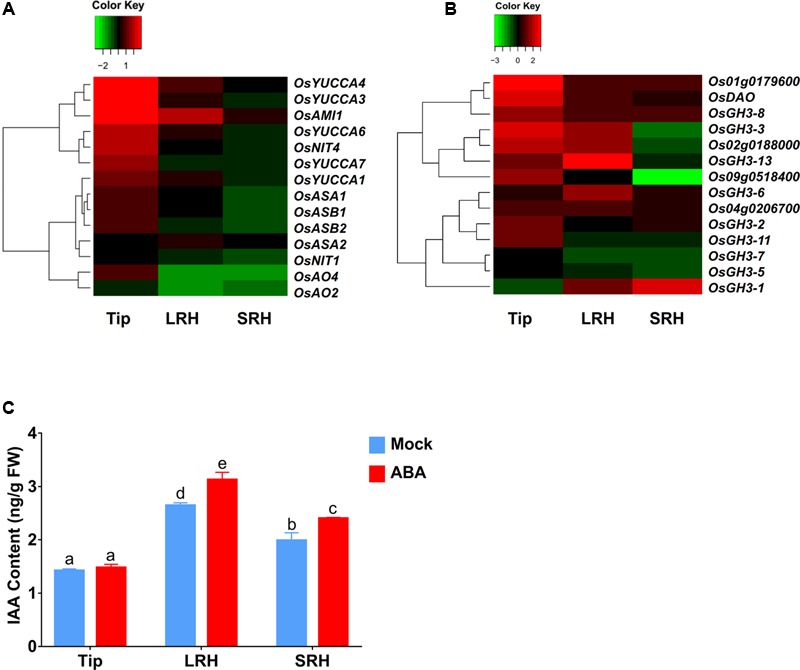

In addition to increasing auxin transport to the LRH zone, enhanced local auxin biosynthesis or reduced local auxin degradation could also increase local auxin concentrations, as indicated by the enhanced DR5-GUS expression in the LRH zone. Therefore, we first used our RNA-seq data to measure the expression levels of genes involved in auxin biosynthesis, including OsYUCCAs (Yamamoto et al., 2005), OASA (Kanno et al., 2004), OASB, OsNIT, OsAO, and OsAMI. These data showed that almost all of these auxin biosynthesis genes were upregulated after ABA treatment in the root tips (Figure 5A and Supplementary Table 4) and that OsAMI1 (∼3.6-fold), OsYUCCA4 (∼1.8-fold), and OsYUCCA1 (∼1.4-fold) were upregulated in the LRH zone.

FIGURE 5.

ABA promotes local auxin biosynthesis and accumulation in the LRH zone. (A) Auxin biosynthetic gene expression profile in Tip, LRH, and SRH under ABA treatments. (B) Auxin metabolic gene expression profile in Tip, LRH, and SRH under ABA treatments. (C) Quantification of IAA level in the Tip, LRH, and SRH under ABA treatments.

We then checked the expression of the genes encoding IAA-amido synthetases of the GH3 family, key enzymes involved in the conversion of active IAA to an inactive form via conjugation of IAA with amino acids, such as Asp, Ala, and Phe (Fu et al., 2011). We also examined the genes encoding members of the UDP glycosyltransferase (UGT) family and dioxygenase for auxin oxidation (OsDAO) (Bowles et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2013; Kasahara, 2016). In rice, 10 of the 14 genes involved in IAA inactivation were upregulated in the tip zone, and 9 of them were also upregulated in the LRH but not expressed in the SRH (Figure 5B and Supplementary Table 4), suggesting that the enhanced auxin transport and biosynthesis in the Tip and LRH zones of rice roots are the major reasons for local auxin accumulation, and the enhanced auxin inactivation is most likely caused by negative feedback regulation.

We also measured the endogenous IAA levels in the Tip, LRH, and SRH zones of the rice root. As shown in Figure 5C, auxin accumulated in the LRH zone, but not in the Tip, and the IAA concentration in the LRH zone after ABA treatment was significantly higher than in the untreated roots. We should note that the DR5-GUS staining shows strong signal in the root tip, indicating high concentration auxin in the root tip. However, we measured the IAA concentration in Tip, LRH, and SRH, and found the different IAA concentration between “Tip” and the typical root tip as shown in Supplementary Figure 3. We would like clarify here that the defined “Tip” here includes not only the classical root tip region but also the meristematic zone, transition zone, and root hair zone under the LRH, which covers a larger region. In addition, we used the roots from the 5-day-old seedling, and the majority of auxin may be from the shoot by transport.

A Number of Genes Regulated by Auxin Are Involved in Root Hair Elongation in Response to ABA

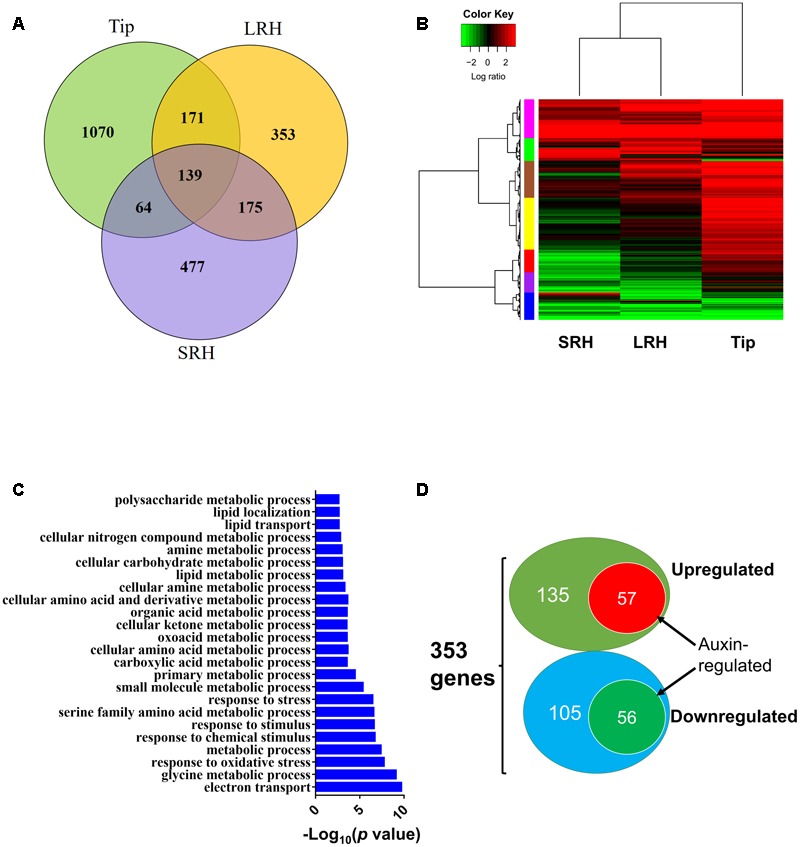

To extend our analysis, we globally analyzed the genes differentially regulated in response to exogenous ABA in the three regions of root tips. We identified 1444, 838, and 855 genes that were differentially expressed before and after ABA treatment in Tip, LRH, and SRH, respectively. Of these, 1070, 353, and 477 genes were altered specifically in Tip, LRH, and SRH, respectively (Figure 6A). Further clustering analysis of these differentially expressed genes in each zone indicated that most of the ABA upregulated genes are in the Tip, followed by the LRH, and the fewest in the SRH (Figure 6B). These results suggest that the rice root tip cells rapidly sense and respond to ABA.

FIGURE 6.

Differentially expressed genes after ABA treatment in the rice root tip (Tip), long root hair (LRH), and short root hair (SRH) zones. (A) Venn diagram showing the differentially expressed genes in the Tip, LRH and SRH zones in response to treatment with 0.5 μM ABA for 24 h. (B) Hierarchical clustering analysis of the differentially expressed genes in the Tip, LRH, and SRH zones with or without 0.5 μM ABA treatment for 24 hrs. (C) GO term analyses shows the biological processes (BPs) enriched in the LRH before and after ABA treatments. (D) Venn diagram showing the overlapping differentially expressed genes regulated by ABA and auxin in the LRH zone. The auxin-regulated genes were based on the RiceXPro database.

To understand the overall biological processes that occurred in the LRH zone in response ABA treatment, we performed gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of the 353 differentially expressed genes in the LRH; this identified 24 significantly (FDR < 0.05) enriched GO terms (Figure 6C) in two big categories. The first category includes GO terms involved in stress responses, such as “response to oxidative stress,” “response to chemical stimulus,” “response to stimulus,” and “response to stress.” The second category includes GO terms involved in “metabolic process,” such as “glycine metabolic process,” “small molecule metabolic process,” “primary metabolic process,” “cellular amino acid and derivative metabolic process,” “lipid metabolic process,” “cellular carbohydrate metabolic process,” and “polysaccharide metabolic process.” Then, we found 19 stress-responsive genes specifically responding to ABA in LRH (Supplementary Table 3). Nine of the 19 stress-responsive genes encode peroxidases, suggesting that reactive oxygen species have important roles in root hair growth in response to ABA treatment.

Because of the importance of auxin in root hair elongation, to understand whether these differentially expressed genes are related to ABA-regulated root hair elongation, we checked whether auxin affects the 353 genes that are differentially expressed in the LRH by comparing the genes to the auxin-regulated genes in the RiceXpro database (Sato et al., 2013). As shown in Figure 6D, among the 192 ABA upregulated genes, 57 (∼29.7%) were also upregulated by auxin (Table 1), and 56 of the 161 ABA downregulated genes were also repressed by auxin (Table 2). This suggests that auxin plays an important role in ABA-promoted rice root hair elongation, and the 113 genes co-regulated by both ABA and auxin in the LRH zone may function directly in regulating root hair elongation. We found that OsPIN9 and OsPP2C 59 are upregulated, further supporting the importance of polar auxin transport in root hair elongation.

Table 1.

ABA and Auxin upregulated genes specially changed in LRH under ABA treatment.

| Gene_ID | Log2 (FC) | Gene description |

|---|---|---|

| OS01G0251400 | inf | Os01g0251400 protein |

| OS11G0454200 | inf | Dehydrin Rab16B |

| OS06G0279900 | inf | Putative NBS-LRR class RGA |

| OS09G0109600 | inf | Putative uncharacterized protein |

| OS12G0455000 | 7.06 | Expressed protein |

| OS01G0802700 | 6.16 | Probable auxin efflux carrier component 5 |

| OS03G0432100 | 4.73 | Similar to orthophosphate dikinase precursor |

| OS01G0113800 | 4.32 | Putative rust resistance kinase Lr10 |

| OS08G0101800 | 4.10 | Putative uncharacterized protein B1147B12.20 |

| OS04G0560100 | 3.98 | OSJNBa0084K11.4 protein |

| OS03G0702100 | 3.55 | Hypothetical protein |

| OS06G0698300 | 3.51 | Probable protein phosphatase 2C 59 |

| OS05G0424300 | 3.44 | Putative cytochrome P450 |

| OS05G0373900 | 3.38 | putative peptide chain release factor subunit 1 (ERF1) |

| OS07G0142500 | 3.36 | Early nodulin 75-like protein |

| OS07G0587300 | 3.13 | Putative uncharacterized protein OJ1047_C01.8 |

| OS07G0599300 | 3.12 | Proline-rich protein family-like protein |

| OS07G0541200 | 3.05 | Putative serine/threonine kinase protein |

| OS08G0412800 | 3.05 | Os08g0412800 protein; putative uncharacterized protein OSJNBa0007M04.21 |

| OS02G0466400 | 3.03 | Similar to inositol phosphate kinase |

| OS07G0142700 | 2.95 | N-hydroxycinnamoyl benzoyltransferase-like protein |

| OS03G0286900 | 2.93 | Putative low-temperature induced protein |

| OS02G0631100 | 2.81 | Putative uncharacterized protein B1250G12.8 |

| OS06G0610800 | 2.81 | Putative nucleoid DNA-binding protein cnd41, chloroplast |

| OS10G0345100 | 2.75 | Multi antimicrobial extrusion protein MatE family protein |

| OS09G0517100 | 2.73 | NB-ARC domain containing protein |

| OS04G0639100 | 2.70 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| OS07G0599600 | 2.63 | Early nodulin 75-like protein |

| OS03G0807900 | 2.59 | Expressed protein |

| OS07G0599900 | 2.54 | Putative uncharacterized protein OJ1634_B10.117 |

| OS01G0177900 | 2.52 | ABC-2 type transporter domain containing protein |

| OS04G0301500 | 2.52 | Helix-loop-helix DNA-binding domain containing protein |

| OS12G0154800 | 2.47 | Germin-like protein 12-2 |

| OS03G0820300 | 2.42 | C2H2 transcription factor; putative Cys2/His2 zinc-finger protein; zinc finger protein ZFP182 |

| OS07G0599500 | 2.38 | Early nodulin 75-like protein |

| OS09G0468300 | 2.37 | RING-H2 zinc finger protein ATL6-like |

| OS12G0154900 | 2.33 | Putative germin-like protein 12-3 |

| OS06G0164400 | 2.32 | Basic helix-loop-helix dimerization region bHLH domain containing protein |

| OS09G0471200 | 2.30 | EGF-like calcium-binding domain containing protein |

| OS01G0836600 | 2.28 | Putative ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCG2 |

| OS05G0573300 | 2.27 | CTP synthase |

| OS08G0137800 | 2.26 | Cupredoxin domain containing protein. |

| OS01G0692100 | 2.18 | Uncharacterized protein |

| OS07G0676600 | 2.17 | Putative uncharacterized protein OJ1167_G06.116; cDNA, clone |

| OS07G0599700 | 2.14 | Proline-rich protein family-like protein |

| OS01G0952500 | 2.12 | Type A response regulator 4 |

| OS07G0584100 | 2.07 | Probable serine/threonine-protein kinase WNK5 |

| OS03G0762100 | 2.06 | Expressed protein |

| OS05G0195200 | 2.06 | Zinc finger CCCH domain-containing protein 35 |

| OS11G0521000 | 2.05 | GDSL-like lipase/acylhydrolase family protein |

| OS03G0326200 | 2.05 | Phospholipid-transporting ATPase 1 |

| OS07G0271000 | 2.03 | Putative GDP dissociation inhibitor |

| OS10G0392400 | 1.95 | ZIM motif family protein |

| OS06G0274800 | 1.86 | Class III peroxidase 77; putative peroxidase 49 |

| OS12G0154700 | 1.85 | Germin-like protein 12-1 |

| OS03G0281500 | 1.85 | Protein kinase |

| OS02G0686700 | 1.78 | Putative uncharacterized protein OJ1717_A09.39 |

Shown are the log2 fold change values (log2 FC) for genes commonly induced (>1.5) by ABA with adjusted p-values < 0.05.

Table 2.

ABA and Auxin downregulated genes specially changed in LRH under ABA treatment.

| Gene_ID | Log2 (FC) | Gene description |

|---|---|---|

| OS01G0329900 | -1.55 | Putative early nodule-specific protein ENOD8 |

| OS01G0668100 | -1.57 | Arabinogalactan protein-like |

| OS02G0640300 | -1.62 | Steroid membrane binding protein-like |

| OS10G0122600 | -1.63 | Similar to predicted protein |

| OS01G0195400 | -1.63 | Putative uncharacterized protein P0001B06.31 |

| OS12G0443500 | -1.65 | UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase 4 |

| OS09G0353700 | -1.71 | Similar to Leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase |

| OS09G0274900 | -1.72 | Putative uncharacterized protein OJ1031_C12.40 |

| OS01G0805900 | -1.73 | Tubulin beta-4 chain |

| OS02G0187800 | -1.77 | Cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase 2 |

| OS04G0491500 | -1.77 | TGF-beta receptor, type I/II extracellular region family protein |

| OS06G0680500 | -1.79 | Glutamate receptor |

| OS12G0225900 | -1.89 | NADP-dependent oxidoreductase P1 |

| OS11G0270000 | -1.89 | Crotonase, core domain containing protein |

| OS04G0438200 | -1.98 | Similar to H0315A08.10 protein |

| OS01G0770700 | -1.99 | Copper transporter 1 |

| OS11G0138900 | -2.02 | Alpha/beta hydrolase fold-3 domain containing protein |

| OS02G0684100 | -2.04 | Putative steroid sulfotransferase |

| OS03G0760500 | -2.05 | Cytochrome P450 family protein |

| OS03G0317300 | -2.06 | Eukaryotic aspartyl protease family protein |

| OS06G0592400 | -2.08 | Similar to cytosolic aldehyde dehydrogenase RF2C |

| OS02G0753000 | -2.12 | Probable trehalose-phosphate phosphatase 4 |

| OS05G0427900 | -2.12 | Similar to DnaJ-like protein |

| OS10G0130800 | -2.20 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| OS12G0260500 | -2.21 | Similar to oxidoreductase, short chain dehydrogenase/reductase family protein, expressed |

| OS03G0831400 | -2.22 | Expressed protein |

| OS11G0290600 | -2.24 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| OS10G0552300 | -2.35 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| OS04G0472200 | -2.36 | Similar to H0418A01.11 protein |

| OS04G0659200 | -2.37 | Hypothetical protein |

| OS01G0916100 | -2.50 | Similar to loricrin |

| OS10G0320100 | -2.50 | Flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase; flavonoid 3′-monooxygenase |

| OS10G0546100 | -2.54 | Pollen proteins Ole e I family protein |

| OS02G0574000 | -2.56 | Similar to monosaccharide transporter 1 |

| OS03G0699700 | -2.58 | Linoleate 9S-lipoxygenase 1 |

| OS11G0708100 | -2.64 | Similar to laccase-22 |

| OS01G0263000 | -2.65 | Peroxidase superfamily protein |

| OS02G0767300 | -2.76 | Putative flavonol synthase |

| OS05G0134800 | -2.82 | Class III peroxidase 67 |

| OS03G0143900 | -2.82 | Disease resistance-responsive family protein |

| OS02G0280200 | -2.92 | Similar to xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase protein 26 |

| OS01G0899700 | -2.93 | Putative extensin |

| OS06G0335900 | -2.93 | Putative Xet3 protein |

| OS07G0499500 | -3.00 | Putative peroxidase prx15 |

| OS05G0372900 | -3.06 | Putative uncharacterized protein |

| OS03G0368000 | -3.13 | Class III peroxidase 42; peroxidase family protein |

| OS08G0503000 | -3.23 | Hypothetical protein |

| OS07G0542900 | -3.29 | Putative phytocyanin |

| OS04G0674800 | -3.41 | Endoglucanase 13 |

| OS05G0382900 | -3.47 | Annexin |

| OS03G0608000 | -3.75 | Expressed protein |

| OS12G0163700 | -4.10 | Similar to Actin 7 |

| OS01G0370000 | -4.51 | Putative 12-oxophytodienoate reductase 9 |

| OS01G0550800 | -4.69 | Putative ZmEBE-1 protein |

| OS10G0109300 | -5.35 | Class III peroxidase 125 |

| OS01G0216000 | -8.26 | Putative esterase |

Shown are the log2 fold change values (log2 FC) for genes commonly repressed (< -1.5) by ABA with adjusted p-values < 0.05.

To identify root hair-specific genes, we also screened the promoter regions of the 113 genes co-regulated by ABA and auxin (2000 bp upstream of the start codon) for the RHE sequence “WHHDTGNNN(N)KCACGWH” (where W = A/T, H = A/T/C, D = G/T/A, K = G/T, and N = A/T/C/G), as previously described (Won et al., 2009). We found 69 RHEs in 51 genes, with 13 genes carrying two or more RHEs (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 5). Because we lack root hair-specific gene expression data, we predicted whether these genes are specifically expressed in epidermal cells by searching the rice microarray expression database (RiceXPro) (Supplementary Table 5). These results indicated that 35 out of the 51 genes containing the RHE are highly expressed in epidermal cells in rice root tips.

Table 3.

Distribution of RHE motif in the upregulated genes promoter between mock and ABA treatment in LRH.

| Epidermal expression | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence name | Strand | Start | End | p-value | Matched sequence | Log2 (FC) | Description | in root tip |

| Os11g0454200 | + | 1724 | 1739 | 7.25E-05 | TACGTGGCAGCAGGTT | inf | Dehydrin RAB 16B. | Yes |

| Os12g0455000 | - | 1560 | 1576 | 8.61E-05 | TCCTTGCATTGCAAGTC | 7.06262 | Conserved hypothetical protein. | Yes |

| Os04g0560100 | + | 1050 | 1065 | 5.94E-05 | ATTTTGTCTACACGAA | 3.98115 | Cytochrome P450 family protein. | Yes |

| Os07g0599300 | - | 173 | 188 | 1.67E-05 | TTTTTGCCAGCACGAG | 3.12285 | Conserved hypothetical protein. | Yes |

| Os08g0412800 | + | 1181 | 1196 | 5.90E-05 | ACTTTGTATACACGTA | 3.04954 | Protein of unknown function DUF1262 family protein. | Yes |

| Os10g0345100 | + | 1618 | 1634 | 3.40E-05 | TCCACGCGTCGCACGAC | 2.75364 | Multi antimicrobial extrusion protein MatE family protein. | Yes |

| Os07g0599600 | + | 1634 | 1650 | 2.89E-05 | TCTTTGTCATGCACGGC | 2.63352 | Early nodulin 75-like protein | Yes |

| Os07g0599600 | - | 753 | 769 | 8.05E-05 | ACAATGCGTGGGACGAA | 2.63352 | Early nodulin 75-like protein | Yes |

| Os03g0820300 | - | 882 | 897 | 5.41E-05 | TCCACGCACGCACGTA | 2.41894 | Similar to ZPT2-14. C2H2 transcript factor. | Yes |

| Os03g0820300 | + | 1926 | 1942 | 2.74E-05 | TCCTTGGCAAACACGTA | 2.41894 | Similar to ZPT2-14. C2H2 transcript factor. | Yes |

| Os07g0599500 | + | 1626 | 1642 | 3.99E-06 | TCCTTGTCATGCACGAT | 2.38247 | Conserved hypothetical protein. | Yes |

| Os12g0154900 | + | 387 | 403 | 7.35E-05 | CAATTGTGTTTCACGTA | 2.32817 | Similar to Germin-like protein precursor. | Yes |

| Os08g0137800 | - | 1227 | 1243 | 4.70E-06 | TCCTTGCCATTCACGAA | 2.25575 | Cupredoxin domain containing protein. | Yes |

| Os08g0137800 | - | 401 | 417 | 5.08E-05 | ATGTTGTTTTTCACGAT | 2.25575 | Cupredoxin domain containing protein. | Yes |

| Os07g0599700 | + | 357 | 373 | 6.37E-05 | TCCGCGTACAGCACGTA | 2.1417 | Similar to Surface protein PspC. | Yes |

| Os07g0584100 | + | 1043 | 1059 | 6.37E-05 | AACGCGGACTGCACGTT | 2.06878 | Similar to MAP kinase-like protein. | Yes |

| Os11g0521000 | - | 672 | 688 | 7.18E-05 | TCCTTGCCACGCATGTT | 2.05367 | Lipolytic enzyme, G-D-S-L family protein. | Yes |

| Os07g0271000 | + | 67 | 83 | 4.69E-05 | AAAGTGGGACGCTCGTC | 2.03135 | Similar to GDP dissociation inhibitor protein OsGDI1. | Yes |

| Os10g0392400 | + | 1507 | 1523 | 6.60E-05 | ACAGTGTGAGGCATGAC | 1.95131 | ZIM domain containing protein. | Yes |

| Os10g0392400 | + | 379 | 395 | 7.26E-05 | CATATGAAATGCACGTT | 1.95131 | ZIM domain containing protein. | Yes |

Discussion

This study provides several lines of evidence to demonstrate that in rice, ABA promotes root hair elongation by regulating auxin transport and biosynthesis in specific zones of the roots. First, exogenous ABA treatment enhances root hair elongation in rice root tip and inhibit ABA biosynthesis also repress the root hair elongation. It has been reported that low concentration (0.1 μM) of exogenous ABA can promote root elongation, but high concentrations (>0.5 μM) of ABA inhibits root elongation (Ghassemian et al., 2000; Rowe et al., 2016). We also found that 0.1 μM ABA inhibit root hair elongation, while 0.5 μM and 2 μM ABA enhanced rice root hair elongation. One explanation is that feedback regulation is a common regulatory mechanism for phytohormonal signaling, so different concentrations of ABA may reflect the different levels and results of feedback. Second, examination of transgenic lines overexpressing OsABIL2 or SAPK10, key components in rice ABA signaling showed that ABA-promoted root hair elongation is dependent on the major PYR/PP2C/SnRK signaling pathway. The ABA-insensitive OsABIL2-OE line showed decreased root hair elongation, and the ABA-hypersensitive line SAPK10-OE showed enhanced root hair elongation. Third, our analysis demonstrated that auxin acts downstream of ABA signaling to promote root hair elongation, which depends on the ABA-regulated polar auxin transport and local auxin biosynthesis. Our results consistent with previous studies that ABA and auxin functionally interact in roots (Rock and Sun, 2005; Xu et al., 2013). For example, ABA accumulation promotes auxin transport in root tips and enhance proton secretion for maintaining root growth under moderate water stress (Xu et al., 2013). Fourth, RNA-seq analysis and RHE screening identified 35 genes that respond strongly to ABA and auxin and may also be specifically expressed in root hair cells in the rice LRH zone. These genes may have important functions in regulating root hair elongation in rice. The last few years have been seen significant progress being made in uncovering the mechanisms that are involved in root hair development in rice, but major knowledge gaps still persist, especially compared with Arabidopsis, in which 138 genes related to root hair development have already been identified. While 8 genes that are involved in root hair development4 (Marzec et al., 2015). Our results provide 35 RHE-contained genes as candidate genes to regulate rice root hair development.

Polar auxin transport apparently plays a critical role in the ABA signaling-regulated root hair elongation in rice. Treatment with the auxin transport inhibitor NPA and staining of DR5-GUS lines demonstrated that ABA-promoted root hair elongation depends on polar auxin transport. ABA signaling is required for the ABA-regulated redistribution of auxin. In addition, auxin homeostasis in the root hair cell is critical for root hair elongation. In Arabidopsis, root hair-specific expression of auxin efflux carriers such as PINs (PIN1-4, PIN7, and PIN8) strongly suppresses root hair length, suggesting that auxin efflux carriers inhibit root hair elongation by depleting auxin in the root hair cell (Lee and Cho, 2006, 2013; Cho et al., 2007). Redistribution of auxin from its concentration maximum to epidermal cells requires the activity of PIN2, AUX1 and other carriers (Swarup et al., 2005; Ikeda et al., 2009). We showed that ABA not only significantly induces OsPINs and OsAUX1 mRNA levels, as confirmed by qRT-PCR and RNA-seq analysis, but also strongly induces the ectopic expression of OsPIN2 and OsPIN10a in the LRH zone. Because OsPIN2 and OsPIN10a are specifically expressed in the epidermal cells, indicating that ABA promotion of root hair elongation requires functional basipetal auxin transport. Consistent with our results, other workers have reported that under osmotic stress in an ABA-regulated manner enhanced PIN2 expression level in Arabidopsis root (Rowe et al., 2016).

Besides polar auxin transport, local auxin biosynthesis was also shown to modulate gradient-directed planar polarity in root hair development in Arabidopsis (Ikeda et al., 2009). We found that the ABA-enhanced accumulation of auxin in the LRH is also a consequence of the upregulation of local auxin biosynthesis in the Tip and LRH zones. First, ABA upregulates expression of almost all auxin biosynthetic genes in the Tip zone and upregulates OsAMI1, OsYUCCA4, and OsYUCCA1 in the LRH zone. Second, examination of negative feedback mechanisms showed that 10 of the 14 genes involved in the inactivation of IAA were upregulated in the Tip zone and 9 were also upregulated in the LRH zone, indicating that auxin biosynthesis was enhanced in the Tip and LRH zones. Third, direct measurement of the endogenous IAA levels in the Tip, LRH, and SRH zones of the rice roots directly demonstrated the ABA-enhanced auxin accumulation in rice roots. However, the IAA concentration in the Tip region was identical before and after ABA treatment. A reasonable explanation is that ABA-promoted basipetal auxin transport may lead to quick auxin flow into the LRH region. Alternatively, the drastic increase of the expression of genes encoding IAA inactivation enzymes in the Tip region promoted a rapid conversion of IAA to inactive forms.

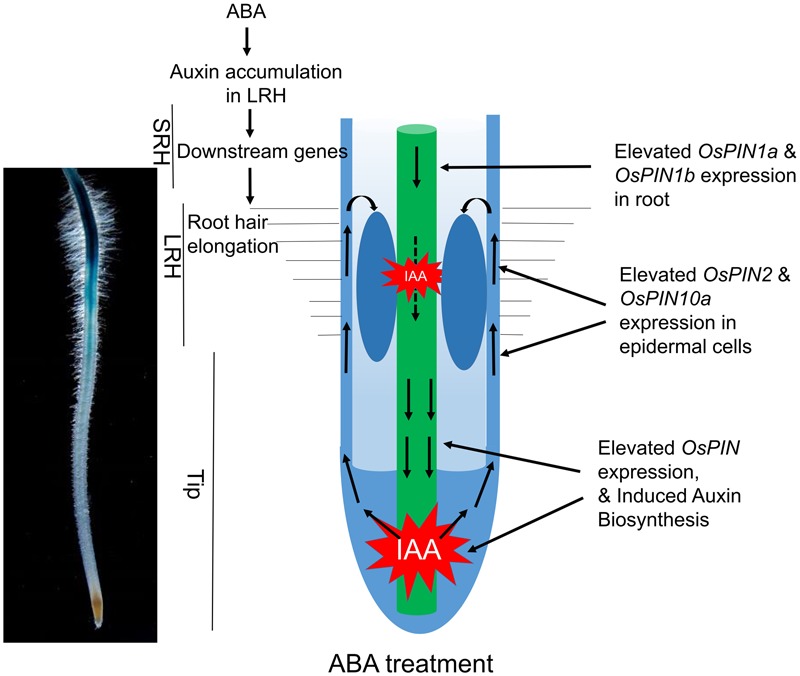

Our current data and previous discoveries suggested a model for the root hair elongation regulated by ABA in rice (Figure 7). ABA signaling promotes auxin biosynthesis in the Tip and LRH regions, and further enhanced the redistribution auxin through auxin basipetal transport to accumulate auxin in the LRH region. The high concentration of IAA activates downstream gene expression to promote root hair elongation. In the future, we plan to investigate the specific components in the ABA signaling pathway that directly regulate expression of genes involved in auxin transport and biosynthesis. In addition, the zone-specific genes identified in this study provide a great opportunity and resource to further understand how ABA regulates root hair elongation. In addition, the root hair region seems moving down during ABA treatment. We predicted this maybe caused by local auxin accumulation. According to our results, ABA promotes auxin acropetal and basipetal transport in rice tip and results in auxin local accumulation. As the applied ABA concentration increases, auxin may accumulate in the region much close to rice root tip, which lead to the move down of long root hair region. In addition, the inhibited root elongation by high concentration ABA may also result in the long root hair region closer to the root tip.

FIGURE 7.

A proposed model of how ABA promotes auxin biosynthesis and transport to regulate root hair elongation. ABA signaling promotes local auxin biosynthesis in the Tip and LRH regions, and regulates auxin basipetal transport, which result in auxin accumulation in the LRH region. The high concentration of auxin regulates downstream gene expression to promote root hair elongation.

Author Contributions

TW and XW conceived the research and planned the experiments; TW performed all of the experiments; CL provided SAPK10 and OsABIL2 transgenic plants; ZW performed the RNA-seq data analysis; YJ and HW helped to prepare material for RNA-seq; CM provided OsPIN-GUS transgenic plants; SS put forward improvement advise. TW and XW wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jianjun Jang of Fudan University, and Dr. Shiyong Sun and Changxi Yin of Huazhong Agricultural University for proofreading the text.

Abbreviations

- ABA

abscisic acid

- IAA

indole-3-acetic acid

- NAA

naphthaleneacetic acid

- NPA

1-N-naphthylphthalamic acid

- RAM

root apical meristem

- RHE

root hair regulatory element

- SEM

scanning electron microscopy

Funding. This work was supported by grants 91535104 and 31430046 (to XW), and 2016YFD0100403, 31271684 and 31540080 (to SS) of the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant 2012CB114304 of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (to XW and SS), and grants 2662015PY020 and 2014RC002 of Huazhong Agricultural University (to XW).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2017.01121/full#supplementary-material

References

- Bowles D., Lim E.-K., Poppenberger B., Vaistij F. E. (2006). Glycosyltransferases of lipophilic small molecules. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 57 567–597. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.-W., Yang Y.-W., Lur H.-S., Tsai Y.-G., Chang M.-C. (2006). A novel function of abscisic acid in the regulation of rice (Oryza sativa L.) root growth and development. Plant Cell Physiol. 47 1–13. 10.1093/pcp/pci216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X., Ruyter-Spira C., Bouwmeester H. (2013). The interaction between strigolactones and other plant hormones in the regulation of plant development. Front. Plant Sci. 4:199 10.3389/fpls.2013.00199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H.-T., Cosgrove D. J. (2002). Regulation of root hair initiation and expansin gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 14 3237–3253. 10.1105/tpc.006437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho M., Lee S. H., Cho H. T. (2007). P-glycoprotein4 displays auxin efflux transporter-like action in Arabidopsis root hair cells and tobacco cells. Plant Cell 19 3930–3943. 10.1105/tpc.107.054288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler S. R., Rodriguez P. L., Finkelstein R. R., Abrams S. R. (2010). Abscisic acid: emergence of a core signaling network. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 61 651–679. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Z., Zhou X., Ling Y., Zhang Z., Su Z. (2010). agriGO: a GO analysis toolkit for the agricultural community. Nucleic Acids Res. 38 W64–W70. 10.1093/nar/gkq310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Föhse D., Claassen N., Jungk A. (1991). Phosphorus efficiency of plants. Plant Soil 132 261–272. 10.1007/BF00010407 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J., Yu H., Li X., Xiao J., Wang S. (2011). Rice GH3 gene family: regulators of growth and development. Plant Signal. Behav. 6 570–574. 10.4161/psb.6.4.14947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghassemian M., Nambara E., Cutler S., Kawaide H., Kamiya Y., McCourt P. (2000). Regulation of abscisic acid signaling by the ethylene response pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 12 1117–1126. 10.1105/tpc.12.7.1117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy S., Jones D. L. (2000). Through form to function: root hair development and nutrient uptake. Trends Plant Sci. 5 56–60. 10.1016/S1360-1385(99)01551-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Hao Q., Li W., Yan C., Yan N., Yin P. (2014). Identification and characterization of ABA receptors in Oryza sativa. PLoS ONE 9:e95246 10.1371/journal.pone.0095246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda Y., Men S. Z., Fischer U., Stepanova A. N., Alonso J. M., Ljung K., et al. (2009). Local auxin biosynthesis modulates gradient-directed planar polarity in Arabidopsis. Nat. Cell Biol. 11 731–770. 10.1038/ncb1879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A. R., Kramer E. M., Knox K., Swarup R., Bennett M. J., Lazarus C. M., et al. (2009). Auxin transport through non-hair cells sustains root-hair development. Nat. Cell Biol. 11 78–84. 10.1038/ncb1815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno T., Kasai K., Ikejiri-Kanno Y., Wakasa K., Tozawa Y. (2004). In vitro reconstitution of rice anthranilate synthase: distinct functional properties of the alpha subunits OASA1 and OASA2. Plant Mol. Biol. 54 11–23. 10.1023/B:Plan.0000028729.79034.07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara H. (2016). Current aspects of auxin biosynthesis in plants. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 80 34–42. 10.1080/09168451.2015.1086259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr I. D., Bennett M. J. (2007). New insight into the biochemical mechanisms regulating auxin transport in plants. Biochem. J. 401 613–622. 10.1042/Bj20061411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Hwang H., Hong J.-W., Lee Y.-N., Ahn I. P., Yoon I. S., et al. (2012). A rice orthologue of the ABA receptor, OsPYL/RCAR5, is a positive regulator of the ABA signal transduction pathway in seed germination and early seedling growth. J. Exp. Bot. 63 1013–1024. 10.1093/jxb/err338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi Y., Murata M., Minami H., Yamamoto S., Kagaya Y., Hobo T., et al. (2005). Abscisic acid-activated SNRK2 protein kinases function in the gene-regulation pathway of ABA signal transduction by phosphorylating ABA response element-binding factors. Plant J. 44 939–949. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02583.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R. D.-W., Cho H.-T. (2013). Auxin, the organizer of the hormonal/environmental signals for root hair growth. Front. Plant Sci. 4:448 10.3389/fpls.2013.00448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. H., Cho H. T. (2006). PINOID positively regulates auxin efflux in Arabidopsis root hair cells and tobacco cells. Plant Cell 18 1604–1616. 10.1105/tpc.105.035972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Shen H., Wang T., Wang X. (2015). ABA regulates subcellular redistribution of OsABI-LIKE2, a negative regulator in ABA signaling, to control root architecture and drought resistance in Oryza sativa. Plant Cell Physiol. 56 2396–2408. 10.1093/pcp/pcv154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Li X., Xiao J., Wang S. (2012). A convenient method for simultaneous quantification of multiple phytohormones and metabolites: application in study of rice-bacterium interaction. Plant Methods 8:2 10.1186/1746-4811-8-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljung K., Hull A. K., Celenza J., Yamada M., Estelle M., Normanly J., et al. (2005). Sites and regulation of auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell 17 1090–1104. 10.1105/tpc.104.029272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Szostkiewicz I., Korte A., Moes D., Yang Y., Christmann A., et al. (2009). Regulators of PP2C phosphatase activity function as abscisic acid sensors. Science 324 1064–1068. 10.1126/science.1172408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzec M., Melzer M., Szarejko I. (2015). Root hair development in the grasses: what we already know and what we still need to know. Plant Physiol. 168 407–414. 10.1104/pp.15.00158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashiguchi K., Tanaka K., Sakai T., Sugawara S., Kawaide H., Natsume M., et al. (2011). The main auxin biosynthesis pathway in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 18512–18517. 10.1073/pnas.1108434108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masucci J. D., Schiefelbein J. W. (1994). The rhd6 mutation of Arabidopsis thaliana alters root-hair initiation through an auxin-and ethylene-associated process. Plant Physiol. 106 1335–1346. 10.1104/pp.106.4.1335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masucci J. D., Schiefelbein J. W. (1996). Hormones act downstream of TTG and GL2 to promote root hair outgrowth during epidermis development in the Arabidopsis root. Plant Cell 8 1505–1517. 10.1105/tpc.8.9.1505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. Y., Fung P., Nishimura N., Jensen D. R., Fujii H., Zhao Y., et al. (2009). Abscisic acid inhibits type 2C protein phosphatases via the PYR/PYL family of START proteins. Science 324 1068–1071. 10.1126/science.1173041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereg L., McMillan M. (2015). Scoping the potential uses of beneficial microorganisms for increasing productivity in cotton cropping systems. Soil Biol. Biochem. 80 349–358. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.10.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petersson S. V., Johansson A. I., Kowalczyk M., Makoveychuk A., Wang J. Y., Moritz T., et al. (2009). An auxin gradient and maximum in the Arabidopsis root apex shown by high-resolution cell-specific analysis of IAA distribution and synthesis. Plant Cell 21 1659–1668. 10.1105/tpc.109.066480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrasek J., Mravec J., Bouchard R., Blakeslee J. J., Abas M., Seifertova D., et al. (2006). PIN proteins perform a rate-limiting function in cellular auxin efflux. Science 312 914–918. 10.1126/science.1123542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitts R. J., Cernac A., Estelle M. (1998). Auxin and ethylene promote root hair elongation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 16 553–560. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00321.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A., Hosokawa S., Oono Y., Amakawa T., Goto N., Tsurumi S. (2002). Auxin and ethylene response interactions during Arabidopsis root hair development dissected by auxin influx modulators. Plant Physiol. 130 1908–1917. 10.1104/pp.010546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson A. E., Barea J.-M., McNeill A. M., Prigent-Combaret C. (2009). Acquisition of phosphorus and nitrogen in the rhizosphere and plant growth promotion by microorganisms. Plant Soil 321 305–339. 10.1007/s11104-009-9895-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robert H. S., Offringa R. (2008). Regulation of auxin transport polarity by AGC kinases. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11 495–502. 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock C. D., Sun X. (2005). Crosstalk between ABA and auxin signaling pathways in roots of Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Planta 222 98–106. 10.1007/s00425-005-1521-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe J. H., Topping J. F., Liu J., Lindsey K. (2016). Abscisic acid regulates root growth under osmotic stress conditions via an interacting hormonal network with cytokinin, ethylene and auxin. New Phytol. 211 225–239. 10.1111/nph.13882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y., Takehisa H., Kamatsuki K., Minami H., Namiki N., Ikawa H., et al. (2013). RiceXPro version 3.0: expanding the informatics resource for rice transcriptome. Nucleic Acids Res. 41 D1206–D1213. 10.1093/nar/gks1125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal E., Kushnir T., Mualem Y., Shani U. (2008). Water uptake and hydraulics of the root hair rhizosphere. Vadose Zone J. 7 1027–1034. 10.2136/vzj2007.0122 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shkolnik-Inbar D., Bar-Zvi D. (2010). ABI4 mediates abscisic acid and cytokinin inhibition of lateral root formation by reducing polar auxin transport in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 22 3560–3573. 10.1105/tpc.110.074641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soeno K., Goda H., Ishii T., Ogura T., Tachikawa T., Sasaki E., et al. (2010). Auxin biosynthesis inhibitors, identified by a genomics-based approach, provide insights into auxin biosynthesis. Plant Cell Physiol. 51 524–536. 10.1093/pcp/pcq032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarup K., Benkova E., Swarup R., Casimiro I., Peret B., Yang Y., et al. (2008). The auxin influx carrier LAX3 promotes lateral root emergence. Nat. Cell Biol. 10 946–954. 10.1038/ncb1754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarup R., Kramer E. M., Perry P., Knox K., Leyser H. M., Haseloff J., et al. (2005). Root gravitropism requires lateral root cap and epidermal cells for transport and response to a mobile auxin signal. Nat. Cell Biol. 7 1057–1065. 10.1038/ncb1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umezawa T., Sugiyama N., Mizoguchi M., Hayashi S., Myouga F., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., et al. (2009). Type 2C protein phosphatases directly regulate abscisic acid-activated protein kinases in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 17588–17593. 10.1073/pnas.0907095106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanstraelen M., Benková E. (2012). Hormonal interactions in the regulation of plant development. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 28 463–487. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101011-155741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. R., Hu H., Wang G. H., Li J., Chen J. Y., Wu P. (2009). Expression of PIN genes in rice (Oryza sativa L.): tissue specificity and regulation by hormones. Mol. Plant 2 823–831. 10.1093/mp/ssp023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Hua D., He J., Duan Y., Chen Z., Hong X., et al. (2011). Auxin response factor2 (ARF2) and its regulated homeodomain gene HB33 mediate abscisic acid response in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 7:e1002172 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewska J., Xu J., Seifertova D., Brewer P. B., Ruzicka K., Blilou I., et al. (2006). Polar PIN localization directs auxin flow in plants. Science 312 883–883. 10.1126/science.1121356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won S. K., Lee Y. J., Lee H. Y., Heo Y. K., Cho M., Cho H. T. (2009). cis-Element- and transcriptome-based screening of root hair-specific genes and their functional characterization in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 150 1459–1473. 10.1104/pp.109.140905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W. F., Jia L. G., Shi W. M., Liang J. S., Zhou F., Li Q. F., et al. (2013). Abscisic acid accumulation modulates auxin transport in the root tip to enhance proton secretion for maintaining root growth under moderate water stress. New Phytol. 197 139–150. 10.1111/nph.12004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y., Kamiya N., Kitano H., Matsuoka M. (2005). Expression of OsYUCCA gene and auxin biosynthesis in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 46 S47–S47. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y., Kamiya N., Morinaka Y., Matsuoka M., Sazuka T. (2007). Auxin biosynthesis by the YUCCA genes in rice. Plant Physiol. 143 1362–1371. 10.1104/pp.106.091561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka T., Endo T., Satoh S. (1998). Restoration of seed germination at supraoptimal temperatures by fluridone, an inhibitor of abscisic acid biosynthesis. Plant Cell Physiol. 39 307–312. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029371 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Cai Z., Wang X. (2009). The primary signaling outputs of brassinosteroids are regulated by abscisic acid signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 4543–4548. 10.1073/pnas.0900349106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H. M., Ma T. F., Wang X., Deng Y. T., Ma H. L., Zhang R. S., et al. (2015). OsAUX1 controls lateral root initiation in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Cell Environ. 38 2208–2222. 10.1111/pce.12467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. (2012). Auxin biosynthesis: a simple two-step pathway converts tryptophan to indole-3-acetic acid in plants. Mol. Plant 5 334–338. 10.1093/mp/ssr104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Christensen S. K., Fankhauser C., Cashman J. R., Cohen J. D., Weigel D., et al. (2001). A role for flavin monooxygenase-like enzymes in auxin biosynthesis. Science 291 306–309. 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z. G., Zhang Y. H., Liu X., Zhang X., Liu S. C., Yu X. W., et al. (2013). A role for a dioxygenase in auxin metabolism and reproductive development in rice. Dev. Cell 27 113–122. 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.