Significance

Tubulin is subject to diverse posttranslational modifications that constitute a code read by cellular effectors. Most of these modifications are catalyzed by tubulin tyrosine ligase-like (TTLL) family members. The functional specialization and biochemical interplay between TTLL enzymes remain largely unknown. Our X-ray structure of TTLL3, a tubulin glycylase, identifies two functionally essential architectural elements and illustrates how the common TTL scaffold was used to functionally diversify the TTLL family. We show that TTLL3 competes with the glutamylase TTLL7 for overlapping modification sites on tubulin, providing a molecular basis for the anticorrelation between these modifications observed in vivo. Our results illustrate how a combinatorial tubulin code can arise through the intersection of activities of TTLL enzymes.

Keywords: tubulin code, TTLL enzymes, glycylation, tubulin modification, glutamylation

Abstract

Glycylation and glutamylation, the posttranslational addition of glycines and glutamates to genetically encoded glutamates in the intrinsically disordered tubulin C-terminal tails, are crucial for the biogenesis and stability of cilia and flagella and play important roles in metazoan development. Members of the diverse family of tubulin tyrosine ligase-like (TTLL) enzymes catalyze these modifications, which are part of an evolutionarily conserved and complex tubulin code that regulates microtubule interactions with cellular effectors. The site specificity of TTLL enzymes and their biochemical interplay remain largely unknown. Here, we report an in vitro characterization of a tubulin glycylase. We show that TTLL3 glycylates the β-tubulin tail at four sites in a hierarchical order and that TTLL3 and the glutamylase TTLL7 compete for overlapping sites on the tubulin tail, providing a molecular basis for the anticorrelation between glutamylation and glycylation observed in axonemes. This anticorrelation demonstrates how a combinatorial tubulin code written in two different posttranslational modifications can arise through the activities of related but distinct TTLL enzymes. To elucidate what structural elements differentiate TTLL glycylases from glutamylases, with which they share the common TTL scaffold, we determined the TTLL3 X-ray structure at 2.3-Å resolution. This structure reveals two architectural elements unique to glycyl initiases and critical for their activity. Thus, our work sheds light on the structural and functional diversification of TTLL enzymes, and constitutes an initial important step toward understanding how the tubulin code is written through the intersection of activities of multiple TTLL enzymes.

Microtubules are multifunctional dynamic polymers essential in eukaryotic cells. Their basic building block is the α/β-tubulin heterodimer. It consists of a compact folded tubulin body and intrinsically disordered C-terminal tails. These tails form a dense lawn on the microtubule surface and serve as binding sites for molecular motors and microtubule-associated proteins (1). Tubulin tails are functionalized with abundant and chemically diverse posttranslational modifications that constitute an evolutionarily conserved tubulin code that specializes microtubule subpopulations in cells and tunes their interaction with effectors (2–6). The majority of these modifications are catalyzed by a phylogenetically widespread family of homologous enzymes whose members include tubulin tyrosine ligase (TTL) and multiple TTL-like (TTLL) enzymes that add either tyrosine, glutamate, or glycine to the tubulin tails (7–13) (reviewed in ref. 3). Understanding the structure and biochemical characteristics of these enzymes is essential to deciphering the tubulin code, as it is their collective action that gives rise to the stereotyped microtubule modification patterns observed in cells. Some of the most heavily modified microtubules are in the axonemes of cilia and flagella, organelles with critical roles in cell signaling, directed fluid flow, and cell motility (14, 15). Axonemal microtubules are particularly enriched in glycylation and glutamylation. Whereas glutamylation is found on both cytoplasmic and axonemal microtubules, glycylation is found almost exclusively in axonemes and thus thought to specifically tune microtubule functions in this specialized organelle (3).

Glycylation is the ATP-dependent addition of glycines, either singly or in chains, to internal glutamates (16). Tubulin glycylation is conserved in protists and most metazoans (17). The glycyl chain length on either α- or β-tubulin tails in axonemes is highly variable (16–18), ranging from 1 to 40 posttranslationally added glycines (19). Of the 13 TTLL enzymes in mammals (10, 11), three are glycylases: TTLL3, -8, and -10 (12, 13, 20). Cellular overexpression studies suggest that these enzymes are specialized for either initiating (TTLL3 and TTLL8) or elongating the glycyl chain (TTLL10) (12, 20). Such specialization would not be surprising, as initiation requires the enzyme to accommodate a glutamate and an incoming glycine in its active site and catalyze formation of an isopeptide bond, whereas elongation requires it to accommodate two glycines and catalyze a standard peptide bond.

Glycylation is critical for the stability of primary (21) and motile cilia (22). TTLL3 loss decreases numbers of ciliated colon epithelial cells (21), and loss of both TTLL3 and -8 reduces primary cilia stability and leads to motile cilia loss (22). In mice, loss of TTLL3-mediated glycylation in colon epithelial cells results in increased cell proliferation and the potentiation of cancerous cell growth (21). Consistent with this phenotype, TTLL3-inactivating mutations have been identified in colon cancer patients (12, 23). Glycylation is also important during development. Knockdown of TTLL3 in developing zebrafish embryos causes pronephric kidney cysts, randomized multicilia orientation, and defects in ciliary fluid flow (13, 24), whereas knockout of TTLL3B is lethal in flies (12).

All glycylase studies have been so far performed in vivo (13, 24). Their mechanistic interpretation is complicated by their apparent functional redundancy and the complexity of microtubule modifications in vivo. Thus, despite the importance of glycylation in regulating basic cellular processes, a biochemical and structural framework to understand the activities of TTLL glycylases is lacking. Here we focus on the mechanistic dissection of TTLL3 and show that it strictly initiates glycyl chains on the β-tubulin tail using a positional hierarchy. Moreover, we find that TTLL3 competes with the glutamylase TTLL7 for overlapping modification sites on the β-tail, providing a molecular basis for the anticorrelation between glutamylation and glycylation observed in vivo (12, 25, 26). Consistent with this competition for modification sites, TTLL3 activity is reduced on glutamylated versus unmodified microtubules. Surprisingly, we find that TTLL3 can switch substrate preference in a glutamylation-dependent manner. Finally, to understand what architectural elements distinguish TTLL glycylases from glutamylases, we determined the X-ray crystal structure of TTLL3 to 2.3-Å resolution. This structure revealed two structural elements and a sequence motif unique to glycyl initiases that we show are critical for their activity.

Results

TTLL3 Preferentially Initiates Glycyl Chains on β-Tubulin Tails Following a Positional Hierarchy.

Cellular studies using antibodies that recognize monoglycylated tubulin indicate that TTLL3 is a glycyl chain initiator capable of modifying both α- and β-tubulin (12, 13). We find that recombinant TTLL3 preferentially glycylates a β-tail peptide over the α-tail (Fig. 1A). This preference also holds with microtubules (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1), indicating that the TTLL3 active site is specific for the β-tail. At higher enzyme-to-substrate ratios or longer incubations, the α-tubulin tail is minimally modified by TTLL3, indicating that this specificity is limited, consistent with cellular overexpression studies showing glycylation of both α- and β-tubulin (12).

Fig. 1.

TTLL3 is a glycylation-initiating enzyme that modifies the β-tubulin tail. (A) Deconvoluted mass spectra of a synthetic C-terminal α1B- (Left) and βI-tubulin peptide (Right) glycylated by TTLL3 at a 1:20 enzyme:peptide molar ratio. Unmodified peptides at t 0 h, black; peaks corresponding to glycylated products, green and blue for α1B and βI, respectively. The Gly number added to each species is indicated. (B) Deconvoluted α- and β-tubulin mass spectra of Taxol-stabilized human microtubules (MTs) glycylated by TTLL3 at a 1:20 enzyme:tubulin molar ratio. The Gly number added is indicated and colored according to isoform. * and ** indicate Na+ and (N2FeOH)1+ adducts generated during LC/MS, respectively (46). (C) Reverse-phase LC/MS of TTLL3-modified human naïve microtubules tracking the normalized m/z intensity of individual βI-tubulin glycylated species over time (SI Materials and Methods). Mean ± SEM (n = 3). (D) Hierarchy of TTLL3 glycylation on the βI-tubulin tail from MS/MS experiments (Materials and Methods).

Fig. S1.

TTLL3 glycylation time course with microtubule and synthetic βI-tubulin peptide substrates monitored via reverse-phase LC/MS. (A) Chromatogram (220 nm) of Taxol-stabilized human naïve microtubules modified by TTLL3 at a 1:10 ratio and separated via reverse-phase LC/MS. Note that all β-tubulin isoforms coelute during reverse-phase separation. mAu, absorbance units. (B) Deconvoluted LC/MS spectra showing the raw intensity of each species during the time course (t = 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 18, and 24 h). Two representative spectra (blue and red) are shown for each time point. Only βI-tubulin species are labeled, as only their intensities were tracked during the reaction. (C) Reverse-phase LC/MS analysis of TTLL3 glycylated synthetic βI-tubulin tail peptide modified at a 1:10 ratio tracking the normalized m/z intensity of individual glycylated βI-tubulin peptide species over time (SI Materials and Methods). Values are mean ± SEM (n = 4). (D) Deconvoluted LC/MS spectra showing the raw intensity of each peptide species during the time course (t = 0, 0.75, 1.5, 3, 6, 9, 17.5, and 24 h). Two representative spectra are shown for each time point.

We then mapped glycylation sites on TTLL3-modified microtubules using tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). We used as substrate microtubules assembled from unmodified human tubulin purified via an affinity method from tSA201 cells (27, 28) (SI Materials and Methods). We monitored reaction progression by LC/MS (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1B). The LC/MS analysis showed a gradual depletion of the unmodified species concomitant with an increase in the monoglycylated species, and at longer time points the conversion from lower- to higher-order glycylated species with as many as four added glycines (Fig. 1C). Mapping of TTLL3 glycylation sites on the βI-tail [βI is one of the two major β-tubulin isoforms in tSA201 cells and also found in axonemal microtubules (29)] revealed a hierarchy of modification sites (Fig. 1 and Fig. S2). The primary modification site is E441 (Fig. S2 A and E). This site is followed by E438 and E442, yielding two diglycylated species of roughly equal abundance as revealed by extracted-ion chromatograms (XICs) (Fig. S2 B and F), followed by E439 (Fig. 1 and Fig. S2C). MS/MS, MS/MS/MS, as well as electron transfer dissociation experiments did not detect elongated glycine chains even at extended incubation times and higher enzyme:substrate ratios, indicating that TTLL3 is indeed a glycyl chain-initiating enzyme (SI Materials and Methods). The TTLL3-modified sites we identify concentrate on the last five glutamates in βΙ, previously found to be glycylated in β-tubulin isolated from Paramecium tetraurelia (30) and Purpurus lividus (31).

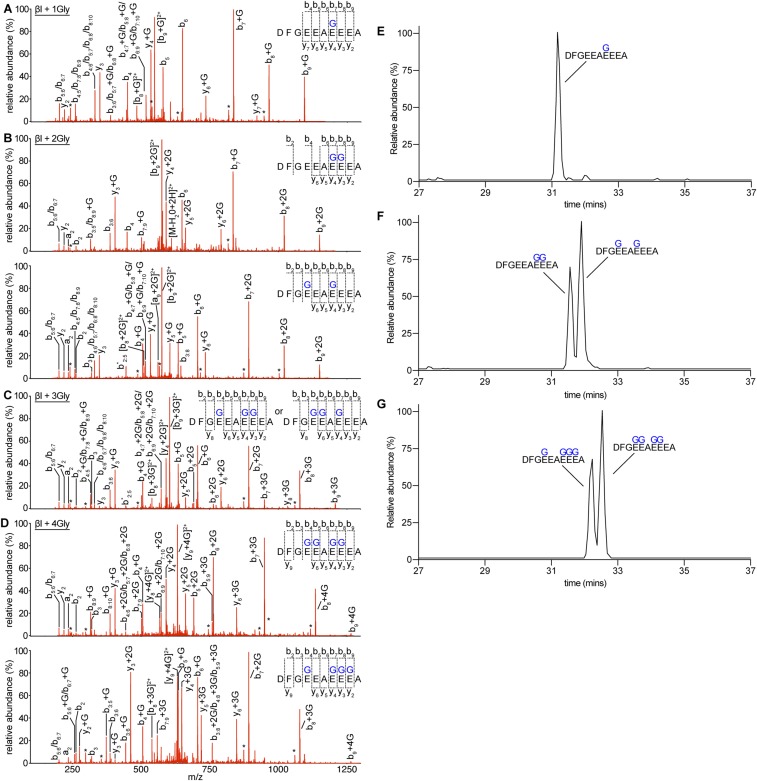

Fig. S2.

MS/MS sequencing of tubulin C-terminal tails proteolytically released from microtubules glycylated by TTLL3. MS/MS sequencing of Asp-N–released C-terminal naïve human microtubule tails glycylated by X. tropicalis TTLL3. (A) Monoglycylated species. (B) Diglycylated species. (C) Triglycylated species. (D) Tetraglycylated species. Individual a-, b-, and y-series ions for each spectrum are indicated, as is the deduced amino acid sequence. Asterisks indicate ions with a neutral loss of an H2O group. All possible species are listed for ions whose mass does not allow for unambiguous deduction of amino acid sequence. Two triglycylated species, DFGEEAEEEA and DFGEEAEEEA (glycylation sites are indicated in bold), coeluted during reverse-phase separation and could not be separated into individual spectra. For clarity, we list the added Gly numbers next to the y and b ions as +n Gly, where n is the number of glycines on that particular ion species. (E) Extracted-ion chromatogram of Asp-N–released monoglycylated tail peptides showing predominantly a single species modified at E441. (F) XIC of Asp-N–released diglycylated tail peptides showing two distinct species, modified at either E438/E441 or E441/E442. (G) XIC of Asp-N–released tetraglycylated tail peptides showing two distinct species, modified at either E438/E441/E442/E443 or E438/E439/E441/E442 (see Materials and Methods for further details).

TTLL3 and 7 Target Overlapping Glutamates in the β-Tubulin Tail.

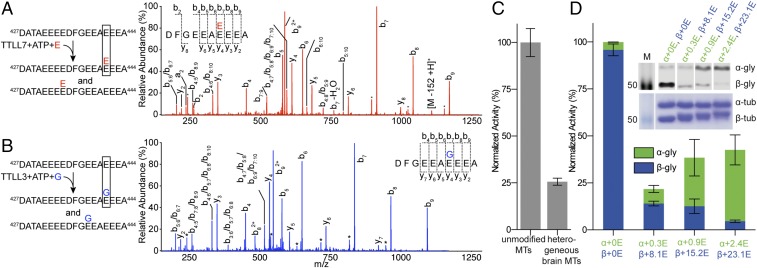

Competition for substrate between glutamylases and glycylases has been proposed as a regulatory mechanism (13, 26, 32) because inhibition or overexpression of glutamylases causes marked increases or decreases in glycylation and vice versa (13). To test this hypothesis, we used MS/MS to sequence the βI-tubulin tails from microtubules glutamylated by TTLL7, a β-tubulin–specific glutamylase that initiates and elongates glutamate chains (33). Both TTLL3 and TTLL7 localize to cilia (10, 13). These MS/MS experiments are challenging, because the high glutamate numbers in the tubulin tails make it hard to distinguish between main-chain and posttranslationally added glutamates in fragmentation patterns. To overcome this problem, we used heavy, [13C]Glu as substrate for TTLL7 (SI Materials and Methods). We found two main glutamylation sites in βI: E434 and E441 (Fig. 2A and Fig. S3 B and C). E442 and E443 were also modified, but with much lower frequency (<1% as determined from XICs). Thus, our MS/MS experiments indicate that TTLL3 competes with TTLL7 for its main modification site E441 (Fig. 2 A and B).

Fig. 2.

TTLL3 and TTLL7 compete for overlapping sites on the β-tubulin tail. (A) MS/MS spectrum of a βI-tubulin tail peptide fragment proteolytically released from microtubules glutamylated by TTLL7 showing glutamylation at E441. Individual a-, b-, and y-series ions for each spectrum are shown together with the deduced sequence. Asterisks indicate ions with neutral loss of an H2O group. The annotation i:j represents a fragment from internal cleavage; for example, b4:7 represents the peptide fragment from the fourth to the seventh residue. All possible species are listed when different fragments have the same mass. (B) MS/MS spectrum of a βI-tubulin tail peptide fragment proteolytically released from microtubules glycylated by TTLL3 showing glycylation at E441 (annotated as in A). (C) Normalized glycylation activity of TTLL3 on unmodified and heterogeneous brain microtubules. Mean ± SEM (n = 3). (D) Normalized TTLL3 glycylation activity of TTLL3 on unmodified and glutamylated microtubules. Mean ± SEM (n = 2). The weighted average of glutamates added to α- and β-tubulin is indicated. (D, Inset) Western blot of the 3-h time point of each reaction probed with the monoglycylation-specific TAP952 antibody (Top) and Coomassie-stained SDS/PAGE of glutamylated microtubules used as substrates (Bottom).

Fig. S3.

MS/MS sequencing of tubulin C-terminal tails proteolytically released from microtubules glutamylated by TTLL7. (A) Reverse-phase LC/MS analyses of TTLL7-modified Taxol-stabilized human microtubules. Deconvoluted α- and β-tubulin mass spectra after 0- and 1-h incubation with TTLL7 at a 1:10 enzyme:tubulin molar ratio. The weighted average of glutamates added is indicated and colored according to isoform. (B and C) MS/MS sequencing of Asp-N–released microtubule tails glutamylated by X. tropicalis TTLL7. Individual a-, b-, and y-series ions for each spectrum are indicated, as is the deduced amino acid sequence. Asterisks indicate ions with a neutral loss of an H2O group. All possible species are listed when different fragments have the same mass.

Tubulin used in most biochemical studies is isolated from brain tissue because of its abundance and ease of purification. This tubulin is diversely posttranslationally modified and especially enriched in polyglutamylation [average Glu number ranging from 3 to 6 with as many as 11 and 7 on α- and β-tails, respectively (34)]. E441, the primary site modified by TTLL3, is glutamylated in mouse brain tubulin (35). Consistent with this finding, TTLL3 is 75% less active with heterogeneous brain microtubules compared with unmodified human microtubules (Fig. 2C). We next systematically investigated the effect of glutamylation on TTLL3 glycylation by performing activity assays with microtubules with quantitatively defined glutamylation levels generated through in vitro enzymatic modification of unmodified human microtubules using TTLL7 (4) (Fig. 2D and SI Materials and Methods). TTLL3 glycylation was reduced by 86% with microtubules carrying a weighted average <E> of 8.1 glutamates on their β-tails compared with unmodified microtubules. Further increase in glutamylation levels (<E> 15.2 and 23.1, respectively) resulted in only a modest decrease in β-tubulin glycylation (87 and 95%, respectively). This leveling off is likely due to a saturation of TTLL3 modification sites by TTLL7 and the fact that the additional glutamates added at higher glutamylation levels are on non-TTLL3 sites. These results show a direct competition between a TTLL glutamylase and glycylase for the same modification sites on tubulin and provide a mechanistic explanation for the anticorrelation between these modifications observed in vivo.

Interestingly, TTLL3 gradually switches to modify the α-tail as β-tubulin glutamylation levels increase and presumably the TTLL3 initiation sites on this tail have already been glutamylated: α-Tubulin glycylation increases ∼10-fold on microtubules with higher glutamylation levels (α+2.4E, β+23.1E) (Fig. 2D). TTLL3 localizes to axonemes. These cellular structures contain the highest levels of glutamylation reported in vivo (as many as 21 glutamates) (36, 37). Moreover, in vivo studies indicate that most glycylation on ciliary microtubules occurs after glutamylation, with glyclation being required for cilia maintenance and glutamylation for their biogenesis (22). Our data demonstrate that TTLL3 can display glutamylation-dependent tubulin-tail preference.

TTLL3 Crystal Structure: A Variation on the TTL Theme.

The structure of the glutamylase TTLL7 (38) revealed how sequence elements specific to glutamylases differentiate the conserved TTL scaffold (39, 40). To elucidate what architectural features specialize the TTL fold for glycylation, we determined the X-ray crystal structure of the conserved core of Xenopus tropicalis TTLL3 (residues 6–569) bound to the slowly hydrolyzable ATP analog AMPPNP (Fig. 3 and Fig. S4) using single-wavelength anomalous dispersion (Materials and Methods). This core construct is active (2.7 ± 0.2 Gly per h) and its activity is comparable to the full-length enzyme (Fig. S4D and SI Materials and Methods). The structure was refined at 2.3-Å resolution to an Rfree of 23.0% (Table S1). Two molecules of TTLL3 are present in the asymmetric unit of our crystals (Fig. S4B); however, size-exclusion chromatography shows the protein is monomeric in solution (Fig. S4C). Structural variation between the two chains is low (rmsd 0.29 Å over all Cα atoms; Fig. S4E). TTLL3 is elongated (∼94 × 47 × 23 Å3) and composed of an N (residues 6–138), central (residues 139–377), and C domain (residues 378–569) (Fig. 3A). A central mixed-polarity β-sheet supports the active site, which lies at the junction of the three domains. The C-domain strand β13 reaches into the N domain and bridges the β-sheets in these domains to form a continuous, highly curved β-sheet that bisects TTLL3. The nucleotide is wedged between the central and C domains (Fig. 3A). Despite the presence of AMPPNP in our crystals, the γ-phosphate is not well-localized, possibly because of the absence of the tubulin substrate, as seen previously for TTLL7 (38) (Fig. S4F).

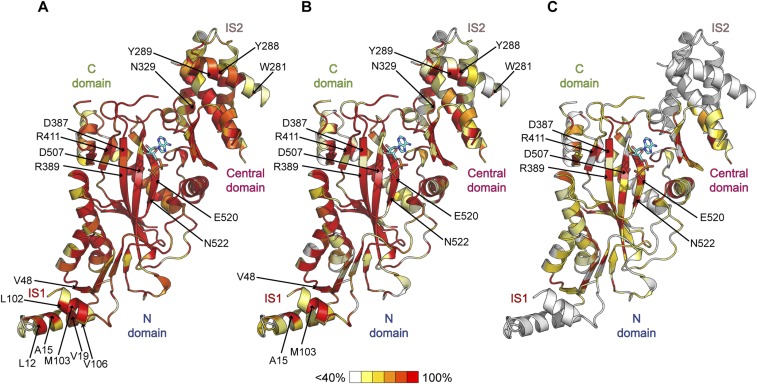

Fig. 3.

TTLL3 crystal structure and comparison across the TTLL family. (A) Cartoon representation of the TTLL3 core bound to AMPPNP. (B) Close-up of the interface between IS2 α7 and central domain α5. (C) Close-up showing interactions between IS1 α1 and α3. (D) X-ray crystal structure of TTL [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 4IHJ]. (E) Hybrid X-ray and cryo-EM structure of TTLL7 [PDB ID code 4YLS, Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMD) ID code EMD-6307]; the cMTBD atomic model (gold) is based on the EM map and is incomplete. Nucleotides are in ball-and-stick format. Spheres indicate disordered segments.

Fig. S4.

X-ray crystal structure of TTLL3. (A) Stereoview of a section of the electron density at 1σ after single-wavelength anomalous dispersion phasing and density modification. Shown is a section of X. tropicalis TTLL3 centered on helix α11. Additional electron density attributable to EMP-modified Cys150 is indicated. (B) Asymmetric unit dimer of TTLL3. (C) Gel-permeation chromatogram of X. tropicalis TTLL3 (residues 6–569, E520Q). Approximately 3 mg of protein was separated on a Superdex 75 column (10/300) in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7), 200 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM TCEP. (C, Inset) Protein standards under the same buffer conditions. Vo, void volume; Vt, total column volume. (D) Normalized in vitro glycylation activity of TTLL3 residues 6–569, 6–592, and 1–830. The 1–830 construct was purified from HEK293 cells. Error bars represent SEM (n = 3). (E) Alignment of the two TTLL3 copies in the asymmetric unit. (F) Close-up view of the active site of TTLL3 showing Fo − Fc (gray mesh; σ2.5) and 2Fo − Fc omit map electron density (orange mesh; σ2.5) before modeling the nucleotide. AMPPNP with the γ-phosphate unresolved is shown in ball-and-stick representation.

Table S1.

Crystallographic data and refinement statistics

| TTLL3 (EMP) | TTLL3 (native) | |

| Data collection | ||

| Space group | P21 | P21 |

| Cell dimensions | ||

| a, b, c, Å | 57.7, 191.3, 60.46 | 58.6, 192.2, 60.74 |

| α, β, γ, ° | 90, 116.2, 90 | 90, 114.3, 90 |

| Wavelength | 0.9774 (HER) | 0.9777 |

| Resolution, Å | 45.0–3.20 (3.26–3.2) | 50.0–2.28 (2.32–2.28) |

| Rsym | 16.3 (>100) | 7.7 (50.8) |

| Rpim | 3.2 (33.4) | 4.6 (32.7) |

| I/σI | 20.8 (1.5) | 16.4 (1.5) |

| Completeness, % | 100 (99.5) | 97.4 (75.6) |

| Redundancy | 35.7 (29.5) | 3.7 (3.0) |

| Phasing figure of merit | 0.47 | |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution, Å | 48.49–2.28 | |

| No. of reflections | 53,787 | |

| Rwork/Rfree | 20.0//23.0 | |

| No. of atoms | ||

| Protein | 6,232 | |

| Ligand/ion | 64 | |

| Water | 253 | |

| B factors | ||

| Protein | 58.3 | |

| Ligand | 163.31 | |

| Water | 48.6 | |

| Rms deviations | ||

| Bond lengths, Å | 0.005 | |

| Bond angles, ° | 0.770 | |

| Coordinate error | 0.28 | |

| Ramachandran | ||

| Favored, % | 97.41 | |

| Disallowed, % | 0 |

Values in parentheses correspond to the highest resolution shell.

The TTLL3 core is structurally homologous to TTL (40) (all-Cα rmsd 1.7 Å; Fig. 3 A and D). However, TTLL3 has two additional structural elements, designated IS1 and IS2 (Fig. 3 and Fig. S5). IS1 is composed of two helices, α1 and α3, the first an N-domain extension and the latter an insertion between β2 and β3 (Fig. 3 A and D and Fig. S5). α3 is stabilized by knobs-in-holes apolar interactions with α1 and β2 of the N domain (Fig. 3C). IS2 is a 138-residue insertion that extends the central-domain helix α5 and completes a four-helix bundle comprising α5 through α8 (Fig. 3 A and B and Fig. S5). Helices α6, -7, and -8 of IS2 are stabilized through extensive hydrophobic interactions: Invariant W281 of α7 stacks against W188 of α5; invariant Y288 and Y289 of α7 make van der Waals and polar contacts with α5, α9, and the α8–β6 loop (Fig. 3B). Both IS1 and IS2 are critical for TTLL3 activity (see below). The TTLL3 structure is distinct from that of the glutamylase TTLL7, composed of the TTL core augmented by an α-helical cationic microtubule-binding domain (Fig. 3E) (38).

Fig. S5.

Alignment of TTLL3 and TTLL8 sequences. Secondary structure elements are indicated above the corresponding sequence. α-helices, cylinders; β-strands, arrows; random coil, lines. Segments of TTLL3 not built due to poorly resolved electron density are denoted by dashed lines. Sequence identity is color-coded using a gradient from white (below 40%) to red (100%). Residues involved in nucleotide binding are denoted by an asterisk; residues critical for activity are indicated by a red X. The red arrow indicates an autoglycylation site in TTLL3 identified by MS/MS sequencing. Residues involved in the formation of a π-helix are denoted by Π. Mutations in TTLL3 associated with colon cancer (23, 41) are indicated in red above their respective positions; inactivating mutations (12) in the human elongating glycylase TTLL10 are colored gray.

Molecular Determinants for Microtubule Recognition by TTLL3.

The TTLL3 molecular surface displays two conserved positively charged interconnected regions: one extending from the ATP binding site to the N-, central-, and C-domain junction, and the second from the tip of IS1 to the posterior surface of the C domain (Fig. 4 A and B). This extended surface is likely a site of interaction with the negatively charged tubulin tails and microtubule surface. The active site is lined with basic residues conserved in all TTL and TTLL enzymes. Invariant R411 stabilizes the ATP γ-phosphate in TTL (39, 40) (Fig. 4 A and C). R389 is also invariant. Its equivalent residue in TTL coordinates the tubulin-tail glutamate that ligates to the incoming tyrosine (39). Consistent with their importance in substrate binding, R389E and R411E mutations in TTLL3 reduce glycylation to background levels (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, G505 (G597 in humans) is mutated to serine in colorectal cancer patients (12, 23, 41). This mutation would cause a steric clash with R389, likely affecting ATP binding. Another disease mutation is M527I (M619 in humans). This residue is involved in conserved hydrophobic interactions that stabilize the α12–β14 loop that wraps the active site (Figs. 3A and 4 A and B). Both disease mutations inactivate TTLL3 (12).

Fig. 4.

Molecular determinants of microtubule glycylation by TTLL3. (A) TTLL3 molecular surface colored according to conservation (red, 100% identity; white, <40%). (B) TTLL3 molecular surface colored according to electrostatic potential (red, negative; blue, positive; from −7 to +7 kBT). IS2 residues D265–D267 are not resolved in our structure. (C) TTLL3 structure showing residues important for glycylation. Residues at the proposed microtubule-binding interface are shown in aqua; those in the active site and tubulin tail-binding groove are shown in orange. IS1 and IS2 are in red and violet, respectively. Disordered regions are shown as spheres. (D) Normalized in vitro glycylation activity of recombinant structure-guided TTLL3 mutants with unmodified human microtubules. Activity was measured by Western blot using the TAP952 anti-monoglycylated tubulin antibody (SI Materials and Methods). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ****P < 0.0001. Mean ± SEM (n ≥ 6).

Conserved K119, R126, and K139 located toward the N- and central-domain interface are important for substrate recognition, as their mutation decreases activity dramatically (Fig. 4 C and D). Previous studies established this surface as important for tubulin-tail recognition by TTL (40) and TTLL7 (38), and it thus likely constitutes the binding platform for the tubulin tail in TTLL3 also. Because these surface residues are >20 Å from the active site, they are likely involved primarily in substrate binding and not chemistry. Invariant S142 is also in this region. MS/MS sequencing of our recombinant TTLL3 revealed it was partially phosphorylated during expression in insect cells (SI Materials and Methods). In vitro dephosphorylation increased activity approximately twofold, as did mutation to Ala, whereas a phosphomimetic S142D mutation reduced activity to background (Fig. 4D). Thus, phosphorylation at this site could potentially regulate TTLL3. This serine is in a weak consensus site for PKA and PKC (42).

The convex ridge of TTLL3 running from the tip of IS1 α1 to the N- and central-domain junction is studded with conserved positively charged residues likely involved in microtubule binding (Fig. 4C). Consistent with their high degree of conservation, double mutation of K13A K16A and K24A K26A leads to 61 and 96% lower glycylation, respectively (Fig. 4D). Single charge-reversal mutation of invariant K130, R556, and K568 reduces activity by 85, 63, and 50% compared with wild type, respectively. This positively charged ridge is bordered by a hydrophobic patch formed by invariant W158 and F159 (Fig. 4C and Fig. S6) that are solvent-exposed and likely also involved in substrate interactions. Their mutation reduces activity by 98 and 97%, respectively (Fig. 4D).

Fig. S6.

TTLL3 surface colored according to conservation and electrostatic potential. (A) Surface representation of TTLL3 (rotated 90° compared with the view in Fig. 4A) colored according to conservation among TTLL3 isoforms (red, 100% conservation; white, <40%). Arrows indicate residues important for glycylation. (B) TTLL3 molecular surface (rotated 90° compared with the view in Fig. 4B) color-coded according to electrostatic potential (red, negative; blue, positive; from −7 to +7 kBT).

Glycyl Initiases TTLL3 and 8 Share Common Architectural Elements Critical for Activity.

TTLL3 is conserved from ciliated protists to humans (Fig. S5) and most closely related to TTLL8, also a glycyl chain-initiating enzyme (12). The enzymatic cores of the two proteins are ∼49% identical (68% similarity; Fig. S5), with both surface as well as hydrophobic core residues strongly conserved (Fig. 5A and Fig. S7B). Our structure-based sequence analysis shows that TTLL8 contains both IS1 and IS2, and the TTL core surfaces that interact with these elements are conserved (Fig. 3 B and C and Figs. S5 and S7 A and B). Structure-based bioinformatic analysis did not uncover these elements in any other TTLL family member. TTLL3 has lower overall similarity to TTLL10 (25% identity, 45% similarity), the only TTLL enzyme thought to be a glycine-chain elongator. Importantly, IS1 and IS2 are absent in TTLL10. Thus, our structural and functional analyses demonstrate that IS1 and IS2 are defining structural elements of TTLL enzymes that initiate glycyl chains.

Fig. 5.

TTLL3 and TTLL8 share structural elements critical for glycylation. (A) The TTLL3 molecular surface is colored according to conservation across TTLL3 and TTLL8s as in Fig. 4A. Arrows indicate TTLL8 residues important for glycylation. Residues D328–D330 are not resolved in our structure (SI Materials and Methods); their approximate position is indicated by an arrow. (B) Normalized glycylation activity of GFP-tagged wild-type mouse TTLL8 and site-directed mutants as determined by quantifying the glycylation signal from immunofluorescence in U2OS cells (SI Materials and Methods; n ≥ 50 cells for each construct; error bars show SEM; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001). (C) Sequence alignment of TTLL3 and TTLL8 showing conservation of the IS2 DID motif. Cm, Chelonia mydas; Dr, Danio rerio; Hs, Homo sapiens; Mm, Mus musculus; Sc, Struthio camelus australis; Xt, X. tropicalis. (D) Cellular distribution (green) and glycylation activity (red) of GFP-tagged wild type and IS2 mutants transiently transfected in U2OS cells. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (D, Insets) (Magnification, 2.5×.)

Fig. S7.

Conservation across TTLL glycylases. (A) Cartoon representation of the TTLL3 structure, colored according to sequence similarity (4) among TTLL3 isoforms. Gradient from red (100% conserved) to white (<40%). (B) As in A, but colored according to conservation between the TTLL3 and -8 isoforms. (C) As in A, but colored according to conservation among TTLL3, -8, and -10. Active-site residues conserved in TTLL3, -8, and -10 are indicated, as are residues important for the structural integrity of IS1 and IS2.

All key residues important for TTLL3 activity are conserved in TTLL8s (Fig. 5 and Figs. S5 and S7), including residues that line the proposed tubulin tail (K185, H192, K205, and S208) and microtubule-binding interfaces (K93, R96, K104, R106, W224, Y225, R619, and R631). Charge-reversal mutation of K185, H192, and K205 in TTLL8 reduces its activity in cells by 98, 64, and 93% of wild-type levels, respectively (Fig. 5B). Residues on the positively charged microtubule-binding ridge are also strongly conserved between TTLL3 and -8. Double charge-reversal mutations K93E R96E and K104E R106E both reduce activity by 99%, whereas single mutations R619E and R631E reduce activity by 75 and 74%, respectively. As in TTLL3, this positively charged ridge is flanked by a conserved hydrophobic patch containing invariant W224 and Y225. Their mutation reduces glycylation dramatically (Fig. 5B).

The flexible loop connecting α6 and α7 of IS2 extends the convex interaction ridge on TTLL3. It contains a conserved DID sequence motif (Fig. 5C) present in all TTLL3s and 8s but absent in TTLL10 enzymes, consistent with a specialization for glycyl initiases. Mutation of the two conserved aspartates (D265N D267N) reduces glycylation by 98% in vitro (Fig. 4D), and human bone osteosarcoma epithelial cells (U2OS) expressing this mutant show no detectable glycylation (Fig. 5D). Mutation of this motif in TTLL8 (D328N D330N) reduces activity to 20% of wild-type levels (Fig. 5B). Thus, this signature sequence motif is critical for the activity of TTLL glycyl initiases.

SI Materials and Methods

Protein Expression and Purification.

Xenopus tropicalis TTLL3 (residues 6–569) was expressed with a cleavable N-terminal 6× His affinity tag in High Five cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using baculovirus. Cells were lysed by sonication, and cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 164,700 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. TTLL3 was purified by Ni-NTA affinity. The affinity tag was removed by incubating with Tev protease at 4 °C for 4 h, and the protein was dephosphorylated by incubation with lambda protein phosphatase (1:50 molar ratio). TTLL3 was further purified on a MonoQ anion-exchange column (GE Healthcare) followed by hydrophobic and size-exclusion chromatography. The protein was monodisperse and eluted as a single peak from a Superdex 75 size-exclusion chromatography column (Fig. S4C). Purity and integrity of TTLL3 constructs were verified by mass spectrometry, and measured masses agreed with predicted masses within 1 Da. Mutagenesis was performed using QuikChange (Stratagene).

Mass Spectrometry-Based Peptide and Microtubule Glycylation Assays.

Synthetic α- and β-tubulin C-terminal peptides (α1B-tubulin sequence: VDSVEGEGEEEGEEY; βI-tubulin sequence: Ac-DATAEEEEDFGEEAEEEA; Bio-Synthesis) were incubated with recombinant TTLL3 at room temperature at a 1:20 molar ratio of enzyme to peptide (2.5 μM TTLL3, 50 μM peptide) in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7), 10 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), 1 mM ATP, and 1 mM l-glycine. Reactions were quenched by addition of an equal volume of 10% acetonitrile with 0.1% TFA and separated on a Zorbax 300SB C18 column (Agilent) using a 0–70% acetonitrile gradient in 0.05% TFA at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. The column was attached in-line with a 6224 ESI-TOF LC/MS (Agilent). Data were analyzed using the MassHunter Workstation platform (Agilent). To determine the rates at which the βI-peptide substrate was glycylated (Fig. S1 C and D), the peptide was modified at a 1:10 ratio of enzyme to substrate (5 μM TTLL3, 50 μM peptide) under the same conditions as listed above, and aliquots were removed at t = 0, 0.75, 1.5, 3, 6, 9, 18, and 24 h. The m/z signal intensity of each species (0G, +1G, +2G, +3G, +4G) was monitored as a function of time and normalized to the m/z intensity of the unmodified peptide at t = 0 h. The recombinant TTLL3 was used as an internal loading standard, as it elutes separately from the tubulin peptides. Raw spectra from two independent reactions can be seen in Fig. S1D.

Tubulin from tSA201 cells was purified via the tubulin-binding tumor overexpressed gene (TOG) domain affinity method (27, 28) and polymerized into microtubules as previously described (27). Mass spectrometric analysis detected no posttranslational modifications on this tubulin (Fig. 1 and Figs. S1B and S3A). TTLL3 was incubated at room temperature with 10 μM unmodified human microtubules at a 1:20 molar ratio of enzyme to substrate in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7), 10 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM TCEP, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM l-glycine, and 20 μM Taxol. Aliquots (5 μL) were removed at t = 0, 2, and 4 h, and quenched with an equal volume of 10% acetonitrile, 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and subjected to electrospray mass spectrometry as described (4, 27). To determine the rates at which the unmodified microtubule substrate was glycylated (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1 A and B), unmodified human microtubules were modified at a 1:10 ratio of enzyme to substrate (1 μM TTLL3, 10 μM microtubules) under the same conditions as described above, and aliquots were removed at t = 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 18, and 24 h. The m/z signal intensity of each species (0G, +1G, +2G, +3G, +4G) was monitored as a function of time and normalized to the m/z intensity of the unmodified species at t = 0 h. An internal peptide standard (DATAEEEGEF; Bio-Synthesis) that eluted separately from both TTLL3 and α- and β-tubulin was added after the reaction was completed and just before mass spectrometric analysis to serve as a loading standard (Fig. S1A). Raw spectra from two independent reactions can be seen in Fig. S1B.

MS/MS Analyses of Glycylated and Glutamylated Peptides.

TTLL3 was incubated with Taxol-stabilized unmodified human microtubules at room temperature (1 μM TTLL3, 10 μM microtubules) in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7), 10 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM TCEP, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM l-glycine, and 20 μM Taxol for 18 h. The reaction was quenched by the addition of an equal volume of SDS/PAGE loading buffer. Glycylated tubulin (2.5 μg) was separated by SDS/PAGE using a 4 to 12% Bis-Tris Plus gel (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The tubulin bands were excised and reduced with 20 μL 10 mM TCEP at room temperature for 1 h. We experimented with different methods of proteolyzing the C-terminal tails of tubulin. We studied the peptides generated by trypsin, chymotrypsin, and Asp-N and found that by digesting with Asp-N the very C terminus of βI-tubulin was effectively cut and a short peptide (DFGEEAEEEA) was generated that is amenable to good fragmentation studies. After removing the TCEP solution, samples were alkylated with N-ethylmaleimide and digested with Asp-N (1:20 ratio of protease to substrate) at 37 °C overnight. Digests were extracted from the gel and desalted on a Waters Oasis HLB μElution plate before LC/MS/MS analysis. A Thermo Fisher Scientific Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer coupled with a 3000 Ultimate HPLC was used for LC/MS/MS data acquisition. Samples were separated with mobile phase A (MPA), 98% H2O, 0.1% formic acid, and mobile phase B (MPB), 98% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid, and gradient 0 min, 2% MPB, 30 min, 27% MPB, 37 min, 50% MPB, 40 min, 80% MPB. The Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer was operated in positive nanoelectrospray mode. The resolution of the survey scan was set at 60k at m/z 400 with a target value of 1 × 106 ions. The m/z range for MS scans was 300 to 1,600. The MS/MS data were acquired in data-dependent mode with an isolation window of 2.0 Da. The top 10 most abundant ions were selected for product ion analysis. A database search was performed using Mascot Daemon (2.5.0) (47) against a house-built database (10,917 sequences; 5,394,123 residues). Modifications related to [12C]glycylation on a glutamate residue were custom-built and searched against. All spectra corresponding to glycylated peptides were manually curated. We based our assignment of the hierarchy of modification sites on the distribution of glycylated species that we found in our modified microtubule samples that contained a mixture of glycylated species. These data show that the main monoglycylated species is modified at E441. At low levels of modification, the raw data show a single peak for the +1 Gly species at E441 (Fig. S2A). No other reliable peaks for monoglycylated species were found in the extracted-ion chromatogram (XIC) (Fig. S2E). All +2 Gly, +3 Gly, and +4 Gly species contain a glycine residue added at E441 (Fig. S2 A–D). The only two diglycylated species we find in our samples (E438/E441 and E441/E442) are of comparable abundance as can be seen in the XIC (Fig. S2F), and all +3 Gly species contain modified E441 and E438. Last, all +4 Gly species contain modified E441, E438, and E442. Thus, the hierarchy of modification is from E441 to then E438 and E442 followed by E439 and E443 (the XIC in Fig. S2G shows lower abundance for the species containing modified E443 compared with E439).

To confirm that the DFGEEAEEEA peptide is not modified by an elongated Gly chain, we also acquired MS/MS/MS data of the b7 ion for the DFGEEAEEEA +3 Gly form. Analysis of the MS3 fragments showed no evidence of elongated Gly chains. Last, we also fragmented the DFGEEAEEEA +3 Gly with electron transfer dissociation (ETD). Analyses of the ETD MS/MS spectra also did not detect the presence of elongated Gly chains.

TTLL7 was incubated with Taxol-stabilized unmodified microtubules at room temperature (1 μM TTLL3, 10 μM microtubules) in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7), 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM TCEP, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM l-[13C]glutamate (Sigma), and 20 μM Taxol, and aliquots were removed at 0 h, 20 min, 1 h, and 2 h. Reactions were quenched as above. Glutamylated microtubules (3 μg) were separated by SDS/PAGE as described (4). Bands for β-tubulin were excised and digested with Asp-N (1:20 ratio of protease to substrate) at 37 °C overnight. All samples were processed for MS/MS analysis as above. Modifications related to [13C]glutamylation were custom-built and searched against. All spectra corresponding to glutamylated peptides were manually curated.

In Vitro Microtubule Glycylation Assays of Structure-Guided TTLL3 Mutants.

Wild-type X. tropicalis TTLL3 (residues 1–592) and structure-based mutants were cloned into a modified mammalian expression FX vector (6) with an N-terminal FLAG tag. Constructs were transiently transfected into tSA201 cells grown in suspension media (FreeStyle 293 supplemented with 2% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were harvested 44 h posttransfection and lysed by sonication in buffer containing 50 mM Tris⋅Cl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM DTT, 5 μg/mL DNase, and cOmplete EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture. Proteins were purified from clarified lysate using anti-DYKDDDDK G1 affinity resin (GenScript) and eluted with 0.25 μg/mL FLAG peptide in 50 mM Tris⋅Cl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl and buffer-exchanged. Purified proteins were incubated with 5 μM Taxol-stabilized unmodified microtubules for 5.5 h at room temperature in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7), 10 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM TCEP, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM glycine, and 20 μM Taxol. Samples were separated by SDS/PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for Western blot analysis. Monoglycylated tubulin was detected with monoclonal mouse antibody TAP952 (1:2,500; Merck Millipore) and goat anti-mouse 680LT secondary antibody (1:10,000; LI-COR). Total tubulin was detected with monoclonal rabbit antibody EP1332Y (1:5,000; Merck Millipore) and goat anti-rabbit 800CW secondary antibody (1:10,000, LI-COR). FLAG-tagged enzyme was detected with polyclonal anti-DYKDDDDK rabbit antibody (1:2,500; GenScript) and goat anti-rabbit 800CW secondary antibody (1:10,000; LI-COR). All blots were imaged and quantified using an Odyssey scanner and Image Studio Lite analysis software (LI-COR). For assays with glutamylated microtubules (Fig. 2), 1 μM X. tropicalis TTLL3 (residues 6–569) was incubated with 10 μM glutamylated microtubules generated as described below in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7), 10 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM TCEP, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM l-glycine, and 20 μM Taxol. Tubulin (400 ng) from each time point was separated by SDS/PAGE as described (7) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane for Western blotting. Glycylated tubulin was detected using monoclonal mouse antibody TAP952 (1:5,000; Merck Millipore) and goat anti-mouse 680LT secondary antibody (1:18,000; LI-COR), whereas total tubulin was detected using monoclonal rabbit antibody EP1332Y (1:5,000; Merck Millipore) and goat anti-rabbit 800CW secondary antibody (1:18,000; LI-COR). Blots were imaged and quantified using an Odyssey scanner and Image Studio Lite analysis software (LI-COR).

Crystallization, X-Ray Structure Determination, and Refinement.

X. tropicalis TTLL3 (residues 6–569) was used for initial crystallization trials and yielded poorly diffracting crystals. Mass spectrometric analysis revealed that TTLL3 self-modified, producing a heterogeneous mixture of glycylated species. To solve this heterogeneity problem, we conducted all subsequent crystallographic studies with a catalytic inactive mutant (E520Q). This construct yielded high-quality crystals suitable for structure determination. For crystallization studies, TTLL3 (residues 6–569) was concentrated to ∼10 mg/mL in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7), 200 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM TCEP, and 1 mM AMPPNP. Crystals grew at 4 °C by hanging-drop vapor diffusion from protein solution mixed at a 1:1 ratio with 100 mM Tris⋅Cl (pH 8), 20% PEG 3350, and 200 mM LiSO4. Crystals grew with symmetry of space group P21 with two copies in the asymmetric unit. Crystals typically appeared after 2 d and grew to maximum dimensions (∼300 × 200 × 50 μm) in 2 to 3 wk. Crystals were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen following quick soaks in 100 mM Tris⋅Cl (pH 8), 32% PEG 3350, 200 mM LiSO4, and 1 mM AMPPNP.

A 35.7-fold redundant single-wavelength anomalous dispersion dataset was collected at beamline 5.0.1 of the Advanced Light Source at 400 eV above the Hg L-III peak on a TTLL3 crystal soaked for 5 h in 100 mM Tris⋅Cl (pH 8), 20% PEG 3350, 200 mM LiSO4, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM AMPPNP, 0.5 mM TCEP, and 5 mM ethyl mercuric phosphate. Diffraction data were integrated and scaled using HKL2000 (8). Phenix AutoSol (45) correctly identified 21 anomalous scattering sites. The phasing figure of merit was 0.47. Iterative rounds of building in Coot (44) and refinement in PHENIX (45) allowed building of ∼60% of the unit-cell contents.

A native dataset for TTLL3–AMPPNP (a = 58.6, b = 192.2, c = 60.74, β = 114.3°, diffraction limit 2.28 Å) was collected at beamline 5.0.2 of the Advanced Light Source. Diffraction data were reduced using HKL2000 (8), and the structure was solved by molecular replacement using Phaser (43) with the coordinates of the TTLL3–EMP derivative used as search model. Iterative rounds of model building in Coot (44) and refinement in PHENIX (45) were performed. Our current refinement model for TTLL3–AMPPNP consists of 805 residues and 253 waters. Seven regions of the polypeptide chain (residues 53–98, 174–180, 202–240, 259–283, 333–344, 357–369, and 414–446 of chain A, and residues 53–98, 174–178, 202–240, 262–276, 335–344, 357–369, and 420–443 of chain B) are not well-resolved in the electron density map and are presumed disordered. The current crystallographic model at a resolution of 2.28 Å has an Rwork and Rfree of 20.0% and 23.0%, respectively (Table S1). MolProbity (48) revealed no unfavorable (ϕ,ψ) combinations. Maps of electrostatic surfaces were calculated with DelPhi (49).

Generation of Glutamylated Microtubule Substrates.

Glutamylated microtubules were generated as described (15). Briefly, unmodified human microtubules were incubated with X. tropicalis TTLL7 (residues 1–520) at room temperature at a 1:10 ratio of enzyme to substrate (2 μM TTLL7, 20 μM microtubules) in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7), 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM TCEP, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM l-glutamate, and 20 μM Taxol for 2 h (for <E> 8.1 on β-tubulin, 0.3 on α-tubulin), 5 h (for <E> 15.2 on β-tubulin, 0.9 on α-tubulin), and 14 h (for <E> 23.1 on β-tubulin, 2.4 on α-tubulin) and brought to 300 mM KCl at 37 °C for 15 min followed by pelleting through a 60% glycerol cushion in 1× BRB80 supplemented with 1 mM DTT and 20 μM Taxol to remove TTLL7 (15). Samples were subjected to mass spectrometric analysis to quantitatively determine glutamylation levels as previously described (15). Aliquots (2 μg) were separated on a Zorbax 300SB C18 column (Agilent) using a 0 to 70% acetonitrile gradient in 0.05% TFA at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. The column was attached in-line with a 6224 ESI-TOF LC/MS (Agilent). Data were analyzed using the MassHunter Workstation platform (Agilent).

Glycylation Assays Using [3H]Gly Incorporation.

TTLL3 was incubated with unmodified Taxol-stabilized human microtubules at a 1:10 molar ratio (1 μM enzyme, 10 μM microtubules) at 25 °C in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7), 10 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM TCEP, 1 mM ATP, 90 μM [2H]glycine, 10 μM [3H]amino acid, and 20 μM Taxol. Five microliters of the reaction mixture was spotted on Hybond-N+ filters (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) at t = 0, 10, 20, 30, 45, 60, 90, and 120 min. Individual filters were washed with 10 mL 50 mM NaPi (pH 6.8), 50 mM KCl and dissolved with 3 mL of Filter-Count (PerkinElmer). Radiolabeled Gly incorporation was measured by 3H liquid scintillation. Reactions were performed in triplicate on 2 different days.

Immunofluorescence.

U2OS cells were transfected with N-terminal GFP-tagged wild-type and mutant X. tropicalis TTLL3 or C-terminal GFP-tagged wild-type and mutant Mus musculus TTLL8. Cells were fixed 36 h posttransfection in cytoskeletal buffer (CB) (10 mM Mes, pH 6.1, 138 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EGTA) containing 4% paraformaldehyde and 10 μM Taxol, and permeabilized in CB containing 0.5% Triton X-100. Growth media were supplemented with 10 μM Taxol for 30 min before fixation to preserve microtubules. Tubulin was detected using polyclonal rabbit antibody ab18251 (1:100 dilution; Abcam) and Alexa Fluor 647-labeled goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:200 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch). Glycylated tubulin was detected with monoclonal mouse antibody TAP952 (1:500 dilution; Millipore) and DyLight 549-labeled goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:200 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch). Cells were mounted in ProLong Gold Antifade with DAPI (Life Technologies). Images of all TTLL3 constructs were acquired on a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope equipped with a Nikon Plan Apo VC 60× (N.A. 1.40) oil objective, Nikon Intensilight C-HGFI light source, and CoolSNAP HQ2 CCD camera (Photometrics). Nikon ET DAPI, ET GFP, ET dsRed, and ET Cy5 filters were used to image emitted light. All images were acquired at a 100-ms exposure for all channels. Images of all TTLL8 constructs were acquired on a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope equipped with a CSU-X1 spinning disk confocal scanner unit (Yokogawa), Nikon Plan Apo VC 60× (N.A. 1.40) oil objective, and ORCA-Flash4.0 V2 camera (Hamamatsu). Excitation light for DAPI (405 nm), GFP (488 nm), DyLight 549 (561 nm), and Alexa Fluor 647 (640 nm) was provided by an Agilent MLC400B monolithic laser combiner. Appropriate filters were used to image emitted light: Chroma ET460/50m for DAPI, Chroma ET514/30m for GFP, Chroma ET605/52m for DyLight 549, and Semrock FF01 731/137 for Alexa Fluor 647. All images were acquired at a 100-ms exposure for all channels. Microscope automation for both setups was controlled using μManager software (50). Brightness and contrast of all images was adjusted postacquisition using ImageJ software (NIH), and panels were assembled in Photoshop (Adobe). Wild-type and mutant TTLL8 activity was quantified by normalizing TAP952 signal to total tubulin and total GFP signal using ImageJ.

Discussion

Our in vitro characterization reveals that the TTLL3 glycylase adds single glycines to multiple sites on the β-tail following a positional hierarchy, with E441 as the main modification site. TTLL3 shows preference for the β-tail either in isolation or presented in the microtubule context. The TTLL3 mechanism of substrate recognition differs from the glutamylase TTLL7. In the case of TTLL7, preferential modification of the β-tail arises from additional interactions with the microtubule distant from the active site (38). Cellular studies indicate that TTLL8 is an α-tubulin–specific initiase (12, 20). Thus, there are two glycyl initiases in mammals, TTLL3 and -8, whereas TTLL10 functions as an elongase adding multiple glycines on both α- and β-tails (12, 20). Interestingly, no polyglycylated tubulin was found in humans (12, 17). This lack of polyglycylation was proposed to be due to two inactivating mutations in human TTLL10 (N448S and T467K) (12). Surprisingly, our structure reveals that these mutations map to α10 and α11 on the enzyme posterior surface, away from the active site (Fig. S5), where they are unlikely to have a direct effect on activity.

Our TTLL3 crystal structure identifies unique architectural elements that define a TTLL member as an initiating glycylase. TTLL3 augments its TTL-like core with two conserved elements, IS1 and IS2, critical for glycylation (Fig. 3). These architectural extensions reside at opposite ends of a positively charged microtubule recognition interface (Fig. 4) and are distinctly different from the cationic α-helical microtubule-binding domain (cMTBD) shared among autonomous glutamylases (Fig. 3) (38). The cMTBD is absent from glycylases (Fig. S8). Thus, our work reveals a second strategy for functionalizing the TTL structural scaffold to achieve substrate recognition diversity in the family.

Fig. S8.

Structure-based multiple sequence alignment of representative human TTLL sequences: TTLL3 (NP_001021100, BAG59759, NR_037162.1), TTLL8 (XP_016884665.1), TTLL10 (NP_001123517.1), TTLL1 (NP_03695.1), TTLL6 (NP_001124390.1), TTLL7 (NP_078962.4), and TTL (NP_714923.1). Alignment was performed with the program T-Coffee (www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/tcoffee/). The output alignment was used as input in JALVIEW (www.jalview.org) and manually curated. Residues are colored according to the Blosum62 matrix, with an identity threshold set to 30%. Secondary structure elements are indicated above the corresponding sequence. Disordered elements are designated by a hatched line. IS1 and IS2 specific to monoglycylases TTLL3 and TTLL8 are colored in red as in Fig. S5. The cationic microtubule-binding domain (cMTBD) and cMTBD anchor helix specific to all autonomous glutamylases (only TTLL6 and TTLL7 sequences are shown) are colored orange and aqua, respectively, as in Fig. 3. Glycylase-specific residues important for activity are highlighted with a red box, whereas residues universally conserved across TTL and TTLLs important for activity are highlighted by a black box.

Both TTLL3 and TTLL8 function in cilia and flagella, cellular structures that are highly enriched in glutamylation (37). Glutamylation is prevalent during ciliogenesis; however, glycylation is required for stabilization of an already-formed cilium (22). Therefore, TTLL3 and TTLL8 likely encounter tubulin that is already glutamylated. We demonstrate with purified components that the glycylase TTLL3 and glutamylase TTLL7 compete for overlapping initiating sites on the β-tail, providing a molecular basis for the observed negative correlation between glutamylation and glycylation in vivo (13, 25, 26, 32). Consistent with this competition, TTLL3 activity is drastically reduced on microtubules with abundant glutamylation. Unexpectedly, we find that at high levels of β-tubulin tail glutamylation, α-tail glycylation by TTLL3 is enhanced. This finding is consistent with prior in vivo studies in Tetrahymena showing that removal of glycylation/glutamylation sites in the β-tail enhances α-tail glycylation (26). Although the functional significance of this observation remains to be explored, our study provides a blueprint for investigating how tubulin modification patterns are generated in vivo through the intersection of activities of multiple TTLL enzymes.

Materials and Methods

Protein Production, Crystallization, and Structure Determination.

Baculovirus expression clones for wild-type and mutant TTLL3 constructs were generated as described in SI Materials and Methods. TTLL3 crystallization and X-ray data collection are described in detail in SI Materials and Methods. Detailed procedures for structural determination and refinement are in Table S1 and SI Materials and Methods. The structure was solved by molecular replacement using Phaser (43). Iterative rounds of model building in Coot (44) and refinement in PHENIX (45) were performed.

MS/MS Analyses of Glycylated and Glutamylated Peptides.

TTLL3 was incubated with Taxol-stabilized unmodified human microtubules, and reactions were prepared for MS/MS analyses as described in SI Materials and Methods. A Thermo Fisher Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer coupled with a 3000 UltiMate HPLC was used for LC/MS/MS data acquisition. Samples were separated as detailed and spectra were analyzed as detailed in SI Materials and Methods. TTLL7 was incubated with Taxol-stabilized unmodified microtubules and reactions were prepared for MS/MS analyses as described in SI Materials and Methods. Modifications related to [13C]glutamylation were custom-built and searched against. All spectra corresponding to glutamylated peptides were manually curated.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at Sector 5 (Advanced Light Source) for X-ray data collection support, and D.-Y. Lee and the NHLBI Biochemistry Core for access to mass spectrometers. A.R.-M. is supported by the intramural programs of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: Atomic coordinates and structure factors reported in this paper have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 5VLQ).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1617286114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Roll-Mecak A. Intrinsically disordered tubulin tails: Complex tuners of microtubule functions? Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015;37:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verhey KJ, Gaertig J. The tubulin code. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2152–2160. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.17.4633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu I, Garnham CP, Roll-Mecak A. Writing and reading the tubulin code. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:17163–17172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.637447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valenstein ML, Roll-Mecak A. Graded control of microtubule severing by tubulin glutamylation. Cell. 2016;164:911–921. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bieling P, et al. CLIP-170 tracks growing microtubule ends by dynamically recognizing composite EB1/tubulin-binding sites. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:1223–1233. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nirschl JJ, Magiera MM, Lazarus JE, Janke C, Holzbaur EL. α-Tubulin tyrosination and CLIP-170 phosphorylation regulate the initiation of dynein-driven transport in neurons. Cell Reports. 2016;14:2637–2652. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raybin D, Flavin M. Enzyme which specifically adds tyrosine to the alpha chain of tubulin. Biochemistry. 1977;16:2189–2194. doi: 10.1021/bi00629a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murofushi H. Purification and characterization of tubulin-tyrosine ligase from porcine brain. J Biochem. 1980;87:979–984. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a132828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schröder HC, Wehland J, Weber K. Purification of brain tubulin-tyrosine ligase by biochemical and immunological methods. J Cell Biol. 1985;100:276–281. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.1.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Dijk J, et al. A targeted multienzyme mechanism for selective microtubule polyglutamylation. Mol Cell. 2007;26:437–448. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikegami K, et al. TTLL7 is a mammalian beta-tubulin polyglutamylase required for growth of MAP2-positive neurites. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30707–30716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603984200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rogowski K, et al. Evolutionary divergence of enzymatic mechanisms for posttranslational polyglycylation. Cell. 2009;137:1076–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wloga D, et al. TTLL3 is a tubulin glycine ligase that regulates the assembly of cilia. Dev Cell. 2009;16:867–876. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Konno A, Setou M, Ikegami K. Ciliary and flagellar structure and function—Their regulations by posttranslational modifications of axonemal tubulin. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2012;294:133–170. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394305-7.00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishikawa H, Marshall WF. Ciliogenesis: Building the cell’s antenna. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:222–234. doi: 10.1038/nrm3085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Redeker V, et al. Polyglycylation of tubulin: A posttranslational modification in axonemal microtubules. Science. 1994;266:1688–1691. doi: 10.1126/science.7992051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bré MH, et al. Axonemal tubulin polyglycylation probed with two monoclonal antibodies: Widespread evolutionary distribution, appearance during spermatozoan maturation and possible function in motility. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:727–738. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.4.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rüdiger M, Plessmann U, Rüdiger AH, Weber K. Beta tubulin of bull sperm is polyglycylated. FEBS Lett. 1995;364:147–151. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00373-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wall KP, et al. Molecular determinants of tubulin’s C-terminal tail conformational ensemble. ACS Chem Biol. 2016;11:2981–2990. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ikegami K, Setou M. TTLL10 can perform tubulin glycylation when co-expressed with TTLL8. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:1957–1963. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rocha C, et al. Tubulin glycylases are required for primary cilia, control of cell proliferation and tumor development in colon. EMBO J. 2014;33:2247–2260. doi: 10.15252/embj.201488466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bosch Grau M, et al. Tubulin glycylases and glutamylases have distinct functions in stabilization and motility of ependymal cilia. J Cell Biol. 2013;202:441–451. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201305041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forrest WF, Cavet G. Comment on “The consensus coding sequences of human breast and colorectal cancers.”. Science. 2007 doi: 10.1126/science.1138179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pathak N, Austin CA, Drummond IA. Tubulin tyrosine ligase-like genes ttll3 and ttll6 maintain zebrafish cilia structure and motility. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:11685–11695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.209817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kann ML, Prigent Y, Levilliers N, Bré MH, Fouquet JP. Expression of glycylated tubulin during the differentiation of spermatozoa in mammals. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1998;41:341–352. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1998)41:4<341::AID-CM6>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Redeker V, et al. Mutations of tubulin glycylation sites reveal cross-talk between the C termini of alpha- and beta-tubulin and affect the ciliary matrix in Tetrahymena. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:596–606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vemu A, Garnham CP, Lee DY, Roll-Mecak A. Generation of differentially modified microtubules using in vitro enzymatic approaches. Methods Enzymol. 2014;540:149–166. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-397924-7.00009-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Widlund PO, et al. One-step purification of assembly-competent tubulin from diverse eukaryotic sources. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:4393–4401. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-06-0444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen-Smith HC, Ludueña RF, Hallworth R. Requirement for the betaI and betaIV tubulin isotypes in mammalian cilia. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2003;55:213–220. doi: 10.1002/cm.10122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vinh J, et al. Structural characterization by tandem mass spectrometry of the posttranslational polyglycylation of tubulin. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3133–3139. doi: 10.1021/bi982304s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mary J, Redeker V, Le Caer JP, Rossier J, Schmitter JM. Posttranslational modifications in the C-terminal tail of axonemal tubulin from sea urchin sperm. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9928–9933. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.17.9928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bulinski JC. Tubulin posttranslational modifications: A Pushmi-Pullyu at work? Dev Cell. 2009;16:773–774. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mukai M, et al. Recombinant mammalian tubulin polyglutamylase TTLL7 performs both initiation and elongation of polyglutamylation on beta-tubulin through a random sequential pathway. Biochemistry. 2009;48:1084–1093. doi: 10.1021/bi802047y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Redeker V. Mass spectrometry analysis of C-terminal posttranslational modifications of tubulins. Methods Cell Biol. 2010;95:77–103. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(10)95006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mary J, Redeker V, Le Caer JP, Promé JC, Rossier J. Class I and IVa beta-tubulin isotypes expressed in adult mouse brain are glutamylated. FEBS Lett. 1994;353:89–94. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geimer S, Teltenkötter A, Plessmann U, Weber K, Lechtreck KF. Purification and characterization of basal apparatuses from a flagellate green alga. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1997;37:72–85. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1997)37:1<72::AID-CM7>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneider A, Plessmann U, Felleisen R, Weber K. Posttranslational modifications of trichomonad tubulins; identification of multiple glutamylation sites. FEBS Lett. 1998;429:399–402. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00644-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garnham CP, et al. Multivalent microtubule recognition by tubulin tyrosine ligase-like family glutamylases. Cell. 2015;161:1112–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prota AE, et al. Structural basis of tubulin tyrosination by tubulin tyrosine ligase. J Cell Biol. 2013;200:259–270. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szyk A, Deaconescu AM, Piszczek G, Roll-Mecak A. Tubulin tyrosine ligase structure reveals adaptation of an ancient fold to bind and modify tubulin. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:1250–1258. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sjöblom T, et al. The consensus coding sequences of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2006;314:268–274. doi: 10.1126/science.1133427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amanchy R, et al. A curated compendium of phosphorylation motifs. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:285–286. doi: 10.1038/nbt0307-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levine RL. Fixation of nitrogen in an electrospray mass spectrometer. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2006;20:1828–1830. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perkins DN, Pappin DJ, Creasy DM, Cottrell JS. Probability-based protein identification by searching sequence databases using mass spectrometry data. Electrophoresis. 1999;20(18):3551–3567. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19991201)20:18<3551::AID-ELPS3551>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen, et al. MolProbity: All-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallographica. 2010;D66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li L, et al. DelPhi: A comprehensive suite for DelPhi software and associated resources. BMC Biophys. 2012;5:9. doi: 10.1186/2046-1682-5-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Edelstein A, Amodaj N, Hoover K, Vale R, Stuurman N. Computer control of microscopes using μManager. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2010;92:14.20.1–14.20.17. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb1420s92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]