Abstract

Previous research suggests that interlimb differences in coordination associated with handedness might result from specialized control mechanisms that are subserved by different cerebral hemispheres. Based largely on the results of horizontal plane reaching studies, we have proposed that the hemisphere contralateral to the dominant arm is specialized for predictive control of limb dynamics, while the non-dominant hemisphere is specialized for controlling limb impedance. The current study explores interlimb differences in control of 3-D unsupported reaching movements. While the task was presented in the horizontal plane, participant’s arms were unsupported and free to move within a range of the vertical axis, which was redundant to the task plane. Results indicated significant dominant arm advantages for both initial direction accuracy and final position accuracy. The dominant arm showed greater excursion along a redundant axis that was perpendicular to the task, and parallel to gravitational forces. In contrast, the non-dominant arm better impeded motion out of the task-plane. Nevertheless, left arm task errors varied substantially more with shoulder rotation excursion than did dominant arm task errors. These findings suggest that the dominant arm controller was able to take advantage of the redundant degrees of freedom of the task, while non-dominant task errors appeared enslaved to motion along the redundant axis. These findings are consistent with a dominant controller that is specialized for intersegmental coordination, and a non-dominant controller that is specialized for impedance control. However, the findings are inconsistent with previously documented conclusions from planar tasks, in which non-dominant control leads to greater final position accuracy.

Introduction

Handedness is a self-evident aspect of human motor control that is thought to reflect asymmetry between the right and left hemisphere motor control circuitry. The sensorimotor mechanisms that underlie this asymmetry have been investigated for over a century, beginning with the seminal work of Woodworth (Woodworth, 1899). Woodworth’s experiments showed clear advantages in accuracy of right hand movements that became more pronounced when participants made rapid, ‘ballistic’ movements. Such movements were termed ‘ballistic’ because, similar to projectile motion, once rapid movements were initiated, they were thought to play out without significant corrections. More specifically, Woodworth proposed that for rapid movements made toward targets, the initial phase of motion, prior to peak velocity, is largely ballistic or uncorrected, whereas the deceleration phase utilizes feedback mechanisms to both correct and stop the movement. For rapid upper limb reaching movements, this idea has been well supported by experimental studies that have applied perturbations and assessed response latencies (Brown and Cooke, 1981; Gordon and Ghez, 1987; Gottlieb and Corcos, 1989; Mutha and Sainburg, 2009). These findings have led to a two-phase model of motor control in which the first phase, prior to peak velocity is characterized as open-loop, reflecting anticipatory processes, and the final phase is characterized as largely closed-loop, including online corrective processes.

Many early studies examining motor lateralization have focused on this simple two-phase model in attempt to discover the processes that underlie handedness. One prominent idea proposed by Flowers was that the hemisphere contralateral to the dominant arm, subsequently referred to as the ‘dominant hemisphere’, might be specialized in processing visual feedback (Flowers, 1975). In contrast to this idea, Annett et al. (1979) hypothesized that the fewer errors, and thus error-corrections, that occurred when the dominant hand completes a pegboard task indicates that dominant control is more effective in planning movement. Later studies revealed that the differences between the hands were not affected by visual feedback, supporting Annett’s proposition that handedness results from asymmetries in open-loop control mechanisms (Roy and Elliott, 1986; Carson et al., 1990). However, this view was challenged by studies that assessed cerebral asymmetry for motor control by examining movements in patients with unilateral brain damage. These studies examined motor performance in the ipsilesional, non-paretic arm of stroke patients. This paradigm is based on the idea that both hemispheres contribute different aspects of control to each arm. Thus, damage to one hemisphere should be evident in the ipsilateral arm. Beginning with the early work of Wyke (1967), a large number of studies have confirmed that coordination deficits do occur in the ipsilesional arm of stroke patients and that these deficits can be different, depending on the side of the damage (Haaland et al., 1977; Haaland and Delaney, 1981; Fisk and Goodale, 1988; Haaland and Harrington, 1989). A number of studies have shown that left hemisphere damage produces ipsilesional deficits in the early open-loop phase of motion, whereas right hemisphere damage produces deficits in the closed-loop phase of motion (Haaland and Harrington, 1989; Winstein and Pohl, 1995; Haaland et al., 2004). Thus, studies in participants without hemisphere damage and stroke survivors have supported the idea that the neural asymmetries underlying handedness involve hemispheric specializations for open-loop and closed-loop processes. However, there has been substantial disagreement about which processes are associated with dominant or non-dominant arm control.

Dynamic Dominance Hypothesis

Building on this line of research, we have developed a hypothesis that provides a control-theory based explanation for the motor control processes that might underlie handedness. Studies in individuals without nervous system impairments have suggested that the dominant arm shows greater proficiency in predictive control of limb dynamics, including dynamic interactions associated with multiple segment coordination (Sainburg and Kalakanis, 2000; Sainburg, 2002; Sainburg, 2014), but also including predictive control of movement distance when moving only a single segment (Sainburg and Schaefer, 2004). In contrast, the non-dominant controller appears specialized for specifying and achieving steady states and for impeding unexpected perturbations though on-line processes that might control limb impedance (Sainburg, 2002; Yadav and Sainburg, 2014). We termed this hypothesis ‘dynamic dominance’. According to this hypothesis, the dominant hemisphere is able to more accurately predict the dynamic effects of movements through optimization-like processes that might minimize trajectory and energetic costs (Flash and Hogan, 1985; Nakano et al., 1999; Todorov and Jordan, 2002; Nishii and Taniai, 2009; Yadav and Sainburg, 2011). We hypothesize that non-dominant specialization for impedance control does not minimize such costs, but instead insures robustness against unexpected environmental conditions, leading to more stable movements or postures. In a recent test of this hypothesis, participants were exposed to velocity dependent force fields that were unpredictable in amplitude and varied between trials, or that were consistent and predictable between trials. When using the dominant arm, participants performed better in the consistent field, while the non-dominant arm performed better in the inconsistent field. This supported a dominant hemisphere specialization for predictive control and a non-dominant specialization for impedance control (Yadav and Sainburg, 2014). This was one of the first studies to show consistent non-dominant arm superiority for specific aspects of control.

The hypothesized specialization of the non-dominant arm for impedance control may also impart advantages when making movements in the absence of visual feedback to a large array of targets (32). In this case, the non-dominant arm shows greater position accuracy across most of the workspace than the non-dominant arm (Przybyla et al., 2013). However, when conditions are more predictable, such as when reaching to only three targets over repetitive trials, the dominant and non-dominant arms tend to show equivalent final position accuracies (Sainburg et al., 1999). However, we do not know whether such advantages of the non-dominant arm for final position accuracy are robust to variations in task conditions. The dynamic dominance hypothesis has also been supported by studies of ipsilesional arm control in right-handed patients with unilateral brain damage (Haaland; Sainburg; etc.). These studies have shown that left hemisphere damage produces deficits in predictive control of distance during single joint movements (Schaefer et al.,, 2007), and deficits in direction and interjoint coordination during multijoint movements (Schaefer, Haaland, and Sainburg, 2009). Left hemisphere damage also results in deficits in adapting movement trajectories, but not final positions. In contrast, right hemisphere damage produces deficits in stabilizing the final positions of single joint movements (Schaefer et al., 2007) and multijoint movements, and adapting final position accuracies over repetitive trials (Schaefer et al., 2009). We propose that the dynamic dominance hypothesis reflects a more detailed and mechanistic modification of previous open-loop/closed-loop proposals to account for handedness. While the dominant system appears specialized for largely open-loop prediction of limb dynamics, the non-dominant system is specialized for largely closed-loop control of limb impedance.

However, a significant limitation of our previous studies on handedness is that the reaching movements were almost always performed in the horizontal plane, with the arms supported on air sleds to reduce the effects of gravity and friction. This allowed us to control the effects of intersegmental dynamics, because in this horizontal plane frictionless environment, the non-muscular forces acting on the limb are primarily inertial, including intesegmental interaction torques. In addition, the movements are constrained and do not exhibit the redundancy that is available during unconstrained 3-D motion. While this reduction allows one to address specific questions about control and coordination, it does not address how movements are coordinated in a gravitational field and when confronted with redundant degrees of freedom. Previous research has emphasized the role of gravitational forces in planning and execution of movements (Papaxanthis, et al., 2003; Gentili, et al., 2007). Bernstein (1930) observed through hammering movements, that people never produce exactly the same movement between repetitions. Instead, they utilize the redundant degrees of freedom in the musculoskeletal system to reveal infinitely variable solutions to reach the end goal. This redundancy introduces motor abundance (Latash, 2012), which may help to stabilize task performance across multiple trials. We now examine unsupported reaching movements made toward targets presented in a horizontally displayed workspace, but performed in 3-D.

While previous studies have demonstrated asymmetries in coordination of the dominant and non-dominant arms during natural tasks performed in 3-dimensions, such as throwing (Hore et al., 2005), carrying infants (Harris, 2014), and kayak paddling (Rynkiewicz and Starosta, 2011), whether such asymmetries correspond to the coordination asymmetries described by the dynamic dominance hypothesis remains unclear. The current study was designed as a step toward testing this question. In this study, participants reached toward targets presented in the horizontal plane but requiring the participants to support their own arms in space. Because the task was presented as a horizontal plane projection of the hand, z-axis displacement of the hand was completely redundant to the task. In this way, we required participants to control their movements in a gravitational field, as well introducing degrees of freedom that were redundant to the task. We compared performance of the dominant and non-dominant arm to see how the differences in control mechanisms between the hemispheres are expressed during performance of a 3-D reaching task.

Experimental Procedures

Participants

Participants were 20 healthy, right-handed adults aged 18–25 years old. All participants were screened for handedness using the Edinburgh Inventory (Oldfield, 1971) and provided informed consent before participation in this study, which was approved by the institutional review board of Penn State University.

Experimental setup

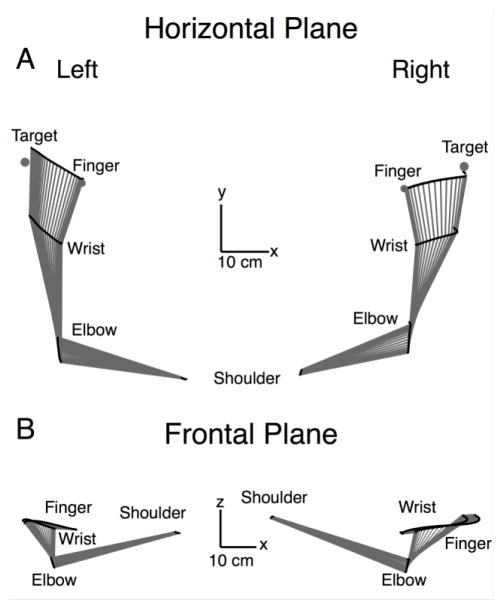

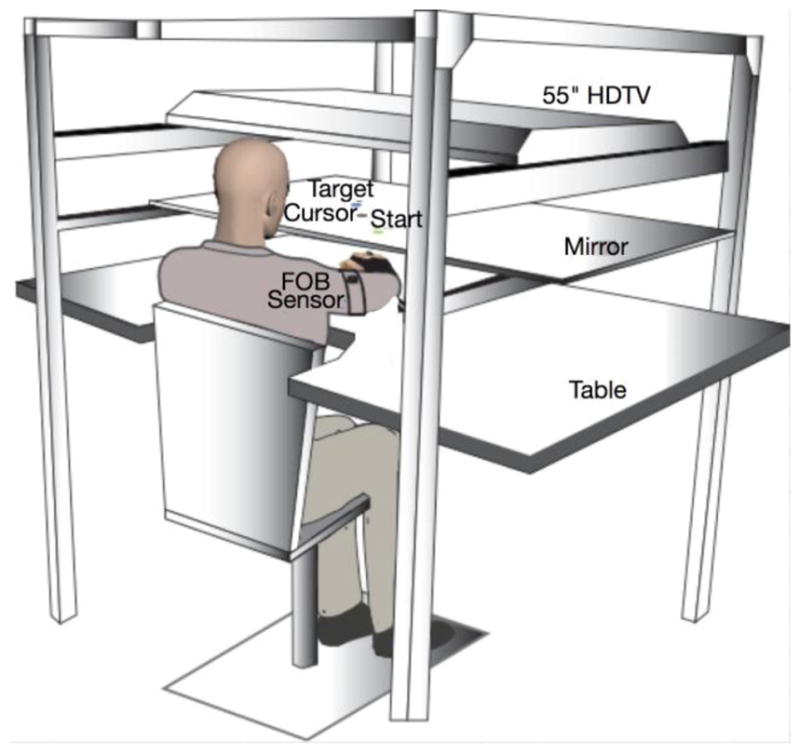

Participants were seated at a 2-D virtual reality workspace in which stimuli from a TV screen were reflected by a mirror, with the participants’ arms under the mirror. Figure 1 shows this experimental set-up. Participants’ arm movements were tracked using 6 DOF magnetic sensors (Ascension TrackStar) placed on the wrist and upper arm. Vision of the participants’ arms was occluded while position of the hand was provided as a cursor on the screen. Both wrists and fingers were immobilized using a splint, while all degrees of freedom through the shoulder, elbow, and forearm were available.

Figure 1.

Experimental Set-up: A TV screen was positioned above a mirror, creating a 2-D virtual reality environment.

Experimental Task

The task required multijoint reaches to three different targets. The three targets were 2.5 cm in diameter and required movements of equal elbow extension (20 degrees), but varying degrees of shoulder flexion. Target 1 required 10 degrees of shoulder flexion, Target 2 required 20 degrees and Target 3 required 30 degrees. Participants reached to these targets, holding their arms above table, and were thus able to move freely in a range of 3-D space. The range of space in the z-axis was limited to the space between the table and the mirror, which was 30 cm. For each trial, participants moved the cursor into a starting circle, and waited for 300 milliseconds, at which time an auditory ‘go’ tone was provided. Participants were required to lift their hand and elbow off the table in order to see the cursor and start the trial, and were instructed to keep their arms off the table for the duration of the movement. When the participants moved the cursor outside of the starting circle to start the trial, the cursor disappeared. Participants were instructed to move quickly and accurately to the target circle, and were given points for motivation. Points were available for all movements made with a peak tangential hand velocity of 0.7 m/s or higher. Participants performed blocks of 30 reaching movements per arm (10 per target) with either the left or right arm.

Kinematic Analysis

The three-dimensional position of the index finger, elbow, and shoulder were calculated from sensor position and orientation data and elbow and shoulder angles were calculated from these. All kinematic data were low-pass filtered at 8 Hz (3rd order, dual pass Butterworth). The three main measures of task performance for this study were final position error, direction error, and linearity. Final position error was calculated as the distance between the index finger location at movement end and the target position. Direction error was calculated as the angle between the vector from the start to the target circle, and the vector originating at the starting location of the hand and terminating at the point at which the peak tangential hand velocity occurred. Deviation from linearity was assessed in 2-D and 3-D as the minor axis divided by the major axis of the hand path. The major axis was defined as the largest distance between any two points in the path, while the minor axis was defined as the largest distance, perpendicular to the major axis, between any two points in the path (Sainburg, 2002; Sainburg et al., 1993).

Statistical Analysis

Our primary hypothesis was that reaching coordination will vary with arm, when reaching unsupported in 3-Dimensions. We used a 3 target (within participant) by 2 hand (group) design (Sainburg et al., 1999; Bagesteiro and Sainburg, 2002). We predicted that measures of task performance and coordination would depend on both target (within hand) and hand (group). Statistical analysis was done using a 3 X 2 mixed factor ANOVA model. Significant interactions and main effects were subjected to post-hoc analysis using the Student’s t test. We used a simple linear regression analysis to assess the relationships between specific variables. Comparison of correlations between subjects was done using the Fisher transformation and comparing the correlation coefficients using Student’s t-tests.

Results

Arm Kinematics

Figure 2a shows typical hand paths from two different participants to each target for the left and right hands and illustrates arm movement for Target 1 in the horizontal plane. The lines showing the whole arm movements represent stick figures of the arm drawn between every 2 collected data points (17.2 milliseconds). In the horizontal plane (figure 2a), the hand paths appear roughly similar between the arms (participants), while the right arm movements appear slightly more accurate in direction and final position. While the horizontal projections appear similar, the frontal plane projections show quite distinct differences between the arms. Figure 2b shows the frontal plane projections of the movements shown in figure 2a. For the left hand, the elbow, wrist and finger show restricted displacement on the Z (vertical axis), indicating that motion remained largely within the horizontal plane. In contrast, the right arm shows greater displacement along the z-axis .

Figure 2.

Hand Paths: A) Horizontal plane projection of hand paths from two different subjects for the left and right arm to all targets, as well as whole arm representation of movements to Target 1. B) Projections of the arm into the frontal plane of the same movements to Target 1 shown in A.

Kinematics in the Horizontal Plane

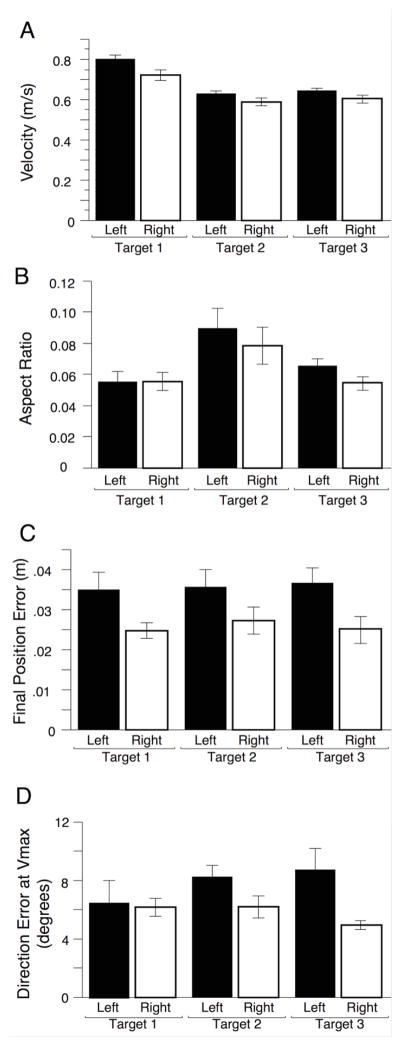

The bar graphs in figure 3a–d show mean ±SE performance measures in the horizontal plane, reflecting performance in the horizontal task space. Figure 3a shows maximum velocity, which varied systematically with target (F(2,36)= 23.3644, p< .0001) but showed no main effect of hand (F(1,18)= .7613, p= .3944), nor interactions between hand and target (F(2,36)= .4124, p= .6651). We measured horizontal plane linearity as aspect ratio (see methods) shown in Figure 3b. Aspect ratio showed a main effect of target (F(2,36)= 9.2939, p= .0006), but not of hand (F(1,18)= .7273 , p= .4050), nor interactions between target and hand (F(2,36)= .4060 , p= .6693). Figure 3c shows our measure of final position error, which although consistent across targets (F(2,36)= .1628, p= .8504) showed a significant main effect of hand (F(1,18)= 7.1025, p= .0158), such that the left non-dominant arm had significantly higher errors than the right-dominant arm. In our previous study of planar supported movements, such trends did not reach significance (Sainburg et al., 1999). Figure 3d shows how well the initiation of movement was directed toward the target, measured as direction error at the maximum of hand tangential velocity. While there was no effect of target (F(2,36)=. 4489, p= .6418), the left hand had significantly larger direction errors at peak velocity (F(1,18)= 5.4351, p= .0316) and no interaction (F(2,36)= 1.7184, p= .1937).

Figure 3.

2-D Hand Kinematic Measures: Mean and ± SE bars across all subjects, shown for both target and hand for A) Peak Velocity, B) Aspect ratio (linearity), C) Final Position Error, D) Direction Error at Peak Velocity.

Kinematics Out of the Horizontal Plane

The task presented in this study provided feedback about the projection of hand motion within the horizontal plane, and task success depended completely on the projection of motion within this task space. However, we did not constrain the arm within this plane. Instead, participants were required to hold their arm above the tabletop, and the arm was free to move along the z-axis. Thus, movement in the z-axis was redundant to the task. A successful hand position within the target, for example, could be achieved by an infinite range of positions along the z-axis.

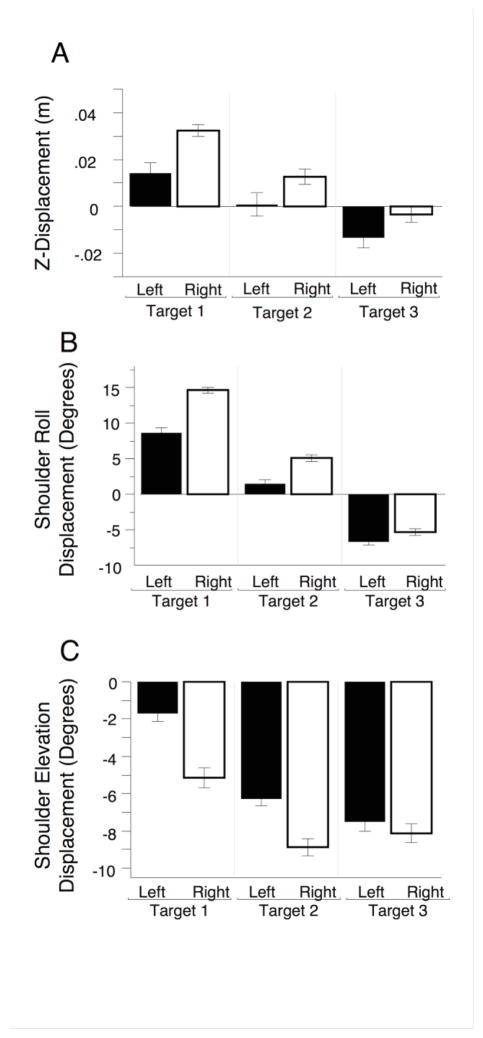

We examined whether movements outside of the horizontal plane, and thus redundant to the task, were different between the arms (groups). Figure 4a shows the displacement on the z-axis for the hand-path, from the beginning to the end of movement. We found a main effect of hand, such that right hand z-displacement was greater (F(1,18)= 8.2126, p= .0103), a main effect of target (F(2,36)= 86.3551, p<.0001) but this effect was similar for both hands such that there were no interactions between hand and target (F(2,36)= 1.5777, p=.2204).

Figure 4.

Redundant Axis Movement: Mean and ± SE bars across all subjects, shown for both target and hand for A) Displacement in the z-axis, B) Shoulder roll displacement, C) Shoulder elevation displacement.

We next examined the joint kinematics that gave rise to this arm-difference in z-displacement. In this minimally constrained task (wrists splinted) with the upper arms abducted above 45° and the elbow close to 90°, shoulder roll (internal/external rotation) and shoulder elevation (abduction/adduction) can substantially contribute to hand motion along the z-axis. Figures 4b and 4c show shoulder roll and elevation displacement from start to end, respectively, for the three targets and two arms. For shoulder roll (figure 4b), the relationship to hand and target appears similar to the z-axis displacement relationship shown in figure 4a. The right hand showed greater external rotation for targets 1 and 2, while target 3 showed less difference between the hands in internal rotation displacement. In support of this, our ANOVA showed a main effect of hand (F(1,18)= 4.6024, p= .0458, a main effect of target (F(2,36)= 250.5701, p<.0001), as well as an interaction between hand and target (F(2,36)= 4.2807, p= .0215). This interaction is reflected by the larger change across targets for the right, as compared to the left arm. In contrast to shoulder roll measures, Shoulder elevation (Figure 4c) showed a starkly different pattern across targets and hands than did z-displacement and shoulder roll. While the amount of shoulder adduction increased across targets (Main effect of target: F(2,36)= 21.1824, p<.0001), no main effect of hand (F(2,36)= 2.6017, p= .1241), nor interactions (F(2,36)= 1.8229, p= .1762) occurred.

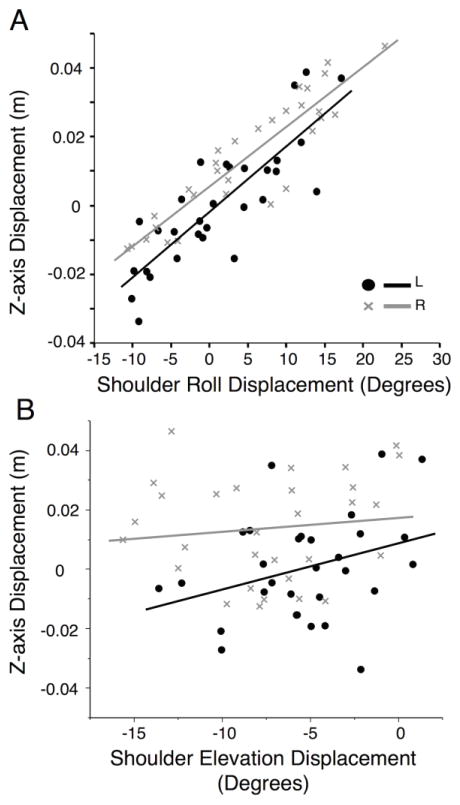

The similarity in the pattern of shoulder roll displacement (figure 4b) and z-axis displacement (figure 4a) led us to examine the relationship between these measures, through linear correlation analysis. Figure 5a and 5b show the relationship between z-axis displacement and shoulder roll (figure 5a) and z-axis displacement and shoulder elevation (figure 5b). Each point in Figures 5a and 5b reflects the mean of one participant for one of the targets, with the right arm participants shown as gray “X” and the left arm participants with the black dots. Our correlation analysis indicated a strong dependence of z-axis displacement on shoulder roll in both the left (R2= .70), and the right (R2= .83) arms. In contrast, there was very little correlation between z-displacement with shoulder elevation in the left (R2= .10), or the right arms (R2= .014). We conclude that hand displacement on the z-axis, reflecting out-of-horizontal plane motion, was largely a result of shoulder roll for both hands.

Figure 5.

Shoulder Movements vs. Z-axis Displacement: Linear correlations shown for by left non-dominant (black) and right dominant (gray) arms of A) z-axis displacement vs. shoulder roll displacement (right: R2= .83, left: R2= .70), and B) z-axis displacement vs. shoulder elevation displacement (right: R2= .014, left: R2= .10). Points represent means of one subject to one target, with non-dominant left being represented by black dots and dominant right being represented by a gray X.

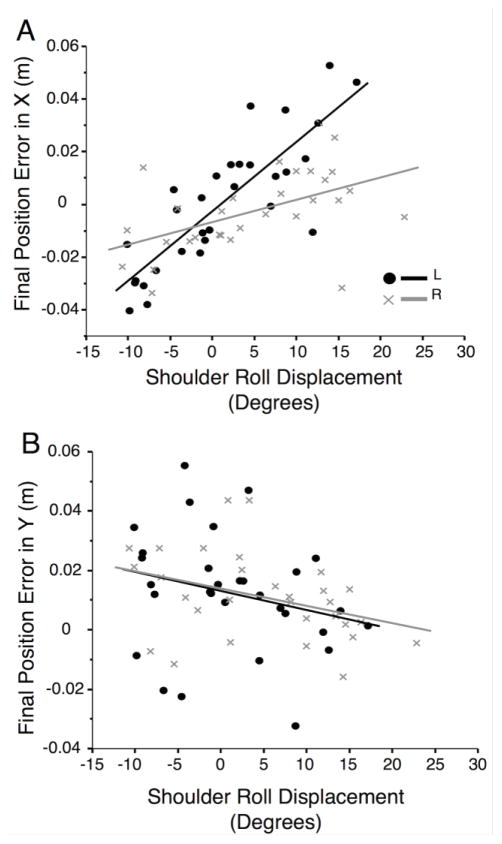

Because shoulder roll was significantly different between the arms and also appeared to be largely responsible for z-axis, or out-of-plane motion of the hand, we asked whether this displacement might be responsible for the difference between right and left arm accuracies. With the arms in this configuration, we reasoned that shoulder roll results mostly in movement in the task plane along the x-axis, but not the y-axis. Because of this we expected that shoulder roll displacement had a greater effect on errors in the x-direction than on the errors in the y-direction. Figure 6 illustrates the effect of shoulder roll displacement on x- and y- components of hand displacement errors within the horizontal plane (task-space). Figure 6a shows the relationship between shoulder roll displacement and final position errors for the X-axis component of final position errors, while figure 6b shows the relationship between shoulder roll and Y-axis components of final position errors. Whereas the dependence of Y-axis errors on shoulder roll is small (left: R2= .063, right: R2= .13), task error along the x-axis was substantially affected by shoulder roll, and this correlation was substantially larger for the left than the right arm (left: R2= .70, right: R2= .25). Using Fisher’s transformations for this relationship for each subject, and comparing the right and left arm values with Student’s t test, we found that the correlations with x dimension errors were significantly different between right and left arms (p= .0164), while y error correlations were not significantly different (p= .6445). Most importantly, however, the slope was substantially smaller for the right than the left arm, indicating a smaller dependence of x-axis error on shoulder roll for the right than the left arm. The ratio of x-error per degree of shoulder roll was 2.6 mm/degree for the left arm, but only 0.85 mm/degree for the right arm. To summarize, the right-arm showed greater shoulder roll displacement than the left arm (Figure 4b), while this displacement was associated with lower task errors.

Figure 6.

Shoulder Roll vs. X and Y Error: Linear correlations split by non-dominant left (black) and dominant right (gray) arms of A) Final position error in the x-axis vs. shoulder roll displacement (right: R2=.25, slope= .00085; left: R2= .70, slope= .0026) , and B) Final position error in the y-axis vs. shoulder roll displacement (right: R2= .13, slope= −.00058; left: R2= .063, slope= −.00064). Points represent means of one subject to one target, with left being represented by black dots and right being represented by a gray X.

Discussion

Summary

In this study, we compared dominant and non-dominant coordination during minimally constrained, 3-D reaching movements made toward multiple directions. Although the task was presented in the horizontal plane, the arms were not supported on a surface, and could move within a 30 centimeter range between two horizontal surfaces. However, any motion perpendicular to the task-plane (z-axis displacement in our coordinate system) was redundant to the task, and did not affect cursor position. Our results showed that dominant arm task performance was significantly more accurate in terms of initial direction and final position. However, hand path curvature was not significantly different between the arms. Previous studies of supported horizontal plane movements have reported more accurate initial directions and straighter trajectories for the dominant arm, but also similar or better final position accuracies between the arms (Sainburg and Kalakanis, 2000; Bagesteiro and Sainburg, 2002). Thus, our current findings for 3-D movements contrast with those findings in terms of straightness and final position errors. In terms of redundant axis motion, dominant arm movements showed greater displacements along the redundant z-axis, than did non-dominant arm movements. This z-axis motion primarily resulted from shoulder roll displacement (rotation along the long axis of the humerus). While this rotation was more constrained for the non-dominant arm, components of final position error were highly correlated with shoulder roll for the non-dominant, but not the dominant arm. This suggests that left non-dominant arm control is less effective at coordinating redundant out-of-task degrees of freedom than the right dominant-arm. As a result left arm task errors appeared to be enslaved to out-of-task displacements. We conclude that non-dominant arm movements restricted motion along the z-axis in order to constrain final position errors, while dominant arm coordination was able to take advantage of the redundant axis motion without affecting final position errors. Thus, out-of-task motion was better coordinated by the dominant arm to maintain task accuracy, while the out-of-plane motion was constrained by the non-dominant arm, and yet led to greater task errors. These findings are consistent with the proposition of a dominant controller that accounts for limb and environmental dynamics, and a non-dominant controller that stiffens to impede the effects of such dynamics on limb motion.

Our findings of greater final position accuracy for the dominant arm contrast with previous findings in planar motion. This calls into question previous conclusions that left arm/right-hemisphere specialization for impedance control leads to greater final position accuracy, in right handers. This is because the effects on final position accuracy do not appear to be robust to changes in task conditions, such as when movements are performed with visual feedback (Pzybyla et al, 2013), when only a few targets are presented (Sainburg et al., 1999), and during unsupported movements. This suggests that the greater final position accuracy sometimes reported for the non-dominant arm is an emergent property of the non-dominant controller interacting with task conditions, rather than a primary specialization. Our current findings of lower non-dominant arm displacement along the z-axis are consistent with an impedance controller that might stiffen to prevent out-of-plane motion (Yadav and Sainburg, 2014). In fact, given the finding that out of plane motion for the non-dominant arm leads to greater task errors than it does for the dominant arm, such a strategy might be critical for non-dominant arm performance.

Interlimb differences in predictive control

We measured initial direction at the peak in tangential hand velocity. This parameter is an early trajectory measure that is thought to reflect movement preparation (Flash and Hogan, 1985; Atkeson and Hollerbach, 1985; Berardelli et al., 1996; Sainburg et al., 1999). In previous studies of horizontal plane reaching movements to multiple directions, dominant arm movements consistently show substantially lower initial direction errors than non-dominant arm movements, one of the findings that has led to the idea that the dominant hemisphere is specialized for predictive control mechanisms (Sainburg and Kalakanis, 2000; Bagesteiro and Sainburg, 2002). In fact, in those planar studies, this error varied with the amplitude of interaction torques between the elbow and shoulder for the non-dominant but not the dominant arm. Similarly, early trajectory errors have been reported to be larger for the non-dominant arm in studies of 3-D motion (Hore, et al., 1996; Gray et al., 2006; Pigeon et al., 2013), and in the case of reach and turn movements, those errors were shown to vary with the amplitude of coriolis torques produced at the shoulder and elbow by trunk rotation (Pigeon et al., 2013). The idea that this type of predictive control might be associated with dominant hemisphere contributions to arm coordination has been supported by studies of ipsilesional arm movements in right-handed stroke patients with left- and right- hemisphere damage. For example, Schaefer et al., (2009) showed that lesions to the left, but not the right hemisphere produced greater variance in initial movement direction in the left, non-paretic, arm of left- hemisphere damaged but not the right non-paretic arm of patients with right-hemisphere damage. They concluded that predictive mechanisms responsible for specifying initial trajectory direction for both arms were disrupted by left, but not by right hemisphere damage. Similarly, Haaland et al. (1989) reported ipsilesional (non-paretic arm) deficits in the initial accuracy of movements for left but not right hemisphere damage, and Winstein and Pohl (1995) reported ipsilesional deficits in the timing of the initial phase of motion, prior to peak velocity, in left but not right hemisphere damaged patients. Schaefer et al. (2009) and Mutha et al. (2011) showed that left hemisphere, but not right hemisphere damage produces deficits in adaptation in initial movement direction, when participants are exposed to distorted visual feedback, in which the direction of cursor motion is rotated relative to the direction of hand motion (visuomotor rotation). Thus, the current findings, indicating a dominant arm advantage in initial direction of the hand-path is consistent with previous research indicating a dominant arm/hemisphere advantage for specifying initial trajectory parameters. The findings of hemisphere-specific deficits in stroke patients also provide evidence that asymmetries in motor performance are related to lateralized neural mechanisms that, in adults, are not easily modified with practice. A second line of research demonstrated that relatively persistent neural asymmetries underlie these performance asymmetries is that of Frey and coworkers (Philip and Frey, 2014). In this study, individuals with a right dominant arm amputation learned to use the previously non-dominant arm as their dominant controller, however improvements in function of the non-dominant arm were associated with greater activation of the ipsilateral cortex. This suggested that practice using the non-dominant arm was associated with greater access to the lateralized mechanisms in the ipsilateral hemisphere, rather than with training based modifications to the contralateral hemisphere.

However, in our current study, the initial direction advantage of the dominant arm was not associated with an advantage in movement straightness. It has previously been reported that non-dominant hand paths during pointing movements are often more curved, and that these curvatures vary with intersegmental dynamics, including inertial interaction torques (Sainburg and Kalakanis, 2000; Bagesteiro and Sainburg, 2002) as well as Coriolis torques due to motion of the trunk (Pigeon et al., 2013). Thus, the often straighter movements of the dominant arm have been shown to reflect coordination strategies that take account of limb dynamics. It should be stressed that previous studies of dominant arm movements have shown a tendency toward straight hand paths for the movements that are supported in the 2-D horizontal plane, suggesting that this is an important feature of planar reaching movements (Morasso, 1981; Flash and Hogan, 1985). Flash and Hogan (1985) proposed that the central nervous system might optimize movement smoothness, or minimize the magnitude of jerk. Other studies have associated similar straight trajectories in the horizontal plane with other optimized parameters, such as energy (Nishii and Taniai, 2009), work (Yadav and Sainburg, 2011), and torque change (Nakano et al., 1999). However, there have also been a number of studies that reported that hand paths tend to be more curved when the arm is not supported and constrained in the horizontal plane (Atkeson and Hollerbach 1985; Lacquaniti et al., 1986; Desmurget et al., 1997). Desmurget et al. directly compared dominant arm constrained and unconstrained movements in a reaching task and found that the unconstrained movements had significantly more path curvature. When participants were specifically instructed to move in a straight line, the paths became significantly straighter, suggesting that the increased curvature in unconstrained conditions was a preference, not a limitation. In a similar experiment, Lacquaniti et al. had participants follow a straight-line path to targets during unconstrained movements, also demonstrating the ability to make straight movements when instructed. They suggested that path straightness is unlikely to be an output of optimizations under 3-D conditions, in which gravitational torques and additional degrees of freedom are available (Lacquaniti et al., 1986). This might explain why large differences in path curvature have previously been reported for reaching movements constrained and supported in the horizontal plane, but were not evident in the 3-D unconstrained reaching movements reported here.

A major factor in controlling 3-D unconstrained, as compared to supported horizontal plane movements is gravitational torques. Even the kinematics of single joint movements have been shown to depend on gravitational torques (Papaxanthis et al., 2003; Gentili et al., 2007). In unconstrained mutlijoint reaching movements made by rhesus monkeys, the effects of gravitational torques dominated the trajectories (Jindrich et al., 2011). Thus, during movements made in a gravitational field, exploitation of gravitational torques can become an advantage to a controller that is able to predict dynamics. Such control might employ optimization-like algorithms to minimize costs such as energy, jerk, work, and/or task performance errors (Flash and Hogan, 1985; Nakano et al., 1999; Todorov and Jordan, 2002; Nishii and Taniai, 2009; Yadav and Sainburg, 2011). In horizontal plane reaches, straight movements are made because they are optimal according to such cost functions. We suggest that the reduced straightness of the dominant arm in the current unconstrained task may reflect control that takes advantage of gravitational torques and the additional degrees of freedom. Further research is necessary to examine whether differences in trajectory are predicted by optimization simulations for 3-D unconstrained as compared with movements supported and constrained to the horizontal plane. However, our findings that the dominant hand path shows greater excursion along the redundant degree of freedom, yet less task error associated with this excursion is consistent with this hypothesis.

Interlimb differences in coordination of redundant degrees of freedom

This task was projected into the horizontal plane, but allowed movement perpendicular to this plane, creating a purely redundant axis. Interestingly, the dominant arm showed greater excursion along this axis during movements than did the non-dominant arm. At first glance, this suggests that the non-dominant arm was better able to maintain planar motion and thus better adapt to the task. However, the non-dominant arm made greater task errors. We showed that the excursion along the z-axis was primarily due to shoulder roll displacement, or rotation of the humerus along its long axis. Shoulder roll also varied in direction for movements to different targets. This was mostly due to the kinematic requirements of the different targets. Positive shoulder roll, or external shoulder rotation, moved the hand laterally. Thus shoulder roll displacement was positive for the lateral target (Target 1). For the medial target, shoulder roll displacement was in the opposite, or negative direction. Because of orientation of the shoulder elevation angle (about 45° below the horizontal) and the flexed elbow angle, shoulder roll predominantly influenced x-axis and not y-axis excursion of the hand. Final position errors along this axis showed a higher dependence on shoulder roll for the non-dominant arm than for the dominant arm. Thus, the dominant arm showed greater shoulder roll excursion, but less effect of this motion on final position errors when compared with the non-dominant arm. This suggests that redundant degrees of freedom might be differently coordinated by the dominant and non-dominant arms. While the non-dominant arm likely stiffens to reduce excursion along potentially redundant degrees of freedom, the dominant arm utilizes greater excursion along task-irrelevant degrees of freedom, but task errors are less dependent on these excursions.

One perspective that might shed light on these interlimb differences in excursion along the redundant z-axis and associated relationship to task errors is the uncontrolled manifold hypothesis. According to this idea, redundancy in the motor system is viewed as a positive feature that allows variance without affecting task performance (Scholz and Schoner, 1999; Latash et al., 2002). Variance that does not affect task performance is said to be within an uncontrolled manifold because the controller need not be concerned with variations that do not produce performance errors (VUCM). According to the principle of motor abundance, proposed by Latash (2012), good variance is variance that does not produce task errors. This is achieved by co-variation between elemental or controlled variables, such as muscles or musculoskeletal degrees of freedom. The advantage of this ‘good’ variance is that it allows stability of performance over repetitions of a movement, as well as robustness to unexpected perturbations and variations in movement conditions. Freitas et al. (2009) reported differences in how dominant and non-dominant arm joint motions are coupled within the uncontrolled manifold. Right-handed participants reached to the same target under two conditions: 1) final location was certain or 2) there was a 66% probability that its position could jump to a new position. The results indicated that both arms increased motor abundance, or variance in the uncontrolled manifold, under the uncertain conditions. However, the non-dominant arm showed higher hand path variability, which was associated with lower ability to decouple movements in joint space. Although we did not apply uncontrolled manifold analysis in the current study, our findings that the non-dominant arm was less able to decouple shoulder roll from task errors suggests a similar deficit in coordination.

From the perspective of UCM hypothesis, variance along the z-axis may be considered “good” variance because it does not affect the task performance, whereas variance in the task plane might be considered “bad” variance. However, we did find a relationship between excursion out of the plane and task errors with both hands, albeit this dependence was greater for the non-dominant arm. Therefore, this coupling between out of task and in task motion suggests that a rigorous UCM analysis would not quantify all out of plane motion as ‘good’ variance, or variance perpendicular to the uncontrolled manifold. A similar perspective is reflected in the distinction between goal-equivalent and non-goal-equivalent manifolds proposed by Cusumano and Cesari (2006). Regardless of the approach, we suggest that dominant arm movements were able to take advantage of out-of-task motion, while maintaining low task errors to a greater extent than the non-dominant arm.

From another point of view, the greater ability of the dominant arm to take advantage of redundant degrees of freedom in order to produce accurate movements has been reported in other 3-D movement conditions. For example, Hore et al. (2005) studied dominant and non-dominant arm overhand throwing motions under different instructed speed conditions. Joint excursions in dominant arm throws were found to vary significantly when throw speed was changed, while non-dominant arm joint excursions were similar at all speeds. The non-dominant arm strategy was seen as a simple scaling technique that was less effective in generating fast and accurate throws, while the dominant arm strategy was able to exploit interaction torques at the higher speeds. In a related study, Gray et al. (2007) found, in recreational baseball players, that overarm throws with the dominant arm exploited interaction torques to a greater extent than did throws with the non-dominant arm. They proposed a greater dominant arm ability to predictively compensate for these self-generated interactions.

In the current study, shoulder joint motions for the dominant and non-dominant arms were quite different, with the dominant arm showing greater excursions that were less associated with task errors. In contrast, the non-dominant arm showed substantially less excursion along the redundant degree of freedom (z-axis). We expect that the non-dominant arm stiffened, impeding the interaction and gravitational forces that might produce accelerations along this axis, largely through co-contraction. Indeed previous research has indicated that non-dominant arm reaching motions are produced with greater coactivation of antagonist muscles than dominant arm movements (Bagesteiro and Sainburg, 2002). Heuer reported similar effects in a finger-tapping task, in which the non-dominant hand showed significantly greater co-contraction (Heuer, 2007). In both cases, this co-activation was associated with greater task errors and variability, presumably associated with less-accurate prediction of limb dynamic interactions. In the current study, we expect that reduced excursion along the z-axis was associated with greater coactivation of non-dominant arm shoulder muscles. It is plausible that the increased excursions of the dominant arm were associated with exploitation of non-muscular dynamics, including gravitational and interaction torques. However, more research is required to specifically test these predictions.

Conclusions

We compared dominant and non-dominant coordination during a multidirection reaching task that was presented in the horizontal plane, while the arm was unsupported and moved in 3-D space. Motion perpendicular to the task-plane (z-axis) was redundant to the task. Within the task plane, the dominant arm showed lower initial direction error, measured at peak tangential hand velocity. This is consistent with previous research, suggesting the dominant controller is specialized for predictive control mechanisms that account for limb and environmental dynamics. However, both arms showed similar hand path curvatures, while the dominant arm had substantially better final position accuracies, findings that are not consistent with previous studies of planar reaching movements. We suggest that the greater hand path curvatures for the dominant arm during 3-D motion may be related to differences in optimal solutions, when gravity and additional degrees of freedom are available. Indeed, previous studies have reported similar differences in hand-path curvatures during 3-D movements (Atkeson and Hollerbach, 1985; Lacquaniti et al., 1986; Desmurget et al., 1997). We also showed that components of task error were highly correlated with non-dominant arm shoulder roll, which produced hand excursions along the redundant z-axis. This was not the case for the dominant arm, which better dissociated task errors from shoulder roll excursion. We suggest that the lower redundant axis excursion of the non-dominant arm may reflect stiffening through co-activation and modulation of reflexes (Bagesteiro and Sainburg, 2002; Mutha and Sainburg, 2009). Non-dominant arm excursions along the z-axis, therefore, are likely to reflect errors in control. In contrast, the larger dominant arm excursions along the redundant axis are dissociated from task errors and might reflect a control strategy that takes advantage of gravitational torques and the additional degrees of freedom available in this minimally constrained task. These findings are consistent with the proposition of a dominant controller that is better adapted for predictive mechanisms, including specifying movement direction and accounting for limb and environmental dynamics, and a non-dominant controller that stiffens to impede the effects of such dynamics on limb motion. However, the greater final position errors of the left non-dominant arm contrast with previous findings, and suggest that the non-dominant arm is not primarily specialized for final position control, but rather that final position accuracy might be an emergent characteristic that results from the property of the controller interacting with task conditions.

Highlights.

Interlimb differences in control of 3-D unsupported reaching movements.

Dominant arm advantages for initial direction accuracy and final position accuracy.

Greater dominant arm excursion along a redundant axis, perpendicular to the plane of the task.

Non-dominant arm better impeded motion out of the task-plane, yet task errors were enslaved to this motion.

Results both support and modify the dynamic dominance hypothesis of motor lateralization.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01HD059783) to R.L.S.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Annett J, Annett M, Hudson PTW. The control of movement in the preferred and nonpreferred hands. Q J Exp Psychol-B. 1979;31:641–652. doi: 10.1080/14640747908400755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkeson CG, Hollerbach JM. Kinematic features of unrestrained vertical arm movements. J Neurosci. 1985;5:2318–2330. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-09-02318.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagestiero L, Sainburg RL. Handedness: Dominant arm advantages in control of limb dynamics. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:2408–2421. doi: 10.1152/jn.00901.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berardelli A, Hallet M, Rothwell JC, Agostino R, Manfredi M, Thompson PD, Marsden CD. Single-joint rapid arm movements in normal subjects and in patients with motor disorders. Brain. 1996;119:661–674. doi: 10.1093/brain/119.2.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein NA. A new method of mirror cyclographie and its application towards the study of labor movements during work on a workbench. Hyg Saf Pathol Labor. 1930;5:3–9. [Google Scholar]; 6:3–11. (in Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Brown SH, Cooke JD. Responses to force perturbations preceding voluntary human arm movements. Brain Res. 1981;220:350–355. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)91224-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson RG, Chua R, Elliott D, Goodman D. The contribution of vision to asymmetries in manual aiming. Neuropsychologia. 1990;28:1215–1220. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(90)90056-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusumano JP, Cesari P. Body-goal variability mapping in an aiming task. Biol Cybem. 2006;94:367–379. doi: 10.1007/s00422-006-0052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmurget M, Jordan M, Prablanc C, Jeannerod M. Constrained and unconstrained movements involve different control strategies. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:1644–1650. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.3.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dounskaia N, Wang W. A preferred pattern of joint coordination during arm movements with redundant degrees of freedom. J Neurophysiol. 2014;112:1040–1053. doi: 10.1152/jn.00082.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisk JD, Goodale MA. The effects of unilateral brain damage on visually guided reaching: hemispheric differences in the nature of deficit. Exp Brain Res. 1988;72:425–435. doi: 10.1007/BF00250264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flash T, Hogan N. The Coordination of Arm Movements: An Experimentally Confirmed Mathematical Model. J Neurosci. 1985;5:1688–1703. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-07-01688.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flowers K. Handedness and controlled movement. Brit J Psychol. 1975;66:39–52. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1975.tb01438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas SM, Scholz JP. Does hand dominance affect the use of motor abundance when reaching to uncertain targets? Hum Movement Sci. 2009;28:169–190. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentili R, Cahouet V, Papaxanthis C. Motor planning of arm movements is direction-dependent in the gravity field. Neuroscience. 2007;145:20–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon J, Ghez C. Trajectory control in targeted force impulses. III Compensatory adjustments for initial errors. Exp Brain Res. 1987;67:253–269. doi: 10.1007/BF00248547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb GL, Corcos DM, Agarwal GC. Organizing Principles for Single-Joint Movements I. A Speed-Insensitive Strategy. J Neurophysiol. 1989;62:342–357. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.62.2.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray S, Watts S, Debicki D, Hore J. Comparison of kinematics in skilled and unskilled arms of the same recreational baseball players. J Sport Sci. 2006;24:1183–1194. doi: 10.1080/02640410500497584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haaland KY, Cleeland CS, Carr D. Motor performance after unilateral hemisphere damage in patients with tumor. Arch Neurol. 1977;34:556–559. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1977.00500210058010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haaland KY, Delaney HD. Motor deficits after left or right hemisphere damage due to stroke or tumor. Neuropsychologia. 1981;19:17–27. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(81)90040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haaland KY, Harrington DL. Hemispheric control of the initial and corrective components of aiming movements. Neuropsychologia. 1989;27:961–969. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(89)90071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haaland KY, Prestopnik JL, Knight RT, Lee RR. Hemispheric asymmetries for kinematic and positional aspects of reaching. Brain. 2004;127:1145–1158. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris LJ. Side biases for holding and carrying infants: Reports from the past and possible lessons for today. Laterality. 2014;15:56–135. doi: 10.1080/13576500802584371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuer H. Control of the dominant and nondominant hand: exploitation and taming of nonmuscular forces. Exp Brain Res. 2007;178:363–373. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0747-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollerbach JM, Flash T. Dynamic interactions between limb segments during planar arm movement. Biol Cybern. 1982;44:67–77. doi: 10.1007/BF00353957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hore J, O'Brien M, Watts S. Control of joint rotations in overarm throws of different speeds made by dominant and nondominant arms. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:3975–3986. doi: 10.1152/jn.00327.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hore J, Watts S, Tweed D, Miller B. Overarm throws with the nondominant arm: Kinematics of accuracy. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:3693–3704. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.6.3693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jindrich DL, Courtine G, Liu JJ, McKay HL, Moseanko R, Bernot TJ, Roy RR, Zhong H, Tuszynski MH, Edgerton VR. Unconstrained three-dimensional reaching in Rhesus monkeys. Exp Brain Res. 2011;209:35–50. doi: 10.1007/s00221-010-2514-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latash ML. The bliss (not the problem) of motor abundance (not redundancy) Exp Brain Res. 2012;217:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s00221-012-3000-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latash ML, Scholz JP, Schoner G. Motor control strategies revealed in the structure of motor variability. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2002;30:26–31. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200201000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacquaniti F, Soechting JF, Terzuolo SA. Path constraints on point-to-point movements in three dimensional space. Neuroscience. 1986;17:313–324. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(86)90249-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morasso P. Spatial control of arm movements. Exp Brain Res. 1981;42:223–227. doi: 10.1007/BF00236911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutha PK, Sainburg RL. Shared bimanual tasks elicit bimanual reflexes during movement. J Neurophysiol. 2009;102:3142–3155. doi: 10.1152/jn.91335.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutha PK, Sainburg RL, Haaland KY. Left parietal regions are critical for adaptive visuomotor control. J Neurosci. 2011;31:6972–6981. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6432-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano E, Imamizu H, Osu R, Uno Y, Gomi H, Yoshioka T, Kawato M. Quantitative examinations of internal representations for arm trajectory planning: minimum commanded torque change model. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:2140–2155. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.5.2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishii J, Taniai Y. Evaluation of trajectory planning models for arm-reaching movements based on energy cost. Neural Comput. 2009;21:2634–2647. doi: 10.1162/neco.2009.06-08-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papaxanthis C, Pozzo T, Schieppati M. Trajectories of arm pointing movements on the sagittal plane vary with both direction and speed. Exp Brain Res. 2003;148:498–503. doi: 10.1007/s00221-002-1327-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip BA, Frey SH. Compensatory changes accompanying chronic forced use of the nondominant hand by unilateral amputees. J Neurosci. 2014;34:3622–3631. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3770-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigeon P, Dizio P, Lackner JR. Immediate compensation for variations in self-generated Coriolis torques related to body dynamics and carried objects. J Neurophysiol. 2013;110:1370–1384. doi: 10.1152/jn.00104.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przybyla A, Coelho CJ, Akpinar S, Kirazci S, Sainburg RL. Sensorimotor performance asymmetries predict hand selection. Neuroscience. 2013;228:349–360. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy EA, Elliott D. Manual asymmetries in visually directed aiming. Can J Psychology. 1986;40:109–121. doi: 10.1037/h0080087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rynkiewicz M, Starosta W. AWF Poznań and IASC Warszawa. 2011. Asymmetry of paddling technique, its selected conditions and changeability in highly advanced kayakers. [Google Scholar]

- Sainburg RL. Convergent models of handedness and brain lateralization. Front Psychol. 2014;5:1092. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainburg RL. Evidence for a dynamic-dominance hypothesis of handedness. Exp Brain Res. 2002;142:241–258. doi: 10.1007/s00221-001-0913-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainburg RL, Ghez C, Kalakanis D. Intersegmental dynamics are controlled by sequential anticipatory, error correction, and postural mechanisms. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:1045–1056. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.3.1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainburg RL, Kalakanis D. Differences in control of limb dynamics during dominant and nondominant arm reaching. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:2661–2675. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.5.2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainburg RL, Poizner H, Ghez C. Loss of proprioception produces deficits in interjoint coordination. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:2136–2147. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.5.2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainburg RL, Schaefer SY. Interlimb Differences in Control of Movement Extent. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:1374–1383. doi: 10.1152/jn.00181.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer SY, Haaland KY, Sainburg RL. Ipsilesional motor deficits following stroke reflect hemispheric specializations for movement control. Brain. 2007;130:2146–2158. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer SY, Haaland KY, Sainburg RL. Hemispheric specialization and functional impact of ipsilesional deficits in movement coordination and accuracy. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:2953–2966. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz JP, Schoner G. The uncontrolled manifold concept: identifying control variables for a functional task. Exp Brain Res. 1999;126:289–306. doi: 10.1007/s002210050738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorov E, Jordan MI. Optimal feedback control as a theory of motor coordination. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:1226–1235. doi: 10.1038/nn963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstein CJ, Pohl PS. Effects of unilateral brain damage on the control of goal-directed hand movements. Exp Brain Res. 1995;105(1):163–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00242191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodworth RS. The accuracy of voluntary movement. Psychol Rev. 1899;3:1–114. [Google Scholar]

- Wyke M. Effect of brain lesions on the rapidity of arm movement. Neurology. 1967;17:1113–20. doi: 10.1212/wnl.17.11.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav V, Sainburg RL. Motor Lateralization is characterized by a serial hybrid control scheme. Neuroscience. 2011;196:153–167. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav V, Sainburg RL. Handedness can be explained by a serial hybrid control scheme. Neuroscience. 2014;278:385–396. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]