Abstract

Flying foxes, the genus Pteropus, are considered viral reservoirs. Their colonial nature and long flight capability enhance their ability to spread viruses quickly. To understand how the viral transmission occurs between flying foxes and other animals, we investigated daytime behavior of the large flying fox (Pteropus vampyrus) in the Leuweung Sancang conservation area, Indonesia, by using instantaneous scan sampling and all-occurrence focal sampling. The data were obtained from 0700 to 1700 hr, during May 11–25, 2016. Almost half of the flying foxes (46.9 ± 10.6% of all recorded bats) were awake and showed various levels of activity during daytime. The potential behaviors driving disease transmission, such as self-grooming, mating/courtship and aggression, peaked in the early morning. Males were more active and spent more time on sexual activities than females. There was no significant difference in time spent for negative social behaviors between sexes. Positive social behaviors, especially maternal cares, were performed only by females. Sexual activities and negative/positive social behaviors enable fluid exchange between bats and thus facilitate intraspecies transmission. Conflicts for living space between the flying foxes and the ebony leaf monkey (Trachypithecus auratus) were observed, and this caused daily roosting shifts of flying foxes. The ecological interactions between bats and other wildlife increase the risk of interspecies infection. This study provides the details of the flying fox’s behavior and its interaction with other wildlife in South-East Asia that may help explain how pathogen spillover occurs in the wild.

Keywords: all-occurrence focal sampling, daytime behavior, disease transmission, instantaneous scan sampling, Pteropus vampyrus

The bats of the genus Pteropus (commonly known as the flying fox) are the largest fruit bats that congregate in a large colonies numbering in the thousands or ten thousand in tropical, subtropical and temperate regions, in Asia, Australia, and islands in Indian Ocean and western Pacific Ocean [3]. Flying foxes are believed to navigate using vision and olfactory senses, and they play an important role in keeping native forests healthy, through dispersing seeds and pollinating [10, 29]. However, flying foxes are well-recognized reservoirs of zoonotic viruses, as they host a large number of viruses covering 15 viral families [22]. In addition, they possess special characteristics, such as long distance flight ability, occupation of large geographic ranges, colonial nature and long life, which facilitate the virus spillover from bats into other animals, including humans [4]. The expansion of agricultural and urban areas should lead to an increase in living proximity of humans and domestic animals to flying foxes. For example, in Queensland, Australia, the habitat ranges of flying foxes have been overlapped with that of equines. This enhances the risk of cross-species transmission through the presence of infectious materials, such as urine and feces, in foraging areas utilized by both animals [9].

The habitat overlapping of humans and flying foxes has raised concerns for public health, since the first human case of lyssavirus infection in Australia was detected. This infection occurred by direct contact between human and flying foxes [1]. In 2013–2014, an Ebola virus outbreak in humans resulted in more than 20,000 human victims. The first report of Ebola virus (EBOV) outbreak in human was in 1976 [34]. In 2005, the evidence of asymptomatic EBOV-infection was found in fruit bats, belonging to the family Pteropodidae: Epomops franqueti, Hypsignathus monstrosus and Myonycteris torquata [20]. Therefore, these three fruit-bat species are believed to be a reservoir of Ebola virus. Great apes, such as gorillas and chimpanzees, are believed to be an intermediate host for this virus [13]. Nipah virus, a novel paramyxovirus, was reported for its first outbreak at Malaysia in 1998, causing a severe respiratory disease with high mortality rate in humans and pigs [5]. The virus was detected and isolated from three species of flying foxes; P. hypomelanus, P. vampyrus and P. lylei [4]. Furthermore, the previous study discovered that Nipah virus circulated in the population of P. vampyrus in Indonesia [41]. This raised up the awareness of Nipah virus outbreaks in this region, because this flying fox species have a high potential to spread the virus in large area through their night flight activity. However, the potential daytime behaviors circulating the viruses within bat populations and ecological interactions between the infected bat and recipients are still unknown. To improve the understanding of these processes, daytime behavioral observation in the large flying foxes is required.

To gain new insights into host-recipient interactions, the daytime behavior of Pteropus vampyrus (the large flying fox) and its interactions with wildlife living around the roosting site of the flying foxes were investigated in a natural habitat at Leuweung Sancang conservation area, Indonesia. This study site is considered to be a good model as a hotspot to monitor zoonotic disease, since it contains many species of animals, such as the crested serpent eagle (Spilornis cheela), wild boar (Sus scrofa), long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis) and the endemic species-ebony leaf monkey (Trachypithecus auratus) [12, 28]. The understanding of the complex social relationships in roosting bats or between bats and other wildlife will provide evidence to speculate how an emerging infectious disease appears in humans and wildlife populations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study site

The present study was conducted at the Leuweung Sancang natural conservation area, West Java Island, Indonesia (7° 43′ 45.12′′ S, 107° 54′ 10.08′′ E) (Fig. 1). This region is a part of the tropical rain forest, spanning across 2,157 hectares of land [38]. We chose this conservation area, since the wildlife remains relatively intact in Java Island, where allocated forests cover 12.74% of the land [42]. The dominant plants occupying this area belong to the Family Dipterocarpaceae [43]. This conserved area is the natural habitat of P. vampyrus (the large flying fox) and many other wildlife species, including the endemic species T. auratus (ebony leaf monkey) [28]. In addition, fisherman’s village is located along beachside of the conserved area, where local peoples stay nearby two observed roosting sites of the flying foxes (approximately 846 m from roosting site 1 and 451 m from roosting site 2) (see Fig. 1). Therefore, it is a human-wildlife-flying foxes interface area that is fit for the study of inter-species interaction. Three species of roosting trees in these two roosting sites were identified by the Faculty of Forestry, Bogor Agricultural University. These are Artocarpus elasticus, Nauclea orientalis and Glochidion rubrum. A preliminary survey was carried out to determine the location of the flying fox’s roosting sites and the optimal time for observation. A direct count of the population size of the flying fox in the study site was not available due to dense canopy cover. This study received approval from the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, the Office of West Java province and Garut city, Indonesia.

Fig. 1.

The map shows the location of Leuweung Sancang conservation area (7° 43′ 45.12′′ S, 107° 54′ 10.08′′ E), in West Java Island, Indonesia. The conserved area consists of fisherman village and two roosting sites of the large flying foxes. The roosting site 1 located at 7° 43′ 51.60′ S, 107° 50′ 59.30′′ E, and the roosting site 2 located at 7° 43′ 24.50′′ S, 107° 50′ 20.00′′ E. The distance between these roosting sites is approximately 1.48 km.

Instantaneous scan sampling technique

The observations of the daytime behavior of the flying fox were conducted by 3 observers during May 11–25, 2016. To investigate the diurnal variation in activities of the flying fox, one observer conducted instantaneous scan sampling, in which the behaviors of group were rapidly scanned at regular intervals [2]. The difficulty to access the study site; therefore, observations started after the arrival of observers around 0700 hr to 1700 hr. As it is impossible to observe behaviors of all individuals in the group, due to its large population, the observer randomly selected a subgroup (containing 50 bats) using the acetate sheet method. A clear acetate sheet was divided into squares by gridline, and each square was addressed by numbers. The sheet was placed on the monitor screen of the camera which was tracking a group of the flying foxes. Using two random numbers, the subgroup closest to the center of a chosen square was selected. In case that the flying foxes moved to another roosting site in deeper forest with dense canopy covers, our ability to see a group of the flying foxes could be limited. Therefore, we needed to choose a visible subject group containing at least 30 adults of both sexes. Each one-hour recording session was divided into 15-min sampling intervals, giving 4 sampling points per one-hour recording session. At each sampling point, the behavior of all individuals in the subject group was recorded one by one. By this technique, we obtained the data from totally of 800 individuals for the whole observation periods. All recorded behaviors were classified according to the behavioral units described in Table 1. To minimize the effects of observers, the observers kept enough distance, approximately 15–20 m from the roosting trees, so as not to disturb the behavior of the flying foxes. Environmental measurements of ambient temperature, humidity, light intensity and wind speed, were taken at 2.5 m, above the ground in order to find the relationship between the environmental factors and behavioral patterns.

Table 1. The daytime behaviors of P. vampyrus at the roosting site.

| Behavioral category | Behavioral unit | Description | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual activities | Mating | Male grasp-restraint female from behind, biting female’s neck and insert the penis into the vagina | Reproduction |

| Courtship | Male approaches female and licks at genital area of female | Reproduction | |

| Masturbation | Male start licking at its penis, leading to erection and continuously licks the erect penis for more than one min, without urination and ejaculation | Serves as masturbatory function, mostly found when male was rejected for mating by female | |

| Self-maintenance | Self-grooming | Licking wing membrane or occasional bouts of penile licking or scratching body including head | Cleaning function or wing membrane maintenance |

| Thermoregulation | Wing flapping | Fanning body with wing membrane | Reducing body temperature |

| Positive social behavior | Maternal care | Newborn attached or being carried by female or juvenile grooming by female | Mostly found during lactation period, establish social bond between mother and offspring |

| Mutual grooming | Licking on another one’s body, excluding the licking of juvenile by its mother or rubbing the neck and head along those of the other | Associated with group recognition, bonding within the group | |

| Play | Mock biting or mock wrestling by an absence of vocalization | Usually occur among young males | |

| Negative social behavior | Aggression | Aggressive vocalization, wing shaking, chasing, biting and/or fighting between individuals | Defense of territory by males or self-defense by male and female |

| Wing spreading | Wings widely opened and extended | Related to the defense for territories or making threat displays to others, mostly performed by males | |

| Non-categorized | Sleeping | Eyes closed and wing wrapped around body | |

| Hang relax | Hanging bipedally or monopedally with wings folded or wings opened and eyes open looking around | ||

| Hang alert | Hanging bipedally or monopedally with eyes open and ear movement around | ||

| Movement | Moving along branch or trunk without flying | ||

| Excretion | Turn the body upright to urinate and/or defecate | ||

These behavioral units were described according to its postures and were grouped into behavioral categories according to its function, referring to Connell et al. (2006), Nelson (1965) and Markus and Blackshaw (2002).

All-occurrence focal sampling

To compare the diurnal activity budgets; the proportions of time spent to different behavioral categories between adult male and adult female bats, another two observers performed all-occurrence focal sampling parallel with the period of instantaneous scan sampling. All-occurrence focal sampling is the technique in which one individual is observed for all observation sessions [25]. The focal subjects were randomly chosen by acetate sheet method as described above. In this study, we gathered data from 5 males and 5 females. Each focal subject was observed through all recording sessions (totally 7 hr in a day). The flying foxes living in the wild have some naturally distinctive markings, because of injuries. These features, such as damaged ears, scars or holes on wing membranes, enabled the experienced observers to distinguish the subjects from another. In each one-hour recording session (which was stopped for 30 min between each session), all behaviors of the focal bats were recorded with information about the time of occurrence; the length of time (in seconds) for which a single behavior lasts. The recorded behaviors were characterized according to behavioral units, divided into 5 behavioral categories (Table 1). Some behavioral units could be considered as the solitary behavior, if that behavior is performed by a single animal without interaction with another individual, such as sleeping, self-grooming, wing flapping, wing spreading, hanging relax and excretion. The social behavior was defined as the behavior involved by two or more animals, such as mutual grooming, maternal care, mating/courtship, aggression and hanging alert [23]. In the case that the subject went out of sight, a new focal subject was randomly chosen immediately. In addition, the interaction or the action of flying foxes and other wildlife that has effect on one another was noted, as the data for assessment of the risk of disease transmission across animal species.

Statistical analysis

For instantaneous scan sampling, the raw data were initially tested to determine, if they showed the normal distribution by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test. The result indicated that the data sets were not normally distributed. Thus, non-parametric statistics were used for this behavioral analysis. The number of bats with each behavioral unit was grouped into one-hour blocks and was analyzed to determine 1) whether bats performing each behavior differ between time of day using the Kruskal-Wallis test and 2) whether there is a relationship between behaviors and the weather conditions, using the Spearman correlation. To calculate the percentage, the average number of bats displaying a particular behavior in every one-hour session was first calculated and then was converted to the percentage.

For all-occurrence focal sampling, the total length of time (in sec) which focal bats spent for each behavioral category was tested by Mann-Whitney U Tests, to compare the activity budgets between adult males and females. To calculate the percentage, the total duration (in sec) which observed bats dedicated to each behavioral unit or category was divided by the total observation times and then converted to the percentage.

Significant correlation and difference of all tests were determined at the probability of P<0.05 (IBM SPSS 18.0, IBM Corp., New York, NY, U.S.A.).

RESULTS

Instantaneous scan sampling

The most common daytime behavior was sleeping (53.1 ± 13.9% of all recorded bats), followed by wing flapping (23.9 ± 11.2%), self-grooming (5.7 ± 2 .3%), wing spreading (4.1 ± 1.6%), mating/courtship (3.6 ± 1.7%), hang relax (2.8 ± 2.2%), aggression (2.4 ± 1.7%), movement (2.3 ± 1.6%), hang alert (1.9 ± 4.0%) and maternal cares (<1 ± 0.2%).

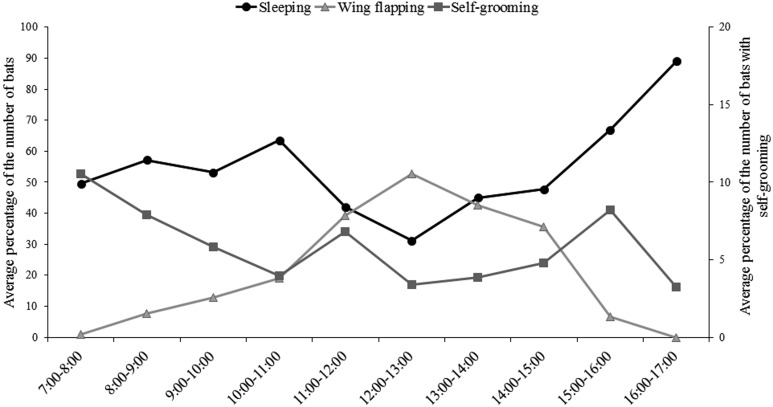

The number of the bats with sleeping, wing flapping, self-grooming, mating/courtship, showing aggression and movement differed significantly with time of day (Kruskal-Wallis test, χ2=48.26, d.f.=9, P=0.00; χ2=85.06, d.f.=9, P=0.00; χ2=26.57, d.f.=9, P=0.02; χ2=73.03, d.f.=9, P=0.00; χ2=55.40, d.f.=9, P=0.00; and χ2=37.50, d.f.=9, P=0.00, respectively). There was no statistical difference in the number of bats with wing spreading throughout the daytime (Kruskal-Wallis test, χ2=8.33, d.f.=9, P=0.501). The highest percentage of sleeping behavior was noted in late evening (1600–1700 hr), and the lowest was recorded in early afternoon (1200–1300 hr, Fig. 2). Wing flapping was the most common behavior during 1200–1300 hr and decreased consistently from late afternoon to evening (Fig. 2). The number of bats with self-grooming peaked in the early morning (0700–0800 hr) and reached the lowest level in the late evening (1600–1700 hr, Fig. 2). The number of bats with mating/courtship, aggression and movement behaviors was highest in early morning (0700–0800 hr) and dropped to the lowest level during 1000–1500 hr (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

The pattern of sleeping, wing flapping and self-grooming behaviors of P. vampyrus during 0700–1700 hr.

Fig. 3.

The pattern of mating/courtship, movement and aggression behaviors of P. vampyrus during 0700–1700 hr.

We found two types of roosting positions in the flying foxes: hang relax (HR) and hang alert (HA). HR is a resting state which can be seen throughout the day and was not influenced by time of day (Kruskal-Wallis test, χ2=7.91, d.f.=9, P=0.543). HA is the excited state of flying foxes and occurred when the flying foxes were activated by other animals, such as the ebony leaf monkey or unknown gibbon species, unexpectedly. Therefore, HA was not included in statistical analysis for behavioral variability with time of day. Maternal cares, excretion and play behaviors were not analyzed due to its rare occurrence.

The correlation analysis between the behavior of flying foxes and environmental factors showed that only wing flapping behavior was strongly correlated with ambient temperature, relative humidity and light intensity (Spearman correlation, r=0.498, P=0.00; r= −0.530, P=0.00; and r=0.637, P=0.00, respectively).

All-occurrence focal sampling

There were significant differences in diurnal activity budgets between adult males and females, except in self-maintenance, thermoregulation, negative social behavior and HA behaviors (Table 2). During daylight, females spent more time sleeping (80.5 ± 4.5% of total observation time) than males (61.0 ± 5.0%). Males engaged in sexual activities (including mating, courtship and masturbation) more than females (6.5 ± 1.6 and 0.2 ± 0.1%, respectively). Females showed a kind of positive social behavior, such as maternal care, by grooming their adjacent pups for an average of 0.4 ± 0.1% of their times, while males did not participate in parental care (Table 2). Another kind of positive social behaviors, such as mutual grooming and play behaviors, was not found in both male and female bats. There was no significant difference in times spent for negative social behavior between males and females. However, only negative social behavior observed in females is fighting, which usually occurs when they were approached by males. Whereas, males performed two kinds of negative social behaviors which were wing spreading and fighting. The proportion of time spent on HR behavior and movement in males was higher than that in females (HR: 13.2 ± 1.7 and 3.5 ± 0.9%; movement: 2.5 ± 0.4 and 0.1 ± 0.0%, respectively) (Table 2).

Table 2. Average ± SD proportion of time spent for each activity during 0700 to 1700 hr.

| Behavioral category | Behavioral unit | Male (n=5) | Female (n=5) | Z (P-value) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of time for behavioral unit (%) | Total (%) | Proportion of time for behavioral unit (%) | Total (%) | |||

| Sexual activity | Mating | 2.04 ± 0.7 | 6.5 ± 1.6 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | –4.6 (0.00) |

| Courtship | 4.06 ± 1.0 | 0 | ||||

| Masturbation | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0 | ||||

| Self-maintenance | Self-grooming | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | –0.03 (0.97) |

| Thermoregulation | Wing flapping | 11.9 ± 7.1 | 11.9 ± 7.1 | 10.9 ± 4.9 | 10.9 ± 4.9 | –1.6 (0.10) |

| Positive social behavior | Maternal care | 0 | 0 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | –2.4 (0.01) |

| Mutual grooming | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Play | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Negative social behavior | Fighting | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.5 | 0.7 ± 0.5 | –0.9 (0.35) |

| Wing spreading | 0.4 ± 0.0 | 0 | ||||

| Non-categorized | Sleeping | 61.0 ± 5.0 | 80.5 ± 4.5 | –3.2 (0.01) | ||

| Hang relax | 13.2 ± 1.7 | 3.5 ± 0.9 | –2.2 (0.02) | |||

| Hang alert | 1.9 ± 1.3 | 1.3 ± 1.2 | –1.1 (0.23) | |||

| Movement | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | –3.8 (0.00) | |||

| Excretion | 0 | 0 | ||||

Z=Mann-Whitney U Test; P<0.05 two-tailed test.

Interspecies interaction

The interactions between the flying foxes and other wildlife were recorded throughout the observation period. The flying foxes often interacted with the non-human primate, Trachypithecus auratus (ebony leaf monkey). Ebony leaf monkeys disturbed flying foxes by their vocallization and their presence on the roosting trees an average of 3.3 ± 0.5 times a day. This caused a roosting shift of flying foxes during the daytime an average of 1.8 ± 0.3 times a day. HA behavior was mainly triggered by ebony leaf monkeys, but sometimes by unknown wildlife that we could not identify to the species level, such as gibbon in the family Hylobatidae. Due to dense tree covers at the observation points, it was unclear if there was direct contact between the bats and the monkeys. Not only did the flying foxes face disturbances by wildlife, but they also faced illegal hunters. The observers recognized other potential predators of flying foxes, such as long-tailed macaque (Macaca fascicularis) and crested serpent eagle (Spilornis cheela). Futhermore, there were two nests of wild boars (Sus scrofa) under the roosting area, where was highly contaminated with flying fox’s feces.

DISCUSSION

Daytime activities of P. vampyrus

It is well known that flying foxes are nocturnal animal, but they are active during daytime hours. The flying foxes performed both solitary and social behaviors besides sleeping (Figs. 2 and 3). This study revealed that sleeping was the most common behavior that occurred mostly in the late evening (Fig. 2). This finding is consistent with that of a previous study on P. poliocephalus [6], who found that the highest percentage of bats asleep primarily occurred during the evening. Wing flapping was the most common behavior during noon and early afternoon. The flying foxes in the tropical zone are usually exposed to high temperatures with strong sunlight during daytime. They typically lack sweat glands for cooling the skin surface and reducing body temperature [40]. Therefore, wing flapping is considered to be the thermoregulatory behavior that flying foxes use for controlling their body temperature, when the ambient temperature is higher than the range of the thermoneutral zone (the range of environmental temperatures without regulatory changes in metabolic heat production of animal) that lies between 24 to 35°C [16, 27].

Self-grooming was one of the common behaviors which can be seen throughout the day, but mostly occurred in early morning (Fig. 2). A similar pattern has been observed in another frugivorous bats, P. poliocephalus [6]. Nelson suggested [26] that the function of self-grooming is for cleaning the body and wing membrane or reducing oil secretions. For self-maintenance, it is important to keep the wing soft and flexible by spreading the lipid droplets around the wing membrane by self-grooming [39]. In addition, it is a behavioral strategy for reducing the ectoparasite density, which tends to be higher in rainy seasons [21, 44]. The high level of gene flow in the blood-feeding parasite (Cyclopodia horsfieldi) found on the body of flying foxes suggested that there were frequent contacts among the flying fox species living in the South-East Asia region [30]. The contacts between host species were promoted by the encounter during foraging in the same habitat or roosting in dense colony and thus enable ectoparasite movements between hosts [31]. Even though bat flies have high degree of host specificity, the disturbance by host’s behavior, such as self-grooming, should lead to abandonment of host and/or host switching by bat flies [8]. Therefore, self-grooming is the potential behavior that allows the spreading of zoonotic diseases in Pteropus species.

The reproductive period of P. vampyrus varies geographically and seasonally. The flying foxes living in Peninsular Malaysia have the peak of pregnancy in November and January. In Thailand, pregnancy has been noted in the same period of those in Malaysia, but infants are born during March and early April. In the Philippines, the parturition occurs during April and May [19]. From this information, we can infer that the peak of mating season of the large flying foxes in these countries would be during November and January, because the gestation period of flying foxes is approximately 4 months [27]. However, fruit bats in the family Pteropodidae have a mechanism to delay embryo implantation or interrupt the embryo development in order to coordinate birth with the period of maximum food availability and to create optimal conditions for raising the young bats [27]. Therefore, we could not expect the period of mating season precisely, without daytime behavioral observation. This study found that males tried to approach females for mating many times in a day. This suggests that breeding season of P. vampyrus in Indonesia would cover our observation period in May. The highest frequency of mating/courtship behavior was noted in the early morning, and it tended to decrease gradually toward noon (Fig. 3). This result corresponded to variation in testosterone secretion levels of P. vampyrus, which was high in the early morning and gradually decreased during the day, but this variation was not significantly different [37]. Before mating, males showed courtship behavior by licking around genital area of female, and this often leads to the aggressive behavior of females to reject males. After being rejected by the first female, males tried to find other females several times, until they could mate with female. This leads to high contact rates with body fluid exchanges between males and females during mating season. The authors therefore suggest that male bats have a higher potential to spread viruses within the population. When females refused males, male bats sometimes groomed their penis, resulting in the erection of the penis. This penile grooming is considered masturbation in flying foxes [26]. Aggression and movement patterns showed similar trends to mating/courtship patterns that peaked in the morning and gradually declined during the day (Fig. 3). Aggressive behavior of flying foxes has been shown to be influenced by hormonal regulation [36]. The elevations of glucocorticoid was considered a stress response, which usually occurred in breeding males during mating seasons. And, this is the reason why breeding males are more aggressive than non-breeding males [36]. During fighting, bats bite or scratch each other by their claws which are usually contaminated by saliva during self-grooming, and this is a possible way to transmit viruses. Movement activity mainly occurred when the courtship display by males was initiated. Once males moved closer to females, females initially rejected males by showing aggressive behavior and moving away, resulting in the frequent movement of the flying foxes during the mating/courtship period.

Our finding suggests that sexual activities and related behaviors, such as fighting between sexes and competition between males, are the potential actions that promote intra-species transmission through high rates of direct contacts during breeding season. In temperate zone, seasonal variation in prevalence of rabies viruses relates to life history pattern of bats that includes seasonal migration and reproduction [11]. Therefore, it is possible that seasonal changes in these social behaviors affecting the contact rates between the flying foxes, may be biological mechanism driving disease transmission within the host population.

Differences in time-activity budgets between males and females

Adults of both sexes spent the majority of daytime sleeping (Table 2). However, females spent more time sleeping than males. This indicates that males were more active than females during daytime hours. Demment suggested [7] that the high energetic demand for reproduction effects the activity budgets of females, and this is the reason why females require more time for feeding and resting rather than males. We found differences in time spent on sexual activities, movement, hanging relax and positive social behaviors between sexes. Males allocated their time to sexual activities, movement and hanging relax more than females during the observation period. Prior to the beginning of mating season, male P. alecto marked mating territories by rubbing their necks and shoulders on tree branches [24]. This behavior also had been observed in male P. vampyrus living in the Philippines (unpublished data). The breeding territories of flying foxes contain up to six females, referred as a “harem” [17, 27]. The higher activity level of males should be partly involved in harem maintenance that provides more mating opportunities and increases reproductive success for males.

Only positive social behavior found in this study was maternal care, which occurred between mother and its independent child. Normally, the contact rates between lactating female and offspring are increased during early of lactation period [15]. Use of saliva during maternal grooming facilitates infection and enables the parasite movement between bats, as well as sexual activities and fighting behavior. The positive social behavior, such as mutual grooming, was not observed in this study. However, this behavior was recorded in P. poliocephalus and in Cynopterus sphinx, which helps to establish the social bonds among group members [26, 35]. Seasonal Nipah virus surveillance on P. lylei, in Thailand suggested that the viral genome was found frequently during the reproductive periods: mating, parturition and lactation periods [45]. This highly supports the role of sexual activities and maternal care behaviors on the viral transmission within the bat colony. In general, females become immunosuppressed during peri-parturition periods making them susceptible to viral infection [33]. Thus, the appearance of a lactating female with offspring may be a sign of the emergence of a virus.

Interspecies interaction: the driver of the emergence of zoonotic disease

This study discovered the risk of viral transmission between bats and other wildlife living in the same habitat. The flying foxes had conflicts with T. auratus (ebony leaf monkey) for living space, and this caused a roosting shift of flying foxes in the day. It was unclear why the monkeys invaded the roosting tree of the flying foxes. It is possible that the flying foxes occupied a tree that might be food resources of the monkeys. Ebony leaf monkeys would not be a predator of flying foxes, because they are herbivores [18]. Our questionnaire, for the residents and governmental rangers (over 150 persons) also supported that the monkeys do not eat flying foxes. However, the monkey may be exposed to infectious bodily fluids of the flying foxes that deposited on tree branches. This is one possibility that viruses are transmitted to other animals in the wild. The flying foxes in this area still face with human encroachments for commercial purposes, because flying fox trading is still active in many regions of Indonesia [14]. The human-bat interactions have been taken place on a large scale in Asia and Africa [15] and thus enhance bat-to-human spillover risk. In addition to humans, the long-tailed macaque (M. fascicularis) and crested serpent eagle (S. cheela) could be considered potential predators of the flying foxes in this study area. Ecological interactions, such as predation, also lead to direct contacts between the predators and the flying foxes that enable the mutual exchange of body fluids, such as saliva and blood. This could be a one factor that drives zoonotic disease transmission in the wild. Wild boars (Sus scrofa) utilized the habitat under the roosting area, which was contaminated with urine/feces of flying foxes. As a result, wild boars face a higher chance of exposure to bat waste and become one of the potential recipients of pathogens without any direct contact with the flying foxes. Therefore, the surveillance of bat viruses in the animals and humans that have direct or indirect contacts with flying foxes is necessary for the prevention of viral spillovers in this region.

The existence and propagation of viruses depend on multiple factors: host cell, host itself, host population and host community [32]. In this study, we focused on the levels of host population and host community. The flying foxes, as a natural host, are highly social animals that communicate with each other by vocalization and social behaviors. Social behaviors lead to direct contacts between bat individuals, and this enhances the opportunity for virus sharing within/between bat populations. In the wild, the flying fox’s community is surrounded by diverse wildlife communities. This condition enables interspecies interactions and transmission of pathogens. Flying foxes also have great ability to make long distance flights. Therefore, transmission of pathogens also has to be considered at the inter-community level, using a satellite telemetry system as a tool for investigation.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants from Leuweung Sancang Natural Conservation Area office, Ministry of Environment and Forestry for supporting on field observation and the Faculty of Forestry, Bogor Agricultural university for plant species identification. This project was supported by Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and Japan Agency for Medical Reserch and Development (AMED).

REFERENCES

- 1.Allworth A., Murray K., Morgan J.1996. A human case of encephalitis due to a lyssavirus recently identified in fruit bats. CDI 20: 504. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altmann J.1974. Observational study of behavior: sampling methods. Behaviour 49: 227–267. doi: 10.1163/156853974X00534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altringham J. D.1996. Bats: Biology and Behaviour, Oxford University Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calisher C. H., Childs J. E., Field H. E., Holmes K. V., Schountz T.2006. Bats: important reservoir hosts of emerging viruses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19: 531–545. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00017-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chua K. B.2003. Nipah virus outbreak in Malaysia. J. Clin. Virol. 26: 265–275. doi: 10.1016/S1386-6532(02)00268-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connell K. A., Munro U., Torpy F. R.2006. Daytime behaviour of the grey-headed flying fox Pteropus poliocephalus Temminck (Pteropodidae: Megachiroptera) at an autumn/winter roost. Aust. Mammal. 28: 7–14. doi: 10.1071/AM06002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demment M. W.1983. Feeding ecology and the evolution of body size of baboons. Afr. J. Ecol. 21: 219–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2028.1983.tb00323.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dick C. W., Patterson B. D.2007. Against all odds: explaining high host specificity in dispersal-prone parasites. Int. J. Parasitol. 37: 871–876. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Field H. E., Smith C. S., de Jong C. E., Melville D., Broos A., Kung N., Thompson J., Dechmann D. K.2016. Landscape utilization, animal behaviour and hendra virus risk. EcoHealth 13: 26–38. doi: 10.1007/s10393-015-1066-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujita M. S., Tuttle M. D.1991. Flying foxes (Chiroptera: Pteropodidea): threatened animal of key ecological and economic importance. Conserv. Biol. 5: 455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.1991.tb00352.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.George D. B., Webb C. T., Farnsworth M. L. O., O’Shea T. J., Bowen R. A., Smith D. L., Stanley T. R., Ellison L. E., Rupprecht C. E.2011. Host and viral ecology determine bat rabies seasonality and maintenance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108: 10208–10213Nat. Ac. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010875108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gumert M. D., Fuentes A., Jones-Engel L.2011. Monkeys on the Edge: Ecology and Management of Long-tailed Macaques and their Interface with Humans, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han H. J., Wen H. L., Zhou C. M., Chen F. F., Luo L. M., Liu J. W., Yu X. J.2015. Bats as reservoirs of severe emerging infectious diseases. Virus Res. 205: 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2015.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrison M. E., Cheyne S. M., Darma F., Ribowo D. A., Limin S. H., Struebig M. J.2011. Hunting of flying foxes and perception of disease risk in Indonesian Borneo. Biol. Conserv. 144: 2441–2449. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2011.06.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayman D. T., Bowen R. A., Cryan P. M., McCracken G. F., O’Shea T. J., Peel A. J., Gilbert A., Webb C. T., Wood J. L. N.2013. Ecology of zoonotic infectious diseases in bats: current knowledge and future directions. Zoonoses Public Health 60: 2–21. doi: 10.1111/zph.12000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kingma B., Frijns A., van Marken Lichtenbelt W.2012. The thermoneutral zone: implications for metabolic studies. Front. Biosci. (Elite Ed.) 4: 1975–1985. doi: 10.2741/e518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klose S. M., Welbergen J. A., Kalko E. K.2009. Testosterone is associated with harem maintenance ability in free-ranging grey-headed flying-foxes, Pteropus poliocephalus. Biol. Lett. 5: 758–761. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kool K. M.1992. Food selection by the silver leaf monkey,Trachypithecus auratus sondaicus, in relation to plant chemistry. Oecologia 90: 527–533. doi: 10.1007/BF01875446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kunz T. H., Jones D. P.2000. Pteropus vampyrus. Mamm. Species 642: 1–6. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leroy E. M., Kumulungui B., Pourrut X., Rouquet P., Hassanin A., Yaba P., Délicat A., Paweska J. T., Gonzalez J. P., Swanepoel R.2005. Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus. Nature 438: 575–576. doi: 10.1038/438575a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linhares A. X., Komeno C. A.2000. Trichobius joblingi, Aspidoptera falcata, and Megistopoda proxima (Diptera : Streblidae) parasitic on Carollia perspicallata and Sturnia lillium (Chiroptera : Phyllostomidae) in southeastern Brazil: sex ratios, seasonality, host site preference, and effect of parasitism on the host. J. Parasitol. 86: 167–170. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2000)086[0167:TJAFAM]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luis A. D., Hayman D. T. S., O’Shea T. J., Cryan P. M., Gilbert A. T., Pulliam J. R. C., Mills J. N., Timonin M. E., Willis C. K., Cunningham A. A., Fooks A. R., Rupprecht C. E., Wood J. L. N., Webb C. T.2013. A comparison of bats and rodents as reservoirs of zoonotic viruses: are bats special? Proc. Biol. Sci. 280: 20122753. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.2753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markus N., Blackshaw J. K.2002. Behaviour of the Black flying fox Pteropus alecto: 1. An ethogram of behaviour, and preliminary characterisation of mother-infant interactions. Acta Chiropt. 4: 137–152. doi: 10.3161/001.004.0203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Markus N., Blackshaw J. K.2002. Behaviour of the Black Flying Fox Pteropus alecto: 2. Territoriality and Courtship. Acta Chiropt. 4: 153–166. doi: 10.3161/001.004.0204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin P., Bateson P.2007. Measuring Behaviour: An Introductory Guide, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson J. E.1965. Behaviour of Australian pteropodidae (Megachiroptera). Anim. Behav. 13: 544–557. doi: 10.1016/0003-3472(65)90118-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neuweiler G.2000. The Biology of Bats, Oxford University Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nijman V.2000. Geographic distribution of ebony leaf monkey Trachypithecus auratus (E. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1812) (Mammalia: Primates: Cercopithecidae). Contrib. Zool. 69: 157–177. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nowak R. M.1994. Walkers Bats of the World, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olival K. J., Dick C. W., Simmons N. B., Morales J. C., Melnick D. J., Dittmar K., Perkins S. L., Daszak P., Desalle R.2013. Lack of population genetic structure and host specificity in the bat fly, Cyclopodia horsfieldi, across species of Pteropus bats in Southeast Asia. Parasit. Vectors 6: 231. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patterson B. D., Ballard J. W. O., Wenzel R. L.1998. Distributional evidence for cospeciation between neotropical bats and their bat fly ectoparasites. Stud. Neotrop. Fauna Environ. 33: 76–84. doi: 10.1076/snfe.33.2.76.2152 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plowright R. K., Eby P., Hudson P. J., Smith I. L., Westcott D., Bryden W. L., Middleton D., Reid P. A., McFarlane R. A., Martin G., Tabor G. M., Skerratt L. F., Anderson D. L., Crameri G., Quammen D., Jordan D., Freeman P., Wang L. F., Epstein J. H., Marsh G. A., Kung N. Y., McCallum H.2015. Ecological dynamics of emerging bat virus spillover. Proc. Biol. Sci. 282: 20142124. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.2124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Plowright R. K., Field H. E., Smith C., Divljan A., Palmer C., Tabor G., Daszak P., Foley J. E.2008. Reproduction and nutritional stress are risk factors for Hendra virus infection in little red flying foxes (Pteropus scapulatus). Proc. Biol. Sci. 275: 861–869. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.1260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pourrut X., Kumulungui B., Wittmann T., Moussavou G., Délicat A., Yaba P., Nkoghe D., Gonzalez J. P., Leroy E. M.2005. The natural history of Ebola virus in Africa. Microbes Infect. 7: 1005–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rathinakumar A., Cantor M., Senthikumar K., Vimal P., Kaliraj P., Marimuthu G.2017. Social grooming among Indian short-nosed fruit bats. Behaviour 154: 37–63. doi: 10.1163/1568539X-00003410 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reeder D. M., Kosteczko N. S., Kunz T. H., Widmaier E. P.2006. The hormonal and behavioral response to group formation, seasonal changes, and restraint stress in the highly social Malayan Flying Fox (Pteropus vampyrus) and the less social Little Golden-mantled Flying Fox (Pteropus pumilus) (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae). Horm. Behav. 49: 484–500. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reeder D. M., Raff H., Kunz T. H., Widmaier E. P.2006. Characterization of pituitary-adrenocortical activity in the Malayan flying fox (Pteropus vampyrus). J. Comp. Physiol. B 176: 513–519. doi: 10.1007/s00360-006-0073-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reisland M. A., Lambert J. E.2016. Sympatric apes in sacred forests: shared space and habitat use by humans and endangered Javan gibbons (Hylobates moloch). PLOS ONE 11: e0146891. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richards G., Hall L., Parish S.2012. A Natural History of Australian Bats: Working the Night Shift, CSIRO Press, Melbourne. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robinson K. W., Morrison P. R.1957. The reaction to hot atmospheres of various species of Australian marsupial and placental animals. J. Cell. Comp. Physiol. 49: 455–478. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1030490306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sendow I., Ratnawati A., Taylor T., Adjid R. M. A., Saepulloh M., Barr J., Wong F., Daniels P., Field H.2013. Nipah virus in the fruit bat Pteropus vampyrus in Sumatera, Indonesia. PLoS ONE 8: e69544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Setiawan Y., Yoshinol K., Prasetyo L. B.2014. Characterizing the dynamics change of vegetation cover on tropical forestlands using 250 m multi-temporal MODIS. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 26: 132–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jag.2013.06.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sidiyasa K., Sutomo S., Prawira R. S. A.1990. Structure and composition of a lowland Dipterocarp forest at Leuweung Sancang Nature Reserve, West Java [1985]. AGRIS 471: 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ter Hofstede H. M., Fenton M. B.2005. Relationships between roost preferences, ectoparasite density, and grooming behaviour of neotropical bats. J. Zool. (Lond.) 266: 333–340. doi: 10.1017/S095283690500693X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wacharapluesadee S., Boongird K., Wanghongsa S., Ratanasetyuth N., Supavonwong P., Saengsen D., Gongal G. N., Hemachudha T.2010. A longitudinal study of the prevalence of Nipah virus in Pteropus lylei bats in Thailand: evidence for seasonal preference in disease transmission. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 10: 183–190. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2008.0105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]