ABSTRACT

The HIV-1 accessory protein Vif is essential for viral replication by counteracting the host restriction factor APOBEC3G (A3G), and balanced levels of both proteins are required for efficient viral replication. Noncoding exons 2/2b contain the Vif start codon between their alternatively used splice donors 2 and 2b (D2 and D2b). For vif mRNA, intron 1 must be removed while intron 2 must be retained. Thus, splice acceptor 1 (A1) must be activated by U1 snRNP binding to either D2 or D2b, while splicing at D2 or D2b must be prevented. Here, we unravel the complex interactions between previously known and novel components of the splicing regulatory network regulating HIV-1 exon 2/2b inclusion in viral mRNAs. In particular, using RNA pulldown experiments and mass spectrometry analysis, we found members of the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoparticle (hnRNP) A/B family binding to a novel splicing regulatory element (SRE), the exonic splicing silencer ESS2b, and the splicing regulatory proteins Tra2/SRSF10 binding to the nearby exonic splicing enhancer ESE2b. Using a minigene reporter, we performed bioinformatics HEXplorer-guided mutational analysis to narrow down SRE motifs affecting splice site selection between D2 and D2b. Eventually, the impacts of these SREs on the viral splicing pattern and protein expression were exhaustively analyzed in viral particle production and replication experiments. Masking of these protein binding sites by use of locked nucleic acids (LNAs) impaired Vif expression and viral replication.

IMPORTANCE Based on our results, we propose a model in which a dense network of SREs regulates vif mRNA and protein expression, crucial to maintain viral replication within host cells with varying A3G levels and at different stages of infection. This regulation is maintained by several serine/arginine-rich splicing factors (SRSF) and hnRNPs binding to those elements. Targeting this cluster of SREs with LNAs may lead to the development of novel effective therapeutic strategies.

KEYWORDS: HEXplorer score, exon recognition, host restriction factor, human immunodeficiency virus, pre-mRNA processing, splicing regulatory elements

INTRODUCTION

During long terminal repeat (LTR)-driven transcription, over 50 mRNA isoforms emerge by alternative splicing of the HIV-1 precursor mRNA (1, 2). According to their distinct sizes, mRNA isoforms can be divided into three different classes: 2-kb mRNAs (intronless), encoding Tat, Rev, and Nef; intron-containing 4-kb mRNAs, encoding Vif, Vpr, Vpu, and Env; and 9-kb unspliced mRNAs, encoding Gag and Gag-Pol (3). Viral gene expression follows a strict chronological order (4–6). In the early phase, only intronless mRNAs are transported out of the nucleus and translated, whereas intron-containing 4-kb and 9-kb mRNAs depend on the accumulation of Rev protein, which facilitates their export into the cytoplasm in the later phase.

Primarily responsible for the vast amount of mRNA isoforms are four splice donor sites (D1 to D4), eight splice acceptor sites (A1 to A7, including the alternative splice acceptors A4 a, b, and c), and several only rarely used sites, like splice donor 2b (D2b) (1–3). Their recognition depends on intrinsic strength, as well as cis-acting splicing regulatory elements (SREs) bound by, e.g., serine/arginine-rich (SR) or heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoparticles (hnRNPs) (7).

Splicing itself is a highly regulated process controlled by several components of the spliceosomal complex. It starts with U1 small nuclear ribonucleic particle (snRNP) binding to the splice donor, followed by U2 snRNP binding to the branch point sequence of the upstream splice acceptor (8). U1 and U2 snRNPs pair in a process named exon definition (9), which is later transformed into an intron definition process (10, 11) in which U1 and U2 snRNPs couple across the intron and thereby initiate the splicing reaction. SR or hnRNPs can support U1 snRNP binding to a splice donor, depending on their exonic or intronic position (12).

Up to this time, many SREs have been identified within the pre-mRNA of HIV-1 (Fig. 1A). Only recently, five novel SREs could be identified using the HEXplorer algorithm (13). This algorithm reflects potentially enhancing and silencing properties of hexamers in the neighborhood of a splice donor by calculating the frequency of hexamer occurrence within introns versus exons. HEXplorer score (HZEI) profiles along sequences depict exonic enhancing regions as positive and silencing regions as negative values. Furthermore, HEXplorer score differences (ΔHZEI) between wild-type (WT) and mutant sequences quantitatively reflect the mutation effect on splice-enhancing/silencing properties. Any disruption of a splice site or an SRE can lead to a profound weakening of viral replication (14). Exclusively within HIV-1 exons 2 and 2b, six different SREs have already been described (Fig. 1B). Within exon 2, serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 1 (SRSF1)-dependent exonic splicing enhancers (ESEs) M1 and M2 (15), as well as the SRSF4-dependent ESE-Vif (16), have been shown to activate D2, whereas two G runs suppress exon 2/2b inclusion (16, 17). Furthermore, a novel HEXplorer-identified SRE within exon 2b, ESE2b (previously called ESE5005–5032), was shown to activate downstream splice donor usage in minigene analysis (13).

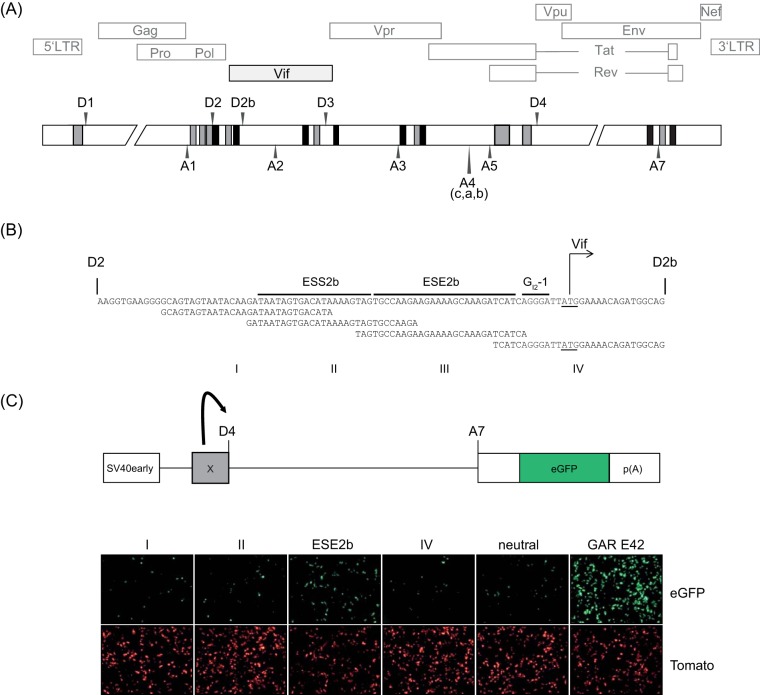

FIG 1.

Analysis of SREs in HIV-1 exon 2/2b. (A) Black (silencer) and gray (enhancer) bars represent published SREs. Splice donor sites (D1 to D4), splice acceptor sites (A1 to A7), and protein ORFs are shown. (B) SREs within exon 2/2b and definition of parts I to IV. The translational start codon for Vif is underlined. (C) Fluorescence microscopy analysis of fragments I to IV. (Top) Schematic overview of the single-intron eGFP splicing reporter. Any of sequences I, II, III (ESE2b), IV, neutral (CCAAACAA)5×, and GAR E42 was inserted upstream of D4. (Bottom) HeLa cells were transiently transfected with 1 μg of each construct, together with 1 μg of pCL-dTOM, to monitor transfection efficiency. Twenty-four hours after transfection, fluorescence microscopy was carried out.

In addition to splice acceptor A1 recognition and removal of the most 5′-proximal intron, use of the downstream splice donor must be prevented to result in the formation of vif mRNAs. Downstream splice donor sites D2 and D2b, however, have to be recognized by U1 snRNP to activate A1 but rendered splicing incompetent to maintain the vif open reading frame (ORF), whose start codon lies within the downstream intron of D2 (17).

Vif is a low-abundance, 23-kDa small protein that is incorporated into newly assembling virions. Vif counteracts the host restriction factor APOBEC3G (apolipoprotein B mRNA-editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like 3G) (A3G) (18), which is also encapsidated into virus particles and primarily triggers G-to-A hypermutations in the viral genome during reverse transcription (RT). Vif binds to A3G to provoke ubiquitination and proteosomal degradation. Although Vif is absolutely essential for efficient HIV-1 replication in A3G-expressing cells, excessive Vif is deleterious, since massive levels of Vif inhibit proteolytic Gag processing (19).

In the present study, we focused on the functional importance of splicing regulatory elements within exon 2/2b. On the basis of our results, we provide evidence that multiple SREs within exon 2/2b tightly regulate proper vif mRNA production. We could underline the functional importance of ESE2b, bound by Tra2 and SRSF10, and the newly discovered exonic splicing silencer 2b (ESS2b), bound by hnRNP A/B proteins, for splice donor use and exon recognition. Point mutations within the SREs predicted via the HEXplorer algorithm, as well as locked nucleic acid (LNA) masking, altered both viral vif mRNA and Vif protein amounts by regulating exon 2/2b inclusion and led to a drop in viral particle production.

(This research was conducted by A.-L. Brillen in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a PhD from Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany, 2017.)

RESULTS

Tra2 and SRSF10 act via ESE2b to activate the downstream splice donor D2b.

To understand splice site selection critical for HIV-1 vif mRNA formation, we focused on the exonic 2b region downstream of splice donor D2 (Fig. 1). The vif start codon is localized upstream of an alternative splice donor, termed D2b, which defines the 3′ end of exon 2b, but needs to be repressed to retain the downstream intronic sequence coding for Vif. Previously, we have shown that D2b is repressed by a conserved G run (GI2-1) located immediately upstream, which is bound by hnRNP F/H (17). As inactivating GI2-1 led to upregulation of the intrinsically rather weak splice donor D2b, we hypothesized that GI2-1 not only represses D2b but might additionally shield an upstream bound SR protein from activating D2b (17). This assumption was further supported by the observation that, in the presence of multiple exonic SREs, the SRE closest to the splice donor likely dominates splicing decisions (12). Therefore, we tested the region between D2 and D2b for splice donor-enhancing properties and split the region into four overlapping segments, as indicated in Fig. 1B. To test the segments for splice donor-enhancing properties, we used an HIV-1 subgenomic reporter that allows monitoring of SRE-mediated U1 snRNP binding to splice donor D4, forming an enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP)-encoding mRNA by splicing to splice acceptor A7 (20–22) (Fig. 1C, top). Following transient transfection, fluorescence microscopy allowed a first rough estimation of enhancing properties in the four exonic 2b segments. We used the sequence CCAAACAA (23) as a splicing-neutral reference and the very strongly enhancing purine-rich SRE HIV-1 GAR E42 fragment as a positive control (GAR contains GAA or GAG repeats [R is A or G]) (20, 22). As expected, fragment IV, covering GI2-1, did not support downstream splice donor use, while ESE2b (ESE5005–5032 [13]), contained in fragment III, enhanced D2b use. Neither fragment I nor fragment II led to increased eGFP expression (Fig. 1C, bottom), demonstrating that ESE2b was the only SRE in the 3′ part of exon 2b capable of supporting downstream splice donor usage.

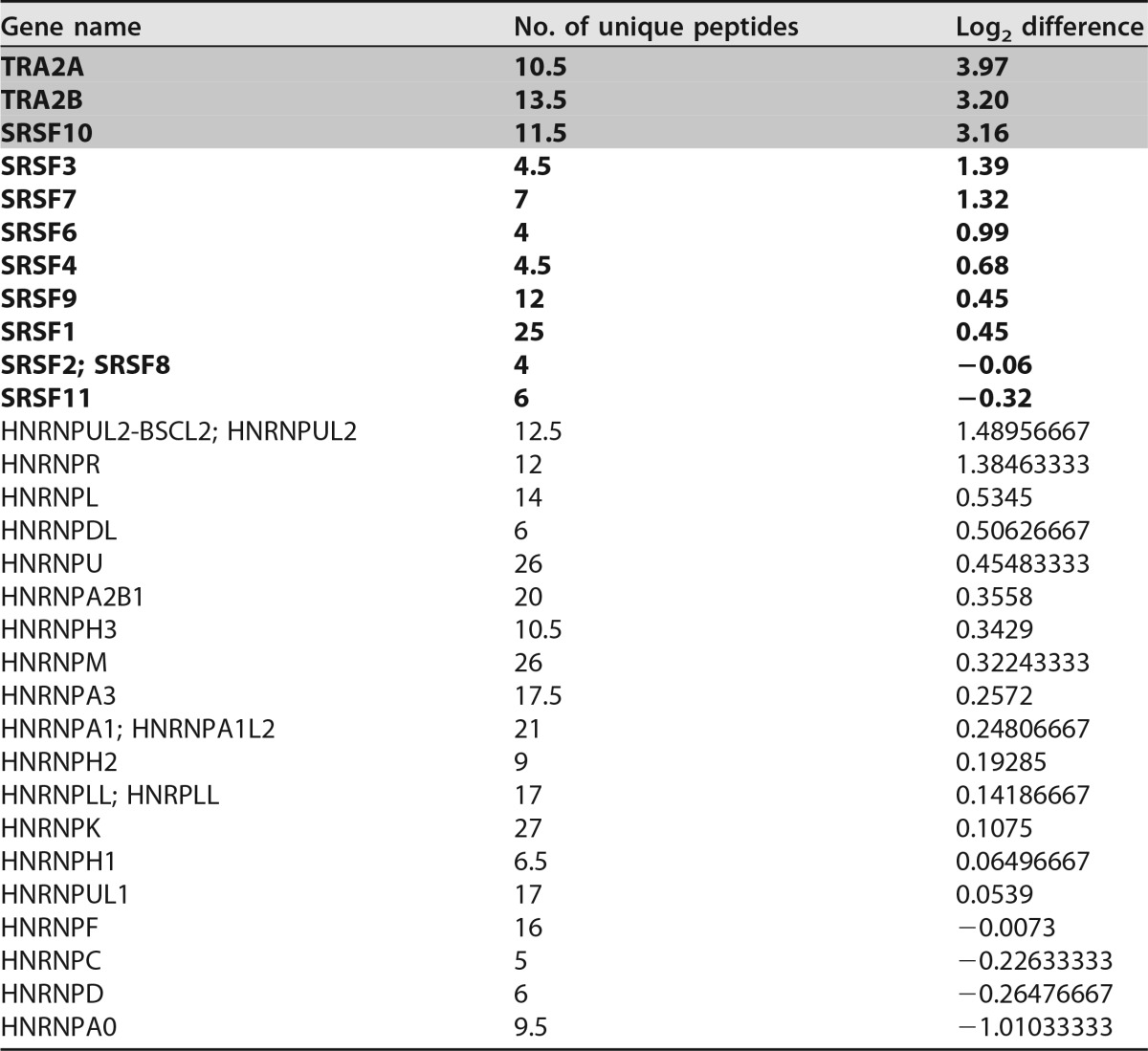

To identify splicing regulatory proteins binding to ESE2b, we made use of the previously published inactivating nucleotide substitutions predicted by the HEXplorer algorithm [ESE2bMUT (ΔHZEI −267), termed “5015A>T” or “5025A>T (dm)” in reference 13]. Here, regions with positive HEXplorer scores (HZEI) have been shown to exhibit downstream splice-enhancing properties, and a negative HEXplorer score difference ΔHZEI means that the mutations render the region less downstream enhancing. We performed RNA affinity purification assays with RNA oligonucleotides containing either the ESE2b or the ESE2bMUT sequence. After coupling to agarose beads, the oligonucleotides were incubated with HeLa cell nuclear extract. After washing and elution, bound proteins were analyzed via mass spectrometry (MS). Besides weak binding to several members of the SR protein family, we found a significant loss of the proteins Tra2α, Tra2β, and SRSF10 in the mutant ESE2b sequence and no significant change in the level of any hnRNP (Table 1) (P = 0.05; t test).

TABLE 1.

Mass spectrometry analysis of ESE2b (average of duplicates)a

Unique peptides and log2 differences of SR (boldface) and hnRNPs enriched after RNA affinity purification are shown; log2 differences of normalized protein intensities were calculated as wild-type minus mutated sequence samples; log2 differences significant at the 5% level (2 sided) are indicated by shading.

SREs between D2 and ESE2b are necessary to maintain splicing at D2.

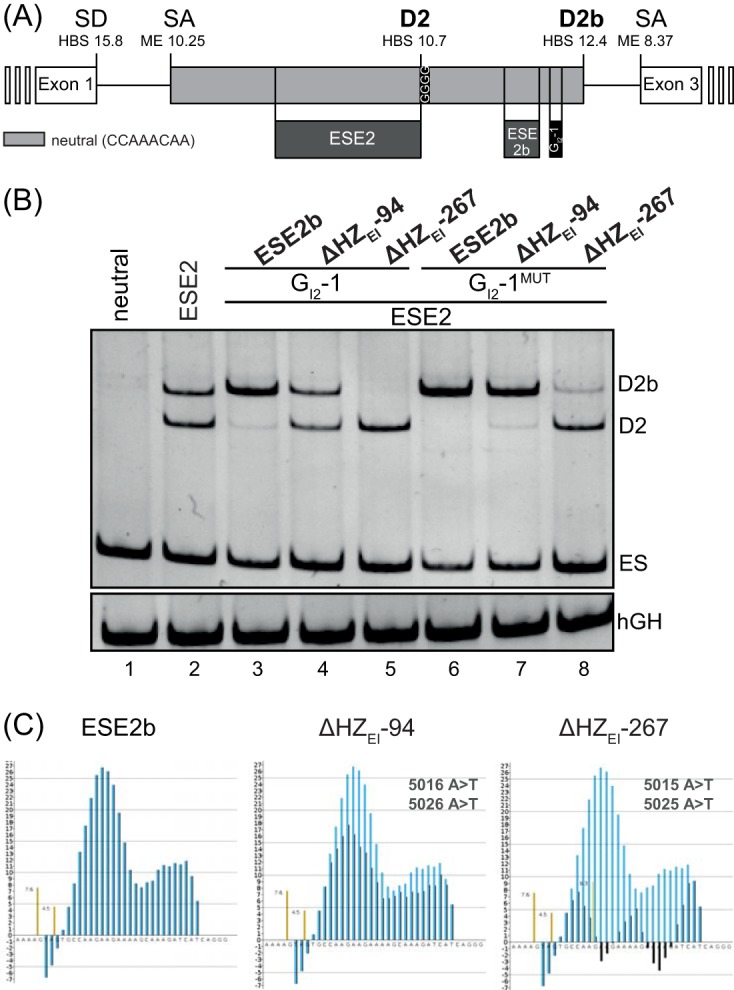

To test the impact of ESE2b on D2/D2b splice donor selection, we used a heterologous three-exon minigene splicing reporter (Fig. 2A) previously shown to be suitable to dissect the role of cis-acting SREs in splice donor decisions in complex splicing networks (24). Within this splicing reporter, the artificial internal exon was not recognized at all when it was completely composed of splicing-neutral sequences (23) but could be exonized upon replacing neutral sequences by cis-acting SREs or by increasing splice donor complementarity to U1 snRNA above an HBond score (HBS) of 15.8 (24). Here, we quantified splice donor complementarity to U1 snRNA by the experimentally derived HBS (range, 1.8 to 23.8) and splice acceptor strength by the MaxEnt score (ME). When we inserted both viral splice donors, D2 (HBS, 10.7) and D2b (HBS, 12.4), into this context of neutral sequences, the exon was not recognized, even though it is bordered by an intrinsically strong splice acceptor (ME, 10.25) (Fig. 2B, lane 1). To recapitulate HIV-1 exon 2 splice site recognition, all known exon 2-localized SREs—ESE-Vif (16), ESE-M1 and -M2 (15), and the GGGG motif (16), as well as ESE2b and GI2-1 (for simplicity, collectively referred to here as ESE2)—were inserted either individually or in combination into the exon at their authentic positions either upstream or downstream of D2 (Fig. 2A).

FIG 2.

Impact of ESE2b on D2b recognition. (A) Schematic of the three-exon minigene. The middle exon is composed of only neutral CCAAACAA repeats (23), except for D2, D2b, and the depicted SREs. (B) RT-PCR analyses of the splicing pattern of the minigene shown in panel A. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with 1 μg of each construct and 1 μg of pXGH5. RNA isolated from the cells was subjected to RT-PCRs using primer pairs #2648/#2649 and #1224/#1225 (human growth hormone [hGH]). The PCR amplicons were separated on a nondenaturing 10% polyacrylamide gel and stained with ethidium bromide. (C) HZEI plots of ESE2b and its two mutants (ΔHZEI = −94 and ΔHZEI = −267). Black, mutated sequence; blue, wild-type reference; brown, HBond scores for WT; yellow, HBond scores for mutants.

Replacing corresponding neutral sequences with ESE2 alone comparably activated D2 and D2b (Fig. 2B, cf. lanes 1 and 2). Additionally replacing neutral sequences with ESE2b and GI2-1 switched splice donor selection to almost exclusive D2b rather than D2 use (Fig. 2B, lane 3), indicating that ESE2b not only strongly supported D2b selection, overriding the repressive GI2-1 activity, but at the same time blocked the upstream-localized D2. Even though D2b has higher complementarity to U1 snRNA than D2 (HBS, 12.4 versus 10.7), in the viral context it is rarely used: 0.2% versus 5.3% D2 usage (17). To examine the impact of ESE2b variants on splice donor selection, we tested two ESE2b mutations that reduced its splice-enhancing activity (WT > ΔHZEI-94 > ΔHZEI-267). For brevity, we also denote these mutations by their corresponding ΔHZEI values with respect to the wild-type sequence, which reflect the reduction in splice-enhancing properties (Fig. 2C).

As shown in Fig. 2B, a stepwise switch toward D2 usage occurred when we reduced the ESE2b HEXplorer score by 2-nucleotide (nt) mutations, thus weakening its splice-enhancing activity (Fig. 2B, cf. lanes 3 to 5). This D2b-to-D2 transition occurred with both intact and inactivated GI2-1 (Fig. 2B, cf. lanes 6 to 8), but in the latter case, a larger reduction in ESE2b splice-enhancing activity was required to switch to D2 selection. Thus, splicing occurred at the weaker upstream splice donor, D2, if the combined splice-enhancing properties of ESE2b and GI2-1 did not suffice to move splice donor selection to D2b, located downstream.

So far, however, HIV-1 D2 usage, as in the viral context, could not be mimicked with this minigene, indicating that there may be an additional cis-acting element in the viral sequence. Such an SRE, localized between D2 and ESE2b, might act like an “insulator” separating the ESE2 from the ESE2b activity. Therefore, we profiled exon 2b for further enhancing and silencing properties of splice donor neighborhoods. The region located directly downstream of splice donor D2 (Fig. 3A, top left [WT]) includes four consecutive peaks (A, B, C, and D) of the HEXplorer profile. It exhibits predominantly HZEI-negative areas and is supposed to support the splice donor D2, located upstream.

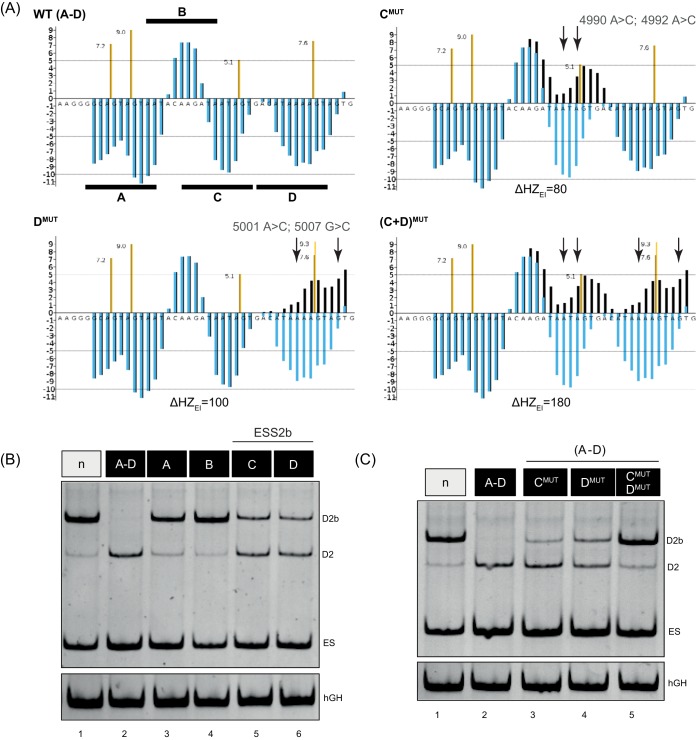

FIG 3.

ESS2b, located between D2 and ESE2b, is bound by members of the hnRNP A/B family and counteracts ESE2b. (A) HEXplorer score profiles of segments A to D (black horizontal bars) and mutations of segment C, D, or both, composing ESS2b (black, mutated sequence; blue, wild-type reference; brown, HBond scores for WT; yellow, HBond scores for mutants). The arrows indicate mutated nucleotides. (B and C) Mutational analysis of ESS2b. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with 1 μg of each construct and 1 μg of pXGH5. Twenty-four hours after transfection, RNA was isolated from the cells and subjected to RT-PCR analysis using primer pairs #2648/#2649 and #1224/#1225 (hGH).

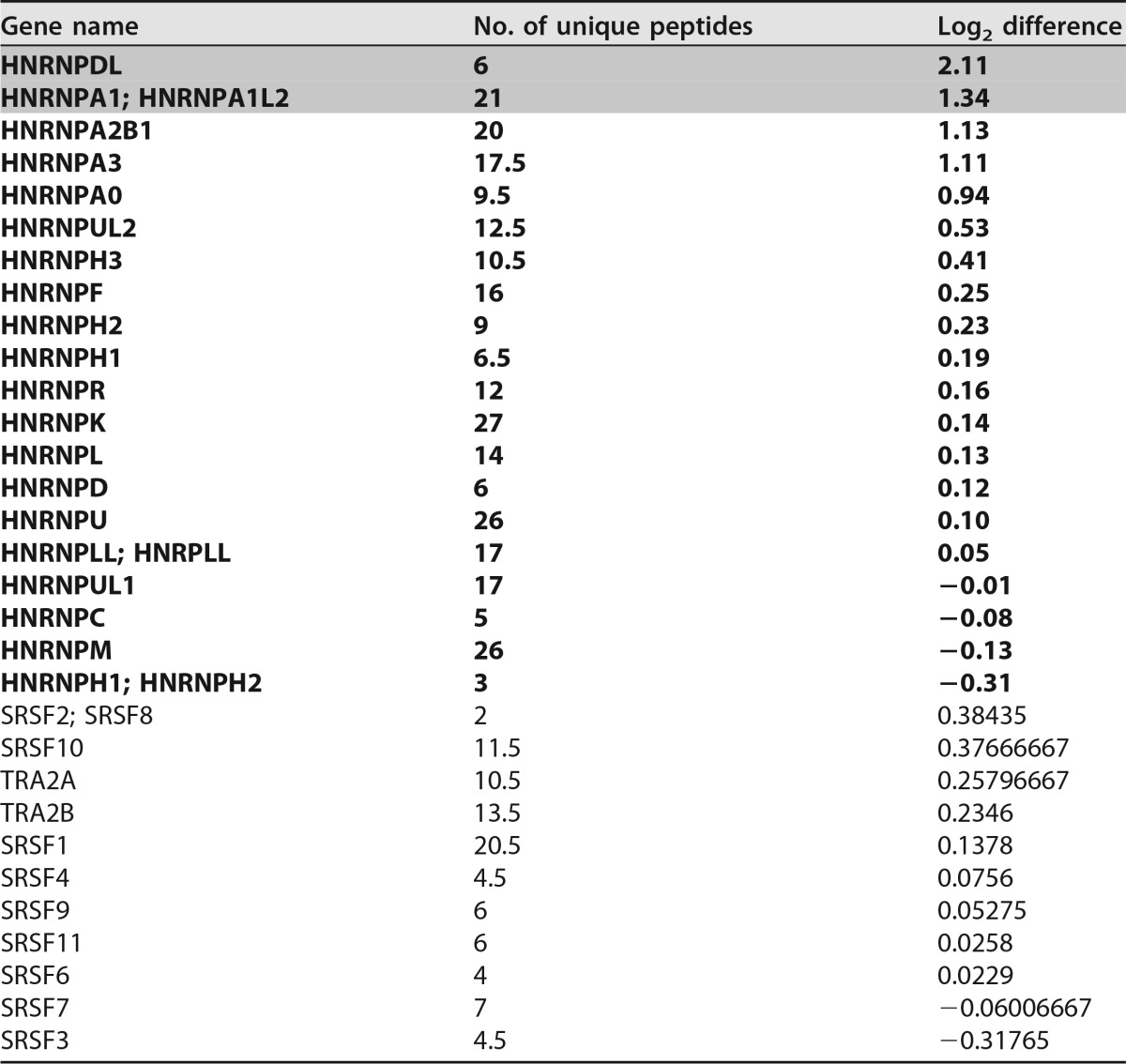

We then substituted either the whole fragment (WT; A to D) or individual fragments (A, B, C, and D) for neutral sequences of the same length in the minigene reporter. After RT-PCR analysis, it became obvious that, indeed, the region from A through D reversed splice site selection from D2b to the native HIV-1 splice donor, D2, which is more frequently used in the viral context (Fig. 3B, cf. lanes 1 and 2). Further analyses of the individual fragments demonstrated that fragments C and D, rather than fragment A or B, affected splice donor choice (Fig. 3B, lanes 3 to 6). However, as neither fragment C nor D on its own was sufficient to fully induce the splice donor switch, we concluded that the potential SRE spanned both fragments and termed it ESS2b. To examine our hypothesis, we specifically changed ESS2b by HEXplorer-guided mutagenesis in fragment C, D, or both in the context of A to D [Fig. 3A, CMUT, DMUT, and (C+D)MUT]. Analysis of the splicing pattern (Fig. 3C) revealed that mutating either C or D led to a partial splice donor switch, whereas simultaneously mutating C and D showed the same splicing phenotype as the neutral sequence (Fig. 3C, cf. lanes 1 and 5). These results demonstrate that ESS2b spans C and D, enhances upstream D2, and represses downstream D2b recognition in the presence of downstream ESE2b. Next, to identify splicing regulatory proteins binding to ESS2b, we again performed RNA affinity purification with WT and mutant sequences as described above. Subsequent MS analysis revealed that, besides hnRNP DL binding, members of the hnRNP A/B family (the hnRNP A/B family includes isoforms A1, A2/B1, A3, and A0) especially were markedly enriched in the WT compared to the mutant sample, whereas, in contrast, no SR protein was significantly enriched (P = 0.05; t test) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Mass spectrometry analysis of ESS2b (average of duplicates)a

Unique peptides and log2 differences of SR and hnRNPs (boldface) enriched after RNA affinity purification are shown; log2 differences of normalized protein intensities were calculated as wild-type minus mutated sequence samples; log2 differences significant at the 5% level (2 sided) are indicated by shading.

Taken together, the data show that multiple SREs within exon 2/2b balance splice donor selection in a strictly position-dependent manner.

ESS2b and ESE2b regulate balanced splice donor usage in provirus-transfected cells.

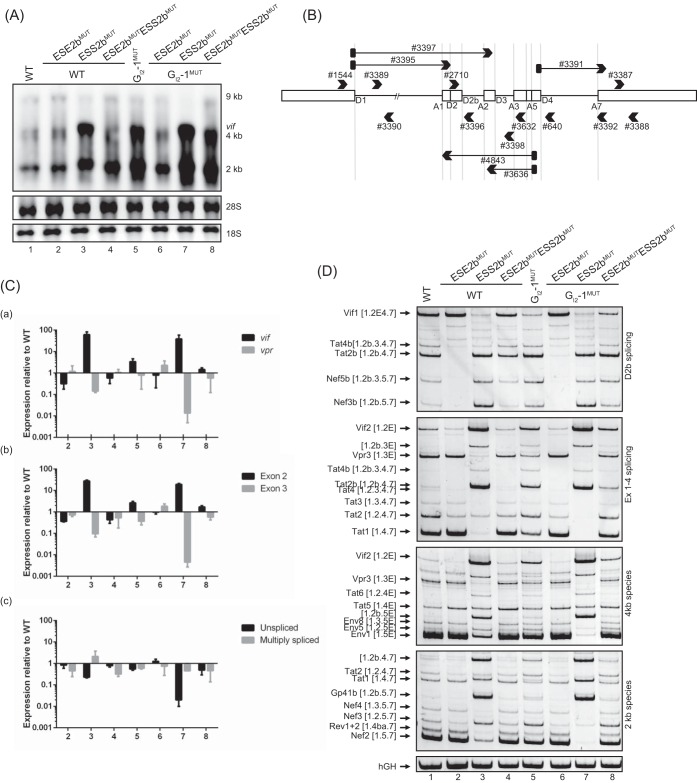

To analyze the impacts of ESS2b and ESE2b on viral pre-mRNA splicing, we inserted both of the most promising inactivating mutations, ESE2bMUT (ΔHZEI = −267) and ESS2bMUT [(C+D)MUT], either individually or in combination into pNL4-3 proviral plasmid DNA (GenBank accession no. M19921) (25), with and without the inactivating GI2-1 mutation (17). RNA was isolated 48 h after transfection of HEK293T CD4+ cells, subjected to Northern blot analysis, and detected with an exon 7 probe hybridizing to all viral mRNAs. Mutating ESE2b showed no shift in viral mRNA levels compared to the wild-type proviral clone (Fig. 4A, cf. lanes 1 and 2), whereas, in contrast, inactivating ESS2b caused a strong increase not only in 4-kb vif mRNAs, but also in 2-kb mRNAs, which was accompanied by a reduction in 9-kb mRNAs (Fig. 4A, cf. lanes 1 and 3). Interestingly, inactivating mutations of both SREs seem to nearly compensate for each other (Fig. 4A, cf. lanes 1 and 4), suggesting that though there seems to be no obvious effect of mutating ESE2b in viral mRNA distribution at first glance, the two SREs together critically regulate the balance of HIV-1 RNA classes. In agreement with our previous results (17), mutating GI2-1 caused an increased amount of 2-kb and, particularly, of 4-kb vif mRNAs, which was comparable to inactivating ESS2b (Fig. 4A, cf. lanes 3 and 5). Inactivation of ESS2b and GI2-1 resulted in an even stronger effect (Fig. 4A, cf. lanes 1, 5, and 7).

FIG 4.

ESE2b and ESS2b cause alterations in proviral pre-mRNA processing. (A) Northern blot analysis of total RNA isolated from HEK293T CD4+ cells transfected with wild-type or mutant pNL4-3. A hybridization probe specifically detecting HIV-1 exon 7 was used. (B) Binding sites of (q)RT-PCR primers. Open boxes indicate exons. Black arrowheads denote primers. Black arrows with filled black rectangles and arrowheads denote exon-exon junction primers. (C) qRT-PCR of total RNA isolated from the same RNA preparation as in panel A to specifically quantitate the levels of vif versus vpr (a) and [1.2.5] versus [1.3.5.] (b) and multiply spliced versus unspliced (c) mRNA species, displaying exp(−ΔCT) ratios normalized to the wild-type splicing pattern. The bar graphs show means and standard deviations of three replicates. Primer pair #3387/#3388, specifically detecting exon 7, was used for normalization. The following primer pairs were used: vif, #3395/#3396; vpr, #3397/#3398; [1.2.5], #3395/#4843; [1.3.5], #3397/#3636; multiply spliced, #3391/#3392; and unspliced, #3389/#3390. (D) RT-PCR analysis of RNAs used in panels A and C. The following primer pairs were used: #1544/#3632 (Ex1-4 splicing), #2710/#3392 (D2b splicing), #1544/#3392 (2-kb species), and #1544/#640 (4-kb species). HIV-1 mRNA species according to Purcell and Martin (3) are indicated on the left of each gel image. Exon numbers are indicated in square brackets; those including an E read through D4.

Next, to quantitatively measure individual HIV-1 transcript ratios, RT-PCRs were set up with different primer pairs, each normalized to the total amount of all viral mRNAs measured with primers detecting exon 7 (#3387/#3388) (Fig. 4B). Since exon 2 and exon 3 recognition underlie inverse regulation (26–29), we used exon junction primer pairs specifically detecting vif and vpr or [1.2.5] and [1.3.5] (exon numbers are indicated in square brackets) nef mRNAs as two distinct targets for exon 2 versus exon 3 inclusion in viral mRNAs (#3395/#3396 for vif, #3397/#3398 for vpr, #3395/#4843 for [1.2.5] nef, and #3397/#3636 for [1.3.5] nef) (Fig. 4B). As expected, inactivation of ESE2b showed no significant change in vif, vpr, and [1.2.5] and [1.3.5] nef mRNA levels (1-way analysis of variance [ANOVA] with Dunnett's post hoc test), whereas disruption of ESS2b induced a huge upregulation of vif and [1.2.5] nef (P < 0.001; Dunnett's post hoc test) and a reduction of vpr and [1.3.5] nef mRNAs (Fig. 4C, a and b, cf. bars 2 and 3). Inactivation of both SREs resulted in mRNA levels comparable to those of the wild type (Fig. 4C, a and b, bars 4). Likewise, inactivation of GI2-1 led to comparable effects, with an overall higher level of vif mRNAs (Fig. 4C, a, bars 5 to 8, vif). Furthermore, we measured the levels of unspliced and multiply spliced mRNAs with both intact and inactivated GI2-1 (#3389/#3390 for unspliced; #3391/#3392 for multiply spliced) (Fig. 4B). There was no significant difference from the wild type after disruption of ESE2b (Dunnett's post hoc test) but a clear decrease in unspliced mRNAs for inactivating ESS2b (Fig. 4C, c, cf. bars 2 and 3 and bars 6 and 7), which could again be compensated for by additionally mutating ESE2b (Fig. 4C, c, lanes 4 and 8).

To break down what impact the two mutations had on distinct mRNA species, we also performed semiquantitative RT-PCR. In line with minigene analyses and position-dependent effects, inactivating ESE2b revealed a complete loss of D2b use (Fig. 4D, D2b splicing, lane 2, e.g., Tat2b), whereas there was an elevated level of D2b use after inactivating ESS2b (Fig. 4D, D2b splicing, lane 3, e.g., Nef3b) and an upregulation of otherwise low-abundance mRNA species (Fig. 4D, 2-kb species, lane 3, e.g., Gp41b [1.2b.5.7]) (17). Moreover, inactivating ESE2b led to a slight decrease in exon-2-containing transcripts, like vif2 or tat2 (Fig. 4D, Ex1-4 splicing, lane 2). A mirror image inverted phenotype occurred after inactivation of ESS2b, where an increased degree of exon 2 inclusion could be observed (vif2), entailing a drop in exon 3 inclusion and vpr messages (vpr3), thereby sustaining their mutually regulated roles in HIV-1 splicing, as shown by quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis in Fig. 4C (Fig. 4D, Ex1-4 splicing and 4-kb species, lane 3). Comparing overall 2-kb and 4-kb mRNA species in general, only marginal differences from wild-type pNL4-3 could be detected for ESE2b (Fig. 4D, 2 kb and 4 kb, cf. lanes 1 and 2), compatible with Northern blot analysis. As expected, for ESS2b, elevated levels of exon 2 inclusion with a concomitant reduction in mRNAs including exon 3 could be observed (Fig. 4D, 2 kb and 4 kb, cf. lanes 1 and 3). Again, for all detected mRNA species, a splicing pattern comparable to that of wild-type pNL4-3 was observed if both SREs had been mutated (Fig. 4D, cf. lanes 1 and 4). As shown before, inactivation of GI2-1 resulted in enhanced exon 2b inclusion, followed by an increased amount of exon 2-containing transcripts, supporting the exon-bridging function of A1 with respect to D2 and D2b (Fig. 4D, cf. lanes 1 and 5). Additionally mutating ESE2b or ESS2b had no or only minor effects on the splicing patterns (Fig. 4D, cf. lanes 2 and 6 and lanes 3 and 7). In summary, RT-PCR analyses of RNA expressed from proviral clone pNL4-3 confirmed the results of the minigene analyses, revealing ESE2b and ESS2b as essential SREs regulating splice donor usage within exon 2/2b and thus vif mRNA processing.

ESE2b and ESS2b are essential for viral infectivity.

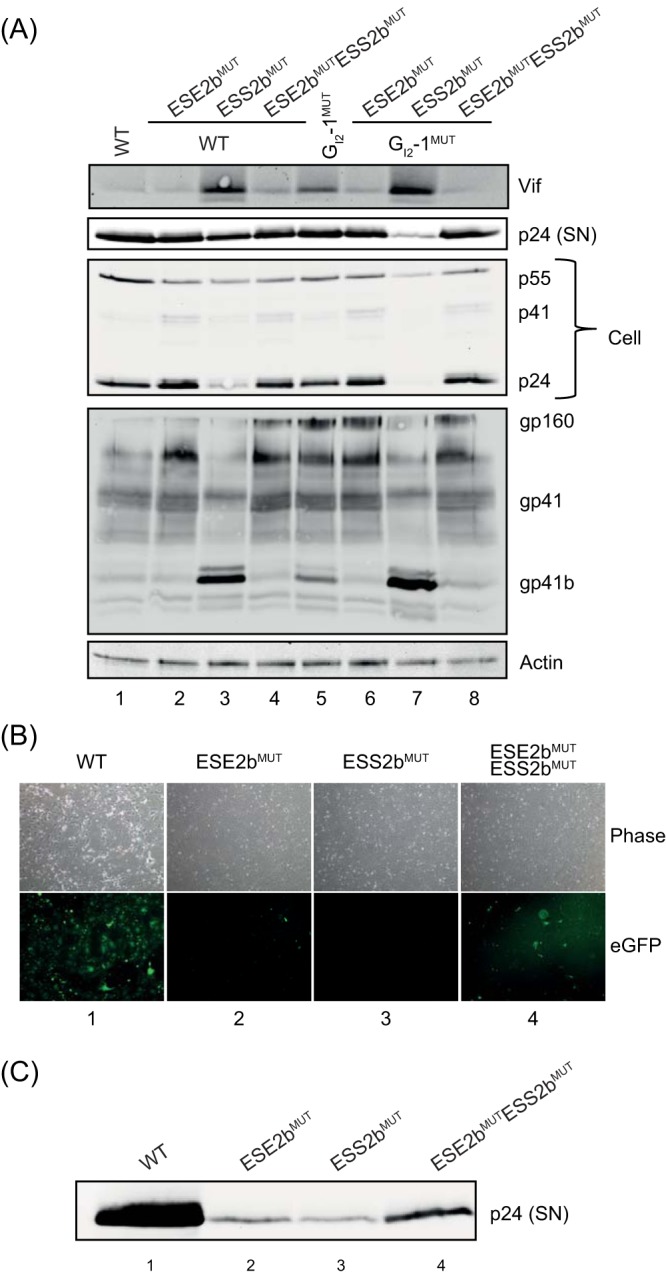

To test to what extent changes in exon 2/2b inclusion reflect viral protein expression, we performed immunoblot analysis. No obviously different phenotype for the investigated proteins was observed after inactivating ESE2b (Fig. 5A, cf. lanes 1 and 2). In agreement with the data obtained from (q)RT-PCR analysis, a strong increase in the Vif protein level could be observed after inactivating ESS2b (Fig. 5A, cf. lanes 1 and 3). As expected, mutating both SREs brought the Vif protein level back to the wild-type pNL4-3 level (Fig. 5A, cf. lanes 1 and 4). Additionally interrupting GI2-1 enhanced the effect of ESS2b and further increased Vif protein expression (Fig. 5A, lane 7). Moreover, a drop in intracellular p24 Gag levels, as well as in viral capsid within the supernatant, could be observed for the ESS2b mutant with intact or inactivated GI2-1 (Fig. 5A, lanes 3 and 7). Furthermore, we used an antibody directed against the C-terminal domain of Gp41 (Chessie 8 [30]) to examine the presence of the previously described Gp41b isoform (17). In agreement with RT-PCR analyses, Gp41b protein was also enriched after ESS2b mutation (Fig. 5A, cf. lanes 3 and 7).

FIG 5.

Impairment of proper viral particle production. (A) Immunoblot analysis of proteins of pelleted virions from the supernatants (SN) of transfected cells described in Fig. 4. (B and C) HEK293T cells (2.5 × 105) were transfected with pNL4-3 and mutant proviruses; 48 h posttransfection, the supernatant was collected for infection of GHOST CD4+ cells, an indicator cell line that expresses eGFP after HIV-1 infection. Infection and viral replication were analyzed 48 h postinfection, both by fluorescence microscopy (B) and by p24-gag Western blot analysis (C) of supernatants of the infected GHOST CD4+ cells.

Eventually, we tested whether viral particles within the supernatants harboring either individual or both mutations were still infectious. For this, we used GHOST cells that stably expressed the CD4 receptor and contained an LTR-dependent gene for eGFP. Thus, after successful infection and Tat-mediated transactivation of the LTR promoter, eGFP expression could be easily monitored via fluorescence microscopy. Forty-eight hours postinfection, strong eGFP expression was observed for wild-type pNL4-3, and it was clearly reduced in the ESE2b mutant-infected cells (Fig. 5B, cf. columns 1 and 2). Furthermore, infection with ESS2b mutant viral particles led to complete loss of eGFP expression, which was partially restored in cells infected with viral particles harboring both mutations (Fig. 5B, cf. columns 3 and 4). p24 levels within the supernatant reflected the observed eGFP expression (Fig. 5C). In summary, the severely altered phenotype of the ESS2b mutant already observed during (q)RT-PCR and Northern and Western blot analyses led to a complete failure of infectiousness. Surprisingly, mutating ESE2b already showed a clear drop in eGFP expression, which was not indicated by the transfection experiments alone. Thus, an already slight imbalance in viral exon 2 splicing could lead to an impairment of proper viral particle production. In viral particles containing both mutations, balance could be restored, at least to some extent.

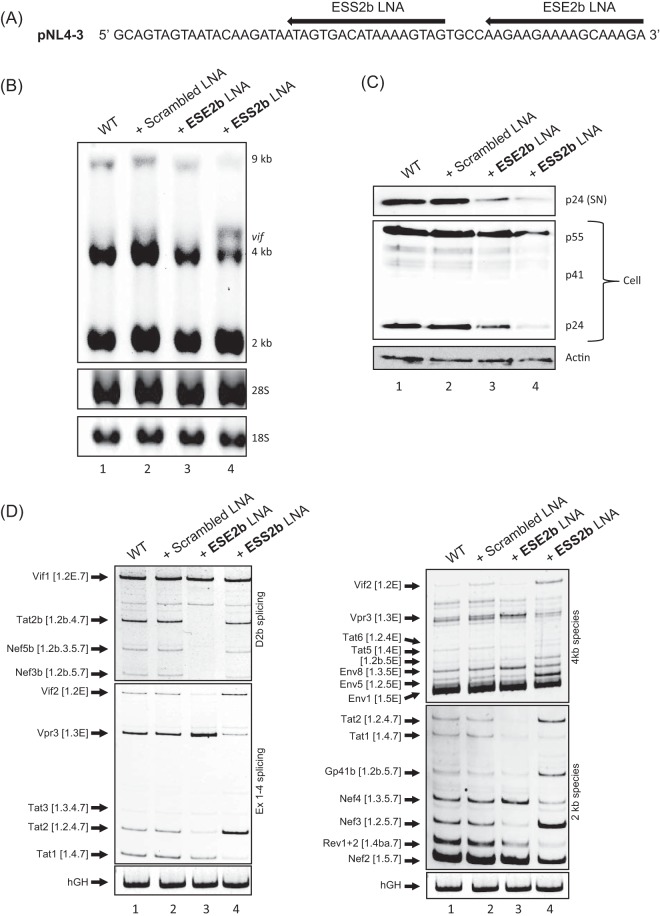

Masking of ESE2b and ESS2b restricts viral particle production.

As was shown previously (26, 27), the use of LNAs can mimic the mutational analysis of SREs within the provirus. The modified antisense oligonucleotides are able to mask any specific sequence, in particular SREs, and thereby inhibit the binding of SR or hnRNPs. We used LNAs targeting either ESE2b or ESS2b and cotransfected them with pNL4-3 (Fig. 6A). Scrambled LNAs not targeting any viral sequence were used as a control. Forty-eight hours posttransfection, RNA and protein were isolated and analyzed for mRNA levels and protein expression. Northern blot analysis revealed distributions of viral mRNA classes when the two SREs were masked by LNAs similar to those obtained by SRE mutation (cf. Fig. 4A and 6B). Here, LNAs targeting ESE2b showed a slight reduction of 4-kb mRNAs, whereas LNAs targeting ESS2b showed a strong increase in 4-kb vif mRNA and a decrease in unspliced 9-kb mRNA (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, we examined the levels of both intracellular Gag protein and virus particles released into the supernatant (Fig. 6C). In agreement with the p24 levels detected after virus infection (Fig. 5C), we observed significantly less p24 Gag within both cells and supernatant for both LNAs. Additionally, RT-PCR analysis showed a dramatic loss of exon 2/2b inclusion for LNAs targeting ESE2b (Fig. 6D, e.g., vif2 and tat2b, cf. lanes 1 and 3), followed by an increase in exon 3 inclusion (Fig. 6D, e.g., vpr3, cf. lanes 1 and 3). Conversely, splicing shifted toward exon 2 inclusion when LNAs against ESS2b were applied (Fig. 6D, e.g., vif2 and tat2, cf. lanes 1 and 4), while exon 3 inclusion was reduced at the same time (Fig. 6D, e.g., vpr3, cf. lanes 1 and 4). Taken together, the data show that masking ESE2b or ESS2b with LNAs showed a phenotype very similar to that in infection experiments and was able to inhibit proper virus particle production.

FIG 6.

LNA-directed masking of ESE2b and ESS2b mimics the mutational phenotype. (A) Schematic of LNA binding sites. (B) Northern blot analysis of total RNA. HeLa cells were cotransfected with pNL4-3 and either LNAs masking ESE2b or ESS2b or the scrambled LNA. Total RNA was isolated 24 h posttransfection and subjected to Northern blot analysis using an HIV-1 exon 7 probe. (C) Western blot analysis of cellular (Cell) and supernatant (SN) Gag of cotransfected cells from panel B. (D) RT-PCR analysis of different viral mRNA species. The following primer pairs were used: #1544/#3632 (Ex1-4 splicing), #2710/#3392 (D2b splicing), #1544/#3392 (2-kb species), and #1544/#640 (4-kb species). HIV-1 mRNA species are indicated on the left of each gel image according to Purcell and Martin (3). Exon numbers are indicated in square brackets; those including an E read through D4.

In summary, thee data obtained in these experiments highlight the existence of a tight cluster of splicing regulatory elements within exon 2/2b that balances viral mRNA and protein production. Inhibiting protein binding to those elements disrupts viral particle production and infectivity.

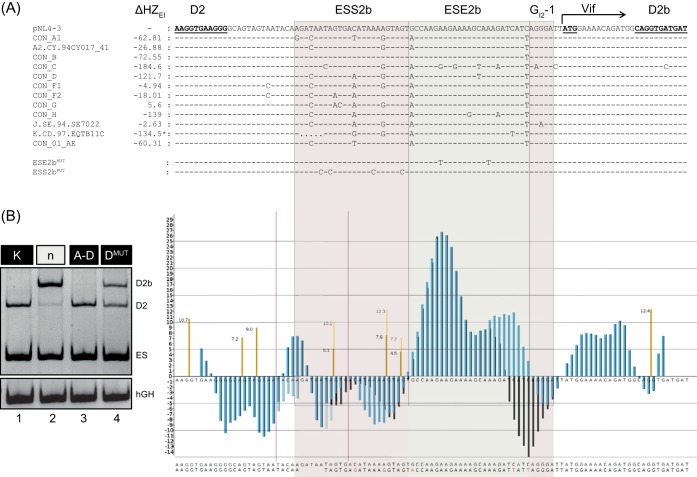

Multiple SRE sequence variations between HIV-1 subtypes.

Aligning the HIV-1 consensus sequences A1 to AE of HIV-1 exon 2/2b using the RIP 3.0 software (https://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/RIP/RIP.html) showed that sequence variations between viral strains occurred strikingly more often within the regions containing the splicing regulatory elements ESS2b, ESE2b, and GI2-1, while the flanking sequences were mainly conserved (Fig. 7A). The impact of these natural nucleotide variations on splice-enhancing properties was reflected in their HEXplorer profiles. Indeed, HIV strains showed a wide range of ΔHZEI scores. In order to examine one exemplary naturally occurring variation, we substituted in the minigene reporter the subtype K sequence exhibiting both high ΔHZEI and an additional deletion of 5 nucleotides within ESS2b. In fact, subtype K experimentally showed a splicing phenotype similar to that of A to D with a slight tendency toward D2 usage (Fig. 7B, left, cf. lanes 1 and 3). The HEXplorer profile of subtype K (Fig. 7B, right, black bars) showed only a minor effect on ESS2b compared to pNL4-3 (blue bars) and weaker ESE2b. Both effects tend to shift splice site selection further toward D2, which is barely visible, since D2 already dominates splicing in pNL4-3. The high SRE sequence variability between HIV-1 subtypes may suggest an equally wide range of splicing regulatory properties that permits adjusting Vif levels to A3G levels in a variety of cellular host environments.

FIG 7.

Analysis of SREs within exon 2/2b of different HIV-1 subtypes. (A) pNL4-3-derived HIV-1 exon 2/2b consensus sequences from A1 to AE of the different HIV-1 subtypes, together with their HEXplorer score differences (ΔHZEI). Conserved sequences are represented by dashes and differences by letters. Regions with SREs are shown with red or green shading. The subtype sequences were analyzed with the RIP 3.0 software (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/RIP/RIP.html). (B) (Left) Splicing patterns of the splicing reporter carrying SRE regions of subtype K (lane 1) and pNL4-3 (lane 3). For reference, lanes 2 and 4, corresponding to the neutral sequence and to DMUT, are also shown. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with 1 μg of each construct and 1 μg of pXGH5; 24 h after transfection, RNA was isolated from the cells and subjected to RT-PCR analysis using primer pairs #2648/#2649 and #1224/#1225 (hGH). (Right) HEXplorer profiles of pNL4-3 and exemplary subtype K containing a 5-nt deletion (between vertical red lines) and several single-nucleotide variations. Blue, HEXplorer profile for pNL4-3; black, subtype K; brown, HBond scores for WT; yellow, HBond scores for mutants.

DISCUSSION

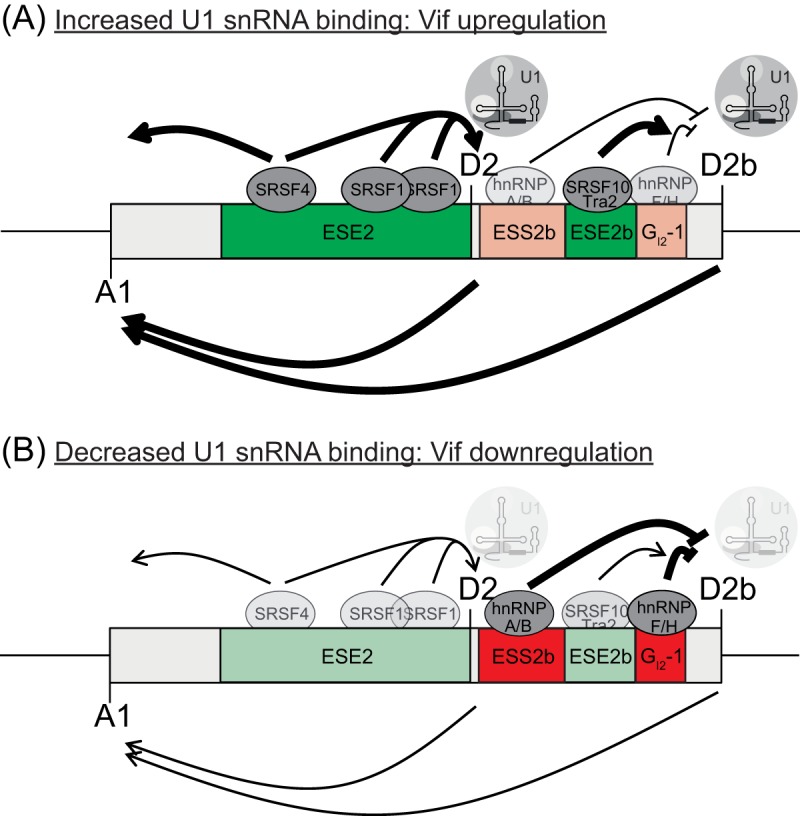

The data presented in this work show that a splicing regulatory network (Fig. 8) regulates HIV-1 exon 2/2b inclusion in viral mRNAs, thus optimizing viral replication via competing actions of several SREs located close to D2 and D2b. In particular, we identified the Tra2/SRSF10-binding site ESE2b and the hnRNP A/B-binding site ESS2b, which could be specifically masked by LNAs. Both SREs contribute to regulating splice donors D2/D2b and splice acceptor A1, as well as vif mRNA and protein production.

FIG 8.

Model for exon 2/2b recognition. Exon 2/2b inclusion and splice donor usage are regulated by a complex network of SREs. (A) SR proteins binding to both ESE2 and ESE2b support U1 snRNP binding at the downstream splice donors D2 and D2b. Exon definition leads to the concomitant upregulation of splice acceptor A1 and to higher vif mRNA expression (left-pointing arrows below exon 2/2b). (B) Lower levels of SR proteins, as well as hnRNP binding to sites ESS2b and GI2-1, reduce U1 snRNP binding to D2 and D2b.

During alternative splicing, recognition of splice sites is most often facilitated not only by conserved sequence elements, like the splice donor and splice acceptor, but also by RNA secondary structure (2, 31–33) and a multitude of splicing regulatory elements. While splicing patterns of various HIV-1 subtypes are mostly conserved, the frequency of splice site usage can depend on the temperature (2) and the presence of splicing regulatory proteins (14).

Within the noncoding exon 2/2b, six different SREs have already been described. Three elements exist that enhance recognition of splice donor D2 and thereby inclusion of exon 2 in viral mRNAs: ESE-M1 and -M2 (bound by SRSF1) (15) and ESE-Vif (bound by SRSF4) (16). Furthermore, an inhibitory GGGG motif, overlapping the already intrinsically weak D2, inhibits its use and exon 2 inclusion (16), potentially through sterical hindrance of the U1 snRNP. We have previously reported that a G run located downstream of exon 2 inhibits the splice donor D2b lying further downstream by binding of hnRNP F/H (GI2-1) (17). Inactivation of this GI2-1 motif led to a strong increase in the use of the otherwise only little used donor D2b. This was attributed to the fact that binding of hnRNP F/H leads to the formation of a “dead-end” complex, meaning that the U1 snRNP binds to the splice donor without actually splicing at this position (12, 34, 35).

Upregulation of D2b use following GI2-1 inactivation indicated that an SR protein binding site could be located within exon 2b. We had previously found an enhancing element located downstream of D2 in a HEXplorer-based screen of total HIV-1 mRNA (13). Continuing analysis of this element here showed that the enhancer ESE2b strongly activates D2b and simultaneously inhibits D2, which is facilitated by binding of SRSF10 and Tra2. Tra2β was previously shown to bind to GA-rich sequence elements (36–39), similar to the sequence of ESE2b. Cloning this element into the minigene indeed led to an excessive splicing phenotype at D2b, which, however, was not observed in a physiological HIV-1 splicing context. During infection, we could confirm by RNA deep sequencing that D2b is only marginally used (0.2%) compared to D2 (5.3%) (17). Here, we resolve this apparent discrepancy between splicing patterns of minigene and infection experiments by identifying a novel SRE located within exon 2b, ESS2b, which counteracts the strong ESE2b effects. By using MS analysis, we show that ESS2b is bound by members of the hnRNP A/B family, which fits earlier studies showing that those proteins bind to sequences that include a TAG motif (40, 41).

It might be surprising that such a multitude of SREs should regulate splice donor selection in a noncoding exon. However, in order to obtain Vif, splice acceptor A1 must be used, and A1 itself seems to require activation by an exon definition complex (42, 43) in which U1 snRNP binding to either D2 or D2b promotes the recognition of the splice acceptor A1, located upstream, by U2 snRNPs. On the other hand, splicing at D2 or D2b prevents Vif expression, which relies on intron 2 retention. This is similar to env mRNA processing, where U1 snRNP binding to a splicing-incompetent D4 was needed for splice acceptor A5 activation (44). Thus, the commonly observed larger amounts of both intron-retaining—leading to Vif expression—and exon 2-including mRNAs could be due to increased U1 snRNA complementarity or mutations of neighboring SREs (16, 17, 29, 45).

Only balanced levels of Vif expression contribute to maximal viral replication, while excessive Vif expression is detrimental to viral replication due to perturbation of proteolytic Gag processing (19). On the other hand, excessive splicing at D2 leads to a decrease of unspliced mRNAs and, consequently, a reduction of Gag/Gag-Pol expression levels and a defect in virion production. This effect has also been termed “oversplicing” and is in line with our observation revealing that excessive Vif expression after mutating or masking of ESS2b leads to a reduction of overall unspliced mRNAs and impairment of cellular Gag and viral particles within the supernatant. However, not only excessive Vif levels, but also insufficient amounts are deleterious to viral replication. Vif is essential for counteracting the host cell restriction factor A3G, and an imbalance in the Vif/A3G ratio strongly affects viral replication. It was shown that if restriction pressure is low, lower Vif levels are sufficient to counteract A3G, whereas excessive Vif impedes viral replication ability (19, 46). However, conversely, HIV-1 replicates only in cells with high restriction pressure if sufficient Vif is present (17, 46).

Nomaguchi et al. identified natural single-nucleotide variations within different HIV-1 isolates proximal to HIV-1 A1 (SA1prox) that could be shown to regulate vif mRNA and Vif protein expression and were linked to the fact that effective viral replication critically depends on an optimal Vif/A3G ratio (17, 46). Here, we found nucleotide variations predominantly within splicing regulatory elements in exon 2/2b.

Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that the vast number of SREs within exon 2/2b ensures viral replication in cells with different A3G or splicing regulatory protein concentrations, e.g., by a mechanism like mutual evolution (46).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Single-intron splicing constructs.

All eGFP single-intron splicing reporters are based on the well-established HIV-1 glycoprotein/eGFP expression plasmid (20). Insertion of exon 2b parts I to IV was carried out by replacing GAR E42 of SV GAR E42 SD4 Δvpu env eGFP D36G (22) with a PCR product obtained with primer pairs #4200/#4201 (part I), #4202/#4203 (part II), #4204/#4205 (part III), and #4206/#4207 (part IV), respectively. The neutral sequence (23) was inserted 3.5 times as described above with primer pair #4213/#4214.

Three-exon minigenes.

The three-exon minigenes are derived from the fibrinogen Bβ minigene pT-Bβ-IVS7 + 1G>T (47, 48). The middle exon was replaced with only splicing-neutral sequences (23) by using a customized synthetic gene from Invitrogen and inserted into pT-Bβ-IVS7 + 1G>T via EcoNI/Bpu10I. HIV-1-derived splice donors D2 and D2b were inserted with PCR products resulting from primer pair #4793/#4794. ESE-Vif, -M1, and -M2 were inserted by PCR with primer pair #4853/#2620. Fragments of HIV-1 exon 2/2b were added at their authentic positions relative to D2 or D2b, respectively, by using primer pairs #4795/#2620 (ESE2b and GI2-1), #4798/#2620 (ΔHZEI-94 and GI2-1), #5318/#2620 (ΔHZEI-267 and GI2-1), #4796/#2620 (ESE2b and GI2-1MUT), #5319/#2620 (ΔHZEI-94 and GI2-1MUT), #5317/#2620 (ΔHZEI-267 and GI2-1MUT), #5251/#2620 (ESS2b WT [A to D]), #5337/#2620 (ESS2b part A), #5339/#2620 (ESS2b part B), #5341/#2620 (ESS2b part C), and #5343/#2620 (ESS2b part D). The fragment of HIV-1 subtype K was added at its authentic position flanked by D2 and D2b using primer pair #5712/#5713. HEXplorer-guided mutations of ESS2b were inserted via PCR products resulting from primer pairs #5392/#2620 (CMUT), #5393/#2620 (DMUT), and #5394/#2620 [(C+D)MUT].

Proviral plasmids.

pNL4-3 ESE2bMUT proviral DNA was generated by the overlapping-PCR technique using primers #5549/#4773 and #5553/#5550, pNL4-3 ESS2bMUT using primer pairs #5547/#4773 and #5553/#5548, and pNL4-3 ESE2bMUT ESS2bMUT using primer pairs #5551/#4773 and #5553/#5552. pNL4-3 GI2-1MUT has been described previously (17) and was used as a template instead of pNL4-3, using the primer pairs described above to generate double or triple mutations.

Expression plasmids.

pXGH5 (49) was cotransfected to monitor transfection efficiency. pCL-dTOM was cotransfected to detect the transfection efficiency of each sample in fluorescence microscopy analysis. The plasmid expresses the fluorescent protein Tomato and was kindly provided by H. Hanenberg.

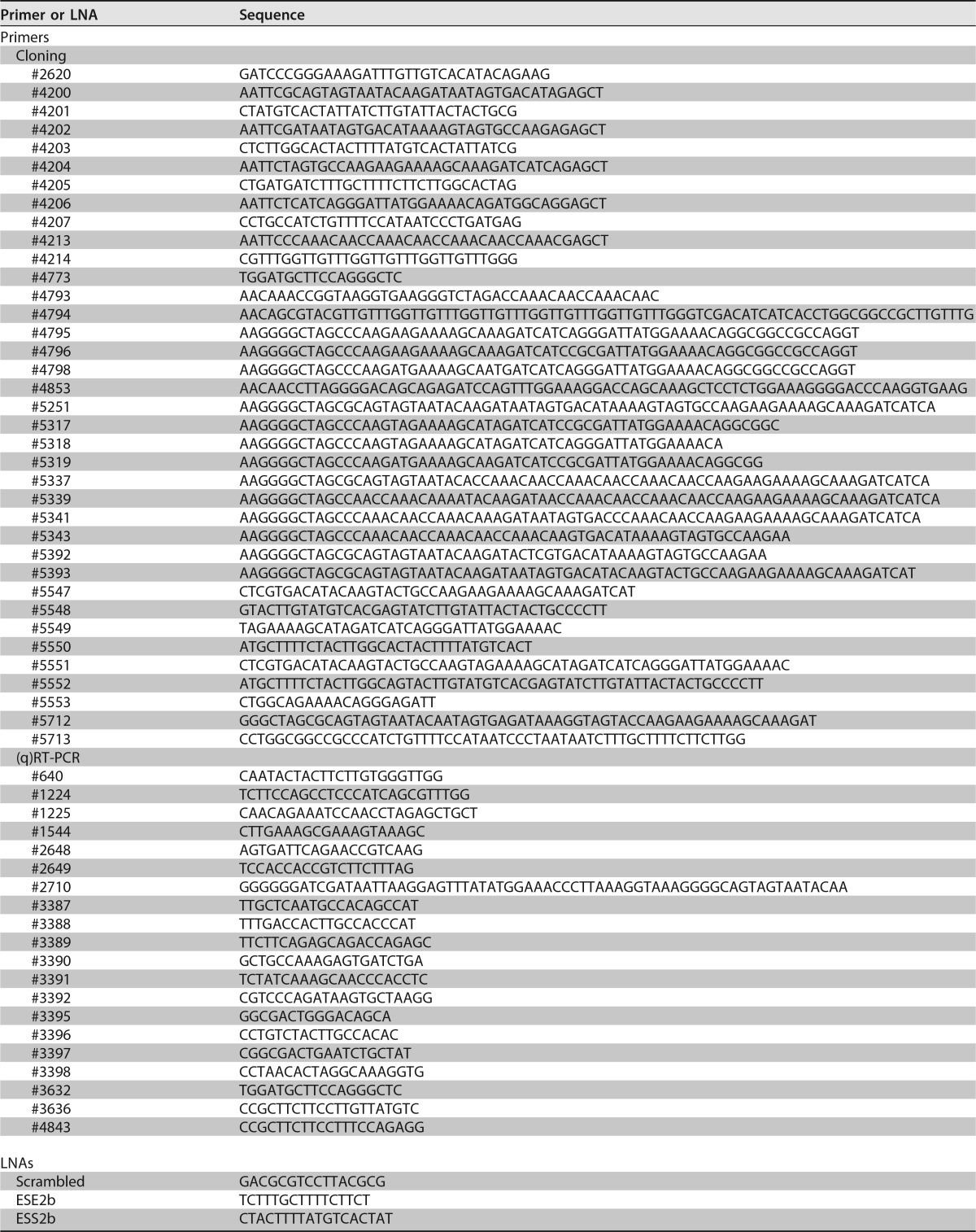

Oligonucleotides.

All the oligonucleotides used were obtained from Metabion GmbH (Planegg, Germany) (Table 3). RNase-free high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-purified LNAs were purchased from Exiqon (Denmark).

TABLE 3.

Sequences of primers used for cloning and (q)RT-PCR analyses and of LNAs

Cell culture and transfection.

HeLa, HEK293T (CD4+), or GHOST (3) CXCR4+ cells (50) were cultured in Dulbecco's high-glucose modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 50 μg/ml penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen). For transient transfection, 2 × 105 cells per six-well plate were used. Transient-transfection experiments were performed using TransIT-LT1 transfection reagent (Mirus Bio LLC) according to the manufacturer's instructions. LNA transfection was performed as described previously 26.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR.

Twenty-four or 48 h posttransfection, total RNA was isolated by using acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform (51). For semiquantitative and quantitative RT-PCR analyses, RNA was reverse transcribed by using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and oligo(dT) primers (Invitrogen) and amplified using the primer pairs depicted in Fig. 4B.

Northern blotting.

Three micrograms of total RNA isolated by using acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform (51) was separated on a denaturing 1% agarose gel and then capillary blotted onto a positively charged nylon membrane. Hybridization was carried out using a digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled HIV-1 exon 7 PCR amplicon (#3387/#3388) as previously described (17).

Protein isolation and Western blotting.

Protein samples were heated to 95°C for 10 min and loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels for Western blot analysis. The samples were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane; probed with primary and secondary antibodies (sheep antibody against HIV-1 p24 CA; Aalto), mouse monoclonal antibody specific for HIV-1 Vif (ab66643; Abcam), mouse anti-gp41 (Chessie 8 [30]), and mouse anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody (A5316; Sigma-Aldrich); and developed with ECL chemiluminescence reagent (GE Healthcare).

RNA affinity purification assay.

RNA oligonucleotides (3,000 pmol) for either a WT or mutant version of ESE2b and ESS2b, respectively, were covalently coupled to adipic acid dihydrazide agarose beads (Sigma). A 60% HeLa cell nuclear extract (Cilbiotech) was added to the immobilized RNAs. After five stringent washing steps with buffer D containing different concentrations of KCl (0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 0.25, and 0.1 M KCl, together with 20 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.9], 5% [vol/vol] glycerol, 0.2 M EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.4 M MgCl2), the precipitated proteins were eluted in protein sample buffer. Samples were sent to the Molecular Proteomics Laboratory, BMFZ, Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany, for MS analysis as described in detail previously (24).

HBond score.

The HBS measures splice donor strength by its complementarity to U1 snRNA, combining experimental evidence with a computational hydrogen bond weight model.

The HBond score algorithm models hydrogen bond formation at individual positions, as well as nucleotide interdependence beyond nearest-neighbor relationships. It also takes positions +7 and +8 fully into account, as experiments have confirmed U1 snRNA duplex dependency on these nucleotides. The hydrogen bond pattern between a splice donor site and all 11 nt of the free 5′ end of U1 snRNA is translated into a numerical HBond score in the range 1.8 to 23.8, with CAG/GTAAGTAT corresponding to an HBS of 23.8. The HBond score is available through the Web interface (http://www.uni-duesseldorf.de/rna/html/hbond_score.php).

HEXplorer score.

In a RESCUE-type approach, the HZEI is based on different hexamer occurrences in exonic and intronic sequences in the neighborhood of splice donors, and it has been successfully used as a basis for the identification of exonic splicing regulatory elements (13, 24).

Different hexamer frequencies up- and downstream of splice donors are first translated into Z-scores for all 4,096 hexamers. For any index nucleotide in a genomic sequence, its HZEI is then calculated as the average hexamer Z-score of all six hexamers overlapping with this index nucleotide. This algorithm permits the plotting of HEXplorer score profiles along genomic sequences, and they reflect splice-enhancing or -silencing properties in the neighborhood of a splice donor: HEXplorer score positive regions support downstream splice donors and repress upstream ones, and HZEI negative regions do the opposite. HEXplorer score profiles of wild-type and mutant sequences were calculated using the Web interface (https://www2.hhu.de/rna/html/hexplorer_score.php).

qPCR statistics.

In qPCR experiments, expression levels relative to the WT were calculated as exp(−ΔCT) (threshold cycle) ratios. The bar graphs show means and standard deviations of three replicates. Statistical significance was determined separately for each sample (vif, vpr, exon 2, exon 3, unspliced, and multiply spliced) by 1-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test correcting for multiple comparisons.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Björn Wefers for excellent technical assistance. The following reagents were obtained through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: Chessie 8 from George Lewis and GHOST (3) CXCR4+ cells from Vineet N. KewalRamani and Dan R. Littman.

Funding was provided by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (SCHA 909/8-1) and Jürgen Manchot Stiftung (to A.-L.B., L.W., and H.S.) and by Stiftung für AIDS-Forschung, Düsseldorf (to H.S.).

A.-L.B. and H.S. conceived the study and designed the experiments. A.-L.B., L.W., L.M., and M.W. performed cloning, transfection experiments, and (q)RT-PCR analyses. A.-L.B. performed RNA pulldown analyses. F.H. performed LNA-related experiments. S.T., A.-L.B., and H.S. performed HEXplorer analyses. S.T. provided statistical analyses. A.-L.B., S.T., and H.S. wrote the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ocwieja KE, Sherrill-Mix S, Mukherjee R, Custers-Allen R, David P, Brown M, Wang S, Link DR, Olson J, Travers K, Schadt E, Bushman FD. 2012. Dynamic regulation of HIV-1 mRNA populations analyzed by single-molecule enrichment and long-read sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res 40:10345–10355. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emery A, Zhou S, Pollom E, Swanstrom R. 2017. Characterizing HIV-1 splicing by using next-generation sequencing. J Virol 91:e02515–. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02515-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Purcell DF, Martin MA. 1993. Alternative splicing of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mRNA modulates viral protein expression, replication, and infectivity. J Virol 67:6365–6378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim SY, Byrn R, Groopman J, Baltimore D. 1989. Temporal aspects of DNA and RNA synthesis during human immunodeficiency virus infection: evidence for differential gene expression. J Virol 63:3708–3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klotman ME, Kim S, Buchbinder A, DeRossi A, Baltimore D, Wong Staal F. 1991. Kinetics of expression of multiply spliced RNA in early human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of lymphocytes and monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88:5011–5015. (Erratum, 89:1148, 1992.) doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.3.1148b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohammadi P, Desfarges S, Bartha I, Joos B, Zangger N, Munoz M, Gunthard HF, Beerenwinkel N, Telenti A, Ciuffi A. 2013. 24 hours in the life of HIV-1 in a T cell line. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003161. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karn J, Stoltzfus CM. 2012. Transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of HIV-1 gene expression. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2:a006916. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Will CL, Luhrmann R. 2011. Spliceosome structure and function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3:a003707. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berget SM. 1995. Exon recognition in vertebrate splicing. J Biol Chem 270:2411–2414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.6.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romfo CM, Alvarez CJ, van Heeckeren WJ, Webb CJ, Wise JA. 2000. Evidence for splice site pairing via intron definition in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Cell Biol 20:7955–7970. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.21.7955-7970.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fox-Walsh KL, Dou Y, Lam BJ, Hung SP, Baldi PF, Hertel KJ. 2005. The architecture of pre-mRNAs affects mechanisms of splice-site pairing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:16176–16181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508489102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erkelenz S, Mueller WF, Evans MS, Busch A, Schoneweis K, Hertel KJ, Schaal H. 2013. Position-dependent splicing activation and repression by SR and hnRNP proteins rely on common mechanisms. RNA 19:96–102. doi: 10.1261/rna.037044.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erkelenz S, Theiss S, Otte M, Widera M, Peter JO, Schaal H. 2014. Genomic HEXploring allows landscaping of novel potential splicing regulatory elements. Nucleic Acids Res 42:10681–10697. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stoltzfus CM. 2009. Chapter 1. Regulation of HIV-1 alternative RNA splicing and its role in virus replication. Adv Virus Res 74:1–40. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(09)74001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kammler S, Otte M, Hauber I, Kjems J, Hauber J, Schaal H. 2006. The strength of the HIV-1 3′ splice sites affects Rev function. Retrovirology 3:89. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Exline CM, Feng Z, Stoltzfus CM. 2008. Negative and positive mRNA splicing elements act competitively to regulate human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vif gene expression. J Virol 82:3921–3931. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01558-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Widera M, Erkelenz S, Hillebrand F, Krikoni A, Widera D, Kaisers W, Deenen R, Gombert M, Dellen R, Pfeiffer T, Kaltschmidt B, Munk C, Bosch V, Kohrer K, Schaal H. 2013. An intronic G run within HIV-1 intron 2 is critical for splicing regulation of vif mRNA. J Virol 87:2707–2720. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02755-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheehy AM, Gaddis NC, Choi JD, Malim MH. 2002. Isolation of a human gene that inhibits HIV-1 infection and is suppressed by the viral Vif protein. Nature 418:646–650. doi: 10.1038/nature00939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akari H, Fujita M, Kao S, Khan MA, Shehu-Xhilaga M, Adachi A, Strebel K. 2004. High level expression of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 Vif inhibits viral infectivity by modulating proteolytic processing of the Gag precursor at the p2/nucleocapsid processing site. J Biol Chem 279:12355–12362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312426200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kammler S, Leurs C, Freund M, Krummheuer J, Seidel K, Tange TO, Lund MK, Kjems J, Scheid A, Schaal H. 2001. The sequence complementarity between HIV-1 5′ splice site SD4 and U1 snRNA determines the steady-state level of an unstable env pre-mRNA. RNA 7:421–434. doi: 10.1017/S1355838201001212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freund M, Asang C, Kammler S, Konermann C, Krummheuer J, Hipp M, Meyer I, Gierling W, Theiss S, Preuss T, Schindler D, Kjems J, Schaal H. 2003. A novel approach to describe a U1 snRNA binding site. Nucleic Acids Res 31:6963–6975. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caputi M, Freund M, Kammler S, Asang C, Schaal H. 2004. A bidirectional SF2/ASF- and SRp40-dependent splicing enhancer regulates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 rev, env, vpu, and nef gene expression. J Virol 78:6517–6526. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6517-6526.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang XH, Arias MA, Ke S, Chasin LA. 2009. Splicing of designer exons reveals unexpected complexity in pre-mRNA splicing. RNA 15:367–376. doi: 10.1261/rna.1498509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brillen AL, Schoneweis K, Walotka L, Hartmann L, Muller L, Ptok J, Kaisers W, Poschmann G, Stuhler K, Buratti E, Theiss S, Schaal H. 2017. Succession of splicing regulatory elements determines cryptic 5′ss functionality. Nucleic Acids Res 45:4202–4216. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adachi A, Gendelman HE, Koenig S, Folks T, Willey R, Rabson A, Martin MA. 1986. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J Virol 59:284–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Widera M, Hillebrand F, Erkelenz S, Vasudevan AA, Munk C, Schaal H. 2014. A functional conserved intronic G run in HIV-1 intron 3 is critical to counteract APOBEC3G-mediated host restriction. Retrovirology 11:72. doi: 10.1186/s12977-014-0072-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erkelenz S, Hillebrand F, Widera M, Theiss S, Fayyaz A, Degrandi D, Pfeffer K, Schaal H. 2015. Balanced splicing at the Tat-specific HIV-1 3′ss A3 is critical for HIV-1 replication. Retrovirology 12:29. doi: 10.1186/s12977-015-0154-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Madsen JM, Stoltzfus CM. 2005. An exonic splicing silencer downstream of the 3′ splice site A2 is required for efficient human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. J Virol 79:10478–10486. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10478-10486.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mandal D, Feng Z, Stoltzfus CM. 2010. Excessive RNA splicing and inhibition of HIV-1 replication induced by modified U1 small nuclear RNAs. J Virol 84:12790–12800. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01257-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abacioglu YH, Fouts TR, Laman JD, Claassen E, Pincus SH, Moore JP, Roby CA, Kamin Lewis R, Lewis GK. 1994. Epitope mapping and topology of baculovirus-expressed HIV-1 gp160 determined with a panel of murine monoclonal antibodies. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 10:371–381. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abbink TE, Berkhout B. 2008. RNA structure modulates splicing efficiency at the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 major splice donor. J Virol 82:3090–3098. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01479-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zychlinski D, Erkelenz S, Melhorn V, Baum C, Schaal H, Bohne J. 2009. Limited complementarity between U1 snRNA and a retroviral 5′ splice site permits its attenuation via RNA secondary structure. Nucleic Acids Res 37:7429–7440. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mueller N, van Bel N, Berkhout B, Das AT. 2014. HIV-1 splicing at the major splice donor site is restricted by RNA structure. Virology 468–470C:609–620. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Domsic JK, Wang Y, Mayeda A, Krainer AR, Stoltzfus CM. 2003. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 hnRNP A/B-dependent exonic splicing silencer ESSV antagonizes binding of U2AF65 to viral polypyrimidine tracts. Mol Cell Biol 23:8762–8772. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.23.8762-8772.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharma S, Kohlstaedt LA, Damianov A, Rio DC, Black DL. 2008. Polypyrimidine tract binding protein controls the transition from exon definition to an intron defined spliceosome. Nat Struct Mol Biol 15:183–191. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tacke R, Tohyama M, Ogawa S, Manley JL. 1998. Human Tra2 proteins are sequence-specific activators of pre-mRNA splicing. Cell 93:139–148. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grellscheid S, Dalgliesh C, Storbeck M, Best A, Liu Y, Jakubik M, Mende Y, Ehrmann I, Curk T, Rossbach K, Bourgeois CF, Stevenin J, Grellscheid D, Jackson MS, Wirth B, Elliott DJ. 2011. Identification of evolutionarily conserved exons as regulated targets for the splicing activator tra2beta in development. PLoS Genet 7:e1002390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsuda K, Someya T, Kuwasako K, Takahashi M, He F, Unzai S, Inoue M, Harada T, Watanabe S, Terada T, Kobayashi N, Shirouzu M, Kigawa T, Tanaka A, Sugano S, Guntert P, Yokoyama S, Muto Y. 2011. Structural basis for the dual RNA-recognition modes of human Tra2-beta RRM. Nucleic Acids Res 39:1538–1553. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Erkelenz S, Poschmann G, Theiss S, Stefanski A, Hillebrand F, Otte M, Stuhler K, Schaal H. 2013. Tra2-mediated recognition of HIV-1 5′ splice site D3 as a key factor in the processing of vpr mRNA. J Virol 87:2721–2734. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02756-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burd CG, Dreyfuss G. 1994. RNA binding specificity of hnRNP A1: significance of hnRNP A1 high-affinity binding sites in pre-mRNA splicing. EMBO J 13:1197–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kajita Y, Nakayama J, Aizawa M, Ishikawa F. 1995. The UUAG-specific RNA binding protein, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein D0. Common modular structure and binding properties of the 2xRBD-Gly family. J Biol Chem 270:22167–22175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robberson BL, Cote GJ, Berget SM. 1990. Exon definition may facilitate splice site selection in RNAs with multiple exons. Mol Cell Biol 10:84–94. doi: 10.1128/MCB.10.1.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoffman BE, Grabowski PJ. 1992. U1 snRNP targets an essential splicing factor, U2AF65, to the 3′ splice site by a network of interactions spanning the exon. Genes Dev 6:2554–2568. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12b.2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asang C, Hauber I, Schaal H. 2008. Insights into the selective activation of alternatively used splice acceptors by the human immunodeficiency virus type-1 bidirectional splicing enhancer. Nucleic Acids Res 36:1450–1463. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Madsen JM, Stoltzfus CM. 2006. A suboptimal 5′ splice site downstream of HIV-1 splice site A1 is required for unspliced viral mRNA accumulation and efficient virus replication. Retrovirology 3:10. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nomaguchi M, Doi N, Sakai Y, Ode H, Iwatani Y, Ueno T, Matsumoto Y, Miyazaki Y, Masuda T, Adachi A. 2016. Natural single-nucleotide variations in the HIV-1 genomic SA1prox region can alter viral replication ability by regulating Vif expression levels. J Virol 90:4563–4578. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02939-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spena S, Duga S, Asselta R, Malcovati M, Peyvandi F, Tenchini ML. 2002. Congenital afibrinogenemia: first identification of splicing mutations in the fibrinogen Bbeta-chain gene causing activation of cryptic splice sites. Blood 100:4478–4484. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spena S, Tenchini ML, Buratti E. 2006. Cryptic splice site usage in exon 7 of the human fibrinogen B beta-chain gene is regulated by a naturally silent SF2/ASF binding site within this exon. RNA 12:948–958. doi: 10.1261/rna.2269306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Selden RF, Howie KB, Rowe ME, Goodman HM, Moore DD. 1986. Human growth hormone as a reporter gene in regulation studies employing transient gene expression. Mol Cell Biol 6:3173–3179. doi: 10.1128/MCB.6.9.3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morner A, Bjorndal A, Albert J, Kewalramani VN, Littman DR, Inoue R, Thorstensson R, Fenyo EM, Bjorling E. 1999. Primary human immunodeficiency virus type 2 (HIV-2) isolates, like HIV-1 isolates, frequently use CCR5 but show promiscuity in coreceptor usage. J Virol 73:2343–2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. 1987. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem 162:156–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]