ABSTRACT

The emergence of pandemic GII.4 norovirus (NoV) strains has been proposed to occur due to changes in receptor usage and thereby to lead to immune evasion. To address this hypothesis, we measured the ability of human sera collected between 1979 and 2010 to block glycan binding of four pandemic GII.4 noroviruses isolated in the last 4 decades. In total, 268 sera were investigated for 50% blocking titer (BT50) values of virus-like particles (VLPs) against pig gastric mucin (PGM) using 4 VLPs that represent different GII.4 norovirus variants identified between 1987 and 2012. Pre- and postpandemic sera (sera collected before and after isolation of the reference NoV strain) efficiently prevented binding of VLP strains MD145 (1987), Grimsby (1995), and Houston (2002), but not the Sydney (2012) strain, to PGM. No statistically significant difference in virus-blocking titers was observed between pre- and postpandemic sera. Moreover, paired sera showed that blocking titers of ≥160 were maintained over a 6-year period against MD145, Grimsby, and Houston VLPs. Significantly higher serum blocking titers (geometric mean titer [GMT], 1,704) were found among IgA-deficient individuals than among healthy blood donors (GMT, 90.9) (P < 0.0001). The observation that prepandemic sera possess robust blocking capacity for viruses identified decades later suggests a common attachment factor, at least until 2002. Our results indicate that serum IgG possesses antibody-blocking capacity and that blocking titers can be maintained for at least 6 years against 3 decades of pandemic GII.4 NoV.

IMPORTANCE Human noroviruses (NoVs) are the major cause of acute gastroenteritis worldwide. Histo-blood group antigens (HBGAs) in saliva and gut recognize NoV and are the proposed ligands that facilitate infection. Polymorphisms in HBGA genes, and in particular a nonsense mutation in FUT2 (G428A), result in resistance to global dominating GII.4 NoV. The emergence of new pandemic GII.4 strains occurs at intervals of several years and is proposed to be attributable to epochal evolution, including amino acid changes and immune evasion. However, it remains unclear whether exposure to a previous pandemic strain stimulates immunity to a pandemic strain identified decades later. We found that prepandemic sera possess robust virus-blocking capacity against viruses identified several decades later. We also show that serum lacking IgA antibodies is sufficient to block NoV VLP binding to HBGAs. This is essential, considering that 1 in every 600 Caucasian children is IgA deficient.

KEYWORDS: VLP, norovirus, pandemic

INTRODUCTION

Human noroviruses (NoVs) are the leading cause of epidemic nonbacterial gastroenteritis, with genogroup II, genotype 4 (GII.4) viruses being the most common genotype, responsible for 60 to 80% of all NoV infections worldwide (1). As no convenient small-animal model exists and human NoVs have only recently been successfully cultivated in vitro (2, 3), studies aimed at understanding protective immunity and susceptibly factors have so far relied on data from natural outbreaks and experimental human challenge studies (4). Since the NoV capsid is composed primarily of a single protein, this protein governs immunogenicity and infectivity properties, thus interacting with both neutralizing/blocking antibodies and histo-blood group antigens (HBGAs), the proposed cellular binding ligands for NoV (5–7).

NoV infects individuals of all ages; however, approximately 20% of the Caucasian population is highly resistant to NoV GII.4 infections due to a nonsense mutation at position 428 in the FUT2 gene (8) that leads to the nonsecretor genotype, which has been found to provide strong protection against experimental and natural infections with some NoV genotypes (9–14).

NoV infection elicits a robust humoral immune response, and almost all adults have detectable NoV-specific antibodies. Early experimental challenge studies suggested that the duration of immunity elicited by NoV infection may be short (15, 16). However, the epochal pattern of evolution observed for GII.4 viruses suggests that NoV immunity may be more complex (17–19). While considering immune responses and protective immunity to NoV, it is relevant to recognize that not all antibodies elicited following vaccination or natural infections are protective. Serum antibodies that block binding of NoV to HBGA, such as gastric mucins, are at present the best correlate of protection against NoVs, and serum blockade assays are considered a surrogate for neutralization (4, 20–22). In addition, with recent successful cultivation of human norovirus in human intestinal enteroids, future studies might focus on evaluating virus neutralization, as well (2).

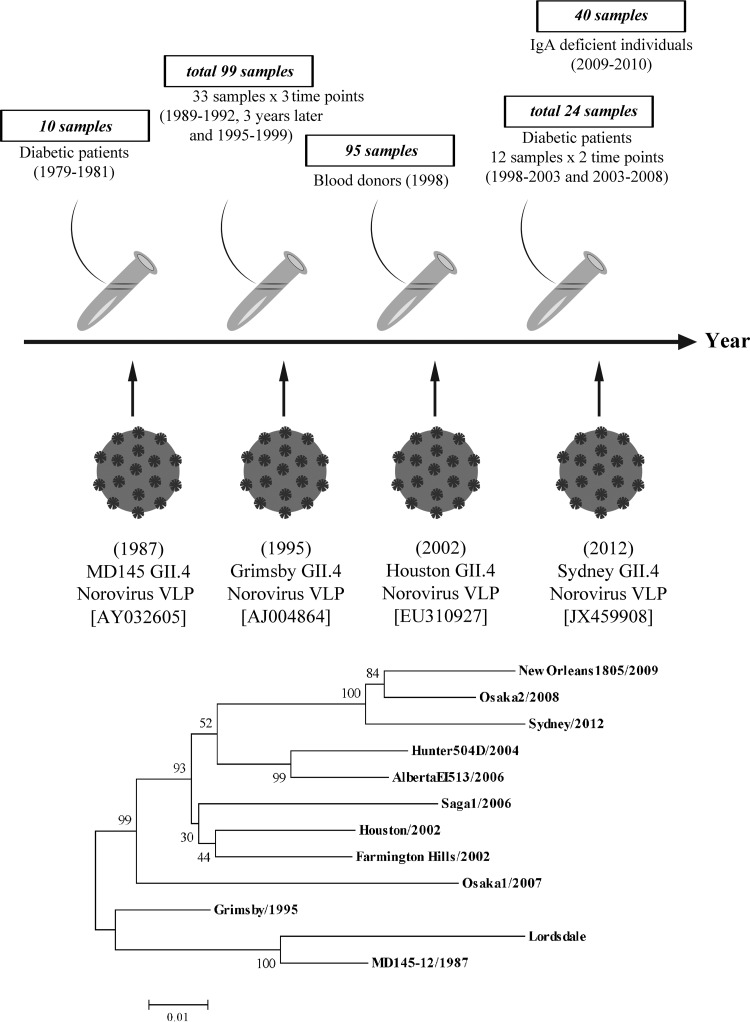

Previous serum blockade studies have, to our knowledge, investigated either experimentally challenged subjects, vaccinated individuals, patients from natural outbreaks, or norovirus-infected children (15, 16, 20, 21, 23–25). There are several important questions related to possible NoV immune-driven evolution and susceptibility rates in natural outbreaks, e.g., whether prepandemic sera have blocking capacity against GII.4 NoV variants that emerged much later and whether it is possible to determine susceptibility rates in a population based on a combination of serum blocking titer and host genetics. To address these and related questions, we had access to a unique panel of 268 Swedish sera collected from 1978 until 2010 (Fig. 1). The terms pre- and postpandemic sera refer to sera collected before and after the emergence of the reference norovirus strains used in the current study, respectively. These sera, except sera collected from children with type 1 diabetes mellitus, were considered representative of the NoV immune profile of a given population at a given time. About half of the sera are also paired, consisting of two or more samples taken from individuals at intervals of several years, thus adding an important feature of temporality. We investigated the ability of these sera to block binding to pig gastric mucin (PGM) with GII.4 NoV virus-like particles (VLPs) representing variant pandemic strains from different time periods, i.e., MD145 (isolated as early as 1987 [AY032605]), Grimsby, (isolated in 1995 [AJ004864]), Houston, (isolated in 2002 [EU310927]), and Sydney (isolated in 2012 [JX459908]).

FIG 1.

Serum samples and study design. In total, 268 serum samples collected between 1979 and 2010 were included in the study. Four different GII.4 recombinant VLPs, each representative of a different lineage and having a time-ordered emergence globally, were investigated: MD145, isolated in 1987 (AY032605); Grimsby, isolated in 1995 (AJ004864); Houston, isolated in 2002 (EU310927); and Sydney, isolated in 2012 (JX459908). The years shown in parentheses are the years of isolation of the reference GII.4 norovirus strains. The phylogenetic tree, based on nucleotide sequences of GII.4 NoV strains generated using the neighbor-joining method, shows that VLPs of GII.4 NoVs used in this study belong to different lineages. The numbers under the branches represent bootstrap values from 1,000 replicates.

The most novel finding of this study was that sera collected as early as 1979 could block binding to PGM of MD145, Grimsby, and Houston VLPs that emerged 9, 17, and 24 years after the serum collection and that possibly protective levels of blocking titers were maintained in several cases for up to 6 years. Additionally, the present study shows not only that IgA-deficient secretor sera block binding of VLPs to PGM, but also that geometric mean blocking titers (GMTs) are significantly higher among IgA-deficient individuals than in healthy non-IgA-deficient individuals.

RESULTS

Secretor-positive sera from 1998 have blocking-antibody responses to NoVs isolated in 1987, 1995, and 2002.

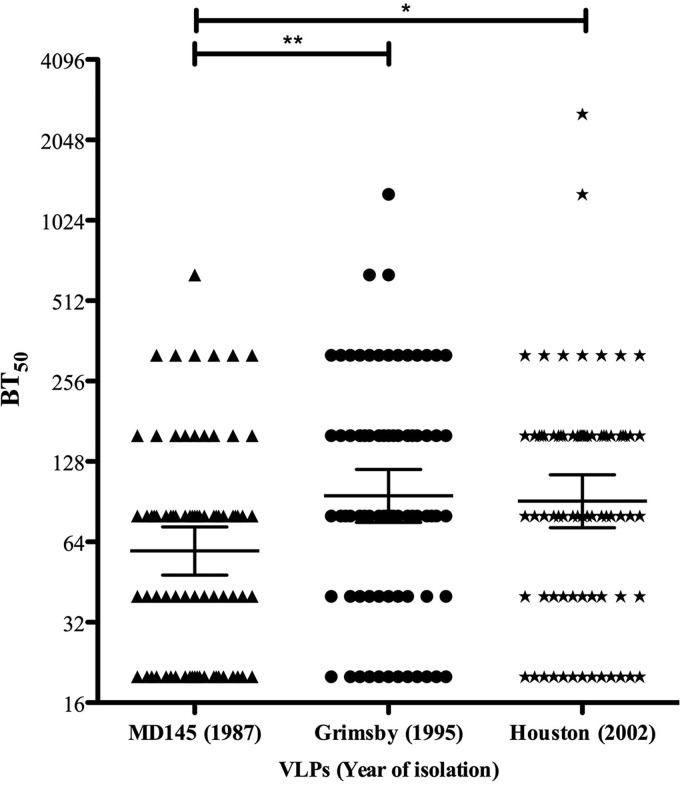

At present, it is unclear to what extent secretor-positive individuals drive norovirus evolution and receptor escape. To address this question, we took advantage of 95 secretor-, ABH-, and Lewis-characterized sera from 1998 (26, 27) and investigated whether these sera could block binding to GII.4 NoVs isolated over 3 decades before and after collection of the sera. As shown in Fig. 2, the geometric mean 50% blocking titer (BT50) values for MD145 (1987), Grimsby (1995), and Houston (2002) VLPs among secretor-positive individuals (n = 76) were 59.2 (range, 48.1 to 72.9), 95.1 (75.7 to 119.6), and 90.9 (72.3 to 114.2), respectively. Twenty-one percent (16/76), 43.5% (33/76), and 47.5% (36/76) of these secretor-positive individuals had blocking titers of ≥160 against MD145, Grimsby, and Houston VLPs, respectively. Multiple-comparison tests showed statistically significant differences in blocking titers between MD145 and Grimsby (P < 0.01) and MD145 and Houston (P < 0.05), while no significant blocking differences were observed between Grimsby and Houston VLPs (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Blocking titers in sera collected in 1998 from healthy secretor-positive individuals against 3 different NoV VLPs. The graph shows BT50s for each individual and GMTs for each group. The horizontal lines represent the geometric means, with 95% confidence intervals, for the groups. In total, 76 serum samples were analyzed. Dunn's multiple-comparison test showed significant differences between the groups. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

It is well established that secretor-negative individuals with a nonsense mutation in the FUT2 gene are almost completely resistant to infection with GII.4 viruses (9–14), but they possess serum IgG antibodies that bind to Houston GII.4 virus (26). However, none of the 19 nonsecretor sera with demonstrated NoV-specific IgG responses (GMT, 995.8 [range, 628.7 to 1577]) (26) had any blocking capacity (defined as a BT50 of ≥40) against MD145, Grimsby, or even the homolog Houston VLPs (serum IgG antibodies were measured for Houston VLPs) at the lowest serum dilution tested (1:40) (data not shown).

Blocking titers remain unchanged against GII.4 NoV isolates from 3 decades for at least 6 years.

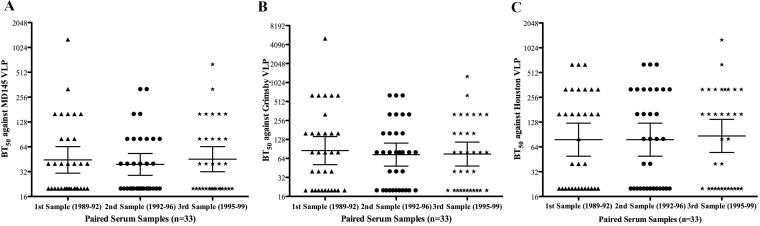

Early experimental challenge studies suggested that the duration of immunity elicited by NoV infection maybe short (15, 16), while a mathematical-modeling-based study reported that immunity to NoV gastroenteritis lasted between 4.1 and 8.7 years (28). Thus, it remains unclear how long protection lasts. To address this, we investigated the blocking titers against 3 decades of GII.4 viruses using 3 consecutive sera from each of 33 healthy individuals. Sera collected every 3 years over a 6-year period had geometric mean BT50s of 44.4 (range, 30.7 to 64.3), 39.2 (28.9 to 53.1), and 45.4 (32 to 64.4) against MD145 VLPs among sera collected between 1989 and 1992, 1992 and 1996, and 1995 and 1999, respectively (Fig. 3A). Similarly, the geometric mean BT50s against Grimsby VLPs were 85.2 (51.1 to 142.2), 73.5 (48.3 to 112.1), and 75.1 (48.6 to 116.2) (Fig. 3B), while against Houston VLPs they were 78.3 (49.3 to 124.3), 78.3 (49.5 to 124.3), and 87 (54.8 to 138.3), respectively (Fig. 3C). Thus, no significant differences in blocking titers against any VLPs were observed among the sera collected at 3 different time points. Furthermore, 12.1% (4/33), 27.3% (9/33), and 42.4% (14/33) of these individuals had BT50 values of ≥160 against MD145, Grimsby, and Houston VLPs, respectively, for all 3 serum samples collected over 6 years.

FIG 3.

Blocking-antibody titers to MD145, Grimsby, and Houston VLPs among paired serum samples. Serum BT50 values against MD145 (A), Grimsby (B), and Houston (C) VLPs among 33 tick-borne encephalitis-vaccinated individuals. From each individual, three samples were collected between 1989 and 1992, 1992 and 1996, and 1995 and 1999. The graph shows BT50s for each individual and GMTs for each group. The horizontal lines represent the geometric means, with 95% confidence intervals, for the groups. A Kruskal-Wallis test showed no significant differences in blocking titers against any VLPs among sera collected at 3 different time points.

We also investigated paired serum samples from 12 children collected 5 to 6 years apart (Table 1). Seven and 5 out of the 12 children from whom paired sera were collected over a 5-year period maintained BT50s of ≥160 for Houston and MD145 VLPs, respectively.

TABLE 1.

BT50s against MD145 and Houston VLPs in paired serum samples (n = 12) collected over a 6-year period

| Patient | Serum collection yrs | BT50 against: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GII.4 MD145 VLPs |

GII.4 Houston VLPs |

||||

| Serum 1 | Serum 2 | Serum 1 | Serum 2 | ||

| 1 | 2003, 2008 | 640 | 1,280 | 640 | 1,280 |

| 2 | 2003, 2007 | 2,560 | 640 | 1,280 | 640 |

| 3 | 2003, 2008 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| 4 | 2003, 2007 | 20 | 160 | 40 | 640 |

| 5 | 2003, 2008 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| 6 | 2003, 2008 | 320 | 640 | 320 | 640 |

| 7 | 2003, 2008 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| 8 | 2003, 2008 | 160 | 160 | 160 | 160 |

| 9 | 2003, 2007 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| 10 | 2003, 2007 | 5,120 | 320 | 5,120 | 320 |

| 11 | 2003, 2007 | 160 | 80 | 160 | 160 |

| 12 | 1998, 2003 | 80 | 640 | 160 | 1,280 |

Prepandemic sera contain blocking antibodies against pandemic GII.4 NoV.

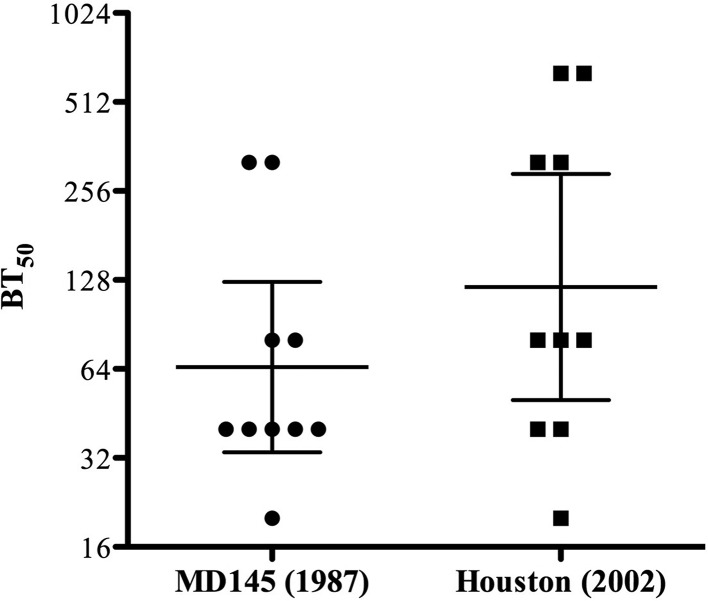

Considering the hypothesis that NoV evolution is driven partly by immune factors, there is a possibility that prepandemic sera would not contain blocking antibodies to NoVs that emerged decades later. To address this question, we took advantage of access to sera collected from 10 type 1 diabetic children during 1979. These sera were investigated for blocking titers to VLPs produced from NoVs isolated 8 to 23 years after serum collection. As shown in Fig. 4, the geometric mean BT50s for MD145 and Houston VLPs were 60.6 (range, 29.8 to 123.2) and 121.3 (50.3 to 292.6), respectively. Twenty percent (2/10) showed blocking titers of ≥160 to MD145, while 4/10 children had blocking titers of ≥160 for Houston VLPs. No significant differences in blocking efficiency were observed between MD145 and Houston VLPs (P > 0.05).

FIG 4.

Prepandemic sera from 1979 contain blocking antibodies against pandemic GII.4 viruses. The graph shows BT50s for each individual (n = 10) and GMTs for each group. The horizontal lines represent the geometric means, with 95% confidence intervals, for the groups. A Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare differences in blocking titers between MD145 and Houston VLPs (P > 0.05).

IgA-deficient individuals have high antibody-blocking titers against GII.4 NoV.

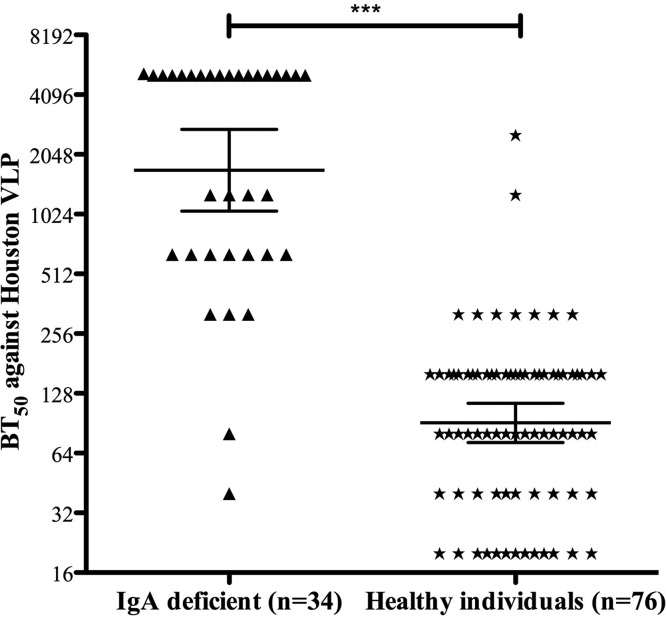

IgA deficiency (IgAD) is the most common primary immune deficiency, with an estimated frequency of 1/600 in the Caucasian population, but it may vary from 1/155 to 1/18,550, depending on ethnicity (29). The phenotypic feature of IgAD is a failure of B lymphocyte differentiation into plasma cells that produce IgA. The median IgG level among the IgA-deficient individuals investigated in the study was 13.9 mg/ml, and the mean IgA level was <0.06 mg/ml. Although the deficiency is common, there is limited information about how these individuals respond to NoV infection and whether they develop serum blocking IgG antibodies following a natural infection. To address this question, we investigated sera from 40 previously confirmed secretor and nonsecretor IgA-deficient individuals (30). All six IgA-deficient nonsecretor individuals lacked blocking antibodies (BT50 < 40) (data not shown). However, the geometric mean blocking titers among the 34 IgA-deficient secretors were 1,704 (range, 1,061 to 2,735) compared to 91 (72 to 114) among the 76 secretor-positive healthy blood donors (Fig. 5). Both the IgA-deficient and healthy blood donors were adults, with mean ages of 52.3 and 39.5 years, respectively. A statistically highly significant difference in blocking titers between secretor-positive IgA-deficient sera and healthy blood donors was observed (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 5). Of the secretor-positive IgA-deficient individuals, 94.1% (32/34) had BT50s of ≥320, while the corresponding percentage for healthy secretors was 12.2% (9/74). Furthermore, the geometric mean anti-NoV IgG titers were significantly higher among IgA-deficient individuals (P < 0.0001) than among healthy blood donors: 15,067 (12,252 to 18,530) versus 3,017 (2,642 to 3,233) (data not shown).

FIG 5.

IgA-deficient secretor-positive individuals have significantly higher blocking antibody titers than IgA-competent secretor-positive individuals. The graph shows BT50s for each individual and geometric mean titers for each group. The horizontal lines represent the geometric means, with 95% confidence intervals, for the groups. A Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare differences in blocking titers. ***; P < 0.0001.

Lack of robust blocking by sera against Sydney VLPs.

We further investigated whether sera collected from IgA-competent and IgA-deficient individuals could block binding of Sydney VLPs, the most recent pandemic NoV strain. None of the six nonsecretor sera (IgA competent and IgA deficient; 3 each) had any blocking effect on binding of Sydney VLPs to PGM (Table 2). Further, only 4 of 22 IgA-competent sera showed blocking with BT50s of ≥40, while 90.9% (20 of 22) of them had BT50 values of ≥80 for Houston VLPs. However, 10 of 14 IgA-deficient sera had BT50 values of ≥80 for Sydney VLPs. Comparison of geometric mean blocking titers among 17 healthy IgA-competent individuals against all 4 VLPs (MD145, Grimsby, Houston, and Sydney VLPs) using the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's multiple-comparison test showed that the GMTs against Sydney VLPs were significantly lower than the GMTs for the other 3 VLPs (P < 0.01). The ratios of the GMTs for the other 3 VLPs in comparison to that for Sydney VLPs was also 4.3 times higher for MD145, 7.1 times for Houston, and 8 times for Grimsby VLPs (Table 2). It was also observed that BT50s against Sydney and Houston VLPs among the 42 serum samples investigated showed a positive correlation (P < 0.0001).

TABLE 2.

IgA-competent and IgA-deficient sera show relatively low blocking antibody titers against Sydney VLPs

| Yr(s) collected | Sample ID (serum no.) | BT50d |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Houston | Sydney | ||

| 1979–1981a | 1 | 640 | 40 |

| 2 | 80 | 20 | |

| 3 | 320 | 20 | |

| 4 | 80 | 20 | |

| 5 | 80 | 20 | |

| 1998a | 1c | 20 | 20 |

| 2c | 20 | 20 | |

| 3c | 20 | 20 | |

| 4 | 320 | 80 | |

| 5 | 160 | 80 | |

| 6 | 160 | 40 | |

| 7 | 320 | 20 | |

| 8 | 80 | 20 | |

| 9 | 160 | 20 | |

| 10 | 320 | 20 | |

| 11 | 2,560 | 20 | |

| 12 | 80 | 20 | |

| 13 | 80 | 20 | |

| 14 | 160 | 20 | |

| 15 | 1,280 | 20 | |

| 16 | 40 | 20 | |

| 17 | 160 | 20 | |

| 18 | 40 | 20 | |

| 19 | 80 | 20 | |

| 20 | 160 | 20 | |

| 2009–2010b | 1c | 20 | 20 |

| 2c | 20 | 20 | |

| 3c | 20 | 20 | |

| 4 | 5,120 | 640 | |

| 5 | 5,120 | 320 | |

| 6 | 5,120 | 160 | |

| 7 | 5,120 | 160 | |

| 8 | 5,120 | 160 | |

| 9 | 5,120 | 160 | |

| 10 | 5,120 | 80 | |

| 11 | 640 | 80 | |

| 12 | 1,280 | 80 | |

| 13 | 640 | 80 | |

| 14 | 640 | 40 | |

| 15 | 40 | 20 | |

| 16 | 320 | 20 | |

| 17 | 80 | 20 | |

BT50s of IgA-competent individuals.

BT50s of IgA-deficient individuals.

Serum sample from nonsecretor individual.

Serum with a BT50 of ≤20 is considered to have no blocking capacity.

DISCUSSION

In this study, using a surrogate neutralizing blocking assay including pandemic GII.4 NoV strains that emerged over 3 decades, we found that sera collected decades before detection of any of the investigated NoV strains could block binding of pandemic NoV VLPs to PGM. Sera from children collected as early as 1979 were able to block binding to both MD145 (1987) and Houston (2002) VLPs. Twenty percent (2/10) and 40% (4/10) of the sera had BT50s of ≥160. These novel findings shed light on receptor/ligand drift and suggest, but do not prove, that receptor/ligand structures associated with NoV VLP binding to HBGA were maintained intact at least until 2002. This conclusion is supported by the work of De Rougemont and coworkers, who investigated HBGA binding of different GII.4 variants and observed that the 2004 GII.4 VLPs had stronger binding to ABH HBGAs than the pre-2002 GII.4 strains (31). Another study investigating the evolutionary dynamics of early GII.4 strains (1974 to 1991) found that the HBGA carbohydrate binding sites indeed could remain highly conserved over more than 3 decades (32).

While the HBGA binding site is highly conserved, antigenic sites are slightly less conserved areas surrounding the HBGA binding site that may undergo drift (6). Even though the Houston strain was circulating in 2002 and MD145 in 1987, they share 4 out of 6 amino acid residues in antigenic site A (Table 3), the domain suggested to be the target of blocking antibodies (5). The only difference in this region is in residues 294 and 296, where semi- and highly conserved amino acid substitutions have occurred (Table 3). The similarity between epitope A of MD145 and Houston strains might be one of the reasons why sera from 1979 are able to block binding of both VLPs (Fig. 4). Moreover, there are no amino acid differences between the two strains in site E (Table 3). Short-lived NoV immunity following experimental challenge (15, 16), together with an epochal GII.4 evolution pattern, indicates NoV immunity is more complex (17–19). How long immunity against symptomatic norovirus infection lasts is a question under debate. This could be best answered by following a cohort study for a much longer time; however, such studies require significant infrastructure and are currently lacking. A previous study conducted in the mid-1970s showed that immunity to Norwalk virus, defined as resistance to illness on repeat challenge, lasted 2 months to 2 years (16). However, there have also been contradicting reports. We observed that 12 to 44% of individuals maintained putatively protective (associated with lower risk of illness and infection) blocking titers of ≥160 (20, 23) against the 3 different VLPs investigated in this study at all 3 time points during the 6 years of serum collection. Similarly, nearly 50% of the children also showed serum BT50 values of ≥160 (7/12 for Houston and 5/12 for MD145) for the serum pairs collected over a 6-year period. This finding suggests the presence of a relatively long serologic memory of blocking antibodies against pandemic NoV strains over 3 decades. However, one cannot rule out the possibility that these individuals were reinfected (symptomatically or asymptomatically) during this period, thus restimulating the immune memory. Our observations not only confirm that NoV antibody IgG titers remain high among adults (33), but also show, for the first time, that blocking-antibody titers remain for at least 6 years, with or without restimulation. This observation is in accordance with the results of a study using a mathematical model of community NoV transmission in which it was estimated that the duration of immunity to NoV gastroenteritis was between 4.1 and 8.7 years (28).

TABLE 3.

GII.4-blocking epitopes A, D, and E

| VLPa | Amino acid at positionb: |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A |

D |

E |

||||||||||

| 294 | 296 | 297 | 298 | 368 | 372 | 393 | 394 | 395 | 407 | 412 | 413 | |

| GII.4 MD145/1987 | V | S | H | D | T | N | D | H | N | T | G | |

| GII.4 Grimsby/1995 | A | S | H | D | T | N | N | N | N | T | G | |

| GII.4 Houston/2002 | A | T | H | D | T | N | N | S | A | N | T | G |

| GII.4 Sydney/2012 | T | S | R | N | E | D | G | T | T | S | N | T |

VLPs included in the study were GII.4 MD145/1987 ([AY032605]; Camberwell_1994 GII.4 variant), GII4 Grimsby/1995 ([AJ004864]; US95_96 GII.4 variant), GII.4 Houston/2002 ([EU310927]; Lanzou_2002 GII.4 variant), and GII.4 Sydney ([JX459908]; Sydney_2012 GII.4 variant) VLPs.

Amino acid sequences of epitopes A, D, and E of four pandemic GII.4 norovirus strains investigated for serum blocking titers included in the present study.

Another important point of interest pertaining to norovirus disease is the percent susceptibility to GII.4 NoV in a population at any given time, as both host genetic factors and immune status play pivotal roles in determining susceptibility within a population (4, 8). It is well known that nonsecretors are highly resistant to GII.4 infection and hence are protected due to the nonfunctional FUT2 gene. Within secretors, serum HBGA-reactive antibodies; serum hemagglutination inhibition antibodies; serum, salivary, or fecal IgA; and virus-specific memory IgG cells have been considered to play a protective role (4). Among these, HBGA-reactive antibodies have been widely recognized to play a protective role. A challenge study among secretors showed that individuals with prechallenge serum BT50s of ≥200 against GI.1 VLPs were protected against viral gastroenteritis (20). Similar findings were also observed in another challenge study with GI.1 NV, where individuals with NoV diarrhea postchallenge were found to have significantly lower blocking titers than individuals who did not have gastroenteritis (21). In a study among individuals suffering from NoV-associated traveler's diarrhea, it was reported that none of the NoV-infected and -positive individuals had blocking titers of ≥200 in sera collected during the acute phase (23).

Building upon this background, and particularly upon the information regarding protective blocking titers, and based on host factors and immune status, we estimated what percentage of adults in a population at any given time would be susceptible to GII.4 infections. We did not include samples from diabetic children in calculating susceptibility, as type 1 diabetic individuals might have special HLA types and an immune system that may not be representative of a healthy population. Considering a BT50 of ≥160 to be protective (20, 25), we determined susceptibility rates of 57.5%, 36%, and 28.2% for MD145, Grimsby, and Houston GII.4 viruses, respectively, among healthy blood donors and tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) vaccine recipients rwho eceived the 3rd vaccine dose (which would include 20% nonsecretors, who would be resistant to GII.4 infections and innately protected). This estimate is in agreement with a review of previous Norwalk virus volunteer challenge studies involving secretor-positive individuals, which showed that 33 to 77% of the individuals responded with acute gastroenteritis upon NoV challenge (28). Similar susceptibility rates were also observed in a Swedish outbreak, where 37.5% (288/767) of individuals who visited the canteen at a company unit comprising 2,000 employees fell ill with NoV-related symptoms (34). Assuming that 20% of these 767 individuals were nonsecretors, the susceptibility rate among the secretors would be 46.9%.

Our panel of sera showed low blocking titers against the most recently emerged pandemic GII.4 strain (Sydney 2012). The PGM used in this study is a porcine gastric mucin type III, a partially purified powder containing HBGAs (i.e., histo-blood group type A, H-type 3, H-type 1, and Lewis b antigens) and about 1% sialic acids (35). To evaluate the potential blocking effect, the Sydney VLPs were screened against a panel of sera from IgA-competent and IgA-deficient individuals representing low and high BT50s against other VLPs. Interestingly, no sera from IgA-competent individuals had BT50s of >80, while only 6 of 14 IgA-deficient sera had BT50s of ≥160. One possible explanation for the most modest blocking titers against the Sydney NoV strain could be that the strain is structurally very different from the earlier pandemic GII.4 NoVs (7). Recently, a few studies have reported blocking of Sydney VLP binding to carbohydrates and saliva, but the HBGA ligands involved are not yet defined. Thus, a Norwalk GI.1 challenge study reported that sera from some individuals collected in 2008 were able to block binding of Sydney VLPs to HBGA (36). It was further observed that the blocking effect did not last long, and BT50 values against Sydney VLPs declined within 6 months after the Norwalk GI.I NoV challenge. Another study showed that convalescent-phase sera from the 2009 GII.4 NoV outbreak were able to block Sydney 2012 VLP binding to PGM (7). However, in 7 out of the 8 sera screened, significantly higher serum concentrations were needed to block the Sydney 2012 GII.4 NoV VLPs than for the outbreak 2009 GII.4 NoV strain VLPs. Similarly, in our study, only 4 out of 22 secretor-positive healthy blood donors had detectable blocking antibodies (at 1/40 serum dilution) against Sydney VLPs, and 10/14 IgA-deficient individuals had a BT50 value of ≥80. The detection of low blocking-antibody titers against Sydney 2012 GII.4 VLPs among IgA-competent individuals might also be due to differences in the study design, since in the present study, serum blocking efficiency against the 4 VLPs was investigated in healthy individuals and not in NoV-challenged or -infected individuals.

To investigate a rationale for the immune evasion by the Sydney 2012 GII.4 VLP strain, the sequences of the capsid proteins of the strains used in this study were compared. Simple amino acid alignment revealed that the VLPs most distant in time, the MD145 1978 and Sydney 2012 GII.4 VLPs, showed only 91.8% amino acid identity.

Most interesting from a biological point of view, and perhaps explaining the observed differences in blocking titers found in this study, the alignment also revealed that the GII.4 NoV strains used in this study have major changes in antigenic epitopes A (amino acids [aa] 294, 296 to 298, 368, and 372), D (aa 393 to 395), and E (aa 407, 412, and 413), as shown in Table 3 (6, 7, 18, 37–39). Previous studies have reported epitope A to be highly immunodominant and suggested it was the target of blocking antibodies against early strains (7, 38). Interestingly, MD145 1987, Grimsby 1995, and Houston 2002 share 4 common residues (H297, D298, T368, and N372), whereas the Sydney strain has different amino acids in all these positions (H297R, D298N, T368E, and N372D) (Table 3). The substitution of only 2 amino acids in epitope A (P294T and A368E) has been suggested to be the cause of low BT50 efficiency of the 2009 GII.4 convalescent outbreak sera to block Sydney 2012 GII.4 VLP binding to PGM (7). Altogether, the data support the hypothesis that the Sydney strain might indeed have escaped immune recognition by blocking antibodies, which explains the low blocking titers observed in this study. Epitope D has been associated with the alteration of HBGA binding affinity (6, 37), while in epitope E, all the strains except Sydney are identical and share the 3 residues (N407, T412, and G413) in this site (Table 3), supporting the experimental results reported here that the Sydney strain is distinctly different from the other GII.4 strains.

Despite being a common primary immune deficiency in the Caucasian population (29), very little is known regarding how IgA-deficient individuals respond to NoV infection. For the first time, we show that IgA-deficient individuals not only have blocking titers against three pandemic NoV strains, but most interestingly, the blocking titers were significantly higher among IgA-deficient secretors (GMT, 1704) than among healthy blood donors (GMT, 90.9) (P < 0.0001). This new information complements a challenge study investigating the humoral response to NoV infection, which found a protective role of mucosal IgA in secretor-positive individuals after exposure to Norwalk virus (GI.1 NoV) (40). Moreover, the protective role of IgA was also found to be associated with protection against a GI.1 NoV infection (41). In another study, IgA purified from convalescent-phase sera of GI.1 NoV-challenged individuals was shown to block binding of NoV VLPs to PGM (42). Further, a recent study showed that the IgA isotype in human B cells encoding norovirus-specific monoclonal antibodies could frequently block binding of VLPs to HBGA in comparison to antibodies having IgG specificity (43).

Thus, both serum IgA and IgG can block binding of NoV to HBGA. The significantly higher blocking titer among the IgA-deficient individuals than among IgA-competent individuals is most likely due to compensatory mechanisms. It has previously been shown that IgA-deficient individuals develop significantly higher IgG antibody titers to rotavirus than IgA-competent individuals (44). Since 32/34 secretor-positive IgA-deficient individuals had BT50 values of ≥320 against Houston VLPs, it could be speculated that the protective titers among IgA-deficient individuals might be much higher than among healthy individuals. Further studies could be directed at identifying the protective blocking IgG titer among such immunodeficient individuals.

In conclusion, the present study shows that prepandemic sera contain blocking antibodies to pandemic GII.4 NoVs that emerged decades later and that blocking titers can remain unchanged for at least 6 years against GII.4 NoVs isolated over 3 decades. It is also worth noting that none of the nonsecretors had measurable blocking antibody against any of the GII.4 variants tested, which is consistent with their resistance to infection. Furthermore, we show that IgA-deficient individuals have high serum antibody-blocking titers against GII.4 NoV. Lack of robust HBGA-blocking capacity of sera against the Sydney strain isolated in 2012 may be a condition of its rapid global emergence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Serum samples and study design.

In total, 268 serum samples collected between 1979 and 2010 were included in the study (Fig. 1). These samples were part of different studies and were both paired and unpaired. Briefly, 95 serum samples from blood donors collected in 1998 were included in the study. The mean age of the donors was 39.5 ± 10.3 years. These individuals had previously been screened for their secretor, Lewis, and ABO status. Eighty percent (76/95) of these individuals were secretor positive (26, 27). In addition, 33 paired serum samples from individuals participating in a TBE vaccination study in Stockholm, Sweden, were also analyzed. Serum samples were collected at 3 time points; the first were collected from 1989 to 1992 (donors aged 56.1 ± 12.9 years), the second 3 years later, and the third sample between 1995 and 1999 (45). Thirty-four serum samples collected from children with type 1 diabetes (aged 9.7 ± 3.2 years at the time of the 1st sample collection) were also included: 12 paired sera collected at 2 time points (the second serum samples 5 years later) and 10 unpaired old serum samples collected between 1979 and 1981 were included in the study. Additionally, sera from 40 IgA-deficient individuals (34 secretors and 6 nonsecretors) collected between 2009 and 2010 were included (30). The average age of these individuals was 52.3 ± 19.4 years. The samples used in the study were anonymous and were part of previously ethically approved studies (Ethical Committee Dnr 89:12 and Medical Faculty, Goteborg University, Goteborg, Sweden).

NoV VLP production.

Four different GII.4 recombinant VLPs, each representative of a different lineage and having a time-ordered emergence globally, were included in the study (Fig. 1): MD145 (isolated as early as 1987 [AY032605]), Grimsby (isolated in 1995 [AJ004864]), Houston (isolated in 2002 [EU310927]), and Sydney (isolated in 2012 [JX459908]). Amino acid residues in the important antigenic sites A, D, and E for the included VLPs are shown in Table 3. The VLPs used in the study were expressed in a baculovirus system. Grimsby, Houston, and Sydney VLP preparations were analyzed for purity by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Coomassie staining (which must be >90% to be used). The structural integrity was documented by electron microscopy, and the VLP protein concentration was determined by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (26, 46), while MD145 was purified as described previously (47).

NoV antibody titers in serum samples from IgA-deficient individuals.

NoV-specific IgG antibody titers in serum samples were determined using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as previously described (26). Briefly, 100 μl/well of 0.5-μg/ml Houston VLPs diluted in coating buffer (0.05 mol/liter sodium carbonate [pH 9.5 to 9.7]) was added to 96-microwell ELISA plates (Thermo Scientific; MaxiSorp) and incubated overnight at 4°C. The next morning, the plates were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h at 37°C. Each step was followed by 5 washes with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.3) (PBS). Twofold serially diluted serum samples (100 μl/well) were added in dilution buffer comprised of PBS, 0.5% BSA, and 0.05% Tween 20, and then the ELISA plate was incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Next, 100 μl/well of 1:10,000-diluted goat anti-human IgG horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibody (Bio-Rad; 1721033) was added and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The plates were developed using 100 μl/well of Ultra 1-Step Ultra TMB ELISA HRP substrate solution (Thermo Fischer). After 10 min, the reaction was stopped by adding 100 μl/well of 2 N sulfuric acid, and the absorbance of the wells was read at 450 nm. The mean absorbance value of negative controls (without serum) plus 2 standard deviations (SD) was used as the cutoff value.

Determination of serum blocking titers against binding of VLPs to pig gastric mucin.

VLP-PGM serum blocking experiments were performed essentially as previously described (18). Briefly, Thermo Scientific MaxiSorp 96-well plates were coated with pig gastric mucin (Sigma-Aldrich; 10 μg/ml in PBS, pH 7.3) for 4 h at room temperature and subsequently blocked overnight at 4°C with PBS containing 5% dry milk and 0.05% Tween. Next, 2-fold serially diluted sera (starting dilution, 1:40) were mixed with an equal volume of VLPs (at concentrations of 0.06 μg/ml for Grimsby and Houston, 0.08 μg/ml for MD145, and 0.3 μg/ml for Sydney VLPs) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Afterward, the VLP-serum mixture was added to the pig gastric mucin-coated plate for 1 h at room temperature, followed by 100 μl/well of rabbit anti-GII.3 norovirus serum (1:1,000 dilution) and an additional incubation for 1 h. Following five washes, 100 μl/well of goat anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (Bio-Rad; 1706515) diluted 1:20,000 was added, followed by incubation for 1 h at room temperature. The plates were developed using 100 μl/well of Ultra 1-Step Ultra TMB ELISA HRP substrate solution (Thermo Fisher). After 10 min, the reaction was stopped by adding 100 μl/well of 2 N sulfuric acid, and the absorbance of the wells was read at 450 nm (optical density at 45 nm [OD450]). Washing after each step was performed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20, and the dilution buffer was comprised of PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 5% dry milk. The BT50, was defined as the serum dilution at which the OD450 value was 50% of that of the positive control (VLPs only). A BT50 value of 20 was assigned to samples that did not show a 50% drop in OD450 in comparison to the positive control at the lowest serum dilution tested (1:40). A BT50 value of ≥160 was considered to be protective against acute norovirus gastroenteritis (20, 25).

Statistical analysis.

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0a Macintosh version (GraphPad Software, Inc.). The Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn′s multiple-comparison tests were used to compare differences in serum blocking titers against the three different VLPs. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare BT50 values between groups among sera collected prior to the emergence of the reference strains. All reported P values are 2 sided, and P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Swedish Research Council grants to L.S. (320301) and G.L. (8266) and partly by a grant on gastrointestinal viruses and mucosal vaccines to L.S. and G.L. from the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Noel JS, Fankhauser RL, Ando T, Monroe SS, Glass RI. 1999. Identification of a distinct common strain of “Norwalk-like viruses” having a global distribution. J Infect Dis 179:1334–1344. doi: 10.1086/314783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ettayebi K, Crawford SE, Murakami K, Broughman JR, Karandikar U, Tenge VR, Neill FH, Blutt SE, Zeng XL, Qu L, Kou B, Opekun AR, Burrin D, Graham DY, Ramani S, Atmar RL, Estes MK. 2016. Replication of human noroviruses in stem cell-derived human enteroids. Science 353:1387–1393. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones MK, Watanabe M, Zhu S, Graves CL, Keyes LR, Grau KR, Gonzalez-Hernandez MB, Iovine NM, Wobus CE, Vinje J, Tibbetts SA, Wallet SM, Karst SM. 2014. Enteric bacteria promote human and mouse norovirus infection of B cells. Science 346:755–759. doi: 10.1126/science.1257147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramani S, Estes MK, Atmar RL. 2016. Correlates of protection against norovirus infection and disease; where are we now, where do we go? PLoS Pathog 12:e1005334. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Debbink K, Donaldson EF, Lindesmith LC, Baric RS. 2012. Genetic mapping of a highly variable norovirus GII.4 blockade epitope: potential role in escape from human herd immunity. J Virol 86:1214–1226. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06189-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Debbink K, Lindesmith LC, Donaldson EF, Baric RS. 2012. Norovirus immunity and the great escape. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002921. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Debbink K, Lindesmith LC, Donaldson EF, Costantini V, Beltramello M, Corti D, Swanstrom J, Lanzavecchia A, Vinje J, Baric RS. 2013. Emergence of new pandemic GII.4 Sydney norovirus strain correlates with escape from herd immunity. J Infect Dis 208:1877–1887. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le Pendu J, Ruvoen-Clouet N, Kindberg E, Svensson L. 2006. Mendelian resistance to human norovirus infections. Semin Immunol 18:375–386. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hutson AM, Airaud F, LePendu J, Estes MK, Atmar RL. 2005. Norwalk virus infection associates with secretor status genotyped from sera. J Med Virol 77:116–120. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thorven M, Grahn A, Hedlund KO, Johansson H, Wahlfrid C, Larson G, Svensson L. 2005. A homozygous nonsense mutation (428G→A) in the human secretor (FUT2) gene provides resistance to symptomatic norovirus (GGII) infections. J Virol 79:15351–15355. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.24.15351-15355.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kindberg E, Akerlind B, Johnsen C, Knudsen JD, Heltberg O, Larson G, Bottiger B, Svensson L. 2007. Host genetic resistance to symptomatic norovirus (GGII.4) infections in Denmark. J Clin Microbiol 45:2720–2722. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00162-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bucardo F, Kindberg E, Paniagua M, Grahn A, Larson G, Vildevall M, Svensson L. 2009. Genetic susceptibility to symptomatic norovirus infection in Nicaragua. J Med Virol 81:728–735. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rydell GE, Kindberg E, Larson G, Svensson L. 2011. Susceptibility to winter vomiting disease: a sweet matter. Rev Med Virol 21:370–382. doi: 10.1002/rmv.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nordgren J, Sharma S, Kambhampati A, Lopman B, Svensson L. 2016. Innate resistance and susceptibility to norovirus infection. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005385. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson PC, Mathewson JJ, DuPont HL, Greenberg HB. 1990. Multiple-challenge study of host susceptibility to Norwalk gastroenteritis in US adults. J Infect Dis 161:18–21. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parrino TA, Schreiber DS, Trier JS, Kapikian AZ, Blacklow NR. 1977. Clinical immunity in acute gastroenteritis caused by Norwalk agent. N Engl J Med 297:86–89. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197707142970204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cannon JL, Lindesmith LC, Donaldson EF, Saxe L, Baric RS, Vinje J. 2009. Herd immunity to GII.4 noroviruses is supported by outbreak patient sera. J Virol 83:5363–5374. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02518-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindesmith LC, Beltramello M, Donaldson EF, Corti D, Swanstrom J, Debbink K, Lanzavecchia A, Baric RS. 2012. Immunogenetic mechanisms driving norovirus GII.4 antigenic variation. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002705. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siebenga JJ, Vennema H, Renckens B, de Bruin E, van der Veer B, Siezen RJ, Koopmans M. 2007. Epochal evolution of GGII.4 norovirus capsid proteins from 1995 to 2006. J Virol 81:9932–9941. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00674-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atmar RL, Bernstein DI, Harro CD, Al-Ibrahim MS, Chen WH, Ferreira J, Estes MK, Graham DY, Opekun AR, Richardson C, Mendelman PM. 2011. Norovirus vaccine against experimental human Norwalk virus illness. N Engl J Med 365:2178–2187. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1101245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reeck A, Kavanagh O, Estes MK, Opekun AR, Gilger MA, Graham DY, Atmar RL. 2010. Serological correlate of protection against norovirus-induced gastroenteritis. J Infect Dis 202:1212–1218. doi: 10.1086/656364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harrington PR, Lindesmith L, Yount B, Moe CL, Baric RS. 2002. Binding of Norwalk virus-like particles to ABH histo-blood group antigens is blocked by antisera from infected human volunteers or experimentally vaccinated mice. J Virol 76:12335–12343. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.23.12335-12343.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ajami NJ, Kavanagh OV, Ramani S, Crawford SE, Atmar RL, Jiang ZD, Okhuysen PC, Estes MK, DuPont HL. 2014. Seroepidemiology of norovirus-associated travelers' diarrhea. J Travel Med 21:6–11. doi: 10.1111/jtm.12092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malm M, Uusi-Kerttula H, Vesikari T, Blazevic V. 2014. High serum levels of norovirus genotype-specific blocking antibodies correlate with protection from infection in children. J Infect Dis 210:1755–1762. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atmar RL, Bernstein DI, Lyon GM, Treanor JJ, Al-Ibrahim MS, Graham DY, Vinje J, Jiang X, Gregoricus N, Frenck RW, Moe CL, Chen WH, Ferreira J, Barrett J, Opekun AR, Estes MK, Borkowski A, Baehner F, Goodwin R, Edmonds A, Mendelman PM. 2015. Serological correlates of protection against a GII.4 norovirus. Clin Vaccine Immunol 22:923–929. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00196-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larsson MM, Rydell GE, Grahn A, Rodriguez-Diaz J, Akerlind B, Hutson AM, Estes MK, Larson G, Svensson L. 2006. Antibody prevalence and titer to norovirus (genogroup II) correlate with secretor (FUT2) but not with ABO phenotype or Lewis (FUT3) genotype. J Infect Dis 194:1422–1427. doi: 10.1086/508430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larson G, Svensson L, Hynsjo L, Elmgren A, Rydberg L. 1999. Typing for the human Lewis blood group system by quantitative fluorescence-activated flow cytometry: large differences in antigen presentation on erythrocytes between A(1), A(2), B, O phenotypes. Vox Sang 77:227–236. doi: 10.1046/j.1423-0410.1999.7740227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simmons K, Gambhir M, Leon J, Lopman B. 2013. Duration of immunity to norovirus gastroenteritis. Emerg Infect Dis 19:1260–1267. doi: 10.3201/eid1908.130472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang N, Hammarstrom L. 2012. IgA deficiency: what is new? Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 12:602–608. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3283594219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nordgren J, Sharma S, Bucardo F, Nasir W, Gunaydin G, Ouermi D, Nitiema LW, Becker-Dreps S, Simpore J, Hammarstrom L, Larson G, Svensson L. 2014. Both Lewis and secretor status mediate susceptibility to rotavirus infections in a rotavirus genotype-dependent manner. Clin Infect Dis 59:1567–1573. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Rougemont A, Ruvoen-Clouet N, Simon B, Estienney M, Elie-Caille C, Aho S, Pothier P, Le Pendu J, Boireau W, Belliot G. 2011. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of the binding of GII.4 norovirus variants onto human blood group antigens. J Virol 85:4057–4070. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02077-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bok K, Abente EJ, Realpe-Quintero M, Mitra T, Sosnovtsev SV, Kapikian AZ, Green KY. 2009. Evolutionary dynamics of GII.4 noroviruses over a 34-year period. J Virol 83:11890–11901. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00864-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hinkula J, Ball JM, Lofgren S, Estes MK, Svensson L. 1995. Antibody prevalence and immunoglobulin IgG subclass pattern to Norwalk virus in Sweden. J Med Virol 47:52–57. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890470111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zomer TP, De Jong B, Kuhlmann-Berenzon S, Nyren O, Svenungsson B, Hedlund KO, Ancker C, Wahl T, Andersson Y. 2010. A foodborne norovirus outbreak at a manufacturing company. Epidemiol Infect 138:501–506. doi: 10.1017/S0950268809990756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tian P, Jiang X, Zhong W, Jensen HM, Brandl M, Bates AH, Engelbrektson AL, Mandrell R. 2007. Binding of recombinant norovirus like particle to histo-blood group antigen on cells in the lumen of pig duodenum. Res Vet Sci 83:410–418. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Czako R, Atmar RL, Opekun AR, Gilger MA, Graham DY, Estes MK. 2015. Experimental human infection with Norwalk virus elicits a surrogate neutralizing antibody response with cross-genogroup activity. Clin Vaccine Immunol 22:221–228. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00516-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karst SM, Baric RS. 2015. What is the reservoir of emergent human norovirus strains? J Virol 89:5756–5759. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03063-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindesmith LC, Costantini V, Swanstrom J, Debbink K, Donaldson EF, Vinje J, Baric RS. 2013. Emergence of a norovirus GII.4 strain correlates with changes in evolving blockade epitopes. J Virol 87:2803–2813. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03106-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindesmith LC, Debbink K, Swanstrom J, Vinje J, Costantini V, Baric RS, Donaldson EF. 2012. Monoclonal antibody-based antigenic mapping of norovirus GII.4-2002. J Virol 86:873–883. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06200-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lindesmith L, Moe C, Marionneau S, Ruvoen N, Jiang X, Lindblad L, Stewart P, LePendu J, Baric R. 2003. Human susceptibility and resistance to Norwalk virus infection. Nat Med 9:548–553. doi: 10.1038/nm860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramani S, Neill FH, Opekun AR, Gilger MA, Graham DY, Estes MK, Atmar RL. 2015. Mucosal and cellular immune responses to Norwalk virus. J Infect Dis 212:397–405. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lindesmith LC, Beltramello M, Swanstrom J, Jones TA, Corti D, Lanzavecchia A, Baric RS. 2015. Serum immunoglobulin A cross-strain blockade of human noroviruses. Open Forum Infect Dis 2:ofv084. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofv084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sapparapu G, Czako R, Alvarado G, Shanker S, Prasad BV, Atmar RL, Estes MK, Crowe JE Jr. 2016. Frequent use of the IgA isotype in human B cells encoding potent norovirus-specific monoclonal antibodies that block HBGA binding. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005719. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Istrate C, Hinkula J, Hammarstrom L, Svensson L. 2008. Individuals with selective IgA deficiency resolve rotavirus disease and develop higher antibody titers (IgG, IgG1) than IgA competent individuals. J Med Virol 80:531–535. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vene S, Haglund M, Lundkvist A, Lindquist L, Forsgren M. 2007. Study of the serological response after vaccination against tick-borne encephalitis in Sweden. Vaccine 25:366–372. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jiang X, Wang M, Graham DY, Estes MK. 1992. Expression, self-assembly, and antigenicity of the Norwalk virus capsid protein. J Virol 66:6527–6532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bok K, Parra GI, Mitra T, Abente E, Shaver CK, Boon D, Engle R, Yu C, Kapikian AZ, Sosnovtsev SV, Purcell RH, Green KY. 2011. Chimpanzees as an animal model for human norovirus infection and vaccine development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:325–330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014577107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]