Abstract

Optimal breastfeeding practices entail the early initiation of breastfeeding soon after delivery of the baby, exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life and the continuation of breastfeeding complemented by solid food up until two years of age. Breastfeeding has wide-ranging health benefits for both the mother and her child; however, many factors contribute to low rates of exclusive breastfeeding. This article highlights the benefits of optimal breastfeeding as well as trends and determinants associated with breastfeeding both worldwide and in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. Strategies to optimise breastfeeding and overcome breastfeeding barriers in the GCC region are recommended, including community health and education programmes and ‘baby-friendly’ hospital initiatives. Advocates of breastfeeding are needed at the national, community and family levels. In addition, more systematic research should be conducted to examine breastfeeding practices and the best strategies to promote breastfeeding in this region.

Keywords: Breastfeeding, Trends, Maternal-Child Health Services, Health Planning Recommendations, Arab World

Breast milk is a natural, renewable and complete source of food during the first six months of life, fulfilling all of an infant’s nutritional requirements.1 The United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) defines optimal breastfeeding as the practice of exclusively breastfeeding during the first six months, followed by breastfeeding with the appropriate addition of complementary food thereafter up until two years of age.2 The early initiation of breastfeeding—defined as breastfeeding within an hour of delivery—is considered an indicator of best practice.3 The beneficial effects of breastfeeding on maternal and child health are well recognised. Due to its excellent immunological and anti-inflammatory properties, breast milk can protect both mothers and children against various illnesses and diseases.4 In addition, breastfeeding also improves bonding between a mother and her newborn as well as avoiding the cost of purchasing infant formula.5,6

By 2025, the World Health Organization (WHO) aims to achieve a 50% universal exclusive breastfeeding rate which will significantly reduce maternal, neonatal, infant and childhood mortality.7–9 According to UNICEF, improving breastfeeding practices worldwide could save the lives of an estimated 1.5 million children annually.2 Furthermore, the risk of mortality before the age of five years is expected to decrease from 13% to 11.6% if optimal breastfeeding practices are followed.10 While both the WHO and UNICEF have made tremendous efforts to encourage universal exclusive breastfeeding, this goal has been achieved only at a suboptimal level, with some children not breastfed at all.2,7

A recent report indicated that the rate of exclusive breastfeeding among infants of 4–6 months of age increased from 32% in 1995 to 40% in 2013.11 However, as per rates reported by UNICEF for the Middle East in 2016, exclusive breastfeeding rates for infants at 6 months of age in this region have declined.12 This article aimed to highlight the benefits of exclusive breastfeeding, analyse existing breastfeeding trends and determinants and identify strategies and recommendations to improve breastfeeding rates in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries.

Benefits of Optimal Breastfeeding

Breast milk is the ideal source of nutrition for infants, as it contains the appropriate proportion and quantity of vitamins, protein and fat.1 A recent meta-analysis indicated that breastfeeding protects infants against diarrhoea, otitis media and respiratory infections, thus reducing related hospital admissions.9 Moreover, intelligence quotient (IQ) has been found to correlate positively with breastfeeding practices for both mother and child.9 A 30-year prospective birth cohort study conducted in Brazil also showed a positive correlation between mean breastfeeding duration and IQ and educational attainment; in addition, breastfeeding was to found to improve an infant’s immune system as well as have a significant positive influence on long-term economic and social outcomes.13

In the GCC region, a case-control study conducted in 2012 reported that autism spectrum disorder (ASD) was significantly correlated with suboptimal breastfeeding practices in Oman.14 The risk of ASD was related to the late initiation of breastfeeding and insufficient intake of colostrum, whereas longer periods of continued breastfeeding lowered the risk of ASD. Moreover, the risk of ASD was linked with premature delivery; this may be because premature babies are often separated from their mothers and may therefore not receive sufficient quantities of breast milk.14

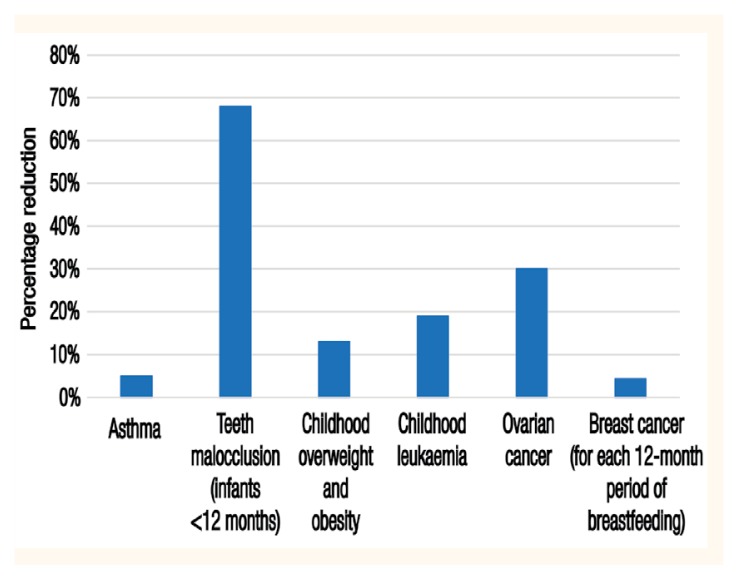

For breastfeeding mothers, both exclusive and continued breastfeeding practices are strongly linked with maternal amenorrhoea, which is considered a natural birth spacing method.9 In addition, mothers who do not breastfeed have an increased risk of premenopausal breast cancer, ovarian cancer, retained gestational weight gain, type 2 diabetes, myocardial infarctions and metabolic syndrome.15 Figure 1 shows the extent to which breastfeeding can reduce the risk of various maternal and child health problems.9

Figure 1.

Chart showing percentage reductions attributable to breastfeeding of various maternal and child health problems.9

Breastfeeding Trends in Gulf Cooperation Council Countries

In the Middle East, universal breastfeeding rates are low and do not achieve the target set by the WHO, with breastfeeding rates decreasing from 30% in 1990 to 26% in 2006.10,14 In Saudi Arabia, a study reported that exclusive breastfeeding practices were suboptimal in Abha city, despite most participants demonstrating either good (55.3%) or excellent (30.7%) levels of knowledge regarding breastfeeding practices and 62.2% reporting positive attitudes towards breastfeeding; in contrast, unsatisfactory levels of knowledge were found in only 14% of mothers overall.16 In Bahrain, exclusive and continued breastfeeding rates in 2010 among children <6 and 20–23 months old were 34% and 41%, respectively.17 Moreover, two-thirds of Bahraini mothers supplemented breastfeeding with other forms of nutrition before their babies were six months old.17

In Oman, breastfeeding rates are reportedly still suboptimal despite implementation of a ‘baby-friendly’ hospital initiative (BFHI) in 1990 to promote exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of a baby’s life.18 The rate of exclusive breastfeeding at birth was 97.5% in 2005 but decreased to 94.9% in 2012; in addition, only 31.3% of children were exclusively breastfed at six months in 2005, with this rate decreasing to 9.1% in 2012. Overall, the majority of Omani children received infant formula at six months of age in both 2005 and 2012 (60.7% and 90.1%, respectively).18 In Kuwait, exclusive breastfeeding rates at birth and six months of age in 2011 were 81.8% and 15.2%, respectively.19 Overall, 45.3% of women reported food supplementation at six months, although the rate of continued breastfeeding at 12–15 months was not reported. The average duration of breastfeeding was 2.7 months.19

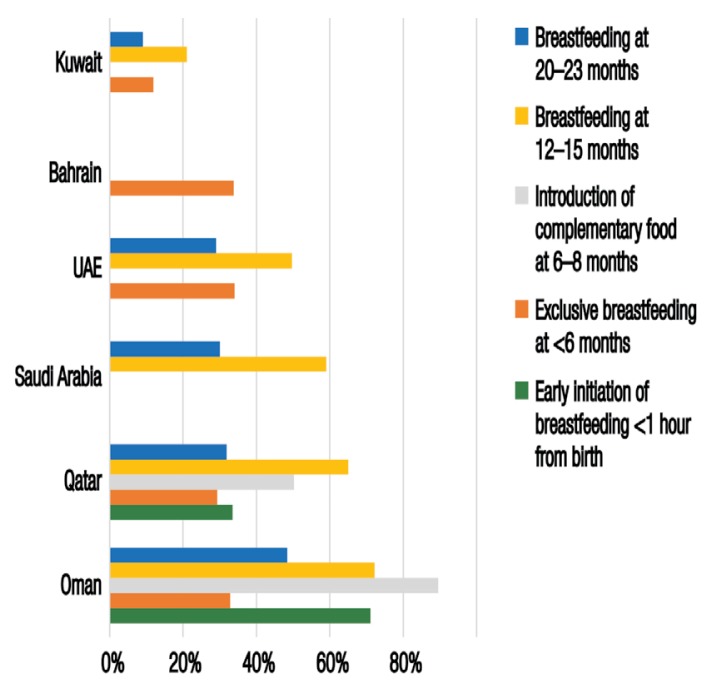

In the United Arab Emirates (UAE), mixed feeding and complementary food and fluid addition to breastfeeding is a common practice reported to start as early as one month after birth.20 In Qatar, a cross-sectional study conducted among 770 mothers with children under 24 months old indicated that breastfeeding practices did not align with the recommendations of the WHO and UNICEF.21 While 49.9% of infants were reportedly breastfed for up to one year after birth, the percentage of those breastfed up until two years dropped to 45.4%.21 Figure 2 shows recent breastfeeding trends in GCC countries based on data reported by the UNICEF.12

Figure 2.

Chart showing breastfeeding trends in Gulf Cooperation Council countries according to recent data* reported by the United International Children’s Emergency Fund.12

UAE = United Arab Emirates.

*Data sourced from the following years: 2014 (Oman), 2012 (Qatar), 1996 (Saudi Arabia and Kuwait; national surveys) and 1995 (UAE and Bahrain; national surveys).

Global Determinants of Breastfeeding Practices

The WHO has identified several factors which contribute to a low rate of universal exclusive breastfeeding, including sociocultural, health system-related, marketing, environmental and knowledge-related factors.5 Common inaccurate societal beliefs cast doubt on the nutritional sufficiency of breast milk and falsely indicate the need for additional supplementation of liquids and solids while a baby is being breastfed. Moreover, existing policies at hospitals and birth centres may be inadequate and perceived as neither supportive nor encouraging of breastfeeding.5 There is also a shortage of adequately trained health professionals to aid and advocate for breastfeeding. Increased marketing and promotion of high-quality breast milk substitutes and non-supportive work environments and employment conditions have also been observed to negatively impact breastfeeding rates.5,22

Similarly, rates of early and continued breastfeeding are significantly affected by individual attributes of the mother and infant and the mother-infant relationship in general.22 Method of delivery, parity, alcohol consumption, breast-related problems (i.e. breast engorgement or nipple soreness), occupation and education level are considered influential maternal factors affecting successful breastfeeding.23 Overall, members of the global community at all levels—including individuals, families, healthcare professionals and policy-makers—lack appropriate knowledge of the risks and negative outcomes of suboptimal breastfeeding practices.22

Determinants of Breastfeeding Practices in Gulf Cooperation Council Countries

In Saudi Arabia, an analysis of 70 studies revealed that increased maternal age, low levels of education, rural residency, low income, increased parity and non-adherence to contraceptive use were contributing factors to a higher rate and longer duration of breastfeeding, whereas insufficient breast milk production, breastfeeding problems, sickness and getting pregnant again were identified as common barriers to breastfeeding.24 Another study among Saudi Arabian employed mothers who had undergone Caesarean deliveries and did not receive breastfeeding education noted that the main factors which doubled the risk of failing to breastfeed were work-related problems, insufficient breast milk and maternal and neonatal health problems.16

In Oman, suboptimal breastfeeding practices have reportedly been linked to a lack of continuity of support, inadequate healthcare staff training/education and increased marketing of infant formula.18,25 Fortunately, in order to revitalise the BFHI campaign, Oman has recently adopted the WHO international guidelines for the marketing of breast milk substitutes.18,26 In the UAE, maternal age, education level and parity, the practice of ‘rooming-in’ (i.e. placing the infant with the mother immediately after delivery), nipple problems and the use of contraceptives were significantly related to breastfeeding practices.20 Furthermore, getting pregnant again, insufficient breast milk and self-weaning on the part of the infant were reported as the main reasons for breastfeeding cessation.20 The UAE Ministry of Health (MOH) recommends six months of exclusive breastfeeding; however, to achieve this target, breastfeeding promotion strategies and programmes need to be implemented and supported.20

In Kuwait, identified determinants of suboptimal breastfeeding rates include a lack of/inadequate antenatal breastfeeding education and support polices, with only three out of 11 non-governmental hospitals expressing an interest in BFHI practices and none as yet implementing any BFHI activities or procedures.19 Women have also reported a lack of postnatal breastfeeding support at the community level; this finding is not surprising as there are only 35 certified lactation specialists currently available in Kuwait.19 Decreased rates of breastfeeding in both Kuwait and Bahrain have also been associated with the early addition of complementary food.17,19 In addition, a short maternity leave period of 45 days was reported by Bahraini mothers to be the main factor inhibiting breastfeeding intentions after giving birth.17 Table 1 summarises the main determinants of breastfeeding practices in GCC countries.16–21,24,25

Table 1.

| High breastfeeding rates | Low breastfeeding rates |

|---|---|

|

|

Global Strategies and Recommendations to Promote Breastfeeding

In 2014, the WHO published recommendations to promote breastfeeding with the aim of achieving a target universal exclusive breastfeeding rate of 50% by 2025.7 All hospitals and birth centres are encouraged to provide the maximum level of breastfeeding support possible, for example by implementing optimal BFHI breastfeeding policies, hiring specialised healthcare professionals and, at the institutional level, maintaining breastfeeding certifications and birth records.7 These recommendations are important to ensure continuity of support for breastfeeding mothers during the postnatal period. Another recommendation is the implementation of community projects and special strategies under the supervision of community leaders to support breastfeeding mothers at home once they have been discharged after delivery.7 As such, effective channels of communication and the media should be utilised to increase community knowledge and awareness of breastfeeding. Individualised and group counselling by a trained health professional would also be helpful in improving rates of exclusive breastfeeding.7 The WHO also recommends strict adherence to marketing legislation for breast milk substitutes, with any violations to be observed and controlled by legal regulations.7,26 Government-implemented improvements in working conditions are highly recommended to encourage breastfeeding; for example, by ensuring a mandatory six-month paid maternity leave period for all new mothers.7 Finally, the WHO recommends additional training for healthcare professionals focusing on problem-solving abilities and efficient counselling of breastfeeding mothers so as to promote optimal breastfeeding practices.7

According to joint WHO and UNICEF guidelines, all hospitals and birthing facilities should have a written breastfeeding policy which should be regularly distributed to all healthcare staff.27 In addition, special training sessions for healthcare personnel should be routinely implemented to enhance the skills necessary to implement the policy.27 Pregnant women should be informed of the benefits of breastfeeding and new mothers encouraged to initiate early breastfeeding, for example by allowing ‘rooming-in’ practices.22,27 In addition, practical education regarding breastfeeding should also be provided, instructing mothers on how to continue breastfeeding in a variety of scenarios (e.g. after discharge, on demand or if they have been separated from their infant) and reminding them not to give their infants pacifiers or supplement breast milk with any other kind of food or drink unless medically advised to do so.27 The recommendations also stress the need to maintain hospital links with breastfeeding support groups to which new mothers can be referred after discharge.27

Strategies to Promote Breastfeeding in Gulf Cooperation Council Countries

According to the available literature, breastfeeding rates in GCC countries are suboptimal and achievement of the 50% universal exclusive breastfeeding goal set by the WHO poses a challenge in this region.7,10,12 Breastfeeding practices in GCC countries can be improved by adopting universal breastfeeding recommendations and integrating and implementing them using breastfeeding interventions and programmes with the support of policy-makers and community stakeholders. In order to achieve an increase in exclusive breastfeeding rates, it is essential that GCC countries look to one another’s experiences with breastfeeding promotion strategies.28 This regional collaboration should then be maintained while planning and implementing country-specific breastfeeding community programmes and initiatives.

In Saudi Arabia, the World Breastfeeding Trends Initiative has recommended government-led organisation of breastfeeding awareness campaigns targeting different populations in the community as well as the integration of breastfeeding education in the curricula of secondary schools and universities.29 Breastfeeding counselling was also advised, as well as the creation of breastfeeding-conducive spaces in public and at work to increase social acceptance of breastfeeding, perhaps through the establishment of ‘breastfeeding rooms’. Moreover, Saudi Arabian policymakers were encouraged to increase the number of days of paid maternity leave for new mothers and to introduce legislative controls over the marketing of formula/breast milk substitutes.30 Additionally, community awareness should be raised on the benefits of breast milk as compared to breast milk substitutes.

In Oman, the MOH has set an exclusive breastfeeding target rate of >90% to be achieved by 2025.18 In pursuit of this goal, it has been recommended that cultural and social barriers to breastfeeding specific to Oman should be taken into consideration during development and implementation of community breastfeeding programmes.28 For such programmes to be successful, researchers have stressed the importance of promoting awareness and knowledge of breastfeeding policies among Omani healthcare providers.28 In addition, the Omani MOH aims to introduce marketing regulations for formula and breast milk substitutes during the planning of a future exclusive breastfeeding initiative.18

In 2006, the Bahraini Breastfeeding Committee reported that the national decree implemented in 1995 regarding the marketing of breast milk substitutes had been violated.17,26 The Bahraini MOH subsequently took necessary action by ensuring all health centres were committed to the decree and increasing awareness of the importance of breastfeeding among healthcare practitioners by conducting lectures and regular meetings.17 This approach can be adopted by other GCC countries to control adherence to the WHO international guidelines for the marketing of breast milk substitutes.26 In the UAE, a community intervention plan has been identified as essential to promote breastfeeding in the country.20 Similarly, a health policy revision has been recommended in Kuwait to enable adequate breastfeeding training for healthcare providers, as well as to discourage use of formula feeding at hospitals.30 In addition, the quality of postnatal education should be improved, with breastfeeding support maintained after delivery and the current maternity leave period of 18 weeks extended so as to facilitate maternal commitment to continued breastfeeding practices.19

Another recommendation for improving exclusive breastfeeding rates in the GCC region is the promotion of BFHI-certified hospitals. In 2002, only six of 28 hospitals and birth institutions in Bahrain were certified as ‘baby-friendly’; recommendations were subsequently made to increase the number of BFHI hospitals in the ountry.17 Similarly, only six hospitals in the UAE have embraced BFHI policies.31 As in Bahrain, Emirati policy-makers have been encouraged to commit to universal breastfeeding recommendations by setting up a comprehensive national breastfeeding promotion plan.20 Implementation of BFHI policies needs to be encouraged throughout the GCC region.

Recommendations for Future Research in Gulf Cooperation Council Countries

There are several areas of potential research which should be conducted in the GCC region, such as the actual economic cost of suboptimal breastfeeding practices at the individual and national levels. In addition, there is currently a lack of comprehensive information regarding the determinants and indicators of breastfeeding practices in GCC countries. The majority of the current data describing breastfeeding practices and its determinants have not recently been updated and originate from individualised country-specific studies with a wide variety of methodologies. In addition, there is a lack of knowledge regarding detailed applications of recommendations to improve breastfeeding practices in GCC countries. Further in-depth cohort-driven research is needed to explore breastfeeding practices in this region.24 Future research should aim to identify variables associated with exclusive breastfeeding and assess knowledge among members of the public and health professionals regarding the benefits of breastfeeding and the risks associated with breast milk substitutes.

Moreover, more studies are necessary to describe actual breastfeeding practices in GCC countries in relation to international recommendations. In this regard, an assessment of common contributing barriers and facilitators of exclusive breastfeeding practices would be of great benefit. In addition, special attention should be given to correlations between infant morbidity and mortality rates and breastfeeding practices. National surveys should be carried out on a regular basis to provide current updates of indicators of breastfeeding and infant feeding statuses in each GCC country.

Conclusion

Exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life has wide-ranging health benefits for both the infant and mother. However, universal breastfeeding rates are suboptimal in GCC countries and many barriers to breastfeeding exist, including individual factors (e.g. maternal age, education level and getting pregnant again), sociocultural factors (e.g. negative perceptions of insufficient breast milk or breastfeeding in public), healthcare-related factors (e.g. a lack of well-trained specialists to provide breastfeeding support to new mothers) and workplace-related factors (e.g. short maternity leave allowances). As such, breastfeeding practices in this region can be enhanced by implementing policies that are supportive of optimal breastfeeding practices at the individual, family, community and governmental levels, as per the WHO and UNICEF recommendations.

References

- 1.Gartner LM, Morton J, Lawrence RA, Naylor AJ, O’Hare D, Schanler RJ, et al. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2005;115:496–506. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. The challenge. [Accessed: Mar 2017]. From: www.unicef.org/programme/breastfeeding/challenge.htm.

- 3.World Health Organization. Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: Part 1 - Definition. [Accessed: Mar 2017]. From: www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/9789241596664/en/

- 4.Lawrence RA, Lawrence RM. Breastfeeding: A guide for the medical profession. 7th ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA: Saunders; 2010. p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bai YK, Middlestadt SE, Peng CY, Fly AD. Psychosocial factors underlying the mother’s decision to continue exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months: An elicitation study. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2009;22:134–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2009.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ball TM, Wright AL. Health care costs of formula-feeding in the first year of life. Pediatrics. 1999;103:870–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Global nutrition targets 2025: Policy brief series. [Accessed: Mar 2017]. From: www.who.int/nutrition/publications/globaltargets2025_policybrief_overview/en/

- 8.Sankar MJ, Sinha B, Chowdhury R, Bhandari N, Taneja S, Martines J, et al. Optimal breastfeeding practices and infant and child mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104:3–13. doi: 10.1111/apa.13147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Victoria CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, França GV, Horton S, Kaseverc J, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387:457–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, Bhutta ZA, Christian P, de Onis M, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2013;382:427–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oot L, Sethuraman K, Ross J, Sommerfelt AE. The effect of suboptimal breastfeeding on preschool overweight/obesity: A model in PROFILES for country-level advocacy. [Accessed: Mar 2017]. From: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00MNT3.pdf.

- 12.United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. Nutrition: Current status and progress. [Accessed: Mar 2017]. From: data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/infant-and-young-child-feeding/#.

- 13.Victora CG, Horta BL, Loret de Mola C, Quevendo L, Pinheiro RT, Gigante DP, et al. Association between breastfeeding and intelligence, educational attainment, and income at 30 years of age: A prospective birth cohort study from Brazil. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e199–205. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70002-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Farsi YM, Al-Sharbati MM, Waly MI, Al-Farsi OA, Al- Shafaee MA, Al-Khaduri MM, et al. Effect of suboptimal breast-feeding on occurrence of autism: A case-control study. Nutrition. 2012;28:e27–e32. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stuebe A. The risks of not breastfeeding for mothers and infants. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009;2:222–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ayed AA. Knowledge, attitude and practice regarding exclusive breastfeeding among mothers attending primary health care centers in Abha city. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2014;3:1355–63. doi: 10.5455/ijmsph.2014.140820141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.International Baby Food Action Network. The Convention on the Rights of the Child: Report on the situation of infant and young child feeding in Bahrain. [Accessed: Mar 2017]. From: www.ibfan.org/art/IBFAN_CRC57-2011Bahrein.pdf.

- 18.Al-Ghannami S, Atwood SJ. National nutrition strategy: Strategic study 2014–2025. [Accessed: Mar 2017]. From: https://extranet.who.int/nutrition/gina/sites/default/files/OMN%202014%20National%20Nutrition%20Startegy.pdf.

- 19.International Baby Food Action Network. The Convention on the Rights of the Child: Report on the situation of infant and young child feeding in Kuwait. [Accessed: Mar 2017]. From: www.ibfan.org/CRC/IBFAN%20report%20_%2064_CRC%202013_Kuwait.pdf.

- 20.Radwan H. Patterns and determinants of breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices of Emirati mothers in the United Arab Emirates. BMC Pub Health. 2013;13:171. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Kohji S, Said HA, Selim NA. Breastfeeding practice and determinants among Arab mothers in Qatar. Saudi Med J. 2012;33:436–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rollins NC, Bhandari N, Hajeebhoy N, Horton S, Lutter CK, Martines JC, et al. Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet. 2016;387:491–504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Motee A, Ramasawmy D, Pugo-Gunsam P, Jeewon R. An assessment of the breastfeeding practices and infant feeding pattern among mothers in Mauritius. J Nutr Metab. 2013;2013:243852. doi: 10.1155/2013/243852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al Juaid DA, Binns CW, Giglia RC. Breastfeeding in Saudi Arabia: A review. Int Breastfeed J. 2014;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oman Ministry of Health. The second national PEM survey. [Accessed: Mar 2017]. From: www.cdscoman.org/uploads/cdscoman/Newsletter%2017-9pdf.

- 26.World Health Organization. International code of marketing of breast-milk substitutes. [Accessed: Mar 2017]. From: www.who.int/nutrition/publications/code_english.pdf.

- 27.World Health Organization, United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. Protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding: The special role of maternity services. [Accessed: Mar 2017]. From: www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/9241561300/en/

- 28.Sinai MA. Breastfeeding in Oman: The way forward. Oman Med J. 2008;23:236–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Breastfeeding Trends Initiative. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: 2012. [Accessed: Mar 2017]. From: www.worldbreastfeedingtrends.org/GenerateReports/report/WBTi-KSA-2012.pdf.

- 30.Dashti M, Scott JA, Edwards CA, Al-Sughayer M. Determinants of breastfeeding initiation among mothers in Kuwait. Int Breastfeed J. 2010;5:7. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-5-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radwan H. Thesis. Teesside University; Middlesbrough, UK: 2013. Influences and determinants of breastfeeding and weaning practices of Emirati mothers. [Google Scholar]