ABSTRACT

Rose bengal (RB) is a halogenated xanthene dye that has been used to mediate antimicrobial photodynamic inactivation for several years. While RB is highly active against Gram-positive bacteria, it is largely inactive in killing Gram-negative bacteria. We have discovered that addition of the nontoxic salt potassium iodide (100 mM) potentiates green light (540-nm)-mediated killing by up to 6 extra logs with the Gram-negative bacteria Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the Gram-positive bacterium methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and the fungal yeast Candida albicans. The mechanism is proposed to be singlet oxygen addition to iodide anion to form peroxyiodide, which decomposes into radicals and, finally, forms hydrogen peroxide and molecular iodine. The effects of these different bactericidal species can be teased apart by comparing the levels of killing achieved in three different scenarios: (i) cells, RB, and KI are mixed together and then illuminated with green light; (ii) cells and RB are centrifuged, and then KI is added and the mixture is illuminated with green light; and (iii) RB and KI are illuminated with green light, and then cells are added after illumination with the light. We also showed that KI could potentiate RB photodynamic therapy in a mouse model of skin abrasions infected with bioluminescent P. aeruginosa.

KEYWORDS: antimicrobial photodynamic inactivation, rose bengal, Pseudomonas aeruginosa mouse infection, potassium iodide, reactive iodine species, singlet oxygen

INTRODUCTION

The rapid and seemingly unstoppable rise in the incidence of antibiotic resistance necessitates the development of alternative antimicrobial strategies (1). Antimicrobial photodynamic inactivation (aPDI) employs the combination of nontoxic dyes called photosensitizers (PS), which can be excited by harmless visible light (2). In the presence of ambient oxygen, the excited-state PS undergoes a photochemical reaction, producing reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as singlet oxygen (1O2) and hydroxyl radicals (HO˙). These highly reactive species are able to chemically attack most biomolecules, such as proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids. In principle, the damage produced by this chemical attack can kill any known type of microorganism, including Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, fungi, parasites, and viruses. However, having said that, it must be noted that there is a major difference between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (3). This difference arises because of the different structural characteristics of the cell walls of these two classes of bacterial cells. Gram-positive bacterial cell walls are highly permeable, and most dyes can diffuse easily into the cells (hence the name referring to the Gram stain). On the other hand, Gram-negative bacteria are mostly impermeable to many dyes that have anionic or neutral charges. Only dyes with pronounced cationic charges can bind and penetrate into Gram-negative bacterial cells because the double membrane presents a formidable barrier against penetration of most PS that have been developed for anticancer applications (4).

One dye that has been frequently studied for antimicrobial PDI applications is the halogenated xanthene known as rose bengal (RB) (5–9). RB (4,5,6,7-tetrachloro-2′,4′,5′,7′-tetraiodofluorescein) is a deeply colored pink compound with a variety of medical uses. It is used as a stain to identify corneal damage (10), in the diagnosis of brucellosis (11), and as a PS to mediate photochemical tissue bonding (12). It has also been used as an anticancer compound (in the dark) given as an intralesional injection into transit melanoma metastases, where it has been shown to activate an antitumor immune response (13). When used as an antimicrobial PS, RB has been found to have a major effect against Gram-positive bacteria and is also effective against fungi, such as Candida spp., but its activity against Gram-negative bacteria is minimal.

We have recently found that the nontoxic inorganic salt potassium iodide has a remarkable potentiating effect on aPDI (14). Addition of a simple KI solution to a mixture of microbial cells and many different PS (phenothiazinium dyes [15, 16], titanium dioxide photocatalysis [17], and fullerenes [18]) that are subsequently excited by light can give many log units of additional killing (up to 6 logs of extra killing). We recently showed (19) that addition of KI to the traditional anticancer, porphyrin-based PS called Photofrin (PF; porfimer sodium) allowed broad-spectrum aPDI, including the eradication of Gram-negative bacteria that were previously thought to be resistant to PF photodynamic therapy (PDT) (17). In the present study, we asked the question whether the aPDI effects of the anionic dye RB would also be potentiated by addition of KI.

RESULTS

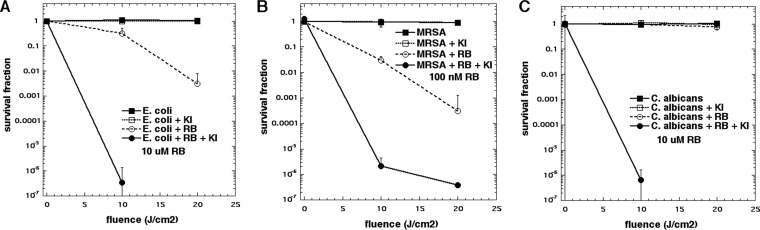

Our initial experiments involved comparison of the microbial killing achieved with increasing light doses when KI was added into the mixture of cells incubated with the appropriate concentration of RB and then illuminated with green light. Because it is known that Gram-positive bacteria are very susceptible to aPDI with anionic PS, such as RB, we needed to use only a very low concentration of 100 nM. For Escherichia coli and Candida albicans, we used a higher concentration (but not excessively high) of 10 μM. We used a 100 mM concentration of KI. The results are displayed in Fig. 1. At the lowest light dose tested (10 J/cm2), RB plus KI and light eradicated (>6 logs of killing) E. coli, while only less than 1 log of killing was found when KI was omitted (Fig. 1A). Even with 20 J/cm2, RB plus light gave only 2 logs of killing. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) was killed 1 to 2 logs by the low concentration (100 nM) of RB plus light, while the addition of KI gave 4 logs of additional killing at 10 J/cm2 and eradication at 20 J/cm2 (Fig. 1B). For C. albicans, the potentiation was even more dramatic (Fig. 1C). The lowest light dose gave eradication when KI was present, while no killing was found with RB plus light at either fluence.

FIG 1.

Effect of KI on light dose-dependent aPDI. Cells were incubated for 30 min with RB (at the specified concentration) plus 100 mM KI, and then 540-nm light was delivered (0, 10, or 20 J/cm2). Controls were cells alone or cells incubated with KI alone. (A) Gram-negative bacterium E. coli; (B) Gram-positive bacterium MRSA; (C) fungal yeast C. albicans.

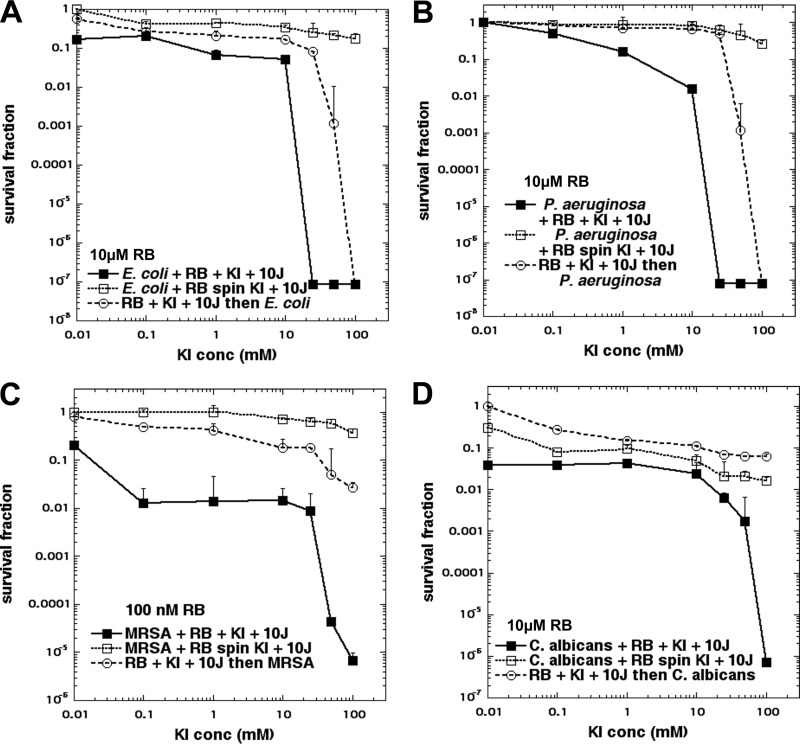

In order to distinguish between the photochemical oxidation of iodide to give molecular iodine, which is a stable molecule that can exert an antimicrobial effect, and the photochemical creation of reactive iodine species, which would be short-lived and would exert an antimicrobial effect only when the cells were present as the light was delivered, we carried out the following series of experiments. We increased the concentrations of KI, as it became apparent that surprisingly high concentrations were necessary to obtain the maximal potentiation effect. We reasoned that if more killing was observed when the cells were present during the illumination than when the cells were added after the illumination, then it could be deduced that some short-lived species as well as the stable molecular iodine were involved in the killing. In order to study to what extent the RB that was bound to the microbial cells (as opposed to the RB free in solution) was involved in the KI potentiation of aPDI, we also added a step involving the centrifugation of the cells after incubation with RB. The results are shown in Fig. 2. Figure 2A and B show the results for the Gram-negative species E. coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa treated with 10 μM RB and 10 J/cm2 of 540-nm light. The results are quite similar. When all the ingredients were present at the same time (Fig. 2A and B, closed squares), there was modest killing (1 to 2 logs) at up to 10 mM KI, but at 25 mM KI there was eradication (7 logs of killing). When the cells were added only after the KI and RB had been illuminated, there was no major killing until the KI concentration reached 50 mM (when there was 3 to 4 logs of killing), and at 100 mM KI there was eradication (Fig. 2A and B, open circles). When the cells that had been incubated with RB were centrifuged, there was virtually no killing even with 100 mM KI. This result is consistent with a lack of binding between RB and Gram-negative bacteria.

FIG 2.

Effect of spin and addition sequence on RB plus KI aPDI. RB (10 μM for Gram-negative bacteria and fungi or 100 nM for MRSA) was exposed to 10 J/cm2 of 540-nm light in the presence of different concentrations of KI. Cells (108/ml for bacteria or 107/ml for fungi) were either present during light, centrifuged before addition of KI and light, or added after light. Controls (light alone or light plus KI) showed no loss of viability (data not shown). (A) Gram-negative bacterium E. coli; (B) Gram-negative bacterium P. aeruginosa; (C) Gram-positive bacterium MRSA; (D) fungal yeast C. albicans.

Figure 2C shows the results obtained with the Gram-positive bacterium MRSA. Because MRSA is exceptionally sensitive to RB-mediated aPDI, we used the very low concentration of 100 nM RB. aPDI with a very low concentration of KI (aPDI equivalent to that with RB alone) gave 1 log of killing, and at higher concentrations (up to 25 mM KI) there were 2 logs of killing. However, at 50 and 100 mM KI, there were 5 to 6 logs of killing. When the cells were added after the light, we found only 1 to 2 logs of killing even with 100 mM KI. There was no killing after a spin.

Figure 2D shows the results obtained with C. albicans using 10 μM RB. With all ingredients present (closed squares) and with no KI, we obtained 1.5 logs of killing, and this remained the same until a KI concentration of 10 mM was reached. We began to see potentiation at 25 mM KI, and this increased until eradication was achieved with 100 mM KI. When the cells were added after light (open circles), we saw only minimal killing even at 100 mM KI. When the cells were centrifuged after incubation with RB (Fig. 2D, open squares), we saw about 1 log of killing, and this did not really increase with an increase in the KI concentration up to 100 mM.

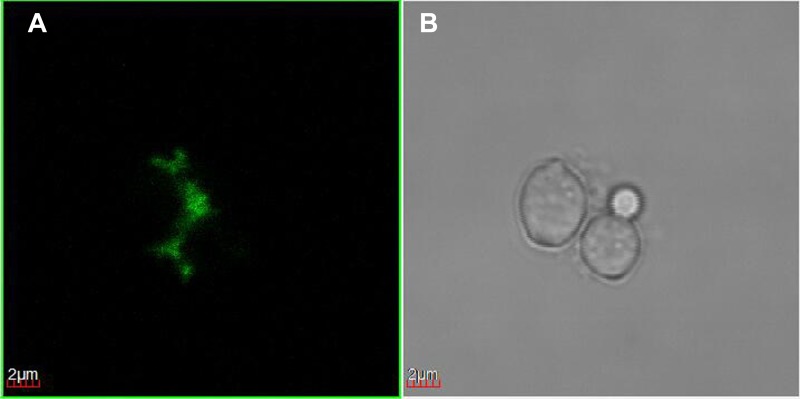

Since the results of the experiments where the cells were centrifuged after incubation with RB suggested that only C. albicans cells actually bound any RB, we carried out confocal microscopy imaging studies to look at the RB fluorescence in cells that had been centrifuged to confirm these findings. Figure 3A shows that C. albicans had a distinct green fluorescence emission around the cells, but the fluorescence did not penetrate to any great extent inside the cells.

FIG 3.

Confocal microscopy. Confocal images of C. albicans incubated with RB (10 μM) for 30 min and centrifuged. (A) Emission at 585 nm; (B) grayscale.

Mechanistic studies.

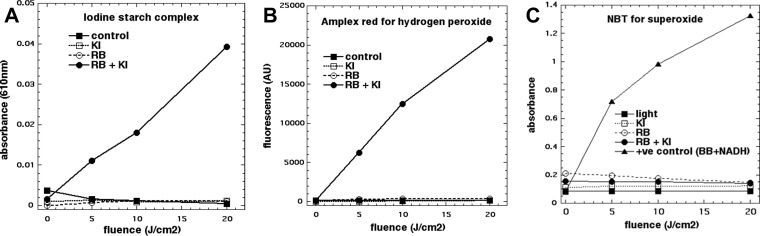

We carried out a range of experiments to elucidate the mechanism of action of the potentiation of RB-mediated aPDI by KI. Initially, we confirmed that free iodine was generated in a light dose-dependent manner by using the well-known formation of a blue inclusion complex with soluble starch (Fig. 4A). Next, we confirmed the generation of hydrogen peroxide using the Amplex red assay (Fig. 4B), as we had previously observed that H2O2 was generated by Photofrin and KI excited by blue light (19). We reasoned that there were two possible routes by which hydrogen peroxide could be formed. One involves a one-electron transfer from iodide to singlet oxygen to produce superoxide, which could then undergo dismutation to give H2O2. The other route involves addition of singlet oxygen to iodide anion to give peroxyiodide, which would decompose to give H2O2 and iodine. To distinguish between these two possible routes, we used the nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) assay for superoxide (20), reasoning that if we detected superoxide, the first route was suggested, while if we did not detect it, then the second route may take place. In order to be sure that our failure to detect superoxide was real, we needed a positive control, and this was obtained by illuminating a water-soluble fullerene with UV-A light in the presence of NADH (21, 22). Figure 4C shows that there was no detectable superoxide produced by RB plus KI and 540-nm light, while we detected superoxide from the monocationic fullerene BB4 plus NADH and 360-nm light.

FIG 4.

Mechanistic experiments. (A) Production of iodine (measured as blue starch complex) by RB + KI + green light; (B) production of hydrogen peroxide (measured by Amplex Red assay) by RB + KI + green light; (C) lack of production of superoxide (measured by nitroblue tetrazolium assay) by RB + KI + green light; fullerene + NADH + 360-nm light was used as positive (+ve) control. AU, absorbance units.

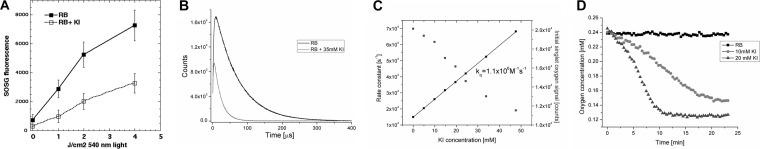

In order to confirm that singlet oxygen, as opposed to some type I ROS, was the principal mediator of the potentiated microbial killing, we asked whether KI could quench the activation of the fluorescent probe for 1O2 called “singlet oxygen sensor green” (SOSG) when RB was excited by 540-nm light. Figure 5A shows a significant quenching of SOSG activation by addition of 100 mM KI. KI quenching of the singlet oxygen photogenerated by RB was also demonstrated by direct measurement of the singlet oxygen lifetime. Figure 5B shows representative time-resolved kinetics of the formation and decay of the 1,270-nm phosphorescence detected in a control sample without KI and in the presence of 35 mM KI. At the concentration used, KI shortened the observable lifetime of the singlet oxygen-dependent luminescence more than 3-fold. It is also apparent that the initial intensity of the singlet oxygen phosphorescence was reduced in the sample containing KI. The observable lifetime of singlet oxygen and its initial intensity as a function of KI concentration are shown in Fig. 5C. The bimolecular rate constant of quenching (kq) of singlet oxygen by KI, derived from the plot, was 1.1 × 106 M−1 s−1. The chemical nature of singlet oxygen quenching by KI is clearly demonstrated by oxygen consumption measurements. Figure 5D shows that while in the absence of KI there was no measurable oxygen consumption, addition of KI induced the depletion of oxygen, with the initial rate being dependent on the KI concentration.

FIG 5.

Mechanistic experiments. (A) Activation of SOSG by RB (100 nM) excited by 540-nm light with and without added KI (100 mM); (B) time-resolved kinetics of the formation and decay of 1,270-nm phosphorescence detected in the presence and absence of 35 mM KI; (C) lifetime of singlet oxygen and its initial intensity as a function of the KI concentration; (D) oxygen consumption by illuminated RB in the presence and absence of 2 concentrations of KI.

In vivo studies.

We used a mouse model of a partial-thickness skin wound (abrasion) to test the novel combination (RB plus KI and 540-nm light) in vivo. We chose P. aeruginosa as the bacterial pathogen for the following reasons: (i) P. aeruginosa is a Gram-negative bacterial species and would not be expected to be much affected by RB plus light alone (without KI), (ii) P. aeruginosa is sufficiently pathogenic to form a long-lasting infection with a reasonable infective dose of cells, and (iii) the particular strain of P. aeruginosa that we used is not sufficiently virulent in this model to cause a systemic infection, which would lead to death of the mice.

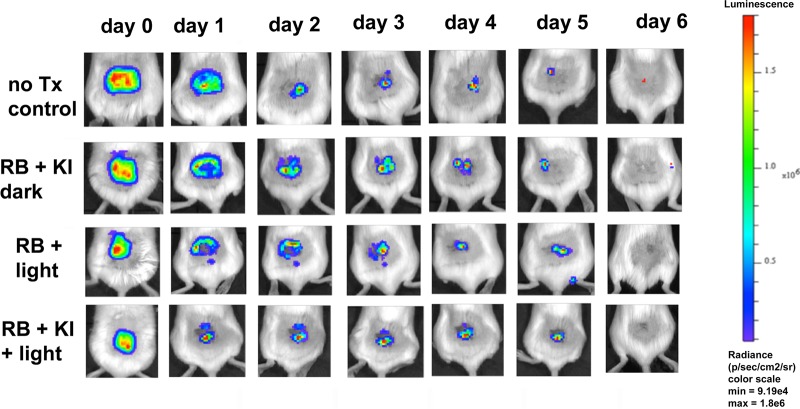

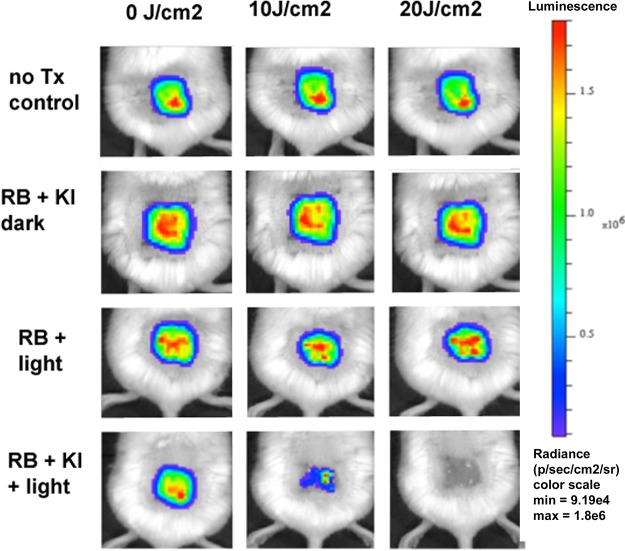

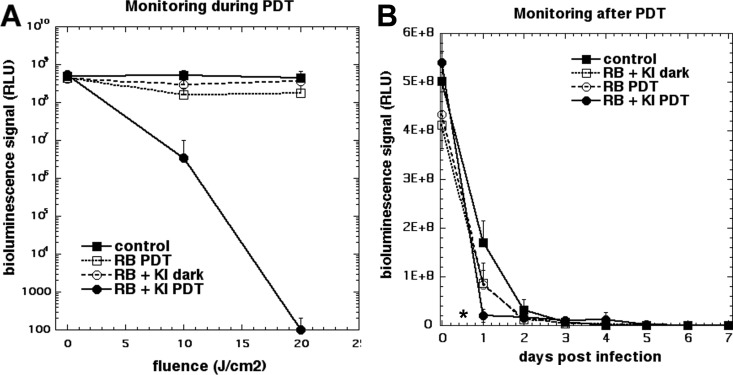

When we inoculated 5 × 105 CFU of bioluminescent P. aeruginosa (in 50 μl) into the partial-thickness abrasion wound on the back of the mice, a stable infection that lasted for longer than 6 days was established (Fig. 6). Figure 7 shows a panel of bioluminescence images from representative mice in each of the four groups captured before light (0 J/cm2) and after 10 J/cm2 and 20 J/cm2 of 540-nm light had been delivered. The no-treatment control and RB plus KI dark groups (Fig. 7, rows 1 and 2) did not show any reduction in the bioluminescence signal, while the RB plus 540-nm light groups showed only a slight reduction. In contrast, the group treated with RB plus KI and 540-nm light showed a major reduction after 10 J/cm2 was delivered, and after 20 J/cm2 was delivered, the bioluminescence signal was undetectable. Figure 8A shows the quantification of the signals from 5 mice per group. Figure 6 shows the monitoring of representative mice from four groups for six successive days after PDT. It can be seen that there is not much difference between the groups. The only noticeable observation is that the signal from the RB plus KI and light group was significantly lower than that from each of the other three groups (P < 0.05) on day 1 (i.e., the day immediately following PDT). Figure 8B shows the quantification of the bioluminescence signals. The regrowth of the luminescence signal in the wound following the apparently successful eradication by PDT has been observed before (23, 24) and is the chief drawback of using PDT as an antibacterial therapy in vivo.

FIG 6.

Monitoring of aPDT of skin abrasions infected with P. aeruginosa in the days following light delivery. Images from representative mice from the four groups for which the results are shown Fig. 5 were monitored for bioluminescence each day from day 0 (before PDT) until day 6. no Tx, no treatment.

FIG 7.

Monitoring of aPDT of skin abrasions infected with P. aeruginosa during light delivery. Representative bioluminescence images from a mouse from each of the treatment groups are shown: the no-treatment control group, the group treated with 50 μl of RB (500 μM) plus KI (1 M) in the dark, the group treated with 50 μl of RB (500 μM) plus PDT, and the group treated with 50 μl of RB (500 μM) plus KI (1 M) and PDT. Images were captured after delivery of 0, 10, or 20 J/cm2 of 540-nm light (rows 3 and 4) or after equivalent times had elapsed (rows 1 and 2).

FIG 8.

Quantification of the bioluminescence signals from the mice in the groups for which the results are shown in Fig. 5 and 7. Points are means for 5 mice, and bars are SDs. *, P < 0.05 versus the control by one-way ANOVA.

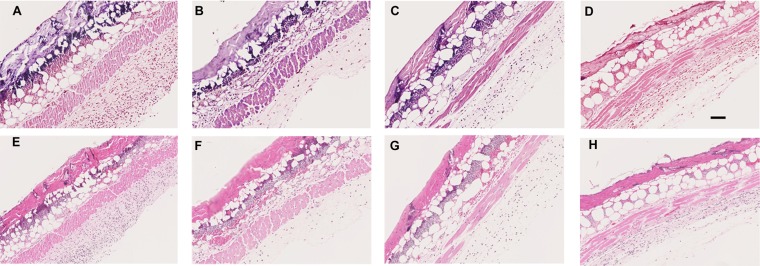

Figure 9 shows the histology images taken from mice that were sacrificed 24 h after PDT. We stained the sections with Gram stain to visualize the P. aeruginosa cells in the tissues (Fig. 9A to D) and also with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (Fig. 9E to H) to visualize any gross damage that may have been caused by the PDT or by the iodine produced by PDT plus KI. There were clearly fewer bacteria present in the group treated with PDT plus KI (Fig. 9D) than in the other groups (Fig. 9A to C). While H&E staining is not necessarily the most sensitive method to detect PDT-induced tissue damage, there were no obvious signs of extra damage in Fig. 9H compared to Fig. 9E to G.

FIG 9.

Histology images. (A and E) No-treatment control; (B and F) RB plus KI in the dark; (C and G) RB plus light; (D and H) RB plus KI and light. (A to D) Gram stain; (E to H) H&E stain. Bar, 100 μm.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that addition of the simple nontoxic inorganic salt potassium iodide can dramatically potentiate aPDI mediated by RB, especially against Gram-negative bacteria. In the case of two Gram-negative bacterial species, E. coli and the hard-to-kill species P. aeruginosa, addition of 25 mM KI gave 7 logs of killing, whereas almost no killing was obtained with RB aPDI in the absence of KI. In the case of the fungal yeast C. albicans, addition of 100 mM KI gave eradication (>6 logs of killing), whereas just over 1 log of killing was achieved without KI. The data suggest that two kinds of antimicrobial species are produced by the PDT-induced oxidation of iodide. The most obvious antimicrobial species is molecular iodine (or triiodide in the presence of iodide), as shown by the generation of the blue inclusion complex when starch was added to the reaction product obtained when 540-nm light was delivered to a mixture of RB plus KI. Nevertheless, there is clearly another short-lived antimicrobial species that is generated and can produce killing only when the cells are present during the illumination. With Gram-negative bacteria, eradication was achieved with 25 mM KI when cells were present, while 100 mM KI was necessary when the bacteria were added after light. In the case of C. albicans, eradication was achieved with 100 mM KI when cells were present, while hardly any killing was seen when cells were added after light. In the case of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (with a low concentration of RB and 100 mM KI), eradication was achieved with the cells were present and only 1 log of killing was achieved when cells were added after light. The explanation for the difference in susceptibility between Gram-negative species, on the one hand, and Gram-positive species and Candida, on the other hand, when cells were added after light probably lies in features such as the thickness of the cell wall (25). The thin cell wall typical of Gram-negative bacteria may allow iodine species to penetrate and kill them with an ease greater than that found with other microbial cells with thicker cell walls.

RB does not bind well to most classes of microbial cells. This lack of binding is shown by the fact that centrifugation of the cells after incubation with RB removes most, if not all, of the light-mediated killing. Even with the Gram-positive bacterium MRSA, against which RB is extremely active as an antimicrobial PS (since the low concentration of 200 nM produced eradication), centrifugation abolished the killing. In the case of C. albicans, binding appears to be of some importance, since there was some minor killing after centrifugation; there was also potentiation with 100 mM KI when cells were present but no killing when cells were added after light. As seen in Fig. 3, C. albicans was the only cell type to show any detectable fluorescence after incubation with RB. We assume that the reactive iodine species are more efficient in killing microbial cells when they are generated close to the cells, as might be expected with loose binding of the RB to the cell surface. If the binding between the cells and the RB was loose, it might be expected that the RB could be dislodged after centrifugation.

RB has been found to operate largely via the type II photochemical pathway involving energy (hν) transfer from the long-lived RB triplet state to the ground-state triplet oxygen to produce the reactive singlet oxygen (equations 1 and 2) (26). The number of heavy halogen atoms (4 iodine and 4 chlorine atoms) means that RB has a singlet oxygen quantum yield of about 0.86 (27). In fact, RB is often used as a standard in determinations of singlet oxygen quantum yields (28).

| (1) |

| (2) |

There two possible pathways by which singlet oxygen could, in principle, react with iodide anion. The first pathway is a one-electron transfer from iodide to 1O2 to give superoxide anion and iodide radical (equation 3).

| (3) |

The iodide radicals dimerize to give molecular iodine, which reacts with iodide to give the triiodide anion (equation 4). Iodine radicals would then be the short-lived reactive species that give potentiation of aPDI killing.

| (4) |

The superoxide anion then undergoes dismutation to give hydrogen peroxide (equation 5).

| (5) |

This pathway was our initial hypothesis, after we demonstrated the formation of both iodine/triiodide and hydrogen peroxide, which was consistent with the proposed mechanism. However, despite numerous attempts, we were unable to show any production of superoxide using the NBT assay, even though we were able to obtain a positive result with another established photochemical method to generate superoxide. This was done by illumination of a water-soluble fullerene in the presence of reduced NADH (21, 22). Hence, we concluded that a one-electron transfer reaction from iodide to singlet oxygen to give superoxide and the iodine radical probably did not occur. It must also be stressed that such a reaction is thermodynamically unlikely, for it would be accompanied by an unfavorable change in free energy. This is because the one-electron reduction potentials of the corresponding couples, 1O2/O2˙− and I˙/I−, are +0.65 V and +1.270 to 1.400 V, respectively (29).

However, there is a second possible pathway between singlet oxygen and iodide. This takes the form of an addition reaction between singlet oxygen and iodide to give peroxyiodide (equation 6).

| (6) |

The decomposition of peroxyiodide is proposed to proceed via equations 7 to 10.

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

Dalmázio et al. (30) from Brazil used mass spectrometry and ab initio free energy calculations to study the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide in the presence of iodide anions. They detected a species with m/z 287 that was proposed to be HOOI2−. Calculations revealed that the thermodynamically preferred decomposition pathway was equation 11 to produce two radicals.

| (11) |

Competing decomposition pathways were energetically less favored by between 25 and 68 kcal/mol.

These two radicals, I2˙− and HOO˙, would account for the short-lived reactive species responsible for the extra killing observed when the cells were present during the illumination.

We originally discovered that the action of KI (maximum concentration, 10 mM) potentiates the aPDI mediated by the phenothiazinium salt methylene blue (MB) (16). We had previously shown that the potentiation of aPDI mediated by MB was paradoxically potentiated by 10 mM sodium azide (singlet oxygen quencher) operating by a one-electron transfer from azide anion to excited-state MB to form azide radicals in an oxygen-independent process (31). Therefore, we assumed that the mechanism in the case of KI and MB was an analogous one-electron transfer from the iodide anion to the excited-state PS to form an iodine radical and an MB radical anion (16). We then went on to show that the photocatalysis mediated by titanium dioxide nanoparticles excited by UV-A light could also be strongly potentiated by addition of KI (18). Here the mechanism was via a mixture of a one-electron oxidation of iodide anion to form molecular iodine and a two-electron oxidation of iodide anion to form hypoiodite. It was not until we discovered (19) that aPDI mediated by the porphyrin PS known as Photofrin was also able to be strongly potentiated by KI (provided the concentration of iodide was at least 25 mM and, preferably, 100 mM) that we realized singlet oxygen was likely to be involved in the process (19, 32). We were able to show not only that activation of SOSG was quenched by KI but also that the luminescence signal of singlet oxygen was quenched by iodide and that oxygen was consumed in irradiated samples containing RB and KI. Quenching of the characteristic singlet oxygen phosphorescence by KI suggests that the effect is due to the interaction of KI with singlet oxygen, which shortens the observable lifetime of singlet oxygen, and to the interaction of KI with the RB triplet excited state, which reduces the observable intensity of singlet oxygen. While the former interaction is mostly chemical in nature, leading to the formation of the unstable peroxyiodide, the latter interaction could be a physical quenching of the RB triplet excited state with no specific product formed or a charge-coupled triplet deactivation, in which the triplet excited state of RB is reduced by KI (33). Although Denofrio et al. (34) reported on a very efficient quenching of both the singlet and triplet excited states of pteridines by KI, with the corresponding rate constants being close to the diffusion-controlled limit, the effect observed in the present study (Fig. 5A) suggests that the efficiency with which KI quenches the RB excited triplet state is significantly lower. This is probably due to the strong electrostatic repulsive interaction of the two molecules, which in water at neutral pH are negatively charged (35), and to the relatively low energy level of the RB triplet excited state that makes the charge-coupled quenching mechanism inefficient.

In the present study, we were able to show the effectiveness of KI as an enhancer of RB-mediated PDT in a mouse model of a partial-thickness wound infection caused by the stubborn and drug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial pathogen P. aeruginosa. Although MRSA is the most problematic cause of complicated skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs), P. aeruginosa comes in second in this regard (36). Moreover, P. aeruginosa displays intrinsic antibiotic resistance, has the capacity to acquire further resistance mechanisms, and readily forms a protective biofilm in vivo (37). Among several studies of aPDI, P. aeruginosa is considered to be one of the hardest bacterial species to kill by aPDI (38). The monitoring of the bioluminescence signal during light delivery did show a strong potentiation of the bactericidal effect by addition of KI, as might be expected from the in vitro data. Moreover, the monitoring of the bioluminescence signal in the days following PDT appeared to show that the addition of KI also appeared to give some benefit in inhibiting recurrence, especially on the day after PDT. It has become apparent that the main drawback to using PDT as an antibacterial intervention in models of localized infection is the fact that after the light has been turned off, the generation of antimicrobial species ceases and any remaining bacteria are completely free to regrow. However, in the present case of added KI, it is likely that free iodine/triiodide is generated within the wound by the action of photogenerated singlet oxygen on iodide anions. This free iodine/triiodide may remain active within the wound for a much longer time and may inhibit bacterial regrowth for some time to come.

We believe that the action of KI to potentiate aPDT is sufficiently impressive and that, in conjunction with its nontoxic nature, it could progress into clinical testing for those infections where aPDT is being clinically explored, such as periodontitis or chronic sinusitis (39).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and reagents.

Rose bengal (RB), potassium iodide (KI), nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT), and all other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise indicated. An Amplex red hydrogen peroxide/peroxidase assay kit was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). The singlet oxygen sensor green (SOSG) and hydroxyphenyl fluorescein (HPF) probes used to detect singlet oxygen or hydroxyl radicals were purchased from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY, USA); the starch indicator was purchased from Ricca Chemical Company (Arlington, TX, USA). RB stock solution (5 mM) was prepared in distilled H2O (dH2O) and was stored at 4°C in the dark for no more than 2 weeks prior to use. KI solution was prepared in dH2O as required immediately before experimentation.

Light source.

A green light source consisting of a white lamp with a band-pass filter probe (wavelength, 540 ± 15 nm; Lumacare, Newport Beach, CA, USA) was used to deliver light over a spot of 4 cm in diameter that covered four wells of a 24-well plate in vitro or the whole abrasion in vivo at an irradiance of 100 mW/cm2. Light power was measured with a power meter (model DMM 199 with a 201 standard head; Coherent, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Cells and culture conditions.

The following microbial strains were used: the Gram-positive bacterium methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) USA 300, Gram-negative bacteria Escherichia coli K-12 (ATCC 33780) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 19660 (Xen 5P), and strain CEC 749 of the luciferase-expressing fungal yeast Candida albicans. A colony of bacteria or fungal yeast was suspended in 20 ml of brain heart infusion (BHI) broth for bacteria or yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) for C. albicans and grown overnight in a shaker incubator (New Brunswick Scientific, Edison, NJ) at 120 rpm under aerobic conditions at 37°C for bacteria and at 30°C for C. albicans. For bacteria, an aliquot of 1 ml from an overnight bacterial suspension was refreshed in fresh BHI for 2 to 3 h at 37°C to mid-log phase. The cell concentration was estimated by measuring the optical density (OD) at 600 nm (OD of 0.6 = 108 cells/ml). The C. albicans cell number was assessed with a hemocytometer and was generally between 107 and 108 cells/ml.

In vitro studies.

Two types of in vitro aPDI experiments were done. The first used cells with a fixed RB concentration and KI concentration and varied the light dose. The second type of experiments used cells with a fixed RB concentration and a fixed light dose and varied the KI concentration. Here we compared the order of addition of the components and the effect of centrifugation. The initial studies used PDI, with suspensions of bacteria (108 cells/ml) or C. albicans (107 cells/ml) being irradiated with different fluences of green light (0, 10, and 20 J/cm2) and with different concentration of RB (100 nM for MRSA, 10 μM for E. coli and C. albicans) with or without 100 mM KI. The aliquots were serially diluted 10-fold in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to give dilutions of 10−1 to 10−5, in addition to the original concentration, and 10-μl aliquots of each of the dilutions were streaked horizontally on square BHI agar plates for bacteria or YPD agar plates for Candida. Plates were streaked in triplicate and incubated for 12 to 18 h at 37°C (bacteria) or for 24 to 36 h at 30°C (Candida) in the dark to allow colony formation. Each experiment was performed at least three times.

Suspensions of bacteria (108 cells/ml) or C. albicans (107 cells/ml) were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min with 10 μM RB (for Gram-negative bacteria and C. albicans) or 100 nM RB (for MRSA), and then KI at concentrations ranging from 0 to 100 mM in PBS (pH 7.4) was added. Centrifugation (5 min, 3,200 rpm) of 1-ml aliquots was used to remove the excess of RB that was not taken up by the microbial cells when experiments required it.

The 1-ml aliquots were transferred to a 24-well plate, and the tops of the plates were illuminated with 10 J/cm2 of green light in the dark at room temperature. Care was taken to ensure that the contents of the wells were mixed thoroughly before sampling, as bacteria can settle at the bottom. The aliquots were serially diluted as described above.

When experiments required it, 10 μM RB or 100 nM RB plus KI at concentrations ranging from 0 to 100 nM in PBS (pH 7.4) was exposed to 10-J/cm2 green light, and then bacterial or C. albicans cells were added to the illuminated mixture of RB plus KI. After 30 min of incubation, the aliquots were serially diluted as described above. Each experiment was performed at least three times.

RB (10 μM or 100 nM) and KI at a range of concentrations were exposed to 10 J/cm2 of green light, and then 108 cells/ml of bacteria or 107 cells/ml of C. albicans were added and the mixture was incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. The aliquots were serially 10-fold diluted as described above. Each experiment was performed at least three independent times.

A control group of cells treated with light alone (no RB added) showed the same number of CFU as the absolute control (data not shown). Survival fractions were routinely expressed as ratios of the number of CFU of microbial cells treated with light and RB (or RB in the absence of light) to the number of CFU of microbes treated with neither.

Confocal scanning laser microscopy.

Suspensions of E. coli or MRSA (108 cells/ml) or of C. albicans (107 cells/ml) were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min with 10 μM RB, and then 1-ml aliquots were centrifuged (3 min, 3,200 rpm) to remove the excess of RB. A confocal scanning fluorescence microscope (Olympus American Inc., Melville, NY) was employed to observe the fluorescence emission of RB and cells. Fluorescent images were obtained with a 585-nm band-pass filter. Excitation was at 543 nm.

Mechanistic experiments. (i) Iodine starch test.

RB (10 μM) and KI (100 mM) were illuminated with increasing fluences of green light, and aliquots (50 μl) were withdrawn after illumination at the different fluences and added to the starch indicator (50 μl). A microplate reader (absorbance at 610 nm) was used to measure the incremental absorbance after an incremental fluence of 415 nm of light was delivered. Controls were (i) RB plus light, (ii) KI plus light, and (iii) PBS alone. Each experiment was performed at least three times.

(ii) Amplex red assay for hydrogen peroxide.

An Amplex red hydrogen peroxide/peroxidase assay kit was used to detect the production of H2O2 from RB- and KI-mediated PDT. The colorless probe Amplex red (10-acetyl-3,7-dihydroxy-phenoxazine) reacts with H2O2 in the presence of peroxidase and forms resorufin (7-hydroxy-3H-phenoxazin-3-one). The detection process after RB- and KI-mediated PDT was done according to the manufacturer's instructions. The reaction systems contained 2 μM RB with added 50 mM KI and were illuminated with increasing fluences of green light, and aliquots were withdrawn and added to 50 μM Amplex red reagent and 0.1 U/ml horseradish peroxidase (HRP) in Krebs-Ringer phosphate (which consists of 145 mM NaCl, 5.7 mM Na3PO4, 4.86 mM KCl, 0.54 mM CaCl2, 1.22 mM MgSO4, 5.5 mM glucose, pH 7.35). After 30 min of incubation, a fluorescence microplate reader (excitation, 530 nm; emission, ∼590 nm) was used to measure the incremental fluorescence after an incremental fluence of green light was delivered. Controls were (i) RB plus light, (ii) KI plus light, and (iii) Amplex red reagent alone. Each experiment was performed at least three times.

(iii) NBT.

The superoxide assay employed NBT at 20 mM, RB at 10 μM, and KI at 50 mM, and all three were dissolved in PBS. All ingredients were freshly prepared prior to the procedure; an absorbance microplate reader was used to measure the incremental absorbance of the blue product (560 nm) after an incremental fluence of green light was delivered. Controls were (i) RB plus light, (ii) KI plus light, and (iii) PBS alone. Each experiment was performed at least three times. A monocationic fullerene, BB4 (35 μM in combination with 1 mM NADH) (21), excited by 360-nm light was used as a positive control for photogenerated superoxide production.

(iv) Activation of SOSG.

Cell-free experiments were performed in 96-well plates. RB was used at 100 nM in PBS, and SOSG (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, USA) was added to each well at a final concentration of 5.0 μM. KI solution (100 mM KI) was either added or not added. Each experimental group contained four wells. All groups were illuminated simultaneously, and light was delivered in sequential doses of 1.0 to 4 J/cm2. A microplate spectrophotometer (Spectra Max M5; Molecular Devices) was used for the acquisition of fluorescence signals in the slow kinetic mode. The fluorescence excitation was at 505 nm and emission was at 525 nm. Each time after an incremental fluence was delivered, the fluorescence was measured.

(v) Interaction of singlet oxygen with iodide.

The interaction of iodide with singlet oxygen photogenerated by RB was examined directly by measuring the lifetime of singlet oxygen at different concentrations of KI and indirectly by monitoring the effect of increasing concentrations of iodide on oxygen uptake induced by irradiation of the RB solution with green light (40).

In brief, time-resolved singlet oxygen detection was carried out as follows. Phosphate-buffered (pH 7.2) D2O solutions of RB (optical density, ∼0.25 to 0.3 at 550 nm) in a 1-cm-optical-path quartz fluorescence cuvette (catalog number QA-1000; Hellma, Mullheim, Germany) were excited by 550-nm pulses generated by an integrated nanosecond neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser system equipped with a narrow-band-width optical parametric oscillator (model NT242-1k-SH/SFG; Ekspla, Vilnius, Lithuania), which delivered pulses at a repetition rate of 1 kHz with energy of up to several hundred microjoules in the visible region. Due to the high efficiency of singlet oxygen photogeneration by RB, the energy of the exciting pulses was attenuated ∼400 times. The near-infrared luminescence (1,270 nm) was measured perpendicularly to the excitation beam in a photon-counting mode using a thermoelectric cooled near-infrared photomultiplier tube (NIR PMT) module (model H10330-45; Hamamatsu, Japan) equipped with a 1,100-nm-cutoff filter and an additional dichroic narrow-band filter narrow-band pass (NBP), selectable from the spectral range of 1,150 to 1,355 nm (NDC Infrared Engineering Ltd., Maldon, Essex, UK). Data were collected using a computer-mounted peripheral component interconnect (PCI)-board multichannel scaler (model NanoHarp 250; PicoQuant GmbH, Berlin, Germany). Data analysis, including first-order luminescence decay fitted by the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm, was performed by custom-written software. A typical acquisition time was 20 s. The effect of potassium iodide on the singlet oxygen lifetime was examined over a concentration range of from 0 to 50 mM.

(vi) Oxygen photoconsumption measurements.

Time-dependent changes in the oxygen concentration induced by light were determined by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) oximetry using 0.1 mM 4-hydro-3-carbamoyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-pyrrolin-1-oxyl ( mHCTPO) as a dissolved-oxygen-sensitive spin probe. Samples containing 25 μM RB in PBS, pH 7.2, were irradiated in EPR quartz flat cells in the resonant cavity with 516- to 586-nm (35-mW/cm2) light derived from a 300-W high-pressure compact arc xenon lamp (Cermax; model PE300CE-13FM/Module300W; PerkinElmer Opto-Electronics, GmbH, Wiesbaden, Germany) equipped with a water filter, a heat-reflecting mirror, a cutoff filter blocking light below 390 nm, and a green additive dichroic filter (catalog number 585FD62-25; Andover Corporation, Salem, NC, USA). For EPR, samples were run using microwave power of 1.06 mW, a modulation amplitude of 0.006 mT, a scan width of 0.3 mT, and a scan time of 21 s. Thirty subsequent scans were acquired every 30 s. EPR measurements were carried out using a Bruker EMX-AA EPR spectrometer (Bruker BioSpin, Rheinstetten, Germany).

In vivo studies. (i) Bacterial strain and culture conditions.

The Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain used in this work was ATCC 19660 (Xen 5P). Bacteria were routinely grown in BHI with aeration in an orbital incubator at 100 rpm and 37°C overnight to stationary phase. An aliquot of this suspension was then refreshed in fresh BHI to mid-log phase. Cell numbers were estimated by measuring the OD at 600 nm (OD of 0.6 = 108 CFU cells/ml). The bacterial suspension was centrifuged, washed, and resuspended in PBS, and the suspension was diluted 10-fold for the in vivo experiments.

(ii) Bioluminescence imaging.

An IVIS Lumina series III in vivo imaging system (PerkinElmer, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) was applied for bioluminescence imaging on a daily basis until the disappearance of the infection by bioluminescence imaging. Using the photon counting mode, an image can be obtained by detecting and integrating individual photons emitted by the bacterial cells. Prior to PDT and imaging, mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of a ketamine-xylazine cocktail. Mice were then placed on an adjustable stage in the imaging chamber positioned directly under the camera. A grayscale background image of each mouse was made, and this was followed by the collection of a bioluminescence image of the same region displayed in a false color scale ranging from red (most intense) to blue (least intense) and superimposed on the grayscale image. The signal from the bioluminescence image was quantified as the region of interest (ROI), with absolute calibrated data being given as the number of photons second−1 centimeter−2 steradian−1, using the IVIS software.

(iii) Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in mice.

All animal experiments were approved by the Subcommittee on Research Animal Care (IACUC) of the Massachusetts General Hospital and met National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines. Adult female BALB/c mice that were 6 to 8 weeks old and that weighed 18 to 21 g were used (Charles River Laboratories, MA, USA). Mice were given access to food and water ad libitum and maintained on a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle under a room temperature of 21°C. Mice were anesthetized by i.p. injection of a ketamine-xylazine cocktail. The dorsal skin of the mice was shaved with an electric razor. To create abrasion wounds, surgical scalpels were used to gently scrape the epidermis off an area of approximately 1 cm2. The depth of the wound was no more than the shallow dermis. After creating the wounds, an aliquot of a 50-μl suspension containing 5 × 105 CFU of P. aeruginosa in PBS was inoculated over each defined area containing the abrasion with a pipette tip. Bioluminescence images were taken immediately after the inoculation of bacteria to ensure that the bacterial inoculum applied to each abrasion was consistent.

(iv) In vivo PDT.

Mice were divided into four groups of 5 mice each. The sample size was determined by an 80% power to distinguish between RB PDT and RB plus KI PDT at a significance level with a P value of 0.05 with a large effect size in relative light unit (RLU) measurements. The groups were as follows. (i) The infected control group consisted of mice whose wounds were only infected with P. aeruginosa. (ii) The dark control group consisted of mice treated with RB with KI but no light. (iii) The RB PDT group consisted of mice treated with RB only but irradiated with 540-nm light. (iv) The RB plus KI PDT group consisted of mice irradiated with 540-nm light in the presence of RB and KI.

At 30 min after application of the bacteria to the abrasions, a small aliquot of RB solution (500 μM) alone or RB (500 μM) mixed with KI (1 M) solution was added to the PDT-treated wound and also to the dark controls. Initially, 50 μl of the RB solution was added to the abrasions and incubated for 10 min to bind to and penetrate the bacteria. Then, the wounds were irradiated with green light at a fluence of up to 20 J/cm2, and luminescence imaging was performed after irradiation. In this case, the mice were imaged daily to quantify the recurrence of bioluminescence until the bioluminescence disappeared or the animals were determined to be moribund and euthanized (this did not occur with the strain of P. aeruginosa used in the present study).

(v) Histological analysis.

Two mice per group were used for further histological analysis. The procedure was the same as that described above. The mice were then sacrificed at the first day (24 h) after the experiment to compare the antibacterial effects. Removed tissue samples were fixed in a solution of 10% formalin in 100% PBS for 2 to 3 days. After fixation, samples were embedded in paraffin blocks, sectioned to a 6-μm thickness, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin and also with Gram stain. Stained slides were assessed under a light microscope (Olympus BX51 microscope) to observe any inflammation or gross tissue damage.

Statistical methods.

Means were calculated and compared for statistical significance using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by U.S. NIH grants R01AI050875 and R21AI121700 (to M.R.H.). X.W. was supported by the West China Hospital of Sichuan University. X.Z. was supported by the Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU) Program of the National Science Foundation, Award number EEC-1358296. A.E.-H. was supported by the Fulbright Foundation. Research carried out at the Jagiellonian University (G.S. and T.S.) was supported in part by grants from the Poland National Science Center (2011/03/B/NZ1/00007 and 2013/08/W/NZ3/00700).

REFERENCES

- 1.O'Neill Commission. 2015. Tackling a global health crisis: initial steps. The review on antimicrobial resistance, chaired by Jim O'Neill. British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamblin MR, Hasan T. 2004. Photodynamic therapy: a new antimicrobial approach to infectious disease? Photochem Photobiol Sci 3:436–450. doi: 10.1039/b311900a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malik Z, Ladan H, Nitzan Y. 1992. Photodynamic inactivation of Gram-negative bacteria: problems and possible solutions. J Photochem Photobiol B 14:262–266. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(92)85104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Minnock A, Vernon DI, Schofield J, Griffiths J, Parish JH, Brown SB. 2000. Mechanism of uptake of a cationic water-soluble pyridinium zinc phthalocyanine across the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 44:522–527. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.3.522-527.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banks JG, Board RG, Carter J, Dodge AD. 1985. The cytotoxic and photodynamic inactivation of micro-organisms by Rose Bengal. J Appl Bacteriol 58:391–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1985.tb01478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bezman SA, Burtis PA, Izod TP, Thayer MA. 1978. Photodynamic inactivation of E. coli by Rose Bengal immobilized on polystyrene beads. Photochem Photobiol 28:325–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1978.tb07714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schafer M, Schmitz C, Facius R, Horneck G, Milow B, Funken KH, Ortner J. 2000. Systematic study of parameters influencing the action of Rose Bengal with visible light on bacterial cells: comparison between the biological effect and singlet-oxygen production. Photochem Photobiol 71:514–523. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demidova TN, Hamblin MR. 2005. Effect of cell-photosensitizer binding and cell density on microbial photoinactivation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:2329–2335. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.6.2329-2335.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costa AC, Rasteiro VM, Pereira CA, Rossoni RD, Junqueira JC, Jorge AO. 2012. The effects of Rose Bengal- and erythrosine-mediated photodynamic therapy on Candida albicans. Mycoses 55:56–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2011.02042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doughty MJ. 2013. Rose Bengal staining as an assessment of ocular surface damage and recovery in dry eye disease—a review. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 36:272–280. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ducrotoy MJ, Bardosh KL. 2017. How do you get the Rose Bengal test at the point-of-care to diagnose brucellosis in Africa? The importance of a systems approach. Acta Trop 165:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gu C, Ni T, Verter EE, Redmond RW, Kochevar IE, Yao M. 2011. Photochemical tissue bonding: a potential strategy for treating limbal stem cell deficiency. Lasers Surg Med 43:433–442. doi: 10.1002/lsm.21066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lippey J, Bousounis R, Behrenbruch C, McKay B, Spillane J, Henderson MA, Speakman D, Gyorki DE. 2016. Intralesional PV-10 for in-transit melanoma—a single-center experience. J Surg Oncol 114:380–384. doi: 10.1002/jso.24311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kashef N, Hamblin MR. Advances in antimicrobial photodynamic inactivation at the nanoscale. Nanophotonics, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freire F, Ferraresi C, Jorge AO, Hamblin MR. 2016. Photodynamic therapy of oral Candida infection in a mouse model. J Photochem Photobiol B 159:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2016.03.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vecchio D, Gupta A, Huang L, Landi G, Avci P, Rodas A, Hamblin MR. 2015. Bacterial photodynamic inactivation mediated by methylene blue and red light is enhanced by synergistic effect of potassium iodide. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:5203–5212. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00019-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maisch T, Baier J, Franz B, Maier M, Landthaler M, Szeimies RM, Baumler W. 2007. The role of singlet oxygen and oxygen concentration in photodynamic inactivation of bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:7223–7228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611328104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang YY, Choi H, Kushida Y, Bhayana B, Wang Y, Hamblin MR. 2016. Broad-spectrum antimicrobial effects of photocatalysis using titanium dioxide nanoparticles are strongly potentiated by addition of potassium iodide. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:5445–5453. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00980-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang L, Szewczyk G, Sarna T, Hamblin MR. 2017. Potassium iodide potentiates broad-spectrum antimicrobial photodynamic inactivation using Photofrin. ACS Infect Dis 3:320–328. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.7b00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nauseef WM. 2014. Detection of superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide production by cellular NADPH oxidases. Biochim Biophys Acta 1840:757–767. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mroz P, Pawlak A, Satti M, Lee H, Wharton T, Gali H, Sarna T, Hamblin MR. 2007. Functionalized fullerenes mediate photodynamic killing of cancer cells: type I versus type II photochemical mechanism. Free Radic Biol Med 43:711–719. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamakoshi Y, Umezawa N, Ryu A, Arakane K, Miyata N, Goda Y, Masumizu T, Nagano T. 2003. Active oxygen species generated from photoexcited fullerene (C60) as potential medicines: O2−˙ versus 1O2. J Am Chem Soc 125:12803–12809. doi: 10.1021/ja0355574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dai T, Tegos GP, Lu Z, Huang L, Zhiyentayev T, Franklin MJ, Baer DG, Hamblin MR. 2009. Photodynamic therapy for Acinetobacter baumannii burn infections in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:3929–3934. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00027-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dai T, Tegos GP, Zhiyentayev T, Mylonakis E, Hamblin MR. 2010. Photodynamic therapy for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection in a mouse skin abrasion model. Lasers Surg Med 42:38–44. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silhavy TJ, Kahne D, Walker S. 2010. The bacterial cell envelope. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2:a000414. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Planas O, Macia N, Agut M, Nonell S, Heyne B. 2016. Distance-dependent plasmon-enhanced singlet oxygen production and emission for bacterial inactivation. J Am Chem Soc 138:2762–2768. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b12704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Redmond RW, Gamlin JN. 1999. A compilation of singlet oxygen yields from biologically relevant molecules. Photochem Photobiol 70:391–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoebeke M, Damoiseau X. 2002. Determination of the singlet oxygen quantum yield of bacteriochlorin a: a comparative study in phosphate buffer and aqueous dispersion of dimiristoyl-l-alpha-phosphatidylcholine liposomes. Photochem Photobiol Sci 1:283–287. doi: 10.1039/b201081j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wardman P. 1989. Reduction potentials of one-electron couples involving free radicals in aqueous solution. J Phys Chem Ref Data 18:1637–1755. doi: 10.1063/1.555843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dalmázio I, Moura FCC, Araújo MH, Alves TMA, Lago RM, de Lima GF, Duarte HA, Augusti R. 2006. The iodide-catalyzed decomposition of hydrogen peroxide: mechanistic details of an old reaction as revealed by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry monitoring. J Braz Chem Soc 19:1105–1110. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang L, St Denis TG, Xuan Y, Huang YY, Tanaka M, Zadlo A, Sarna T, Hamblin MR. 2012. Paradoxical potentiation of methylene blue-mediated antimicrobial photodynamic inactivation by sodium azide: role of ambient oxygen and azide radicals. Free Radic Biol Med 53:2062–2071. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mosinger J, Mosinger B. 1995. Photodynamic sensitizers assay: rapid and sensitive iodometric measurement. Experientia 51:106–109. doi: 10.1007/BF01929349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chmyrov A, Sanden T, Widengren J. 2010. Iodide as a fluorescence quencher and promoter—mechanisms and possible implications. J Phys Chem B 114:11282–11291. doi: 10.1021/jp103837f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Denofrio MP, Ogilby PR, Thomas AH, Lorente C. 2014. Selective quenching of triplet excited states of pteridines. Photochem Photobiol Sci 13:1058–1065. doi: 10.1039/c4pp00079j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lambert C, Sarna T, Truscott TG. 1990. Rose Bengal radicals and their reactivity. J Chem Soc Faraday Trans 86:3879–3882. doi: 10.1039/ft9908603879. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guillamet CV, Kollef MH. 2016. How to stratify patients at risk for resistant bugs in skin and soft tissue infections? Curr Opin Infect Dis 29:116–123. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fothergill JL, Winstanley C, James CE. 2012. Novel therapeutic strategies to counter Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 10:219–235. doi: 10.1586/eri.11.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamblin MR, Zahra T, Contag CH, McManus AT, Hasan T. 2003. Optical monitoring and treatment of potentially lethal wound infections in vivo. J Infect Dis 187:1717–1726. doi: 10.1086/375244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kharkwal GB, Sharma SK, Huang YY, Dai T, Hamblin MR. 2011. Photodynamic therapy for infections: clinical applications. Lasers Surg Med 43:755–767. doi: 10.1002/lsm.21080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szewczyk G, Zadlo A, Sarna M, Ito S, Wakamatsu K, Sarna T. 2016. Aerobic photoreactivity of synthetic eumelanins and pheomelanins: generation of singlet oxygen and superoxide anion. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 29:669–678. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]