Abstract

The infusion of healthy stem cells into a patient—termed “stem-cell therapy”—has shown great promise for the treatment of genetic and non-genetic diseases, including mucopolysaccharidosis type 1, Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, numerous immunodeficiency disorders, and aplastic anemia. Stem cells for cell therapy can be collected from the patient (autologous) or collected from another “healthy” individual (allogeneic). The use of allogenic stem cells is accompanied with the potentially fatal risk that the transplanted donor T cells will reject the patient's cells—a process termed “graft-versus-host disease.” Therefore, the use of autologous stem cells is preferred, at least from the immunological perspective. However, an obvious drawback is that inherently as “self,” they contain the disease mutation. As such, autologous cells for use in cell therapies often require genetic “correction” (i.e., gene addition or editing) prior to cell infusion and therefore the requirement for some form of nucleic acid delivery, which sets the stage for the AAV controversy discussed herein. Despite being the most clinically applied gene delivery context to date, unlike other more concerning integrating and non-integrating vectors such as retroviruses and adenovirus, those based on adeno-associated virus (AAV) have not been employed in the clinic. Furthermore, published data regarding AAV vector transduction of stem cells are inconsistent in regards to vector transduction efficiency, while the pendulum swings far in the other direction with demonstrations of AAV vector–induced toxicity in undifferentiated cells. The variation present in the literature examining the transduction efficiency of AAV vectors in stem cells may be due to numerous factors, including inconsistencies in stem-cell collection, cell culture, vector preparation, and/or transduction conditions. This review summarizes the controversy surrounding AAV vector transduction of stem cells, hopefully setting the stage for future elucidation and eventual therapeutic applications.

Keywords: : AAV vectors, ITR, stem cell, stem cell therapy, gene therapy

Hirsch's Controversial Perspective

The first decade of this century demonstrated fascinating scientific advancements, including the first applications of designer endonucleases for genetic engineering in a human context. As a postdoctorate researcher in Richard (Jude) Samulski's lab, who cloned adeno-associated virus (AAV) from nature while in the Muzyczka Lab, I remember glancing at the cover of a nearby Science magazine, which introduced work from Matt Porteus regarding zinc-finger nucleases and the ability to modify precisely the human chromosome near therapeutic efficiencies. Science fiction was becoming reality, and like any overly ambitious postdoc in a gene delivery lab, I had set out on the quest to engineer human beings genetically by combining AAV vectors and gene editing in human embryonic stem cells (hESCs). At that time, reports of AAV transduction of hESCs were limited, in part due to governmental policies restricting their use. Additionally, hESCs are hard to maintain as a homogenous population and will differentiate if not treated with loving care. As AAV capsid directed evolution was the rage at that time, I set out to “evolve” the capsid for hESC transduction. Remarkably, an AAV2/3 chimeric, which coincidently could be termed AAV3i2 by Aravind Asokan's rational design terminology,1 was solely recovered. Yet, when tested on hESCs versus the parent serotypes, it was decreased for transduction. This made no sense, but there was an elephant in the room: the once-adherent hESCs became round, detached, and “popped” following the addition of the AAV vectors in a manner that directly correlated with the onset of the GFP+ phenotype (https://hirschlab.web.unc.edu/aav-vector-toxicity-in-human-embryonic-stem-cells/). I was unfamiliar with hESC colony behavior at the time, and therefore I consciously overlooked the overt toxicity that later rationalized the recovery of the AAV3i2: I had selected for a less efficient capsid that was slower to induce apoptosis (which was verified many ways).2 It took about 3 years of repetition and additional data, including compelling video evidence, to convince Jude that AAV maybe wasn't a friend of hESCs but rather a foe. Additionally, he would often remark that “AAV is not found in the germline,” providing incidental evidence that helped rationalize our observations and perhaps shed light on disturbing work of the last century demonstrating a link between AAV and premature abortion.3,4 Now, with my lab, I continue to elucidate this phenomenon in hESCs and in other multipotent cell types, and despite our sophomoric understanding, several leads exist that may help to understand the varied cellular responses to AAV vector transduction. Although personally biased from experience, I am more often wrong than not, herein an unbiased view of this controversy is presented based on the relevant literature in the hope of determining if AAV vectors and stem cells are really friends or foes.

AAV as a Gene Therapy Vector

AAV is currently the most researched and utilized vector for clinical gene therapy applications.5 The virus is composed of a small protein capsid (approximately 25 nm in diameter) and a 4.7 kb single-stranded DNA genome flanked by 145 nucleotide inverted terminal repeats (ITRs).6–8 Currently, at least 12 naturally occurring serotypes and >100 variants of AAV have been reported, with each serotype demonstrating semi-unique infection tropisms, although the exact mechanism(s) of wild-type AAV infection is not well understood.9,10 A few years following the cloning of wild-type AAV serotype 2 (AAV2) into a plasmid, it was discovered that the native genome could be exchanged with transgenic DNA, as long as it was situated between the ITRs, thereby allowing production of recombinant AAV or AAV vectors.11,12 Depending on the size of the transgenic genome13 and the integrity of the ITRs,14,15 AAV vector genomes can be packaged as either single-stranded DNA or as duplexed DNA (termed “self-complementary”), the latter of which demonstrates rapid and robust transgene production compared to single-stranded AAV vectors due to bypassing the need for second-strand synthesis.10,11 However, this transduction enhancement comes at a cost, as self-complementary transgenic cassettes must be less than half the size of single-stranded AAV (<2.2 kb).10,11 Traditionally, the use of AAV vectors has been focused primarily on gene addition strategies, with the caveat that as AAV vector genomes primarily exist as episomes with only inadvertent integration, applications in dividing cell populations are transient as cellular division dilutes vector episomes.16 Additional reports expanding the utility of AAV vectors demonstrate that AAV-transduced genomes are inherently preferred substrates for homologous recombination. These studies revealed that the gene-targeting frequency for AAV-based vectors was several logs higher than those obtained using plasmid substrates.17–22 AAV is particularly attractive as a gene therapy vector for multiple reasons: AAV is not associated with any disease, despite being ubiquitous in the human population; AAV is highly infectious throughout most human tissues; AAV vectors are not replication competent, with genomes remaining primarily episomal for long-term transgene expression; and AAV vectors have been shown in clinical trials to be nontoxic in humans.5,23

Despite AAV vectors being highly attractive in cell therapy, integrating retrovirus vectors and non-integrating adenovirus vectors are currently used for stem-cell therapy applications in the clinic instead of AAV vectors.24 Collective data from various reports offer a potential explanation: the transduction efficiency of AAV vectors in stem cells is highly variable.2,25–35 This statement is intentionally broad, as the reason(s) for such an assertion remain(s) unknown. Over the last three decades, a multitude of studies have presented conflicting reports concerning the capacity of AAV vectors to transduce stem cells efficiently. These reports have primarily focused on three types of stem cells currently used in clinical cell therapy: hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), and pluripotent stem cells (PSCs).

AAV and Human CD34+ Hematopoietic Stem/Progenitor Cells

CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) are one of the most attractive ex vivo gene delivery targets for treatments of numerous diseases, especially certain hematopoietic genetic disorders. Based on the terminology used in previous reports, HSPCs will be defined herein as a (likely heterogeneous) population of cells enriched for the expression of the CD34 cell surface marker that are collected from the bone marrow, peripheral blood, or umbilical cord blood. The earliest successful AAV vector–mediated transduction of human HSPCs was reported in 1994 by different groups. Walsh et al. reported the successful gene correction of primary peripheral blood CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells from Fanconi anemia patients using AAV vectors, which provided some of the earliest and strongest evidence for AAV vectors being able to facilitate gene transfer to primary CD34+ hematopoietic cells.36 Equally convincing was a report demonstrating increased HbF content via AAV vector–mediated gamma-globin expression in peripheral blood CD34+ progenitor-derived colony erythroblasts.37 In the same year, Zhou et al. demonstrated that AAV vectors were capable of transducing cord blood CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells without the need for cytokine stimulation.38 A number of investigators have confirmed and expanded on these findings over the last three decades.39–50 Intensive investigations to develop strategies to assure efficient transduction in HSPCs have been conducted by some laboratories. One of the strategies focuses on exploiting optimal AAV serotypes other than AAV2. For example, Handa et al. investigated the transduction efficiency of AAV3.51 Of particular note, Smith et al. isolated novel AAV from CD34+ HSPCs, which could efficiently transduce human cord blood stem cells and support stable long-term gene expression both in vitro and in vivo.52 More recently, independent laboratories systematically evaluated the transduction efficiency of additional AAV serotype vectors in HSPCs and documented that AAV6 is the most efficient serotype among the 10 commonly used serotypes.42,43 Consistent with these reports, one recent study published in Nature Biotechnology by Wang et al. also identified AAV6 as the capsid variant with the highest tropism for either mobilized peripheral blood or fetal liver CD34+ HSPCs among AAV1, 2, 5, 6, 8, and 9, and demonstrated that AAV6 homologous donor template delivery leads to precise genome editing in human HSPCs.53 Using capsid-modified AAV vectors is another prominent strategy to improve transduction efficacy and lower vector immunogenicity using significantly lower vector doses. For instance, Yang et al. and Sellner et al. generated CD34+ targeted AAV vectors by either inclusion of a chimeric CD34 single-chain antibody-AAV capsid protein or applying an AAV peptide to make capsid mutants.54,55 Song et al. utilized a tyrosine double-mutated AAV vector with an erythroid-specific promoter, which resulted in further augmented transduction efficiency in human primary bone marrow and cord blood CD34+ cells, as well as long-term transgene expression in a murine serial bone-marrow xenograft model, indicating that AAV vectors are minimally toxic to HSPCs if at all.56 By using a tyrosine and threonine triple-mutant AAV6 vector, Ling et al. observed extraordinarily high transduction efficiency in HSPCs at reduced vectors doses by increasing the cell density.40 Scientists also attempted to use self-complementary AAV vectors, which were originally generated by the Samulski group, instead of conventional single-stranded AAV, and documented that self-complementary AAV vectors were more efficient in transducing cord blood–derived CD34+ cells without inducing cytotoxicity or interfering with their differentiation potential, consistent with decades of previous reports.57

By identifying the high tropism for human CD34+ HSPCs, AAV6 has been widely used for genome-editing purposes in HSPCs. For example, Wang et al. achieved high levels of precise genome editing in human HSPCs by a combination of homologous donor template delivery by AAV6 vectors with ZFN mRNA electroporation.53 In addition, Dever et al. utilized the combination of Cas9 ribonucleoproteins and AAV6 delivery of a homologous donor and achieved homologous recombination at the HBB locus in the HSPCs.58 By using co-delivery of megaTAL or TALEN-encoding mRNA and rAAV donor template, another group also achieved 15–20% homologous gene targeting in CD34+ HSPCs.59 Because of these observations and the safer profile, AAV is considered by a number of investigators as the most promising alternative to the more commonly used retroviral vectors and lentiviral vectors in HSPC-based gene therapy for certain diseases.40,57–59

However, conflicting with the above studies, Alexander et al. suggested the possibility that the observed transduction in CD34+ cells could be pseudotransduction by AAV contaminants in the AAV vector stocks.60 By using highly purified AAV vectors, Nathwani et al. observed efficient gene transfer into umbilical cord blood CD34+ cells, including the CD34+CD38- subset, after cytokine stimulation. Yet, the observed transgene expression was transient.61 Malik et al. documented that highly purified AAV vectors are able to transduce hematopoietic progenitor cells with high efficiency but need higher ratios of vector genomes per cell.62 A report by Ellis et al. showed that HSPCs were largely refractory to AAV and suggested that loss of viability post transduction could be a potential explanation.25 Fortunately, some systematic studies have led to the understanding of multiple mechanisms at the molecular level involved in the differential efficacy of AAV transduction, including the wide donor variation in the expression levels of the putative receptor/co-receptor, altered vector trafficking and uncoating, and different rates of intracellular vector degradation,27,49 which will be systematically discussed below. Furthermore, while isolating the cells, some groups used CD34+ as the only selective marker, and some isolated CD34+ and CD38– and/or CD133+ and/or CD90+ subgroups. In addition, CD34+ cells comprise a mixed population of primitive and more differentiated cells, and the ratio of cell subpopulations could vary considerably under different transduction/culture condition. Any of these differences in the transduction process could lead to the observed controversies. Another major consensus to explain the discrepancy is inter-donor variation. In fact, multiple studies have shown that primary CD34+ HSPCs demonstrate large inter-donor variability of AAV vector permissiveness, with transduction efficiencies ranging from 0% to >80%.27,49 This in part could be explained by various states of HSPCs differentiation at the initiation of the experiments, wherein batched results do not convey the single-cell response. Taken together, more investigations to overcome inter-donor variation, or altered culture methods, by understanding the AAV–HSPCs interactions and further studies to assess AAV vector–induced toxicity (if any) in HSPCs are warranted. However, as many reports suggest, AAV vectors are still promising for gene therapy applications involving HSPCs, and the application of this technology in the clinic should be forthcoming.

AAV and Human MSCs

MSCs are highly motile stem cells that primarily reside in the bone marrow and are known to differentiate into nearly all cell types when injected into the blastocyst.63 These stem cells are promising targets for ex vivo gene delivery due to the ease of collection and amplification, along with their high degree of multipotency.64 The first reports of human MSC transduction with AAV vectors were published in 2004 by Ju et al. and Ito et al., although efficient transgene expression required transduction enhancement using genotoxic stressors, such as ultraviolet radiation, hydroxyurea, or etoposide.33,34 Subsequent reports have demonstrated that AAV vectors are capable of efficient transduction of human MSCs without treating cells with genotoxic stressors.65–71 A study by Chng et al. comparing the transduction efficiency of AAV serotypes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 8 in MSCs found that serotype 2 transduces MSCs the most efficiently under the tested conditions.72 Multiple reports have shown that AAV vector transduction of MSCs has great clinical potential, particularly in regenerative medicine. For instance, MSCs overexpressing BMP-7 or transforming growth factor beta 1 following AAV vector transduction can induce osteogenesis and the repair of damaged cartilage, leading to improved healing of damaged joints in vivo.66,73,74 Similarly, the application of MSCs overexpressing VEG165 or miR-375 has shown the ability to promote angiogenesis, increase blood flow, and lead to more complete wound healing in vivo.65,75 Work from the Russell lab combining AAV gene correction and MSCs demonstrated in several reports targeted homologous recombination in MSCs to knock out mutant COL1A1 and, separately, COL1A2 genes toward an autologous approach for the treatment of osteogenesis imperfecta (OI).76,77 Importantly, AAV vector–edited MSCs transduced and characterized ex vivo were able to contribute to bone formation upon transplantation.76,77 This work is among the most pristine demonstrations of the powerful alliance of cell and AAV gene therapy and demonstrates not only the ability to transduce and genetically modify MSCs but also the therapeutic potential as originally envisioned for the combination of AAV and cell therapies. Despite this enthusiasm, minimally for the treatment of OI, the application of this technology as clinical therapy has not been realized, despite almost 15 years passing from that first report. The reasons for this translational speed bump for AAV vectors in stem-cell therapies remain vague, as expedition of AAV gene addition strategies to patients can occur in just a few years. Either way, the collective reports suggest that AAV vector–mediated gene delivery to primary MSCs and, perhaps more elegant, induced gene editing remains a promising technology for the potential treatment of many diseases.

Contrastingly, during the same time, multiple studies reported that the transduction efficiency of AAV vectors in human MSCs is highly variable.31–34 The source of variation in MSC permissiveness to AAV vector transduction is currently unknown. Some studies have suggested that this variation may be due to altered surface receptor expression or altered efficiency of vector genome second-strand synthesis, but no conclusive evidence has been presented for either argument.31,32 The factors that influence whether MSCs require treatment with genotoxic stressors to allow efficient transduction by AAV vectors, as seen in Ju et al. and Ito et al., have also not been resolved, and these unknown factors, such as drug-induced differentiation, may contribute to variability in efficient AAV vector transduction of MSCs.33,34 Furthermore, while transduction of MSCs has been shown in multiple studies, long-term transgene expression and genomic integration in human MSCs has yet to be conclusively demonstrated, currently limiting the clinical prospects of AAV vectors for gene addition in MSC therapy.

AAV Vectors and Human PSCs

Human PSCs, which include hESCs and induced PSCs (iPSCs), have the theoretical potential to become any cell type in the human body. Both ESCs and iPSCs hold tremendous promise for personalized cell replacement therapy, as well as for understanding the mechanisms of various human diseases.78 Therefore, the genetic manipulation of these cells is important for the advent of therapeutic approaches.79 During the past decade, several methods of gene transfer into human PSCs, such as transfection, electroporation, nucleofection, and viral transduction were developed, but these initial reports showed that natural AAV serotypes are typically inefficient in gene delivery to human PSCs.20,80–83

During the first decade of this century, the possibility of cloning humans was alluded to by the combination of enhanced DNA delivery techniques the notion put forth that AAV vector genomes are preferred substrates for homologous recombination. This was in part due to the increased availability of hESCs, along with the advent of designer endonuclease technology in parallel. As such, one of the first demonstrations of AAV gene editing in hESCs was reported by Mitsui et al.22 In that work, targeted AAV vector–induced chromosomal editing was made possible in dissociated hESCs, traditionally grown in landscaped colonies, only in the presence of a ROCK inhibitor to pacify the cells inherent tendency toward apoptosis.22 Thereafter, work from David Russell's lab demonstrated successful gene modification in both hESCs and iPSCs without a ROCK inhibitor after transduction with AAV gene targeting vectors, in a manner reminiscent to their reports of AAV gene editing in MSCs.18 Importantly, their work also was the first time AAV vectors were shown to be able to perform successful gene targeting in differentiated somatic cells before reprogramming into iPSCs.18

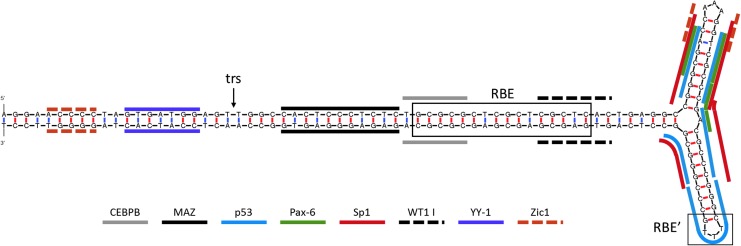

In contrast to these studies, Hirsch et al. have shown that hESCs are extremely sensitive to AAV vector transduction.2 The ITR-induced cellular stress was found to be mediated by a p53-dependent apoptotic response that is elicited by a telomeric sequence within the AAV ITR, which notably contains several putative p53 binding sites and binds p53 in vitro in unpublished data (Fig. 1).2 The vector-induced apoptosis observed by Hirsch et al. occurred in the early S phase, and is speculated to be specific to cells lacking a G1 checkpoint. It is envisioned to be a mechanism to cull mutations in the undifferentiated state.2 In a viral-free system, using DNA microinjections of the ITR sequence, hESCs underwent rapid apoptosis, demonstrating that under the conditions studied therein, the AAV ITR DNA of serotype 2 is sufficient for hESC apoptosis.2 Corroboration of these observations came later from the Hajjar lab, which extends the AAV vector–induced apoptosis to iPSCs, an effect consistent with the apoptotic mechanism proposed a few years earlier.2,35 These seemingly rogue publications of the unexpected AAV vector–induced cellular toxicity followed much earlier reports alluding to this possibility in stem cells, with troubling implications very loosely connecting AAV and premature abortions.4,84 In fact, in one particularly troubling yet largely overlooked study, AAV administration induced complete spontaneous abortion when administered during the first trimester, and not thereafter, in a pregnant mouse model.3 The implications of this study are very serious considering the widespread use of AAV vectors in the clinic, coupled with the potential for vector production in treated patients and subsequent mobilization, in addition to months of vector shedding in urine and seminal fluid following AAV gene therapy in the clinic.

Figure 1.

Select putative transcription factor binding sites of the adeno-associated virus serotype 2 (AAV2) inverted terminal repeat (ITR). The consensus sequence of the AAV2 ITR was analyzed using the mfold web server135 for predicted folding structures and ALGGEN PROMO136,137 for putative transcription factor binding sites. A representative selection of putative transcription factor binding sites is indicated on the sole predicted structure with line overlays (shown above). The Rep binding element (RBE) and the RBE′ are delineated with boxes, and the terminal resolution site (trs) is indicated with an arrow.6–8 Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/hum

Potential Causes of Conflicting Reports of AAV Vector Transduction in Stem Cells

As discussed above, conflicting reports have been published concerning the ability of AAV vectors to transduce stem cells at efficiencies relevant to stem-cell therapy. Ultimately, the mechanism(s) of variation in AAV vector transduction efficiency in stem cells is unknown. An obvious potential culprit is that different labs define, harvest, and culture stem cells in different manners, inadvertently inducing partial differentiation in the entire culture or in a particular subset of cells. In this context, the controversy surrounding the varied results in the literature of AAV vector applications in stem cells is rationalized, yet undermines the universal relevance of many previous reports.

The variable transduction efficiency of AAV vectors in stem cells observed in the literature could be explained by independent or collective differences in the following: the researcher's definition of the particular type of stem cell (i.e., marker identification), stem-cell harvest, stem-cell culture, vector production, and transduction conditions. The sources of stem cells used in studies investigating AAV transduction efficiency vary widely, with no compensation for previously observed inter-donor variability being taken into consideration, and in the case of HSCs and MSCs, stem cells being collected from entirely different tissues. Similarly, studies obtaining stem cells from commercial sources employ no standard to verify consistency between commercial products. Furthermore, current methods of selecting for HSCs and MSCs from patient samples do not ensure (or verify) the pure selection of stem cells from more differentiated progenitor cells, suggesting that these stem-cell cultures contain a heterogeneous population of stem and progenitor cells. In addition to inconsistencies in the collection and selection of stem cells, the cell-culture conditions used in studies investigating the transduction efficiency of AAV vectors in stem cells is variable. The media and media additives used in these studies to culture stem cells is inconsistent, potentially causing stem-cell cultures to exist in different states of differentiation. The time that stem cells spent in culture prior to transduction is also variable between reports, raising the possibility that stem cells left in culture for longer periods of time may demonstrate altered AAV vector transduction characteristics compared to stem cells cultured for shorter periods of time. In the particular instance of PSCs, previous reports have cultured these stem cells in different manners (i.e., single-cell passage vs. small colony dissection and seeding) on different substrates without testing the effect of substrate on PSC transduction by AAV vectors. Along with variations in stem-cell collection and culture, a number of discrepancies exist between reports in the production and purification of AAV vectors that may influence the observed AAV vector transduction of stem cells. The vast majority of reports utilize the “triple transfection method” of producing AAV vectors in HEK293 cells. However, the reagents and protocols used to produce vector vary between reports. Additionally, the method of purifying AAV vectors from cell or nuclear lysates differs across studies, with most studies utilizing either cesium chloride gradient or iodixanol gradient purification. Analogously, previous studies utilized inconsistent methods for dialyzing AAV vector preparations. On top of variations in the preparation of AAV vectors, previous studies investigating the transduction of stem cells by AAV vectors have also used widely varying transduction conditions. Most notably, the number of vector genomes per cell used to transduce stem cells was inconsistent between reports. This issue is exacerbated by the fact that titering AAV vectors accurately and consistently between laboratories remains elusive, meaning that even those studies that report transducing stem cells at the same number of vector genomes per cell may not actually be doing so, and could still observe differences AAV vector transduction of stem cells due to differences in the amount of administered vector. Additionally, the amount of time that stem cells were exposed to AAV vectors differed between reports, which may influence transduction efficiency, even if the same number of vector genomes per cell were applied to the stem-cell cultures. Furthermore, previous work has shown that cell density can influence AAV vector transduction efficiency, and the density of stem-cell cultures was not consistent between reports investigating AAV vector transduction efficiency in stem cells, suggesting that the variability observed in these reports may be due to inconsistent stem-cell culture density. Collectively, the variation present in the literature examining the transduction efficiency of AAV vectors in stem cells may be due to numerous factors, including inconsistencies in stem-cell collection, cell culture, vector preparation, or transduction conditions. These proposed explanations of variability in AAV vector transduction efficiency could influence numerous cellular properties, impacting minimally four aspects of AAV vectorology: cellular entry and trafficking, promoter activity, innate immune response to the vector, and vector toxicity.

AAV Vector Cellular Entry and Trafficking

The permissiveness to AAV vector entry and trafficking may vary between stem-cell cultures and between stem-cell donors, potentially explaining the variation in literature concerning the ability of AAV vectors to transduce stem cells efficiently. The capability of an AAV vector to enter and traffic through a host cell is a major determinant of vector transduction efficiency.85–88 The mechanisms of vector entry and trafficking are not fully understood, but some critical steps within the pathway have been identified. The ability of an AAV vector to enter a cell is primarily mediated by the expression of cellular surface receptors that interact with the vector capsid.89–92 Most AAV serotypes have been shown to interact with specific cellular surface receptors to mediate cellular entry, and, simply put, the variation in cellular surface receptor binding between serotypes grants unique cellular tropisms to each serotype, and could explain variability in different serotypes being able to infect different types of stem cells.93 These results suggest that one potential explanation of the observed variability in AAV vector transduction of stem cells may be inconsistent expression of cellular surface receptors/co-receptors.

The second obstacle to efficient transduction is vector uptake and trafficking through the endosome. Vector entry into the cell occurs through receptor-mediated endocytosis, though the particular form(s) of endocytosis has not been identified and may be cell-type specific.85,92,94–96 The vector remains in the endosome until maturation into a late endosome and acidification. At this point, the N-terminus of the VP1 protein is externalized and opens the endosome membrane via phospholipase activity, releasing the vector into the cytoplasm with a now-exposed nuclear localization signal.85,97,98 Once in the cytoplasm, vectors accumulate perinuclearly by an unknown mechanism likely involving the cytoskeleton.99 Studies have shown that each of these steps can have a large impact on vector transduction efficiency. Yet, little is known if similar pathways exist in less differentiated cells. Preventing endocytosis by inhibiting clatherin or dynamin reduced vector transduction up to 70%, although this reduction in efficiency has been reported to be specific to the cell type, in this case HeLa and 293T cells.95 Proteasome inhibitors have also been shown to enhance transduction efficiency greatly, but whether transduction is increased by preventing capsid degradation or a vector genome–specific effect is not clear.85,100–103 Additionally, obstructing or mutating the N-terminus of the VP1 viral protein prevents endosome escape and reduces transduction, suggesting that endosome escape is an important process for successful transduction.85,101,104,105 Some studies have suggested that endosome trafficking in stem cells is altered compared to differentiated cells. In particular, stem cells perform more rapid endocytosis, with a higher proportion of endosomes becoming recycling endosomes than differentiated cells.106–108 In this case, AAV vectors may be more frequently trafficked through recycling endosomes than late endosomes in stem cells compared to differentiated cells, leading to lower transduction efficiency in stem cells.

Stem-cell transduction by AAV vectors may also be influenced by altered nuclear entry and subsequent processing of the vector. Three critical events have been proposed for nuclear entry and processing: crossing the nuclear membrane, vector uncoating, and second-strand synthesis (for single-stranded vector genomes).109–113 The mechanism by which AAV vectors cross the nuclear membrane is poorly understood. Previous studies have proposed that AAV vectors either may randomly diffuse through the nuclear pores or may be actively shuttled into the nucleus by unknown machinery.109,114 Once through the nuclear membrane, some data support that vectors are transported immediately to the nucleolus, then eventually into the nucleoplasm.110 Before transgene expression is possible, the vector genome must be uncoated from the capsid.111,112 At what point the genome becomes uncoated is unclear, although reports demonstrating AAV vector genome integration into ribosomal DNA sequences typically sequestered to the nucleolus would suggest that vector uncoating occurs at least partially before the vectors exit the nucleolus, or alternatively uncoating occurs elsewhere and the genomes are then transported to areas of active transcription.92,115–117 Following vector uncoating, single-stranded vector genomes must become double-stranded DNA for transcription of the transgene to occur.113,118 Single-stranded genomes are able to become double stranded by two known mechanisms: annealing to a complementary single-stranded genome or by second-strand synthesis.119,120 In the case of second-strand synthesis, the AAV genome ITR hairpin serves as a primer for the host-cell DNA polymerase(s) to replicate the vector genome.121 The rate of vector entry into both the nucleolus and the nucleoplasm has been correlated to the rate and efficiency of vector transduction, suggesting that AAV vector trafficking into the nucleolus and subsequently the nucleoplasm are important rate-limiting steps in AAV vector transduction.110 Stem cells may also show variable transduction by single-stranded AAV vectors due to altered rates of second-strand synthesis, as evidenced by the fact that self-complementary AAV vectors demonstrate 5- to 20-fold more efficient transduction in CD34+ cells.122

Promoter Activity

Variations in promoter activity between cell types may also explain the discrepancy in the literature concerning AAV vector transduction efficiency in stem cells. A number of mechanisms have been found by which promoter activity can be influenced in a cell type–specific manner, for example promoter silencing, altered transcription factor influences, and innate immune system recognition of foreign promoter DNA. Multiple studies have shown that AAV vector transgene expression can be silenced in vivo.123–125 The mechanism by which vector transgenes are silenced is not known. However, these reports suggest that promoters with ubiquitous activity (e.g., cytomegalovirus promoter) are more prone to silencing than cell type–specific promoters.123–126 A number of promoters used in AAV vector cassettes have been shown to be silenced by methylation outside the context of AAV vectors,127–129 but multiple reports suggest that AAV vector transgene silencing is dependent both on cell type and the transgene promoter.123,124,130 These previous reports suggest that the low AAV vector transduction efficiency in stem cells seen in studies using vectors carrying viral promoters with ubiquitous activity may be due to promoter silencing. A study by Okada et al. has also shown that transgene expression can be increased by histone deacytlase inhibitors, although whether the histone deacytlase directly affected the vector genome chromatin or the expression of a factor from the host genome is not clear.130 Stem cells are known to possess a unique environment of epigenetic control over gene expression.131,132 This unique epigenetic status may lead to stem cell–specific silencing of AAV vector genomes, whether by methylation, histone modification, or some other mechanism. The activity of a promoter is also susceptible to host-cell transcription factor expression.133 Stem cells are known to express many transcription factors at different levels from differentiated cells, in particular pluripotency factors such as OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG.133 This altered level of transcription factors may influence the transcriptional activity of promoters used in AAV vector cassettes, as stem cells may possess more or less of a factor required to drive expression from a particular promoter. In addition to promoter sequences, the AAV ITR has been shown to possess inherent promoter activity.134 The presence of ITR promoter activity suggests that transgene expression may be modulated by the interaction of host transcription factors with the vector ITR. As shown in Fig. 1, the AAV2 ITR contains multiple putative transcription factor binding sites, supporting the notion that host-cell transcription factors may interact with the vector ITR and influence transgene expression.135–137 Furthermore, many of the earlier studies investigating AAV vector transduction of stem cells used AAV vector cassettes, which contain a viral promoter (e.g., cytomegalovirus promoter or Rous sarcoma virus promoter). These viral DNA sequences could be recognized by the host cell as a pathogenic antigen, leading to silencing or destruction of the vector genomes via an immune response.138 Stem cells, particularly HSCs and MSCs, are known to be highly sensitive to pathogenic factors.139,140 The exposure of MSCs and HSCs has been shown to induce a wide range of cellular responses, including cellular differentiation, increases in cell motility, and activation of innate immune response pathways.138–140 These results suggest that stem cells may be particularly sensitive to viral DNA sequences, and the use of viral promoters along with the influence of the AAV ITRs could explain the variability in AAV vector transduction efficiency reported in the literature.138–140

Innate Immune Response to AAV Vectors

The response of the cellular innate immune system to AAV vector components other than the transgene promoter may also influence AAV vector transduction in cells in varied states of differentiation. Although a wide array of cellular receptors and signaling pathways are able to recognize and respond to viral elements, the Toll-like receptor (TLR) family of receptors is one of the most prominent and well-studied aspects of the cellular innate immune system.141 The TLR family is comprised of TLR1–TLR11 in humans, with TLR3, TLR7, TLR8, and TLR9 primarily responding to viral infection.142 TLR3 recognizes double-stranded RNA, TLR7 and TLR8 recognize single-stranded RNA, and TLR9 recognizes unmethylated CpG double-stranded DNA.143 The AAV ITRs are CpG rich double-stranded DNA structures (as shown in Fig. 1) reported to act as an antigen for TLR9. Previous studies have shown that AAV vectors are recognized by TLR9 and can lead to the activation of nuclear factor kappaB (NF-kB) signaling.144–146 Activated NF-kB has been shown to drive the expression of p84N5, a protein known to cleave caspase-6 and induce apoptosis in osteosarcoma cells lacking a G1 checkpoint.147 Based on these previous reports, one possible mechanism by which stem cells show variable AAV vector transduction efficiency may be a mutable TLR9 response to the AAV ITRs, which leads to host-cell apoptosis, vector silencing, or degradation.

AAV Vector Toxicity

Another potential source of variability in AAV vector transduction of hESCs is AAV vector toxicity. A small number of studies have presented evidence that AAV vectors induce toxicity in hESCs and stem-like osteosarcoma cells, although the precise mechanism of vector-induced stem-cell death is not well understood.2,35 Previous reports have provided evidence that the AAV ITR elicits a DNA damage response, which induces p53 dependent apoptosis in hESCs.2 Therefore, the difference of AAV vector toxicity between hESCs and more differentiated cells may be due to the differences in DNA damage responses to the ITR, as determined by the degree of cellular differentiation. A large body of evidence exists showing that hESCs are hypersensitive to genotoxic stressors such as ionizing radiation, etoposide, and chemical mutagens, which is consistent with the notion that genetically compromised progenitor cells will be detrimental to the organism and will undergo negative selection.2,148–150 Previous studies have also shown that undifferentiated cells demonstrate altered expression of DNA damage response proteins and apoptotic proteins, and that hESCs are “primed” for apoptosis in response to DNA damage.148,151,152 A novel mechanism of apoptosis in hESCs was reported by Dumitru et al. where constitutively active Bax is localized to the Golgi and rapidly translocates to the mitochondria upon induction of apoptotic signaling.153 This unique state of DNA damage response and apoptotic proteins in hESCs may lead to altered interactions and reactions between the stem cell and the AAV ITRs, potentially explaining the dependence of AAV toxicity on the differentiation status of the host cell. The state of cellular differentiation impacting viral infection is not unprecedented, as other viruses, such as human papilloma virus (HPV), also are affected by cellular differentiation.154 In the case of HPV, the virus maintains a low level of replication in undifferentiated basal cells, but greatly increases replication and virus production as the basal cell differentiates into keratinocytes.155 In addition to altered apoptotic and DNA damage responses, hESCs have also been shown to exhibit atypical cell cycling.156,157 In particular, hESCs have been reported to lack a functional G1 checkpoint.158–160 In 2011, Beard et al. reported that UV-inactivated AAV demonstrated toxicity in osteosarcoma cells that lacked a functional G1 checkpoint, suggesting that AAV toxicity in undifferentiated cells may be due at least in part to atypical cell cycling.160

Another component of AAV vector toxicity in hESCs may involve manipulation of the host-cell environment by AAV vectors. AAV, as well as a host of other viruses (such as HPV, adenovirus, herpes simplex virus [HSV], and other parvoviruses) have been shown to manipulate and utilize DNA damage repair and cell cycling machinery from the host cell to facilitate virus reproduction.161,162 The exact ways in which AAV influences the host-cell environment are poorly understood due to the fact that previous studies have examined AAV host environment manipulation only in the context of co-infection with adenovirus or HSV, which also manipulate the host-cell environment.163,164 However, host-cell environment manipulations performed by other viruses are better understood. HSV and HPV are both known to inhibit all DNA damage repair pathways other than homologous recombination, which is postulated to be necessary for processing viral genomes during replication.165–168 Parvoviruses other than AAV, such as B19, are also known to influence the DNA damage repair machinery, as well as elicit a DNA damage response and apoptosis, although exactly how the virus influences the cellular machinery depends on the particular virus.169,170 Parvoviruses, HSV, and HPV are also known to manipulate cellular machinery to enforce favorable cell-cycling conditions, such as rapid cell replication, even in differentiated cells. These viruses degrade cell cycle control proteins, such as p53 and retinoblastoma, in order to force cells to remain cycling and replicate viral genomes in S phase, which may or may not be related to AAV vector toxicity in cells deficient for a G1 checkpoint.165–170 Based on these previous reports, AAV vectors may also interact with and manipulate the host-cell DNA damage repair and cell cycle machinery, and induce apoptosis in hESCs like other parvoviruses.

The fact that AAV vectors demonstrate toxicity in hESCs not only could explain how hESCs are refractory to AAV vector transduction, but also has very serious clinical ramifications. AAV vectors have been suggested to pose a risk to developing embryos, as evidenced by the consistent induction of abortion when AAV was injected into pregnant mice in the first trimester of pregnancy.3 In addition, multiple studies have found AAV in human spontaneous abortion material at a significantly higher rate than expected, suggesting that AAV may induce abortion of human embryos naturally.171,172 However, AAV is known to travel with helper viruses in natural infections, and the induction of spontaneous abortion could be due to the infection of the embryo by one of these helper viruses with AAV being a bystander.172 The concern for AAV vector safety in embryo development is made more serious by the possibility of AAV vector mobilization, especially with increased clinical usage. Previous studies have shown that AAV vectors can be found in the urine, semen, and blood serum of human patients several months post injection with vectors, showing that AAV vectors can be shed from patients into the environment.173,174 Furthermore, evidence for potential AAV vector production within the patient and in bystanders suggests that AAV vectors could propagate indefinitely in the human population.175 Despite the safety concerns raised by potential AAV vector toxicity in stem cells, AAV vector toxicity has potential clinical utility. Previous work has shown that tumors are comprised of heterogeneous populations of cells that may originate or be propagated by a subpopulation of stem-like cancer cells.176 The current literature supports the notion that these stem-like cancer cells are responsible for tumor resistance to chemotherapeutics and seed tumor recurrence following many traditional cancer treatments, including chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and surgical tumor removal.176 As AAV vectors have been reported to show toxicity in stem and stem-like cells previously,2,6,135 stem-like cancer cells may also demonstrate toxicity in response to infection by AAV vectors. If AAV vectors are toxic to stem-like cancer cells, then AAV vectors could potentially be used as an adjuvant therapy to supplement current cancer therapies to minimize tumor recurrence.

The current literature indicates that AAV vectors are promising tools for gene therapy applications involving HSCs and MSCs, but these applications may be restricted in hESCs due to vector-induced cytotoxicity. Further investigations of the mechanism of AAV vector transduction in stem cells and stem-like cells may allow the creation the vectors that can reliably and efficiently transduce a broad range of undifferentiated cell types. The study of the mechanism of stem-cell transduction will minimally reveal insights into the poorly characterized AAV vector biology. Ideally, these experiments may have ramifications for the treatment of cancer and could lead to the development of AAV vectors that can consistently transduce stem cells, allowing the use of AAV vectors for delivering therapeutic DNA to stem cells for use in stem-cell therapy. By using these approaches, AAV vector–mediated stem-cell therapy could open a new era for the treatment of a multitude of diseases in the near future.

Acknowledgment

Funding was providing by the National Institutes of Health (RO1AI072176-06A1, RO1AR064369-01A1).

Author Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Asokan A, Conway JC, Phillips JL, et al. Reengineering a receptor footprint of adeno-associated virus enables selective and systemic gene transfer to muscle. Nat Biotechnol 2010;28:79–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirsch ML, Fagan BM, Dumitru R, et al. Viral single-strand DNA induces p53-dependent apoptosis in human embryonic stem cells. PLoS One 2011;6:e27520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Botquin V, Cid-Arregui A, Schlehofer JR. Adeno-associated virus type 2 interferes with early development of mouse embryos. J Gen Virol 1994;75:2655–2662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman-Einat M, Grossman Z, Mileguir F, et al. Detection of adeno-associated virus type 2 sequences in the human genital tract. J Clin Microbiol 1997;35:71–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samulski RJ, Muzyczka N. AAV-mediated gene therapy for research and therapeutic purposes. Ann Rev Virol 2014;1:427–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie Q, Bu W, Bhatia S, et al. The atomic structure of adeno-associated virus (AAV-2), a vector for human gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002;99:10405–10410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grieger JC, Samulski RJ. Packaging caapacity of adeno-associated virus serotypes: impact of larger genomes on infectivity and postentry steps. J Virol 2005;79:9933–9944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonçalves MA. Adeno-associated virus: from defective virus to effective vector. Virol J 2005;2:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao G, Vandenberghe L, Wilson J. New recombinant serotypes of AAV vectors. Curr Gene Ther 2005;5:285–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi VW, McCarty DM, Samulski RJ. AAV hybrid serotypes: improved vectors for gene delivery. Curr Gene Ther 2005;5:299–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samulski RJ, Berns KI, Tan M, et al. Cloning of adeno-associated virus into pBR322: rescue of intact virus from the recombinant plasmid in human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1982;79:2077–2081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samulski RJ, Chang LS, Shenk T. Helper-free stocks of recombinant adeno-associated viruses: normal integration does not require viral gene expression. J Virol 1989;63:3822–3828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirata RK, Russell DW. Design and packaging of adeno-associated virus gene targeting vectors. J Virol 2000;74:4612–4620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Z, Ma HI, Li J, et al. Rapid and highly efficient transduction by double-stranded adeno-associated virus vectors in vitro and in vivo. Gene Ther 2003;10:2105–2111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCarty DM, Monahan PE, Samulski RJ. Self-complementary recombinant adeno-associated virus (scAAV) vectors promote efficient transduction independently of DNA synthesis. Gene Ther 2001;8:1248–1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins M, Thrasher A. Gene therapy: progress and predictions. Proc Biol Sci 2015;282:20143003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russell DW, Hirata RK. Human gene targeting by viral vectors. Nat Genet 1998;18:325–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan IF, Hirata RK, Russell DW. AAV-mediated gene targeting methods for human cells. Nat Protoc 2011;6:482–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirsch ML, Samulski RJ. AAV-mediated gene editing via double-strand break repair. Methods Mol Biol 2014;1114:291–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asuri P, Bartel MA, Vazin T, et al. Directed evolution of adeno-associated virus for enhanced gene delivery and gene targeting in human pluripotent stem cells. Mol Ther 2012;20:329–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan IF, Hirata RK, Wang P-R, et al. Engineering of human pluripotent stem cells by AAV-mediated gene targeting. Mol Ther 2010;18:1192–1199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitsui K, Suzuki K, Aizawa E, et al. Gene targeting in human pluripotent stem cells with adeno-associated virus vectors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009;388:711–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiao X, Li J, Samulski RJ. Efficient long-term gene transfer into muscle tissue of immunocompetent mice by adeno-associated virus vector. J Virol 1996;70:8098–8108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vollweiler JL, Zielske SP, Reese JS, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy: progress toward therapeutic targets. Bone Marrow Transplant 2003;32:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ellis BL, Hirsch ML, Barker JC, et al. A survey of ex vivo/in vitro transduction efficiency of mammalian primary cells and cell lines with nine natural adeno-associated virus (AAV1-9) and one engineered adeno-associated virus serotype. Virol J 2013;10:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Veldwijk MR, Sellner L, Stiefelhagen M, et al. Pseudotyped recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors mediate efficient gene transfer into primary human CD34+ peripheral blood progenitor cells. Cytotherapy 2010;12:107–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ponnazhagan S, Mukherjee P, Wang XS, et al. Adeno-associated virus type 2-mediated transduction in primary human bone marrow-derived CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells: donor variation and correlation of transgene expression with cellular differentiation. J Virology 1997;71:8262–8267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qing K, Mah C, Hansen J, et al. Human fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 is a co-receptor for infection by adeno-associated virus 2. Nat Med 1999;5:71–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bartlett JS, Kleinschmidt J, Boucher RC, et al. Targeted adeno-associated virus vector transduction of nonpermissive cells mediated by a bispecific F(ab'γ)2 antibody. Nat Biotechnol 1999;17:181–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Handa A, Muramatsu S, Qiu J, et al. Adeno-associated virus (AAV)-3-based vectors transduce haematopoietic cells not susceptible to transduction with AAV-2-based vectors. J Gen Virol 2000;81:2077–2084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li M, Jayandharan GR, Li B, et al. High-efficiency transduction of fibroblasts and mesenchymal stem cells by tyrosine-mutant AAV2 vectors for their potential use in cellular therapy. Hum Gene Ther 2010;21:1527–1543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McMahon JM, Conroy S, Lyons M, et al. Gene transfer into rat mesenchymal stem cells: a comparative study of viral and nonviral vectors. Stem Cell Dev 2006;15:87–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ito H, Goater JJ, Tiyapatanaputi P, et al. Light-activated gene transduction of recombinant adeno-associated virus in human mesenchymal stem cells. Gene Ther 2004;11:34–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ju X, Lou S, Wang W, et al. Effect of hydroxyurea and etoposide on transduction of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem and progenitor cell by adeno-associated virus vectors. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2004;25:196–202 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rapti K, Stillitano F, Karakikes I, et al. Effectiveness of gene delivery systems for pluripotent and differentiated cells. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2015;2:14067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walsh CE, Nienhuis AW, Samulski RJ, et al. Phenotypic correction of Fanconi anemia in human hematopoietic cells with a recombinant adeno-associated virus vector. J Clin Invest 1994;94:1440–1448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller JL, Donahue RE, Sellers SE, et al. Recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV)-mediated expression of a human gamma-globin gene in human progenitor-derived erythroid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994;91:10183–10187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou SZ, Cooper S, Kang LY, et al. Adeno-associated virus 2-mediated high efficiency gene transfer into immature and mature subsets of hematopoietic progenitor cells in human umbilical cord blood. J Exp Med 1994;179:1867–1875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goodman S, Xiao X, Donahue RE, et al. Recombinant adeno-associated virus-mediated gene transfer into hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood 1994;84:1492–1500 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ling C, Bhukhai K, Yin Z, et al. High-efficiency transduction of primary human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells by AAV6 vectors: strategies for overcoming donor-variation and implications in genome editing. Sci Rep 2016;6:35495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kauss MA, Smith LJ, Zhong L, et al. Enhanced long-term transduction and multilineage engraftment of human hematopoietic stem cells transduced with tyrosine-modified recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 2. Hum Gene Ther 2010;21:1129–1136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Veldwijk MR, Sellner L, Stiefelhagen M, et al. Pseudotyped recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors mediate efficient gene transfer into primary human CD34(+) peripheral blood progenitor cells. Cytotherapy 2010;12:107–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Song L, Kauss MA, Kopin E, et al. Optimizing the transduction efficiency of human hematopoietic stem cells using capsid-modified AAV6 vectors in vitro and in a xenograft mouse model in vivo. Cytotherapy 2013;15:986–998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Belay E, Dastidar S, VandenDriessche T, et al. Transposon-mediated gene transfer into adult and induced pluripotent stem cells. Curr Gene Ther 2011;11:406–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kurpad C, Mukherjee P, Wang XS, et al. Adeno-associated virus 2-mediated transduction and erythroid lineage-restricted expression from parvovirus B19p6 promoter in primary human hematopoietic progenitor cells. J Hematother Stem Cell Res 1999;8:585–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ponnazhagan S, Weigel KA, Raikwar SP, et al. Recombinant human parvovirus B19 vectors: erythroid cell-specific delivery and expression of transduced genes. J Virol 1998;72:5224–5230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang XS, Yoder MC, Zhou SZ, et al. Parvovirus B19 promoter at map unit 6 confers autonomous replication competence and erythroid specificity to adeno-associated virus 2 in primary human hematopoietic progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995;92:12416–12420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Broxmeyer HE, Cooper S, Etienne-Julan M, et al. Cord blood transplantation and the potential for gene therapy. Gene transduction using a recombinant adeno-associated viral vector. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1995;770:105–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chatterjee S, Li W, Wong CA, et al. Transduction of primitive human marrow and cord blood-derived hematopoietic progenitor cells with adeno-associated virus vectors. Blood 1999;93:1882–1894 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Santat L, Paz H, Wong C, et al. Recombinant AAV2 transduction of primitive human hematopoietic stem cells capable of serial engraftment in immune-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102:11053–11058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Handa A, Muramatsu S, Qiu J, et al. Adeno-associated virus (AAV)-3-based vectors transduce haematopoietic cells not susceptible to transduction with AAV-2-based vectors. J Gen Virol 2000;81:2077–2084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith LJ, Ul-Hasan T, Carvaines SK, et al. Gene transfer properties and structural modeling of human stem cell-derived AAV. Mol Ther 2014;22:1625–1634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang J, Exline CM, DeClercq JJ, et al. Homology-driven genome editing in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells using ZFN mRNA and AAV6 donors. Nat Biotechnol 2015;33:1256–1263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang Q, Mamounas M, Yu G, et al. Development of novel cell surface CD34-targeted recombinant adenoassociated virus vectors for gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther 1998;9:1929–1937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sellner L, Stiefelhagen M, Kleinschmidt JA, et al. Generation of efficient human blood progenitor-targeted recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors (AAV) by applying an AAV random peptide library on primary human hematopoietic progenitor cells. Exp Hematol 2008;36:957–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Song L, Li X, Jayandharan GR, et al. High-efficiency transduction of primary human hematopoietic stem cells and erythroid lineage-restricted expression by optimized AAV6 serotype vectors in vitro and in a murine xenograft model in vivo. PloS One 2013;8:e58757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schuhmann NK, Pozzoli O, Sallach J, et al. Gene transfer into human cord blood-derived CD34(+) cells by adeno-associated viral vectors. Exp Hematol 2010;38:707–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dever DP, Bak RO, Reinisch A, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 beta-globin gene targeting in human haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 2016;539:384–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sather BD, Ibarra GSR, Sommer K, et al. Efficient modification of CCR5 in primary human hematopoietic cells using a megaTAL nuclease and AAV donor template. Science Transl Med 2015;7:307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alexander IE, Russell DW, Miller AD. Transfer of contaminants in adeno-associated virus vector stocks can mimic transduction and lead to artifactual results. Hum Gene Ther 1997;8:1911–1920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nathwani AC, Hanawa H, Vandergriff J, et al. Efficient gene transfer into human cord blood CD34+ cells and the CD34+CD38- subset using highly purified recombinant adeno-associated viral vector preparations that are free of helper virus and wild-type AAV. Gene Ther 2000;7:183–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Malik P, McQuiston SA, Yu XJ, et al. Recombinant adeno-associated virus mediates a high level of gene transfer but less efficient integration in the K562 human hematopoietic cell line. J Virol 1997;71:1776–1783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jiang Y, Jahagirdar BN, Reinhardt RL, et al. Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow. Nature 2002;418:41–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Uccelli A, Moretta L, Pistoia V. Mesenchymal stem cells in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2008;8:726–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sheng W, Feng Z, Song Q, et al. Modulation of mesenchymal stem cells with miR-375 to improve their therapeutic outcome during scar formation. Am J Transl Res 2016;8:2079–2087 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pagnotto MR, Wang Z, Karpie JC, et al. Adeno-associated viral gene transfer of transforming growth factor-β1 to human mesenchymal stem cells improves cartilage repair. Gene Ther 2007;14:804–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim JH, Park S-N, Suh H. Generation of insulin-producing human mesenchymal stem cells using recombinant adeno-associated virus. Yonsei Med J 2007;48:109–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gabriel N, Samuel R, Jayandharan GR. Targeted delivery of AAV-transduced mesenchymal stromal cells to hepatic tissue for ex vivo gene therapy. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2015. June 5 DOI: 10.1002/term.2034 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bao C, Guo J, Lin G, et al. TNFR gene-modified mesenchymal stem cells attenuate inflammation and cardiac dysfunction following MI. Scand Cardiovasc J 2008;42:56–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kumar S, Mahendra G, Nagy TR, et al. Osteogenic differentiation of recombinant adeno-associated virus 2-transduced murine mesenchymal stem cells and development of an immunocompetent mouse model for ex vivo osteoporosis gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther 2004;15:1197–1206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang Q, Zhang Z, Ding T, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing PEDF decrease the angiogenesis of gliomas. Biosci Rep 2013;33:e00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chng K, Larsen SR, Zhou S, et al. Specific adeno-associated virus serotypes facilitate efficient gene transfer into human and non-human primate mesenchymal stromal cells. J Gene Med 2007;9:22–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kang Y, Liao W, Yuan Z, et al. In vitro and in vivo induction of bone formation based on adeno-associated virus-mediated BMP-7 gene therapy using human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2007;28:839–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wei G, An G, Shi Z, et al. Suppression of microRNA-383 enhances therapeutic potential of human bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in treating spinal cord injury via GDNF. Cell Physiol Biochem 2017;41:1435–1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shevchenko EK, Makarevich PI, Tsokolaeva ZI, et al. Transplantation of modified human adipose derived stromal cells expressing VEGF165 results in more efficient angiogenic response in ischemic skeletal muscle. J Transl Med 2013;11:138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chamberlain JR, Schwarze U, Wang PR, et al. Gene targeting in stem cells from individuals with osteogenesis imperfecta. Science 2004;303:1198–1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chamberlain JR, Deyle DR, Schwarze U, et al. Gene targeting of mutant COL1A2 alleles in mesenchymal stem cells from individuals with osteogenesis imperfecta. Mol Ther 2008;16:187–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kimbrel EA, Lanza R. Pluripotent stem cells: the last 10 years. Regen Med 2016;11:831–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hendriks WT, Warren CR, Cowan CA. Genome editing in human pluripotent stem cells: approaches, pitfalls, and solutions. Cell Stem Cell 2016;18:53–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Braam SR, Denning C, van den Brink S, et al. Improved genetic manipulation of human embryonic stem cells. Nat Methods 2008;5:389–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cao F, Xie X, Gollan T, et al. Comparison of gene-transfer efficiency in human embryonic stem cells. Mol Imaging Biol 2010;12:15–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Moore JC, Atze K, Yeung PL, et al. Efficient, high-throughput transfection of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther 2010;1:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hohenstein KA, Pyle AD, Chern JY, et al. Nucleofection mediates high-efficiency stable gene knockdown and transgene expression in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 2008;26:1436–1443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ding W, Zhang L, Yan Z, et al. Intracellular trafficking of adeno-associated viral vectors. Gene Ther 2005;12:873–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xiao P, Samulski RJ. Cytoplasmic trafficking, endosomal escape, and perinuclear accumulation of adeno-associated virus type 2 particles are facilitated by microtubule network. J Virol 2012;86:10462–10473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhong L, Li W, Yang Z, et al. Impaired nuclear transport and uncoating limit recombinant adeno-associated virus 2 vector-mediated transduction of primary murine hematopoietic cells. Hum Gene Ther 2004;15:1207–1218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Douar A, Poulard K, Stockholm D, et al. Intracellular trafficking of adeno-associated virus vectors: routing to the late endosomal compartment and proteasome degradation. J Virol 2001;75:1824–1833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vihinen-Ranta M, Suikkanen S, Parrish CR. Pathways of cell infection by parvoviruses and adeno-associated viruses. J Virol 2004;78:6709–6714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Summerford C, Samulski RJ. Membrane-associated heparan sulfate proteoglycan is a receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 virions. J Virol 1998;72:1438–1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.O'Donnell J, Taylor KA, Chapman MS. Adeno-associated virus-2 and its primary cellular receptor—cryo-EM structure of a heparin complex. Virology 2009;385:434–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bartlett JS, Wilcher R, Samulski RJ. Infectious entry pathway of adeno-associated virus and adeno-associated virus vectors. J Virol 2000;74:2777–2785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Murlidharan G, Samulski RJ, Asokan A. Biology of adeno-associated viral vectors in the central nervous system. Front Mol Neurosci 2014;7:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kaminsky PM, Keiser NW, Yan Z, et al. Directing integrin-linked endocytosis of recombinant AAV enhances productive FAK-dependent transduction. Mol Ther 2012;20:972–983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nonnenmacher M, Weber T. Adeno-associated virus 2 infection requires endocytosis through the CLIC/GEEC pathway. Cell Host Microbe 2011;10:563–576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sanlioglu S, Benson PK, Yang J, et al. Endocytosis and nuclear trafficking of adeno-associated virus type 2 are controlled by Rac1 and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase activation. J Virol 2000;74:9184–9196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Girod A, Wobus CE, Zádori Z, et al. The VP1 capsid protein of adeno-associated virus type 2 is carrying a phospholipase A2 domain required for virus infectivity. J Gen Virol 2002;83:973–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Stahnke S, Lux K, Uhrig S, et al. Intrinsic phospholipase A2 activity of adeno-associated virus is involved in endosomal escape of incoming particles. Virology 2011;409:77–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Grieger JC, Snowdy S, Samulski RJ. Separate basic region motifs within the adeno-associated virus capsid proteins are essential for infectivity and assembly. J Virol 2006;80:5199–5210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Duan D, Yue Y, Yan Z, et al. Endosomal processing limits gene transfer to polarized airway epithelia by adeno-associated virus. J Clin Invest 2000;105:1573–1587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Johnson JS, Li C, DiPrimio N, et al. Mutagenesis of adeno-associated virus type 2 capsid protein VP1 uncovers new roles for basic amino acids in trafficking and cell-specific transduction. J Virol 2010;84:8888–8902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Monahan PE, Lothrop CD, Sun J, et al. Proteasome inhibitors enhance gene delivery by AAV virus vectors expressing large genomes in hemophilia mouse and dog models: a strategy for broad clinical application. Mol Ther 2010;18:1907–1916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhang FL, Jia SQ, Zheng SP, et al. Celastrol enhances AAV1-mediated gene expression in mice adipose tissues. Gene Ther 2011;18:128–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Popa-Wagner R, Porwal M, Kann M, et al. Impact of VP1-specific protein sequence motifs on adeno-associated virus type 2 intracellular trafficking and nuclear entry. J Virol 2012;86:9163–9174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Grieger JC, Johnson JS, Gurda-Whitaker B, et al. Surface-exposed adeno-associated virus Vp1-NLS capsid fusion protein rescues infectivity of noninfectious wild-type Vp2/Vp3 and Vp3-only capsids but not that of fivefold pore mutant virions. J Virol 2007;81:7833–7843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nicolson SC, Samulski RJ. Recombinant adeno-associated virus utilizes host cell nuclear import machinery to enter the nucleus. J Virol 2014;88:4132–4144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pelekanos RA, Ting MJ, Sardesai VS, et al. Intracellular trafficking and endocytosis of CXCR4 in fetal mesenchymal stem/stromal cells. BMC Cell Biol 2014;15:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhang Y, Foudi A, Geay JF, et al. Intracellular localization and constitutive endocytosis of CXCR4 in human CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells. Stem Cells 2004;22:1015–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Furthauer M, Gonzalez-Gaitan M. Endocytosis, asymmetric cell division, stem cells and cancer: unus pro omnibus, omnes pro uno. Mol Oncol 2009;3:339–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Johnson JS, Samulski RJ. Enhancement of adeno-associated virus infection by mobilizing capsids into and out of the nucleolus. J Virol 2009;83:2632–2644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Thomas CE, Storm TA, Huang Z, et al. Rapid uncoating of vector genomes is the key to efficient liver transduction with pseudotyped adeno-associated virus vectors. J Virol 2004;78:3110–3122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sipo I, Fechner H, Pinkert S, et al. Differential internalization and nuclear uncoating of self-complementary adeno-associated virus pseudotype vectors as determinants of cardiac cell transduction. Gene Therapy 2007;14:1319–1329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ferrari FK, Samulski T, Shenk T, et al. Second-strand synthesis is a rate-limiting step for efficient transduction by recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors. J Virol 1996;70:3227–3234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kelich JM, Ma J, Dong B, et al. Super-resolution imaging of nuclear import of adeno-associated virus in live cells. Mol Ther 2015;2:15047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Seisenberger G, Ried MU, Endre T, et al. Real-time single-molecule imaging of the infection pathway of an adeno-associated virus. Science 2001;294:1929–1932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lisowski L, Lau A, Wang Z, et al. Ribosomal DNA integrating rAAV-rDNA vectors allow for stable transgene expression. Mol Ther 2012;20:1912–1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wang Z, Lisowski L, Finegold MJ, et al. AAV vectors containing rDNA homology display increased chromosomal integration and transgene persistence. Mol Ther 2012;20:1902–1911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Zhou X, Zeng X, Fan Z, et al. Adeno-associated virus of a single-polarity DNA genome is capable of transduction in vivo. Mol Ther 2008;16:494–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Fisher-Adams G, Wong KK, Jr, Podsakoff G, et al. Integration of adeno-associated virus vectors in CD34+ human hematopoietic progenitor cells after transduction. Blood 1996;88:492–504 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Nakai H, Storm TA, Kay MA. Recruitment of single-stranded recombinant adeno-associated virus vector genomes and intermolecular recombination are responsible for stable transduction of liver in vivo. J Virol 2000;74:9451–9463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Hauswirth WW, Berns KI. Origin and termination of adeno-associated virus DNA replication. Virology 1977;78:488–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Bevington JM, Needham PG, Verrill KC, et al. Adeno-associated virus interactions with B23/nucleophosmin: identification of sub-nucleolar virion regions. Virology 2007;357:102–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Schuhmann NK, Pozzoli O, Sallach J, et al. Gene transfer into human cord blood–derived CD34+ cells by adeno-associated viral vectors. Exp Hematol 2010;38:707–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Klein RL, Meyer EM, Peel AL, et al. Neuron-specific transduction in the rat septohippocampal or nigrostriatal pathway by recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors. Exp Neurol 1998;150:183–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gray SJ, Foti SB, Schwartz JW, et al. Optimizing promoters for recombinant adeno-associated virus-mediated gene expression in the peripheral and central nervous system using self-complementary vectors. Hum Gene Ther 2011;22:1143–1153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Paterna JC, Moccetti T, Mura A, et al. Influence of promoter and WHV post-transcriptional regulatory element on AAV-mediated transgene expression in the rat brain. Gene Ther 2000;7:1304–1311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Tolmachov OE, Subkhankulova T, Tolmachova T. Silencing of transgene expression: a gene therapy perspective. In: Molina FM, ed. Gene Therapy—Tools and Potential Applications. www.intechopen.com/books/gene-therapy-tools-and-potential-applications/silencing-of-transgene-expression-a-gene-therapy-perspective (last accessed March3, 2017)

- 127.Prösch S, Stein J, Staak K, et al. Inactivation of the very strong HCMV immediate early promoter by DNA CpG methylation in vitro. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler 1996;377:195–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kong Q, Wu M, Huan Y, et al. Transgene expression is associated with copy number and cytomegalovirus promoter methylation in transgenic pigs. PLoS One 2009;4:e6679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Gerolami R, Uch R, Jordier F, et al. Gene transfer to hepatocellular carcinoma: transduction efficacy and transgene expression kinetics by using retroviral and lentiviral vectors. Cancer Gene Ther 2000;7:1286–1292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Okada T, Uchibori R, Iwata-Okada M, et al. A histone deacetylase inhibitor enhances recombinant adeno-associated virus-mediated gene expression in tumor cells. Mol Ther 2006;13:738–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Li M, Liu G-H, Belmonte JC. Navigating the epigenetic landscape of pluripotent stem cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2012;13:524–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 2007;131:861–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Chen D, Murphy B, Sung R, et al. Adaptive and innate immune responses to gene transfer vectors: role of cytokines and chemokines in vector function. Gene Ther 2003;10:991–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Flotte TR, Afione SA, Solow R, et al. Expression of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator from a novel adeno-associated virus promoter. J Biol Chem 1993;268:3781–3790 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Zuker M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res 2003;31:3406–3415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]