Abstract

Linoleic acid (LA; 18:2 n-6), the most abundant polyunsaturated fatty acid in the US diet, is a precursor to oxidized metabolites that have unknown roles in the brain. Here, we show that oxidized LA-derived metabolites accumulate in several rat brain regions during CO2-induced ischemia and that LA-derived 13-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid, but not LA, increase somatic paired-pulse facilitation in rat hippocampus by 80%, suggesting bioactivity. This study provides new evidence that LA participates in the response to ischemia-induced brain injury through oxidized metabolites that regulate neurotransmission. Targeting this pathway may be therapeutically relevant for ischemia-related conditions such as stroke.

Introduction

Omega-6 linoleic acid (LA, 18:2 n-6) is the most consumed polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) in the US diet, accounting for approximately 7% of daily calories1. The consumption of its elongation-desaturation product, arachidonic acid (AA, 20:4n-6), as well as omega-3 α-linolenic acid (ALA, 18:3n-3), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5n-3) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3), collectively account for less than 1% of calories. Despite being the main PUFA in the diet, little is known about the role of LA in the brain.

Most brain studies have focused on AA and DHA, because they are enriched in phospholipid membranes, and are known to regulate many processes including blood flow2–4, pain signaling5–7, inflammation8 and the resolution of inflammation9–13 through oxidized metabolites known as oxylipins. PUFA-derived oxylipins are synthesized via lipoxygenase (LOX)14–16, cyclooxygenase (COX)15, 17, 18, cytochrome P450 (CYP450)19–21 or soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) enzymes6, 22 following phospholipase-mediated release of fatty acids from brain membrane phospholipids23, 24. Oxylipin synthesis can also occur non-enzymatically25–27.

Unlike AA and DHA, which make up over 20% of brain total fatty acids, LA accounts for less than 2% of total fatty acids28, but enters the brain at a comparable rate to AA and DHA (4–7 pmol/g/s)29, 30. Instead of incorporating into membrane phospholipids, however, up to 59% of the LA entering the brain is converted into relatively polar compounds29, which include LA-derived oxylipins31 produced non-enzymatically or via the same LOX, COX, CYP450 and sEH enzymes that act on AA and DHA17, 32–34.

Brain injury caused by hypoxia, ischemia, seizures or trauma activates excitatory N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors coupled to phospholipase enzymes35–37, which release AA and DHA from membrane phospholipids38–43. The majority of unesterified AA and DHA are re-esterified into the phospholipid membrane44, whereas a small portion (~3%) is converted via non-enzymatic or enzymatic pathways into oxylipins41, 45–47 that regulate the brain’s response to injury2–4. This response involves oxylipins that acutely down-regulate neuronal hyperexcitability48 and enhance vasodilation49 as a protective mechanism.

Brain unesterified LA concentration also increases following brain injury24, 40, suggesting that LA or its metabolites may be involved in the response to brain injury. However, very little is known about the role of LA or its metabolites in brain. LA was reported to raise seizure threshold in rats50, 51, and to increase the number and duration of spontaneous wave discharges in a rat model of absence seizures51, suggesting its involvement in neurotransmission. Although it is not known whether the effects of LA in brain are mediated by LA itself or its oxidized metabolites, LA-metabolites have been detected in brain tissue31, 52 and are known to activate pain-gating transient receptor potential vanilloid (TRPV) channels and inflammatory pathways in rodent spinal cord53 and hindpaw54, and to reduce retinal epithelial cell growth55. These studies suggest that LA metabolites are likely bioactive in brain. Understanding the conditions that increase the formation of LA-derived metabolites and whether they are bioactive in brain may inform on new pathways that could be targeted.

The present study tested the hypothesis that LA partakes in the response to ischemic brain injury through oxidized metabolites that regulate brain signaling. A targeted lipidomics approach involving liquid chromatography tandem mass-spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) was used to quantify 85 PUFA-derived oxylipins (listed in Supplementary Table 1) in cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum and brainstem of rats subjected to CO2 asphyxiation-induced ischemia or head-focused microwave (MW) fixation, which heat-denatures enzymes to halt brain lipid metabolism56, 57. These brain regions were chosen because they are particularly affected to varying degrees by hypoxic or ischemic insults58–65. The lipidomic method used herein, extensively covered LA, AA and DHA metabolites, to contrast the ischemia-induced response of LA metabolites to published data on the AA and DHA metabolites produced during ischemic injury. It also included metabolites derived from other minor fatty acids in brain, such as ALA, EPA and di-homo-gamma-linolenic acid (DGLA), an intermediate elongation-desaturation product of LA, because we intended to assess whether they also participate in the response to ischemic brain injury.

The effects of AA, AA-derived prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), LA and LA-derived 13-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid (13-HODE) on hippocampal paired-pulse facilitation (PPF), a marker of short-term plasticity66, were measured using extracellular recordings to test whether 13-HODE regulates neurotransmission in a manner comparable to PGE2, a well-studied lipid mediator involved in hippocampal signaling67–69. 13-HODE was tested upon finding that its concentration increased in cortex and brainstem following ischemia, and that it is the most abundant LA-metabolite detected in rat hippocampus. Extracellular recordings were measured from hippocampus because of its clearly-defined structural attributes and robust signals which enable accurate extracellular recordings and assessment of changes in neurotransmission. It is also vulnerable to the neurodegenerative effects of ischemic injury58–61.

Results

Ischemia induced global changes in oxylipin concentrations

Targeted LC-MS/MS analysis detected the presence of 53, 34, 43 and 37 oxylipins in cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum and brainstem, respectively. As shown in Table 1, the majority of oxylipins were present in cortex, and many that were not detected in MW-fixed control brains, were present upon ischemia.

Table 1.

Number of oxylipins detected in cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum and brainstem in the control (n = 7–9) and ischemic groups (n = 7–9 per group) relative to the total number of metabolites analyzed (in brackets).

| Cortex | Hippocampus | Cerebellum | Brainstem | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Ischemic | Control | Ischemic | Control | Ischemic | Control | Ischemic | |

| LA-derived metabolites | 11 (/12) | 11 (/12) | 6 (/12) | 8 (/12) | 9 (/12) | 9 (/12) | 7 (/12) | 9 (/12) |

| DGLA-derived metabolites | 2 (/3) | 2 (/3) | 0 (/3) | 2 (/3) | 0 (/3) | 2 (/3) | 0 (/3) | 2 (/3) |

| AA-derived metabolites | 8 (/34) | 27 (/34) | 4 (/34) | 17 (/34) | 5 (/34) | 21 (/34) | 6 (/34) | 17 (/34) |

| ALA-derived metabolites | 2 (/8) | 2 (/8) | 0 (/8) | 0 (/8) | 1 (/8) | 4 (/8) | 2 (/8) | 2 (/8) |

| EPA-derived metabolites | 2 (/16) | 2 (/16) | 0 (/16) | 1 (/16) | 1 (/16) | 1 (/16) | 0 (/16) | 1 (/16) |

| DHA-derived metabolites | 5 (/12) | 9 (/12) | 6 (/12) | 6 (/12) | 5 (/12) | 6 (/12) | 6 (/12) | 6 (/12) |

| Total metabolites | 30 (/85) | 53 (/85) | 16 (/85) | 34 (/85) | 21 (/85) | 43 (/85) | 21 (/85) | 37 (/85) |

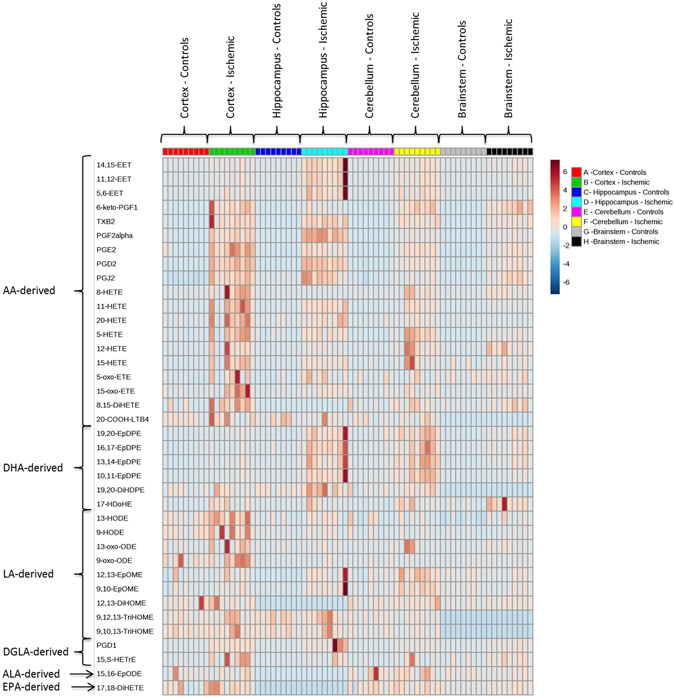

A heat map depicting the oxylipins common to all 4 brain regions in control and ischemic brains is shown in Fig. 1. As indicated, many LA, AA and DHA metabolites were abundant in all brain regions at baseline, and increased markedly following ischemia. Interestingly, although LA itself is low in brain compared to AA and DHA28, its metabolites were abundant.

Figure 1.

Heat map of oxylipin concentrations in cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum and brainstem in control and ischemic rats. EET, epoxyeicosatrienoic acid; PG, prostaglandin; TXB2, Tromboxane B2; HETE, hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; oxo-ETE, oxo-eicosatetraenoic acid; DiHETE, dihydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; LTB4, leukotriene B4; EpDPE, epoxydocosapentaenoic acid; DiHDPE, dihydroxydocosapentaenoic acid; HDoHE, hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid; HODE, hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid; oxo-ODE, oxo-octadecadienoic acid; EpOME, epoxyoctadecamonoenoic acid; diHOME, dihydroxyoctadecamonoenoic acid; TriHOME, trihydroxyoctadecamonoenoic acid; EpODE, epoxyoctadecadienoic acid; HETrE, hydroxyeicosatrienoic acid.

Ischemia increased LA-derived metabolites in various brain regions

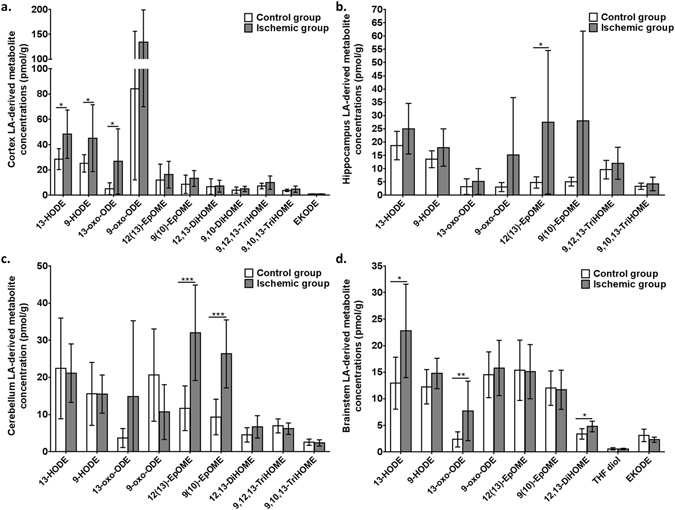

LA-derived oxylipins were significantly increased in various brain regions following ischemia compared to MW-fixed controls (Fig. 2). 13-HODE was 1.7-fold higher in the ischemic CO2-group compared to MW-fixed controls in cortex (p = 0.0115) and brainstem (p = 0.0098). 9-HODE was also increased in cortex by 1.8-fold in the ischemic CO2-group compared to MW-fixed controls (p = 0.0439). 13-oxo-ODE was increased by 5.6-fold in cortex (p = 0.0499) and by 3.2-fold in brainstem (p = 0.0134). 12(13)-EpOME was increased in both hippocampus (5.7-fold; p = 0.023) and cerebellum (2.7; p < 0.001), whereas 9(10)-EpOME was increased 2.8-fold in cerebellum (p < 0.001) of ischemic rats compared to MW-fixed controls. Brainstem concentrations of 12,13-DiHOME increased by 1.4-fold (p = 0.0088), following CO2-induced ischemia.

Figure 2.

Cortex (a), hippocampus (b), cerebellum (c) and brainstem (d) linoleic acid (LA)-derived metabolite concentrations (in pmol/g) in microwave (MW) control and ischemic rats (CO2; n = 7–9 per group). Values are mean ± standard deviation (SD). Significant differences were assessed using an unpaired t-test (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001). HODE, hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid; oxo-ODE, oxo-octadecadienoic acid; EpOME, epoxyoctadecamonoenoic acid; DiHOME, dihydroxyoctadecamonoenoic acid; TriHOME, trihydroxyoctadecamonoenoic acid; THF, tetrahydrofuran; EKODE, epoxyketooctadecadienoic acid.

Ischemia increased AA-derived metabolites in various brain regions

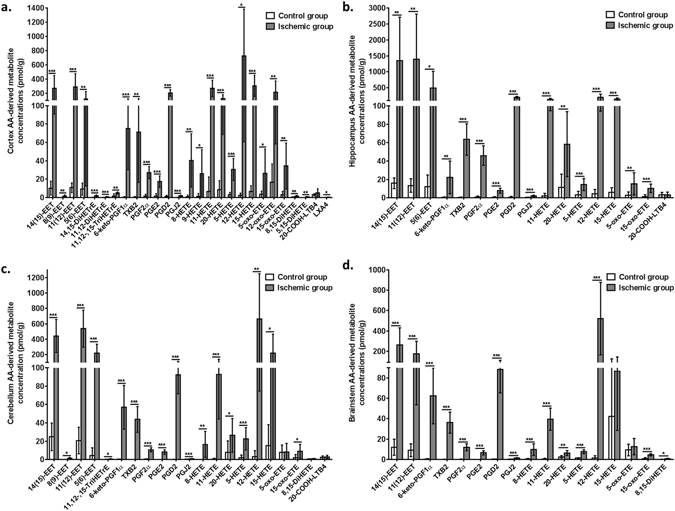

Previous studies reported an increase in the formation of AA- and DHA- derived oxylipins following hypoxia or ischemic brain injury41, 49. To confirm that these changes occurred in the present study, regional changes in AA- and DHA- derived metabolites were measured by LC-MS/MS as shown in Figs 3 and 4, respectively.

Figure 3.

Cortex (a), hippocampus (b), cerebellum (c) and brainstem (d) arachidonic acid (AA)-derived metabolite concentrations (in pmol/g) in microwave (MW) control and ischemic rats (CO2; n = 7–9 per group). Values are mean ± standard deviation (SD). Significant differences were assessed using an unpaired t-test (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001). EET, epoxyeicosatrienoic acid; DiHETrE, dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acid; TriHETrE, trihydroxyeicosatrienoic acid; PG, prostaglandin; TXB2, thromboxane B2; HETE, hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; oxo-ETE, oxo-eicosatetraenoic acid; DiHETE, dihydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; LTB4, leukotriene B4; LXA4, lipoxins A4.

Figure 4.

Cortex (a), hippocampus (b), cerebellum (c) and brainstem (d) docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)-derived metabolite concentrations (in pmol/g) in microwave (MW) control and ischemic rats (CO2; n = 7–9 per group). Values are mean ± standard deviation (SD). Significant differences were assessed using an unpaired t-test (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001). EpDPE, epoxydocosapentaenoic acid; DiHDPE, dihydroxydocosapentaenoic acid; HDoHE, hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid.

Compared to the MW-fixed controls, AA-derived epoxy-metabolites, 14(15)-EET, 11(12)-EET and 5(6)-EET, were increased in cortex (13 to 55-fold; p < 0.01), hippocampus (41 to 104-fold; p < 0.05), cerebellum (18 to 52-fold; p < 0.05) and brainstem (19 to 22-fold; p < 0.001) of the ischemic CO2-group. Mono-hydroxylated AA-derived metabolites, 5-, 11-, 12-, 15- and 20-HETE, were increased in cortex (10 to 345-fold; p < 0.05), hippocampus (4 to 67-fold; p < 0.01), cerebellum (3 to 204-fold; p < 0.05) and brainstem (2.5 to 372-fold; p < 0.001), following ischemia. 15-oxo-ETE, an AA-derived ketone, was increased by 11-fold in cortex (p = 0.0067), 7.4-fold in hippocampus (p < 0.0001), 4.7-fold in cerebellum (p = 0.03) and 5.2-fold in brainstem (p < 0.0001), while 5-oxo-ETE was increased by 7.9-fold in cortex (p = 0.039) and 5.3-fold in hippocampus (p = 0.0099), and 12-oxo-ETE by 12.9-fold in cortex (p = 0.0061) (Fig. 3).

Prostanoids (6-keto-PGF1α, PGF2α, PGE2, PGD2, PGJ2) were negligible or not detected in MW-fixed controls, but were present in the four brain regions of CO2-treated rats (p < 0.001). Ischemia also increased the cortical concentrations of epoxy- (8(9)-EpEtrE; p = 0.0048), monohydroxy- (8- and 9- HETE; p < 0.05), dihydroxy- (14,15- and 11,12-DiHETrE, p < 0.001; 8,15- and 5,15-DiHETE, p < 0.01) and trihydroxy- (11,12,15-TriHETrE; p = 0.0012) AA metabolites, which were not detected in MW-fixed controls (Fig. 3).

Ischemia increased DHA-derived metabolites in various brain regions

DHA-derived epoxy-metabolites (19(20)-, 16(17)-, 13(14)-, 10(11)- and 7(8)-EpDPE) were higher in cortex (3.9 to 7.3-fold; p < 0.01), hippocampus (9 to 12.7-fold; p < 0.01), cerebellum (4.8 to 7.9-fold; p < 0.01) and brainstem (6.6 to 9.4-fold; p < 0.01) of ischemic rats compared to MW-fixed controls (Fig. 4). 17-HDoHE was detected in cortex and cerebellum (p < 0.01) of ischemic CO2-treated rats but not MW-fixed controls, and was 8.1- and 7.4-fold higher in hippocampus (p = 0.025) and brainstem (p = 0.0072) of ischemic rats, respectively, relative to controls. Amongst the dihydroxy DHA metabolites analyzed, only 19,20-DiHDPE increased by 2-fold in hippocampus of the ischemic CO2-group compared to MW-fixed controls (p = 0.021).

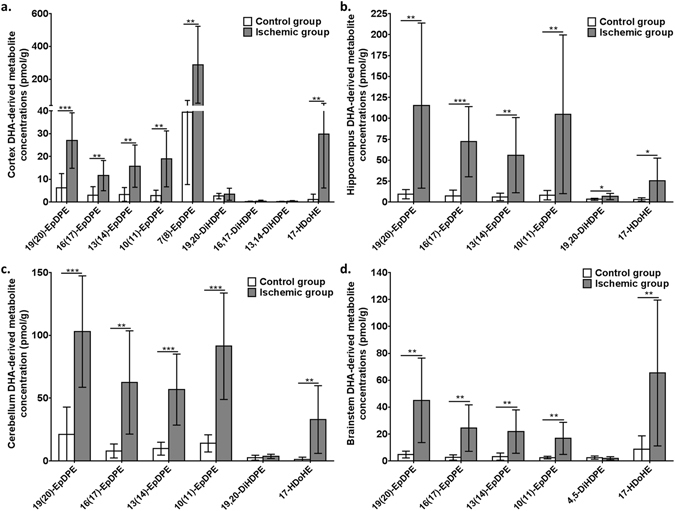

Other fatty acid metabolites found in relatively low concentrations in control brains were increased following ischemia

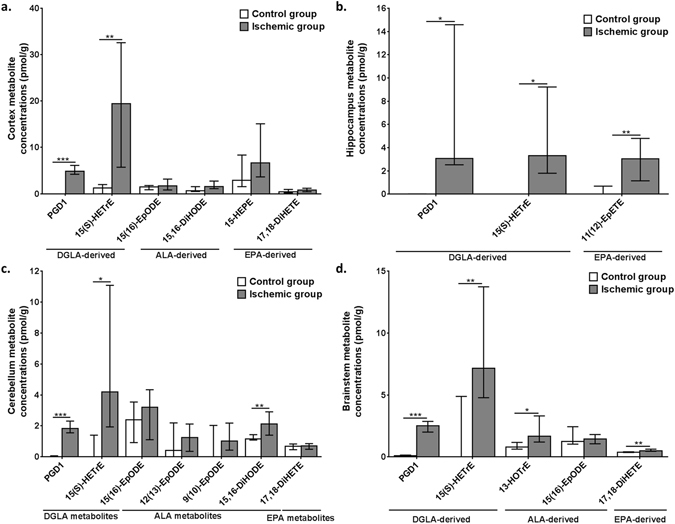

The concentrations of DGLA, ALA and EPA-derived metabolites within the different brain regions were low and only few of them were detected (Fig. 5). DGLA-derived PGD1 and 15(S)-HETrE, were present in all brain regions of the ischemic CO2-group but were absent or negligible in the MW-fixed group (p < 0.01). ALA-derived 15,16-DiHODE was 2.3 and 1.9 times higher in cortex (p = 0.0314) and cerebellum (p = 0.0028) of ischemic CO2-rats relative to MW-fixed controls, respectively. ALA-derived 13-HOTrE increased by 1.9 fold in brainstem (p = 0.0078). EPA-derived 11(12)-EpETE was detected in hippocampus following ischemia, but not in controls. Other detected EPA-derived metabolites did not significantly differ between the groups.

Figure 5.

Cortex (a), hippocampus (b), cerebellum (c) and brainstem (d) di-homo-gamma-linolenic acid (DGLA)-, α-linolenic acid (ALA)- and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA)-derived metabolite concentrations (in pmol/g) in microwave (MW) control and ischemic rats (CO2; n = 7–9 per group). Values are mean ± standard deviation (SD). Significant differences were assessed using an unpaired t-test (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001). PG, prostaglandin; HETrE, hydroxyeicosatrienoic acid; EpODE, epoxyoctadecadienoic acid; DiHODE, dihydroxyoctadecadienoic acid; HEPE, hydroxyeicosapentaenoic acid; DiHETE, dihydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; EpETE, epoxyeicosatetraenoic acid; HOTrE, hydroxyoctadecatrienoic acid.

13-HODE and PGE2, but not their fatty acid precursors, increased somatic PPF

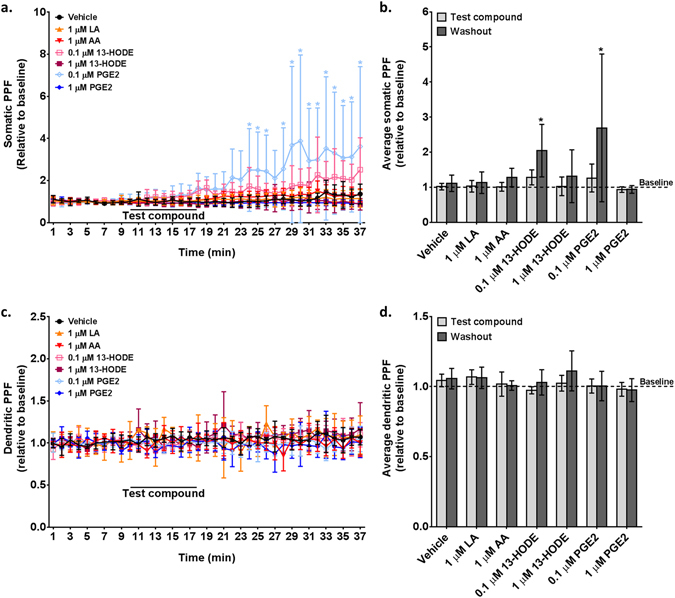

Hippocampal extracellular recordings were performed to test whether 13-HODE, the main LA metabolite detected in hippocampus (Fig. 2), altered neurotransmission in a manner comparable to its precursor, LA, and to AA and AA-derived PGE2.

Two-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect of time (p < 0.0001), and time-compound interaction (p < 0.0001) on the minute-by-minute PPF in soma. As indicated in Fig. 6a, compared to vehicle, 0.1 µM PGE2 significantly increased somatic PPF during the washout period (at 24, 25, 26 and after 28 minutes of recording; p < 0.05 by Dunnett’s post-hoc test). Mean somatic PPF was also significantly altered by time (p = 0.0003), compound (p = 0.0287) and time-compound interaction (p = 0.0121), as evidenced by the significant 1.8-fold and 2.4-fold increase in somatic PPF by 0.1 µM 13-HODE (p = 0.0296) and 0.1 µM PGE2 (p < 0.0001) during the washout period (Fig. 6b). No significant effects of time or treatment were observed in dendritic PPF (Fig. 6c and 6d).

Figure 6.

Somatic (a and b) and dendritic (c and d) Paired-Pulse Facilitation (PPF) measured on hippocampal slices perfused with vehicle (artificial cerebrospinal fluid containing 0.1% ethanol), 1 µM linoleic acid (LA), 1 µM arachidonic acid (AA), 0.1 µM or 1 µM 13-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid (13-HODE), or 0.1 µM or 1 µM prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). Data (mean ± SD) are expressed relative to baseline (n = 4–6 per condition). Graphs (a and c) showe the minute-by-minute data; (b and d) represent average PPF during compound incubation and washout relative to baseline (dotted line). Data were analyzed by a two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. *Significantly different compared to vehicle at a specific time point.

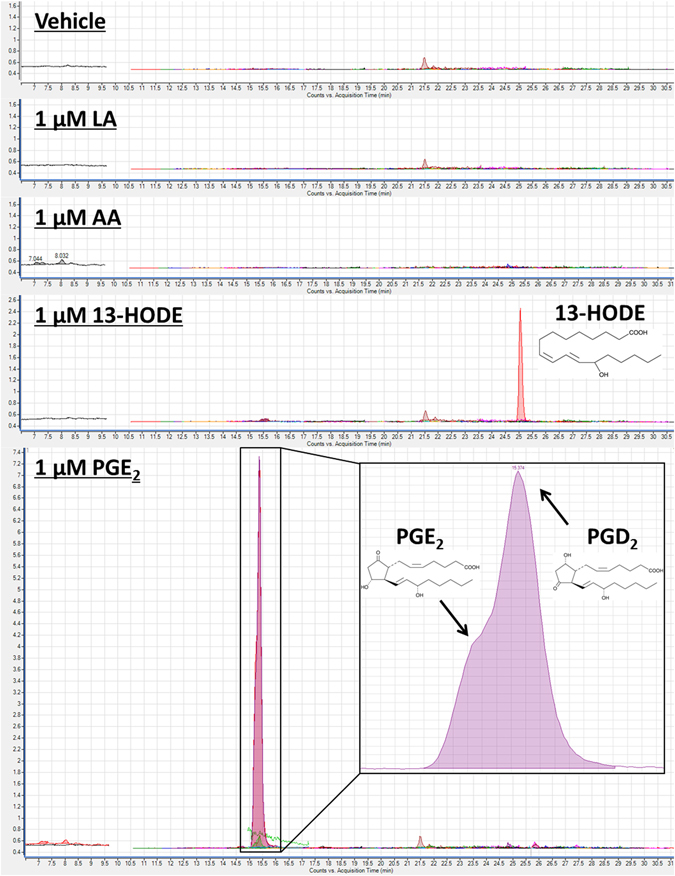

Gas-chromatography analysis confirmed the purity of LA and AA stock solutions to be 96.6% and 91.7%, respectively. AA contained a small amount of palmitic acid (C16:0; 1.3%), oleic acid (C18:1 n-9; 1.0%) and LA (0.3%). LC-MS/MS analysis showed that 13-HODE and PGE2 were 98–99% pure in the stock solution. LC-MS/MS analysis of artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) aliquots obtained at the end of the 10-minute perfusion was also performed to test whether the fatty acids or oxylipins were degraded during their incubation in ACSF at 37 °C under constant bubbling of 95% oxygen. As shown in Fig. 7, AA and LA did not degrade into any of the measured oxylipins, although this does not preclude the possibility of degradation into other compounds not covered by our lipidomic assay such as AA-derived F2-isoprostanes. ACSF aliquots of 13-HODE were >99% pure. PGE2, however, contained 20% PGE2 and 78% PGD2, suggesting degradation of the PGE2 into PGD2 during the 10-minute perfusion period.

Figure 7.

Dynamic multiple reaction monitoring scan of oxidized fatty acids in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing vehicle, 1 µM linoleic acid (LA), 1 µM arachidonic acid (AA), 1 µM 13-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid (13-HODE), or 1 µM prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). The vehicle or compounds were incubated in ACSF at 37 °C for 10 min under constant bubbling of 95% O2. No contamination was observed in vehicle and ACSF containing LA and AA. ACSF containing 13-HODE was pure at >98%. ACSF containing PGE2 had 20% PGE2, 78% PGD2 and 2% unidentified impurities. As shown in the figure, PGE2 and PGD2 peaks eluted at the same time.

Discussion

Here, we provide new evidence that LA is involved in the response to ischemia-induced brain injury and the regulation of neurotransmission through its oxidized metabolites. Ischemia increased cortex, cerebellum, hippocampus and brainstem LA-derived oxylipin concentrations, of which 13-HODE was tested and found to increase somatic PPF in hippocampus similar to AA-derived PGE2. The results suggest that during ischemic brain injury, the brain actively produces LA-metabolites that regulate neuronal signaling.

The present study confirmed previous reports of increased AA-derived prostaglandins (in particular PGE2 and PGD2), thromboxane B2 and lipoxygenase products (HETE, oxo-ETE and leukotrienes)41, 46, 47, 56, 70, and increased DHA-derived 17-HDoHE41, 49 in hippocampus or whole brain of rodents subjected to hypoxic or ischemic brain injury. By incorporating an expanded AA and DHA oxylipin panel in our LC-MS/MS platform, we also found an increase in epoxidized metabolites of AA and DHA following ischemia in cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum and brainstem. Because AA- and DHA-derived epoxides are anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective71–74, their increase following ischemia likely represents an adaptive response to prevent ischemia-related brain injury.

The parallel increase in LA metabolites in cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum and brainstem suggests that LA oxidized products are also involved in the response to ischemic brain injury, consistent with one study that reported increased 9- and 13-HODE in cortex of dogs subjected to 10-minutes of ischemic cardiac arrest75. CYP-derived LA epoxides (9(10)- and 12(13)-EpOME) were increased in hippocampus and cerebellum, two brain regions sensitive to hypoxic and ischemic insults58–61, whereas LOX-derived 9- and 13-HODE and oxo-ODE were increased in cortex and the brainstem. This reflects the selective synthesis of LA-derived species that likely play diverse roles during ischemia.

Many oxylipins produced following brain injury (prostanoids or epoxides) are known to regulate neurotransmission coupled to physiological processes that promote vasodilation or reduce excitotoxicity48, 49, 76. In the present study, we tested whether LA-derived 13-HODE also regulated neurotransmission. 13-HODE at 0.1 µM increased somatic but not dendritic paired-pulse facilitation in hippocampus, suggesting its involvement in regulating post-synaptic transmission and consistent with the somato-dendritic localization of COX and LOX enzymes that rapidly synthesize it77. 13-HODE was found to block phospholipase C-induced activation of protein kinase C78, a key regulator of short-term plasticity79. The mechanism of action of 13-HODE may involve a G-protein coupled receptor, such as the G2A receptor which binds oxidized fatty acid metabolites80. Identifying the specific G-protein receptor(s) that selectively binds 13-HODE in future studies might elucidate the mechanisms by which 13-HODE regulates neurotransmission in response to ischemic brain injury. Confirming that 13-HODE also regulates neurotransmission in cortex and brainstem, two brain regions were 13-HODE increased during ischemia, will inform on whether 13-HODE acts globally or on specific brain regions.

13-HODE and PGE2 increased somatic PPF at 0.1 µM but not 1 µM. The 0.1 µM dose of 13-HODE and PGE2 is consistent with the amount found in brain (based on measured concentrations in Figs 2 and 3 corrected for brain density), thus being physiologically relevant. Hippocampal dendritic PPF was reported to decrease by 5 µM67, 68 or remain unchanged by 0.5 µM81 or 10 µM69 PGE2, respectively. We are not aware of studies that specifically explored the effects of PGE2 on somatic transmission. However, by quantifying PGE2 (and 13-HODE) in hippocampus, this study demonstrated the signaling effects of both compounds at physiologically relevant concentrations and showed that higher doses were ineffective. Unesterified LA and AA did not alter PPF when applied at a physiologically relevant concentration of 1 µM82, suggesting that their signaling effects in brain are likely mediated by their metabolites.

Approximately 78% of the PGE2 was converted to PGD2 in the ACSF chamber, before reaching the slice. This means that the observed changes in hippocampal PPF in this study and possibly others67–69 could be mediated by PGD2. Little is known about the role of PGD2 on hippocampal neurotransmission. Chen et al. reported that 0.33 µM PGD2 did not alter postsynaptic excitability and induction of long-term potentiation in the presence of a COX-2 inhibitor, suggesting it likely has limited effects on neuronal excitability83.

Regional increases in brain EPA-derived 11,12-EpETE and 17,18-diHETE, ALA-derived 13-HoTrE and DGLA-derived PGD1 and 15(S)-HETrE were also seen following ischemia. DGLA-, ALA- and EPA- derived metabolites have been reported to reduce inflammation in vitro and in vivo 84–87, although their role in regulating neurotransmission or the response to brain injury is not known. The observed increase in their concentrations following ischemia highlights the need to explore their neurophysiological role and bioactivity in future studies.

In summary, this study showed that LA participates in the response to ischemic brain injury through metabolites that also regulate neurotransmission. Targeting this pathway using low LA diets8, 31 or novel drugs may be therapeutically useful for ischemia-related conditions such as stroke or hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy of newborn infants.

Methods

Animals

All procedures were performed in agreement with the policies of the Canadian Council on Animal Care and were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the University of Toronto and University Health Network. Thirty to thirty-four day old male rats were purchased from Charles River (Saint-Constant, QC, Canada). Upon their arrival, rats were housed in pairs and fed for 30 days with a Harlan Teklad 2018 diet containing 18.6% protein, 6.2% fat, 58.9% carbohydrate, 3.5% crude fiber and 5.3% ash and 7.5% moisture. The diet contained (% of total fatty acids), 18.5% palmitic acid (16:0), 2.8% stearic acid (18:0), 18.5% oleic acid (18:1 n-9), 54.8% LA and 5.6% ALA88.

Rat tissue collection

Rats were subjected to head-focused microwave (13.5 kW for 1.6 s; MW-fixed control group; n = 9) or CO2 asphyxiation for 2 min (CO2-group; n = 9)89. Brains were rapidly removed following head decapitation and separated into cortex, cerebellum, hippocampus and brainstem on ice. The use of CO2 causes hypercapnia, which is followed by decapitation-induced ischemia. The effects of hypercapnia on measured oxylipins are minimal compared to that of ischemia, which is why the effects reported in this study will be linked to ischemia rather than the combined effect of hypercapnia and ischemia89. Samples were stored at −80 °C for approximately one month until they were shipped on dry ice from Toronto, ON, Canada to Davis, CA, USA, where they were stored in a −80 °C freezer until use.

Oxylipin extraction by solid phase extraction (SPE)

Oxylipins were extracted from the different cerebral regions by solid phase extraction (SPE), as previously described31, 90, 91. Two to four hundred µL of ice-cold extraction solvent (0.1% acetic acid and 0.1% butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) in methanol) was added to frozen cortex (average weight >200 mg; 400 µL of extraction solvent), hippocampus, cerebellum and brainstem (weight <200 mg; 200 µL of extraction solvent), followed by the addition of 10 µL of antioxidant mix and 10–20 µL surrogate standard solution. The antioxidant solution containing 0.2 mg/mL of BHT, triphenylphosphine (TPP) and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) in methanol/water (50/50, v/v) was filtered through a Millipore filter (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) prior to use. The surrogate standard solution contained 500 nM of d11–11(12)-EpETrE, d11-14,15-DiHETrE, d4-6-keto-PGF1α, d4-9-HODE, d4-LTB4, d4-PGE2, d4-TXB2, d6-20-HETE and d8-5-HETE in methanol, and was added at an amount of 5–10 pmol per sample.

Frozen pre-weighed samples were homogenized for 5 to 10 min at 30 vibrations per second with a bead homogenizer. After storage overnight in a −80 °C freezer, samples were centrifuged at 13,200 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. Two hundred µL of supernatant were added to a 60 mg Waters Oasis HLB 3cc cartridges (Waters, Milford, MA, USA), pre-rinsed with one volume of ethyl acetate and two volumes of methanol, and pre-conditioned with two volumes of SPE buffer containing 5% methanol and 0.1% acetic acid in ultrapure water. The columns were rinsed twice with SPE buffer and dried under vacuum (≈20 psi) for 20 min. Oxylipins were eluted with 0.5 mL methanol and 1.5 mL ethyl acetate into a 2 mL centrifuge tube containing 6 µL of glycerol in methanol (30%).

Samples were dried in a Speed-Vac®, reconstituted in 50 µL methanol containing 200 nM 1-cyclohexyl ureido, 3-dodecanoic acid (CUDA) as a recovery standard and filtered by centrifugation using Ultrafree-MC-VV polyvinylidene fluoride filters (0.1 µm; Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA).

Oxylipin analysis by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

The PUFA-derived oxylipin analytical platform included 85 oxylipins (Supplementary Table 1) derived from omega-6 LA, LA’s elongation-desaturation products DGLA and AA, and omega-3 ALA, EPA and DHA. Oxylipins were analyzed by ultra-high pressure liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry UPLC-MS/MS as previously described90, 92 on an Agilent 1200SL (Agilent Corporation, Palo Alto, CA, USA) UPLC system connected to a 4000 QTRAP tandem mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems Instrument Corporation, Foster, CA, USA) equipped with an electrospray ion source (Turbo V). Oxylipins were separated on an Agilent 2.1 × 150 mm Eclipse Plus C18 column with a 1.8 µm particle size. Standards obtained from Larodan (Solna, Sweden), Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) or synthesized by Dr. Hammock’s laboratory were used for calibration curves for each oxylipin.

The autosampler temperature was kept at 4 °C and the column at 50 °C. The mobile phase A contained 0.1% acetic acid in ultrapure water and the mobile phase B contained acetonitrile/methanol /acetic acid (84/16/0.1). Gradient elution was performed at a flow rate of 0.25 mL/min for a total run time of 21 min as follows: solvent B was held at 35% for 0.25 min, increased to 45% from 0.25 to 1 min, to 55% B from 1 to 3 min, to 65% B from 3 to 8.5 min, to 72% from 8.5 to 12.5 min, to 82% B from 12.5 to 15 min, to 95% B from 15 to 16.5 min, held at 95% for 1.5 min, decreased to 35% from 18 to 18.1 min and held at 35% for 2.9 min. The instrument was operated in negative electrospray ionization mode and used optimized multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) conditions of the parent and fragmentation product ion to target each oxylipin90. Peaks were quantified according to the standard curves and corrected for the surrogate standard recovery using Analyst software 1.4.2.

The limit of quantification (LOQ) was set to three times the lowest standard concentration used in the standard curve. Oxylipins with >30% of values below the LOQ were excluded from the statistical analysis.

Preparation of the artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) solutions

A low Na+/Ca2 + ACSF containing 50 mM NaCl, 160 mM sucrose, 3.5 mM KCl, 2 mM NaH2PO4, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, 7 mM glucose and 5 mM HEPES (pH adjusted to 7.4) was prepared and used during intracardial perfusion and the slice preparation to limit excitotoxicity. A standard ACSF containing 3.5 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 125 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM glucose, 2 mM CaCl2 and 1.3 mM MgSO4 (pH 7.4 when aerated with 95% O2−5% CO2) was used during the hippocampal slice perfusion and electrophysiology recordings.

Slice preparation

Experiments were performed on 400-µm-thick hippocampal slices from 62- to 74-d-old male Long Evans rats (Charles River Laboratory, Quebec, Canada). Rats were euthanized with a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital (70 mg/kg) and intracardially perfused with cold low Na+/Ca2 + ASCF. After decapitation, the brain was rapidly removed and maintained in ice-cold oxygenated (95% O2−5% CO2) low Na+/Ca2 + ACSF for a few minutes. The brain was hemi-sectioned and the hippocampus isolated and glued onto an aluminum block. Four hundred-µm-thick transverse hippocampal slices were obtained using a vibratome and then placed in the standard ACSF at room temperature for at least 1 hour before recordings.

Extracellular recordings

Extracellular recordings were used to test the isolated effect of each compound on paired-pulse facilitation. Extracellular recordings were obtained from 4 to 6 slices per fatty acid or oxylipin treatment. Slices were transferred to a submerged recording chamber and continuously perfused with warm (37 °C) oxygenated (95% O2−5% CO2) standard ACSF at a flow rate of 10 mL/min. All recordings were done at a perfusate temperature of 37 °C. The Schaeffer collateral pathway was stimulated electrically with a bipolar stimulating electrode (polyamide-insulated stainless steel wires; outer diameter 100 μm; Plastics One, Ranoake, VA) placed in the stratum radiatum at the CA1-CA2 border. Recording electrodes were made from thin wall glass tubes (OD 1.5 mm; ID 1.12 mm; World precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) filled with ACSF and placed in the stratum pyramidale (soma) and stratum radiatum (dendrite) of the CA1 region. Constant-current pulses (duration of 0.1 ms each, intensities of 10–150 μA) were generated by a Grass stimulator (model S88, Grass Medical Instruments, Warwick, RI, USA) and delivered through an isolation unit. Extracellular signals were recorded using a dual channel amplifier (700B) and digitized using an analog-digital converter (Digidata 1400, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Data acquisition, storage and analysis were done using the pCLAMP software (version 10.5, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

To examine paired-pulse facilitation (PPF), twin stimuli (intensity range: 10–100 μA) were delivered with an interpulse interval of 35 ms. Representative recordings are shown in Supplementary Figure 1. Paired-stimuli were delivered every 10 s. Baseline recordings were measured for at least 10 min, followed by compound delivery for 8–15 min and finally, a washout period of at least 19 min (n = 4–6 per condition). The somatic amplitudes and dendritic field postsynaptic potential slopes were measured. PPF was calculated every minute by taking the ratio of the second response to the first response.

Compounds

13-HODE and PGE2 were purchased from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA). LA and AA were purchase from Nuchek Prep, Inc. (Elysian, MN, USA). The different drugs were dissolved in ethanol (stock concentration at 1 mM or 0.1 mM) and diluted 1000 times in ACSF to 1 µM LA, 1 µM AA, 0.1 µM or 1 µM 13-HODE, and 0.1 µM or 1 µM PGE2. Vehicle was made by diluting 100 µL of pure ethanol per 100 mL ACSF. The final ethanol concentration for vehicle or compounds was kept at or below 0.1%. The fatty acid precursors, LA and AA, were tested at 1 µM to mimic physiological conditions, because brain unesterified LA and AA concentrations in rodents range between 1–3 nmol/g28, which corresponds to 0.96–2.88 µM, based on a rat brain density of 1.04–1.05 g/mL93.

In an exploratory manner, we also tested the effects of AA-derived 14(15)-EET synthetized to 99% purity, at 1 µM and of LA-derived 9-oxo-ODE at 0.1 µM (Cayman Chemicals). We had intended to test lower concentrations of 14(15)-EET, but by testing the dose of 1 µM, we ran out of the compound and were not able to perform tests at 0.1 µM. Pilot data related to the effects of 14(15)-EET on PPF are provided in Supplementary Figure 2. As shown, 14,15-EET significantly reduced dendritic PPF during the washout period. The 9-oxo-ODE data were not included because LC-MS/MS analysis revealed that the stock solution was impure and contained 80% 9-oxo-ODE, 11% 5,6-DiHETrE and 9% EPA. Regardless, no significant changes in somatic or dendritic PPF were observed with 9-oxo-ODE.

The purity of the stock LA and AA was determined by gas-chromatography (GC), whereas that of 13-HODE, PGE2 and 14,15-EET was measured by LC-MS/MS. An 1 ml aliquot of ACSF containing the metabolites was obtained at the end of the 10-minute perfusion to determine whether the compounds were modified by being maintained at 37 °C in oxygenated ACSF (95% O2−5% CO2 for 10 minutes). The purity of the compounds was measured on an Agilent 1290 Infinity UHPLC system coupled to a 6460 triple-quadrupole tandem mass spectrometer with electrospray ionization (Agilent Corporation, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The system used optimized multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) conditions and was operated in negative electrospray ionization mode. Oxylipins were separated on an Agilent Eclipse Plus C-18 reverse-phase column (2.1 × 150 mm, 1.8 µm particle size). The auto-sampler temperature was kept at 4 °C and the column at 45 °C. Mobile phase A contained ultrapure water with 0.1% acetic acid. Mobile phase B contained acetonitrile/methanol (80/15 v/v) with 0.1% acetic acid. The flow rate started at 0.3 mL/min, decreased to 0.2 mL/min between 6 and 6.1 min, held at 0.2 mL/min for 24.4 min, increased to 0.35 mL/min between 30.5 and 30.6 min, held at 0.35 mL/min for 2.1 min, and decreased to 0.3 mL/min between 32.7 and 34 min. The following elution gradient was applied: mobile phase B was held at 40% for 6.1 min, increased to 80% from 6.1 to 20 min, increased to 82% from 20 to 30 min, increased to 99% from 30.5 to 30.6 min, held at 99% for 2 min, decreased to 40% between 32.6 and 32.7 min and held at 40% for 1.3 min. Peaks were analyzed using Agilent Mass Hunter Workstation Software Quantitative Analysis for QQQ (Version B.07.00). The oxylipin panel assayed included 72 available compounds from Cayman Chemicals and Larodan. The panel included all compounds listed in Supplementary Table 1, less the following: THF diols, EKODE, 15(16)-EpODE, 12(13)-EpODE, 9(10)-EpODE, 15,16-DiHODE, 12,13-DiHODE, 9,10-DiHODE, 19,20-DiHDPE, 16,17-DiHDPE, 13,14-DiHDPE, 10,11-DiHDPE, 7,8-DiHDPE, 4,5-DiHDPE, 11,12-DiHETE, 8,9-DiHETE, 11,12,15-TriHETrE and LTB5. It also included leukotrienes C4, D4 and E4.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Oxylipin extraction and analysis, as well as the analysis of extracellular recordings were performed by blinded individuals.

Differences between the CO2-group and MW-fixed controls were assessed using an unpaired t-test (GraphPad Prism 6.0, GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The final sample size per group was between 7 and 9, because the surrogate standard peak could not be accurately integrated for some of the samples. Heat maps were generated using MetaboAnalyst 3.094, 95.

Somatic and dendritic PPF were expressed relative to the average baseline per slice. Absolute PPF data are presented in Supplementary Table 2. The effect of time and test compound on the normalized somatic and dendridic PPF were evaluated with a two-way repeated measures ANOVA (GraphPad Prism 6.0, GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). When a significant interaction was found, Dunnett’s multiple comparison test was performed to evaluate for each time point the effect of the test compound compared to vehicle. The analysis was performed on the minute-by-minute data, as well as on the average data per period (baseline – compound – washout).

Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by UC Davis Food Science Department and College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences (A.Y.T.) and by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (grant #482597 to R.P.B., grant # RGPIN-2015-04153 to L.Z.) and Eplink Program for Ontario Brain Institute. R.P.B. holds a Canada Research Chair in Brain Lipid Metabolism. Partial support was provided by NIEHS R01 ES002710, Rapid Assays for Human and Environmental Exposure Assessment, and NIEHS Superfund Research Program P42 ES004699 (to B.D.H.). K.S.S.L. is partially supported by the N.I.H. Pathway to Independence Award (R00 ES024806). The authors thank Dr. Michael Leadley from the analytical Facility for Bioactive Molecules Research Institute at the Hospital for Sick Children (Toronto, ON, Canada) for running the assays confirming the purity of the stock standard solutions.

Author Contributions

A.Y.T., R.P.B. and L.Z. conceived the experiments. A.Y.T., A.M., A.K. and L.Z. conducted the experiments. M.H., Y.O. and C.E.R. performed the oxylipin extraction. M.H., Y.O., S.K.L. and J.Y. performed the LC-MS/MS analysis. J.Y. and B.D.H. developed the LC-MS/MS oxylipin method. S.K.L. synthetized and purified the 14,15-EET for electrophysiological recordings. M.H. analyzed the LC-MS/MS data. M.H. and Z.Z. performed the electrophysiology analysis. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-02914-7

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Blasbalg TL, Hibbeln JR, Ramsden CE, Majchrzak SF, Rawlings RR. Changes in consumption of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids in the United States during the 20th century. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:950–962. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.006643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis EF, Wei EP, Kontos HA. Vasodilation of cat cerebral arterioles by prostaglandins D2, E2, G2, and I2. Am J Physiol. 1979;237:H381–385. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1979.237.3.H381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oltman CL, Weintraub NL, VanRollins M, Dellsperger KC. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids and dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acids are potent vasodilators in the canine coronary microcirculation. Circ Res. 1998;83:932–939. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.83.9.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ye D, et al. Cytochrome p-450 epoxygenase metabolites of docosahexaenoate potently dilate coronary arterioles by activating large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303:768–776. doi: 10.1124/jpet.303.2.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inceoglu B, et al. Soluble epoxide hydrolase and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids modulate two distinct analgesic pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18901–18906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809765105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morisseau C, et al. Naturally occurring monoepoxides of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid are bioactive antihyperalgesic lipids. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:3481–3490. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M006007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hellstrom F, Gouveia-Figueira S, Nording ML, Bjorklund M, Fowler CJ. Association between plasma concentrations of linoleic acid-derived oxylipins and the perceived pain scores in an exploratory study in women with chronic neck pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:103. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-0951-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taha, A. Y. et al. Dietary Linoleic Acid Lowering Reduces Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Increase in Brain Arachidonic Acid Metabolism. Mol Neurobiol, doi:10.1007/s12035-016-9968-1 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Serhan CN, Chiang N, Van Dyke TE. Resolving inflammation: dual anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:349–361. doi: 10.1038/nri2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilroy DW, et al. CYP450-derived oxylipins mediate inflammatory resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E3240–3249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521453113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosviel, R. et al. DHA-derived oxylipins, neuroprostanes and protectins, differentially and dose-dependently modulate the inflammatory response in human macrophages: putative mechanisms through PPAR activation. Free Radic Biol Med, doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.12.018 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Gabbs M, Leng S, Devassy JG, Monirujjaman M, Aukema HM. Advances in Our Understanding of Oxylipins Derived from Dietary PUFAs. Advances in Nutrition. 2015;6:513–540. doi: 10.3945/an.114.007732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orr SK, et al. Unesterified docosahexaenoic acid is protective in neuroinflammation. J Neurochem. 2013;127:378–393. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang J, et al. 12/15 Lipoxygenase regulation of colorectal tumorigenesis is determined by the relative tumor levels of its metabolite 12-HETE and 13-HODE in animal models. Oncotarget. 2015;6:2879–2888. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Funk CD. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: advances in eicosanoid biology. Science. 2001;294:1871–1875. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5548.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy E, Glasgow W, Fralix T, Steenbergen C. Role of lipoxygenase metabolites in ischemic preconditioning. Circ Res. 1995;76:457–467. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.76.3.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laneuville O, et al. Fatty acid substrate specificities of human prostaglandin-endoperoxide H synthase-1 and -2. Formation of 12-hydroxy-(9Z, 13E/Z, 15Z)- octadecatrienoic acids from alpha-linolenic acid. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:19330–19336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.33.19330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blanchard HC, Taha AY, Rapoport SI, Yuan ZX. Low-dose aspirin (acetylsalicylate) prevents increases in brain PGE2, 15-epi-lipoxin A4 and 8-isoprostane concentrations in 9 month-old HIV-1 transgenic rats, a model for HIV-1 associated neurocognitive disorders. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2015;96:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fer M, et al. Cytochromes P450 from family 4 are the main omega hydroxylating enzymes in humans: CYP4F3B is the prominent player in PUFA metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:2379–2389. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800199-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Konkel A, Schunck WH. Role of cytochrome P450 enzymes in the bioactivation of polyunsaturated fatty acids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1814:210–222. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bylund J, Kunz T, Valmsen K, Oliw EH. Cytochromes P450 with bisallylic hydroxylation activity on arachidonic and linoleic acids studied with human recombinant enzymes and with human and rat liver microsomes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;284:51–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greene JF, Newman JW, Williamson KC, Hammock BD. Toxicity of epoxy fatty acids and related compounds to cells expressing human soluble epoxide hydrolase. Chem Res Toxicol. 2000;13:217–226. doi: 10.1021/tx990162c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strokin M, Sergeeva M, Reiser G. Role of Ca2+ -independent phospholipase A2 and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid in prostanoid production in brain: perspectives for protection in neuroinflammation. International journal of developmental neuroscience: the official journal of the International Society for Developmental Neuroscience. 2004;22:551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strokin M, Sergeeva M, Reiser G. Docosahexaenoic acid and arachidonic acid release in rat brain astrocytes is mediated by two separate isoforms of phospholipase A2 and is differently regulated by cyclic AMP and Ca2+ British journal of pharmacology. 2003;139:1014–1022. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts LJ, 2nd, et al. Formation of isoprostane-like compounds (neuroprostanes) in vivo from docosahexaenoic acid. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13605–13612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Musiek ES, Yin H, Milne GL, Morrow JD. Recent advances in the biochemistry and clinical relevance of the isoprostane pathway. Lipids. 2005;40:987–994. doi: 10.1007/s11745-005-1460-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minami Y, Yokoyama K, Bando N, Kawai Y, Terao J. Occurrence of singlet oxygen oxygenation of oleic acid and linoleic acid in the skin of live mice. Free Radic Res. 2008;42:197–204. doi: 10.1080/10715760801948088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taha AY, et al. Altered lipid concentrations of liver, heart and plasma but not brain in HIV-1 transgenic rats. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2012;87:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeMar JC, Jr., et al. Brain elongation of linoleic acid is a negligible source of the arachidonate in brain phospholipids of adult rats. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:1050–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen CT, Green JT, Orr SK, Bazinet RP. Regulation of brain polyunsaturated fatty acid uptake and turnover. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2008;79:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taha AY, et al. Regulation of rat plasma and cerebral cortex oxylipin concentrations with increasing levels of dietary linoleic acid. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Funk CD, Powell WS. Metabolism of linoleic acid by prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase from adult and fetal blood vessels. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983;754:57–71. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(83)90082-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reinaud O, Delaforge M, Boucher JL, Rocchiccioli F, Mansuy D. Oxidative metabolism of linoleic acid by human leukocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;161:883–891. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(89)92682-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bull AW, Earles SM, Bronstein JC. Metabolism of oxidized linoleic acid: distribution of activity for the enzymatic oxidation of 13-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid to 13-oxooctadecadienoic acid in rat tissues. Prostaglandins. 1991;41:43–50. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(91)90103-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arai K, et al. Phospholipase A2 mediates ischemic injury in the hippocampus: a regional difference of neuronal vulnerability. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:2319–2323. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lauritzen I, Heurteaux C, Lazdunski M. Expression of group II phospholipase A2 in rat brain after severe forebrain ischemia and in endotoxic shock. Brain Res. 1994;651:353–356. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90719-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edgar AD, Strosznajder J, Horrocks LA. Activation of ethanolamine phospholipase A2 in Brain during ischemia. J Neurochem. 1982;39:1111–1116. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1982.tb11503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bazan NG., Jr. Effects of ischemia and electroconvulsive shock on free fatty acid pool in the brain. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1970;218:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(70)90086-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rehncrona S, Westerberg E, Akesson B, Siesjo BK. Brain cortical fatty acids and phospholipids during and following complete and severe incomplete ischemia. J Neurochem. 1982;38:84–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1982.tb10857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deutsch J, Rapoport SI, Purdon AD. Relation between free fatty acid and acyl-CoA concentrations in rat brain following decapitation. Neurochem Res. 1997;22:759–765. doi: 10.1023/A:1022030306359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farias SE, et al. Formation of eicosanoids, E2/D2 isoprostanes, and docosanoids following decapitation-induced ischemia, measured in high-energy-microwaved rat brain. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:1990–2000. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800200-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramadan E, et al. Extracellular-derived calcium does not initiate in vivo neurotransmission involving docosahexaenoic acid. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:2334–2340. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M006262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhattacharjee AK, et al. Bilateral common carotid artery ligation transiently changes brain lipid metabolism in rats. Neurochem Res. 2012;37:1490–1498. doi: 10.1007/s11064-012-0740-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rabin O, et al. Selective acceleration of arachidonic acid reincorporation into brain membrane phospholipid following transient ischemia in awake gerbil. J Neurochem. 1998;70:325–334. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70010325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marcheselli VL, et al. Novel docosanoids inhibit brain ischemia-reperfusion-mediated leukocyte infiltration and pro-inflammatory gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:43807–43817. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305841200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bosisio E, et al. Correlation between release of free arachidonic acid and prostaglandin formation in brain cortex and cerebellum. Prostaglandins. 1976;11:773–781. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(76)90186-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Usui M, Asano T, Takakura K. Identification and quantitative analysis of hydroxy-eicosatetraenoic acids in rat brains exposed to regional ischemia. Stroke. 1987;18:490–494. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.18.2.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Inceoglu B, et al. Epoxy fatty acids and inhibition of the soluble epoxide hydrolase selectively modulate GABA mediated neurotransmission to delay onset of seizures. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80922. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamaura K, et al. Contribution of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids to the hypoxia-induced activation of Ca2+ -activated K+ channel current in cultured rat hippocampal astrocytes. Neuroscience. 2006;143:703–716. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Voskuyl RA, Vreugdenhil M, Kang JX, Leaf A. Anticonvulsant effect of polyunsaturated fatty acids in rats, using the cortical stimulation model. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;341:145–152. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(97)01467-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ekici F, Gurol G, Ates N. Effects of linoleic acid on generalized convulsive and nonconvulsive epileptic seizures. Turk J Med Sci. 2014;44:535–539. doi: 10.3906/sag-1305-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu W, et al. Ex vivo oxidation in tissue and plasma assays of hydroxyoctadecadienoates: Z,E/E,E stereoisomer ratios. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010;23:986–995. doi: 10.1021/tx1000943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patwardhan AM, Scotland PE, Akopian AN, Hargreaves KM. Activation of TRPV1 in the spinal cord by oxidized linoleic acid metabolites contributes to inflammatory hyperalgesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:18820–18824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905415106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alsalem M, et al. The contribution of the endogenous TRPV1 ligands 9-HODE and 13-HODE to nociceptive processing and their role in peripheral inflammatory pain mechanisms. British journal of pharmacology. 2013;168:1961–1974. doi: 10.1111/bph.12092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Akeo K, Hiramitsu T, Kanda T, Yorifuji H, Okisaka S. Comparative effects of linoleic acid and linoleic acid hydroperoxide on growth and morphology of bovine retinal pigment epithelial cells in vitro. Current eye research. 1996;15:467–476. doi: 10.3109/02713689609000758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Golovko MY, Murphy EJ. An improved LC-MS/MS procedure for brain prostanoid analysis using brain fixation with head-focused microwave irradiation and liquid-liquid extraction. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:893–902. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D700030-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Galli C, Racagni G. Use of microwave techniques to inactivate brain enzymes rapidly. Methods Enzymol. 1982;86:635–642. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(82)86234-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pae EK, Chien P, Harper RM. Intermittent hypoxia damages cerebellar cortex and deep nuclei. Neurosci Lett. 2005;375:123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.10.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cervos-Navarro J, Diemer NH. Selective vulnerability in brain hypoxia. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1991;6:149–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaur C, Sivakumar V, Zhang Y, Ling EA. Hypoxia-induced astrocytic reaction and increased vascular permeability in the rat cerebellum. Glia. 2006;54:826–839. doi: 10.1002/glia.20420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhao YD, et al. Dendritic development of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells in a neonatal hypoxia-ischemia injury model. J Neurosci Res. 2013;91:1165–1173. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Selakovic V, Korenic A, Radenovic L. Spatial and temporal patterns of oxidative stress in the brain of gerbils submitted to different duration of global cerebral ischemia. International journal of developmental neuroscience: the official journal of the International Society for Developmental Neuroscience. 2011;29:645–654. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee JC, et al. Neuronal damage and gliosis in the somatosensory cortex induced by various durations of transient cerebral ischemia in gerbils. Brain Res. 2013;1510:78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brisson CD, Hsieh YT, Kim D, Jin AY, Andrew RD. Brainstem neurons survive the identical ischemic stress that kills higher neurons: insight to the persistent vegetative state. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96585. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sieber, F. E., Palmon, S. C., Traystman, R. J. & Martin, L. J. Global incomplete cerebral ischemia produces predominantly cortical neuronal injury. Stroke26, 2091–2095, discussion 2096 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Zucker RS, Regehr WG. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:355–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.092501.114547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sang N, Zhang J, Marcheselli V, Bazan NG, Chen C. Postsynaptically synthesized prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) modulates hippocampal synaptic transmission via a presynaptic PGE2 EP2 receptor. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9858–9870. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2392-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang H, Zhang J, Breyer RM, Chen C. Altered hippocampal long-term synaptic plasticity in mice deficient in the PGE2 EP2 receptor. J Neurochem. 2009;108:295–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05766.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maingret V, et al. PGE2-EP3 signaling pathway impairs hippocampal presynaptic long-term plasticity in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of aging. 2016;50:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tegtmeier F, et al. Eicosanoids in rat brain during ischemia and reperfusion–correlation to DC depolarization. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1990;10:358–364. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1990.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Spector AA, Norris AW. Action of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids on cellular function. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C996–1012. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00402.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang L, et al. 14,15-EET promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and protects cortical neurons against oxygen/glucose deprivation-induced apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;450:604–609. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu Y, et al. Epoxyeicosanoid Signaling Provides Multi-target Protective Effects on Neurovascular Unit in Rats After Focal Ischemia. J Mol Neurosci. 2016;58:254–265. doi: 10.1007/s12031-015-0670-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Abdu E, et al. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids enhance axonal growth in primary sensory and cortical neuronal cell cultures. J Neurochem. 2011;117:632–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07139.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu Y, et al. Normoxic ventilation after cardiac arrest reduces oxidation of brain lipids and improves neurological outcome. Stroke. 1998;29:1679–1686. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.29.8.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cazevieille C, Muller A, Meynier F, Dutrait N, Bonne C. Protection by prostaglandins from glutamate toxicity in cortical neurons. Neurochemistry international. 1994;24:395–398. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(94)90118-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cristino L, et al. Immunohistochemical localization of anabolic and catabolic enzymes for anandamide and other putative endovanilloids in the hippocampus and cerebellar cortex of the mouse brain. Neuroscience. 2008;151:955–968. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liu B, et al. 12(S)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid and 13(S)-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid regulation of protein kinase C-alpha in melanoma cells: role of receptor-mediated hydrolysis of inositol phospholipids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9323–9327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.de Jong AP, et al. Phosphorylation of synaptotagmin-1 controls a post-priming step in PKC-dependent presynaptic plasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:5095–5100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522927113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Obinata H, Hattori T, Nakane S, Tatei K, Izumi T. Identification of 9-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid and other oxidized free fatty acids as ligands of the G protein-coupled receptor G2A. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40676–40683. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507787200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen C, Bazan NG. Endogenous PGE2 regulates membrane excitability and synaptic transmission in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:929–941. doi: 10.1152/jn.00696.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jang IS, Ito Y, Akaike N. Feed-forward facilitation of glutamate release by presynaptic GABA(A) receptors. Neuroscience. 2005;135:737–748. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen C, Magee JC, Bazan NG. Cyclooxygenase-2 regulates prostaglandin E2 signaling in hippocampal long-term synaptic plasticity. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:2851–2857. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.87.6.2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schulze-Tanzil G, et al. Effects of the antirheumatic remedy hox alpha–a new stinging nettle leaf extract–on matrix metalloproteinases in human chondrocytes in vitro. Histology and histopathology. 2002;17:477–485. doi: 10.14670/HH-17.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Iversen L, Fogh K, Bojesen G, Kragballe K. Linoleic acid and dihomogammalinolenic acid inhibit leukotriene B4 formation and stimulate the formation of their 15-lipoxygenase products by human neutrophils in vitro. Evidence of formation of antiinflammatory compounds. Agents Actions. 1991;33:286–291. doi: 10.1007/BF01986575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Morin C, Sirois M, Echave V, Albadine R, Rousseau E. 17,18-epoxyeicosatetraenoic acid targets PPARgamma and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase to mediate its anti-inflammatory effects in the lung: role of soluble epoxide hydrolase. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;43:564–575. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0155OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Xu, Z. Z. et al. Resolvins RvE1 and RvD1 attenuate inflammatory pain via central and peripheral actions. Nat Med16, 592–597, 591p following 597, doi:10.1038/nm.2123 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 88.Trepanier MO, et al. Increases in seizure latencies induced by subcutaneous docosahexaenoic acid are lost at higher doses. Epilepsy Res. 2012;99:225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Trepanier MO, Eiden M, Morin-Rivron D, Bazinet RP, Masoodi M. High-resolution lipidomics coupled with rapid fixation reveals novel ischemia-induced signaling in the rat neurolipidome. J Neurochem. 2017;140:766–775. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yang J, Schmelzer K, Georgi K, Hammock BD. Quantitative profiling method for oxylipin metabolome by liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2009;81:8085–8093. doi: 10.1021/ac901282n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schebb NH, et al. Comparison of the effects of long-chain omega-3 fatty acid supplementation on plasma levels of free and esterified oxylipins. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2014;113–115:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zivkovic AM, et al. Serum oxylipin profiles in IgA nephropathy patients reflect kidney functional alterations. Metabolomics. 2012;8:1102–1113. doi: 10.1007/s11306-012-0417-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.DiResta GR, et al. Measurement of brain tissue density using pycnometry. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 1990;51:34–36. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9115-6_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Xia J, Sinelnikov IV, Han B, Wishart DS. MetaboAnalyst 3.0–making metabolomics more meaningful. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W251–257. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Xia, J. & Wishart, D. S. Using MetaboAnalyst 3.0 for Comprehensive Metabolomics Data Analysis. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics55, 14 10 11–14 10 91, doi:10.1002/cpbi.11 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.