Abstract

The eastern bent-winged bat (Miniopterus fuliginosus) is an insectivorous bat that lives in the caves, throughout Japan [11]. The bats aggregate in cave in populations of tens to thousands of individuals. We examined the mitochondrial D-loop sequences of bats in Wakayama, Japan, and divided them into 35 haplotypes. The sequences of 3 haplotypes in Wakayama were the same as those of 10 Miniopterus fuliginosus individuals living in China. Given the substitution rate of the D-loop region, we speculated that the bats had moved between Japan and China within the last 16,000 years. We could not determine how the bats crossed the sea; however, it is possible that the bats undergo dynamic movement widely throughout East Asia.

Keywords: D-loop region, genetic diversity, insectivorous bat, Miniopterus fuliginosus

The eastern bent-winged bat Miniopterus fuliginosus is an insectivorous bat that lives in caves and tunnels during the day. This bat species can be found widely in Japan, except for Hokkaido [11]. The bats aggregate in caves in populations of tens to thousands of individuals. In Japan, only 6 caves have been found where pregnant bats give birth and raise the offspring collaboratively [11]. From the middle of June to the middle of August, thousands of pregnant females migrate to these nursery roosts. One of the nursery roosts is a sea cave in Wakayama Prefecture, Japan, and 15,000 female bats move there every year. When the offspring reaches 2 months old, the group of the female bats and offspring fly away from the sea cave. These bats are found in the winter roosts, which are located 10–200 km away from the sea cave [16].

In this study, we examined the diversity of the D-loop region in the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) of eastern bent-winged bats in Wakayama Prefecture. The D-loop is a non-coding region with many accumulated mutations [2, 6], and it is suitable for the analysis of the genetic diversity and phylogeography of the maternal lineage in an animal species. Here, we examined the genetic characteristics of the eastern bent-winged bats in Wakayama Prefecture and compared the D-loop sequences found in Wakayama to those found in other regions (the sequence data were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), Bethesda, MD, U.S.A.).

Ninety-four bats were captured using the net in a tunnel located in Wakayama prefecture (33.708N 135.413E). It was approved by Wakayama prefecture (approval number: Nishi 1, 2, 3 and 4). The tunnel locates approximately eight kilometers away from the sea cave and is used as a winter roost. All experimental procedures were performed under isoflurane anesthesia. The blood was taken from the heart, and then, a liver or blood cell pellet was collected from 94 bats for DNA extraction, using DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kits (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). The D-loop region was amplified by polymerase chain reaction with two specific primers for the bat: 5ʹ-CCCATCTGATATAGATGCCA-3ʹ and 5ʹ-TACAGCTTAGCCAAGGCTTA-3ʹ. After electrophoresis of the PCR products, the target band was excised from the gel, and DNA was extracted using QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN). The purified DNA was used as the template for direct sequencing with the primer; 5ʹ-TAGTTCCTCCAAAGACTCAA-3ʹ [BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, U.S.A.)]. After sequencing the D-loop region (294 bp), a phylogenetic tree was constructed. The sequence data of the D-loop region of Miniopterus schreibersii schreibersii and Miniopterus schreibersii pallidus (GenBank accession numbers FJ028620 and FJ028645, respectively) were used as an outgroup. The neighbor-joining (NJ) method [13] in MEGA7 [10] was used for the phylogenetic tree analysis. The confidence of each branch was assessed by 1,000 bootstrap replications [8]. A network tree was also constructed and analyzed by the median-joining method [1] in PopART (ALLAN WILSON CENTER, Palmerston North, New Zealand). To investigate the phylogenetic relations between Wakayama and other regions, we used data from Chinese bats (Miniopterus fuliginosus), which were the only available data containing the D-loop sequences and the precise locations of the roosting sites of the bats (GenBank accession numbers KM230117-KM230225).

There were 45 base substitutions over a DNA segment 294 bp length. Forty substitution sites were transitional mutations, in which a purine nucleotide was changed to another purine (A↔G) or a pyrimidine nucleotide was changed to another pyrimidine (C↔T). Five sites were transversion mutations, in which a purine was changed to a pyrimidine and vice versa (e.g., C↔G). There were no deletion or insertion mutations in the DNA segments.

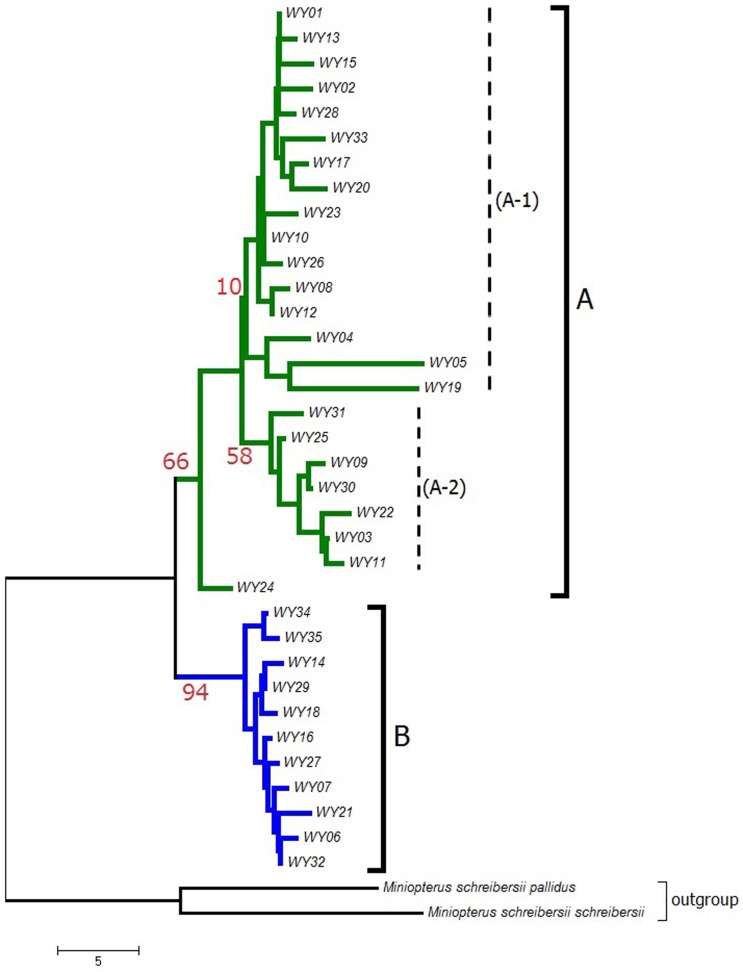

The 94 bats in Wakayama were divided into 35 haplotypes (WY01-35) (Fig. 1 and Table 1). The data were compared to those from 109 bats in China. Three haplotypes (WY07, WY27 and WY30) from the bats in Wakayama had 100% sequence similarity to 10 Chinese bats.

Fig. 1.

A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method in MEGA7. Ninety-four bats were divided into 35 haplotypes. The number indicates the bootstrap value, and each haplotype is shown as WY01-35.

Table 1. The number of the bats in each haplotype.

| haplotype | head |

|---|---|

| WY1 | 3 |

| WY2 | 3 |

| WY3 | 3 |

| WY4 | 2 |

| WY5 | 1 |

| WY6 | 1 |

| WY7 | 7 |

| WY8 | 8 |

| WY9 | 1 |

| WY10 | 8 |

| WY11 | 5 |

| WY12 | 5 |

| WY13 | 4 |

| WY14 | 4 |

| WY15 | 3 |

| WY16 | 1 |

| WY17 | 2 |

| WY18 | 1 |

| WY19 | 1 |

| WY20 | 1 |

| WY21 | 1 |

| WY22 | 6 |

| WY23 | 2 |

| WY24 | 1 |

| WY25 | 1 |

| WY26 | 1 |

| WY27 | 4 |

| WY28 | 2 |

| WY29 | 1 |

| WY30 | 3 |

| WY31 | 1 |

| WY32 | 1 |

| WY33 | 1 |

| WY34 | 4 |

| WY35 | 1 |

The phylogenetic tree was divided into 2 clades (A and B) using the bootstrap results. The bootstrap values of clades A and B were 66 and 94, respectively. Although the bootstrap values were low (10 and 58), it may be possible to divide clade A into 2 subclades (A-1 and A-2) by including more individuals in the future. Clade A contained a total of 24 haplotypes, and B contained 11. All haplotypes belonging to B had 1–3 base substitutions and shared 98–99% homology with each other. However, 5 haplotypes (WY04, WY05, WY19, WY20 and WY24) in clade A had more base substitutions than the rest of the haplotypes in clade A. There was only 1 bat each for the haplotypes, WY04, WY05, WY19, WY20 and WY24. The homology of these 5 haplotypes to those of the other bats in clade A-1 was relatively low (WY04 94–98%, WY05 94–95%, WY19 94–95%, WY20 94–98% and WY24 93–98%). These results suggested that these 5 haplotypes were not common in the bat population in Wakayama. They might represent bats that had migrated and joined the population in Wakayama.

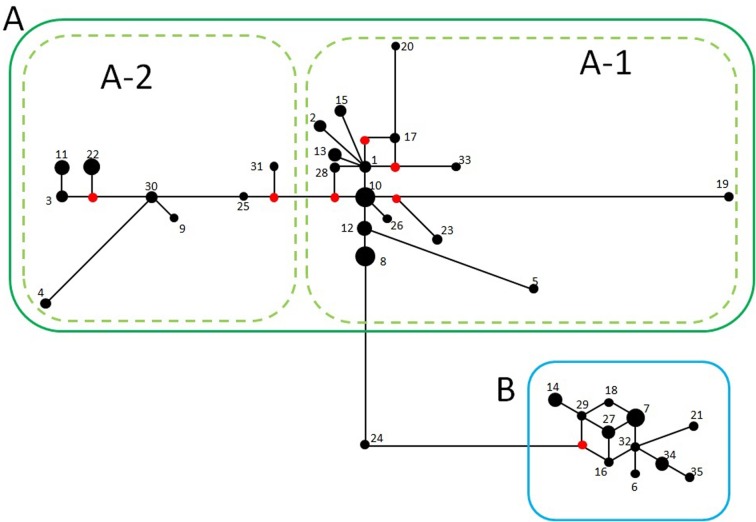

The network tree presents the individual number in each haplotype and the substitution frequencies (Fig. 2). This tree had many branches and formed the clades. There were only a few missing haplotypes in each clade. The lack of a star-like pattern for each clade suggested that the bat population in Wakayama has remained stable for a long time. In each clade, there were many haplotypes with 1–3 base substitutions, and the genetic distance of these haplotypes was close to each other. We assumed that these substitutions occurred more recently, and it is possible that there are other haplotypes that have recently appeared but that we did not identify in this study due to the large population of the bats in Wakayama.

Fig. 2.

A network tree was constructed using the median-joining method in PopART. Each number represents the name of a haplotype without the prefix “WY”. The size of circles represents the number of bats, and the length of a line represents the substitution frequency. The red circle indicates the missing haplotypes.

The sequences of 3 haplotypes (WY07, WY27 and WY30) in Wakayama were consistent with the sequences of those of 10 bats in China. WY30 belonged to clade A, and WY07 and WY27 belonged to clade B. Two bats, which were caught in Jiangxi (28.214N 117.690E) and Fujian (25.428N 119.735E), had the WY07 haplotype. Two bats caught in Henan (31.833N 115.267E and 32.396N 113.276E) were identified as WY30. Six bats had the WY27 haplotype: 3 of these bats were from Anhui (31.005N 118.302E), and the other 3 were captured in Jiangxi (29.388N 117.702E), Yunnan (26.040N 104.090E) and Shaanxi (33.586N 109.164E).

Given the substitution rate in the D-loop region (20% per million years) [12], we speculated that the Chinese bats, which had the same sequences as 3 haplotypes found in Wakayama, had moved between China and Japan within the last 16,000 years. Because the Japanese Archipelago was isolated from the continent 15,000 years ago [7, 9], the bats might have migrated across the sea. A possible route of movement of bats from China to Wakayama is through the Korean Peninsula. The insectivorous bats have been reported to cross seas using cargo ships and aircraft [3, 4, 15]. The juvenile female Japanese pipistrelle (Pipistrellus javanicus abramus), which was not found in New Zealand, was found on a ship traveling from Japan to New Zealand [5]. Moreover, big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus) moved from California to Hawaii [14]. The eastern pipistrelle bat (Pipstrellus subflavus) reached Texas from Mexico by airplane [3]. We cannot confirm whether Miniopterus fuliginosus flew over the sea on its own or was carried by a ship or airplane; however, small insectivorous bats might have a dynamic wide range of movement throughout East Asia.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Suzuki and members of laboratory of Veterinary Microbiology, Joint Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Yamaguchi University for sampling and the anatomy of many bats.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bandelt H. J., Forster P., Röhl A.1999. Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16: 37–48. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown G. G., Gadaleta G., Pepe G., Saccone C., Sbisà E.1986. Structural conservation and variation in the D-loop-containing region of vertebrate mitochondrial DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 192: 503–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burns K. F., Farinacci C. F., Murnane T. G.1956. Insectivorous bats naturally infected with rabies in Southwestern United States. Am. J. Public Health Nations Health 46: 1089–1097. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.46.9.1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Constantine D. G.2003. Geographic translocation of bats: known and potential problems. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9: 17–21. doi: 10.3201/eid0901.020104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniel M. J., Yoshiyuki M.1982. Accidental importation of a Japanese bat into New Zealand. N.Z. J. Zool. 9: 461–462. doi: 10.1080/03014223.1982.10423877 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desjardins P., Morais R.1990. Sequence and gene organization of the chicken mitochondrial genome. A novel gene order in higher vertebrates. J. Mol. Biol. 212: 599–634. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90225-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dobson M.1994. Patterns of distribution in Japanese land mammals. Mammal Rev. 24: 91–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2907.1994.tb00137.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Felsenstein J.1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39: 783–791. doi: 10.2307/2408678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keigwin L. D., Gorbarenko S. A.1992. Sea level, surface salinity of the Japan sea, and the younger dryas event in the Northwestern pacific ocean. Quat. Res. 37: 346–360. doi: 10.1016/0033-5894(92)90072-Q [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K.2016. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33: 1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maeda K.2009. An estimate of population of Miniopterus fuliginosus in Japanese Islands. Bull. Center Nat. Environ. Educ. Nara Univ. Educ. 10: 31–37(in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petit E., Excoffier L., Mayer F.1999. No Evidence of bottleneck in the postglacial recolonization of Europe by the noctule bat (Nyctalus noctula). Evolution 53: 1247–1258. doi: 10.2307/2640827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saitou N., Nei M.1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4: 406–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sasaki D. M., Middleton C. R., Sawa T. R., Christensen C. C., Kobayashi G. Y.1992. Rabid bat diagnosed in Hawaii. Hawaii Med. J. 51: 181–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiles G. J., Hill J. E.1986. Accidental aircraft transport of a bat to Guam. J. Mammal. 67: 600–601. doi: 10.2307/1381298 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu H., Maeda K., Inoue R., Suzuki K., Sano A., Tsumura M., Hashimoto H., Teranishi T., Okumura K., Abe Y.2005. Migration of young Bent-winged bats, Miniopterus fuliginosus born in Shirahama, Wakayama Prefecture (1) Records from the years 2003 and 2004. Bull. Center Nat. Environ. Educ .Nara Univ. Educ. 7: 31–37(in Japanese). [Google Scholar]