Abstract

Objective

Children are vulnerable to secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure because of limited control over their indoor environment. Homes remain the major place where children may be exposed to SHS. Our study examines the magnitude, patterns and determinants of SHS exposure in the home among children in 21 low- and middle-income countries.

Methods

Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) data, a household survey of adults 15 years of age or older. Data collected during 2009–2013 were analyzed to estimate the proportion of children exposed to SHS in the home. GATS estimates and 2012 United Nations population projections for 2015 were also used to estimate the number of children exposed to SHS in the home.

Results

The proportion of children younger than 15 years of age exposed to SHS in the home ranged from 4.5% (Panama) to 79.0% (Indonesia). Of the approximately one billion children younger than 15 years of age living in the 21 countries under study, an estimated 507.74 million were exposed to SHS in the home. China, India, Bangladesh, Indonesia and the Philippines accounted for almost 84.6% of the children exposed to SHS. The prevalence of SHS exposure was higher in countries with higher adult smoking rates and was also higher rural areas than in urban areas in most countries.

Conclusions

A large number of children were exposed to SHS in the home. Encouraging voluntary smoke-free rules in homes and cessation in adults have the potential to reduce SHS exposure among children and prevent SHS-related diseases and deaths.

Keywords: tobacco, secondhand smoke, children, children exposed to SHS in the home, GATS, low- and middle-income countries

INTRODUCTION

Exposure to secondhand smoke (SHS) from tobacco products is harmful to infants and children and increases their risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), more severe asthma, ear infections and respiratory infections.1–3 SHS exposure also can affect children’s physical development, including their lung development.1–3 In addition, young children are uniquely vulnerable to SHS exposure because they have limited control over their environment.1

Advances in scientific knowledge on the dangers of SHS have raised awareness of the importance of protecting non-smokers from exposure through proven interventions, including smoke-free home initiatives.1–4 Acknowledgement of the dangers of SHS and the need to address the problem is reflected in the Guidelines on Protection from Exposure to Tobacco Smoke, which were adopted in support of Article 8 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) and which present best practices to eliminate SHS exposure in indoor environments.5 Article 8 calls on governments to promote effective measures to protect all people from exposure to tobacco smoke within 5 years of ratification, and it gives policy makers a road map to achieve effective protection.5

According to the World Health Organization (WHO),6 24% of low- and middle-income countries (34 countries), by the end of 2014, adopted smoke-free policies that covered all public places such as work sites, bars, restaurants, schools, universities and health care institutions.7,8 Although smoke-free policies protect non-smokers from SHS in public places and stimulate adoption of similar rules in homes through normalization of smoke-free environments, other measures may also be required to fully protect people from SHS exposure in non-public settings.9,10

Children’s exposure to SHS in the home has been measured by studies that used cotinine as a biochemical measure of exposure. These studies found the presence of cotinine in children’s blood serum and hair.11 Additional studies have assessed environmental markers of nicotine in homes occupied by children.12–14 For example, a cross-sectional study involving 31 countries measured air nicotine concentrations in households and cotinine concentrations in hair among non-smoking women and children in convenience samples of 40 households in each country.13 The study found that the dose–response relationship was more pronounced among children than women. Moreover, air nicotine concentrations increased by an estimated 12.9 times in households that allowed smoking inside compared with those that prohibited smoking.

Research suggests that globally, an estimated 40% of children were exposed to SHS in any environment in 2004.14 However, a study that used Global Youth Tobacco Survey data from 132 countries collected during 1999–2005 estimated that 43.9% of youth aged 13 – 15 years were exposed to SHS at home.15 In the United States of America, a national study that measured participants’ serum cotinine levels found that an estimated 40.6% of children 3–11 years of age had recent exposure to SHS.16 A study in Hong Kong found that 14.1% of students in grades 2–4 were exposed to SHS in the home.17 A study in the United Kingdom found a steady increase in the proportion of children living in a home reported to be smoke-free from 63.0% in 1998 to 87.3% in 2012.11 While some studies, mostly from high income countries, allow us to understand the magnitude of the problem and facility policy development, further evidence need to be generated particularly from low- and middle-income countries where data is limited. Furthermore, data for these countries is important help understanding the magnitude of the problem worldwide and to define tobacco control challenges, set priorities, guide solutions and monitor progress. This article seeks to reduce this knowledge gap by using data from the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) and population projections from the United Nations (UN) to estimate the proportion and number of children exposed to SHS in the home in 21 low- and middle-income countries.

METHODS

Data Source

We used GATS data from 21 countries that conducted the survey during 2009–2013: Argentina, Bangladesh, China, Egypt, Greece, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Nigeria, the Philippines, Panama, Poland, Qatar, Romania, Russian Federation, Thailand, Turkey, Ukraine, Uruguay and Vietnam. GATS was conducted in each country as a nationally representative household survey of adults 15 years of age or older to provide comprehensive information on tobacco use. A standard protocol is used for sampling, data collection, data management and weighting. This systematic collection of data allows researchers to monitor adult tobacco use and track key tobacco control indicators.18 Details of GATS methods have been published elsewhere.19 Sample sizes in the 21 countries ranged from 4359 (Malaysia) to 69 296 (India), and response rates ranged from 65.1% (Poland) to 97.7% (Russian Federation).

Measures

Presence of children in the home

GATS uses a household questionnaire and an individual questionnaire. The household questionnaire is used to collect information about household size, composition and family members’ tobacco use; the individual questionnaire is used to collect data from one randomly chosen member of each household who is 15 years of age or older.

The household survey uses two questions to collect information on the number of people in the household: “In total, how many persons live in this household” and “How many of these household members are 15 years of age or older?” We computed the number of children younger than 15 years in each household by subtracting the number of adults 15 years of age or older from the total number of household members.

Adult tobacco smoking

The household questionnaire also collects information about tobacco use among all household members. One household member who is 18 years of age or older is asked to list all household members who are 15 years of age or older who currently smoke tobacco, including cigarettes, cigars, and pipes. If no household member is 18 years of age or older, a younger household member can answer this question.

Tobacco use was assessed on the individual questionnaire with the following question: “Do you currently smoke tobacco on a daily basis, less than daily, or not at all?” We used responses to this question to estimate the proportion of households with an adult smoker in each country.

SHS exposure in the home

We used two questions to assess SHS exposure in the home. First, each respondent was asked, “Which of the following best describes the rules about smoking inside your home: smoking is allowed inside of your home, smoking is generally not allowed inside your home but there are exceptions, smoking is never allowed inside your home, or there are no rules about smoking in your home?” Respondents who indicated that smoking was “never allowed” inside their home were considered to live in a smoke-free home. Those who indicated that smoking was allowed inside their home or allowed with exceptions were then asked, “How often does anyone smoke inside your home?” Responses were categorized as “none” (those who responded “never”) vs. “some” (those who responded “daily,” “weekly” or “monthly”). Those who responded “never” were also considered to live in a smoke-free home and therefore not exposed to SHS at home. Those who indicated “daily,” “weekly” or “monthly” were considered to have been exposed to SHS at home.

Urban vs. rural residence

The GATS sample design stratifies data by sex and residence (urban and rural) primarily to allow comparisons of estimates by these variables between countries.18,19 With the exception of Argentina, all countries in our analysis used a sample design stratified by residence.

Analysis

We examined the proportion of children younger than 15 years of age who were exposed to SHS in the home by country and by urban vs. rural residence. Data for each country were weighted and calibrated to the national adult population. We used SPSS Complex Samples V.22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA) for data analysis. We calculated the weighted percentage of children younger than 15 years of age who were exposed to SHS in the home nationally and by urban and rural residence. We calculated 95% confidence intervals separately for each country. We also conducted a simple Pearson correlation between national SHS exposure prevalence estimates in the home for children and national smoking prevalence estimates for adults. In each country, we estimated the number of children exposed to SHS in the home by multiplying the prevalence from the GATS data by UN national population projections for 2015.20

RESULTS

Table 1 shows that among the 21 countries assessed, the proportion of children younger than 15 years of age who were exposed to SHS in the home ranged from 4.5% in Panama to 79.0% in Indonesia. Only two countries, Panama and Nigeria, had exposure prevalence estimates of less than 10.0%. When stratified by rural vs. urban residence, the proportion of children exposed to SHS in the home was higher among those living in rural areas than in urban areas, with the exception of Mexico, Romania and Russian Federation.

Table 1.

Exposure to secondhand smoke (SHS) in the home among children younger than 15 years 21 countries, by country and residence—Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS), 2009–2013

| Country (and GATS year) | Percent of children exposed to SHS in the home | Estimated no. of children aged 0–14 years, in thousands* | Estimated no. of children exposed to SHS in the home, in thousands | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Urban | Rural | |||

| Argentina, 2012 | 33.8 | NA | NA | 10,043.6 | 3,397.8 |

| Bangladesh, 2009 | 57.0 | 46.9 | 60.3 | 47,852.1 | 27,297.6 |

| China, 2010 | 66.7 | 57.7 | 72.2 | 246,707.2 | 164,613.4 |

| Egypt, 2009 | 64.1 | 59.0 | 66.9 | 24,604.9 | 15,782.3 |

| Greece, 2013 | 62.3 | 60.1 | 68.9 | 1,612.5 | 1,004.3 |

| India, 2009–2010 | 44.6 | 34.6 | 47.7 | 363,764.5 | 162,139.5 |

| Indonesia, 2011 | 79.0 | 68.2 | 89.2 | 71,791.6 | 56,720.7 |

| Malaysia, 2011 | 36.9 | 33.3 | 44.8 | 7,827.7 | 2,885.8 |

| Mexico, 2009 | 16.6 | 18.6 | 11.0 | 35,418.6 | 5,889.1 |

| Nigeria, 2012 | 5.4 | 3.4 | 6.2 | 70,307.5 | 3,816.8 |

| Panama, 2013 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 4.6 | 1,078.3 | 48.5 |

| Philippines, 2009 | 57.5 | 46.0 | 67.2 | 32,970.5 | 18,964.7 |

| Poland, 2009–2010 | 45.4 | 44.6 | 46.2 | 5,733.3 | 2,603.0 |

| Qatar, 2013 | 15.8 | NA | NA | 240.2 | 37.9 |

| Romania, 2011 | 36.1 | 40.9 | 31.6 | 3,282.3 | 1,185.4 |

| Russian Federation, 2009 | 34.7 | 35.3 | 33.2 | 21,428.9 | 7,426.2 |

| Thailand, 2011 | 35.8 | 27.9 | 38.5 | 12,837.2 | 4,597.4 |

| Turkey, 2012 | 61.2 | 58.3 | 66.3 | 19,262.1 | 11,784.4 |

| Ukraine, 2010 | 23.0 | 22.7 | 23.4 | 6,399.2 | 1,470.7 |

| Uruguay, 2009 | 36.3 | 36.0 | 38.8 | 758.9 | 275.2 |

| Vietnam, 2010 | 75.5 | 66.7 | 79.0 | 20,918.4 | 15,800.9 |

| Total | 48.7 | 994,795.8 | 507,741.3 | ||

Based on population estimates produced by the Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat, World Population Prospects: The 2012 Revision, http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/index.htm.

NA – not applicable

According to the UN population projections, approximately 994.80 million children younger than 15 years of age live in the 21 countries representing approximately 52.2% of world children in this age group. Of these, an estimated 48.7% (507.74 million children) were exposed to SHS in the home. Numbers ranged from 164.61 million in China to 38, 000 in Qatar. The level of exposure in the following five Asian countries accounted for 84.6% of the children exposed to SHS in the home: China (164.61 million), India (162.14 million), Indonesia (57.72 million), Bangladesh (27.30 million) and the Philippines (19.00 million).

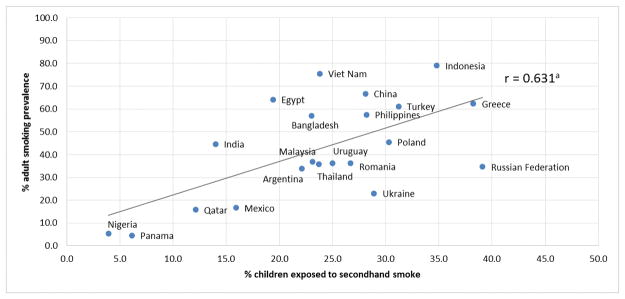

Countries with the lowest smoking prevalence among adults, such as Panama and Nigeria, generally had lower proportions of children exposed to SHS in the home (correlation (r)=0.631) (figure 1). In contrast, countries with high smoking prevalence, such as Indonesia, Vietnam and China, generally had higher proportions of children exposed to SHS in the home.

Figure 1.

Correlation (r) between children (younger than 15 years) exposed to secondhand smoke in the home and smoking prevalence among adults in 21 countries—Global Adult Tobacco Survey, 2009–2013

DISCUSSION

We characterized the prevalence of SHS exposure among children in 21 low- and middle-income countries and found that approximately one-half billion children were exposed to SHS in their homes. Countries with high percentage of children exposed to SHS are more likely to experience a significant burden of SHS-related diseases and deaths. However, five countries—China, India, Indonesia, Bangladesh and the Philippines—that accounted for 84.6% of these children highlight the global magnitude of the burden of SHS exposure. People living in these countries may have a higher risk of diseases, death and disabilities that are associated with SHS exposure. Our findings underscore the importance of countries adopting the MPOWER policy package developed as part of the WHO FCTC as a way to protect people from SHS exposure through effective policies and programs. The six components of MPOWER are smoke-free policies; Monitor tobacco use and prevention policies; Protect people from tobacco smoke; Offer help to quit tobacco use; Warn about the dangers of tobacco; Enforce bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship; and Raise taxes on tobacco.5,6,8 These policies and programs are key to reducing smoking, and they also help create an environment that motivates people to quit tobacco smoking, which will in turn reduce SHS exposure among children.

Children may suffer disproportionately from SHS exposure, as they generally spend a significant amount of time at home.3,7,14 Children are also especially vulnerable because they have limited or no say on smoking in indoor places, particularly at home.3,7 In addition, their vulnerability may be exacerbated by a lack of medical and public health interventions, particularly in low-income countries. 21 However, SHS-related diseases, death and disabilities in children are preventable,1,22 and evidence-based interventions, such as the adoption of voluntary rules for smoke-free homes, can be used to eliminate SHS exposure among children in the home.

Community education programs could also be used to increase knowledge and change attitudes about the health effects of SHS exposure, which could in turn increase the adoption of rules for smoke-free homes.23,24 These programs could be promoted by health care providers and other professionals who are in regular contact with families that have children. For example, the Roy Castle Lung Cancer Foundation developed a training program in the United Kingdom to help health professionals reduce children’s SHS exposure in the home.25 The training is designed to teach professionals how to discuss SHS exposure in the home with parents and provide a brief intervention to mitigate the problem.

Our study found a positive correlation between adult smoking rates and SHS exposure among children in the home. This finding suggests that, in addition to promoting rules for smoke-free homes, efforts to reduce adult smoking could also help reduce SHS exposure among children in the home.7,23 Population-level efforts to further reduce adult smoking may include strategies such as increasing tobacco taxes and adopting smoke-free policies in public places.2,7,24 As the guidelines for Article 8 of the WHO FCTC indicate and evidence has shown, adoption of smoke-free policies in public places also has the potential to reduce SHS exposure in private homes.5,7,24 In particular, these policies can encourage a shift in social norms in which people begin to implement smoking restrictions in their own homes.7,24,26

Our study also found that SHS exposure in the home was higher among children living in rural areas than those in urban areas in most countries. Because people living in rural areas tend to have lower socioeconomic status,27,28 this finding indicates that SHS exposure may disproportionately affect children with low socioeconomic status.29,30 To address this disparity, tobacco prevention and control programs in low- and middle-income countries might consider focusing on rural populations and other disadvantaged communities. These programs could work to raise awareness about the dangers of SHS and encourage the voluntary adoption of rules for smoke-free homes.

This study is subject to at least two limitations. First, the potential for exposure misclassification exists because GATS does not use biochemical markers of inhaled smoke, such as saliva and urinary cotinine concentrations, to validate SHS exposure. However, past studies that compared self-reported exposure and biochemical markers have found these indicators to be strongly related.31,32 Second, variations in data collection times and changes in the strategies used to reduce SHS exposure in the 21 countries assessed restricted our ability to make comparisons between countries.

Despite these limitations, this study can help researchers understand the magnitude of SHS exposure among children in several low- and middle-income countries. It also indicates that SHS exposure among children is high, especially in countries with high smoking prevalence and among rural populations. Implementing strategies to reduce SHS exposure, including the guidelines for Articles 8 and 148 of the WHO FCTC, could encourage adoption of voluntary rules for smoke-free homes and support cessation among smokers. Increased efforts to reduce SHS exposure in countries with large numbers of children could help to substantially reduce the harmful effects of SHS exposure among children across the world.

What this paper adds.

Evidence has shown that children exposed to secondhand smoke (SHS) are at risk of SHS-related diseases particularly. Our study shows that about half a billion children in 21 low- and middle-income countries, most of which have had limited evidence, are at risk of SHS-related diseases due to exposure at home.

Although countries with high percentage of children exposed to SHS are more likely to experience a significant burden of SHS related diseases and deaths, five countries—China, India, Indonesia, Bangladesh and the Philippines—that are home to majority of the children exposed, highlight the global magnitude of the burden of SHS exposure.

Acknowledgments

Funding This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. GATS was supported by the Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Ministries of Health in Greece, India, Malaysia, Panama, Qatar and Thailand.

Amanda Crowell, Technical Writer-Editor Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Atlanta GA, USA for substantial editing of the manuscript

Edward Rainey Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Atlanta GA, USA for preparing the graph

Jo Jewell and Julie Brummer of the WHO Regional Office for Europe for critically reviewing the final draft of manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclaimer The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, World Health Organization or the governments of Argentina, Bangladesh, China, Egypt, Greece, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Nigeria, Panama, the Philippines, Poland, Qatar, Romania, Russian Federation, Thailand, Turkey, Ukraine, Uruguay or Vietnam.

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Respiratory Health Effects of Passive Smoking: Lung Cancer and Other Disorders. Washington, DC: Office of Research and Development, Office of Health and Environmental Assessment, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; 1992. EPA/600/6-90/006F. [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking – 50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borland R, Mullins R, Trotter L, et al. Trends in environmental tobacco smoke restriction in the home. Tob Control. 1999;8:266–71. doi: 10.1136/tc.8.3.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Guidelines on Protection from Exposure to Tobacco Smoke. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003. [accessed on 26 Aug 2015]. http://www.who.int/fctc/cop/art%208%20guidelines_english.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2015: Raising taxes on tobacco. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015. [accessed on16 Sep 2015]. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85380/1/9789241505871_eng.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 7.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Smoke-free Policies. IARC Handbook of Cancer Prevention. Vol. 13. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2009. [accessed on 26 May 2015]. http://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online/prev/index1.php. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adoption of the guidelines for implementation of Article 8. World Health Organization, Conference of the Parties to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, second session, decision FCTC/COP; [Accessed September, 2015]. http://www.who.int/gb/fctc/PDF/cop2/FCTC_COP2_DIV9-en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Massachusetts Smoke-free Housing Project. Market demand for smoke-free rules in multi-unit residential properties and landlords’ experiences with smoke-free rules. Boston: The Massachusetts Smoke-free Housing Project, Public Health Advocacy Institute, Northeastern University School of Law; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomson G, Wilson N, Howden-Chapman P. Population level policy options for increasing the prevalence of smoke-free homes. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:298–304. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.03809.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jarvis MJ, Feyerbend C. Recent trends in children’s exposure to second-hand smoke in England: cotinine evidence from the Health Survey for England. Addiction. 2015;110:1484–1492. doi: 10.1111/add.12962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marano C, Schober SE, Brody DJ, et al. Secondhand tobacco smoke exposure among children and adolescents: United States, 2003–2006. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1299. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0880. originally published online October 19, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wipfli H, Avila-Tang E, Navas-Acien A, et al. Secondhand smoke exposure among women and children: evidence from 31 countries. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:4. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.126631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oberg M, Jaakkola MS, Woodward A, et al. Worldwide burden of disease from exposure to secondhand smoke: a retrospective analysis of data from 192 countries. The Lancet. 2010;377:139–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61388-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warren CW, Jones NR, Peruga A, et al. Global Youth Tobacco Surveillance, 2000–2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008;57(suppl 1):1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: disparities in nonsmokers’ exposure to secondhand smoke — United States, 1999–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(04):103–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho SY, Wang MP, Lo WS, et al. Comprehensive smoke-free legislation and displacement of smoking into the homes of young children in Hong Kong. Tobacco Control. 2010;19:129–133. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.032003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Global Adult Tobacco Survey Collaborative group. Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) Quality Assurance: Guidelines and Documentation. Version 2. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palipudi KM, Sinha DN, Choudhury S, Mustafa Z, Andes L, Asma S. Exposure to tobacco smoke among adults in Bangladesh. Indian J Public Health. 2011;55:210–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.89942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. [accessed on June, 2015];Population Division, World Population Prospects: The 2012 Revision. http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/index.htm.

- 21.Creel L. Children’s environmental health: risks and remedies. [Accessed on May, 2015];PRB making a link. 2000 http://www.prb.org/pdf/childrensenvironhlth_eng.pdf.

- 22.California Environmental Protection Agency. Health effects of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke—final report and appendices. Sacramento, CA: California Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hopkins D, Briss P, Ricard CJ, et al. Reviews of Evidence Regarding Interventions to Reduce Tobacco Use and Exposure to Environmental Tobacco Smoke. [Accessed May, 2015];Am J Prev Med. 2001 20(2S):16–66. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00297-x. http://www.thecommunityguide.org/tobacco/tobac-AJPM-evrev.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. International consultation on environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) and child health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1999. [Accessed May, 2015]. http://www.who.int/tobacco/research/en/ets_report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gordon J, Friel B, McGranachan M. Professional training to reduce children’s exposure to second-hand smoke in the home: evidence-based considerations on targeting and content. Perspect Public Health. 2012 May;132(3):135–43. doi: 10.1177/1757913912442271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng K-W, Glantz SA, Lightwood JM. Association between smokefree laws and voluntary smokefree-home rules. AM J Prev Med. 2011;41(6):566–572. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cai L, Wu X, Goyal A, et al. Multilevel analysis of the determinants of southwest China in a tobacco-cultivating rural area of smoking and second-hand smoke exposure. Tob Control. 2013;22:ii16–ii20. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization. The economics of social determinants of health and health inequalities: a resource book. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2013. [accessed on16 Sept 2015]. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/84213/1/9789241548625_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gartner CE, Hall WD. Is the socioeconomic gap in childhood exposure to secondhand smoke widening or narrowing? Tobacco Control. 2012 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization Region Office for Europe. Tobacco and inequities: Guidance for addressing inequities in tobacco-related harm. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2014. [Accessed 18 Sept 2016]. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/247640/tobacco-090514.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glover M, Hadwen G, Chelimo C, et al. Parent versus child reporting of tobacco smoke exposure at home and in the car. N Z Med J. 2013;126(1375):37–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jarvis M, Tunstall-Pedoe H, Feyerabend C, Vesey C, Salloojee Y. Biochemical markers of smoke absorption and self-reported exposure to passive smoking. Epidemiol Community Health. 1984;38(4):335–339. doi: 10.1136/jech.38.4.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]