Abstract

Amyloid-beta (Aβ) peptides, Aβ40 and the more neurotoxic Aβ42, have been the subject of many research efforts for Alzheimer's disease. In two recent independent investigations, the atomistic structure of Aβ42 fibril has been clearly established in the S-shaped conformation consisting of three β-sheets stabilized by salt bridges formed between the Lys28 sidechain and the C-terminus of Ala42. This structure distinctively differs from the long-known structure of Aβ40 in the β-hairpin shaped conformation consisting of two β-sheets. Recent in silico investigations based on all-atom models have reached closer agreement with the in vitro measurements of Aβ40 thermodynamics. In this study, we present an in silico investigation of Aβ42 thermodynamics. Using the established force field parameters in seven sets of all-atom simulations, we examined the stability of small Aβ42 oligomers in physiological saline. We computed the elongation affinity of the S-shaped Aβ42 fibril, reaching agreement with the experimental data. We also estimated the Arrhenius activation barrier along the elongation pathway (from the disordered conformation of a free Aβ42 peptide to its S-shaped conformation on a fibril) that amounts to about 16 kcal/mol, which is consistent with the experimental data. Based on these quantitative agreements, we conclude that aggregation of Aβ42 peptides into fibrils is thermodynamically slow without precipitation by extrinsic factors such as heparan sulfate proteoglycan and highlight the possibility to prevent Aβ42 aggregation by eliminating some precipitation factors or by increasing competitive agents to capture and transport free Aβ42 peptides from the cerebrospinal fluid.

Keywords: Amyloid beta, Peptides, Affinity, Protein Interaction, Molecular Dynamics

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Formation of amyloid-beta (Aβ) fibrils has been identified as a hallmark of Alzheimer's disease (AD) pathology. The 42-residue peptide Aβ1–42 and the 40-residue peptide Aβ1–40 have both been subject to extensive investigations[1-3]. The β-hairpin shaped structures of the truncated Aβ9–40 and Aβ17–42 fibrils were resolved in multiple NMR experiments[4-6] and, based on the NMR structure coordinates, many in silico studies were accomplished (e. g. [7-15]). Through in silico experiments, peptides without N-terminal residues such as Aβ9–40 were found capable of forming stable filaments/fibrils.[7, 8, 15] While all-atom models are crucial for elucidating atomistic details, one can probe much longer time scales with the coarse-grained models[16-18], implicit water[19, 20], or the hybrid models[21].

Through in vitro experiments of biochemical kinetics, the elongation processes of both Aβ40 and Aβ42 fibrils were carefully characterized.[22-30] The elongation affinities were found to correspond to the Gibbs free energies of −9 kcal/mol for Aβ40[25] and −11.8 kcal/mol for Aβ42[27] respectively. An earlier all-atom in silico study[9] of the Aβ17–42 filament based on the β-hairpin structure[5] gave atomistic insights into the intra- and the inter-peptide interactions along with the relative free energies of elongation among various Aβ mutants. The estimated absolute free energy of elongation was −50.5 kcal/mol for the wild type Aβ. A recent all-atom in silico investigation[13] of the Aβ9–40 filament based on the structure of Ref.[6] gave atomistic details of the docking and locking mechanisms[21] and the free-energy landscape along the dissociation pathway of an Aβ40 peptide from the β-hairpin shaped filament. This study also gave estimated free energies of elongation: −13.7 kcal/mol on the even end and −14.8 kcal/mol on the odd end. All these indicate that all-atom in silico studies can reach quantitative agreement with in vitro experiments when the statistical mechanics is implemented with sufficient accuracy.

Very recently, the Aβ1–42 fibril structure has been resolved to atomistic resolution[31-33] that is distinctively different from the β-hairpin characteristics of Aβ1–40 or Aβ17–42. Aβ1–42 fibril is characterized with an S-shaped conformation involving a salt bridge formed between the negatively charged terminal carboxyl group of Ala42 and the positively charged sidechain of Lys28. In this paper, we report an all-atom in silico study based on the S-shaped structure of Aβ1–42. We computed the free energy of elongation, namely, the Gibbs free energy of adding a peptide onto a fibril. The result of −11.3 kcal/mol agrees with the in vitro data of −11.8 kcal/mol. We also examined the free-energy landscape along a path from the random-coil conformation of a free Aβ42 peptide to the S-shaped conformation without a “chaperon”. We estimated the barrier separating the two conformations to be around 16.2 kcal/mol which is consistent with the in vitro data of 23 kcal/mol[23] and 15.8 kcal/mol[29]. With this, we confirmed the quantitative accuracy of the CHARMM force field parameters for peptide-peptide interactions in physiological saline. In addition, we searched for the smallest oligomers that are stable by themselves for further growth into Aβ42 fibrils by conducting four separate in silico experiments of Aβ11–42 monomer, dimer, trimer, and tetramer in physiological saline. Furthermore, we explored the possibility that an S-shaped filament facilitates the formation of new S-shaped oligomers by simulating a peptide monomer/dimer placed in the proximity of an S-shaped filament.

Methods

System setup

For the affinity study, we took the S-shaped fibril structure consisting of two filaments [31] (PDB code: 5KK3), rotated it so that the filament axis is along the z-axis of our coordinate system, placed the protein in the center of a 100Å×100Å×130Å box of water, neutralized the charge with 18 Na+ ions, and salinated the system into 150 mM of NaCl. The model system so constructed has 123,338 atoms in total. After equilibration under 1 bar of constant pressure, the system settled down to the size of 98.3Å×98.3Å×127.3Å. In similar manners, we constructed four model systems of small oligomers and two model systems for a monomer/dimer interacting with an S-shaped filament, all in 150 mM saline.

Simulation parameters

In all the equilibrium molecular dynamics (MD) and nonequilibrium steered molecular dynamics (SMD) runs, we used the CHARMM force field [34, 35] for all the intra- and inter-molecular interactions. We implemented the Langevin stochastic dynamics with NAMD[36] to simulate the systems at a constant temperature of 298 K and a constant pressure of 1 bar. We implemented full electrostatics by the means of particle mesh Ewald (PME)[37] at the grids of 128×128×128. The time step was 1 fs for short-range and 2 fs for long-range interactions. The PME was updated every 4 fs. The damping constant was 5/ps. Explicit solvent was represented with the TIP3P model. [38] In the SMD runs (pulling peptide P1 away from the fibril), the alpha carbons on three peptides of each filament (P7, P8, P8, P16, P17, and P18) were fixed to their coordinates of the fully equilibrated structure. The pulling velocity was chosen as vd = (0, 0, ± 2.5Å/ns) along the z-axis.

Computation of elongation affinity

We followed the procedure of the hybrid SMD (hSMD) detailed in Refs. [39, 40]. Briefly, we conducted MD runs to sample the fluctuations of the peptides in the bound state and in the dissociated state. We conducted SMD runs to pull peptide P1 from the one chosen bound state (the SMD starting point) along a chosen dissociation path to the one corresponding dissociated state (the SMD endpoint), disallowing any fluctuations of the pulling centers along the pulling paths. In this way, we computed the difference in potential of mean force (PMF) ΔPMF0,∞ between the one dissociated state and the corresponding one bound state via the Brownian dynamics fluctuation-dissipation theorem (BD-FDT) [41]. We computed the partial partitions in the bound state from the fluctuations around the one chosen bound state which is the starting point of the SMD runs and the partial partition functions in the dissociated state from the fluctuations around the one dissociated state which is the endpoint of the SMD runs. The bound state partial partition Z0 was evaluated with the Gaussian approximation. The unbound state partial partition Z∞ involved multiple SMD runs between intermediate confirmations and MD runs around those conformations of a free Aβ42 peptide in physiological saline. The dissociation constant was obtained as kD = Z∞ exp[ΔPMF0,∞ / kBT] / Z0 or, equivalently, the free energy of elongation ΔG = ΔPMF0,∞ + kBTln(Z∞ / c0Z0). Here c0 = 1 mol/L=6.02×10−4 / Å3 is the standard concentration. kB is the Boltzmann constant. T is the absolute temperature.

Results and Discussion

Elongation affinity

In order to determine the free energy of elongation (namely, the free energy required to add a monomer Aβ peptide to the end of an S-shaped filament), we computed the PMF along a dissociation path from one chosen bound state (P1 on the filament) to the corresponding one unbound state (P1 away from the filament) by pulling the eight α-carbons on P1 away from the end of the fibril (Fig. 1). The PMF curve along the pulling path is shown in Fig. 2 (A). The PMF difference between the two ends of this dissociation path was found to be ΔPMF0,∞ = −65.7 kcal/mol. Along this dissociation path, the eight α-carbons on His13, Phe20, Asp23, Val24, Asn27, Leu34, Gly38, and Ala42 of P1 were not allowed to fluctuate. Their fluctuations were instead taken into account in the partial partitions Z0 of the bound and Z∞ of the unbound states, respectively. During the SMD pulling, the same set of eight α-carbons on peptide P2 were fixed, not allowed to fluctuate as well. Therefore, their fluctuations in the bound and the unbound states were also included in Z0 and Z∞, respectively. The fluctuations of the two sets of α-carbons on P1 and P2 can be approximated as Gaussian in the bound state ensemble (shown in supplemental information (SI), Figs. S1 to S16). They altogether gave Z0 = 9.6×103 Å48. In the unbound state ensemble, only the fluctuations of the second set of α-carbons (those on peptide P2) can be approximated as Gaussian (SI, Figs. S9 to S16), giving rise to Z∞P2 = 3.8×106 Å24. In this case, however, the contributions to Z∞ from P1 and P2 are separable. Namely, Z∞ = Z∞P1Z∞P2. The partial partition Z∞P1 involves not only the fluctuations of the α-carbons but also the conformational changes from the S-shape peptide (in the mold of the fibril, Fig. 2 (E) inset) to the random coil of a free Aβ peptide in a saline solution (Fig. 2(B), insets). Combining the four sets of data shown in Fig. 2 (B) to (E), we obtained Z∞P1= 3.9×1033 Å21. Altogether, the free energy of elongation, namely, the free energy required in the molecular event of adding a monomer Aβ peptide onto the S-shaped fibril,

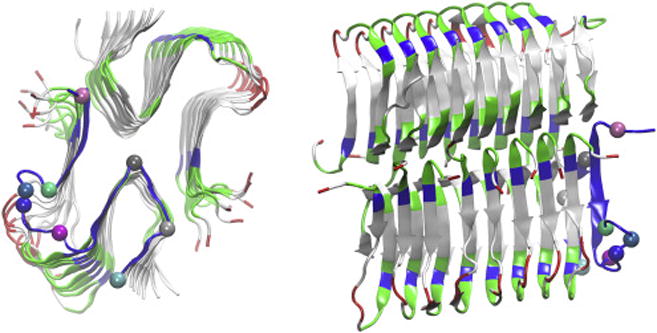

Fig. 1.

Ribbon representation of the S-shaped conformation of 18 Aβ11-42 peptides (P1 to P18) assembled into fibril-filaments. The top view (from the z-axis) and the side view are in the left and the right panels respectively. Peptides P2 to P18 are colored by residue types (hydrophilic, green; hydrophobic, white; positively charged, blue, negatively charged, red). The P1 ribbon is colored in blue on which the α-carbons of His 13, Phe 20, Asp 23, Val 24, Asn 27, Leu 34, Gly 38, and Ala 42, represented as large spheres, are chosen as the pulling centers. In the right panel, bottom array, from right to left are P1 to P9 and in top array, from right to left are P10 to P18. All molecular graphics in this paper were generated with VMD.[42]

Fig. 2.

PMF curves. (A) PMF along the dissociation path of the outermost Aβ11-42 peptide monomer P1 from the end of the Aβ fibril. Inset: each Aβ peptide is represented as spheres colored distinctively. In particular, P1 is colored blue. (B)-(E) PMFs along the conformational changes of Aβ11-42 (represented as ribbons in insets) from the random coil state of the free Aβ peptide to the S-shaped monomer ready for adhesion onto the end of a fibril. (B) PMF as a function of distance between Ala42Ca and Leu34Ca while all other pulling centers are free to fluctuate. (C) PMF as a function the distance between Asn27Ca and Leu34Ca while Ala42Ca is fixed and all other pulling centers are free to fluctuate. (D) PMF as a function of Phe20Ca displacement while Ala42Ca, Asn27Ca, and Leu34Ca are fixed and all other pulling centers are free to fluctuate. (E) PMF as a function of Asp23Ca-Val24Ca displacement while all other pulling centers are fixed. In (B), (C), and (E), Aβ11-42 peptide is colored by residue types as in Fig. 1. In (D), the peptide is colored respectively in cyan in the conformation of zero displacement and in blue in the conformation of displacement at 5.4 Å. The error bars represent standard errors among four sets of SMD runs.

Correspondingly, the dissociation constant kD = 6.9×10−9 mol/L. This value is in close agreement with the experimental data of koff / k+ = 3.3×10−9 mol/L derived from the on rate k+ and the off rate koff [27]. This agreement demonstrates that the all-atom force-field parameters employed in our study are quantitatively accurate for protein-protein interactions in physiological saline.

Activation barrier for elongation

It should be noted that, in the all-atom studies of the β-hairpin shaped filaments of the truncated Aβ40/42 peptides, the free-energy landscape along the one-dimensional (1D) dissociation path (inverse of the association path) was monotonic, suggesting the absence of an activation barrier along the association path of adding an Aβ peptide unto the end of an Aβ filament. In contrast, our PMF in Fig. 2(A) is a curve along the 24D phase space. The 24D PMF being monotonic does not indicate the absence of activation barriers in the pathway of adding an Aβ42 peptide unto the S-shaped Aβ filament because along this path 24 degrees of freedom of the peptide were not allowed to fluctuate. The use of this fluctuation-less path is correct only in combination with fully sampling the fluctuations in the bound state and in the unbound state. While the fluctuations of the 24D degrees of freedom in the bound state are Gaussian and barrier-less, the fluctuations in the unbound state are highly nontrivial and non-Gaussian. They involve conformational changes of the Aβ42 peptide from its S-shape in Fig. 2 (E) to the random coil in Fig. 2(B). Following the PMF curves from Point (4.0 Å, 0 kcal/mol) to Point (0 Å, -11.5 kcal/mol) in Fig. 2(E), then from Point (5.4 Å, 0 kcal/mol) to Point (0 Å,-2.4 kcal/mol) in Fig. 2(D), then from Point (18.3 Å, 0 kcal/mol) to Point (16.2 Å, -0.7 kcal/mol) in Fig. 2(C), and then from Point (21.6 Å, 0 kcal/mol) to Point (18.3 Å, -1.6 kcal/mol) in Fig. 2(B), the total change in PMF is approximately 16.2 kcal/mol. Altogether, the PMF of an Aβ42 peptide in the S-shaped conformation (Fig. 2(E)) is 16.2 kcal/mol above that in the random coil conformation (Fig. 2(B)). Considering the barriers of 0.95 kcal/mol in Fig. 2(D) and 16 kcal/mol in Fig. 2(E), we estimate that the Arrhenius activation energy of the elongation process is about 16.2 kcal/mol but certainly less than 33.2 kcal/mol. This estimation is consistent with the in vitro data of 23 kcal/mol[23] and 15.8 kcal/mol[29].

Stability of oligomers in physiological saline

Conducting four in silico experiments of a monomer, dimer, trimer, or tetramer of Aβ42 peptides (shown in SI, Fig. S17) in physiological saline, we examined the stability and conformations of small oligomers of Aβ11-42 peptides. (For convenience, here an “oligomer” means either a monomer, dimer, trimer or tetramer.) Starting from the S-shaped conformation, a monomer rapidly became a random coil (Fig. S17(A)); a dimer quickly lost its S-shape but approximately retained its dimeric form (Fig. S17(B)); a trimer deviated significantly from its initial S-shaped conformation (Fig. S17(C)); a tetramer, however, was essentially stable (Fig. S17(D)). Quantitatively, Fig. 3 shows the number of hydrogen bonds per peptide that are formed within an oligomer in contrast with the number of hydrogen bonds per peptide that are formed between the peptides and their aqueous environment. Fig. 4 shows the peptide root mean square deviation (RMSD) as a function of time. The number of hydrogen bonds per peptide that are formed between waters and an oligomer fluctuates at a level that is dependent on the size of the oligomer with a monomer having the greatest value. The number of hydrogen bonds per peptide that are formed within an oligomer also fluctuates at a size-dependent level. And the level is time dependent in the course when the conformation of an oligomer deviates from the initial structure. In particular, the number of hydrogen bonds per peptide that are formed within a trimer dropped about 50% (Fig. 3, third panel). This decrease is consistent with increased fluctuations visible in the atomistic trajectories. In contrast, the same number within a tetramer remained unreduced. While a trimer is somewhat stable, a tetramer of the S-shaped Aβ peptides is very stable in physiological saline. In contrast to the β-hairpin shaped Aβ40 peptides that need a minimum of six peptides to be a stable aggregate [8], a tetramer of the S-shaped Aβ42 peptides is the minimal oligomer that is stable in physiological saline for subsequent elongation growth into a mature fibril-filament.

Fig. 3.

Number of hydrogen bonds per peptide that are formed within an oligomer vs those formed with waters.

Fig 4.

RSMD of Aβ11-42 oligomers. Top panel, oligomers in saline (illustrated in Fig. S17). Bottom panel, a monomer/dimer placed beside and interacting with an S-shaped filament shown in the insets. The filaments are shown as yellow cartoons while the monomer/dimer peptides are represented as blue ribbons.

Fibrils facilitate nucleation of Aβ peptides

To explore how an Aβ42 fibril/filament might facilitate nucleation of Aβ peptides/formation of new oligomers, we removed all but one or two monomers from one filament of the Aβ fibril (PDB code: 5KK3) consisting of two filaments of S-shaped Aβ42 peptides. We placed the so-formed monomer-filament and dimer-filament complexes in a box of water salinated with 150 mM NaCl. We ran 50 ns of equilibrium MD for each model system and obtained the RMSDs of the monomer/dimer from its initial S-shaped conformation which are shown in Fig. 4. These results demonstrate that a monomer does not assume the S-shaped conformation even in the proximity of a long filament of S-shaped Aβ42 peptides. Remarkably, a dimer of Aβ42 peptides showed stability and retained its S-shaped conformation. This in silico observation of the stability of an Aβ42 dimer interacting with a long filament is consistent with the in vitro experimental elucidation that fibrils facilitate nucleation of Aβ42 peptides, simultaneously taking two monomers in the initial step of oligomer formation.[27]

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Aβ42 fibril elongation affinity was computed with chemical accuracy, in agreement with in vitro data

Small Aβ42 oligomers were found to be stable in physiological saline

A long Aβ42 fibril-filament was shown to stabilize an Aβ dimer in its proximity

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support from the NIH grants (GM084834, RR013646, MD007591), San Antonio Life Sciences Institute (SALSI) Brain Health-Clusters in Research Excellence, Semmes Foundation, and the computing resources provided by the Texas Advanced Computing Center at University of Texas at Austin.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Declaration: The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Morgan C, Colombres M, Nuñez MT, Inestrosa NC. Structure and function of amyloid in Alzheimer's disease. Progress in Neurobiology. 2004;74:323–349. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reinhard C, Hébert SS, De Strooper B. The amyloid β precursor protein: integrating structure with biological function. The EMBO Journal. 2005;24:3996–4006. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turner PR, O'Connor K, Tate WP, Abraham WC. Roles of amyloid precursor protein and its fragments in regulating neural activity, plasticity and memory. Progress in Neurobiology. 2003;70:1–32. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petkova AT, Ishii Y, Balbach JJ, Antzutkin ON, Leapman RD, Delaglio F, Tycko R. A structural model for Alzheimer's β-amyloid fibrils based on experimental constraints from solid state NMR. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002;99:16742–16747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262663499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lührs T, Ritter C, Adrian M, Riek-Loher D, Bohrmann B, Döbeli H, Schubert D, Riek R. 3D structure of Alzheimer's amyloid-β(1–42) fibrils. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:17342–17347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506723102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petkova AT, Yau WM, Tycko R. Experimental Constraints on Quaternary Structure in Alzheimer's β-Amyloid Fibrils. Biochemistry. 2006;45:498–512. doi: 10.1021/bi051952q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchete NV, Tycko R, Hummer G. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Alzheimer's β-Amyloid Protofilaments. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2005;353:804–821. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchete NV, Hummer G. Structure and Dynamics of Parallel β-Sheets, Hydrophobic Core, and Loops in Alzheimer's Aβ Fibrils. Biophysical Journal. 2007;92:3032–3039. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.100404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lemkul JA, Bevan DR. Assessing the Stability of Alzheimer's Amyloid Protofibrils Using Molecular Dynamics. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2010;114:1652–1660. doi: 10.1021/jp9110794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arya S, Singh AK, Khan T, Bhattacharya M, Datta A, Mukhopadhyay S. Water Rearrangements upon Disorder-to-Order Amyloid Transition. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters. 2016;7:4105–4110. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b02088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phipps MJS, Fox T, Tautermann CS, Skylaris CK. Energy Decomposition Analysis Based on Absolutely Localized Molecular Orbitals for Large-Scale Density Functional Theory Calculations in Drug Design. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2016;12:3135–3148. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sasmal S, Schwierz N, Head-Gordon T. Mechanism of Nucleation and Growth of Aβ40 Fibrils from All-Atom and Coarse-Grained Simulations. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2016;120:12088–12097. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b09655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwierz N, Frost CV, Geissler PL, Zacharias M. Dynamics of Seeded Aβ40-Fibril Growth from Atomistic Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Kinetic Trapping and Reduced Water Mobility in the Locking Step. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2016;138:527–539. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b08717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwierz N, Frost CV, Geissler PL, Zacharias M. From Aβ Filament to Fibril: Molecular Mechanism of Surface-Activated Secondary Nucleation from All-Atom MD Simulations. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2017;121:671–682. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b10189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng W, Tsai MY, Chen M, Wolynes PG. Exploring the aggregation free energy landscape of the amyloid-β protein (1–40) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2016 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1612362113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fawzi NL, Kohlstedt KL, Okabe Y, Head-Gordon T. Protofibril Assemblies of the Arctic, Dutch, and Flemish Mutants of the Alzheimer's Aβ1–40 Peptide. Biophysical Journal. 2008;94:2007–2016. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.121467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fawzi NL, Okabe Y, Yap EH, Head-Gordon T. Determining the Critical Nucleus and Mechanism of Fibril Elongation of the Alzheimer's Aβ1–40 Peptide. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2007;365:535–550. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu C, Shea JE. Coarse-grained models for protein aggregation. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2011;21:209–220. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gurry T, Stultz CM. Mechanism of Amyloid-β Fibril Elongation. Biochemistry. 2014;53:6981–6991. doi: 10.1021/bi500695g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takeda T, Klimov DK. Replica Exchange Simulations of the Thermodynamics of Aβ Fibril Growth. Biophysical Journal. 2009;96:442–452. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han W, Schulten K. Fibril Elongation by Aβ17–42: Kinetic Network Analysis of Hybrid-Resolution Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2014;136:12450–12460. doi: 10.1021/ja507002p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esler WP, Stimson ER, Jennings JM, Vinters HV, Ghilardi JR, Lee JP, Mantyh PW, Maggio JE. Alzheimer's Disease Amyloid Propagation by a Template-Dependent Dock-Lock Mechanism. Biochemistry. 2000;39:6288–6295. doi: 10.1021/bi992933h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kusumoto Y, Lomakin A, Teplow DB, Benedek GB. Temperature dependence of amyloid β-protein fibrillization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1998;95:12277–12282. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cannon MJ, Williams AD, Wetzel R, Myszka DG. Kinetic analysis of beta-amyloid fibril elongation. Analytical Biochemistry. 2004;328:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Nuallain B, Shivaprasad S, Kheterpal I, Wetzel R. Thermodynamics of Aβ(1-40) Amyloid Fibril Elongation. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12709–12718. doi: 10.1021/bi050927h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ban T, Yamaguchi K, Goto Y. Direct Observation of Amyloid Fibril Growth, Propagation, and Adaptation. Accounts of Chemical Research. 2006;39:663–670. doi: 10.1021/ar050074l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen SIA, Linse S, Luheshi LM, Hellstrand E, White DA, Rajah L, Otzen DE, Vendruscolo M, Dobson CM, Knowles TPJ. Proliferation of amyloid-β42 aggregates occurs through a secondary nucleation mechanism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110:9758–9763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218402110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meisl G, Yang X, Hellstrand E, Frohm B, Kirkegaard JB, Cohen SIA, Dobson CM, Linse S, Knowles TPJ. Differences in nucleation behavior underlie the contrasting aggregation kinetics of the Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014;111:9384–9389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401564111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buell AK, Dhulesia A, White DA, Knowles TPJ, Dobson CM, Welland ME. Detailed Analysis of the Energy Barriers for Amyloid Fibril Growth. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2012;51:5247–5251. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qiang W, Kelley K, Tycko R. Polymorph-Specific Kinetics and Thermodynamics of β-Amyloid Fibril Growth. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2013;135:6860–6871. doi: 10.1021/ja311963f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colvin MT, Silvers R, Ni QZ, Can TV, Sergeyev I, Rosay M, Donovan KJ, Michael B, Wall J, Linse S, Griffin RG. Atomic Resolution Structure of Monomorphic Aβ42 Amyloid Fibrils. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2016;138:9663–9674. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b05129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wälti MA, Ravotti F, Arai H, Glabe CG, Wall JS, Böckmann A, Güntert P, Meier BH, Riek R. Atomic-resolution structure of a disease-relevant Aβ(1–42) amyloid fibril. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2016;113:E4976–E4984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600749113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiao Y, Ma B, McElheny D, Parthasarathy S, Long F, Hoshi M, Nussinov R, Ishii Y. A[beta](1-42) fibril structure illuminates self-recognition and replication of amyloid in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22:499–505. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mac Kerell AD, Bashford D, Bellott, Dunbrack RL, Evanseck JD, Field MJ, Fischer S, Gao J, Guo H, Ha S, Joseph-Mc Carthy D, Kuchnir L, Kuczera K, Lau FTK, Mattos C, Michnick S, Ngo T, Nguyen DT, Prodhom B, Reiher WE, Roux B, Schlenkrich M, Smith JC, Stote R, Straub J, Watanabe M, Wiorkiewicz-Kuczera J, Yin D, Karplus M. All-Atom Empirical Potential for Molecular Modeling and Dynamics Studies of Proteins†. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 1998;102:3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Best RB, Zhu X, Shim J, Lopes PEM, Mittal J, Feig M, MacKerell AD. Optimization of the Additive CHARMM All-Atom Protein Force Field Targeting Improved Sampling of the Backbone ϕ, ψ and Side-Chain χ1 and χ2 Dihedral Angles. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2012;8:3257–3273. doi: 10.1021/ct300400x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, Chipot C, Skeel RD, Kalé L, Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Darden T, York D, Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: An N·log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 1993;98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J Chem Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen LY. Hybrid Steered Molecular Dynamics Approach to Computing Absolute Binding Free Energy of Ligand–Protein Complexes: A Brute Force Approach That Is Fast and Accurate. J Chem Theory Comput. 2015;11:1928–1938. doi: 10.1021/ct501162f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodriguez RA, Yu L, Chen LY. Computing Protein–Protein Association Affinity with Hybrid Steered Molecular Dynamics. J Chem Theory Comput. 2015;11:4427–4438. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen LY, Bastien DA, Espejel HE. Determination of equilibrium free energy from nonequilibrium work measurements. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2010;12:6579–6582. doi: 10.1039/b926889h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.