Abstract

Background

Elevated depression and stress have been linked to greater levels of alcohol problems among young adults even after taking into account drinking level. The current study attempts to elucidate variables that might mediate the relation between symptoms of depression and stress and alcohol problems, including alcohol demand, future time orientation, and craving.

Methods

Participants were 393 undergraduates (60.8% female, 78.9% White/Caucasian) who reported at least 2 binge drinking episodes (4/5+ drinks for women/men, respectively) in the previous month. Participants completed self-report measures of stress and depression, alcohol demand, future time orientation, craving, and alcohol problems.

Results

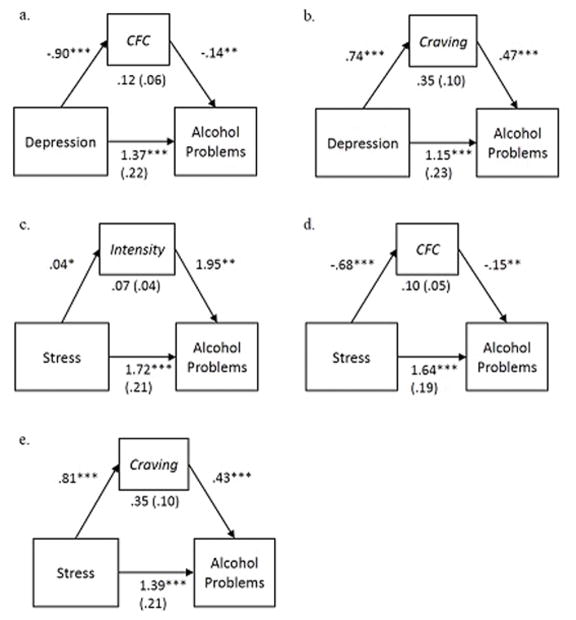

In separate mediation models that accounted for gender, race, and weekly alcohol consumption, future orientation and craving significantly mediated the relation between depressive symptoms and alcohol problems. Alcohol demand, future orientation, and craving significantly mediated the relation between stress symptoms and alcohol problems.

Conclusions

Heavy drinking young adults who experience stress or depression are likely to experience alcohol problems and this is due in part to elevations in craving and alcohol demand, and less sensitivity to future outcomes. Interventions targeting alcohol misuse in young adults with elevated levels of depression and stress should attempt to increase future orientation and decrease craving and alcohol reward value.

Keywords: alcohol demand, future orientation, alcohol craving, depressive symptoms, alcohol problems

Introduction

A significant percentage of college students experience symptoms of depression (33%) and stress (38%) (Beiter et al., 2015). Further, about 44% of college students report one or more binge-drinking episodes (4/5 standard drinks on one occasion for women/men) in the previous two weeks (Core Institute, 2012). Among college students, symptoms of stress, depression, and stress-related disorders have been linked to higher levels of alcohol-related problems (Martens et al., 2008; McCreary & Sadava, 2000; Pedrelli et al., 2016), in a manner that is at least partially independent of alcohol consumption level (Dennhardt & Murphy, 2011). Indeed, depressive and stress symptoms have shown inconsistent associations with alcohol consumption level and robust associations with alcohol problems (Merrill & Read, 2010; Park & Grant, 2005; Tripp et al., 2015). Moreover, young adults with depressive or stress symptoms are less likely to respond to standard brief alcohol interventions (Geisner et al., 2007; Merrill et al., 2014; Murphy et al., 2012).

Despite strong support for the general association between depressive and stress symptoms and alcohol-related problems, relatively little research has examined specific mechanisms that account for these relations. Identifying these mechanisms could lead to intervention approaches that more specifically target those mechanisms. There is some evidence that protective behavioral (harm reduction) strategies (Martens et al., 2008) and drinking to cope (Gonzalez et al., 2011; Kenney et al., 2015) are mechanisms that influence the relation between depressive symptoms and alcohol problems above and beyond consumption level. It is possible that dysregulated drinking patterns, characterized by elevated alcohol reward value, reduced valuation of the future, and heightened alcohol craving, may also account for the association between depressive and stress symptoms and alcohol-related problems.

Theoretical Mechanisms: Alcohol Demand, Future Orientation, and Craving

Alcohol Demand

Behavioral economic theory views addiction as a reinforcer pathology characterized by elevated drug/alcohol reward value and reduced valuation of the future that results in patterns of excessive alcohol and drug use that persist despite the presence of adverse health and social consequences (Bickel et al., 2014). Behavioral economic researchers use demand curve analyses to quantify the relative valuation of reinforcers such as alcohol and other drugs (Bujarski et al., 2012; Hursh & Silberberg, 2008; Murphy & MacKillop, 2006). Alcohol demand has shown consistent associations with risky patterns of drinking (Murphy & MacKillop, 2006; MacKillop & Murphy, 2007), alcohol-related consequences (Skidmore et al., 2014), Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) severity (MacKillop et al., 2010), and poor response to brief alcohol interventions (MacKillop & Murphy, 2007). Recent research has also made significant connections between depressive and stress symptoms and alcohol demand. Murphy and colleagues (2013) found that symptoms of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) contributed to elevated demand for alcohol above and beyond drinking level in a sample of heavy drinking college students. Specifically, symptoms of depression predicted elevated demand intensity (i.e. higher consumption when price is low or zero) and lower elasticity (i.e., less sensitivity to price). It is possible that the symptom relief alcohol provides for individuals with depressive or stress symptoms may lead them to drink more if the drinks are free and to be less affected by increases in drink prices. This pattern of dysregulated drinking may contribute to alcohol problems such as drinking more than originally planned and spending excessive amounts of time and money related to drinking. Indeed, Tripp and colleagues (2015) found that demand intensity and elasticity mediated the relation between PTSD symptoms and alcohol-related problems in a sample of college students.

Delay Discounting and Future Orientation

Delay discounting (DD), a behavioral economic index of future orientation and impulsivity, quantifies how rapidly a reward loses value as it is temporally delayed. DD has shown consistent significant associations with alcohol misuse (Amlung et al., 2016b), including alcohol consumption (Murphy & MacKillop, 2012) and AUD symptoms (MacKillop et al., 2010), as well as with other addictive behaviors (Amlung et al., 2016a; MacKillop et al., 2011) in non-college student populations. However, associations between DD and alcohol misuse in college student populations have been less consistent (Dennhardt & Murphy, 2011; Gonzalez et al., 2011; MacKillop et al., 2007a; Murphy et al., 2012).

Symptoms of depression or stress may lead individuals to focus more on present outcomes and to devalue the future. In a sample of adults with major depressive disorder (MDD), rate of discounting was associated with severity of hopelessness, and patients with MDD showed preference toward more immediate financial rewards (Pulcu et al., 2014). Further, Fields and colleagues (2015) suggested that individuals with elevated stress will tend to shift their mindset to the more immediate present, with the intention of risky behaviors such as alcohol or drug use to alleviate stress. Unfortunately, these findings do not appear consistent as some studies have failed to find associations between DD and depression (Dennhardt & Murphy, 2011; Gonzalez et al., 2011).

Consideration of Future Consequences (CFC; Strathman et al., 1994) also measures the degree to which an individual’s behavior is influenced by immediate versus distal outcomes, but relies on the subjective appraisal of the participant to ascertain this rather than hypothetical monetary choices and is empirically distinct from DD (Daugherty & Brase, 2010). Greater CFC has been associated with less alcohol and tobacco use (Strathman et al., 1994; Daugherty & Brase, 2010), more frequent exercise (Ouellette et al., 2005), and personality traits related to self-control (Strathman et al., 1994). Students who experience elevated depression or stress may overvalue immediate rewards such as alcohol because they provide relief from anxiety and anhedonia. The relative devaluation of future rewards may lead these students to neglect school, work, or other activities that have long-term outcomes in favor of a night out drinking, and to be less concerned with avoiding even next-day consequences such as hangovers. The present study will extend this research by including both DD and CFC as measures of time orientation, and will test the hypothesis that individuals experiencing symptoms of depression or stress will report lower future time orientation (greater delay discounting/lower CFC), which will in turn contribute to alcohol problems.

Craving

Craving has been defined as a strong subjective urge to use a substance (Kozlowski & Wilkinson, 1987) and has shown significant associations with level and severity of alcohol use (Rosenberg & Mazzola, 2007), typical weekly consumption, and alcohol-related problems in young adult samples (Tripp et al., 2015). Craving has also shown significant associations with delay discounting and alcohol demand (MacKillop et al., 2010). Alcohol cues result in parallel increases in craving and demand (MacKillop et al., 2007b), suggesting that craving and alcohol demand may reflect different facets of alcohol incentive salience, which is believed to be a core feature of addiction (Koob & Volkow, 2016). Further, Baker and colleagues (1987) suggested that aversive internal states or stimuli, such as depression or stress, also have the potential to elicit craving. A substantial amount of research has made strong connections between symptoms of depression, stress, and craving (Cooney et al., 1997). Most relevant to the current study, Tripp and colleagues (2015) found in a sample of non-treatment seeking college students that craving significantly mediated the relation between symptoms of PTSD and alcohol-related problems. That is, students with elevated symptoms of PTSD may experience greater alcohol craving, which in turn may lead to a manner of drinking that increases alcohol-related problems. Similarly, students experiencing elevated levels of depression or stress may have found alcohol to be previously helpful in managing their symptoms, thereby creating a pattern wherein their depressive and stress symptoms continue to elicit alcohol craving. This pattern may lead to alcohol-related problems, such as drinking on days or nights when they had planned not to in order to reduce craving and negative affect. Taken together, it seems that craving plays a substantial role in the initiation and maintenance of problematic use, especially in individuals with affective disorders.

Present Study: Alcohol Demand, Future Orientation, & Craving as Mediators

The present study attempted to identify alcohol incentive salience and time orientation variables that might mediate the relation between symptoms of depression, stress, and alcohol-related problems. We hypothesized that 1) depressive and stress symptoms would show significant positive associations with alcohol demand, craving, delay discounting, and alcohol-related problems, and negative associations with CFC; 2) alcohol craving, demand, and delay discounting would show significant positive associations with alcohol-related problems, and CFC would show significant negative associations with alcohol-related problems; and 3) symptoms of depression and stress would be associated with alcohol problems, and that this association would be partially mediated by alcohol demand, future orientation, and craving. Utilizing ten separate mediation models accounting for gender, race, and alcohol consumption, we were able to parse the variance contributed separately by depression and stress to alcohol-related problems, and the unique variance each of the five mediators contributed to these two established relations. Identifying mechanisms that account for the relation between depression or stress and alcohol-related problems could lead to improved interventions for college students with comorbid psychiatric and alcohol use disorders (e.g., Geisner et al., 2015; Merrill et al., 2014; Murphy et al., 2012).

Materials and Methods

Participants

The present study was a secondary analysis from a larger project that evaluated brief alcohol interventions. Participants were 393 undergraduate college students recruited from two large public universities in the southeastern United States (60.8% women; average age = 18.77, SD = 1.07, range = 18–25). Students were eligible to participate if they were at least 18 years old, had reported 2 or more binge drinking episodes in the past month (4/5 or more standard drinks for women/men, respectively, on one occasion), and were either a freshman or sophomore. Most participants were freshmen (n = 244, 62.1%), and were not involved in a fraternity or sorority (n = 267, 67.9%). The sample was 78.9% White, 10.9% Black, 1.8% Asian, 1.8% American Indian, and .5% Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. Additionally, 5.9% of the sample identified their ethnicity as Hispanic.

Procedure

Data were collected as part of the baseline assessment session of a larger alcohol intervention study with nontreatment-seeking college student heavy drinkers. All data were collected prior to any exposure to the study’s intervention elements. Participants were recruited from undergraduate courses and from campus-wide research participation solicitation emails. Study personnel screened students over the phone for eligibility, and then, if eligible, described the study in more detail and scheduled the baseline assessment and brief intervention session. Participants were compensated with extra course credit (for those in psychology courses) or cash payments ($25) for completing the two-hour assessment and brief intervention session. Participants completed self-report measures online on computers in the lab. The university’s Institutional Review Board approved all procedures.

Measures

Depression and Stress Symptoms

The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21; Antony, et al., 1998) is a 21-item measure that includes subscales assessing past week depression, anxiety, and stress. Because the anxiety subscale focuses primarily on physical symptoms and panic, we elected to focus on the depressive and stress symptom subscales given that these constructs have been associated with the mediators of interest in previous research (Fields et al., 2015; Pulcu et al., 2014;). Examples of items include: “I couldn’t seem to experience any positive feeling at all” (depressive) and “I found it difficult to relax” (stress). Participants are asked to rate how much each item applied to them from 0 (Did not apply to me at all) to 3 (Applied to me very much, or most of the time). Subscale items are separated, summed, and multiplied by 2 to generate subscale total scores. This measure distinguishes well between depression, anxiety (physical arousal), and stress (psychological tension), and has been shown to have good internal consistency and concurrent validity (Antony et al., 1998). Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) in the current sample was .89 for the depression subscale and .83 for the stress subscale.

Future Orientation

Two measures were used to assess the extent to which participants valued the future. A 60-item delay discounting (DD) task, based on the Monetary Choice Questionnaire (MCQ; Kirby et al., 1999), was administered. Participants were presented with 60 choices between two hypothetical amounts of money. Each item varies in amounts presented, and participants must choose between a smaller, immediate amount and a larger delayed amount (i.e. $50 today vs. $100 in 1 month). Each item contributes to the estimate of the participant’s discounting rate (k). Higher k values indicate steeper discounting, or greater preference for smaller immediate rewards. Delay discounting tasks such as the MCQ provide valid and reliable estimates of discounting rates (MacKillop et al., 2010a).

The Consideration of Future Consequences Scale (Strathman et al., 1994) is a 9-item measure assessing both the extent to which individuals consider future consequences or outcomes and how these potential outcomes influence their decision-making. Examples of items include: “I only act to satisfy immediate concerns, figuring the future will take care of itself” and “I think it is more important to perform a behavior with important distant consequences than a behavior with less-important immediate consequences.” Participants are asked how characteristic each item is for them from 1 (Extremely uncharacteristic) to 5 (Extremely characteristic). Certain items require recoding. All items are summed to generate a total score where higher scores indicate more future orientation. The CFC scale has demonstrated good test-retest reliability (Strathman et al., 1994), as well as construct and convergent validity (Murphy et al., 2012). The 9-item measure in the current sample showed acceptable internal consistency (α = .71).

Alcohol consumption

The Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins et al., 1985) asks participants to estimate the total number of standard drinks they consume each day during a typical week in the past month. This number is then summed to produce an estimate of drinks per week. This measure is highly correlated with other measures of alcohol consumption and has been widely used in the college drinking literature (Geisner et al., 2015; MacKillop & Murphy, 2007; Martens et al., 2008).

Alcohol-related consequences

The YAACQ, Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire, is a 49-item Yes/No self-report measure of alcohol-related consequences experienced over the past 6 months, and has good predictive validity and test-retest reliability (Read et al., 2006). Internal consistency in the current sample was α = .89 for the total score.

Alcohol craving

Craving was measured using the Penn Alcohol Craving Scale (PACS; Flannery et al., 1999), a 5-item, self-report measure assessing past-week frequency of alcohol craving, intensity of alcohol craving, duration of alcohol craving, and ability to resist alcohol. Examples of items include: “During the past week how often have you thought about drinking or about how good a drink would make you feel?” and “During the past week how difficult would it have been to resist taking a drink if you had known alcohol was in your house?” The measure uses a 0–6 Likert-type scale for each item. Higher scores indicate higher levels of past-week craving, and the items may be summed to create a total past-week craving score. Flannery and colleagues (1999) found excellent construct validity. Cronbach’s alpha in the current sample was .85.

Alcohol Demand

The Alcohol Purchase Task (APT; Murphy & MacKillop, 2006) was used to assess alcohol demand. The task instructs participants to imagine that they are with friends at a party from 9 p.m. until 1 a.m. They are also told that they will not consume alcohol before or after the party, and that the available drinks at the party are standard size domestic beers (12 oz.), wine (5 oz.), shots of hard liquor (1.5 oz.), and mixed drinks containing one shot of hard liquor. Participants are then asked how many drinks they would consume at each of the following 17 prices: $0 (free), $0.25, $0.50, $1.00, $1.50, $2.00, $2.50, $3.00, $4.00, $5.00, $6.00, $7.00, $8.00, $9.00, $10.00, $15.00, and $20.00. Demand intensity is the reported number of drinks consumed when price = $0 (free). Demand elasticity is a derived index of demand that represents the degree of sensitivity of consumption to increases in drink price.

Parent Income

Parent income was assessed by asking a single item: “What is your best estimate of your parents’ or legal guardians’ yearly income?” Response items ranged from 1 “Less than $25,000/year” to 6 “Greater than $150,000/year” with $25,000–$50,000 increments in between. A seventh response item recoded to zero (0) indicated “I don’t receive any financial support from my parents.”

Data Analysis

Prior to running any analyses, elasticity and delay discounting were derived using GraphPad Prism v. 5.04 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, www.graphpad.com). The macro for deriving elasticity is available online through the Institute for Behavioral Resources website (www.ibrinc.org). A modified, exponentiated version of Hursh and Silberberg’s (2008) exponential equation:

| (1) |

was used to generate demand elasticity values, where Q = quantity consumed, Q0 = consumption at $0.00 (derived demand intensity), k = range of alcohol consumption in logarithmic units, C = varying cost of each reinforcer, and α = elasticity (sensitivity to change in price). The equation when both sides are raised to the power of 10:

| (2) |

allows unaltered zeros to be included in the curve fit (Koffarnus et al., 2015). For the purpose of the current study, observed demand intensity was used as opposed to demand intensity derived (Q0) from the exponentiated equation. Based on procedures described in Koffarnus et al (2015), the constant k value for all analyses was set at 1.726, which was determined by subtracting the log10-transformed average consumption at the highest price ($20) from the log10-transformed average consumption at the lowest price ($0). This allows the parameters of Q0 and α to vary freely. Larger α values indicate greater elasticity (i.e. greater price sensitivity and lower alcohol reward value).

To ensure quality of the data, each participant’s data on the APT were examined for missing data and inconsistencies (i.e., when drinks purchased at a given price were greater than the preceding price, beginning with the second lowest price point). Participant data with more than one inconsistency as described were eliminated from elasticity calculations (N=9). Delay discounting rate was calculated from the Delay Discounting Task using Kirby and colleagues’ (1999) approach. Participants were assigned a k value, or hyperbolic temporal discounting function, which was estimated based on each participant’s responses across the task. The assigned k value reflects the highest relative consistency among discounting values, with larger k values reflecting greater discounting (lower future orientation).

Next, outliers in all variables were corrected using methods described by Tabachnick and Fidell (2012). Values exceeding 3.29 standard deviations above or below the mean were recoded to be one unit greater or lower than the greatest non-outlier value, respectively. Distributions were checked for skewness and kurtosis, and transformed using square root or log transformations as appropriate. The following variables were transformed: depressive symptoms, stress symptoms, typical drinks per week, demand intensity, demand elasticity, and delay discounting (k).

To examine hypotheses one and two, bivariate Pearson correlations were computed between the depression and stress subscales of the DASS, typical weekly drinking, demand variables (intensity & elasticity), CFC Scale total score, delay discounting estimates (k), Penn Alcohol-Craving Scale total score, YAACQ total score, and reported parent income. To examine hypothesis three, ten single mediation analyses were conducted using PROCESS Macro (Hayes, 2013) for SPSS to examine whether demand intensity and elasticity, delay discounting and consideration of future consequences, and craving mediated the relation between stress, depressive symptoms, and alcohol-related problems. To test the indirect association of depressive symptoms and stress on alcohol-related consequences through the path of craving, demand indices, and future orientation, a nonparametric bootstrapping method of 5,000 samples using a confidence interval of 95% was used. This approach makes no assumptions about the sampling distribution (Hayes, 2013). An indirect association is considered to be significant if the confidence interval does not include 0 (zero). Consistent with the recommendation of Hayes (2009), we investigated possible indirect, mediating effects on the relation between stress and depressive symptoms and alcohol problems even in the absence of significant bivariate relations. Each of the mediation models included covariates of gender, race, and typical drinks per week (Dennhardt & Murphy, 2011). Parent income was included as a covariate in a model if it showed significant associations with an identified mediator variable (i.e., intensity, delay discounting).

Results

Descriptive information on all variables in the study are presented in Table 1. As described above, demand elasticity (sensitivity to change in price) estimates were derived using a modified exponentiated exponential demand curve equation (Hursh & Silberberg, 2008; Koffarnus et al., 2015). This equation provided a good fit (R2= .98) to both the aggregated data (i.e. sample mean consumption), and to individual participant data (mean R2= .90). However, there is no accepted criterion for demand-curve fit adequacy, and R2 may not function well as a measure of curve fit with nonlinear models (Johnson & Bickel, 2008).

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics and Correlations among Variables

| N | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Depression† | 393 | 7.44 | 8.92 | -- | ||||||||

| 2. Stress† | 393 | 9.72 | 9.74 | .63** | -- | |||||||

| 3. Drinks Per Week† | 393 | 16.76 | 11.97 | −.01 | −.05 | -- | ||||||

| 4. Intensity† | 386 | 8.68 | 4.28 | .03 | .01 | .59** | -- | |||||

| 5. Elasticity† | 384 | .01 | .01 | .05 | .04 | −.22** | −.38** | -- | ||||

| 6. CFC | 393 | 30.40 | 6.53 | −.22** | −.15** | −.06 | −.12* | .08 | -- | |||

| 7. DD (k)† | 392 | .03 | .07 | .02 | .08 | .03 | .14** | −.13* | −.24** | -- | ||

| 8. Craving | 393 | 7.34 | 4.55 | .27** | .29** | .36** | .33** | −.21** | −.15** | .02 | -- | |

| 9. YAACQ | 393 | 13.06 | 7.89 | .34** | .38** | .40** | .33** | −.17** | −.19** | .04 | .45** | -- |

| 10. Parent Income | 392 | 3.73 | 1.68 | −.03 | −.02 | .02 | −.11* | −.01 | .06 | −.16** | −.001 | .03 |

Note. Means and Standard Deviations are prior to square root or log transformation.; DD (k) = Delay Discounting magnitude; CFC = Consideration of Future Consequences; YAACQ = Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire.

p< .01,

p< .05.

Variable Transformed.

Bivariate Pearson Correlations among Variables

Table 1 presents descriptive characteristics and correlations among study variables. Depressive and stress symptoms were highly correlated with each other, as well as with craving and alcohol-related problems, and were significantly negatively correlated with the CFC scale. Typical weekly consumption was not correlated with depressive or stress symptoms, though it did show significant associations in the expected direction with demand intensity and elasticity, craving, and alcohol-related problems. Finally, alcohol-related problems were significantly associated with depressive and stress symptoms, typical drinks per week, demand intensity and elasticity, CFC, and craving in the expected directions.

Demand, Future Orientation, and Craving as Mediators of the Relation between Depressive Symptoms and Alcohol-Related Problems

Demand intensity, elasticity, delay discounting, CFC, and craving were tested separately as mediators of the relation between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related problems using the PROCESS macro including the covariates noted above. As shown in Table 2, CFC and craving were significant single mediators. Approximately, 8.3% and 23.3% of the effect of depression on alcohol problems occurred indirectly through CFC and craving, respectively. The ratios of the indirect effects of CFC and craving to the direct effects were both less than 1, indicating that more of the total effect in the models was determined by the direct effect of depression on alcohol problems.

Table 2.

Summary of Single Mediators Analyses Predicting Alcohol-Related Problems

| N | a | b | c’ (SE) | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression† | |||||

|

| |||||

| Intensity† | 383 | .02 | 2.21*** | .05 (.04) | [−.0124, .1658] |

| Elasticity† | 382 | .01 | −2.63 | −.02 (.03) | [−.1235, .0168] |

| DD (k) † | 389 | .01 | .23 | .001 (.02) | [−.0204, .0470] |

| CFC | 391 | −.90*** | −.14** | .12 (.06) | [ .0322, .2738] |

| Craving | 391 | .74*** | .47*** | .35 (.10) | [.1816, .5776] |

|

| |||||

| Stress† | |||||

|

| |||||

| Intensity† | 383 | .04* | 1.95** | .07 (.04) | [.0123, .1980] |

| Elasticity† | 382 | .01 | −2.48* | −.01 (.03) | [−.0865, .0298] |

| DD (k) † | 389 | .04 | .03 | .001 (.02) | [−.0317, .0466] |

| CFC | 391 | −.68*** | −.15** | .10 (.05) | [.0248, .2316] |

| Craving | 391 | .81*** | .43*** | .35 (.10) | [.1874, .5822] |

Note. CFC = Consideration of Future Consequences; DD (k) = Delay Discounting magnitude; a = pathway from Independent Variable to Mediator; b = pathway from Mediator to Dependent Variable; c’ = indirect effect of the Independent Variable on the Dependent Variable through the Mediator.

p< .001,

p< .01,

p< .05,

bold text indicates significant indirect effect.

Variable Transformed.

Demand, Future Orientation, and Craving as Mediators of the Relation between Stress Symptoms and Alcohol-Related Problems

Demand intensity, elasticity, delay discounting, CFC, and craving were tested separately as mediators of the relation between stress symptoms and alcohol-related problems in models including the covariates noted above. Demand intensity, CFC, and craving were significant single mediators (Table 2). Approximately, 4.1%, 5.7%, and 20.1% of the effect of stress on alcohol problems occurred indirectly through demand intensity, CFC, and craving, respectively. The ratios of the indirect effects of demand intensity, CFC, and craving to the direct effects were all less than 1, indicating that more of the total effect in the models was determined by the direct effect of stress on alcohol problems.

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to examine behavioral economic variables and craving as potential mediators of the established relation between symptoms of depression, stress, and alcohol-related problems (Pedrelli et al., 2016). The overall pattern of results provides partial support for our hypotheses. Depressive and stress symptoms showed significant positive associations with craving and alcohol-related problems, and significant negative associations with CFC. Demand intensity (consumption when price = 0), demand elasticity (sensitivity to price), CFC, and craving also showed significant associations with alcohol-related problems in the expected directions. Of note, depression, stress, craving, and demand intensity each accounted for almost as much variance in alcohol problems as typical consumption level, further indicating their importance as assessment and treatment targets given the overall goal of reducing harm related to drinking. CFC and craving significantly mediated the relation between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related problems, and demand intensity, CFC, and craving significantly mediated the relation between stress symptoms and alcohol-related problems. Thus, heavy drinkers who are stressed or depressed may tend to drink in a manner that maximizes the immediate reinforcement associated with drinking despite the possibility of deleterious long-term outcomes (e.g., drinking the evening before a college class, in the absence of trusted companions, or in a situation that requires driving). These individuals may also crave alcohol more, which may lead them to drink when they had originally planned not to or to drink more than they had planned. Further, students who are stressed may also value alcohol more highly, which may impair their ability to regulate drinking as a function of (financial and behavioral) price. This might include excessive drinking when drinks are free/inexpensive such as at parties or college bars with low-price drinks.

Contrary to our hypotheses, demand elasticity (sensitivity to price) was not a significant mediator. This is inconsistent with previous research indicating that demand elasticity mediated the association between post-traumatic stress symptoms and alcohol problems (Tripp et al., 2015). This inconsistency may be related to sample characteristics. Tripp and colleagues’ (2015) sample had a wider age range with a higher average age (18–38 years, M=21.7) compared to the current study (18–25 years, M=18.77), perhaps leading to more experience with purchasing drinks, and more financial constraints such as housing/car payments. Thus, variability in drink price elasticity may be a more meaningful individual difference factor among the slightly older young adults included in the Tripp sample relative to the first and second year students included in the present sample. Consistent with previous research, however, elasticity was associated with delay discounting, craving, and alcohol problems in the expected direction (MacKillop et al., 2010), suggesting that it was a clinically relevant index of alcohol reward value in our sample.

Taken together, the current study provides further evidence that the relation between symptoms of depression or stress and alcohol-related problems is at least partially independent of alcohol consumption level (Dennhardt & Murphy, 2011; Martens et al., 2008; Tripp et al., 2015). Further, the current study, along with previous research showing strong associations between depressive and stress symptoms and alcohol-related problems but not with alcohol consumption, suggests that stress and depression may influence the manner of drinking more so than the quantity and frequency of drinking (Park & Grant, 2005). Martens and colleagues (2008) previously found that young adults with depressive symptoms were less likely to use protective behavioral strategies, and that this resulted in increased alcohol problems even after controlling for drinking level. The current results extend this line of research by identifying demand intensity, consideration of future consequences, and craving as additional mechanisms, with craving as the most robust mechanism.

The current results are also consistent with previous research showing that depressive and stress symptoms increase demand (Murphy et al., 2013; Tripp et al., 2015) and that demand is an indicator of risky alcohol use (MacKillop et al., 2010; MacKillop & Murphy, 2007; Murphy et al., 2013; Murphy & MacKillop, 2006; Skidmore et al., 2014). Interestingly, consistent with the results of Tripp et al., demand intensity was not related to depressive and stress symptoms in bivariate correlations, but was significantly related in the mediation models that controlled for typical weekly drinking and gender. It is likely that using alcohol to cope with or alleviate symptoms effectively increases the reward value of alcohol, leading to a stronger motivation to drink across situations and to continue to drink despite intoxication. This pattern of dysregulated drinking that may be less sensitive to contingencies may lead to alcohol-related problems in a manner that is partially independent of overall weekly drinking quantity.

In addition to elevated demand, low future orientation is the other primary risk factor in behavioral economic models of addiction (Bickel et al., 2014; Vuchinich and Heather, 2003). Although delay discounting is the most commonly used behavioral economic measure of future orientation and has shown robust relations with a variety of substance misuse indices (Bickel et al., 1999; Stein et al., 2016), its relation with other behavioral economic and alcohol-related variables in young adult alcohol misuse has been rather inconsistent (Dennhardt & Murphy, 2011; Gonzalez et al., 2011; MacKillop et al., 2007a; Murphy et al., 2012). Further, the current study found no significant associations between delay discounting and alcohol consumption or problems. Given that many college students have limited experiences with earning and saving money, it is possible that decisions about hypothetical monetary rewards are less representative of their actual valuation of delayed outcomes more generally.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that has examined consideration of future consequences (CFC) in the context of depressive and stress symptoms and alcohol-related problems in a sample of heavy drinking college students. As expected, individuals with elevated levels of depression or stress may be considering future consequences less, which may lead to a greater number of alcohol-related problems. Though CFC has been conceptualized as a relatively stable trait characteristic (Strathman et al., 1994), Murphy and colleagues (2012) found that a brief alcohol intervention paired with a behavioral economic supplement (Substance-Free Activity Session, or SFAS) increased future orientation and was especially helpful for students with depressive symptoms. Further, Episodic Future Thinking (EFT) tasks have been shown to reduce delay discounting and demand (Stein et al., 2016), and may also be beneficial for heavy drinking college students experiencing stress or depression. Therefore, despite its traditionally stable nature, time orientation may actually be relatively malleable in young adults and amenable to brief intervention approaches. The current study also contributes to the arguably small alcohol literature demonstrating the use and advantages of CFC.

Craving was the strongest mediator between depressive and stress symptoms and alcohol-related problems. The larger indirect effect may be due in part to the fact that some aspects of craving may be reflected in the alcohol-related problems included in the YAACQ (e.g., drinking when planned not to, drinking more than originally planned, difficulty limiting how much; Read et al., 2006). Although few studies have examined the role of craving in the relation between symptoms of depression or stress and alcohol-related problems (Tripp et al., 2015), a number of studies have shown that aversive internal states, such as depression or stress, have the potential to elicit craving (Baker et al., 1987; Cooney et al., 1997). Although this does not necessarily lead to increases in alcohol consumption, it may lead to dysregulated patterns of drinking that increase risk for alcohol-related problems. As noted below, these results suggest that heavy drinkers who experience symptoms of stress or depression may benefit from intervention elements that, in addition to targeting motivation to reduce drinking, include behavioral or pharmacological elements that reduce craving (Longabaugh & Morgenstern, 1999; O’Malley et al., 2002).

Limitations and Future Directions

Because this study was cross-sectional it is impossible to determine the direction of the relations, and in fact our behavioral economic model assumes the observed relations are bidirectional. Elevated demand and devaluation of future outcomes are likely predisposing risk factors for alcohol misuse that are influenced by biological and environmental factors, and regular heavy drinking will exacerbate these risk factors leading to increasing alcohol valuation, craving, and myopia over time (Bickel et al., 2014; Vuchinich & Heather, 2003). More intensive prospective research, for example using Ecological Momentary Assessment, to tease apart and systematically evaluate the sequence is justified. Additionally, retrospective, self-report measures were used and do not capture real-time variability in depressive and stress symptoms, demand, future orientation, craving, and alcohol use and related problems. Future research may also benefit from a more nuanced assessment of craving that considers the facets of relief, reward, and obsessive craving, as proposed by Verheul and colleagues (1999). Further, the time periods assessed across the different constructs are not consistent with each other (i.e., alcohol consumption and problems were assessed over the past month, depression and stress symptoms over the past week).

We also note that multiple testing of single mediators increases the likelihood of a Type I error. However, given the novel nature of the study, we elected to evaluate each mediator separately in order to evaluate their unique contributions to alcohol problems.. Finally, the sample was limited to heavy drinking college students from two large public universities (one urban and the other rural) and may not generalize to other heavy drinking populations or non-college student peer samples. However, this was consistent with our goal of understanding these phenomena in general, non-clinical samples of high-risk young adults given that previous research suggests that subclinical symptoms are associated with more problematic patterns of drinking that are less responsive to interventions (Dennhardt & Murphy, 2011; Merrill et al., 2014).

Future research should examine these relations over time using more fine-grained measurement approaches and other high risk populations. For example, it would be interesting to see if reductions in stress or depressive symptoms lead to reductions in demand and craving and increases in future orientation. Further, it is possible that individuals experiencing elevated levels of depression or stress are evaluating or interpreting their drinking-related behaviors and problems more negatively than someone who is not experiencing this same level of symptoms (Kenney et al., 2017). As such, this bias may affect how these individuals interpret the items on the alcohol-problems measure and how they report on their own drinking-related behavior and problems. Future research should tease out this potential reporting bias as it relates to symptoms of depression and stress and alcohol-related behaviors and problems. Alternatively, it is also possible that alcohol-related problems may be contributing to elevated levels of depression or stress. Future research should include experimental manipulations that directly target the mechanisms of interest and evaluate the impact on alcohol problems (MacKillop et al., 2010).

Summary and Clinical Implications

The results of this study replicate previous research suggesting that symptoms of depression and stress are significant predictors of alcohol-related problems among young adults (Pedrelli et al., 2016), and extend this research by identifying craving, alcohol demand, and future orientation as mediators of the relations between depression, stress, and alcohol problems. The primary clinical implication is that heavy drinking college students with depressive or stress symptoms may have greater alcohol reward value, less future orientation, and higher levels of craving, which may increase risk for experiencing alcohol-related problems such as impaired control while drinking, blackout drinking, and negative social or occupational consequences due to alcohol use. Brief alcohol interventions have been widely disseminated across college campuses (Mun et al., 2015), and the current results suggest that heavy drinkers with symptoms of depression or stress should be prioritized for these services. In addition to assessing alcohol use, problems, and depressive and stress symptoms, comprehensive assessments should measure alcohol demand, future orientation, and craving. This suggestion aligns well with the recommendations by Kwako and colleagues (2015) that substance abuse assessments target three neuro-clinical domains: executive function (i.e., response inhibition, planning, valuation of the future), incentive salience (i.e., motivation, conditioned reinforcement, reward), and negative emotionality (i.e., depressive and stress symptoms). Further, interventions targeting alcohol use and problems in heavy drinking college students may be improved by specifically including components from cue exposure (Rohsenow et al., 1995), Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT; Longabaugh & Morgenstern, 1999), or naltrexone pharmacotherapy that reduce craving (O’Malley et al., 2002), and behavioral economic intervention elements such as Episodic Future Thinking (EFT; Stein et al., 2016) and substance-free activity enhancement (Murphy et al., 2012) that increase future orientation and decrease alcohol reward value.

Figure 1.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Health grant R01AA020829 to James G. Murphy.

References

- Amlung M, Petker T, Jackson J, Balodis I, MacKillop J. Steep discounting of delayed monetary and food rewards in obesity: a meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine. 2016a;46(11):2423–2434. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716000866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amlung M, Vedelago L, Acker J, Balodis I, MacKillop J. Steep Delay Discounting and Addictive Behavior: A Meta - Analysis of Continuous Associations. Addiction. 2016b doi: 10.1111/add.13535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antony MM, Bieling PJ, Cox BJ, Enns MW, Swinson RP. Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10(2):176–181. [Google Scholar]

- Baker TJ, Morse E, Sherman JE. The motivation to use drugs: A psychobiological analysis of urges. In: Rivers C, editor. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation: Alcohol Use and Abuse. University of Nebraska Press; Lincoln, NE: 1987. pp. 257–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beiter R, Nash R, McCrady M, Rhoades D, Linscomb M, Clarahan M, Sammut S. The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2015;173:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Johnson MW, Koffarnus MN, MacKillop J, Murphy JG. The behavioral economics of substance use disorders: reinforcement pathologies and their repair. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2014;10:641–677. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Odum AL, Madden GJ. Impulsivity and cigarette smoking: delay discounting in current, never, and ex-smokers. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146(4):447–454. doi: 10.1007/pl00005490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bujarski S, MacKillop J, Ray LA. Understanding naltrexone mechanism of action and pharmacogenetics in Asian Americans via behavioral economics: A preliminary study. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology. 2012;20(3):181–190. doi: 10.1037/a0027379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooney NL, Litt MD, Morse PA, Bauer LO, Gaupp L. Alcohol cue reactivity, negative-mod reactivity, and relapse in treated alcoholic men. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106(2):243–250. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Core Institute. Report of 2010 national data: Core alcohol and drug survey long form. 2012 Retrieved from http://core.siu.edu/pdfs/report10.pdf.

- Daugherty JR, Brase GL. Taking time to be healthy: Predicting health behaviors with delay discounting and time perspective. Personality and Individual differences. 2010;48(2):202–207. [Google Scholar]

- Dennhardt AA, Murphy JG. Associations between depression, distress tolerance, delay discounting, and alcohol-related problems in European American and African American college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25(4):595–604. doi: 10.1037/a0025807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields SA, Ramos A, Reynolds BA. Delay discounting and health risk behaviors: the potential role of stress. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2015;5:101–105. [Google Scholar]

- Flannery BA, Volpicelli JR, Pettinati HM. Psychometric properties of the Penn Alcohol Craving Scale. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1999;23:1289–1295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisner IM, Neighbors C, Lee CM, Larimer ME. Evaluating personal alcohol feedback as a selective prevention for college students with depressed mood. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(12):2776–2787. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisner IM, Varvil-Weld L, Mittmann AJ, Mallett K, Turrisi R. Brief web-based intervention for college students with comorbid risky alcohol use and depressed mood: Does it work and for whom? Addictive Behaviors. 2015:4236–43. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez VM, Reynolds B, Skewes MC. Role of impulsivity in the relationship between depression and alcohol problems among emerging adult college drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2011;19(4):303–313. doi: 10.1037/a0022720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs. 2009;76:408–420. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hursh SR, Silberberg A. Economic demand and essential value. Psychological Review. 2008;115:186–198. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bickel WK. An algorithm for identifying nonsystematic delay-discounting data. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology. 2008;16(3):264. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.16.3.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney S, Jones RN, Barnett NP. Gender differences in the effect of depressive symptoms on prospective alcohol expectancies, coping motives, and alcohol outcomes in the first year of college. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2015;44(10):1884–1897. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0311-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney SR, Merrill JE, Barnett NP. Effects of depressive symptoms and coping motives on naturalistic trends in negative and positive alcohol-related consequences. Addictive behaviors. 2017;64:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Petry NM, Bickel WK. Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug-using controls. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1999;128(1):78–87. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.128.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffarnus MN, Franck CT, Stein JS, Bickel WK. A modified exponential behavioral economic demand model to better describe consumption data. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2015;23(6):504–512. doi: 10.1037/pha0000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurobiology of addiction: a neurocircuitry analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(8):760–773. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00104-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski LT, Wilkinson DA. Use and misuse of the concept of craving by alcohol, tobacco, and drug researchers. British Journal of Addiction. 1987;82:31–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb01430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwako LE, Momenan R, Litten RZ, Koob GF, Goldman D. Addictions neuroclinical assessment: A neuroscience-based framework for addictive disorders. Biological Psychiatry. 2015;80(3):179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Morgenstern J. Cognitive-behavioral coping-skills therapy for alcohol dependence current status and future directions. Alcohol Research & Health. 1999;23(2):78–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Menges DP, McGeary JE, Lisman SA. Effects of craving and DRD4 VNTR genotype on the relative value of alcohol: An initial human laboratory study. [Accessed 24 Oct. 2016];Behavioral and Brain Functions, [online] 2007b 3(11) doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-3-11. Availlable at: http://behavioralandbrainfunctions.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1744-9081-3-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Miranda R, Jr, Monti PM, Ray LA, Murphy JG, Rohsenow DJ, McGeary JE, Swift RM, Tidey JW, Gwaltney CJ. Alcohol demand, delayed reward discounting, and craving in relation to drinking and alcohol use disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119(1):106–114. doi: 10.1037/a0017513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Murphy JG. A behavioral economic measure of demand for alcohol predicts brief intervention outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;89(2):227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Amlung MT, Few LR, Ray LA, Sweet LH, Munafò MR. Delayed reward discounting and addictive behavior: a meta-analysis. Psychopharmacology. 2011;216(3):305–321. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2229-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Mattson RE, Anderson MacKillop EJ, Castelda BA, Donovick PJ. Multidimensional assessment of impulsivity in undergraduate hazardous drinkers and controls. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007a;68(6):785–789. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Neighbors C, Lewis MA, Lee CM, Oster-Aaland L, Larimer ME. The roles of negative affect and coping motives in the relationship between alcohol use and alcohol-related problems among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69(3):412–419. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreary DR, Sadava SW. Stress, alcohol use and alcohol-related problems: the influence of negative and positive affect in two cohorts of young adults. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61(3):466–474. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Read JP. Motivational pathways to unique types of alcohol consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24(4):705–711. doi: 10.1037/a0020135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Reid AE, Carey MP, Carey KB. Gender and depression moderate response to brief motivational intervention for alcohol misuse among college students. Journal of Consulting And Clinical Psychology. 2014;82(6):984–992. doi: 10.1037/a0037039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy C, MacKillop J. Living in the here and now: Interrelationships between impulsivity, mindfulness, and alcohol misuse. Psychopharmacology. 2012;219(2):527–536. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2573-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, Borsari B, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Martens MP. A randomized controlled trial of a behavioral economic supplement to brief motivational interventions for college drinking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:876–886. doi: 10.1037/a0028763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, MacKillop J. Relative reinforcing efficacy of alcohol among college student drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;14:219–227. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Yurasek AM, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, McDevitt-Murphy ME, MacKillop J, Martens MP. Symptoms of depression and PTSD are associated with elevated alcohol demand. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;127(1):129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mun E, de la Torre J, Atkins DC, White HR, Ray AE, Kim S, Jiao Y, Clarke N, Huo Y, Larimer ME, Huh D. Project INTEGRATE: An integrative study of brief alcohol interventions for college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2015;29(1):34–48. doi: 10.1037/adb0000047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley SS, Krishnan-Sarin S, Farren C, Sinha R, Kreek M. Naltrexone decreases craving and alcohol self-administration in alcohol-dependent subjects and activates the hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenocortical axis. Psychopharmacology. 2002;160(1):19–29. doi: 10.1007/s002130100919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouellette JA, Hessling R, Gibbons FX, Reis-Bergan M, Gerrard M. Using images to increase exercise behavior: Prototypes versus possible selves. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31(5):610–620. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Grant C. Determinants of positive and negative consequences of alcohol consumption in college students: Alcohol use, gender, and psychological characteristics. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30(4):755–765. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedrelli P, Shapero B, Archibald A, Dale C. Alcohol use and depression during adolescence and young adulthood: a summary and interpretation of mixed findings. Current Addiction Reports. 2016;3(1):91–97. doi: 10.1007/s40429-016-0084-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulcu E, Trotter PD, Thomas EJ, McFarquhar M, Juhász G, Sahakian BJ, Deakin JFW, Zahn R, Anderson IM, Elliott R. Temporal discounting in major depressive disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2014;44(09):1825–1834. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Colder CR. Development and preliminary validation of the young adult alcohol consequences questionnaire. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:169– 177. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow DJ, Monti PM, Abrams DB. Cue exposure treatment in alcohol dependence. In: Drummond, Tiffany, Glautier, Remington, editors. Addictive behavior: Cue exposure theory and practice. John Wiley and Sons; Oxford, England: 1995. pp. 169–196. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg H, Mazzola J. Relationships among self-report assessments of craving in binge-drinking university students. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(12):2811–2818. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skidmore JR, Murphy JG, Martens MP. Behavioral economic measures of alcohol reward value as problem severity indicators in college students. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2014;22:198–210. doi: 10.1037/a0036490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein JS, Wilson AG, Koffarnus MN, Daniel TO, Epstein LH, Bickel WK. Unstuck in time: episodic future thinking reduces delay discounting and cigarette smoking. Psychopharmacology. 2016;233(21–22):3771–3778. doi: 10.1007/s00213-016-4410-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathman A, Gleicher F, Boninger DS, Edwards CS. The consideration of future consequences: Weighing immediate and distant outcomes of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;66(4):742–752. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick B, Fidell L. Using multivariate statistics. 6. Allyn & Bacon; Boston, MA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tripp JC, Meshesha LZ, Teeters JB, Pickover AM, McDevitt-Murphy ME, Murphy JG. Alcohol craving and demand mediate the relation between posttraumatic stress symptoms and alcohol-related consequences. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2015;23(5):324–331. doi: 10.1037/pha0000040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheul R, van den Brink W, Geerlings P. A three-pathway psychobiological model of craving for alcohol. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 1999;34(2):197–222. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/34.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuchinich RE, Heather N. Introduction: Overview of behavioural economic perspectives on substance use and addiction. In: Vuchinich RE, Heather N, editors. Choice, Behavioral Economics and Addiction. Elsevier; Oxford, U.K: 2003. pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]