Abstract

The mechanisms involved in the fast growth of Angiostrongylus cantonensis from fifth-stage larvae (L5) to female adults and how L5 breaks through the blood-brain barrier in a permissive host remain unclear. In this work, we compared the transcriptomes of these two life stages to identify the main factors involved in the rapid growth and transition to adulthood. RNA samples from the two stages were sequenced and assembled de novo. Gene Ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway analyses of 1,346 differentially expressed genes between L5 and female adults was then undertaken. Based on a combination of analytical results and developmental characteristics, we suggest that A. cantonensis synthesizes a large amount of cuticle in L5 to allow body dilatation in the rapid growth period. Products that are degraded via the lysosomal pathway may provide sufficient raw materials for cuticle production. In addition, metallopeptidases may play a key role in parasite penetration of the blood-brain barrier during migration from the brain. Overall, these results indicate that the profiles of each transcriptome are tailored to the need for survival in each developmental stage.

Keywords: comparative transcriptomes, cuticle synthesis, lysine degradation, lysosomal pathway, metallopeptidases

Introduction

Angiostrongylus cantonensis, a parasitic nematode (roundworm) that causes angiostrongyliasis, has been detected in lemurs, opossums, tamarins, falcons and non-human primates, and may endanger many wildlife species in areas where the infection is uncontrolled (Martins et al., 2015; Spratt, 2015). In addition, since the first clinical diagnosis reported in Taiwan in 1945, the disease has been increasingly observed worldwide, including in previously non-epidemic countries such as France, Germany, the Caribbean region (including Jamaica), Brazil, Ecuador and South Africa (Morassutti et al., 2013; Barratt et al., 2016). Angiostrongyliasis has been considered as an emerging global public health problem mainly because of the increase of international traffic facility which make it endemic previously in many unaffected areas (Graeff-Teixeira, 2007).

Angiostrongylus cantonensis has a complicated life cycle. The first-stage larvae (L1) develop to third-stage larvae (L3) in about two weeks in intermediate hosts such as snails and slugs. When intermediate hosts with L3 are swallowed by permissive hosts, which are usually rats, the parasites finally develop to adults and live in the hosts pulmonary arteries and heart (Long et al., 2015). However, if positive snails are eaten by non-permissive hosts such as humans and mice, the course of infection usually terminates at L5 in the host brain. When the parasites develop from L5 to adult in permissive hosts, the most notable physical change during this period is expansion of the magniloquent body size and this is generally considered to be the parasites most vigorous period of growth (Hu et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2015). Accordingly, energy and material metabolism are greater during this period than in any other life stages. At the same, there is more intense parasite-host interaction that is mediated by greater release of parasite excretion/secretion protein (ESP) and greater uptake of material from the host.

To reach its final parasitic sites, L5 needs to break through the blood-brain barrier when moving out of the brain (Chiu and Lai, 2014). Proteolytic enzymes are assumed to be involved in blood-brain barrier disruption. A comprehensive understanding of the special developmental processes requires a comparison of the L5 and adult life stages to identify key factors related to rapid growth, parasite-host interaction and transmigration. In this regard, next generation sequencing (NGS), an increasingly popular and effective technology for genome-wide analysis of transcript sequences (t’ Hoen et al., 2013), has been successfully applied to transcriptomic profiling and characterization in the Strongylida and many other parasitic helminths (Chilton et al., 2006).

In this study, the transcriptomes of L5 and female adults of A. cantonenesis were sequenced by NGS and assembled de novo with Trinity. Subsequently, genes that were differentially expressed between these two life-stages were identified by comparative transcriptomic analysis. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was used to validate the transcriptomic data. The findings described here provide a general picture of the gene expression profiles of A. cantonensis that may shed light on the development of this parasite and its survival in the host.

Material and Methods

Animals

Female Sprague Dawley (SD) rats (6-8 week-old, 120-150 g) and Pomacea canaliculata (channeled applesnail) were used to maintain the parasites and allow completion of the whole life cycle. The rats were housed with free access to water and food in the Xiamen University Laboratory Animal Center. This study was done in strict accordance with the Regulations for the Administration of Affairs Concerning Experimental Animals (as approved by the State Council of the People's Republic of China). Moreover, the protocols involving rats were approved by the Committee for the Care and Ethics of Xiamen University Laboratory Animals (permit no. XMULAC2012-0122). L5 were obtained from the brains of rats infected with 200 L3 15 days previously. Female adult worms were collected as previously described (Zhang et al., 2014). The worms were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4) and then stored a −80 °C after soaking in RNAhold reagent (Transgene Biotech, Beijing, China) until RNA extraction.

RNA extraction, cDNA library preparation and RNA sequencing

Total RNA from each life stage was extracted with TransZol Up (Transgene Biotech) according to the manufacturer's protocols. The RNA concentration was measured using a Qubit® RNA assay kit in a Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Two sequencing libraries were generated and 125 bp pair end-sequencing was done on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform by Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China).

Data quality control and transcriptome assembly

Raw data (raw reads) in fastq format were first processed through in-house perl scripts to obtain clean data (clean reads) by discarding reads containing adapters, reads containing ploy-N and low quality reads. Parent transcriptome (P transcriptome) assembly was done based on clean data from two samples using Trinity software (v.2.0.6), with all parameters set as default (Grabherr et al., 2011). Before annotation, unigenes were picked from the P transcriptome with CD-hit (Li and Godzik, 2006). Intactness of the assembled P transcriptome was assessed with the software tool BUSCO (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs) that is based on evolutionarily informed expectations of gene content, with default settings (Simão et al., 2015). The unigenes were then annotated with BLASTx (BLAST + v.2.2.25) by querying these to the following databases: NCBI non-redundant protein sequences (Nr), NCBI non-redundant nucleotide sequences (Nt), the Protein Family database (Pfam), Swiss-Prot, Gene Ontology (GO), the Eukaryotic Orthologous Groups database (KOG) and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG). The E-value cutoff was set as 1 × 10−5.

Gene expression quantification and differentially expressed genes (DEGs) screening

The transcriptomes of L5 and female adults were assembled with the clean data and the P transcriptome was set as the reference. Gene expression levels were estimated by RSEM (v.1.2.15) for each sample, as described (Li and Dewey, 2011). First, the read count for each gene was obtained from the result of clean data mapped back onto the assembled P transcriptome. Subsequently, the read count of each sequenced library was adjusted with the edger program package to ‘reads per kilobase per million mapped’ (RPKM). The differential expression analysis of two samples was done using the DEGseq R package (v.1.12.0) (Wang et al., 2010). The P-value was adjusted by the q-value; a q-value < 0.005 and |log2 (fold change)| > 1 were set as the threshold criteria for significant differential expression.

GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs

For functional annotation, GO enrichment analysis of DEGs was implemented using the GOseq R packages (v1.10.0) based on a Wallenius non-central hyper-geometric distribution (Young et al., 2010). KEGG pathway analysis of DEGs was then done through the KEGG database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/) (Mao et al., 2005; Kanehisa et al., 2008).

cDNA synthesis and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

One microgram of RNA from each stage was converted to first strand cDNA using a First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Fifteen DEGs were significantly enriched in the lysosomal pathway and were randomly chosen for validation by qPCR. β-Actin was selected as an internal control based on previous studies (Zhang et al., 2014; Long et al., 2016). Primers were designed using Primer 3.0 and the sequences are listed in the supplementary materials (Table S1 (123.5KB, pdf) ). Three biological replicates were used for the qPCRs of each gene. The reaction mixture (10 μL) consisted of 5 μL of SYBR Green PCR master mix, 0.5 μL (10 μM) of the forward and reverse primers, 1 μL of cDNA (diluted 10 times with double distilled water – ddH2O) from each developmental stage and 3 μL of ddH2O. The cycling conditions involved an initial activation step at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s, 60 °C for 30 s and fluorescence acquisition at 60 °C for 30 s using a CFX96 Real Time system (BioRad, USA).

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis of the qPCR data was done with SPSS18.0 (SPSS statistical package for Windows®) and Students t-test was used to detect significant differences. A p-value < 0.05 indicated significance.

Results

Summary of the raw sequence reads and assembly

To obtain a global overview of the A. cantonensis transcriptome, clean data from each life stage were combined to provide a relatively comprehensive gene pool. Overall, 12.66 Gb of clean data (~50-fold coverage of the whole genome) were used for de novo transcriptome assembly. Raw reads of the transcriptome have been deposited in the NCBI Short Read Archive (SRA, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/) under accession numbers SRR3199277 and SRR3199278. Table 1 summarizes the sequence reads and P transcriptome. BUSCO analysis revealed that the P transcriptome was largely complete as we recovered 531 complete single-copy BUSCOs (68.1%) and an additional 71 fragmented BUSCOs (8.4%). Only 5.1% of the BUSCOs were found to be duplicated in the combined transcriptome, indicating that the transcriptome assembly was successful.

Table 1. Summary of the sequence reads and P transcriptome.

| Summary of sequence reads | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sample | F | L5 |

| Raw reads | 55,725,337 | 50,234,050 |

| Clean reads | 51,957,988 | 49,275,894 |

| Clean reads (%) | 93.24 | 98.09 |

| Clean bases (Gb) | 6.5 | 6.16 |

| Q20 of clean reads (%) | 96.09 | 96.89 |

| Total clean bases (Gb) | 12.66 | |

| Characteristics of the P transcriptome | ||

| Levels | Transcripts | Unigenes |

| Total nucleotides | 99,597,159 | 51,401,554 |

| Numbers (length > 200 bp) (n) | 115,369 | 82,769 |

| Average length (bp) | 863 | 621 |

| N50 | 1,731 | 949 |

| Shortest transcript (bp) | 201 | |

| Longest transcript (bp) | 20,809 | |

Annotation of the P transcriptome

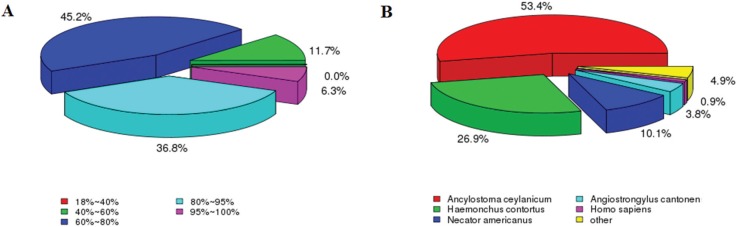

Most (98.69%) of the P transcriptome unigenes were successfully annotated in less than one of the seven public databases indicated above. The homology and species-based distribution for all of proteins were analyzed against the Nr database and 82% of the sequences showed similarity > 60% with their blast result. Ancylostoma ceylanicum, Haemonchus contortus and Necator americanus showed the greatest similarity in the species-based distribution (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Summary of the results of sequence-homology searches against the Nr database. (A) Similarity distribution of the closest BLASTX matches for each sequence. (B) A species-based distribution of BLASTX matches for sequences.

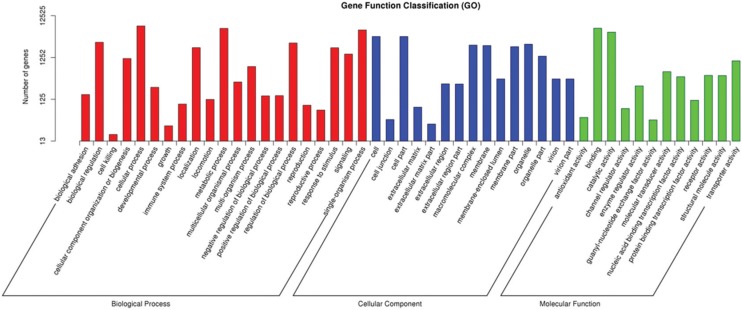

GO analysis assigned 12,525 unigenes to the corresponding GO terms, the details of which are shown in Figure 2. Most of the biological process (BP) categories were related to cellular processes (GO: 0009987, 56.73%), metabolic processes (GO: 0008152, 49.64%) and single-organism processes (GO: 0044699, 45.54%), while most unigenes were sorted into the cell part (GO: 0044464, 31.67%), cell (GO: 0005623, 31.67%) and organelle (GO: 0043226, 20.77%) in the cell component (CC) category. Binding (GO: 0005488, 50.05%) and catalytic activity (GO: 0003824, 40.3%) were the main GO terms of the molecular function (MF) category.

Figure 2. Gene ontology classifications of unigenes from the P transcriptome.

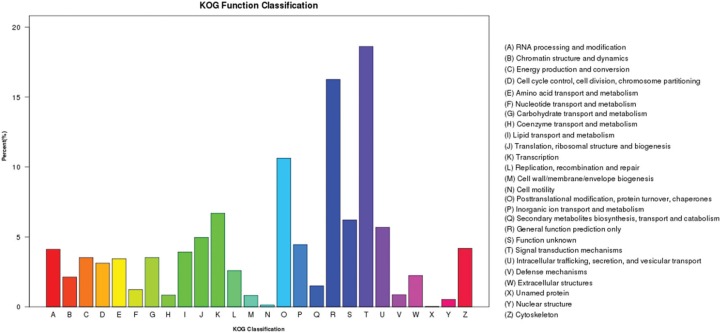

Blasting to the KOG database for functional prediction and classification assigned 6,251 unigenes to 26 specific pathways (Figure 3). ‘Signal transduction mechanisms’ (1,163) was the largest group, followed by ‘General function prediction only’ (1,016), ‘Post-translational modification, protein turnover, chaperones’ (664), and ‘Transcription’ (418).

Figure 3. KOG classifications of unigenes from the P transcriptome.

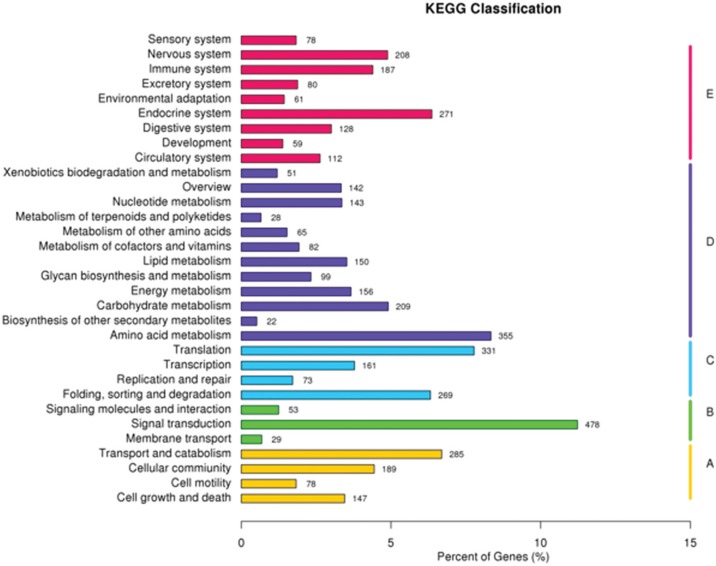

A total of 4,257 unigenes were functionally assigned to the 259 KEGG pathways of five KEGG categories by KEGG pathway analysis. Lysine degradation (ko00310), purine metabolism (ko00230) and ribosome (ko03010) were the top three pathways sorted by the unigenes numbers involved (Table S2 (212.9KB, pdf) ). The distribution of these unigenes in 32 KEGG sub-categories is shown in Figure 4. Endocrine system, amino acid metabolism, translation, signal transduction, transport and catabolism were the highest enriched subcategories of each category.

Figure 4. KEGG classifications of unigenes from the P transcriptome. (A) Cellular processes, (B) Environmental information processing, (C) Genetic information processing, (D) Metabolism and (E) Organismal systems.

Gene expression quantification and related analyses

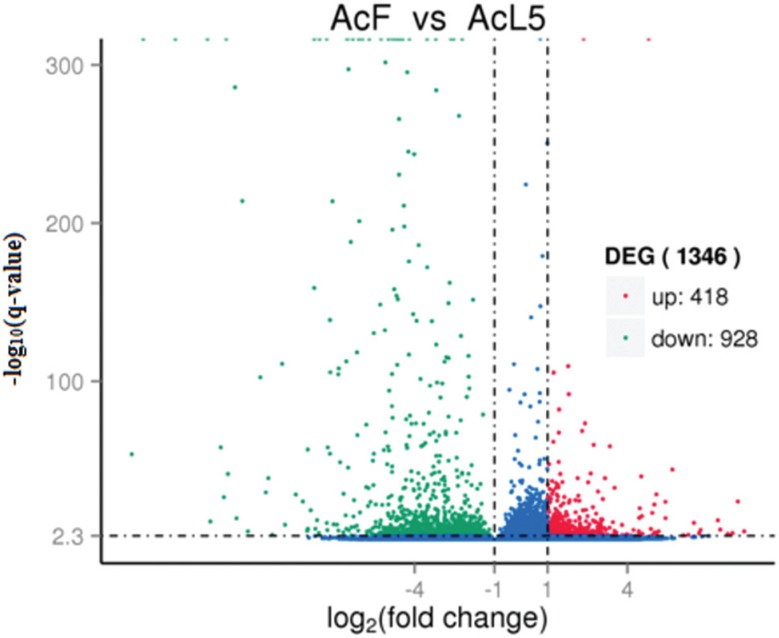

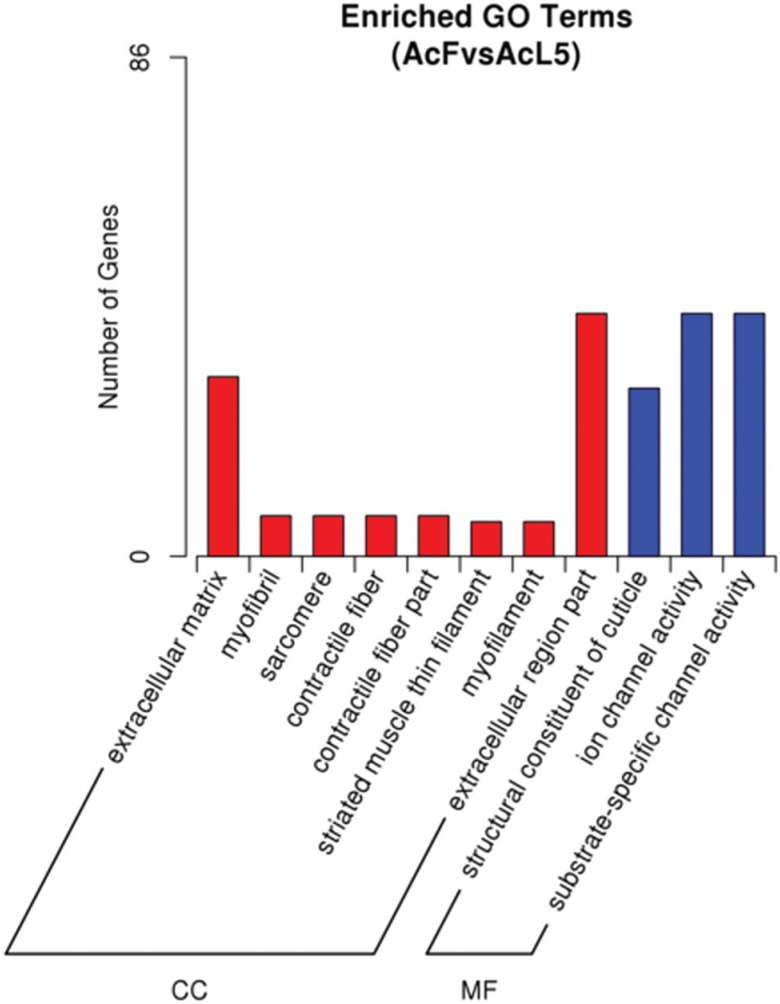

Gene expression quantification was done as described in the Methods section. The mapping rate for L5 and female adults was 87.15 and 82.94, respectively. The percentages of both samples were > 80%, suggesting that the transcriptome was well-assembled. Of the 1,346 DEGs analyzed (L5 vs female adults), 418 were up-regulated and 928 down-regulated (Figure 5). c6135_g1 was the highest up-regulated gene with a log2 fold-change of 8.15; annotation information suggested that this gene was involved in nematode cuticle collagen synthesis. GO enrichment analysis of 1,346 DEGs showed that the extracellular region part (GO: 0044421), ion channel activity (GO: 0005216) and substrate-specific channel activity (GO: 0022838) were the top three of the 11 significantly enriched terms (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Volcano plots of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in L5 and female adults. AcF – A. cantonensis female, AcL5 – young adults of A. cantonensis. Unigenes that satisfied these conditions (log2-fold-change > 1 and q value < 0.005) were considered to be differentially expressed. Blue, red and green splashes represent genes with no significant change in expression, significantly up-regulated genes and significantly down-regulated genes, respectively.

Figure 6. GO enrichment analysis results for down-regulated DEGs. CC – cellular component and MF – molecular function.

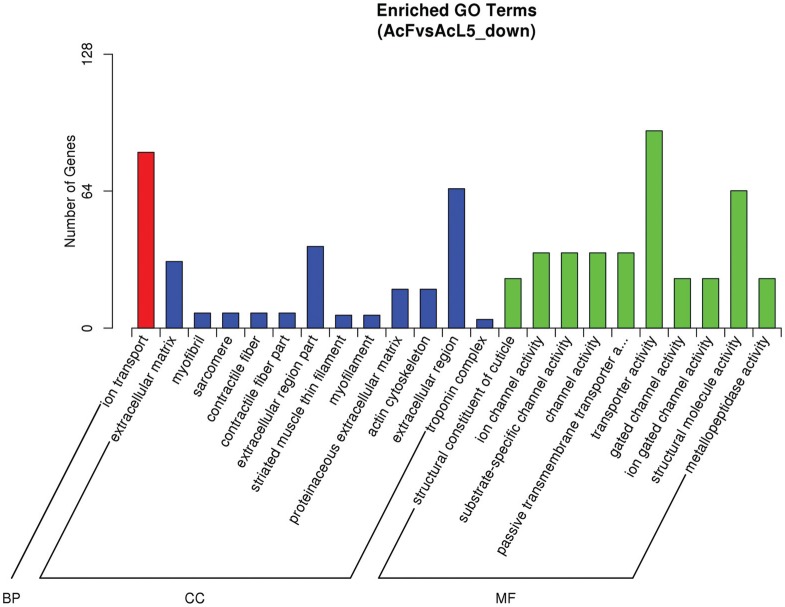

Nine hundred and twenty-eight down-regulated unigenes were analyzed in the same way and revealed 23 significantly enriched GO terms (Figure 7). Transporter activity and structural molecule activity were the dominant enriched terms of the MF category. Ion transport was the sole term in the BP category, which had 82 unigenes. In the CC category, the extracellular region, extracellular region part and extracellular matrix were the most highly enriched.

Figure 7. GO enrichment analysis results for down-regulated DEGs. BP – biological process, CC – cellular component and MF – molecular function.

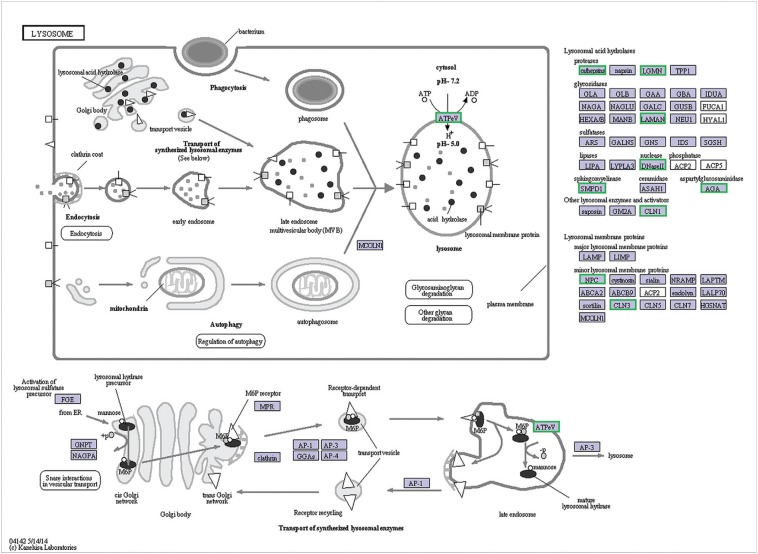

DEGs were further subjected to the KEGG database for pathway enrichment analysis. Lysosome was the only highly enriched KEGG pathway (Figure 8). Lysosomes are membrane-delimited organelles that serve as the cell's main digestive compartment where various macromolecules are delivered for degradation and recycling. Lysosomes contain > 60 hydrolases involved in this degradation in an acidic environment (~pH 5). Seven of these (legumain [LGMN], cathepsins, N4-[β-N-acetylglucosaminyl]-L-asparaginase [AGA], palmitoyl-protein thioesterase, deoxyribonuclease II [DNase II], lysosomal α-mannosidase [LAMAN] and sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase [SMPD1]) were highly expressed in L5. V-type H+-transporting ATPase (V-ATPase), battenin (encoded by the CLN3 gene) and Niemann-pick type C (NPC) were the other three proteins associated with the lysosomal membrane and were down-regulated in female adults. The perturbation of these proteins usually leads to marked changes in lysosomal function.

Figure 8. Unigenes predicted to be involved in the lysosomal pathway. Green represents down-regulated unigenes in female adults compared to L5.

Validation of DEGs by qPCR

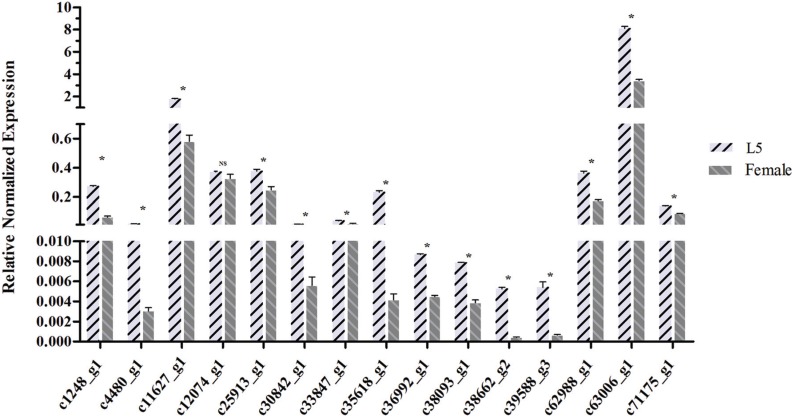

Although biological repeats for the RNA-seq data were not done, qPCR (triplicate replicates) was used to check 15 out of 18 DEGs involved in the lysosomal pathway; 14 of the 15 unigenes revealed consistent expression patterns with the RNA-Seq data (Figure 9).

Figure 9. qPCR validations for 15 DEGs in the lysosomal pathway. An asterisk indicates a significant difference between L5 and female adult expression levels (p < 0.05, Student's t-test). NS – no significant difference. The columns are the mean ± SEM (n = 3 per column).

Discussion

The highest growth rate in A. cantonensis occurs from the L5 to the female adult stage, during which period body size increases sharply. In permissive hosts, L5 migrates from the brain to the pulmonary artery via the blood-brain barrier. However, the key factors in this important biological process remain largely unknown. To increase our understanding of this phenomenon, we compared the P transcriptome assembled with clean data obtained from the transcriptomes of L5 and female adults, two important life stages of A. cantonensis.

Although two genome assemblies have been reported for A. cantonensis (Morassutti et al., 2013; Yong et al., 2015), we did not use them as references for the following reasons. First, the assembly level for the first of these two studies was ‘Conting’ and therefore did not satisfy the requirement for a reference genome. The other study reached the ‘Scaffold’ level, but the Scaffold N50 (43,900) was too small, indicating that the genome was not well assembled. Second, the primary assembly unit did not have any assembled chromosomes or linkage groups so that no effective information could be extracted for downstream analysis. Third, before transcriptome assembly, the clean data for L5 and female adults had been separately mapped onto the genome sequences with Tophat2 (mismatch = 2) and the mapping rates were only 82.5% and 79.4%, respectively (Kim et al., 2013). Fourth, many reports have proven that de novo transcriptome assembly can also provide satisfactory results (Fang et al., 2016; Hasanuzzaman et al., 2016; Santos et al., 2016; Wei et al., 2016).

Although Lian and Wang reported that A. cantonensis had the highest homology to Caenorhabditis spp. (up to 97.87%) (Morassutti et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013), our Nr annotation species-based distribution revealed that A. cantonensis was most similar to Ancylostoma ceylanicum (53.4%), followed by Haemonchus contortus (26.9%) and Necator americanus (10.1%) (Figure 1B). These differences may have been caused by bias in the sequence information of different species stored in public databases. Furthermore, the rapid development of high-throughput sequencing technologies has narrowed the gap between model and non-model species because more information could be retrieved from public databases, even for non-model species such as A. ceylanicum, H. contortus and N. americanus (Abubucker et al., 2008; Schwarz et al., 2013; Tang et al., 2014). On the other hand, since these three species and A. cantonensis are parasitic nematodes, it would be more reasonable for A. cantonensis to have a higher homology with these species than with free-living nematodes.

Lysine, an essential amino acid that animals must obtain from their diet because they cannot synthesize it, is not only an important nutritional requirement for growth, but can also directly or indirectly regulate the immune system (Theis et al., 1969; Williams et al., 1997). Lysine-deficient diets result in greater body length in Ascaridia galli and a higher worm burden in chickens. A deficiency in dietary lysine limits protein synthesis and compromises antibody responses and cell-mediated immunity in chickens (Chen et al., 2003; Li et al., 2007; Das et al., 2010). Consequently, these parasites show greater growth and development in hosts with impaired immune systems. Various unigenes were found to be involved in the lysine degradation pathway (ko00310, 225) in the P transcriptome, indicating active lysine degradation in these life stages. The consumption of a large amount of host lysine or lysine-containing proteins by these parasites could make the host lysine-deficient, thereby indirectly weakening the host immune system. We therefore speculate that lysine insufficiency resulting from lysine degradation may be a neglected strategy of A. cantonensis for escaping immunological detection by the host.

The 23 GO terms and one KEGG pathway were significantly enriched with 928 down-regulated DEGs. Among these, eight of 23 enriched GO terms were related to ion channel transport that is essential for normal cell function (Desai, 2012). When L5 migrate from the brain to the final parasitic site there are significant changes in the physicochemical properties of the external environment of A. cantonensis. The concentrations of Na+ and Mg2+ are higher in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), whereas the concentrations of K+, Ga2+, Cl– and HCO3 – are higher in blood. In addition, the protein and glucose content in CSF is lower than in blood (Pardridge, 2005). Obviously, the parasite must adapt to different habitats by modulating the transmembrane transport of ions and organic solutes. Based on the results of the bioinformatics analysis, the bioprocess associated with ion channels and transporters will presumably be active in this period.

The cuticle or outer surface of all parasitic nematodes has important roles in locomotion (by providing points of attachment for muscle), growth, osmoregulation and parasite-host interactions (Wright, 1987). Cuticles often differ in surface protein expression and composition during the developmental stages in parasitic nematodes. Presumably, the worms adjust to changing developmental needs and environmental conditions, including escape from the hosts immunological system, particularly since cuticles are the target of a variety of host immunological responses that may kill the worms (Davies and Curtis, 2011). The protective collagenous cuticle of these parasites is required for survival and the metalloproteinase astacin is a key enzyme involved in the collagen synthesis pathway. GO analyses of 928 down-regulated DEGs identified many GO terms related to muscles and cuticle formation. Based on this finding, we suggest that A. cantonensis invests considerable effort on cuticle and muscle biosynthesis in L5 to satisfy the rapid body expansion in the transition to female adulthood and to survive in different host tissues.

A further 23 enriched DEGs with metallopeptidase activity also attracted our attention. In addition to being associated with collagen synthesis, the essential role of these proteases in tissue invasion is well-documented. The metallopeptidases of bacteria such as Candida albicans and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are located in the cell wall and can degrade host extracellular matrix, thereby accelerating bacterial invasion (Rodier et al., 1999; Miyoshi and Shinoda, 2000). Similar host penetration functions for related proteases have been detected in many parasitic nematodes, including Ancylostoma caninum, Necatora mericanus and Nippostrongylus brasiliensis (Hotez et al., 1990; Knox, 2011; Kumar and Pritchard, 1992; Williamson et al., 2003). Moreover, the work of Miyoshi indicated that metalloproteases present in the ESP of A. cantonensis infective larvae may suppress the host's immune response and allow parasite migration to the host's central nervous system by degrading human matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP-9) (Adisakwattana et al., 2012). Based on these considerations, we speculate that the increased expression of unigenes related to metallopeptidase in L5 may be an important strategy used by A. cantonensis for cuticle synthesis and blood-brain barrier permeation.

Lysosome was the only pathway that was markedly enriched in the KEGG pathway analysis of the L5 and female adult transcriptomes. Lysosomes contain > 60 acidic lysosomal hydrolases belonging to different protein families. This enzymatic diversity makes it possible for lysosomes to participate in many important cellular processes, including protein secretion, macromolecular degradation, energy metabolism and pathogen defense (Saftig and Klumperman, 2009; Settembre et al., 2012, 2013; Yu et al., 2016). Alterations in the expression of genes coding for lysosomal enzymes will have a marked influence on lysosomal activity. The cuticle is a highly structured, collagenous extracellular matrix secreted by the hypodermis surrounding the worms body (Edgar et al., 1982) and lysosomes may be involved in the metabolism of cuticlar collagen. Lysosomes also degrade and recycle a broad range of macromolecules as an important source of nutrients thereby providing an ingenious method for controlling and equilibrating anabolic and catabolic cellular processes (Luzio et al., 2007). Thus, during the high-speed growth stage, lysosomes must adapt to meet the demand for new material and more energy during cuticle formation.

In this work, we compared the transcriptomes of A. cantonensis L5 and female adults. Our findings help to explain two main events that can impact parasite development and survival during this period. First, to meet the demands of rapid body growth, especially expansion of the body surface, L5 requires a large amount of material to sustain the formation of the stratum corneum and its associated structures. Based on the special role of lysosomes in autophagy and apoptosis, we speculate that these phenomena may play a certain role in altering the old and new cuticular tissues of these parasites. Secondly, metallopeptidases secreted by these parasites may be key molecules in allowing the parasite to break through the blood-brain barrier by degrading the extracellular matrix of host tissues. These findings offer novel insights into parasite development, survival and host-parasite interactions and provide a solid foundation for understanding how these genes participate in these processes.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no competing interests with the publication of this work. This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81171595, 2012) and by the National Parasite Germplasm Sharing Service Platform (grant no. TDRC-2017-22).

Supplementary Material

The following online material is available for this article:

Footnotes

Associate Editor: Ana Tereza Vasconcelos

References

- Adisakwattana P, Nuamtanong S, Yenchitsomanus PT, Komalamisra C, Meesuk L. Degradation of human matrix metalloprotease-9 by secretory metalloproteases of Angiostrongylus cantonensis infective stage. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2012;43:1105–1113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abubucker S, Martin J, Yin Y, Fulton L, Yang S, Hallsworth-Pepin K, Johnston JS, Hawdon J, McCarter JP, Wilson RK, et al. The canine hookworm genome: Analysis and classification of Ancylostoma caninum survey sequences. Mol Biochem Parasit. 2008;157:187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barratt J, Chan D, Sandaradura I, Malik R, Spielman D, Lee R, Marriott D, Harkness J, Ellis J, Stark D. Angiostrongylus cantonensis: A review of its distribution, molecular biology and clinical significance as a human pathogen. Parasitology. 2016;149:1–32. doi: 10.1017/S0031182016000652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Sander JE, Dale NM. The effect of dietary lysine deficiency on the immune response to Newcastle disease vaccination in chickens. Avian Dis. 2003;47:1346–1351. doi: 10.1637/7008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilton NB, Huby-Chilton F, Gasser RB, Beveridge I. The evolutionary origins of nematodes within the order Strongylida are related to predilection sites within hosts. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2006;40:118–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu Ping-Sung, Lai Shih-Chan. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 leads to blood–brain barrier leakage in mice with eosinophilic meningoencephalitis caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis . Acta Trop. 2014;140:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das G, Kaufmann F, Abel H, Gauly M. Effect of extra dietary lysine in Ascaridia galli-infected grower layers. Vet Parasitol. 2010;170:238–243. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies KG, Curtis RHC. Cuticle surface coat of plant-parasitic nematodes. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2011;49:135–156. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-121310-111406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai SA. Ion and nutrient uptake by malaria parasite-infected erythrocytes. Cell Microbiol. 2012;14:1003–1009. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01790.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RS, Cox GN, Kusch M, Politz JC. The cuticle of Caenorhabditis elegans . J Nematol. 1982;14:248–258. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, Mei H, Zhou B, Xiao X, Yang M, Huang Y, Long X, Hu S. De novo transcriptome analysis reveals distinct defense mechanisms by young and mature leaves of Hevea brasiliensis (Pará rubber tree) Sci Rep. 2016;6:33151–33151. doi: 10.1038/srep33151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, Adiconis X, Fan L, Raychowdhury R, Zeng Q. Trinity: Reconstructing a full-length transcriptome without a genome from RNA-seq data. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graeff-Teixeira C. Expansion of Achatina fulica in Brazil and potential increased risk for angiostrongyliasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101:743–744. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasanuzzaman AFM, Robledo D, Gómez-Tato A, Alvarez-Dios JA, Harrison PW, Cao A, Fernández-Boo S, Villalba A, Pardo BG, Martínez P. De novo transcriptome assembly of Perkinsus olseni trophozoite stimulated in vitro with manila clam (Ruditapes philippinarum) plasma. J Invertebr Pathol. 2016;135:22–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotez P, Haggerty J, Hawdon J, Milstone L, Gamble HR, Schad G, Richards F. Metalloproteases of infective Ancylostoma hookworm larvae and their possible functions in tissue invasion and ecdysis. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3883–3892. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.12.3883-3892.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Li J, Lan L, Wu F, Zhang E, Song Z, Huang H, Luo F, Pan C, Tan F. In vitro study of the effects of Angiostrongylus cantonensis larvae extracts on apoptosis and dysfunction in the blood-brain barrier (BBB) PLoS One. 2012;7:e32161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, Araki M, Goto S, Hattori M, Hirakawa M, Itoh M, Katayama T, Kawashima S, Okuda S, Tokimatsu T, et al. KEGG for linking genomes to life and the environment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D480–D484. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL. Tophat2: Accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 2013;14:295–311. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox D. Proteases in blood-feeding nematodes and their potential as vaccine candidates. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;712:155–176. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-8414-2_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Pritchard DI. Secretion of metalloproteases by living infective larvae of Necator americanus . J Parasitol. 1992;78:917–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:323–323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Godzik A. Cd-hit: A fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1658–1659. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Yin Y, Li D, Woo Kim S, Wu G. Amino acids and immune function. Br J Nutr. 2007;98:237–237. doi: 10.1017/S000711450769936X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long Y, Cao B, Yu L, Tukayo M, Feng C, Wang Y, Luo D. Angiostrongylus cantonensis cathepsin B-like protease (Ac-cathB-1) is involved in host gut penetration. Parasite. 2015;22:37–37. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2015037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long Y, Cao B, Wang Y, Luo D. Pepsin is a positive regulator of Ac-cathB-2 involved in the rat gut penetration of Angiostrongylus cantonensis . Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:286–286. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1568-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzio JP, Pryor PR, Bright NA. Lysosomes: Fusion and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:622–632. doi: 10.1038/nrm2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao X, Cai T, Olyarchuk JG, Wei L. Automated genome annotation and pathway identification using the KEGG orthology (KO) as a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3787–3793. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins YC, Tanowitz HB, Kazacos KR. Central nervous system manifestations of Angiostrongylus cantonensis infection. Acta Trop. 2015;141:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi S, Shinoda S. Microbial metalloproteases and pathogenesis. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:91–98. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)00280-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morassutti AL, Perelygin A, De Carvalho MO, Lemos LN, Pinto PM, Frace M, Wilkins PP, Graeff-Teixeira C, Da Silva AJ. High throughput sequencing of the Angiostrongylus cantonensis genome: A parasite spreading worldwide. Parasitology. 2013;140:1304–1309. doi: 10.1017/S0031182013000656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardridge WM. The blood-brain barrier: Bottleneck in brain drug development. NeuroRx. 2005;2:3–14. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodier MH, El MB, Kauffmann-Lacroix C, Daniault G, Jacquemin JL. A Candida albicans metallopeptidase degrades constitutive proteins of extracellular matrix. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;177:205–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saftig P, Klumperman J. Lysosome biogenesis and lysosomal membrane proteins: Trafficking meets function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:23–635. doi: 10.1038/nrm2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos LN, Silva ES, Santos AS, Sá PHD, Ramos RT, Silva A, Cooper PJ, Barreto ML, Loureiro S, Pinheiro CS. De novo assembly and characterization of the Trichuris trichiura adult worm transcriptome using Ion Torrent sequencing. Acta Trop. 2016;159:132–141. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz EM, Korhonen PK, Campbell BE, Young ND, Jex AR, Jabbar A, Hall RS, Mondal A, Howe AC, Pell J, et al. The genome and developmental transcriptome of the strongylid nematode Haemonchus contortus . Genome Biol. 2013;14:R89–R89. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-8-r89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settembre C, Zoncu R, Medina DL, Vetrini F, Erdin S, Erdin S, Huynh T, Ferron M, Karsenty G, Vellard MC, et al. A lysosome-to-nucleus signalling mechanism senses and regulates the lysosome via mTOR and TFEB. EMBO J. 2012;31:1095–1108. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settembre C, Fraldi A, Medina DL, Ballabio A. Signals from the lysosome: A control centre for cellular clearance and energy metabolism. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:283–296. doi: 10.1038/nrm3565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simão AFO, Waterhouse MR, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva VE, Zdobnov ME. Busco: Assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3210–3212. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spratt DM. Species of Angiostrongylus (Nematoda: Metastrongyloidea) in wildlife: A review. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. 2015;4:178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang YT, Gao X, Rosa BA, Abubucker S, Hallsworth-Pepin K, Martin J, Tyagi R, Heizer E, Zhang X, Bhonagiri-Palsikar V, et al. Genome of the human hookworm Necator americanus . Nat Genet. 2014;46:261–269. doi: 10.1038/ng.2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theis GA, Green I, Benacerraf B, Siskind GW. A study of immunologic tolerance in the dinitrophenyl poly-l-lysine immune system. J Immunol. 1969;102:513–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- t’ Hoen PAC, Friedländer MR, Almlöf J, Sammeth M, Pulyakhina I, Anvar SY, Laros JFJ, Buermans HPJ, Karlberg O, Brännvall M, et al. Reproducibility of high-throughput mRNA and small RNA sequencing across laboratories. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:1015–1022. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Feng Z, Wang X, Wang X, Zhang X. DEGseq: An R package for identifying differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:136–138. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Chen K, Chang S, Chung L, Gan RR, Cheng C, Tang P. Transcriptome profiling of the fifth-stage larvae of Angiostrongylus cantonensis by next-generation sequencing. Parasitol Res. 2013;112:3193–3202. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3495-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Jung S, Chen K, Wang T, Li C. Temporal-spatial pathological changes in the brains of permissive and non-permissive hosts experimentally infected with Angiostrongylus cantonensis . Exp Parasitol. 2015;157:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z, Sun Z, Cui B, Zhang Q, Xiong M, Wang X, Zhou D. Transcriptome analysis of colored Calla lily (Zantedeschia rehmannii Engl.) by Illumina sequencing: de novo assembly, annotation and EST-SSR marker development. Peer J. 2016;4:e2378. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson AL, Brindley PJ, Loukas A. Hookworm cathepsin D aspartic proteases: Contributing roles in the host-specific degradation of serum proteins and skin macromolecules. Parasitology. 2003;126:179–185. doi: 10.1017/s0031182002002706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams NH, Stahly TS, Zimmerman DR. Effect of chronic immune system activation on body nitrogen retention, partial efficiency of lysine utilization, and lysine needs of pigs. J Anim Sci. 1997;75:2472–2480. doi: 10.2527/1997.7592472x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright KA. The nematode's cuticle – Its surface and the epidermis: Function, homology, analogy – A current consensus. J Parasitol. 1987;73:1077–1083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong HS, Eamsobhana P, Lim PE, Razali R, Aziz FA, Rosli NSM, Poole-Johnson J, Anwar A. Draft genome of neurotropic nematode parasite angiostrongylus cantonensis, causative agent of human eosinophilic meningitis. Acta Trop. 2015;148:51–51. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young MD, Wakefield MJ, Smyth GK, Oshlack A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: Accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R14–R14. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F, Chen Z, Wang B, Jin Z, Hou Y, Ma S, Liu X. The role of lysosome in cell death regulation. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:1427–1436. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4516-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Yu C, Wang Y, Fang W, Luo D. Enolase of Angiostrongylus cantonensis: More likely a structural component? Parasitol Res. 2014;113:3927–3934. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-4056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.