Abstract

Introduction

There is little evidence available on the efficacy and safety of biologic therapies for the treatment of psoriasis in Hispanic patients. Secukinumab is demonstrated to be highly effective for clearing psoriasis. The aim of this study was to compare the efficacy and safety of secukinumab in Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients.

Methods

Data were pooled from four phase 3 studies of secukinumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Patients who self-identified as Hispanic were included in the Hispanic subgroup.

Results

Efficacy responses (Psoriasis Area and Severity Index [PASI] 75/90/100 and Investigator’s Global Assessment 2011 modified version 0/1) for secukinumab 300 mg were greater than for etanercept at week 12 in the Hispanic and non-Hispanic patient subgroups. At week 12 with secukinumab 300 mg, PASI 90/100 responses were achieved by 70.6%/35.9% of Hispanic patients and 58.0%/28.1% of non-Hispanic patients. At week 12 with secukinumab 150 mg, PASI 90/100 responses were achieved by 59.5%/25.1% of Hispanic patients and 41.2%/13.4% of non-Hispanic patients. In both subgroups, peak efficacy responses with secukinumab were observed at week 16 and were maintained to week 52.

Conclusions

Secukinumab is highly effective for clearing psoriasis in both Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients.

Funding

Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-017-0521-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Biologic therapy, Dermatology Life Quality Index, Hispanic, IL-17, Moderate-to-severe psoriasis, Non-Hispanic, Pooled analysis, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, Secukinumab, Subcutaneous injection

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated, inflammatory skin disease in which interleukin-17 has been shown to play a key role in the underlying pathogenesis [1]. Secukinumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody that selectively neutralizes interleukin-17A, has been shown to have significant efficacy in the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, demonstrating a rapid onset of action and sustained responses with a favorable safety profile [2–6]. Secukinumab is currently approved in several countries including the USA for the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis [7, 8].

The prevalence of psoriasis is highly variable among different populations [9]. A cross-sectional study (N = 6218) using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009–2010 data to determine psoriasis prevalence rates among US adults oversampled African-American, Mexican-American, and low-income Caucasian-American populations to increase accuracy in prevalence determination amongst these underrepresented groups [10]. Psoriasis prevalence rates among adults aged 20–59 years were reported to be highest in the Caucasian population at 3.6% (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.7–4.4%) and lower in the Hispanic population 1.6% (95% CI 0.5–2.8%) [10]. Additionally, optimal treatment of psoriasis in the Hispanic population from the USA may be negatively impacted because Hispanic patients are less likely to see a dermatologist when having skin problems [11].

Understanding the impact of psoriasis and its treatment on the Hispanic population is crucial because people who identify as being of Hispanic or Latino origin represented approximately 16% of the overall US population in 2010, which was an increase from 13% in 2000 [12]. Further, the increase in the Hispanic population between 2000 and 2010 (15.2 million) accounted for over half of the increase in the overall population of the USA (27.3 million). Although some studies have investigated the burden of psoriasis on patient quality of life (QoL), few have examined non-Caucasian populations, and examinations of response to treatment among underrepresented populations are rare [13]. In a retrospective analysis (N = 2511) investigating racial/ethnic differences in response to treatment with etanercept for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis, no significant differences in the safety or efficacy of etanercept treatment or in disease impact on patient QoL at week 12 were reported [13]. Although Caucasian patients had better health-related QoL at baseline compared with Hispanic/Latino patients (mean Dermatology Life Quality Index [DLQI] score, 12.0 [standard deviation (SD) 6.51] vs 14.6 [SD 6.93], respectively), the Hispanic/Latino subgroup demonstrated the greatest numerical improvement from baseline in mean DLQI scores (8.45 [SD 6.18] vs 10.78 [SD 6.96], respectively) after 12 weeks of treatment with etanercept. Notably, the percentage of patients with prior psoriasis therapy was significantly lower in the Hispanic/Latino subgroup versus the Caucasian subgroup (88% vs 94%, respectively; P = 0.0049), which the authors suggested may be reflective of access to care. However, findings for Hispanic patients in this study may be confounded because of ethnic differences (Hispanic/Latino) compared to racial differences (Caucasian). Overall, there is a lack of studies assessing biologic treatment of Hispanic patients with psoriasis.

In this pooled analysis of four phase 3 pivotal trials, we present results regarding the efficacy and safety of secukinumab for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis in Hispanic patients and compare these findings to those in non-Hispanic patients.

Methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and with the approval of each institutional review board. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

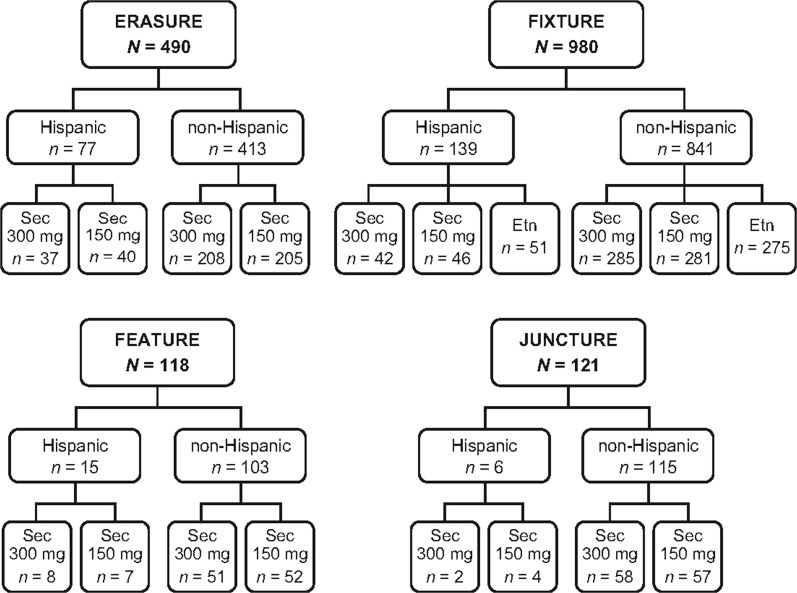

Data from Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis were pooled from four phase 3, randomized, double-blind studies of secukinumab (Fig. 1). The included studies were ERASURE, FIXTURE, FEATURE, and JUNCTURE [2–4].

Fig. 1.

Composition of pooled study population by phase 3 trial. Etn etanercept, Sec secukinumab

All studies included patients at least 18 years of age with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis that was diagnosed at least 6 months before randomization and was poorly controlled with topical, phototherapy, and/or systemic therapy. Patients were required to have a baseline composite Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score of at least 12, an Investigator’s Global Assessment 2011 modified version (IGA mod 2011) score of at least 3 [14], and total affected body surface area of at least 10%. Exclusion criteria included active, ongoing inflammatory diseases; active, ongoing, chronic, or recurrent infectious disease, or evidence of tuberculosis infection; or an underlying condition significantly immunocompromising the patient and/or placing the patient at unacceptable risk for receiving an immunomodulatory therapy (e.g., lymphoproliferative disease, malignancy, history of malignancy within the past 5 years; past medical history of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B, or hepatitis C).

Study Designs and Assessments

Patients received secukinumab (300 or 150 mg) at baseline, weeks 1, 2, and 3, and then every 4 weeks from week 4–48, or etanercept (50 mg) twice weekly for 12 weeks and then once weekly (in FIXTURE). In all studies, the coprimary endpoints were PASI 75 and IGA mod 2011 responses of 0/1 (clear/almost clear) at week 12. Secondary endpoints included PASI 90 and PASI 100 response rates at week 12.

Pooled Analysis Design and Statistical Methods

Data up to week 52 of the ERASURE, FIXTURE, FEATURE, and JUNCTURE studies were pooled. Patients who self-identified as being ethnically Hispanic were included in the Hispanic subgroup of this analysis. Missing values were handled by multiple imputation (MI) in which missing data are replaced by values derived from large data sets of possible values. The statistical analysis software MI procedure was used to generate data sets for 500 imputations. For comparison of secukinumab to etanercept, the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test was used. For comparison of response to secukinumab treatment between Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients, the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test was used, with adjustments made for study site, weight, and treatment group. The safety set included all patients who took at least one dose of study drug during the treatment period. No adjustment was made for multiple comparisons. All analyses were exploratory and for hypothesis generation.

Results

Subjects

Hispanic patients accounted for 13.9% (237/1709) of the pooled study population. In the US and non-US populations, Hispanic patients accounted for 15.3% (46/301) and 13.6% (191/1408) of the pooled study population, respectively. The numbers of Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients from each country in this study are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Demographic and baseline disease characteristics were generally well balanced between Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients (Table 1). Baseline PASI scores were numerically greater in Hispanic patients (24.8–29.2) compared with non-Hispanic patients (22.1–22.4). Additionally, more Hispanic patients had severe psoriasis as measured by IGA mod 2011 scores of 4 compared with non-Hispanic patients (40–49% vs 36–39%). Cardiac disorders (2.5–5.0% vs 0–1.1%) and depression (5.5–8.7% vs 3.1–3.9%) were more common in non-Hispanic patients than Hispanic patients. Rates of previous exposure to biologic psoriasis therapies were similar in Hispanic patients (12–25%) and non-Hispanic patients (14–24%).

Table 1.

Patient demographic and baseline disease characteristics

| Characteristics | Hispanic subgroup | Non-Hispanic subgroup | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secukinumab 300 mg (n = 89) | Secukinumab 150 mg (n = 97) | Etanercept (n = 51) | Secukinumab 300 mg (n = 602) | Secukinumab 150 mg (n = 595) | Etanercept (n = 275) | |

| Age (years) | 44.4 ± 12.6 | 45.5 ± 13.7 | 42.2 ± 12.5 | 45.0 ± 13.4 | 45.1 ± 13.3 | 44.0 ± 13.0 |

| Male, n (%) | 55 (61.8) | 67 (69.1) | 35 (68.6) | 422 (70.1) | 418 (70.3) | 197 (71.6) |

| Weight (kg) | 85.7 ± 24.5 | 82.0 ± 18.2 | 81.4 ± 17.7 | 86.7 ± 23.0 | 87.4 ± 23.8 | 85.1 ± 21.0 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.5 ± 7.1 | 29.8 ± 6.0 | 28.4 ± 4.8 | 29.2 ± 6.8 | 29.3 ± 7.2 | 28.8 ± 6.1 |

| Time since diagnosis of psoriasis (years) | 13.7 ± 9.3 | 15.0 ± 11.3 | 15.7 ± 11.5 | 17.5 ± 12.3 | 18.4 ± 12.6 | 16.6 ± 12.1 |

| PASI scores | 25.7 ± 11.8 | 24.8 ± 9.6 | 29.2 ± 11.9 | 22.2 ± 8.9 | 22.4 ± 10.0 | 22.1 ± 9.0 |

| IGA mod 2011, n (%) | ||||||

| Moderate | 48 (53.9) | 58 (59.8) | 26 (51.0) | 388 (64.5) | 381 (64.0) | 169 (61.5) |

| Severe | 41 (46.1) | 39 (40.2) | 25 (49.0) | 214 (35.5) | 214 (36.0) | 106 (38.5) |

| BSA involved (%) | 36.3 ± 18.9 | 35.2 ± 17.0 | 41.7 ± 18.1 | 32.5 ± 18.7 | 33.0 ± 19.2 | 32.1 ± 17.6 |

| Psoriatic arthritis, n (%) | 10 (11.2) | 16 (16.5) | 4 (7.8) | 120 (19.9) | 104 (17.5) | 40 (14.5) |

| Diabetesa, n (%) | 8 (9.0) | 10 (10.3) | 6 (11.8) | 57 (9.5) | 53 (8.9) | 21 (7.6) |

| Cardiac disorders, n (%) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 24 (4.0) | 30 (5.0) | 7 (2.5) |

| Depression, n (%) | 3 (3.4) | 3 (3.1) | 2 (3.9) | 41 (6.8) | 52 (8.7) | 15 (5.5) |

| Previous treatment, n (%) | ||||||

| Conventional systemic agents | 54 (60.7) | 61 (62.9) | 33 (64.7) | 319 (53.0) | 332 (55.8) | 171 (62.2) |

| Biologic agents | 22 (24.7) | 20 (20.6) | 6 (11.8) | 124 (20.6) | 141 (23.7) | 39 (14.2) |

Unless otherwise noted, values are mean ± SD

BMI body mass index, BSA body surface area, IGA mod 2011 Investigator’s Global Assessment 2011 modified version, PASI Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, SD standard deviation

aIncludes ongoing complicated and uncomplicated diabetes

Efficacy

At week 12, secukinumab 300 mg demonstrated greater efficacy than etanercept in both Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients for all measured efficacy outcomes (Table 2). In non-Hispanic patients, secukinumab 150 mg provided greater efficacy responses compared with etanercept for all measured efficacy responses. In Hispanic patients, PASI 90 and IGA mod 2011 0/1 response rates were greater with secukinumab 150 mg compared with etanercept. Overall, greater efficacy was observed in Hispanic patients at week 12 than in non-Hispanic patients when adjustments were made for study site, weight, and treatment group (Table 3).

Table 2.

Efficacy outcomes at week 12

| End point, n/N (%) | Hispanic subgroup | Non-Hispanic subgroup | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secukinumab 300 mg | Secukinumab 150 mg | Etanercept | Secukinumab 300 mg | Secukinumab 150 mg | Etanercept | |

| PASI 75 | 80/86 (92.6)* | 80/97 (82.8) | 35/50 (69.2) | 495/600 (82.4)† | 426/592 (71.9)† | 120/273 (43.8) |

| PASI 90 | 61/86 (70.6)† | 58/97 (59.5)* | 16/50 (31.2) | 348/600 (58.0)† | 244/592 (41.2)† | 58/273 (21.2) |

| PASI 100 | 31/86 (35.9)‡ | 24/97 (25.1) | 5/50 (9.8) | 168/600 (28.1)† | 79/592 (13.4)¶ | 14/273 (5.0) |

| IGA mod 2011 0/1 | 65/86 (75.6)¶ | 64/97 (65.9)* | 22/50 (44.8) | 409/600 (68.2)† | 318/593 (53.5)† | 74/273 (27.0) |

Significance was determined by the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test. Missing values were handled by multiple imputation

IGA mod 2011 0/1 Investigator’s Global Assessment, 2011 modified version, improvement to scores of 0 or 1 (clear or almost clear skin), PASI 75/90/100 Psoriasis Area and Severity Index 75%/90%/100% improvement from baseline

* P < 0.05 for the comparison with etanercept

† P ≤ 0.0001 for the comparison with etanercept

‡ P < 0.01 for the comparison with etanercept

¶ P < 0.001 for the comparison with etanercept

Table 3.

Effect of ethnicity on efficacy at week 12 (Hispanic vs non-Hispanic)

| Response criteria | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| PASI 75 | 1.97 (1.37–2.83) |

| PASI 90 | 1.74 (1.29–2.36) |

| PASI 100 | 1.68 (1.18–2.39) |

| IGA mod 2011 0/1 | 1.62 (1.20–2.19) |

Odds ratios were determined by the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test, with adjustment made for study site, weight, and treatment group

CI confidence interval, IGA mod 2011 0/1 Investigator’s Global Assessment 2011 modified version, improvement to scores of 0 or 1 (clear or almost clear skin), PASI 75/90/100 Psoriasis Area and Severity Index 75%/90%/100% improvement from baseline

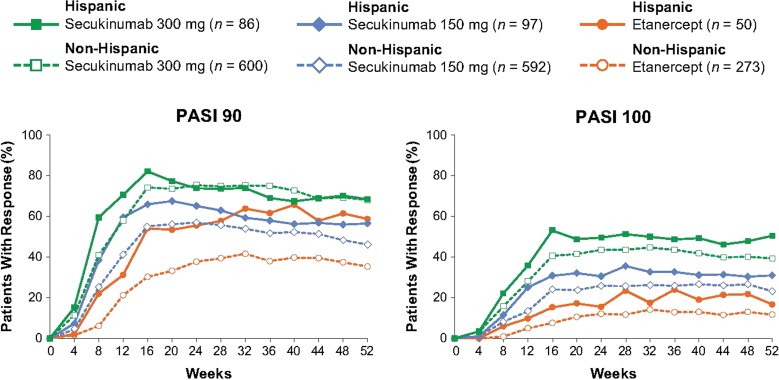

In both Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients, peak efficacy responses for secukinumab were observed at week 16 and were maintained to week 52 (Fig. 2). At week 16, secukinumab 300 mg provided the greatest efficacy with PASI 90 and PASI 100 responses being achieved by 82.1% and 53.1% of Hispanic patients, respectively, and by 74.2% and 40.6% of non-Hispanic patients, respectively. In comparison, PASI 90 and PASI 100 response rates with etanercept at week 16 were 54.1% and 15.3% in Hispanic patients, respectively, and 30.2% and 7.6% in non-Hispanic patients, respectively. Efficacy responses were well maintained to week 52, with both secukinumab 300 mg and secukinumab 150 mg in Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients. Differences between treatment groups were most pronounced for PASI 100 responses, and inspection of the response curves to week 52 shows a clear separation between treatment groups in Hispanic patients.

Fig. 2.

Efficacy over time for Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients. n represents the number of evaluable subjects. Missing values were handled by multiple imputation. PASI 90/100 Psoriasis Area and Severity Index 90%/100% improvement from baseline

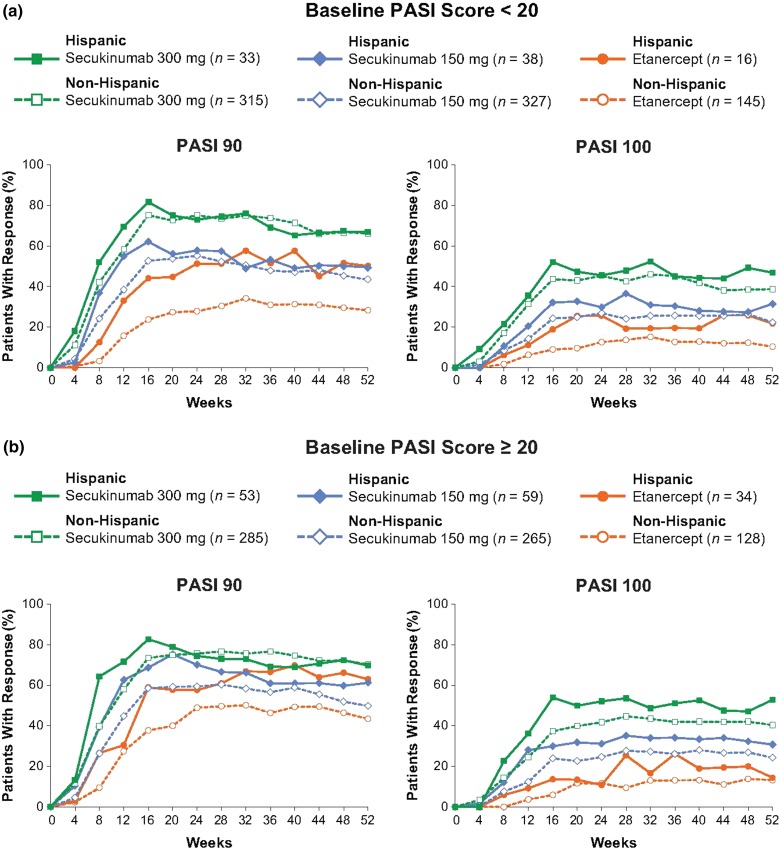

Secukinumab also provided robust efficacy in patients with the most severe levels of psoriasis (PASI ≥20) at baseline (Fig. 3). The speed of onset and maintenance of response in these patients were similar to those in the overall pooled population and patients with baseline PASI less than 20.

Fig. 3.

Efficacy over time by baseline PASI score a <20 and b ≥20 for Hispanic and Non-Hispanic patients. n represents the number of evaluable subjects. Missing values were handled by multiple imputation. PASI 90/100 Psoriasis Area and Severity Index 90%/100% improvement from baseline

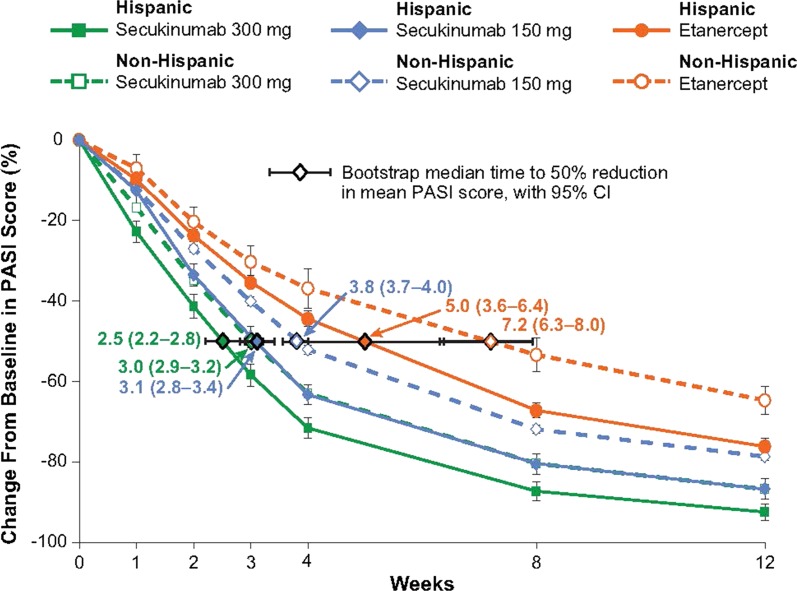

Both Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients responded rapidly to treatment with secukinumab (Fig. 4). The median time to a 50% decrease in baseline PASI score was achieved more rapidly in Hispanic patients than in non-Hispanic patients for each treatment group. Additionally, in both subgroups, the median time to a 50% decrease in baseline PASI score was reached first with secukinumab 300 mg (2.5–3.0 weeks), followed by secukinumab 150 mg (3.1–3.8 weeks), and then etanercept (5.0–7.2 weeks).

Fig. 4.

Speed of response in Hispanic and non-Hispanic Patients. A repeated-measures, mixed-effects model was used to analyze the mean percentage change from baseline in PASI score. The median time to a 50% reduction in mean PASI score was estimated from parametric bootstrap samples with the use of linear interpolation between time points. PASI Psoriasis Area and Severity Index

Secukinumab treatment improved patient QoL as measured by DLQI (Table 4). Improvements were observed at week 12 with both doses of secukinumab and these improvements were maintained to week 52. Both Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients experienced similar decreases in mean DLQI scores from baseline to week 12 and week 52. Additionally, DLQI 0/1 response rates were similar between Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients treated with secukinumab. At week 52, 70% and 65% of Hispanic patients treated with secukinumab 300 mg and secukinumab 150 mg, respectively, achieved DLQI scores of 0/1 compared with 68% and 52% of non-Hispanic patients treated with secukinumab 300 mg and secukinumab 150 mg, respectively. In the non-Hispanic subgroup, the proportion of individuals achieving DLQI scores of 0/1 after treatment with secukinumab 300 mg or secukinumab 150 mg at week 12 and week 52 was greater compared with the proportion of patients receiving etanercept who achieved this level of improvement in QoL.

Table 4.

Quality-of-life outcomes

| Hispanic subgroup | Non-Hispanic subgroup | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secukinumab 300 mg | Secukinumab 150 mg | Etanercept | Secukinumab 300 mg | Secukinumab 150 mg | Etanercept | |

| DLQI, mean score | ||||||

| Baseline | 13.2 | 13.1a | 12.0 | 13.6a | 13.1 | 13.6 |

| Week 12 (absolute change) | 2.4 (−10.9) | 2.7 (−10.4) | 3.3 (−8.7) | 2.7 (−10.9) | 3.6 (−9.5) | 5.9 (−7.7) |

| Week 52 (absolute change) | 2.1 (−11.2) | 3.2 (−9.8) | 2.7 (−9.3) | 2.5 (−11.0) | 4.0 (−9.1) | 5.0 (−8.6) |

| DLQI 0/1 response, n/N (%) | ||||||

| Week 12 | 51/86 (59.3) | 56/94 (59.6) | 24/50 (48.0) | 348/592 (58.8)* | 286/589 (48.6)* | 86/269 (32.0) |

| Week 52 | 60/86 (69.8) | 62/95 (65.3) | 30/50 (60.0) | 403/596 (67.6)* | 305/589 (51.8)† | 120/270 (44.4) |

For mean DLQI scores, only patients with a value at both baseline and the respective post-baseline visit are included for each post-baseline visit value. Significance was determined by logistic regression, with adjustment made for baseline DLQI, study site, and weight

DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index

* P ≤ 0.0001 for the comparison with etanercept

† P = 0.019 for the comparison with etanercept

a As a result of differences in the number of patients with values at week 12 and week 52, baseline scores are shown for patients with values at week 12. Baseline scores for patients with values at week 52 were 13.0 for Hispanic patients receiving secukinumab 150 mg and 13.5 for non-Hispanic patients receiving secukinumab 300 mg

Safety

The safety profile of secukinumab was favorable in both Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients (Table 5). Through week 52, the rates of adverse events (AEs), serious adverse events (SAEs), and discontinuations because of AEs were similar across treatment groups and between the Hispanic and non-Hispanic subgroups. Differences were observed in the rates of influenza and nasopharyngitis between Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients. However, when all respiratory infections were considered together, similar rates were observed in Hispanic (36–46%) and non-Hispanic (38–41%) patients receiving secukinumab. In the Hispanic patient subgroup, SAEs were reported in 2 patients receiving secukinumab 300 mg (overdose and uterine leiomyoma), 4 patients receiving secukinumab 150 mg (cholelithiasis, ischemic stroke, thyroid cancer, and sixth nerve paralysis), and 2 patients receiving etanercept (acute cholecystitis and clavicle fracture). The mean number of days for exposure to study treatment was similar in all treatment groups.

Table 5.

Adverse events in the Hispanic and Non-Hispanic population through week 52

| Variablea | Hispanic subgroup | Non-Hispanic subgroup | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secukinumab 300 mg (n = 88) | Secukinumab 150 mg (n = 97) | Etanercept (n = 51) | Secukinumab 300 mg (n = 602) | Secukinumab 150 mg (n = 595) | Etanercept (n = 272) | |

| Mean exposure to study treatment (days ± SD) | 333.7 ± 90.4 | 338.5 ± 80.9 | 329.0 ± 98.0 | 344.8 ± 69.9 | 336.2 ± 80.0 | 332.5 ± 88.2 |

| Serious adverse event | 2 (2.3) | 4 (4.1) | 2 (3.9) | 46 (7.6) | 44 (7.4) | 18 (6.6) |

| Any adverse event | 70 (79.5) | 78 (80.4) | 42 (82.4) | 505 (83.9) | 484 (81.3) | 211 (77.6) |

| Discontinuations because of adverse events | 4 (4.5) | 4 (4.1) | 2 (3.9) | 17 (2.8) | 21 (3.5) | 10 (3.7) |

| Most common adverse events | ||||||

| Headache | 15 (17.0) | 11 (11.3) | 10 (19.6) | 64 (10.6) | 54 (9.1) | 30 (11.0) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 14 (15.9) | 11 (11.3) | 4 (7.8) | 158 (26.2) | 153 (25.7) | 82 (30.1) |

| Diarrhea | 12 (13.6) | 10 (10.3) | 3 (5.9) | 42 (7.0) | 35 (5.9) | 19 (7.0) |

| Influenza | 11 (12.5) | 15 (15.5) | 4 (7.8) | 16 (2.7) | 11 (1.8) | 7 (2.6) |

| Pharyngitis | 9 (10.2) | 5 (5.2) | 3 (5.9) | 9 (1.5) | 14 (2.4) | 3 (1.1) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 5 (5.7) | 8 (8.2) | 2 (3.9) | 48 (8.0) | 56 (9.4) | 16 (5.9) |

Adverse events that occurred in >5% of patients from both the Hispanic and non-Hispanic secukinumab treatment subgroups were included. Most common adverse events are sorted in descending order of frequency for the Hispanic secukinumab 300-mg subgroup

SD standard deviation

a n (%) unless otherwise noted

Discussion

There are few studies that have evaluated the use of biologic therapies in Hispanic patients with psoriasis. Further, the incidence and characteristics of Hispanic patients with psoriasis are not well documented, especially outside of the USA. It has been reported that those who self-identify as Hispanic from the USA are less inclined to seek care from a dermatologist for skin problems [11]. It is unlikely that this finding is accurate for those of Hispanic descent outside of the USA because rates of previous biologic exposure in this analysis were similar in both Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients.

In this pooled analysis of four phase 3 trials of patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis, secukinumab demonstrated robust and sustained efficacy with a good safety profile in Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients. These findings are similar to prior reports on the efficacy of secukinumab over 52 weeks and support the use of secukinumab in both subgroups at the preferred dose of 300 mg [3, 7]. Although baseline characteristics were generally similar between the two subgroups, Hispanic patients tended to respond better to secukinumab than non-Hispanic patients, especially for measures of complete skin clearance. A similar trend was observed with etanercept, and evaluation of response to treatment between Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients found that Hispanic patients were more likely to respond to psoriasis therapy when adjustments were made for study site, weight, and treatment group.

In a previous study, numerically greater improvements in DLQI were reported for Hispanic patients treated with etanercept for 12 weeks [13]. At week 12 in this study, etanercept improved baseline DLQI scores by 8.7 in Hispanic patients and by 7.7 in non-Hispanic patients. In the present study, improvements in baseline DLQI scores were similar between Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients with secukinumab 300 mg at week 12 (10.9 for both groups) and week 52 (11.2 vs 11.0). Overall, secukinumab provided both Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients with improvements in DLQI at week 12 that were sufficient to meet the definition (total DLQI score change of at least 5) required for a minimal clinically important difference in patients with psoriasis receiving biologic therapy [15].

Similar efficacy for secukinumab was observed between the overall population and in patients with baseline PASI scores of at least 20, who accounted for 48% of evaluable patients, indicating that secukinumab is effective regardless of disease severity, as previously reported [16]. Further, high response rates can be expected in patients with the most severe levels of psoriasis. Responses to secukinumab were rapid in both Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients. Skin clearance was observed as early as week 1 and a 50% reduction in PASI scores was observed after 3.0 weeks with secukinumab 300 mg and 3.8 weeks with secukinumab 150 mg in non-Hispanic patients. The response to secukinumab was quicker in Hispanic patients who achieved a 50% reduction in PASI scores after 2.5 weeks with secukinumab 300 mg and 3.1 weeks with secukinumab 150 mg. In both Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients, responses were more rapid with either dose of secukinumab than with etanercept, which provided a 50% reduction in PASI scores after 5.0 weeks in Hispanic patients and 7.2 weeks in non-Hispanic patients.

The safety profile of secukinumab was favorable and similar in both Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients. Differences in rates of nasopharyngitis and influenza between the two subgroups may be caused by differences in diagnostic criteria between countries and when all respiratory infections are combined, similar rates are observed in both subgroups.

Historically, clinical trials for psoriasis have enrolled low proportions of Hispanic and other minority patients, and a limitation of this study is that Hispanic patients accounted for 16% of the overall pooled population. Further, most individuals of Hispanic descent prefer to identify themselves by their family’s country of origin [17]. For this analysis, only individuals that self-identified as being Hispanic were included in the Hispanic subgroup.

Conclusions

Secukinumab provided both Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis greater disease clearance than etanercept. The speed of onset with secukinumab was rapid and patients also saw improvement in DLQI. Although greater responses were observed in Hispanic patients, this pooled analysis of four phase 3 trials showed that secukinumab is effective and safe in both Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Previously presented in part at the American Academy of Dermatology Summer Meeting, New York, NY, USA, August 19–23, 2015. This study was funded by Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation. Article processing charges and the fee for open access were funded by Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. Technical assistance with editing and styling of the manuscript for submission was provided by Scott Forbes, Ph.D., of Oxford PharmaGenesis Inc. and was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Disclosures

Sandra Adsit: Clinical investigator for Allergan, Intrepid Therapeutics, PromiusPharma, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Dusa Pharmaceuticals, Cosmederm Bioscience, Samumed, Sandoz, Novartis, Viamet Pharmaceuticals, Thesan Pharmaceuticals, Therapeutics, Watson Laboratories, Maruho, Lilly, Precision Dermatology, Actavis Laboratories, DX Biosciences, Taro Pharmaceuticals, Amgen, Lithera, Bavarian Nordic, Dermata, and Dow/Valeant; consultant for Samumed. Enrique Rivas Zaldivar: Clinical investigator for Novartis. Howard Sofen: Clinical investigator for Boehringer-Ingelheim, Novartis, Pfizer, Janssen, Lilly, Amgen, and Merck; consultant and member of the speakers’ bureau for Novartis, Janssen, and Lilly. Ignacio Dei-Cas: Clinical investigator, consultant, and member of the speakers’ bureau for Novartis; received grants from Pfizer and Janssen. César Maldonado-García: Clinical investigator for AbbVie, Novartis; consultant and/or member of the speakers’ bureau for AbbVie, Novartis, Leo-Pharma, and Lilly. Elkin O. Peñaranda: Clinical investigator for Novartis. Luís Puig: Clinical investigator for AbbVie, Amgen, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Regeneron, and Roche; consultant and/or member of the speakers bureau for AbbVie, Amgen, Baxalta, Biogen, Boehringer, Celgene, Janssen, Leo-Pharma, Lilly, Merck-Serono, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sandoz, and Sanofi. Xiangyi Meng is an employee and stockholder of Novartis. Todd Fox is an employee and stockholder of Novartis. Adriana Guana is an employee and stockholder of Novartis. Technical assistance with editing and styling of the manuscript for submission was provided by Scott Forbes, Ph.D., of Oxford PharmaGenesis Inc. and was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

The original version of this article was revised: The fifth author’s name was incorrectly published as Ce´sar Maldonado García. The correct name should read as “César Maldonado-García”

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to www.medengine.com/Redeem/E508F06045F9BBE6.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12325-017-0563-2.

References

- 1.Kirkham BW, Kavanaugh A, Reich K. Interleukin-17A: a unique pathway in immune-mediated diseases: psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Immunology. 2014;141:133–142. doi: 10.1111/imm.12142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blauvelt A, Prinz JC, Gottlieb AB, et al. Secukinumab administration by pre-filled syringe: efficacy, safety, and usability results from a randomized controlled trial in psoriasis (FEATURE) Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:484–493. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis—results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:326–338. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paul C, Lacour JP, Tedremets L, et al. Efficacy, safety and usability of secukinumab administration by autoinjector/pen in psoriasis: a randomized, controlled trial (JUNCTURE) J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1082–1090. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mease PJ, McInnes IB, Kirkham B, et al. Secukinumab inhibition of interleukin-17A in patients with psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1329–1339. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McInnes IB, Mease PJ, Kirkham B, et al. Secukinumab, a human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriatic arthritis (FUTURE 2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2015;386:1137–1146. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cosentyx (secukinumab) [prescribing information]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2015.

- 8.Cosentyx (secukinumab) [summary of product characteristics]. Camberley, UK: Novartis Europharm Limited. European Medicines Agency.

- 9.Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, Ashcroft DM, Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377–385. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:512–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, Huang W, Pichardo-Geisinger RO, McMichael AJ. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ennis SR, Rios-Vargas M, Albert NG. The Hispanic population: 2010 census briefs. 2011. http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf. Accessed 8 July 2016.

- 13.Shah SK, Arthur A, Yang YC, Stevens S, Alexis AF. A retrospective study to investigate racial and ethnic variations in the treatment of psoriasis with etanercept. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:866–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langley RG, Feldman SR, Nyirady J, van de Kerkhof P, Papavassilis C. The 5-point Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) Scale: a modified tool for evaluating plaque psoriasis severity in clinical trials. J Dermatol Treat. 2015;26:23–31. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2013.865009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katugampola RP, Lewis VJ, Finlay AY. The Dermatology Life Quality Index: assessing the efficacy of biological therapies for psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:945–950. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spelman LJ, Blauvelt A, Loffler J, Papavassilis C, Fox T. Secukinumab shows efficacy regardless of baseline disease severity in subjects with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a pooled analysis from four phase 3 studies. In: Presented at the annual European academy of dermatology and venereology, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 8–12 Oct 2014.

- 17.Taylor P, Hugo Lopez M, Martínez J, Velasco G. When labels don’t fit: Hispanics and their views of identity. 2012. http://www.pewhispanic.org/2012/04/04/when-labels-dont-fit-hispanics-and-their-views-of-identity/. Accessed 8 July 2016.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.