Abstract

This study evaluates quantitatively the impact that intermittent Aortic Valve opening has on the thrombogenicity in the aortic arch region for patients under Left Ventricular Assist Device therapy. The influence of flow through the Aortic Valve, opening once every five cardiac cycles, on the flow patterns in the ascending aortic is measured in a patient-derived CT-image-based model, after LVAD implantation. The mechanical environment of flowing platelets is investigated, by statistical treatment of outliers in Lagrangian particle tracking, and thrombogenesis metrics (platelet residence times and activation state characterized by shear stress accumulation) are compared for the cases of no Aortic Valve opening and intermittent Aortic Valve opening. All hemodynamics metrics are improved by Aortic Valve opening, even at a reduced frequency and flow rate. Residence times of platelets or microthrombi are reduced significantly by transvalvular flow, as are the shear stress history experienced and the shear stress magnitude and gradients on the aortic root endothelium. The findings of this device-neutral study support the multiple advantages of management that enables Aortic Valve opening, providing a rationale for establishing this as a standard in long-term treatment and care for advanced heart failure patients.

Keywords: LVAD, Mechanical Circulatory Support, Thrombosis, Platelet history, Computational Cardiovascular Fluid Mechanics, Aortic Valve opening, Thrombogenicity, Shear Stress, Residence Time

1 INTRODUCTION

Heart failure continues to increase in prevalence and is a major global contributor to morbidity, mortality and health care expense burden1,2. An inadequate supply of suitable donor hearts has necessitated increased use of Ventricular Assist Device (VAD) therapy and prolonged durations of mechanical support in end-stage HF3,4. Although device technology has improved, thrombosis and neurologic events remain among the most devastating complications of long-term therapy. Consequently, it is imperative to actively pursue device implantation and management strategies that improve biocompatibility and reduce potentially preventable complications. One such opportunity exists in VAD speed optimization as it pertains to intermittent aortic valve (AV) opening.3–6.

The clinical benefits of VAD therapy include left ventricular (LV) unloading and increased systemic perfusion, however, contemporary VADs pump blood continuously, thereby disrupting physiological pulsatile blood flow, especially in the aorta and great vessels. Along the continuum of potential VAD speeds, depending on residual native contractility, the device can function in parallel with the native heart (AV opening with each cardiac cycle), entirely in series (AV never opens, all blood flows through the VAD) or a combination (intermittent AV opening). With a closed AV, all blood entering the LV transits the VAD, and the outflow graft pressure is the sum of the contributions from residual native LV contractility and continuous VAD pressure (operation in series). With intermittent AV opening, the majority of blood in the LV still exits as continuous flow through the LVAD, and the resulting aortic root pressure must be matched for both pumps, left ventricle and LVAD. The total systemic perfusion is the sum of flow rates through each of the pathways (intermittent parallel operation). In either case, the AV experiences a markedly altered transvalvular pressure gradient (pressure differential between the LV and aortic root) which determines the frequency of AV opening, the amount of native AV blood flow, and duration of blood flow during systole.

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) is a powerful tool to investigate MCS hemodynamics. First efforts to characterize VAD flow focused on hemodynamic parameters (e.g. Wall shear stress), following the atherosclerosis mechanotransduction pathway, and were limited to steady flow models7–11. In reality, platelet activation and aggregation, essential to understanding thrombus initiation and propagation,12,13 are associated with shear stress and residence time of flowing platelets and require modeling and computation via a different methodology (Lagrangian14). This holistic approach makes it feasible to quantify the mechanical stimuli experienced by platelets as well as the endothelium, providing more complete metrics for evaluating thrombogenicity. Using a novel combination of Lagrangian (platelet-level) and Eulerian (endothelium-level) fluid variables, the impact of native trans-aortic valve flow on thrombotic risk during VAD support is quantified. We hypothesize that intermittent AV opening is beneficial in reducing cumulative thrombogenicity in the aortic root. Our objective is to quantify the impact of intermittent AV opening and describe a risk assessment metric to reduce risk of stroke.

Model development, including platelet dynamics, is described in Section 2, and the influence of AV opening on hemodynamics and thrombogenicity presented in Section 3. Discussion of the clinical implications from this device-neutral computational modeling approach and the goal of setting efficient LVAD management strategies for long-term LVAD therapy, followed by brief conclusions, close the paper.

2 Methods

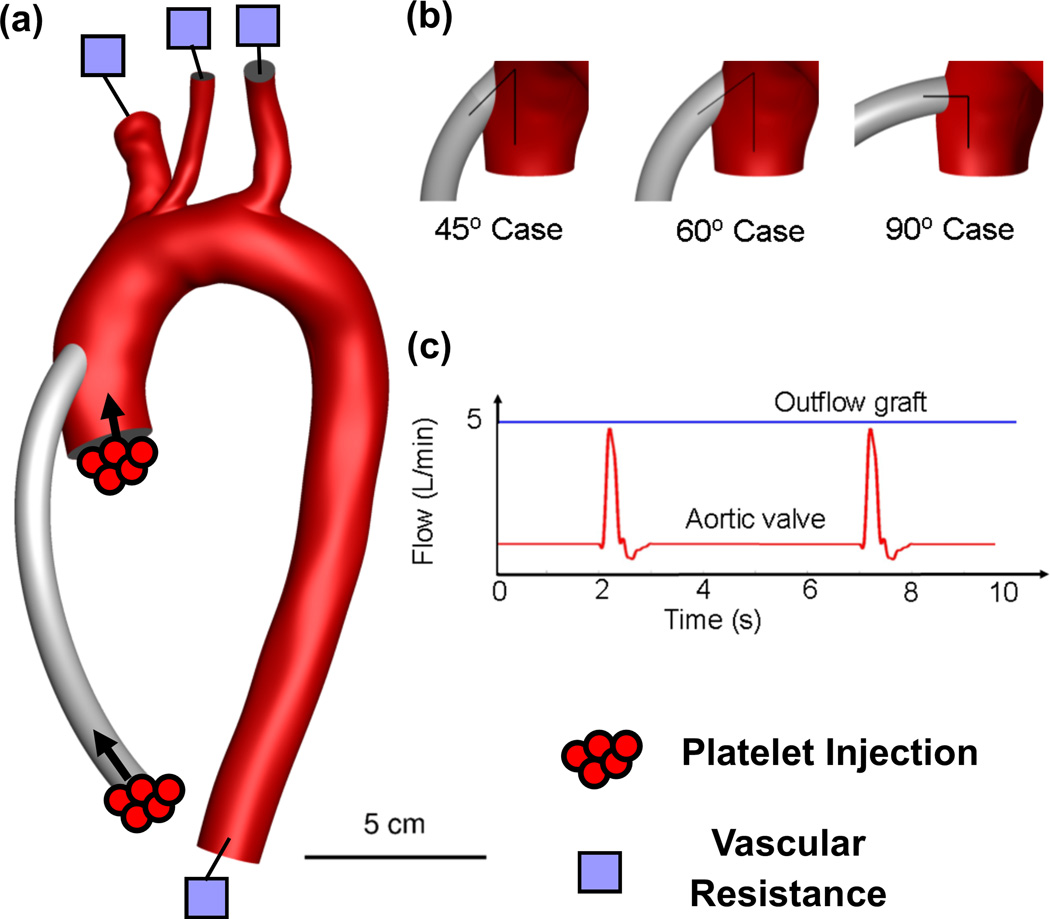

The methodology developed to investigate the impact of intermittent AV opening on thrombogenicity is based on a 3D patient-specific model where the LVAD outflow graft has been virtually implanted. CFD simulations of blood flow, including platelet-surrogate dynamics, are performed for the different conditions14. Briefly, image segmentation was performed on Gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) images of patient vasculature of the ascending aorta and great vessels. A 3D surface was reconstructed using the segmented vessel outlines of the aorta and great vessels, and a 10mm diameter LVAD outflow graft was “virtually anastomosed” 25 mm distal to the AV plane and at a 65° anterior-posterior angle from the aortic arch plane, in standard surgical fashion. A tetrahedral mesh of ~5 million cells (typical mesh spacing ~ 100 microns) is applied with high temporal resolution (Δt=10−4 s) to accurately capture realistic chaotic flow without resorting to turbulence models that focus on average, not instantaneous or small scale, flow properties. A baseline physiologic flow of 5 L/min through the outflow graft, and a partial, intermittent (every fifth cardiac cycle) flow of 0.5 L/min through the AV, typical of LVAD-supported patients15, are used as inlet boundary conditions. Two-element vascular resistance-capacitance elements, with physiologically-realistic values of peak systolic and mean flow splits are used at each of the four outlets (i.e. brachiocephalic, carotid, subclavian and descending aorta). Arterial walls are considered rigid, and the simulations initialized for 3 cardiac cycles prior to particle injection for 10 cardiac cycles.

A continuous phase models blood as a homogeneous Newtonian fluid, and platelets are modeled as suspended, neutrally-buoyant particles transported by the continuous phase. 3-micron platelets are injected every 0.1s and individually tracked for the duration of the simulation. The particle residence time (RT) was calculated by tracking the time each particle remained in the vascular domain:

Where i is an index for each particle, represents the time the particle is injected into the domain, and represents the time the particle trajectory ends as a particle exits the domain or the simulation is terminated. While many factors influence platelet activation, one of the most widely accepted theories is shear-induced platelet-activation (SIPA). Lagrangian tracking allows for determination of accumulated shear stress on each platelet, as a function of time in the flow, to evaluate the level of SIPA associated with each LVAD outflow graft angle studied:

Where τ is the instantaneous shear stress magnitude at time t′ and X(t′) is the platelet’s location at that time.

TP is intended to rank-order the relative thrombogenic potential of the different cases investigated14 (on a normalized scale from 0 to 1), but not to evaluate an absolute risk of thrombosis (i.e. a value of 1 represents a higher risk than 0.5, but does not indicate that the probability of thrombosis is twice as high). TP incorporates statistical parameters such as median, maximum and outliers of both particle RT and SH.

3 RESULTS

Wall shear stress and particle trajectory RT and SH are computed over 10 cardiac cycles. Thrombogenic potential in the ascending aorta post-LVAD is calculated based on those hemodynamic metrics, and the effect of intermittent aortic valve opening ranked based on this analysis.

3.1 Blood flow patterns

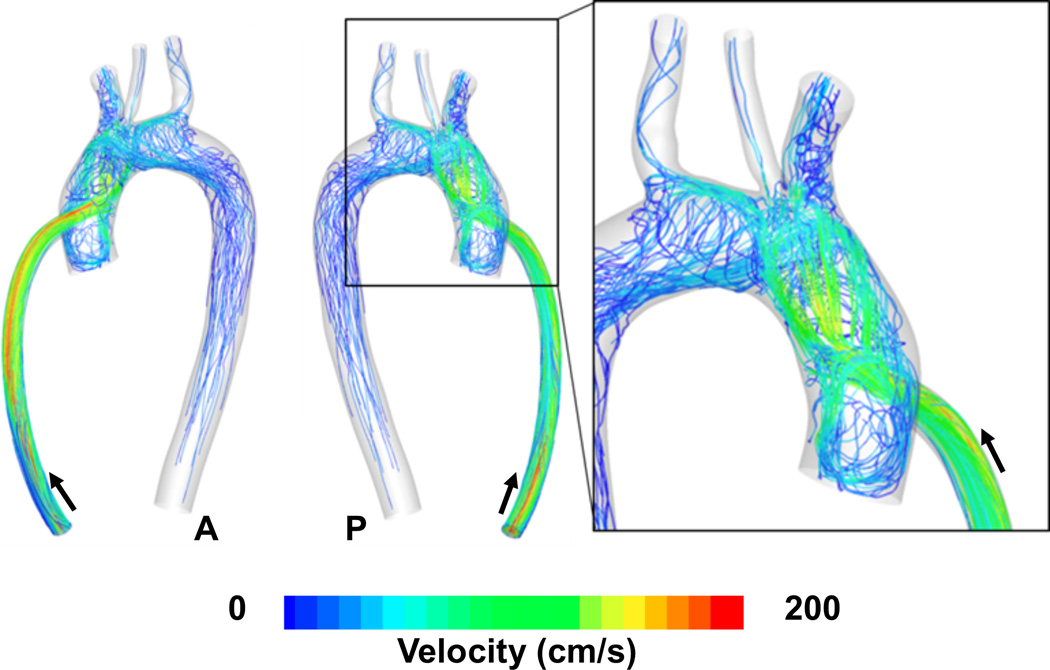

3.1.1 Closed Aortic Valve

The high-velocity jet from the outflow graft impinges on the contralateral aortic wall forming a stagnation region, with high pressure and low shear stress at the stagnation point, surrounded by concentric rings of decreasing pressure and extremely high shear stress. There is a strong flow redirection and multiple pathlines spiral out from the central stagnation point, traversing the ascending aorta and aortic arch. A significant recirculating region appears in the aortic root, just distal to the aortic valve, with associated low shear and prolonged cell residence times adjacent to the area of high shear associated with the jet and wall impingement.

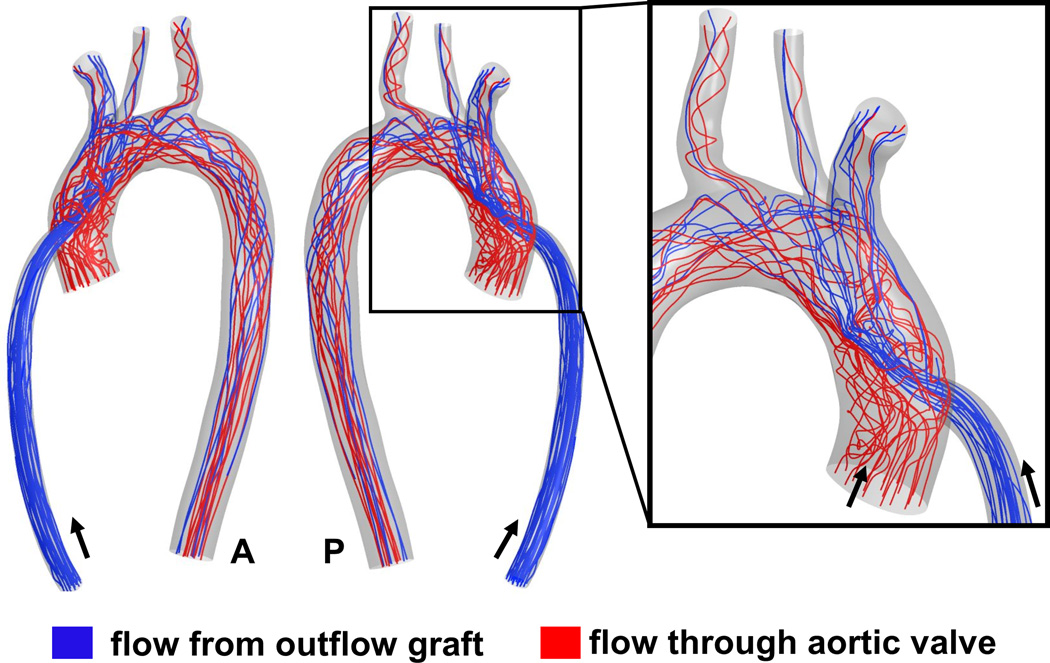

3.1.2 Intermittent Aortic Valve Opening

AV opening significantly impacts aortic root hemodynamics. The high-velocity jet from the outflow graft is redirected distally, even by diminished native AV flow contribution typical of partial valve opening. This washes out stagnant blood from the aortic root, preventing prolonged periods of recirculation and platelet aggregation. Mixing of blood streams from the outflow graft and AV results in less spiraling hemodynamics in the aortic arch. The recirculation region in the aortic root vanishes with AV opening, but immediately recurs with closure and persists until the next valve opening.

3.2 Platelet-level metrics

100,000 particles each are analyzed, for both physiologic states. Platelets traveling toward the brain (i.e. exiting through the brachiocephalic, carotid and subclavian branches) are emphasized in this section, in an effort to further elucidate clinical stroke risk.

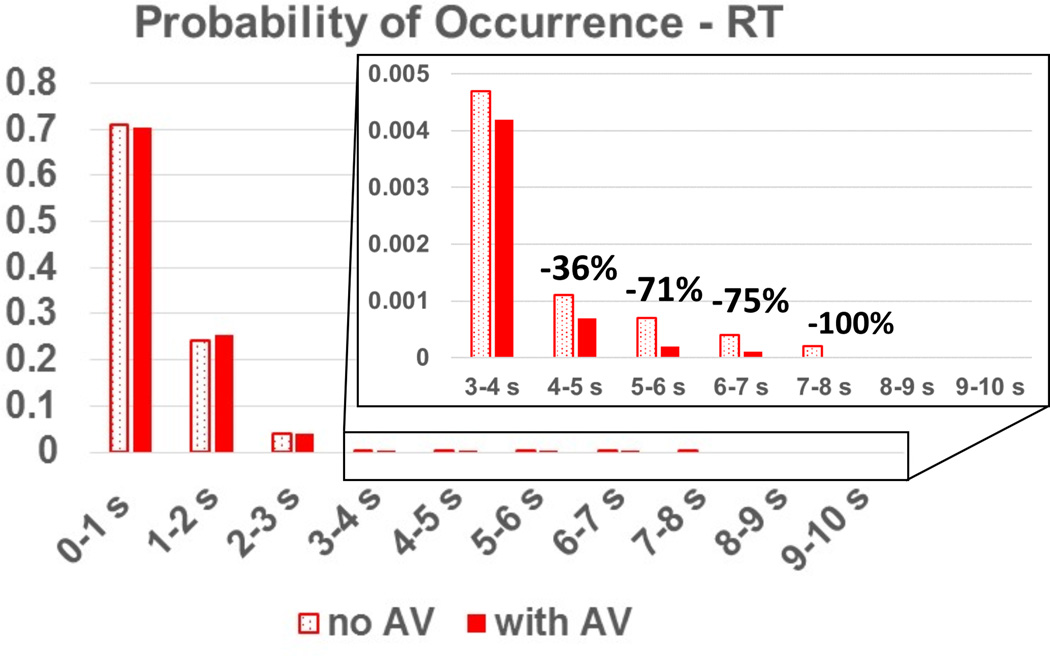

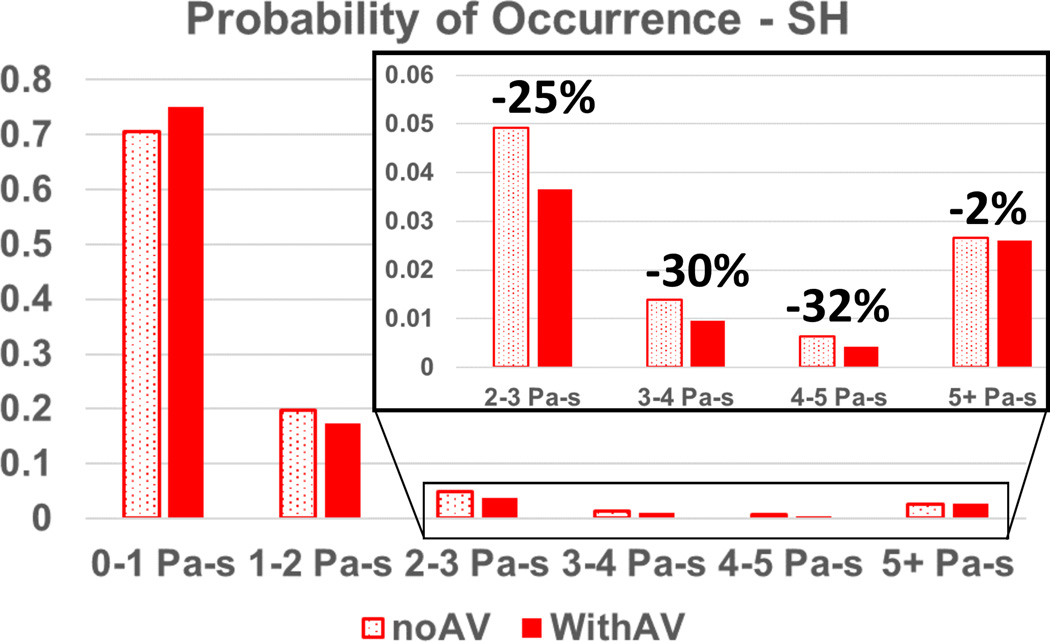

The benefits of intermittent AV opening are supported by the outlier analysis in both platelet RT and SH: the cumulative probability that particles linger for a duration of more than 5s is reduced by up to 250% with intermittent AV opening, compared to a closed valve, and the cumulative probability that a particle accumulates a SH higher than 2 Pa-s is reduced by up to 90%. These results are shown in the inset of Figure 4 and Figure 5. While the median RT actually increased by ~4% for the AV opening case, and the median SH decreased by 7%, these values are low and well within the established normal physiological range. It is the pathological outliers that disrupt homeostatic thrombotic-thrombolytic equilibrium.

Figure 4.

Probability of occurrence of particle RT for an outflow graft at a 90° angle with the aortic axis. Note the reduction in particles lingering for long RT for the AV opening scenario.

Figure 5.

Probability of occurrence of particle SH for an outflow graft at 45° with the aortic axis. Note the reduction of particles exposure to high SH for the AV opening scenario.

Table 1 shows detailed RT and SH statistics for particles in all configurations traveling towards the cerebral circulation.

Table 1.

Median and outlier information of RT and SH for particles traveling towards the brain.

| RT | SH | FINAL TP SCORE |

TP % chg due to AV flow |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CASE | MEDIAN (s) |

OUTLIER MAX (s) |

OUTLIER % |

MEDIAN (Pa-s) |

OUTLIER MAX (Pa-s) |

OUTLIER % |

||

| 45 noAV | 0.39 | 8.89 | 12.7 | 0.63 | 119.54 | 9.04 | 0.14 | −14% |

| 45 w/AV | 0.4 | 9.1 | 11.9 | 0.59 | 230.93 | 8.1 | 0.00 | |

| 60 noAV | 0.36 | 9.19 | 7.88 | 0.54 | 120.84 | 10.03 | 1.00 | −26% |

| 60 w/AV | 0.4 | 7.84 | 9.47 | 0.58 | 140.95 | 11.47 | 0.74 | |

| 90 noAV | 0.64 | 7.76 | 16.21 | 0.91 | 133.95 | 12.08 | 0.94 | −70% |

| 90 w/AV | 0.67 | 8.47 | 11.19 | 0.86 | 86.82 | 12.55 | 0.24 | |

While the results highlighted here are for the subset of particles traveling towards the cerebral circulation, the trends are fully consistent with statistics for all platelets, and irrespective of outflow graft angle14: intermittent AV opening has a globally beneficial effect on both RT and SH for all injected particles.

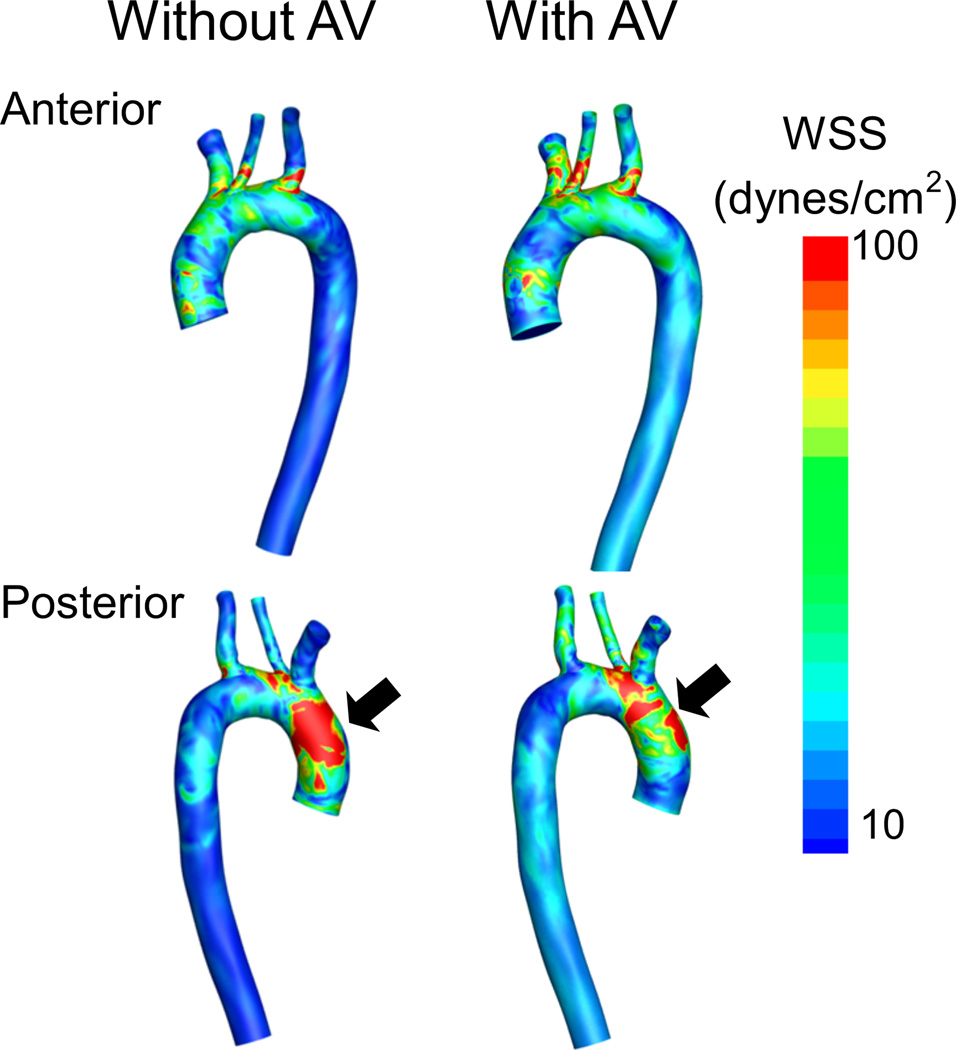

3.3 Eulerian hemodynamic parameters

With a closed AV, WSS distributions on the ascending aorta, aortic arch, ostia of the great vessels and descending aorta indicate a concentration of high WSS at the posterior aortic arch, proximal to the brachiocephalic area. This high WSS zone correlates to the high velocity impingement jet from the outflow graft. With any intermittent AV opening, the maximum instantaneous shear stress resulting from the impingement of the high-velocity jet from the outflow graft is markedly reduced. Flow through the AV redirects the high velocity jet away from the contralateral aortic wall while the AV remains open. Upon AV closure, this WSS zone reappears. While WSS on the aortic arch endothelium decreases as the angle of the outflow graft becomes more shallow (WSS45 < WSS60 < WSS90), overall no configuration globally minimized WSS.

3.4 Evaluation of thrombogenic potential (TP)

A weighted average of platelet RT and SH median and outlier percentages has been developed and used to produce a relative risk assessment of TP (Lower TP scores indicate lower thrombogenicity and hence reduced risk of thrombosis and embolization). Overall, intermittent AV opening reduced thrombogenicity for all surgical LVAD outflow graft angles: 70% at 90° outflow graft angle, 26% at 60° angle and 14% at 45° angle. This result also confirms the findings of a previous study; more acute outflow graft angles are beneficial in reducing thrombogenicity, with the clinically realistic management strategy of aiming to adjust VAD speed to allow for intermittent AV opening. The TP scores are detailed in table 1.

4 DISCUSSION

A VAD support strategy that compares a permanently closed AV to an intermittently opening AV has been evaluated utilizing Lagrangian metrics for platelet surrogates traversing the aortic arch. Hundreds of thousands of platelet trajectories are analyzed to provide statistically meaningful information about the thrombogenicity and hemodynamic environment in the aortic root, arch and major vessels to the brain. When the AV does not open, platelets are up to 250% more likely to take 5s or longer to transit the ascending aorta and aortic arch, due to encountering recirculation regions, and being trapped in stagnation zones. Particles entrapped in these regions find it increasingly difficult to travel downstream, and could thus be circulating in this stagnation zone for extended periods of time, sufficient to initiate platelet aggregation and form the nidus of an organized thrombus or de-novo micro-thrombi. Prolonged residence times are a necessary step towards aggregation following flow-induced platelet activation16–18. Intermittent AV opening had a strong beneficial effect by reducing the risk of platelet stasis and aggregation. Intermittent AV opening is holistically beneficial, irrespective of outflow graft angle.

Hemodynamic shear stress exacerbates thrombogenicity via shear-induced-platelet-activation (SIPA) and platelet microparticle formation16,18–20. Intermittent AV opening has a profound effect on platelet SH: levels of shear stress history, quantified by tracking individual platelets, are markedly higher with a closed AV and, more importantly, the probability of platelet exposure to outlier levels of elevated SH are reduced by up to 90% with intermittent AV opening.

Among the sequelae of chronic supraphysiologic VAD support observed clinically are neurologic events, the occurrence of AV cusp fusion, aortic stenosis (AS) and aortic regurgitation (AR)15,21. The detrimental effects of AV pathology in VAD support, well described in several case series, are observed in 25 – 50% of patients21–24. A recent study demonstrated that AR was prevalent in nearly 83% of LVAD patients with closed AV during VAD support, while in patients with intermittent AV opening, only 3% of patients developed AR22. Several investigators have proposed adapting VAD speed to reduce risk of AV pathology and promote washout of the aortic root25–27.

In this study, intermittent AV opening reduced the compounded thrombogenicity of platelets traveling towards the cerebral circulation for all outflow graft angles. The advantages of a support strategy targeted to permit intermittent AV opening are amplified further when integrated holistically: (i) it promotes physiologic mixing of blood from the LV and aortic root, thus enabling washout of platelets otherwise trapped for extended periods of time, both proximal and distal to the AV (ii) it promotes AV integrity by preserving physiologic AV function, reducing the risk of developing de novo AV pathology over prolonged durations of support26,28, and (iii) reducing the need for AV interventions and their associated morbidity and mortality over time25,29).

VAD thrombosis is a multi-faceted, biologically complex phenomenon and as such, requires a sophisticated and nuanced approach to investigate. While prior attempts have been made to characterize thrombosis using simpler parameters7–11 and diffusive stagnation approaches30, the Lagrangian particle tracking approach tracks over 100,000 individual platelets to provide a uniquely nuanced and physiologically realistic description of the platelet mechanical environment and behavior: residence times and shear stress accumulation critical to understanding the pathogenesis of thrombus initiation12,13.

We present a pioneering approach to quantify the impact of technical and surgical factors affecting overall thrombogenicity of VAD therapy. This previously validated methodology not only allows for the translational ability to improve outcomes with existing device platforms, but also to apply these findings to future technological advances. The use of personalized computational analysis to surgical planning has the potential to improve biocompatibility beyond what device optimization has, and to reduce the incidence of the most devastating complications of VAD support.

Limitations

Rigid walls were assumed for all vascular and graft boundaries. While this is a restrictive assumption, in LVAD-supported patients, the LV is unloaded and the native systolic contribution to the ΔP when the AV is open is dramatically reduced, compared to the healthy physiology. The systolic to diastolic pressure ratio is close to one, and as a result the aortic compliance does not play the dominant role in keeping forward flow during diastole (< 1 L/min), with that role played by the LVAD that provides a constant flow (80% of the total) and aortic pressure, modulated by only a few mmHg by the AV opening. The focus of this study is on global risk stratification of LVAD configuration and management strategies, regarding their relative thrombogenicity, not on quantitative values that will inherently be patient and device specific. While compliance may modify flow stresses quantitatively by up to 15%31, the qualitative behavior of the hemodynamics in the vasculature studied would effectively remain the same. Additionally, the demographics of advanced heart failure HF and typical VAD patients support the use of this simplification. This is a single geometry study. It focuses on trends of aortic valve opening on different outflow graft anastomoses angles, which remains robust for the vast majority of clinical scenarios, and a range of aortic anatomy, as well as most contemporary VAD configurations, with the exception of subclavian outflow graft placement, which is beyond the scope of this study. A range of patient-specific models will be considered in future studies, to investigate this phenomenon.

5 Conclusion

The very nature of continuous flow VAD support results in vastly altered hemodynamic physiology in the aorta and human circulation overall. Improving the outcome of long-term VAD support requires actively focusing on reducing complications by optimizing surgical configuration and improving patient management strategies.

This study presents a methodology that has the potential to translate personalized surgical planning from the lab to the bedside, enabling LVAD optimization in a patient-specific manner. The combination of technological and surgical factors in understanding thromboembolic events has the potential to open a new field in personalized medicine, with computational tools that are directly and quantifiably linked to improve outcomes.

In this work, we focus on the hemodynamic impact of AV opening in VAD support. Intermittent AV opening is measurably beneficial on holistic parameters associated with overall device thrombogenicity. We demonstrate that an LVAD management strategy permitting intermittent AV opening, even partially and at low frequency, results in major, globally quantifiable hemodynamic benefits and overall improved biocompatibility by promoting platelet washout, reducing stasis and decreasing thrombogenicity.

Current clinical guidelines do not incorporate specific recommendations for device management strategies targeting intermittent AV opening, despite its potential impact on the pathologic sequelae of continuous flow VAD support. This study presents a comprehensive, device-neutral analysis of platelet residence time/shear stress histories (platelet-level) and wall shear stress (endothelial-level) metrics quantifying the impact of intermittent AV opening on thrombogenic risk for various configurations.

Intermittent AV opening, even partially and at a low frequency has significant benefits. Specifically, AV opening reduces the probability that a platelet traveling towards the cerebral circulation would be subject to activation by high accumulated shear stress history by 90% and that it would linger in the aortic root region, promoting aggregation, by 250%. This quantifies the answer to the hypothesis that AV opening can significantly reduce exposure of platelets to thrombogenic flow patterns, mechanical stresses and stagnation, thereby reducing overall thrombogenicity of LVAD surgical configurations.

These benefits are in addition to the previously established benefits of AV opening such as a reduction in the development of de-novo aortic valve pathology and AR. While further prospective clinical investigations are necessary to fully characterize the benefits of intermittent AV flow, this study should catalyze a paradigm shift in VAD care, by supporting management strategies that enable intermittent AV opening.

Whenever possible, clinicians should aim for VAD management strategies that allow for at least partial, intermittent AV opening to improve device-patient biocompatibility and reduce the risk of some of the major complications of long-term continuous flow support.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

(a) Patient-derived model of the aortic vasculature with the main branches and a virtually anastomosed 10 mm diameter LVAD outflow graft (b) the three outflow graft surgical anastomoses configurations investigated in this study (c) the unsteady blood flow rate applied as an input to the outflow graft (5 L/min) and the aortic valve (one opening every five cardiac cycles)

Figure 2.

Hemodynamic flow patterns (pathlines) in the outflow graft and aortic region for the 90° configuration with No AV opening. Note the spiraling of multiple trajectories from the central jet and the strong recirculation region at the base of the aortic root. Arrows indicate direction of flow. A: anterior, P: posterior

Figure 3.

Hemodynamic flow patterns (pathlines) in the outflow graft and aortic region for the 90° configuration when the AV opens intermittently. Note the strong influence of AV flow in redirecting the high velocity outflow graft jet downstream and the temporary elimination of the recirculation region at the base of the aortic root. Arrows indicate direction of flow. A: anterior, P: posterior

Figure 6.

Instantaneous WSS magnitude plotted with isocontours along the arterial luminal surface for the 90° configuration. Note the reduction in shear on the contralateral wall due to intermittent AV opening in the posterior view (black arrows). Outflow graft not shown for clarity.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the High Performance Computing (HPC) group for providing the high performance computing facility (Hyak) at the University of Washington to conduct the simulations described in this study.

Conflicts of interest: NAM has a consulting relationship with St. Jude and HeartWare, and is an investigator for St. Jude, HeartWare, and SynCardia. CM has consulting relationships with St. Jude, Abiomed and HeartWare and is an investigator for St. Jude, HeartWare, and SynCardia, JB has consulting relationships with Abiomed, HeartWare and St. Jude.

Footnotes

Disclaimers: None

References

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2014 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. 2014 doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, et al. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:606–619. doi: 10.1161/HHF.0b013e318291329a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mancini D, Colombo PC. Left Ventricular Assist Devices: A Rapidly Evolving Alternative to Transplant. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:2542–2555. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mulloy DP, Bhamidipati CM, Stone ML, Ailawadi G, Kron IL, Kern Ja. Orthotopic heart transplant versus left ventricular assist device: a national comparison of cost and survival. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:566–573. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.10.034. discussion 573–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lampropulos JF, Kim N, Wang Y, et al. Trends in left ventricular assist device use and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries, 2004–2011. Open Hear. 2014;1:e000109. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2014-000109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Information UHNP. Left Ventricular Assist Devices. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farag MB, Karmonik C, Rengier F, et al. Review of Recent Results Using Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulations in Patients Receiving Mechanical Assist Devices for End-Stage Heart Failure. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2014;10:185–189. doi: 10.14797/mdcj-10-3-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karmonik C, Partovi S, Schmack B, et al. Comparison of hemodynamics in the ascending aorta between pulsatile and continuous flow left ventricular assist devices using computational fluid dynamics based on computed tomography images. Artif Organs. 2014;38:142–148. doi: 10.1111/aor.12132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.May-Newman K, Hillen B, Dembitsky W. Effect of left ventricular assist device outflow conduit anastomosis location on flow patterns in the native aorta. ASAIO J. 2006;52:132–139. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000201961.97981.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ong C, Dokos S, Chan B, et al. Numerical investigation of the effect of cannula placement on thrombosis. Theor Biol Med Model. 2013;10:35. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-10-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bazilevs Y, Gohean JR, Hughes TJR, Moser RD, Zhang Y. Patient-specific isogeometric fluid-structure interaction analysis of thoracic aortic blood flow due to implantation of the Jarvik 2000 left ventricular assist device. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2009;198:3534–3550. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chandran K, Rittgers S, Yoganathan A. Biofluid mechanics: the human circulation. CRC Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Widmaier R, Raff H, Strang K. Vander’s human physiology: the mechanisms of body function with aris, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aliseda A, Chivukula VK, McGah P, Prisco AR, Beckman JA, Garcia JMG, Mokadam NA, Mahr C. LVAD Outflow Graft Angle and Thrombosis Risk. ASAIO J. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000443. Manuscript #16215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.May-Newman K, Enriquez-Almaguer L, Posuwattanakul P, Dembitsky W. Biomechanics of the aortic valve in the continuous flow VAD-assisted heart. ASAIO J. 2010;56:301–308. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e3181e321da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Para a, Bark D, Lin a, Ku D. Rapid platelet accumulation leading to thrombotic occlusion. Ann Biomed Eng. 2011;39:1961–1971. doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramstack JM, Zuckerman L, Mockros LF. Shear-induced activation of platelets. J Biomech. 1979;12:113–125. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(79)90150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Einav S, Bluestein D. Dynamics of blood flow and platelet transport in pathological vessels. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1015:351–366. doi: 10.1196/annals.1302.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sankaran S, Marsden AL. A stochastic collocation method for uncertainty quantification and propagation in cardiovascular simulations. J Biomech Eng. 2011;133:031001. doi: 10.1115/1.4003259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chesnutt JKW, Han H-C. Computational simulation of platelet interactions in the initiation of stent thrombosis due to stent malapposition. Phys Biol. 2016;13:016001. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/13/1/016001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mudd JO, Cuda JD, Halushka M, Soderlund KA, Conte JV, Russell SD. Fusion of Aortic Valve Commissures in Patients Supported by a Continuous Axial Flow Left Ventricular Assist Device. J Hear Lung Transplant. 2008;27:1269–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2008.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aggarwal A, Raghuvir R, Eryazici P. The development of aortic insufficiency in continuous-flow left ventricular assist device–supported patients. Ann Thorac. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pak S, Uriel N, Takayama H. Prevalence of de novo aortic insufficiency during long-term support with left ventricular assist devices. J Hear. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samuels LE, Thomas MP, Holmes EC, et al. Insufficiency of the native aortic valve and left ventricular assist system inflow valve after support with an implantable left ventricular assist system: Signs, symptoms, and concerns. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;122:380–381. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.114770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tolpen S, Janmaat J, Reider C, Kallel F, Farrar D, May-Newman K. Programmed Speed Reduction Enables Aortic Valve Opening And Increased Pulsatility in the LVAD-Assisted Heart. ASAIO J. 2015:1. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Camboni D, Lange TJ, Ganslmeier P, et al. Left ventricular support adjustment to aortic valve opening with analysis of exercise capacity. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;9:93. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-9-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tuzun E, Gregoric ID, Conger JL, et al. The Effect of Intermittent Low Speed Mode Upon Aortic Valve Opening in Calves Supported With a Jarvik 2000 Axial Flow Device. ASAIO J. 2005;51:139–143. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000155708.75802.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.John R, Mantz K, Eckman P, Rose A, May-Newman K. Aortic valve pathophysiology during left ventricular assist device support. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29:1321–1329. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cowger JA, Aaronson KD, Romano MA, Haft J, Pagani FD. Consequences of aortic insufficiency during long-term axial continuous-flow left ventricular assist device support. J Hear Lung Transplant. 2014;33:1233–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rayz VL, Boussel L, Ge L, et al. Flow residence time and regions of intraluminal thrombus deposition in intracranial aneurysms. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010;38:3058–3069. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-0065-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGah P, Leotta D, Beach K, Aliseda A. Effects of wall distensibility in hemodynamic simulations of an arteriovenous fistula. Biomech Model. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10237-013-0527-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.