ABSTRACT

In visceral leishmaniasis (VL), the host macrophages generate oxidative stress to destroy the pathogen, while Leishmania combats the harmful effect of radicals by redox homeostasis through its unique trypanothione cascade. Leishmania donovani ascorbate peroxidase (LdAPx) is a redox enzyme that regulates the trypanothione cascade and detoxifies the effect of H2O2. The absence of an LdAPx homologue in humans makes it an excellent drug target. In this study, the homology model of LdAPx was built, including heme, and diverse compounds were prefiltered (PAINS, ADMET, and Lipinski's rule of five) and thereafter screened against the LdAPx model. Compounds having good affinity in terms of the Glide XP (extra precision) score were clustered to select diverse compounds for experimental validation. A total of 26 cluster representatives were procured and tested on promastigote culture, yielding 12 compounds with good antileishmanial activity. Out of them, six compounds were safer on the BALB/c peritoneal macrophages and were also effective against disease-causing intracellular amastigotes. Three out of six compounds inhibited recombinant LdAPx in a noncompetitive manner and also demonstrated partial reversion of the resistance property in an amphotericin B (AmB)-resistant strain, which may be due to an increased level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and decrease of glutathione (GSH) content. However, inhibition of LdAPx in resistant parasites enhanced annexin V staining and activation of metacaspase-like protease activity, which may help in DNA fragmentation and apoptosis-like cell death. Thus, the present study will help in the search for specific hits and templates of potential therapeutic interest and therefore may facilitate the development of new drugs for combination therapy against VL.

KEYWORDS: ascorbate peroxidase, phylogenetic analysis, virtual screening and docking, apoptosis, inhibitors, leishmania, enzymatic assay

INTRODUCTION

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is one of the fatal neglected parasitic diseases and is caused by the flagellated protozoan parasite of the genus Leishmania and family Trypanosomatidae (1). The promastigote forms are transmitted to the host blood through the bite of phlebotomine sand flies (vector) and are differentiated into amastigotes in macrophages, resulting in hepatosplenomegaly (2). According to a WHO report from 2015, approximately 30,000 annual deaths and over 1.3 million new cases were estimated. The countries most affected by VL were noted as Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, India, South Sudan, and Sudan (3). The most commonly affected states are West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, and Bihar in the Indian subcontinent (4, 5).

Despite increased mortality and deteriorated health conditions, limited options for treatment are of serious concern (6). Until now, there has not been an effective vaccine; besides the available marketed drugs, including the important antifungal drug amphotericin B (AmB) and its newer formulation (AmBisome), miltefosine and pentavalent antimonials have either severe adverse effects or problems with resistance. Amphotericin B (deoxycholate) is expensive and also requires long-term treatment, while its liposomal formulations AmBisome (Gilead Sciences, USA), Abelcet, and Amphocil proved to have much better therapeutic effects but still are expensive and often unaffordable (7), so there is an urgent need for the development of safer, inexpensive, and effective novel chemical moieties as antileishmanial drugs.

In order to design inhibitors, the search for differentiable targets has been made easy and approachable with Leishmania whole-genome-sequencing (8). Ascorbate peroxidase (APx [EC 1.11.1.11]) is a unique and attractive therapeutic target of the trypanothione pathway that regulates oxidative stress in the Leishmania parasite, which is devoid of catalase and glutathione (GSH) peroxidases (9). APx is the first heme-containing class I peroxidase, an integral enzyme of the glutathione-ascorbate cycle that catalyzes the detoxification of hydroperoxide (H2O2) through a one-electron transfer mechanism (10) and keeps the parasite free from cell damage. Absence of APx increased metacyclogenesis and apoptosis in Leishmania major (11). A single copy of the Leishmania major APx gene is vital for H2O2 detoxification either by endogenous processes or from external sources, such as infected macrophages or drug metabolism by Leishmania (12). The level of APx was elevated by ∼2.1- and ∼2.5-fold on exposure to reactive oxygen species (ROS [menadione and SNAP]) and a reactive nitrogen species (RNS)-producing agent, respectively, which shows APx has a crucial role in the survival of the Leishmania parasite (13). Hence, the importance of this enzyme in the survival of Leishmania makes APx a potential therapeutic target to approach for structure-based drug development.

Structure-based drug design (SBDD) is a cost-effective and time-saving approach that essentially requires a three-dimensional (3D) structure of a receptor and a compound library for screening a large chemical database. Protein structure can be determined experimentally by X-ray crystallography and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) or in silico by homology modeling and threading approaches (14, 15). Compounds can be collected from online commercial vendors, from the literature, or through in-house library design by different types of software. Many people have followed this methodology for finding inhibitors against Leishmania donovani using Discovery Studio, Schrödinger, FlexX, etc. (16, 17).The major objectives of the present work were to obtain molecular insight into the structure of Leishmania donovani APx (LdAPx) and to identify a structure-based inhibitor that can inhibit LdAPx and may be helpful in developing newer therapeutics.

In the present work, a homology model of LdAPx was built, including heme, which is an essential cofactor required for biological functioning of the enzyme. The model consists of an alpha-orthogonal bundle with two peroxidase domains. The compound library was enumerated using millions of synthetic and natural compounds from the Asinex and ZINC compound databases. Compounds were sorted based on different screening filters like “promiscuous,” “absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion” “(ADME),” “Lipinski's rule of five,” and “toxicity.” Compounds satisfying these filters were screened against the LdAPx model and were further sorted based on docking score and binding free energy. The sorted compounds were clustered and diversified to procure a few representatives for in vitro testing. The procured compounds were tested by MTT [3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2.5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide] assay on promastigotes, and the confirmed inhibitors were further examined on disease-causing amastigotes, developed using murine peritoneal macrophages. The screened inhibitors were further investigated by enzymatic assay to establish a correlation between in silico and in vitro results. The confirmed hits obtained after the cell-based and enzymatic assays were inspected to observe the intracellular ROS level, glutathione (GSH) content, and mitochondrial peroxidase activities of both amphotericin B (AmB)-sensitive and -resistant parasites. Furthermore the mode of parasite death was investigated in the presence of LdAPx inhibitor in AmB-sensitive and -resistant parasites. Thus, the ultimate hits in this study may be future antileishmanial inhibitors and may also act as the template for further drug development.

RESULTS

Phylogenetic analysis and 3D modeling.

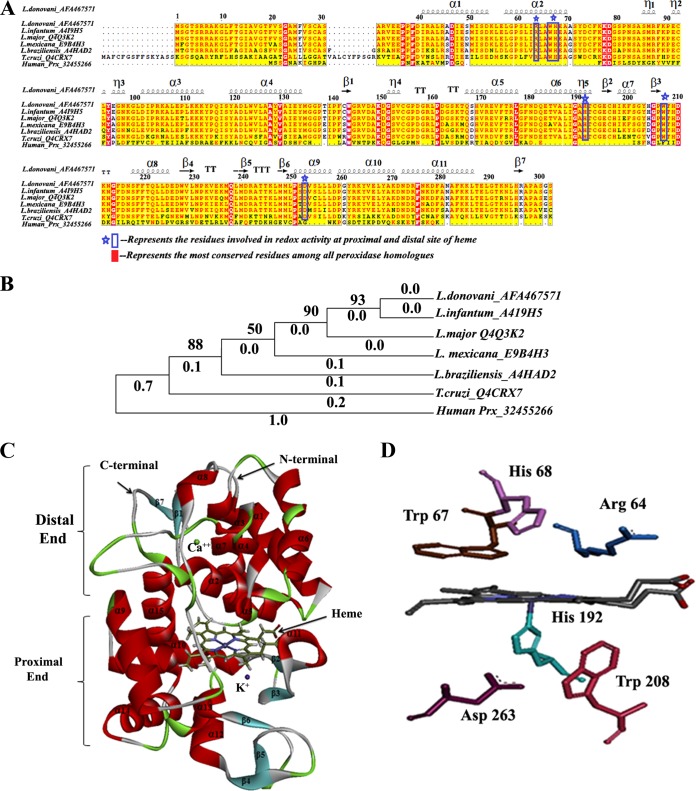

The phylogenetic relationships of LdAPx with respect to other Leishmania strains, Trypanosoma, and human peroxidase (Prx) showed that the input sequences are segregated into two major clusters, with all members of the kinetoplastid family in one cluster and human peroxidase (Prx) in the other. The phylogeny indicated that L. donovani is the nearest neighbor of Leishmania infantum, having 100% sequence identity, while the L. major, Leishmania mexicana, Leishmania braziliensis, and Trypanosoma cruzi sequences have 96%, 92%, 85%, and 61% sequence identities, respectively. Multiple sequence analysis (MSA) showed conserved catalytic residues among all members of the kinetoplastid family, which give clues to the similar patterns of inhibitor binding shown in Fig. 1A, while the human peroxidase is quite dissimilar or distantly related to Leishmania APx, having the greatest branch length (1.0), as shown in Fig. 1B.

FIG 1.

MSA and phylogenetic relationships among LdAPx and other kinetoplastid species' APx and human peroxidase and homology modeling and active site residues of LdAPx model structure. (A) The protein sequences were aligned by the ClustalW algorithm using the Network Protein Sequence Analysis (NPS@) online tool, and aligned sequences were graphically viewed by the Easy Sequencing in PostScript (ESPript) program. (B) Phylogenetic analysis was conducted on ClustalW-aligned sequences using the Poisson model method of MEGA v5.2 by the NJ method and bootstrap analysis (1,000 repeats). The clades of Leishmania species are neighbor to T. cruzi and unrelated to human peroxidase (branch length of 1.0). Panel C depicts the 3D model of LdAPx, including the heme cofactor, built by Prime (Schrödinger v9.6). The proximal and distal peroxidase domains along with the N- and C-terminal regions and secondary structure are labeled. (D) The active site residues at the proximal and distal ends of LdAPx are shown.

We built the 3D model of LdAPx by comparative modeling using Leishmania major peroxidase as the template (PDB code 3RIV), with a resolution of 1.76 Å, 96% sequence identity, 88% query coverage, and an E value of 0.0. Different models of LdAPx were built by Prime, Discovery Studio, Swiss-Model, Geno_3d, and Modeler. Among all the models generated by different servers/tools, the model built by Prime (Schrödinger v9.6) was considered to be reliable based on the lowest DOPE (discrete optimized protein energy) score (−34,002.30), as shown in Fig. S1A in the supplemental material. Heme cofactor was included in the model as it regulates the oxidative activity of LdAPx, and this was justified by the interaction energy to be 102.655 kcal/mol, as calculated by CDOCKER. The Procheck analysis for the backbone conformations showed no amino acid residues in disallowed and generously allowed regions, whereas 93.0% and 7.0% of residues were there in the most favored and additional allowed regions, respectively, depicting the compatibility of each LdAPx residue, as shown by the Ramachandran plot in Fig. S1B. The ProSA Z-scores of the query model and template were found to be −9.27 and −8.69, respectively, which are very close to the value of the experimentally solved structure (template), suggesting that the obtained model is reliable. The ProSA energy profile calculated for the LdAPx model is shown in Fig. S1C. The Dali result illustrates the root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the model with the template, which was found to be 0.7 Å, validating good structural overlap between the template and model, as shown in Fig. S1D. Hence, this model was used for further structure-based virtual screening (SBVS) and docking studies.

The 3D structure of LdAPx consisted mainly of an alpha-orthogonal bundle, in agreement with the template having two peroxidase domains responsible for detoxifying the effect of H2O2. The distal peroxidase domain located at the N terminus is delineated by residues Met 1 to Leu 161 and Phe 284 to Ser 303, while the proximal C-terminal peroxidase domain (P162 to A283) extends from the core region of the protein, where it folds into the two-domain part primarily. The overall 3D structure of LdAPx consists of 15 α helices, 16 turns, 7 strands, and 3 β hairpins as shown in Fig. 1C. Since Arg 64, Trp 67, and His 68 are well-known binding residues of APx, located at the δ-heme edge (18), the binding site for LdAPx was built by selecting these residues at the distal end by the grid method with 20 Å of workspace using Schrödinger v9.6 and with the centroid of the site model having dimensions of x = −15.54, y = 13.45, and z = −31.08 as the binding area for the docking protocol shown in Fig. 1D.

Diverse collection.

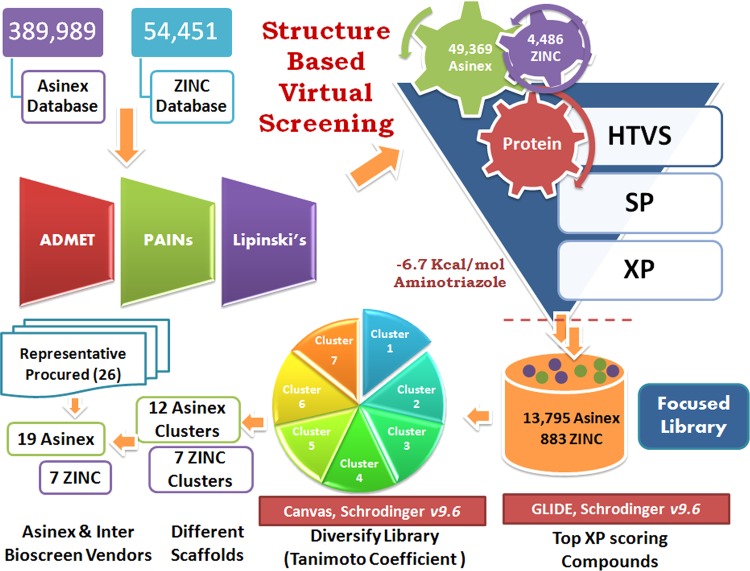

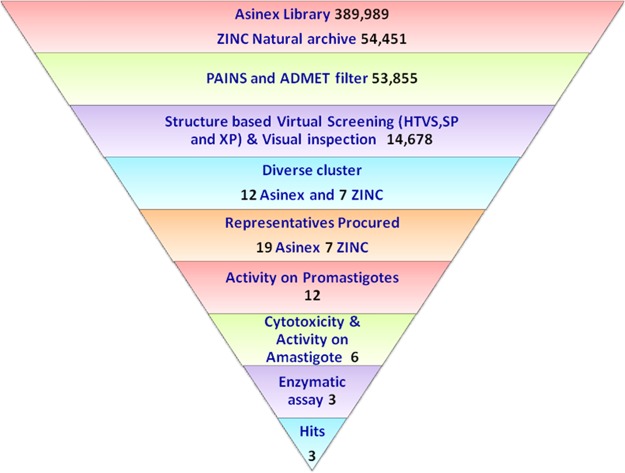

Library diversity is an essential concern in terms of molecular structure and, more importantly, function, so we designed the library with approximately 450,000 of diverse compounds that includes 113,962 Platinum, 205,883 Gold, and 70,144 Elite compounds from the Asinex data set and 54,451 compounds from the ZINC Natural subset. The diverse libraries were filtered by the Lipinski rule of five using Qik Prop (Schrödinger v9.6); these sorted compounds were subjected to ADMET analysis using Discovery Studio v2.5, and promiscuous compounds were removed by the False Positive Remover server. Totals of 13,567, 26,658, 9,144, and 4,486 compounds from the Asinex Platinum, Gold, and Elite subsets and the ZINC Natural subset were obtained, respectively, after filtering the library based on the filters described above. The promiscuous compounds removed are benzpyrenone, toxoflavin, curcumin, rhodanine, phenol sulfonamide, quinine, and catechol-containing scaffolds as these reactive groups may covalently bind with the metal ion or may react with the protein in a nonspecific manner. This curated library was further subjected to virtual screening (VS) (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Workflow of the computational screening of chemical databases (Asinex and ZINC) at the HTVS, SP, and XP levels followed by Tanimoto clustering of the top-ranked solutions. The numbers of compounds after scoring and ranking that were passed along to the subsequent stages were clustered, and representatives were purchased for in vitro testing.

SBVS, energy calculation, and clustering.

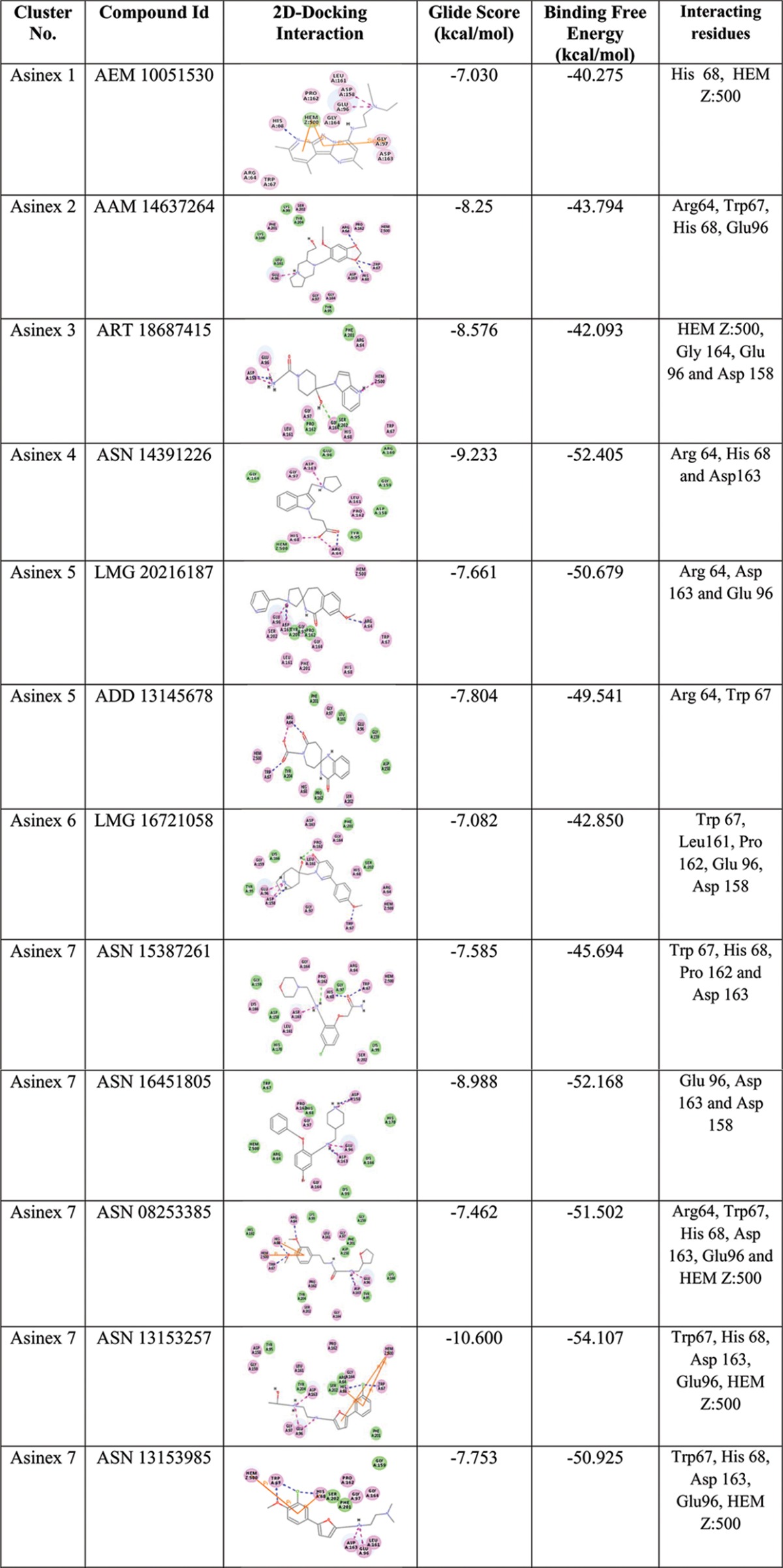

Thousands of hits with good ADMET values from Discovery Studio v2.5 and nonpromiscuous binders found were examined for interaction affinity toward LdAPx. The virtual screening workflow module of Schrödinger 9.6 was used for screening of filtered hits, since this module works on two programs, there is elimination of compounds through filters (Lipinski's rule of five, QikProp, and toxicophores), and filtered compounds have to pass three consecutive docking stages based on precision and accuracy: i.e., at each stage, as the docking accuracy increases, the size of the data set becomes smaller. The top-ranked solutions from high-throughput virtual screening (HTVS) were rescored using Glide SP (standard precision), and the output was subjected to Glide XP (extra precision). The Glide score was the selected criterion for selection of focused hits of LdAPx. In the different earlier studies, the Glide score had been used as a reliable function for sorting of a compound data set against drug target protein. Glide scoring has been found effective for ranking inhibitors (19). Hence, we ranked the hits according to the Glide XP score toward LdAPx. Thousands of compounds were docked through the three stages HTVS, SP, and XP to sort the data at each stage of docking, and the compounds had XP Glide scores ranging from −1.2 to −10.60 kcal/mol. The focused hits for LdAPx were selected according to the docking control used in the study. The Glide XP score of 4-triazol-5-amino (taken as the docking control) was found to be −6.7 kcal/mol. Thus, the focused library (2,458 Gold, 7,640 Platinum, and 3,697 Elite compounds in the Asinex subsets listed and 883 compounds in the ZINC Natural subset) with an XP Glide score of <−6.7 kcal/mol was selected (Fig. 2). To further validate the docking outcome, the binding free energy was calculated. The compounds were found to have binding free energy ranges from −40.275 to −55.039 kcal/mol, as shown in Table 1, which presents the thermodynamic stabilities of all compounds with LdAPx, and have the lowest possible energy conformations within the binding pocket. These high-XP-score-focused compounds were employed for clustering to select a limited number of promising and diverse molecules to be tested by in vitro assay. Twelve Asinex and 7 ZINC Natural clusters were obtained using the Tanimoto coefficient by Canvas (Schrödinger v9.6), and 26 representatives (19 Asinex and 7 ZINC Natural) among all clusters with the highest XP Glide scores among different chemotypes were chosen for further analysis.

TABLE 1.

Depiction of the 2D docking interactions of cluster representatives and LdAPx along with interacting binding residuesa

HEM Z:500, heme, an iron-coordinated porphyrin complex.

The major chemotypes present in different clusters, including piperidinyl-thiaaza, pyrrolo-piperazinyl, phenyl-tetrazolo-pyridin, pyrrolo-pyridinyl, pyridinyl pyrimidine, furanyl-piperidine, quinazolinol, quinolinone, morphaline, benzoimidazol, phenoxychromen, phenyl-furan, piperazinyl-benzoate, etc., are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material, and their interactions with LdAPx binding residues along with docking scores are shown in Table 1. Thus, the identified chemotypes may have LdPAx inhibition ability and therefore were procured for in vitro analysis.

In vitro sensitivity and cytotoxicity assay.

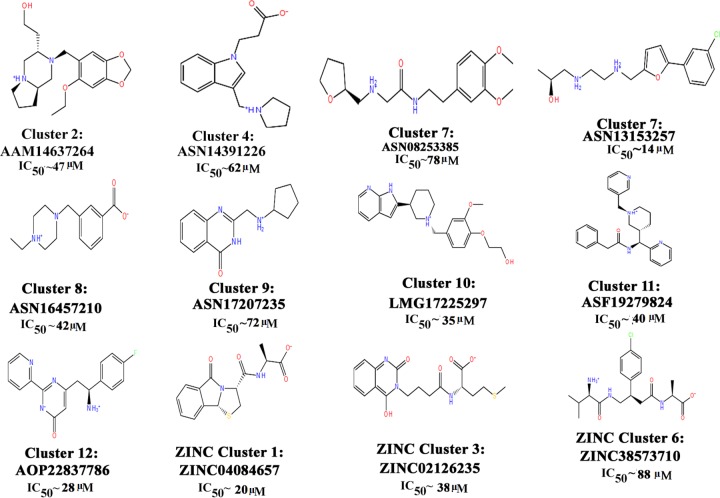

A total of 26 representatives (19 Asinex and 7 ZINC Natural) from all clusters were purchased for evaluation of their antileishmanial activity on L. donovani promastigotes (MHOM/IN/83/AG83) by MTT assay. On incubation of compounds (5 to 320 μM) with 2 × 106 L. donovani promastigote (MHOM/IN/83/Ag83) cells, the percentage of growth inhibition was evaluated in comparison with a control group, which depicted 12 compounds having significant activity in terms of 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values from 14 to 88 μM at 24 h, which were further analyzed to check their cytotoxicity, as shown in Fig. 3. Six of 12 compounds were found to be toxic for the host cell (BALB/c peritoneal macrophages) and hence were rejected for further assessment, and the remaining six compounds (i.e., (ASN13153257, AOP22837786, ZINC02126235, ASN14391226, ASN08253385, and ASN16457210) resulted in selectivity indices of 80 to 320 μM and were safer at higher concentrations (Table 2). These findings were also supported by our computationally predicted results (Table 3).

FIG 3.

Inhibitory potencies of 12 cluster representative compounds depicting scaffolds yielding significant activity (IC50) on Leishmania donovani promastigote culture.

TABLE 2.

In vitro test of the growth-inhibitory effects of predicted inhibitors on L. donovani promastigotes and amastigotesa

| Compound | IC50 value (μM) |

|

|---|---|---|

| In vitro | Ex vivo | |

| ASN13153257 | 14 | 26 |

| AOP22837786 | 28 | 45 |

| ZINC02126235 | 38 | 60 |

| ASN14391226 | 62 | 85 |

| ASN08253385 | 78 | 90 |

| ASN16457210 | 42 | 56 |

| Miltefosine (positive control) | 1.0 | 1.5 |

Shown are the results of in vitro testing of the growth-inhibitory effects of the predicted inhibitors on L. donovani promastigotes (MTT assay) and amastigotes (Giemsa staining) as determined with miltefosine as a positive control.

TABLE 3.

Toxicity of predicted structures using Discovery Studio v2.5 and cytotoxicity assay

| Compound | TOPKAT result for: |

Nontoxic concn of inhibitor (μM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ames prediction | Ames applicability | Ames probability | Ames enrichment | Ames score | ||

| ASN13153257 | Nonmutagen | All properties and OPSa components within expected ranges | 0.506558 | 0.907207 | −7.38012 | 80 |

| AOP22837786 | Nonmutagen | OPS PC72 out of range (value, −4.3804; training min, −4.3429; max, 5.3512; SD, 1.009; explained variance, 0.0038) | 0.648518 | 1.16145 | −3.63435 | 240 |

| ZINC02126235 | Nonmutagen | All properties and OPS components within expected ranges | 0.181972 | 0.325897 | −14.6001 | 160 |

| ASN14391226 | Nonmutagen | All properties and OPS components within expected ranges | 0.576183 | 1.0319 | −5.69739 | 240 |

| ASN08253385 | Nonmutagen | OPS PC88 out of range (value, 4.4151; training min, −4.1593; max, 4.1743; SD, 0.9186; explained variance, 0.0031) | 0.0267737 | 0.0479496 | −21.8817 | 320 |

| ASN16457210 | Nonmutagen | All properties and OPS components within expected ranges | 0.421099 | 0.754156 | −9.24423 | 320 |

OPS, optimal predictive space; min, minimum; max, maximum.

Sensitivity test for intracellular amastigotes.

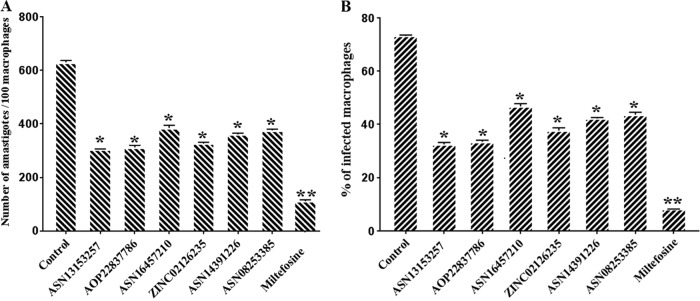

In order to test the activity of these six compounds (effective on promastigotes and nontoxic) on intracellular amastigotes, BALB/c peritoneal macrophages were infected with L. donovani and treated with different concentrations of inhibitors (20 to 100 μM). The numbers of amastigotes were counted microscopically on 100 macrophages per sample, and the results were expressed as a percentage of reduction of the infection rate in comparison to that of the control (Fig. 4A and B). Interestingly all six of these compounds were found to inhibit amastigote growth (Table 2) and reduced the parasite burden in infected macrophages by 30 to 51% (P < 0.05), whereas the positive control (2 μM miltefosine) reduced the parasite burden in infected macrophages by >80% (P < 0.001), compared with untreated controls. That these compounds were effective on amastigotes and were nontoxic to the host indicates the selectivity of these inhibitors against amastigotes as compared to mammalian cells, as evaluated by qualitative microscopic examination.

FIG 4.

Effects of inhibitors on macrophages infected with L. donovani by macrophage infection assay (ex vivo). The bar diagrams show the number of parasites per 100 peritoneal macrophages. (A) Peritoneal macrophages were infected with promastigotes at a ratio of 10:1 parasites to macrophages and treated with inhibitors or miltefosine (positive control). The number of infected macrophages was determined. (B) The percentage of intracellular amastigotes per 100 macrophages was determined microscopically after incubation with inhibitors or the positive control miltefosine (2 μM) for 24 h. There were three replicates in each experiment, and the data are the mean ± SD at each time point.

Enzymatic activity of rLdAPx.

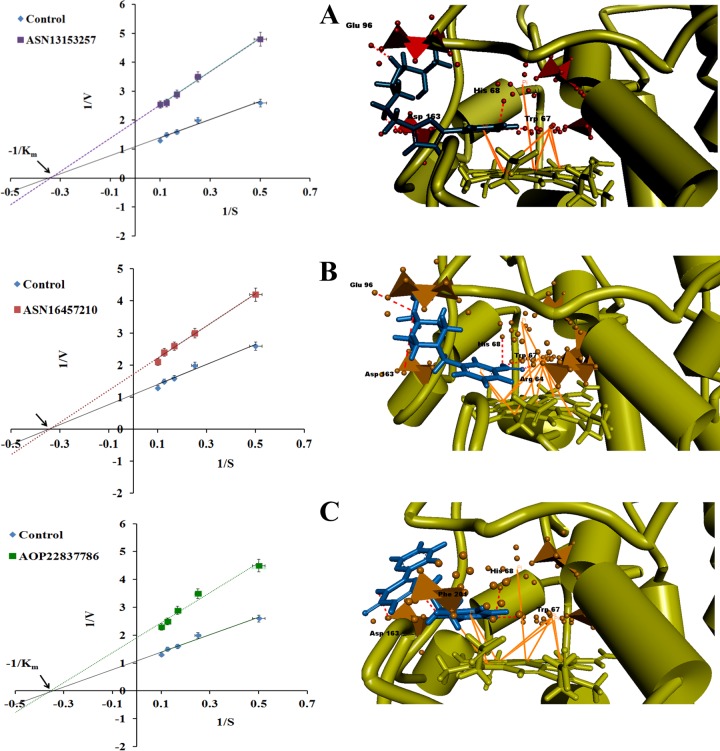

To determine the inhibitory effect of the identified six inhibitors (found effective on amastigotes and nontoxic), the compounds were incubated with a reaction mixture containing 10 μM purified recombinant LdAPx protein (rLdAPx). On addition of H2O2 (10 μM), three compounds (ASN13153257, ASN16457210, and AOP22837786) showed significant inhibition at 290 nm for ascorbate oxidation. The inhibition kinetics of these three inhibitors was studied by measuring the initial rate of reaction at a fixed inhibitor concentration and varying the concentration of substrate (H2O2) from 0 to 10 μM. The mode of enzyme inhibition was determined by fitting experimental values to a Lineweaver-Burk plot. The Vmax and Km values of rLdAPx in the absence of inhibitors were found to be 0.92 and 2.87 μM, respectively. All three identified inhibitors illustrated enzyme inhibition in a noncompetitive manner, as evaluated by Km and Vmax values, as shown in Fig. 5. The Ki values of the identified inhibitors were determined by fitting the data to equation 1 and are reported in Table 4:

| (1) |

FIG 5.

Inhibition mechanism and binding mode of potent inhibitors. Initial rates were measured as a function of the concentration of H2O2 at a fixed concentration of inhibitors. The entire top three hits act in a noncompetitive manner, as shown in the Lineweaver-Burk plot. Panels A to C show the predicted binding modes of (A) ASN13153257 (I1), (B) ASN16457210 (I2), and (C) AOP22837786 (I3) bound to LdAPx. Binding poses were visualized by Discovery Studio v2.5. The bound inhibitors are shown as blue sticks, and residues close to the inhibitors are represented as orange polyhedrons. The hydrogen bonds are shown by red dashed lines, and π-π interactions are shown as bold orange lines.

TABLE 4.

Inhibition patterns of identified LdAPx inhibitors with their Km, Vmax, and Ki values

| Inhibitor | Substrate | Type of inhibition | Km (μM) | Vmax (μM·min−1) | Ki (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASN13153257 | H2O2 | Noncompetitive | 2.931 | 0.510 | 6.21 |

| ASN16457210 | H2O2 | Noncompetitive | 2.924 | 0.583 | 8.5 |

| AOP22837786 | H2O2 | Noncompetitive | 2.80 | 0.522 | 6.5 |

Here, Vmax+I and Vmax−I represent the Vmax in the presence and absence of inhibitor, respectively, where I is the concentration of inhibitor (5 μM) and Ki is the inhibitory constant. The Kis for ASN13153257 (I1), ASN16457210 (I2), and AOP22837786 (I3) at a fixed concentration of 5 μM were found to be 6.21, 8.5, and 6.5 μM, respectively, confirming the actual inhibition of LdAPx by computationally identified inhibitors.

Binding mode of top hits.

In order to gain insight into the binding mechanism (3D view) of experimentally proven inhibitors (I1, I2, and I3), their binding modes in the active site of LdAPx were investigated. All three inhibitors are lying almost parallel with the plane of the heme at the distal end of enzyme.

Interestingly, aminotriazole (docking control) also binds at the δ edge of heme (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The predicted binding modes of I1, I2, and I3 are shown in Fig. 5A, B, and C, respectively. The docking results depicted that all three hits adopt very similar orientations within the LdAPx active site but are not directly involved in interaction with heme Fe and may not completely block the relay of the electron through H2O2 binding. However, binding of the top hits may bring out conformational changes in the active site that slow down the enzyme activity, which supports our experimental data showing the noncompetitive mode of inhibition. The binding pocket is composed of hydrophilic as well as hydrophobic areas, and all three inhibitors fit well into the hydrophobic pocket, making favorable hydrophobic interactions with residues Trp 67 and His 68. In addition, there are likely edge-to-face π-π stacking interactions between the heme and the aromatic ring of these three compounds, which could enhance the potency of the compound. Very minute differences in hydrophilic interaction may be due to involvement of different chemotypes or fingerprints, such as pyridinyl pyrimidine, phenyl-furan, and piperazinyl-benzoate; however, all three showed similar overall patterns of interaction.

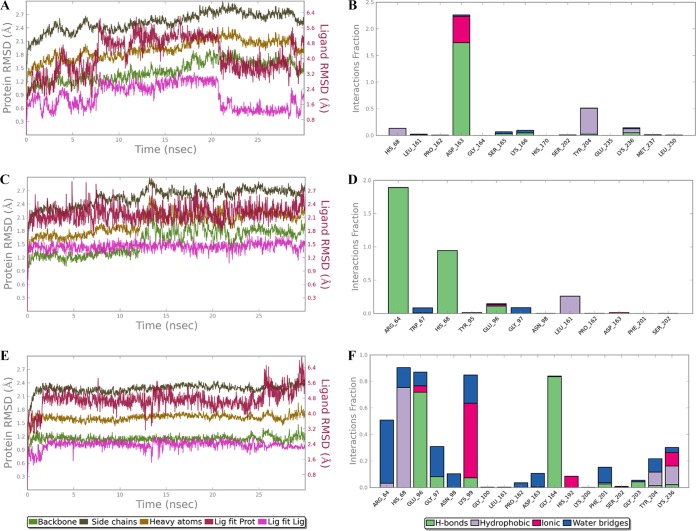

MD simulation of protein-ligand complex.

In order to validate the results of docking simulation and to explore the interaction pattern of the inhibitors (I1, I2, and I3), molecular dynamic (MD) simulation was performed. The RMSD plot and protein-ligand contact throughout the simulations were analyzed for 30 ns, as shown in Fig. 6. The MD analysis showed that the RMSD trajectories for LdAPx were within 1 to 3 Å, which is the permissible limit for small, globular proteins. In the overall simulation, the protein is stable enough, while the deviation in ligand (termed “Lig fit Lig”) was observed at a few points that may be due to formation of new contacts with other residues of binding pocket. The RMSD of the “Lig fit Prot” parameter (where “Prot” represents “protein”) is less than the RMSD of protein, indicating that all three inhibitors were allocated in the binding pocket within the overall simulation period, indicating the stability of their interaction. Protein-ligand contacts were categorized into four types: hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic, ionic, and water bridges. The inhibitors had stable interaction with the active site residues Glu 96, His 68, Trp 67, Arg 64, Asp 163, and Phe 201, conserved throughout the simulation (Fig. 6), and other interactions within the binding pocket were also observed.

FIG 6.

RMSDs of the protein-ligand complex and protein-ligand interaction throughout the simulation period are shown for ASN13153256 (A and B), ASN16457210 (C and D), and AOP22837786 (E and F). The RMSDs of backbone, side chain, heavy atoms, and the “Lig fit Lig” parameter are represented in the different colors defined in the keys below the graphs. The protein-ligand interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic, ionic, and water bridges) are represented by the different colors shown in the keys below the graphs.

Comparative study with Prx.

APx is well known to be absent in humans (9, 20), but human peroxiredoxin-1 (Prx) (NP_859048) was identified as the closest human peroxidase from BLASTp, sharing 26% query coverage and 33% sequence identity with LdAPx. Primary sequence alignment showed much less sequence conservation between human Prx and LdAPx. No amino acids from the catalytic domain of LdAPx were found conserved with human Prx (shown in Fig. 1A), which implied that both peroxidases may not be structurally conserved. From the phylogenetic analysis, the human peroxidase was also found to be distantly related to Leishmania APx, as shown in Fig. 1B.

On structural comparison between human and leishmania peroxidases, we found entire dissimilarities in both structures, with RMSDs of 21 Å, as shown in Fig. S2A in the supplemental material. The domain of LdAPx is composed of an α-orthogonal bundle, while human Prx bears a 3-layer α/β/α domain, which are quite dissimilar. Interestingly, the binding pockets of both proteins are located at different sites, as shown in Fig. S2B. The binding pocket of LdAPx is located near the distal end of the domain, at the δ-heme edge, whereas, the binding pocket of human Prx (PDB no. 4XCS) is located at a dimeric junction of Prx, having the following dimensions: x, −38.155; y, 1.441; and z, −12.288. Kim et al. (21) also elucidated the same binding pocket as a “druggable” binding site, which supports our data.

Finally, the binding free energies of the three inhibitors of LdAPx proposed in this study (I1, I2, and I3) with LdAPx are −54.107, −48.174, and −55.039 kcal/mol, while the free energies of the same inhibitors for human Prx are −9.07, −11.03, and −6.73 kcal/mol, respectively, which confirms the strong affinity of inhibitors for the LdAPx and comparatively very weak affinity for human Prx (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Hence, these three compounds may be the specific inhibitors of LdAPx. The higher binding energies or weak interactions of these three compounds with human Prx may be due to large structural, domain and active site differences between the two proteins.

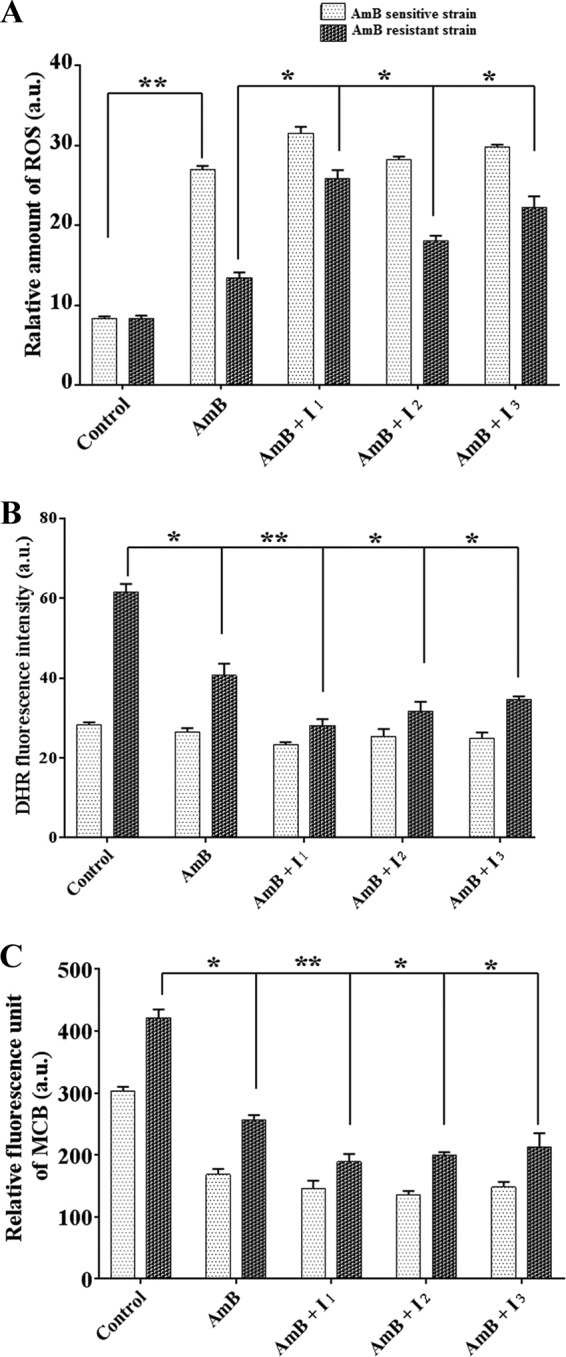

Reversion of the AmB-resistant phenotype by LdAPx inhibitors.

The enzyme-specific potent inhibitors I1 (14 μM), I2 (42 μM), and I3 (28 μM) were preincubated with sensitive and resistant parasites, which confirmed partial reversion of AmB-resistant phenotypes. The 50% lethal dose (LD50) of inhibitors for the resistant strain (in vitro) decreased up to ∼2.0-fold (Table 5). However, the LD50 of the sensitive strain was not significantly altered by preincubation of inhibitors. These data show the effectiveness of these inhibitors on AmB-resistant isolates.

TABLE 5.

Reversion of resistant phenotype by inhibition with LdAPx inhibitors as shown by an in vitro AmB sensitivity assay

| Treatment group | AmB LD50 (μg/ml) | Fold change |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitive + AmB | 0.12 | |

| Resistant + AmB | 0.83 | |

| Resistant + I1 + AmB | 0.42 | ∼2.0 |

| Resistant + I2 + AmB | 0.45 | ∼1.85 |

| Resistant + I3 + AmB | 0.63 | ∼1.25 |

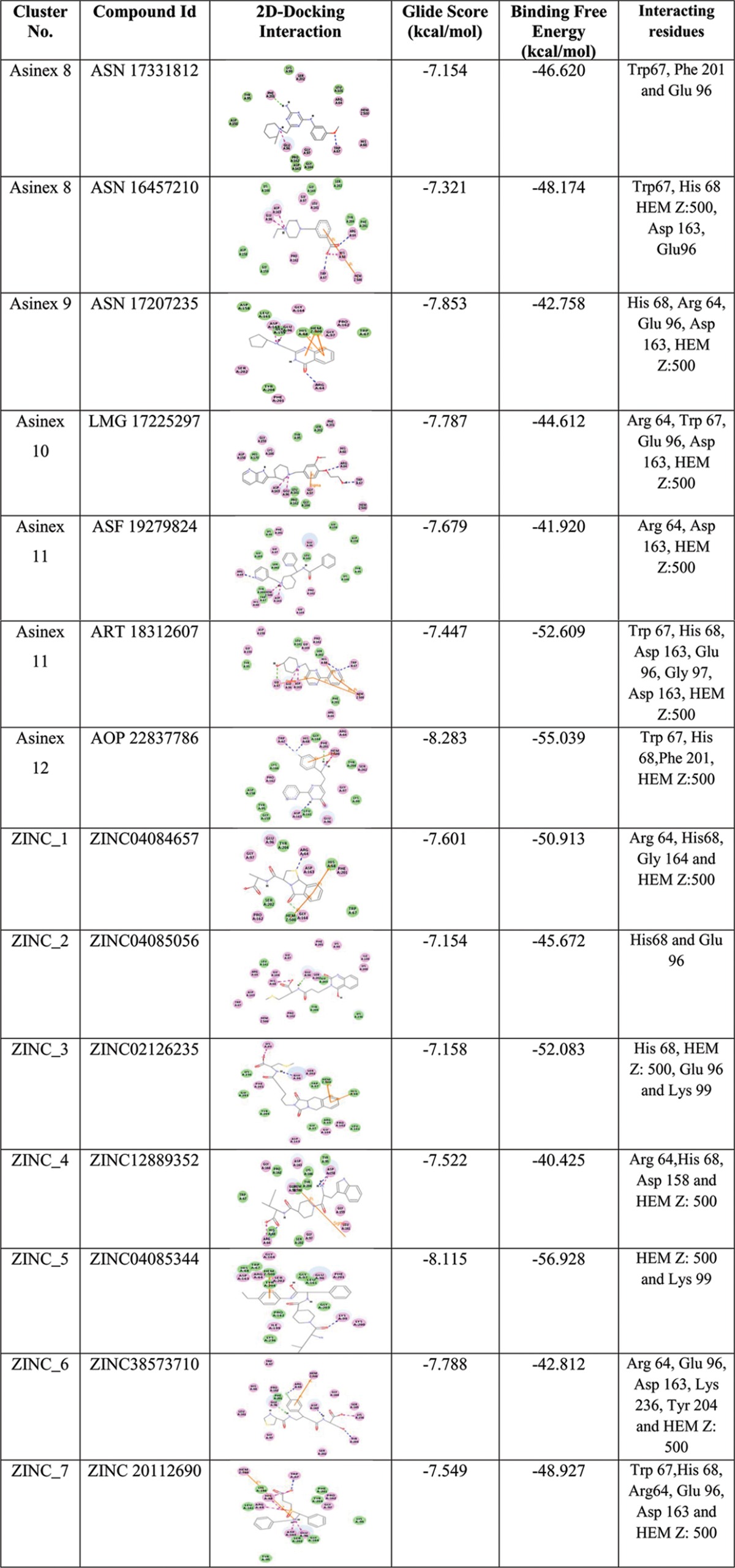

Intracellular ROS measurement.

AmB becomes auto-oxidized inside the cell and produces ROS. It had been reported earlier that ROS was minimized by the overexpression of LdAPx for the survival of the AmB-resistant strain (9). Therefore, we measured the consumption of ROS in AmB-sensitive and -resistant isolates in the presence of AmB (0.125 μg/ml) and inhibitors I1 (14 μM), I2 (42 μM), and I3 (28 μM). The level of ROS significantly increased in the AmB-treated sensitive strain rather than the resistant strain compared to the control (P < 0.001). However, when the same strain was treated with inhibitors, the level of ROS increased by ∼2-fold in the AmB-resistant strain (P < 0.05) compared to its control set, while no significant changes were observed in the sensitive strain, indicating LdAPx might have a crucial role in the detoxification of endogenous ROS shown in Fig. 7A.

FIG 7.

Comparative study of ROS, mitochondrial peroxidase activity, and GSH content after incubation with AmB and enzyme-specific inhibitors in both the AmB-sensitive and -resistant strains. (A) Fluorometric assay (using the H2DCFDA fluorogenic probe) to assess the content of ROS in AmB-sensitive and -resistant isolates after incubation of AmB and inhibitors. (B) Assessment of peroxidase activities of AmB- and inhibitor-preincubated AmB-sensitive and -resistant isolates using the fluorogenic peroxidase substrate dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR). (C) The effect of inhibitors on cellular GSH content in AmB-sensitive and -resistant isolates was observed. MCB, monochlorobimane dye. Asterisks indicate significant difference: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001.

Mitochondrial peroxidase activity.

The mitochondrial peroxidase activities of AmB-sensitive and -resistant strains were measured in the presence of inhibitors I1 (14 μM), I2 (42 μM), and I3 (28 μM) after exogenous addition of AmB (0.125 μg/ml) using the fluorogenic dye dihydrorhodamine 123 (peroxidase substrate). After 24 h, significant decrease (∼2-fold) in the rhodamine 123 fluorescence was observed in the resistant strain (P < 0.05), but no significant changes were observed in the sensitive strain, which may be due to altered mitochondrial peroxidase activity in resistant parasites on treatment with inhibitors, as shown in Fig. 7B.

Measurement of intracellular GSH content.

GSH content plays a vital role in compensating for cell damage on exposure to oxidants. The AmB-sensitive and -resistant parasites on treatment with AmB (0.125 μg/ml) and inhibitors I1 (14 μM), I2 (42 μM), and I3 (28 μM) showed up to ∼2.1- and ∼2.3-fold lower GSH contents for their sensitive and resistant counterparts, respectively (P < 0.05), compared with the control sets shown in Fig. 7C.

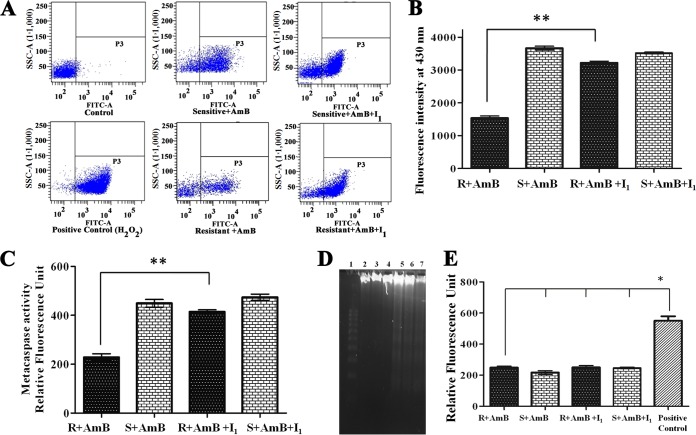

Analysis of AmB-induced apoptosis-like phenomena after inhibitor (I1) treatment.

AmB-treated sensitive and resistant promastigotes (107) were preincubated with LdAPx inhibitor ASN13153257 (I1) and analyzed for peroxidized product. We observed that resistant parasites produced 2.2-fold less lipid-peroxidized product (P < 0.001) compared to sensitive parasites following exposure to amphotericin B, while on treatment with inhibitor (I1), the resistant parasites accumulated 1.8-fold higher lipid-peroxidized product (P < 0.001) compared to the untreated resistant parasites (Fig. 8B). Therefore, overexpression in AmB-resistant cells saved the parasites from lipid peroxidation-derived damage caused by a lethal dose of amphotericin B.

FIG 8.

Analysis of AmB-induced apoptosis-like phenomena after inhibitor (I1) treatment. (A) The figure depicts the cell death assay by flow cytometry in response to inhibitor (I1) and the positive control (100 μM H2O2), where the differential changes in the apoptotic population are represented by the annexin V-positive but PI-negative cells in response to LdAPx inhibitor and the live population are represented by annexin V-FITC and PI-negative cells. (B) The rate of lipid peroxidation in AmB-sensitive and -resistant strains was measured by spectrofluorometer and is expressed as fluorescence units at 430 nm. (C) Metacaspase activities in the AmB-sensitive and -resistant parasites after exposure to inhibitor (I1). (D) DNA fragmentation analysis by agarose gel electrophoresis. The DNA profiles by lane are as follows: lane 1, markers; lane 2, DNA of the resistant parasite; lane 3, DNA of the sensitive parasite; lane 4, DNA from the resistant AmB-treated strain; lane 5, DNA from the sensitive AmB-treated parasite; lane 6, DNA from the resistant parasite treated with AmB plus LdAPx inhibitor (I1); lane 7, DNA from the sensitive parasite treated with AmB plus LdAPx inhibitor (I1). (E) Measurement of released lactate dehydrogenase to determine the membrane integrity of AmB-sensitive and -resistant L. donovani parasites after treatment with 14 μM LdAPx inhibitor (I1) for 4 h. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Asterisks indicate significant difference: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001.

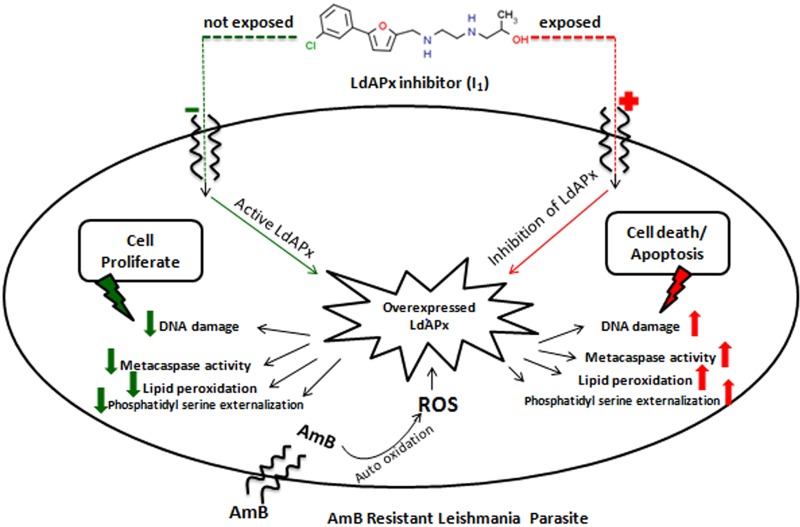

A 2014 report by Kumar et al. (9) showed that AmB induced an apoptosis-like phenomenon in sensitive parasites, but resistant parasites failed to induce apoptosis, as has been demonstrated by phosphatidylserine (PS) externalization and DNA fragmentation. In this study, we have investigated whether the APx-specific inhibitor I1 could induce an apoptosis-like phenomenon in resistant parasites after AmB treatment. PS is normally confined to the inner leaflet of the cell membrane and is externalized when the cell is committed to apoptosis (22). PS externalization was detected by annexin V labeling. Flow cytometric analysis revealed that after inhibition with ASN13153257, the number of annexin V-positive cells increased (48.4% apoptotic cells) 2.8-fold in resistant parasites compared with untreated resistant parasites (17.2%), while in sensitive parasites, AmB alone could induce the externalization of phosphatidylserine given (52.3% of apoptotic cells), and no significant changes were observed after addition of APx inhibitor in sensitive parasites (56.7%), whereas the positive control (100 μM H2O2) showed 92% apoptotic cells (Fig. 8A). These data clearly indicate that inhibition of LdAPx induces an apoptosis-like phenomenon in AmB-resistant parasites. Metacaspase-like protease activity was found in apoptotic cells of inhibitor-treated resistant parasites and AmB-treated sensitive parasites. Inhibitor-treated resistant parasites showed 1.74-fold higher metacaspase-like protease activity (P < 0.001) compared to resistant parasites (Fig. 8C). Agarose gel (1.5%) analysis showed an oligosomal ladder of DNA after inhibition with I1 in resistant parasites. Similarly, AmB could also induce oligosomal DNA degradation in susceptible parasites, but there were no significant changes in inhibitor (I1)-treated susceptible parasites. Overall, this indicates that inhibition of LdAPx induces DNA degradation in resistant parasites after AmB treatment. Thus, LdAPx may be involved in controlling AmB-induced DNA degradation and therefore contribute to AmB resistance (Fig. 8D). Furthermore, to determine the membrane integrity of untreated and LdAPx inhibitor-treated (14 μM I1) AmB-sensitive and -resistant promastigotes after 4 h of inhibitor incubation, the release of lactate dehydrogenase from the cells with damaged membrane was measured with a CytoTox assay kit (Promega). The cells were lysed with 1% Triton X-100: where almost 100% cell lysis was expected, the result was taken as a positive control. We observed very high lactate dehydrogenase activity in the positive control, which might be due to release of enzyme as a result of membrane rupture in the presence of 1% Triton X-100. Although we observed no significant change in membrane integrity between untreated and treated groups, in fact the enzyme activities were very low in both treated and untreated sensitive as well as resistant parasites compared to those of the positive control (P < 0.05) (Fig. 8E). The overall AmB-induced apoptosis-like phenomenon after inhibitor treatment is depicted in Fig. 9. The general screening strategy used in this study to identify hits is shown in Fig. 10.

FIG 9.

Overall AmB-induced apoptosis-like phenomenon or mode of parasite death in AmB-sensitive and -resistant parasites after inhibitor (I1) treatment.

FIG 10.

Schematic representation of the screening strategies adopted in this study.

DISCUSSION

The current pharmacopoeia for leishmaniasis comprises drugs that have their own limitations in terms of toxicity, adverse effects, and high cost or which may have long courses of parenteral administration. Therefore, there is a need to discover and design novel compounds for Leishmania chemotherapy.

The first step in drug discovery is to identify a suitable drug target that should be necessary for the survival of the pathogen and should be either absent from the host or substantially different from the host homolog (23). The intracellular pathogen Leishmania exhibits a strong antioxidant defense mechanism by using hemoproteins such as APx of the glutathione-ascorbate cycle for its survival and replication against the oxidants (H2O2) released by the macrophage under oxidative burst conditions (10). The absence of this redox pathway in the human host may be exploited as an attractive and potential therapeutic drug target to approach for structure-based drug design (SBDD) (9).

On sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis, we observed marked similarities among LdAPx and other members of the trypanosome family, although unrelated to human peroxidase; moreover, all of these kinetoplastid homologs have conserved catalytic residues (i.e., His 68, Trp 67, and Arg 64 on the distal heme edge), which gives clues for similar patterns of inhibitor binding (Fig. 1A and B). The 3D structure of the protein and a compound library are essentially required for SBDD, so the 3D model of LdAPx was generated by using various tools and software, taking 3RIV as the template. The model built by Prime (Schrödinger v9.6) was considered to be reliable based on the lowest DOPE score (−34,002.30) (Fig. S1A). The central pocket of the model comprises heme cofactor, which is surrounded by residues such as Pro 60, Ser 61, Arg 64, Trp 67, His 68, Pro 162, Asp 163, Gly 164, Phe 175, Leu 188, Ile 189, Ala 191, His 192, Lys 200, Ser 202, Phe 215, Leu 250, and Ser 252, as predicted by conserved domain server. The heme binds to LdAPx with a CDOCKER interaction energy of 102.655 kcal/mol, favoring its role as a critical cofactor for regulation of redox reaction. We also validated the model by checking the stereochemical properties by means of a Ramachandran plot, showing all residues in allowed region, confirming the compatibility of residues (Fig. S1B). The overall quality of the model was found to be −9.27, which is very close to the value of the experimentally solved structure (template 3RIV), −8.69, suggesting the authenticity of the generated model (Fig. S1C). We also observed very minute deviation in the structural superimposition of the model and template. All of the above parameters were within the range, confirming the model to be valid to be used for screening. On structural insight into LdAPx, we observed that it is composed of mainly an alpha-orthogonal bundle with two peroxidase domains responsible for detoxifying the toxic effect of H2O2, as supported by Fig. 1C. The LdAPx structure begins with an N-terminal transmembrane loop of sequence length 34 amino acids that continues with α helices: i.e., α1 (Asp 40 to Leu 56), α2 (Ser 61 to Ala 70, where active site residues such as Arg 64, Trp 67, and His 68 are located), α3, α4, α5, α6 (Pro 104 to Leu 111), and α7 (Tyr 120 to Tyr 129). Furthermore, the structure extends to β1 (Phe 142 to Trp 144) along with α8, forming the distal peroxidase domain. On the other hand, the proximal end is situated near the C terminus and is composed of α9 (Gln 168 to Arg 177), α10 (Asp 182 to Thr 193, where His 192 binds with heme Fe), β2, α11, β3 (hairpin structure), α12, β4, β5, and β6 (forming two hairpins), which then extends to α13, α14, and α15. The distal δ-heme edge of LdAPx is responsible for binding of inhibitors.

Novel drugs developed through computational approaches take a much shorter time and cost less to reach the market. Therefore, we initiated a journey to search for inhibitors using SBDD, where the LdAPx model was screened with approximately 4.5 million Asinex and ZINC Natural subset compounds in the centroid of the active site residues Arg 64, Trp 67, and His 68, located at the δ-heme edge (Fig. 1D) (18) and are involved in the redox mechanism for peroxidase proposed many years ago by Poulos-Kraut (24). To obtain a well-curated library, compounds were filtered by ADMET and the PAIN assay interference filter. Compounds were filtered out from the list of drug-like molecules if they did not show the following properties, such as good or moderate human intestinal absorption, low blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration, no inhibition of CYP2D6, and no hepatotoxicity. Furthermore, the promiscuous compounds or pan-assay interference compounds were removed as they interfere in many biochemical high-throughput screens. The ADMET and promiscuous filtration resulted in 53,855 curated compounds, which were subjected to HTVS. Previous studies by Kumar et al. showed that the compound 1H-1,2 4-triazol-5-amine inhibits LdAPx in L. donovani (9), and we found the Glide score of this molecule to be −6.7 kcal/mol. Hence, a total of 2,458 Gold, 7,640 Platinum, and 3,697 Elite compounds in the Asinex subsets and 883 ZINC Natural compounds with a cutoff Glide score of <−6.7 kcal/mol were visually inspected for pose and binding free energy at the active site center (Fig. 2). Similar validation protocols have been implemented by Muralidharan et al. (19) and Pavadai et al. (25) in virtual screening of libraries, where they got few potential hits through in vitro validation. Furthermore, we clustered these screened compounds with the Tanimoto coefficient, which classifies compounds into groups of similar compounds depending on the calculation of intermolecular distances in chemical spaces. Out of 12 Asinex and 7 ZINC Natural clusters, 26 promising and diverse cluster representatives were selected for in vitro assay. To further confirm the docking outcome, the binding free energies of these selected representatives were calculated that elucidated their favorable binding with LdAPx. Use of computational software such as Discovery Studio, Schrödinger, FlexX, etc., is a rational approach to drug discovery to find inhibitors for leishmaniasis or other diseases (16, 17).

For the in vitro test initially, we procured and tested these 26 compounds on L. donovani promastigotes (MHOM/IN/83/AG83) by MTT assay. Out of these 26 compounds, 12 compounds with an IC50 of <100 μM and containing major chemotypes, such as piperidinyl-thiaaza, pyrrolo-piperazinyl, phenyl-tetrazolo-pyridin, pyrrolo-pyridinyl, pyridinyl pyrimidine, furanyl-piperidine, quinazolinol, quinolinone, morphaline, benzoimidazol, phenoxychromen, phenyl-furan, piperazinyl-benzoate, etc. (Fig. 3), were further examined for cell cytotoxicity on the BALB/c peritoneal macrophages. Cytotoxicity results showed six compounds to be toxic on BALB/c peritoneal macrophages, which may contain structural alerts for toxicity, and hence they were rejected from the study. The remaining six representatives (i.e. ASN13153257, AOP22837786, ZINC02126235, ASN14391226, ASN08253385, and ASN16457210) had wider efficacy up to 320 μM, as well as no toxic effects at higher concentrations, which is also supported by our in silico predicted results (Table 3). Interestingly, these screened-out six representatives were sensitive on intracellular amastigotes, with an IC50 of 26 to 90 μM, and they reduced the parasite burden in infected macrophages by 30 to 51%, whereas the positive control (2 μM miltefosine) reduced the parasite burden in infected macrophages by >80% compared with untreated controls (Fig. 4A). Thus, the outcome signifies the selectivity of these inhibitors toward amastigotes as to host cells. Enzymatic assay of purified rLdAPx identified as the top three hits ASN13153257 (I1), ASN16457210 (I2), and AOP22837786 (I3), with Kis of 6.21, 8.5, and 6.5 μM, respectively. The Kms of these top hits were approximately same, while the Vmaxs decreased, proposing a noncompetitive mode of enzyme inhibition (Fig. 5), confirming these three hits to be potent, nontoxic, and specific inhibitors of LdAPx. The 3D binding mode of the identified inhibitors was elucidated, which showed through binding with active site residues such as Arg 64, Trp 67, His 68, Glu 96, Asp 163, and Phe 201 that these protein-ligand complexes were also conserved throughout the MD simulation for 30 ns (Fig. 6), which shows the stability of the interaction near the active site.

All three of the experimentally proven inhibitors I1, I2, and I3 interact near the plane of heme at the distal end of the enzyme. The binding studies by Dolai et al. show that SCN (a potent peroxidase inhibitor) interacts at the heme edge as an inhibitor and competes with substrate, which also supports our result (26). On the other hand, I1, I2, and I3 bind with human Prx at the monomer junction. Kim et al. (21) also elucidated a similar binding site for the virtually screened inhibitors, supporting our data. Interestingly, the binding affinity (binding free energy of complex) of I1, I2, and I3 with LdAPx is very strong compared with human Prx, which might be due to huge variation among sequences, structures (21-Å RMSD), folding domains, and binding pockets (Fig. S2). Hence, these three compounds may be specific inhibitors of LdAPx without interacting with human Prx.

Furthermore, we also evaluated the effect of these LdAPx inhibitors on the AmB-resistant parasites to detect the effect of the glutathione-ascorbate pathway inhibitors on the phenotype of the AmB-resistant strain, and we observed partial reversion of AmB-resistant phenotypes in the presence of I1, I2, and I3; additionally, the LD50 of inhibitors decreased by ∼2.0-fold (in vitro) for the resistant strain. Our data support the results of Kumar et al. (9), who showed partial reversion of the phenotype of the AmB-resistant strain, depicting these inhibitors as being effective on AmB-resistant isolates. Previously it was reported that AmB generates ROS after auto-oxidation and may affect cells. ROS is an important signaling molecule that is microbicidal and essential to control Leishmania infection (27). Therefore, it is important to explore ROS scavenging pathways to target the ROS-reducing enzymes by newer drug alternatives. In this work, we observed significantly increased levels of ROS in the AmB-treated sensitive strain rather than the resistant strain compared to the control. However the level of ROS was increased in AmB-resistant isolates, while no significant changes were observed in the sensitive strain upon treatment with AmB and LdAPx inhibitors (I1, I2, and I3), indicating resistant parasites use this enzyme to conquer oxidative stress and also that these in silico-derived inhibitors are effective at accelerating the toxic effect of endogenous ROS (Fig. 7A). Similar findings have been shown in previous work by Kumar et al. (9).

Mitochondrial peroxidases have emerged as a major regulatory platform that acts as a fundamental regulator of cellular proliferation and apoptosis, whereby the peroxidase activity has a major role in removal of oxidants (28). In our study, we observed increased fluorescence intensity in resistant isolates compared to sensitive isolates, indicating LdAPx and other mitochondrial peroxidases play a crucial role in the ROS-scavenging mechanism (Fig. 7B). After incubation with AmB and I1, I2, and I3, a decrease in fluorescent intensity was observed in the resistant strain that may be due to an increase in ROS, which has a deleterious effect on resistant parasites, signifying these LdAPx-specific inhibitors inhibit the ROS-scavenging activity of LdAPx in resistant isolates. Recent reports also demonstrate that 2.5-fold-higher peroxidase activities were observed in the LmAPx-overexpressing parasites compared to the control (28).

GSH content plays a central role in parasite protection against host defense systems. We found higher GSH content in the resistant and sensitive counterparts after exposure to AmB (oxidant) and inhibitors (I1, I2, and I3), indicating the crucial role of GSH content in compensating for cell damage on exposure to oxidants and inhibitors (Fig. 7C). This study is incongruent with the study of Ghosh et al., who observed significant depletion of GSH upon treatment with oxidants (29).

The mode of parasite death has been investigated in the presence of the LdAPx inhibitor I1, which showed apoptosis-like cell death as described below. The other two inhibitors (I2 and I3) had a similar pattern of cell death (data not shown). As we have already mentioned, LdAPx inhibitors lead to increased levels of ROS, and lipid peroxidation has been considered a biomolecular marker of oxidative stress and cell death. In this study, we found a significant increase in lipid peroxide level for AmB-resistant Leishmania promastigotes after exposure to LdAPx inhibitor (I1). Hence, it can be concluded that ROS generation due to inhibition of LdAPx might be one of the causes of increasing lipid peroxidation that ultimately leads to reduced cell viability and growth of Leishmania parasites, while the overexpression of LdAPx in AmB-resistant cells saved the parasites from ROS and lipid peroxidation-derived damage (Fig. 8B). Similar observations were reported by Sardar et al., who showed an increase in lipid peroxide level in L. donovani after spinigerin treatment (30).

Activation of apoptosis as a clearance mechanism for oxidatively damaged cells or protective responses to ROS-induce oxidative stress is regulated by various signal circuitries. One of the well-known features of apoptosis-like death is externalization of phosphotidylserine (PS) in the outer leaflet of the membrane bilayer (31). The flow cytometric analysis in our study revealed increases in annexin V-positive cells on treatment with LdAPx inhibitor I1 in resistant parasites compared to untreated resistant parasites after exposure to AmB. This suggested that activation of apoptosis signal might be due to inhibition of overexpressed LdAPx, which may lead to an increase in ROS and ultimately cell death (Fig. 8A).

Purkait et al. showed that metacaspase-like protease activity was found in apoptotic parasites (32), and it is well established that metacaspase-like protease activity was found to be associated with apoptotic stimuli. Therefore, to observe the effect of an LdAPx inhibitor on cell death, we examined the metacaspase-like activity of LdAPx inhibitor pretreatment in sensitive and resistant parasites after exposure to AmB. Interestingly, we observed ∼1.74-fold-higher metacaspase-like protease activity in LdAPx inhibitor-treated resistant parasites compared to untreated ones (Fig. 8C), which leads to downstream events of metacaspase activation, such as DNA fragmentation, which suggests that the proteases are involved in AmB-induced programmed cell death of Leishmania cells.

DNA fragmentation agarose gel (1.5%) analysis showed an oligosomal ladder of DNA after inhibition with I1 in resistant parasites. Similarly, AmB could also induce oligosomal DNA degradation in susceptible parasites, but there were no significant changes in inhibitor (I1)-treated susceptible parasites Overall, this indicates that inhibition of LdAPx induced DNA degradation in resistant parasites after AmB treatment. Thus, LdAPx may be involved in controlling AmB-induced DNA degradation and may therefore contribute to AmB resistance (Fig. 8D).

We observed very high lactate dehydrogenase activity in the positive-control group (1% Triton X-100), which might be due to release of enzyme as a result of membrane rupture, while no significant change in membrane integrity between untreated and treated groups was observed. Also the enzyme activity was very low in all members of the experimental set other than the positive control (Fig. 8E). In general, the effect of the LdAPx inhibitor on cell death in AmB-sensitive and -resistant parasites is depicted graphically in Fig. 9.

In conclusion, the identified hits may represent good LdAPx inhibitors with nontoxic properties that could be utilized as scaffolds for further in vivo studies and may provide the impetus for the development of promising leads in the future, which may be used alone or in combination with conventional drugs as an alternate chemotherapy for VL.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Phylogeny and homology modeling.

The amino acid sequences of L. donovani APx (AFA46757.1) and its homologs from L. infantum (A419H5), L. major (Q4Q3K2), L. mexicana (E9B4H3), L. braziliensis (A4HAD2), and T. cruzi (Q4CRX7) were retrieved from the NCBI database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). APx is reported to be absent in humans (9) as a BLASTp run against LdPAx resulted in none of its homologs. However, although the peroxidase of humans, peroxiredoxin-1 (Prx [NP_859048]), shared only 26% query coverage and 33% identity with LdAPx, based on sequence alignment, it thus was considered in this study. Multiple sequence alignment (MSA) was performed by ClustalW (33) and visualized using the PostScript (ESPript) server (34). The aligned sequences were used for construction of the phylogenetic tree by the neighbor-joining (NJ) method, and phylogeny was tested with 1,000 bootstrap replication using the Poisson model method of Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis software (MEGA v5.2) (35). 3RIV was selected as the best template for homology modeling while searching the Protein Data Bank (PDB [http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/home/home.do]) (36). Different methods like distances and dihedral angle restraints (GENO3D), a knowledge-based approach (Swiss-Model), automated modeling by satisfaction of spatial restraints (Modeler and Discovery Studio), and advanced sampling and refinement algorithms with higher accuracy (Prime) were implemented to find the accurate model. Out of the resulting models, the model with the lowest discrete optimized protein energy (DOPE) score (37) was built by Prime (Schrödinger Suite v9.6 [using default parameters]). Prime is a powerful and complete tool for generating accurate receptors (38, 39). Heme cofactor was included in the model as it is a crucial cofactor for the relay of electrons during redox activity of LdAPx. The built model was validated to analyze the stereochemical properties by a Ramachandran plot using Procheck (40). The overall quality of the model was validated by checking the Z-score using the ProSA server (41). The RMSDs of the template and model were investigated by the Dali server (37). The key active residues were taken from published literature (12), and the grid was generated in the receptor grid generation panel by setting the center of the grid map around the catalytic site at a 20-Å workspace using Schrödinger v9.6 by selecting the hot spot residues in the x, y, and z dimensions for virtual screening and docking studies.

Compound library.

For virtual screening and docking studies, the diverse compound libraries were designed using a set of synthetic compounds from the Asinex Gold (205,883 compounds), Platinum (113,962 compounds), and Elite (70,144 compounds) library (42) and natural compounds from the ZINC Natural database (54,451 compounds) (43, 44). Duplicates and promiscuous compounds (pan-assay interference) were removed from the library by Canvas (Schrödinger v9.6) and the False Positive Remover server, respectively (45).

Furthermore, the compounds were prefiltered based on ADME and drug likeness (Lipinski's rule) properties by using the QikProp module (Schrödinger v9.6).The carcinogenic and mutagenic properties of compounds were predicted using the TOPKAT module of Discovery Studio v2.5 (46), and these curated compounds were prepared by LigPrep (Schrödinger v9.6), using OPLS 2005 (47).

VS, free energy calculation (MM-GBSA), and clustering.

For virtual screening (VS), the active site of LdAPx and the curated library was utilized by means of the VS workflow of Schrödinger v9.6, which works in three consecutive docking stages based on precision and accuracy: i.e., high-throughput virtual screening (HTVS), standard precision (SP), and extra precision (XP). At each stage, as the docking accuracy increases, the size of the data set becomes smaller (48). The docking and scoring were performed by using default docking parameters. The final scoring of compounds was done based on XP output (19). The interaction (Glide XP score) of known APx inhibitor 4-triazol-5-amino (12) was taken as a positive control in our docking studies. The compounds with Glide XP scores better than that of the control were selected for further study. To further validate the docking results and to determine the thermodynamic stability of screened compounds within the active site, the XP docked poses were submitted to Prime MM-GBSA (Schrödinger, LLC.) for calculation of binding free energies using the default setting (49). The binding free energy (ΔG bind) was calculated as follows:

| (2) |

where

| (3) |

The variables Ecomplex, Eprotein, and Eligand denote the minimized energy values of the protein-ligand complex, protein only, and inhibitor only, respectively. ΔGsolv represents the electrostatic solvation energy of the complex, and ΔGSA denotes the nonpolar contribution by the surface area (SA) to the solvation energy. The sorted compounds were clustered based on the Tanimoto coefficient between a set of linear fingerprint descriptors using Canvas (Schrödinger v9.6) (50, 51).

Sample preparation.

The compounds with the highest docking scores of different chemotypes were procured from the vendors Asinex Europe BV (European Logistics, Netherlands) and Inter Bioscreen, Ltd. (Russia). The stock solutions of procured compounds were made in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and further dilutions were made in distilled water to prepare the stock solution (5 mg/ml). In all experiments, the final concentration of DMSO was cautiously maintained at ≤0.1% (vol/vol), as it is nontoxic for promastigotes and amastigotes of L. donovani, as reported by Chakrabarti et al. (52). The stock preparations were stored at −20°C for further use.

Clinical isolates and parasite culture.

Clinical samples (splenic aspirates) from AmB-responsive and -nonresponsive patients with VL were obtained from the indoor ward facility of Rajendra Memorial Research Institute of Medical Sciences (RMRIMS), Patna, Bihar, India, as described previously in detail (53). The study was approved by the local Institutional Ethical Committee of the RMRIMS, under Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. The sensitive and resistant isolates were finally maintained in M199 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco), 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.2), 4 mM NaHCO3, 100 U/ml of penicillin G sodium (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 mg/ml of streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1% penicillin (50 U/ml)–streptomycin (50 mg/ml) solution (Sigma). The cultures were maintained in a biological oxygen demand (BOD) incubator (Thermotech) at 24 ± 1°C for 4 to 5 days as described by Equbal et al. (54).

Sensitivity test for L. donovani promastigotes.

Stationary-phase cultures of L. donovani promastigotes (2 × 106 cells [MHOM/IN/83/Ag83]) were investigated by incubating different concentrations of procured compounds (5 to 320 μM) in M199 medium (supplemented with 10% FBS) at 24-h intervals for 5 consecutive days. Parasites not treated with any compounds were taken as the negative control, whereas those treated with miltefosine (the current antileishmanial drug) were taken as the positive control in the experimental set. The viability of parasites was evaluated as described previously (16) by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay, which is an enzyme-based quantitative colorimetric method that relies on cleavage of the MTT into tetrazolium salt (formazan), forming dark blue formazan crystals by the mitochondrial enzyme succinate dehydrogenase, which is found only in living cells (55). The quantity of formazan formed is directly proportional to the number of metabolically active cells. The results were analyzed, and the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of inhibitors was determined.

Cytotoxicity assays.

To determine the cytotoxicity of compounds, BALB/c mice were induced with 2% soluble starch, and peritoneal macrophages were harvested after 24 h by lavage in ice-cold RPMI 1640 medium. Macrophages were diluted to 5 × 105 cells/ml in medium (RPMI 1640 plus 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum), seeded in 8-well Lab-Tek chambers (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) at a density of 104 macrophages/well, and allowed to adhere overnight in a humidified 5% CO2–air atmosphere at 37°C. After 20 h, the medium was replaced with fresh medium and incubated with various concentrations of compounds for 48 h. Cytotoxicity of compounds was determined by examining cell morphology, shape, and integrity under a microscope after Giemsa staining (56).

Ex vivo assay.

The starch-elicited macrophages were harvested, seeded, and infected with stationary-phase Leishmania promastigotes (at a ratio of 1:10 macrophages to parasites) (53). The infected macrophages were exposed to 20 to 100 μM inhibitors for 24 h, the sensitivity of intracellular amastigotes was determined microscopically after Giemsa staining by calculating the number of amastigotes per 100 macrophages, and then the IC50 was determined. The percentages of infected macrophages in the control experimental set and the positive control were determined as described previously (53, 56).

Purification and enzymatic assay of rLdAPx.

The LdAPx protein was purified as described in a previous study by Kumar et al. (9) under native conditions in phosphate buffer. The activity of recombinant LdAPx (rLdAPx [10 μM]) was calculated using a fixed concentration of ascorbate (100 μM) in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) at 25°C, and the reaction was started by adding H2O2 (10 μM). The peroxidase activity of the whole reaction mixture was measured at 290 nm for ascorbate oxidation using a spectrophotometric assay.

To confirm the actual inhibition of rLdAPx by the identified inhibitors, the relative activity of rLdAPx was measured at a fixed concentration of inhibitors (5 μM), and the kinetic parameters Km and Vmax for the substrate (H2O2) were evaluated by fitting the Michaelis-Menten equation. Lineweaver-Burk plots were used to determine the mode of inhibition, and further inhibitory constants (Kis) were calculated.

MD simulation of protein-ligand complex.

To explore the binding mode and interaction pattern of identified inhibitors, MD simulation was performed for protein-ligand complex for 30 ns using Desmond v4.2 (57). For simulation, protein was prepared at a physiological pH of 7.4, and the protein-ligand complex was solvated (TIP3P water model) inside the orthorhombic box (10 Å). In addition, the system was neutralized by adding Na+ and Cl− ions. The solvated system was relaxed using the relaxation protocol implemented in Desmond v4.2. Finally, a production simulation for 30 ns was performed using the NPT ensemble with isotropic coupling at a constant temperature of 300°K and a pressure of 1 atm (58). Energy and trajectory were saved every 10 ps and at 20-ps time intervals, respectively. The trajectory for RMSD and the interaction of ligand with protein were visualized in Maestro.

Comparative study with human peroxidase (Prx).

APx is not present in humans (9, 20), but the closest human homolog, peroxiredoxin-1 (Prx) (NP_859048), was compared structurally with LdAPx to eliminate the probability of adverse effects. The binding pocket of human Prx (PDB 4XCS) was obtained through SiteMap (Schrödinger v9.6). Finally, experimentally identified inhibitors of LdAPx were studied within human Prx as well as the LdAPx binding pocket to estimate the binding differences using the same computational protocol applied with LdAPx.

Inhibitor assay with AmB-sensitive and -resistant parasites.

To study the effect of inhibitors on strain reversion properties, the AmB-sensitive and -resistant parasites (2 × 106 for each set) were incubated for 4 h at 25°C in a BOD incubator prior to AmB treatment. The parasites were subsequently washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS [pH 7.2]) and treated with AmB (0.125 μg/ml) as described earlier (9). The LD50s of AmB-sensitive and -resistant parasites were recorded.

Measurement of ROS.

To measure intracellular oxidant levels, the cell-permeable probe 2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used, which on oxidation becomes the highly fluorescent compound dichlorofluorescein (DCF) (59). The AmB-sensitive and -resistant parasites (2 × 106 for each set) were treated with inhibitors for 4 h and incubated in a BOD incubator at 25°C. Subsequently, the parasites were washed with PBS (pH 7.2) and treated with 0.125 μg/ml AmB for 24 h. Then the cells were incubated by adding 0.4 mM H2DCFDA for 15 min in the dark. Afterward cells were washed with PBS (pH 7.2), lysed with lysis buffer (potassium hydrogen phosphate and EDTA), and sonicated 2 to 3 times for 30 s after a 45-s break, until the sample became clear. Thereafter, the cells were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, and supernatant was collected to measure the fluorescence intensity using a spectrofluorometer (LS55; PerkinElmer) with excitation/emission (ex/em) λ = 503/529 nm in relative fluorescence units (RFU). The reagent blank was prepared with 0.4 mM H2DCFDA in lysis buffer as published earlier (29).

Mitochondrial peroxidase activity.

For mitochondrial peroxidase activity, 2 ml of AmB-sensitive and -resistant parasites (1 × 106 cells/ml) was incubated with inhibitors for 4 h. Thereafter, the cells were washed with PBS (pH 7.2), treated with AmB (0.125 μg/ml) for 24 h, and then incubated with 6 μM dihydrorhodamine 123 (ex/em λ = 488/525) for 25 min at 30°C. Again the cells were washed in PBS, and the fluorescence was measured subsequently using a spectrofluorometer (LS55; PerkinElmer) (60).

Measurement of GSH content.

The cellular GSH content of preincubated AmB-sensitive and -resistant parasites was measured with a GSH detection kit (Clontech). The parasites (2 × 106 cells) treated with inhibitors for 4 h were subsequently washed with PBS (pH 7.2), and afterward AmB (0.125 μg/ml) was added. After 24 h, these cells were pelleted and lysed, cell lysate was incubated with monochlorobimane dye (2 mM) for 1 h at 37°C, and the GSH level was monitored at ex/em λ = 395/480 nm with a fluorescence plate reader as reported earlier (29).

Measurement of total fluorescent lipid peroxidation product.

The total fluorescent lipid peroxidation product was estimated as described previously (61). Briefly, the AmB-treated sensitive and resistant promastigotes (107) preincubated with inhibitor (ASN13153257) for 4 h were pelleted down and washed twice with PBS. For lysis, the pellet was further suspended in 2 ml of 15% SDS in PBS solution. The fluorescence intensities of the total lipid peroxidation products were estimated with excitation at 360 nm and emission at 430 nm. Each measurement was performed in triplicate; data are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD).

Detection of phosphatidylserine exposure.

To discriminate among apoptotic cells (annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC] positive and propidium iodide [PI] negative) and live cells (annexin V-FITC and PI negative), the annexin V-FITC conjugate was used in conjunction with PI. Control and inhibitor-pretreated (14 μM I1) resistant and sensitive parasites after AmB treatment were assessed for binding with annexin V-FITC and PI using the Annexin V-Fluos staining kit (Roche) following the manufacturer's protocol. The percentage of apoptotic cells was acquired from individual gated populations in a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS), and results were analyzed with BD FACS Diva software v6.2.1 (BD Bioscience, USA). FL1 log data (x axis) versus the FL2 log data (y axis) were recorded and displayed.

Detection of metacaspase-like protease activity.

Metacaspase-like protease activity in AmB-sensitive and -resistant parasites as well as the LdAPx inhibitor-pretreated (14 μM I1) set after AmB treatment was measured using the Boc-Gly-Arg-Arg-3-methylcoumaryl-7-amide (Boc-GRR-AMC) substrate as described previously (9).

DNA fragmentation analysis.

DNA fragmentation was performed in AmB-sensitive and -resistant parasites and inhibitor-pretreated (14 μM I1) sensitive and resistant parasites after AmB treatment. The aliquots of the isolated DNA from respective samples were electrophoresed in 1.5% agarose (Sigma) gel to check the fragmentation of DNA as described previously (9).

Assay of membrane integrity.

To determine membrane integrity, untreated and inhibitor-treated (14 μM I1) AmB-sensitive and -resistant promastigotes (1 × 106 cells/ml) after AmB exposure were incubated for 4 h, and membrane integrity was assayed as described previously by our group (32). The release of lactate dehydrogenase from the cells with damaged membrane was measured by CytoTox assay kit (Promega) following the manufacturer's instructions. Promastigotes treated with 1% Triton X-100 promastigotes for 15 min were taken as the positive control where 100% cell lysis occurred.

Statistical analysis.

All experiments were conducted at least in triplicate, and the results are expressed as means ± SD from three experiments. P values were considered significant at P < 0.05 (*) and P < 0.001 (**).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), Department of Health Research, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare for setting up the Biomedical Informatics Centre at RMRIMS, Patna, India. We acknowledge S. Sachchidanand for valuable suggestions and guidance for completion of this work. We also acknowledge Jagbir Singh, Ayan K. Ghosh, Kumar Abhishek, Ajay Kumar, Sudha Verma, and Pramod Kumar for technical assistance and help with manuscript preparation.

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02429-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jacobson RL. 2003. Leishmania tropica (Kinetoplastida: Trypanosomatidae)—a perplexing parasite. Folia Parasitol 50:241–250. doi: 10.14411/fp.2003.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bates PA. 2007. Transmission of Leishmania metacyclic promastigotes by phlebotomine sand flies. Int J Parasitol 37:1097–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alvar J, Yactayo S, Bern C. 2006. Leishmaniasis and poverty. Trends Parasitol 22:552–557. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alvar J, Velez ID, Bern C, Herrero M, Desjeux P, Cano J, Jannin J, den Boer M, WHO Leishmaniasis Control Team. 2012. Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PLoS One 7:e35671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kindt TJ, Goldsby RA, Osborne BA, Kuby J. 2006. Kuby immunology, 6th ed WH Freeman, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chappuis F, Sundar S, Hailu A, Ghalib H, Rijal S, Peeling RW, Alvar J, Boelaert M. 2007. Visceral leishmaniasis: what are the needs for diagnosis, treatment and control? Nat Rev Microbiol 5:873–882. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agrawal S, Rai M, Sundar S. 2005. Management of visceral leishmaniasis: Indian perspective. J Postgrad Med 51(Suppl 1):S53–S57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burchmore RJ, Barrett MP. 2001. Life in vacuoles—nutrient acquisition by Leishmania amastigotes. Int J Parasitol 31:1311–1320. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(01)00259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar A, Das S, Purkait B, Sardar AH, Ghosh AK, Dikhit MR, Abhishek K, Das P. 2014. Ascorbate peroxidase, a key molecule regulating amphotericin B resistance in clinical isolates of Leishmania donovani. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:6172–6184. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02834-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rhee SG, Yang K-S, Kang SW, Woo HA, Chang TS. 2005. Controlled elimination of intracellular H2O2: regulation of peroxiredoxin, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase via post-translational modification. Antioxid Redox Signal 7:619–626. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pal S, Dolai S, Yadav RK, Adak S. 2010. Ascorbate peroxidase from Leishmania major controls the virulence of infective stage of promastigotes by regulating oxidative stress. PLoS One 5:e11271. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adak S, Datta AK. 2005. Leishmania major encodes an unusual peroxidase that is a close homologue of plant ascorbate peroxidase: a novel role of the transmembrane domain. Biochem J 390:465–474. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sardar AH, Kumar S, Kumar A, Purkait B, Das S, Sen A, Kumar M, Sinha KK, Singh D, Equbal A. 2013. Proteome changes associated with Leishmania donovani promastigote adaptation to oxidative and nitrosative stresses. J Proteomics 81:185–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cavasotto CN, Phatak SS. 2009. Homology modeling in drug discovery: current trends and applications. Drug Discov Today 14:676–683. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drenth J. 2007. Principles of protein X-ray crystallography. Springer Verlag, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ansari MY, Equbal A, Dikhit MR, Mansuri R, Rana S, Ali V, Sahoo GC, Das P. 2016. Establishment of correlation between in-silico and in-vitro test analysis against Leishmania HGPRT to inhibitors. Int J Biol Macromol 83:78–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sahoo GC, Dikhit MR, Rani M, Ansari MY, Jha C, Rana S, Das P. 2013. Analysis of sequence, structure of GAPDH of Leishmania donovani and its interactions. J Biomol Struct Dyn 31:258–275. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2012.698189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gumiero A, Murphy EJ, Metcalfe CL, Moody PC, Raven EL. 2010. An analysis of substrate binding interactions in the heme peroxidase enzymes: a structural perspective. Arch Biochem Biophys 500:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muralidharan AR, Selvaraj C, Singh SK, Sheu J-R, Thomas PA, Geraldine P. 2015. Structure-based virtual screening and biological evaluation of a calpain inhibitor for prevention of selenite-induced cataractogenesis in an in vitro system. J Chem Infect Model 55:1686–1697. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilkinson SR, Obado SO, Mauricio IL, Kelly JM. 2002. Trypanosoma cruzi expresses a plant-like ascorbate-dependent hemoperoxidase localized to the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:13453–13458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202422899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]