Abstract

Meniscectomy is one of the most popular orthopaedic procedures, but long-term results are not entirely satisfactory and the concept of meniscal preservation has therefore progressed over the years. However, the meniscectomy rate remains too high even though robust scientific publications indicate the value of meniscal repair or non-removal in traumatic tears and non-operative treatment rather than meniscectomy in degenerative meniscal lesions

In traumatic tears, the first-line choice is repair or non-removal. Longitudinal vertical tears are a proper indication for repair, especially in the red-white or red-red zones. Success rate is high and cartilage preservation has been proven. Non-removal can be discussed for stable asymptomatic lateral meniscal tears in conjunction with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction. Extended indications are now recommended for some specific conditions: horizontal cleavage tears in young athletes, hidden posterior capsulo-meniscal tears in ACL injuries, radial tears and root tears.

Degenerative meniscal lesions are very common findings which can be considered as an early stage of osteoarthritis in middle-aged patients. Recent randomised studies found that arthroscopic partial meniscectomy (APM) has no superiority over non-operative treatment. Thus, non-operative treatment should be the first-line choice and APM should be considered in case of failure: three months has been accepted as a threshold in the ESSKA Meniscus Consensus Project presented in 2016. Earlier indications may be proposed in cases with considerable mechanical symptoms.

The main message remains: save the meniscus!

Cite this article: EFORT Open Rev 2017;2. DOI: 10.1302/2058-5241.2.160056. Originally published online at www.efortopenreviews.org

Keywords: knee, meniscus, meniscus repair, meniscectomy, degenerative meniscal lesions, consensus, guidelines

Introduction

If it is torn, take it out! Take it all out! Even if you just think it’s torn, take it out. Those were the slogan words by Smillie in 1967 referring to meniscal injuries.1

Fortunately, things have changed dramatically and the management of the torn meniscus is now plurally based on basic science knowledge, new diagnostic tools, technical improvements and better long-term outcome assessment:

Basic science demonstrated for a long time the crucial role of the menisci in the knee homeostasis. It also demonstrated the repairability of the meniscus thanks to the peripheral vascularity which allows a healing process.2

New diagnostic tools, first MRI and then arthroscopy, gave us a better understanding of the meniscal lesions. Saying the meniscus is torn is not sufficient. These tools show the precise tear pattern, the exact location, the extent, the associated injuries such as anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) or articular cartilage. There is not one but several meniscal tears and we have to distinguish them: traumatic tears, which can be classified as a fracture, and degenerative lesions, classified as a disease. Their management is completely different.

Technical improvements have accompanied medical advances. Arthroscopy itself was a revolution and not just a tool. It allowed better assessment and partial meniscectomy with fast recovery and low morbidity. Meniscus repair techniques improved progressively. Biological enhancers have also been proposed. But as with all revolutionary tools, arthroscopy had some adverse effects, sometimes resulting in overuse.

Assessment of the outcome remains the main important issue, rendering the indication appropriate.

A high volume of meniscectomies are carried out globally.3,4 It is one of the most popular orthopaedic procedures. But long-term results, even with arthroscopic partial meniscectomy (APM), are not so good and the concept of meniscal preservation has therefore progressed over the years:5,6. Save the meniscus! However, the meniscectomy rate remains too high even though robust scientific publications indicate the advantages of meniscal repair or non-removal in traumatic tears and non-removal rather than meniscectomy in degenerative meniscal lesions (DMLs). It is interesting to note the considerable gap between these publications and daily practice.

The reasons are numerous:

The myth: I always did this operation so it works.7

The learning curve: meniscal repair is said to be more demanding than meniscectomy. Is it true?

Patient pressure: ‘MRI shows a meniscal tear, please take it out’ or ‘Rehabilitation after repair is too long. I want to return to sport’.

The medico-economic constraints depend on healthcare systems.

The objective of this review is to describe the current management of meniscus pathology based on current literature and on the ESSKA Meniscus Consensus Project,8 which was presented in 2016.

We will distinguish between traumatic tears and DMLs. Congenital tears are excluded.

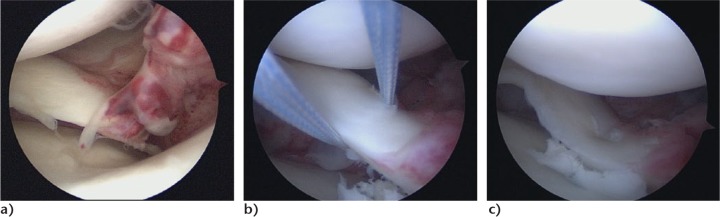

Traumatic tears

A traumatic meniscus tear is defined by the history of a sudden onset of joint-line pain generally associated with an adequate knee injury. Primarily, vertical tears such as longitudinal, radial tears, flap tears and most posterolateral root tears belong to this group. A traumatic tear can be defined as ‘stable’ or ‘unstable’ according to its mobility. It is essential to locate the tear exactly: the meniscus should be separated into circumferential zones and radial zones9 (Fig. 1). The radial zone is divided according to the vascularity into red-red, red-white or white-white zones.

Fig. 1.

Diagram showing the location of meniscus tears.

In stable knees (intact ACL), about 6% of acutely injured knees sustain a meniscus tear.10 In chronic ACL-ruptured knees, the rate of meniscal tears is very high,11 and increases with time with the medial meniscus while it remains the same with the lateral meniscus (around 20%).

In traumatic tears, mensicus preservation is the first-line choice. The reason for preserving the meniscus is, of course, the risk of secondary osteoarthritis after APM.

In stable knees, subjective results are good at more than ten-year follow-up; 85% of patients consider their knee as normal or nearly normal.12 Outcomes are usually better on the medial side. On the lateral side, the results deteriorate more rapidly with time and there is a higher rate of sports-level change.12 Iterative re-arthroscopy rate is 14% after lateral meniscectomy compared with 6% after medial meniscectomy.12 Degenerative changes are very frequent: in Société Française d’Arthroscopie’s (SFA) multi-centre trial, the prevalence of joint-line narrowing was 22% on the medial side and 38% on the lateral side at more than ten-years follow-up.12 Hulet and Seil13 observed at 20-year follow-up a 56% osteoarthritis rate in a specific population of lateral meniscectomies (Fig. 2). Other predictive factors are: amount of resection; age at surgery; and extent of articular cartilage damage. These two last factors explain why Osti et al14 reported 100% of excellent or good functional results after meniscectomy for longitudinal tears versus 79% for complex tears and why Matsusue and Thomson15 obtained 74% for excellent results after treatment for traumatic tears and 64% for degenerative tears.

Fig. 2.

Osteoarthritis 24 years after arthroscopic bimeniscectomy in a stable knee.

In the ACL-deficient knee, isolated meniscectomy is very detrimental with a near 100% osteoarthritis rate at more than 30 years.16

Meniscectomy in conjunction with ACL reconstruction is also a factor in causation of secondary osteoarthritis.17 In their multi-centre study reporting long-term outcomes of 675 ACL reconstructions, Hulet and Graveleau18 demonstrated an osteoarthritis rate of 29% in the medial meniscectomy group compared with 10% in the intact meniscus group.

Longitudinal tears

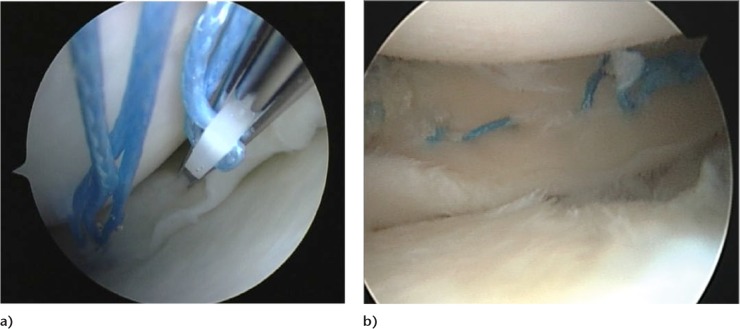

Meniscus repair outcomes (with or without ACL tear) are now well-established. For vertical peripheral longitudinal tears, the rate of failure is acceptable (6% to 28%).19 Repaired tears in the red-red or red-white zones lead to excellent and good clinical mid-term results (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Vertical longitudinal tear. Repair using all-inside device (FasT-Fix, Smith & Nephew): a) intra-operative view; b) final stage.

The anterior-to-posterior location does not play a role in surgical outcome20 but the literature is unclear as to whether the length of a longitudinal meniscus tear influences the success of repair.21 Thus, length of meniscus tear should not be a reason against repair. Take the risk of failure and if it fails, the amount of secondary resection will not be higher than the primary virtual meniscectomy.22

In the same way, timing influences outcomes: a repair as early as possible is better. In general, acutely repaired meniscus tears achieve superior results compared with chronically repaired tears.23 However, repaired chronic meniscus tears also achieve good to excellent results and thus should be repaired—when indicated—instead of resected.

The patient’s age does not play a role in the failure rate, provided tears are really traumatic.6,24

Long-term comparative studies and meta-analyses with APM have demonstrated the superiority of meniscus repair in terms of function, return to sports and cartilage protection.25-28

Meniscus preservation is particularly important in ACL-injured knees. Meniscus preservation (repair or non-removal) in combination with ACL reconstruction protects the articular cartilage, and the ACL graft, reducing the residual laxity. ACL reconstruction also protects the meniscus repair.

A Bucket-handle tear with ACL injury is a particular situation. A chronic ACL tear, associated with an acute locked knee, should be treated by prompt repair of the meniscus and simultaneous ACL reconstruction. In an acute or subacute ACL tear with locked knee, the best choice is a two-stage procedure, starting with a meniscus repair and then reconstructing the ACL in the chronic phase. A one-stage procedure can be reasonably proposed in a very acute phase (less than 60 hrs).

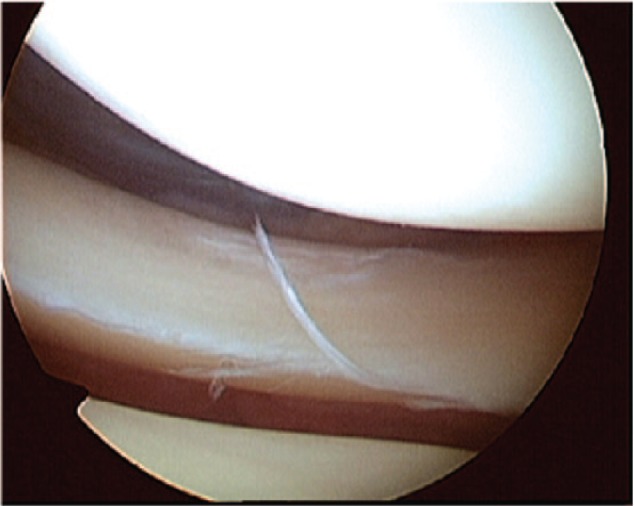

Non-removal of meniscus tears at the time of ACL reconstruction has been proposed. Lateral meniscus tears have a better prognosis in terms of secondary meniscectomy compared with medial meniscus tears left in situ. In their systematic review, Pujol and Beaufils29 included 15 studies with 843 lateral tears and 642 medial tears out of 1485 untreated meniscal tears with concomitant ACL reconstruction. The failure rate was 0 to 1.5% for lateral small (< 1 cm) tears (Fig. 4), 0% to 7% for larger lateral meniscus tears and up to 15% for medial meniscus tears. However, the exact definition of instability of a lesion has not been clearly defined and the problem of finding correct criteria (e.g. size of lesion and measurable abnormal mobility of the meniscus) remains unsolved. Regarding the risk of secondary meniscectomy, indications for surgical repair can be widened for the medial meniscus and non-removal proposed for the lateral meniscus.30.

Fig. 4.

Small lateral meniscus tear in conjunction with an anterior cruciate ligament injury.

Is there still a place for meniscectomy in traumatic longitudinal tears? For sure, yes, but in very selected cases and only when preservation techniques are not suitable. We can cite as examples:

Symptomatic complex tears with damaged meniscal tissue.

Rare symptomatic non-reparable meniscal tears in middle-aged patients with non-symptomatic ACL injury, justifying an isolated meniscectomy.

Proposing a meniscectomy in a young active patient, with the sole pretext that recovery will be more rapid compared with repair, is not acceptable despite the patient and societal pressure and the medico-economic constraints.

Extended indications

Good results after repair in longitudinal tears and the proven capacity to protect the cartilage has led to an extension of the indications to other types of traumatic tears apparently less suitable for preservation. To improve the outcomes which are related to the healing process, some biological enhancers have been proposed.

Meniscus needling and opening the medullary cavity should be avoided. Fibrin glue or fibrin clot can only be weakly recommended, due to a lack of validated studies. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) use is controversial: one study did not show any improvement compared with isolated meniscus repairs.31 Pujol et al32 did demonstrate improvement with the specific indication of horizontal cleavages in athletes. Local application of cells has not been studied with a robustly designed trial yet.

Horizontal cleavage in young athletes

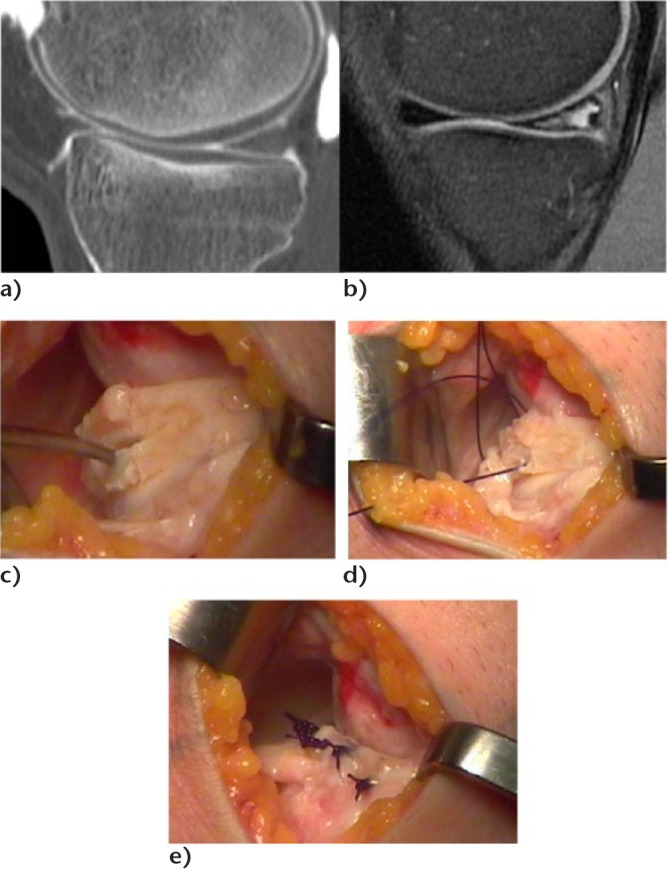

Horizontal cleavage in young athletes is a rare specific condition which can be regarded as an overuse micro-traumatic lesion in stable knees, even if histological samples demonstrate some mucoid degenerative tissue. When functional treatment fails, meniscus repair can be considered. Pujol et al33 proposed an open approach. Meniscus repair is performed with vertical sutures (Fig. 5). Injection of PRP could enhance the healing process. Preliminary results are encouraging demonstrating better results in terms of functional scores and rate of failure (secondary meniscectomy).32 Again, this treatment has to be compared with a meniscectomy which is subtotal and which would provoke early advanced osteoarthritis, especially on the lateral side. ‘Take the risk of failure!’

Fig. 5.

Horizontal cleavage tear in a young athlete (medial meniscus): a,b) CT scan and MRI of the same knee. The CT scan shows a normal pattern of the meniscus while the MRI shows a grade 2 lesion; c) posteromedial open repair with release of the menisco-synovial junction showing the cleavage which is debrided with curettes; d) the cleavage is closed using vertical sutures (PDS 0, Ethicon); e) final aspect after closure of the menisco-synovial junction.

Radial tears

A radial meniscus tear causes complete loss of meniscus function, if it extends to the peripheral zone.

Thus, radial tears of the red and red-white zones should be repaired in order to restore integrity of the rim.34 This is true for patients with or without concomitant ACL reconstruction. Only in cases when the tear is technically not repairable or there is re-tear of a failed repair should meniscectomy be considered. In contrast, radial tears in the white-white zone can be treated by partial meniscectomy, preserving the peripheral wall.

Posterior menisco-capsular tears in conjunction with ACL injuries

Posterior menisco-capsular or even intracapsular lesions have been described in conjunction with ACL tears, especially on the medial side. The natural history is not well-known, but the risk of extension of the tear and the low morbidity of meniscus repair are strong arguments for a repair during ACL reconstruction. It needs an arthroscopic assessment of the posterior compartment to recognise the tear and repair it using a hook.35

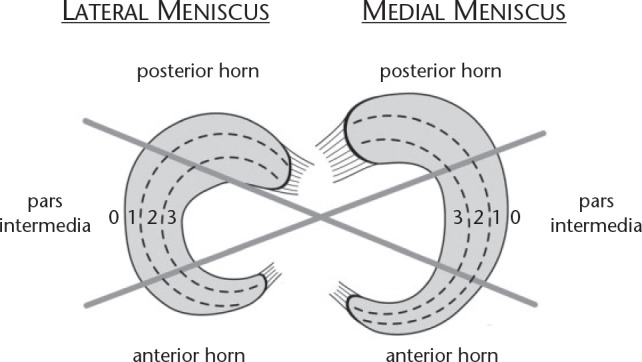

Root tears

Root tears are frequent when far-posterior degenerate meniscal lesions are included in this group. True traumatic root avulsions are rare, frequently associated with ACL tears, and mainly located on the lateral side. These meniscal tears correspond to a total functional meniscectomy. Traumatic meniscus root tears should be repaired, especially if the meniscofemoral ligament is torn.36 Repair is carried out by trans-osseous tibial re-insertion (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

a) Acute traumatic posterior medial root tear; b) sutures are passed through the meniscus using a hook; c) trans-tibial fixation.

Degenerative meniscal lesions

This section is largely based on the conclusions of the 2016 ESSKA Meniscus Consensus Project8 whose necessity was indicated after the publication of several randomised controls trials (RCTs) followed by extensive discussions.37

A DML can be defined as a slowly developing lesion, typically involving a horizontal cleavage of the meniscus in a middle-aged or older person (Fig. 7). The most common location is the posterior horn of the medial meniscus. Such meniscus lesions are frequent in the general population with or without symptoms. The prevalence increases with age, ranging from 16% in the knees of women aged 50 to 59 years to over 50% in the knees of men aged 70 to 90 years.38 These epidemiological data are important from two aspects: first, they demonstrate the remarkably high prevalence of meniscus lesions in the general population which may be considered part of normal ageing. Second, most of these meniscus lesions do not directly cause knee symptoms as over 60% of tears were completely pain-free.

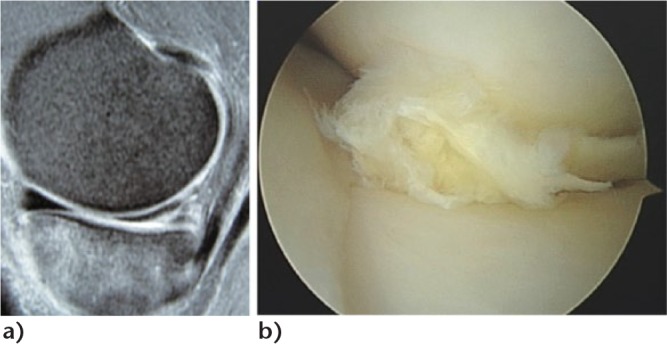

Fig. 7.

Degenerative medial meniscal lesion: a) typical grade 3 MRI pattern; b) arthroscopic findings.

MRI of these lesions will identify a linear intra-meniscal signal,39 often communicating with the articular surface. Such hypersignal indicates ongoing mucoid degenerative changes. The only longitudinal (natural history) study with repeat MRI capturing the development of meniscus lesions in middle-aged persons reported that only 1 of 43 ‘incident’ meniscus tears was associated with acute knee trauma.39 Instead, it is a slowly developing process (over several years). Loss of meniscus function may negatively affect the knee in the long term. Therefore, in many people a DML is a feature indicative of a knee joint with (or at increased risk of) developing osteoarthritis.

Diagnosis

There is a strong need for accurate diagnosis based on clinical examination and eventually radiographs and MRI. This should answer the following questions:

- What is the cause of pain or mechanical symptoms?

- Is there any sign of advanced osteoarthritis?

- Is the DML related to the pain?

The clinical diagnosis of osteoarthritis and/or DML can be made typically on the basis of the duration and character of the knee-joint symptoms, patient history and findings from clinical examination.

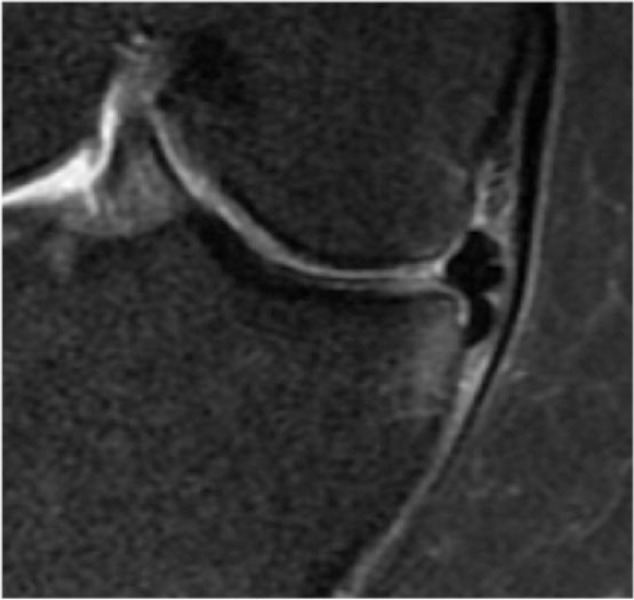

Does an unstable DML cause knee symptoms? While there is limited support in the literature that DMLs are considered to be unstable, e.g. flap tears are truly causing knee symptoms, it is still possible that, in some patients, torn meniscus fragments from the DML (by its displacement) may cause knee-joint symptoms (Fig. 8) and particularly mechanical symptoms such as clicking or briefly locking knees.

Fig. 8.

Degenerative meniscus lesion: flap dislocated in the tibial gutter causing mechanical symptoms.

What is the place of standard radiographs? In the orthopaedic setting, weight-bearing semi-flexed knee radiographs should be included in the work-up of the middle-aged or older patient with knee pain. Joint-line narrowing means advanced osteoarthritis. A skyline patellar view is also important for the detection of radiographic evidence of patella-femoral osteoarthritis.

Knee MRI is typically not indicated in the first-line work-up of the middle-aged or older patients with knee-joint symptoms. MRI captures an incredible amount of tissue change, but today there is very limited knowledge of how to differentiate normal ageing processes from pathological ones and where does, for example, the osteoarthritic processes fit in?40

However, knee MRI may be indicated in selected patients with refractory symptoms or in the presence of symptoms indicating a rarer disease that needs to be ruled out, e.g. osteonecrosis. Hence, if a surgical indication is considered, based on history, symptoms, clinical examination and knee radiography, knee MRI may be useful to identify structural knee pathologies that may (or may not) be relevant for the symptoms.

Management

APM is a very frequent procedure in the DML field and its incidence is even growing in some countries.4 The success rate is, of course, high, even in DML6 in terms of symptomatic relief and return to daily activities and sports.41 Pooled results of Salata’s systematic review42 demonstrated that total meniscectomy or removal of the peripheral meniscal rim, lateral meniscectomy, degenerative meniscal tears, presence of chondral damage, presence of hand osteoarthritis suggestive of a genetic predisposition and increased body mass index were all independent risk factors for poor clinical and radiological outcomes after arthroscopic menisectomy.

Complications are rare (0.27% to 2.8%): Salzler et al43 found a 2.8% complication rate after APM and concluded that knee arthroscopy is not a benign procedure: deep vein thrombosis, complex regional syndrome, infection, rapid chondrolysis especially on the lateral side, may follow.44

Last, but not least, patients treated with APM present a higher risk for symptomatic knee osteoarthritis compared with normal healthy knees.

Considering these results since 2002, several RCTs attempted to compare APM with non-operative treatment (mainly physiotherapy)45-49 or sham surgery.50,51 Moseley50 and Kirkley’s45 studies were based on osteoarthritic knees, the other ones on knees without advanced osteoarthritis. Apart from Gauffin et al,49 they all found APM had no benefit over non-operative treatment at a short- or mid-term follow-up, whatever the status of the cartilage. Thorlund et al,52 in their meta-analysis, confirmed these results.

Publication of these studies introduced a large controversy in the orthopaedic world.53,54 We must be aware that these RCTs, as good as they are, have their biases and weaknesses, and conclusions must be read and interpreted with a critical scientific mind. But these RCTs exist and deliver three important messages:

- APM has no superiority over non-operative treatment.

- The rate of conversion from non-operative treatment to arthroscopic surgery varies from 0% to 35%. This cross-over rate has to be compared with the rate of APM failure.

- Presence of mechanical symptoms does not seem to modify these outcomes,51 but mechanical symptoms are not well-defined and further investigations are needed.

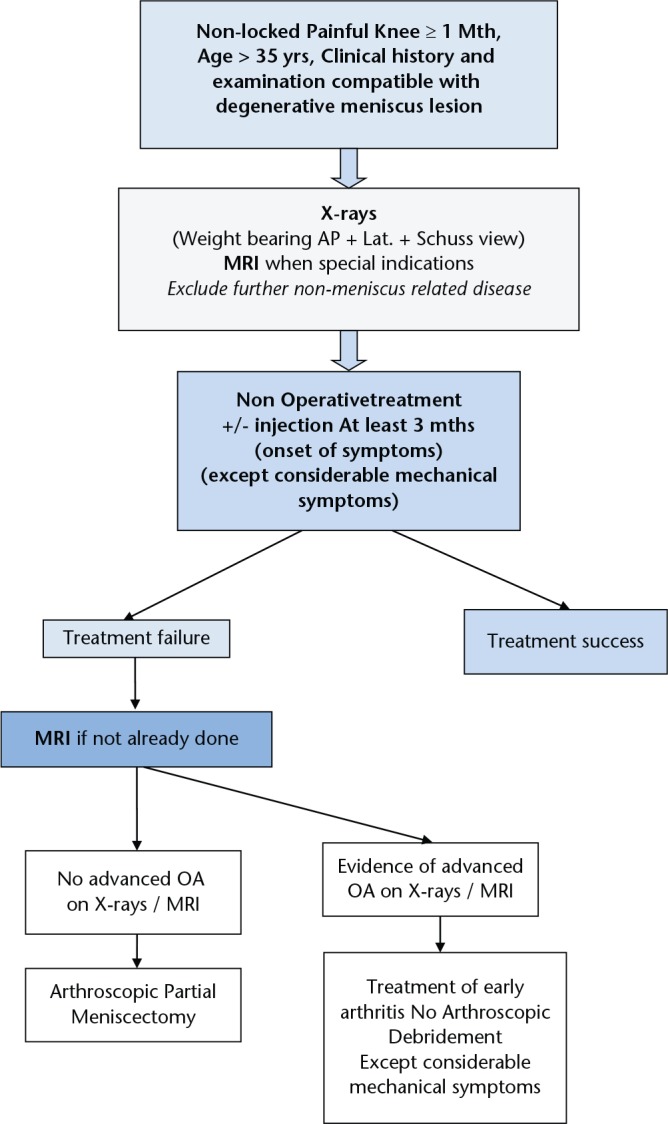

Starting from these findings, the ESSKA Meniscus Consensus Project8 proposed an algorithm (Fig. 9) in which ESSKA stated as the main messages:

Fig. 9.

Degenerative meniscus lesion. Algorithm proposed by the ESSKA Meniscus Consensus Project.8 AP, anteroposterior; LAT, lateral; OA, osteoarthritis.

APM should not be considered as the first-line treatment choice.

APM should only be proposed after a proper standardised imaging protocol.

APM can be proposed after three months of persistent pain/mechanical symptoms or earlier in case of considerable mechanical symptoms.

No APM should be proposed with advanced osteoarthritis on Schuss view.

It is definitely time to change the paradigm in meniscus management. Meniscectomy should never be the first-line choice. Meniscus repair in traumatic tears and non-operative treatment in DMLs are the first answers.

However, changing the paradigm not only depends on robust scientific evidence but also on continuous education, informing general practitioners, radiologists, the patients and last, but not least, on altering the medico-economic environment.

Footnotes

ICMJE Conflict of Interest Statement: PB: Occasional Education Consultant for Zimmer/Biomet, and Smith & Nephew. Editor in Chief of Orthopaedics and Traumatology: Surgery and Research

RB: Deputy Editor of Knee Surgery Sports Traumatology and Arthroscopy, Education Consultant for Mathys, Wolf

SK: web-editor of Knee Surgery Sports Traumatology and Arthroscopy

MO: No conflict with this article

NP: Occasional Education Consultant for Smith & Nephew, Zimmer/Biomet

Funding statement

The author or one or more of the authors have received or will receive benefits for personal or professional use from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

References

- 1. Smillie IS. The current pattern of internal derangements of the knee joint relative to the menisci. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1967;51:117-122 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arnoczky SP, Warren RF. The microvasculature of the meniscus and its response to injury. An experimental study in the dog. Am J Sports Med 1983;11:131-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.No authors listed. Agence Technique de l’Information sur l’Hospitalisation (ATIH). http://www.atih.sante.fr/mco/presentation?secteur=MCO (date last accessed 4 January 2017). (In French)

- 4. Thorlund JB, Hare KB, Lohmander LS. Large increase in arthroscopic meniscus surgery in the middle-aged and older population in Denmark from 2000 to 2011. Acta Orthop 2014;85:287-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaufils P, Hulet C, Dhénain M, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of meniscal lesions and isolated lesions of the anterior cruciate ligament of the knee in adults. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2009;95:437-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Seil R, Becker R. Time for a paradigm change in meniscal repair: save the meniscus! Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2016;24:1421-1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aspenberg P. Mythbusting in orthopedics challenges our desire for meaning. Acta Orthop 2014;85:547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Beaufils P, Becker R, Kopf S, et al. Surgical management of degenerative meniscus lesions the 2016 ESSKA meniscus consensus Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2017. DOI: 10.1007/s00167-016-4407-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cooper DE, Arnoczky SP, Warren RF. Meniscal repair. Clin Sports Med 1991;10:529-548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Maffulli N, Binfield PM, King JB, Good CJ. Acute haemarthrosis of the knee in athletes. A prospective study of 106 cases. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1993;75-B:945-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gadeyne S, Besse JL, Galand-Desme S, Lerat JL, Moyen B. [Analysis of meniscal lesions accompanying anterior cruciate ligament tears: A retrospective analysis of 156 patients]. Rev Chir Orthop Repar Appar Mot 2006;92:448-454. (In French) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chatain F, Adeleine P, Chambat P, Neyret P; Société Française d’Arthroscopie. A comparative study of medial versus lateral arthroscopic partial meniscectomy on stable knees: 10-year minimum follow-up. Arthroscopy 2003;19:842-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hulet C, Menetrey J, Beaufils P, et al. ; French Arthroscopic Society (SFA). Clinical and radiographic results of arthroscopic partial lateral meniscectomies in stable knees with a minimum follow up of 20 years. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015;23:225-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Osti L, Liu SH, Raskin A, Merlo F, Bocchi L. Partial lateral meniscectomy in athletes. Arthroscopy 1994;10:424-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Matsusue Y, Thomson NL. Arthroscopic partial medial meniscectomy in patients over 40 years old: a 5- to 11-year follow-up study. Arthroscopy 1996;12:39-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Neyret P, Donell ST, Dejour H. Results of partial meniscectomy related to the state of the anterior cruciate ligament. Review at 20 to 35 years. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1993;75-B:36-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aglietti P, Buzzi R, Bassi PB. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy in the anterior cruciate deficient knee. Am J Sports Med 1988;16:597-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cantin O, Lustig S, Rongieras F, et al. ; Française de Chirurgie Orthopédique et Traumatologique. Outcome of cartilage at 12 years of follow-up after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2016;102:857-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pujol N, Lorbach O. Meniscal repair: Results. In: Hulet C, Pereira H, Peretti G, Denti M, eds. Surgery of the Meniscus. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Verlag, 2016:343-355. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Westermann RW, Wright RW, Spindler KP, Huston LJ, Wolf BR; MOON Knee Group. Meniscal repair with concurrent anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: operative success and patient outcomes at 6-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med 2014;42:2184-2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Spindler KP, Huston LJ, Wright RW, et al. ; MOON Group. The prognosis and predictors of sports function and activity at minimum 6 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a population cohort study. Am J Sports Med 2011;39:348-359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pujol N, Barbier O, Boisrenoult P, Beaufils P. Amount of meniscal resection after failed meniscal repair. Am J Sports Med 2011;39:1648-1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Venkatachalam S, Godsiff SP, Harding ML. Review of the clinical results of arthroscopic meniscal repair. Knee 2001;8:129-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ahn JH, Lee YS, Yoo JC, et al. Clinical and second-look arthroscopic evaluation of repaired medial meniscus in anterior cruciate ligament-reconstructed knees. Am J Sports Med 2010;38:472-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nepple JJ, Dunn WR, Wright RW. Meniscal repair outcomes at greater than five years: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 2012;94-A:2222-2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Paxton ES, Stock MV, Brophy RH. Meniscal repair versus partial meniscectomy: a systematic review comparing reoperation rates and clinical outcomes. Arthroscopy 2011;27:1275-1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stein T, Mehling AP, Welsch F, von Eisenhart-Rothe R, Jäger A. Long-term outcome after arthroscopic meniscal repair versus arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for traumatic meniscal tears. Am J Sports Med 2010;38:1542-1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pujol N, Tardy N, Boisrenoult P, Beaufils P. Long-term outcomes of all-inside meniscal repair. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015;23:219-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pujol N, Beaufils P. During ACL reconstruction, small asymptomatic lesions can be left untreated. A systematic review JISAKOS 2016. 0 1-6 doi 10.1136jisakos-2016-000051. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shelbourne KD, Heinrich J. The long-term evaluation of lateral meniscus tears left in situ at the time of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 2004;20:346-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Griffin JW, Hadeed MM, Werner BC, et al. Platelet-rich plasma in meniscal repair: does augmentation improve surgical outcomes? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015;473:1665-1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pujol N, Salle De, Chou E, Boisrenoult P, Beaufils P. Platelet-rich plasma for open meniscal repair in young patients: any benefit? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015;23:51-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pujol N, Bohu Y, Boisrenoult P, Macdes A, Beaufils P. Clinical outcomes of open meniscal repair of horizontal meniscal tears in young patients. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013;21:1530-1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ra HJ, Ha JK, Jang SH, Lee DW, Kim JG. Arthroscopic inside-out repair of complete radial tears of the meniscus with a fibrin clot. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013;21:2126-2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sonnery-Cottet B, Conteduca J, Thaunat M, Gunepin FX, Seil R. Hidden lesions of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus: a systematic arthroscopic exploration of the concealed portion of the knee. Am J Sports Med 2014;42:921-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ahn JH, Yoo JC, Lee SH. Posterior horn tears: all-inside suture repair. Clin Sports Med 2012;31:113-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Beaufils P, Becker R, Verdonk R, Aagaard H, Karlsson J. Focusing on results after meniscus surgery. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015;23:3-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Englund M, Guermazi A, Gale D, et al. Incidental meniscal findings on knee MRI in middle-aged and elderly persons. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1108-1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kumm J, Turkiewicz A, Guermazi A, Roemer F, Englund M. Natural history of intrameniscal signal on knee magnetic resonance imaging: six years of data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Radiology 2016;278:164-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hunter DJ, Arden N, Conaghan PG, et al. ; OARSI OA Imaging Working Group. Definition of osteoarthritis on MRI: results of a Delphi exercise. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011;19:963-969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Khan M, Evaniew N, Bedi A, Ayeni OR, Bhandari M. Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative tears of the meniscus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2014;186:1057-1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Salata MJ, Gibbs AE, Sekiya JK. A systematic review of clinical outcomes in patients undergoing meniscectomy. Am J Sports Med 2010;38:1907-1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Salzler MJ, Lin A, Miller CD, et al. Complications after arthroscopic knee surgery. Am J Sports Med 2014;42:292-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Charrois O, Ayral X, Beaufils P. [Rapid Chondrolysis after arthroscopic lateral meniscectomy Report of 4 cases]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot 1998;84:89-92. (In French) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kirkley A, Birmingham TB, Litchfield RB, et al. A randomized trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1097-1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Herrlin SV, Wange PO, Lapidus G, et al. Is arthroscopic surgery beneficial in treating non-traumatic, degenerative medial meniscal tears? A five year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013;21:358-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Katz JN, Brophy RH, Chaisson CE, et al. Surgery versus physical therapy for a meniscal tear and osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1675-1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yim JH, Seon JK, Song EK, et al. A comparative study of meniscectomy and nonoperative treatment for degenerative horizontal tears of the medial meniscus. Am J Sports Med 2013;41:1565-1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gauffin H, Tagesson S, Meunier A, Magnusson H, Kvist J. Knee arthroscopic surgery is beneficial to middle-aged patients with meniscal symptoms: a prospective, randomised, single-blinded study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014;22:1808-1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Moseley JB, O’Malley K, Petersen NJ, et al. A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med 2002;347:81-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, et al. ; Finnish Degenerative Meniscal Lesion Study (FIDELITY) Group. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear. N Engl J Med 2013;369:2515-2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Thorlund JB, Juhl CB, Roos EM, Lohmander LS. Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee: systematic review and meta-analysis of benefits and harms. BMJ 2015;350:h2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bollen SR. Is arthroscopy of the knee completely useless? Meta-analysis–a reviewer’s nightmare. Bone Joint J 2015;97-B:1591-1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Elattrache N, Lattermann C, Hannon M, Cole B. New England Journal of Medicine article evaluating the usefulness of meniscectomy is flawed. Arthroscopy 2014;30:542-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]