Abstract

Problem

To determine whether amniotic fluid (AF) CXCL10 concentration is associated with histologic chronic chorioamnionitis in patients with preterm labor (PTL) and preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes (PROM).

Method of Study

This study included 168 women who had an episode of PTL or preterm PROM. AF interleukin (IL)‐6 and CXCL10 concentrations were determined by immunoassay.

Results

(i) Increased AF CXCL10 concentration was associated with chronic (OR: 4.8; 95% CI: 1.7‐14), but not acute chorioamnionitis; (ii) increased AF IL‐6 concentration was associated with acute (OR: 4.2; 95% CI: 1.3‐13.7) but not chronic chorioamnionitis; and (iii) an increase in AF CXCL10 concentration was associated with placental lesions consistent with maternal anti‐fetal rejection (OR: 3.7; 95% CI: 1.3‐10.4). (iv) All patients with elevated AF CXCL10 and IL‐6 delivered preterm.

Conclusion

Increased AF CXCL10 concentration is associated with chronic chorioamnionitis or maternal anti‐fetal rejection, whereas increased AF IL‐6 concentration is associated with acute histologic chorioamnionitis.

Keywords: allograft, amniocentesis, biomarker, chorioamnionitis, chronic inflammation, cytokine, maternal anti‐fetal rejection

1. Introduction

Preterm labor is a syndrome characterized by the combination of increased uterine contractility, cervical remodeling (ie, ripening and dilatation), and decidual membrane activation, caused by multiple pathologic processes.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 One of the mechanisms of disease implicated in preterm parturition is a breakdown of immune tolerance, which may evolve into maternal anti‐fetal rejection.13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30

The fetus and placenta express both maternal and paternal antigens; therefore, they are semiallografts.31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42 The placenta is considered to be the most successful transplant in nature, a biological adaptation accomplished by immune tolerance.43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48 Tolerance is a specific immunological term that refers to “the active state of antigen‐specific non‐responsiveness”49 leading to diminished reactivity to paternal antigens expressed by the placenta and/or fetus; it is considered key for successful pregnancy.31, 33, 39, 40, 50, 51, 52, 53 The mechanisms responsible for tolerance in pregnancy include the following: (i) T‐cell chemokine gene silencing in the decidual cells;54 (ii) a suppressive role of regulatory T cells;52, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64 (iii) expression of non‐classical major histocompatibility complex molecules on trophoblast cells that do not elicit a maternal immune response;65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70 (iv) changes in tryptophan catabolisms;71, 72, 73, 74, 75 (v) T‐cell apoptosis;76, 77 (vi) complement;78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90 and (vii) costimulatory molecules such as the programmed death ligand.91, 92, 93 Other mechanisms for tolerance are not currently understood. The interested reader is referred to recent contributions by Sing Sing Way's laboratory28, 39, 94, 95, 96 and Adrian Erlebacher.31, 42, 53

In transplantation medicine, failure of tolerance is responsible for graft rejection characterized by an infiltration of the recipient's CD8+ (cytotoxic) T cells into the graft and an overexpression of C‐X‐C motif chemokine 10 (CXCL10), a marker of allograft rejection.97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102 In obstetrics, rejection as a mechanism of disease has been largely overlooked. However, recent evidence suggests that maternal anti‐fetal rejection is operative in a subset of patients with spontaneous preterm labor,15, 16, 20, 26, 103 preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes (PROM),20 fetal death,17, 25 recurrent abortion,19 and other obstetrical syndromes.14, 18, 21, 22, 23, 24, 103 Maternal lymphocytes (akin to a transplant recipient) can infiltrate the chorioamniotic membranes (fetal tissue or semiallograft), lead to chronic chorioamnionitis,15, 26 and induce trophoblast apoptosis, which, when excessive, can result in graft failure (eg, membrane rupture or activation of the decidual membrane and the initiation of labor).15, 104 The chemotactic signal inducing the migration of maternal T lymphocytes into the chorioamniotic membranes appears to be present in the amniotic cavity. One such chemokine is CXCL10,15, 104, 105 and an increased concentration of this chemokine in the amniotic fluid has been characterized by our group to represent a distinct form of intra‐amniotic inflammation, which is associated with chronic inflammatory lesions of the placenta and a novel form of fetal inflammatory response syndrome (FIRS) or FIRS type 2.21

This distinct form of intra‐amniotic inflammation differs from the intra‐amniotic inflammatory process observed in patients with preterm labor due to microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity (MIAC). Microorganisms and their products can induce a robust intra‐amniotic inflammatory response characterized by an elevation in amniotic fluid interleukin (IL)‐6 concentration,106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130 and neutrophil chemokines, such as IL‐8,111, 112, 113, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140 as well as other inflammatory mediators capable of inducing the onset of labor.118, 135, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163, 164, 165, 166, 167, 168, 169, 170, 171, 172, 173, 174, 175, 176, 177, 178, 179, 180 Recently, we provided an analysis of the protein inflammatory network for this condition.181 The histologic hallmark of MIAC is acute histologic chorioamnionitis, defined by the infiltration of maternal neutrophils into the chorioamniotic membranes.109, 182, 183, 184, 185, 186, 187, 188, 189, 190, 191, 192, 193, 194, 195, 196 Related lesions are chorionic vasculitis197 and the spectrum of lesions observed in cases of funisitis.155, 196, 198, 199, 200, 201, 202, 203, 204 Therefore, at this time, at least two major types of intra‐amniotic inflammation appear to occur in the context of spontaneous preterm labor—one associated with MIAC or induced by danger signals124, 205, 206, 207, 208, 209 and the other associated with chronic inflammatory lesions of the placenta (often attributed to maternal anti‐fetal rejection).

The concentration of the T‐cell chemokine CXCL10 (IP‐10) is considered a marker for chronic inflammatory lesions associated with allograft rejection and chronic chorioamnionitis in the case of pregnancy. In contrast, IL‐6, IL‐8, IL‐1, and TNF‐α are examples of cytokines involved in acute inflammatory lesions of the placenta.109, 128, 130, 196, 210

The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence and clinical significance of an elevated CXCL10 concentration in the amniotic fluid of patients with a diagnosis of either preterm labor with intact membranes or preterm PROM and whether an elevation in CXCL10 concentration is associated with chronic chorioamnionitis, as an increased concentration of IL‐6 and CXCL10 is frequently observed in patients with intra‐amniotic infection and acute histologic chorioamnionitis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study population

A nested retrospective cohort study was conducted by searching the clinical database and Bank of Biological Materials of Wayne State University, the Detroit Medical Center, and the Perinatology Research Branch of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (Detroit, MI) to identify patients with a diagnosis of spontaneous preterm labor with intact membranes or preterm PROM. Patients were included if they met the following criteria: (i) singleton gestation; (ii) episode of preterm labor and intact or ruptured membranes; and (iii) transabdominal amniocentesis performed between 20 and 35 weeks of gestation for microbiological studies. Patients were excluded if chromosomal or structural fetal anomalies or placenta previa was present. All patients provided written informed consent. The use of biological specimens and clinical data for research purposes was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of NICHD and Wayne State University.

2.2. Biological samples and analysis

Amniotic fluid was transported in a capped sterile syringe to the clinical laboratory where it was cultured for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, including genital mycoplasmas. Evaluations of the white blood cell count, glucose concentration, and Gram stain of the amniotic fluid were performed shortly after collection. Amniotic fluid was centrifuged at 1300 g for 10 minutes at 4°C shortly after collection and stored at −70°C until analysis. Concentrations of IL‐6 and CXCL10 in the amniotic fluid (ng/mL) were determined by the enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay test, using immunoassays obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). The assay time, volume, and other characteristics for each method have been previously described.15, 123, 124, 169, 205, 206, 207

2.3. Clinical definitions

Gestational age was determined by the last menstrual period and confirmed by ultrasound examination, or by ultrasound examination alone if the sonographic determination of gestational age was not consistent with menstrual dating.211 Preterm labor was diagnosed by the presence of at least two regular uterine contractions every 10 minutes in association with cervical changes in patients with a gestational age between 20 and 36 6/7 weeks that led to preterm delivery (defined as birth prior to the 37th week of gestation). Preterm PROM was diagnosed by a sterile speculum examination with documentation of the pooling of amniotic fluid in the vagina in association with a positive nitrazine test and/or positive ferning test when necessary. Elevated amniotic fluid IL‐6 concentration (≥2.6 ng/mL) was used to define intra‐amniotic inflammation.176, 205, 206, 207, 208, 212, 213, 214, 215 MIAC was defined as a positive amniotic fluid culture. Intra‐amniotic infection was defined as the combination of MIAC and intra‐amniotic inflammation. An elevated amniotic fluid CXCL10 concentration as a marker of subclinical intra‐amniotic inflammation was defined as ≥2.2 ng/mL, which is above the 95th percentile among patients with uncomplicated term deliveries.169

The diagnosis of acute histologic chorioamnionitis was based on the presence of acute inflammatory changes in the extraplacental chorioamniotic membrane roll and/or chorionic plate of the placenta, using the criteria previously described.188, 189, 190, 192, 196, 216, 217 The grading and staging of placental lesions consistent with amniotic fluid infection was defined according to the Amniotic Fluid Infection Nosology Committee of the Perinatal Section of the Society for Pediatric Pathology as reported by Redline et al.188 Acute funisitis was defined as the presence of neutrophils in the wall of the umbilical vessels and/or Wharton's jelly.188, 196, 197 Chronic placental inflammatory lesions included the following: (i) chronic chorioamnionitis; (ii) villitis of unknown etiology (VUE); and (iii) chronic deciduitis. Chronic chorioamnionitis was diagnosed when lymphocytic infiltration into the chorionic trophoblast layer or chorioamniotic connective tissue was observed.14, 15, 26, 218 VUE was defined as the presence of lymphohistiocytic infiltration, in varying proportion, of the placental villous tree.14, 219 Chronic deciduitis was diagnosed as the presence of lymphocytic infiltration into the decidua of the basal plate.220 Lesions consistent with maternal anti‐fetal rejection proposed by our group included chronic chorioamnionitis, VUE, or chronic deciduitis with plasma cells.14, 16

2.4. Study groups

Participants were allocated into four study groups, according to whether they had an increase in amniotic fluid CXCL10 concentration and/or an increase in amniotic fluid IL‐6 concentration: (i) normal amniotic fluid IL‐6 and CXCL10 concentrations; (ii) an isolated increase in amniotic fluid IL‐6 concentration; (iii) an isolated increase in amniotic fluid CXCL10 concentration; and (iv) an increase in both amniotic fluid IL‐6 and CXCL10 concentrations. The cutoff has been derived from previous studies.109, 111, 169

2.5. Study outcomes

The primary outcome of this study was the presence or absence of acute or chronic chorioamnionitis, defined as (i) the absence of both acute and chronic chorioamnionitis; (ii) acute chorioamnionitis ≥stage 2 in the absence of chronic chorioamnionitis; (iii) chronic chorioamnionitis in the absence of acute histologic chorioamnionitis ≥stage 2; and (iv) the presence of both acute (≥stage 2) and chronic chorioamnionitis. The presence of placental lesions associated with maternal anti‐fetal rejection was examined as a secondary outcome.217

2.6. Statistical analysis

The Kolmogorov‐Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of arithmetic data distributions. The Kruskal‐Wallis test and the Mann‐Whitney U test were used to make comparisons among and between groups for arithmetic variables. The chi‐square test or Fisher's exact test was used for comparisons of proportions. Multinomial logistic regression models were fit to examine magnitudes of association with primary and secondary outcomes, adjusting for gestational age at amniocentesis. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA). Confidence intervals (95% CI) that do not include the null hypothesis (ie, an odds ratio [OR] of “1.0”) are considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical characteristics

One hundred and sixty‐eight women with either preterm labor with intact membranes (72%) or preterm PROM (28%) were included in this study. Table 1 displays the clinical characteristics of the participants; 88% were African American, 34% were nulliparous, and 83% delivered preterm (<37 weeks of gestation). The median gestational age at amniocentesis was 30 weeks (interquartile range: 27‐32 weeks), and amniotic fluid cultures were positive in 20% of the study participants. Placental lesions associated with acute and chronic histologic chorioamnionitis and maternal anti‐fetal rejection were observed in 49% (82/168), 27% (45/168), and 41% (69/168) of the study population, respectively.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the study population

| Descriptive characteristics | Median (IQR) or % (n) |

|---|---|

| Maternal age (y) | 24.0 (20.3‐30.0) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.0 (21.0‐30.9) |

| Nulliparity (%) | 33.9% (57/168) |

| Gestational age at amniocentesis (wk) | 30.2 (26.6‐32.3) |

| African American ethnicity (%) | 88.1% (148/168) |

| Amniotic fluid WBC count (cells/mm3) | 3.5 (0‐39.3) |

| Amniotic fluid glucose (mg/dL) | 23.0 (10.0‐30.0) |

| Positive amniotic fluid culture (%) | 20.2% (34/168) |

| Amniocentesis‐to‐delivery interval (d) | 4 (1‐26.8) |

| Preterm delivery (%) | 83.3% (140/168) |

| Gestational age at delivery (wk) | 32.1 (27.7‐34.9) |

| Birthweight (g) | 1822.5 (1086.3‐2472.5) |

| Acute histologic chorioamnionitis (%) | 48.8% (82/168) |

| Chronic chorioamnionitis (%) | 26.8% (45/168) |

| Placental lesions associated with maternal anti‐fetal rejection (%)a | 41.1% (69/168) |

Data presented as median (IQR) or % (n).

IQR, interquartile range; WBC, white blood cell.

Placental lesions associated with maternal anti‐fetal rejection: chronic chorioamnionitis, villitis of unknown etiology (VUE), and chronic deciduitis with plasma cells.

3.2. Amniotic fluid CXCL10 and IL‐6 concentrations according to placental pathologic lesions and outcome of pregnancy

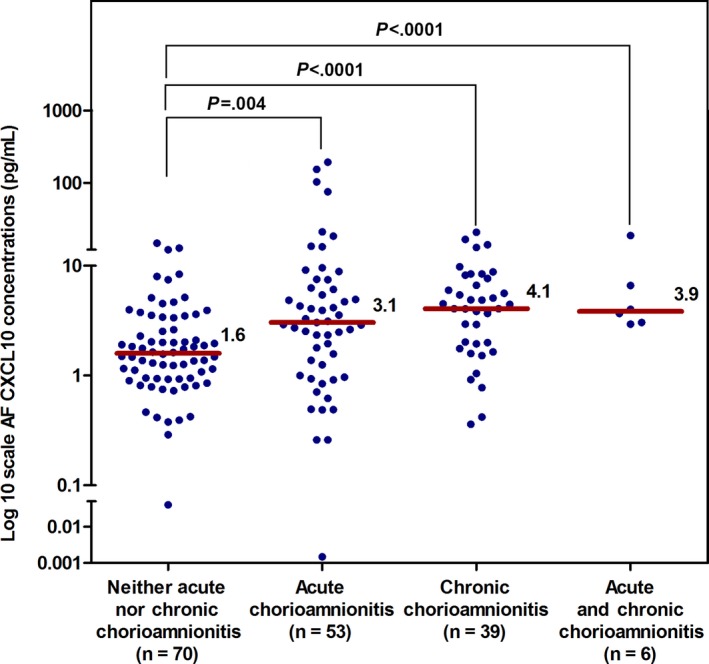

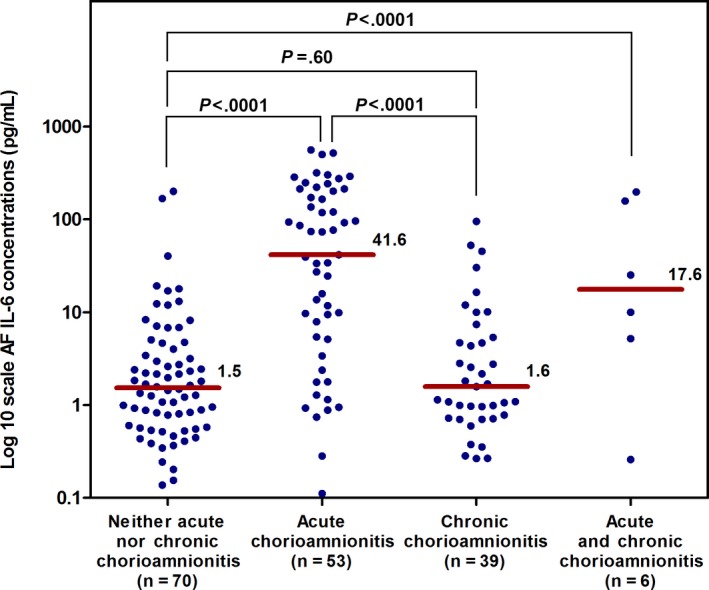

Amniotic fluid CXCL10 concentrations were highest in patients with chronic chorioamnionitis (Figure 1), whereas amniotic fluid IL‐6 concentrations were highest in patients with acute chorioamnionitis ≥stage 2 (Figure 2). Clinical characteristics and the prevalence of acute and chronic inflammatory placental lesions for the four study groups, defined according to the amniotic fluid CXCL10 and amniotic fluid IL‐6 concentrations, are shown in Table 2.

Figure 1.

The median concentration of AF CXCL10 in patients according to the presence or absence of acute chorioamnionitis (≥stage 2) or chronic chorioamnionitis. The median (interquartile range: IQR) concentration of AF CXCL10 (ng/mL) was highest in patients with chronic chorioamnionitis. The median (IQR) concentration of AF CXCL10 (ng/mL) was 1.6 (0.9‐3.4), 3.1 (1.1‐6.9), 4.1 (1.9‐7.7), and 3.9 (3.0‐9.7) in patients with neither acute chorioamnionitis nor chronic chorioamnionitis, acute chorioamnionitis (≥stage 2), chronic chorioamnionitis, and acute and chronic chorioamnionitis, respectively. AF, amniotic fluid; CXCL, C‐X‐C motif chemokine; acute chorioamnionitis, the presence of acute chorioamnionitis ≥stage 2 in the absence of chronic chorioamnionitis; chronic chorioamnionitis, the presence of chronic chorioamnionitis in the absence of acute chorioamnionitis ≥stage 2

Figure 2.

The median concentration of AF IL‐6 in patients with acute chorioamnionitis ≥stage 2 and/or chronic chorioamnionitis. The median (interquartile range: IQR) AF concentration of IL‐6 (ng/mL) was highest in patients with acute chorioamnionitis ≥stage 2. The median (IQR) AF concentration of IL‐6 (ng/mL) was 1.5 (0.6‐4.2), 41.6 (5.3‐20.7), 1.6 (0.7‐5.4), and 17.6 (3.9‐167.4) in patients with neither acute nor chronic chorioamnionitis, acute chorioamnionitis, chronic chorioamnionitis, or acute and chronic chorioamnionitis, respectively. AF, amniotic fluid; IL, interleukin; acute chorioamnionitis, the presence of acute chorioamnionitis ≥stage 2 in the absence of chronic chorioamnionitis; chronic chorioamnionitis, the presence of chronic chorioamnionitis in the absence of acute chorioamnionitis ≥stage 2; *P value <.05

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics and placental lesions according to amniotic fluid interleukin‐6 and CXCL10 concentrations

| Outcomes | Normal AF IL‐6 and CXCL10 (n=53) | Isolated increase in AF IL‐6 (n=26) | Isolated increase in AF CXCL10 (n=30) | Increase in both AF IL‐6 and CXCL10 (n=59) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA at amniocentesis (wk) | 31.3 (28.4‐32.7) | 30.6 (26.7‐32.4)a | 31.4 (29.4‐32.2)b | 26.9 (23.6‐30.7) |

| GA at delivery (wk) | 34.9 (32.0‐38.1) | 31.0 (27.1‐33.0)a | 34.1 (31.8‐36.5)b | 27.9 (24.3‐32.1) |

| Preterm delivery (83.3%; n=140/168) | 64.2% (34/53) | 93.3% (24/26)a | 76.7% (23/30)b | 100% (59/59) |

| Spontaneous preterm delivery within 48 h of amniocentesis (36.3%; n=61/168) | 20.8% (11/53) | 61.5% (16/26) | 20.0% (6/30)b | 47.5% (28/59) |

| Spontaneous preterm delivery before 34 wk of gestation (50.6%; n=85/168) | 30.2% (16/53) | 65.4% (17/26) | 26.7% (8/30)b | 74.6% (44/59) |

| Birthweight (g) | 2485 (1900‐2941) | 1557 (1008‐2119)a | 2210 (1701‐2743)b | 1155 (600‐1700) |

| Placental pathology | ||||

| No acute/chronic chorioamnionitis (41.7%; n=70/168) | 67.9% (36/53) | 50% (13/26)a | 36.7% (11/30)b | 16.9% (10/59) |

| Acute chorioamnionitis ≥stage 2 (31.5%; n=53/168) | 13.2% (7/53) | 42.3% (11/26) | 13.3% (4/30)b | 52.5% (31/59) |

| Chronic chorioamnionitis (23.2%; n=39/168) | 18.9% (10/53) | 7.7% (2/26) | 46.7% (14/30)b | 22.0% (13/59) |

| Acute (≥stage 2) and chronic chorioamnionitis (3.6%; n=6/168) | 0% (0/53) | 0% (0/26) | 3.3% (1/30) | 8.5% (5/59) |

| Acute funisitis (33.3%; n=56/168) | 17% (9/53) | 34.6% (9/26) | 20% (6/30)b | 54.2% (32/59) |

AF, amniotic fluid; CXCL, C‐X‐C motif chemokine; GA, gestational age; IL, interleukin; acute chorioamnionitis, the presence of acute chorioamnionitis ≥stage 2 in the absence of chronic chorioamnionitis; chronic chorioamnionitis, the presence of chronic chorioamnionitis in the absence of acute chorioamnionitis ≥stage 2.

Data presented as % (n) or median (interquartile). Normal AF IL‐6 and CXCL10 concentrations: IL‐6 <2.6 ng/mL and CXCL10 <2.2 ng/mL; isolated increase in AF IL‐6 concentrations: IL‐6 ≥2.6 ng/mL; isolated increase in AF CXCL10 concentrations: CXCL10 ≥2.2 ng/mL; increase in both AF IL‐6 and CXCL10 concentrations: IL‐6 ≥2.6 ng/mL and CXCL10 ≥2.2 ng/mL.

P<.05 for the comparison between the group of isolated increase in amniotic fluid IL‐6 concentration and the group of increase in both amniotic fluid IL‐6 and CXCL10 concentrations.

P<.05 for the comparison between the group of isolated increase in amniotic fluid CXCL10 concentration and the group of increase in both amniotic fluid IL‐6 and CXCL10 concentrations.

An elevation in the concentration of both amniotic fluid CXCL10 (≥2.2 ng/mL) and amniotic fluid IL‐6 (≥2.6 ng/mL) was observed in 35% (59/168) of the patients, whereas 18% (30/168) had an isolated elevation in the concentration of amniotic fluid CXCL10, 15% (26/168) had an isolated elevation in the concentration of amniotic fluid IL‐6, and 32% (53/168) did not have an elevation in amniotic fluid concentrations of either CXCL10 or IL‐6. All patients with elevated concentrations of both amniotic fluid CXCL10 and IL‐6 delivered before 37 weeks of gestation. By contrast, 93% (24/26) of patients with an isolated elevation in the concentration of amniotic fluid IL‐6 and 77% (23/30) of those with an isolated elevation in the concentration of amniotic fluid CXCL10 delivered preterm.

3.3. Acute and chronic chorioamnionitis in relationship to amniotic fluid concentrations of CXCL10 and IL‐6

The prevalence of chronic chorioamnionitis was highest in patients with an isolated elevation in amniotic fluid CXCL10 concentration (46.7%; 14/30) and was lowest in those with an isolated elevation in amniotic fluid IL‐6 concentration (7.7%; 2/26) (Table 2). In contrast, the prevalence of acute chorioamnionitis ≥stage 2 was highest in patients with an isolated elevation in both amniotic fluid IL‐6 and CXCL10 concentrations (52.5%; 31/59), followed by patients with an isolated elevation in amniotic fluid IL‐6 concentration (42.3%; 11/26). The prevalence of such placental lesions was observed in 13% (4/30) of patients with an isolated elevation in amniotic fluid CXCL10 concentration. Interestingly, almost all patients with acute and chronic chorioamnionitis (83.3%; 5/6) had an elevation in both amniotic fluid IL‐6 and CXCL10 concentrations (Table 2).

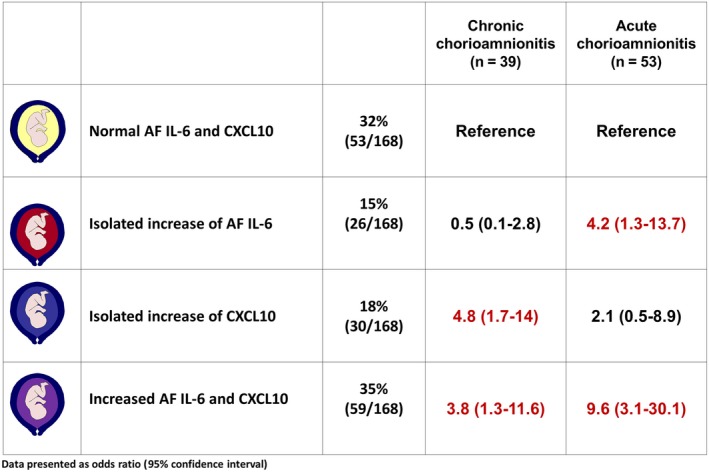

The magnitudes of association between the study groups according to amniotic fluid CXCL10 and IL‐6 concentrations and the presence or absence of acute or chronic chorioamnionitis are described in Figure 3. Patients with an isolated elevation in CXCL10 concentration were significantly more likely to have chronic, but not acute, chorioamnionitis (OR: 4.8, 95% CI: 1.7‐14; and OR: 2.1, 95% CI: 0.5‐8.9, respectively) than those with normal amniotic fluid CXCL10 and IL‐6 concentrations, after adjusting for gestational age at amniocentesis. In contrast, patients with an isolated elevation in amniotic fluid IL‐6 concentration were significantly more likely to have acute (≥stage 2), but not chronic, chorioamnionitis (OR: 4.2, 95% CI: 1.3‐13.7; and OR: 0.5, 95% CI: 0.1‐2.8, respectively) than those with normal amniotic fluid CXCL10 and IL‐6 concentrations. An elevation in amniotic fluid concentrations of both CXCL10 and IL‐6 was associated with acute (≥stage 2) and chronic chorioamnionitis (OR: 9.6, 95% CI: 3.1‐30; and OR: 3.8, 95% CI: 1.3‐11.6, respectively). None of the patients whose placentas had both acute (≥stage 2) and chronic chorioamnionitis (n=6) had normal amniotic fluid CXCL10 and IL‐6 concentrations.

Figure 3.

Magnitudes of association between the study groups according to amniotic fluid IL‐6 and CXCL10 concentrations and the presence or absence of acute (≥stage 2) or chronic chorioamnionitis. Results were obtained by fitting a multinomial logistic regression model and adjusting for gestational age at amniocentesis. AF, amniotic fluid; CXCL, C‐X‐C motif chemokine; IL, interleukin. Normal AF IL‐6 and CXCL10 concentrations: IL‐6 <2.6 ng/mL and CXCL10 <2.2 ng/mL; isolated increase in AF IL‐6 concentration: IL‐6 ≥2.6 ng/mL; isolated increase in AF CXCL10 concentration: CXCL10 ≥2.2 ng/mL; increase in both AF IL‐6 and CXCL10 concentrations: IL‐6 ≥2.6 ng/mL and CXCL10 ≥2.2 ng/mL. Acute chorioamnionitis: the presence of acute chorioamnionitis ≥stage 2 in the absence of chronic chorioamnionitis; chronic chorioamnionitis: the presence of chronic chorioamnionitis in the absence of acute chorioamnionitis ≥stage 2. None of the patients grouped by their normal AF IL‐6 and CXCL10 concentrations had both acute and chronic placental inflammatory lesions; therefore, the computation of the odds ratios relative to the common reference cannot be performed. Red values indicate statistically significant associations between the study group on the left and the outcome named in the column header

The magnitudes of association observed between the study groups are shown in Figure 4 in accord with the concentrations of both amniotic fluid CXCL10 and IL‐6 as well as the placental lesions associated with maternal anti‐fetal rejection. Patients with an elevation in amniotic fluid CXCL10 concentration were significantly more likely to have placental lesions associated with maternal anti‐fetal rejection, but not acute chorioamnionitis (≥stage 2), than those with normal amniotic fluid CXCL10 and IL‐6 concentrations, adjusting for gestational age at amniocentesis (OR: 3.7, 95% CI: 1.3‐10.4; and OR: 1.6, 95% CI: 0.3‐8.3, respectively).

Figure 4.

Magnitudes of association between the study groups on the left and the outcomes listed in the column heading at the top. Results were obtained by fitting a multinomial logistic regression model and adjusting for gestational age at amniocentesis. AF, amniotic fluid; CXCL, C‐X‐C motif chemokine; IL, interleukin. Normal AF IL‐6 and CXCL10 concentrations: IL‐6 <2.6 ng/mL and CXCL10 <2.2 ng/mL; isolated increase in AF IL‐6 concentration: IL‐6 ≥2.6 ng/mL; isolated increase in AF CXCL10 concentration: CXCL10 ≥2.2 ng/mL; increase in both AF IL‐6 and CXCL10 concentrations: IL‐6 ≥2.6 ng/mL and CXCL10 ≥2.2 ng/mL. Acute chorioamnionitis: the presence of acute chorioamnionitis ≥stage 2 in the absence of chronic chorioamnionitis; chronic chorioamnionitis: the presence of chronic chorioamnionitis in the absence of acute chorioamnionitis ≥stage 2; placental lesions associated with maternal anti‐fetal rejection: chronic chorioamnionitis, villitis of unknown etiology (VUE), and chronic deciduitis with plasma cells. None of the patients grouped by their normal AF IL‐6 and CXCL10 concentrations had both acute and chronic placental inflammatory lesions; therefore, the computation of the odds ratios relative to the common reference cannot be performed. Red values indicate statistically significant associations between the study group on the left and the outcome named in the column header

The combination of both acute chorioamnionitis (≥stage 2) and placental lesions associated with maternal anti‐fetal rejection was not observed in patients without an elevation in amniotic fluid IL‐6 and CXCL10 concentrations (Figure 4).

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal findings of the study

(i) An isolated elevation in amniotic fluid CXCL10 concentration is associated with chronic, but not acute (≥stage 2), histologic chorioamnionitis; (ii) in contrast, an isolated elevation in amniotic fluid IL‐6 concentration was associated with acute (≥stage 2), but not chronic, histologic chorioamnionitis; (iii) similar findings were observed in relation to placental lesions associated with maternal anti‐fetal rejection (chronic chorioamnionitis, VUE, and/or chronic deciduitis with plasma cells). Specifically, an isolated elevation in amniotic fluid CXCL10 concentration is associated with the subsequent delivery of placentas with lesions consistent with maternal anti‐fetal rejection but not acute histologic chorioamnionitis (≥stage 2); (iv) elevation in both CXCL10 and IL‐6 is associated with acute and chronic inflammatory lesions of the placenta, as well as the combination of lesions suggesting that a complex pathologic state representing a mixture of maternal anti‐fetal rejection and infection may lead to early preterm delivery in these cases; and (v) all patients with elevated AF concentrations of both CXCL10 and IL‐6 delivered prematurely.

4.2. Two types of intra‐amniotic inflammation in preterm labor

4.2.1. Microbial‐associated and sterile intra‐amniotic inflammation

Preterm parturition is a syndrome caused by multiple etiologies.2, 4, 6, 7, 8, 12 Intra‐amniotic infection is present in one of every three preterm deliveries and is even more frequent in cases of spontaneous preterm labor with intact membranes.221, 222, 223, 224, 225, 226 Microorganisms are detected in the amniotic cavity in 25‐40% of patients with preterm labor and intact membranes who deliver preterm133, 221, 222, 223, 224, 225, 226, 227, 228, 229, 230, 231, 232, 233, 234 and in 50‐75% of those with preterm PROM at the time of labor onset.235 The earlier the gestational age at presentation, the greater the risk of MIAC or intra‐amniotic infection.6, 12, 225, 226, 233, 236, 237, 238

The current study found that 79.8% (134/168) of patients with preterm labor/PROM have no evidence of MIAC, suggesting the important role of sterile inflammation of the amniotic cavity. Using a combination of cultivation and molecular techniques, we have previously reported that only a fraction of all patients with intra‐amniotic inflammation (defined as an increase in amniotic fluid IL‐6 concentration) have microorganisms present in the amniotic cavity; therefore, sterile intra‐amniotic fluid inflammation has emerged as an important mechanism of disease in preterm labor.124, 205, 206, 207, 209 Danger signals released during the course of cellular stress, necrosis, pyroptosis, and senescence as well as other non‐microbial injury can trigger an inflammatory response in the absence of microorganisms.214, 239, 240, 241, 242, 243, 244, 245, 246, 247, 248, 249, 250, 251, 252, 253, 254, 255, 256 Danger signals may also participate in the sterile inflammatory response associated with spontaneous labor at term and are probably mediated by activation of the inflammasomes.244, 257, 258, 259, 260, 261 Recent evidence suggests that the intra‐amniotic administration of alarmins such as HMGB1 can induce preterm parturition in mice262 and that this cytokine can induce a robust immune response characterized by secretion of IL‐6 and IL‐1β from human fetal membranes,263 suggesting a role for the inflammasomes in the mechanisms leading to premature labor in cases of sterile inflammation.124, 214, 250 Thus, this mechanism may be involved in patients with sterile intra‐amniotic inflammation characterized by elevated amniotic fluid IL‐6 concentrations and acute histologic chorioamnionitis. Moreover, a fraction of patients included in this study had elevated concentrations of amniotic fluid IL‐6 and CXCL10; these patients delivered preterm and had an odds ratio of 10.9 for acute histologic chorioamnionitis and 4.3 for placental lesions consistent with maternal anti‐fetal rejection. The role of the interaction between the acute inflammatory processes that activate the inflammasome and involve fetal rejection is yet to be discovered.

When bacteria and other microorganisms are present in the amniotic cavity and elicit an inflammatory response, a wide range of chemokines and cytokines, such as IL‐8,111, 112, 113, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140 IL‐6,106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 123, 124, 125, 126, 128, 129, 130 monocyte chemotactic protein‐1,164, 165 CXCL10 (IP‐10),128, 169 macrophage inflammatory protein‐1α,264, 265 growth‐regulated oncogene (GRO)‐α,135 and other inflammation‐related proteins118, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163, 166, 167, 168, 170, 171, 172, 173, 174, 175, 176, 179, 266 are produced, and this can result in the chemotaxis of inflammatory cells to the chorioamniotic membranes. Among these inflammation‐related proteins, IL‐6 has become the key cytokine for the diagnosis of intra‐amniotic inflammation because its increase in concentration has been associated with a shorter interval to delivery and an increased rate of neonatal morbidity and mortality.109, 124, 267, 268 Recently, an in‐depth analysis of the chemokine network in preterm labor with and without inflammation, sterile inflammation, and intra‐amniotic infection has been reported.269 Network analysis provides a greater level of insight into the biology of the process, given that the protein inflammatory process operates through a network rather than single molecules.269 Collectively, amniotic fluid IL‐6 is a pragmatic marker of either microbial‐associated or sterile intra‐amniotic inflammation. With the development of high‐fidelity assays that allow multiplex analysis of biological fluids, we anticipate that it will be possible to characterize with greater detail the biology of the immune response, timetable, response to therapy, and other important clinical characteristics.

4.2.2. A novel form of intra‐amniotic inflammation characterized by CXCL10

We previously identified a form of intra‐amniotic inflammation characterized by an increase in CXCL10 concentration15, 169 associated with chronic chorioamnionitis, the most common placental lesion in late spontaneous preterm delivery.22 This form of intra‐amniotic inflammation is considered a manifestation of maternal anti‐fetal rejection,15, 22, 26, 169 as an infectious cause has not been identified by the use of cultivation and molecular methods.

Compelling evidence suggests that CXCL10 plays an important role in the pathogenesis of graft failure and rejection in other organ systems.97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102 Overexpression of this T‐cell chemokine has been observed in the serum/plasma,270, 271 urine,272, 273 and tissue biopsies99, 274, 275, 276 from patients who experienced rejection in cases of kidney,270, 277, 278, 279, 280, 281, 282 heart,283, 284, 285 lung,271, 274 and vascular transplantation.286, 287, 288 Moreover, there is a significant correlation between serum/plasma CXCL10 concentrations and the timing and severity of allograft rejection.100, 270, 271, 279, 285

In chronic chorioamnionitis, which can be considered a form of allograft rejection, there is an upregulation of CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 mRNA expression in the chorioamniotic membranes.15 Upregulation of CXC chemokines for CXCR3+ (receptor for T‐cell chemokines) cells in the chorioamniotic membranes is associated with a higher median amniotic fluid T‐cell chemokine (CXCL10) concentration, and also chronic chorioamnionitis, presumably by stimulating amniotrophic maternal T‐cell migration to the chorioamniotic membranes.15 This placental lesion represents a manifestation of maternal anti‐fetal rejection as demonstrated by: (i) higher maternal anti‐fetal human leukocyte antigen (HLA) sensitization18 in patients with chronic chorioamnionitis than in those without this lesion; (ii) complement deposition (C4d), a surrogate marker of antibody‐mediated rejection, in the umbilical vein;16, 23, 24 and (iii) the presence of a novel form of fetal systemic inflammation (FIRS type 2) in the setting of chronic chorioamnionitis. The transcriptome of the umbilical cord blood in FIRS type 2 is different from that of FIRS type 1, indicating that this is a different condition.21 Moreover, a proteomic analysis of the amniotic fluid from patients with chronic chorioamnionitis demonstrated that these patients have lower amniotic fluid concentrations of glycodelin‐A,289 a protein implicated in the maintenance of maternal tolerance against a semiallogeneic fetus.290

Interestingly, approximately 40% of placentas with chronic chorioamnionitis from patients with preterm labor or preterm PROM have concomitant VUE and chronic deciduitis with plasma cells.15 We demonstrated the systemic derangement of the chemokine concentrations that occurred in the maternal and fetal circulation systems of patients with VUE, which was distinct from that observed in the setting of acute chorioamnionitis.14 The mRNA expression of a subset of chemokines and their receptors (CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11, CXCL13, and CXCR3) was also higher in VUE placentas than in normal placentas.14 Moreover, the median concentrations of CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 in maternal and fetal plasma were higher in patients with VUE than in those without this lesion.14 Therefore, we also consider VUE as a manifestation of maternal anti‐fetal rejection unless a microorganism can be identified.

In summary, intra‐amniotic inflammation associated with maternal anti‐fetal rejection differs from microbial‐associated intra‐amniotic inflammation; it is characterized by an elevation in T‐cell chemokine concentration in the amniotic fluid and chorioamniotic membranes as well as the presence of chronic inflammatory lesions of the placenta.

4.3. CXCL10: a biomarker for chronic placental inflammatory lesions

The results of the study herein support the view that CXCL10 is a marker for chronic inflammatory lesions of the placenta. Our findings are consistent with those of Gervasi et al.,169 who reported that mid‐trimester amniotic fluid CXCL10 concentrations >502 pg/mL were associated with late (>32 weeks) spontaneous preterm delivery (OR: 3.9; 95% CI: 1.6‐9.9), whereas elevated amniotic fluid IL‐6 concentrations (>1740 pg/mL) were associated with a higher risk of spontaneous preterm delivery prior to 32 weeks of gestation (OR: 9.5; 95% CI: 2.9‐31.1). Our study differs in that we examined the relationship between the isolated elevation in either amniotic fluid CXCL10 or amniotic fluid IL‐6 concentration and the association with both acute and chronic histologic chorioamnionitis.

4.4. What is the significance of an elevation in the concentrations of amniotic fluid IL‐6 and CXCL10?

Thirty‐five percent (59/168) of patients in this study had elevated amniotic fluid concentrations of both IL‐6 and CXCL10. All of them had spontaneous preterm delivery <37 weeks and <34 weeks of gestation, respectively, suggesting a severe inflammatory process associated with preterm delivery. Moreover, patients with an elevation in both amniotic fluid IL‐6 and CXCL10 concentrations had a significantly higher frequency of spontaneous preterm delivery within 48 hours of amniocentesis than those with an isolated elevation in amniotic fluid CXCL10 concentration (Table 2). Indeed, a systemic fetal inflammatory response (defined as the presence of funisitis or chorionic vasculitis)197 was detected in 54.2% (32/59) of patients with an elevation in both amniotic fluid CXCL10 and IL‐6 concentrations, but in only 34.6% (9/26) and 20% (6/30) of patients with an isolated elevation in amniotic fluid IL‐6 or CXCL10 concentration, respectively (Table 2). One interpretation proposes that patients with a combination of increased amniotic fluid IL‐6 and CXCL10 concentrations had a more severe form of intra‐amniotic inflammation than those with an isolated elevation in either CXCL10 or IL‐6 concentration, in whom the clinical course leading to preterm delivery may be more indolent in nature. This could explain the trend toward a more frequent involvement of the fetus in patients with an elevation in both amniotic fluid CXCL10 and IL‐6 concentrations.

CXCL10 has been implicated in the pathophysiology of sepsis by recruiting neutrophils, macrophages, and T cells.291, 292 Previous studies demonstrated that there is an upregulation of CXCL10 leading to subsequent activation of its receptor (CXCR3) during infection and inflammation.293, 294 In an experimental model of septic shock induced by cecal ligation and puncture, it has been shown that plasma and peritoneal fluid CXCL10 concentrations increase.295 Additionally, CXCL10 knockout mice and wild‐type mice treated with anti‐CXCL10 IgG antibody had less cytokine production and increased survival.296 Similar observations were found for the role of CXCR3 during sepsis; it regulates NK‐ and T‐cell trafficking. Moreover, in a septic shock model for mice, the blockade of CXCR3 decreases systemic inflammation and improves survival.296, 297 CXCL10 and CXCR3 also play a role in human sepsis, and plasma CXCL10 is a predictor of septic shock.298, 299, 300 Collectively, these data suggest that CXCL10 is an inflammatory mediator involved in the response to microorganisms and bacterial products; therefore, some cases of advanced infections could have elevated concentrations of both IL‐6 and CXCL10. An elevated amniotic fluid concentration of CXCL10 would be more meaningful to identify the patient at risk of chronic inflammatory lesions of the placenta if the amniotic fluid concentration of IL‐6 is not elevated.

4.5. Strengths and limitations

The major strengths of this study are as follows: pathologists were blinded to the obstetrical diagnoses and outcomes; standardized protocols were utilized for placental examinations; and the consideration of isolated rather than any increase in the concentration of either amniotic fluid CXCL10 or amniotic fluid IL‐6. Limitations were related to the small sample size. Further studies are required to characterize the temporal relationship between exposure to microbial products or other insults and the amniotic fluid changes in cytokines and chemokines. Moreover, large studies are necessary to determine the diagnostic indices of CXCL10 elevation to identify the patient at risk of chronic placental inflammation.

5. Conclusion

An isolated elevation in amniotic fluid CXCL10 concentration (without a concomitant elevation in IL‐6 concentration) is associated with the delivery of a placenta with histologic chronic chorioamnionitis or lesions consistent with maternal anti‐fetal rejection, whereas an isolated increase in amniotic fluid IL‐6 concentration is associated with the delivery of a placenta with acute histologic chorioamnionitis.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by the Perinatology Research Branch, Program for Perinatal Research and Obstetrics, Division of Intramural Research, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services (NICHD/NIH/DHHS); and, in part, with Federal funds from NICHD/NIH/DHHS under Contract No. HHSN275201300006C.

Romero R, Chaemsaithong P, Chaiyasit N, et al. CXCL10 and IL‐6: Markers of two different forms of intra‐amniotic inflammation in preterm labor. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2017;78:e12685 https://doi.org/10.1111/aji.12685

Presented at the 12th World Congress of Perinatal Medicine, Madrid, Spain, November 3‐6, 2015.

Contributor Information

Roberto Romero, Email: prbchiefstaff@med.wayne.edu.

Steven J. Korzeniewski, Email: skorzeni@med.wayne.edu

References

- 1. Wilkins I, Creasy RK. Preterm labor. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1990;33:502‐514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Romero R, Mazor M, Munoz H, Gomez R, Galasso M, Sherer DM. The preterm labor syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;734:414‐429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mazor M, Chaim W, Romero R. [Preterm labor syndrome]. Harefuah. 1995;128:111‐116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Romero R, Gomez R, Mazor M, Ghezzi F, Yoon BH. The preterm labor syndrome In: Elder MG, Romero R, Lamont RF, eds. Preterm Labor. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1997:29‐49. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dudley DJ. Pre‐term labor: an intra‐uterine inflammatory response syndrome? J Reprod Immunol. 1997;36:93‐109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Romero R, Espinoza J, Kusanovic JP, et al. The preterm parturition syndrome. BJOG. 2006;113(Suppl 3):17‐42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Villar J, Papageorghiou AT, Knight HE, et al. The preterm birth syndrome: a prototype phenotypic classification. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:119‐123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kramer MS, Papageorghiou A, Culhane J, et al. Challenges in defining and classifying the preterm birth syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:108‐112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Goldenberg RL, Gravett MG, Iams J, et al. The preterm birth syndrome: issues to consider in creating a classification system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:113‐118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Blencowe H, Cousens S, Chou D, et al. Born too soon: the global epidemiology of 15 million preterm births. Reprod Health. 2013;10(Suppl 1):S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Guimaraes Filho HA, Araujo Junior E, Pires CR, Nardozza LM, Moron AF. Short cervix syndrome: current knowledge from etiology to the control. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013;287:621‐628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Romero R, Dey SK, Fisher SJ. Preterm labor: one syndrome, many causes. Science. 2014;345:760‐765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fuzzi B, Rizzo R, Criscuoli L, et al. HLA‐G expression in early embryos is a fundamental prerequisite for the obtainment of pregnancy. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:311‐315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim MJ, Romero R, Kim CJ, et al. Villitis of unknown etiology is associated with a distinct pattern of chemokine up‐regulation in the feto‐maternal and placental compartments: implications for conjoint maternal allograft rejection and maternal anti‐fetal graft‐versus‐host disease. J Immunol. 2009;182:3919‐3927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim CJ, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, et al. The frequency, clinical significance, and pathological features of chronic chorioamnionitis: a lesion associated with spontaneous preterm birth. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:1000‐1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee J, Romero R, Xu Y, et al. A signature of maternal anti‐fetal rejection in spontaneous preterm birth: chronic chorioamnionitis, anti‐human leukocyte antigen antibodies, and C4d. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee J, Romero R, Dong Z, et al. Unexplained fetal death has a biological signature of maternal anti‐fetal rejection: chronic chorioamnionitis and alloimmune anti‐human leucocyte antigen antibodies. Histopathology. 2011;59:928‐938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee J, Romero R, Xu Y, et al. Maternal HLA panel‐reactive antibodies in early gestation positively correlate with chronic chorioamnionitis: evidence in support of the chronic nature of maternal anti‐fetal rejection. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;66:510‐526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Romero R, Whitten A, Korzeniewski SJ, et al. Maternal floor infarction/massive perivillous fibrin deposition: a manifestation of maternal antifetal rejection? Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013;70:285‐298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee J, Romero R, Xu Y, et al. Detection of anti‐HLA antibodies in maternal blood in the second trimester to identify patients at risk of antibody‐mediated maternal anti‐fetal rejection and spontaneous preterm delivery. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013;70:162‐175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee J, Romero R, Chaiworapongsa T, et al. Characterization of the fetal blood transcriptome and proteome in maternal anti‐fetal rejection: evidence of a distinct and novel type of human fetal systemic inflammatory response. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013;70:265‐284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee J, Kim JS, Park JW, et al. Chronic chorioamnionitis is the most common placental lesion in late preterm birth. Placenta. 2013;34:681‐689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee KA, Kim YW, Shim JY, et al. Distinct patterns of C4d immunoreactivity in placentas with villitis of unknown etiology, cytomegaloviral placentitis, and infarct. Placenta. 2013;34:432‐435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rudzinski E, Gilroy M, Newbill C, Morgan T. Positive C4d immunostaining of placental villous syncytiotrophoblasts supports host‐versus‐graft rejection in villitis of unknown etiology. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2013;16:7‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lannaman K, Romero R, Chaemsaithong P, et al. Abstract No. 497 Fetal death: an extreme form of maternal anti‐fetal rejection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:S251. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim CJ, Romero R, Chaemsaithong P, Kim J. Chronic inflammation of the placenta: definition, classification, pathogenesis, and clinical significance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:S53‐S69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Clark GF. The role of glycans in immune evasion: the human fetoembryonic defence system hypothesis revisited. Mol Hum Reprod. 2014;20:185‐199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jiang TT, Chaturvedi V, Ertelt JM, et al. Regulatory T cells: new keys for further unlocking the enigma of fetal tolerance and pregnancy complications. J Immunol. 2014;192:4949‐4956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee YC, Lin SJ. Natural killer cell in the developing life. J Perinat Med. 2015;43:11‐17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schefold JC, Porz L, Uebe B, et al. Diminished HLA‐DR expression on monocyte and dendritic cell subsets indicating impairment of cellular immunity in pre‐term neonates: a prospective observational analysis. J Perinat Med. 2015;43:609‐618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Erlebacher A. Why isn't the fetus rejected? Curr Opin Immunol. 2001;13:590‐593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Koch CA, Platt JL. Natural mechanisms for evading graft rejection: the fetus as an allograft. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2003;25:95‐117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Trowsdale J, Betz AG. Mother's little helpers: mechanisms of maternal‐fetal tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:241‐246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Leslie M. Immunology. Fetal immune system hushes attacks on maternal cells. Science. 2008;322:1450‐1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mold JE, Michaelsson J, Burt TD, et al. Maternal alloantigens promote the development of tolerogenic fetal regulatory T cells in utero. Science. 2008;322:1562‐1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Burlingham WJ. A lesson in tolerance–maternal instruction to fetal cells. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1355‐1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chaouat G, Petitbarat M, Dubanchet S, Rahmati M, Ledee N. Tolerance to the foetal allograft? Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;63:624‐636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bluestone JA. Mechanisms of tolerance. Immunol Rev. 2011;241:5‐19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rowe JH, Ertelt JM, Xin L, Way SS. Pregnancy imprints regulatory memory that sustains anergy to fetal antigen. Nature. 2012;490:102‐106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Betz AG. Immunology: tolerating pregnancy. Nature. 2012;490:47‐48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Williams Z. Inducing tolerance to pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1159‐1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Erlebacher A. Mechanisms of T cell tolerance towards the allogeneic fetus. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:23‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Le Moine A, Goldman M, Abramowicz D. Multiple pathways to allograft rejection. Transplantation. 2002;73:1373‐1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Colvin RB, Smith RN. Antibody‐mediated organ‐allograft rejection. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:807‐817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Alegre ML, Florquin S, Goldman M. Cellular mechanisms underlying acute graft rejection: time for reassessment. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:563‐568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kim IK, Bedi DS, Denecke C, Ge X, Tullius SG. Impact of innate and adaptive immunity on rejection and tolerance. Transplantation. 2008;86:889‐894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wood KJ, Goto R. Mechanisms of rejection: current perspectives. Transplantation. 2012;93:1‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ali JM, Bolton EM, Bradley JA, Pettigrew GJ. Allorecognition pathways in transplant rejection and tolerance. Transplantation. 2013;96:681‐688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Krensky AM. Immunologic tolerance. Pediatr Nephrol. 2001;16:675‐679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sacks G, Sargent I, Redman C. An innate view of human pregnancy. Immunol Today. 1999;20:114‐118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Szekeres‐Bartho J. Immunological relationship between the mother and the fetus. Int Rev Immunol. 2002;21:471‐495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Aluvihare VR, Kallikourdis M, Betz AG. Regulatory T cells mediate maternal tolerance to the fetus. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:266‐271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Erlebacher A. Immunology of the maternal‐fetal interface. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:387‐411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nancy P, Tagliani E, Tay CS, Asp P, Levy DE, Erlebacher A. Chemokine gene silencing in decidual stromal cells limits T cell access to the maternal‐fetal interface. Science. 2012;336:1317‐1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Somerset DA, Zheng Y, Kilby MD, Sansom DM, Drayson MT. Normal human pregnancy is associated with an elevation in the immune suppressive CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T‐cell subset. Immunology. 2004;112:38‐43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sasaki Y, Sakai M, Miyazaki S, Higuma S, Shiozaki A, Saito S. Decidual and peripheral blood CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in early pregnancy subjects and spontaneous abortion cases. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10:347‐353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zenclussen AC, Gerlof K, Zenclussen ML, et al. Abnormal T‐cell reactivity against paternal antigens in spontaneous abortion: adoptive transfer of pregnancy‐induced CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells prevents fetal rejection in a murine abortion model. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:811‐822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lee JH, Ulrich B, Cho J, Park J, Kim CH. Progesterone promotes differentiation of human cord blood fetal T cells into T regulatory cells but suppresses their differentiation into Th17 cells. J Immunol. 2011;187:1778‐1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ramhorst R, Fraccaroli L, Aldo P, et al. Modulation and recruitment of inducible regulatory T cells by first trimester trophoblast cells. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2012;67:17‐27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Quinn KH, Parast MM. Decidual regulatory T cells in placental pathology and pregnancy complications. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013;69:533‐538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wilczynski JR, Kalinka J, Radwan M. The role of T‐regulatory cells in pregnancy and cancer. Front Biosci. 2008;13:2275‐2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Schumacher A, Zenclussen AC. Regulatory T cells: regulators of life. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014;72:158‐170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Collier A, Cook H, Loewendorf A, Yesayan M, Kahn D. Abstract No. 438 Disruption of maternal tolerance during pregnancy leads to Treg repopulation of the antigenic UPI. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:S226‐S227. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Saifi B, Aflatoonian R, Tajik N, et al. T regulatory markers expression in unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29:1175‐1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kovats S, Main EK, Librach C, Stubblebine M, Fisher SJ, DeMars R. A class I antigen, HLA‐G, expressed in human trophoblasts. Science. 1990;248:220‐223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. McMaster MT, Librach CL, Zhou Y, et al. Human placental HLA‐G expression is restricted to differentiated cytotrophoblasts. J Immunol. 1995;154:3771‐3778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ishitani A, Sageshima N, Lee N, et al. Protein expression and peptide binding suggest unique and interacting functional roles for HLA‐E, F, and G in maternal‐placental immune recognition. J Immunol. 2003;171:1376‐1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hunt JS, Petroff MG, McIntire RH, Ober C. HLA‐G and immune tolerance in pregnancy. FASEB J. 2005;19:681‐693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Larsen MH, Hviid TV. Human leukocyte antigen‐G polymorphism in relation to expression, function, and disease. Hum Immunol. 2009;70:1026‐1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ritsick DR, Bommer C, Braverman J. Abstract: The role of fetomaternal MHC class II histoincompatibility in regulating tolerance of the semi‐allogenic fetus. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014;71:37‐38. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Munn DH, Zhou M, Attwood JT, et al. Prevention of allogeneic fetal rejection by tryptophan catabolism. Science. 1998;281:1191‐1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kudo Y, Boyd CA. Human placental indoleamine 2,3‐dioxygenase: cellular localization and characterization of an enzyme preventing fetal rejection. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2000;1500:119‐124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Mellor AL, Sivakumar J, Chandler P, et al. Prevention of T cell‐driven complement activation and inflammation by tryptophan catabolism during pregnancy. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:64‐68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Mellor AL, Chandler P, Lee GK, et al. Indoleamine 2,3‐dioxygenase, immunosuppression and pregnancy. J Reprod Immunol. 2002;57:143‐150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kudo Y. The role of placental indoleamine 2,3‐dioxygenase in human pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2013;56:209‐216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Hunt JS, Vassmer D, Ferguson TA, Miller L. Fas ligand is positioned in mouse uterus and placenta to prevent trafficking of activated leukocytes between the mother and the conceptus. J Immunol. 1997;158:4122‐4128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Uckan D, Steele A, Cherry, et al. Trophoblasts express Fas ligand: a proposed mechanism for immune privilege in placenta and maternal invasion. Mol Hum Reprod. 1997;3:655‐662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Holmes CH, Simpson KL, Wainwright SD, et al. Preferential expression of the complement regulatory protein decay accelerating factor at the fetomaternal interface during human pregnancy. J Immunol. 1990;144:3099‐3105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Hsi BL, Hunt JS, Atkinson JP. Differential expression of complement regulatory proteins on subpopulations of human trophoblast cells. J Reprod Immunol. 1991;19:209‐223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Altemani AM, Norato D, Baumel C. Immunological studies in placentas with villitis of unknown etiology: complement components and immunoglobulins in chorionic villi. J Perinat Med. 1992;20:129‐134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Holmes CH, Simpson KL, Okada H, et al. Complement regulatory proteins at the feto‐maternal interface during human placental development: distribution of CD59 by comparison with membrane cofactor protein (CD46) and decay accelerating factor (CD55). Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:1579‐1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Tedesco F, Narchi G, Radillo O, Meri S, Ferrone S, Betterle C. Susceptibility of human trophoblast to killing by human complement and the role of the complement regulatory proteins. J Immunol. 1993;151:1562‐1570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Xu C, Mao D, Holers VM, Palanca B, Cheng AM, Molina H. A critical role for murine complement regulator crry in fetomaternal tolerance. Science. 2000;287:498‐501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Richani K, Romero R, Soto E, et al. Unexplained intrauterine fetal death is accompanied by activation of complement. J Perinat Med. 2005;33:296‐305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Soto E, Romero R, Richani K, et al. Anaphylatoxins in preterm and term labor. J Perinat Med. 2005;33:306‐313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Girardi G, Bulla R, Salmon JE, Tedesco F. The complement system in the pathophysiology of pregnancy. Mol Immunol. 2006;43:68‐77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Girardi G. Complement inhibition keeps mothers calm and avoids fetal rejection. Immunol Invest. 2008;37:645‐659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Mittal P, Romero R, Tarca AL, et al. Characterization of the myometrial transcriptome and biological pathways of spontaneous human labor at term. J Perinat Med. 2010;38:617‐643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Chaiworapongsa T, Romero R, Whitten A, et al. Differences and similarities in the transcriptional profile of peripheral whole blood in early and late‐onset preeclampsia: insights into the molecular basis of the phenotype of preeclampsiaa . J Perinat Med. 2013;41:485‐504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Madan I, Than NG, Romero R, et al. The peripheral whole‐blood transcriptome of acute pyelonephritis in human pregnancya . J Perinat Med. 2014;42:31‐53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Guleria I, Khosroshahi A, Ansari MJ, et al. A critical role for the programmed death ligand 1 in fetomaternal tolerance. J Exp Med. 2005;202:231‐237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Habicht A, Dada S, Jurewicz M, et al. A link between PDL1 and T regulatory cells in fetomaternal tolerance. J Immunol. 2007;179:5211‐5219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. D'Addio F, Riella LV, Mfarrej BG, et al. The link between the PDL1 costimulatory pathway and Th17 in fetomaternal tolerance. J Immunol. 2011;187:4530‐4541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Xin L, Ertelt JM, Rowe JH, et al. Cutting edge: committed Th1 CD4+ T cell differentiation blocks pregnancy‐induced Foxp3 expression with antigen‐specific fetal loss. J Immunol. 2014;192:2970‐2974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Kinder JM, Jiang TT, Ertelt JM, et al. Cross‐generational reproductive fitness enforced by microchimeric maternal cells. Cell. 2015;162:505‐515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. PrabhuDas M, Bonney E, Caron K, et al. Immune mechanisms at the maternal‐fetal interface: perspectives and challenges. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:328‐334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Romagnani P, Lasagni L, Annunziato F, Serio M, Romagnani S. CXC chemokines: the regulatory link between inflammation and angiogenesis. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:201‐209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Lazzeri E, Romagnani P. CXCR3‐binding chemokines: novel multifunctional therapeutic targets. Curr Drug Targets Immune Endocr Metabol Disord. 2005;5:109‐118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Tan J, Zhou G. Chemokine receptors and transplantation. Cell Mol Immunol. 2005;2:343‐349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Romagnani P. From basic science to clinical practice: use of cytokines and chemokines as therapeutic targets in renal diseases. J Nephrol. 2005;18:229‐233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Romagnani P, Crescioli C. CXCL10: a candidate biomarker in transplantation. Clin Chim Acta. 2012;413:1364‐1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Zhang Q, Liu YF, Su ZX, Shi LP, Chen YH. Serum fractalkine and interferon‐gamma inducible protein‐10 concentrations are early detection markers for acute renal allograft rejection. Transplant Proc. 2014;46:1420‐1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Kim YM, Chaemsaithong P, Romero R, et al. Placental lesions associated with acute atherosis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28:1554‐1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Gomez‐Lopez N, Hernandez‐Santiago S, Lobb AP, Olson DM, Vadillo‐Ortega F. Normal and premature rupture of fetal membranes at term delivery differ in regional chemotactic activity and related chemokine/cytokine production. Reprod Sci. 2013;20:276‐284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Gong X, Chen Z, Liu Y, Lu Q, Jin Z. Gene expression profiling of the paracrine effects of uterine natural killer cells on human endometrial epithelial cells. Int J Endocrinol. 2014;2014:393707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Romero R, Avila C, Santhanam U, Sehgal PB. Amniotic fluid interleukin 6 in preterm labor. Association with infection. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:1392‐1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Romero R, Sepulveda W, Kenney JS, Archer LE, Allison AC, Sehgal PB. Interleukin 6 determination in the detection of microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity. Ciba Found Symp. 1992;167:205‐220; discussion 220–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Romero R, Yoon BH, Kenney JS, Gomez R, Allison AC, Sehgal PB. Amniotic fluid interleukin‐6 determinations are of diagnostic and prognostic value in preterm labor. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1993;30:167‐183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Yoon BH, Romero R, Kim CJ, et al. Amniotic fluid interleukin‐6: a sensitive test for antenatal diagnosis of acute inflammatory lesions of preterm placenta and prediction of perinatal morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172:960‐970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Cox SM, Casey ML, MacDonald PC. Accumulation of interleukin‐1beta and interleukin‐6 in amniotic fluid: a sequela of labour at term and preterm. Hum Reprod Update. 1997;3:517‐527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Yoon BH, Romero R, Jun JK, et al. Amniotic fluid cytokines (interleukin‐6, tumor necrosis factor‐alpha, interleukin‐1 beta, and interleukin‐8) and the risk for the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:825‐830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Arntzen KJ, Kjollesdal AM, Halgunset J, Vatten L, Austgulen R. TNF, IL‐1, IL‐6, IL‐8 and soluble TNF receptors in relation to chorioamnionitis and premature labor. J Perinat Med. 1998;26:17‐26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Hsu CD, Meaddough E, Aversa K, et al. Elevated amniotic fluid levels of leukemia inhibitory factor, interleukin 6, and interleukin 8 in intra‐amniotic infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1267‐1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Yoon BH, Romero R, Moon JB, et al. Clinical significance of intra‐amniotic inflammation in patients with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1130‐1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Yoon BH, Romero R, Moon J, et al. Differences in the fetal interleukin‐6 response to microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity between term and preterm gestation. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2003;13:32‐38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Jacobsson B, Mattsby‐Baltzer I, Hagberg H. Interleukin‐6 and interleukin‐8 in cervical and amniotic fluid: relationship to microbial invasion of the chorioamniotic membranes. BJOG. 2005;112:719‐724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Holst RM, Mattsby‐Baltzer I, Wennerholm UB, Hagberg H, Jacobsson B. Interleukin‐6 and interleukin‐8 in cervical fluid in a population of Swedish women in preterm labor: relationship to microbial invasion of the amniotic fluid, intra‐amniotic inflammation, and preterm delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005;84:551‐557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Holst RM, Laurini R, Jacobsson B, et al. Expression of cytokines and chemokines in cervical and amniotic fluid: relationship to histological chorioamnionitis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;20:885‐893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Menon R, Camargo MC, Thorsen P, Lombardi SJ, Fortunato SJ. Amniotic fluid interleukin‐6 increase is an indicator of spontaneous preterm birth in white but not black Americans. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:77 e71‐77 e77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Marconi C, de Andrade Ramos BR, Peracoli JC, Donders GG, da Silva MG. Amniotic fluid interleukin‐1 beta and interleukin‐6, but not interleukin‐8 correlate with microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity in preterm labor. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;65:549‐556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Cobo T, Palacio M, Martinez‐Terron M, et al. Clinical and inflammatory markers in amniotic fluid as predictors of adverse outcomes in preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:126 e121‐126 e128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Combs CA, Gravett C, Garite T, et al. Abstract No. 73: Intramniotic inflammation may be more important than the presence of microbes as a determinant of perinatal outcome in preterm labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208:S44. [Google Scholar]

- 123. Romero R, Kadar N, Miranda J, et al. The diagnostic performance of the Mass Restricted (MR) score in the identification of microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity or intra‐amniotic inflammation is not superior to amniotic fluid interleukin‐6. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27:757‐769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Romero R, Miranda J, Chaiworapongsa T, et al. Prevalence and clinical significance of sterile intra‐amniotic inflammation in patients with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014;72:458‐474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Kacerovsky M, Musilova I, Andrys C, et al. Prelabor rupture of membranes between 34 and 37 weeks: the intraamniotic inflammatory response and neonatal outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:325 e321‐325 e310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Kacerovsky M, Musilova I, Hornychova H, et al. Bedside assessment of amniotic fluid interleukin‐6 in preterm prelabor rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:385.e1‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Combs CA, Gravett M, Garite TJ, et al. Amniotic fluid infection, inflammation, and colonization in preterm labor with intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:125 e121‐125 e115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Chaemsaithong P, Romero R, Korzeniewski SJ, et al. A point of care test for the determination of amniotic fluid interleukin‐6 and the chemokine CXCL‐10/IP‐10. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28:1510‐1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Chaemsaithong P, Romero R, Korzeniewski SJ, et al. A point of care test for interleukin‐6 in amniotic fluid in preterm prelabor rupture of membranes: a step toward the early treatment of acute intra‐amniotic inflammation/infection. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;1‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Chaemsaithong P, Romero R, Korzeniewski SJ, et al. A rapid interleukin‐6 bedside test for the identification of intra‐amniotic inflammation in preterm labor with intact membranes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;1‐11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Romero R, Ceska M, Avila C, Mazor M, Behnke E, Lindley I. Neutrophil attractant/activating peptide‐1/interleukin‐8 in term and preterm parturition. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:813‐820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Cherouny PH, Pankuch GA, Romero R, et al. Neutrophil attractant/activating peptide‐1/interleukin‐8: association with histologic chorioamnionitis, preterm delivery, and bioactive amniotic fluid leukoattractants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:1299‐1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Gomez R, Ghezzi F, Romero R, Munoz H, Tolosa JE, Rojas I. Premature labor and intra‐amniotic infection. Clinical aspects and role of the cytokines in diagnosis and pathophysiology. Clin Perinatol. 1995;22:281‐342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Ghezzi F, Gomez R, Romero R, et al. Elevated interleukin‐8 concentrations in amniotic fluid of mothers whose neonates subsequently develop bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1998;78:5‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Hsu CD, Meaddough E, Aversa K, Copel JA. The role of amniotic fluid L‐selectin, GRO‐alpha, and interleukin‐8 in the pathogenesis of intraamniotic infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:428‐432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Jacobsson B, Mattsby‐Baltzer I, Andersch B, et al. Microbial invasion and cytokine response in amniotic fluid in a Swedish population of women in preterm labor. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82:120‐128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Jacobsson B, Mattsby‐Baltzer I, Andersch B, et al. Microbial invasion and cytokine response in amniotic fluid in a Swedish population of women with preterm prelabor rupture of membranes. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82:423‐431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Figueroa R, Garry D, Elimian A, Patel K, Sehgal PB, Tejani N. Evaluation of amniotic fluid cytokines in preterm labor and intact membranes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005;18:241‐247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Witt A, Berger A, Gruber CJ, Petricevic L, Apfalter P, Husslein P. IL‐8 concentrations in maternal serum, amniotic fluid and cord blood in relation to different pathogens within the amniotic cavity. J Perinat Med. 2005;33:22‐26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Cobo T, Kacerovsky M, Palacio M, et al. Intra‐amniotic inflammatory response in subgroups of women with preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Romero R, Brody DT, Oyarzun E, et al. Infection and labor. III. Interleukin‐1: a signal for the onset of parturition. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:1117‐1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Mitchell MD, Edwin SS, Silver RM, Romero RJ. Potential agonist action of the interleukin‐1 receptor antagonist protein: implications for treatment of women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76:1386‐1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Romero R, Manogue KR, Mitchell MD, et al. Infection and labor. IV. Cachectin‐tumor necrosis factor in the amniotic fluid of women with intraamniotic infection and preterm labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:336‐341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Romero R, Mazor M, Sepulveda W, Avila C, Copeland D, Williams J. Tumor necrosis factor in preterm and term labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:1576‐1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Sadowsky DW, Adams KM, Gravett MG, Witkin SS, Novy MJ. Preterm labor is induced by intraamniotic infusions of interleukin‐1beta and tumor necrosis factor‐alpha but not by interleukin‐6 or interleukin‐8 in a nonhuman primate model. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1578‐1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Athayde N, Romero R, Maymon E, et al. Interleukin 16 in pregnancy, parturition, rupture of fetal membranes, and microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:135‐141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Pacora P, Romero R, Maymon E, et al. Participation of the novel cytokine interleukin 18 in the host response to intra‐amniotic infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:1138‐1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Greig PC, Herbert WN, Robinette BL, Teot LA. Amniotic fluid interleukin‐10 concentrations increase through pregnancy and are elevated in patients with preterm labor associated with intrauterine infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:1223‐1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Gotsch F, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, et al. The anti‐inflammatory limb of the immune response in preterm labor, intra‐amniotic infection/inflammation, and spontaneous parturition at term: a role for interleukin‐10. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21:529‐547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Maymon E, Romero R, Pacora P, et al. Human neutrophil collagenase (matrix metalloproteinase 8) in parturition, premature rupture of the membranes, and intrauterine infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:94‐99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Maymon E, Romero R, Chaiworapongsa T, et al. Amniotic fluid matrix metalloproteinase‐8 in preterm labor with intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1149‐1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Angus SR, Segel SY, Hsu CD, et al. Amniotic fluid matrix metalloproteinase‐8 indicates intra‐amniotic infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1232‐1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Nien JK, Yoon BH, Espinoza J, et al. A rapid MMP‐8 bedside test for the detection of intra‐amniotic inflammation identifies patients at risk for imminent preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1025‐1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Kim KW, Romero R, Park HS, et al. A rapid matrix metalloproteinase‐8 bedside test for the detection of intraamniotic inflammation in women with preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:292 e291‐292 e295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Park CW, Lee SM, Park JS, Jun JK, Romero R, Yoon BH. The antenatal identification of funisitis with a rapid MMP‐8 bedside test. J Perinat Med. 2008;36:497‐502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Park CW, Yoon BH, Kim SM, Park JS, Jun JK. The frequency and clinical significance of intra‐amniotic inflammation defined as an elevated amniotic fluid matrix metalloproteinase‐8 in patients with preterm labor and low amniotic fluid white blood cell counts. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2013;56:167‐175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Maymon E, Romero R, Pacora P, et al. Evidence for the participation of interstitial collagenase (matrix metalloproteinase 1) in preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:914‐920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158. Maymon E, Romero R, Pacora P, et al. A role for the 72 kDa gelatinase (MMP‐2) and its inhibitor (TIMP‐2) in human parturition, premature rupture of membranes and intraamniotic infection. J Perinat Med. 2001;29:308‐316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159. Park KH, Chaiworapongsa T, Kim YM, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 3 in parturition, premature rupture of the membranes, and microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity. J Perinat Med. 2003;31:12‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160. Maymon E, Romero R, Pacora P, et al. Matrilysin (matrix metalloproteinase 7) in parturition, premature rupture of membranes, and intrauterine infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:1545‐1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161. Locksmith GJ, Clark P, Duff P, Schultz GS. Amniotic fluid matrix metalloproteinase‐9 levels in women with preterm labor and suspected intra‐amniotic infection. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:1‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]