Abstract

Quantitative myocardial and blood T1 have recently achieved clinical utility in numerous pathologies, as they provide non-invasive tissue characterization with the potential to replace invasive biopsy. Native T1 time (no contrast agent), changes with myocardial extracellular water (edema, focal or diffuse fibrosis), fat, iron, and amyloid protein content. After contrast, the extracellular volume fraction (ECV) estimates the size of the extracellular space and identifies interstitial disease. Spatially resolved quantification of these biomarkers (so-called T1 mapping and ECV mapping) are steadily becoming diagnostic and prognostically useful tests for several heart muscle diseases, influencing clinical decision-making with a pending second consensus statement due mid-2017. This review outlines the physics involved in estimating T1 times and summarizes the disease-specific clinical and research impacts of T1 and ECV to date. We conclude by highlighting some of the remaining challenges such as their community-wide delivery, quality control, and standardization for clinical practice.

Keywords: T1 mapping, Extracellular volume, Myocardial disease

Introduction

In magnetic resonance imaging, the longitudinal (spin-lattice) relaxation time (T1) is a fundamental tissue property, now measurable in the myocardium using cardiac T1 mapping sequences. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) research data accrued in both animals and humans convincingly demonstrate that native T1, in the absence of gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCA), lengthens with interstitial expansion caused by edema, infarction, amyloid infiltration, and fibrosis [1]. Conversely, native T1 shortens in the presence of fat and iron accumulation. The left ventricular (LV) myocardial native T1 signal, from a single region of interest on a T1 map, could therefore serve as a simple, on-the-fly, non-invasive discriminator of heart muscle health and disease.

T1-weighted signal also forms the basis of the late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) imaging technique. This technique was the most disruptive tissue characterization method. LGE can quantify focal scar and fibrosis in both ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathies. It works by the principle that scarred tissue passively accumulates more GBCA which shortens its T1 compared to adjacent normal healthy myocardium, and this is visible with a particular imaging sequence (inversion recovery) [2]. T1 mapping adds to this. It has evolved from T1-weighted imaging, to native T1 measurement alone, to post-GBCA T1 measurement in isolation, or through the partition coefficient to measurement of the extracellular volume (ECV) [3]. The latter is when T1 is measured before and after GBCA using a correction for the hematocrit (measured separately or in-line automated) [4, 5]. Native T1 and ECV permit earlier diagnosis and quantitative assessment of focal as well as diffuse myocardial disease (Fig. 1). T1 mapping by CMR describes the pixel-wise quantification of the spin-lattice relaxation time in order to provide a quantitative tissue characterization that is commonly viewed as a color-coded map of the heart. T1 maps are most commonly derived from a series of T1-weighted images, sampling the T1 recovery curve after one or more initial preparation pulses.

Fig. 1.

Summary of myocardial biological changes inferred by T1 mapping technologies. ↑ = significant increase; ↓ = significant decrease; − = no significant change; X = no data available. ECV extracellular volume, AL Amyloid amyloid light chain, TTR amyloidosis transthyretin amyloidosis

This review outlines the basic physics of T1 mapping and discusses disease-specific clinical and research impacts of T1 and ECV to date. We conclude by highlighting the challenges of community-wide delivery, quality control, and standardization in clinical practice.

Essential physics and evolution of T1 mapping sequences

Broadly, T1 mapping sequences have three parts: (1) the T1 magnetization preparation pulse, (2) a single image acquisition (readout) after a variable delay, and (3) variable repetitions of (1) and (2) to sample the longitudinal magnetization recovery curve after the magnetization preparation. Raw images are then reconstructed by post-processing into a single T1 map using a theoretical model of the expected signal intensity [3] and with the help of various refinements such as respiratory motion compensation (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Overview of salient T1 mapping sequences comparing building plans, strengths, and limitationsa

| Sequence | Building plan: 3 integral parts | Strength | Limitation | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 preparation | Imaging readout | Respiratory motion compensation | ||||

| Original MOLLI | IR pulse over multiple heartbeats | Single-shot end-diastolic bSSFP | Single breath-hold | – High-quality T1 maps – Good precision (noise resilience) – Widely available – High inter-center reproducibility |

– T1 time dependence on T2, MT, and sequence parameters – HR dependence |

[6] |

| Fixed-recovery MOLLI | IR pulse over multiple heartbeats | Single-shot end-diastolic bSSFP | Single 11-s breath-hold | – Little HR variability – Separate optimization allows precision for both native and post-GBCA regimes |

– Requires different protocols for native and post-GBCA scans | [7] |

| ShMOLLI | IR pulse over multiple heartbeats | Single-shot end-diastolic bSSFP | Single short 9-s breath-hold | – Short breath-holds via short rest periods of 1 heartbeat – Incomplete magnetization recovery compensated for by conditional data fit – Unified sequence for pre-/post-GBCA scanning – Little HR variability |

– Low number of fit images available for use especially in native mapping – Vulnerable to mistriggering as sampling sparse |

[8] |

| FLASH-MOLLI | IR pulse over multiple heartbeats | Single-shot end-diastolic FLASH | Single 11-s breath-hold | – Avoids off-resonance artifacts (good for high-field strengths) – No T2 dependence – Tailored fitting compensates for disruption of relaxation by FLASH pulses improving accuracy compared to original MOLLI |

– Decreased SNR compared to SSFP schemes – Elaborate post-processing limits availability |

[9] |

| TRASSI | IR pulse over multiple heartbeats | Radial golden-angle FLASH | Single short 5-s breath-hold | – Inherent properties of the radial acquisition, short breath-hold, and HR-adaptable acquisition window provide high resilience to motion artifacts – Tailored fit improves accuracy |

– Potential blurring due to view-sharing across heartbeats – Little baseline data – Elaborate post-processing limits availability |

[10] |

| SASHA | SR preparation over multiple heartbeats | Single-shot bSSFP | Single 10-s breath-hold | – Excellent accuracy as invariant to T2, MT, and inversion efficiency – Alternative reconstruction scheme has been proposed to trade off accuracy against precision – High-contrast imaging scheme available for free-breathing applications |

– Still low precision compared to MOLLI – Low SNR baseline images more prone to artifacts – Low blood-myocardial imaging contrast makes post-processing with image registration challenging |

[11] |

| SMART1 MAP | A series of single-point SR experiments | Single-shot bSSFP | Single breath-hold (13 heartbeats) | – Intra-scan heart rate insensitivity by adapting recovery time to changing heart rates by measuring heartbeats in real time – Good accuracy compared to MOLLI |

– Limited data on in vivo clinical applicability; has yet to be validated at scale and on other vendor platforms | [12, 13] |

| SAPPHIRE | Hybrid SR/IR over multiple heartbeats | Single-shot bSSFP | Single 10-s breath-hold | – Good accuracy compared to MOLLI – Improved precision compared to SASHA |

– Lower precision compared to MOLLI – Low SNR images are prone to artifacts |

[14] |

| STONE | IR pulse over multiple heartbeats | Single-shot bSSFP | Interleaved multi (5)-slice 55 s free-breathing + registration + real-time slice tracking | – No rest periods between breath-holds as free-breathing improves patient comfort – Improved accuracy due to slice-interleaved scanning |

– Potential for slice-tracking failure in heavy breathing patients – Perturbation of blood T1 times due to crosstalk between slices |

[15] |

| ANGIE | IR pulse over multiple heartbeats | Segmented bSSFP | 41 s free-breathing + diaphragmatic navigator gating | – No rest periods between breath-holds as free-breathing improves patient comfort – Enables high-resolution scans – Motion compensation robust to heavy breathing |

– Accuracy comparable to MOLLI (not superior) – Elaborate compressed sensing reconstruction needed before the fit which limits availability |

[16] |

ANGIE Accelerated and Navigator-Gated Look-Locker Imaging for cardiac T1 Estimation, bSSFP balanced steady-state free precession, FLASH fast low-angle shot, GBCA gadolinium-based contrast agents, HR heart rate, IR inversion recovery, MOLLI MOdified Look-Locker Inversion Recovery, MT magnetization transfer, s second(s), SAPPHIRE SAturation Pulse Prepared Heart-Rate Independent Inversion REcovery Sequence, SASHA SAturation Recovery Single SHot Acquisition, ShMOLLI shortened MOLLI, SNR signal-to-noise ratio, SR saturation recovery, STONE slice-interleaved T1 mapping

aList of T1 mapping sequences is not exhaustive—more variants exist in the published literature that may not be recapitulated here

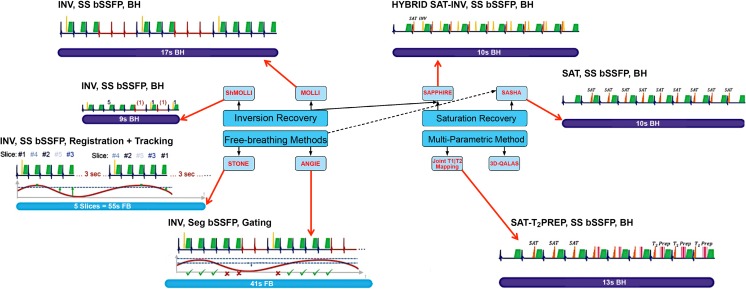

Fig. 2.

Illustrated overview of T1 mapping acquisition strategies. The techniques are divided into four major groups: MOLLI, saturation recovery, free-breathing methods, and multi-parameter imaging. The graphs diagrammatically represent the inversion pulse and acquisition times across heartbeats. Diaphragmatic movement during image acquisition is shown for the free-breathing methods STONE and ANGIE. Technical details of described T1 mapping acquisition strategies are described in Table 1. ANGIE Accelerated and Navigator-Gated Look-Locker Imaging for Cardiac T1 Estimation, BH breath-hold, bSSFP balanced steady-state free precession, 3D-QALAS three-dimensional-QuAntification using an interleaved Look-Locker Acquisition Sequence with T2 preparation pulse, INV inversion, FB free-breathing, MOLLI Modified Look-Locker Inversion, Prep preparation, SAPPHIRE Saturation Pulse Prepared Heart-Rate Independent Inversion REcovery Sequence, SASHA saturation recovery single shot acquisition, SAT saturation, Seg segmented, ShMOLLI shortened MOLLI, SS single shot, STONE slice-interleaved T1 mapping sequence

A T1 map is a two-dimensional (usually brightly colored) slice image where each image pixel displays the T1 relaxation time (ms) using a color look-up table to facilitate visual assessment [17]. Imaging at identical time points of the cardiac cycle is needed to yield co-registered images for curve-fitting and spatially resolved quantification of T1 [6]. Earlier T1 measurement approaches did not do this and became obsolete [18]. When combining raw images, some errors may therefore stem from RR-interval variability (arrhythmia, mistriggering), through-plane cardiac motion that is a normal part of longitudinal cardiac function, and diaphragmatic motion due to respiration. Automated non-rigid registration algorithms can correct for the position of source images to avoid some of this [19, 20]. Acquisition recommendations are now made to minimize other potential sources of errors in sequences and scan planning. For example, operators must aim to minimize partial volume effects by optimal slice orientation relative to the tissue, which is preferably orthogonal to the imaging plane to minimize obliquity. Proper adjustment of the shim volume and center frequency should be ensured to minimize off resonance artifacts [21]. A typical scan protocol is provided in the 2013 SCMR consensus statement [18].

T1 mapping is complex as different approaches are taken with different names. The original Look-Locker sequence developed in the 1970s [22] applied multiple inversion recovery pulses with different times-to-inversion, generating 20 distinct T1-weighted images. The inversion pulse inverted the net magnetization by 180° and was followed by multiple readout pulses interspersed with longitudinal magnetization recovery periods. However, as the relaxation curve was repeatedly perturbed by radiofrequency (RF) pulses of the imaging readout, an “apparent” T1 (T1*) was assessed and it required further correction for relaxation time measurement [23, 24]. The original Look-Locker was impractical for generating T1 maps, as acquisition, lasting 20 min, spanned multiple phases of the cardiac cycle [22]. Use of a new single-shot balanced steady-state free precession (SSFP) readout during diastole [25] permitted better signal-to-noise ratio and efficiency, intrinsic flow compensation [3], and consequently the development of the first MOdified Look-Locker Inversion Recovery (MOLLI) [6] approach in a single breath-hold of 17 heartbeats [26]. New MOLLI variants manipulate the prepulses and pauses between them. For example, the original MOLLIs used a 3(3b)3(3b)5 protocol, with numbers outside of parentheses indicating the number of images acquired after each magnetization preparation pulse, and numbers in parentheses indicating the length of the pause separating image acquisition and any subsequent magnetization preparation pulse, defined either in terms of number of recovery beats (b) or number of seconds (s). MOLLI’s bSSFP readout also estimates an “apparent” T1 (T1*) which is influenced by imaging RF pulses, so a Look-Locker correction is still needed to correct for it and deliver a more accurate T1 estimate [25]. Later versions, like the 5(3 s)3 variant [11], which shifts the bulk of image acquisition to the “beginning,” allow more time for recovery of longitudinal magnetization. Counting rest periods in seconds instead of recovery beats makes sequences more heart rate independent. Another approach, Shortened MOLLI [8] (ShMOLLI), uses a 5(1b)1(1b)1 scheme to acquire images over nine heartbeats making it more suitable for breathless patients [25]. The resultant dataset is however sparser and the one-beat pauses are insufficient to maintain compatibility with the theoretical model used in subsequent T1 estimation, for large T1 values [3]. ShMOLLI, therefore, employs a conditional fitting algorithm that includes the final two image acquisitions in the curve fitting routine only when the T1 estimate tends toward a smaller value [3]. The same Look-Locker correction as for MOLLI is applied. SAturation Recovery Single SHot Acquisition [11] (SASHA) uses a saturation recovery instead of an inversion recovery preparation. Dephasing the whole imaging volume leads to depletion of the entire magnetization, alleviating the need for any rest periods. Because only one image is acquired after each magnetization preparation, the Look-Locker correction is not required and T1 can be estimated directly from pixel-wise curve fitting [3]. Unlike MOLLI, SASHA does not demonstrate heart rate dependence [26], but it can be less precise on account of the reduced dynamic range (90° vs. 180°). SASHA acquires 10 images in 10 heartbeats with the initial image lacking a saturation preparation [11]. SAturation Pulse Prepared Heart-Rate Independent Inversion REcovery Sequence (SAPPHIRE) uses a hybrid combination of both inversion and saturation pulses that increases the dynamic range (a hybrid of MOLLI and SASHA, trying to get the best of both). Additional comparator sequences are elaborated in Table 1 .

Biological basis of ECV

The myocardium can be considered as two main compartments: the “intracellular cellular volume” (ICV, 1 − ECV), dominated by myocytes but also including all other cells (fibroblasts, circulating red blood cells, etc.); and the “extracellular volume,” dominated water associated with the extracellular matrix but also including the intracapillary plasma volume [18]. The normal myocardial ECV value is around 25.3 ± 3.5% in health [27]. This is much higher than, for example, skeletal muscle, where the ECV may be 10%—myocardium has a lot more collagen (Tables 2 and 3). Various pathophysiological processes alter the ECV and ICV. We now know that athletic adaptation inducing left ventricular hypertrophy reduces the myocardial ECV, meaning that cellular hypertrophy is outweighing fibrosis increases [40]. The ECV may increase with fibrosis, edema, or other protein deposition (amyloid) [46]—or a combination [47]. However, increased capillary density or vasodilatation would also increase ECV, although to a smaller extent [48]. Therefore, ECV changes in isolation require interpretation.

Table 2.

Typical ranges of native myocardial T1 in myocardial disease

| Condition | Native T1

a

[T; sequence; n] |

Z valueb | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aortic stenosis | 1191 ± 34 [3 T; MOLLI; 20] |

+0.4 | Chin et al. 2014 [28] |

| Essential hypertension | 955 ± 30 [1.5 T; ShMOLLI; 40] |

–0.3 | Treibel et al. 2015 [29] |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 1026 ± 64 [1.5 T; ShMOLLI; 46] |

+1.7 | Fontana et al. 2014 [30] |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 1056 ± 62 [1.5 T; MOLLI; 29] |

+0.9 | aus dem Siepen et al. 2015 [31] |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 1245 ± 75 [1.5 T; MOLLI; 40] |

+9.8 ♦ | Bulluck et al. 2016 [32] |

| Fabry disease | 853 ± 50 [1.5 T; ShMOLLI; 38] |

–3.6 ♦ | Pica et al. 2014 [33] |

| Iron overload | 863 ± 138 [1.5 T; ShMOLLI; 53] |

–4.1 ♦ | Sado et al. 2015 [34] |

| Light chain amyloidosis | 1130 ± 68 [1.5 T; ShMOLLI; 79] |

+4.8 ♦ | Fontana et al. 2014 [30] |

| Transthyretin amyloidosis | 1097 ± 43 [1.5 T; ShMOLLI; 85] |

+3.8 ♦ | Fontana et al. 2014 [30] |

| Acute myocarditis | 1064 ± 37 [1.5 T; MOLLI, 61] |

+6.2 ♦ | Hinojar et al. 2015 [35] |

| Convalescent myocarditis | 995 ± 19 [1.5 T; MOLLI; 67] |

+2.8 ♦ | Hinojar et al. 2015 [35] |

T1 values per disease were derived from at least one representative work in the published literature (other relevant works exist that have not been referenced here). Reported ranges are only applicable to the sequence, imaging protocol, field strength, and scanner configuration used by the group and are not necessarily immediately generalizable across centers [18]. The native T1 signal in some diseases (annotated by “♦”) shows a large deviation (multiple SDs) from normality, so T1 mapping is bound to be more robust here as the pathology-related T1 change trumps any “normal” biases that confound T1 estimates. In other heart muscle diseases, however (e.g., hypertensive heart disease, aortic stenosis), where T1 changes are less dramatic, biases in T1 estimates may become major signal pollutants, so pathology-related T1 differences may not be realistically resolvable except through large, standardized studies

SD standard deviation, T Tesla. Other abbreviations as in Table 1

aReported in milliseconds as mean ± SD. Defines field-strength (T), sequence used, and sample size (n) of the diseased cohort

bNumber of SDs by which a particular disease’s mean T1 value lies above or below the healthy control mean T1 reported by the group in the same study

Table 3.

Measured ECV relationship in some heart muscle disease

| Condition | ECVa (%) [T; n] | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Acute myocardial infarction | ⇑ 56 ± 1.4 [1.5 T; 39] |

Kidambi et al. 2016 [36] |

| Aortic stenosis|| | ↔ 24.3 ± 1.9 [3 T; 50] ⇑ 28.3 ± 1.7 [3 T; 20] |

Singh et al. 2015 [37] |

| Chin et al. 2014 [28] | ||

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | ⇑ 37.1 ± 10.1 [3 T; 50] |

Swoboda et al. 2017 [38] |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | ⇑ 27 ± 4 [1.5 T; 29] |

aus dem Siepen et al. 2015 [31] |

| Systolic heart failure | ⇑ 31.2, 29.0–34.1~

[3 T; 40] |

Su et al. 2014 [39] |

| Heart failure preserved ejection fraction | ⇑ 28.9, 27.8–31.3~

[3 T; 62] |

Su et al. 2014 [39] |

| Athletic adaptation | ↓ 22.5 ± 2.6 [1.5 T; 30] |

McDiarmid et al. 2016 [40] |

| Fabry disease | ↔ 21.7 ± 2.4 [1.5 T; 31] |

Thompson et al. 2013 [41] |

| Iron overload | ⇑ 31.3 ± 2.8 [1.5 T; 19] |

Hanneman et al. 2016 [42] |

| Light chain amyloidosis | ⇑ 54 ± 7 [1.5 T; 92] |

Fontana et al. 2015 [43] |

| Transthyretin amyloidosis | ⇑ 60 ± 7 [1.5 T; 44] |

Fontana et al. 2015 [44] |

| Acute myocarditis | ⇑ 30, 27–32§

[1.5 T; 48] |

Bohnen et al. 2017 [45] |

ECV extracellular volume. Other abbreviations as in Table 2

↑ increase, ↓ decrease, ⇑ marked increase, ↔ static

aCited ECV values (%) are as mean ± SD except where otherwise stated. Field-strength (T) and sample size (n) are additionally provided. ECV ranges per disease were derived from at least one representative work in the published literature (other relevant works exist that have not been referenced here)

||Conflicting data currently

§Median, first, and third quartiles

~Mean, interquartile range

Mathematical derivation of the ECV (Eq. 1) relies on (1) a number of assumptions (including the fast-exchange limit as reviewed elsewhere) [3], (2) measurement of the partition coefficient (the bold right half of Eq. 1, also known as λ), and (3) the patient’s hematocrit (Hct) representing the cellular fraction of blood [2].

| 1 |

T1 mapping and ECV in selected high signal diseases

Lipid storage disease

Fabry disease (FD) is an intracellular lysosomal storage disease caused by the accumulation of globotriaosylceramide in tissues due to a deficiency in the enzyme α-galactosidase A [49]. Cardiac involvement causes concentric LVH, arrhythmias, and heart failure, and it is the major cause of mortality [50]. This lipid (in classic lamellar bodies) probably causes the native myocardial T1 to be low, and the result is that T1 mapping can reliably differentiate between FD, other forms of LVH, and healthy controls [51]. T1 lowering is seen in 50–60% of subjects before LVH (Fig. 3c), so it is a biomarker of early cardiac involvement [51], correlating with reduced global longitudinal strain by echocardiography [33]. Because ECV primarily reflects extracellular interstitial disease, it misses the intracellular lysosomal storage, but there may be future roles for late phenotype development as diffuse fibrosis starts [41]. In the infero-lateral wall, where FD has LGE, segmental T1 and T2 elevation may occur (where the pseudo-normalized or elevated T1 is likely due to the effects of replacement fibrosis dominating the fatty-related T1 decrease) and these correlate with blood troponin suggesting that chronic inflammation may be contributing [52]. Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) for FD may be most beneficial if started sufficiently early, before the establishment of permanent changes [53], but ERT is expensive and early initiation carries societal implications. T1 mapping, capable of detecting early cardiac involvement in FD, could therefore have a major role in guiding timing of commencement of ERT and drug monitoring [33].

Fig. 3.

The practical clinical utility of T1 mapping in selected heart muscle diseases. a Cardiac amyloidosis showing marked septal thickening. There is high native T1 (1270 ms in the septum) and near transmural and myocardial enhancement and severe expansion of the ECV is predicted (in-line synthetic ECV 49). b Acute myocarditis showing abnormal myocardium tissue characterization with high native T1 (1345 ms in the septum) and T2 (71 ms in the septum), extensive LGE, and high ECV (in-line synthetic ECV 54). c Fabry disease showing no LV hypertrophy (early-phenotype) and low native T1 globally (877 ms) except for the basal infero-lateral wall, co-locating with no-ischemic fibrosis. ECV is normal. d Cardiac iron overload in a thalassemic patient showing T2* 8 ms and native T1 reduction to 670–750 ms by MOLLI. ECV extracellular volume fraction, FB free-breathing, FISP fast imaging with steady-state precession, GBCA gadolinium-based contrast agent, LGE late gadolinium enhancement, LV left ventricle, MOCO motion-corrected, MOLLI modified Look-Locker inversion recovery, PSIR phase-sensitive inversion recovery, SSFP steady-state free precession

Myocarditis

Myocardial inflammation is a key step in the development of multiple cardiac diseases. CMR tissue characterization has major potential in its diagnosis. The 2009 “Lake Louise” myocarditis criteria, drafted before mapping was widespread, require the presence of two out of the following three findings: increased myocardial edema by T2-weighted imaging, non-ischemic mid-wall LGE, and hyperemia/capillary leak on early gadolinium enhancement imaging [54]. These are known to be insensitive [55]. Mapping helps. Combining ECV (ECV cut-off ≥27%) with LGE data significantly improves the diagnostic accuracy (90% compared with 79% [54]), and normal ECV has been shown to rule out myocardial damage with a high degree of certainty [56]. Native T1 detects both intracellular and diffuse myocardial change (Fig. 3b), so it has a role in grading the severity and stage of myocardial inflammation [35, 57]. The MyoRacer trial suggests that the most useful imaging tools for confirming or refuting a diagnosis of acute myocarditis are native T1 mapping, followed by T2 mapping, ECV, and Lake Louise criteria in this descending order. By contrast, only T2 mapping showed diagnostic utility in chronic myocarditis [58]. A multiparametric CMR approach toward myocarditis is envisaged: one which exploits T1 mapping and ECV as well as T2 mapping, T2-weighted imaging, early gadolinium enhancement, LGE, and Lake Louise criteria to quantifying the extent of inflammation and distinguish between acute and chronic myocardial injury [59].

Myocardial infarction

Acute and chronic infarct imaging is done by standard LGE techniques, but T1 mapping and ECV provide complementary information, both diagnostically and prognostically. In acute myocardial infarction (MI), myocardial edema elevates the native T1 signal and the ECV. Native T1 in the infarct core can predict 6-month post-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) mortality even after adjustment for LV ejection fraction [60], and in the remote myocardium, native T1 is independently associated with LV systolic dysfunction [61]. In reperfused acute MI, acute infarct ECV, unlike standard LGE, is independently associated with ejection fraction and convalescent infarct global strain, suggesting it is a better predictor of LV functional recovery [36, 62]. Native T1 may also identify the area at risk and salvaged myocardium [63] better than T2-weighted imaging can. In chronic MI, native T1 and ECV are increased, but values are lower than those observed in acute MI [64]. Native T1 values in chronic MI by widely used bSSFP mapping methods should be interpreted with caution as T1 values may be subject to additive or subtractive bias when water and fat coexist in the myocardium—intramyocardial fat due to lipomatous metaplasia in chronic myocardial scar potentially predisposes to such T1 biases [66]. In the field of stress perfusion CMR for ischemia, T1 mapping of the spleen is being explored as a surrogate indicator of adequacy of vasodilator stress with adenosine [67]. The splenic blood flow paradoxically reduces during the course of adenosine myocardial vasodilatation and native splenic T1 decreases as a result. This makes native splenic T1 in the course of the adenosine infusion (and before GBCA administration) a potential surrogate marker of stress adequacy [67].

Cardiac amyloidosis

The ventricular myocardium is affected by immunoglobulin light chain (AL) and transthyretin (ATTR) amyloidosis, which has two subtypes, wildtype and mutant [68]. Amyloid deposits and infiltrates the myocardial interstitium and is the major determinant of outcome [43]. Amyloidosis on LGE has characteristic appearances, particularly with the phase-sensitive inversion recovery technique. In early disease, the LGE may be normal. Later, global subendocardial LGE (but more prevalent at the base) may occur, associated with blood and myocardium nulling together. Later still, transmural LGE appears [69]. However, native myocardial T1 and ECV may have more discriminatory and predictive power than LGE [46, 70], and they change before LGE [71]. The current working hypothesis is that the ECV can be higher in ATTR due to higher cell volume (derived as 1 − ECV × myocardial mass), indicating concomitant myocyte hypertrophy [44]. Conversely, native T1 (Fig. 3a) can be higher in AL due to the influence of myocardial inflammation [30]. As treatment options differ between AL and ATTR, differentiating between the two by T1 mapping and ECV is clinically important [72].

Iron overload

Iron shortens all three CMR relaxation times—T1, T2, and T2* [73] (Fig. 3d). T2* at 1.5 Tesla (T) (but not at 3 T [74]) is the gold standard for myocardial iron overload assessment and has transformed clinical outcomes when it is used as it can target chelation therapy to where it is needed most [75]. T1 mapping has potential here as well and can serve as a complementary tool [76]. Native myocardial T1 correlates well with T2* but has the added advantage of greater reproducibility and sensitivity, and it can detect lower myocardial iron levels potentially missed by T2* [34, 42, 77–79]. In thalassemia major, for example, native T1 detected cardiac iron overload in a third of cases missed by T2* [76].

Challenges facing the roll-out of native myocardial T1 for cardiac iron assessment include the known variation of absolute T1 between sequences and scanners [78] and its non-specificity—its susceptibility to alter in a large number of heart muscle diseases. In this respect, T2* is more disease specific [80]. This advantage should not be overstated—the T1 changes of significant iron completely swamp all other pathologies—the T1 can lower by an impressive 25 standard deviations in severe iron overload, for example. The ECV can be used in iron overload, although there are concerns when iron loading is significant. The ECV can be increased in thalassemia major patients with documented cardiac iron overload, and it correlates with T2* but not with LV systolic function and global longitudinal strain [42]. The impression is that cardiac iron could be transitioning to a fibrotic phenotype, although there is little autopsy evidence for this [81].

T1 mapping and ECV in selected modest signal diseases

Dilated cardiomyopathy

In dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), diffuse myocardial fibrosis may be a prominent feature during disease progression and cardiac remodeling, which eludes depiction by LGE imaging. Early myocardial fibrosis detected by native T1 mapping in DCM [31] can predict adverse outcomes [82] allowing for risk stratification and for the initiation of timely and appropriate management. However, the T1 signal change in DCM is not large and conventional T1 mapping approaches have in-plane resolution limitations when applied to thin-walled hearts (a prevalent phenotype in DCM [83]). Native T1 is prolonged in DCM and inversely correlated with wall thickness [84, 85] where confounding by partial volume effects may play a part. During the early (subclinical) stages, hearts may have normal LV wall thickness values (~10 mm), so a conventional T1 mapping sequence could potentially be used, but once the DCM phenotype manifests (often with an increase in overall LV mass), wall thickness may or may not decline with significant partial volume implications. ECV was shown to correlate with clinical prognosis in DCM [86] and with LV systolic dysfunction [87], and although it is recommended in the 2013 T1 mapping consensus document [18], it is still not accurate enough to be of proven utility for early diagnosis and risk stratification in DCM [18, 31, 88]. T2 mapping can detect myocardial inflammation that appears to play an important role in non-ischemic DCM [89].

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Myocardial disarray, small vessel disease, and fibrosis are histopathological hallmarks of familial sarcomeric HCM. In HCM, LGE is a risk factor for heart failure and an additional risk factor for SCD [90]. T1 mapping can have additive value [91]. Native T1 is modestly elevated in HCM as compared to healthy controls and highest in the areas of maximal hypertrophy [90]. T1 may also be elevated in HCM patients without overt LV hypertrophy, suggesting potential clinical utility as an early disease biomarker [84]. Native T1 was better than ECV at discriminating HCM from hypertensive heart disease [92] and it identified subclinical HCM in sarcomere gene mutation carriers [92], although some of these have rather thin walls and crypts that could lead to partial volume effects and native T1 correlated with LV remodeling and global systolic function [85]. ECV cannot discriminate between overt HCM and DCM being similarly elevated in both, suggesting a final common pathway of interstitial change [93], but it can differentiate between sarcomeric HCM and athletic heart as the latter exhibits reduced ECV in the hypertrophied segments [94].

Valvular heart disease

Most T1 mapping studies for valvular heart disease have focused on aortic stenosis (AS). AS is associated with two forms of myocardial fibrosis: diffuse (interstitial) fibrosis that may appear prior to symptom manifestation and architectural change, and the more focal, late irreversible replacement fibrosis. Our understanding of fibrosis in AS is incomplete. Some fibrosis is clearly advantageous, but maladaptive fibrosis also occurs and the myocardial adaptation to the narrowed valve is key to the clinical impact [95]. T1 mapping can quantify the diffuse myocardial fibrosis in AS providing an indication of AS severity and cardiac function [37, 96] and histopathological correlation has been achieved [74, 97]. Mild to moderate diffuse fibrosis in AS has been linked to postoperative LVH reduction and better symptomatic improvement compared to severe fibrosis at baseline [98]. Native T1 and ECV were shown to be increased in AS [28] especially in patients with more abnormal patterns of LV remodeling, and they tracked the prognostic biomarker n-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide [29], but in another study of asymptomatic moderate/severe AS patients, native T1 and ECV did not differ significantly from those in age-matched controls at 3 T [37].

Current guidelines classify AS severity mostly by echocardiography via trans-valvular pressure and aortic valve area measurements, and intervention is recommended based on LV ejection fraction and the presence of symptoms, ignoring the myocardial state, in spite of myocardial fibrosis having been shown to determine outcomes in AS patients [99] and ECV demonstrating prognostic value post-tissue aortic valve replacement [100]. The prognostic value of ECV in AS has recently been demonstrated [101] and the “iECV,” derived from the product of ECV and body surface area-indexed LV end-diastolic volume, showed good correlation with histology [101]. Diffuse fibrosis assessment by T1 mapping in chronic mitral regurgitation may also have clinical utility to guide timing of intervention [102].

Biomarker roadmap for T1 mapping

Familiar imaging biomarkers used daily in cardiac imaging include LV ejection fraction, wall thickness, and left atrial size. New imaging biomarkers such as T1 mapping and ECV are typically first established as useful complementary tools for new biological insights before becoming surrogate secondary endpoints in clinical studies. They must then cross the “translational gap” before they can become clinical decision-making tools [103] (Fig. 4). Therefore, for T1 mapping and ECV, three parallel, not entirely sequential processes, are needed: technical validation (e.g., through the use of phantoms [103, 104]), biological/clinical validation, and cost-effectiveness analysis. We are still missing cost-effectiveness studies for T1 mapping and ECV—not every T1 mapping sequence will have commercial viability as a diagnostic product in healthcare systems, although some sequences certainly will. T1 mapping cost-effectiveness studies are needed to inform on this dichotomy. The funded research agendas of individual centers make it easier to carry on with adding layers of T1 mapping innovation rather than halt the advancement, and scrutinize old work for cost-effectiveness, that may well end up generating unwelcome results. Even those T1 mapping sequences found to lack commercial viability as products may still have niche roles in the research setting, justifying the development of new models to oversee their continued research and development funding, and regulation. Large-scale health-economic considerations and cost-effectiveness studies in T1 mapping, when they happen, will also need to consider the broader portfolio of competitor tests that include other CMR (e.g., LGE, T2 mapping) and non-CMR imaging biomarkers, as well as biospecimen-derived biomarkers (e.g., troponin, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, etc.) [105].

Fig. 4.

Overview of imaging biomarker roadmap for T1 mapping. The technical and early clinical validation of imaging biomarkers often occur in tandem. Cost-effectiveness and usability must be assessed for the biomarker to have the potential of full translational application. In parallel, prognostic assessment with hard outcomes must occur before routine integration into patient care

Furthermore, we need standardization and centrally coordinated accreditation systems for T1 mapping sites [105]. The issues of standardization and inter-operability is important for T1 mapping as measurements differ between CMR scanners, manufacturers, field strengths, protocols, pulse sequences [106], patient characteristics [107], and other factors. Depending on the sequence used, T1 mapping has specific limitations (see Table 1) that innovative approaches keep trying to address with encouraging results. Partial-volume effects at the interface between myocardium and blood-pool result in reduced accuracy and reproducibility [83, 108] and dark-blood preparation as well as systolic T1 mapping have been proposed as potential solutions to overcome these issues [108, 109]. Elaborate post-processing using improved modeling of the perturbed inversion curve has been studied to increase the accuracy of inversion-recovery-based T1 times [9, 110]. Saturation recovery methods were shown to improve the accuracy of T1 measurements compared to MOLLI, albeit at the expense of precision. Reconstructions with a reduced number of fit parameters have been proposed to trade off some of the precision loss against a slight drop in accuracy [83, 111]. Alternatively, SAPPHIRE can be employed, which through the use of a combined inversion/saturation recovery approach allows accurate T1 estimation without sacrificing as much of the precision as SASHA [107, 112]. Other efforts have addressed the RR-interval sensitivity of T1 mapping to improve its performance in the presence of arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation [113]. Free-breathing T1 mapping sequences are being proposed to overcome motion artifact in sicker patients unable to breath-hold [111] coupled with advances in motion-correction algorithms [20, 114]. Lastly, to increase imaging efficiency and improve specificity beyond conventional T1 mapping, several methods for joint estimation of parameters have recently been explored [115, 116].

Conclusion

T1 mapping and ECV of the heart are transforming contemporary CMR through their research and potential clinical applications. These biomarkers have potential to accurately inform clinical decision-making, but like all other biomarkers, they must first survive rigorous scrutiny, validation, and qualification. In spite of the research outputs and excitement within the CMR community, to date, although there has been a first consensus statement [18] with a second one pending, T1 mapping has yet to enter disease-specific guidelines (this may be pending for myocarditis). Still clinical utilization is proceeding with the use of these tools daily in many centers, so more is needed including a wider range of research (technical, translational, standardization) and further consensus/summary processes [117] to illuminate the T1 mapping field. Roadmapping these excellent biomarkers into healthcare for evidence-based patient management is an arduous, time-consuming, but important task. The CMR community needs such guidance.

Compliance with ethical standards

Funding information

G.C. is supported by the UK National Institute for Health Research Rare Diseases Translational Research Collaboration (NIHR RD-TRC, #171603) and by the 2017 Society of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Seed Grant Program. J.C.M. is supported by the NIHR University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre and the Biomedical Research Unit at Barts Hospital, respectively.

References

- 1.Sado DM, White SK, Piechnik SK, Banypersad SM, Treibel T, Captur G, Fontana M, Maestrini V, Flett AS, Robson MD, Lachmann RH, Murphy E, Mehta A, Hughes D, Neubauer S, Elliott PM, Moon JC. Identification and assessment of Anderson-Fabry disease by cardiovascular magnetic resonance noncontrast myocardial T1 mapping. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:392–398. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.000070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haaf P, Garg P, Messroghli DR, Broadbent DA, Greenwood JP, Plein S. Cardiac T1 mapping and extracellular volume (ECV) in clinical practice: a comprehensive review. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2016;18:89–101. doi: 10.1186/s12968-016-0308-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higgins DM, Moon JC. Review of T1 mapping methods: comparative effectiveness including reproducibility issues. Curr Cardiovasc Imaging Rep. 2014;7:9252. doi: 10.1007/s12410-013-9252-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fent GJ, Garg P, Foley JRJ, Swoboda PP, Dobson LE, Erhayiem B, Greenwood JP, Plein S, Treibel TA, Moon JC (2017) Synthetic myocardial extracellular volume fraction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. doi:10.1016/jcmg.2016.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Treibel TA, Fontana M, Maestrini V, Castelletti S, Rosmini S, Simpson J, Nasis A, Bhuva AN, Bulluck H, Abdel-Gadir A, White SK, Manisty C, Spottiswoode BS, Wong TC, Piechnik SK, Kellman P, Robson MD, Schelbert EB, Moon JC. Automatic measurement of the myocardial interstitium: synthetic extracellular volume quantification without hematocrit sampling. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Messroghli DR, Radjenovic A, Kozerke S, Higgins DM, Sivananthan MU, Ridgway JP. Modified look-locker inversion recovery (MOLLI) for high-resolution T1 mapping of the heart. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:141–146. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kellman P, Wilson JR, Xue H, Ugander M, Arai AE. Extracellular volume fraction mapping in the myocardium, part 1: evaluation of an automated method. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2012;14:63–74. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-14-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piechnik SK, Ferreira VM, Dall’Armellina E, Cochlin LE, Greiser A, Neubauer S, Robson MD. Shortened modified look-locker inversion recovery (ShMOLLI) for clinical myocardial T1-mapping at 1.5 and 3 T within a 9 heartbeat breathhold. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2010;12:69–80. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-12-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shao J, Rapacchi S, Nguyen K-L, Hu P. Myocardial T1 mapping at 3.0 tesla using an inversion recovery spoiled gradient echo readout and bloch equation simulation with slice profile correction (BLESSPC) T1 estimation algorithm. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;43:414–425. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gensler D, Morchel P, Fidler F, Ritter O, Quick HH, Ladd ME, Bauer WR, Ertl G, Jakob PM, Nordbeck P. Myocardial T1: quantification by using an ECG-triggered radial single-shot inversion-recovery MR imaging sequence. Radiology. 2015;274:879–887. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14131295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chow K, Flewitt JA, Green JD, Pagano JJ, Friedrich MG, Thompson RB. Saturation recovery single-shot acquisition (SASHA) for myocardial T(1) mapping. Magn Reson Med. 2014;71:2082–2095. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slavin GS, Stainsby JA. True T1 mapping with SMART1Map (saturation method using adaptive recovery times for cardiac T1 mapping): a comparison with MOLLI. J Cardiovasc Mag Res. 2013;15:P3. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-15-S1-P3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skulborstad EP, Borden ZS, Vigen KK, Slavin GS, Wang K, Schiebler ML, Nagle SK, Reeder SB, Grist TM, Francois CJ (2015) Myocardial T 1 Mapping Comparing SMART 1 Map and MOLLI: Clinical Experience at 3T. Abstract #2622 from ISMRM 23rd Annual Meeting

- 14.Weingärtner S, Akçakaya M, Basha T, Kissinger KV, Goddu B, Berg S, Manning WJ, Nezafat R. Combined saturation/inversion recovery sequences for improved evaluation of scar and diffuse fibrosis in patients with arrhythmia or heart rate variability. Magn Reson Med. 2013;71(3):1024–1103. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weingärtner S, Roujol S, Akçakaya M, Basha TA, Nezafat R. Free-breathing multislice native myocardial T1 mapping using the slice-interleaved T1 (STONE) sequence. Magn Reson Med. 2015;74:115–124. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehta BB, Chen X, Bilchick KC, Salerno M, Epstein FH. Accelerated and navigator-gated look-locker imaging for cardiac t1 estimation (ANGIE): development and application to T1 mapping of the right ventricle. Magn Reson Med. 2015;73:150–160. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Everett RJ, Stirrat CG, Semple SIR, Newby DE, Dweck MR, Mirsadraee S. Assessment of myocardial fibrosis with T1 mapping MRI. Clin Radiol. 2016;71:768–778. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moon JC, Messroghli DR, Kellman P, Piechnik SK, Robson MD, Ugander M, Gatehouse PD, Arai AE, Friedrich MG, Neubauer S, Schulz-Menger J, Schelbert EB. Myocardial T1 mapping and extracellular volume quantification: a Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (SCMR) and CMR Working Group of the European Society of Cardiology consensus statement. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2013;15:92–104. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-15-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roujol SS, Foppa M, Weingartner S, Manning WJ, Nezafat R, Weingärtner S, Manning WJ, Nezafat R. Adaptive registration of varying contrast-weighted images for improved tissue characterization (ARCTIC): application to T1 mapping. Magn Reson Med. 2014;73(4):1469–1482. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xue H, Shah S, Greiser A, Guetter C, Littmann A, Jolly MP, Arai AE, Zuehlsdorff S, Guehring J, Kellman P. Motion correction for myocardial T1 mapping using image registration with synthetic image estimation. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67:1644–1655. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kellman P, Herzka DA, Arai AE, Hansen MS. Influence of off-resonance in myocardial T1-mapping using SSFP based MOLLI method. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2013;15:63. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-15-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Look DC, Locker DR. Time saving in measurement of NMR and EPR relaxation times. Rev Sci Instrum. 1970;41:250–251. doi: 10.1063/1.1684482. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deichmann R, Haase A. Quantification of T1 values by SNAPSHOT-FLASH NMR imaging. J Magn Reson. 1992;96:608–612. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaptein R, Dijkstra K, Tarr C. A single-scan Fourier transform method for measuring spin-lattice relaxation times. J Magn Reson. 1976;24:295–300. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor AJ, Salerno M, Dharmakumar R, Jerosch-Herold M. T1 mapping: basic techniques and clinical applications. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:67–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higgins DM, Ridgway JP, Radjenovic A, Sivananthan UM, Smith MA. T1 measurement using a short acquisition period for quantitative cardiac applications. Med Phys. 2005;32:1738–1746. doi: 10.1118/1.1921668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sado DM, Flett AS, Banypersad SM, White SK, Maestrini V, Quarta G, Lachmann RH, Murphy E, Mehta A, Hughes DA, McKenna WJ, Taylor AM, Hausenloy DJ, Hawkins PN, Elliott PM, Moon JC. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance measurement of myocardial extracellular volume in health and disease. Heart. 2012;98:1436–1441. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chin CWL, Semple S, Malley T, White AC, Mirsadraee S, Weale PJ, Prasad S, Newby DE, Dweck MR. Optimization and comparison of myocardial T1 techniques at 3T in patients with aortic stenosis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;15:556–565. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jet245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Treibel TA, Fontana M, Reant P, Espinosa MA, Castelletti S, Herrey AS, Manisty C, Roberts N, Yap J, Moon J. T1 mapping in severe aortic stenosis: insights into LV remodeling. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2015;17:O89. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-17-S1-O89. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fontana M, Banypersad SM, Treibel TA, Maestrini V, Sado DM, White SK, Pica S, Castelletti S, Piechnik SK, Robson MD, Gilbertson JA, Rowczenio D, Hutt DF, Lachmann HJ, Wechaleka ADR, Whelan CJ, Gillmore JD, Hawkins PN, Moon JC. Native T1 mapping in transthyretin amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2014;7:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.aus dem Siepen F, Buss SJ, Messroghli D, Andre F, Lossnidzer D, Seitz S, Keller M, Schnabel PA, Giannitsis E, Korosoglou G, Katus H, Steen H. T1 mapping in dilated cardiomyopathy with cardiac magnetic resonance: quantification of diffuse myocardial fibrosis and comparison with endomyocardial biopsy. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16:210–216. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeu183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bulluck H, Rosmini S, Abdel-Gadir A, White SK, Bhuva AN, Treibel TA, Fontana M, Gonzalez-Lopez E, Reant P, Ramlall M, Hamarneh A, Sirker A, Herrey AS, Manisty C, Yellon DM, Kellman P, Moon JC, Hausenloy DJ (2016) Automated extracellular volume fraction mapping provides insights into the pathophysiology of left ventricular remodeling post-reperfused ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc 5:7. doi:10.1161/JAHA.116.003555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Pica S, Sado DM, Maestrini V, Fontana M, White SK, Treibel T, Captur G, Anderson S, Piechnik SK, Robson MD, Lachmann RH, Murphy E, Mehta E, Hughes D, Kellman P, Elliott PM, Herrey AS, Moon JC. Reproducibility of native myocardial T1 mapping in the assessment of Fabry disease and its role in early detection of cardiac involvement by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2014;16:99. doi: 10.1186/s12968-014-0099-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sado DM, Maestrini V, Piechnik SK, Banypersad SM, White SK, Flett AS, Robson MD, Neubauer S, Ariti C, Arai A, Kellman P, Yamamura J, Schoennagel BP, Shah F, Davis B, Trompeter S, Walker M, Porter J, Moon JC. Noncontrast myocardial T1 mapping using cardiovascular magnetic resonance for iron overload. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;41:1505–1511. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hinojar R, Foote L, Arroyo Ucar E, Jackson T, Jabbour A, Yu CY, McCrohon J, Higgins DM, Carr-White G, Mayr M, Nagel E, Puntmann VO. Native T1 in discrimination of acute and convalescent stages in patients with clinical diagnosis of myocarditis: a proposed diagnostic algorithm using CMR. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2015;8:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kidambi A, Motwani M, Uddin A, Ripley DP, McDiarmid AK, Swoboda PP, Broadbent DA, Musa TA, Erhayiem B, Leader J, Croisille P, Clarysse P, Greenwood JP, Plein S (2016) Myocardial extracellular volume estimation by CMR predicts functional recovery following acute MI. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Singh A, Horsfield MA, Bekele S, Khan JN, Greiser A, McCann GP. Myocardial T1 and extracellular volume fraction measurement in asymptomatic patients with aortic stenosis: reproducibility and comparison with age-matched controls. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16:763–770. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jev007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swoboda PP, McDiarmid AK, Erhayiem B, Law GR, Garg P, Broadbent DA, Ripley DP, Musa TA, Dobson LE, Foley JR, Fent GJ, Page SP, Greenwood JP, Plein S (2017) Effect of cellular and extracellular pathology assessed by T1 mapping on regional contractile function in hypert rophic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 19(1):16. doi:10.1186/s12968-017-0334-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Su MY, Lin LY, Tseng YH, Chang CC, Wu CK, Lin JL, Tseng WY (2014) CMR-verified diffuse myocardial fibrosis is associated with diastolic dysfunction in HFpEF. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 7(10):991–7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.McDiarmid AK, Swoboda PP, Erhayiem B, Lancaster RE, Lyall GK, Broadbent DA, Dobson LE, Musa TA, Ripley DP, Garg P, Greenwood JP, Ferguson C, Plein S. Athletic cardiac adaptation in males is a consequence of elevated myocyte mass. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:e003579. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.115.003579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thompson RB, Chow K, Khan A, Chan A, Shanks M, Paterson I, Oudit GY. T(1) mapping with cardiovascular MRI is highly sensitive for Fabry disease independent of hypertrophy and sex. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:637–645. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.000482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hanneman K, Nguyen ET, Thavendiranathan P, Ward R, Greiser A, Jolly MP, Butany J, Yang IY, Sussman MS, Wintersperger BJ. Quantification of myocardial extracellular volume fraction with cardiac MR imaging in thalassemia major. Radiology. 2016;279:720–730. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015150341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fontana M, Chung R, Hawkins PN, Moon JC. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance for amyloidosis. Heart Fail Rev. 2015;20:133–144. doi: 10.1007/s10741-014-9470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fontana M, Banypersad SM, Treibel TA, Abdel-Gadir A, Maestrini V, Lane T, Gilbertson JA, Hutt DF, Lachmann HJ, Whelan CJ, Wechalekar AD, Herrey AS, Gilmore JD, Hawkins PN, Moon JC. Differential myocyte responses in patients with cardiac transthyretin amyloidosis and light-chain amyloidosis: a cardiac MR imaging study. Radiology. 2015;277:388–397. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015141744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bohnen S, Radunski UK, Lund GK, Ojeda F, Looft Y, Senel M, Radziwolek L, Avanesov M, Tahir E, Stehning C, Schnackenburg B, Adam G, Blankenberg S, Muellerleile K (2017) Tissue characterization by T1 and T2 mapping cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging to monitor myocardial inflammation in healing myocarditis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. doi:10.1093/ehjci/jex007 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Banypersad SM, Sado DM, Flett AS, Gibbs SD, Pinney JH, Maestrini V, Cox AT, Fontana M, Whelan CJ, Wechalekar AD, Hawkins PN, Moon JC. Quantification of myocardial extracellular volume fraction in systemic AL amyloidosis: an equilibrium contrast cardiovascular magnetic resonance study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:34–39. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.978627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lurz JA, Luecke C, Lang D, Besler C, Rommel KP, Klingel K, Kandolf R, Adams V, Schöne K, Hindricks G, Schuler G, Linke A, Thiele H, Gutberlet M, Lurz P (2017) CMR-derived extracellular volume fraction as a marker for myocardial fibrosis: the importance of coexisting myocardial inflammation. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Urbieta-Caceres VH, Zhu X-Y, Gibson ME, Favreau FD, Jordan K, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Reversal of experimental renovascular hypertension restores coronary microvascular function and architecture. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24:458–465. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Putko BN, Wen K, Thompson RB, Mullen J, Shanks M, Yogasundaram H, Sergi C, Oudit GY. Anderson-Fabry cardiomyopathy: prevalence, pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Heart Fail Rev. 2015;20:179–191. doi: 10.1007/s10741-014-9452-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kozor R, Grieve SM, Tchan MC, Callaghan F, Hamilton-Craig C, Denaro C, Moon JC, Figtree GA. Cardiac involvement in genotype-positive Fabry disease patients assessed by cardiovascular MR. Heart. 2016;102:298–302. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sado DM, White SK, Piechnik SK, Banypersad SM, Treibel T, Captur G, Fontana M, Maestrini V, Flett AS, Robson MD, Lachmann RH, Murphy E, Mehta E, Hughes D, Neubauer S, Elliott PM, Moon JC. Identification and assessment of Anderson-Fabry disease by cardiovascular magnetic resonance noncontrast myocardial T1 mapping. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:392–398. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.000070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nordin S, Kozor R, Bulluck H, Castelletti S, Rosmini S, Abdel-Gadir A, Baig S, Mehta A, Hughes D, Moon JC. Cardiac fabry disease with late gadolinium enhancement is a chronic inflammatory cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:1707–1708. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.07.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moon JCC, Sachdev B, Elkington AG, McKenna WJ, Mehta A, Pennell DJ, Leed PJ, Elliott PM. Gadolinium enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance in Anderson-Fabry disease. Evidence for a disease specific abnormality of the myocardial interstitium. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:2151–2155. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Friedrich MG, Sechtem U, Schulz-Menger J, Holmvang G, Alakija P, Cooper LT, White JA, Abdel-Aty H, Gutberlet M, Prasad S, Aletras A, Laissy JP, Paterson I, Filipchuk NG, Kumar A, Pauschinger M, Liu P. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in myocarditis: a JACC White Paper. JAC. 2009;53:1475–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Francone M, Chimenti C, Galea N, Scopelliti F, Verardo R, Galea R, Carbone I, Catalano C, Fedale F, Frustaci A. CMR sensitivity varies with clinical presentation and extent of cell necrosis in biopsy-proven acute myocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2014;7:254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nadjiri J, Nieberler H, Hendrich E, Greiser A, Will A, Martinoff S, Hadamitzky M. Performance of native and contrast-enhanced T1 mapping to detect myocardial damage in patients with suspected myocarditis: a head-to-head comparison of different cardiovascular magnetic resonance techniques. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;33:539–547. doi: 10.1007/s10554-016-1029-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luetkens JA, Homsi R, Sprinkart AM, Doerner J, Dabir D, Kuetting DL, Block W, Andrie R, Stehning C, Fimmers R, Gieseke J, Thomas DK, Schild HH, Naehle CP. Incremental value of quantitative CMR including parametric mapping for the diagnosis of acute myocarditis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;17:154–161. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jev246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lurz P, Luecke C, Eitel I, Föhrenbach F, Frank C, Grothoff M, de Waha S, Rommel KP, Lurz JA, Klingel K, Kandolf R, Schuler G, Thiele H, Gutberlet M. Comprehensive cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in patients with suspected myocarditis: the MyoRacer-Trial. JAC. 2016;67:1800–1811. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lagan J, Schmitt M, Miller CA (2017) Clinical applications of multi-parametric CMR in myocarditis and systemic inflammatory diseases. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. doi:10.1007/s10554-017-1063-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Carrick D, Haig C, Rauhalammi S, Ahmed N, Mordi I, McEntegart M, Petrie MC, Eteiba H, Hood S, Watkins S, Lindsay M, Mahrous A, Ford I, Tzemos N, Sattar N, Welsh P, Radjenovic A, Oldroyd KG, Berry C. Prognostic significance of infarct core pathology revealed by quantitative non-contrast in comparison with contrast cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in reperfused ST-elevation myocardial infarction survivors. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:1044–1059. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nakamori S, Alakbarli J, Bellm S, Motiwala SR, Addae G, Manning WJ, Nezafat R (2017) Native T1 value in the remote myocardium is independently associated with left ventricular dysfunction in patients with prior myocardial infarction. J Magn Reson Imaging. doi:10.1002/jmri.25652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Chen YY, Ren DY, Zeng MS, Yang S, Yun H, Fu CX, Ge JB, Jin H, Qian JY, Zhang WG. Myocardial extracellular volume fraction measurement in chronic total coronary occlusion: association with myocardial injury, angiographic collateral flow, and functional recovery. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;44:972–982. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dall'Armellina E, Piechnik SK, Ferreira VM, Si QL, Robson MD, Francis JM, Cuculi F, Kharbanda RK, Banninq AP, Choudhury RP, Karamitsos TD, Neubauer S. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance by non contrast T1-mapping allows assessment of severity of injury in acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2012;14:15–28. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-14-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ugander M, Bagi PS, Oki AJ, Chen B, Hsu LY, Aletras AH, Shah S, Greiser A, Kellman P, Arai AE. Myocardial edema as detected by pre-contrast T1 and T2 CMR delineates area at risk associated with acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2012;5:596–603. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kellman P, Bandettini WP, Mancini C, Hammer-Hansen S, Hansen MS, Arai AE. Characterization of myocardial T1-mapping bias caused by intramyocardial fat in inversion recovery and saturation recovery techniques. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2015;17:33. doi: 10.1186/s12968-015-0136-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu A, Wijesurendra RS, Ariga R, Mahmod M, Levelt E, Greiser A, Petrou M, Krasopoulos G, Forfar JC, Kharbanda RK, Channon KM, Neubauer S, Piechnik SK, Ferreira VM. Splenic T1-mapping: a novel quantitative method for assessing adenosine stress adequacy for cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2017;19:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12968-016-0318-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Manisty C, Ripley DP, Herrey AS, Captur G, Wong TC, Petersen SE, Plein S, Peebles C, Schelbert EB, Greenwood JP, Moon JC. Splenic switch-off: a tool to assess stress adequacy in adenosine perfusion cardiac MR imaging. Radiology. 2015;276(3):732–740. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015142059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rapezzi C, Merlini G, Quarta CC, Riva L, Longhi S, Leone O, Salvi F, Ciliberti P, Pastorelli F, Biagini E, Coccolo F, Cooke RM, Bacchi-Reggiani L, Sangiorgi D, Ferlini A, Cavo M, Zamagni E, Fonte ML, Palladini G, Salinaro F, Musca F, Obici L, Branzi A, Perlini S. Systemic cardiac amyloidoses: disease profiles and clinical courses of the 3 main types. Circulation. 2009;120:1203–1212. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.843334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Syed IS, Glockner JF, Feng D, Araoz PA, Martinez MW, Edwards WD, Gertz MA, Dispenzieri A, Oh JK, Bellavia D, Tajik AJ, Grogan M. Role of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in the detection of cardiac amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2010;3:155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Karamitsos TD, Piechnik SK, Banypersad SM, Fontana M, Ntusi NB, Ferreira VM, Whelan CJ, Myerson SG, Robson MD, Hawkins PN, Neubauer S, Moon JC. Noncontrast T1 mapping for the diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2013;6:488–497. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ruberg FL. T1 mapping in cardiac amyloidosis: can we get there from here? J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2013;6:498–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dungu JN, Valencia O, Pinney JH, Gibbs SDJ, Rowczenio D, Gilbertson JA, Lachmann HJ, Wechalekar A, Gillmore JD, Whelan CJ, Hawkins PN, Anderson LJ. CMR-based differentiation of AL and ATTR cardiac amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2014;7:133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wood JC, Otto-Duessel M, Aguilar M, Nick H, Nelson MD, Coates TD, Pollack H, Moats R. Cardiac iron determines cardiac T2*, T2, and T1 in the gerbil model of iron cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2005;112:535–543. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.504415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.de Meester de Ravenstein C, Bouzin C, Lazam S, Boulif J, Amzulescu M, Melchior J, Pasquet A, Vancreaynest D, Pouleur AC, Vanoverschelde JLJ, Gerber BL. Histological validation of measurement of diffuse interstitial myocardial fibrosis by myocardial extravascular volume fraction from modified look-locker imaging (MOLLI) T1 mapping at 3 T. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2015;17:48–59. doi: 10.1186/s12968-015-0150-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pennell DJ, Udelson JE, Arai AE, Bozkurt B, Cohen AR, Galanello R, Hoffman TM, Kiernan MS, Lerakis S, Piga A, Porter JB, Walker JM, Wood J. Cardiovascular function and treatment in β-thalassemia major: a consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;128:281–308. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829b2be6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Torlasco C, Cassinerio E, Pedrotti P, Faini A, Capecchi M, Abdel-Gadir A, Parati G. Role of T1 mapping as a complementary tool to T2* for non-invasive cardiac iron overload assessment. In: BMJ publishing group Proceedings 24th great wall international congress of cardiology/Asia pacific heart congress/international congress of cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation. Beijing, pp A6–A6. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2017-311399.6

- 77.Feng Y, He T, Carpenter JP, Jabbour A, Alam M, Gatehouse PD, Greiser A, Messorgli D, Firmin DN, Pennell DJ (2013) In vivo comparison of myocardial T1 with T2 and T2* in thalassaemia major. J Magn Reson Imaging 38:588–593. doi:10.1002/jmri.24010 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 78.Alam MH, Auger D, Smith GC, He T, Vassiliou V, Baksi AJ, Wage R, Drivas P, Feng Y, Firmin DN, Pannell DJ. T1 at 1.5T and 3T compared with conventional T2* at 1.5T for cardiac siderosis. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2015;17:102–113. doi: 10.1186/s12968-015-0207-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Camargo GC, Rothstein T, Junqueira FP, Fernandes E, Greiser A, Strecker R, Pessoa V, Lima RS, Gottlieb I. Comparison of myocardial T1 and T2 values in 3 T with T2* in 1.5 T in patients with iron overload and controls. Int J Hematol. 2016;103:530–536. doi: 10.1007/s12185-016-1950-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kirk P, Smith GC, Roughton M, He T, Pennell DJ. Myocardial T2* is not affected by ageing, myocardial fibrosis, or impaired left ventricular function. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;32:1095–1098. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Carpenter J-P, Prasad SK, Pennell DJ. Myocardial fibrosis in thalassaemia: recalling the past or telling the future? Heart. 2009;95:1646–1647. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.166587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lehrke S, Lossnitzer D, Schöb M, Steen M, Merten C, Kemmling H, Pribe R, Ehlermann P, Zuqck C, Korosoglou G, Giannitsis E, Katus HA. Use of cardiovascular magnetic resonance for risk stratification in chronic heart failure: prognostic value of late gadolinium enhancement in patients with non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2011;97:727–732. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.205542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kellman P, Hansen MS. T1-mapping in the heart: accuracy and precision. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2014;16:2–22. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-16-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dass S, Suttie JJ, Piechnik SK, Ferreira VM, Holloway CJ, Banerjee R, Mahmod M, Cochlin L, Karamitsos TD, Robson MD, Watkins H, Neubauer S. Myocardial tissue characterization using magnetic resonance noncontrast t1 mapping in hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:726–733. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.976738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Puntmann VO, Voigt T, Chen Z, Mayr M, Karim R, Rhode K, Pastor A, Carr-White G, Razavi R, Schaeffter T, Nagel E. Native T1 mapping in differentiation of normal myocardium from diffuse disease in hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2013;6:475–484. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Barison A, Del Torto A, Chiappino S, Aquaro GD, Todiere G, Verqaro G, Passino C, Lombardi M, Emdin M, Masci PG. Prognostic significance of myocardial extracellular volume fraction in nonischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2015;16:681–687. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hong YJ, Park CH, Kim YJ, Hur J, Lee HJ, Hong SR, Suh YJ, Greiser A, Paek MY, Choi BW, Kim TH. Extracellular volume fraction in dilated cardiomyopathy patients without obvious late gadolinium enhancement: comparison with healthy control subjects. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;31(Suppl 1):115–122. doi: 10.1007/s10554-015-0595-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sanz J. T1 maps in nonischemic DCM: do they show us the way? J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2016;9:51–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nishii T, Kono AK, Shigeru M, Takamine S, Fujiwara S, Kyotani K, Aoyama N, Sugimura K. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance T2 mapping can detect myocardial edema in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;30(Suppl 1):65–72. doi: 10.1007/s10554-014-0414-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kamal MU, Riaz IB, Janardhanan R. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: current state of the art. Cardiol J. 2016;23:250–263. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2016.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lu M, Zhao S, Yin G, Jiang S, Zhao T, Chen X, Tian L, Zhang Y, Wei Y, Liu Q, He Z, Xue H, An J, Shah S. T1 mapping for detection of left ventricular myocardial fibrosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a preliminary study. Eur J Radiol. 2013;82:e225–e231. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hinojar R, Varma N, Child N, Goodman B, Jabbour A, Yu CY, Gebker R, Doltra A, Kelle S, Khan S, Rogers T, Arroyo Ucar E, Cummins C, Carr-White G, Nagel E, Puntmann VO. T1 mapping in discrimination of hypertrophic phenotypes: hypertensive heart disease and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: findings from the international T1 multicenter cardiovascular magnetic resonance study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8 doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.115.003285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lima JAC. The promise of myocardial fibrosis assessment by T1 mapping. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2013;6:485–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Swoboda PP, McDiarmid AK, Erhayiem B, Broadbent DA, Dobson LE, Garg P, Ferguson C, Page SP, Greenwood JP, Plein S. Assessing myocardial extracellular volume by T1 mapping to distinguish hypertrophic cardiomyopathy from athlete’s heart. JAC. 2016;67:2189–2190. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Badiani S, van Zalen J, Treibel TA, Bhattacharyya S, Moon JC, Lloyd G. Aortic stenosis, a left ventricular disease: insights from advanced imaging. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2016;18:80. doi: 10.1007/s11886-016-0753-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Flett AS, Sado DM, Quarta G, Mirabel M, Pellerin D, Herrey AS, Hausenlov DJ, Ariti C, Yap J, Kolvekar S, Taylor AM, Moon JC. Diffuse myocardial fibrosis in severe aortic stenosis: an equilibrium contrast cardiovascular magnetic resonance study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;13:819–826. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jes102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bull S, White SK, Piechnik SK, Flett AS, Ferreira VM, Loudon M, Francis JM, Karamitsos TD, Prenderqast BD, Robson MD, Neubauer S, Moon JC, Myerson SG. Human non-contrast T1 values and correlation with histology in diffuse fibrosis. Heart. 2013;99:932–937. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-303052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Weidemann F, Herrmann S, Stork S, Niemann M, Frantz S, Lange V, Beer M, Gattenlohner S, Voelker W, Ertl G, Strotmann JM. Impact of myocardial fibrosis in patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2009;120:577–584. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.847772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chin CWL, Messika-Zeitoun D, Shah ASV, Lefevre G, Bailleul S, Yeung ENW, Koo M, Mirsadraee S, Mathieu T, Semple SI, Mills NL, Vahanian A, Newby DE, Dweck MR. A clinical risk score of myocardial fibrosis predicts adverse outcomes in aortic stenosis. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:713–723. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nadjiri J, Nieberler H, Hendrich E, Will A, Pellegrini C, Husser O, Hengstenberg C, Greiser A, Martinoff S, Hadamitzky M. Prognostic value of T1-mapping in TAVR patients: extra-cellular volume as a possible predictor for peri- and post-TAVR adverse events. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;32:1625–1633. doi: 10.1007/s10554-016-0948-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chin CWL, Everett RJ, Kwiecinski J, Vesey AT, Yeung E, Esson G, Jenkins W, Koo M, Mirsadraee S, White AC (2016) Myocardial fibrosis and cardiac decompensation in aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 102.Edwards NC, Moody WE, Yuan M, Weale P, Neal D, Townend JN, Steeds RP. Quantification of left ventricular interstitial fibrosis in asymptomatic chronic primary degenerative mitral regurgitation. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7:946–953. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.114.002397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Captur G, Gatehouse P, Keenan KE, Heslinga FG, Bruehl R, Prothmann M, Graves MJ, Eames RJ, Torlasco C, Benedetti G, Donovan J, Ittermann B, Boubertakh R, Bathgate A, Royet C, Pang W, Nezafat R, Salerno M, Kellman P, Moon JC. A medical device-grade T1 and ECV phantom for global T1 mapping quality assurance—the T1 mapping and ECV standardization in CMR (T1MES) program. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2016;18(1):58–78. doi: 10.1186/s12968-016-0280-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Vassiliou V, Heng E, Donovan J, Greiser A, Babu-Narayan SV, Gatzoulis MA, Firmin D, Pennell DJ, Gatehouse P, Prasad SK. Longitudinal stability of gel T1 MRI phantoms for quality assurance of T1 mapping. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2015;17(Suppl 1):W28–W31. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-17-S1-W28. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Captur G, Manisty C, Moon JC. Cardiac MRI evaluation of myocardial disease. Heart. 2016;102:1429–1435. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-309077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.O’Connor JPB, Aboagye EO, Adams JE, Aerts HJWL, Barrington SF, Beer AJ, Boellaard R, Bohndiek SE, Brady M, Brown G, Buckley DL, Chenevert TL, Clarke LP, Collette S, Cook GJ, deSouza NM, Dickson JC, Dive C, Evelhoch JL, Faivre-Finn C, Gallagher FA, Gilbert FJ, Gillies RJ, Goh V, Griffiths JR, Groves AM, Halligan S, Harris AL, Hawkes DJ, Hoekstra OS, Huang EP, Hutton BF, Jackson EF, Jayson GC, Jones A, Koh D-M, Lacombe D, Lambin P, Lassau N, Leach MO, Lee T-Y, Leen EL, Lewis JS, Liu Y, Lythgoe MF, Manoharan P, Maxwell RJ, Miles KA, Morgan B, Morris S, Ng T, Padhani AR, Parker GJM, Partridge M, Pathak AP, Peet AC, Punwani S, Reynolds AR, Robinson SP, Shankar LK, Sharma RA, Soloviev D, Stroobants S, Sullivan DC, Taylor SA, Tofts PS, Tozer GM, van Herk M, Walker-Samuel S, Wason J, Williams KJ, Workman P, Yankeelov TE, Brindle KM, McShane LM, Jackson A, Waterton JC. Imaging biomarker roadmap for cancer studies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol advance on. 2016;14(3):169–186. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Roujol S, Weingärtner S, Foppa M, Chow K, Kawaji K, Ngo LH, Kellman P, Manning WJ, Thompson RB, Nezafat R. Accuracy, precision, and reproducibility of four T1 mapping sequences: a head-to-head comparison of MOLLI, ShMOLLI, SASHA, and SAPPHIRE. Radiology. 2014;272:683–689. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14140296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Weingärtner S, Meßner NM, Zöllner FG, Akçakaya M, Schad LR (2016) Black-blood native T1 mapping: blood signal suppression for reduced partial voluming in the myocardium. Magn Reson Med. doi:10.1002/mrm.26378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 109.Ferreira VM, Wijesurendra RS, Liu A, Greiser A, Casadei B, Robson MD, Neubauer S, Piechnik SK. Systolic ShMOLLI myocardial T1-mapping for improved robustness to partial-volume effects and applications in tachyarrhythmias. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2015;17:77. doi: 10.1186/s12968-015-0182-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sussman MS, Yang IY, Fok K-H, Wintersperger BJ. Inversion group (IG) fitting: a new T1 mapping method for modified look-locker inversion recovery (MOLLI) that allows arbitrary inversion groupings and rest periods (including no rest period) Magn Reson Med. 2016;75:2332–2340. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chow K, Yang Y, Shaw P, Kramer CM, Salerno M. Robust free-breathing SASHA T1 mapping with high-contrast image registration. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2016;18(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s12968-016-0267-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Weingärtner S, Akçakaya M, Basha T, Kissinger KV, Goddu B, Berg S, Manning WJ, Nezafat R. Combined saturation/inversion recovery sequences for improved evaluation of scar and diffuse fibrosis in patients with arrhythmia or heart rate variability. Magn Reson Med. 2014;71:1024–1034. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhao L, Li S, Ma X, Greiser A, Zhang T, An J, Bai R, Dong J, Fan Z. Systolic MOLLI T1 mapping with heart-rate-dependent pulse sequence sampling scheme is feasible in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2016;18:13. doi: 10.1186/s12968-016-0232-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]