Significance

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors lower blood glucose in humans with diabetes. These drugs inhibit the reabsorption of glucose in the kidney, resulting in its urine excretion. It was reported that SGLT2 inhibitors increase the secretion of glucagon and increase endogenous glucose production by the liver. These effects would elevate blood glucose, counteracting the effect of urinary glucose loss. Here we show in a rodent model of type 1 diabetes that the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin inhibited the secretion of glucagon from the pancreas. In two rodent models of severe type 2 diabetes, livers from animals treated with dapagliflozin showed decreased glucagon signaling and had reduced expression of the glucagon receptor. Our results suggest dapagliflozin lowers blood glucose concentrations in diabetic animals in part through inhibiting hepatic glucagon signaling.

Keywords: diabetes, glucagon, dapagliflozin, SGLT2 inhibition, glucagon receptor

Abstract

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors are a class of antidiabetic drug used for the treatment of diabetes. These drugs are thought to lower blood glucose by blocking reabsorption of glucose by SGLT2 in the proximal convoluted tubules of the kidney. To investigate the effect of inhibiting SGLT2 on pancreatic hormones, we treated perfused pancreata from rats with chemically induced diabetes with dapagliflozin and measured the response of glucagon secretion by alpha cells in response to elevated glucose. In these type 1 diabetic rats, glucose stimulated glucagon secretion by alpha cells; this was prevented by dapagliflozin. Two models of type 2 diabetes, severely diabetic Zucker rats and db/db mice fed dapagliflozin, showed significant improvement of blood glucose levels and glucose disposal, with reduced evidence of glucagon signaling in the liver, as exemplified by reduced phosphorylation of hepatic cAMP-responsive element binding protein, reduced expression of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 2, increased hepatic glycogen, and reduced hepatic glucose production. Plasma glucagon levels did not change significantly. However, dapagliflozin treatment reduced the expression of the liver glucagon receptor. Dapagliflozin in rodents appears to lower blood glucose levels in part by suppressing hepatic glucagon signaling through down-regulation of the hepatic glucagon receptor.

Inhibitors of the sodium-coupled glucose transporter sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) are effective medicines for lowering blood glucose levels in humans with insulin-resistant diabetes (1–3). SGLT2 is a low-affinity, high-capacity symporter expressed in the apical membrane of cells in the S1 segment of the proximal convoluted tubules of the kidney and is responsible for the majority of reabsorption of glucose from filtrate. It is thought that SGLT2 inhibitors lower blood glucose primarily by increasing glycosuria. Recently, two studies of human patients with type 2 diabetes treated with two different SGLT2 inhibitors reported an elevation of endogenous glucose production, as well as increased plasma glucagon levels (4, 5), although the rises in glucagon with acute treatment were quite small, and in one case (4), chronic treatment did not increase plasma glucagon concentrations. It has also been reported that SGLT2 is present on pancreatic alpha cells, but not beta cells, and that treating human islets with the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin triggers glucagon secretion in vitro (6, 7). However, in the absence of insulin, elevated glucose stimulates, rather than inhibits, glucagon secretion (8, 9). If SGLT2 is the glucose transporter on the alpha cell responsible for sensing elevated glucose levels and is not present on beta cells, one would expect dapagliflozin to inhibit glucagon secretion. In addition, there is a large and growing literature showing that lowering blood glucose levels in diabetes requires the blunting of endogenous glucose production stimulated by glucagon (10, 11).

Our interest in these contradictory observations has its foundation in an earlier observation we made, in which we conducted a high-throughput screen for chemicals that could inhibit the secretion of glucagon from a hamster alpha cell-derived cell line, InR1-G9 cells (12). One of the most effective compounds was identical to a nonglycosidic SGLT2 inhibitor (13). Thus, we decided to investigate the effect of inhibiting SGLT2 on glucagon secretion by alpha cells and on glucagon action in the liver, using rodent models of type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

Results

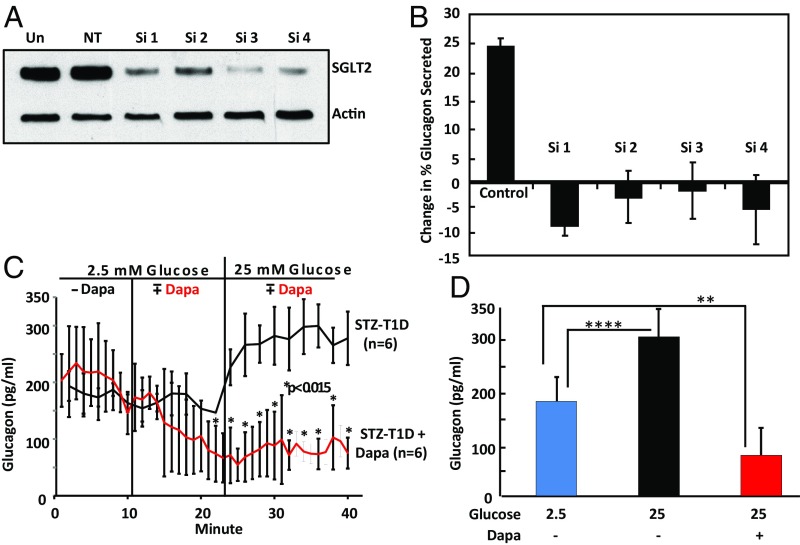

To confirm SGLT2 was necessary for the glucose sensing by alpha cells that results in secretion of glucagon, we designed siRNA oligonucleotides to target the hamster SGLT2 message expressed in InR1-G9 cells. InR1-G9 cells were transfected with either control siRNA or siRNAs targeting SGLT2. As shown in Fig. 1A, SGLT2 protein levels were reduced by ∼90% by our protocol. As shown in Fig. 1B, glucagon secretion increased ∼25% in high glucose (P = 0.013, two-tailed t test with unequal variance) in the sample treated with the nontargeting oligonucleotide and showed a slight decrease for the samples treated with each of the four siRNA oligonucleotides that was not statistically significant. Thus, SGLT2 appears to be necessary for InR1-G9 cells to increase glucagon secretion in response to high glucose.

Fig. 1.

Response of alpha cells treated with dapagliflozin to increasing glucose. InR1-G9 cells were transfected with either a nontargeting (NT) or four different siRNAs targeting hamster SGLT2. Cells were cultured 3 d and transfected again for an additional 3 d. (A) An immunoblot shows the extent of SGLT2 knockdown. Un, untransfected control. Actin serves as a loading control. (B) Glucagon values from three biological replicates treated with each siRNA and cultured for 18 h in medium containing 5 mM glucose are compared with samples cultured for the same time in medium containing 25 mM glucose. The mean change in glucagon secretion is graphed for each sample with SEM. The control is the nontargeting siRNA. (C) Glucagon production by perfused pancreata in response to increased glucose in the perfusate. The red line on the graph shows glucagon secretion by pancreata treated with 20 µmol/L dapagliflozin. Dapagliflozin was added at 10 min after the perfusion began. At 25 min, the glucose in the perfusate was increased from 2.5 to 25 mM. The black line shows glucagon secretion by control pancreata in the same experiment. n = 6 for each group. STZ, streptozotocin; T1D, type 1 diabetes. (D) The mean plateau glucagon concentrations after challenge with 25 mM glucose in the presence or absence of 20 µmol/L dapagliflozin are compared with a challenge with 2.5 mM glucose without the drug. SDs are shown, and Student’s two-tailed t test was used to calculate P, the probability of a null hypothesis in this and other figures. **P < 0.015; ****P < 0.0001. Glucagon was measured with a Cisbio ELISA kit.

Perfusion of Pancreata.

To determine the direct effect of inhibiting SGLT2 on alpha cells without any confounding effect on beta cells, we treated SD rats with streptozotocin until they had severe type 1 diabetes. Insulin was undetectable in the blood collected from SD rats treated with two doses of streptozotocin, as determined by radioimmune assay (RIA). Seven days after the second dose of streptozotocin, the rats were fasted for 19 h and then anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg body weight) administered intraperitoneally. Each pancreas was isolated and perfused in situ at 37 °C.

In response to the increase in glucose concentration in the perfusate from 2.5 to 25 mM, glucagon in the perfusate from control pancreata increased from ∼175 to 275 pg/mL (Fig. 1C, black line; P < 0.0001), a 64% increase. In contrast, when treated with dapagliflozin in 2.5 mM glucose, the concentration of glucagon in the perfusate declined from the 175 pg/mL range to 50 pg/mL and remained at this low level when glucose was increased to 25 mM (red line). The average plateau values for glucagon in the perfusate after a challenge with 25 mM glucose in the presence of dapagliflozin was significantly depressed compared with control perfusate (Fig. 1D; P < 0.015). Insulin was not detected in the perfusates by Cisbio ELISA. Thus, in pancreata from streptozotocin-treated animals not producing detectable insulin, the response to elevated glucose was a stimulation of glucagon secretion; this was prevented when SGLT2 was inhibited.

Dapagliflozin Decreases Glucagon Receptor Signaling in a Model of Type 2 Diabetes.

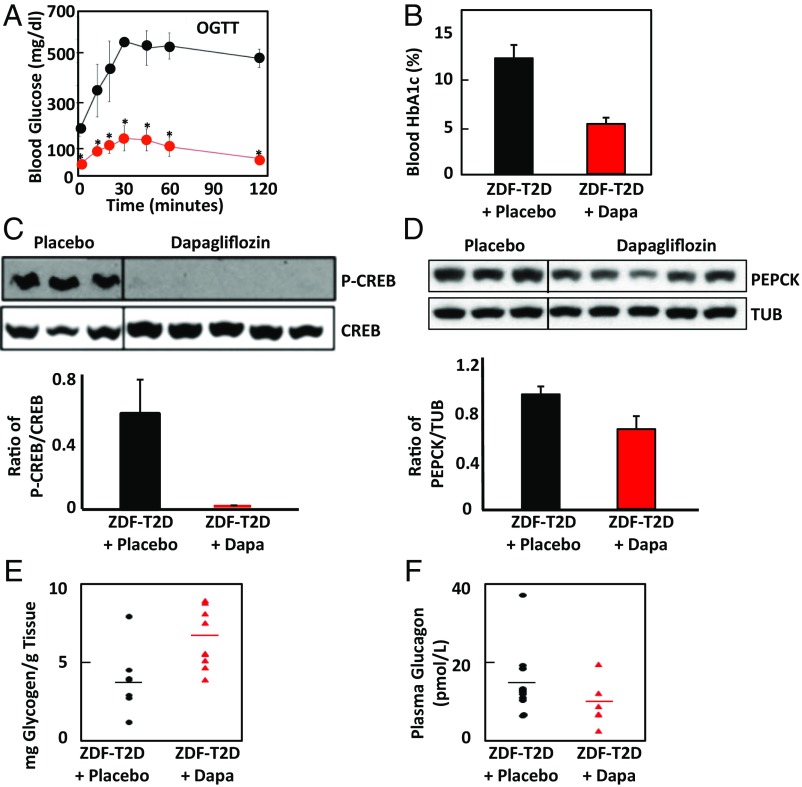

Zucker diabetic fatty (ZDFfa/fa) rats are a well-established model of type 2 diabetes (14). Male Zucker fatty rats 13–15 wk old with blood glucose levels higher than 500 mg/dL were randomly selected into two groups. The treatment group was fed with dapagliflozin (50 mg/1,000 g diet, ∼0.45 mg/kg/day) mixed with 6% fat powder diet, and the placebo group was pair-fed with the same amount of 6% fat powder diet as was consumed by the dapagliflozin-treated group. After 1 wk treatment, ZDFfa/fa rats showed a marked improvement in the response to oral glucose (Fig. 2A). Fig. 2B shows that after 6 wk of the treatment regimen with dapagliflozin, HbA1c levels in blood from ZDFfa/fa rats decreased from the ∼12% seen in control animals to below 6%. This indicates that dapagliflozin was actively lowering blood glucose levels in the treated animals. Consistent with the data presented in Fig. 2A and Fig. 2B, 7 wk of dapagliflozin treatment reduced the phosphorylation of cAMP-responsive element binding protein, CREB, indicating that its activity was lower in the treated animals (Fig. 2C). This indicated that glucagon signaling was reduced. Another consequence of hepatic glucagon signaling is an increase in expression of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 2, PEPCK. Dapagliflozin treatment for 7 wk decreased the hepatic expression of PEPCK relative to that detected in livers from the placebo group (Fig. 2D). Glucagon also promotes glycogenolysis in the liver. Hepatic glycogen content in dapagliflozin-treated ZDF rats averaged 6.8 mg/g compared with 4.0 mg/g for the rats treated with placebo (P = 0.02; two-tailed t test; Fig. 2E), consistent with a decrease in glucagon signaling. However, plasma glucagon levels were not significantly reduced relative to the placebo group (P = 0.11; Student’s t test) after 44 d of treatment with dapagliflozin (Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2.

In the ZDFfa/fa rodent model of type 2 diabetes, treatment with dapagliflozin significantly improves glucose disposal and glycemic control and reduces signs of hepatic glucagon action. (A) An oral glucose tolerance test was performed with conscious ZDF rats after 7-d treatment with dapagliflozin or placebo. The red line indicates mean glucose measurements ± SDs from five dapagliflozin-treated animals. The black line indicates similar measurements from four placebo-treated animals. *P < 0.02. (B) Six weeks of treatment of Zucker fatty rats with dapagliflozin significantly lowers HbA1c levels (P < 0.015). Means with SDs for blood HbA1c levels for six placebo-treated (black) and six dapagliflozin-treated (red bar, Dapa) ZDF rats are shown. (C) Liver samples from the placebo and dapagliflozin-treated animals after 7 wk were immunoblotted for the gluconeogenic transcription factor CREB, which is activated by phosphorylation. The upper band is labeled with an antibody for phosphorylated CREB, and the lower with an antibody recognizing all forms of CREB. The average ratio of phosphorylated to unphosphorylated CREB for the two sample sets measured by densitometry is graphed with SDs (P = 0.04). (D) Liver samples from the placebo and dapagliflozin-treated animals were immunoblotted for PEPCK and for tubulin (TUB) as a loading control. The average ratio of PEPCK to tubulin for the two sample sets measured by densitometry is graphed with SDs (P = 0.025). (E) Glycogen content of livers from 6 (control, black) or 9 (dapagliflozin, red) rats treated for 7 wk was measured. (F) Plasma glucagon was measured for placebo-treated (n = 11) or dapagliflozin-treated (n = 5) ZDFfa/fa rats (P = 0.11) after 44 d, using a Mercodis ELISA kit. The lines on the scatter plot indicate the means of each group.

Dapagliflozin Improves Glucose Disposal and Decreases Endogenous Glucose Production in a Mouse Model of Type 2 Diabetes.

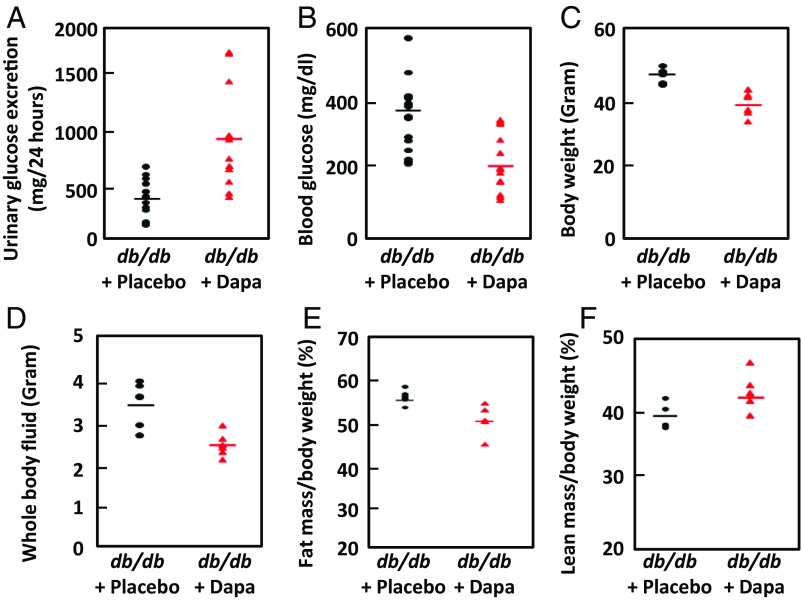

Another well-established rodent model of type 2 diabetes is the db/db mouse. Twelve 8-wk-old male B6 BKS(D)-Leprdb/J db/db homozygous mice were randomly divided into two groups: one fed with standard laboratory chow containing 50 mg dapagliflozin /1,000 g diet, the other with the same diet lacking dapagliflozin (15). One week of treatment with dapagliflozin significantly increased (P = 0.0015) urinary glucose excretion (Fig. 3A) and lowered blood glucose (Fig. 3B; P = 0.0007). After 4 wk of treatment, there was a decrease in overall body weight (P = 0.003; Fig. 3C). The dapagliflozin-treated animals retained less body fluid (P = 0.01; Fig. 3D) and had less fat mass (P = 0.05; Fig. 3E) and greater lean mass (P = 0.03; Fig. 3F). All these parameters are consistent with better glucose homeostasis and improved insulin sensitivity.

Fig. 3.

Dapagliflozin treatment improves glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity in db/db mice. (A) Consistent with the known action of dapagliflozin, treated animals had increased excretion of glucose compared with controls (P = 0.0015). The following parameters all decreased significantly in the dapagliflozin-treated group. (B) Blood glucose concentration (P = 0.0007). Urinary glucose and blood glucose were measured daily for 3 d for each animal. (C) Body weight (P = 0.003). (D) Whole-body fluid (P = 0.014). (E) Fat mass as a percentage of body mass (P < 0.05). (F) Lean mass of dapagliflozin mice increased (P = 0.03). n = 6 for each treatment group.

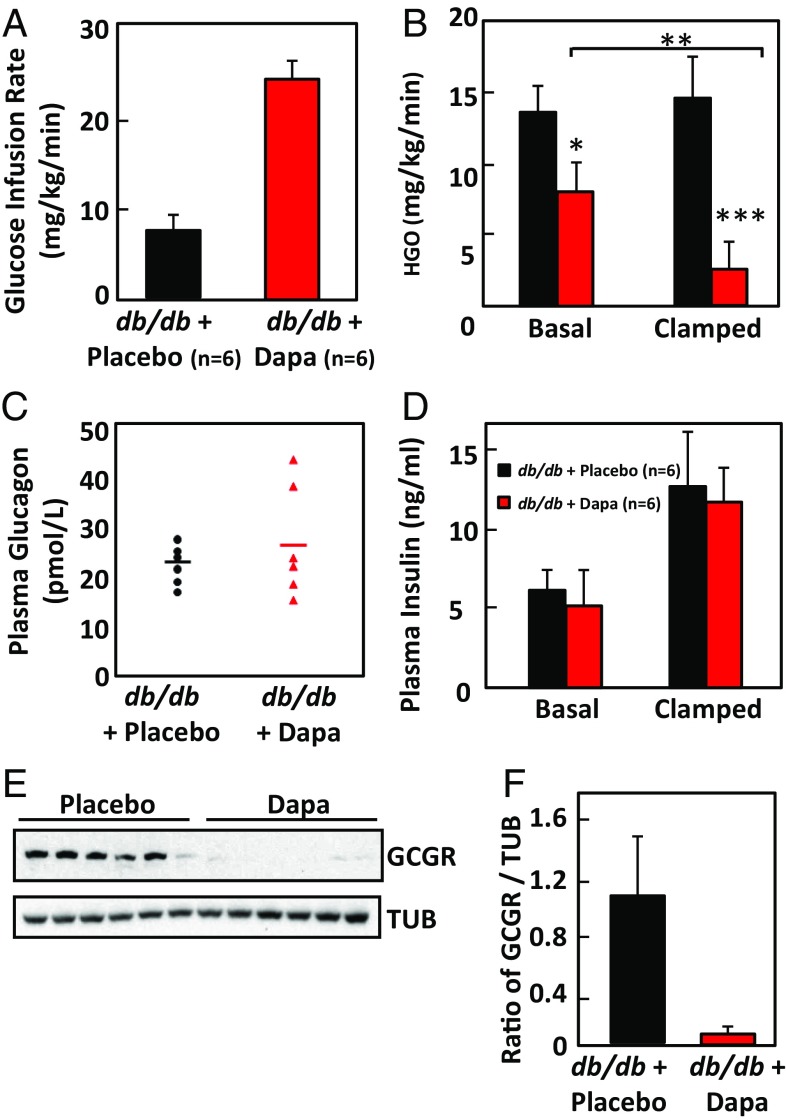

To assess whole-body insulin sensitivity and hepatic glucose production, hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps were performed with 3H-glucose for the assessment of glucose kinetics. The amount of glucose required to maintain isoglycemia (∼233 mg/dL) was 2.9-fold greater in dapagliflozin-treated mice, suggesting an improvement in whole-body insulin action as well as glycosuria (Fig. 4A; P = 0.0005). Part of this improvement was mediated by improved suppression of endogenous glucose production, which was lower in dapagliflozin-treated mice during basal (fasted) and hyperinsulinemic (clamped) conditions (Fig. 4B). As with the ZDFfa/fa rats, dapagliflozin treatment did not lower plasma glucagon concentrations (Fig. 4C), and insulin levels were not changed (Fig. 4D). However, when glucagon receptor expression was examined in the livers of these animals by immunoblotting, it was found to be significantly reduced compared with expression in livers of animals treated with placebo (Fig. 4 E and F). Thus, if the livers of dapagliflozin-treated animals were binding less glucagon, but plasma glucagon levels were not changing significantly, glucagon production was likely to be lower in those animals.

Fig. 4.

Dapagliflozin improves glucose disposal and suppresses endogenous glucose production without changing plasma glucagon levels in db/db mice. (A) Increased glucose infusion is required to maintain euglycemia in db/db mice treated for 4 wk with dapagliflozin compared with wild-type controls (P < 0.0005). Mean values ± SDs are graphed. (B) Endogenous glucose production is lower in dapagliflozin-treated (red bar) than in control (black bars) db/db mice in the basal (fasted) condition and in hyperinsulinemic (clamped) conditions. Mean values ± SDs are graphed. *P < 0.04; **P < 0.003; ***P < 0.0005. (C) The scatter plot shows plasma glucagon concentrations for the same mice as shown in A and B, measured with a Mercodis ELISA kit. Bars indicate means. P = 0.25. (D) Plasma insulin levels for the placebo (black) and dapagliflozin-treated animals (red) are for basal conditions and after the animals were clamped. The difference between two groups was not significantly different by two-tailed t test (P = 0.35 for basal condition; P = 0.76 for the clamped condition). (E) Liver samples from the these mice were probed by immunoblot with anti-glucagon receptor antibody, and the density of the protein bands for the receptor and tubulin loading control were measured by densitometry and graphed, with SDs in F. P < 0.002 by two-tailed t test.

Dapagliflozin Treatment Improves Cardiac Function in Both Models of Type 2 Diabetes.

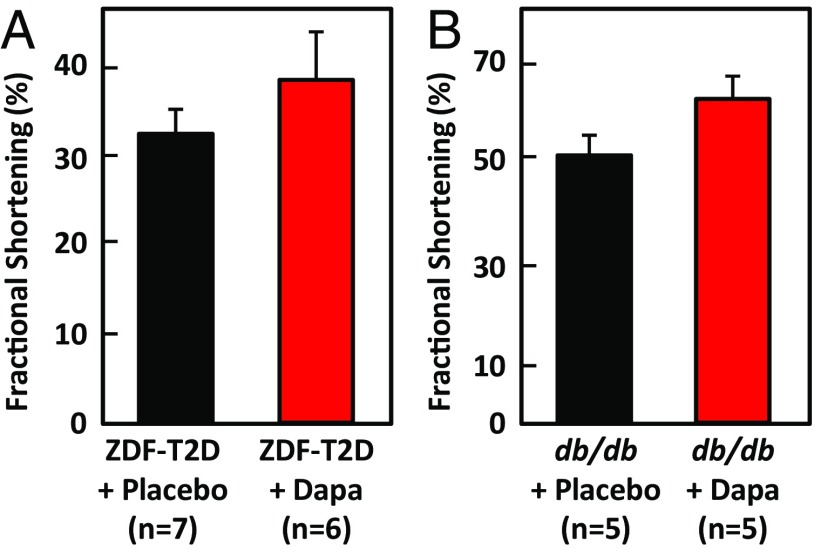

A recent clinical trial with the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin showed a reduction in mortality resulting from cardiovascular events is unlikely to be caused by reduction of blood pressure or known metabolic effects of the drug (16–18). Drucker and colleagues had shown previously that mice with selective inactivation of the glucagon receptor in cardiomyocytes had improved survival and reduced infarct size after myocardial infarction, and that administering exogenous glucagon impaired the recovery of ventricular pressure in ischemic mouse hearts (19). Because we observed suppressed signs of glucagon signaling in the livers of obese ZDF rats and db/db mice treated with dapagliflozin, we investigated the effect of 7 (rats) or 4 (mice) wk of treatment of dapagliflozin on heart function, using echocardiography. Obese ZDFfa/fa rats have enlarged hearts with reduced fractional shortening, an index of contractile dysfunction (20). After 7 wk of treatment with dapagliflozin, obese ZDFfa/fa rats showed an improvement in fractional shortening of ∼30% compared with the animals treated with placebo (Fig. 5A; P = 0.03). A similar improvement in cardiac function was observed in db/db mice treated with dapagliflozin (Fig. 5B; P = 0.001).

Fig. 5.

Dapagliflozin improves cardiac function. (A) Dapagliflozin improves cardiac function in diabetic Zucker rats. At the end of the 7-wk drug treatment, cardiac fractional shortening of the left ventricles was measured. Means with SD for seven placebo-treated and six dapagliflozin-treated animals show a significant improvement (P = 0.008). (B) At the end of 4-wk treatment with dapagliflozin or placebo, cardiac fractional shortening of the left ventricles was measured in db/db mice. Means with SD for five placebo-treated and five dapagliflozin-treated animals show a significant improvement (P = 0.0014).

Discussion

Recent clinical studies reported that SGLT2 inhibitors stimulate endogenous glucose production and increase plasma glucagon, suggesting that inhibiting SGLT2 induces a feedback mechanism partially compensating for the loss of glucose in the urine (4, 5, 21). This concept was supported by studies using human islets that detected SGLT2 in alpha cells and reported increased secretion of glucagon in response to either chemical or siRNA inhibition of SGLT2 (6, 7). However, we had conducted a high-throughput screen for inhibitors of glucagon secretion (12) and identified a chemical reported as an inhibitor of SGLT2 among our positive compounds (13). Thus, we have investigated the direct effect of dapagliflozin on alpha cells in perfused pancreata from rats with chemically induced type 1 diabetes. This model was chosen because insulin is a powerful inhibitor of glucagon secretion, and prior studies of the effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on alpha cells were performed in the presence of beta cells. The inhibition of glucagon secretion from islets observed when glucose concentrations rise is a result of the response of the beta cell releasing insulin. In the absence of insulin, glucose in the physiologic or supraphysiologic range stimulates, rather than inhibits, glucagon secretion (8, 9). SGLT2, having a Km for glucose in the physiologic range, is suitable to be a sensor for physiologically relevant changes in glucose by alpha cells. We found that in rat pancreata, the direct effect of dapagliflozin on alpha cells was to suppress glucagon secretion, and that SGLT2 was the sensor for elevated glucose linked to glucagon secretion. We also found that the molecular signs of gluconeogenesis were inhibited in livers of ZDFfa/fa rats treated for 7 wk with dapagliflozin. Treatment with dapagliflozin also increased hepatic glycogen content, consistent with decreased glucagon signaling. In db/db mice, the overall improvement in weight and glucose homeostasis with dapagliflozin treatment was accompanied by better glucose disposal and a decrease in hepatic glucose output, again consistent with decreased glucagon signaling. In both models of diabetes, dapagliflozin improved cardiac function; one way this could occur is through suppression of glucagon signaling in the heart (19). However, plasma glucagon levels did not change in either rodent model of diabetes with dapagliflozin treatment.

One explanation for decreased glucagon signaling without a change in plasma glucagon levels would be if in animals treated with dapagliflozin, less glucagon is being taken up by the liver. If a decrease in secretion of glucagon was roughly matched by the decrease in hepatic uptake, plasma glucagon levels would not change significantly. Consistent with this explanation, we found that expression of the glucagon receptor protein in the liver of diabetic db/db mice treated with dapagliflozin was significantly decreased. SGLT2 is not reported to be expressed in liver, although publicly available sequencing databases differ as to whether or not mRNA for SGLT2 is present. Thus, it is an open question of whether effects of dapagliflozin on the liver are direct or indirect. Because we observe an improvement in insulin sensitivity in dapagliflozin-treated animals, it is possible that the effects in liver are insulin driven. In any event, additional investigation is needed of the mechanism of decreased hepatic and potentially cardiac glucagon signaling after treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors.

In summary, the results of our experiments in rodents differ from recent reports in humans that endogenous glucose production is increased by dapagliflozin. It is possible that rodents differ from humans in this mechanism of regulation of glucagon signaling, but given the inherent greater noise in studies of genetically diverse and clinically different diabetic human patients, the issue of the magnitude and direction of effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on glucagon signaling deserves additional investigation.

Methods

siRNA Knockdown of SGLT2.

SGLT2 siRNA oligonucleotides were purchased from Dharmacon with the sequences AACCTAGATGCTGAGAGTTA (Si1), AAGAGAATGGAGGAACGCATA (Si2), AAGCACTGATGTACACAGACA (Si3), and AACAGATGAAGTCGCGTGTGT (Si4). As a control, AllStar Negative control oligonucleotide was purchased from Qiagen (cat SI03650318). InR1-G9 cells were grown in DMEM (5 mM glucose) supplemented with 10% FBS in six-well plates (Corning 353046) and transfected with either control siRNA or siRNAs targeting SGLT2, using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Triplicate samples of cells were treated with 100 nM of the individual oligonucleotides for 3 d, and then the medium and oligonucleotides were replaced for an additional 3 d. The cells were then removed from the plates with a solution containing trypsin and EDTA in PBS and replated on 12-well plates (Corning 353043) in either DMEM containing 5 mM glucose or DMEM containing 25 mM glucose. A portion of the cells was retained for processing for SDS/PAGE and immunoblotted for SGLT2, using an antibody from Novus Biologicals (NBP1-68682), with actin (MP Biomedicals 69100) serving as a loading control.

Glucagon Measurements.

After incubation for 18 h, 150 µL medium was taken from the cell samples and centrifuged at 6,600 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and glucagon present in the sample was measured by ELISA using a kit from Cisbio Bioassays (62GLCPEG).

Perfusion Experiments.

Wild-type SD rats (strain number CD IGS #001, Charles River) were injected i.v. twice 1 wk apart with streptozotocin (65 mg per kg body weight) to induce severe type 1 diabetes. Insulin was undetectable in the blood collected from SD rats treated with two doses of streptozotocin, as determined by RIA (catalog number RI-13K; EMD Millipore). Seven days after the second dose of streptozotocin, the rats were fasted for 19 h and then anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg body weight) administered intraperitoneally. The pancreas was isolated and perfused in situ at 37 °C. The perfusate contained 1× KRB buffer (118 mmol/L NaCl, 4.7 mmol/L KCl, 2.4 mmol/L CaCl2, 1.18 mmol/L KH2PO4, 1.2 mmol/L MgSO4, 20 mmol/L NaHCO3 at pH 7.2, and d-glucose (2.5 or 25 mmol/L). Perfusates were supplemented with 1% (wt/vol) bovine albumin fraction V and 4.5% (wt/vol) dextran T70 and gassed for 30 min with 95% (vol/vol) O2 and 5% (vol/vol) CO2 at 37 °C. Perfusion was performed with the perfusate flow rate maintained at 3 mL/min and the temperature kept constant at 37 °C. The pancreas was first equilibrated for 10 min in the gassed perfusate with 2.5 mmol/L d-glucose and then divided into control and SGLT2 inhibitor groups. The control pancreas was perfused sequentially with the gassed perfusate with 2.5 and 25 mmol/L d-glucose, each for 15 min. The pancreas in the inhibitor group was incubated with 20 μmol/L dapagliflozin for 15 min in the gassed perfusate with 2.5 mmol/L d-glucose, followed by 15 min treatment of dapagliflozin in the perfusate with 25 mmol/L d-glucose. The effluent samples were collected from the portal vein, without recycling, into prechilled tubes containing 25 mmol/L EDTA and aprotinin, and frozen at −20 °C for later use. The concentrations of glucagon and insulin were measured by homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence fluorescent immunoassay kits (catalog numbers 62GLCPEK and 62INSPEB; Cisbio Bioassays), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

In Vivo Experiments.

All animal experiments were conducted using protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Rats.

Male Zucker fatty rats 13–15 wk old (bred at Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Dallas) with blood glucose levels higher than 500 mg/dL were randomly selected into two groups. The treatment group was fed with dapagliflozin (50 mg/1,000 g diet) mixed with 6% fat powder diet (catalog number LabDiet 5008). The placebo group was pair-fed with the same amount of 6% fat powder diet as was consumed by the dapagliflozin-treated group. At 10 AM on the indicated days of treatment, blood samples were taken from tail veins into tubes containing 0.5M EDTA and aprotinin (Sigma catalog number A6279) followed by centrifugation for 10 min at 4 °C. Blood glucose levels were measured via a handheld glucose meter (Bayer Contour). The percentage of glycated hemoglobin in the blood from the tail vein was determined by the A1CNow+ kit (PTS Diagnostics). The levels of plasma glucagon were measured by Mercodia glucagon ELISA (catalog number 10-1271-01; Mercodia Developing Diagnostic), and the levels of plasma insulin were monitored by ELISA (catalog number 90010; Crystal Chem Inc.).

Mice.

Twelve 5-wk-old male B6 BKS(D)-Leprdb/J db/db homozygous mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (catalog number 000697) and housed in the standard animal facility, where all animals had free access to water and standard laboratory chow and a 12-h light and dark cycle. After 3 wk, mice were divided randomly into two groups. The treatment group was fed dapagliflozin (50 mg/1,000 g diet) mixed with 4% fat power diet (Teklad Global diets 2016; Harlan Labs). The placebo group was pair-fed with the same amount of 4% fat powder diet as was consumed by the dapagliflozin-treated group.

Urine Collection, Urine Glucose Measurement, and Plasma Glucagon Measurement.

B6 db/db mice were individually placed in the metabolic cages. After a day of acclimatization, urine from each mouse was collected every 24 h for 3 d. The daily volumes of urine were noted. Urine glucose levels were monitored by a coupled enzyme system of glucose oxidase and peroxidase (catalog numbers P7119 and F5803; Sigma-Aldrich). The levels of plasma glucagon in the rodents were measured by Mercodia glucagon ELISA (catalog number 10-1271-01; Mercodia Developing Diagnostic).

Hyperinsulinemic-Euglycemic Clamp.

Hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps were performed on conscious, unrestrained db/db mice after 4 wk treatment with dapagliflozin (n = 6) or placebo (n = 6), as previously described (22, 23). Briefly, hyperinsulinemia was initiated by a primed-continuous infusion of insulin (10 mU/kg/min), and both groups were clamped at a blood glucose of 230 mg/dL.

Lean and Fat Body Weight Measurement.

Body fat and lean mass of 12 B6 db/db mice after dapagliflozin or placebo treatment for 4 wk were analyzed using a NMR minispec device (Bruker Corporation).

Echocardiography.

Echocardiography of obese ZDF rats after 7 wk or B6 db/db mice after 4 wk of dapagliflozin or placebo treatments was performed under isoflurane-anesthetized condition. M-mode images of the left ventricle were collected at the level of papillary muscles using a MicroScan MS200 transducer (Vevo 2100). Left ventricular internal diameters at end systole (LVIDs) and LVID at end diastole (LVIDd) were determined from three representative contraction cycles. Fractional shortening was then calculated as (LVIDd-LVIDs)/LVIDd and expressed as percentage.

Immunoblotting Analysis.

Total protein extracts prepared from liver tissues of rats or mice with or without the treatment of SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin were resolved by SDS/PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The blotted membrane was blocked in 1× Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% Tween and 5% (wt/vol) nonfat dry milk (TBST-MLK) for 1 h at room temperature with gentle, constant agitation. After incubation with primary antibodies anti–phospho-CREB, anti-CREB, anti-PEPCK (Cell Signaling Technologies), anti-glucagon receptor (Alomone Labs catalog number AGR-021), or anti–γ-tubulin (Sigma) in freshly prepared TBST-MLK at 4 °C overnight with agitation, the membrane was washed two times with TBST buffer. This was followed by incubating with secondary anti-rabbit or anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated Ig antibodies in TBST-MLK for 1 h at room temperature with agitation. The membrane was then washed three times with TBST buffer, and the proteins of interest on immunoblots were detected by an ECL plus Western blotting detection system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). The corresponding bands were quantified using NIH Image software (version 1.6; available at https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by a research study agreement from AstraZeneca AB.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Madaan T, Akhtar M, Najmi AK. Sodium glucose CoTransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors: Current status and future perspective. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2016;93:244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2016.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tahrani AA, Barnett AH, Bailey CJ. Pharmacology and therapeutic implications of current drugs for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12:566–592. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasan FM, Alsahli M, Gerich JE. SGLT2 inhibitors in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;104:297–322. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrannini E, et al. Metabolic response to sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition in type 2 diabetic patients. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:499–508. doi: 10.1172/JCI72227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merovci A, et al. Dapagliflozin improves muscle insulin sensitivity but enhances endogenous glucose production. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:509–514. doi: 10.1172/JCI70704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonner C, et al. Inhibition of the glucose transporter SGLT2 with dapagliflozin in pancreatic alpha cells triggers glucagon secretion. Nat Med. 2015;21:512–517. doi: 10.1038/nm.3828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pedersen MG, Ahlstedt I, El Hachmane MF, Göpel SO. Dapagliflozin stimulates glucagon secretion at high glucose: Experiments and mathematical simulations of human A-cells. Sci Rep. 2016;6:31214. doi: 10.1038/srep31214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang MY, et al. Glucagon receptor antibody completely suppresses type 1 diabetes phenotype without insulin by disrupting a novel diabetogenic pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:2503–2508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424934112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olsen HL, et al. Glucose stimulates glucagon release in single rat alpha-cells by mechanisms that mirror the stimulus-secretion coupling in beta-cells. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4861–4870. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unger RH, Cherrington AD. Glucagonocentric restructuring of diabetes: a pathophysiologic and therapeutic makeover. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI60016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramnanan CJ, Edgerton DS, Kraft G, Cherrington AD. Physiologic action of glucagon on liver glucose metabolism. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13:118–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01454.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans MR, Wei S, Posner BA, Unger RH, Roth MG. An AlphaScreen assay for the discovery of synthetic chemical inhibitors of glucagon production. J Biomol Screen. 2016;21:325–332. doi: 10.1177/1087057115622201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu JS, et al. Discovery of non-glycoside sodium-dependent glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors by ligand-based virtual screening. J Med Chem. 2010;53:8770–8774. doi: 10.1021/jm101080v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Awar A, et al. Experimental diabetes mellitus in different animal models. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:9051426. doi: 10.1155/2016/9051426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han S, et al. Dapagliflozin, a selective SGLT2 inhibitor, improves glucose homeostasis in normal and diabetic rats. Diabetes. 2008;57:1723–1729. doi: 10.2337/db07-1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdul-Ghani M, Del Prato S, Chilton R, DeFronzo RA. SGLT2 inhibitors and cardiovascular risk: Lessons learned from the EMPA-REG OUTCOME Study. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:717–725. doi: 10.2337/dc16-0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scheen AJ. Reduction in cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial: A critical analysis. Diabetes Metab. 2016;42:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scheen AJ. Effects of reducing blood pressure on cardiovascular outcomes and mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes: Focus on SGLT2 inhibitors and EMPA-REG OUTCOME. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2016;121:204–214. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2016.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ali S, et al. Cardiomyocyte glucagon receptor signaling modulates outcomes in mice with experimental myocardial infarction. Mol Metab. 2014;4:132–143. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou YT, et al. Lipotoxic heart disease in obese rats: Implications for human obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1784–1789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrannini E, et al. Shift to fatty substrate utilization in response to sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition in subjects without diabetes and patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2016;65:1190–1195. doi: 10.2337/db15-1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holland WL, et al. Receptor-mediated activation of ceramidase activity initiates the pleiotropic actions of adiponectin. Nat Med. 2011;17:55–63. doi: 10.1038/nm.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kusminski CM, et al. MitoNEET-driven alterations in adipocyte mitochondrial activity reveal a crucial adaptive process that preserves insulin sensitivity in obesity. Nat Med. 2012;18:1539–1549. doi: 10.1038/nm.2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]