Abstract

Background and purpose

Energy depletion is a critical factor leading to cell death and brain dysfunction after ischemic stroke. In this study we investigated whether energy depletion is involved in hyperglycemia-induced hemorrhagic transformation (HT) after ischemic stroke and determined the pathway underlying the beneficial effects of hyperbaric oxygen (HBO).

Methods

After 2 hours MCAO, hyperglycemia was induced by injecting of 50% dextrose (6 ml/kg) intraperitoneally at the onset of reperfusion. Immediately after it rats were exposed to HBO at 2 atmospheres absolutes (ATA) for 1 hour. ATP synthase inhibitor Oligomycin A (Olig A), NAMPT inhibitor FK866 or Sirt1 siRNA was administrated for interventions. Infarct volume, hemorrhagic volume, neurobehavioral deficits were recorded; the level of blood glucose, ATP and NAD+ and the activity of NAMPT were monitored; the expression of Sirt1, acetylated P53, acetylated NF-κB and cleaved caspase 3 were detected by western blots; the activity of MMP-9 was assayed by zymography.

Results

Hyperglycemia deteriorated energy metabolism and reduced the level of ATP and NAD+, exaggerated hemorrhagic transformation, blood-brain barrier disruption and neurological deficits after MCAO. HBO treatment increased the levels of the ATP and NAD+ and consequently increased Sirt1, resulting in attenuation of hemorrhagic transformation, brain infarction as well as improvement of neurological function in hyperglycemic MCAO rats.

Conclusion

HBO induced activation of ATP/NAD+/Sirt1 pathway and protected blood-brain barrier in hyperglycemic MCAO rats. HBO might be promising approach for treatment of acute ischemic stroke patients, especially patients with diabetes or treated with rtPA.

Keywords: Hyperbaric Oxygen, NAD+, NAMPT, Sirt1 and hemorrhagic transformation

Subject Terms: Animal Models of Human Disease, Ischemic Stroke, Basic Science Research, Mechanisms

Introduction

The energy failure caused by lack of glucose and oxygen and consequently by depletion of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is one of the major events after cerebral ischemia. It initiates multiple intracellular pathways and results in cell death and blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption1. Neurons, compared to another cell types, have higher energy expenditure and contain little energy reserves2. Early restoration of energy greatly contributes to the survival of neurons and determines the outcome of ischemic stroke1.

About 10% to 40% of patients with ischemic stroke will develop to hemorrhagic transformation (HT) and it’s more prevalent in patients with glucose metabolism disorders3, 4. The only one available therapeutic option of ischemic stroke, rtPA, can also induce HT, significantly restricting the clinical usage of rtPA5, 6. Oxidative cascades, leukocyte infiltration, vascular activation, and disregulated extracellular proteolysis might act as a potential trigger of HT and undermine the integrity of blood-brain barrier (BBB)7, 8. New therapeutic strategies capable of BBB preserving and HT ameliorating will benefit a significant number of stroke patients.

Though hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) treatment has been reported to reduce hyperglycemia-enhanced HT and rtPA-related HT in experimental stroke9,10, the underlying mechanisms remain largely unknown. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) is a classic energy metabolite that synthesized from its precursors (nicotinic acid and nicotinamide) by the rate-limiting enzyme nicotinamide phosphoribosyl transferase (NAMPT) 11, 12. NAD+ positively regulates the activity of silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog 1 (Sirt1), and plays critical roles in neuroprotection after ischemic stroke13. HBO increases the expression of Sirt114, but the signaling pathway has not been fully elucidated yet. In the present study, we induced HT by combination of hyperglycemia/ischemia (middle cerebral artery occlusion, MCAO) and hypothesized that 1) Hyperglycemia induces energy deficits causing HT; 2) HBO activates ATP/NAD+/Sirt1 pathway, resulting in the restored energy level and leading to the improved BBB and neurological functions.

Materials and Methods

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Loma Linda University. The model of MCAO on rats was employed. A total of 303 adult male Sprague Dawley rats (2–3 months, weight 250–300 g) were randomly distributed to 11 groups for the study (Supplemental table I). The investigators are blinded to group assignments during outcome assessments. The experimental design was showed in Supplement figure I.

MCAO Animal Model and Hyperglycemia Induction

Transient MCAO was induced as previously described15 (for details please see supplemental information). Hyperglycemia was induced by injection of 50% dextrose (6 ml/kg) intraperitoneally at the beginning of reperfusion. The glucose level was monitored at 0 h, 2 h, 4 h, 6 h and 8 h after injection.

HBO Treatment and Drugs

HBO should be applied within 3–6 h when the ischemic neuronal tissues can still be saved16. Due to possible toxicity of oxygen, the duration of HBO sessions should ranges from 60 to 90 minutes and the oxygen pressure should not exceed 3 ATA, whereby the most used pressure range from 1.5 to 3 ATA16. In our study rats were exposed to HBO at 2 ATA for 60 min in a research hyperbaric chamber (1300B; Sechrist) at the onset of reperfusion. Compression and decompression were maintained at a rate of 5 psi/min. NAD+(Sigma-Aldrich), ATP synthase inhibitor Oligomycin A (Olig A, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or NAMPT inhibitor FK866 (Tocris Bioscience) was administrated 30 min before HBO treatment. The vehicle group was given 5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich). Based on previous reports indicating that NAD+ administered intraperitoneally at a dosage from 50 mg/kg to 200 mg/kg have beneficial cytoprotective effects, we used 100 mg/kg, which turn out to be effective in our model17, 18. 10 mg/kg of FK866, NAMPT inhibitor, was administrated intraperitoneally as previously described19; Sirt1 siRNAs was administrated intralateroventricularlly20 and Olig A was administrated 1 mg/ml i.p21.

Sirt1 siRNA Injection

Two different formats of Sirt1 siRNAs (OriGene Technologies), in order to enhance the silencing effect, were applied 48 hours before MCAO via intraventricular injection (I.C.V). The injections were performed as previously described20 (Supplemental materials).

2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium Chloride (TTC) Staining

The infarct volume was investigated at 24 hours after MCAO via TTC staining as described before22. The possible interference of brain edema on infarct volume was corrected (whole contralateral hemisphere volume − nonischemic ipsilateral hemisphere volume) and the infracted volume was expressed as a ratio of the whole contralateral hemisphere.

Spectrophotometric Assay of Hemoglobin

Hemorrhagic volume was analyzed by hemoglobin assay as previously described15 (supplemental information). Hemorrhage measurements were performed on brains already stained with TTC for infarct quantitation. It has been shown that TTC staining does not alter the spectrophotometric hemoglobin assay23.

Brain Water Content

Rats were euthanized under deep anesthesia. The brain samples were quickly removed and dissected on ice into four parts: right hemisphere, left hemisphere, cerebellum, and brainstem. The “wet weights” of tissue samples were measured immediately and “dry weights” were obtained after drying in an oven at 105°C for 48 h. The percentage of brain water content of each part was calculated as [(wet weight − dry weight)/wet weight] ×100% 22.

Neurological Scores

A neurological examination was performed by a blinded investigator at 24 hours after MCAO as previously described24. The scoring system consists of 7 sup-tests (spontaneous activity, symmetry in the movement of four limbs, forepaw outstretching, climbing, body proprioception, response to vibrissae touch, and beam walking). The neurological scoring ranged from 3 (most severe deficits) to 21 (normal).

Foot-fault test

For testing of motor coordination, foot-fault test was performed by a blinded investigator 24 hours after MCAO as previously described25 (supplemental information).

Immunofluorescent staining

Immunofluorescent staining was performed on fixed frozen ultrathin sections as previously described26. Primary antibodies used were neuronal nuclei (NeuN, Millipore Chemicon International), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba1, Abcam), NAMPT (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and Sirt1 (Sigma-Aldrich).

Western Blots Analysis

Western Blots was performed as previously described16. The primary antibodies were: NAMPT (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Sirt1 (Sigma-Aldrich), NF-kB-p65 (Sigma-Aldrich), Acetyl-p53 (Cell Signaling Technology), cleaved caspase-3 (CC3, Cell Signaling Technology).

Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) for ATP, NAMPT and NAD+

Brain samples were collected as the same way for western blots 6 hours after MCAO. ELISA for ATP, NAMPT and NAD+ were performed following the manufacturer’s instructions. The levels of ATP and NAD+ was assayed with rat ELISA kits of ATP (MyBioSource Inc) and NAD+ (BioAssay Systems). The activity of NAMPT was detected with rat ELISA kits of NAMPT (MBL International).

Matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) Zymography

MMP-9 zymography was performed as previously described15 (Supplemental material).

Statistical Analyses

The analysis of the data was performed using GraphPad Prism software. Statistical differences between two groups were analyzed using the student`s unpaired, two-tailed t-test. Multiple comparisons (without a rating scale) were statistically analyzed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey method. The data are presented as means ± SEM. Mortality was evaluated by Fisher’s exact test. In all statistical analysis, a value of p< 0.05 represents statistical significance.

Results

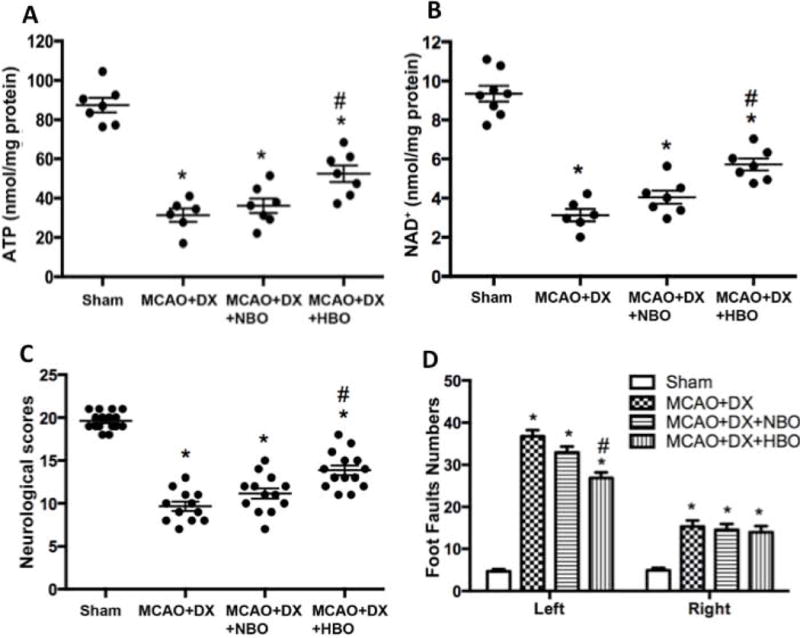

1. HBO treatment attenuated the decline of ATP and NAD+ level in hyperglycemic MCAO rats

Hyperglycemia caused a significant reduction of ATP and NAD+ 6 hours after MCAO (Supplement figure II A and II B, p<0.05 vs. MCAO+Saline). HBO significantly increased the level of ATP and NAD+ 6 hours after MCAO (Figure 1A and 1B, p<0.05 vs. MCAO+DX). The level of blood glucose peaked at 2 hour after DX injection and returned to the baseline 6 hours after injection (Supplement figure III). Neither NBO nor HBO treatment affected the blood glucose level (Supplement figure III).

Figure 1.

HBO attenuated energy depletion, resulting in improved neurological functions in hyperglycemic MCAO rats. Hyperglycemia/MCAO generated a significant depletion of energy evaluated as level of ATP (Figure 2A) and NAD+ (Figure 2B) 6 hours after MCAO, and presented with severe neurological dysfunction assessed by neurological scores (Figure 2C) and Foot-fault test (Figure 2D) 24 hours after MCAO. *p < 0.05 vs. Sham; #p < 0.05 vs. MCAO+DX.

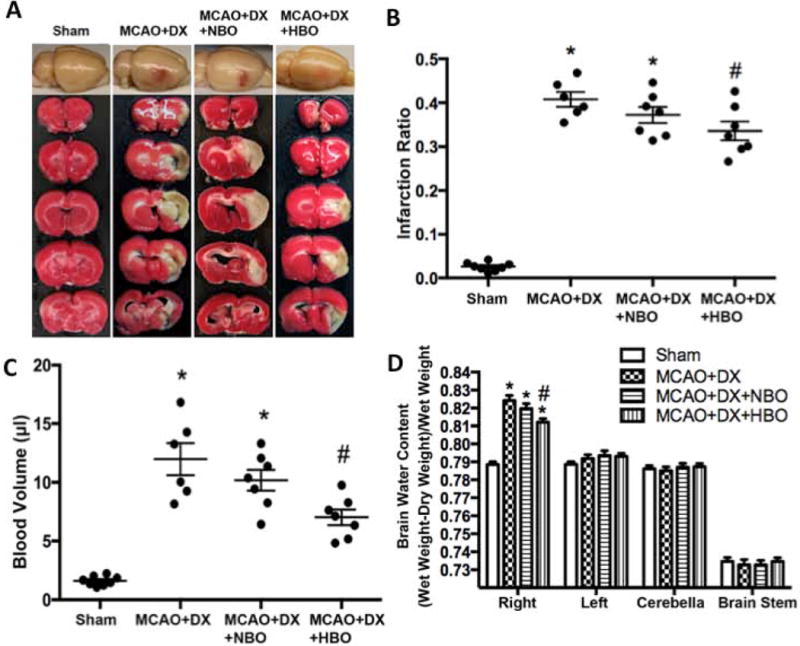

2. HBO treatment decreased infarction volume, protected BBB and improved neurological functions in hyperglycemic rats 24 hours and 72 hours after MCAO

Hyperglycemia enhanced HT (Supplement figure II C and II E) and decreased neurological scores (Supplement figure II F), but has no significant effects on infarction volume 24 hours after MCAO (Supplement figure II C and II D). Compared to hyperglycemic MCAO rats without treatment, HBO treatment reduced infarct volume (Figures 2A and 2B, p<0.05 vs. MCAO+DX), attenuated hemorrhage volume (Figure 2A and 2C, p<0.05 vs. MCAO+DX), and decreased brain water content (Figure 2D, p<0.05 vs. MCAO+DX) 24 hours after MCAO, resulting in the improved neurological functions evaluated by neurological score (Figure 1C, p<0.05 vs. MCAO+DX) and foot-faults (Figure 1D, p<0.05 vs. MCAO+DX). The protective effects of HBO lasted to 72 hours after MCAO (Supplement figure IV).

Figure 2.

HBO decreased infarction and attenuated HT 24 hours after MCAO in hyperglycemic rats. Hyperglycemia/MCAO caused significant brain infarction (Figure 1A and 1B), hemorrhagic transformation (Figure 1A and 1C) and brain edema (Figure 1D). *p < 0.05 vs. Sham; #p < 0.05 vs. MCAO+DX.

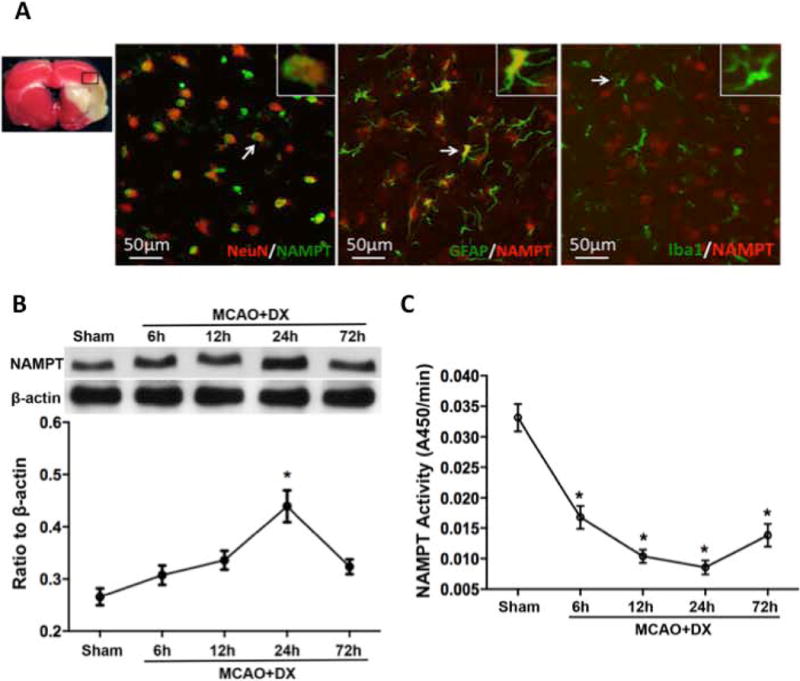

3. Hyperglycemia/MCAO increased the production of neuronal and astrocytic NAMPT, while decreased the activity of NAMPT

Double immunofluorescence staining of NAMPT with NeuN, NAMPT and GFAP, and the results revealed that NAMPT was mainly expressed on neurons and astrocytes, but not on microglial of the penumbra 24 hours after MCAO (Figure 3A). Western blots results demonstrated that NAMPT level was slightly increased as early as 6 hours post-MCAO and reached a peak around 24 hours (2 folds compared to sham animals, Figure 3B, p< 0.05 vs. Sham). The level of NAMPT declined and returned to the baseline level 72 hours after MCAO (Figure 3B, p> 0.05 vs. Sham). The activity of NAMPT was significantly decreased in the ischemic hemisphere from 6 hours post-MCAO compared to Sham animals (Figure 3C, p< 0.05 vs. Sham).

Figure 3.

Hyperglycemia/MCAO increased production of neuronal and astrocytic NAMPT but decreased the activity of NAMPT. NAMPT expression was mostly observed in neurons (NeuN/NAMPT positive cells) and astocytes (GFAP/NAMPT positive cells) of penumbra (Figure 3A). Hyperglycemia/MCAO increased production of NAMPT (Figure 3B) but decreased its activity (Figure 3C). *p < 0.05 vs. Sham.

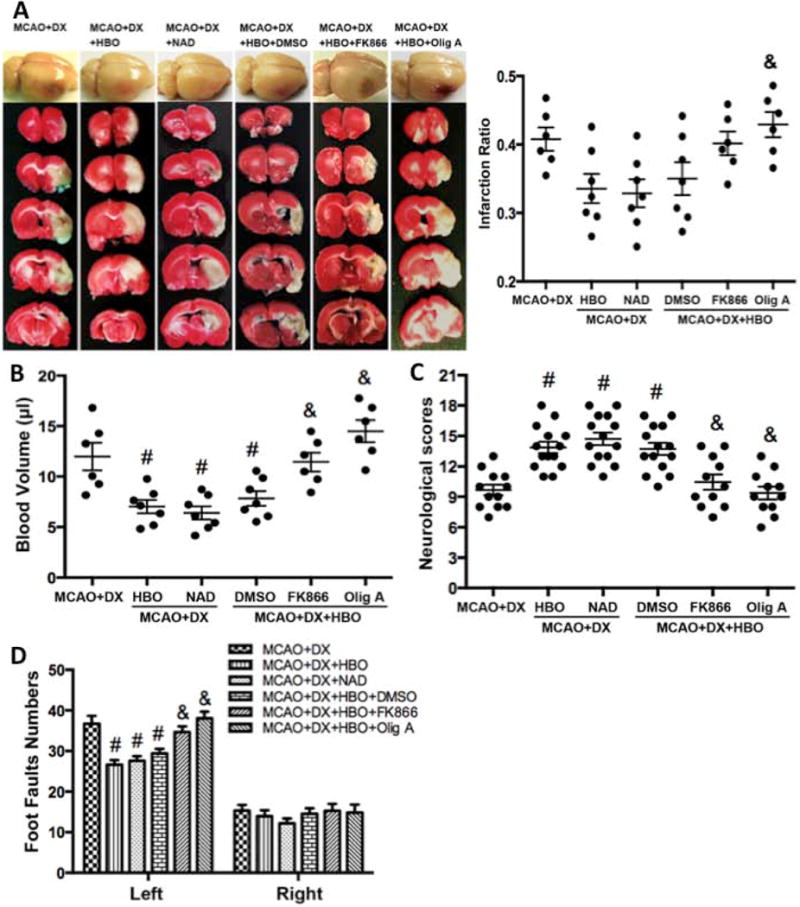

4. Beneficial effects of HBO were dependent on ATP and NAD+

Administration of NAD+ mimicked the effects of HBO that tended to reduce the infarction volume (Figures 4A, p>0.05 vs. MCAO+DX), attenuated hemorrhagic volume (Figures 4B, p<0.05 vs. MCAO+DX), and improved neurological functions (Figures 4C and 4D, p<0.05 vs. MCAO+DX) 24 hours after MCAO. On the other hand, administration of ATP synthase inhibitor Olig A, or NAMPT inhibitor FK866 abolished these beneficial effects of HBO (Figure 4, p<0.05 vs. MCAO+DX+HBO).

Figure 4.

Beneficial effects of HBO were dependent on ATP and NAD+ in hyperglycemic MCAO rats. NAD+ administration mimicked the effects of HBO to reduce infarction volume (Figures 4A) and hemorrhagic volume (Figures 4B), and improved neurological functions in neurological scores (Figures 4C) and food-fault test (Figures 4D) 24 hours after MCAO. NAMPT or ATP synthase inhibition attenuated the beneficial effects of HBO treatment (Figures 4A–D). #p < 0.05 vs. MCAO+DX; &p < 0.05 vs. MCAO+DX+HBO.

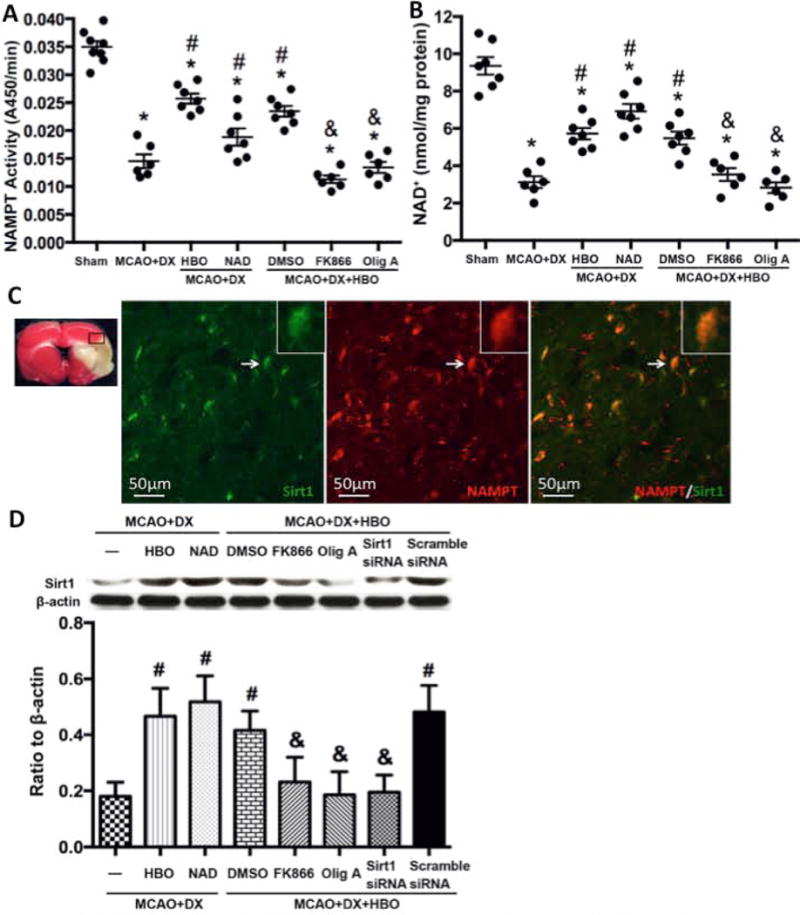

5. HBO’s ability to restore and production of NAD+ depends on ATP and NAMPT

The activity of NAMPTA and the level of NAD+ in brain tissue were greatly decreased after MCAO in hyperglycemic rats (Figure 5A and 5B, p<0.05 vs. Sham). HBO treatment significantly increased the activity of NAMPT (Figure 5A, p<0.05 vs. MCAO+DX) and restored the level of NAD+ (Figure 5B, p<0.05 vs. MCAO+DX) 6 hours after MCAO. The administration of ATP synthase inhibitor Olig A or NAMPT inhibitor FK866 before HBO exposure attenuated the effects of HBO (Figure 5A and 5B, p<0.05 vs. MCAO+DX+HBO). Knockdown Sirt1 by Sirt1 siRNA reversed the protective effects of HBO in hyperglycemic MCAO rats (Supplement figure V).

Figure 5.

HBO ability to restore NAD+ and Sirt1 was dependent on NAMPT and ATP. Hyperglycemia/MCAO significantly decreased activity of NAMPT at 6 hours (Figure 5A) and diminished NAD+ production at the same time point (Figure 5B). HBO or NAD+ administration restored NAD+ and activated NAMPT (Figure 5A and 5B). Co-expression of Sirt1/NAMPT in cells of the penumbra area was observed (Figure 5C). HBO increased the expression of Sirt1 and NAD+ mimicked the effects of HBO, and ATP synthase or NAMPT inhibition reduced the protective effects of HBO (Figure 5D). *p < 0.05 vs. Sham; #p < 0.05 vs. MCAO+DX.

6. Sirt1 co-localized with NAMPT after MCAO and decreased from 12 hours after MCAO. HBO increase the expression of Sirt1 dependent on ATP and NAD+

We determined the localization and time dependent expression of Sirt1 after MCAO, and studied the effects of ATP or NAD+ inhibition on the expression of Sirt1. Our results showed that Sirt1 was co-localized with NAMPT in the penumbra 24 hours after MCAO (Figure 5C). HBO and NAD+ increased the expression of Sirt1 24 hour after MCAO (Fig 5D, p< 0.05 vs. MCAO+DX), NAMPT inhibitor FK866 or ATP synthase inhibitor Olig A as well as Sirt1 siRNA decreased the expression of Sirt1 24 hours after HBO treatment (Fig 5D, p< 0.05 vs. MCAO+DX+HBO).

7. HBO activated ATP/NAD+/Sirt1 pathway and consequently inhibited apoptosis and preserved the integrity of BBB in hyperglycemic MCAO rats

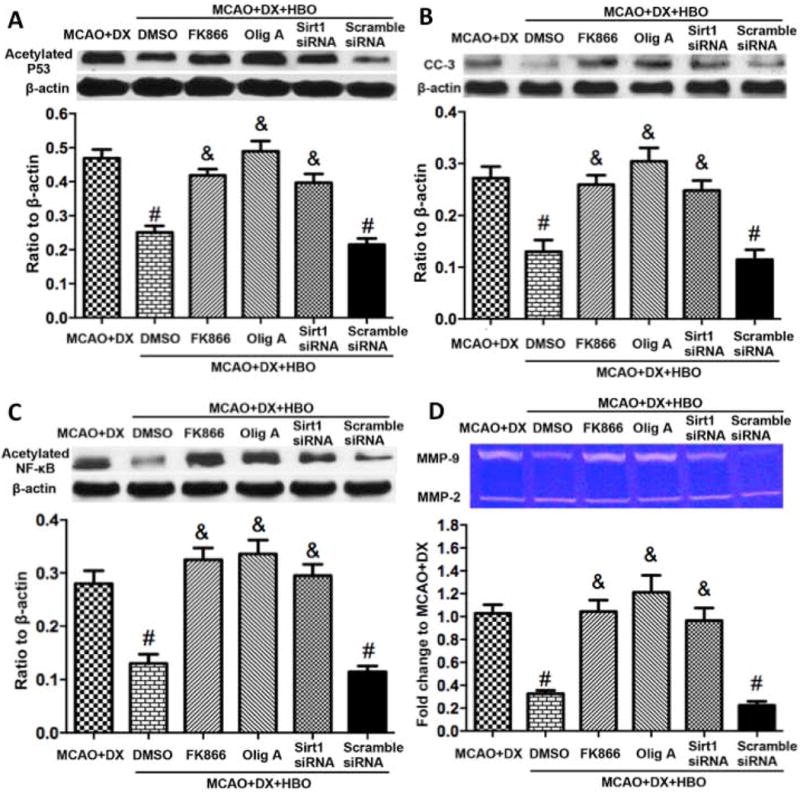

To further determine the molecular pathways underlying Sirt1 activation induced protection, we targeted p53 and NF-κB, the important downstreams of Sirt1. Compared to hyperglycemia/MCAO, HBO significantly decreased the level of acetylated p53 and acetylated NF-κB (Figure 6A and 6C, p<0.05 vs. MCAO+DX). Furthermore HBO suppressed the expression of CC3 and the activity of MMP-9 in hyperglycemic rats 24 hours after MCAO (Figure 6B and 6D, p<0.05 vs. MCAO+DX). Administration of NAMPT inhibitor FK866, ATP synthase inhibitor Olig A or Sirt1 siRNA abolished the effects of HBO (Figure 6, p< 0.05 vs. MCAO+DX+HBO).

Figure 6.

HBO induced activation of ATP/NAD+/Sirt1 pathway, decreased apoptosis and inhibited MMP-9. Protective effects of HBO were accompanied with decreased expression of p53 (Figure 6A), CC-3 (Figure 6B) and NF-κB (Figure 6C), and decreased activity of MMP-9 (Figure 6D). ATP synthase inhibitor and NAMPT inhibitor as well as Sirt1 siRNA reduced the protective effects of HBO (Figure 6A-D). #p < 0.05 vs. MCAO+DX; &p < 0.05 vs. MCAO+DX+HBO.

8. HBO showed the tendency to decrease mortality of hyperglycemic rats after MCAO

HBO showed the trends to decrease mortality of rats after MCAO+DX. However the trend did not reach statistic significance (Supplement figure VI).

Discussion

In the present study we explored the new molecular pathway underlying HBO protection in the model of MCAO induced hemorrhagic transformation. The benefits of HBO on HT, observed in our study, are in agreement with previous studies9, 10. The novelty and important finding of the study is: the protective effects of HBO are, at least partly, mediated through ATP/NAD+/Sirt1 pathway.

Early restoration of energy can interrupt the initial responses and delay or even disrupt the spiral of abnormal changes that culminate in cell death after ischemic stroke. HBO is able to increase the level of ATP and relieve the energy stress in experimental stroke27, 28, 29, but the mechanisms underlying HBO-induced protection have not been fully elucidated yet. In our study we employed the MCAO model, a well-established model of ischemic stroke. We demonstrated that hyperglycemia exaggerated the decrease of the ATP and NAD+ level, HT and neurological deficits in MCAO rats. HBO treatment reduced the infarction volume as well as hemorrhagic volume, eventually improved the neurological deficits. Additionally HBO treatment increased the level of ATP and the activity of NAMPT, promoting the production of NAD+. We further demonstrated to the first time that HBO activated ATP/NAD+/Sirt1 pathway, consequently reduced HT and apoptosis.

In clinic, hyperglycemia is more common in patients with preexisting diabetes, however it is also present in a significant proportion of non-diabetic patients30. Even in the absence of a previous history of diabetes, about 60% acute stroke patients will develop hyperglycemia, which is probably a response to the stress and severity of ischemia31. Hyperglycemia is strictly associated with HT and worse clinical outcomes after stroke32, 33. Under hyperglycemia condition, anaerobic glucose metabolism can rapidly generate ATP, and maintain ATP levels in the ischemic tissue, but this process also produce deleterious lactic acidosis and oxidative stress, which will adversely affect ischemic brain metabolism34. In the present study, we injected dextrose at the onset of reperfusion to mimic hyperglycemia in clinic, and our results are consistent with the previous report that acute hyperglycemia further deteriorate the energy status after ischemia. We found the decreased level of ATP and NAD+ in the brain, associated with great macroscopic bleeding area and big bleeding volume as well as severe neurobehavioral deficits in the hyperglycemic rats 24 hour after MCAO. Reduction of ATP is the initiator and key mediator of cell death pathways after MCAO35. Biochemical studies have consistently shown activation of NAMPT by ATP in vitro, suggesting that cellular energy charge could potentially boost NAMPT-mediated NAD+ production36, 37, 38. Although mitochondrial membrane potential is an important parameter of mitochondrial function used as an indicator of ATP synthesis, it is hard to access in an in vivo study39. We detected the level of intracellular ATP and NAD+ alternatively, which reflects the status of cellular energy and energy transformation, as critical moleculars in the pathway we studied.

NAD+ played an important role in energy balance and cell survival in ischemic stroke. After brain ischemia, NAD+ fuels Sirt1 and enables it to regulate transcription factors involved in pathways linked to apoptosis and inflammation13. HBO has been reported to increase Sirt1 protein and mRNA expression in animal models of stroke14. We found HBO treatment significantly increased the level of ATP and NAD+, ameliorated HT and improved neurological functions in hyperglycemic MCAO rats; Administration of NAD+ mimicked the effects of HBO. More important, utilizing pharmacological manipulations, this study showed for the first time that HBO positively modulated the activity of NAMPT and upregulated NAD+ levels by increasing the level of ATP, thereby controlled Sirt1 expression, leading to deacetylation of NF-κB and P53. Our results were consistent with the previous studies that inhibition of NAMPT with FK86613 or silence Sirt1 with Sirt1 siRNA20 deteriorated the outcome after stroke. We demonstrated a novel “ATP/NAD+/Sirt1” signaling pathway of HBO treatment for HT after stroke. Previous studies have demonstrated that HBO increase the oxygen delivery to ischemic tissue and is able to restore energy status of the tissue27, 40, 41. We believe therefore that both direct delivery of oxygen and the activation of ATP/NAD+/Sirt1 pathway underlay HBO induced BBB protection.

As an NAD+-dependent deacetylase, Sirt1 specifically promotes the transcription of a set of genes related to cell survival, energy metabolism, and inflammation. Sirt1 deficiency or knockdown attenuated the neuroprotection of NAD+ in ischemic stroke13, 42. Sirt1 mediated deacetylation of p53, reducing its pro-apoptotic effects; and it also deacetylated NF-κB, reducing its pro-inflammatory effects43. p53 mediates apoptosis through several pathways and results in activation of caspase-3, the executor of cell death44. NF-κB is the major transcription factor that transcribes pro-inflammatory mediators in the nervous system, including MMP-9. In ischemic stroke, MMP-9 is released from neurons and reactive astrocytes to degrade the components of BBB45–47. We showed that in hyperglycemic MCAO rats, Sirt1 was highly co-localized with NAMPT, and positively regulated by ATP and NAD+. We also observed that HBO treatment decreased the level of acetylated NF-κB and acetylated p53 in hyperglycemic MCAO rats, and knockdown Sirt1 by Sirt1 siRNA abolished the effects of HBO. Finally, we proved that the beneficial effects were abolished by Sirt1 siRNA. Taken together we demonstrated that Sirt1 is a key mediator of HBO protective effects.

We investigated whether HBO would be able to decrease injury induced by combination of hyperglycemia/stroke/reperfusion. The combination represents the bright spectrum of human stroke patients with different kind of vascular pathology. Certainly there are differences between cerebral vascular pathophysiology induced by chronic diabetes-associated hyperglycemia and acute stroke-induced increase of blood glucose. However, there are also significant matches in outcomes and underlying mechanisms between these two pathological conditions. Indeed such factors as can be an increased production of ROS, aggravation of post stroke inflammation and apoptosis which could be observed both in diabetic and acute hyperglycemic objects30, 48, 49. Similarly, there are overlaps in the pathophysiological mechanism underlying BBB injury induced by reperfusion and rtPA therapy. Both reperfusion and rtPA can increased the post-stroke inflammation and production of ROS, and consequently disintegrate BBB50–52. We in our study determined a new mechanism underlying HBO induced protection on BBB after stroke. It is however apparent that further detailed investigations of this concept need to be done. Animal models able to mimic diabetes or rtPA induced post-stroke injury more precisely should be applied for further investigation.

It is also important to note that massive cerebral infarction is one of the most prominent factors of HT. Therefore the decrease of the hemorrhagic volume, observed in this study, might be not consequence of HBO-induced MMP-9 activity reduction, but a consequence of HBO-induced reduction of infarct volume. We have previously proved that the hemorrhagic volume is independent of infarct volume in hyperglycemic MCAO rats15. In view of this fact we believe that the decrease of the hemorrhage volume after HBO treatment was mediated by the investigated pathway, but not by the reduction of infarct volume. Furthermore, the effects of ATP/NAD+/Sirt1 pathway seems to play important role in HBO induced protection against HT. As mentioned above, due to extremely limited supply of energy, neurons in the infarct core die during the first minutes after stroke. It was therefore not surprisingly that HBO has only moderate effects on the infarct volume, probably saving neurons in the peri-infarct penumbra area only. Nevertheless, effects of the HBO can be clearly seen latter. Third, HT is a multifactorial phenomenon. Except the ATP/NAD+/Sirt1 pathway, other mechanisms such as attenuation of increased vascular sensitivity and reactivity may play an important role in the beneficial actions of HBO53. HBO induced overexpression of the aquaporin 4 (AQP4), a water channel abundantly expressed in the brain54, 55. Effects of HBO on BBB integrity and brain edema might also be mediated by water or ion channels. While some publications shown that AQP4 downregulation protects BBB, reducing brain edema56; another demonstrated that AQP4 downregulation increases brain water content57. Investigations of whether HBO affects the expression of AQP4 and attenuates HT in hyperglycemic MCAO rats are needed. Significantly impairment of neurological functions is typical response on development of HT, which has been observed in different models of stroke5. We believe therefore that the beneficial effects of HBO on neurological functions can be explained, at least partly, by the activation of ATP/NAD+/Sirt1 pathway and subsequently preservation of BBB in hyperglycemic MCAO rats.

In conclusion, in this study, we demonstrated that HBO treatment improved energy metabolism and consequently decreased apoptosis and preserved BBB in hyperglycemic rats after ischemic stroke and investigated the possible involvement of ATP/NAD+/Sirt1 pathway in the HBO-induced prevention of HT. Although our results provided first indications that the pathway is involved in the HBO actions, further experiments are needed to strong current results and prove our hypothesis that HBO might be a promising approach for acute ischemic stroke patients, especially diabetic patients and patients treated with rtPA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This study was supported partially by a grant from National Institutes of Health NS081740 and NS082184 to Dr. Zhang.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Schurr A. Energy metabolism, stress hormones and neural recovery from cerebral ischemia/hypoxia. Neurochem Int. 2002;41:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(01)00142-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belanger M, Allaman I, Magistretti PJ. Brain energy metabolism: Focus on astrocyte-neuron metabolic cooperation. Cell Metab. 2011;14:724–738. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaillard A, Cornu C, Durieux A, Moulin T, Boutitie F, Lees KR, et al. Hemorrhagic transformation in acute ischemic stroke. The mast-e study. Mast-e group. Stroke. 1999;30:1326–1332. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.7.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hafez S, Hoda MN, Guo X, Johnson MH, Fagan SC, Ergul A. Comparative analysis of different methods of ischemia/reperfusion in hyperglycemic stroke outcomes: Interaction with tpa. Transl Stroke Res. 2015;6:171–180. doi: 10.1007/s12975-015-0391-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jickling GC, Liu D, Stamova B, Ander BP, Zhan X, Lu A, et al. Hemorrhagic transformation after ischemic stroke in animals and humans. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:185–199. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lapchak PA. Critical early thrombolytic and endovascular reperfusion therapy for acute ischemic stroke victims: A call for adjunct neuroprotection. Transl Stroke Res. 2015;6:345–354. doi: 10.1007/s12975-015-0419-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang X, Tsuji K, Lee SR, Ning M, Furie KL, Buchan AM, et al. Mechanisms of hemorrhagic transformation after tissue plasminogen activator reperfusion therapy for ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2004;35:2726–2730. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000143219.16695.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiong XY, Yang QW. Rethinking the roles of inflammation in the intracerebral hemorrhage. Transl Stroke Res. 2015;6:339–341. doi: 10.1007/s12975-015-0402-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun L, Zhou W, Mueller C, Sommer C, Heiland S, Bauer AT, et al. Oxygen therapy reduces secondary hemorrhage after thrombolysis in thromboembolic cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:1651–1660. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qin Z, Karabiyikoglu M, Hua Y, Silbergleit R, He Y, Keep RF, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen-induced attenuation of hemorrhagic transformation after experimental focal transient cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2007;38:1362–1367. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000259660.62865.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen X, Zhao S, Song Y, Shi Y, Leak RK, Cao G. The role of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase in cerebral ischemia. Curr Top Med Chem. 2015;15:2211–2221. doi: 10.2174/1568026615666150610142234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang P, Miao CY. Nampt as a therapeutic target against stroke. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2015;36:891–905. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2015.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang P, Xu TY, Guan YF, Tian WW, Viollet B, Rui YC, et al. Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase protects against ischemic stroke through sirt1-dependent adenosine monophosphate-activated kinase pathway. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:360–374. doi: 10.1002/ana.22236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yan W, Fang Z, Yang Q, Dong H, Lu Y, Lei C, et al. Sirt1 mediates hyperbaric oxygen preconditioning-induced ischemic tolerance in rat brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:396–406. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo ZN, Xu L, Hu Q, Matei N, Yang P, Tong LS, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen preconditioning attenuates hemorrhagic transformation through reactive oxygen species/thioredoxin-interacting protein/nod-like receptor protein 3 pathway in hyperglycemic middle cerebral artery occlusion rats. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:e403–411. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang JH, Lo T, Mychaskiw G, Colohan A. Mechanisms of hyperbaric oxygen and neuroprotection in stroke. Pathophysiology. 2005;12:63–77. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng C, Han J, Xia W, Shi S, Liu J, Ying W. NAD(+) administration decreases ischemic brain damage partially by blocking autophagy in a mouse model of brain ischemia. Neurosci Lett. 2012;512:67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang B, Ma Y, Kong X, Ding X, Gu H, Chu T, et al. NAD(+) administration decreases doxorubicin-induced liver damage of mice by enhancing antioxidation capacity and decreasing DNA damage. Chem Biol Interact. 2014;212:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Gool F, Galli M, Gueydan C, Kruys V, Prevot PP, Bedalov A, et al. Intracellular NAD levels regulate tumor necrosis factor protein synthesis in a sirtuin-dependent manner. Nat med. 2009;15:206–210. doi: 10.1038/nm.1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng Y, Hu Q, Manaenko A, Zhang Y, Peng Y, Xu L, et al. 17β-Estradiol attenuates hematoma expansion through estrogen receptor α/ silent information regulator 1/nuclear factor kappa b pathway in hyperglycemic intracerebral hemorrhage mice. Stroke. 2015;46:485–491. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanaka R, Takayama J, Takaoka M, Sugino Y, Ohkita M, Matsumura Y. Oligomycin, an F1Fo-ATPase inhibitor, protects against ischemic acute kidney injury in male but not in female rats. J pharmacol sci. 2013;123:227–234. doi: 10.1254/jphs.13069fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu Q, Ma Q, Zhan Y, He Z, Tang J, Zhou C, et al. Isoflurane enhanced hemorrhagic transformation by impairing antioxidant enzymes in hyperglycemic rats with middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke. 2011;42:1750–1756. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.603142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asahi M, Asahi K, Wang X, Lo EH. Reduction of tissue plasminogen activator-induced hemorrhage and brain injury by free radical spin trapping after embolic focal cerebral ischemia in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:452–457. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200003000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia JH, Wagner S, Liu KF, Hu XJ. Neurological deficit and extent of neuronal necrosis attributable to middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Statistical validation. Stroke. 1995;26:627–634. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.4.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drunalini Perera PN, Hu Q, Tang J, Li L, Barnhart M, Doycheva DM, et al. Delayed remote ischemic postconditioning improves long term sensory motor deficits in a neonatal hypoxic ischemic rat model. PloS one. 2014;9:e90258. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li L, Tao Y, Tang J, Chen Q, Yang Y, Feng Z, et al. A cannabinoid receptor 2 agonist prevents thrombin-induced blood-brain barrier damage via the inhibition of microglial activation and matrix metalloproteinase expression in rats. Transl Stroke Res. 2015;6:467–477. doi: 10.1007/s12975-015-0425-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calvert JW, Zhang JH. Oxygen treatment restores energy status following experimental neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2007;8:165–173. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000257113.75488.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun L, Strelow H, Mies G, Veltkamp R. Oxygen therapy improves energy metabolism in focal cerebral ischemia. Brain Res. 2011;1415:103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.07.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gunther A, Manaenko A, Franke H, Wagner A, Schneider D, Berrouschot J, et al. Hyperbaric and normobaric reoxygenation of hypoxic rat brain slices–impact on purine nucleotides and cell viability. Neurochem Int. 2004;45:1125–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kruyt ND, Biessels GJ, Devries JH, Roos YB. Hyperglycemia in acute ischemic stroke: Pathophysiology and clinical management. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:145–155. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCormick MT, Muir KW, Gray CS, Walters MR. Management of hyperglycemia in acute stroke: How, when, and for whom? Stroke. 2008;39:2177–2185. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.496646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Broderick JP, Hagen T, Brott T, Tomsick T. Hyperglycemia and hemorrhagic transformation of cerebral infarcts. Stroke. 1995;26:484–487. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.3.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Won SJ, Tang XN, Suh SW, Yenari MA, Swanson RA. Hyperglycemia promotes tissue plasminogen activator-induced hemorrhage by increasing superoxide production. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:583–590. doi: 10.1002/ana.22538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levine SR, Welch KM, Helpern JA, Chopp M, Bruce R, Selwa J, et al. Prolonged deterioration of ischemic brain energy metabolism and acidosis associated with hyperglycemia: human cerebral infarction studied by serial 31P NMR spectroscopy. Ann Neurol. 1988;23:416–418. doi: 10.1002/ana.410230423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lipton P. Ischemic cell death in brain neurons. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:1431–1568. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hara N, Yamada K, Shibata T, Osago H, Tsuchiya M. Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase/visfatin does not catalyze nicotinamide mononucleotide formation in blood plasma. PloS one. 2011;6:e22781. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang T, Zhang X, Bheda P, Revollo JR, Imai S, Wolberger C. Structure of nampt/pbef/visfatin, a mammalian nad+ biosynthetic enzyme. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:661–662. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burgos ES, Ho MC, Almo SC, Schramm VL. A phosphoenzyme mimic, overlapping catalytic sites and reaction coordinate motion for human nampt. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13748–13753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903898106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Griffiths EJ. Mitochondria – potential role in cell life and death. Cardiovasc Res. 46:24–27. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sunami K, Takeda Y, Hashimoto M, Hirakawa M. Hyperbaric oxygen reduces infarct volume in rats by increasing oxygen supply to the ischemic periphery. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:2831–2836. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200008000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Daugherty WP, Levasseur JE, Sun D, Rockswold GL, Bullock MR. Effects of hyperbaric oxygen therapy on cerebral oxygenation and mitochondrial function following moderate lateral fluid-percussion injury in rats. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:499–504. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.101.3.0499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang P, Du H, Zhou CC, Song J, Liu X, Cao X, et al. Intracellular nampt-nad+-sirt1 cascade improves post-ischaemic vascular repair by modulating notch signalling in endothelial progenitors. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;104:477–488. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meng X, Tan J, Li M, Song S, Miao Y, Zhang Q. Sirt1: Role under the condition of ischemia/hypoxia. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2017;37:17–28. doi: 10.1007/s10571-016-0355-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schuler M, Green DR. Mechanisms of p53-dependent apoptosis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29:684–688. doi: 10.1042/0300-5127:0290684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chaturvedi M, Kaczmarek L. Mmp-9 inhibition: a therapeutic strategy in ischemic stroke. Mol Neurobiol. 2014;49:563–573. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8538-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reuter B, Rodemer C, Grudzenski S, Meairs S, Bugert P, Hennerici MG, et al. Effect of simvastatin on mmps and timps in human brain endothelial cells and experimental stroke. Transl Stroke Res. 2015;6:156–159. doi: 10.1007/s12975-014-0381-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shi Y, Leak RK, Keep RF, Chen J. Translational stroke research on blood-brain barrier damage: Challenges, perspectives, and goals. Transl Stroke Res. 2016;7:89–92. doi: 10.1007/s12975-016-0447-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Drummond GR, Sobey CG. Endothelial nadph oxidases: Which nox to target in vascular disease? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2014;25:452–463. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fan X, Jiang Y, Yu Z, Yuan J, Sun X, Xiang S, et al. Combination approaches to attenuate hemorrhagic transformation after tPA thrombolytic therapy in patients with poststroke hyperglycemia/diabetes. Adv Pharmacol. 2014;71:391–410. doi: 10.1016/bs.apha.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yagi K, Kitazato KT, Uno M, Tada Y, Kinouchi T, Shimada K, et al. Edaravone, a free radical scavenger, inhibits mmp-9-related brain hemorrhage in rats treated with tissue plasminogen activator. Stroke. 2009;40:626–631. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.520262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lenglet S, Montecucco F, Denes A, Coutts G, Pinteaux E, Mach F, et al. Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator enhances microglial cell recruitment after stroke in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:802–812. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yan A, Zhang T, Yang X, Shao J, Fu N, Shen F, et al. Thromboxane a2 receptor antagonist sq29548 reduces ischemic stroke-induced microglia/macrophages activation and enrichment, and ameliorates brain injury. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35885. doi: 10.1038/srep35885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Unfirer S, Kibel A, Drenjancevic-Peric I. The effect of hyperbaric oxygen therapy on blood vessel function in diabetes mellitus. Med Hypotheses. 2008;71:776–780. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cevik NG, Orhan N, Yilmaz CU, Arican N, Ahishali B, Kucuk M, et al. The effects of hyperbaric air and hyperbaric oxygen on blood-brain barrier integrity in rats. Brain Res. 2013;1531:113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Simard JM, Kent TA, Chen M, Tarasov KV, Gerzanich V. Brain edema in focal ischemia: molecular pathophysiology and theoretical implications. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:258–268. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70055-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tang G, Liu Y, Zhang Z, Lu Y, Wang Y, Huang J, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells maintain blood-brain barrier integrity by inhibiting aquaporin-4 upregulation after cerebral ischemia. Stem Cells. 2014;32:3150–3162. doi: 10.1002/stem.1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tait MJ, Saadoun S, Bell BA, Verkman AS, Papadopoulos MC. Increased brain edema in aqp4-null mice in an experimental model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neuroscience. 2010;167:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.01.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.