Abstract

Disclosed herein is the first general chemo‐ and site‐selective alkylation of C−Br bonds in the presence of COTf, C−Cl and other potentially reactive functional groups, using the air‐, moisture‐, and thermally stable dinuclear PdI catalyst, [Pd(μ‐I)PtBu3]2. The bromo‐selectivity is independent of the substrate and the relative positioning of the competing reaction sites, and as such fully predictable. Primary and secondary alkyl chains were introduced with extremely high speed (<5 min reaction time) at room temperature and under open‐flask reaction conditions.

Keywords: homogeneous catalysis, chemoselectivity, Csp2–Csp3 coupling, dimers, palladium

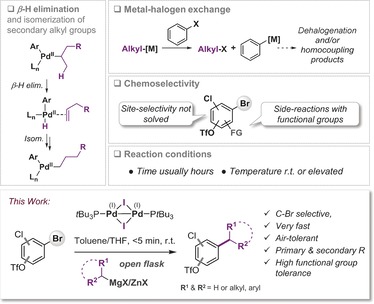

Csp2–Csp3 cross‐coupling reactions are key transformations to access valuable feedstock material for synthesis, materials, as well as for the pharmaceutical and agrochemical arenas. Consequently, there has been a tremendous interest in devising efficient methodologies to achieve this feat.1 While remarkable progress has been made with transition‐metal catalysis,2 Pd‐based methodology frequently offers superior generality and mildness—a prerequisite to access richly functionalized building blocks for further synthetic transformations.3 Among the key challenges in Pd‐catalyzed alkylations is the possibility for β‐hydride elimination from [PdII]‐alkyl intermediates and isomerization of the coupling partner, resulting in product mixtures (Figure 1).2a Additionally, the nucleophilic/basic organometallic cross‐coupling partners that are generally employed (i.e. RMgX or RZnX) are frequently unstable and may be incompatible with additional functionalities in the substrate, particularly under prolonged reaction times and/or elevated temperatures.

Figure 1.

Key challenges in Pd‐catalyzed alkylation reactions.

While impressive progress has been made in minimizing side‐reactions,4 as well as addressing the handling and preparation of the cross‐coupling partner,5 to date, no general and chemoselective alkylation of poly(pseudo)halogenated arenes has been accomplished.6 This situation may be of little surprise, as even the more facile Csp2–Csp2 coupling has until our recent report8 been a long‐standing challenge; the overall site‐selectivity in typical Pd0‐based methodology is substrate‐, ligand‐, and condition dependent.7

We recently disclosed that the application of the air‐, moisture‐ and thermally stable iodide‐bridged dinuclear PdI catalyst 1 allows for a substrate‐independent, chemoselective arylation of poly(pseudo)‐halogenated arenes.8 Encouraged by these findings, this report discloses our efforts to address the greater challenge of site‐selective alkylation, which would be highly desired in the context of synthetic diversity and to allow orthogonal, programmable, and sequential synthetic approaches.9

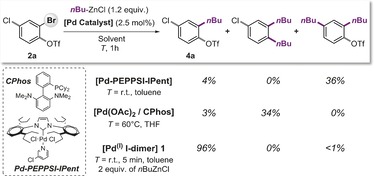

Owing to their relative mildness, alkylzinc reagents are the preferred coupling partners in Pd‐catalyzed alkylations of aryl (pseudo)halides.2a In this context, the commercially available NHC (N‐heterocyclic carbene)‐based and biaryl phosphine‐based Pd‐precatalysts developed by the groups of Organ and Buchwald have been applied in versatile alkylations of aryl bromides, chlorides or triflates at room temperature or 60 °C in 0.5–2 hours.4c,4e,4f As there has not been any report of a chemoselective alkylation method, we initially assessed the performance of these highly successful catalyst systems and conditions for their potential to site‐selectively alkylate substrate 2 a, which displays competing C−Br, C−Cl and C−OTf sites, with n‐butylzinc chloride (Figure 2). Both catalyst systems were unselective and generated bis‐alkylated products in mixtures with starting material. Interestingly, while the biarylphosphine (CPhos) system predominantly gave rise to the product resulting from C−OTf and C−Br alkylation, the NHC (IPent) system showed simultaneous C−Br and C−Cl alkylation instead.10 Both ligands are generally presumed to form a low coordinate “Pd0L1” active species, and would therefore be expected to result in analogous site‐selectivities.11 This may hint toward mixtures of different reactive species, for example, through coordination of the nucleophilic coupling partner to the Pd0 species to generate anionic Pd0LX−,12 which likely displays different selectivity. 7e,7g Indeed, the majority of Csp2–Csp2 Kumada and Negishi couplings resulted in predominant coupling at C−OTf over C−Br. 7a

Figure 2.

Site‐selectivity of Negishi alkylation with commercially available Pd (pre‐)catalysts10 including 1.

We envisioned that a coupling concept based on PdI could be advantageous in this context.13 If the alkyl coupling partner was incorporated as the bridging unit via iodide/alkyl exchange in the dinuclear entity, the resulting transient alkyl‐bridged PdI dimer might selectively react and also allow us to circumvent the intermediacy of [PdII]‐alkyl species and potential side reactions. Thus, we tested the air‐stable PdI dimer 1 (2.5 mol %) in the coupling of substrate 2 a with n‐butylzinc chloride at room temperature in toluene.14 The reaction was extremely rapid, having reached full conversion of 2 a in less than 5 min reaction time (see Figure 2. To our delight, the reaction proved to be completely selective and yielded the product resulting from C−Br alkylation in 96 % yield. Both the C−Cl and C−OTf sites remained untouched. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first example of a selective Negishi alkylation that does not react with the C−OTf site.6 Importantly, the transformation was also tolerant to air, yielding the same reaction outcome under inert and open‐flask conditions.15

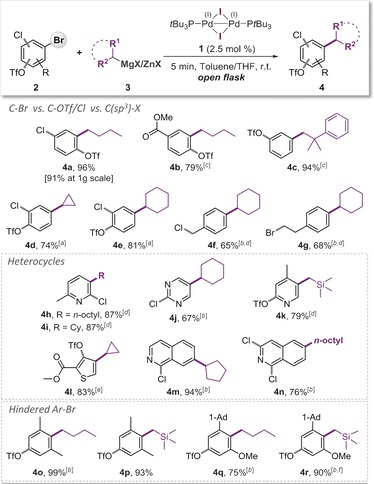

Encouraged by this exceptional selectivity along with high practicality, we subsequently explored the generality of the observed C−Br coupling preference. We observed exclusive alkylation of the C−Br bond, independent of its relative positioning to the competing reaction sites or the nature of the alkylating reagent (i.e. primary vs. secondary alkylzinc, see Scheme 1). Selective functionalization of bromide occurred in ortho, meta, and para positions to C−OTf, and also in the presence of C−Cl (4 a–4 e, Scheme 1), allowing the isolation of the corresponding Csp2–Csp3 coupled products in high yields. The C−Br coupling also proved to be equally selective and efficient for more hindered C−Br sites (entries 4 o–4 r), as well as for pharmaceutically and agrochemically relevant heterocycles. Selection for C−Br occurred in all cases, leaving the more activated C−OTf and C−Cl sites untouched (entries 4 h–4 n). To our delight, the alkylation of aromatic Csp2–Br bonds over competing Csp3–halogen sites was also effective (entries 4 f and 4 g). For some substrates (e.g. more sterically hindered examples or those bearing highly reactive functional groups), a slower addition (over a 3–5 min interval) of the organometallic coupling partner proved advantageous to achieve higher yields, regardless of whether the reaction was performed in the presence or absence of air.

Scheme 1.

Demonstration of site‐selective alkylation of C−Br bonds. Reaction conditions: 2 (0.4 mmol), 3 (0.8 mmol in THF, prepared from 0.8 mmol of R‐MgX and 0.84 mmol of ZnCl2), 1 (0.01 mmol), toluene (1.5 mL), open flask, RT, 5 min. [a] Using R‐MgX as 3. [b] 3 was added drop‐wise.16 [c] 0.6 mmol of 3. [d] 0.72 mmol of 3. [e] 1.2 mmol of 3. [f] 1.0 mmol of 3.

With these excellent selectivities proven, we subsequently tested this methodology for its potential in large‐scale applications. Addition of n‐butylzinc chloride to 1 g of 2‐bromo‐4‐chlorophenyl triflate (2 a), along with 1 mol % of the PdI catalyst 1 under otherwise identical open‐flask reaction conditions, yielded the C−Br coupling product (4 a) in 91 % yield in 5 min. Thus, these coupling reactions are also equally selective and rapid under reduced catalyst loadings and significantly larger scales. As such, our methodology allows for fully predictable, robust and substrate‐independent C−Br alkylation under highly practical conditions.

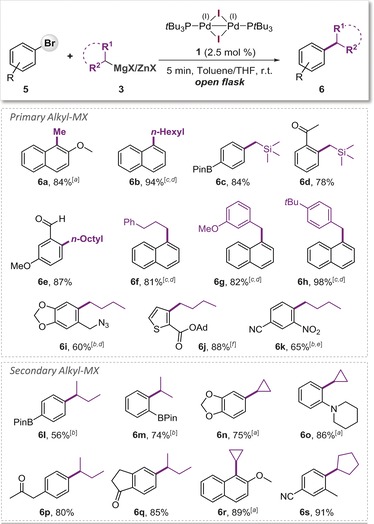

Having demonstrated the exclusive bromo‐selectivity in competition with C−OTf and C−Cl sites, we next investigated the general synthetic applicability of this methodology for less activated arenes containing only a single coupling site along with additional functional groups (Scheme 2). Heterocycles as well as electrophilic functional groups (i.e. aldehyde 6 e, nitriles 6 k and 6 s, ketones 6 d, 6 p, 6 q, ester 6 j) are well tolerated. The reaction could also be performed in the presence of nitro (6 k), azido (6 i) functionalities.17 Also boronic acid esters (i.e. BPin, 6 c, 6 l, and 6 m), which can enable further orthogonal coupling reactions and hence molecular diversity.

Scheme 2.

Scope of C−Br alkylation and functional group tolerance. Reaction conditions: 2 (0.4 mmol), R‐ZnX 3 (0.8 mmol in THF, prepared from 0.8 mmol of R‐MgX and 0.84 mmol of ZnCl2), 1 (0.01 mmol), toluene (1.5 mL), open flask, RT, 5 min.18 [a] Using R‐MgX as 3. [b] 3 was added drop‐wise. [c] Alkyl‐ZnX was prepared from Alkyl‐X using Mg, LiCl and ZnCl2. See Supporting Information for details. [d] 0.6 mmol of 3. [e] 0.72 mmol of 3. [f] 1.2 mmol of 3.

In terms of the scope of organometallic reagents a variety of alkylzinc, as well as some alkylmagnesium coupling partners could be utilized. Alkyl groups, both with and without β‐hydrogen atoms, all proved compatible and underwent smooth Csp2–Csp3 couplings (Scheme 2). Methylation (6 a) proceeded most efficiently under Kumada conditions. A range of secondary alkyl zinc and magnesium reagents could also be coupled efficiently. The desired products were obtained in good yields for both acyclic (i‐Pr, sec‐butyl) as well as cyclic (cyclopropyl, ‐pentyl, and ‐hexyl) alkyl groups. Products arising from isomerization of the secondary alkyl moiety were detected either in trace amounts (≤3 % with 6 m) or not at all (6 l, 6 p, q), and as such are competitive with the current state‐of‐the‐art.4a–4f

To shed light on the potential mechanism of the transformation and the origins of exclusive bromo‐selectivity, we conducted computational studies and examined the predicted site‐selectivity for C−Br versus C−Cl versus C−OTf as a function of active species.19 The dinuclear PdI dimers may either react directly with aryl halides or act as a precursor for monophosphine Pd0. In short, the precise mode of reactivity is highly dependent on whether the coupling partner can function as a bridging unit in the dinuclear entity.13, 20 For related dinuclear NiI complexes, there has been very recent evidence that carbon‐based bridges may in fact be possible.21 We calculated the predicted selectivities for an n‐propyl‐bridged PdI dimer, which indicated a clear C−Br addition preference. Both C−Cl and C−OTf are predicted to be significantly disfavored (by ΔΔG ≠=5.8 and 2.8 kcal mol−1). Alternatively, Pd0PtBu3 may be active and our computations suggest preferential C−Br addition (by ΔΔG ≠=4.4 and 8.3 kcal mol−1 for Cl and OTf). Overall, these data suggest that both Pd0‐based and PdI−PdI‐based reactivities are consistent with the observed C−Br selectivity. The NHC and CPhos systems (as presented in Figure 2) are also generally presumed to form mono‐ligated active Pd0 species.11 We also calculated the predicted selectivities for these cases. Interestingly, these Pd0L1 species also show a clear preference for oxidative addition at C−Br (by ΔΔG ≠=5.6 and 7.8 kcal mol−1, respectively, for C−Cl and C−OTf with L=IPent, and 3.0 and 9.5 kcal mol−1 with L=CPhos). These data contrast the observed lack of selectivities and point toward more complex reactivity scenarios. For example, there could be alternative reactive species, or oxidative addition may not be the selectivity‐determining step for these systems. Overall, however, on the basis of the collected data neither Pd0 nor PdI−PdI catalysis can be excluded in our case. Our future studies are directed at gaining detailed mechanistic insight on these and related processes.

In conclusion, a predictable, chemoselective alkylation of C−Br sites in the presence of C−OTf, C−Cl, and additional functional groups was developed. The method is characterized by high speed (≤5 min reaction time) and operational simplicity, being fully compatible with oxygen (open‐flask conditions) and employing an air‐, moisture, and thermally stable dinuclear PdI catalyst. Primary and secondary alkyl groups were introduced for a wide range of substrates, tolerating steric bulk and numerous functional groups, including cyano, aldehyde, azide, nitro, ester, methoxy, BPin, and silyl groups, as well as benzylic chlorides, alkyl bromides, and heterocycles. Potential for large‐scale applications was also showcased.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

We thank the RWTH Aachen, the MIWF NRW, the European Research Council (ERC‐637993) and Evonik (doctoral scholarship to T.S.) for funding. Calculations were performed with computing resources granted by JARA‐HPC from RWTH Aachen University under project “jara0091”.

I. Kalvet, T. Sperger, T. Scattolin, G. Magnin, F. Schoenebeck, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 7078.

Contributor Information

M. Sc. Indrek Kalvet, http://www.schoenebeck.oc.rwth‐aachen.de/.

Prof. Dr. Franziska Schoenebeck, Email: franziska.schoenebeck@rwth-aachen.de.

References

- 1.For Reviews on various methods for Csp2–Csp3 bond formation see:

- 1a.Z. Dong, Z. Ren, S. J. Thompson, Y. Xu, G. Dong, Chem. Rev 2017, 117, DOI: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00574; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 1b. He J., Wasa M., Chan K. S. L., Shao Q., Yu J.-Q., Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 0; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1c. Rueping M., Nachtsheim B. J., Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2010, 6, 6; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1d. Huryn D. M. in Comprehensive Organic Synthesis (Ed.: I. Fleming), Pergamon, Oxford, 1991, p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. Jana R., Pathak T. P., Sigman M. S., Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 1417; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Tasker S. Z., Standley E. A., Jamison T. F., Nature 2014, 509, 299; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2c. Ackermann L., J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 8948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.

- 3a. Colacot T. J., New Trends in Cross-Coupling: Theory and Applications, RSC Catalysis Series, Cambridge, 2015; [Google Scholar]

- 3b. Johansson Seechurn C. C. C., Kitching M. O., Colacot T. J., Snieckus V., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 5062; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 5150; [Google Scholar]

- 3c. Diederich F., de Meijere A., Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions , 2nd ed., Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2004; [Google Scholar]

- 3d. Negishi E.-i., de Meijere A., Handbook of Organopalladium Chemistry for Organic Synthesis, Wiley, New York, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.

- 4a. Atwater B., Chandrasoma N., Mitchell D., Rodriguez M. J., Organ M. G., Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 14531; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4b. Atwater B., Chandrasoma N., Mitchell D., Rodriguez M. J., Pompeo M., Froese R. D. J., Organ M. G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 9502; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 9638; [Google Scholar]

- 4c. Yang Y., Niedermann K., Han C., Buchwald S. L., Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 4638; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4d. Giannerini M., Fañanás-Mastral M., Feringa B. L., Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 667; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4e. Pompeo M., Froese R. D. J., Hadei N., Organ M. G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 11354; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 11516; [Google Scholar]

- 4f. Han C., Buchwald S. L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 7532; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4g.β-H elimination could also be used to selectively prepare linear products from branched organozinc reagents: Dupuy S., Zhang K.-F., Goutierre A.-S., Baudoin O., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 14793; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 15013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.

- 5a. Klatt T., Markiewicz J. T., Sämann C., Knochel P., J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 4253; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5b. Blümke T. D., Piller F. M., Knochel P., Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 4082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.There are a few isolated reports on Br vs. Cl selectivity for specific substrates. With Suzuki couplings, Br- vs. OTf-selective alkylation was achieved for two substrates:

- 6a. Li C., Chen T., Li B., Xiao G., Tang W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 3792; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 3863; [Google Scholar]

- 6b. Ohe T., Miyaura N., Suzuki A., J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 2201. Alkylation of C−Br has otherwise not been achieved in the presence of C−OTf sites. [Google Scholar]

- 7.

- 7a. Almond-Thynne J., Blakemore D. C., Pryde D. C., Spivey A. C., Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 40; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7b. Proutiere F., Lyngvi E., Aufiero M., Sanhueza I. A., Schoenebeck F., Organometallics 2014, 33, 6879; [Google Scholar]

- 7c. Proutiere F., Aufiero M., Schoenebeck F., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 606; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7d. Hassan Z., Hussain M., Villinger A., Langer P., Tetrahedron 2012, 68, 6305; [Google Scholar]

- 7e. Proutiere F., Schoenebeck F., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 8192; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2011, 123, 8342; [Google Scholar]

- 7f. Schoenebeck F., Houk K. N., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 2496; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7g. Espino G., Kurbangalieva A., Brown J. M., Chem. Commun. 2007, 1742; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7h. Fairlamb I. J. S., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 1036; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7i. Schröter S., Stock C., Bach T., Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 2245; [Google Scholar]

- 7j. Littke A. F., Dai C., Fu G. C., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 4020; [Google Scholar]

- 7k. Kamikawa T., Hayashi T., Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 7087. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kalvet I., Magnin G., Schoenebeck F., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 1581; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 1603. [Google Scholar]

- 9.For examples of iterative couplings, see:

- 9a. Crudden C. M., Ziebenhaus C., Rygus J. P. G., Ghozati K., Unsworth P. J., Nambo M., Voth S., Hutchinson M., Laberge V. S., Maekawa Y., Imao D., Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11065; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9b. Li J., Ballmer S. G., Gillis E. P., Fujii S., Schmidt M. J., Palazzolo A. M. E., Lehmann J. W., Morehouse G. F., Burke M. D., Science 2015, 347, 1221; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9c. Board J., Cosman J. L., Rantanen T., Singh S. P., Snieckus V., Platinum Met. Rev. 2013, 57, 234. [Google Scholar]

- 10.The other components are mainly the starting material or its debromination product. With Pd-PEPPSI-IPent also 6 % tri-alkylated product was observed.

- 11.

- 11a. Valente C., Çalimsiz S., Hoi K. H., Mallik D., Sayah M., Organ M. G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 3314; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 3370; [Google Scholar]

- 11b. Barder T. E., Walker S. D., Martinelli J. R., Buchwald S. L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 4685; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11c. Christmann U., Vilar R., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 366; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2005, 117, 370. [Google Scholar]

- 12.

- 12a. Kolter M., Koszinowski K., Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 15744; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12b. Roy A. H., Hartwig J. F., Organometallics 2004, 23, 194; [Google Scholar]

- 12c. Jutand A., Mosleh A., Organometallics 1995, 14, 1810. [Google Scholar]

- 13.

- 13a. Sperger T., Sanhueza I. A., Schoenebeck F., Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 1311; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13b. Yin G., Kalvet I., Schoenebeck F., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 6809; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 6913; [Google Scholar]

- 13c. Aufiero M., Scattolin T., Proutière F., Schoenebeck F., Organometallics 2015, 34, 5191; [Google Scholar]

- 13d. Aufiero M., Sperger T., Tsang A. S. K., Schoenebeck F., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 10322; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 10462; [Google Scholar]

- 13e. Kalvet I., Bonney K. J., Schoenebeck F., J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 12041; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13f. Bonney K. J., Proutiere F., Schoenebeck F., Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 4434. [Google Scholar]

- 14.We also tested butylmagnesium and -lithium reagents, which were less efficient. See Supporting Information for further information.

- 15. Safety note: organometallic reagents are often moisture sensitive and may react violently in air. All necessary safety precautions must be considered when operating under open-flask conditions.

- 16.Preparation of 4 q required slow addition over 10 min.

- 17.To date, there have been few reports of Negishi alkylation using halonitroarenes. There have been no reports on alkyl halide and azide functionalities. For Ni-catalyzed Kumada cross-coupling in the presence of an alkyl bromide see: Lohre C., Droege T., Wang C., Glorius F., Chem. Eur. J. 2011, 17, 6052.21509842 [Google Scholar]

- 18.The organometallic reagents were obtained from commercial sources, or prepared by the procedure from Ref. [5b] or by pre-mixing the Grignard with ZnCl2 solution.

- 19.

- 19a.Gaussian 09, Revision E.01, M. J. Frisch, et al. [see Supporting Information for full reference].

- 19b.Calculations were performed at the CPCM (toluene) M06L/def2TZVP//ωB97XD/6-31G(d) (LANL2DZ) level of theory.

- 19c.For appropriateness of method, see: Sperger T., Sanhueza I. A., Kalvet I., Schoenebeck F., Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 9532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Labile PdI dimers have otherwise found applications as precatalysts:

- 20a. Melvin P. R., Nova A., Balcells D., Dai W., Hazari N., Hruszkewycz D. P., Shah H. P., Tudge M. T., ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 3680; [Google Scholar]

- 20b. Colacot T. J., Platinum Met. Rev. 2009, 53, 183; [Google Scholar]

- 20c. Christmann U., Pantazis D. A., Benet-Buchholz J., McGrady J. E., Maseras F., Vilar R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 6376; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20d. Stambuli J. P., Kuwano R., Hartwig J. F., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 4746; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2002, 114, 4940. [Google Scholar]

- 21.For precedence of C-bridged NiI-dimer species, see: Matsubara K., Yamamoto H., Miyazaki S., Inatomi T., Nonaka K., Koga Y., Yamada Y., Veiros L. F., Kirchner K., Organometallics 2017, 36, 255. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary