ABSTRACT

Biofilms pose a unique therapeutic challenge because of the antibiotic tolerance of constituent bacteria. Treatments for biofilm-based infections represent a major unmet medical need, requiring novel agents to eradicate mature biofilms. Our objective was to evaluate bacteriophage lysin CF-301 as a new agent to target Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. We used minimum biofilm-eradicating concentration (MBEC) assays on 95 S. aureus strains to obtain a 90% MBEC (MBEC90) value of ≤0.25 μg/ml for CF-301. Mature biofilms of coagulase-negative staphylococci, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Streptococcus agalactiae were also sensitive to disruption, with MBEC90 values ranging from 0.25 to 8 μg/ml. The potency of CF-301 was demonstrated against S. aureus biofilms formed on polystyrene, glass, surgical mesh, and catheters. In catheters, CF-301 removed all biofilm within 1 h and killed all released bacteria by 6 h. Mixed-species biofilms, formed by S. aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis on several surfaces, were removed by CF-301, as were S. aureus biofilms either enriched for small-colony variants (SCVs) or grown in human synovial fluid. The antibacterial activity of CF-301 was further demonstrated against S. aureus persister cells in exponential-phase and stationary-phase populations. Finally, the antibiofilm activity of CF-301 was greatly improved in combinations with the cell wall hydrolase lysostaphin when tested against a range of S. aureus strains. In all, the data show that CF-301 is highly effective at disrupting biofilms and killing biofilm bacteria, and, as such, it may be an efficient new agent for treating staphylococcal infections with a biofilm component.

KEYWORDS: biofilm, CF-301, lysin, Staphylococcus aureus

INTRODUCTION

Over 99.9% of bacteria in the biosphere grow within robust and resilient sessile communities called biofilms (1). Biofilm formation is a precisely controlled developmental process initiated by microbial aggregation on abiotic and biotic surfaces. Importantly, biofilms form in human tissues, facilitating serious chronic infections of the upper respiratory tract, intestinal tract, urinary tract, bone, heart valves, middle ear, gingiva, and skin that can lead to serious illness and death (2, 3). Indwelling medical devices, such as intravenous catheters, stents, prosthetic joints, and pacemakers, are frequent sites of biofilm formation and are increasingly associated with morbidity and mortality. In clinical medicine, 65 to 80% of bacterial infections are biofilm associated, costing the health care system billions of dollars each year (4–6).

Biofilms are densely packed microbial populations held within DNA, polysaccharide, and/or proteinaceous matrices (7). In the context of human disease, the biofilm matrix helps protect bacteria from innate and adaptive immune defenses and enables up to 1,000-fold increases in antibiotic tolerance compared to tolerance with planktonic bacteria. Biofilm microenvironments favor horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes (8) and drive the inactivation of antibiotics by virtue of high metal ion concentrations and low pH (9). Furthermore, biofilms are permeability barriers to some antibiotics (10), and biofilm communities will include subpopulations of semidormant persister bacteria (including small-colony variants [SCVs]) with phenotypic tolerance to antibiotics (11). The recalcitrance of biofilms to classical antibiotic treatment strategies (including prophylactic, early aggressive, and chronic suppressive therapies), combined with the propensity for human pathogens, such as Staphylococcus aureus, to form and persist in biofilms, has created a medical need for antibiofilm agents (12).

There are no approved treatments to specifically target biofilms and, for this reason, research into biofilm prevention, weakening, disruption, and direct killing is extensive (3, 13). Several methods are in development to prevent biofilm formation on artificial implants by coating the indwelling surfaces with antibiotics (14, 15), antimicrobial proteins (16), or chemicals (17, 18). Additional treatments to prevent and/or weaken biofilms are based on immunotherapies (19, 20) or the use of small-molecule quorum-sensing and cyclic-di-GMP (c-di-GMP) signaling system inhibitors (21, 22), antimicrobial peptides (23, 24), antibiotic cocktails (25, 26), bacteriophage (27), and matrix-degrading enzymes, like DNase I (28), dispersin B (29), α-amylase (30), and alginate lyase (31). Effective prophylactic treatments are important, since, once formed, mature biofilms are tolerant to most microbiocides and may require mechanical and/or surgical interventions for removal. It has been suggested that treatments for mature biofilms will require high-dose long-term antibiotic regimens combined with agents to weaken or disperse constituent bacteria (3).

A promising antibiofilm strategy has recently emerged, based on the use of a family of bacteriophage-encoded peptidoglycan hydrolases called lysins (32, 33). As purified proteins, lysins exhibit potent bacteriolytic activity against planktonic forms of many Gram-positive pathogens (34–36). Increasingly, antibiofilm activities have also been reported against biofilm forms formed by S. aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Streptococcus pyogenes (34, 37–43). The use of lysins to rapidly eradicate biofilms and kill constituent bacteria represents a new opportunity in the field of antibiofilm drug development.

We previously described a potent antistaphylococcal lysin, CF-301, which is in clinical development for the treatment of S. aureus bacteremia and endocarditis (43). Significantly, we demonstrated the ability of CF-301 to disrupt mature biofilms formed by the methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strain BAA-42. In the current study, we provide more detailed analyses of the in vitro and ex vivo antibiofilm activities of CF-301. The ability of CF-301 to disrupt mature biofilms was demonstrated against a wide range of methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) and MRSA isolates, as well as coagulase-negative staphylococci, S. pyogenes, and Streptococcus agalactiae. The ability of CF-301 to both eradicate biofilm biomass and kill biofilm bacteria was demonstrated on a variety of surfaces, including catheters. Activity was further demonstrated against polymicrobial biofilms, biofilms formed in human blood or synovial fluid, and both planktonic cultures and biofilms enriched for persister forms of S. aureus. Finally, we describe a potent synergistic effect between CF-301 and another cell wall hydrolase, lysostaphin. In all, this work demonstrates the effectiveness of CF-301 as an antibiofilm agent.

RESULTS

Biofilm capacity of S. aureus.

Nearly 80% (147/183) of S. aureus strains and isolates tested were classified as strong or moderate biofilm producers, with 100% producing some adherent biofilm (see Tables S1 and S2 in the supplemental material). No notable differences in the distributions of biofilm phenotypes (i.e., strong, moderate, or weak) were observed among the different MSSA and MRSA groups analyzed, from the contemporary clinical JMI isolates to the older well-characterized strains with NRS, ATCC, and HER designations (Table S2).

Disruption of mature biofilms with CF-301.

The minimum biofilm-eradicating concentration (MBEC) of CF-301 was determined using a range of staphylococci and streptococci. Tables 1 and S3 show that all 95 S. aureus strains are susceptible to CF-301 in the nanomolar range, with 90% MBEC (MBEC90) values of 0.125 and 0.25 μg/ml for MSSA and MRSA, respectively. There was no correlation between the propensity to form biofilms and high or low MBEC values (Tables S2 and S3). The 90% MBEC (MBEC90) value for coagulase-negative staphylococci, including Staphylococcus epidermidis, was 8 μg/ml, while the MBEC90 values for S. pyogenes and S. agalactiae were 0.25 and 0.5 μg/ml, respectively. These findings contrast with the complete resistance of staphylococcal and streptococcal biofilms to daptomycin (DAP) (MBEC90 values, >1,024 μg/ml; Tables 1 and S3).

TABLE 1.

Activity of CF-301 and DAP against mature biofilms

| Organism | n | Concn (μg/ml) of: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CF-301 |

DAP |

||||

| MBEC90 | Range | MBEC90 | Range | ||

| MSSA | 40 | 0.125 | 0.125 to 1 | >1,024 | 512 to >1,024 |

| MRSA | 55 | 0.25 | 0.125 to 0.5 | >1,024 | >1,024 |

| CoNSa | 46 | 8 | 0.125 to 32 | >1,024 | 256 to >1,024 |

| S. pyogenes (group A) | 27 | 0.25 | 0.03 to 1 | >1,024 | 256 to >1,024 |

| S. agalactiae (group B) | 20 | 0.5 | 0.03 to 1 | >1,024 | 512 to >1,024 |

Coagulase-negative staphylococci examined in this study include the following (number of isolates in parentheses): S. epidermidis (21), S. warneri (9), S. hominis (5), S. capitis (2), S. saprophyticus (2), S. cohnii (1), S. hyicus (1), S. lugdunensis (2), S. sciuri (2) and S. simulans (1).

Time course and titration analysis of CF-301 activity on biofilms.

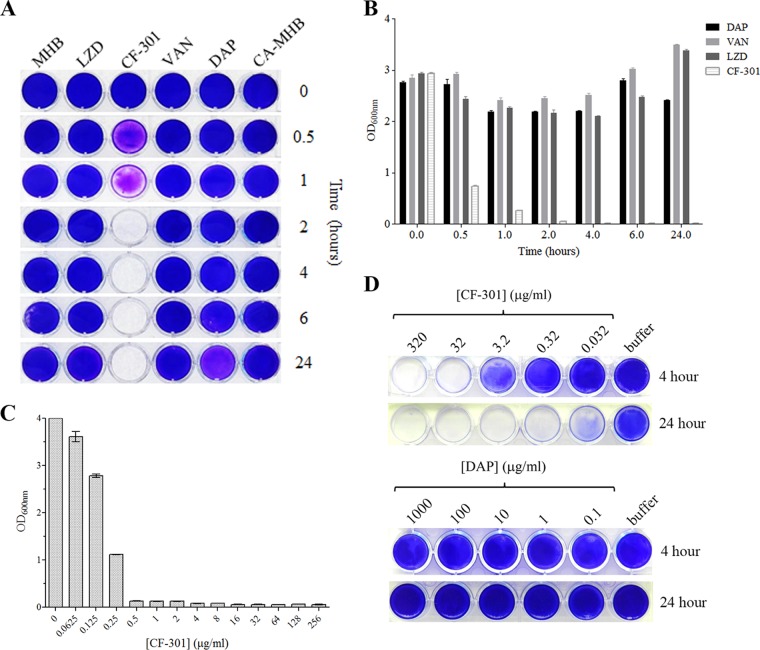

We previously demonstrated antibiofilm activity for CF-301 against S. aureus strain BAA-42 (43). This analysis was extended here to show that CF-301 (at the MIC of 32 μg/ml) can disrupt BAA-42 biofilms on 24-well polystyrene plates within 2 h and prevent regrowth over 24 h (Fig. 1A). In contrast, daptomycin, vancomycin, and linezolid treatments at 1,000× the MIC had no antibiofilm effect by 24 h. The biofilm biomass remaining after each treatment was quantitated to confirm the relative effectiveness of CF-301 over antibiotics (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

Disruption of S. aureus biofilm biomass. Biofilms of MRSA strain ATCC BAA-42 were grown over 24 h (A to C) or 2 weeks (D) in 24-well polystyrene plates and treated with either CF-301 (MIC = 32 μg/ml) or antibiotics (1,000× the MIC = 1 mg/ml) in MHB or CA-MHB. Medium-alone controls were included. (A) Crystal violet staining of biofilms treated for 24 h. (B) Quantitation of crystal violet staining over a 24-h time course. Assays were performed in triplicate, and OD600 data are the mean ± standard deviation. (C) Biofilms treated with a 2-fold dilution series of CF-301 for 4 h prior to crystal violet staining and quantitation. (D) Biofilms treated with a 10-fold dilution series of CF-301 or DAP for 4 or 24 h prior to staining with crystal violet. LZD, linezolid.

The potency of CF-301 is examined in Fig. 1C. Disruption of 1-day-old BAA-42 biofilms in 24-well polystyrene plates required as little as 0.5 μg/ml over 24 h. In a similar titration analysis of 2-week-old biofilms, all biomass was removed by 4 h using 32 μg/ml CF-301 and by 24 h using 0.32 μg/ml (Fig. 1D); here, daptomycin was ineffective over a range of concentrations.

Microscopic analysis of biofilm disruption.

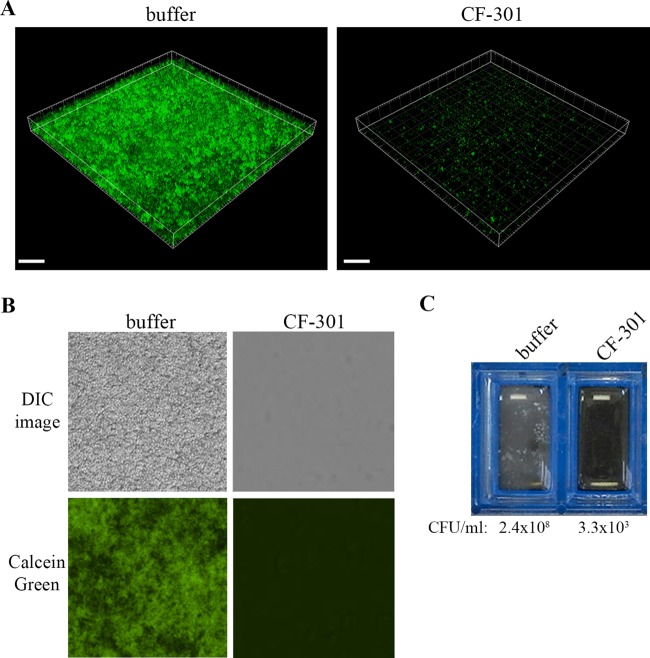

The activity of CF-301 against biofilms formed on glass slides was visualized by microscopy. In one experiment, confocal images are shown for biofilms of MSSA strain Newman (expressing green fluorescent protein [GFP]) treated for 1 h with either buffer or CF-301 at 32 μg/ml (Fig. 2A). While the buffer treatment resulted in an intact three-dimensional biofilm with a thickness of 20 to 25 μm (Fig. 2A, left), CF-301 removed most of the fluorescent signal (Fig. 2A, right). In a second experiment, differential interference contrast (DIC) images and corresponding fluorescence fields are shown for biofilms of MRSA strain BAA-42 treated for 1 h with either buffer or CF-301 at 32 μg/ml (Fig. 2B). Here, the buffer-treated biofilm was packed with bacteria and was highly fluorescent in the presence of calcein green biofilm stain (left column), while the CF-301-treated sample was devoid of bacteria and fluorescence (right column). The removal of BAA-42 biofilms by CF-301 (but not buffer) was confirmed both visually and by the ∼5-log difference found in recoverable CFU (Fig. 2C).

FIG 2.

Microscopic analysis of 24-h-old biofilms on glass surfaces. (A) Confocal analysis of GFP-expressing MSSA strain Newman (CFS-1246) treated for 1 h with buffer or CF-301 (32 μg/ml). The box size is 290 μm by 290 μm by 25 μm, and voxel dimensions are 0.284 μm by 0.284 μm by 0.420 μm (scale bars = 40.0 μm). (B) Biofilms of ATCC BAA-42 on glass chamber slides, treated for 1 h with buffer or CF-301 (32 μg/ml), and stained with FilmTracer Calcein green biofilm stain. DIC images are shown with and without fluorescence (magnification, ×400). (C) Unmagnified biofilms of MRSA strain ATCC BAA-42 on glass chamber slides, treated for 1 h with buffer or CF-301 (32 μg/ml). After treatment, biofilm CFU were determined.

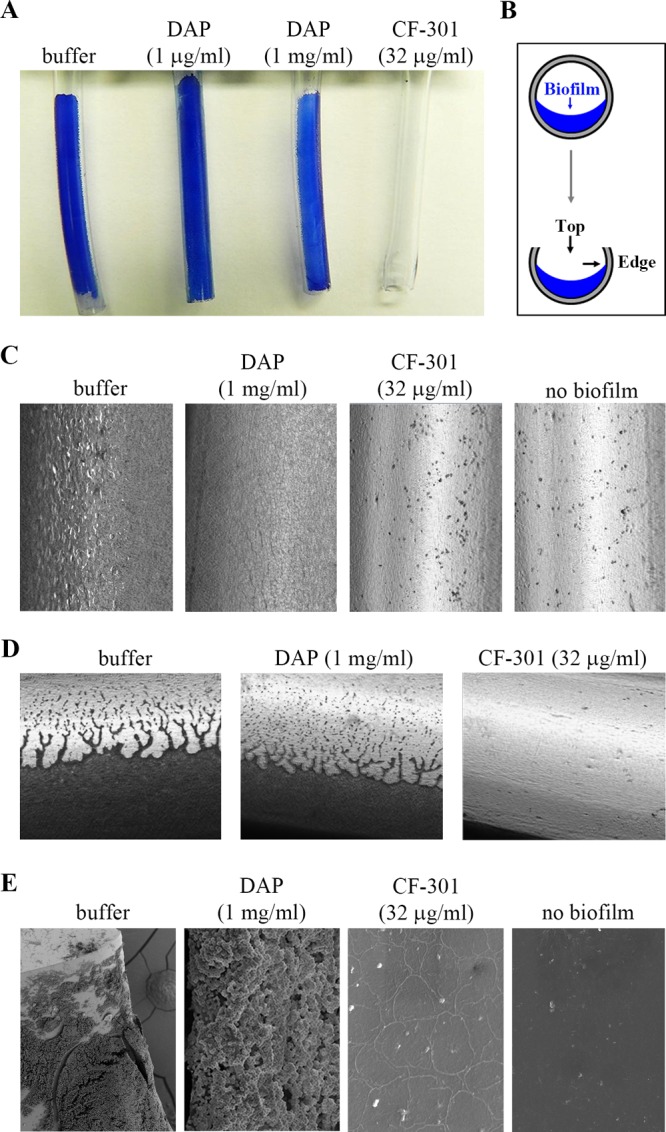

Disruption of catheter biofilms.

To examine catheter biofilms, MRSA strain BAA-42 was grown inside polyvinyl chloride (PVC) catheters for 3 days prior to treatment with CF-301 or daptomycin for 4 h. Based on staining with methylene blue, CF-301 disrupted all biofilm biomass, while daptomycin and buffer had no effect (Fig. 3A). To visualize the antibiofilm activity, the treated catheters were bisected (as indicated in Fig. 3B) and examined using bright-field microscopy and low-magnification scanning electron microscopy (SEM). “Top” views of the buffer- and daptomycin-treated biofilms show dense bacterial networks (Fig. 3C and E), while “leading-edge” views show extensions protruding from growing bacterial networks (Fig. 3D). For CF-301, regardless of the view, no biofilm biomass was detected (Fig. 3C to E). We confirmed these findings by fluorescence microscopy using buffer- and CF-301-treated catheters stained with a GFP fusion to the cell wall binding domain of CF-301 (GFP-CF-301BD). The buffer control was strongly fluorescent, while the CF-301-treated biofilm (and control lacking biofilm) produced no signal (Fig. S1).

FIG 3.

Disruption of catheter biofilms. Biofilms of MRSA strain ATCC BAA-42 were grown for 3 days in the catheter lumen (covering half of the internal diameter) before treatment for 4 h with buffer, daptomycin (DAP; 1 μg/ml and 1 mg/ml), or CF-301 (32 μg/ml). (A) Methylene blue-stained biofilm biomass remaining after treatment. (B) Representation of catheter biofilms, cut longitudinally to expose the internal biomass. Top-down and leading-edge views are indicated. (C) Top-down view of methylene blue-stained biofilm biomass. Bright-field microscopic images are shown at ×400 magnification. (D) Leading-edge view of methylene blue-stained biofilms. Darkly stained material represents the biofilm. Bright-field microscopic images are shown at ×400 magnification. (E) SEM images of catheter biofilms remaining after the indicated treatments. The following magnifications were used: buffer, ×500; DAP, ×7,500; CF-301, ×7,500; and no biofilm, ×7,500.

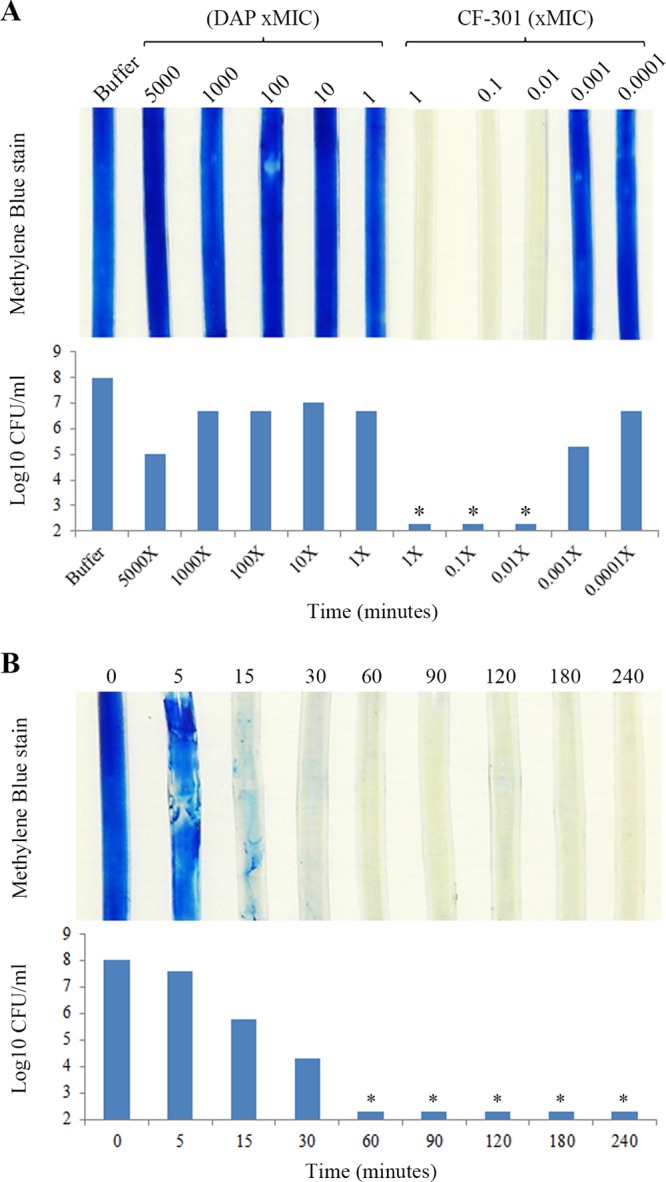

Potency of CF-301 against catheter biofilms.

A titration analysis was performed to examine the effectiveness of CF-301 against catheter biofilms formed by MRSA strain ATCC BAA-42. As shown in Fig. 4A, CF-301 concentrations ranging from the MIC (32 μg/ml) to 0.01× the MIC (0.32 μg/ml) removed all observable biofilm biomass within 4 h. The corresponding drop in biofilm bacteria was >5 log10 CFU/ml. In contrast, daptomycin had little effect on biomass from 5,000× MIC (5 mg/ml) to the MIC (1 μg/ml) and resulted in only a 1- to 3-log10 CFU/ml decrease. In an extended analysis of five additional MRSA strains, CF-301 effectively disrupted biofilms down to a concentration of 0.32 μg/ml (Table S4).

FIG 4.

Titration and time course analysis of CF-301-mediated biofilm biomass disruption and associated CFU reduction. Biofilms of MRSA strain ATCC BAA-42 were grown for 3 days in the catheter lumen before treatment. (A) Biofilms treated for 4 h with buffer, DAP, or CF-301. Drug concentrations are based on MIC values; MICs of DAP and CF-301 are 1 μg/ml and 32 μg/ml, respectively. Methylene blue-stained biofilms are shown with a matched analysis of biofilm CFU remaining after each treatment. Asterisks denote the limit of detection. (B) Biofilms treated with CF-301 (32 μg/ml) over a 4-h time course. At the indicated time points, catheters were washed and biofilms were either stained with methylene blue or quantitated to determine the CFU. Asterisks denote the limit of detection.

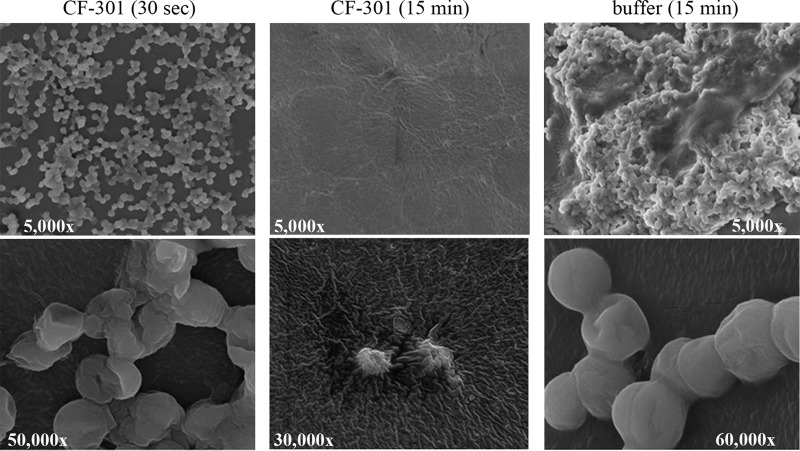

A series of time course experiments were performed to further examine the potency of CF-301 against biofilms formed by MRSA strain ATCC BAA-42. Biofilm biomass was completely removed after only 1 h with CF-301 at 32 μg/ml (Fig. 4B), and the corresponding drop in biofilm bacteria was >5 log10 CFU/ml. By SEM, the antibiofilm effects of CF-301 were obvious almost upon contact (Fig. 5). Within 30 s after the addition of CF-301 (32 μg/ml), the biofilm matrix and the majority of bacteria were lost, and the remaining bacteria appeared “deflated,” perhaps because of cytoplasmic leakage. By 15 min, only bacterial debris remained. In contrast, the buffer-treated biofilms appeared as robust bacterial networks embedded in an extracellular matrix after 15 min (Fig. 5).

FIG 5.

SEM images of catheter biofilms treated with CF-301. Biofilms of MRSA strain ATCC BAA-42 were grown for 3 days in the catheter lumen prior to either a 30-s or 15-min treatment with CF-301 (32 μg/ml). A 15-min buffer treatment was included as a control, and all magnifications are indicated.

Susceptibility of planktonic bacteria inside catheters to CF-301.

To address the possibility that CF-301 only disrupted the biofilms on catheters and did not kill the bacterial components, we followed the viability of lumenal planktonic cells after treatment with daptomycin or CF-301. Here, daptomycin resulted in a <1-log10 drop in CFU over 24 h, while CF-301 resulted in a >4-log10 drop to the threshold of detection by 6 h (and out to 24 h) (Fig. S2). These findings, taken with the results from Fig. 4B, support a sequence in which CF-301 removes all biofilm bacteria by 1 h and kills all lumenal bacteria by 6 h.

Formation and disruption of mixed-species biofilms.

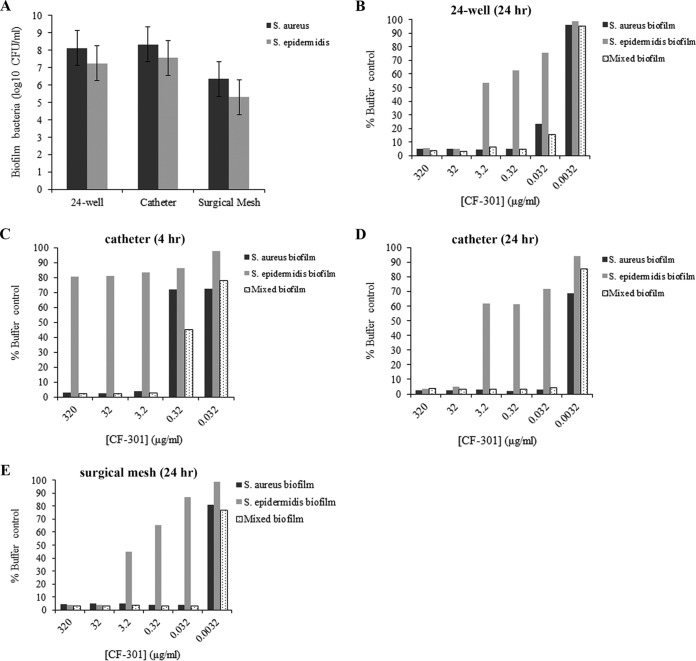

To generate stable mixed-species biofilms, an inoculum composed of S. aureus BAA-42 (CF-301 MIC and MBEC values of 32 μg/ml and 0.125 μg/ml, respectively) and S. epidermidis NRS 7 (CF-301 MIC and MBEC values of 256 μg/ml and 8 μg/ml, respectively) in a precise 2:1 ratio was coincubated for 3 days in 24-well dishes and over 6 days in catheters and surgical mesh. The resulting biofilms were consistently composed of S. aureus and S. epidermidis in ratios of ∼10:1 (Fig. 6A).

FIG 6.

Formation of mixed-species biofilms and analysis of CF-301 susceptibility. Biofilms containing S. aureus (strain BAA-42) and/or S. epidermidis (strain NRS 7) were grown either on 24-well polystyrene plates for 3 days or on catheters and surgical mesh for 6 days before treatment with a 10-fold dilution series of CF-301. (A) Quantitation of S. aureus and S. epidermidis CFU in mixed biofilms prior to CF-301 treatment. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and CFU represent the mean ± standard deviation. (B) Crystal violet staining of single- and mixed-species biofilms on 24-well plates treated for 24 h with CF-301 (relative to untreated control). (C) Catheter biofilms treated for 4 h. (D) Catheter biofilms treated for 24 h. (E) Surgical mesh biofilms treated for 24 h.

Mixed-species biofilms, formed on either 24-well plate, catheter, or surgical mesh surfaces, were susceptible to disruption by CF-301 at concentrations down to 0.032 μg/ml over 24 h (Fig. 6B, D, and E and S3B). While the susceptibility of single-species S. aureus biofilms was nearly identical to that of mixed-species biofilms, the single-species S. epidermidis biofilms alone were up to 100 times more resistant. S. epidermidis biofilms were, therefore, more sensitive to CF-301 when formed with S. aureus. This is particularly evident in 4-h treatments with CF-301 (Fig. 6C and S3A), in which S. epidermidis was resistant to 320 μg/ml as a single-species biofilm and susceptible to 3.2 μg/ml as a mixed-species biofilm.

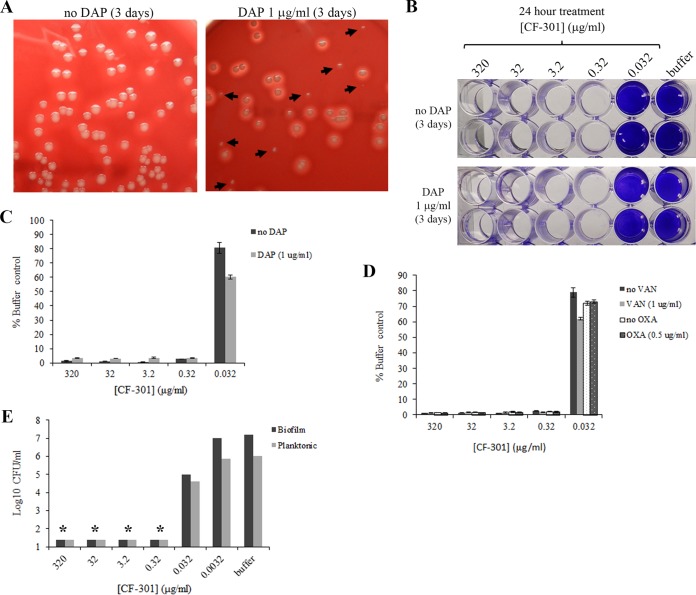

Disruption of biofilms enriched for SCVs.

To generate SCVs, biofilms of S. aureus strain BAA-42 were grown for 24 h with sublethal concentrations of antibiotics. Daptomycin, vancomycin, and oxacillin treatments selected for SCV subpopulations at rates ranging from 18.2 to 20.1% (Fig. 7A and Table S5). In contrast, biofilms grown either without antibiotics or with CF-301 yielded SCV subpopulations ranging from 0.5 to 1.7% (Table S5).

FIG 7.

Disruption of S. aureus biofilms enriched for SCVs. To select for SCVs, biofilms of MRSA strain BAA-42 were formed on 24-well plates over 3 days in the presence of daptomycin (DAP; 1 μg/ml), vancomycin (VAN; 1 μg/ml), or oxacillin (OXA; 0.5 μg/ml). (A) Appearance of SCVs among bacteria recovered from biofilms grown with and without DAP. SCVs are indicated by arrows. (B) Crystal violet staining of biofilms after growth in the presence and absence of DAP and treatment with CF-301 for 24 h. The results of duplicate experiments are shown. (C) Quantitation of crystal violet staining of biofilms grown in the presence and absence of DAP and treated with CF-301 for 24 h. Values were determined as a percentage of the buffer-treated (i.e., no CF-301) control. (D) Quantitation of crystal violet staining of biofilms grown in the presence and absence of VAN or OXA and treated with a CF-301 for 24 h. Values were determined as a percentage of the buffer-treated (i.e., no CF-301) control. (E) CF-301-mediated killing of biofilm bacteria grown in the presence and absence of DAP. After 24-h treatment with CF-301, both the biofilm and planktonic cells were quantitated. Asterisks denote the limit of detection.

Biofilms formed in either the presence or absence of daptomycin, vancomycin, and oxacillin exhibited MBEC values for CF-301 of 0.32 μg/ml (Fig. 7B to D). To confirm a bactericidal effect for CF-301, we determined CFU in both the adherent and planktonic cell fractions of biofilms grown with daptomycin and then treated with CF-301. As shown in Fig. 7E, CF-301 effectively killed both biofilm and planktonic bacteria at concentrations down to the MBEC value of 0.32 μg/ml. The SCVs were, therefore, susceptible to killing by CF-301. Biofilms formed in the presence of sublethal concentrations of CF-301 were also completely susceptible to CF-301, yielding MBEC values of 0.32 μg/ml (data not shown). No resistance to CF-301 was ever observed following treatment with CF-301.

Killing of planktonic S. aureus persister cells.

Because of the importance of persister cells to antibiotic tolerance of biofilms (11), we confirmed the effectiveness of CF-301 against planktonic persisters of S. aureus strain MW2. As shown in Fig. S4A, stationary-phase cultures were treated with 100 μg/ml daptomycin (100× the MIC) to yield a biphasic time-kill curve similar to that previously described in which the antibiotic treatment selects for highly robust persisters (11, 44). Significantly, the addition of 160 μg/ml CF-301 (5× the MIC) killed the entire persistent subpopulation within 2 h and prevented regrowth by 24 h. As shown in Fig. S4B, exponential-phase cultures were treated with 3 μg/ml ciprofloxacin (CIP) (3× the MIC) to obtain a biphasic kill curve as observed with daptomycin. Here, the addition of 160 μg/ml CF-301 killed all persisters within 1 h and prevented regrowth by 24 h.

CF-301 does not select for persister cells.

Treatments of stationary-phase and exponential-phase S. aureus cultures with CF-301 alone resulted in monophasic time-kill curves distinct from the biphasic curves observed with antibiotics (Fig. S4A and B). The CFU counts of each culture treated with CF-301 (with no antibiotic) rapidly declined to the threshold of detection by 2 h and remained undetectable to at least 24 h. Consistent with our findings that CF-301 kills persister cells, the treatment of either stationary-phase or exponential-phase S. aureus with CF-301 does not select for persistent subpopulations.

Disruption of biofilms in human serum, plasma, and whole blood.

Biofilms of MRSA strain BAA-42 were formed on catheters in the presence of either 1% human serum (HuS), 50% heat-inactivated plasma, or 50% whole blood. After formation, the biofilms were then treated with CF-301 (or buffer control) in either 100% HuS, 100% heat-inactivated plasma, or 100% whole blood, respectively, for 4 h. In each case, the CF-301 treatments (but not buffer control) resulted in complete biofilm removal and/or CFU reduction at concentrations as low as 0.32 μg/ml (Fig. S5A and B). CF-301 was, therefore, active in human blood and fractions thereof.

Stability of CF-301 in LR solution.

Antibiotic lock therapies (ALTs) for catheters often use lactated Ringer's (LR) solution as a vehicle (45). To explore the use of CF-301 as an ALT to maintain the sterility of catheters, we examined long-term stability for CF-301 in LR. At concentrations of 320 μg/ml and 3.2 mg/ml, with or without heparin, CF-301 remained 99.9% active over 3 weeks at 37°C (Table S6). At 32 μg/ml, CF-301 was 99% active after 1 day and 28.4% active by 3 weeks. Under every condition, no changes in solution clarity, color, particulate matter, turbidity, or pH were observed over 3 weeks (data not shown).

Synergistic antibiofilm activity.

Several different lysin pairs have been combined for synergistic killing of planktonic bacteria (46–48). Here, the synergy between CF-301 and the lysin-like molecule lysostaphin (49) was examined against strong and moderate biofilms formed by 10 MSSA, MRSA, vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA), and vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA) strains. Checkerboard assays were used to evaluate the synergy between CF-301 and lysostaphin. The resulting isobolograms yielded concave curves and ΣFECmin values of <0.5 (FECmin, minimum fractional eradicating concentration) (Fig. S6 and Table S7), indicating potent synergy. Combinations using as little as 1/8 the MBECs of CF-301 and lysostaphin were effective antibiofilm agents.

Ex vivo analysis of biofilms formed in HSF.

Human synovial fluid (HSF) is known to support the formation of strong antibiotic-resistant biofilms composed of host factors (including fibrin) and bacterial proteins (including fibronectin- and fibrinogen-binding proteins) (50). We showed that biofilms formed by MRSA strain BAA-42 in HSF were susceptible to removal and killing by CF-301 between 4 and 24 h (Fig. S7A). Lysostaphin alone and in combination with CF-301 also effectively killed biofilm bacteria; however, daptomycin alone had no effect. Scanning electron micrographs of buffer-treated HSF biofilms reveal a thick adherent matrix containing densely packed bacterial cells (Fig. S7B and C). After treatment with CF-301, SEM images reveal a convoluted scaffolding devoid of bacteria and interspersed with bacterial debris (Fig. S7D to F).

DISCUSSION

Antimicrobial agents for treating bacterial biofilms represent a major unmet medical need (3, 51). Aggressive antibiotic therapies can reduce biofilms and control dispersed planktonic bacteria; however, eradication is difficult because of the high antibiotic concentrations that must be sustained (50, 52–54). To avoid the limitations of antibiotics, a promising new strategy was proposed based on the emerging understanding of bacteriophage lysins as antibiofilm agents (32, 43). Lysins can potentially destroy biofilms, kill constituent bacteria, and resensitize released planktonic bacteria to antibiotics and immune surveillance, and, in doing so, provide effective standalone or adjunctive therapies to treat biofilm infections.

The potent (and rapid) antibiofilm activity of CF-301 was first demonstrated using an initial test concentration of 32 μg/ml (MIC; 1.2 μM) to eliminate biofilms formed on a range of surfaces, including polystyrene (i.e., 24- and 96-well microtiter plates), glass (i.e., chamber slides), and PVC (i.e., catheter tubing). The sensitivity of catheter biofilms was particularly notable, with surface removal of all biofilm bacteria and matrix elements within 15 to 60 min and the complete sterilization of the intralumenal environment by 6 h (Fig. 4 and S2). The efficient removal and killing of biofilm bacteria by CF-301 are particularly ideal features for catheter lock solutions. Catheter lock solutions are often composed of heparin and high concentrations of antibiotics (in LR solution) for instillation into the catheter lumen to sterilize, treat catheter-related bacteremia, minimize complications, and avoid catheter removal (55). In support of such a use, we demonstrated potent CF-301 activity in LR solution, with and without heparin, over a 3-week period at 37°C (Table S7).

To extend our understanding of CF-301 as an antibiofilm agent and its potential as a therapeutic tool, a larger-scale study of the breadth and potency of CF-301 activity was also undertaken. Toward this end, the MBEC assay was used to show the effectiveness of very low (submicrogram) concentrations of CF-301 in disrupting biofilms formed by a range of 95 clinical and laboratory S. aureus strains (with MBEC90 values of 0.125 and 0.25 μg/ml against MSSA and MRSA, respectively) (Table 1). In addition to the MBEC assay, we further demonstrated potent (and rapid) antibiofilm activity for CF-301 at concentrations as low as 0.32 and 0.032 μg/ml against biofilms formed on 24-well plates (Fig. 1), catheters (Fig. 4), and silicone elastomer mesh surfaces (Fig. 6). These findings suggest that the 32 μg/ml concentration of CF-301 used in initial activity studies was in vast excess of that needed to effectively remove biofilms. The potency of CF-301 may reflect an antibiofilm mechanism involving both bacteriolysis within the biofilm and cleavage of peptidoglycan in the structural framework.

The effectiveness of CF-301 was further evaluated against S. aureus biofilms formed in association with S. epidermidis. Multiple studies describe both cooperative and antagonistic behaviors for S. aureus and other pathogens, including S. epidermidis, in the formation of monospecies and mixed-species biofilms (56). While S. epidermidis deploys strategies to inhibit biofilm formation by S. aureus, mixed biofilms do occur clinically, with serious consequences (55, 57). In the current report, we examined the sensitivities of mixed biofilms containing S. aureus and S. epidermidis on polystyrene, PVC catheters, and surgical mesh. Both the mixed-species biofilms and S. aureus monospecies biofilms were highly sensitive to removal with CF-301 at concentrations down to 0.032 μg/ml (Fig. 6). These findings show that single- and mixed-species biofilms formed by the two most common pathogens that cause medical device colonizations (and subsequent bacteremia) (58) can be disrupted by CF-301.

A hallmark of S. aureus pathogenesis is chronic persistence despite intense antibiotic therapy (59). This is attributed not only to biofilms but also to SCVs and persister cells that exist as subpopulations of non- or slow-growing staphylococci, composed of phenotypic and genotypic variants that are tolerant of antibiotics (11, 59, 60). An increased understanding of such antibiotic-tolerant variants in chronic disease has, in turn, led to an understanding of the need for new bactericidal agents to target them (3). In the current study, CF-301 activity was examined against both SCVs and persister cells. First, biofilms were grown in either the presence of daptomycin (DAP), vancomycin (VAN), or oxacillin (OXA) (to enrich for SCVs) or the absence of antibiotics and demonstrated to be equivalently sensitive to CF-301 down to 0.32 μg/ml (Fig. 7). Second, persister subpopulations of both stationary- and exponential-phase cultures (selected for by exposure to high concentrations of DAP and ciprofloxacin [CIP], respectively) were completely eliminated by CF-301. Under every condition tested, persister-enriched populations were killed by CF-301. Importantly, CF-301 alone did not select for persistent subpopulations or SCVs, nor did it select for biofilms resistant to the antibiofilm activity of CF-301 (Table S5 and Fig. S4).

Our proof-of-concept studies suggest the importance of testing CF-301 in animal models of biofilm-based disease (i.e., infective endocarditis and osteomyelitis). We do expect in vivo biofilms to pose a significant challenge, however, as biofilms formed in host tissues will include matrix proteins, like fibrinogen and fibronectin, that may block CF-301 (61, 62). Physical access to in vivo biofilms may also be limited, in particular for heart valves, deep-seated bone or joint infections, and dense fibrin-platelet thrombi in subcutaneous tissue, fascia, or muscle.

A series of ex vivo studies were performed to examine the potential for CF-301 against in vivo biofilms. In the first study, MRSA biofilms were formed in either 1% human serum, 50% heat-inactivated plasma, or 50% whole human blood before treatment with CF-301 in 100% serum, 100% plasma, or 100% blood, respectively. In each case, CF-301 effectively disrupted the biofilm biomass and killed all biofilm and planktonic CFU at concentrations down to 0.32 μg/ml (Fig. S5). Neither the electrolytes and proteins found in serum nor the host matrix proteins found in heat-inactivated plasma or heparinized whole blood (and possibly incorporated into biofilms) could inhibit CF-301 activity. The structural framework of S. aureus biofilms formed in vitro in the presence of heat-inactivated plasma has, in particular, been shown to incorporate high levels of host fibrin (63). These findings suggest that biofilm-based infections exposed to the bloodstream, like infective endocarditis, may be susceptible to CF-301.

In a second set of ex vivo studies, the antibiofilm effect of CF-301 was tested in human synovial fluid to understand the potential for treating joint infections (i.e., septic arthritis). Upon introduction into synovial fluid, S. aureus is known to rapidly form biofilms composed of large adherent aggregates enriched with fibrin and resistant to antibiotics (50, 61). In our study, staphylococcal biofilms formed readily in synovial fluid and were highly susceptible to killing by CF-301 (Fig. S7). After CF-301 treatment, large structural frameworks devoid of bacterial cells were still observed. It is likely that the remaining frameworks were predominantly composed of host-derived matrix proteins, since similar treatments of biofilms formed in tryptic soy broth with glucose (TSBg) yielded no remaining matrix after treatment with CF-301 (Fig. 5). Together, these findings show CF-301 is potent in synovial fluid against biofilms containing host-derived matrix molecules.

In addition to demonstrating the potent antibiofilm activity of CF-301 alone, we also showed the potential for synergy with a second cell wall hydrolase, lysostaphin, to further enhance activity. This finding has important practical implications, as we can envision combinations of lysins providing enhanced treatment options. Additional studies to assess synergistic antibiofilm activities between CF-301 and antibiotics are planned.

In conclusion, we provide evidence that CF-301 is a potent antistaphylococcal biofilm agent. Our findings support a potential role for CF-301 in treating both catheter-based and joint infections and strongly suggest the importance of examining efficacy in animal models for biofilm-based infections, like infective endocarditis, osteomyelitis, and pneumonia (64). We currently envision the antibiofilm activity of CF-301 as a complement to antibiotic therapy in treating biofilm-based infections. With CF-301 acting to degrade and disperse staphylococcal biofilms and antibiotics (and CF-301) to kill the released planktonic forms and prevent metastasis, this novel treatment paradigm could provide the first efficacious antibiofilm therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, antibiotics, and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains were stored at −80°C. The strains used in this study include S. aureus ATCC BAA-42 (American Type Culture Collection [ATCC], Manassas, VA), S. aureus Newman (65), S. aureus MW2 (NRS 123; BEI Resources), S. aureus CFS-1246 (Newman/GFP plasmid pCN57 [66] derived from NRS 623 [BEI Resources]), S. aureus VRS3a (NR-46412; BEI Resources), and S. epidermidis NRS 7 (BEI Resources). Other strains and isolates are described in Tables S2 and S3. The BAA-42 strain was chosen as a model strain in this study based on its strong propensity to form biofilms (43); it is a pediatric MRSA clone isolated in 1996 from a pneumology ward in Lisbon, Portugal (67).

Bacteria were cultivated on BBL Trypticase soy agar (TSA) with 5% sheep blood (Becton, Dickinson & Company [BD]), Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB; BD), MHB with 25 μg/ml CaCl2 (CA-MHB), lysogeny broth (LB; Sigma-Aldrich), and tryptic soy broth (TSB; BD) with 0.2% glucose (TSBg). The following antibiotics (Sigma-Aldrich) were used: vancomycin hydrochloride, daptomycin, linezolid, oxacillin sodium salt, ampicillin sodium salt, carbenicillin disodium salt, ciprofloxacin, and erythromycin. Lysostaphin from Staphylococcus simulans was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

Biofilm survey.

Biofilms were examined using a quantitative spectrophotometric microtiter plate assay (68). Colonies from TSA plates were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Sigma-Aldrich) to 0.5 McFarland units (∼1 × 108 CFU/ml) and diluted 1:150 in TSBg. Next, 0.15-ml aliquots were added to 96-well flat-bottom polystyrene microplates (BD Falcon; Corning Life Sciences) and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Plates were washed with PBS, and the biofilm biomass was stained for 15 min with 0.05% crystal violet (Harleco; EMD Millipore Chemicals). For quantitation, crystal violet was solubilized in 0.2 ml of 33% (vol/vol) acetic acid, and the optical density of 600 nm (OD600) was determined using a SpectraMax M3 multimode microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Inc.). Samples were examined in triplicate, and TSBg alone was used as the negative control. The OD600 values of TSBg alone were subtracted from the average OD600 of each strain. Biofilms were classified as strong, moderate, or weak according to the guidelines of Stepanović et al. (68).

MBEC assay.

The MBEC of CF-301 was determined using a broth microdilution (BMD) method, described by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (69), with modifications. For S. aureus, 95 strong, moderate, and weak biofilm-forming strains were chosen from those shown in Table S2. Bacteria were suspended in PBS (0.5 McFarland units), diluted 1:100 in TSBg, added as 0.15-ml aliquots to 96-well flat-bottom polystyrene microplates, and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Biofilms were washed and treated with a 2-fold dilution series of CF-301 or daptomycin in TSBg (containing calcium for daptomycin) at 37°C for 24 h. All samples were examined in triplicate. After treatment, wells were washed, air-dried at 37°C, and stained with 0.05% crystal violet for 10 min. The loss of biofilm biomass was assessed visually, and crystal violet was quantitated as described above. The MBEC of each sample was the minimum drug concentration required to remove >95% of the biofilm biomass assessed by crystal violet quantitation.

MIC assay.

CF-301 MICs were determined in MHB, as described previously (43), with the exception that dl-dithiothreitol was not used. Daptomycin MICs were determined in CA-MHB, as described previously (69).

Biofilm disruption in 24-well plates.

The disruption assay was performed as described previously (70). Wells of a 24-well flat-bottom polystyrene tissue culture plate (Corning Life Sciences) were inoculated with ∼1 × 106 CFU of S. aureus strain BAA-42 in 2 ml of TSBg and incubated at 37°C for either 24 h or 2 weeks with agitation at 50 rpm. For the 2-week growth, medium was aspirated every 3 days and replaced with fresh TSBg. Biofilms were washed with PBS and treated with CF-301 or antibiotic for up to 24 h. CF-301, vancomycin, and linezolid were used in MHB, while daptomycin was used in CA-MHB. Medium-alone controls were included. After treatment, wells were washed, stained for 10 min with 0.05% crystal violet, washed again, and photographed. The spectrophotometric measure of crystal violet staining (see above) was used to compare CF-301 treatments with buffer treatments according to the following equation: (absorbance value for CF-301 treatment/absorbance value for buffer control) × 100.

Confocal microscopy.

An overnight culture of S. aureus strain Newman/pCN57(GFP+) was diluted 1:1,000 into 3 ml of TSBg with 10 μg/ml erythromycin, in a 35-mm-diameter glass-bottom microwell dish (MatTek, Ashland, MA). Dishes were incubated without agitation for 24 h at 37°C, washed, and treated with CF-301 (32 μg/ml) or PBS for 1 h at 37°C. After treatment, samples were fixed in 2.6% paraformaldehyde, washed, and visualized using an inverted TCS SP8 laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica) using a HC PL APO CS2 40×/1.1 water immersion objective. A white light laser (WLL) was used at a wavelength of 489 nm, and an HyD detector was used at a range of 500 to 600 nm. Images were captured using the LAS AF 3.3 software (Leica) and analyzed using Imaris x64 7.7.2 (Bitplane).

Biofilm disruption on glass chamber slides.

Colonies of S. aureus strain BAA-42 from TSA plates were suspended in PBS (0.5 McFarland units), diluted 1:100 in TSBg, and added as 1.0-ml aliquots to 4-chambered Nunc Lab-Tek II CC2 chamber slides (Thermo Scientific). The chambers were incubated for 24 h at 37°C without agitation and washed and suspended in 1 ml of TSBg with or without CF-301 (32 μg/ml) for 1 h at 37°C. Biofilms were washed, suspended in PBS, and photographed. For microscopy, biofilms were stained with FilmTracer biofilm stain (Life Technologies Corporation), washed, mounted in ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Life Technologies Corporation), and examined by differential interference contrast (DIC) imaging and fluorescence microscopy (magnification, ×400) using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope. Images were captured using a QImaging QIClick digital charge-coupled-device (CCD) camera (QImaging, Inc.) and processed using the NIS-Elements imaging software (version 4.0). The excitation and emission maxima were 494 and 514 nm, respectively. For enumeration, biofilm bacteria and planktonic cells were recovered, diluted in an equivalent volume of 25 mg/ml activated charcoal (Sigma-Aldrich), and plated in quadrants of TSA plates. Activated charcoal is often used for in vitro studies to bind and inactivate residual antibiotic and prevent a “carryover” effect (71). All samples for CFU determinations in the current study were first diluted in charcoal. The removal of biofilm bacteria (prior to plating) was performed by sonication for 1 min using a Branson 3510 ultrasonic cleaner at 40 kHz (72), followed by gentle pipetting. Biofilm removal was confirmed by crystal violet staining, as described above. The disruption of biofilm particles in suspension, to enable accurate CFU measurements, was confirmed by bright-field microscopy using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope (magnification, ×2,000).

Biofilm disruption in catheters.

Biofilms were formed in sterile 5-cm segments of SmartSite infusion set tubing (Alaris SE Pump Signature Edition infusion system; CareFusion Corporation) with a 1-mm internal diameter. The tubing is polyvinyl chloride (PVC) with diethyl hexyl phthalate (DEHP) as a softening agent. Segments were inoculated with 0.2 ml of TSBg containing 1 × 106 CFU/ml S. aureus BAA-42, the ends were sealed, and the tubes was incubated for 3 days at 37°C without agitation. The resulting biofilms were washed and treated for 4 h at 37°C with CF-301 (32 μg/ml) or daptomycin (1 μg/ml or 1 mg/ml) in 0.225 ml of lactated Ringer's (LR) solution (VWR International). The LR was the buffer control, and experiments were performed in triplicate. Under each condition, one set of catheters was drained, washed, air-dried, stained with methylene blue (0.05% [wt]; Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min, washed, air-dried, and photographed. A second set of catheters was used to quantitate biofilm bacteria using the BacTiter-Glo assay described below. A third set of catheters was used for microscopy.

Biofilms of strain BAA-42 were also formed on the surface of prebisected 1.25-cm catheter segments suspended in 2 ml of TSBg with either 1% human serum (pooled normal human type AB serum; Sigma-Aldrich), 50% human heat-inactivated plasma (Sigma-Aldrich), or 50% heparinized human whole blood (BioreclamationIVT). Higher concentrations of blood, serum, or plasma did not support biofilm formation. After 3 days at 37°C without agitation, catheter segments were then washed and treated for 4 h with a dilution series of CF-301 suspended in 2 ml of either 100% serum, 100% plasma, or 100% whole blood (depending on the condition under which the biofilms were formed). Treatments lacking CF-301 were used as controls. Under each condition, one set of catheters was stained with methylene blue (as described above) and photographed, while a second set was used to quantitate biomass and a third set was used to quantitate bacteria.

Indirect quantitation of catheter biofilm bacteria.

Bacterial CFU were estimated using the BacTiter-Glo microbial cell viability assay kit (Promega). The BacTiter-Glo assay provides a reliable and reproducible method for determining total cell numbers in S. aureus biofilms (73). Briefly, treated catheters were washed and loaded with lysis solution (lactated Ringer's solution with 100 μg/ml lysostaphin) for 8 min at 24°C. The intralumenal contents were then recovered, vortexed, and mixed with an equal volume of BacTiter-Glo in solution. The resulting glow-type luminescent signal is proportional to the amount of ATP present, which is directly proportional to the number of cells in culture (based on a standard curve generated as described above using the BacTiter-Glo kit). The samples were examined in triplicate.

Microscopic analysis of catheter biofilms.

Methylene blue-stained segments were bisected longitudinally using surgical scalpels and visualized using a Nikon Eclipse Ti-S inverted microscope (magnification, ×400). Images were captured using a QImaging QIClick digital CCD camera (QImaging, Inc.) and processed using the NIS-Elements imaging software (version 4.0). For scanning electron microscopy (SEM), bisected segments were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 0.075 M sodium cacodylate (pH 7.4) overnight at 4°C, rinsed with Milli-Q water, plunged into liquid nitrogen [N2(l)], transferred into a Leica EM AFS2 chamber filled with nitrogen gas [N2(g)], adjusted to room temperature over ∼20 h before being sputter coated with gold/palladium using a Denton Vacuum Desk IV, and analyzed with a Zeiss Leo 1550 scanning electron microscope.

Construction and analysis of GFP-CF-301BD.

A 1,116-bp DNA fragment was synthesized at Genewiz (South Plainfield, NJ), encoding an N-terminal poly-histidine tag, a central GFP domain (GFPmut2; GenBank accession no. AAG39983.1), and a C-terminal 126-amino-acid fragment of CF-301 encoding the SH3b cell wall binding domain (positions 287 to 665 in the sequence with GenBank accession no. KC348602.1). The GFP-CF-301BD construct was cloned into the EcoRI-HindIII sites of vector pBAD24 (74); expression was induced with arabinose, and protein was prepared as previously described (75). For binding studies, catheters were bisected and suspended in PBS containing 10 μg/ml GFP-CF-301BD for 30 min at 24°C. Segments were washed, air-dried, and visualized by bright-field and fluorescence microscopy using a Nikon Eclipse Ti-S inverted microscope (magnification, ×400).

Quantitation of planktonic bacteria in treated catheters.

Catheters were drained at the indicated time points, and the contents were diluted in activated charcoal, vortexed, serially diluted, and plated for viability on TSA plates for 16 h at 37°C.

Biofilm disruption on surgical mesh.

Under each condition, 4-mm2 segments of sterile surgical mesh (1-mm-thick silicone elastomer; Goodfellow Cambridge Ltd.) were suspended in 2 ml of TSBg (containing ∼1 × 106 CFU of S. aureus BAA-42) in 24-well polystyrene tissue culture plates (Corning Life Sciences). After 3 days at 37°C, the medium was aspirated and replaced with fresh TSBg for 3 additional days. Treatments consisted of PBS alone and PBS with CF-301 (32 μg/ml) for 24 h at 37°C. Biofilm bacteria were recovered by scraping and vortexing, and CFU were determined by plating serial dilutions on TSA plates. A spectrophotometric measure of crystal violet staining of mesh biofilms was used as described above.

Mixed biofilms.

Colonies of S. aureus strain BAA-42 and S. epidermidis strain NRS 7 were separately suspended in PBS (each at 0.5 McFarland units) and then diluted 1:100 and 1:50, respectively, into one TSBg aliquot. A precise 2:1 ratio of S. aureus to S. epidermidis was previously established, in preliminary experiments, to be absolutely required for the formation of stable polymicrobial biofilms; other ratios did not support the formation of polymicrobial biofilms. A final mixture of S. aureus to S. epidermidis in a 2:1 ratio served as the inoculum to generate biofilms on different surfaces as indicated: for 24-well plates, the mixture was aspirated after 2 days and replaced with fresh TSBg for 1 day, and for catheter and surgical mesh samples, the mixture was aspirated after 3 days and replaced with fresh TSBg for 3 days. Biofilms were washed and treated with CF-301 at 37°C for 4 or 24 h. Samples were examined in triplicate. Single-species biofilms were included as controls. To determine the CFU by quantitative plating, biofilm bacteria on 24-well plates, catheters, and surgical mesh were recovered in PBS, as described above, by sonication using a Branson 3510 ultrasonic cleaner at 40 kHz, followed by gentle pipetting. Biofilm removal was confirmed by crystal violet staining, and the disruption of biofilm material in suspension (to enable proper CFU determinations) was confirmed by microscopy. The distinct colony phenotypes of BAA-42 (golden yellow, hemolytic, and ∼2 mm in diameter) and NRS 7 (white, nonhemolytic, and ∼1 mm in diameter) enabled differential quantitation. A spectrophotometric measure of crystal violet staining of mesh biofilms was also used as described above.

SCV biofilms.

Biofilms enriched for S. aureus SCVs were formed in 24-well polystyrene tissue culture plates (Corning Life Sciences) by inoculating 1 × 106 CFU of the biofilm-forming strain BAA-42 into 2 ml of TSBg with daptomycin (1.0 μg/ml), vancomycin (1.0 μg/ml), or oxacillin (0.5 μg/ml). CF-301 was used at 0.1 and 0.05 μg/ml, as higher concentrations prevented biofilm formation. For daptomycin, the medium was supplemented with CaCl2 to 50 μg/ml. For oxacillin, the medium was supplemented with 4% NaCl. After 3 days at 37°C, biofilms were washed and treated with CF-301 for 24 h at 37°C. A spectrophotometric measure of crystal violet staining was used as described above.

For examination of the SCV phenotype of biofilm bacteria prior to CF-301 treatment, biofilm biomass was first recovered in the manner described above by sonication using a Branson 3510 ultrasonic cleaner at 40 kHz, followed by gentle pipetting. As described above, biofilm removal was confirmed by crystal violet staining of the 24-well plates, and the disruption of biofilm material in suspension (to enable proper CFU determinations) was confirmed by microscopy. The recovered material was then suspended in PBS containing 25 mg/ml activated charcoal, and dilutions thereof were plated on TSA for 24 h at 37°C. Colonies were enumerated and photographed. The SCVs were nonhemolytic, white, and <0.5 mm in diameter, while the wild-type (or “normal”) colonies were hemolytic, yellow, and ∼2 mm in diameter. To examine SCV stability, sets of up to 20 SCV colonies from each treatment were subcultured twice on 5% sheep blood agar in the absence of antibiotics.

Time-kill studies of persister cells treated with antibiotics and CF-301.

The susceptibility of S. aureus persister cells to CF-301 in both stationary- and exponential-phase cultures was examined in a manner similar to that described previously (11). As biofilms were not required, the laboratory MRSA strain MW2 was used. For the analysis of stationary-phase cultures, CaCl2 (50 μg/ml) and daptomycin (100 μg/ml, or 100× the MIC) were added to overnight cultures and incubated at 37°C with agitation for 5 h. CF-301 was then added (to 160 μg/ml, or 5× the MIC) for an additional 19 h. Prior to adding daptomycin (T = 0 h), and at 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, and 24 h thereafter, culture aliquots were removed, washed in 1% NaCl, resuspended in 1% NaCl containing 25 mg/ml activated charcoal, and quantitatively plated on TSA. Colonies were enumerated after incubation for up to 48 h at 37°C. Experiments were conducted in triplicate. For the analysis of exponential-phase bacteria, overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 in MHB and grown at 37°C with agitation to OD600 of 0.5 before adding ciprofloxacin (3 μg/ml, or 3× the MIC). After 4 h of growth with ciprofloxacin, CF-301 was added (160 μg/ml, or 5× the MIC) for 20 additional hours. Bacteria were quantitatively plated as described above. For each experiment, control cultures were included, to which either no drugs were added (i.e., no antibiotic and no CF-301) or CF-301 was added as the 5-h pretreatment with no antibiotic.

CF-301 stability in LR solution.

A method was used similar to that described previously (45). For the 1-, 7-, 14-, and 21-day time points, three 1-ml aliquots of CF-301 (containing either 32, 320, or 3,200 μg/ml in LR) were prepared in triplicate with and without heparin sodium salt (100 U/ml; Sigma-Aldrich). Experiments were performed at 37°C, and at each time point, a fresh inoculum of MRSA strain MW2 (0.5 McFarland standard) was diluted 1:100 into each concentration of CF-301 (with and without heparin, in triplicate) and incubated for 4 h at 37°C. The CF-301 was inactivated with 50 μg/ml proteinase K (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min at 24°C, and serial dilutions were plated on TSA for enumeration. A dilution series of each bacterial inoculum was plated for viability to determine the percentage of initial activity.

Synergy.

Checkerboards were constructed in a manner similar to that described previously (76). Appropriate dilutions of CF 301 and lysostaphin were combined into 96-well plates containing 1-day-old S. aureus biofilms prepared as described above. After 4 h at 37°C, wells were washed and stained with a 0.05% crystal violet solution. The removal of biofilm biomass was assessed visually and by spectrophotometric analysis at the OD600 of crystal violet destained in 33% acetic acid. The minimum eradication concentration (MEC) for each drug in combination was determined. The sum of the fractional eradicating concentrations (FECs, which are the equivalents of fractional inhibitory concentrations [FICs], with the standard broth microdilution method) was calculated. Synergy exists if the sum of the two FECs (ΣFEC = FECCF-301 + FECLYSOSTAPHIN) is ≤0.5 (77).

Biofilms in HSF.

Biofilms were formed over 24 h at 37°C on 0.3-cm segments of SmartSite infusion PVC tubing suspended in 0.25 ml of HSF (BioreclamationIVT) with 1 × 106 CFU/ml of S. aureus BAA-42. The resulting biofilms were transferred to 0.25 ml of HSF containing either CF-301 (32 μg/ml), daptomycin (1 μg/ml), lysostaphin (1 μg/ml), CF-301 and lysostaphin (4 μg/ml and 0.125 μg/ml, respectively), or buffer control and incubated at 37°C for 4 or 24 h. Samples were vortexed to dislodge adherent bacteria and plated to determine CFU. To confirm biofilm removal, the tubing was stained with methylene blue and examined by phase-contrast microscopy. For SEM analyses, biofilms were formed and treated in HSF with CF-301, as described above.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge David B. Huang and Vincent A. Fischetti for helpful discussions; Chiara Indiani, Cara Cassino, Paul Boni, and Gladys Moreira-Olsen for reviewing the manuscript; Alfredo Barea and Nicholas Caliendo for technical assistance; Nadine Soplop and Kunihiro Uryo (Electron Microscopy Resource Center at The Rockefeller University) for electron microscopy; and Bernard Beall (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) and Mary Windels (The Rockefeller University) for providing streptococcal strains.

The work of Raymond Schuch, Babar K. Khan, Jimmy A. Rotolo, and Michael Wittekind was supported by the ContraFect Corporation. The work of Assaf Raz was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grant AI11822 (to Vincent A. Fischetti).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02666-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hall-Stoodley L, Costerton JW, Stoodley P. 2004. Bacterial biofilms: from the natural environment to infectious diseases. Nat Rev Microbiol 2:95–108. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. 1999. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science 284:1318–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bjarnsholt T, Ciofu O, Molin S, Givskov M, Hoiby N. 2013. Applying insights from biofilm biology to drug development–can a new approach be developed? Nat Rev Drug Discov 12:791–808. doi: 10.1038/nrd4000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies D. 2003. Understanding biofilm resistance to antibacterial agents. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2:114–122. doi: 10.1038/nrd1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Potera C. 1999. Forging a link between biofilms and disease. Science 283:1837, 1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lebeaux D, Chauhan A, Rendueles O, Beloin C. 2013. From in vitro to in vivo models of bacterial biofilm-related infections. Pathogens 2:288–356. doi: 10.3390/pathogens2020288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flemming HC, Wingender J. 2010. The biofilm matrix. Nat Rev Microbiol 8:623–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savage VJ, Chopra I, O'Neill AJ. 2013. Staphylococcus aureus biofilms promote horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:1968–1970. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02008-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Høiby N, Bjarnsholt T, Givskov M, Molin S, Ciofu O. 2010. Antibiotic resistance of bacterial biofilms. Int J Antimicrob Agents 35:322–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tseng BS, Zhang W, Harrison JJ, Quach TP, Song JL, Penterman J, Singh PK, Chopp DL, Packman AI, Parsek MR. 2013. The extracellular matrix protects Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms by limiting the penetration of tobramycin. Environ Microbiol 15:2865–2878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lechner S, Lewis K, Bertram R. 2012. Staphylococcus aureus persisters tolerant to bactericidal antibiotics. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 22:235–244. doi: 10.1159/000342449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiedrowski MR, Horswill AR. 2011. New approaches for treating staphylococcal biofilm infections. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1241:104–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor PK, Yeung AT, Hancock RE. 2014. Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms: towards the development of novel antibiofilm therapies. J Biotechnol 191:121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meije Y, Almirante B, Del Pozo JL, Martin MT, Fernandez-Hidalgo N, Shan A, Basas J, Pahissa A, Gavalda J. 2014. Daptomycin is effective as antibiotic-lock therapy in a model of Staphylococcus aureus catheter-related infection. J Infect 68:548–552. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darouiche RO, Mansouri MD, Zakarevicz D, Alsharif A, Landon GC. 2007. In vivo efficacy of antimicrobial-coated devices. J Bone Joint Surg Am 89:792–797. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belyansky I, Tsirline VB, Montero PN, Satishkumar R, Martin TR, Lincourt AE, Shipp JI, Vertegel A, Heniford BT. 2011. Lysostaphin-coated mesh prevents staphylococcal infection and significantly improves survival in a contaminated surgical field. Am Surg 77:1025–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ketonis C, Parvizi J, Jones LC. 2012. Evolving strategies to prevent implant-associated infections. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 20:478–480. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-20-07-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berra L, Kolobow T, Laquerriere P, Pitts B, Bramati S, Pohlmann J, Marelli C, Panzeri M, Brambillasca P, Villa F, Baccarelli A, Bouthors S, Stelfox HT, Bigatello LM, Moss J, Pesenti A. 2008. Internally coated endotracheal tubes with silver sulfadiazine in polyurethane to prevent bacterial colonization: a clinical trial. Intensive Care Med 34:1030–1037. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1100-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flores-Mireles AL, Pinkner JS, Caparon MG, Hultgren SJ. 2014. EbpA vaccine antibodies block binding of Enterococcus faecalis to fibrinogen to prevent catheter-associated bladder infection in mice. Sci Transl Med 6:254ra127. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brady RA, O'May GA, Leid JG, Prior ML, Costerton JW, Shirtliff ME. 2011. Resolution of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm infection using vaccination and antibiotic treatment. Infect Immun 79:1797–1803. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00451-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Loughlin CT, Miller LC, Siryaporn A, Drescher K, Semmelhack MF, Bassler BL. 2013. A quorum-sensing inhibitor blocks Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence and biofilm formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:17981–17986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316981110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambanthamoorthy K, Sloup RE, Parashar V, Smith JM, Kim EE, Semmelhack MF, Neiditch MB, Waters CM. 2012. Identification of small molecules that antagonize diguanylate cyclase enzymes to inhibit biofilm formation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:5202–5211. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01396-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de la Fuente-Núñez C, Reffuveille F, Haney EF, Straus SK, Hancock RE. 2014. Broad-spectrum anti-biofilm peptide that targets a cellular stress response. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004152. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de la Fuente-Núñez C, Korolik V, Bains M, Nguyen U, Breidenstein EB, Horsman S, Lewenza S, Burrows L, Hancock RE. 2012. Inhibition of bacterial biofilm formation and swarming motility by a small synthetic cationic peptide. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:2696–2704. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00064-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leite B, Gomes F, Teixeira P, Souza C, Pizzolitto E, Oliveira R. 2011. In vitro activity of daptomycin, linezolid and rifampicin on Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms. Curr Microbiol 63:313–317. doi: 10.1007/s00284-011-9980-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luther MK, Arvanitis M, Mylonakis E, LaPlante KL. 2014. Activity of daptomycin or linezolid in combination with rifampin or gentamicin against biofilm-forming Enterococcus faecalis or E. faecium in an in vitro pharmacodynamic model using simulated endocardial vegetations and an in vivo survival assay using Galleria mellonella larvae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:4612–4620. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02790-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alves DR, Gaudion A, Bean JE, Perez Esteban P, Arnot TC, Harper DR, Kot W, Hansen LH, Enright MC, Jenkins AT. 2014. Combined use of bacteriophage K and a novel bacteriophage to reduce Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:6694–6703. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01789-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaplan JB, LoVetri K, Cardona ST, Madhyastha S, Sadovskaya I, Jabbouri S, Izano EA. 2012. Recombinant human DNase I decreases biofilm and increases antimicrobial susceptibility in staphylococci. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 65:73–77. doi: 10.1038/ja.2011.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaplan JB. 2009. Therapeutic potential of biofilm-dispersing enzymes. Int J Artif Organs 32:545–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Craigen B, Dashiff A, Kadouri DE. 2011. The use of commercially available alpha-amylase compounds to inhibit and remove Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Open Microbiol J 5:21–31. doi: 10.2174/1874285801105010021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lamppa JW, Griswold KE. 2013. Alginate lyase exhibits catalysis-independent biofilm dispersion and antibiotic synergy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:137–145. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01789-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fischetti VA, Nelson D, Schuch R. 2006. Reinventing phage therapy: are the parts greater than the sum? Nat Biotechnol 24:1508–1511. doi: 10.1038/nbt1206-1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Entenza JM, Loeffler JM, Grandgirard D, Fischetti VA, Moreillon P. 2005. Therapeutic effects of bacteriophage Cpl-1 lysin against Streptococcus pneumoniae endocarditis in rats. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:4789–4792. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.11.4789-4792.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmelcher M, Donovan DM, Loessner MJ. 2012. Bacteriophage endolysins as novel antimicrobials. Future Microbiol 7:1147–1171. doi: 10.2217/fmb.12.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pastagia M, Schuch R, Fischetti VA, Huang DB. 2013. Lysins: the arrival of pathogen-directed anti-infectives. J Med Microbiol 62:1506–1516. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.061028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roach DR, Donovan DM. 2015. Antimicrobial bacteriophage-derived proteins and therapeutic applications. Bacteriophage 5:e1062590. doi: 10.1080/21597081.2015.1062590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sass P, Bierbaum G. 2007. Lytic activity of recombinant bacteriophage phi11 and phi12 endolysins on whole cells and biofilms of Staphylococcus aureus. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:347–352. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01616-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Domenech M, Garcia E, Moscoso M. 2011. In vitro destruction of Streptococcus pneumoniae biofilms with bacterial and phage peptidoglycan hydrolases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:4144–4148. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00492-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Linden SB, Zhang H, Heselpoth RD, Shen Y, Schmelcher M, Eichenseher F, Nelson DC. 2014. Biochemical and biophysical characterization of PlyGRCS, a bacteriophage endolysin active against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 99:741–752. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5930-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen Y, Koller T, Kreikemeyer B, Nelson DC. 2013. Rapid degradation of Streptococcus pyogenes biofilms by PlyC, a bacteriophage-encoded endolysin. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:1818–1824. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gutiérrez D, Ruas-Madiedo P, Martinez B, Rodriguez A, Garcia P. 2014. Effective removal of staphylococcal biofilms by the endolysin LysH5. PLoS One 9:e107307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meng X, Shi Y, Ji W, Meng X, Zhang J, Wang H, Lu C, Sun J, Yan Y. 2011. Application of a bacteriophage lysin to disrupt biofilms formed by the animal pathogen Streptococcus suis. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:8272–8279. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05151-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schuch R, Lee HM, Schneider BC, Sauve KL, Law C, Khan BK, Rotolo JA, Horiuchi Y, Couto DE, Raz A, Fischetti VA, Huang DB, Nowinski RC, Wittekind M. 2014. Combination therapy with lysin CF-301 and antibiotic is superior to antibiotic alone for treating methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-induced murine bacteremia. J Infect Dis 209:1469–1478. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mascio CT, Alder JD, Silverman JA. 2007. Bactericidal action of daptomycin against stationary-phase and nondividing Staphylococcus aureus cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:4255–4260. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00824-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Praagh AD, Li T, Zhang S, Arya A, Chen L, Zhang XX, Bertolami S, Mortin LI. 2011. Daptomycin antibiotic lock therapy in a rat model of staphylococcal central venous catheter biofilm infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:4081–4089. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00147-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmelcher M, Powell AM, Becker SC, Camp MJ, Donovan DM. 2012. Chimeric phage lysins act synergistically with lysostaphin to kill mastitis-causing Staphylococcus aureus in murine mammary glands. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:2297–2305. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07050-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Becker SC, Foster-Frey J, Donovan DM. 2008. The phage K lytic enzyme LysK and lysostaphin act synergistically to kill MRSA. FEMS Microbiol Lett 287:185–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Loeffler JM, Fischetti VA. 2003. Synergistic lethal effect of a combination of phage lytic enzymes with different activities on penicillin-sensitive and -resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:375–377. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.1.375-377.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Donovan DM. 2007. Bacteriophage and peptidoglycan degrading enzymes with antimicrobial applications. Recent Pat Biotechnol 1:113–122. doi: 10.2174/187220807780809463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dastgheyb S, Hammoud S, Ketonis C, Liu AY, Fitzgerald K, Parvizi J, Purtill J, Ciccotti M, Shapiro IM, Otto M, Hickok NJ. 2015. Staphylococcal persistence due to biofilm formation in synovial fluid containing prophylactic cefazolin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:2122–2128. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04579-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu H, Moser C, Wang HZ, Hoiby N, Song ZJ. 2014. Strategies for combating bacterial biofilm infections. Int J Oral Sci 7:1–7. doi: 10.1038/ijos.2014.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hall Snyder AD, Vidaillac C, Rose W, McRoberts JP, Rybak MJ. 2014. Evaluation of high-dose daptomycin versus vancomycin alone or combined with clarithromycin or rifampin against Staphylococcus aureus and S. epidermidis in a novel in vitro PK/PD model of bacterial biofilm. Infect Dis Ther 4:51–65. doi: 10.1007/s40121-014-0055-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baldoni D, Furustrand Tafin U, Aeppli S, Angevaare E, Oliva A, Haschke M, Zimmerli W, Trampuz A. 2013. Activity of dalbavancin, alone and in combination with rifampicin, against meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a foreign-body infection model. Int J Antimicrob Agents 42:220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hengzhuang W, Wu H, Ciofu O, Song Z, Hoiby N. 2011. Pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of colistin and imipenem on mucoid and nonmucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:4469–4474. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00126-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stoodley P, Conti SF, DeMeo PJ, Nistico L, Melton-Kreft R, Johnson S, Darabi A, Ehrlich GD, Costerton JW, Kathju S. 2011. Characterization of a mixed MRSA/MRSE biofilm in an explanted total ankle arthroplasty. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 62:66–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nair N, Biswas R, Gotz F, Biswas L. 2014. Impact of Staphylococcus aureus on pathogenesis in polymicrobial infections. Infect Immun 82:2162–2169. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00059-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vandecandelaere I, Matthijs N, Nelis HJ, Depuydt P, Coenye T. 2013. The presence of antibiotic-resistant nosocomial pathogens in endotracheal tube biofilms and corresponding surveillance cultures. Pathog Dis 69:142–148. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Otto M. 2009. Staphylococcus epidermidis–the “accidental” pathogen. Nat Rev Microbiol 7:555–567. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Conlon BP. 2014. Staphylococcus aureus chronic and relapsing infections: evidence of a role for persister cells: an investigation of persister cells, their formation and their role in S. aureus disease. Bioessays 36:991–996. doi: 10.1002/bies.201400080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Conlon BP, Rowe SE, Lewis K. 2015. Persister cells in biofilm associated infections. Adv Exp Med Biol 831:1–9. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-09782-4_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dastgheyb S, Parvizi J, Shapiro IM, Hickok NJ, Otto M. 2015. Effect of biofilms on recalcitrance of staphylococcal joint infection to antibiotic treatment. J Infect Dis 211:641–650. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bjarnsholt T, Alhede M, Alhede M, Eickhardt-Sorensen SR, Moser C, Kuhl M, Jensen PO, Hoiby N. 2013. The in vivo biofilm. Trends Microbiol 21:466–474. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kwiecinski J, Kahlmeter G, Jin T. 2015. Biofilm formation by Staphylococcus aureus isolates from skin and soft tissue infections. Curr Microbiol 70:698–703. doi: 10.1007/s00284-014-0770-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schuch R, Sauve K, Ramirez RA, Raz A, Rotolo J, Wittekind W. 2015. Lysin CF-301 activates daptomycin in pulmonary surfactant in vitro and rescues mice from lethal staphylococcal pneumonia, abstr F-290b Abstr 55th Intersci Conf Antimicrob Agents Chemother, San Diego, CA, 30 May to 2 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baba T, Bae T, Schneewind O, Takeuchi F, Hiramatsu K. 2008. Genome sequence of Staphylococcus aureus strain Newman and comparative analysis of staphylococcal genomes: polymorphism and evolution of two major pathogenicity islands. J Bacteriol 190:300–310. doi: 10.1128/JB.01000-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Charpentier E, Anton AI, Barry P, Alfonso B, Fang Y, Novick RP. 2004. Novel cassette-based shuttle vector system for Gram-positive bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:6076–6085. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.10.6076-6085.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sá-Leão R, Santos Sanches I, Dias D, Peres I, Barros RM, de Lencastre H. 1999. Detection of an archaic clone of Staphylococcus aureus with low-level resistance to methicillin in a pediatric hospital in Portugal and in international samples: relics of a formerly widely disseminated strain? J Clin Microbiol 37:1913–1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stepanović S, Vukovic D, Hola V, Di Bonaventura G, Djukic S, Cirkovic I, Ruzicka F. 2007. Quantification of biofilm in microtiter plates: overview of testing conditions and practical recommendations for assessment of biofilm production by staphylococci. APMIS 115:891–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2007.apm_630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2012. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard, 9th ed Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Izano EA, Sadovskaya I, Wang H, Vinogradov E, Ragunath C, Ramasubbu N, Jabbouri S, Perry MB, Kaplan JB. 2008. Poly-N-acetylglucosamine mediates biofilm formation and detergent resistance in Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. Microb Pathog 44:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grohs P, Fantin B, Lefort A, Wolff M, Gutmann L, Mainardi JL. 2011. Differences in daptomycin and vancomycin ex vivo behaviour can lead to false interpretation of negative blood cultures. Clin Microbiol Infect 17:1264–1267. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fernández-Barat L, Ferrer M, Sierra JM, Soy D, Guerrero L, Vila J, Li Bassi G, Cortadellas N, Martinez-Olondris P, Rigol M, Esperatti M, Luque N, Saucedo LM, Agusti C, Torres A. 2012. Linezolid limits burden of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in biofilm of tracheal tubes. Crit Care Med 40:2385–2389. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31825332fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stiefel P, Rosenberg U, Schneider J, Mauerhofer S, Maniura-Weber K, Ren Q. 2016. Is biofilm removal properly assessed? Comparison of different quantification methods in a 96-well plate system. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 100:4135–4145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Guzman LM, Belin D, Carson MJ, Beckwith J. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J Bacteriol 177:4121–4130. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schuch R, Fischetti VA. 2006. Detailed genomic analysis of the Wβ and γ phages infecting Bacillus anthracis: implications for evolution of environmental fitness and antibiotic resistance. J Bacteriol 188:3037–3051. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.8.3037-3051.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moody J. 2010. Synergy testing: broth microdilution checkerboard and broth macrodilution methods, p 5.12.11–15.12.23. In Garcia LS. (ed), Clinical microbiology procedures handbook, vol 2 ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tallarida RJ. 2012. Revisiting the isobole and related quantitative methods for assessing drug synergism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 342:2–8. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.193474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.