Abstract

Intestinal IgA+ B cells are generated from IgM+ B cells by in situ class switching in two separate gut microenvironments: organized follicular structures and lamina propria (LP). However, the origin of IgM+ B cells in the gut LP is unknown. Transfer experiments to reconstitute IgM+ B cells and IgA plasma cells in LP of aly/aly mice, which are defective in all organized follicular structures because of an NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK) mutation, revealed that naïve B cells can directly migrate to the LP. This migration requires NIK-dependent activation of gut stromal cells. By contrast, the entry of gut-primed IgM+ B cells to the LP is independent of stromal cells with functional NIK. Our results indicate that naïve B cells directly migrate to the LP by a distinct pathway from gut-primed B cells.

Keywords: gut stromal cells, IgA, migration, NF-κB

Organized follicular structures in the gut, such as Peyer's patches (PPs), provide microenvironments in which IgM+ B cells efficiently differentiate to IgA+ B cells and acquire a gut-selective homing (1, 2). This selective migration to gut is achieved through down-regulation of L-selectin and strong induction of integrin α4β7, which allows a preferential interaction with vascular addressin molecule MadCAM-1 expressed by postcapillary venules in the gut lamina propria (LP) (2). It has been proposed that the majority of IgA plasma cells present in the gut are derived from IgA+ B cells generated in PPs that, through the lymphatic and vascular systems, home preferentially to the LP of the small intestine (1, 2).

However, retinoic acid-related orphan receptor γt-/- mice or bone marrow (BM)-reconstituted LTα-/- or TNF-LTα-/- mice, lacking PPs, mesenteric lymph nodes, or any other gut follicular structures such as isolated lymphoid follicles (ILFs), do have B220+IgM+B cells and B220-IgA+ plasma cells in the intestine, indicating that B cells are able to migrate directly to the LP in the absence of preactivation in organized lymphoid tissues of the gut (3–5). Furthermore, B220+IgM+ cells can generate B220+IgA+ B cells by in situ switching in the LP, under the influence of TGF-β secreted by LP stromal cells (6). This result is demonstrated by the presence of LP B cells that express molecular markers for ongoing class-switch recombination (CSR) such as α-germ-line transcripts, activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) (7), and the short-lived α-circle transcripts generated from the circular DNA excised from chromosome by CSR (6, 8). Further differentiation of B220+IgA+ B cells to B220-IgA+ plasma cells is supported by LP stromal cells, through production of cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-10 (6).

In contrast to mutant mice that maintain normal levels of intestinal IgA, despite the complete absence of the gut-organized follicular structures, alymphoplasia (aly/aly) mice lacking PPs, ILFs, and lymph nodes are completely devoid of IgA plasma cells in the gut (9–11). The aly/aly phenotype is due to a point mutation in NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK), known to be involved in both canonical and alternative pathway of NF-κB activation that impairs functions in both lymphocytes and stromal compartments (9, 12–14). Indeed, aly/aly peritoneal B1 cells have intrinsic defects that prevent their migration out of the peritoneal cavity, and stromal cells of aly/aly mice have impaired capacity to secrete lymphoid chemokine, such as BLC/CXCL13 and SLC/CCL21, which are important for the development and organization of secondary lymphoid organs (11, 15).

We found that the gut IgA deficiency in aly/aly mice can be rescued by injection of PP cells but not by transfer of BM cells. Coinjection of BM and LP cells into irradiated aly/aly mice also rescued IgA synthesis because of migration of LP stromal cells to the aly gut, which was essential to recruit BM-derived B220+IgM+ B cells and to subsequent generation of B220-IgA+ plasma cells in situ in the LP. These results indicate that the recruitment of naïve, but not gut-primed, B cells to LP depends on the presence of gut-specific stromal cells with a functional NIK.

Methods

Mice. aly/NscJcl-aly/aly and aly/NscJcl-aly/+ (purchased from Clea, Osaka), and RAG-2-/- and GFP transgenic (Tg) mice on a C57BL/6 background were maintained in Kyoto University's animal facility in specific pathogen-free conditions. Parabiosis surgery was performed in accordance with the guidelines established by the Institute of Laboratory Animals of Kyoto University. For transfer experiments, 1 × 107 cells isolated from BM of GFP Tg mice or wild-type mice were injected into lethally irradiated aly/aly mice through the retroorbital plexus. Total PP cells (2 × 107) or IgA-depleted PP from GFP Tg mice and total LP cells (2 × 107) from GFP Tg mice or RAG-2-/- mice were coinjected i.p. with 1 × 107 BM cells i.v. into lethally irradiated aly/aly mice. After the operation or cell transplantation, mice were given 500 mg/liter ampicillin (Sigma) and 1g/liter neomycin (Nacalai Tesque) in drinking water for 6 days.

Immunohistochemical Examinations. Tissue sample from spleen or small intestine were frozen in Tissue-Tek OCT compound (Sakura Finetechnical). Sections (7-μm thick) were prepared and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 min. Fluorescence of transplanted cells from GFP Tg mice was lost during drying/fixation steps (unless mice were perfused and tissues were fixed in PFA). The following reagents were used for stainings: biotin anti-IgM (Cappel), FITC anti-IgA, CD21, CD4 (Pharmingen), streptavidin-Texas red (GIBCO/BRL). The sections were mounted in Slow Fade (Molecular Probes). Slides were analyzed with a Leica model DMRXA2 confocal laser-scanning microscope.

Flow Cytometric Analysis. The following antibodies were used for staining: APC anti-mouse B220 (Pharmingen), phycoerythrin (PE) anti-IgM, IgA (Southern Biotechnology Associates). Biotinylated peanut agglutinin was from Vector Laboratories and APC or PE-streptavidin were from Biomeda. All analyses were performed on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson). We performed PP or LP cell preparations and magnetic sorting as described (6).

RT-Quantitative (q)PCR. Total RNA was isolated from duodenum and ileum fragments by using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Tokyo). After spectrometric analysis, equal amounts of RNA from each section were pooled before cDNA synthesis. After DNase treatment, oligo dT primers were used for first cDNA synthesis (reverse transcription), all procedures were performed according to manufacturers instructions (Invitrogen). qPCR was performed on an iCycler thermal cycler, by using Sybr green supermix or iTaq products according to instructions, and analyzed by accompanying software (all from Bio-Rad). Except for GAPDH, Iμ-Cα, and CCL25, all other primers and probe were determined by using beacon designer v2.1 (Premier Biosoft International, Palo Alto, CA). Sequences were as follows: Gapdh, forward (f) 5′-TGTGTCCGTCGTGGATCTGA and reverse (r) 5′-CCTGCTTCACCACCTTCTTGAT; CXCL12, f 5′-AAGGTCGTCGCCGTGCTG and r 5′-GATGCTTGACGTTGGCTCTGG; CCL25, f 5′-AGGTGCCTTTGAAGACTGCT and r 5′-TCACCATCCTGGGATGACCT; MAdCAM-1, f 5′-GAGCAAGAAGAGGAGATACAAGAG and r 5′-TGGTGACCTGGCAGTGAAG; CD19, f 5′-CAGTTGGCAGGATGATGGACTTC and r 5′-CTGAATTGAGTGGAGCTGAGGAG; Iμ, f 5′-CTCTGGCCCTGCTTATTGTTG; Cα, r 5′-GAGCTGGTGGGAGTGTCAGTG; AID, f 5′-CGTGGTGAAGAGGAGAGATAGTG and r 5′-CAGTCTGAGATGTAGCGTAGGAA; and AID Taqman probe: 5′-(Hex)CACCTCCTGCTCACTGGACTTCGGC-(Tamra)-phosphate. Starting quantity of cDNA was 32 or 64 ng RNA equivalent for samples obtained from parabiotic mice, and 48 ng RNA equivalent for samples obtained from aly/aly and wild-type mice. Optimized final primer concentrations ranged from 150 to 300 nM, and reactions were run for 4 min at 95°C, followed by 35 cycles of 20 sec at 60°C (62°C for CCL25), 20 sec at 70°C, and 15 sec at 95°C. A serial diluted positive control (bulk cDNA), and reverse transcription minus controls of each tested sample were included in each PCR. Specificity of PCR products was initially confirmed by sequence analysis and then by melt-curve analysis.

For PCRs with AID probe, start quantity of cDNA was 160 ng, and primer and probe concentrations were 300 and 250 nM, respectively. PCR protocol was same as described above, with the number of cycles being 45. Specificity of reaction was confirmed after sequencing of PCR products. All qPCRs were repeated two to four times, with at least two different preparations of cDNA.

Results

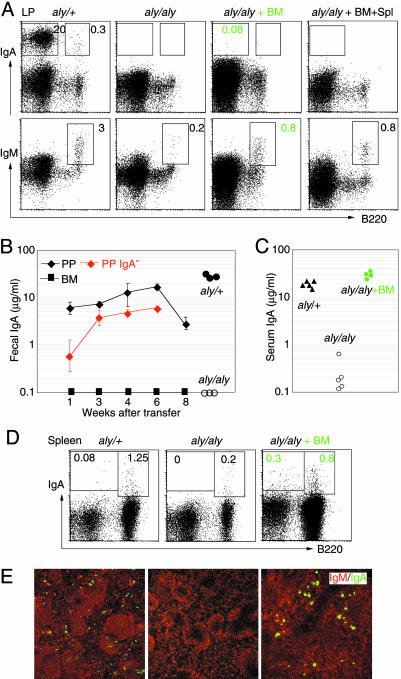

BM Cell Injection Rescues Serum but Not Gut IgA in aly/aly Mice. Compared with wild-type or aly/+ mice, aly/aly mice had no B220-IgA+ plasma cells, and a few, if any, B220+IgM+ B cells in the LP of the small intestine (Fig. 1A). Accordingly, the fecal IgA levels were undetectable in aly/aly mice (Fig. 1B). We first tried to rescue IgA synthesis in aly/aly LP by transfer of BM cells (the results from aly/aly reconstitution experiments are summarized in Table 1). Reconstitution of aly/aly mice by BM transplantation failed to recover B220-IgA+ plasma cells in the LP and fecal IgA (Fig. 1 A and B). The presence of a few B220+IgM+ B cells and the lack of IgA plasma cells in the LP of aly/aly gut were maintained, regardless of the number of cells injected (1, 10, or 20 × 106 cells) or the time point after transfer (6, 10, or 16 weeks) (data not shown). Coinjection of BM cells with spleen lymphocytes also failed to increase intestinal B cells and IgA plasma cells (Fig. 1 A). The results indicate that neither normal BM nor spleen cells alone cannot rescue IgA synthesis in aly/aly LP. Interestingly, serum levels of IgAs that were undetectable in aly/aly mice, reached normal values after BM transplantation, due to the reconstitution of spleen with IgA plasma cells (Fig. 1 C–E). This confirms the previous result (16) and suggests that serum and intestinal IgAs are produced by populations of IgA precursor cells at different locations.

Fig. 1.

BM transplantation rescues serum but not intestinal IgAs in aly/aly mice. (A) Representative FACS profiles of LP cells stained for B220, IgM, and IgA from aly/+ and aly/aly mice before, and 10 weeks after, reconstitution with 1 × 107 BM cells, and BM together with 2 × 107 spleen cells from GFP Tg mice. Numbers indicate the percentages of lymphocytes in the gates. (B) IgA levels in feces of aly/aly mice and aly/aly reconstituted with cells from BM, total PP, or IgA-depleted PP at indicated times after transfer. (C) Serum IgA levels of aly/aly mice before, and 10 weeks after, reconstitution with BM from GFP Tg mice. Fecal and serum IgA levels in control mice (aly/+) are shown in B and C, respectively. (D) B220 and IgA profiles of spleen cells. (E) Sections of spleen stained for IgM (red) and IgA (green) from aly/+ and aly/aly mice before, and 10 weeks after, reconstitution with BM from GFP Tg mice.

Table 1. Experimental procedures and summary of the results.

|

aly/aly reconstituted with

|

Gut LP

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental system | Type of B cells | Stromal cells | IgM+ B cells | IgA+ plasma cells | Data shown in |

| BM | Naive | - | - | - | Fig. 1 |

| BM plus spleen | Naive | - | - | - | Fig. 1 |

| PP | Primed | - | + | + | Fig. 1 |

| Parabiosis with GFP Tg | Primed | - | + | + | Fig. 2 |

| BM and parabiosis with RAG-2-/- | Primed | - | + | + | Fig. 3 |

| BM B6 and | Naive | - | + | + | Fig. 4 |

| LP GFPTg | Primed | + | |||

| BM GFP Tg and | Naive | - | + | + | Fig. 4 |

| LP RAG-2-/- | - | + | |||

PP B Cells Generate IgA in aly/aly Gut. We then tested whether the gut-resident B cells rescue gut IgA synthesis in aly/aly mice. When PP cells from GFP Tg mice were transferred to aly/aly mice, the fecal IgA levels quickly and gradually increased up to 6 weeks after transfer, thereafter the values decreased, probably because of a limited half-life of PP B cells (Fig. 1B). IgA-depleted PP cells could also generate fecal IgAs, albeit at lower levels than for nonsorted PP cells, and all B220-IgA+ plasma cells identified in the LP were GFP+PP-derived cells (data not shown). The results indicate that both B220+IgA+ and B220+IgM+ gut-derived B cells migrated to the aly/aly intestine and generated IgA plasma cells. The different reconstitution capacity of BM and PP cells demonstrate that naïve and gut-primed B cells have different requirements for their migration and/or retention to the LP environment with NIK deficiency.

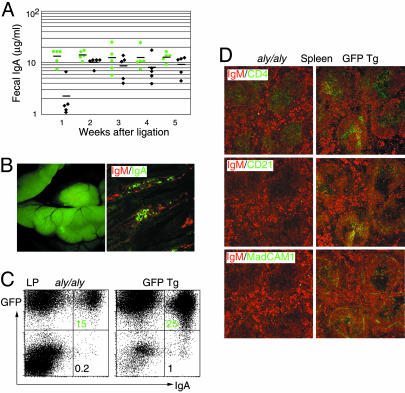

Parabiosis Rescue Gut IgA in aly/aly. To explore the mechanism by which naïve B cells can be primed to home to gut LP, we set up parabiotic experiments that can also overcome the lifespan limitation of PP cell transfers. In this system, GFP Tg mice are surgically joined with aly/aly mice, resulting in anastomoses of blood vessels and a complete cell exchange within a few days (17). As early as 1 week after parabiosis, aly/aly mice began to have IgA in their intestinal secretions, which reached a plateau after 2 weeks of continuous blood exchange (Fig. 2A). A large number of GFP+ cells homed to the small intestine of aly/aly mice (Fig. 2B Left), and immunofluorescence staining of the aly/aly small intestine revealed the presence of IgA+ plasma cells and IgM+ B cells in the LP (Fig. 2B Right). The percentages of LP IgA plasma cells in aly/aly mice at 10 weeks after ligation were estimated to be approximately one-half of those found in the GFP Tg partners (Fig. 2C). In these parabiotic aly/aly mice, the architecture of spleen remained disturbed, without marginal zone, small B cell follicles without follicular dendritic cell network, and no clear T cell/B cell segregation (18) (Fig. 2D), thus indicating that the mesenchimal compartment was not rescued by anastomosis (19).

Fig. 2.

Parabiosis with GFP Tg mice reconstitutes gut IgAs in aly/aly mice. (A) IgA levels in feces of parabiotic aly/aly mice (black) and GFP Tg partners (green) at indicated times after anastomosis. (B) Photograph and section of aly/aly small intestine 10 weeks after parabiosis with GFP Tg mice, stained for IgM (red) and IgA (green). (C) Representative FACS profiles of LP cells stained for IgA and plotted with GFP, from aly/aly and GFP Tg mice 10 weeks after anastomosis. Numbers indicate the percentage of lymphocytes in the respective quadrant. (D) Sections of spleens from aly/aly and GFP Tg mice 10 weeks after anastomosis, stained red for B cells (IgM), and stained green for T cells (CD4), follicular dendritic cells (CD21), and marginal zone (MadCAM-1).

Gut-Primed IgM+ B Cells Migrate to aly/aly LP. Using the parabiotic system, we wished to define the type of cells that migrated from GFP Tg mice to aly/aly small intestine. We therefore reconstituted irradiated aly/aly mice with BM cells from GFP Tg mice and then made parabiosis with RAG-2-/- mice 10 weeks after injection of BM cells. Strikingly, as early as 4 days after ligation, the percentages of B220+IgM+ B cells significantly increased in the LP of parabiotic aly/aly mice as compared with BM-reconstituted aly/aly mice without parabiosis (Fig. 3A Left Upper versus Figs. 1 A and 3B). At day 4, GFP+ cells migrated to RAG-2-/- mice and mainly located in the PP anlagen and mesenteric lymph node (Fig. 3C and data not shown), and the majority of the cells were B220+IgM+B cells (Fig. 3A Left Upper). A small number of B220+IgA+ cells and AID transcripts required for class switching were equally detected in LP preparation from the aly/aly and RAG-2-/- partners, 4 days after surgery (Fig. 3A Left Lower and D). B220-IgA+ plasma cells gradually increased in both partners, although at day 15 after parabiosis, RAG-2-/- mice had three to five times more IgA plasma cells as compared with aly/aly partners (Fig. 3A Right Lower). In consistence with FACS analyses, mRNA for an IgA postswitching marker (Iμ-Cα) significantly increased in the LP 15 days after parabiosis (Fig. 3D). The fact that transferred GFP+ BM cells can migrate to the LP of aly/aly mice soon after parabiosis with RAG-2-/- mice, but not without parabiosis, strongly suggests that the properties of transferred naïve B cells must have been modified during their passage through the RAG-2-/- gut microenvironment.

Fig. 3.

Gut-experienced IgM B cells home and switch in LP of aly/aly mice. (A) Representative FACS profiles of LP cells stained for B220 and IgM (Upper) or IgA (Lower) from aly/aly (reconstituted 10 weeks before with BM from GFP Tg mice) and RAG-2-/- mice, at 4 and 15 days after parabiosis. The profiles shown are for GFP+ cells. Numbers indicate the percentages of lymphocytes in the gates. RAG-2-/- LP preparations include PP cells. (B) Percentage of B220+IgM+ B cells in LP cells of aly/aly mice reconstituted 10 weeks before with BM, before and 4 days after, parabiosis with RAG-2-/- mice. Data represent mean ± SD, n = 3, unpaired Student's t test; P value is shown. Total numbers of cells recovered from LP were very similar in aly/aly mice before and after parabiosis. (C) Photograph of the small intestine of RAG-2-/- mouse 4 days after ligation with GFP+BM-reconstituted aly/aly mouse. Note the presence of GFP+ cells, mainly in the PP anlagen of RAG-2-/- mouse. (D) RT-qPCR of AID, CD19, and Iμ-Cα (IgA) in small intestine of parabiotic aly/aly and RAG-2-/- mice (without PP), at indicated days after ligation (n = 3, duplicate determinations, mean gene/GAPDH ratio ± SD are plotted). (E) Expression level of α4β7 integrin on B220+ GFP+ B cells isolated from spleen of aly/aly mice reconstituted 10 weeks before with BM from GFP Tg mice, and from spleen and LP of aly/aly and RAG-2-/- mice, 3 days after parabiosis. Data are from two parabiosis experiments. (F) RT-qPCR of MadCAM-1, CXCL12 (SDF-1), and CCL25 (thymus-expressed chemokine) in small intestine of wild-type and aly/aly mice (n = 3, duplicate determinations, mean gene/GAPDH ratio ± SD are plotted).

Among the molecular events that confer gut-seeking properties to B cells, the modulation of surface expression and activation status of integrin α4β7 might be responsible for the efficient migration to intestine of gut-experienced B cells. aly/aly mice had very few B cells in the intestine before parabiosis with RAG-2-/- mice (Fig. 3B), and B cells isolated from aly/aly spleen expressed intermediate levels of α4β7 [mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) = 67] (Fig. 3E). After parabiosis, the B cells that migrated to the intestine but not to the spleen of RAG-2-/-, up-regulated α4β7 (LP MFI = 80; spleen MFI = 66). Strikingly, only those with α4β7hi could home to the NIK-defective intestine (MFI = 100) (Fig. 3E).

Expression of the α4β7 ligand MadCAM-1, which is a key molecule for migration of B cells to the gut and is present on small LP venules, was found to be severely impaired in LTβR-/- mice (4). NIK is known to function downstream of LTβR (20, 21), and indeed, MadCAM-1 expression was undetectable by immunofluorescence staining in spleen of aly/aly mice (Fig. 2D). In gut of aly/aly mice, the expression of MadCAM-1 was, however, very similar at both mRNA and protein levels to that observed in normal mice (Fig. 3F and data not shown) (22). Furthermore, the expression of thymus-expressed chemokine/CCL25 and SDF-1/CXCL12, two chemokines constitutively expressed within the small intestine and considered critical for intestinal homing and positioning of IgA precursor cells in the LP (23, 24), was similar in aly/aly and wild-type mice (Fig. 3F). These results indicate that a normal expression of MadCAM-1 and thymus-expressed chemokine/SDF-1 in aly/aly gut can support migration of gut-primed B cells, but not naïve B cells, to the LP with NIK-defective stromal cells.

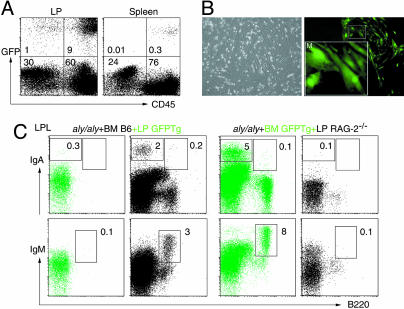

Naïve B Cells Homing to Gut. However, B cells and IgA plasma cells are present in the LP of mice that completely lack gut follicular structures, strongly suggesting that there is another migration pathway for recruitment of B cells to the gut. Apparently, this alternative pathway requires an intact gut stromal compartment that could not be reconstituted by BM transplantation in aly/aly mice (Table 1). To examine this possibility, lethally irradiated aly/aly mice were injected i.v. with BM cells from C57BL/6 mice, and simultaneously injected i.p. with LP cells from GFP Tg mice. In these chimeric mice, a small but significant number of CD45-GFP+ nonhematopoietic cells could be detected in cells isolated from LP, but not from spleen, of aly/aly mice, 10 weeks after the transfer (Fig. 4 A and B). Strikingly, this minimal replacement with NIK-sufficient stromal cells induced migration of BM B cells to aly/aly gut, as evidenced by the presence of normal percentages of B220+IgM+ B cells in aly/aly in LP (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, B220-IgA+ plasma cells were most likely derived from BM B cells, but not from LP cells, because they were almost exclusively GFP- cells (Fig. 4C Left Upper). BM-derived B220+IgM+ B cells and IgA plasma cells were identified in the gut when aly/aly mice were transplanted with BM cells from GFP Tg mice together with LP cells from RAG-2-/- mice, further supporting the above conclusion (Fig. 4C, Right Upper). The results clearly demonstrate that stromal cells in LP can provide the microenvironment to recruit naïve B cells to the gut, and to generate IgA plasma cells, independent of gut priming.

Fig. 4.

LP stromal cells are required for naïve B cells recruitment to small intestine LP. (A) Representative FACS profiles of LP cells and spleen cells from aly/aly mice injected 10 weeks before with 1 × 107 BM cells from C57BL/6 mice and 2 × 107 LP cells from GFP Tg mice, stained for common leukocyte antigen (CD45). Numbers indicate the percentages of lymphocytes in the respective quadrant. (B) Phase-contrast and fluorescence images of 7 days in vitro culture of LP cells. (Inset) Magnified image of GFP+ stromal cells. (C) Representative FACS profiles of LP cells stained for B220 and IgA or IgM from aly/aly mice injected 10 weeks before with 1 × 107 BM cells from C57BL/6 mice and 2 × 107 LP cells from GFP Tg mice (Left), and with 1 × 107 BM cells from GFP Tg mice and 2 × 107 LP cells from RAG-2-/- mice (Right). Green and black profiles represent lymphocytes gated GFP+ and GFP-, respectively. Numbers indicate the percentages of lymphocytes in the indicated gates.

Discussion

The prevailing view that the diffuse tissue of the gut LP represents mainly a reservoir for IgA plasma cells has been recently challenged. Dendritic cells located in the LP were shown to be able to directly uptake bacteria from the intestinal lumen, and to present antigens in situ in the LP (25). This phenomenon would explain the high plasticity of LP, which senses the gut environment and induces formation of ILFs by accumulation of a large number of B cells (26–28). Furthermore, LP environment was found to be sufficient to support both class switching and differentiation of IgM+ B cells to IgA plasma cells (6). All these events imply the existence of multiple pathways in the gut to recruit immune cells for very efficient protective local responses.

Using aly/aly mice, which cannot develop any follicular structures because of impaired LTβR signaling on stromal cells, we carried out a series of reconstitution experiments aimed to restore IgA compartment in gut, and demonstrated the existence of two independent pathways for recruitment of naïve and gut-primed IgM+ B cells to the gut LP.

We found that a functional NIK on LP stromal cells is critical for homing of naïve, but not gut-activated, B cells to the LP of the small intestine. Transfer of normal BM cells into aly/aly mice failed to rescue gut IgA, despite the complete recovery of IgA+ B cells and plasma cells in spleen. In contrast, B220+IgM+ B cells isolated from PP or naïve B cells that had been allowed to experience a NIK-sufficient gut environment could migrate to the LP and generate IgA plasma cells in aly/aly mice. Thus, it appears that the gut environment imprints naïve B cells with gut-seeking properties. Therefore, the role of organized structures in the gut is not only for induction of mucosal IgA B cell development but also for reprogramming the homing properties of B cells. A signature for gut-experienced B cells is modulation of expression and activation of mucosal integrin α4β7 (2). In support of this notion, only those B cells expressing high levels of integrin α4β7 after experiencing the gut environment could migrate to the aly/aly intestine. In parallel with the present observation, T cells were shown to be imprinted with gut-homing properties by gut dendritic cells, through induction of high levels of integrin α4β7 and CCR9, the receptor for thymus-expressed chemokine/CCL25 (29, 30).

Unlike gut-experienced B cells, naïve B cell recruitment to the LP requires gut-specific stromal cells with a functional NIK. This finding is based on the observation that coinjection of BM with LP stromal cells, but not of BM alone, can induce migration of BM B cells to the aly/aly gut. LP stromal cells appear to be more activated in the RAG-2-/- gut environment, because LP preparations from RAG-2-/- mice induced the recruitment of naïve B cells more efficiently than did LP preparations from normal mice (Fig. 4C). Thus, LP stromal cells can recruit naïve B cells to the gut through an independent pathway that involves activation of NF-κB by NIK. This pathway would explain the surprising observation that retinoic acid-related orphan receptor γt-/- mice and Id2-/- mice that completely lack follicular organization in the gut, have normal B cells and IgA plasma cells, respectively, in their LP (3) (Id2-/-, S.F., unpublished data). It would also explain the large diversity of B cell repertoire in ILFs that were induced by changes of gut microbiota in AID-/- mice that lack hypermutated IgA (26, 31). The characterization of stromal cell population(s) and the molecular mechanisms responsible for recruitment of naïve B cells and organization of follicular structures in the gut LP represent challenges for future studies.

Taken together, our work revealed that gut-experienced B cells and naïve B cells have different migration requirements to the gut LP, and that the NIK-dependent activation of NF-κB on LP stromal cells is critical for naïve B cell migration to the small intestine.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. O. Kanagawa, K. Kinoshita, M. Muramatsu, H. Nagaoka, T. Okazaki, R. Shinkura, and H. Yoshida for discussions and comments on the manuscript.

Author contributions: S.F. and K.S. designed research; K.S., B.M., and Y.D. performed research; T.H. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; S.F., K.S., and B.M. analyzed data; and S.F. and K.S. wrote the paper.

Abbreviations: AID, activation-induced cytidine deaminase; BM, bone marrow; ILF, isolated lymphoid follicle; LP, lamina propria; NIK, NF-κB-inducing kinase; PP, Peyer's patch; Tg, transgenic; qPCR, quantitative PCR.

References

- 1.Cebra, J. J. & Shroff, K. E. (1994) in Handbook of Mucosal Immunology, eds. Ogra, P., Mestecky, J., Lamm, M., Strobel, W., McGhee, J. & Bienenstock, J. (Academic, San Diego), pp. 151-157.

- 2.Butcher, E. C. (1999) in Mucosal Immunology, eds. Ogra, P., Mestecky, J., Lamm, M., Strobel, W., Bienenstock, J. & McGhee, J. (Academic, San Diego), pp. 507-522.

- 3.Eberl, G. & Littman, D. R. (2004) Science 305, 248-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang, H. S., Chin, R. K., Wang, Y., Yu, P., Wang, J., Newell, K. A. & Fu, Y. X. (2002) Nat. Immunol. 3, 576-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryffel, B., Le Hir, M., Muller, M. & Eugster, H. P. (1998) Dev. Immunol. 6, 253-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fagarasan, S., Kinoshita, K., Muramatsu, M., Ikuta, K. & Honjo, T. (2001) Nature 413, 639-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muramatsu, M., Kinoshita, K., Fagarasan, S., Yamada, S., Shinkai, Y. & Honjo, T. (2000) Cell 102, 553-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kinoshita, K., Harigai, M., Fagarasan, S., Muramatsu, M. & Honjo, T. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 12620-12623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyawaki, S., Nakamura, Y., Suzuka, H., Koba, M., Yasumizu, R., Ikehara, S. & Shibata, Y. (1994) Eur. J. Immunol. 24, 429-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamada, H., Hiroi, T., Nishiyama, Y., Takahashi, H., Masunaga, Y., Hachimura, S., Kaminogawa, S., Takahashi-Iwanaga, H., Iwanaga, T., Kiyono, H., et al. (2002) J. Immunol. 168, 57-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fagarasan, S., Shinkura, R., Kamata, T., Nogaki, F., Ikuta, K., Tashiro, K. & Honjo, T. (2000) J. Exp. Med. 191, 1477-1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shinkura, R., Kitada, K., Matsuda, F., Tashiro, K., Ikuta, K., Suzuki, M., Kogishi, K., Serikawa, T. & Honjo, T. (1999) Nat. Genet. 22, 74-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dejardin, E., Droin, N. M., Delhase, M., Haas, E., Cao, Y., Makris, C., Li, Z. W., Karin, M., Ware, C. F. & Green, D. R. (2002) Immunity 17, 525-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramakrishnan, P., Wang, W. & Wallach, D. (2004) Immunity 21, 477-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muller, G. & Lipp, M. (2003) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 15, 217-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macpherson, A. J., Lamarre, A., McCoy, K., Harriman, G. R., Odermatt, B., Dougan, G., Hengartner, H. & Zinkernagel, R. M. (2001) Nat. Immunol. 2, 625-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donskoy, E. & Goldschneider, I. (1992) J. Immunol. 148, 1604-1612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koike, R., Nishimura, T., Yasumizu, R., Tanaka, H., Hataba, Y., Watanabe, T., Miyawaki, S. & Miyasaka, M. (1996) Eur. J. Immunol. 26, 669-675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wagers, A. J., Sherwood, R. I., Christensen, J. L. & Weissman, I. L. (2002) Science 297, 2256-2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsushima, A., Kaisho, T., Rennert, P. D., Nakano, H., Kurosawa, K., Uchida, D., Takeda, K., Akira, S. & Matsumoto, M. (2001) J. Exp. Med. 193, 631-636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yin, L., Wu, L., Wesche, H., Arthur, C. D., White, J. M., Goeddel, D. V. & Schreiber, R. D. (2001) Science 291, 2162-2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koike, R., Watanabe, T., Satoh, H., Hee, C. S., Kitada, K., Kuramoto, T., Serikawa, T., Miyawaki, S. & Miyasaka, M. (1997) Cell. Immunol. 180, 62-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bowman, E. P., Kuklin, N. A., Youngman, K. R., Lazarus, N. H., Kunkel, E. J., Pan, J., Greenberg, H. B. & Butcher, E. C. (2002) J. Exp. Med. 195, 269-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cyster, J. G. (2003) Immunol. Rev. 194, 48-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rescigno, M., Urbano, M., Valzasina, B., Francolini, M., Rotta, G., Bonasio, R., Granucci, F., Kraehenbuhl, J. P. & Ricciardi-Castagnoli, P. (2001) Nat. Immunol. 2, 361-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fagarasan, S., Muramatsu, M., Suzuki, K., Nagaoka, H., Hiai, H. & Honjo, T. (2002) Science 298, 1424-1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lorenz, R. G., Chaplin, D. D., McDonald, K. G., McDonough, J. S. & Newberry, R. D. (2003) J. Immunol. 170, 5475-5482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fagarasan, S. & Honjo, T. (2003) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3, 63-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mora, J. R., Bono, M. R., Manjunath, N., Weninger, W., Cavanagh, L. L., Rosemblatt, M. & Von Andrian, U. H. (2003) Nature 424, 88-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johansson-Lindbom, B., Svensson, M., Wurbel, M. A., Malissen, B., Marquez, G. & Agace, W. (2003) J. Exp. Med. 198, 963-969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suzuki, K., Meek, B., Doi, Y., Muramatsu, M., Chiba, T., Honjo, T. & Fagarasan, S. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 1981-1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]