Chemical Injuries

Epidemiology

Chemical burns are an uncommon form of burn injury, accounting for 2.1% to 6.5% of all burn center admissions.1 According to the 2015 National Burn Repository report of the American Burn Association, chemical injuries represented 3.4% of patients admitted to participating hospitals over the 2004 to 2015 period. The mean hospital charge for patients with chemical burns was approximately $30,000, which was significantly lower than flame, scald, or electrical injuries. More than 13 million workers in the United States are at risk for dermal chemical exposures, particularly those employed in the agricultural and industrial manufacturing industries. Skin disorders are among the most frequently reported occupational illnesses, resulting in an estimated annual cost in the United States of more than $1 billion.2

Overall, chemical burns in the United States occur in roughly equal proportions at work (42.9%) and at home (45.9%), with most work-related exposures occurring in an industrial setting. The highest incidence occurred in the male population between 20 and 60 year old, representing most of the industrial work force. Similarly, a 10-year retrospective study of 690 chemical burn patients admitted to a large hospital in China reported the vast majority of chemical burns occurring in the 20- to 59-year age group (95%), which were most frequently related to work. The most common burn sites were the upper extremities (32%), followed by the head and neck (28%), and lower extremities (20%).3

A vast number of hazardous chemicals are capable of damaging tissue. The Hazardous Substances Emergency Events Surveillance database of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published an analysis of 57,975 chemical injuries over the 1999 to 2008 time period. The chemicals most frequently associated with injury were carbon monoxide (2364), ammonia (1153), chlorine (763), hydrochloric acid (326), and sulfuric acid (318).4 A 2004 study of military-related chemical burns treated at Brooke Army Medical Center reported 52.9% resulting from munitions (mostly white phosphorus), followed by acid exposures (9.1%), alkali exposure (6.5%), and other chemicals, such as phenol, fluorocarbon, and oven cleaner (6.2%).1

Beyond the initial tissue injury, sequelae of chemical burns can include wound infections, cellulitis, sepsis, and complications from scarring. Increasing age is associated with an increase in complications from chemical burns (mostly cellulitis and wound infections), with children under the age of 2 experiencing the lowest rate (2.5%). Complications in the 20- to 50-year age range plateau at 6.4% to 6.7%, which increases significantly with every decade greater than 50 to a maximum of 20.9% in patients older than 80.5 Sepsis is the most serious complication of chemical burns, which has an overall rate of around 0.6%.5 Mortality from chemical burns is fortunately low. In the 2014 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers' National Poison Data System, 151,796 dermal chemical exposures reported to the agency, and only 8 proved fatal.6

Chemical burns are infrequent in children, afflicting 0.9% of admitted pediatric burns at the Parkland Burn Center.7 It is also not a common form of child abuse, with only 1.4% of nonaccidental pediatric burns resulting from chemical contact.7 Another study at Children's Hospital Michigan grouped chemical burns in a miscellaneous category of 22% of admitted pediatric patients.8

The following article focuses on the dermal and ocular chemical burns most frequently encountered by plastic surgeons. Although oral ingestion is a more common route of toxic chemical exposure,6 the cause and management are beyond the scope of this article. According to the 2014 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers' National Poison Data System, the route of exposure is usually ingestion (83.7% of cases), followed in frequency by dermal (7.0%), inhalation/nasal (6.1%), and ocular (4.3%).

Emergency Management of Chemical Burns

A general approach to the patient with chemical burns involves scene safety, protecting health care workers from exposure, removing the patient from exposure, removing any necessary clothing and jewelry, and brushing off dry chemicals with a suitable instrument. Dry lime in particular should be brushed off before attempting irrigation, because it contains calcium oxide that reacts with water to form calcium hydroxide, a strong alkali. In contrast to thermal burns, many chemicals will continue to induce injury until removed, so immediate clearance of the offending agent is paramount in the intended treatment plan.

For most chemical burn injuries, copious irrigation with water or saline is the initial treatment. The exceptions to this are elemental metals and possibly phenols. Elemental metals produce exothermic reactions when combined with water, whereas aqueous irrigation of phenols may cause deeper infiltration into tissue. Gentle irrigation of chemical burns under low pressure is essential, because higher pressure irrigation can cause deeper infiltration of the chemical into the skin and place the patient and provider at risk for splatter injury. Moderately warm water is often advised. Irrigation should be started promptly, because started initial treatment in the field has been associated with reduced severity of burn injury and a shorter length of hospitalization.9 Irrigation should begin with the eyes and face, which prevents further inhalation or ingestion or toxin. Treatment should continue until the pH at the skin surface is neutral, which may take 2 hours or more in the case of alkali burns. Ideally, pH at the skin surface should be measured 10 to 15 minutes after discontinuation of irrigation. Litmus paper, if available, is ideal for this purpose. Neutralizing agents are generally not recommended given the potential for an exothermic reaction to occur between the 2 substances. The delay in obtaining the neutralizing agent will also allow for deeper tissue injury if water is readily available.

Ocular injuries should be similarly irrigated with water or saline or until neutral pH is achieved. Concentrated ammonia can induce severe anterior structural injury within 1 minute of exposure, whereas lye can cause deeper injury within 3 to 5 minutes.10

The initial management of phenol injuries is also somewhat controversial, with some arguing that irrigation may enhance dermal spread and penetration of the compound. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) has both hydrophilic and hydrophobic properties, which may be the ideal method of phenol decontamination. However, animal studies have not shown a significant difference in phenol plasma levels when burns were irrigated with PEG or water.11 Furthermore, because of the rarity of immediate phenol availability at the burn site, irrigation with water is more often advised.12

Alkali Burns

Anhydrous ammonia, calcium oxide/hydroxide (lime), and sodium or potassium hydroxide (lye) are common examples of alkalis used in industrial applications or the home. Lime, found in cement and plaster, is the most common cause of alkali burns. It is also known for producing burns of limited depth owing to the precipitation of calcium soaps in fat that limit further penetration. Ammonia and lye do not produce this effect and exhibit deeper and more severe tissue injury.

Anhydrous ammonia is a pungent, colorless gas that sees use in the production of fertilizer, synthetic textiles, and methamphetamine. It is the most common injury associated with illicit methamphetamine production,13 which has seen a resurgence in the last decade.14 Anhydrous ammonia is typically stored in refrigerated vessels, and so leakages may cause concomitant chemical and cold injury. Tissue destruction is related to the production of ammonium hydroxide, and more specifically to the concentration of hydroxyl ions. The ensuing damage is a product of liquefactive necrosis, which results in any degree of burn from superficial to full thickness. Anhydrous ammonia is known to have a particularly high affinity for mucous membranes. Mucosa-associated injuries, such as hemoptysis, pharyngitis, pulmonary edema, and bronchiectasis, have all been associated with anhydrous ammonia exposure.15 Inhalational exposure is extremely toxic. The report of a 2013 mass casualty in China involving anhydrous ammonia described 58 exposed employees, 10 of which died at the scene from inhalational injury, another 5 succumbed en route to the hospital, and the remainder suffered various degrees of pulmonary infection and respiratory failure.16

Anhydrous ammonia is soluble in water, and treatment therefore consists of immediate, copious aqueous irrigation. Because of the tendency of alkalis to linger in tissue for prolonged periods, repeat irrigation should be performed every 4 to 6 hours for the first 24 hours. Mechanical ventilation may be necessary for patients with significant facial or pharyngeal burns. Ocular exposure should be irrigated with water or saline until the conjunctival sac pH drops to less than 8.5.17

Hydrofluoric Acid

Organic and inorganic acids function by release of H+ and reaction with dermal proteins, which produces coagulative necrosis of the skin. Hydrofluoric acid (HF) is commonly used in the petroleum distillation industry to produce gasoline. It is also widely used in chemical and electronics manufacturing, glass etching, and smelting. Dilute solutions are found in household rust removers and metal cleaning products.18

HF displays a unique mechanism of action for an acid. More so than the free H+ released during dissociation, the free fluoride conjugate base ion is thought to be responsible for most tissue injury. Similar to strong alkalis, free H+ is scavenged from fatty acids, resulting in fat saponification and liquefactive necrosis. The free fluoride ion also affects calcium and magnesium cations in the serum, resulting in a systemic hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia. Hypokalemia can also result from inhibition of the sodium-potassium ATPase and Krebs cycle enzymes.18

Tissue damage is progressive, which can persist for days if untreated. Pain may be immediate or delayed depending on the magnitude of exposure, and affected skin will progress from a hardened, indurated appearance to a necrotic eschar. Systemic symptoms may include nausea, abdominal pain, and muscle fasciculation. In advanced cases, QT prolongation, hypotension, and ventricular arrhythmias can occur due to the profound electrolyte disturbances.18

In keeping with the initial treatment of most chemical burns, immediate aqueous irrigation is indicated. Acids generally require shorter irrigation times than alkalis, which in the case of HF is approximately 15 to 30 minutes. Blisters should be debrided to allow removal of acid trapped under the desquamated epithelium. In cases of more severe HF burns, detoxification of the fluoride ion is indicated with calcium gluconate. Calcium gluconate promotes formation of an insoluble calcium salt, which can be washed from the skin surface.

Calcium gluconate can be administered by intravenous or intraarterial injection, topically with 2.5% gel, or direct subcutaneous infiltration with a 5% to 10% solution. Topical administration, although effective for superficial exposures, is incapable of neutralizing deeper burns due to the impermeability of the calcium compound. Subcutaneous infiltration may be used for localized burns, which involves injection of 0.5 mL per cubic centimeter via a 27- to 30-gauge needle. HF burns of digits have been treated with direct infiltration, although a regional nerve block is required for adequate anesthesia during the procedure. Along with the risk of digital ischemia from arterial constriction, systemic administration of calcium gluconate is recommended for digital HF burns.19 Intravenous or intraarterial injection with 10% calcium gluconate generally requires intensive care unit admission, telemetry, and close monitoring of serum calcium levels. Calcium chloride may also be used, although central venous access is required. The magnitude of dermal exposure need not be extensive for systemic complications to develop. An HF leakage caused by an overturned tanker truck in China in 2014 was responsible for less than 5% total body surface area (TBSA) partial- and full-thickness burns in 4 people, all of whom were treated for inhalational injury and severe hypocalcemia.20

White Phosphorous

White phosphorous is a nonmetallic com pound that finds widespread use in munitions manufacturing, fireworks, fertilizers, and illicit methamphetamine production. It is present throughout the military arsenal as well.21 Phosphorous will autoignite with atmospheric oxygen at temperatures greater than 30°C, forming phosphorous pentoxide that then hydrates with exposure to air to form phosphoric acid.

Tissue injury by white phosphorous is caused by both thermal and chemical burns. Phosphoric reacts exothermically with skin, liberating heat and causing thermal burns. Both phosphorous pentoxide and phosphoric acid are capable of inducing chemical burns. Metabolic derangements due to calcium binding and hypocalemia have been reported from white phosphorous absorption, such as bradycardia, QT prolongation, and ST- and T-wave abnormalities.22 In these cases, calcium gluconate may be required to sustain plasma calcium levels.

Many have recommended the use of copper-containing solutions to neutralize white phosphorous.22,23 Copper reacts with phosphorous to form black cupric phosphide, which is more easily removed. Copper sulfate also reduces the oxidation potential of phosphorous and consequently can limit deeper tissue injury. However, laboratory experiments have demonstrated no benefit of copper solutions over saline alone,24 and is generally less available than water or saline. Wartime experience with white phosphorous burns suggests good efficacy with water alone.25

Phenol

Phenol (carbolic acid) is an aromatic hydrocarbon derived from coal tar. It has a characteristic strong, sweet odor that can be detected in burn injuries. Phenol has a notable history in surgery from the experiments by Joseph Lister in 1867 for its aseptic properties and ability to disinfect surgical instruments. Phenol is used in the production of a variety of industrial products, such as explosives, fertilizers, paints, rubber, resins, and textiles. Phenol is also used in various commercial soaps, sprays, and ointments as a germicidal antiseptic.12 Dilute phenol solutions are also commonly used by plastic surgeons as a chemical facial peel, which are usually admixed with water, soap, and croton oil. The solution is applied topically to produce a controlled partial-thickness burn. Upon healing, the dermal collagen reorganization improves the appearance of facial rhytids, actinic keratosis, and irregular pigmentation.

Concentrated phenol and its derivatives are highly reactive with skin, which induce tissue injury by protein denaturation and coagulative necrosis. Following initial contact, coagulative necrosis of the papillary dermis may serve to delay deeper tissue penetration, highlighting the importance of immediate irrigation. Dermal phenol exposure can cause any degree of burn injury from irritation to dermatitis to full-thickness burns. Abnormal, dark pigmentation may also result from dilute phenol exposure. Because of its anesthetic properties, extensive tissue damage can occur before pain is recognized.

Phenol is poorly soluble in water, and there is some concern that inadequate irrigation will merely spread the chemical over uninjured areas of skin, resulting in a larger burn area and potentially greater systemic absorption. PEG serves as a hydrophobic solvent, which can more readily dissolve phenol. PEG is usually available in hospital pharmacies and is probably the preferred antidote for phenol burns, although this is somewhat controversial. Although the mechanism is understood, clinical studies of phenol neutralization with PEG are lacking. In a 1978 study of swine acutely exposed to phenol, plasma phenol levels were not significantly different in swine decontaminated with PEG or water.11 Thus, as with most chemical burns, the recommended initial treatment is copious irrigation with water until PEG is available. Irrigation should continue with either PEG or water because dilute phenol solutions are more easily absorbed through the skin. Water irrigation should not be delayed while awaiting PEG availability. In a case series of 4 patients with extensive phenol burns in China, both water and PEG were used.12

Systemic toxicity from phenol poisoning can also result, with the cardiovascular and central nervous systems primarily affected. Neurologic symptoms include mental status changes, lethargy, seizures, or coma. Cardiovascular toxicity may present as bradycardia or tachycardia. Hypotension, hypothermia, and metabolic acidosis can occur with severe exposure. Treatment of systemic toxicity is largely supportive with fluid resuscitation and vasopressors as needed.

Ocular Injuries

Chemical burns to the eye and eyelid are a frequent cause of emergency room visits, totaling approximately 2 million cases per year.26 Approximately 15% to 20% of facial burns involve the eye,27 and ocular injury stands as the second leading cause of visual impairment in the United States after cataracts.26 Similar to dermal chemical injuries, alkali exposures are more common and generally cause deeper and more serious tissue damage than acid. Common offending agents in the household include automobile batteries, pool cleaners, detergents, ammonia, bleach, and drain cleaners.28 Patients may present with decreased vision, eye pain, blepharospasm, conjunctivitis, and photophobia. In severe cases of alkali burns, the globe may appear white due to ischemia of the conjunctiva and scleral blood vessels.

Alkali injuries such as lime and ammonia penetrate readily into eye, injuring stroma and endothelium as well as intraocular structures such as the iris, lens, and ciliary body. Acid injuries are generally less severe because the immediate precipitation of epithelial proteins confers a protective barrier to intraocular penetration.28 Periocular injuries are common, where the depth of injury often correlates with scar formation. Debridement of devitalized periocular tissue is important to protect the ocular surface from exposure keratopathy and corneal ulceration. Profound dermal injury may result in cicatricial ectropion, which often requires tarsorrhaphy or excision and full-thickness skin grafting.26

Ocular burns are categorized into 4 grades, with grade IV representing the most severe. Grade I burns are associated with hyperemia, conjunctival ecchymosis, and defects in the corneal epithelium. Grade II burns include haziness in the cornea. Grade III burns are associated with deeper penetration into the cornea and present with mydriasis, gray discoloration of the iris, early cataract formation, and ischemia in less than half of the limbus. Grade IV burns appear similar to grade III but with ischemia involving more than half of the limbus. They are also associated with necrosis of the bulbar and tarsal conjunctiva.29

Immediate irrigation with water is the initial therapy for ocular injuries, beginning at the scene and continuing to the emergency department. Animal studies have consistently demonstrated better outcomes when the eye is rinsed early and thoroughly after chemical exposure,30,31 relating to the progressive neutralization of pH with water volume. Prolonged irrigation is best achieved using intravenous tubing and a polymethylmethacrylate (Morgan) lens, although when no such device is available, it is important to keep the eyelids retracted to assure adequate irrigation of the conjunctiva and cornea.

Electrical Injuries

Clinical Background

As one of the most devastating and debilitating injuries cared for in burn centers, electrical injuries comprise 4% of all reported causes. Burn surgeons must keep in mind that electrical injuries are unique because they may cause a flash and external burn but also internal burns from the current, which heats up bone and burns muscle as it invests bone. Electrical injuries occur more frequently in adults than children because most result from occupational exposure. Patients who have high-voltage electrical injuries, defined as greater than 1000 V, are at elevated risk of spine fracture injury due to tetany and require complete immobilization until vertebral injury is ruled out. Providers must also evaluate patients with high-voltage injuries for cardiac damage. Direct muscle injury from current flow may cause gross myoglobinuria, requiring more aggressive fluid resuscitation.32 Patients with gross myoglobinuria often require fasciotomy of affected limbs, and a severe electrical injury often requires monitoring in the intensive care unit. Bone has the highest conductance, and electricity flows along the skeleton, causing significant muscle necrosis adjacent to the bone. TBSA is not necessarily associated with prognosis, and TBSA does not quantify damage to deep tissues in electrical injuries. Entrance and exit wound should be assessed when evaluating which extremities should be closely monitored for compartment syndrome.

Thermal injuries occur as electricity can generate temperatures greater than 100°C. Electroporation occurs as electrical force drives water into lipid membrane, causing cell rupture. Tissue resistance in decreasing order includes bone, fat, tendon, skin, muscle, vessel, nerve. Bone heats to a high temperature and burns surrounding structures, such as muscle, which is the reason muscle swelling and compartment syndrome are common in high-voltage electrical injuries.

Alternating current causes tetanic muscle contraction and the “no let-go” phenomenon. This phenomenon occurs because of simultaneous contraction of (stronger) forearm flexors and (weaker) forearm extensors. Current flow through tissue can cause burns at entrance/exit wounds and hidden injury to deep tissues. Current will preferentially travel along low-resistance pathways. Current will pass through soft tissue, contact high-resistance bone, and travel along bone until it exits to the ground. Vascular injury to nutrient arteries and damage to intima and media can result in thrombosis.

Electrical exposure can cause significant injuries to other organ systems besides the skin and musculoskeletal system. From a cardiac standpoint, arrhythmias are common at the scene (any voltage) or in the hospital (high voltage ≥1000). Heart rhythm should be monitored continuously for at least 24 hours if cardiac injury is suspected at the scene or if a high-voltage injury has occurred. Ventricular fibrillation and asystole are the most common, and Advanced Cardiac Life Support should be instituted immediately. Coronary artery spasm and myocardial injury and infarction have also been described. A normal cardiac rhythm on admission, however, means dysrhythmia is unlikely, and thus, 24-hour monitoring is not needed.33 In addition, injury to solid organs, acute bowel perforation, and gallstones after myoglobinuria have been described and should be monitored. Myoglobinuria occurs due to the disruption of muscle cells. Myoglobinuria from other causes requires increased fluid administration; however, burn resuscitation usually provides adequate fluid. Cataracts are also a long-term adverse effect of electrical injury, necessitating an ophthalmology evaluation and follow-up.

When taking the patient to the operating room for debridement and grafting of electrical injuries, the physician should perform serial debridements and allow the tissue to completely declare itself. These injuries will often evolve with progressive muscle necrosis over time, thus early grafting (within the first week) often fails to fully close the burn wound. These injuries have similarities to crush injuries, and thus, multiple trips to the operating room for debridement should not be viewed as a failure.

Pathophysiology

Electrical burns have the potential for 3 types of injury: (1) True electrical injury by current flow; (2) Arc injury from the electrical arc as it passes from the source to an object; and (3) Flame injury from ignition of clothing or surroundings. Electricity arcs occur at temperatures up to 4000°C and can create a slash injury as seen in electricians. Clinicians must keep in mind that the force of the electrical injury may throw the patient, causing additional trauma, ruptured eardrums, and internal organ contusion. Electricity flows through the tissue of greatest resistance, which in humans is bone. In general, the severity of the injury is inversely proportional to the cross-sectional area of the body part with the most severe regions seen in the wrist and ankle and decreasing proximally. Deeper tissues and regions between 2 bones (tibia and fibula; ulna and radius) also retain heat to a greater degree. Macroscopic and microscopic vascular injury can occur immediately and is often not reversible.34

Admission Criteria

All patients with high-voltage injury, electrocardiograph (ECG) changes, loss of consciousness, or concern for extremity compartment syndrome are standard indications for admission. Patients, however, with low-voltage injuries and normal ECG can be discharged home if no other indication is present.35 Although the duration of monitoring after admission is not known, most reports recommend 24 hours after admission if there are no ECG abnormalities.

Evaluation of the Extremity

Given that the entrance wound of electrical injuries often involves the upper or lower extremity and the devastating nature of compartment syndrome, surgeons must be extremely vigilant when evaluating electrical injury patients. Additional evaluation must be performed in patients who present with loss of consciousness or who were intubated in the field. Unlike compartment syndrome from flame burns where the constricting tissue is the burn eschar, the constricting tissue in electrical injury patients is the fascia as the muscle swells after being heated up by the current running through the bone. Signs of compartment syndrome from electrical injury are similar to other causes of compartment syndrome with pain on passive extension as the most telling sign. Additional signs include pain out of proportion to examination, paresthesia, and pulselessness. The last 2, however, occur in very late stages of the process. In patients who are not able to participate in an examination, any mechanism of concern warrants consultation by a plastic or hand surgeon and likely measurement of compartment pressure. Any absolute pressure greater than 30 or diastolic pressure–compartment pressure less than 30 indicates compartment syndrome. Fasciotomies should be performed in the presence of compartment syndrome, making sure to decompress all compartments affected.

Fasciotomy of the Upper Extremity

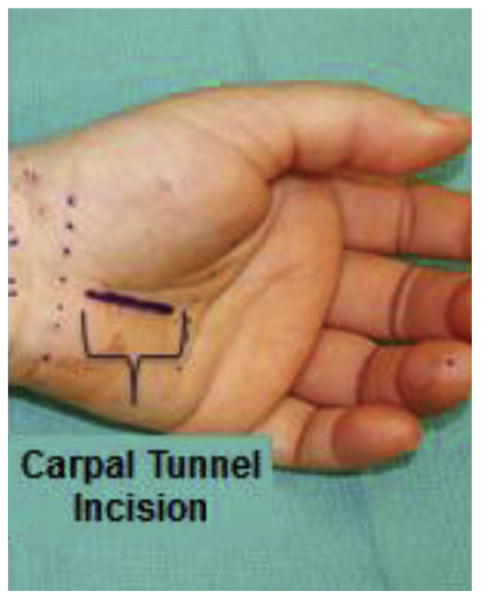

There are 4 compartments in the forearm (superficial volar, deep volar, dorsal, mobile wad) and 10 compartments in the hand (4 dorsal interossei, 3 palmar interossei, hypothenar, thenar, and adductor pollicis). When marking the incisions, the surgeon must incorporate the knowledge of this anatomy. In the hand, all compartments can be accessed through 4 separate incisions: 2 incisions along the second and fourth dorsal meta-carpal, and 1 each on glabrous-nonglabrous junction of the thenar and hypothenar eminences (Fig. 1). In addition, a carpal tunnel release is often performed at the same time using a standard carpal tunnel incision that is 2 to 3 cm along the intersection of a line parallel to ulnar side of thumb (Kaplan cardinal line) and the radial part of fourth ray (Fig. 2). Classic descriptions of a forearm fasciotomy include a lazy S starting 1 cm proximal and 2 cm lateral to the medial epicondyle and carried out obliquely across the antecubital fossa toward the mobile wad and then curved distally and ulnarly reaching the midline at the forearm at the junction of the mid and distal one-third of the forearm and then continuing distally just ulnar to the palmaris tendon and then distally incorporating Guyon canal and the carpal tunnel. Volar release must include the pronator quadratus and deep flexor compartments as well.36 Often a separate ulnar escharotomy is needed for electrical injuries with concomitant burns (Fig. 3). Recent studies, however, have shown that a smaller incision (Fig. 4) along the lazy S may be sufficient to release the volar compartments without as much morbidity or wound-healing complications. The dorsal compartment is released with an incision between the lateral epicondyle and ulnar styloid. To allow for improved postre-lease healing, the authors usually create a “Roman sandal” constructed of vessel loops, which apply gentle traction to the wound edges to prevent skin recoil and minimize gaping. With regards to digits, there is no true fascial compartment, and thus a fasciotomy is not indicated. However, if eschar is circumferential around the digits, the authors recommend radial and ulnar release of the eschar more dorsal to the course of the neuro-vascular bundle.

Fig. 1.

Hand fasciotomy. (top) Schematic of markings for incisions for volar and dorsal incisions needed to release the compartments of the hand including the carpal tunnel. (bottom) Incisions made for release of the hand compartments, including a carpal tunnel release.

Fig. 2.

Markings for where to place incision for carpal tunnel release.

Fig. 3.

Open fasciotomy incisions of the arm. (top) Volar incisions releasing the proximal arm and volar forearm. (bottom) Dorsal incisions releasing the forearm and hand.

Fig. 4.

Minimally invasive incision markings for forearm compartment release. (top) Minimally invasive volar forearm incision to release the volar forearm compartments. (bottom) Minimally invasive incision marked dorsally for dorsal forearm compartment release.

Fasciotomy of the Lower Extremity

Diagnosis of compartment syndrome in the lower extremity is similar to diagnosis in the upper extremity. There are 4 compartments to the lower extremity: Superficial posterior, deep posterior, lateral, anterior. These compartments can be released through a double-incision fasciotomy with one incision centered between the fibular shaft and the crest of the tibia overlying the intramuscular septum between the anterior and lateral compartments. After the skin is incised, subcutaneous flaps are developed medially and laterally to expose the fascia of the intramuscular (IM) septum and fascia of the anterior and lateral compartments. Care must be taken to avoid injury to the peroneal nerves. The medial incision is placed 2 cm medial to the tibia between the anterior IM septum and tibial crest, taking care to avoid the saphenous vein and nerve. The superficial posterior compartment is decompressed by incising the gastrocnemius fascia, and the deep posterior compartment is decompressed by dividing the attachments of the soleus to the tibia, providing access to the posterior tibialis muscle.

Cardiac Evaluation

Indications for cardiac monitoring include ECG abnormality or evidence of ischemia, documented dysrhythmia before or after emergency room admission, loss of consciousness, and cardiopul-monary resuscitation in the field. Most studies recommend monitoring for 24 to 48 hours.35 The most common arrhythmias include nonspecific ST-T changes and atrial fibrillation. Myocardial damage and dysrhythmias are seen soon after injury, and unfortunately, troponin is not always a useful diagnostic of myocardial injury.37,38

Renal Evaluation

Despite the often noticeable myoglobinuria in patients with severe electrical injuries, the incidence of renal failure is small. Treatment is similar to other burn patients wherein appropriate resuscitation is crucial. Historically, patients were given mannitol and sodium bicarbonate in attempts to alkalinize the urine; however, studies have failed to demonstrate improved outcomes over standard resuscitation protocols. In general, electrical injury patients with darker-colored urine should receive Lactated Ringers solution to maintain urine output double the goal rate or approximately 100 mL/h. If the urine fails to improve, the clinician should evaluate for ongoing ischemia and muscle necrosis. Once the myoglobinuria resolves, fluids should be titrated back to a urine output goal of 30 to 50 mL/h.

Secondary Complications of Electrical Injury

Cataract formation is a common complication after electrical injury and has been published to occur in 5% to 20% of electrical injury patients.39 Early ophthalmology consultation as well as post-discharge follow-up is crucial for these patients because cataracts can arise in a delayed fashion.40 Central and peripheral neurologic complications are also common and range from paralysis to Guillain-Barré, paresis, and transverse myelitis. Central manifestations include cognitive and emotional changes.41,42

Acute Burn Treatment of Electrical Injury

After stabilization and resuscitation of the electrical injury patient, general burn care principles are applied to this patient population. In general, early debridement is still a central tenant of electrical burn care. For electrical injury, however, the deeper injury to the muscle may not be evident in early debridements. Thus, serial debridements with temporary wound vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) or dressing changes help allow time for the wound to completely declare itself before auto-graft. The surgeon can also use a temporary coverage with human allograft as a “test” to see if the wound bed is ready. If the allograft has good take, then likely the wound is ready for auto-graft. Thickness of the autograft should be dictated by the location of the injury with thicker split-thickness grafts used on the hands and face (0.014- to 0.018-inch thickness).

Reconstructive Challenges of Electrical Injury

Burn injuriestothe oral cavityare themost common type of serious electrical burns in young children often due to them chewing on an electrical cord, causing injury to the oral commissure. Care includes conservative management with occupational therapy and parental monitoring for bleeding fromthe labialartery.Subsequent reconstruction of the oral commissure is best addressed with V-Y or ventral tongue flaps.43,44 Peripheral nerve injury is seen commonly after electrical injury. If the patient has symptomsofcompressive peripheral neuropathy, a decompressive corrective surgery should be performed.45 Late consequences of electrical injury, similar to severe thermal burns, include joint contractures and heterotopic ossification (HO). HO may be seen more commonlyin electrical injury patients duetothe large amountoftissuedamage and the known correlation between severity of injury and HO.46 HO is most commonly seen when the upper extremity is involved, and most frequently is seen in the elbow.47 Currently, no early diagnostic or prophylactic strategies for this difficult complication exist.48

Radiation Burns

Clinical Background

Ever since the world was introduced to the power of nuclear weapons in 1945 with the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the world has been forever changed. The power of nuclear weapons was seen firsthand, and the impact of radiation and its impact for injury began to be appreciated. From the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, many important lessons were learned. One was that proximity to the detonation directly impacted mortality with 86% fatality rates at 0.6 miles from ground zero, and it decreased to 27% at 0.6 to 1.6 miles, and then 2% for those 1.6 to 3.1 miles away. In addition, the mortality was highest during the first 20 days. Of the 122,338 fatalities at Hiroshima, 68,000 occurred within that timeframe. Of the 197,743 survivors, 79,130 were injured, and the remaining 118,613 were uninjured. It is estimated that those injured at Hiroshima contained 90% with burns, 83% with traumatic injuries, and 37% with radiation injuries.49,50

The devastation of these weapons is massive and has some understood properties. The explosion generates high-speed winds that can travel at dramatic speeds. A 20-kiloton nuclear device generates 180 mph winds 0.8 miles from the epicenter. These winds occur with a direct pressure and indirect wind drag, and the pressure wave can destroy windows and buildings and injure parts of the body that are sensitive to pressure changes, such as the lungs and ears. It results in ruptured tympanic membranes, pulmonary contusions, pneumothoraces, and hemothoraces. A fireball that results from the explosion results in thermal injuries and also sends radioactive material into the air. Near ground zero, the thermal injuries are nearly 100% fatal due to incineration from the high temperatures. Radiation is dispersed in a linear fashion and results in burns that vary in severity depending on the distance from ground zero and the time of exposure. Radiation is also dispersed into the air and follows wind patterns, ultimately settling to the ground.49,50

Radioactive material results in both acute injury from immediate exposure and more prolonged injury from delayed exposure to radioactive fallout or contamination. From what is known from a 10-kiloton nuclear bomb detonation, people at a distance 0.7 miles from ground zero absorb 4.5 Gy (1 Gy, Gy equals 1 Sievert, Sv). At 60 days, the radiation dose lethal dose, 50% is 3.5 Sv; with aggressive medical care, this dose might be doubled to nearly 7 Sv. To put this in context, radiation exposure from a diagnostic computed tomographic scan of the chest or abdomen is 5 mSv, and the average annual background absorbed radiation dose is 3.6 mSv. Radiation is known to impact several organ systems and result in several syndromes based on increasing exposure doses. These syndromes include the hematologic syndrome (1–8 Sv exposure), gastrointestinal syndrome (8–30 Sv exposure), and cardiovascular/neurologic systems (>30 Sv exposure), with the latter 2 being nonsurvivable.49–51

After initial evaluation and decontamination by removing clothing and washing radiation material from the skin, a useful way to estimate exposure is by determining the time to emesis. Patients that do not experience emesis within 4 hours of exposure are unlikely to have severe clinical effects. Emesis within 2 hours suggests a dose of at least 3 Sv, and within 1 hour is at least 4 Sv. The hematologic system follows a similar dose-dependent temporal pattern for predicting radiation exposure, mortality, and treatment. These values have been determined based on the Armed Forces Radiobiology Research Institute's Bio-dosimetry Assessment Tool and can be downloaded from www.afrri.usuhs.mil.

The combination of radiation exposure to burn wounds has the potential to increase mortality compared with traditional burns. Early closure of wounds before radiation depletes circulating lymphocytes may be needed for wound healing (which occurs within 48 hours). Also, in radiation injuries combined with burn or trauma, laboratory lymphocyte counts may be unreliable.49–52 A significant difference between burn/traumatic injuries and radiation injuriesisthat burn/traumatic injuries can result in higher mortality when not treated within hours.

Decontamination and triage are vital to maximize the number of survivors. Initial decontamination requires removal of clothing and washing wounds with water. Irrigation fluid should be collected to prevent radiation spread into the water supply. Work by many professional organizations, including the American Burn Association, has focused on nationwide triage for disasters and will be vital to save as many lives as possible. Partnerships between emergency medical services, emergency medicine, trauma surgeons, burn surgeons, medical oncology, radiation oncology, and others will be vital because their injuries will require multidisciplinary care in ways not experienced before in modern medicine. It is quite possible that expectant or comfort care could be offered to more patients than typically seen in civilian hospitals, because of resource availability after the disaster.

Iatrogenic Radiation Burns

Ionizing radiation therapy has become an important component in the treatment of many different types of cancer. It has important therapeutic treatments that include goals of curing a patient of a given malignancy as well as palliative goals, to improve their quality of life. Although there is considerable adjustment to the technique of administration, the total dose, volume, and individual variations, these are the variables considered to have the largest impact on skin changes from radiation.53 It is also thought that in radiation-treated areas, around 85% of patients will have a moderate to severe skin reaction that can lead to blistering, ulceration, and erosion (Fig. 5).54 When severe, it can interrupt radiation therapy, which can also have implications for their oncologic treatment and is known as acute radiation dermatitis. The other common problem patients can experience occurs months to years after treatment, whereby the skin develops progressive, permanent, irreversible changes from chronic radiation dermatitis.

Fig. 5.

Radiation burn to the arm over time as it was allowed to heal secondarily.

Acute radiation dermatitis commonly included changes that occur within 90 days of radiation exposure.55 There is a grading system developed by the National Cancer Institute to classify radiation dermatitis and includes 4 stages; this staging system is helpful because the clinical treatments are tied to the stage of injury. Grade 1 injuries have faint erythema or dry desquamation. Grade 2 has moderate to brisk erythema with patchy desquamation confined to creases and skin folds. Grade 3 injury contains moist desquamation outside folds with pitting edema, and bleeding from minor trauma. Grade 4 has full-thickness skin necrosis or ulceration with spontaneous bleeding. In terms of treatment, they vary based on the degree of injury. Grade 1 injuries are treated with hydrophilic moisturizers, and pruritus and irritation are treated with low-dose steroids. Grades 2 and 3 injuries focus on preventing secondary infection. Hydrogel dressing and hydrocolloids are commonly used. Grade 4 injuries are treated like full-thickness burn injuries and can require debridement with skin grafts, or flaps. Chronic wounds are watched more closely for selective debridement because they can evolve over time. They are poorly vascularized and can require more complex reconstructive procedures, including pedicled and free flaps.53

Key Points.

Chemical, radiation, and electrical injuries pose a unique challenge for burn surgeons acutely and during the reconstructive phase.

Each chemical has unique concerns, but all benefit from immediate removal and dilution.

Electrical injuries can cause both external flame burns and internal muscle injury.

Compartment syndrome is an important and potentially destructive clinical sequela of electrical injury that warrants early diagnosis and treatment.

Radiation exposure causes both short-term damage (skin, gastrointestinal tract) and long-term sequelae (increased risk of malignancy, central nervous system changes, and poor wound healing).

Acknowledgments

Dr B. Levi was supported by funding from National Institutes of Health/National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant K08GM109105, American Association of Plastic Surgery Academic Scholarship, International FOP Association, Plastic Surgery Foundation Pilot Award and American College of Surgeons Clowes Award. Dr B. Levi collaborates on a project unrelated to this article with Boehringer Ingelheim on a project not examined in this study.

References

- 1.Barillo DJ, Cancio LC, Goodwin CW. Treatment of white phosphorus and other chemical burn injuries at one burn center over a 51-year period. Burns. 2004;30:448–52. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2004.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boeniger MF, Ahlers HW. Federal government regulation of occupational skin exposure in the USA. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2003;76:387–99. doi: 10.1007/s00420-002-0425-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ye C, Wang X, Zhang Y, et al. Ten-year epidemiology of chemical burns in western Zhejiang Province, China. Burns. 2016;42:668–74. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson AR, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Top five chemicals resulting in injuries from acute chemical incidents—Hazardous Substances Emergency Events Surveillance, nine states, 1999-2008. MMWR Suppl. 2015;64:39–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.2015 National Burn Repository Report of Data from 2005-2014. 2015.

- 6.Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Brooks DE, et al. 2014 annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers' National Poison Data System (NPDS): 32nd annual report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2015;53:962–1147. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2015.1102927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hodgman EI, Pastorek RA, Saeman MR, et al. The Parkland Burn Center experience with 297 cases of child abuse from 1974 to 2010. Burns. 2016;42(5):1121–7. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah A, Suresh S, Thomas R, et al. Epidemiology and profile of pediatric burns in a large referral center. Clin Pediatr. 2011;50:391–5. doi: 10.1177/0009922810390677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leonard LG, Scheulen JJ, Munster AM. Chemical burns: effect of prompt first aid. J Trauma. 1982;22:420–3. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198205000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spector J, Fernandez WG. Chemical, thermal, and biological ocular exposures. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2008;26:125–36. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2007.11.002. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pullin TG, Pinkerton MN, Johnston RV, et al. Decontamination of the skin of swine following phenol exposure: a comparison of the relative efficacy of water versus polyethylene glycol/industrial methylated spirits. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1978;43:199–206. doi: 10.1016/s0041-008x(78)80044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin TM, Lee SS, Lai CS, et al. Phenol burn. Burns. 2006;32:517–21. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2005.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bloom GR, Suhail F, Hopkins-Price P, et al. Acute anhydrous ammonia injury from accidents during illicit methamphetamine production. Burns. 2008;34:713–8. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davidson SB, Blostein PA, Walsh J, et al. Resurgence of methamphetamine related burns and injuries: a follow-up study Burns. 2013;39:119–25. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amshel CE, Fealk MH, Phillips BJ, et al. Anhydrous ammonia burns case report and review of the literature. Burns. 2000;26:493–7. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(99)00176-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang F, Zheng XF, Ma B, et al. Mass chemical casualties: treatment of 41 patients with burns by anhydrous ammonia. Burns. 2015;41:1360–7. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2015.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White CE, Park MS, Renz EM, et al. Burn center treatment of patients with severe anhydrous ammonia injury: case reports and literature review. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28:922–8. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e318159a44e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X, Zhang Y, Ni L, et al. A review of treatment strategies for hydrofluoric acid burns: current status and future prospects. Burns. 2014;40:1447–57. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuanhai Z, Liangfang N, Xingang W, et al. Clinical arterial infusion of calcium gluconate: the preferred method for treating hydrofluoric acid burns of distal human limbs. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2014;27:104–13. doi: 10.2478/s13382-014-0225-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y, Wang X, Sharma K, et al. Injuries following a serious hydrofluoric acid leak: first aid and lessons. Burns. 2015;41:1593–8. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis KG. Acute management of white phosphorus burn. Mil Med. 2002;167:83–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chou TD, Lee TW, Chen SL, et al. The management of white phosphorus burns. Burns. 2001;27:492–7. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(01)00003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaufman T, Ullmann Y, Har-Shai Y. Phosphorus burns: a practical approach to local treatment. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1988;9:474–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eldad A, Wisoki M, Cohen H, et al. Phosphorous burns: evaluation of various modalities for primary treatment. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1995;16:49–55. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199501000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karunadasa KP, Abeywickrama Y, Perera C. White phosphorus burns managed without copper sulfate: lessons from war. J Burn Care Res. 2010;31:503. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181db52be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pargament JM, Armenia J, Nerad JA. Physical and chemical injuries to eyes and eyelids. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:234–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu H, Wang K, Wang Q, et al. A modified surgical technique in the management of eyelid burns: a case series. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:373. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-5-373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rao NK, Goldstein MH. Acid and alkali burns. In: Yanoff M, Duker J, editors. Ophthalmology. 4th. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2014. pp. 296–8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levine MD, Zane R. Chemical injuries. In: Marx JA, Hocksberger RS, Walls RM, editors. Rosen's emergency medicine concepts and clinical practice. 8th. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2014. pp. 818–28. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paterson CA, Pfister RR, Levinson RA. Aqueous humor pH changes after experimental alkali burns. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975;79:414–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(75)90614-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rihawi S, Frentz M, Becker J, et al. The consequences of delayed intervention when treating chemical eye burns. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007;245:1507–13. doi: 10.1007/s00417-007-0597-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DiVincenti F, Moncrief J, Pruitt BJ. Electrical injuries: a review of 65 cases. J Trauma. 1969;9:497–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Purdue GF, Hunt JL. Electrocardiographic monitoring after electrical injury: necessity or luxury. J Trauma. 1986;26:166–7. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198602000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hunt JL, McManus WF, Haney WP, et al. Vascular lesions in acute electric injuries. J Trauma. 1974;14:461–73. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197406000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arnoldo B, Klein M, Gibran NS. Practice guidelines for the management of electrical injuries. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27:439–47. doi: 10.1097/01.BCR.0000226250.26567.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leversedge FJ, Moore TJ, Peterson BC, et al. Compartment syndrome of the upper extremity. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:544–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.12.008. [quiz: 560] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim SH, Cho GY, Kim MK, et al. Alterations in left ventricular function assessed by two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography and the clinical utility of cardiac troponin I in survivors of high-voltage electrical injury. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1282–7. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819c3a83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park KH, Park WJ, Kim MK, et al. Alterations in arterial function after high-voltage electrical injury. Crit Care. 2012;16:R25. doi: 10.1186/cc11190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boozalis GT, Purdue GF, Hunt JL, et al. Ocular changes from electrical burn injuries. A literature review and report of cases. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1991;12:458–62. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199109000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saffle JR, Crandall A, Warden GD. Cataracts: a long-term complication of electrical injury. J Trauma. 1985;25:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Janus TJ, Barrash J. Neurologic and neurobehavioral effects of electric and lightning injuries. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1996;17:409–15. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199609000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pliskin NH, Capelli-Schellpfeffer M, Law RT, et al. Neuropsychological symptom presentation after electrical injury. J Trauma. 1998;44:709–15. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199804000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Egeland B, More S, Buchman SR, et al. Management of difficult pediatric facial burns: reconstruction of burn-related lower eyelid ectropion and perioral contractures. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19:960–9. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318175f451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Donelan MB. Reconstruction of electrical burns of the oral commissure with a ventral tongue flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95:1155–64. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199506000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith MA, Muehlberger T, Dellon AL. Peripheral nerve compression associated with low-voltage electrical injury without associated significant cutaneous burn. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:137–44. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200201000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Potter BK, Burns TC, Lacap AP, et al. Heterotopic ossification following traumatic and combat-related amputations. Prevalence, risk factors, and preliminary results of excision. J Bone Jonit Surg Am. 2007;89:476–86. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levi B, Jayakumar P, Giladi A, et al. Risk factors for the development of heterotopic ossification in seriously burned adults: a National Institute on Disability, Independent Living and Rehabilitation Research burn model system database analysis. J Trauma acute Care Surg. 2015;79:870–6. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ranganathan K, Loder S, Agarwal S, et al. Heterotopic ossification: basic-science principles and clinical correlates. J Bone Jonit Surg Am. 2015;97:1101–11. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.01056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolbarst AB, Wiley AL, Jr, Nemhauser JB, et al. Medical response to a major radiologic emergency: a primer for medical and public health practitioners. Radiology. 2010;254(3):660–77. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09090330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flynn DF, Goans RE. Nuclear terrorism: triage and medical management of radiation and combined-injury casualties. Surg Clin North Am. 2006;86(3):601–36. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.DiCarlo AL, Maher C, Hick JL, et al. Radiation injury after a nuclear detonation: medical consequences and the need for scarce resources allocation. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2011;5(Suppl 1):S32–44. doi: 10.1001/dmp.2011.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Palmer JL, Deburghgraeve CR, Bird MD, et al. Development of a combined radiation and burn injury model. J Burn Care Res. 2011;32(2):317–23. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31820aafa9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bray FN, Simmons BJ, Wolfson AH, et al. Acute and chronic cutaneous reactions to ionizing radiation therapy. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2016;6(2):185–206. doi: 10.1007/s13555-016-0120-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salvo N, Barnes E, van Draanen J, et al. Prophylaxis and management of acute radiation-induced skin reactions: a systematic review of the literature. Curr Oncol. 2010;17(4):94–112. doi: 10.3747/co.v17i4.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hymes SR, Strom EA, Fife C. Radiation dermatitis: clinical presentation, pathophysiology, and treatment 2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(1):28–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]