ABSTRACT

Gepotidacin is a first-in-class, novel triazaacenaphthylene antibiotic that inhibits bacterial DNA replication and has in vitro activity against susceptible and drug-resistant pathogens. Reference in vitro methods were used to investigate the MICs and minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBCs) of gepotidacin and comparator agents for Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Escherichia coli. Gepotidacin in vitro activity was also evaluated by using time-kill kinetics and broth microdilution checkerboard methods for synergy testing and for postantibiotic and subinhibitory effects. The MIC90 of gepotidacin for 50 S. aureus (including methicillin-resistant S. aureus [MRSA]) and 50 S. pneumoniae (including penicillin-nonsusceptible) isolates was 0.5 μg/ml, and for E. coli (n = 25 isolates), it was 4 μg/ml. Gepotidacin was bactericidal against S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, and E. coli, with MBC/MIC ratios of ≤4 against 98, 98, and 88% of the isolates tested, respectively. Time-kill curves indicated that the bactericidal activity of gepotidacin was observed at 4× or 10× MIC at 24 h for all of the isolates. S. aureus regrowth was observed in the presence of gepotidacin, and the resulting gepotidacin MICs were 2- to 128-fold higher than the baseline gepotidacin MICs. Checkerboard analysis of gepotidacin combined with other antimicrobials demonstrated no occurrences of antagonism with agents from multiple antimicrobial classes. The most common interaction when testing gepotidacin was indifference (fractional inhibitory concentration index of >0.5 to ≤4; 82.7% for Gram-positive isolates and 82.6% for Gram-negative isolates). The postantibiotic effect (PAE) of gepotidacin was short when it was tested against S. aureus (≤0.6 h against MRSA and MSSA), and the PAE–sub-MIC effect (SME) was extended (>8 h; three isolates at 0.5× MIC). The PAE of levofloxacin was modest (0.0 to 2.4 h), and the PAE-SME observed varied from 1.2 to >9 h at 0.5× MIC. These in vitro data indicate that gepotidacin is a bactericidal agent that exhibits a modest PAE and an extended PAE-SME against Gram-positive and -negative bacteria and merits further study for potential use in treating infections caused by these pathogens.

KEYWORDS: gepotidacin, minimum bactericidal activity, postantibiotic effect

INTRODUCTION

Gepotidacin (formerly GSK2140944) is a novel, first-in-class triazaacenaphthylene antibacterial that selectively inhibits bacterial DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV by a unique mechanism not used by any currently approved human therapeutic agent (1). The novel binding mode of these novel bacterial type II topoisomerase inhibitors (NBTIs) has been shown to differ from that of the fluoroquinolones (1). Because of its novel mode of action, gepotidacin is active in vitro against target pathogens carrying determinants of resistance to established antibacterials, including fluoroquinolones, and has demonstrated in vitro activity against key pathogens, including drug-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Escherichia coli, associated with a range of conventional and biothreat infections (2, 3).

In this study, reference in vitro methods were used to evaluate the MICs and minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBCs) of gepotidacin and comparator agents for S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, and E. coli. Gepotidacin in vitro activity was also evaluated by using time-kill kinetics and broth microdilution checkerboard methods for synergy testing and for postantibiotic and subinhibitory effects.

RESULTS

MIC/MBC studies.

The MIC50/90s of gepotidacin for all of the S. aureus, levofloxacin-resistant S. aureus, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA), and penicillin-susceptible and -nonsusceptible S. pneumoniae (penicillin MIC, ≥0.25 μg/ml) isolates tested were all 0.25/0.5 μg/ml (Table 1). Of the S. pneumoniae isolates tested, two were levofloxacin resistant and exhibited MICs of 8 and 32 μg/ml and MBCs of 16 and 32 μg/ml, respectively (data not shown). For these two isolates, the MICs of gepotidacin were 1 and 0.5 μg/ml and the MBCs were 1 and 0.5 μg/ml, respectively. In this study, two Streptococcus pyogenes isolates were also tested and their respective gepotidacin/levofloxacin/linezolid MICs were 0.12/0.5/0.5 and 0.5/0.5/1 μg/ml; no MBCs were determined for these two strains (data not shown). For E. coli, the gepotidacin MIC50/90s were 2/4 μg/ml (Table 1). Of the E. coli isolates tested, five were extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producers, two of which were levofloxacin resistant. Four of these isolates had gepotidacin MICs of ≤2 μg/ml, and one had a gepotidacin MIC of 8 μg/ml. The gepotidacin MBC90 values for all of the S. aureus, levofloxacin-resistant S. aureus, and penicillin-susceptible and -nonsusceptible S. pneumoniae (penicillin MIC, ≥0.25 μg/ml) isolates were identical to the MIC90 of 0.5 μg/ml. The gepotidacin MBC90 for MSSA was 1 μg/ml, and the MBC90 for E. coli was >32 μg/ml. Gepotidacin was bactericidal against 88% (22/25) of the E. coli isolates tested, exhibiting an MBC/MIC ratio of ≤2. Three isolates exhibited a gepotidacin MBC/MIC ratio of >16 (data not shown). The gepotidacin MBCs for the five ESBL-producing E. coli isolates were within 1 doubling dilution of the MIC, except for one isolate with a gepotidacin MIC of 1 μg/ml and an MBC of >32 μg/ml. Levofloxacin was bactericidal, as evidenced by having MIC50/90 and MBC50/90 values for each organism group that were within 2-fold of each other (Table 1). The linezolid MBCs for S. aureus were >16-fold higher than the respective MICs.

TABLE 1.

Summary of MICs and MBCs of gepotidacin and comparators

| Organism (no. of isolates) and drug | MIC50 (μg/ml) | MIC90 (μg/ml) | MBC50 (μg/ml) | MBC90 (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus (50) | ||||

| Gepotidacin | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.25 | 32 | 0.5 | 32 |

| Linezolid | 1 | 2 | >32 | >32 |

| LEV-nonsusceptible S. aureus (22) | ||||

| Gepotidacin | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Levofloxacin | 8 | >32 | 16 | >32 |

| Linezolid | 1 | 2 | >32 | >32 |

| MRSA (25) | ||||

| Gepotidacin | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Levofloxacin | 8 | >32 | 8 | >32 |

| Linezolid | 1 | 2 | >32 | >32 |

| MSSA (25) | ||||

| Gepotidacin | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.25 | 4 | 0.25 | 8 |

| Linezolid | 1 | 2 | >32 | >32 |

| S. pneumoniae (50) | ||||

| Gepotidacin | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Levofloxacin | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae (20) | ||||

| Gepotidacin | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Levofloxacin | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| E. coli (25) | ||||

| Gepotidacin | 2 | 4 | 2 | >32 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.5 | 16 | 0.5 | 16 |

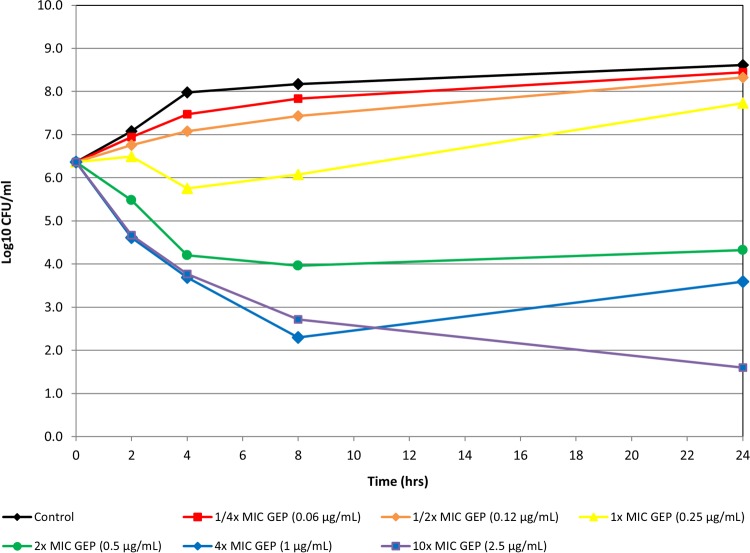

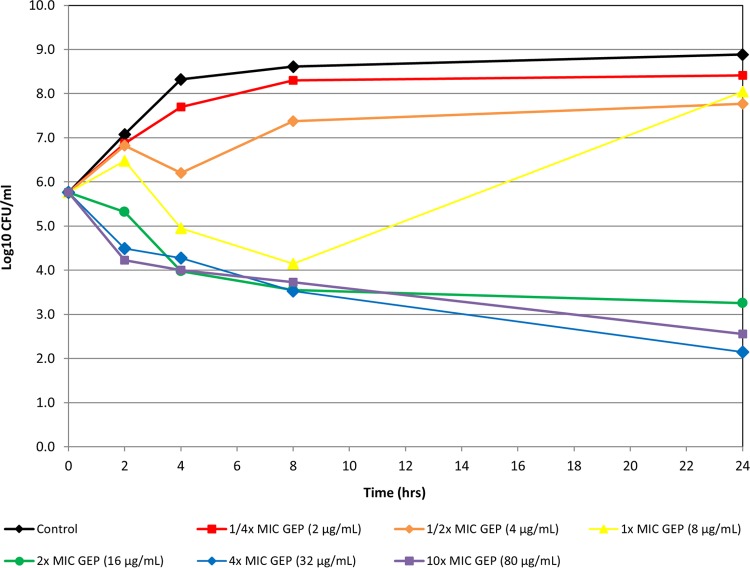

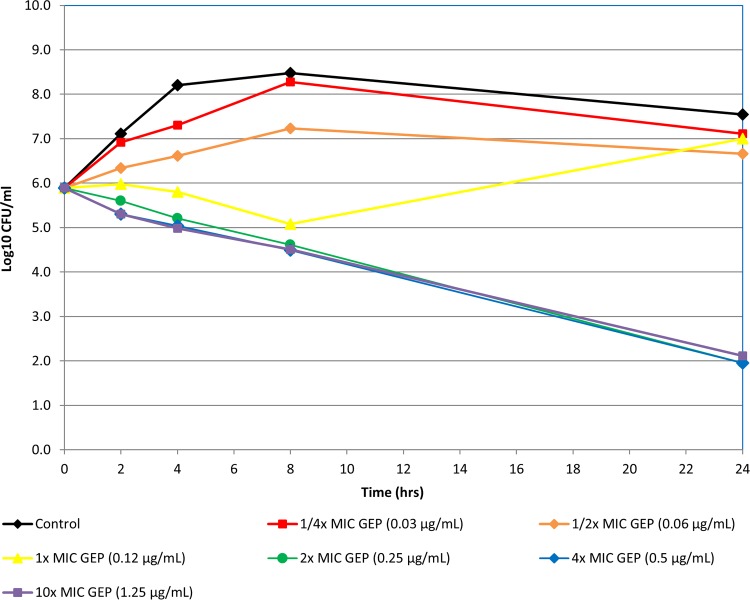

Time-kill studies.

Static in vitro time-kill experiments indicated that gepotidacin was bactericidal against 12 bacterial isolates, including S. aureus (MRSA/MSSA), penicillin-intermediate and -resistant isolates of S. pneumoniae, and E. coli isolates that included ESBL producers (Fig. 1 to 3 show representative examples). Bactericidal activity was observed at 4× or 10× concentrations at 24 h for all isolates.

FIG 1.

Time-kill curve of gepotidacin against S. aureus isolate 139.

FIG 2.

Time-kill curve of gepotidacin against E. coli isolate 3773.

FIG 3.

Time-kill curve of gepotidacin against S. pneumoniae isolate ATCC 49619.

Of the six S. aureus isolates tested in the time-kill kinetic assays, one of the three MSSA isolates and two of the three MRSA isolates were levofloxacin resistant. Regrowth of four of the six isolates of S. aureus tested in the presence of gepotidacin at 4× MIC was observed. In two of the strains, the regrowth that occurred at 4× MIC ranged from 0.9 to 1.1 log10 CFU/ml greater than the starting inoculum concentration. In the other two strains, the regrowth that occurred at 4× MIC was still below the initial inoculum concentration, as shown in Fig. 1, in which there was a slight increase in growth from the 8-h to the 24-h time point. Regrowth (0.2 log10 CFU/ml greater than the starting inoculum) was also observed in one replicate of one of the S. aureus isolates tested in the presence of gepotidacin at 10× MIC. For all six S. aureus isolates tested, colonies from aliquots taken from 24-h time-kill curve tubes containing gepotidacin at 0.25× to 10× MIC grew on an agar screen plate containing gepotidacin at 4× MIC. When colonies from these plates were selected and MICs were determined, the resulting gepotidacin MICs (0.5 to 64 μg/ml) were 2- to 128-fold higher than the baseline gepotidacin MICs (0.25 to 0.5 μg/ml). For E. coli and S. pneumoniae, the agar screen showed very few colonies with elevated gepotidacin MICs relative to the baseline. The molecular basis of any reduced susceptibility was not characterized in this study.

Checkerboard synergy studies and postantibiotic and subinhibitory effects.

Gepotidacin and various comparator antimicrobials were evaluated in combinations for their activity against 10 S. aureus, 10 S. pneumoniae, 2 S. pyogenes, 5 E. coli, and 2 Haemophilus influenzae isolates by checkerboard synergy studies. No instances of antagonism occurred with any of the organism and antimicrobial combinations tested. Indifference was the most common interaction noted when testing gepotidacin in vitro combined with other agents (82.7%; see Table S1 in the supplemental material). For PAE and PAE–sub-MIC effect (SME) studies, seven isolates were chosen: three S. aureus isolates (one methicillin and levofloxacin susceptible, one methicillin and levofloxacin resistant, and one methicillin susceptible and levofloxacin resistant), two S. pneumoniae isolates (one penicillin and levofloxacin susceptible, one penicillin and levofloxacin resistant), and two E. coli isolates (one levofloxacin susceptible, one levofloxacin-resistant ESBL producer) (Tables 2 and 3). The in vitro PAE of gepotidacin against S. aureus was short (0 to 0.6 h against MRSA and MSSA; Table 2), and the in vitro PAE-SME was extended (>8 h for all three isolates at 0.5× MIC; Table 3). The in vitro PAE of gepotidacin against S. pneumoniae was modest (0.7 to 1.6 h) with an extended in vitro PAE-SME (>5.5 h at 0.5× MIC) (Tables 2 and 3). The in vitro PAE of gepotidacin against E. coli was modest (1.2 to 2.2 h) with an extended in vitro PAE-SME (>4.3 h at 0.5× MIC for wild type and ESBL-producing isolates) (Tables 2 and 3).

TABLE 2.

Summary of PAE results of time-kill curves of gepotidacin and comparator agents after 1 h of exposure at 1×, 5×, and 10× baseline MICsa

| Organism and isolate (phenotype) | Gepotidacin |

Levofloxacin |

Linezolid |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline MIC (μg/ml) | PAE (h) at: |

Baseline MIC (μg/ml) | PAE (h) at: |

Baseline MIC (μg/ml) | PAE (h) at: |

|||||||

| 1× MIC | 5× MIC | 10× MIC | 1× MIC | 5× MIC | 10× MIC | 1× MIC | 5× MIC | 10× MIC | ||||

| S. aureus | ||||||||||||

| ATCC 29213 (MSSA LEVs) | 0.25 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.25 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 2.4 | 2 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 1263 (MRSA LEVr) | 0.25 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.0 | 0.6 | NT | 1 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| 12605 (MSSA LEVr) | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 16 | 0.1 | 0.1 | NT | 1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.7 |

| S. pneumoniae | ||||||||||||

| 35841 (PENs LEVs) | 0.5 | 0.7 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.6 | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| 7114 (PENr LEVr) | 2 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 32 | 0.2 | 0.7 | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| E. coli | ||||||||||||

| ATCC 25922 (LEVs) | 2 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 0.03 | 0.4 | ND | ND | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| 3904 (ESBL-positive LEVr) | 4 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 16 | 0.6 | 1.1 | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

Abbreviations: LEV, levofloxacin; PEN, penicillin; S, susceptible; r, resistant; NT, not tested; ND, not determinable.

TABLE 3.

Summary of PAE-SME results of time-kill curves of gepotidacin and comparators after 1 h of exposure at 5× MIC and antimicrobial agent addition at 0.25× or 0.5× MICa

| Organism and isolate (phenotype) | Gepotidacin |

Levofloxacin |

Linezolid |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5× MIC (μg/ml) | PAE-SME (h) at: |

5× MIC (μg/ml) | PAE-SME (h) at: |

5× MIC (μg/ml) | PAE-SME (h) at: |

||||

| 5× + 0.25× MIC | 5× + 0.5× MIC | 5× + 0.25× MIC | 5× + 0.5× MIC | 5× + 0.25× MIC | 5× + 0.5× MIC | ||||

| S. aureus | |||||||||

| ATCC 29213 (MSSA LEVs) | 1.25 | 2.2 | >9 | 1.25 | 2.5 | >9 | 10 | 1.5 | 9.0 |

| 1263 (MRSA LEVr) | 1.25 | 1.4 | >8 | 40 | 0.9 | >8 | 5 | 1.9 | 3.7 |

| 12605 (MSSA LEVr) | 2.5 | 8.0 | >8 | 80 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 5 | 1.0 | 4.5 |

| S. pneumoniae | |||||||||

| 35841 (PENs LEVs) | 2.5 | 6.4 | >6.4 | 5 | 2.3 | 5.0 | NT | NT | NT |

| 7114 (PENr LEVr) | 10 | 5.4 | >5.5 | 160 | 2.3 | >5.5 | NT | NT | NT |

| E. coli | |||||||||

| ATCC 25922 (LEVs) | 10 | 3.0 | >4.3 | 0.15 | ND | ND | NT | NT | NT |

| 3904 (ESBL-positive LEVr) | 20 | 6.6 | >6.6 | 80 | 1.9 | 4.1 | NT | NT | NT |

Abbreviations: LEV, levofloxacin; PEN, penicillin; S, susceptible; r, resistant; NT, not tested; ND, not determinable.

The in vitro PAE of levofloxacin or linezolid against S. aureus was short (0 to 2.4 h against MRSA and MSSA for levofloxacin and 0.1 to 0.7 h for linezolid) (Table 2). The in vitro PAE-SME observed when levofloxacin and linezolid were tested against S. aureus varied. At 0.5× MIC, the PAE-SME of levofloxacin ranged from 1.2 to >9 h and that of linezolid ranged from 3.7 to 9 h (Table 3). The PAE of levofloxacin against S. pneumoniae was modest (0.2 to 1.6 h), with an extended in vitro PAE-SME (5.0 to >5.5 h at 0.5× MIC) (Tables 2 and 3).

DISCUSSION

Gepotidacin is the first compound in the novel triazaacenaphthylene class of antibacterials and acts by selective inhibition of bacterial DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV (1). Its mode of action differs from that of fluoroquinolones, and this difference allows for activity against fluoroquinolone-resistant strains (1, 2). It is active against Gram-positive and -negative bacteria, including target multidrug-resistant pathogens (2). The gepotidacin MIC90 values for S. aureus and levofloxacin-resistant S. aureus were shown to be the same at 0.5 μg/ml (2), and those for E. coli and levofloxacin-resistant E. coli were 2 and 4 μg/ml, respectively (2). Gepotidacin has also been shown to be active in vitro against Neisseria gonorrhoeae, including fluoroquinolone-resistant strains (3–5).

In our study, the MIC50/90 values were 0.25/0.5 μg/ml for the staphylococcal and streptococcal isolates tested and 2/4 μg/ml for the E. coli isolates tested. These data are consistent with data Biedenbach et al. reported, which also demonstrated that the activity of gepotidacin did not vary when it was tested against fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates (2). The bactericidal activity of gepotidacin in our study was shown in time-kill curves and in how similar the MBCs and MICs were, regardless of the patterns of isolate resistance to other antibacterial classes.

It should be noted that in the time-kill assays with S. aureus, although there were decreases in the number of viable CFU/ml, for some isolates, there was evidence that rebound growth occurred. Selection on agar plates containing gepotidacin at 4× MIC for all six S. aureus isolates indicated that there were viable organisms with MICs elevated from the baseline at the 24-h time point. Molecular characterization to determine the mechanism of the reduced susceptibility of these isolates was not performed. Previously, Lahiri et al. showed for S. aureus that after initial bacterial killing in time-kill kinetics, a partial rebound of growth occurred when testing a representative NBTI compound (6). They also noted variations in the frequency of spontaneous resistance when testing S. aureus against representative NBTIs and found that the mutations that occurred were in the gyrase subunit. The frequency of selection of spontaneous resistant mutants ranged from 1.7 × 10−8 to <5.5 × 10−10.

In studies to characterize the development of resistance to another NBTI compound (NBTI 5463) in E. coli, it was demonstrated that single-step mutations resulting in elevated MICs could not be selected (7). Mutations in both target enzymes (gyrase and topoisomerase IV) were required for significant increases in the MIC. Similarly, we found that resistant mutants selected with gepotidacin at 4× MIC from the 24-h time-kill kinetic assays were less common in E. coli. For Pseudomonas aeruginosa, it was also shown that regrowth would occur when testing NBTI 5463 in time-kill kinetics (8). Resistance selection studies indicated that the mutations that occurred were in the nfxB gene, a regulator of the MEXCD-OprJ efflux system (8).

Gepotidacin also exhibited a modest in vitro PAE with an extended PAE-SME when tested against S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, and E. coli. These data confirm the strategy of synthesizing a compound to inhibit DNA synthesis through a different mode than that of classical fluoroquinolones leads to in vitro activity against fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates while retaining its bactericidal nature and PAE.

Antimicrobials are frequently used in combination, so knowing if drug interactions may occur is of interest. In this study, the in vitro interaction of gepotidacin was mostly indifferent when it was tested in combination with other antibiotic classes (macrolides, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, β-lactams, aminoglycosides, oxazolidinones, folate acid antagonists) against Gram-positive and -negative bacteria. No antagonism was seen in the organism and drug combinations tested. In some instances, inactivity of comparator agents made measuring the effect of the interaction impossible because of off-scale MICs.

In summary, in vitro, gepotidacin was active and bactericidal against the contemporary isolates of S. aureus (including MRSA), S. pneumoniae (including penicillin-resistant isolates), and E. coli (including ESBL-producing isolates) tested. Against the isolates tested, gepotidacin exhibited a modest PAE and extended PAE-SME and was shown in checkerboard synergy studies with multiple comparator agents to exhibit no antagonism with the agents tested. The broad-spectrum profile and bactericidal nature of gepotidacin demonstrate that it merits further study in clinical indications challenged by Gram-positive and selected Gram-negative multidrug-resistant bacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reference in vitro broth microdilution methods.

Reference in vitro broth microdilution methods were used to evaluate the MICs and MBCs of gepotidacin and comparator agents for S. aureus (n = 50 isolates; 25 MRSA and 25 MSSA isolates, 22 of which were nonsusceptible to levofloxacin), S. pneumoniae (n = 50 isolates; 25 penicillin-susceptible and 25 penicillin-nonsusceptible [MIC, ≥0.25 μg/ml] isolates), and E. coli (n = 25 isolates; including 5 ESBL-producing isolates) (9–11). A drug was considered to exhibit bactericidal activity against a particular isolate when the MBC/MIC ratio was ≤4 (10). For all of the in vitro assays described in this study, S. aureus and E. coli were tested in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth and S. pneumoniae was tested in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth supplemented with lysed horse blood (9).

Time-kill kinetics.

For time-kill kinetics, gepotidacin and comparator agents were tested against three isolates each of S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, and E. coli at 0.25×, 0.5×, 1×, 2×, 4×, and 10× MIC for each isolate and sampled at time zero (T0), T2 (2 h later), T4, T8, and T24. Time-kill curves were determined in duplicate. Bactericidal activity was defined as a ≥3-log reduction in bacterial counts (log10 CFU/ml) (13). Aliquots from all gepotidacin concentration tubes at the 24-h time point were plated onto agar plates containing gepotidacin at 4× MIC to screen for changes in gepotidacin MICs.

Synergy studies.

Checkerboard synergy testing was performed by broth microdilution (12, 13). Gepotidacin was tested alone and in combination with aztreonam, linezolid, vancomycin, gentamicin, moxifloxacin, levofloxacin, azithromycin, tetracycline, ceftriaxone, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole against S. aureus (n = 10), S. pneumoniae (n = 10), and S. pyogenes (n = 2); with gentamicin, aztreonam, moxifloxacin, levofloxacin, tetracycline, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole against E. coli (n = 5); and with gentamicin, aztreonam, moxifloxacin, levofloxacin, azithromycin, tetracycline, ceftriaxone, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole against H. influenzae (n = 2). The interpretation of the fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) was applied as follows: synergy, ≤0.5; indifference, >0.5 to ≤4.0; antagonism, >4.0.

PAE and PAE-SME.

Gepotidacin was tested by using time-kill methods to determine PAEs and PAE-SMEs (14–16). In addition to gepotidacin, the comparators linezolid and levofloxacin were tested against S. aureus (n = 3) and levofloxacin was tested against S. pneumoniae (n = 2) and E. coli (n = 2). The organisms were exposed to gepotidacin or the comparator agent for 1 h at 1×, 5×, and 10× MIC, as determined by broth microdilution testing. Only the initial 5× exposure was used for the PAE-SME, followed by 0.25× or 0.5× MIC reexposure. Antibiotics were removed by dilution to 1:1,000 in medium. Colony counts were performed at T0 (before antimicrobial exposure) and T1 (after antimicrobial exposure). Colony counts were determined immediately after the organisms were washed and resuspended and after each subsequent hour until visible turbidity was observed for up to 9 h.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK; Collegeville, PA) and has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response, Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, under contract HHSO100201300011C.

JMI Laboratories, Inc., contracted to perform services in 2016 for Achaogen, Actelion, Allecra, Allergan, Ampliphi, API, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Basilea, Bayer, BD, Biomodels, Cardeas, CEM-102 Pharma, Cempra, Cidara, Cormedix, CSA Biotech, Cubist, Debiopharm, Dipexium, Duke, Durata, Entasis, Fortress, Fox Chase Chemical, Medpace, Melinta, Merck, Micurx, Motif, N8 Medical, Nabriva, Nexcida, Novartis, Paratek, Pfizer, Polyphor, Rempex, Scynexis, Shionogi, Spero Therapeutics, Symbal Therapeutics, Synolgoic, TGV Therapeutics, The Medicines Company, Theravance, ThermoFisher, Venatorx, Wockhardt, and Zavante. Some JMI employees are advisors/consultants for Allergan, Astellas, Cubist, Pfizer, Cempra, and Theravance. There are no speakers' bureaus or stock options to declare.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00468-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bax BD, Chan PF, Eggleston DS, Fosberry A, Gentry DR, Gorrec F, Giordano I, Hann MM, Hennessy A, Hibbs M, Huang J, Jones E, Jones J, Brown KK, Lewis CJ, May EW, Saunders MR, Singh O, Spitzfaden CE, Shen C, Shillings A, Theobald AJ, Wohlkonig A, Pearson ND, Gwynn MN. 2010. Type IIA topoisomerase inhibition by a new class of antibacterial agents. Nature 466:935–940. doi: 10.1038/nature09197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biedenbach DJ, Bouchillon SK, Hackel M, Miller LA, Scangarella-Oman NE, Jakielaszek C, Sahm DF. 2016. In vitro activity of gepotidacin, a novel triazaacenaphthylene bacterial topoisomerase inhibitor, against a broad spectrum of bacterial pathogens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:1918–1923. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02820-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones RN, Fedler KA, Scangarella-Oman NE, Ross JE, Flamm RK. 2016. Multicenter investigation of gepotidacin (GSK2140944) agar dilution quality control determinations for Neisseria gonorrhoeae ATCC 49226. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:4404–4406. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00527-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flamm RK, Sader HS, Rhomberg PR, Scangarella-Oman NE, Farrell DJ. 2016. Gepotidacin (GSK2140944) in vitro activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (MBC/MIC, kill kinetics, checkerboard, PAE/SME tests), abstr 460. ASM Microbe, Boston, MA, 16 to 20 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farrell DJ, Sader HS, Rhomberg PR, Scangarella-Oman NE, Flamm RK. 2016. Gepotidacin (GSK2140944) in vitro activity against Neisseria gonorrhoeae (MIC/MBC, kill kinetics, checkerboard, PAE/SME tests), abstr 461. ASM Microbe, Boston, MA, 16 to 20 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lahiri SD, Kutschke A, McCormack K, Alm RA. 2015. Insights into the mechanism of inhibition of novel bacterial topoisomerase inhibitors from characterization of resistant mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:5278–5287. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00571-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nayar AS, Dougherty TJ, Reck F, Thresher J, Gao N, Shapiro AB, Ehmann DE. 2015. Target-based resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli to NBTI 5463, a novel bacterial type II topoisomerase inhibitor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:331–337. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04077-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dougherty TJ, Nayar A, Newman JV, Hopkins S, Stone GG, Johnstone M, Shapiro AB, Cronin M, Reck F, Ehmann DE. 2014. NBTI 5463 is a novel bacterial type II topoisomerase inhibitor with activity against Gram-negative bacteria and in vivo efficacy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:2657–2664. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02778-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2015. M07-A10. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard—tenth edition. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 1999. M26-A. Methods for determining bactericidal activity of antimicrobial agents; approved guideline. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2016. M100-S26. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 26th informational supplement. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koeth LM. 2016. Tests to assess bactericidal activity. In Leber AL. (ed), Clinical microbiology procedures handbook, 4th ed, vol 2 ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moody J. 2004. Susceptibility tests to evaluate synergism, p 5.12.11–15.12.23. In Isenberg HD. (ed), Clinical microbiology procedures handbook, vol 5 ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Odenholt-Tornqvist I. 1993. Studies on the postantibiotic effect and the postantibiotic sub-MIC effect of meropenem. J Antimicrob Chemother 31:881–892. doi: 10.1093/jac/31.6.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Odenholt-Tornqvist I, Lowdin E, Cars O. 1992. Postantibiotic sub-MIC effects of vancomycin, roxithromycin, sparfloxacin, and amikacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 36:1852–1858. doi: 10.1128/AAC.36.9.1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spangler SK, Lin G, Jacobs MR, Appelbaum PC. 1998. Postantibiotic effect and postantibiotic sub-MIC effect of levofloxacin compared to those of ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, azithromycin, and clarithromycin against 20 pneumococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 42:1253–1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.