Abstract

Background:

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) often results in a wide range of comorbid conditions, predominantly of the cardiovascular/respiratory, endocrine/metabolic, and neuropsychiatric symptoms. In view of the ambiguity of literature regarding the association between OSA and depression, we conducted this study to show any association between the two disorders.

Objective:

The aim of the study was to see the association between OSA and depression and to study the prevalence of OSA in patients suffering from depression.

Methods:

We performed polysomnography (PSG) studies of patients that were referred from various subspecialty clinics from July 2011 to August 2013. Psychiatric diagnosis was done using mini international neuropsychiatric interview plus scale. This was followed by application of Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D). Standard methods of statistical analysis were used for data analysis.

Results:

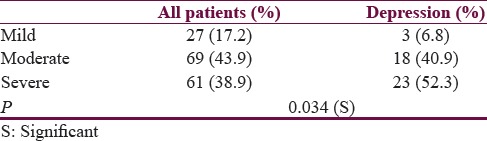

Out of 182 patients who underwent PSG, 47 were suffering from depression with a mean age significantly more (P < 0.001) than that of other population (58.60 years vs. 53.60 years). In our 47 depressed patients, 44 (93.6%) had abnormal PSG. Based on apnea-hypopnea index score, 3 (6.8%) patients had mild, 18 (40.9%) had moderate, and 23 (52.3%) had severe OSA. The mean HAM-D score was significantly more in depression patients, (17. 35 ± 5.45) as compared to non depressive patents (8.64 ± 6.24) (P = 0.0001).

Conclusion:

This study demonstrates significant overlap between the sleep apnea and depression. Health specialists need more information about screening for patients with OSA to ensure proper diagnosis and treatment of those with the condition. Most of the clinicians do not suspect this important comorbidity of depression in the beginning resulting in delayed diagnosis.

KEYWORDS: Depression, obstructive sleep apnea, psychiatric disorders

INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a sleep-related breathing disorder characterized by repetitive upper airway obstruction, which causes frequent episodes of reduced (hypopnea) or no airflow (apnea) during sleep.[1] OSA is common in the adult population, with a prevalence of approximately 5%.[2] Over 80% of individuals with moderate–to-severe OSA have not been clinically diagnosed by their health-care providers.[3] OSA may negatively affect multiple organs, resulting in the development of cardiovascular diseases and neurocognitive problems.[4] The disordered breathing during sleep exerts its multiorgan, pathological effects through the mechanism of sympathetic stimulation caused by arousal from sleep.[5] Recent epidemiologic studies have shown that untreated OSA is associated with a plethora of adverse health conditions including multiple psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety.[6] Most of the studies have shown a significant association between the psychiatric disorders and OSA. However, few studies have ruled out any association between the OSA and psychiatric disorders.[7,8] More ever, according to few researchers, the association is purely due to misinterpretation by medical team.[9]

The mental changes may be provoked by biological and/or psychosocial consequence of OSA.[10] Psychiatric comorbidity in OSA has been reported to adversely affect the quality of life of OSA patients and impaired neurocognitive functioning.[11] Depression, anxiety, cognitive defects, and other psychological problems have been linked with OSA.[12] Some psychological impairments are reversible with treatment, and some persist even after treatment.[13,14] High prevalence of personality disturbances and depression is found in a patient suffering from OSA.[15] In view of the ambiguity of literature regarding the association between OSA and psychiatric symptoms, we conducted this study to show any association between the two disorders.

METHODS

This cross-sectional study was carried out at the Modern Hospital, Srinagar. Modern Hospital is a private hospital located in Rajbagh that provides the full spectrum of primary care and specialty services through its own salaried professional staff. Patients from all parts of Jammu and Kashmir are referred to hospital as the standard polysomnographic studies with accredited laboratory are only available here in the hospital. The enrollee population in Modern Hospital is comparable to the surrounding community with respect to race. The records of 182 patients referred for polysomnography (PSG) between July 2011 and August 2013 were examined.

Exclusion criteria

Patients on nocturnal oxygen supplementation

Unstable cardiopulmonary, neurological, or psychiatric disease

Upper airway surgery

Using positive airway pressure therapy or oral appliances.

All participants gave written informed consent before PSG. All patients underwent overnight PSG for the assessment of sleep disordered breathing by means of a computer-based system. Demographic data, general medical history, clinical information from the initial visit for sleep-related complaints, as well as PSG results for cases, were recorded. A detailed history of complaints including snoring, witnessed apneas, nocturia, disturbed nocturnal sleep, and morning headaches was taken. Daytime sleepiness was assessed by the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS).[16] Anthropometric measurements including height, weight, and neck circumference were measured in all patients, and blood pressure of each participant was recorded. An overnight laboratory PSG was then performed to diagnose the presence and severity of OSA (OSAS). PSG recordings were started based on the participant's usual domestic sleeping habits, and each patient was recorded for a minimum of 7 h.

Polysomnographic recordings included

Recordings of airflow by nasal pressure transducer and oronasal thermocouples, chest and abdominal wall motion by piezo electrodes, oxygen saturation (SpO2) by pulse oximeter, electrocardiogram, six electroencephalogram channels, bilateral electrooculograms, and chin and tibialis electromyogram. Data were analyzed on a visual basis by an experienced investigator. Recordings were scored visually in 30 s in non-rapid eye movement (REM) sleep stages 1–4 sleep, and in REM sleep, according to standard criteria.[17] Similarly, respiratory events and microarousals were scored according to established criteria.[18,19]

Sleep was defined according to the criteria of Rechtschaffen and Kales.[17] Apnea was defined as a cessation of airflow for at least 10 s.[1] Hypopnea was defined as a reduction in thoracic-abdominal movements of 50% or more and a decrease of the SpO2 of 4% or more. The apnea/hypopnea index (AHI) was calculated as the number of apneas and hypopneas per hour of total sleep time. OSA was defined as an AHI of 5 or more apneas/hypopneas per hour. Daytime sleepiness was measured by the ESS.[16] A score of more than 9 points was considered as excessive daytime sleepiness. We defined the OSAS as a combination of AHI >5 and an ESS score >9. Oxygen desaturation index (ODI) was defined as the total number of desaturations of at least 3% per total sleep time in hours. We defined OSAS categories according to commonly used clinical cutoffs, i.e., no OSA (AHI <5), mild OSA (AHI ≥5 but <15), moderate OSA (AHI ≥15 but <30), and severe OSA (AHI ≥30).

Psychiatric diagnosis

It was done using mini international neuropsychiatric interview plus scale.[20] This was followed by application of Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D),[21] in patients suffering from referred for PSG. The diagnosis of psychiatric disorder was confirmed by consultant psychiatrist according to the criterion given in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV text revision. Informed consent (written and verbal) was obtained from each patient. Information sheets and preliminary interviews made it clear that the choice to consent or otherwise would have no bearing on the treatment offered. The project ensured the anonymity of the subjects by replacing patient names with unique identifying numbers before the statistical procedures began. Descriptive statistics were used for measuring mean and percentage.

Statistical analysis

Standard methods of statistical analysis were used for data analysis. After descriptive statistical analysis of the general characteristics of the study participants, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to examine the distribution of variables, and Levene test to study the variability. Qualitative variables were analyzed with Chi-square test or with Fisher's exact test if at least one cell had an expected count <5. Student's t-test was applied to compare mean values of quantitative variables when the distribution was normal, and Mann–Whitney U-test when it was not. For paired samples, Student's t-test for paired samples and McNemar test were used. Pearson's coefficient was used to test the correlation between quantitative variables; P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS 11.0 was used for data analyses (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

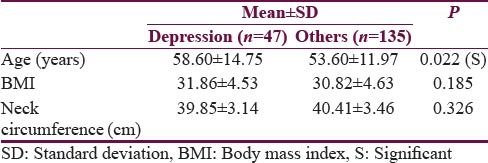

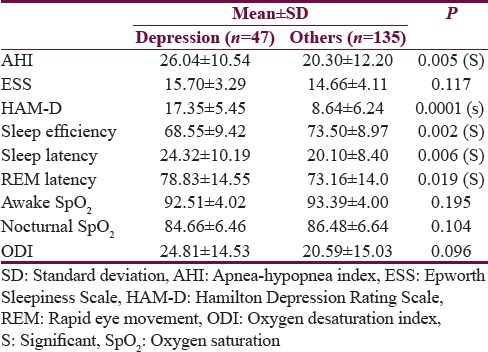

Out of 182 patients who underwent PSG, 47 were suffering from depression with a mean age significantly more (P < 0.001) than that of other population (58.60 years vs. 53.60 years). Body mass index and neck circumference were not statistically different between these two groups (P > 0.005) [Table 1]. The mean HAM-D score was significantly more in depressive patients (P = 0.0001) than in nondepressive patients (mean ± standard deviation [SD] = 17. 35 ± 5.45) as compared to nondepressive (mean ± SD 8.64 ± 6.24). Sleep efficiency was significantly less (P < 0.005) in depression patients (mean 68.55%) as compared to nondepressive (mean 73.50%). Mean Sleep latency was significantly more in depression patients (24.32 min) as compared to nondepressive patients (20.10 min) (P < 0.005). Like sleep latency, mean REM sleep latency was also significantly more depression among patients (78.83 min) as compared to nondepressed population (73.16 min) (P = 0.019). Mean room air, awake SpO2 of depression patients (92.51%) was not significantly less than nondepressed patients (93.39) (P = 0. 195). Like awake SpO2, the average nocturnal SpO2 of depressive patients was not significantly less (P = 0. 104) than that of nondepressive patients, i.e. 84.66.0% versus 86.48.0%. The mean AHI of patients with depression was significantly more than non depression patients, i.e., 26.04 versus 20.30 (P = 0.005 (S). The mean ODI of depression patients was significantly more than depression patients; however, it was not statistically significant, i.e., 24.81 versus 20.59 (P = 0.096) [Table 2].

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the study population (age, body mass index, and neck circumference)

Table 2.

Polysomnography observations in depressive patients versus those without depression

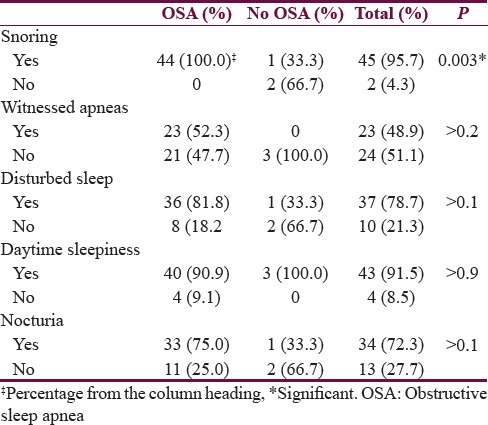

The main presenting symptoms of patients with depression were snoring 60 (96.8%), daytime sleepiness 55 (88.7%) with a mean ESS of 15.3, disturbed nocturnal sleep 43 (69.4%), nocturia 42 (67.7%), and witnessed apneas 27 (43.5%). All these symptoms were more common in patients with depression compared to non depressive patients, and among patients with depression, these were more prevalent in those with OSA than those without OSA.

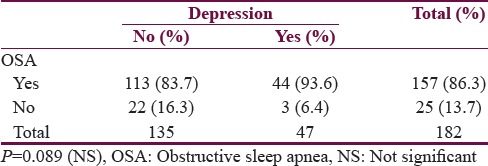

In our 47 depressive patients, only 3 (6.4%) had normal PSG and the remaining 44 (95.2%) had abnormal test [Table 3].

Table 3.

Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in depression

The main presenting symptoms of patients with depression were snoring 44 (100%), daytime sleepiness 40 (93.6%), disturbed nocturnal sleep 36 (81.8%), nocturia 33 (75%), and witnessed apneas 23 (52.3%). All these symptoms were more common in patients with depression compared to nondepressive patients. All patients with depression, having OSA presents with snoring [Table 4].

Table 4.

Patient presentation in depression - with and without obstructive sleep apnea

Based on AHI score, 3 (6.8%) patients had mild, 18 (40.9%) had moderate, and 23 (52.3%) had severe OSA [Table 3]. Compared to nondepressive patients, moderate and severe OSA was significantly more in depressive patients (P = 0. 034 (S)) [Table 5].

Table 5.

Severity of obstructive sleep apnea based on the apnea-hypopnea index

DISCUSSION

OSA is a sleep-related breathing disorder characterized by recurrent upper airway obstruction, which causes frequent episodes of reduced (hypopneas) or no (apneic) airflow during sleep. The end results are specific physiologic disturbances such as sleep fragmentation and chronic intermittent hypoxia.[1] OSA is a well-known risk factor for a plethora of cardiovascular and metabolic disorders which is serious morbidity in psychiatric patients and may lead to reduced expected life span.[2,5] OSA physiopathology and its relationship with depression can be explained by the theory of neuroplasticity.[22] The end result of sleep fragmentation and chronic intermittent hypoxia leads to a cascade of events related to the activation of the sympathoadrenal system, oxidative stress, systemic inflammation, production of inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-2, IL-6, and IL-12, and increases the levels of corticosteroids, which leads to atrophy of the hippocampal neurons and decrease of the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor.[23,24] The consequence of this cascade is decreased mood, and cognitive disorders’ OSA is common in the adult population; it may negatively affect multiple organs, resulting in the development of cardiovascular diseases and neurocognitive problems.[10] There is a general consensus of close relationship between depression and OSA, and further, each of these two conditions can affect patients’ overall health and course of the disease. The presence of depression in OSA has major consequences.[11] Depression adds to treatment complexity, is frequently associated with chronicity, and negatively affects the course of OSA.[13] Most of the studies have shown a significant association between the psychiatric disorder preferably depression and OSA.[25] Depression is a common medical disorder, which remains underrecognized and undertreated.[26] Prevalance of depression in OSA, particularly with respect to patients with other chronic diseases is a debatable issue.[27]

Depression is considered as risk factor for OSA, which can be explained serotonergic neurotransmission. Decrease in muscle tone of the upper respiratory tract and disturbed sleep both are caused due to low serotonin levels.[28] The presence of psychiatric comorbidity in OSA varies and depends on various measures.[29]

The mean age of our depressive patients was significantly more than that of other population (58.60 years vs. 53.60 years). Almost 50% or more than of individuals over the age of 65 years may suffer from OSA, and 26% of elderly population may present with significant depressive symptoms.[30] Nearly 20% of patients with depressive syndrome may present with OSA and vice versa.[30] The association between depression and OSA remains controversial.[27] The comorbidity of OSA in psychiatric patients can cause a lot of negative consequences. To add, many symptoms of OSA can imitate various psychiatric symptoms and can even develop cognitive development.[31] Furthermore, OSA might not only be associated with a depressive syndrome but also its presence may also be responsible for failure to respond to appropriate pharmacological treatment.[13,14]

The mean REM sleep latency was significantly more among depression patients (78.83 min) as compared to nondepression population (73.16 min) in our study. Sleep efficiency was significantly less in depression patients (mean 68.55%) as compared to nondepressive (mean 73.50%). The finding is inconsistent with Reynolds et al., who reported that sleep apnea patients with depression displayed an increase in REM latency and decreased sleep efficiency.[25]

The main presenting symptoms of patients with depression were snoring 44 (100%) and daytime sleepiness 40 (93.6%). All these symptoms were more common in patients with depression compared to nondepressive patients. All patients with depression, having OSA presents with snoring. Thus, all depressed patients with a suspected OSA significantly such as snoring and witness apnea should be referred to a sleep clinic for evaluation by nocturnal PSG.

In the present study, 93.6% of patients with depression had OSA indicating that OSA is highly prevalent comorbidity in depression. Furthermore, an important observation of our study was that severe and moderate OSA was significantly more in the depressed population compared to nondepressed population. Carney reported a higher prevalence of 66% in patients’ comorbid coronary heart disease.[32] Similarly, Hattori et al. reported the highest prevalence of 69% in a population of individuals with bipolar depression.[33] Deldin observed 53% of patients with OSA in patients with major depression disorder using specific depression severity.[34] Summers found 46.7% of OSA in patients with treatment-resistant depression.[35] Regarding the prevalence of OSA in patients with depression, our findings show a higher prevalence of OSA. The higher prevalence can be explained by the presence of other comorbid conditions such as diabetes mellitus which pose increased risk for OSA due to same pathophysiologic factors including obesity.[23] The other reason can be due measuring scale used, whereas we used a depression score on the HAM-D ≥7, which could explain the difference in prevalence estimations from earlier studies.

The findings suggest that OSA might be an important confounding factor for studies on depression. The reason is its presence is not routinely determined in either research studies. There is an immense need for additional population-based studies of OSA in community-dwelling individuals with depressive disorders to allow for better comparison to the general population. Community-based studies are required to assess the magnitude of the comorbidity and improving the management of these patients. The overall findings of our study indicate strong and immediate relationship between the depression and OSA. Most of the clinicians do not suspect this important comorbidity of depression in the beginning resulting in delayed diagnosis screening patients with depression for OSA and timely psychiatric intervention can go a long way in improving the quality of life of OSA. Future studies on prevalence need to be conducted to better determine the relationship between depression and OSA.

CONCLUSION

The findings of our study suggest that OSA is highly prevalent in depression and is largely unrecognized in the primary care setting. OSA may result in neuropsychiatric complications. Psychiatrists need to be alert to consider the possibility of OSA in high risk patients who present to them with cognitive and/or affective disorders. Therefore, regular screening of depression should be integrated into OSA management and can go a long way in improving the quality of life of these patients. Further community-based studies are required to assess the magnitude of the comorbidity and improving the management of these patients. Clinical suspicion needs to be reinforced by obtaining a history from the bed partner.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stradling JR, Davies RJ. Sleep 1: Obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome: Definitions, epidemiology, and natural history. Thorax. 2004;59:73–8. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.007161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young T, Peppard PE, Gottlieb DJ. Epidemiology of obstructive sleep apnea: A population health perspective. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:1217–39. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2109080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young T, Evans L, Finn L, Palta M. Estimation of the clinically diagnosed proportion of sleep apnea syndrome in middle-aged men and women. Sleep. 1997;20:705–6. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.9.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banno K, Kryger MH. Sleep apnea: Clinical investigations in humans. Sleep Med. 2007;8:400–26. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reaven GM, Lithell H, Landsberg L. Hypertension and associated metabolic abnormalities – The role of insulin resistance and the sympathoadrenal system. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:374–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602083340607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohayon MM. The effects of breathing-related sleep disorders on mood disturbances in the general population. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:1195–200. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balan S, Spivak B, Mester R, Leibovitz A, Habot B, Weizman A. Psychiatric and polysomnographic evaluation of sleep disturbances. J Affect Disord. 1998;49:27–30. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(97)00195-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Millman RP, Fogel BS, McNamara ME, Carlisle CC. Depression as a manifestation of obstructive sleep apnea: Reversal with nasal continuous positive airway pressure. J Clin Psychiatry. 1989;50:348–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pillar G, Lavie P. Psychiatric symptoms in sleep apnea syndrome: Effects of gender and respiratory disturbance index. Chest. 1998;114:697–703. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.3.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pochat MD, Ferber C, Lemoine P. Depressive symptomatology and sleep apnea syndrome. Encephale. 1993;19:601–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flemons WW, Tsai W. Quality of life consequences of sleep-disordered breathing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99:S750–6. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aikens JE, Mendelson WB. A matched comparison of MMPI responses in patients with primary snoring or obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 1999;22:355–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/22.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henke KG, Grady JJ, Kuna ST. Effect of nasal continuous positive airway pressure on neuropsychological function in sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:911–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.4.9910025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muñoz A, Mayoralas LR, Barbé F, Pericás J, Agusti AG. Long-term effects of CPAP on daytime functioning in patients with sleep apnoea syndrome. Eur Respir J. 2000;15:676–81. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.15d09.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramos Platón MJ, Espinar Sierra J. Changes in psychopathological symptoms in sleep apnea patients after treatment with nasal continuous positive airway pressure. Int J Neurosci. 1992;62:173–95. doi: 10.3109/00207459108999770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johns MW. Reliability and factor analysis of the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1992;15:376–81. doi: 10.1093/sleep/15.4.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. A Manual of Standardized Terminology, Techniques and Scoring System for Sleep Stages of Human Subjects. Los Angeles: UCLA Brain Information Service, Brain Research Institute; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 18.EEG arousals: Scoring rules and examples: A preliminary report from the Sleep disorders atlas task force of the American Sleep Disorders Association. Sleep. 1992;15:173–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: Recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. The Report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force. Sleep. 1999;22:667–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duman RS. Neural plasticity: Consequences of stress and actions of antidepressant treatment. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2004;6:157–69. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2004.6.2/rduman. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vgontzas AN, Pejovic S, Zoumakis E, Lin HM, Bentley CM, Bixler EO, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity in obese men with and without sleep apnea: Effects of continuous positive airway pressure therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4199–207. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sassi RB, Brambilla P, Nicoletti M, Mallinger AG, Frank E, Kupfer DJ, et al. White matter hyperintensities in bipolar and unipolar patients with relatively mild-to-moderate illness severity. J Affect Disord. 2003;77:237–45. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reynolds CF, 3rd, Kupfer DJ, McEachran AB, Taska LS, Sewitch DE, Coble PA. Depressive psychopathology in male sleep apneics. J Clin Psychiatry. 1984;45:287–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shoib S, Mushtaq R, Arif T, Hayat BM. Depression and diabetes. Common link and challenges of developing epidemic. J Psychiatry. 2015;18:231. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baran AS, Richert AC. Obstructive sleep apnea and depression. CNS Spectr. 2003;8:128–34. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900018356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Veasey SC. Serotonin agonists and antagonists in obstructive sleep apnea: Therapeutic potential. Am J Respir Med. 2003;2:21–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03256636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saunamäki T, Jehkonen M. Depression and anxiety in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: A review. Acta Neurol Scand. 2007;116:277–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2007.00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schröder CM, O’Hara R. Depression and Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2005;4:13. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-4-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aloia MS, Arnedt JT, Davis JD, Riggs RL, Byrd D. Neuropsychological sequelae of obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome: A critical review. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10:772–85. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704105134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carney RM, Howells WB, Freedland KE, Duntley SP, Stein PK, Rich MW, et al. Depression and obstructive sleep apnea in patients with coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:443–8. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000204632.91178.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hattori M, Kitajima T, Mekata T, Kanamori A, Imamura M, Sakakibara H, et al. Risk factors for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome screening in mood disorder patients. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;63:385–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2009.01956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deldin PJ, Phillips LK, Thomas RJ. A preliminary study of sleep-disordered breathing in major depressive disorder. Sleep Med. 2006;7:131–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Summers D, Lazowski L, Fitzpatrick M. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with treatment resistant depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;1:161–2. [Google Scholar]