Abstract

Background

Enzyme-inducing anti-epileptic drugs (EI-AEDs) are not recommended for older adults with epilepsy. Quality Indicator for Epilepsy Treatment 9 (QUIET-9) states that new patients should not receive EI-AEDs as first line of treatment. In light of reported racial/ethnic disparities in epilepsy care, we investigated EI-AED use and QUIET-9 concordance across major racial/ethnic groups of Medicare beneficiaries.

Research Design

Retrospective analyses of 2008–2010 Medicare claims for a 5% random sample of beneficiaries ≥67 years old in 2009 augmented for minority representation. Logistic regressions examined QUIET-9 concordance differences by race/ethnicity adjusting for individual, socioeconomic, and geography factors.

Subjects

Epilepsy prevalent (≥1 ICD-9 345.× or ≥2 ICD-9 780.3×, ≥1 AED), and new (same as prevalent + no seizure/epilepsy events nor AEDs in 365 days before index event) cases.

Measures

Use of EI-AEDs and QUIET-9 concordance (no EI-AEDs for first two AEDs)

Results

Cases were 21% White, 58% African American (AA), 12% Hispanic, 6% Asian, 2% American Indian/Alaskan Native (AI/AN). About 65% of prevalent, 43.6% of new cases, used EI-AEDs. QUIET-9 concordance was found for 71% Asian, 65% White, 61% Hispanic, 57% AA, 55% AI/AN new cases: racial/ethnic differences were not significant in adjusted model. Beneficiaries without neurology care, in deductible drug benefit phase, or in high poverty areas were less likely to have QUIET-9 concordant care.

Conclusions

EI-AED use is high, and concordance with recommendations low, among all racial/ethnic groups of older adults with epilepsy. Potential socioeconomic disparities and drug coverage plans may affect treatment quality and opportunities to live well with epilepsy.

Keywords: Epilepsy, antiepileptic drugs, enzyme-inducing drugs, Medicare, administrative claims, Medicare Part D

Introduction

Epilepsy causes quality of life limitations similar to diabetes, cancer, heart disease, and arthritis.1 There has been considerable effort from federal and non-federal organizations to address this burden and assure that people live well with epilepsy, i.e., with “no seizures, no side effects.”2 As part of this effort, the 2007 Quality Indicators for Epilepsy Treatment (QUIET) were developed to guide physicians on how to care for older persons with epilepsy.3

Between 2001 and 2005, more than 250,000 Medicare beneficiaries 65 and older received care for epilepsy or seizures annually.4 Medical care and treatment to assure seizure control are crucial in achieving optimal quality of life.5 QUIET indicator 9 (QUIET-9) states that newly diagnosed older patients should not receive enzyme-inducing AEDs (EI-AEDs), i.e., phenytoin, carbamazepine, or phenobarbital, as first treatment for seizures given the current availability of better-tolerated AEDs.6, 7 EI-AEDs interact with many common lipid and non-lipid soluble drugs with important clinical implications for an older patient.7, 8 They are also associated with lower adherence and a higher risk of seizure recurrence compared to non-enzyme-inducing drugs.9, 10 Despite that, studies of selected groups of older adults who had private insurance, or were in managed care plans, or received care from the Department of Veteran Affairs (VA), showed that the use of EI-AED is pervasive with 50–70% being prescribed EI-AEDs.8, 9, 11, 12 However, a trend towards lower use was observed in the VA population.12 The use of EI-AEDs and the concordance with QUIET-9 in the larger population of older American adults with epilepsy and drug coverage through Medicare Part D is currently unknown. Medicare is the US federal health insurance program for people 65 years old or older, some Americans with disabilities or with end-stage renal disease. More than 90% of older Americans are Medicare beneficiaries: about half are enrolled in Part D plans for drug prescription coverage.13

Lower quality of care is of particular concern among minorities such as African Americans who have a higher prevalence of epilepsy.4 Healthcare disparities between African Americans and whites with epilepsy are not uncommon: they have been reported for surgical interventions,14, 15 specialized care,16 AED treatment,17 and AED adherence.10, 18 There is dearth of information on the quality of epilepsy care among other groups of Medicare beneficiaries. Hispanics were found to be less likely than whites to have access to specialized epilepsy care,19 and Asians/Pacific Islanders less likely to pursue surgical epilepsy treatment compared to whites.20 Moreover, Native American Medicare beneficiaries with epilepsy were less likely to receive neurology care compared to white beneficiaries.21 Lack of access to neurologists could negatively impact the quality of AED treatment and, possibly, the control of seizures.17

At present, data regarding AED use for the treatment of epilepsy in older Americans are limited, including data regarding the concordance of care with QUIET-9. This knowledge gap is especially pervasive in typically disadvantaged populations such as African Americans, Native Americans, and Hispanics. One objective of the current study was to investigate use of EI-AED in older adults with epilepsy of major racial/ethnic groups. In particular, we examined use among African American, Asians/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN), and white older Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Part D plans. Our second objective was to examine concordance with the QUIET-9 indicator for new cases of epilepsy among racially/ethnically diverse older adults. Lastly, we examined whether QUIET-9 concordance differences by race/ethnicity persisted after adjusting for various factors including patient-level factors such as age, comorbid conditions, or use of neurology care; socio-economic factors such as indicators of poverty; and regional indicators to account for the geographic variability in medical care. In addition, we accounted for the Part D benefit characteristics because the affordability of AEDs may vary depending on whether beneficiaries cover only part or all the cost of their prescription drugs.

Methods

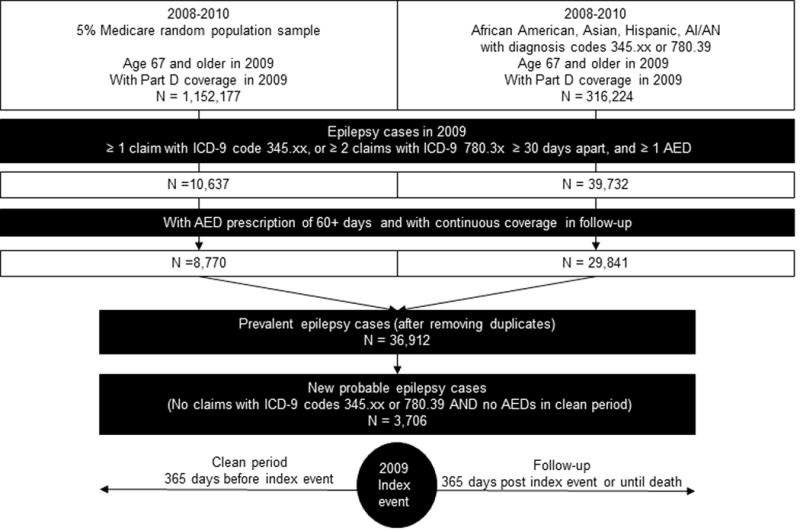

This study is a retrospective analysis of 2008–2010 administrative claims from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Data were obtained for a 5% random sample of the Medicare overall older population (Figure 1). To increase representation of minority groups among epilepsy cases, we also obtained data on all African American, Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, and AI/AN Medicare beneficiaries who had administrative claims for seizures and/or epilepsy (Figure 1). We restricted these populations to beneficiaries who were 67 years old or older and had Medicare Part D coverage in 2009 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Selection of analytic cases and study design

To identify prevalent cases of epilepsy we used the following claim-based epilepsy diagnosis: i) at least one claim (inpatient, outpatient or physician visit) with International Classification of Disease- version 9 (ICD-9) code 345.xx, or at least two claims with ICD-9 780.3x that were 30 days apart, and ii) at least one AED prescription of 60 days or more. Claim-based diagnoses similar to this were found to have a positive predictive value of 94% for detecting cases of epilepsy among older veterans,11 and 70%-88% in a managed care population.22 We identified the index event as first claim that defined this diagnosis. Among the identified cases, we included beneficiaries who had at least 12 months of follow-up from the index event, i.e., 12 months of Medicare Part A (hospital insurance), B (coverage for outpatient and physician visits), and D (prescription drug coverage), and no managed care plans, or had coverage until death if death occurred within the 12 month follow-up.

We identified all filled brand and generic AED prescriptions, and subdivided them into EI- and non-EI- AEDs. EI-AEDs were phenytoin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine, primidone, and the corresponding brand name drugs. We examined utilization of these AEDs by race/ethnic groups. Concordance of AED treatment with QUIET-9 was defined for new probable epilepsy cases which were cases with a period of 365 days before the index event with i) continuous coverage with Part A, B, and D, ii) no claims with ICD-9 codes for epilepsy or seizures, and iii) no prescriptions for AEDs (Figure 1). QUIET-9 indicates that “if newly diagnosed older patients are not on any AED therapy, they should not be started on EI-AEDs unless at least two other AEDs have been unsuccessful in stopping seizures or have intolerable side effects.” 3 We, thus, identified the first and second consecutive AEDs prescribed after the clean period and in the 12 month follow-up. If beneficiaries filled prescriptions for a brand name drug and subsequently for the generic correspondent (or vice versa), only one drug was counted. A beneficiary was defined as having QUIET-9 concordant care if the first and second prescribed drugs were non-EI AEDs.

Analysis

We obtained the frequency by race/ethnic group of EI-AED use and, among new cases, the frequency of QUIET-9 concordant care. Chi square tests were used to test differences across beneficiaries’ groups. In logistic regression, we examined whether differences by race/ethnicity in QUIET-9 concordant care for new cases were significant after adjusting for factors that we specified a–priori as potential confounders of this association. We controlled for: 1) individual factors: age, gender, number of comorbid conditions, and neurology visit close to diagnosis, i.e. at least one claim for a neurologist or neurosurgeon visit in the 30 days before to the 60 days after the index event; 2) socio-economic factors: being eligible for Part D Low Income Subsidy (LIS), ZIP code level poverty indicators, and Part D benefit phases defined for the drug prescribed right before the first observed AED prescription. In 2009–2010, these phases were, in order of occurrence, Deductible, Copayment/Coinsurance (beneficiaries pay a copayment or co-insurance for covered prescription drugs), Coverage Gap (donut hole: beneficiaries, depending on the plans, pay the full cost of prescription drugs), and Catastrophic Coverage (Medicare covers most of prescription drug cost); and 3) geography: US region of residence (Northeast, West, Midwest, and South). Comorbidities were identified in the one year before the index event using algorithms based on the Charlson Comorbidity score.23, 24 ZIP code level information on poverty was obtained from the 2010 Census. We created an indicator for high poverty corresponding to ZIP codes where >20% of households lived below 100% of the Federal Poverty Line.

Results

Among the 36,912 cases of epilepsy in 2009, 19.2% were White, 62.5% African American, 11.3% Hispanic, 5.0% Asian, and 2.0% AI/AN (Table 1). Moreover, 61.6% were female, 22.4% 85 years old and older, and 50.3% were from the southern US. A substantial proportion, 46.0%, had 4 or more comorbidities in the year before the epilepsy diagnosis, and only about 36% saw a neurologist close to diagnosis. Moreover, 82.0% were eligible for the Part D Low Income Subsidy (LIS). New cases had a similar distribution across racial/ethnic groups as all cases. They differed from prevalent cases in having 4 or more comorbidities (>50%) and seeing a neurologist (72.8%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Medicare beneficiaries with epilepsy, 2009

| Prevalent epilepsy cases | New epilepsy cases | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| N = 36,912 | N = 3,706 | |

| White | 19.2 | 18.0 |

| African American | 62.5 | 61.2 |

| Hispanic | 11.3 | 12.3 |

| Asian | 5.0 | 6.6 |

| AI/ANa | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Female | 61.6 | 64.9 |

| Age in 2009 | ||

| 67–74 | 41.5 | 34.9 |

| 75–84 | 36.1 | 37.3 |

| 85+ | 22.4 | 27.8 |

| Comorbid conditions | ||

| 0 | 8.3 | 3.7 |

| 1–3 | 45.7 | 41.0 |

| 4+ | 46.0 | 55.3 |

| Neurologist close to diagnosis | 36.3 | 72.8 |

| LISb eligible | 82.0 | 77.2 |

| Medicare Part D Phasec | ||

| Deductible | 19.3 | 17.0 |

| Copay/coinsurance | 59.2 | 60.4 |

| Coverage gap (donut hole) | 13.8 | 15.2 |

| Catastrophic | 5.1 | 4.2 |

| No Phase | 2.6 | 3.3 |

| Region of residenced | ||

| South | 50.2 | 49.2 |

| West | 13.3 | 15.1 |

| Mid West | 17.7 | 17.0 |

| North East | 18.7 | 18.8 |

AI/AN= American Indian/Alaskan Native;

LIS = Part D Low Income Subsidy;

2009 Part D benefit phase for the drug before the first AED for epilepsy groups;

South = DE, DC, FL, GA, MD, NC, SC, VA, WV, AL, KY, MS, TN, AR, LA, OK, TX; West = AZ, CO, ID, NM, MT, UT, NV, WY, AK, CA, HI, OR, WA; Midwest = IN, IL, MI, OH, WI, IA, NE, KS, ND, MN, SD, MO; Northeast = CT, ME, MA, NH, RI, VT, NJ, NY, PA

About 65% of all prevalent cases used an EI-AED in the follow-up period (Table 2), ranging from 56.3% of Asians to 71% of AI/ANs. This proportion was higher among those who did not have comorbid conditions (76.7%), did not have a neurologist visit close to the index event (70.7%), or were in the Part D deductible phase (76.0%). Among the new cases, 43.6% had one or more EI-AED prescriptions, from 31.4% of Asians to 47.9% of AI/ANs. Use was higher among beneficiaries who were male (47.0%), age 67–74 (47.2%), had no comorbid conditions (47.8%), had no neurologist visits (55.5%), were in the deductible phase (52.5%), resided in the South (47.3%), and lived in high poverty ZIP codes (47.9%).

Table 2.

Proportion of beneficiaries using enzyme-inducing anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs)a and with QUIET 9 concordant treatment, Medicare 2009

| Using enzyme-inducing AEDs | With QUIET-9 concordant treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Prevalent cases | New cases | New cases | P | |

|

| ||||

| N = 36,912 | N = 3,706 | N = 3,706 | ||

| Overall | 64.9 | 43.6 | 59.8 | – |

|

| ||||

| White | 61.6 | 38.0 | 65.4 | <.0001 |

| African American | 66.2 | 46.4 | 56.8 | |

| Hispanic | 66.1 | 43.4 | 61.0 | |

| Asian | 56.3 | 31.4 | 71.0 | |

| AI/ANb | 71.0 | 47.9 | 54.8 | |

|

| ||||

| Female | 62.0 | 41.7 | 61.9 | 0.0004 |

| Male | 69.6 | 47.0 | 55.9 | |

|

| ||||

| Age in 2009 | 0.009 | |||

| 67–74 | 67.9 | 47.2 | 56.8 | |

| 75–84 | 64.0 | 43.1 | 60.0 | |

| 85+ | 61.0 | 39.6 | 63.1 | |

|

| ||||

| Comorbid conditions | 0.37 | |||

| 0 | 76.7 | 47.8 | 55.1 | |

| 1–3 | 67.1 | 44.7 | 59.2 | |

| 4+ | 60.6 | 42.4 | 60.5 | |

|

| ||||

| Neurologist index eventc | 54.8 | 39.1 | 64.3 | <.0001 |

| No neurologist close to index event | 70.7 | 55.5 | 47.7 | |

|

| ||||

| LISc eligible | 65.7 | 44.8 | 58.2 | 0.0002 |

| Non-LIS eligible | 61.3 | 39.3 | 65.2 | |

|

| ||||

| Medicare Part D Phased | <.0001 | |||

| Deductible | 76.0 | 52.5 | 50.8 | |

| Copay/coinsurance | 65.1 | 43.1 | 60.4 | |

| Coverage gap (donut hole) | 53.6 | 40.1 | 63.4 | |

| Catastrophic coverage | 50.9 | 36.1 | 65.2 | |

| No phase | 57.8 | 31.4 | 71.1 | |

|

| ||||

| Region of residence | <.0001 | |||

| South | 67.5 | 47.3 | 55.7 | |

| West | 64.4 | 41.8 | 62.2 | |

| Midwest | 64.0 | 43.1 | 60.2 | |

| Northeast | 59.2 | 35.8 | 68.1 | |

|

| ||||

| High Poverty | 67.3 | 47.9 | 55.5 | <.0001 |

| Not high Poverty | 62.9 | 39.9 | 63.3 | |

Enzyme-inducing AEDs = phenytoin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine, primidone, and corresponding brand name drugs;

AI/AN= American Indian/Alaskan Native;

Neurologist visit from 30 days before to 60 days post index event;

LIS = Part D Low Income Subsidy;

2009 Part D benefit phase for the prescription before the first observed AED prescription

Of the new cases, 59.8% had QUIET-9 concordant treatment, from 71% for Asians to 54.8% of AI/ANs (p<0.0001, unadjusted analyses) (Table 2). In adjusted analyses (Table 3), differences between white beneficiaries and other race/ethnic groups were not significant: odds ratios and confidence intervals (CI) compared to White beneficiaries were: for African Americans 0.81, CI 0.66–1.00, for Hispanics 0.92, CI 0.70–1.12, for Asians 1.39, CI 0.99–1.96, and for AI/AN 0.93, CI 0.55–1.57, (Table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic regression on likelihood of QUIET 9 concordant care among new epilepsy cases (N = 3,706), 2009

| OR (CI) | |

|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity (ref White) | |

| African American | 0.81 (0.66–1.00) |

| Hispanic | 0.92 (0.70–1.21) |

| Asian | 1.39 (0.99–1.96) |

| AI/ANa | 0.93 (0.55–1.57) |

| Gender (ref Male) | |

| Female | 1.20 (1.04–1.40) |

| Age in 2009 (ref 67–74) | |

| 75–84 | 1.04 (0.88–1.22) |

| 85+ | 1.19 (0.99–1.42) |

| Comorbid conditions (ref None) | |

| 1–3 | 0.92 (0.63–1.35) |

| 4+ | 0.96 (0.66–1.41) |

| Seen neurologist close to the index event (ref No neurologist) | 1.83 (1.56–2.13) |

| LISb eligible (ref Not eligible) | 0.91 (0.75–1.10) |

| Part D Coverage Phasec (ref Deductible) | |

| Copay/coinsurance | 1.41 (1.17–1.71) |

| Coverage gap (donut hole) | 1.57 (1.23–2.00) |

| Catastrophic coverage | 1.73 (1.18–2.53) |

| No phase | 2.15 (1.36–3.41) |

| Region of residence (ref Northeast) | |

| Other than northeast | 0.70 (0.58–0.84) |

| ZIP code area | |

| High Povertyd | 0.85 (0.73–0.98) |

|

| |

| Number of observations used | 3562 |

AI/AN= American Indian/Alaskan Native;

Low Income Subsidy;

Coverage phase for the drug prescribed before the first observed AED;

20% or more households below the Federal Poverty Line

Some differences were noticed across sociodemographic factors (Table 3). Beneficiaries who were male, were in the Part D deductible phase, did not reside in the Northeast, or lived in high poverty ZIP codes were less likely to have QUIET-9 concordant care than their counterparts (Table 3). Beneficiaries who saw a neurologist during the follow-up were more likely to have QUIET-9 concordant care than those who did not see a neurologist (Table 3).

Discussion

The current consensus on the treatment of older adults with epilepsy is to avoid EI-AEDs unless other drugs are tried and found to not control seizures or to give intolerable side effects (QUIET-9 indicator). We find that two out of three Medicare beneficiaries with epilepsy were still treated with EI-AEDs in 2009. Among those who may be considered new cases of epilepsy (defined as having no seizures or AED in the previous 1-year), only about 60% received treatment concordant with the QUIET-9 indicator according to which newly diagnosed older patients should not receive EI-AEDs as first line of treatment for seizures. Differences across race/ethnic groups in QUIET-9 concordant care, especially difference for African and AI/ANs compared to Whites, were significant only in analyses that did not account for socio-economic factors.

Among older Americans with epilepsy, the utilization of EI-AEDs is still common. Such utilization, although lower, is still surprisingly high among those who may be starting AED treatment for the first time. The consequences for seizure control or side effects in this Medicare population are currently unknown and deserve scrutiny. Moreover, the reasons why physicians may start older patients on such drugs also deserve attention. Many factors influence the AED choice including better familiarity with some AEDs and epilepsy syndromes.5 As this familiarity may depend on the level of training,5 it is not surprising to find that the use of EI-AEDs was lower and concordance with QUIET-9 was higher among cases who had neurology encounters. Others have also shown how the setting of care may influence epilepsy treatment.17 However, even among new probable epilepsy cases with neurology care, more than a third did not have drug treatment concordant with QUIET-9. It may be that an EI-AED was prescribed by non-neurologists and later changed by the neurologist. In support of this explanation, we found that beneficiaries who saw neurologists were more likely to fill prescriptions for more than one AED in the follow-up period compared to those who did not see a neurologist (26.6% versus 18.3%). Moreover, comparing new cases with and without neurologic care close to the index event, we found that those who do not see a neurologist were more likely to be African American, eligible for LIS, reside in the southern US, and to live in high poverty ZIP code areas. Thus, while our analysis adjusted for these factors, there may be other unmeasured underlying access to care issues that may explain why they do not receive neurologic care or treatment concordant with the QUIET-9 indicator. However, it is also plausible that neurologists believe older drugs like phenytoin to be efficacious and to have other useful properties.12

Disparities in epilepsy care have been reported for several treatment options.10, 14, 17–20, 25. In our study, some racial disparities were evident in the concordance of AED treatment to the QUIET-9 indicator, in particular for African Americans and AI/ANs. The latter group was previously found to be less likely to receive neurological care.21 Similarly in our study, only about half of new AI/AN epilepsy cases had one or more encounters with neurologists in the few months around the diagnosis period. This may explain the lower frequency of QUIET-9 concordant care among probable new AI/AN cases, as having neurologist visits was associated with a higher likelihood of such care. The disparity between African Americans and AI/ANs and whites was not significant in our model adjusted for a number of potential confounders including socioeconomic factors such as area level poverty indicators. EI-AEDs are older drugs that are less expensive than newer non-EI drugs: therefore, it was not surprising that poverty was associated with a lower likelihood of Quiet-9 concordant care.

Our results on the drug plan benefit phase are interesting. The association of higher cost-sharing on the utilization of drugs and adherence to treatment are well known.26–34 In line with this literature, we found that being in the deductible phase, when beneficiaries pay for prescriptions out of their own pocket, was associated with a lower likelihood of having QUIET-9 concordant care compared to being in cost-sharing Part D phases or in the Coverage Gap (donut hole), another non-cost-sharing phase in which prescriptions are paid out of pocket by beneficiaries after having reached a pre-determined level of drug expenditures. In the Coverage Gap, however, beneficiaries may have alternative drug plans, or they may have reached this benefit phase because they used more expensive AEDs. Research also shows that drug choices are sensitive to whether patients expect to reach annual limits on drug coverage.32 Here, once the Coverage Gap is reached, the AED choice is not affected by the fact that beneficiaries are responsible for its cost, while this choice may be more sensitive during the deductible phase. These results, together with the significant findings about poverty indicators, bring to light the implications of drug coverage restrictions and low socioeconomic status on appropriate AED treatment, and ultimately on epilepsy outcomes. Further research is warranted on the outcomes in low socioeconomic populations with epilepsy, and on how to assure affordable and effective epilepsy care.

Some limitations of our study are noted. First, there are limitations associated with studying health care utilization based on claims data. Epilepsy cases that may have not needed medical attention or follow-up may be missed when using claims data. Even when care is received and claims are available, claim-based epilepsy identification algorithms have limitations. However, we used a method more conservative than published algorithms that have positive predictive values greater than 90%. Second, the identification of new cases is limited. Cases may have had claims for epilepsy or seizures in the years before the one we used as the clean period. In a previous study that used a similar epilepsy definition except for the requirement to be on AEDs and for a clean period of two years, the estimated epilepsy incidence was reduced by 10% if such clean period was increased by one year.4Therefore, some of what we consider new cases may have tried non-EI-AEDs before the clean period and, thus, be misclassified as not having QUIET 9 concordant care in 2009. If this is the case, we have underestimated the proportion of new cases with concordant treatment. Furthermore, some cases may not have been classified as new cases because they used AEDs (e.g., gabapentin) in the year before the index event, but for reasons other than epilepsy. Among cases who did not have claims for seizure or epilepsy diagnosis in the year before the index event and who either had no AEDs or were on AEDs that may have been prescribed for reasons other than epilepsy, we found that only 28% used EI-AEDs in 2009, and 75% had treatment concordant with QUIET 9. Third, there is a possibility that Part D data are incomplete, for example due to low-cost programs for generic drugs such as $4 30-day prescriptions at Walmart or other such stores. Recent studies, however, found that only a small proportion of prescriptions (about 6%) are not adjudicated in Part D,35 and that the validity of Part D data is not compromised by the existence of low cost programs for generic drugs.36 Moreover, Pauly et al. found that only 8% of prescriptions available for low cost programs were purchased through such program: this figure was lower for anticonvulsants that include AEDs.37 In addition, the authors found no difference by race in users of low cost programs. Fourth, we restricted to a population who had Medicare coverage for a one year period or until death. When we applied this restriction, we retained about 84% of the white and about 75% of the minority population. Considering the results on poverty and Part D coverage found in this study, the excluded population may be less likely to have QUIET-9 concordant care, and thus, we may have overestimated the proportion of new cases with QUIET-9 concordant care especially among minorities. Fifth, results may not be generalizable to the larger Medicare population as we restricted to a population with fee for service Medicare and on Part D. Other Part D beneficiaries may be on managed care plans for which administrative claims are not available and for whom we could not have determined epilepsy status. Moreover, because of our research question, our cohort over-represented minority groups compared to a random sample of Medicare beneficiaries meeting similar inclusion criteria.38

Despite its limitations, this study is one of the largest epilepsy investigations to focus on older minorities with epilepsy in the US. This large cohort allowed us to examine AED utilization and concordance with current consensus on epilepsy treatment among older Americans of several racial/ethnic groups who received care for epilepsy or seizures in 2009. It is a first glance at AED utilization in this population, and at whether treatment is in line with what is deemed acceptable to minimize the occurrence of seizures and side effects. While no significant racial/ethnic disparities in AED treatment were found, potential socioeconomic disparities exist that highlight the need to monitor epilepsy care in older Americans who may have a lower opportunity to live well with epilepsy. Further research should also investigate the implications on epilepsy outcomes of receiving care that is concordant (or not) with the current understanding of optimal treatment for older Americans with epilepsy.

Acknowledgments

Authors are grateful to Aquila Brown-Galvan, Nancy Cohen, Kay Clements for administrative support, medical coding, and clinical input.

Funding

The authors are grateful for support from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (1R01NS080898-01). The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data, and preparation, review or approval of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures:

Dr. Szaflarski received funding from UCB Biosciences, Compumedics Neuroscan Inc., SAGE Therapeutics Inc.; had consulting activity for SAGE Therapeutics Inc., Biomedical Systems Inc., Elite Medical Experts LLC

Dr. Faught has received research support from Brain Sentinel, Eisai, and UCB Pharma, has served on Data Monitoring Boards for Eisai, Lundbeck, SAGE, and SK Life Science, and has received consultation fees from Aprecia, Supernus, Sunovion, and UCB Pharma

Drs. Pisu, Richman, Piper, Martin, Funkhouser, Mr. Dai, and Ms. Juarez, report nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Theodore WH, Spencer SS, Wiebe S, et al. Epilepsy in North America: a report prepared under the auspices of the global campaign against epilepsy, the International Bureau for Epilepsy, the International League Against Epilepsy, and the World Health Organization. Epilepsia. 2006;47:1700–1722. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) Epilepsy Research Benchmarks [online] 2007 Accessed January 30. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pugh MJ, Berlowitz DR, Montouris G, et al. What constitutes high quality of care for adults with epilepsy? Neurology. 2007;69:2020–2027. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000291947.29643.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faught E, Richman J, Martin R, et al. Incidence and prevalence of epilepsy among older US. Medicare beneficiaries Neurology. 2012;78:448–453. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182477edc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szaflarski JP, Rackley AY, Lindsell CJ, Szaflarski M, Yates SL. Seizure control in patients with epilepsy: the physician vs. medication factors BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:264. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mintzer S, Mattson RT. Should enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs be considered first-line agents? Epilepsia. 2009;50(Suppl 8):42–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brodie MJ, Mintzer S, Pack AM, Gidal BE, Vecht CJ, Schmidt D. Enzyme induction with antiepileptic drugs: cause for concern? Epilepsia. 2013;54:11–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gidal BE, French JA, Grossman P, Le Teuff G. Assessment of potential drug interactions in patients with epilepsy: impact of age and sex. Neurology. 2009;72:419–425. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000341789.77291.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ettinger AB, Manjunath R, Candrilli SD, Davis KL. Prevalence and cost of nonadherence to antiepileptic drugs in elderly patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;14:324–329. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeber JE, Copeland LA, Pugh MJ. Variation in antiepileptic drug adherence among older patients with new-onset epilepsy. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44:1896–1904. doi: 10.1345/aph.1P385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pugh MJ, Van Cott AC, Cramer JA, et al. Trends in antiepileptic drug prescribing for older patients with new-onset epilepsy: 2000–2004. Neurology. 2008;70:2171–2178. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000313157.15089.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pugh MJ, Tabares J, Finley E, Bollinger M, Tortorice K, Vancott AC. Changes in antiepileptic drug choice for older veterans with new-onset epilepsy: 2002 to 2006. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:955–956. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse Medicare Tables Reports. https://www.ccwdata.org/web/guest/medicare-tables-reports [online].

- 14.Szaflarski M, Szaflarski JP, Privitera MD, Ficker DM, Horner RD. Racial/ethnic disparities in the treatment of epilepsy: what do we know? What do we need to know? Epilepsy Behav. 2006;9:243–264. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burneo JG, Jette N, Theodore W, et al. Disparities in epilepsy: report of a systematic review by the North American Commission of the International League Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2009;50:2285–2295. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02282.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schiltz NK, Koroukian SM, Singer ME, Love TE, Kaiboriboon K. Disparities in access to specialized epilepsy care. Epilepsy Res. 2013;107:172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hope OA, Zeber JE, Kressin NR, et al. New-onset geriatric epilepsy care: Race, setting of diagnosis, and choice of antiepileptic drug. Epilepsia. 2009;50:1085–1093. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faught RE, Weiner JR, Guerin A, Cunnington MC, Duh MS. Impact of nonadherence to antiepileptic drugs on health care utilization and costs: findings from the RANSOM study. Epilepsia. 2009;50:501–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Betjemann JP, Thompson AC, Santos-Sanchez C, Garcia PA, Ivey SL. Distinguishing language and race disparities in epilepsy surgery. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;28:444–449. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sim Y, Nokes B, Byreddy S, Chong J, Coull BM, Labiner DM. Healthcare utilization of patients with epilepsy in Yuma County, Arizona: do disparities exist? Epilepsy Behav. 2014;31:307–311. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pisu M, Richman JS, Martin RC, et al. Diagnostic tests and neurology care for Medicare beneficiaries with seizures: differences across racial groups. Med Care. 2012;50:730–736. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31824ebdc4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holden EW, Grossman E, Nguyen HT, et al. Developing a computer algorithm to identify epilepsy cases in managed care organizations. Dis Manag. 2005;8:1–14. doi: 10.1089/dis.2005.8.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis JG. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative data: differing perspectives. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:1075–1079. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90103-8. discussion 1081–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burneo JG, Black L, Knowlton RC, Faught E, Morawetz R, Kuzniecky RI. Racial disparities in the use of surgical treatment for intractable temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. 2005;64:50–54. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000150829.89586.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chernew M, Gibson TB, Yu-Isenberg K, Sokol MC, Rosen AB, Fendrick AM. Effects of increased patient cost sharing on socioeconomic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1131–1136. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0614-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gibson TB, Ozminkowski RJ, Goetzel RZ. The effects of prescription drug cost sharing: a review of the evidence. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:730–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gibson TB, Song X, Alemayehu B, et al. Cost sharing, adherence, and health outcomes in patients with diabetes. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16:589–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldman DP, Joyce GF, Zheng Y. Prescription drug cost sharing: associations with medication and medical utilization and spending and health. JAMA. 2007;298:61–69. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Solomon MD, Goldman DP, Joyce GF, Escarce JJ. Cost sharing and the initiation of drug therapy for the chronically ill. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:740–748. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.62. discussion 748–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chernew ME, Shah MR, Wegh A, et al. Impact of decreasing copayments on medication adherence within a disease management environment. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:103–112. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kephart G, Skedgel C, Sketris I, Grootendorst P, Hoar J. Effect of copayments on drug use in the presence of annual payment limits. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13:328–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sinnott SJ, Buckley C, O’Riordan D, Bradley C, Whelton H. The effect of copayments for prescriptions on adherence to prescription medicines in publicly insured populations; a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64914. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stroupe KT, Smith BM, Lee TA, et al. Effect of increased copayments on pharmacy use in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Med Care. 2007;45:1090–1097. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3180ca95be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberto PN, Stuart B. Out-of-plan medication in Medicare Part D. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20:743–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou L, Stearns SC, Thudium EM, Alburikan KA, Rodgers JE. Assessing Medicare Part D claim completeness using medication self-reports: the role of veteran status and Generic Drug Discount Programs. Med Care. 2015;53:463–470. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pauly NJ, Talbert JC, Brown J. Low-Cost Generic Program Use by Medicare Beneficiaries: Implications for Medication Exposure Misclassification in Administrative Claims Data. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22:741–751. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.6.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Piper K, Richman J, Faught E, et al. Adherence to antiepileptic drugs among diverse older Americans on Part D Medicare. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;66:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]