Abstract

Dopamine supersensitivity occurs in schizophrenia and other psychoses, and after hippocampal lesions, antipsychotics, ethanol, amphetamine, phencyclidine, gene knockouts of Dbh (dopamine β-hydroxylase), Drd4 receptors, Gprk6 (G protein-coupled receptor kinase 6), Comt (catechol-O-methyltransferase), or Th-/-, DbhTh/+ (tyrosine hydroxylase), and in rats born by Cesarean-section. The functional state of D2, or the high-affinity state for dopamine (D2High), was measured in these supersensitive animal brain striata. Increased levels and higher proportions (40-900%) for D2High were found in all these tissues. If many types of brain impairment cause dopamine behavioral supersensitivity and a common increase in D2High states, it suggests that there are many pathways to psychosis, any one of which can be disrupted.

Keywords: addiction, dopamine receptors, gene knockouts, schizophrenia

Psychotic symptoms occur in many diseases, including schizophrenia and prolonged drug abuse. Although many chromosome regions and genes have been found associated with schizophrenia (1, 2), no single gene of major effect has yet been identified. Nevertheless, regardless of the causes of psychosis, antipsychotic drugs are mostly effective in alleviating the symptoms. The clinical antipsychotic potencies of these drugs are directly related to their affinities for the dopamine D2 receptor (3, 4), suggesting that the properties of this receptor are disturbed in psychosis. It is uncertain whether the total density of D2 receptors in schizophrenia is elevated (5, 6). The more relevant question, however, is whether the functional state of D2, or the state of high-affinity for dopamine, D2High (7), is elevated, and this has not been investigated in schizophrenia or in any of the psychoses. An elevated density of D2High would explain why up to 70% of individuals with schizophrenia are supersensitive to dopamine (8), but supersensitivity may have other bases. Therefore, it is important to determine the causes of dopamine supersensitivity (i.e., behavioral supersensitivity to dopamine-mimetics). Experimentally, dopamine supersensitivity occurs after a neonatal hippocampal lesion (9), long-term antipsychotics (10), ethanol or amphetamine (11), in gene knockouts of Dbh (dopamine β-hydroxylase) (12), Drd4 dopamine receptors (13), Gprk6 (G protein-coupled receptor kinase 6) (14), Comt (catechol-O-methyltransferase) (15, 16), or Th-/-, DbhTh/+(tyrosine hydroxylase, dopamine-deficient) (17-19), and in rats born by Cesarean section (20). Although antipsychotics are known to elevate the density of dopamine D2 receptors by ≈25% above control levels, no such elevations occur in ethanol withdrawal (21), amphetamine-sensitized animals (22), Gprk6 or Comt knockouts (14, 15), dopamine deficient mice (18), or rats born by Cesarean-section (20).

The basis of supersensitivity to amphetamine or dopamine agonists thus remains puzzling. However, it has recently been found that, despite the absence of any elevation in total dopamine D2 receptors in the striata of amphetamine-sensitized animals, there is a dramatic 360% increase (22) in the density of D2High states (23). Therefore, we thought it important to examine whether D2High would also be invariably elevated in other conditions showing dopamine supersensitivity. We found this to be the case in studying the striata from many types of animals that are known to be dopamine supersensitive after treatment with either antipsychotics, quinpirole, ethanol, or amphetamine, after a hippocampal lesion, or after five types of gene knockouts.

Materials and Methods

Antipsychotic Treatment. Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats, weighing 200-225 g at the start of the experiment, were used. For 9 days, the animals received daily i.p. injections (0.5 ml) of saline (0.9%), haloperidol (0.045 mg/kg), risperidone (0.75 mg/kg), olanzapine (0.75 mg/kg), clozapine (35 mg/kg), or quetiapine (25 mg/kg). These doses occupy 70% of brain dopamine D2 receptors in rats, a level of occupancy associated with human clinical response to antipsychotics in schizophrenia (24). The nonantipsychotic ketanserin was used as a comparison drug and given i.p. at 15 mg/kg for 9 days.

Amphetamine Sensitization. The procedure for sensitizing rats to amphetamine has been published (22).

Ethanol Treatment and Withdrawal. Ethanol was given as follows: 2 g/kg i.p. twice daily; i.e., 1.4 ml of 18% ethanol in 0.9% NaCl per 100 g at 9 a.m. and again at 3 p.m. daily to rats for 10 days.

Hippocampal Lesion. The procedure for lesioning the rat hippocampus has been described (9).

Gene Knockouts (Homozygous). Gene knockouts for the Dbh gene (12) were developed in C57BL/6J × 129/SvEv mice. Knockouts for the Drd4 receptor gene (13) and the Gprk6 gene were developed in the C57BL/6J × 129/SvJ strain of mice. Comt-deficient male C57BL/6J mice and dopamine-deficient mice were generated and genotyped as described (15-19). The dopamine-deficient mice required daily L-DOPA (50 mg/kg i.p.) for survival (yet maintaining dopamine supersensitivity), and the animals were killed 24 h after the last dose of L-DOPA. Congenic mice lacking Drd1a (backcrossed to C57BL for 11 generations) were prepared (25).

Rats Born by Cesarean Section. The procedure for obtaining rats by cesarean section with or without anoxia are given elsewhere (20).

Quinpirole or Phencyclidine Sensitization. Adult rats received 13 doses of quinpirole (0.05 mg/kg), followed by six doses (0.5 mg/kg) s.c. twice weekly. After the series of injections, the rats had an enhanced locomotor response to quinpirole (up to 1 mg/kg). Rats were sensitized to phencyclidine (Sigma; 2.5 mg/kg/day i.p. for 4 days, followed by 7 days without drug).

[3H]Ligands. [3H]Raclopride (60-80 Ci/mmol) was from PerkinElmer Life Sciences (Boston). [3H]Domperidone was custom synthesized as [phenyl-3H(N)]domperidone (42 Ci/mmol) by PerkinElmer Life Sciences, and used at a final concentration of 1.2-3 nM for competition with dopamine.

Saturation of Dopamine D2 Receptors by [3H]Raclopride (Scatchard Analysis). The frozen striata were blotted and weighed frozen. Buffer was added (50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4/1 mM EDTA/5 mM KCl/1.5 mM CaCl2/4 mM MgCl2/120 mM NaCl) to yield 4 mg of tissue per ml. The method for determining the density of D2 receptors has been reported (21-23). Nonspecific binding for dopamine D2 receptors was defined as that in the presence of 10 μM S-sulpiride. The density of [3H]raclopride binding sites and the dissociation constant (Kd) were obtained by Scatchard analysis.

Competition Between Dopamine and [3H]Raclopride or [3H]Domperidone. The competition between dopamine and [3H]raclopride or [3H]domperidone for binding at the dopamine D2 receptors was done as reported (23).

Statistics. The competition data were analyzed by using a program that provided two statistical criteria to judge whether a two-site fit was better than a one-site fit, or whether a three-site fit was better than a two-site fit (ref. 21 and references therein).

Results

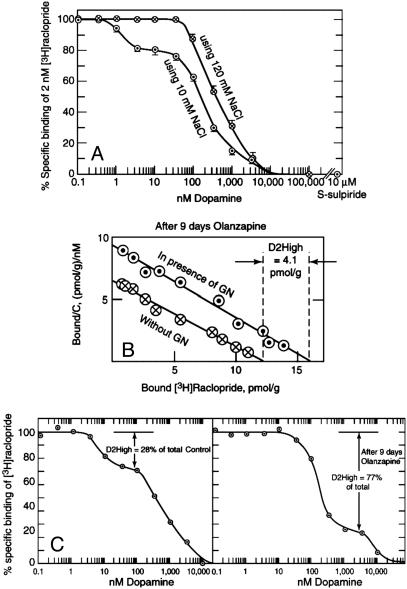

Long-Term Antipsychotic Treatment. Three methods were used to detect the D2High states in vitro. The first method was a dopamine/[3H]raclopride competition experiment in the presence of low NaCl (10 mM) (21, 22). The low NaCl was used because high-affinity states were not detected by dopamine/[3H]raclopride competition in 120 mM NaCl, as shown in Fig. 1A. A second method was to use dopamine/[3H]domperidone competition in 120 mM NaCl, because [3H]domperidone, unlike [3H]raclopride, readily detects D2High states in the presence of 120 mM NaCl (23). A third method to detect D2High states was to use [3H]raclopride saturation data, where the D2High states were defined as those made available by the presence of 200 μM guanilylimidodiphosphate (GN), as shown in Fig. 1B. In this example, the density of D2 receptors in the absence of GN was 12 pmol/g, whereas in the presence of GN, the density was 16.1 pmol/g. The extra binding sites made available by GN were presumably sites with high affinity for dopamine but occluded by endogenous dopamine and were effectively removed when the receptors were converted to their low-affinity states by GN.

Fig. 1.

Detection of D2High states. (A) Dopamine recognizes high-affinity states for dopamine D2 receptors when competing with 2 nM [3H]raclopride in the presence of 10 mM NaCl, but not in the presence of 120 mM NaCl. Rat homogenized striatum is shown. Average values ± SE (n = 3) are given. Nonspecific binding in the presence of 10 μM S-sulpiride is shown. (B)[3H]Raclopride saturation method for measuring D2High states after 9 days of olanzapine treatment. Using 120 mM NaCl, saturation of striatal dopamine D2 receptors with [3H]raclopride in the presence and absence of 200μM GN is shown. The increase in binding with GN reflects the high-affinity states of the dopamine D2 receptor, D2High.(C) Using 10 mM NaCl, the dopamine/[3H]raclopride competition method also revealed an increase in the proportion of D2High states after 9 days of olanzapine (Table 1).

Also shown in Fig. 1B is the typical effect of an antipsychotic, olanzapine, on the D2High states. Rats received daily injections of haloperidol, risperidone, olanzapine, clozapine, or quetiapine, using doses known to occupy ≈70% of brain striatum dopamine D2 receptors in rats, a level of occupancy associated with human clinical response to antipsychotics in schizophrenia (24). The nonantipsychotic ketanserin was used for comparison. Fig. 1B illustrates that olanzapine elevated the density of D2High states from a control value of 1.9 ± 0.2 pmol/g to 4.1 ± 0.6 pmol/g (Table 1), representing a 2-fold elevation. Furthermore, Fig. 1C shows that dopamine recognized 28% of the [3H]raclopride-labeled sites to be in the high-affinity state, and that this increased to 77% after 9 days of olanzapine treatment, an increase of 2.7-fold.

Table 1. Dopamine supersensitivity in striatum: Increased D2High receptors.

| Dopamine/[3H]raclopride

|

Dopamine/[3H]domperidone

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n* | D2 density, pmol/g (nM) | Total D2 density, pmol/g (nM)† | D2High, pmol/g† | Fold differential‡ | % D2High (n = 2),* % | Increase in D2High proportion | % D2High (n = 2),* % | Increase in D2High proportion | |

| Rat control striata | 34 | 19.8 ± 0.7 (1.4 ± 0.1) | 21.7 ± 0.7 (1.46 ± 0.1) | 1.94 ± 0.2 | Control | 10–28 | Control | 10–20 | Control |

| Ketanserin, 9 days | 2 | 13.4 ± 0.5 (1.8) | 15 ± 0.6 (1.8) | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 0.83-fold | 26 | Same as control | ND | ND |

| Haloperidol, 9 days | 2 | 15.8 ± 1.8 (1.1) | 20.5 ± 1.6 (1.3) | 4.7 ± 0.35 | 2.4-fold | 43 ± 5 | 1.9-fold | 44 | 2.3-fold |

| Clozapine, 9 days | 2 | 13.9 ± 0.5 (1.3) | 18.9 ± 0.7 (1.4) | 5 ± 0.6 | 2.6-fold | 39 ± 10 | 1.7-fold | 36 | 1.9-fold |

| Olanzapine, 9 days | 2 | 11.9 ± 0.6 (1.86) | 16 ± 0.5 (1.8) | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 2.1-fold | 55 ± 12 | 2.4-fold | 40 | 2.1-fold |

| Risperidone, 9 days | 2 | 13.3 ± 0.5 (1.9) | 18.3 ± 0.6 (2.1) | 5 ± 0.6 | 2.6-fold | 33 ± 8 | 1.6-fold | 60 | 3.2-fold |

| Quetiapine, 9 days | 2 | 12.8 ± 0.4 (1.4) | 16.8 ± 0.7 (1.4) | 4 ± 0.7 | 2.1-fold | 49 ± 10 | 2.1-fold | 26 | 1.4-fold |

| Ethanol withdrawal | 8 | 19 ± 0.8 (1.5) | 26.1 ± 0.8 (2) | 7.2 ± 0.6 | 3.7-fold | 33 (n = 1) | 3-fold | ND | ND |

| Hippocampus lesion | 3 | 12.1 ± 4 (1.5) | 20 ± 5 (1.8) | 7.9 ± 0.9 | 4.1-fold | 17 (n = 3) | 1.7-fold | 37 (n = 3) | 3.7-fold |

| Amphetamine sensitized | 2 | 19.3 ± 0.7 (2.3) | 25.3 ± 0.6 (2.7) | 6 ± 0.7 | 3.1-fold | 38 (n = 1) | 3.5-fold | ND | ND |

| Vaginal birth (control) | 3 | 12.6 ± 0.4 (2.3 ± 0.3) | 13.7 ± 0.2 (1.5 ± 0.2) | 1.1 ± 0.3 | Control | 10 ± 2 | Control | 16 ± 2 | Control |

| Cesarean section | 3 | 10.3 ± 0.6 (1.3 ± 0.1) | 16.3 ± 0.9 (1.1 ± 0.1) | 6.1 ± 0.3 | 5.6-fold | 27 ± 3 | 2.7-fold | 32 ± 3 | 2-fold |

| Cesarean section + anoxia | 3 | 12.9 ± 0.7 (1.5 ± 0.2) | 18.4 ± 1.2 (1.5 ± 0.1) | 5.5 ± 0.7 | 5-fold | 27 ± 3 | 2.7-fold | 36 ± 3 | 2.3-fold |

| Control striata | 2 | 17.3 ± 3.2 (2) | 18.5 ± 3 (1.9) | 1.15 ± 0.25 | Control | 28 ± 4 | Control | 14 ± 4 | Control |

| Gprk6 knockout | 2 | 15.2 ± 3.2 (0.8) | 20.3 ± 3.4 (1.1) | 5.1 ± 0.2 | 4.4-fold | 46 ± 5 | 1.6-fold | 32 ± 6 | 2.3-fold |

| Control striata | 2 | 16.2 ± 0.2 (1.98) | 16.8 ± 0.3 (1.8) | 0.6 ± 0.1 | Control | 25 ± 5 | Control | 18 ± 4 | Control |

| Drd4 knockout | 2 | 14.8 ± 0.9 (1.6) | 20.7 ± 0.9 (2) | 5.95 ± 0.1 | 9.9-fold | 48 ± 5 | 1.9-fold | 42 ± 4 | 2.3-fold |

| Control striata | 2 | 14.9 ± 0.9 | 17.5 ± 0.4 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | Control | 16 ± 5 | Control | 10 ± 4 | Control |

| Dbh knockout | 3 | 15.3 ± 1.3 | 23.5 ± 1.7 | 8.3 ± 3 | 3.2-fold | 30 ± 5 | 1.9-fold | 30 ± 5 | 3-fold |

| Control striata | 4 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 22 ± 3 | Control |

| Comt knockout | 4 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 42 ± 3 | 1.9-fold |

| Control striata | 2 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 14 ± 2 | Control |

| Drd1a knockout | 2 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 14 ± 2 | Same as control |

| Control striata | 5 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 13.6 ± 3.6 | Control |

| Quinpirole-sensitized | 9 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 21.8 ± 3.2 | 1.6-fold |

| Control nucleus accumbens | 5 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 19 ± 3 | Control |

| Quinpirole-sensitized | 9 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 28 ± 3 | 1.5-fold |

| Control striata | 8 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 12.5 ± 8.5 | Control |

| Phencyclidine-sensitized | 8 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 34.5 ± 4 | 2.8-fold |

| Control striata | 6 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 13.7 ± 1.1 | Control |

| Dopamine-deficient | 6 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 30 ± 3.1 | 2.2-fold |

Scatchard experiments (first two columns) contained 120 mM NaCl. Competition experiments for dopamine/[3H]raclopride contained 10 mM NaCl, and those for dopamine/[3H]domperidone contained 120 mM NaCl. ND = not done; ± indicates SE. Numbers in parentheses in first two columns are [3H]raclopride Kd values.

n = 2 independent experiments unless stated otherwise

D2High calculated as Total D2 density – D2 density

Fold differential calculated as D2High/control D2High

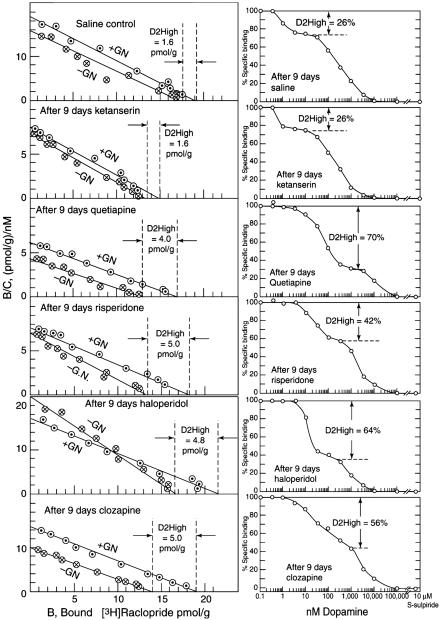

Ethanol and Amphetamine Sensitization. When both the [3H]raclopride saturation and dopamine/[3H]raclopride competition methods were used, the density of D2High states increased by 3- to 4-fold in ethanol-withdrawn rats and in amphetamine-sensitized rats (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Increase in D2High states after 9 days of antipsychotic treatment. (Left) [3H]Raclopride saturation method (additional details in Fig. 1). (Right) Dopamine/[3H]raclopride competition method. Representative experiments are shown (Table 1).

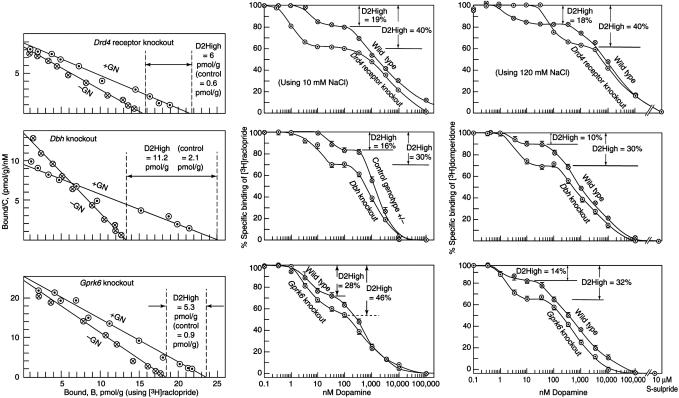

Dopamine Supersensitivity in Gene Knockout Mice. As mentioned earlier, mice with a targeted deletion of the Dbh gene, the Drd4 dopamine receptor gene, the Gprk6 gene, the Comt gene, or the Th-/-, DbhTh/+ gene, are supersensitive to amphetamine or dopamine. Correspondingly, when one or more of the three methods was used, all of these homozygous knockout mice revealed an elevated density of D2High states, ranging from 3.6-fold (over control) for the Dbh knockouts to 9.9-fold for the Drd4 knockouts (Figs. 3 and 4 and Table 1).

Fig. 3.

Increase in D2High states in gene knockouts for the Drd4 dopamine receptor, Dbh, and Gprk6.(Left)[3H]Raclopride saturation method (see Fig. 1). (Center) Dopamine/[3H]raclopride competition method. (Right) Dopamine/[3H]domperidone competition method. Representative experiments are shown, bars indicate SE (Table 1).

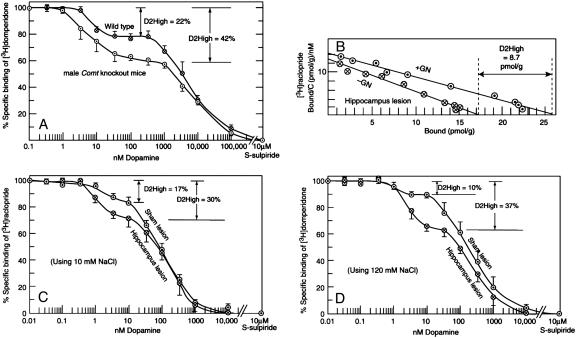

Fig. 4.

Increased D2High states in knockouts and lesions. (A) Increase in D2High states in gene knockouts for Comt, using the dopamine/[3H]domperidone competition method (n = 4 ± SE; Table 1). (B) Increase in D2High states in striata from adult animals that had been lesioned in the hippocampus at an early age. [3H]Raclopride saturation method; control value was 2 pmol/g (see Table 1). (C) Dopamine/[3H]raclopride competition method. (D) Dopamine/[3H]domperidone competition method. Bars indicate SE (n = 3; Table 1).

Neonatal Hippocampal Lesion. When all three methods were used, the density of D2High states increased by 2- to 4-fold in rats that had been lesioned in the hippocampus neonatally (Fig. 4 B-D).

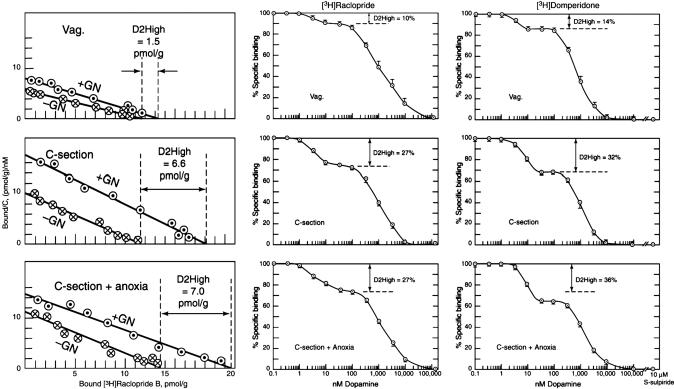

Rats Born by Cesarean Section. Rats born by cesarean section with or without anoxia become supersensitive to amphetamine as adults (20). Here, too, the D2High states were elevated by 5- to 5.6-fold by using the [3H]raclopride saturation method, 2.7-fold by using the dopamine/[3H]raclopride competition method, and 2.3- to 2.7-fold by using the dopamine/[3H]domperidone competition method (Fig. 5 and Table 1), all compared to striata from rats born normally by vaginal birth.

Fig. 5.

Increase in D2High states in adult rats born by cesarean section with or without anoxia. (Left) [3H]Raclopride saturation method. (Center) Dopamine/[3H]raclopride competition method. (Right) Dopamine/[3H]domperidone competition method. Representative experiments are shown; vertical bars indicate SE (Table 1).

Drd1a Receptor Knockout as Control. It was essential to determine whether dopamine D2High states were elevated in other gene-knockout animals that did not exhibit amphetamine supersensitivity. Therefore, we chose the Drd1a dopamine receptor-knockout mouse (25) because this animal is not supersensitive to amphetamine (26). The data (Table 1), using the dopamine/[3H]domperidone competition method, illustrate that the density and proportions of D2High states were normal in the Drd1a receptor-knockout mice.

Rats Sensitized to Quinpirole or Phencyclidine. Behavioral sensitization and dopamine supersensitivity also occurs in rats sensitized with the dopamine D2 agonist quinpirole (27). When the [3H]domperidone method was used, quinpirole increased the proportion of D2High states in striatal tissue from 13.6 ± 3.6% (control) to 21.8 ± 3.2%, an increase of 1.6-fold (Table 1). In addition, because Heusner et al. (28) found that the amphetamine-induced locomotor response in dopamine-deficient mice was fully restored by restoring dopamine selectively in the nucleus accumbens, we also examined whether quinpirole sensitization altered the D2High states in the nucleus accumbens. In fact, quinpirole increased the proportion of D2High states in this brain region from 19 ± 3% (control) to 28 ± 3%, an increase of 1.5-fold (Table 1). The increase was 2.8-fold for phencyclidine-sensitized rats.

Discussion

Several previous studies have examined whether the proportion of high-affinity states for D2 were elevated after antipsychotics (29) or in Gprk6 knockouts (14), with little if any significant change. This is because most laboratories have been using a dopamine/[3H]spiperone competition method. However, as shown elsewhere (23), dopamine (with its Kd of 1.75 nM) is not effective in competing versus the much more tightly bound [3H]spiperone (with its Kd of 60 pM), especially in 120 mM NaCl.

It is not known whether the saturation method and the two competition methods reveal the same population of D2High states. It is likely that the saturation method reveals D2High states that are normally occluded or occupied by endogenous dopamine. However, the competition method may reveal D2High states that are either occupied or not occupied by dopamine. Further work will be needed to examine this.

It is surprising that these diverse impairments of the brain (drugs, lesions, gene knockouts, cesarean sections) all resulted in a common D2High basis for dopamine supersensitivity, especially surprising in cases where no direct interference with dopamine transmission was made. It is possible that this shift to more D2High states is a nonspecific reaction to brain impairment, making the animal more responsive to a change in its environment. However, the Drd1a knockout data (with reduced sensitivity to amphetamine and normal proportions of D2High states) indicate that the knockout process does not elicit a nonspecific increase in sensitivity to amphetamine or in D2High states.

Although the sensitization procedures were also associated with small increases in the total population of D2 receptors, these increases were especially small compared to the elevations found in the D2High states. For example, compared to controls (in the presence of guanilylimidodiphosphate), the total D2 density went up by 10% in Gprk6 knockouts, 23% in Drd4 knockouts, and 34% in Dbh knockouts, in contrast to the elevations of 3.2- to 9.9-fold in the D2High component. In the case of the cesarean section rats, previous work (20) did not reveal a significant rise in the total D2 population, a situation similar to that found in ethanol withdrawal or after amphetamine sensitization (21, 22).

All of the animals in this study are known to be supersensitive to amphetamine or dopamine agonists with the exception of the Drd1a knockout mice (26), which revealed a normal proportion of D2High states. The present data suggest that the sensitivity to amphetamine may be related to the magnitude of the D2High states. However, the converse may not hold. That is, although the present data support the principle that dopamine supersensitivity is associated with more D2High states, it is possible that other types of treatment may alter the number of D2High states but not alter the sensitivity to dopamine.

Additional animal models will be useful in determining whether the significant shift in the numbers of D2 receptors in a low-affinity state to a high-affinity state is consistently associated with dopamine supersensitivity and/or alteration in the reward state. If this relation persists, it would warrant molecular and brain imaging studies exploring the basis of dopamine supersensitivity in psychosis, Parkinson's disease, and hyperactivity disorders. Biochemically, a variety of molecular mechanisms may underlie receptor supersensitivity, including oligomerization, and altered interactions between G protein subunits, GDP, adenylyl cyclases, guanine nucleotide exchange factors, RGS proteins, GRKs, and arrestins, and phosphorylation status of any of these proteins. Finally, the present results imply that there may be many pathways leading to psychosis, including multiple gene mutations, drug abuse, or brain injury, all of which may converge via D2High to elicit psychotic symptoms (8).

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. R. J. Lefkowitz and Marc Caron for assistance in providing the GRK6/del tissues, and Dr. H.-C. Guan, Katherine L. Suchland, Paul J. Kruzich, and Audrey Younkin for outstanding technical support. This work was supported by the Ontario Mental Health Foundation (Regular grant and Special Initiatives grant), the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression, the Canadian Instititutes of Health Research (P.S., R.Q., L.K.S., and P.B.), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (P.S., S.R.G., B.F.O., and M.E.-G.), the Canadian Psychiatric Research Foundation, the Medland and O'Rorke families, the Dr. Karolina Jus estate, National Institute of Mental Health Grants MH67497 and DA12062 (to D.K.G.), The National Agency of Technology (TEKES, Grant 40160/99, to P.T.M.), and Academy of Finland Grant 73012 (to P.T.M.), and in part by the Institutional Grant for Neurobiology Grant GM07108-29 (to S.R.).

Author contributions: P.S., M.L.P., and T.T. designed research; P.S., D.W., R.Q., L.K.S., S.K.B., D.K.G., R.T.P., T.D.S., P.B., M.E.-G., M.L.P., P.T.M., S.R., and R.D.P. performed research; P.S. and T.T. analyzed data; P.S. wrote the paper; D.W., D.K.G., R.T.P., T.D.S., M.E.-G., B.F.O., S.R.G., P.T.M., and S.R. provided gene knockout tissues; R.Q., L.K.S., and S.K.B. provided lesioned tissues; P.B. provided Cesarean-born animal tissues; M.L.P. provided drug-sensitized animal tissues; and R.D.P. provided consultations, revisions, and gene knockout tissues.

Abbreviation: GN, guanilylimidodiphosphate.

References

- 1.Lewis, C. M., Levinson, D. F., Wise, L. H., DeLisi, L. E., Straub, R. E., Hovatta, I., Williams, N. M., Schwab, S. G., Pulver, A. E., Faraone, S. V., et al. (2003) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 73, 34-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glatt, S. J., Faraone, S. V. & Tsuang, M. T. (2003) Mol. Psychiatry 8, 911-915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seeman, P., Chau-Wong, M., Tedesco, J. & Wong, K. (1975) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA 72, 4376-4380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seeman, P. (2002) Can. J. Psychiatry 47, 27-38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nordstrom, A. L., Farde, L., Eriksson, L. & Halldin, C. (1995) Psychiatry Res. 61, 67-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abi-Dargham, A., Rodenhiser, J., Printz, D., Zea-Ponce, Y., Gil, R., Kegeles, L. S., Weiss, R., Cooper, T. B., Mann, J. J., Van Heertum, R. L., et al. (2000) Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci USA 72, 7673-7675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.George, S. R., Watanabe, M., DiPaolo, T., Falardeau, P., Labrie, F. & Seeman, P. (1985) Endocrinology 117, 690-697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curran, C., Byrappa, N. & McBride, A. (2004) Br. J. Psychiatry 185, 196-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhardwaj, S. K., Beaudry, G., Quirion, R., Levesque, D. & Srivastava, L. K. (2003) Neuroscience 122, 669-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seeger, T. F., Thal, L. & Gardner, E. L. (1982) Psychopharmacology 76, 182-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robinson, T. E. & Berridge, K. C. (2000) Addiction 95, Suppl. 2, S91-S117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinshenker, D., Miller, N. S., Blizinsky, K., Laughlin, M. L. & Palmiter, R. D. (2002) Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 13873-13877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubinstein, M., Phillips, T. J., Bunzow, J. R., Falzone, T. L., Dziewczapolski, G., Zhang, G., Fang, Y., Larson, J. L., McDougall, J. A., Chester, J. A., et al. (1997) Cell 90, 991-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gainetdinov, R. R., Bohn, L. M., Sotnikova, T. D., Cyr, M., Laakso, A., Macrae, A. D., Torres, G. E., Kim, K. M., Lefkowitz, R. J., Caron, M. G., et al. (2003) Neuron 38, 291-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huotari, M., Garcia-Horsman, J. A., Karayiorgou, M., Gogos, J. A. & Männistö, P. T. (2004) Psychopharmacology 172, 1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gogos, J. A., Morgan, M., Luine, V., Santha, M., Ogawa, S., Pfaff, D. & Karaiorgou, M. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 9991-9996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou, Q. Y. & Palmiter, R. D. (1995) Cell 83, 1197-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim, D. S., Szczypka, M. S. & Palmiter, R. D. (2000) J. Neurosci. 20, 4405-4413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson, S., Smith, D. M., Mizumori, S. J. Y. & Palmiter, R. D. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 13329-13334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boksa, P., Zhang, Y. & Bestawros, A. (2002) Exp. Neurol. 175, 388-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seeman, P., Tallerico, T. & Ko, F. (2004) Synapse 52, 77-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seeman, P., Tallerico, T., Ko, F., Tenn, C. & Kapur, S. (2002) Synapse 46, 235-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seeman, P., Tallerico, T. & Ko, F. (2003) Synapse 49, 209-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kapur, S., Vanderspek, S. C., Brownlee, B. A. & Nobrega, J. N. (2003) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 305, 625-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El-Ghundi, M., O'Dowd, B. F. & George, S. R. (2001) Brain Res. 892, 86-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crawford, C A., J. Drago, J., Watson, J. B. & Levine, M. S. (1997) NeuroReport 8, 2523-2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szechtman, H., Eckert, M. J., Tse, W. S., Boersma, J. T., Bonura, C. A., McClelland, J. Z., Culver, K. E. & Eilam, D. (2001) BMC Neurosci. 2, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heusner, C. L., Hnasko, T. S., Szczypka, M. S., Liu, Y., During, M. J. & Palmiter, R. D. (2003) Brain Res. 980, 266-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacKenzie, R. G. & Zigmond, M. J. (1984) J. Neurochem. 43, 1310-1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]