Abstract

Objectives

This study assesses the effect of two types of hydroxyethyl starches (HES) on renal integrity and blood transfusion in cardiac surgery patients.

Design

Retrospective investigation.

Setting

Patients from a single tertiary medical center.

Participants

Inclusion criteria included coronary artery bypass graft and/or valve surgeries that underwent cardiopulmonary bypass with aortic cross clamping.

Interventions

Intraoperative HES volumes and blood product administration

Measurements and Main Results

1,265 patients met inclusion and exclusion criteria. 70% of these patients received HES and of those, 47% received <1000mL and 53% received ≥1000mL. There was no difference in the development of AKI between the two groups. Parsimonious propensity model for colloids showed combined CABG and valve surgeries were less likely associated with HES administration than CABG alone (OR 0.68; CI 0.46–0.97; P= 0.04). IABP use was less likely associated with HES (OR 0.57; CI 0.38–0.86; P=0.007). CKD Stages 3–5 were less likely to receive HES with OR 0.56 (CI 0.38–0.84; P=0.004), OR 0.51 (CI 0.20–1.33; P= 0.170), and OR 0.23 (CI 0.12–0.44; P<0.0001) respectively. No difference was noted in red blood cell transfusion. However, fresh frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate, and platelets transfusions were significantly higher in larger volumes of HES with OR 2.03 (CI 1.64–2.52; P<0.001), 1.60 (CI 1.30–1.97; P<0.000) and 1.62 (CI 1.21–2.15; P=0.006) respectively. No differences in operative mortality was found between colloid and non-colloid group.

Conclusions

This study showed no association in postoperative AKI and red blood cell transfusion between colloid and non-colloid group. Although complication rate was higher with HES, there was no difference in operative mortality between the two groups.

Keywords: synthetic colloid, hydroxyethyl starch, acute kidney injury, cardiopulmonary bypass, blood products

INTRODUCTION

Since their introduction in the 1960s hydroxyethyl starches (HES) continue to be used as volume expanders in conjunction with crystalloids1. Due to some studies highlighting increased AKI and overall adverse effects with HES in the critically ill population, the choice of fluids in septic patients has become important2–4. HES’ safety in perioperative setting, specifically in cardiovascular surgery, remains unclear due to few small, single outcome studies, and conflicting results5–8. Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) surgery in particular is prone to large fluid shifts necessitating aggressive fluid resuscitation. Colloids such as HES have become an efficient and affordable adjunct to crystalloids in maintaining intravascular volume and tissue perfusion.

Incidence of AKI after coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery can be as high as 54% depending on the definition and is associated with 60% mortality which inevitably leads to higher healthcare costs9–12. CPB also interferes with coagulation due to platelet dysfunction, decrease in coagulation factors, and increased fibrinolytic activity13; therefore, the colloid choice used to maintain intravascular volume must not compound the bleeding risk that pre-exists in cardiac surgery.

HES is derived from potato starch or waxy maize. To suit our evolving understanding of these products’ pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics, manufacturers have changed HES production from pentastarches with higher MMW (≥ 200kD), molar substitution, and hydroxyethylation ratios to newer generation tetrastarches with lower MMW (130kD), molar substitution, and hydroxyethylation ratios14. Higher molar substitution and hydroxyethylation ratio are believed to be linked with slow degradation15 which then may result in accumulation of HES in plasma, interstitial space, reticuloendothelial system, and epithelial cells leading to impaired coagulation, nephrotoxicity, and pruritus16,17. Clinical studies have shown significantly higher concentration of HES 200/0.5 remaining in plasma compared to HES 130/0.4 after 24 hours18.

Studies comparing HES products during cardiac surgery have yielded conflicting results. The lack of data quality has occurred due to small cohorts, predominantly single HES type (i.e. 130/0.4), and assessment of single primary end points such as either renal failure or bleeding. At least three meta-analyses on the effect of HES on surgical population have been published in the last four years5,6,19, but two concentrate only on kidney function5,19, and all include heterogeneous groups including cardiac, abdominal, orthopedic, etc. To further complicate the results, several surgical studies including cardiac surgery have been retracted after scientific misconduct20. Recently, there were a few new observational studies on hydroxyethyl starch and AKI in non-cardiac surgeries7,8. Our goal was to look specifically at cardiac surgical population due to the unique physiological changes that CPB predisposes and compare two different types of 6% HES and their effects on the development of postoperative AKI and the need for blood product transfusion in comparison to patients who did not receive HES.

METHODS

Study Design

With permission from the University of California Davis Institutional Review Board (IRB), patients who underwent cardiac surgery were identified from the institutional Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) Database, and medical records from July 01, 2007 to June 30, 2013 were located. Inclusion criteria included adult patients who underwent CPB with aortic cross clamping, CABG, valve, or combination surgery. Exclusion criteria included patients that did not undergo CPB, pediatric population, emergency surgery, and deep hypothermic circulatory arrest, and surgeries that did not involve coronary artery or valve. The patients were divided into two groups: colloid group (n=887) and non-colloid group (n=378) depending on intraoperative HES administration. Our institution’s HES specifically include Voluven (6% hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.4) and Hextend (6% hydroxyethyl starch 670/0.75).

Data Collection

Patient demographics, history, preoperative risk factors, preoperative medications, intraoperative data, baseline and postoperative kidney function, blood administration, bypass and cross-clamp time, all complications, and operative mortality were obtained from the STS Database (Table 1). Patient anesthesia records were reviewed through electronic medical records (EMR) and paper charts for intraoperative HES documentation.

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

| Variables | Total, N (%) | No Colloids Use | Colloids Used, N (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| N=1,265 (100.0%) | N=378 (29.9%) | N=887 (70.1%) | |||

| Age, years. Mean (SD) | 61.7 (13.4)* | 62.3 (12.3)* | 0.404 | ||

|

| |||||

| Gender | Female | 376 (29.7) | 127 (33.6) | 249 (28.1) | 0.049 |

| Male | 889 (70.3) | 251 (66.4) | 638 (71.9) | ||

|

| |||||

| Race | White | 830 (65.6) | 223 (59) | 607 (68.4) | 0.001 |

| Other | 435 (34.4) | 155 (41) | 280 (31.6) | ||

|

| |||||

| Operation status | Elective | 587 (46.4) | 168 (44.4) | 419 (47.2) | 0.571 |

| Urgent | 678 (53.6) | 210 (55.6) | 468 (52.8) | ||

|

| |||||

| Surgery type | CABG only | 591 (46.7) | 161 (42.6) | 430 (48.5) | 0.138 |

| CABG + Other | 68 (5.4) | 17 (4.5) | 51 (5.7) | ||

| CABG + Valve | 175 (13.8) | 63 (16.7) | 112 (12.6) | ||

| CABG + Valve + Other | 69 (5.5) | 21 (5.6) | 48 (5.4) | ||

| Valve | 220 (17.4) | 65 (17.2) | 155 (17.5) | ||

| Valve + Other | 142 (11.2) | 51 (13.5) | 91 (10.3) | ||

|

| |||||

| CKD stage | 1: <90 | 315 (24.9) | 80 (21.2) | 235 (26.5) | <.0001 |

| 2: 60–89 | 642 (50.8) | 176 (46.6) | 466 (52.5) | ||

| 3: 30–59 | 236 (18.7) | 83 (22) | 153 (17.2) | ||

| 4: 15–29 | 20 (1.6) | 8 (2.1) | 12 (1.4) | ||

| 5: < 15 or Dialysis | 52 (4.1) | 31 (8.2) | 21 (2.4) | ||

|

| |||||

| BMI | <18.5 | 11 (0.9) | 7 (1.9) | 4 (0.5) | 0.048 |

| 18.5–39.9 | 1165 (92.1) | 344 (91) | 821 (92.6) | ||

| >=40 | 89 (7) | 27 (7.1) | 62 (7.0) | ||

|

| |||||

| Diabetes | No | 797 (63) | 241 (63.8) | 556 (62.7) | 0.717 |

| Yes | 468 (37) | 137 (36.2) | 331 (37.3) | ||

|

| |||||

| Hypertension | No | 318 (25.1) | 101 (26.7) | 217 (24.5) | 0.397 |

| Yes | 947 (74.9) | 277 (73.3) | 670 (75.5) | ||

|

| |||||

| Hypercholesteroemia | No | 310 (24.5) | 109 (28.8) | 201 (22.7) | 0.019 |

| Yes | 955 (75.5) | 269 (71.2) | 686 (77.3) | ||

|

| |||||

| Smoking | No | 687 (54.3) | 195 (51.6) | 492 (55.5) | 0.205 |

| Yes | 578 (45.7) | 183 (48.4) | 395 (44.5) | ||

|

| |||||

| CVA | No | 1154 (91.2) | 345 (91.3) | 809 (91.2) | 0.971 |

| Yes | 111 (8.8) | 33 (8.7) | 78 (8.8) | ||

|

| |||||

| Cardiogenic shock | No | 1253 (99.1) | 375 (99.2) | 878 (99) | 0.711 |

| Yes | 12 (0.9) | 3 (0.8) | 9 (1.0) | ||

|

| |||||

| Previous MI | No | 818 (64.7) | 246 (65.1) | 572 (64.5) | 0.840 |

| Yes | 447 (35.3) | 132 (34.9) | 315 (35.5) | ||

|

| |||||

| CHF | No | 755 (59.7) | 201 (53.2) | 554 (62.5) | 0.002 |

| Yes | 510 (40.3) | 177 (46.8) | 333 (37.5) | ||

|

| |||||

| IABP | No | 1146 (90.6) | 330 (87.3) | 816 (92.0) | 0.009 |

| Yes | 119 (9.4) | 48 (12.7) | 71 (8.0) | ||

|

| |||||

| Cerebrovascular disease | No | 1047 (82.8) | 311 (82.3) | 736 (83.0) | 0.762 |

| Yes | 218 (17.2) | 67 (17.7) | 151 (17.0) | ||

|

| |||||

| Previous CV intervention | No | 971 (76.8) | 282 (74.6) | 689 (77.7) | 0.236 |

| Yes | 294 (23.2) | 96 (25.4) | 198 (22.3) | ||

|

| |||||

| Previous CABG | No | 1217 (96.2) | 362 (95.8) | 855 (96.4) | 0.594 |

| Yes | 48 (3.8) | 16 (4.2) | 32 (3.6) | ||

|

| |||||

| Previous Valve Surgery | No | 1209 (95.6) | 358 (94.7) | 851 (95.9) | 0.329 |

| Yes | 56 (4.4) | 20 (5.3) | 36 (4.1) | ||

|

| |||||

| Other Cardiac Intervention | No | 1234 (97.5) | 366 (96.8) | 868 (97.9) | 0.277 |

| Yes | 31 (2.5) | 12 (3.2) | 19 (2.1) | ||

|

| |||||

| Dialysis | No | 1218 (96.3) | 349 (92.3) | 869 (98) | <.0001 |

| Yes | 47 (3.7) | 29 (7.7) | 18 (2) | ||

|

| |||||

| Left Main Coronary Artery Disease | No | 990 (78.3) | 302 (79.9) | 688 (77.6) | 0.358 |

| Yes | 275 (21.7) | 76 (20.1) | 199 (22.4) | ||

|

| |||||

| Preoperative β Blocker | No | 432 (34.2) | 118 (31.2) | 314 (35.4) | 0.151 |

| Yes | 833 (65.8) | 260 (68.8) | 573 (64.6) | ||

|

| |||||

| Preoperative ACEi/ARBi | No | 668 (52.8) | 187 (49.5) | 481 (54.2) | 0.121 |

| Yes | 597 (47.2) | 191 (50.5) | 406 (45.8) | ||

|

| |||||

| Preoperative Nitrates | No | 1218 (96.3) | 363 (96) | 855 (96.4) | 0.756 |

| Yes | 47 (3.7) | 15 (4) | 32 (3.6) | ||

|

| |||||

| Preoperative Anticoagulants | No | 1000 (79.1) | 301 (79.6) | 699 (78.8) | 0.742 |

| Yes | 265 (20.9) | 77 (20.4) | 188 (21.2) | ||

|

| |||||

| Preoperative Coumadin Use | No | 1165 (92.1) | 343 (90.7) | 822 (92.7) | 0.244 |

| Yes | 100 (7.9) | 35 (9.3) | 65 (7.3) | ||

|

| |||||

| Preoperative Steroids | No | 1226 (96.9) | 364 (96.3) | 862 (97.2) | 0.404 |

| Yes | 39 (3.1) | 14 (3.7) | 25 (2.8) | ||

|

| |||||

| Preoperative Aspirin | No | 350 (27.7) | 111 (29.4) | 239 (26.9) | 0.378 |

| Yes | 915 (72.3) | 267 (70.6) | 648 (73.1) | ||

|

| |||||

| Preoperative lipid lowering Medications | No | 321 (25.4) | 111 (29.4) | 210 (23.7) | 0.033 |

| Yes | 944 (74.6) | 267 (70.6) | 677 (76.3) | ||

|

| |||||

| Preoperative GPIIbIIIa Inhibitor | No | 1221 (96.5) | 368 (97.4) | 853 (96.2) | 0.291 |

| Yes | 44 (3.5) | 10 (2.6) | 34 (3.8) | ||

|

| |||||

| Last creatinine level(mg/dl) | 1.53 (1.66)* | 1.14 (0.80)* | <0.0001 | ||

|

| |||||

| EF (%) | 50.8 (13.8)* | 52.6 (13.1)* | 0.029 | ||

|

| |||||

| Cross Clamp Time | 133.2 (57.2) | 126.7 (55.7) | 0.059 | ||

|

| |||||

| Perfusion Time | 189.5 (76.9) | 178.7 (69.3) | 0.019 | ||

|

| |||||

| Propensity Score | 0.666 (0.117)* | 0.714 (0.091)* | <0.0001 | ||

Note: CKD: chronic kidney diseases; BMI: body mass index; CVA: cerebral vascular accident; MI: myocardial infarction; CHF: congestive heart failure; IABP: intra-aortic balloon pump; CV: cardiovascular; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; EF: ejection fraction.

statistical significant. SD: standard deviation.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Postoperative AKI and blood product transfusions were the primary outcomes of this study. Secondary outcomes included postoperative complications and operative mortality. Baseline kidney function was based on preoperative estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR mL/min/1.73m2) that was calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation21. Patients were divided into 5 stages: Stage 1, normal eGFR (>90); Stage 2, mildly decreased eGFR (60–89); Stage 3, moderately decreased eGFR (30–59); Stage 4, severely decreased eGFR (15–29); Stage 5, kidney failure or dialysis (eGFR <15). STS definition of postoperative renal failure was used to determine postoperative AKI. This definition included the highest Cr level recorded in the post-operative course that is ≥3-fold baseline Cr or Cr ≥4 with an acute increase of ≥0.5mg/dL or new requirement for dialysis.

Blood product transfusion was based on intraoperative and postoperative administration of packed red blood cells (PRBCs), fresh frozen plasma (FFP), cryoprecipitate (cryo) and platelets.

Operative mortality was defined in the STS as death during hospital admission or within 30 days of discharge. All complications is a STS umbrella term which includes any complications that occurred postoperatively such as pulmonary, infectious, renal, cardiac, vascular, or re-operation.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were reported as mean ± SD or percentages, and compared with the t tests or chi-square test (two tailed), respectively. Univariate and multivariate logistic regressions were performed to assess associations of demographic, therapeutic and clinical outcome variables. To mitigate selection bias in HES administration, we computed the propensity score, the conditional probability of each patient receiving HES with a multivariable logistic regression model that includes patient risk factors (Table 1).

To achieve model parsimony and stability, the backward selection procedure was applied with the dropout criterion P > 0.05. The candidate risk factors were selected according to clinical plausibility, and variables collected in the database. The candidate independent variables included demographic and clinical risk factors (Table 1). The parsimonious multivariable propensity for HES use included status of procedure, type of surgery, and level of pre-existing chronic kidney disease (CKD) (Figure 1). The risk-adjusted odds ratios (OR) for all outcomes were calculated with use of a stepwise logistic-regression model with patient risk factors as independent control variables and HES use as the independent variable of interest. A propensity-weighted logistic regression model was used for operative mortality in which an inverse (estimated) propensity score as weights for patients given HES and the inverse of 1 minus the propensity score for patients not given HES and added HES as an independent factor to the model. All models fit analysis was evaluated with the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit statistic. The C statistic measures predictive power. Based on the propensity of HES use and general lineadel, we compared propensity weighted and risk adjusted operative mortality between the cohort of HES and no HES. Results are reported as percentages and odds ratios (OR) and with 95% confidence intervals (CI). All reported p values were 2-sided and p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed with SAS version 9.3 for Windows (SAS Inc., Cary, NC).

Figure 1.

The parsimonious propensity model for colloids. IABP: intra-aortic balloon pump; CKD: chronic kidney disease; CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio. The following risk factors were entered in the model development as candidate variables for predicting colloids use: age, gender, race, category of surgeries, emergency status, CKD stages, BMI, hypercholesterolemia, smoking, cerebral vascular accident (CVA), cerebrovascular diseases, cardiogenic shock, circulatory arrest, previous CV interventions, previous CABG, previous valve surgeries, other cardiac interventions, dialysis, last creatinine level, previous myocardial infarction (MI), congestive heart failure (CHF), intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP), ejection fraction (EF), left main coronary artery disease, preoperative lipid lowering medications, cross clamp time and perfusion time. The parsimony was achieved by backward selection at alpha=0.05 except the first 6 variables which were forced into the final parsimonous model.

RESULTS

Baseline and Intraoperative Parameters

Of the total 1,762 patient records, 1,268 patients met inclusion criteria, and three anesthesia records could not be located which brought final cohort number to 1,265. A total 70% patients received HES and of those, 47% received <1000mL HES while 53% received ≥1000mL HES. We further divided the HES group into Voluven and Hextend subgroups to differentiate outcomes between the two colloids. Demographics and patient characteristics show gender, race, hypercholesterolemia, lipid lowering agents, ejection fraction, intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP), and bypass time significantly correlating to HES use (Table 1). Also, patients in CKD Stage 3 or higher were less likely to receive HES. Cr was more likely to be lower in the colloid group. Propensity scores for the two groups were used in calculation of adjusted odd ratios when analyzing postoperative outcomes. Zero mL HES use was considered reference point when calculating OR. The parsimonious propensity model for colloids (Figure 1) showed that combined CABG and valve surgeries were less likely associated with HES administration than CABG alone (OR 0.68, P= 0.04). Also, patients with IABP were less likely to be given HES (OR 0.57; P=0.007). Additionally, CKD Stages 3 through 5 were less likely to receive HES with OR 0.56 (P=0.004), OR 0.51 (P= 0.170), and OR 0.23 (P<0.0001) respectively.

Effects of HES on postoperative AKI

Overall incidence of AKI was less in colloid group with 6.5% vs. 10.3% in non-colloid group (P=0.021) as shown in Table 2. The propensity weighted adjusted OR showed no difference in AKI development between the colloid and non-colloid group (Figure 2). This correlation persisted in the Hextend and Voluven groups as well. We also analyzed the data to determine whether colloids were associated with worsening of pre-existing CKD. Results showed no difference in the development of AKI in various CKD stages (Table 3). The parsimonious model for predicting AKI shows that age, combined CABG and valve surgeries, longer bypass times, urgency, pre-existing CKD, diabetes, history of CVA, history of prior cardiac intervention, and hypercholesterolemia were all associated with AKI. Other surgeries combined with CABG whether valve or unspecified, proved to be the biggest risk factor for predicting AKI.

Table 2.

Observed Outcomes of Colloids vs. No Colloids

| N (%) | AKI | Complications Any | Operative Death | MACE | Total RBC ≥1 | Total FFP ≥6 | Total CRYO ≥2 | Total Platelets ≥2 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | p-value | N (%) | p-value | N (%) | p-value | N (%) | p-value | N (%) | p-value | N (%) | p-value | N (%) | p-value | N (%) | p-value | |||

| Intraop Colloids | No | 378 (29.9) | 39 (10.3) | 0.021* | 173 (45.8) | 0.795 | 8 (2.1) | 0.473 | 102 (26.98) | 0.989 | 70 (18.52) | 0.765 | 100 (26.46) | 0.536 | 109 (28.84) | 0.415 | 40 (10.58) | 0.911 |

| Yes | 887 (70.1) | 58 (6.5) | 413 (46.6) | 25 (2.8) | 239 (26.94) | 158 (17.81) | 220 (24.80) | 236 (26.61) | 92 (10.37) | |||||||||

| Intraop Colloids | 0) No HES | 378 (29.9) | 39 (10.3) | 0.062 | 173 (45.8) | 0.924 | 8 (2.1) | 0.665 | 102 (26.98) | 0.553 | 70 (18.52) | 0.212 | 100 (26.46) | 0.197 | 109 (28.84) | 0.010* | 40 (10.58) | 0.410 |

| 1) < 1000 | 415 (32.8) | 29 (6.99) | 191 (46.02) | 13 (3.13) | 119 (28.67) | 64 (15.42) | 92 (22.17) | 91 (21.93) | 37 (8.92) | |||||||||

| 2) ≥1000 | 472 (37.3) | 29 (6.14) | 222 (47.03) | 12 (2.54) | 120 (25.42) | 94 (19.92) | 128 (27.12) | 145 (30.72) | 55 (11.65) | |||||||||

| Voluven | 0) No Voluven | 378 (42.3) | 39 (10.3) | 0.070 | 173 (45.8) | 0.445 | 8 (2.1) | 0.916 | 102 (26.98) | 0.845 | 70 (18.52) | 0.095 | 100 (26.46) | <.0001* | 109 (28.84) | 0.003* | 40 (10.58) | 0.028* |

| 1) < 1000 | 208 (23.3) | 16 (7.69) | 84 (40.38) | 5 (2.40) | 58 (27.88) | 26 (12.50) | 21 (10.10) | 44 (21.15) | 11 (5.29) | |||||||||

| 2) ≥1000 | 308 (34.5) | 17 (5.52) | 133 (43.18) | 8 (2.60) | 79 (25.65) | 60 (19.48) | 59 (19.16) | 108 (35.06) | 38 (12.34) | |||||||||

| Hextend | 0) No Hextend | 378 (50.47) | 39 (10.32) | 0.202 | 173 (45.8) | 0.137 | 8 (2.1) | 0.446 | 102 (26.98) | 0.623 | 70 (18.52) | 0.806 | 100 (26.46) | 0.001* | 109 (28.84) | 0.153 | 40 (10.58) | 0.726 |

| 1) < 1000 | 207 (27.64) | 13 (6.28) | 107 (51.69) | 8 (3.86) | 61 (29.47) | 38 (18.36) | 71 (34.30) | 47 (22.71) | 26 (12.56) | |||||||||

| 2) ≥1000 | 164 (21.90) | 12 (7.32) | 89 (54.27) | 4 (2.44) | 41 (25.00) | 34 (20.73) | 69 (42.07) | 37 (22.56) | 17 (10.37) | |||||||||

Note: AKI: acute kidney injury; MACE: major adverse cardiocerebral events; RBC: red blood cell; FFP: fresh frozen plasma; CRYO: cryoprecipitate; HES: hydroxyethyl starches;

p value: <0.05 considered statistical significant.

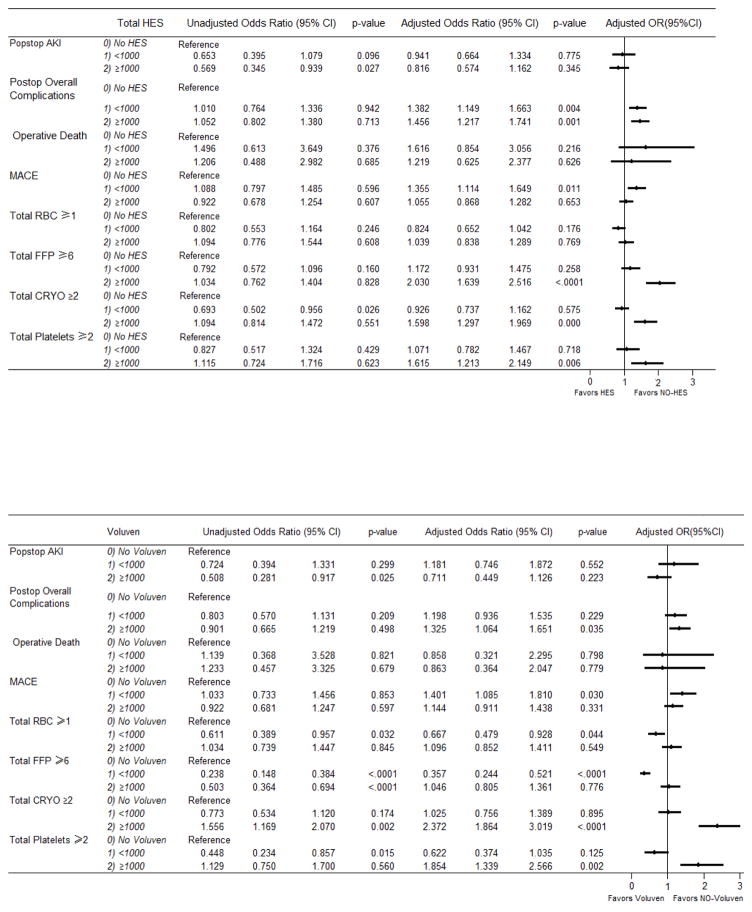

Figure 2.

Part A Unadjusted vs. propensity weighted and risk adjusted odds ratios of total colloids use on postoperative outcomes. Part B. Unadjusted vs. propensity weighted and risk adjusted odds ratios of Voluven use on postoperative outcomes. Part C. Unadjusted vs. propensity weighted and risk adjusted odds ratios of Hextend Use on postoperative outcomes. The following risk factors were entered in the model development as candidate variables for predicting postop outcomes with inverse propensity weighting of intraoperative colloids use: Total hydroxyethyl starch (HES)/Voluvan/Hextend, age, gender, race, category of surgeries, emergency status, CKD stage, crystalloids, BMI, smoking, CVA, cerebrovascular disease, cardiogenic shock, circulatory arrest, previous CV intervention, previous CABG, previous valve surgeries, other cardiac intervention, dialysis, last creatinine level, previous MI, CHF, IABP, EF, left main coronary artery disease. The parsimony was achieved by a backward selection at alpha=0.05 except first 8 variables which were forced in the final parsimonous model. AKI; acute kidney injury; MACE: major adverse cardio-cerebral events; RBC: red blood cell; FFP: fresh frozen plasma; CRYO: cryoprecipitate.

Table 3.

Colloids Effects on AKI for CKD Stage 1–4

| N (%) | Observed AKI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CKD Stage 1–4 Combined: | N (%) | p-value | ||

| Intraoperative Colloids | No | 346 (28.6) | 25 (7.5) | 0.481 |

| Yes | 865 (71.4) | 53 (6.1) | ||

| Intraoperative Colloids | 0) No HES | 346 (28.6) | 26 (7.5) | 0.656 |

| 1) <1000 | 406 (33.5) | 27 (7.0) | ||

| 2) ≥1000 | 459 (37.5) | 26 (6.7) | ||

| Voluven | No Voluven | 346 (40.7) | 25 (7.2) | 0.477 |

| 1) <1000 | 204 (24.0) | 14 (6.9) | ||

| 2) ≥1000 | 301 (35.4) | 15 (5.0) | ||

| Hextend | No Hextend | 346 (49.0) | 25 (7.2) | 0.940 |

| 1) <1000 | 202 (28.6) | 13 (6.4) | ||

| 2) ≥1000 | 158 (22.4) | 11 (7.0)) | ||

| CKD Stage 1: >90 | ||||

| Intraoperative Colloids | No | 62 (25.2) | 2 (3.3) | 0.642 |

| Yes | 184 (74.8) | 4 (2.2) | ||

| Intraoperative Colloids | 0) No HES | 62 (25.2) | 2 (3.3) | 0.716 |

| 1) <1000 | 78 (31.7) | 1 (1.3) | ||

| 2) ≥1000 | 106 (43.1) | 3 (2.8) | ||

| Voluven | No Voluven | 62 (34.6) | 2 (3.2) | 0.922 |

| 1) <1000 | 40 (22.4) | 1 (2.5) | ||

| 2) ≥1000 | 77 (43.0) | 3 (3.9) | ||

| Hextend | No Hextend | 62 (48.1) | 2 (3.2) | 0.334 |

| 1) <1000 | 38 (29.5) | 0 | ||

| 2) ≥1000 | 29 (22.5) | 0 | ||

| CKD Stage 2: 60–89 | ||||

| Intraoperative Colloids | No | 165 (26.2) | 9 (5.5) | 0.197 |

| Yes | 466 (73.8) | 15 (3.2) | ||

| Intraoperative Colloids | 0) No HES | 165 (26.2) | 9 (5.5) | 0.269 |

| 1) <1000 | 218 (34.6) | 5 (2.3) | ||

| 2) ≥1000 | 248 (39.3) | 10 (4.0) | ||

| Voluven | No Voluven | 165 (37.8) | 9 (5.5) | 0.186 |

| 1) <1000 | 111 (25.4) | 2 (1.8) | ||

| 2) ≥1000 | 161 (36.8) | 4 (2.5) | ||

| Hextend | No Hextend | 165 (45.9) | 9 (5.5) | 0.404 |

| 1) <1000 | 107 (29.8) | 3 (2.8) | ||

| 2) ≥1000 | 87 (24.2) | 6 (6.9) | ||

| CKD Stage 3: 30–59 | ||||

| Intraoperative Colloids | No | 106 (34.7) | 11 (10.4) | 0.209 |

| Yes | 199 (65.3) | 31 (15.6) | ||

| Intraoperative Colloids | 0) No HES | 106 (34.7) | 11 (10.4) | 0.259 |

| 1) <1000 | 99 (32.5) | 18 (18.2) | ||

| 2) ≥1000 | 100 (32.8) | 13 (13.0) | ||

| Voluven | No Voluven | 106 (50.0) | 11 (10.4) | 0.485 |

| 1) <1000 | 46 (21.7) | 8 (17.4) | ||

| 2) ≥1000 | 60 (28.3) | 8 (13.3) | ||

| Hextend | No Hextend | 106 (53.3) | 11 (10.4) | 0.324 |

| 1) <1000 | 53 (26.6) | 10 (18.9) | ||

| 2) ≥1000 | 40 (20.1) | 5 (12.5) | ||

| CKD Stage 4: 15–29 | ||||

| Intraoperative Colloids | No | 13 (44.8) | 3 (23.1) | 0.775 |

| Yes | 16 (55.2) | 3 (18.7) | ||

| Intraoperative Colloids | 0) No HES | 13 (44.8) | 3 (23.1) | 0.440 |

| 1) <1000 | 11 (37.9) | 3 (27.3) | ||

| 2) ≥1000 | 5 (17.2) | 0 | ||

| Voluven | No Voluven | 13 (56.5) | 3 (23.1) | 0.343 |

| 1) <1000 | 7 (30.4) | 3 (42.9) | ||

| 2) ≥1000 | 3 (13.0) | 0 | ||

| Hextend | No Hextend | 13 (68.4) | 3 (23.1) | 0.44 |

| 1) <1000 | 4 (21.1) | 0 | ||

| 2) ≥1000 | 2 (10.5) | 0 | ||

Note: CKD: chronic kidney diseases; HES: hydroxyethyl starches; p value: <0.05 considered statistically significant. Total patients in this table do not add up to the total of 1265 included in the study due to CKD 5 patients being omitted.

Effects of HES on blood product transfusion

Overall no significant difference was noted in the use of PRBC between the colloid and non-colloid groups (Figure 2). However, the transfusion of FFP (OR 2.03, P<0.0001), cryo (OR 1.60, P=0.000), and platelets (OR 1.62, P=0.006) were significantly higher in the ≥1000mL colloid group. Colloid group <1000mL did not show this difference.

Effects of HES on secondary outcomes

No statistical differences exist in the overall incidence of operative death between the 2 groups whether high or low volume (Figure 2). The parsimonious model for predicting operative mortality showed age, female gender, combined CABG and valve surgeries, urgency, diabetes, CKD Stage 5, BMI ≥40, cardiogenic shock, IABP, bypass time, and prior valve surgery to be associated with increased mortality. Combined CKD 5, BMI ≥40, cardiogenic shock, IABP, and previous valve surgery posed to be the highest mortality predictors.

The observed incidence of postoperative complications was 46.6% in colloid vs 45.8% in the non-colloid group (P=0.795) as shown in Table 2. Figure 2 shows that overall postoperative complications were higher with OR of 1.38 in the <1000mL HES group (P=0.004) and 1.46 in the ≥1000mL HES group (P< 0.001). This significantly higher OR also extended to the high volume Voluven (OR 1.33, P= 0.035) as well as high and low volume Hextend groups with OR 1.59 (P=0.002) and 1.63 (P=0.002) respectively. The parsimonious model for predicting postoperative complications showed that age, combined CABG and valve surgeries, urgency, pre-existing CKD, BMI ≥40, cardiogenic shock, CHF, IABP, both low and high volume HES were all associated with occurrence of postoperative complications. Cardiogenic shock by far was the biggest factor predicting postoperative complications.

Major adverse cardiocerebral events (MACE) often allow studies to target cardiac specific complications. Since no specific definition of MACE exists, we defined MACE as death, myocardial infarction, repeat revascularization, and postoperative stroke. Our results showed significantly increased adjusted OR of 1.36 (P=0.011) in the lower volume colloid group (Figure 2). This result also extended to the lower volume Voluven group with OR of 1.40 (P=0.030). Results were not significant in the Hextend group. Parsimonious model for predicting MACE showed that other than low volume HES, combined CABG + valve cases, urgency, CKD 5, BMI ≥40, and CHF to be positively associated with MACE. Type of case and end stage CKD were the biggest culprits.

DISCUSSION

This is the largest retrospective study to look at both AKI and intraoperative blood product administration in cardiac surgical patients receiving HES. The principal finding of this study illustrated no difference in AKI in patients who received colloid vs. those who did not. Patients in HES group also did not receive more red blood cell product administration compared to those in non-HES group.

Acute Kidney Injury after HES Use

AKI is associated with many complications after CPB such as infections, increased mortality, and length of stay22. Longer CPB time is also associated with increased risk of AKI23; therefore, it is important to avoid factors that may worsen AKI after CPB. Two observational studies showed a dose dependent decrease in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in patients receiving HES 450/0.7 and increased AKI in patients receiving HES 200/0.5 respectively24,25. The former studied a different HES and defined AKI as GFR assessment three to five days postoperatively which differs from the STS criteria we utilized which records peak Cr throughout the postoperative course. The latter study utilized a 10% solution that is now rarely available in the United States and Europe26 and also used different AKI criteria. Our AKI results were similar to the meta-analysis study assessing smaller randomized controlled trials (10 out of 19 included studies were cardiac surgery) which did not show a difference in AKI in surgical patients who received HES1. Our study was unique in that we attempted to determine whether pre-existing kidney disease worsened as a result of colloid administration and found results to not be significantly different between various CKD stages. Our data overall support no correlation between these synthetic colloids and development of AKI in cardiac surgery.

Blood product administration after HES use

Colloid group patients did not receive more red blood cells intraoperatively or postoperatively when compared to the non-colloid group; instead, they received less PRBC than the non-colloid group. Previous review article containing smaller studies that covered 20 trials totaling 2,151 patients consisting mainly of cardiac, major abdominal, and orthopedic surgeries did not find increased allogenic erythrocyte transfusion in patients who received HES2. All included studies involved tetrastarches. Studies in cardiac surgery have shown decreased clot formation rate and strength in patients who received primarily large molecular weight and molar substitution HES, but the same studies did not look at blood product transfusion27–29. In studies that looked at blood product administration, results have been conflicting. There have been reports of decreased blood loss and transfusion of PRBC in patients treated with rapidly degradable HES30,31. Increased blood loss and transfusions however, have also been reported in studies that used purely higher molecular weight and molar substitution HES32,33. When we divided our data between the higher molecular weight Hextend and the lower molecular weight Voluven, increased PRBC transfusion was not demonstrated with either product.

Our study showed increased transfusion of FFP, cryoprecipitate, and platelets particularly in the high volume HES group. Slowly degradable HES solutions with high molar substitution such as Hextend have been known to cause impaired coagulation via decreasing Factor VIII and vWF concentration. These effects have not been shown in the rapidly degradable HES with low molar substitution and molecular weight such as Voluven26,34,35. This slowly degradable HES’ effect on coagulation could partially contribute to higher blood loss and increased blood product transfusion. While our study did show an overall increase in these blood products in the higher volume HES group, we were unable to show significantly consistent high transfusion rates once we divided the colloid groups between Hextend and Voluven. Overall, using caution with higher HES volumes may seem reasonable in presence of impaired coagulation.

Secondary outcomes: mortality, all cause complications, and MACE

There was no difference in the operative mortality in patients who received HES; however, these results are not consistently reproduced in the subgroups of patients divided by Hextend and Voluven. The OR for operative mortality was significantly high in the subgroup of patients who received Hextend <1000mL. The wide confidence interval may be due to outliers.

The increased OR of postoperative complications was significantly higher in both high and low volume colloid groups. Dividing the colloid groups to Voluven and Hextend produced similar significant results. In order to better define complications, MACE was used as a subcategory to enhance relevancy to the cardiac population. Interestingly MACE adjusted OR’s were higher in the low volume colloid group and the low volume Voluven group. MACE adjusted OR’s were not significantly elevated in the high volume colloid group. A possible explanation for this finding may be that the low volume colloid group received higher amounts of crystalloid administration, which has its own adverse effects such as those related to edema formation36.

Limitations

There were several limitations to our study including inability to randomize and blind that naturally co-exist with retrospective studies. This was also a single center study focused on a very specific patient population in order to lessen the burden of confounding variables that perturb retrospective studies. Although the take home message is that HES is safe, but the clinicians may have selected the patients without CKD when giving HES. However, we have performed propensity weighing to take into consideration variables such as age, gender, race, operation status, surgery type, cross-clamp time, bypass time, CKD stage, presence of other comorbidities, and medications and calculated adjusted ORs. We did not consider baseline anemia which is known risk factor for cardiac surgery-associated AKI37. We were also unable to control for the crystalloid and albumin administration. It may be possible that patients receiving lower HES received larger amounts of crystalloids that resulted in different outcomes. In retrospect, it is also important to consider the solution used to deliver the two types of HES that were used in this study. While Hextend is suspended in a balanced salt solution, Voluven is suspended in saline. The difference of chloride in these two products that may have contributed to AKI was not considered. Also other confounding variables may have formed after dividing the patient population by colloid types. For example, Hextend was mainly used from 2007–2009 at our institution, and a transition to Voluven occurred from 2009–2013.

Our AKI criteria also differed from Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) criteria as well as RIFLE (risk, injury, failure, loss of function, ESRD), two popular criteria used to measure AKI38,39. STS definition is a more stringent definition adapted and modified from the Failure Stage of the RIFLE criteria. The length of Cr monitoring also differs as AKIN uses a 48-hour window to measure Cr, RIFLE uses a 7-day window39, while STS criteria utilize the entire postoperative period. Various heterogeneous criteria make it difficult to compare AKI results between studies. We also did not look at long term CKD development or long term mortality.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, our study found no differences in the development of post-operative AKI as well as administration of PRBC products between the colloid and non-colloid groups. Due to increase in other blood product administration and increase in postoperative complications noted with the colloid group, randomized prospective studies would be need to performed in this population to draw more definite conclusions about HES safety and long term effects.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sarah Truong, BS and Andrea Rosato, RN, BSN, for their contributions to data collection.

Founding: This work was supported by University of California Davis Health System Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, and NIH grant UL1 TR000002.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

DISCLOSURES

None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Murray GF, Solanke T, Thompson WL, Ballinger WF. Hydroxyethyl starch as a plasma expander in hemorrhagic shock. Surg Forum. 1965;16:34–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perner A, Haase N, Guttormsen AB, et al. Hydroxyethyl starch 130/0. 42 versus Ringer’s Acetate in Severe Sepsis. New Eng J Med. 2012;367:124–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Myburgh JA, Finfer S, Bellomo R, et al. Hydroxyethyl starch or saline for fluid resuscitation in intensive care. New Eng J Med. 2012;367:1901–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zarychanski R, Abou-Setta AM, Turgeon AF, et al. Association of hydroxyethyl starch administration with mortality and acute kidney injury in critically ill patients requiring volume resuscitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2013 Feb 20;309(7):678–88. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gillies MA, Habicher M, Jhanji S, et al. Incidence of posteroperative death and acute kidney injury associated with i.v. 6% hydroxyethyl starch use: systemic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2014;112:25–34. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Der Linden P, James M, Mythen M, Weiskopf RB. Safety of modern starches used during surgery. Anesth & Analg. 2013;116:35–48. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31827175da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hand WR, Whiteley JR, Epperson TI, et al. Hydroxyethyl starch and acute kidney injury in orthotopic liver transplantation: a single-center retrospective review. Anesth Analg. 2015;120:619–26. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahn HJ, Kim JA, Lee AR, Yang M, Jung HJ, Heo B. The risk of acute kidney injury from fluid restriction and hydroxyethyl starch in thoracic surgery. Anesth Analg. 2016;122:186–93. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kertai MD, Zhou S, Karhausen JA, et al. Platelet counts, acute kidney injury, and mortality after coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. Anesthesiology. 2016;124:339–52. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Inter. 2012;2(Suppl):1–138. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borthwick E, Ferguson A. Perioperative acute kidney injury: risk factors, recognition, management, and outcomes. BMJ. 2010;341:c3365. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stafford-Smith M, Shaw A, Swaminathan M. Cardiac surgery and acute kidney injury; emerging concepts. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2009;15:498–502. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e328332f753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuitunen AH, Heikkila LJ, Salmenpera MT. Cardiopulmonary bypass with heparin-coated circuits and reduced systemic anticoagulation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:438–44. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(96)01099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lange M, Ertmer C, Van Aken H, Westphal M. Intravascular volume therapy with colloids in cardiac surgery. Jr of Cardiothor and Vasc Anesth. 2011;25:845–55. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Westphal M, James MF, Kozek-Langenecker SA, Stocker R, Guidet B, Van Aken H. Hydroxyethyl starches: different products—different effects. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:187–202. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181a7ec82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boldt, Joachim Modern rapidly degradable hydroxyethyl starches: current concepts. Int Anesth Research Society. 2009;108:1574–82. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31819e9e6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vuiblet V, Nguyen TT, Wynckel A, et al. Contribution of Raman spectroscopy in nephrology: a candidate technique to detect hydroxyethyl starch of third generation in osmotic renal lesions. Analyst. 2015;140:7382–90. doi: 10.1039/c5an00821b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jungheinrich C, Sauermann W, Bepperling F, Vogt NH. Volume efficacy and reduced influence on measures of coagulation using hydroxyethyl starch 130/0. 4 (6%) with an optimised in vivo molecular weight in orthopaedic surgery: a randomised, double-blind study. Drugs RD. 2004;5:1–9. doi: 10.2165/00126839-200405010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin C, Jacob M, Vicaut E, Guidet B, Van Aken H, Kurz Al. Effect of waxy maize-derived hydroxyethyl starch 130/0. 4 on renal function in surgical patients. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:387–94. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31827e5569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reilly C. Retraction. Notice of formal retraction of articles by Dr. Joachim Boldt Br J Anesth. 2011;107:116–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, Levey AS. Assessing kidney function—measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Eng Jr Med. 2006;354:2473–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra054415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robert RS, Herron CR, Groom RC, Brown JR. Acute kidney injury subsequent to cardiac surgery. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2015;47:16–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar AB, Suneja M, Bayman E, Weide GD, Tarasi M. Association between postoperative acute kidney injury and duration of cardiopulmonary bypass: meta-analysis. Jr of CardThor and Vasc Anesthesia. 2012;26:64–9. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winkelmayer WC, Glynn RJ, Levin R, Avorn J. Hydroxyethyal starch and change in renal function in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Kidney Int. 2003;64:1046–49. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rioux JP, Lessard M, de Bortoli B, et al. Pentastarch 10% (250kDa/0. 45) is an independent risk factor of acute kidney injury following cardiac surgery. Crit Care Med. 2009;31:1293–98. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819cc1a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kozek-Langenecker SA. Effects of hydroxytheyl starche solution on hemostasis. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:654–60. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200509000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuitunen AH, Hynynen MJ, Vahtera E, Salmenpera MT. Hydroxyethyl starch as a priming solution for cardiopulmonary bypass impairs hemostasis after cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:291–97. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000096006.60716.F6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niemi T, Schramko A, Kuitunen A, Kukkonen S, Suojaranta-Ylinen R. Haemodynamics and acid-base equilibrium after cardiac surgery: comparison of rapidly degradable hydroxyethyl starch solutions and albumin. Scand J Surg. 2008;97:259–65. doi: 10.1177/145749690809700310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schramko AA, Suojarnanta-Ylinen RT, Kuitunen AH, Kukkonen S, Niemi TT. Rapidly degradable hydroxyethyl starch solutions impair blood coagulation after cardiac surgery: a prospective randomized trial. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:30–6. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31818c1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neff TA, Doelberg M, Jungheinrich C, Sauerland A, Spahn DR, Stocker R. Repetitive large-dose infusion of the novel hydroxyehtyl starch 130/0. 4 in patients with severe head injury. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:1453–9. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000061582.09963.FD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langeron O, Doelberg M, Ang ET, Bonnet F, Capdevila X, Coriat P. Voluven, a lower substituted novel hydroxyethyl starch (HES 130/0.4), causes fewer effects on coagulation in major orthopedic surgery than HES 200/0. 5. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:855–62. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200104000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hecht-Dolnik M, Barkan H, Taharka A, Loftus J. Hetastarch increases the risk of bleeding complicaitons in patients after off-pump coronary bypass surgery: a randomized clinical trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:703–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Avorn J, Patel M, Levin RW, Winkelmayer W. Hetastarch and bleeding complications after coronary artery surgery. Chest. 2003;124:1437–42. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.4.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones SB, Whitten CW, Despotis GJ, Monk TG. The influence of crystalloid and colloid replacement solutions in acute normovolemic hemodilution: A preliminary survey of hemostatic markers. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:363–8. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200302000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gandhi S, Warltier D, Weiskopf R, Bepperling F, Baus D, Jungheinrich C. Volume substitution therapy with HES 130/0.4 (Voluven) vs HES 450/0.7 (hetastarch) during major orthopedic surgery (abstract) Crit Care. 2005;9:P206. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lowell J, Schifferdecker C, Driscoll D, Benotti PN, Bistrian BR. Postoperative fluid overload: Not a bening problem. Crit Care Med. 1990;18:728–33. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199007000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krzych L, Wybraniec M, Chudek J, Bochenek A. Perioperative management of cardiac surgery patients who are at the risk of acute kidney injury. Anesth Inten Therapy. 2013;45:155–63. doi: 10.5603/AIT.2013.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA, Mehta RL, Palevsky P. Acute renal failure - definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the Second International Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Group. Crit Care Aug. 2004;8(4):R204–12. doi: 10.1186/cc2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Endre ZH. Acute Kidney Injury: Definitions and new paradigms. Kidney International Supplements. 2012;2:19–36. [Google Scholar]