Abstract

Background:

Although thyroid fine-needle aspiration (FNA) and core needle biopsy (CNB) are commonly utilized modalities in the evaluation of thyroid nodules, metastatic tumors to the thyroid are only rarely encountered. We aspired to determine the incidence and primary origin of metastases to the thyroid at our institution and to examine their clinicopathologic and cytomorphologic features.

Materials and Methods:

A search of our database was undertaken to review all thyroid FNA and/or CNB examined between January 2004 and December 2013.

Results:

During our 10 year study period, 7497 patients underwent 13,182 FNA and/or CNB. Four hundred sixty one (6%) patients were diagnosed with neoplasms. Only five (1.1%) were found to have metastatic tumors to the thyroid involving three females and two males. Two were diagnosed by FNA, one by CNB, and two by both FNA and CNB, with rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE) employed in all cases. The primary malignancies in the five cases were pulmonary and nasopharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas, renal cell carcinoma, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, and olfactory neuroblastoma. The cytomorphologic features of these metastases to the thyroid aided in their distinction from primary thyroid carcinoma. Two of these metastases, a renal cell carcinoma and pancreatic adenocarcinoma, were the first clinical manifestations of cancer.

Conclusion:

Metastases to the thyroid diagnosed by FNA and/or CNB are exceedingly rare in our institution, comprising only 0.04% of total FNA/CNB and only 1.1% of all thyroid neoplasms. We report the first known case of metastatic olfactory neuroblastoma to the thyroid diagnosed by aspiration cytology. In addition, an occult primary may present as a thyroid mass on FNA or CNB as occurred with two of our cases. FNA/CNB proved to be highly effective in the diagnosis of metastases to the thyroid, with ROSE proving valuable in assuring specimen adequacy. Thyroid FNA and CNB demonstrated great utility in the setting of metastatic disease, obviating the need for more invasive procedures.

Keywords: Core needle biopsy, fine-needle aspiration, metastasis, rapid on-site evaluation, thyroid

INTRODUCTION

According to the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, there will be an estimated 64,300 new cases of thyroid cancer in the United States in 2016, with the state of Hawaii having one of the highest incidence rates in the country.[1] Although thyroid fine-needle aspiration (FNA) and core needle biopsy (CNB) are commonly utilized modalities in the evaluation of thyroid nodules, metastatic tumors to the thyroid are only rarely encountered, with a reported incidence ranging from 0.6% to 5.7% in literature.[2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21] In the setting of metastatic disease, it is clearly desirable to confirm the pathologic diagnosis by a less invasive diagnostic modality such as FNA or CNB. Furthermore, rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE) may aid in ensuring specimen adequacy in this situation,[22] with touch imprint cytology employed to evaluate thyroid CNB. In light of this, we aspired to study the incidence and primary origin of metastatic tumors to the thyroid diagnosed at our institution by FNA and CNB and to examine their clinicopathologic and cytomorphologic features. We also sought to determine the efficacy of FNA cytology and CNB with ROSE imprint cytology in the diagnosis of metastatic disease to the thyroid.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A natural language search was undertaken in our CoPath™ (Sunquest Information Systems, Tucson, Arizona, USA) database to analyze all FNA and/or CNB processed at the Queen's Medical Center and Hawaii Pathologists’ Laboratory between January 2004 and December 2013. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to reviewing patient materials and records (RA-2015-004). For each case, the cytology, histology, and clinical information were retrospectively reviewed.

All thyroid FNA were performed by our institution's interventional radiologists under ultrasound guidance utilizing a 25-gauge FNA needle (BD PrecisionGlide™ Needle, Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lake, NJ, USA) with a 10 mL syringe (BD Luer-Lok™ tip, Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lake, NJ, USA). Preparations from the FNA were made by emptying the syringe and needle hub contents onto one slide and smearing it with a complementary slide. Air-dried smears were stained on-site with the Diff-Quik (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) stain, while alcohol-fixed slides were processed later in the laboratory with the Papanicolau (Pap) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) stain. A cytopathologist performed ROSE of all thyroid FNA per the Bethesda criteria and provided immediate feedback to our interventional radiologists. If need be, additional FNA passes or a 20-gauge CNB (Quick-Core® Biopsy Needle, Cook Medical, Inc., Bloomington, IN, USA) was undertaken. For specimens acquired through CNB, tissue was placed on a slide by the radiologist and then moved into a formalin container by cytology personnel. The slide with the imprint of the core material was then stained on-site with the Diff-Quik stain and immediately evaluated.

With sufficient cellularity, a cell block preparation was created from the thyroid FNA specimen. A solution of 95% alcohol was added to the remaining sample, which was recentrifuged for 5 minutes at 2300 revolutions per minute in the Rotina 380 Benchtop Centrifuge (Hettich™, Tuttlingen, Germany). The fixed cell button was retrieved from the apex of the centrifuge tube, wrapped in rice paper, and submitted in a cassette for histologic processing.

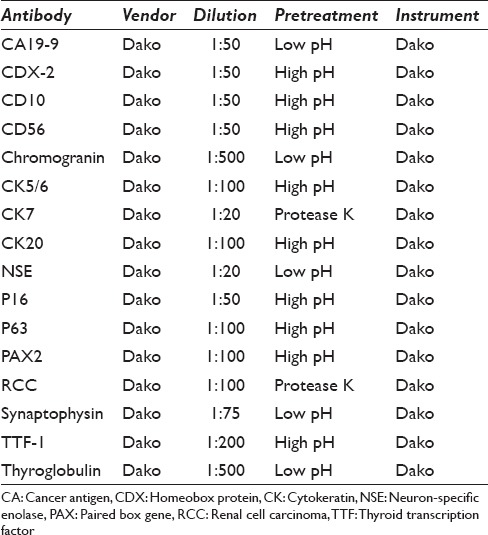

All cases had either a CNB, cell block preparation, or a subsequent surgical resection specimen on which immunoperoxidase studies could be performed. For immunohistochemical staining, 4 μ thick sections were prepared from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded blocks. Staining was conducted with the Dako Immunostainer (Dako Agilent Technologies, Carpinteria, CA, USA) using a heat-induced epitope retrieval protocol [Table 1].

Table 1.

Antibodies used in immunohistochemical staining

RESULTS

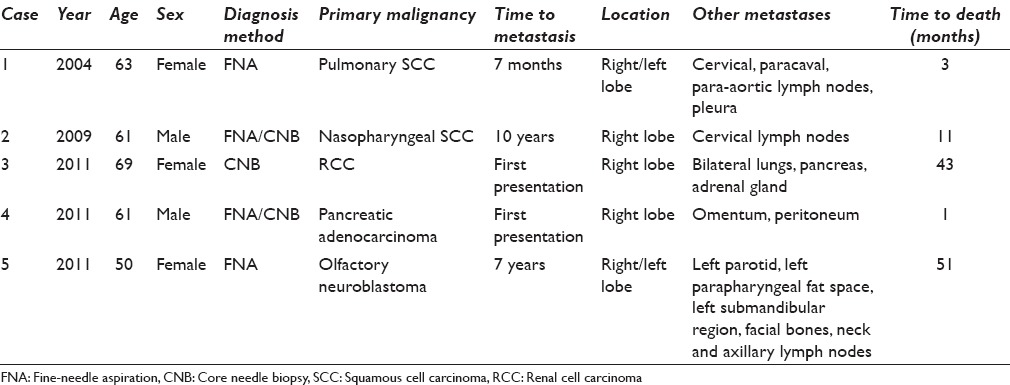

During our 10 year study period, 7497 patients underwent 13,182 FNA and/or CNB. Of these, 461 (6%) patients were diagnosed with neoplasms, including 383 (83%) papillary carcinomas and 49 (11%) follicular tumors. Only five were metastatic tumors to the thyroid [Table 2], comprising only 0.04% of all thyroid cytology/needle biopsy specimens and 1.1% of all thyroid cancers. The diagnosis was rendered utilizing both FNA and CNB in two cases, by FNA alone in two cases, and with only CNB in one case. All five biopsies were performed by radiologists, with ROSE conducted by a cytopathologist in all cases.

Table 2.

Tumors metastatic to the thyroid assessed by fine-needle aspiration/core needle biopsy (2004-2013)

These thyroid metastases presented later in life within a narrow age range (50–69 years) [Table 2], while our primary thyroid cancers demonstrated a much wider age range at presentation (16–93 years). Three patients with metastases were female and two were male. The metastatic lesions varied in size from 1.5 to 4.0 cm. All were located in the right side of the thyroid, with one extending to the isthmus and another involving the contralateral thyroid. Thus, there appeared to be a predilection toward right thyroid lobe involvement. The primary origins of the five cases included pulmonary and nasopharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs), olfactory neuroblastoma, renal cell carcinoma, and pancreatic adenocarcinoma. The renal and pancreatic primaries presented initially as thyroid metastases, while the time of initial cancer diagnosis to thyroid metastasis varied from 6 months to 10 years in the remaining cancers. Other sites of metastases included lymph nodes, lung, pancreas, adrenal, parotid, omentum, mandible, pleura, peritoneum, and bone. Three patients were deceased from disease progression within < 1 year from the time of thyroid metastasis. The patients with renal cell carcinoma and olfactory neuroblastoma expired at 43 and 51 months after thyroid metastasis, respectively.

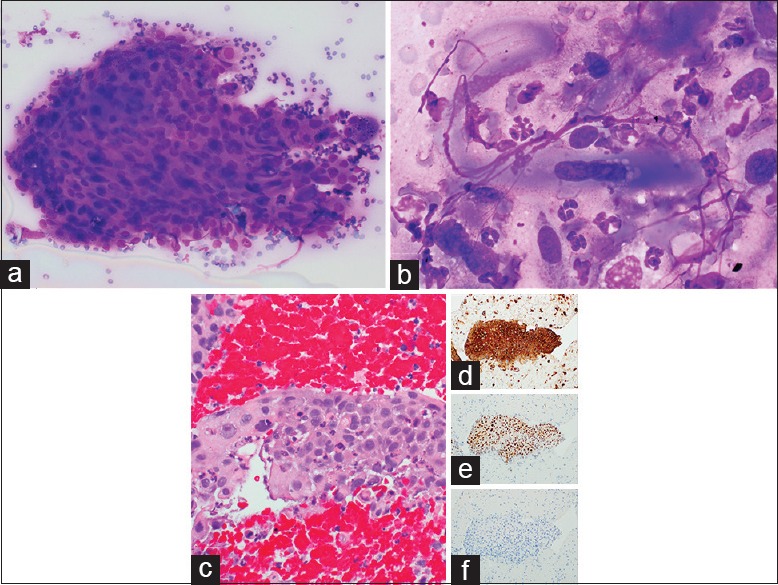

Case 1: Metastatic pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma

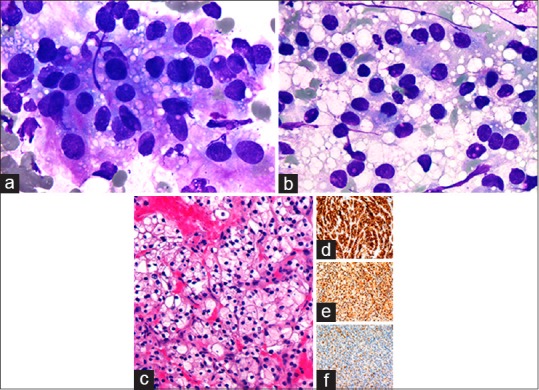

A 63-year-old female was previously diagnosed with inoperable pulmonary SCC 7 months prior and was treated with radiation therapy to slow the progression of tumor growth. She presented to our facility with shortness of breath secondary to a pleural effusion. Physical examination revealed a diffusely enlarged thyroid and cervical lymphadenopathy which was confirmed by an ultrasound and computerized tomographic (CT) scan of the neck. A radiologist performed an ultrasound guided biopsy of a 2.0 cm right thyroid lobe lesion with a fine needle. The ROSE imprint cytology was highly cellular and comprised of irregular disordered clusters of overlapping tumor cells with nuclear pleomorphism and high nuclear-cytoplasmic (N:C) ratios [Figure 1a]. In addition, there were scattered isolated spindled cells with elongated nuclei forming tadpole configurations [Figure 1b]. The nuclei were hyperchromatic and occasionally multinucleated with nuclear membrane irregularities. Nucleoli were indistinct. With Diff-Quik staining, their cytoplasm was dense and glassy blue–purple with distinct cell borders and occasional vacuolization [Figure 1b]. The cell block preparation demonstrated irregular tumor nests with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, prominent intercellular junctions, and scattered dyskeratotic cells [Figure 1c]. Immunohistochemical stains were positive for cytokeratin (CK) 5/6 [Figure 1d] and p63 [Figure 1e] and negative with thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) [Figure 1f] confirming the diagnosis of metastatic SCC. Three months later, the patient succumbed to her disease.

Figure 1.

Metastatic pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma to thyroid. (a) Disordered tumor clusters with overlapping nuclei, nuclear pleomorphism, and high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratios on fine-needle aspiration (×400, Diff-Quik stain). (b) Spindled tumor cells with enlongated hyperchromatic nuclei and dense glassy cytoplasm on fine-needle aspiration (×1000, Diff-Quik stain). (c) Cell block showing metastatic squamous cell carcinoma (×400, H and E) immunopositive for cytokeratin 5/6 (d), p63 (e), and negative for thyroid transcription factor-1 (f) (×200)

Case 2: Metastatic nasopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma

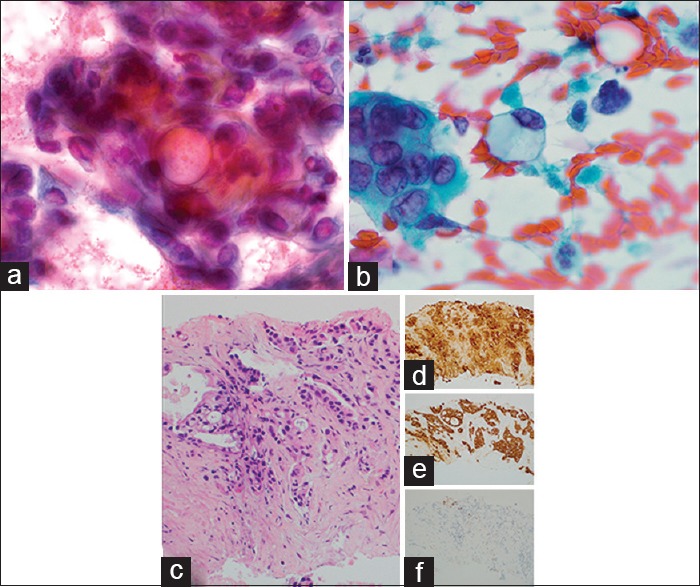

A 61-year-old male with a history of nasopharyngeal SCC diagnosed a decade previously was recently found to have a malignant melanoma on the dorsal tongue surface. On further examination, the patient was also noted to have enlargement of the right thyroid and submandibular gland. FNA and CNB of the right thyroid nodule and submandibular gland were performed. The cytology of the submandibular gland showed metastatic melanoma. The Pap-stained FNA smear of the thyroid revealed frequent elongated spindled forms with dense orangeophilic to green–blue cytoplasm [Figure 2a]. The nuclei varied significantly in size and shape and exhibited hyperchromatism with occasional pyknotic nuclei and indistinct nucleoli. Diff-Quik-stained smears also demonstrated single as well as loose cellular aggregates of tumor, with irregular hyperchromatic nuclei, dense basophilic cytoplasm, and sharply demarcated cell borders [Figure 2b]. Tumor diathesis was identified in the background [Figure 2a and b]. The cell block sections and thyroid CNB [Figure 2c] showed metastatic SCC, confirmed with positive immunohistochemical stains for CK5/6 [Figure 2d] and p63 [Figure 2e]. Staining with p16 was negative [Figure 2f]. Both of the patient's tumors, namely the SCC and the melanoma, subsequently progressed in the neck, leading to airway compromise. The patient passed away 11 months after thyroid metastasis.

Figure 2.

Nasopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma to thyroid. (a) Spindled tumor cells with dense orangeophilic to green–blue cytoplasm on fine-needle aspiration (×1000, Pap). (b) Tumor cells with well-demarcated cell boundaries, dense basophilic cytoplasm, and hyperchromatic nuclei on fine-needle aspiration (×1000, Diff-Quik). (c) Cell block showing metastatic squamous cell carcinoma (×400, H and E), immunopositive for cytokeratin 5/6 (d), p63 (e), and negative for p16 (f) (×200)

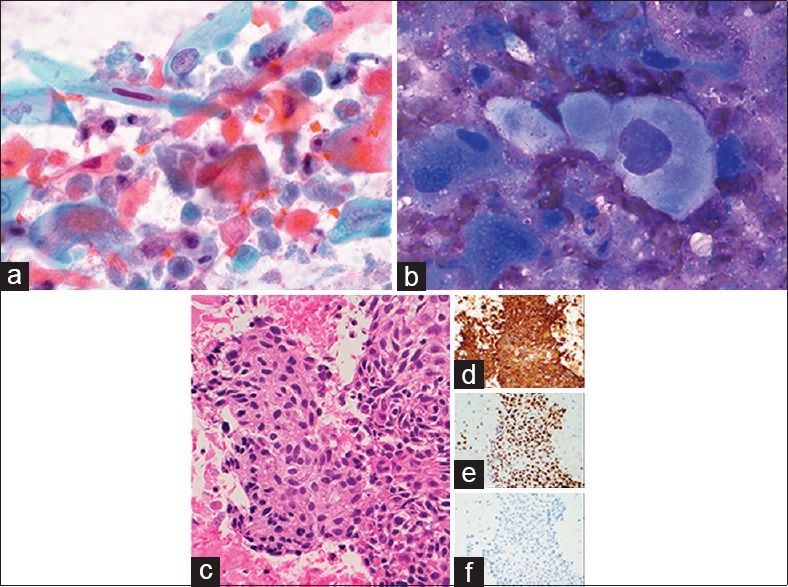

Case 3: Metastatic renal cell carcinoma

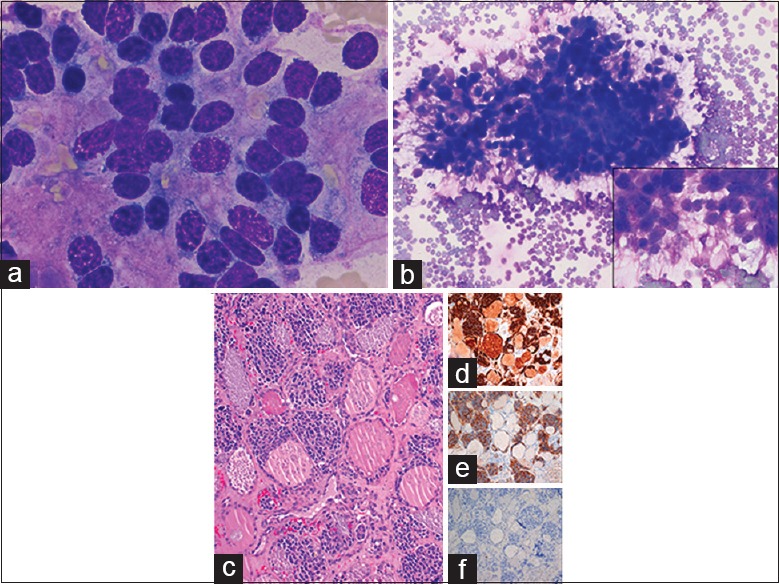

A 69-year-old female with no significant prior medical history presented with an asymptomatic 2.0 cm right thyroid mass. She was referred to the radiology department where an ultrasound-guided CNB was performed. The ROSE imprint cytology was of moderate cellularity and contained multiple cellular clusters that were loosely cohesive [Figure 3a]. The cells displayed hyperchromatic, mostly ovoid nuclei with indistinct cytoplasmic borders. Partially denuded tumor nuclei with occasional nucleoli were also observed [Figure 3b]. The tumor cytoplasm was abundant and extensively vacuolated [Figure 3a]. The background also contained numerous clear extracellular vacuoles [Figure 3b]. The CNB showed aggregates of tumor cells with abundant clear cytoplasm consistent with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) [Figure 3c]. Immunohistochemical stains were positive for RCC [Figure 3d], CD10 [Figure 3e], and PAX2 [Figure 3f]. A subsequent abdominal CT scan revealed a 6.9 cm left kidney mass. A radical nephrectomy confirmed the diagnosis of Fuhrman nuclear grade 2 renal cell cancer.

Figure 3.

Metastatic renal cell carcinoma to thyroid. (a) Tumor cells with abundant clear, vacuolated cytoplasm, and enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei on rapid on-site evaluation imprint cytology (×1000, Diff-Quik). (b) Partially denuded tumor nuclei amidst a background of abundant clear extracellular vacuoles (×1000, Diff-Quik). (c) Core needle biopsy showing metastatic clear cell renal carcinoma (×400, H and E) with positive CD10 (d), PAX2 (e), and RCC (f) (×200)

Case 4: Metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma

A 61-year-old male with increasingly severe abdominal pain and weight loss over a 2-month period underwent imaging studies which detected a possible pancreatic pseudocyst as well as omental thickening. He presented to our facility with progressing severity of his symptoms and mild icterus. On physical exam, he was found to have abdominal distension as well as a 2.0 cm right thyroid nodule. Ascitic fluid drainage as well as an ultrasound-guided biopsy of the thyroid was performed, the latter utilizing FNA and CNB. The cytology demonstrated a cellular smear with clusters featuring three-dimensionality and overlapping [Figure 4a]. The nuclei exhibited anisonucleosis with mostly rounded contours, finely dispersed chromatin, and occasional nucleoli. Frequent mucin vacuoles were encountered. There were also single dyscohesive tumor cells containing abundant cytoplasmic mucin with peripherally displaced nuclei [Figure 4b]. On CNB sections, infiltrative ductal glands showed focal mucin production [Figure 4c]. The tumor cells were positive for CK7 [Figure 4d] and cancer antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) [Figure 4e] and negative for TTF-1 [Figure 4f] as well as CK20 and CDX-2, consistent with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. The patient expired 1 month later.

Figure 4.

Metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma to thyroid. (a) Three-dimensional tumor clusters with prominent mucin vacuoles on fine-needle aspiration (×1000, Pap). (b) Single tumor cells with abundant intracytoplasmic mucin on fine-needle aspiration (×1000, Pap). (c) Core needle biopsy showing metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma (×200, H and E) with positive cytokeratin 7 (d), cancer antigen 19-9 (e), and a negative thyroid transcription factor-1 (f) (×200)

Case 5: Metastatic olfactory neuroblastoma

A 50-year-old female previously underwent resection and radiation for olfactory neuroblastoma of the left nasal sinuses. She presented to our facility 7 years later with metastases to the left parotid, left parapharyngeal fat space, left submandibular region, facial bones, neck, and axillary lymph nodes. Furthermore, ultrasound of the neck revealed multiple enlarged bilateral nodules in the thyroid. A FNA was performed under ultrasound guidance. The ROSE imprint cytology was comprised of multiple highly cellular smears containing clusters and single monotonous cells [Figure 5a]. The nuclei were enlarged and hyperchromatic with granular chromatin, mostly smooth nuclear contours, and nuclear molding. Nucleoli were inconspicuous. The nuclei were surrounded by abundant fibrillary matrix with indistinct cellular borders [Figure 5a]. At the periphery, the crowded tumor clusters exhibited fibrillary or neuropil-like processes [Figure 5b and inset]. Homer–Wright rosettes were not observed. Thyroidectomy revealed metastatic olfactory neuroblastoma [Figure 5c], which was further confirmed by positive immunoperoxidase stains for CD56 [Figure 5d], chromogranin [Figure 5e], synaptophysin [Figure 5f], and neuron specific enolase.

Figure 5.

Metastatic olfactory neuroblastoma to thyroid. (a) Hyperchromatic tumor nuclei with nuclear molding surrounded by fibrillary matrix on fine-needle aspiration (×1000, Diff-Quik). (b) Crowded cellular aggregates with fibrillary neuropil-like processes on fine-needle aspiration (×400, Diff-Quik). (c) Thyroidectomy showing organoid tumor nests among remnant follicles (×200, H and E) with positive CD56 (d), chromogranin (e), and synaptophysin stains (f) (×200)

DISCUSSION

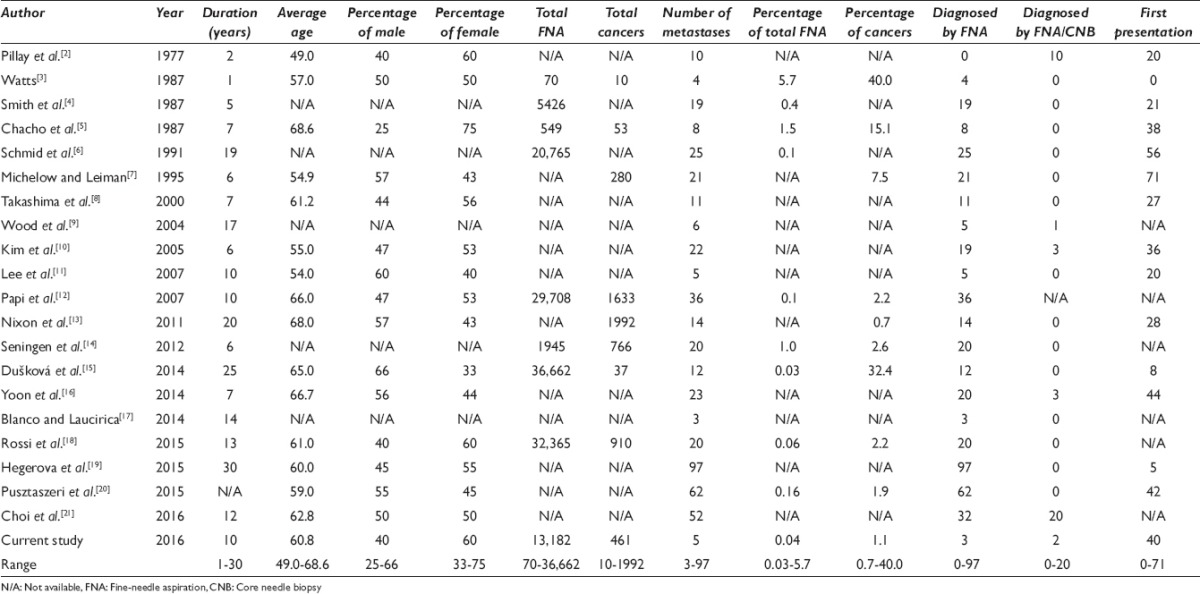

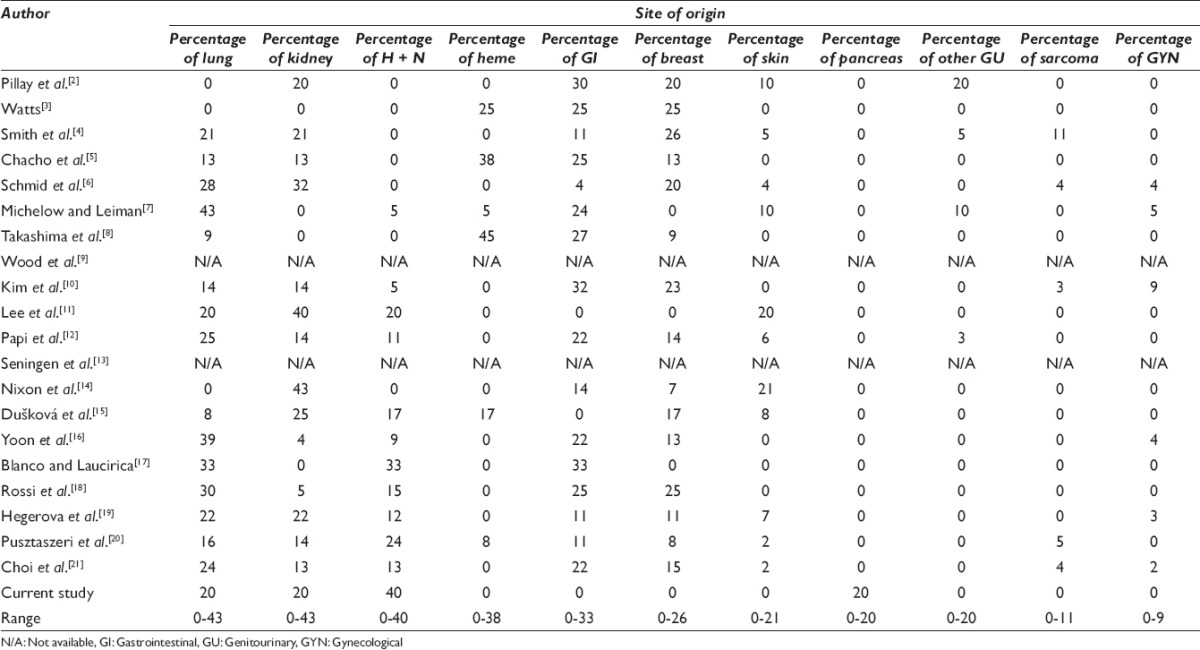

A review of the literature revealed twenty prior studies dating from 1977 to 2016 reporting metastatic tumors to the thyroid assessed by FNA/CNB [Tables 3 and 4]. These studies ranged in duration from 1 to 30 years,[2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21] with the total number of FNA/CNB varying from 70 to 36,662,[3,4,5,6,12,14,15,18] and thyroid cancers from 10 to 1992.[3,5,7,12,13,14,15,18] In these reports, the number of metastases to the thyroid ranged from 3 to 97, totaling 470. Therefore, the incidence of metastases to thyroid was only 0.03%–5.7% of all FNA/CNB[3,4,5,6,12,14,15,18] and 0.7%-40.0% of all thyroid cancers.[3,5,7,12,13,14,15,18] Fourteen studies employed only FNA as a diagnostic modality,[3,4,5,6,7,8,11,12,13,14,15,17,19,20] whereas five studies used a combination of FNA and CNB.[2,9,10,18,21] Among these patients who presented with metastases, there was no overall sex predilection.[2,3,5,7,8,10,11,12,13,15,16,18,19,20,21] The most frequent metastatic cancers to the thyroid were reported to be pulmonary, kidney, and head and neck primaries.[2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]

Table 3.

Literature review of metastatic tumors to the thyroid assessed by fine-needle aspiration/core needle biopsy (1977-2016)

Table 4.

Literature review of the primary site of origin of metastatic tumors to the thyroid assessed by fine-needle aspiration/core needle biopsy (1977-2016)

According to the 2016 SEER database, although the median age at diagnosis of primary thyroid cancer is 51, such patients may exhibit a very wide age range. Although the majority of patients are aged 45 or older, approximately 36% of patients with primary thyroid cancer are under the age of 45. In contrast, metastatic lesions to the thyroid appear to be an infrequent phenomenon for patients under the age of 45 years.[1] Including our cases, patients with metastatic disease to the thyroid ranged in age from 7 to 89 years (average 61) [Table 3].[2,3,5,7,8,10,11,12,13,15,16,18,19,20,21] We identified only 16 (3.5%) patients who presented with metastases under the age of 45 years.[2,3,5,7,8,10,11,13,15,18,20] The metastases in this younger age group included cancers originating in the lung, breast, gastrointestinal tract, soft tissue sarcomas, kidney, melanoma, and cervix.

ROSE was utilized in all cases with 100% correlation with the subsequent histologic diagnosis, proving to be valuable in assuring specimen adequacy. In addition to our study, five studies also utilized CNB in their evaluation of metastases to the thyroid [Table 3].[2,9,10,16,21] Of these five, only Choi et al.[21] performed any sort of specimen adequacy evaluation and only by visually examining their CNB for grossly identifiable thyroid tissue rather than evaluating them microscopically. On the other hand, we performed a microscopic ROSE not only on our FNA specimens but also on all of our CNB by imprinting the biopsy tissue on a slide. In the diagnosis of metastatic disease to the thyroid, it is imperative to obtain adequate tissue for immunoperoxidase confirmation either through FNA cell block or a CNB specimen. Therefore, it is our belief that ROSE should be applied not only to thyroid FNA but also for all thyroid CNB.

Metastasis to the thyroid was the first manifestation of malignancy in up to 71% of cases in some FNA series [Table 3].[7] The most common malignancies that initially presented in the thyroid were lung cancers (37%)[4,6,7] and renal cell carcinomas (22%)[2,5,6] followed by gastric adenocarcinomas (10%).[7] In examining the metastatic lung cancers further, eight were SCCs,[4,6,7,10,12] four were small cell cancers,[4,6] and three were large cell undifferentiated carcinomas.[7]

Cytology of metastatic squamous cell carcinomas to the thyroid

Lung cancers, as well as head and neck carcinomas, are common sources of metastases to the thyroid representing up to 43% and 40% of cases, respectively [Table 4].[7,17] Of the 42 cases of metastatic lung carcinomas diagnosed by thyroid FNA and/or CNB including ours,[4,5,6,7,12,17,18] 14 (33%) cases were SCCs.[4,6,7,10,12] Of the 45 metastatic head and neck cancers, 25 (56%) cases were SCCs.[7,9,10,12,15,17,18,20] Specifically examining all metastatic SCCs to the thyroid, 44% were from the head and neck region,[7,9,10,12,15,17,18,20] 28% had their origin in the lung,[4,6,7,10,11,12] 23% were from the esophagus,[2,4,12,18] 3.5% from the uterine cervix,[10] and 1.8% were from skin.[12] One differential diagnostic cytologic entity to keep in mind is squamous metaplasia, which may be seen in a wide variety of lesions.[23] Squamous metaplasia has been associated with cystic thyroid lesions, including intrathyroidal lymphoepithelial lesions and cysts, epidermoid cysts, thyroglossal duct remnants, and branchial cleft cysts. It may also be present in chronic lymphocytic (Hashimoto’s) thyroiditis and may represent modified Hurthle cells. It can also be seen in malignant lesions such as papillary, anaplastic, squamous, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, or carcinomas with thymus-like differentiation. Cytomorphologically, squamous metaplasia may exhibit abundant benign squamous cells which are predominantly anucleate, with occasional single or groups of nucleated cells. However, diagnostic challenges occur when there is mild-to-moderate squamous atypia with increased N:C ratios and nuclear membrane irregularities amidst a mixed inflammatory background, usually in the setting of Hashimoto's thyroiditis or cystic change. However, frankly malignant squamous cells are rarely encountered in these situations.

Another entity which must be considered in the differential diagnosis is anaplastic (undifferentiated) thyroid carcinoma with squamous differentiation.[24] In general, most cases of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma contain a heterogeneous tumor cell population comprised of epithelioid, spindled, squamous, and multinucleated giant cells. However, tumors with a single cell population may be encountered, consisting only of malignant squamous cells. In fact, Jin et al.[24] reported a case initially interpreted as anaplastic thyroid carcinoma that was later determined to be a metastatic SCC from an unknown source. Therefore, in the absence of reliable clinical history, it may be difficult to differentiate cases of metastatic SCC from anaplastic thyroid carcinoma.

In a review of 59 cases of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma diagnosed by FNA, immunohistochemical TTF-1 staining performed on 10 of their cases was entirely negative.[24] In contrast, PAX8 staining has been shown to be positive in 76% to 79% of all histologic subtypes of anaplastic thyroid cancer, while the squamous variant was positive in 100% of cases.[25] PAX8 is reported to be negative in head and neck SCCs,[24,26] and positive in only 33% of pulmonary SCCs.[26] Therefore, PAX8 staining may be useful in distinguishing metastatic SCC from primary squamous cancers of the thyroid.

Cytology of metastatic renal cell carcinoma to the thyroid

Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the thyroid has been reported extensively in the literature, with some authors suggesting that it is the most common neoplasm to metastasize to the thyroid.[6] In our literature review of metastatic tumors to the thyroid assessed by FNA and CNB, a wide range (0%–43%) of metastatic renal cell carcinoma prevalence has been reported [Table 4].[2,4,5,6,10,11,12,13,15,16,18,19,20,21]

A diagnostic pitfall worth noting is that metastatic clear cell renal carcinoma shares cytomorphologic features with papillary thyroid carcinomas and follicular thyroid neoplasms with clear cell features.[6,9,24] Yang et al. noted that the trabecular or insular growth pattern seen in clear cell papillary thyroid carcinoma may lead to diagnostic confusion with metastatic renal cell carcinoma.[27] However, the nuclear features of clear cell papillary thyroid carcinoma, including clear nuclei with targetoid cytoplasmic inclusions as well as intranuclear grooves, aid in readily distinguishing it from renal cell carcinoma.

In cytologic smears of follicular neoplasms with clear cell features, the tumor nuclei were small to variably sized with round features and granular chromatin.[27] The cytoplasm exhibited prominent cytoplasmic vacuolization with equally or variably sized vesicles or lipid droplets.[27,28] Thus, the similarities between the clear cell follicular carcinoma and metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma are striking and distinguishing the two entities may be challenging.[28] Wood et al. noted that thyroid follicular neoplasms with clear cell features maintain some cytoplasmic granularity, whereas metastatic renal cell carcinomas do not.[9] In contrast, the presence of cytoplasmic glycogen and lipid would favor a metastatic renal cancer.[9] However, metastatic renal cell carcinoma with oncocytic features such as granular cytoplasm and bland nuclei may also be misinterpreted as a Hurthle cell neoplasm.[20]

Immunohistochemical staining may be employed to reliably distinguish between metastatic renal cell carcinoma and primary thyroid neoplasms with clear and granular cell features when histologic cell block material is available. Clear cell thyroid neoplasms tend to express TTF-1 uniformly and thyroglobulin in tumor cells without clear cytoplasm, whereas renal cell carcinomas express CD10 cytoplasmically and are negative for TTF-1.[24] Other markers which may be positive in clear cell renal cell carcinomas are PAX8 (92%) and PAX2 (92%).[29] In comparison, papillary thyroid carcinomas will always stain for PAX8 (100%)[26] but not PAX2 (0%).[30] The RCC marker is also not helpful in differentiating between these two entities as it is positive in both clear cell renal cell carcinoma (72%–85%)[29] and papillary thyroid carcinoma (100%).[30] Therefore, a panel of immunohistochemical stains, including TTF-1, CD10, and PAX2, may be most beneficial in distinguishing metastatic renal cell cancer from primary thyroid cancers with clear cell features.

Cytology of metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma to thyroid

Although there were no cases of metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma within the FNA series of metastases to the thyroid [Table 3], there are a few isolated case reports in the literature.[31,32,33,34] Interestingly, most of these articles described their cases of metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma that were initially misdiagnosed as putative primary thyroid cancer. Delitala et al.[31] reported a case of a 63-year-old man with pancreatic cancer who underwent FNA of a thyroid lesion. Although no cytomorphological description was given, the cytologic specimen was classified as malignant per the Bethesda criteria, and the patient was referred for possible thyroidectomy. In addition, Kelly et al.[32] described a thyroid FNA specimen containing only a small amount of “follicular” cells with papillary architecture which did not demonstrate classical features of papillary thyroid carcinoma. The case was reported as a suspected atypical papillary thyroid carcinoma. Further systemic workup also revealed a mass in the pancreas, which showed a ductal adenocarcinoma on resection. Eight weeks later, the patient underwent a total thyroidectomy, which demonstrated a metastatic adenocarcinoma with histologic features similar to pancreatic cancer. Finally, Hsiao et al.[33] reported a case of a 45-year-old male with a pancreatic mass which was radiologically suspected to be an intraductal pancreatic mucinous neoplasm. The patient developed cervical and periaortic lymphadenopathy, liver, bone, adrenal, and skin metastases as well as a rapidly growing tender thyroid mass. FNA of the thyroid produced smears of moderate cellularity with branching papillary fronds exhibiting nuclear pleomorphism. There were also aggregates of three-dimensional tumor nests, as well as individual tumor cells with prominent nucleoli and abundant cytoplasm. The background contained an amorphous mucoid substance and cellular debris. Despite the notable clinical history, the authors were not able to exclude a papillary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroidectomy was performed, which confirmed the diagnosis of a metastatic pancreatic intraductal papillary neoplasm.

In the latter two of these prior reported cases,[32,33] the diagnoses of metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma were established only after the patients underwent thyroidectomy. Cytologic examinations of both thyroid FNA specimens led to erroneous diagnoses of atypical papillary thyroid carcinoma, due to the papillary architecture manifested by the metastases. However, in both instances, the classic nuclear features of papillary thyroid carcinoma, namely oval nuclei with fine chromatin, and intranuclear nuclear inclusions and grooves were not reported. Furthermore, in one case,[33] nuclear features incongruous with the diagnosis of papillary thyroid cancer, namely prominent nucleoli, were also noted. Therefore, careful attention to the characteristic cytodiagnostic features of papillary thyroid carcinoma is essential in achieving an accurate diagnosis.

Pancreatic cancer may also manifest with thyroid metastasis prior to a cancer diagnosis as was observed with our patient. Eriksson et al.[34] described a 54-year-old male who developed a neck skin mass and a diffusely enlarged thyroid. Thyroid FNA showed plump neoplastic cells forming acini and containing mucin surrounding follicular cells. The patient expired 8 weeks later, and postmortem examination revealed pancreatic cancer with widespread metastases.

With Eriksson's[34] study and our cases, the tumors appeared poorly differentiated, with neoplastic cells forming acini or three-dimensional clusters with nuclear overlapping, plump or abundant cytoplasm, and occasional nucleoli. Therefore, cytologic differentiation from primary poorly differentiated thyroid cancer may be difficult. However, intracellular mucin was identified in both cases, which is not usually observed in primary poorly differentiated thyroid cancer.[35] Furthermore, immunohistochemical stains may be useful in the differentiation. Delitala et al.[31] were able to perform immunohistochemistry on their patients’ subsequent thyroid CNB. Tumor staining was positive with CK19 and negative for TTF-1, confirming the diagnosis of metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma and thereby preventing a thyroidectomy. We also performed immunohistochemical staining on our patient's thyroid CNB, which demonstrated tumor positivity with CK7 and CA19-9 and was negative for TTF-1. In contrast, Kelly et al. and Hsiao et al.[32,33] both examined only FNA specimens and were unable to perform immunohistochemical confirmation on either CNB or cell block specimens, which may have contributed to their diagnostic difficulties.

Cytology of metastatic olfactory neuroblastoma to the thyroid

We report the first known case of metastatic olfactory neuroblastoma to the thyroid diagnosed by FNA. Olfactory neuroblastoma is a rare neoplasm of neuroectodermal origin comprising only 1% to 5% of nasal cavity neoplasms.[36] Sixty-five percent of olfactory neuroblastoma patients reported in the cytologic literature had a diagnosis rendered from either a soft tissue swelling or a lymph node of the neck region,[37,38,39,40,41,42,43] indicating a predilection for locoregional spread. However, metastases to distant sites have also been reported, and cytologic exam has been employed to identify metastatic olfactory neuroblastoma in loci such as pleural fluid,[37] scalp,[38] liver, spine, and parotid.[39] In fact, our patient with nasal cavity olfactory neuroblastoma also developed extensive metastases involving the cervical and axillary lymph nodes, parotid gland, and facial bones.

Cytomorphological descriptions of primary olfactory neuroblastoma have been reported in the literature.[38,39,44,45,46] The tumor cells were found in loose clusters and singly[38,39,44,45] and were described as being small in size and round to oval in shape.[38,39,38,39,40] The nuclei were also round to oval, hyperchromatic with slight size variation, smooth nuclear membranes,[39] finely dispersed and/or granular chromatin,[38,39,44,45,46] and an indistinct nucleolus.[38,39,44,46] Mahooti and Wakely[38] also described a two-cell population consisting of tumor cells with viable nuclei and others with pyknotic/karyorrhectic apoptotic nuclei. They also noted the presence of paranuclear blue bodies that indented the nuclei.[38] The cytoplasm of primary olfactory neuroblastoma has been described as scanty[38,39,45] and having a fibrillary quality.[39,45,46] In fact, neurofibrillary stroma was identified in 80% of the primary olfactory neuroblastomas reported in the FNA literature.[38,45,46] In addition, rosette formation was also noted in 80% of cases.[38,44,45,46]

Most of the cases of metastatic olfactory neuroblastoma diagnosed by FNA demonstrated cytomorphologic features similar to those seen in primary olfactory neuroblastoma, including hyperchromatic nuclei with small and/or indistinct nucleoli, molding, and scant cytoplasm.[37,40,41,42,43] The more defining cytologic features of olfactory neuroblastoma, namely the presence of neurofibrillary matrix and rosette formation, were identified in 72%[37,40,41,42,43] and 68%[37,40,41,42,43] of the cases, respectively. Although our case demonstrated neurofibrillary features, no rosettes were seen.

Poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma may exhibit some cytomorphologic features similar to metastatic olfactory neuroblastoma. Like olfactory neuroblastoma, poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma features isolated tumor cells alternating with groups of uniform tumor cells with round nuclei, high N:C ratios, and apoptosis.[35] However, unlike olfactory neuroblastoma, poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma may show insular, solid, or trabecular architecture. Furthermore, only slight nuclear size variability is seen in olfactory neuroblastoma,[39] whereas poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma may demonstrate varying degrees of nuclear atypia, with nuclear pleomorphism and anisokaryosis in the majority of the cases.[35] Finally, the cardinal features of olfactory neuroblastoma, namely, neurofibrillary stroma and rosette formation are absent in poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma.[38,39,44,45,46] Immunohistochemical staining is also useful in the distinction as poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma is positive with TTF-1 and thyroglobulin and negative for chromogranin.[35]

Medullary thyroid carcinoma must also be considered in the cytologic differential diagnosis. The cellular architectural arrangement in cytological smears can appear similar to an olfactory neuroblastoma, with the cells appearing singly or in loosely cohesive clusters.[47] However, the cellular morphologic features in medullary thyroid carcinoma are invaluable in differentiating these two entities. While metastatic olfactory neuroblastoma demonstrates hyperchromatic nuclei with molding and high N:C ratios, medullary carcinoma exhibits eccentric nuclei with a salt and pepper chromatin pattern and abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm, imparting a plasmacytoid appearance. Other medullary carcinoma variants feature spindled or multinucleated tumor cells. In addition, the background may contain amyloid-like material present in the form of strings or round to oval-shaped fragments. Immunohistochemically, both olfactory neuroblastoma and medullary thyroid carcinoma stain positively with synaptophysin and chromogranin.[38,39,41,42,43,47] Unlike olfactory neuroblastoma, calcitonin is positive in medullary thyroid carcinoma.[47] Carcinoembryonic antigen is also positive in medullary carcinoma,[47] while generally negative in olfactory neuroblastoma.[42]

CONCLUSION

Metastasis to the thyroid is a rare occurrence in our institution, with an incidence of 0.04% and 1.1% of all FNA/CNB and total malignancies, respectively, compared to 0.03%–5.7% and 0.7%-40.0% reported within the literature [Table 3]. Despite the higher rates of thyroid cancer in Hawaii, our incidence of metastases to the thyroid is lower than those cited in prior reported articles. Most of our metastases originated in the head and neck (40%), whereas those in literature mostly disseminated from the lung and kidney (43%). In addition, cytopathologists should be aware that an occult primary may present as a thyroid mass on FNA or CNB, which occurred in 65% of the studies in our literature review. In fact, two of our metastases, a metastatic renal cancer and pancreatic adenocarcinoma, were the initial manifestations of malignancy in these patients.

FNA/CNB proved to be highly effective in the diagnosis of metastases to the thyroid. The morphologic features of metastases to the thyroid were similar to those reported in the cytology literature and aided in their distinction from primary thyroid carcinoma. In the diagnosis of metastatic disease to the thyroid, it is essential to obtain tissue for immunoperoxidase confirmation either through FNA cell block or even a CNB specimen. ROSE enabled us to assure specimen adequacy not only of our FNA cases but also for our thyroid CNB specimens, and thus proved to be of great utility in obviating the need for more invasive procedures in the setting of metastatic disease.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

MR: Manuscript preparation, data analysis, photomicroscopy, literature review. ARO: Data gathering and analysis, photomicroscopy, literature review. KG: Data analysis, photomicroscopy, literature view. PTN: Study concept design, manuscript drafting/editing/revision for intellectual content, guarantor of integrity of study.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This original research was approved by the Queens Medical Center Institutional Review Board (# RA-2015-004). This study was presented in part at the American Society of Cytopathology annual meeting held in Chicago, Illinois, in November of 2015. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (In alphabetic order)

CA 19-9 – Cancer antigen 19-9

CK - Cytokeratin

CNB - Core needle biopsy

CT - Computerized tomographic

FNA - Fine-needle aspiration

N:C - Nuclear-cytoplasmic

Pap - Papanicolaou

ROSE - Rapid on-site evaluation

SCC – Squamous cell carcinoma

SEER - Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

TTF1 – Thyroid transcription factor 1

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind model (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system.

Contributor Information

Mobeen Rahman, Email: mobeen@hawaii.edu.

Ashley Rae Okada, Email: ashleyraeo@gmail.com.

Kevin Guan, Email: kvguan@gmail.com.

Pamela Tauchi-Nishi, Email: pnishi@queens.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Bishop K, Altekruse SF, et al., editors. SEER cancer statistics review. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 1975-2013. [Based on November 2015 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2016]. Available from: http://www.seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2013/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pillay SP, Angorn IB, Baker LW. Tumour metastasis to the thyroid gland. S Afr Med J. 1977;51:509–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watts NB. Carcinoma metastatic to the thyroid: Prevalence and diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration cytology. Am J Med Sci. 1987;293:13–7. doi: 10.1097/00000441-198701000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith SA, Gharib H, Goellner JR. Fine-needle aspiration. Usefulness for diagnosis and management of metastatic carcinoma to the thyroid. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:311–2. doi: 10.1001/archinte.147.2.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chacho MS, Greenebaum E, Moussouris HF, Schreiber K, Koss LG. Value of aspiration cytology of the thyroid in metastatic disease. Acta Cytol. 1987;31:705–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmid KW, Hittmair A, Ofner C, Tötsch M, Ladurner D. Metastatic tumors in fine needle aspiration biopsy of the thyroid. Acta Cytol. 1991;35:722–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michelow PM, Leiman G. Metastases to the thyroid gland: Diagnosis by aspiration cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 1995;13:209–13. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840130306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takashima S, Takayama F, Wang JC, Saito A, Kawakami S, Kobayashi S, et al. Radiologic assessment of metastases to the thyroid gland. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2000;24:539–45. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200007000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wood K, Vini L, Harmer C. Metastases to the thyroid gland: The Royal Marsden experience. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30:583–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim TY, Kim WB, Gong G, Hong SJ, Shong YK. Metastasis to the thyroid diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2005;62:236–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee MW, Batoroev YK, Odashiro AN, Nguyen GK. Solitary metastatic cancer to the thyroid: A report of five cases with fine-needle aspiration cytology. Cytojournal. 2007;4:5. doi: 10.1186/1742-6413-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papi G, Fadda G, Corsello SM, Corrado S, Rossi ED, Radighieri E, et al. Metastases to the thyroid gland: Prevalence, clinicopathological aspects and prognosis: A 10-year experience. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;66:565–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nixon IJ, Whitcher M, Glick J, Palmer FL, Shaha AR, Shah JP, et al. Surgical management of metastases to the thyroid gland. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:800–4. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1408-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seningen JL, Nassar A, Henry MR. Correlation of thyroid nodule fine-needle aspiration cytology with corresponding histology at Mayo Clinic, 2001-2007: An institutional experience of 1,945 cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;40(Suppl 1):E27–32. doi: 10.1002/dc.21566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dušková J, Rosa P, Preucil P, Svobodová E, Lukáš J. Secondary or second primary malignancy in the thyroid? metastatic tumors suggested clinically: A differential diagnostic task. Acta Cytol. 2014;58:262–8. doi: 10.1159/000360805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon JH, Kim EK, Kwak JY, Moon HJ, Kim GR. Sonographic features and ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration of metastases to the thyroid gland. Ultrasonography. 2014;33:40–8. doi: 10.14366/usg.13014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blanco EM, Laucirica R. Metastatic lesions involving the thyroid gland diagnosed by fine needle aspiration biopsy. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2014;3:S51–2. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossi ED, Martini M, Straccia P, Gerhard R, Evangelista A, Pontecorvi A, et al. Is thyroid gland only a “land” for primary malignancies? role of morphology and immunocytochemistry. Diagn Cytopathol. 2015;43:374–80. doi: 10.1002/dc.23241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hegerova L, Griebeler ML, Reynolds JP, Henry MR, Gharib H. Metastasis to the thyroid gland: Report of a large series from the Mayo Clinic. Am J Clin Oncol. 2015;38:338–42. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e31829d1d09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pusztaszeri M, Wang H, Cibas ES, Powers CN, Bongiovanni M, Ali S, et al. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of. ondary neoplasms of the thyroid gland: A multi-institutional study of 62 cases. Cancer Cytopathol. 2015;123:19–29. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi SH, Baek JH, Ha EJ, Choi YJ, Song DE, Kim JK, et al. Diagnosis of metastasis to the thyroid gland: Comparison of core-needle biopsy and fine-needle aspiration. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;154:618–25. doi: 10.1177/0194599816629632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Witt BL, Schmidt RL. Rapid onsite evaluation improves the adequacy of fine-needle aspiration for thyroid lesions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thyroid. 2013;23:428–35. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gage H, Hubbard E, Nodit L. Multiple squamous cells in thyroid fine needle aspiration: Friends or foes? Diagn Cytopathol. 2016;44:676–81. doi: 10.1002/dc.23512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin M, Jakowski J, Wakely PE. Undifferentiated (anaplastic) thyroid carcinoma and its mimics: A report of 59 cases. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2016;5:107–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jasc.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bishop JA, Sharma R, Westra WH. PAX8 immunostaining of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: A reliable means of discerning thyroid origin for undifferentiated tumors of the head and neck. Hum Pathol. 2011;42:1873–7. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laury AR, Perets R, Piao H, Krane JF, Barletta JA, French C, et al. A comprehensive analysis of PAX8 expression in human epithelial tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:816–26. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318216c112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang GC, Fried K, Scognamiglio T. Cytological features of clear cell thyroid tumors, including a papillary thyroid carcinoma with prominent hobnail features. Diagn Cytopathol. 2013;41:757–61. doi: 10.1002/dc.22935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jayaram G. Cytology of clear cell carcinoma of the thyroid. Acta Cytol. 1989;33:135–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Truong LD, Shen SS. Immunohistochemical diagnosis of renal neoplasms. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:92–109. doi: 10.5858/2010-0478-RAR.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma SG, Gokden M, McKenney JK, Phan DC, Cox RM, Kelly T, et al. The utility of PAX-2 and renal cell carcinoma marker immunohistochemistry in distinguishing papillary renal cell carcinoma from nonrenal cell neoplasms with papillary features. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2010;18:494–8. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e3181e78ff8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delitala AP, Vidili G, Manca A, Dial U, Delitala G, Fanciulli G. A case of thyroid metastasis from pancreatic cancer: Case report and literature review. BMC Endocr Disord. 2014;14:6. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-14-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelly ME, Kinsella J, d’Adhemar C, Swan N, Ridgway PF. A rare case of thyroid metastasis from pancreatic adenocarcinoma. JOP. 2011;12:37–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsiao PJ, Tsai KB, Lai FJ, Yeh KT, Shin SJ, Tsai JH. Thyroid metastasis from intraductal papillary-mucinous carcinoma of the pancreas. A case report. Acta Cytol. 2000;44:1066–72. doi: 10.1159/000328599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eriksson M, Ajmani SK, Mallette LE. Hyperthyroidism from thyroid metastasis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. JAMA. 1977;238:1276–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bongiovanni M, Bloom L, Krane JF, Baloch ZW, Powers CN, Hintermann S, et al. Cytomorphologic features of poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma: A multi-institutional analysis of 40 cases. Cancer. 2009;117:185–94. doi: 10.1002/cncy.20023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Connor TA, McLean P, Juillard GJ, Parker RG. Olfactory neuroblastoma. Cancer. 1989;63:2426–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890615)63:12<2426::aid-cncr2820631209>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jobst SB, Ljung BM, Gilkey FN, Rosenthal DL. Cytologic diagnosis of olfactory neuroblastoma. Report of a case with multiple diagnostic parameters. Acta Cytol. 1983;27:299–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahooti S, Wakely PE., Jr Cytopathologic features of olfactory neuroblastoma. Cancer. 2006;108:86–92. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bellizzi AM, Bourne TD, Mills SE, Stelow EB. The cytologic features of sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma and olfactory neuroblastoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:367–76. doi: 10.1309/C00WN1HHJ9AMBJVT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fagan MF, Rone R. Esthesioneuroblastoma: Cytologic features with differential diagnostic considerations. Diagn Cytopathol. 1985;1:322–6. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840010411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Logrono R, Futoran RM, Hartig G, Inhorn SL. Olfactory neuroblastoma (esthesioneuroblastoma): Appearance on fine-needle aspiration: Report of a case. Diagn Cytopathol. 1997;17:205–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(199709)17:3<205::aid-dc7>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Collins BT, Cramer HM, Hearn SA. Fine needle aspiration cytology of metastatic olfactory neuroblastoma. Acta Cytol. 1997;41:802–10. doi: 10.1159/000332707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chung J, Park ST, Jang J. Fine needle aspiration cytology of metastatic olfactory neuroblastoma: A case report. Acta Cytol. 2002;46:40–5. doi: 10.1159/000326714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferris CA, Schnadig VJ, Quinn FB, Des Jardins L. Olfactory neuroblastoma. Cytodiagnostic features in a case with ultrastructural and immunohistochemical correlation. Acta Cytol. 1988;32:381–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jelen M, Wozniak Z, Rak J. Cytologic appearance of esthesioneuroblastoma in a fine needle aspirate. Acta Cytol. 1988;32:377–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prasad N, Prasad P, Kishnani K. Diagnosis of olfactory neuroblastoma by cytology. J Indian Med Assoc. 1990;88:86–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baloch ZW, LiVolsi VA, Asa SL, Rosai J, Merino MJ, Randolph G, et al. Diagnostic terminology and morphologic criteria for cytologic diagnosis of thyroid lesions: A synopsis of the National Cancer Institute Thyroid Fine-Needle Aspiration State of the Science Conference. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:425–37. doi: 10.1002/dc.20830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]