Abstract

Pseudomonas syringae strains deliver variable numbers of type III effector proteins into plant cells during infection. These proteins are required for virulence, because strains incapable of delivering them are nonpathogenic. We implemented a whole-genome, high-throughput screen for identifying P. syringae type III effector genes. The screen relied on FACS and an arabinose-inducible hrpL σ factor to automate the identification and cloning of HrpL-regulated genes. We determined whether candidate genes encode type III effector proteins by creating and testing full-length protein fusions to a reporter called Δ79AvrRpt2 that, when fused to known type III effector proteins, is translocated and elicits a hypersensitive response in leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana expressing the RPS2 plant disease resistance protein. Δ79AvrRpt2 is thus a marker for type III secretion system-dependent translocation, the most critical criterion for defining type III effector proteins. We describe our screen and the collection of type III effector proteins from two pathovars of P. syringae. This stringent functional criteria defined 29 type III proteins from P. syringae pv. tomato, and 19 from P. syringae pv. phaseolicola race 6. Our data provide full functional annotation of the hrpL-dependent type III effector suites from two sequenced P. syringae pathovars and show that type III effector protein suites are highly variable in this pathogen, presumably reflecting the evolutionary selection imposed by the various host plants.

Keywords: host–microbe interaction, plant pathogenesis, Arabidopsis, FACS

The commonly studied plant bacterial pathogen, Pseudomonas syringae, is subdivided into pathovars based on their ability to cause disease on one or more distinct host species. During infection, P. syringae and other Gram-negative pathogens deliver type III effector proteins via a type III secretion system (TTSS) (hrp/hrc genes in P. syringae; ref. 1) from the bacterium into host cells (2). P. syringae strains incapable of delivering type III effectors are nonpathogenic (3). Thus, the type III effectors each strain delivers are required for pathogenicity. In contrast, if just one of the type III effectors is “recognized” by the plant immune system's surveillance machinery [disease resistance (R) proteins], a battery of host responses is triggered, including localized programmed cell death, termed the hypersensitive response (HR) (4). In this case, the pathogen is rendered avirulent; its multiplication is limited, and it does not cause disease. As a consequence, some type III effector genes have been functionally defined as avirulence (avr) genes. Recognition of type III effector proteins by corresponding R proteins may therefore limit the particular host range of individual P. syringae pathovars.

P. syringae type III effector genes share several characteristics. Their expression is coordinately regulated with the TTSS-encoding genes by the alternative σ factor, HrpL (5). Genes encoding both the TTSS and type III effector proteins also share a cis-element (hrp-box) in their promoters (6). Finally, delivery of type III effector proteins into the host cell depends on the TTSS and a loosely defined N-terminal signal in the type III effector protein that includes >10% serine or proline in the first 50 aa, an aliphatic amino acid or proline at position 3 or 4, and the absence of negatively charged amino acids in the first 12 residues (7–9).

Nonsaturating genetic screens have relied on these characteristics. Guttman et al. (9) identified 15 protein fusions defining genes whose N termini were sufficient for TTSS-dependent translocation. These included 12 previously uncharacterized type III effector proteins. Boch et al. (10) identified genes that were induced by in planta conditions and regulated by HrpL in vitro. Six of these encoded previously identified type III effector proteins. Bioinformatic approaches relying on the predicted shared characteristics of type III effector genes have also been used to identify candidate type III effector genes. The genomes of three P. syringae pathovars, tomato race DC3000 (Pto) (www.pseudomonas-syringae.org), phaseolicola race 6–1448a (Pph6) (www.pseudomonas-syringae.org), and syringae race B728a (Psy) (www.jgi.doe.gov/index.html) have been sequenced (11). Genes encoding putative type III effector proteins and helpers, referred to as hop (hrp-dependent outer protein) genes were identified in these genomes by the presence of putative hrp-boxes (12, 13), and ORFs with N-terminal amino acid compositions consistent with known Hops (8, 9, 14, 15). Helper proteins are secreted from the bacterium via the TTSS but likely do not function within the host cell. Their presumptive roles are to assist the TTSS in delivery of type III effector proteins (15). From these efforts, Pto was estimated to deliver ≈40 different Hops (7–10, 12–15). Far fewer Hops were predicted in Psy B728a (14). Thirty Hops were predicted from Pph6 based on homology to known and predicted Hops from other strains (16). The exact number of type III effector proteins based on these predictions has not been experimentally validated.

We modified a technique termed differential fluorescence induction (DFI) (17) for high-throughput discovery of HrpL-regulated genes from pathovars of P. syringae. Genomic libraries of P. syringae were screened for clones expressing GFP in a HrpL-dependent manner by using FACS. Identified clones were sequenced and assembled. Resulting contiguous DNA sequences (contigs) were examined for the characteristics of type III effector genes mentioned above. We amplified and cloned full-length candidate genes in-frame to the coding region of the C-terminal 177 aa of the type III effector protein AvrRpt2, from which the N-terminal 79 aa are deleted (Δ79AvrRpt2; refs. 9, 18, and 19). Cells expressing these fusion proteins were infiltrated into plants expressing RPS2, the R protein that “recognizes” AvrRpt2, to determine which of the candidate genes encode proteins that can translocate Δ79AvrRpt2, and are hence type III effector proteins. We present our method and analyses of the type III effector suites from Pto and Pph6. Our data provide full functional annotation for the HrpL-regulated type III effector proteins from these two strains, and provide a tool with which to characterize the type III effector suites from the entire range of P. syringae pathovars. The two strains carry different sets of type III effectors. Essentially all of the type III effector genes are located in nonorthologous positions in the respective genomes. These findings suggest that type III effector suites are evolutionarily very fluid, and that host range can be limited by “recognition” of type III effector protein by host R proteins, as well as by the lack of positive virulence functions in the pathogen.

Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions. P. syringae strains Pto, PtoΔhrpL and Pph6 (all rifampicin resistant) were grown in King's B (KB) media at 28°C with shaking or on KB media agar plates at 28°C. Before FACS sorting, PtoΔhrpL was grown in minimal media, modified from ref. 20 to include 1% glycerol, 0.5% dextrose, 10 mM l-glutamate with or without 200 mM or 75 mM l-(+)-arabinose (Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), at 28°C with shaking. Escherichia coli DH5α was used in all cloning procedures and grown on LB agar plates or in SOB media at 37°C with shaking. The following antibiotics were used for both P. syringae and E. coli:50 μg/ml rifampicin, 30 μg/ml kanamycin, 5 μg/ml tetracycline (10 μg/ml for agar plates), and 25 μg/ml cyclohexamide. PtoΔhrpL was provided by B. Staskawicz (University of California, Berkeley).

Construction of Plasmids. pCFS40 (21) was modified to carry an idealized Shine–Delgarno sequence from gene10 of phage T7, upstream of hrpLPto (Supporting Text). Another vector, pBBR1-MCS2 (22), was modified to carry in three different reading frames, an operon fusion of Δ79avrRpt2 followed by GFP3 (23). The operons are flanked by RNA terminators (Supporting Text). These are referred to as DFI vectors. The vector in frame 1 was converted into a Gateway-ready vector by digesting with SmaI and ligating in conversion cassette C.1 (Invitrogen).

Library Construction. DNA was extracted from P. syringae (24), purified by using CTAB (25), and either partially digested with Tsp509I, AluI, BstUI, HaeIII, or RsaI or physically sheared by using a double stroke shearing device (Fiore Automation, Salt Lake City, UT). Fragments from 0.5–0.8 kb, 0.8–1.4 kb, and 1.4–2.0 kb were extracted and cloned into either EcoRI- or SmaI-digested and shrimp alkaline phosphatase (SAP)-treated DFI vectors. E. coli colonies carrying clones of similarly sized ligation products were pooled and mated en masse by modified triparental mating (P. Ronald, personal communication), with PtoΔhrpL + pBAD::hrpL and pRK2013.

Construction of Full-Length Gene Fusions. Candidate HrpL-induced gene fragments were amplified from cells harboring the DFI plasmids (Supporting Text). Contigs were assembled and layered onto the genome sequences of Pto or Pph6 (ref. 11 and www.p-seudomonas-syringae.org). Full-length genes and operons were cloned by two-step PCR (Supporting Text). PCR products were recombined by BP reaction into pDONOR207 following the manufacturer's recommendations (Invitrogen). All products were sequenced and then recombined into DFI vector 1 by using LR (Invitrogen). Candidate genes were individually mated into Pto + pBAD::hrpL by triparental mating (P. Ronald, personal communication) with pRK2013.

FACS. FACS was performed on a MoFlo (Cytomation). Analysis by FACS was performed on a FACscan from Becton Dickinson. One microliter of overnight culture cells was diluted into 400 μl of 1× PBS. Events shown in histograms (GFP, FL1) were gated on both side scatter (SSC) and forward scatter. Both were detected in log, and events were triggered on SSC. A total of 10,000 events were collected for each analysis (see Supporting Text).

Plant Infiltrations. Infiltrations of leaves of Arabidopsis rpm1–3 were done as described (26). The HR was scored blind no more than 26 h after inoculation. Results were compared to leaves infiltrated with Pto carrying a HrpL-regulated full-length avrRpt2 or an empty vector.

Results

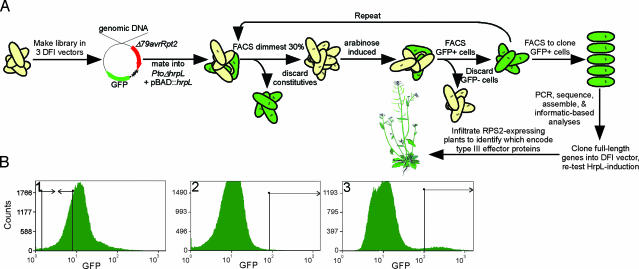

Vectors and Library Construction for DFI. We created three DFI vectors for “trapping” HrpL-regulated promoters (Fig. 1A and Supporting Text). These have cloning sites, in all three reading frames upstream of a promoterless avirulence gene lacking the N-terminal coding 79 aa (Δ79avrRpt2; refs. 9, 18, and 19). Following Δ79avrRpt2 in these DFI vectors is a promoterless GFP3 gene (23). We also created pBAD::hrpL, a separate vector with an arabinose-inducible hrpLPto (hrpL; Supporting Text). DNA fragments from Pto or Pph6 were cloned into each of the three DFI vectors and mobilized into PtoΔhrpL conditionally complemented with pBAD::hrpL. The library representation was at least 10-fold excess for each genome in each reading frame.

Fig. 1.

A high-throughput, FACS-based screen for P. syringae type III effector genes. (A) Diagram depicting the flow of our screen. Libraries were constructed in DFI vectors 1–3 upstream of Δ79avrRpt2::GFP3 and mobilized into Pto carrying pBAD::hrpL. Clones carrying HrpL-regulated inserts were isolated in a four-step process using FACS. Cells were first grown in modified minimal medium lacking arabinose, and the least fluorescent ≈30% of cells were collected to eliminate those constitutively expressing GFP. These ≈200,000 cells were subsequently grown in minimal medium with arabinose, and a small population of cells with the highest level of GFP expression, compared to those of a negative control population grown in the absence of arabinose, were collected by FACS (see B). These two steps were repeated, except that the GFP-positive cells were individually cloned by FACS after the second arabinose induction. DNA inserts were amplified, sequenced, and assembled. Contigs were analyzed, and full-length genes and operons were identified, cloned upstream of Δ79avrRpt2::GFP3, and tested for HrpL-induction as well as translocation of Δ79AvrRpt2 into leaves of RPS2-expressing plants. (B) Three FACS histograms from the screen for HrpL-induced genes from Pto. Histogram 1 shows distribution of GFP-fluorescence of the original library before any enrichment. The boxed area represents the region that was FACS cloned (least fluorescent 28.82% with a mean of 5.73. Histogram 2 shows distribution of GFP-fluorescence after growth in arabinose. A fluorescent population of the brightest 0.44% (mean of 227.66) of cells was sorted (compared to 0.34% and 147.24, respectively, in the same fluorescence range in uninduced controls of the same cell population). Histogram 3 shows distribution of GFP-fluorescence after all four FACS enrichment steps. The boxed area represents the region from which individual cells were FACS cloned; 4.66% with a mean of 325.50 versus 0.42% and 231.13, respectively, for the uninduced negative control. Each histogram represents at least 40,000 cells. x axis shows GFP fluorescence in log. y axis shows number of cells in each channel.

The DFI Screen for Pto HrpL-Regulated Genes. Pto was screened for HrpL-regulated genes by using FACS as described in Fig. 1 and the Supporting Text. We identified 43 HrpL-regulated genes/operons (Supporting Text, Table 2, and Fig. 3, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Five conserved HrpL-regulated TTSS promoters, hrpA, hrpF, hrpJ, hrpP, and hrpK (27), were present in contigs represented by many different clones in Pto as well as Pph6, supporting the contention that the screens were near saturating (Table 2). Fifty-nine hop genes were previously proposed in Pto and their protein products were classified (www.pseudomonas-syringae.org) as type III effector proteins or helper proteins, based on biological tests (15), or as candidate Hops (14, 15). We found only 29 of the 39 proposed effectors and helpers. Eight of the 10 genes we missed either lacked hrp-boxes, are potentially in operons, and/or are located on an endogenous plasmid (Table 2 and www.pseudomonas-syringae.org) that our lab isolate of Pto lacks (data not shown). Therefore, only two of the previously identified hop genes were actually missed in our screen: hopAA1–2 and schV-hopV1. We also found eight of the 20 genes previously listed as candidate hop genes (www.pseudomonas-syringae.org) and seven that were previously suggested to be HrpL-regulated or previously unidentified (Table 2 and ref. 10).

We created 61 full-length gene fusions to Δ79avrRpt2::GFP3, accounting for 50 of the 59 predicted hop genes (from the plasmid-bearing strain of Pto; ref. 11 and www.pseudomonas-syringae.org). We included 10 categorized hop genes (two that escaped our screen, four that lack hrp-boxes, and four that are located on the endogenous plasmid), and 13 additional candidate hop genes (eight of which were identified in our screen, five of which were not). Forty-seven of these 61 gene fusions exhibited HrpL-dependent induction (Table 1 and Table 3, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). We observed a strong correlation between HrpL-induction and the presence of a hrp-box. Nine of 11 predicted genes without predictable hrp-boxes were not induced by HrpL, but seven of these were induced when cloned as operon fusions to their respective upstream genes that do contain hrp boxes (Table 3, not bold). Only two possible operons with clear hrp boxes were not induced by HrpL in our assays (Table 3).

Table 1. Full-length proteins of P. syringae capable of delivering Δ79AvrRpt2 into plant cells.

| Translocation signal*

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Score† | Ind‡ | % S | Aliph. AA | Lack-AA |

| Pto | |||||

| Group 1 | |||||

| HopK1 | 4.00 | 18 | 4(I) | Y | |

| HopY1 | 7.3 | 19.33 | 16 | 3(I) | Y |

| HopH1 | 17.2 | 45.33 | 10 | 4(P) | Y |

| HopC1 | 9.4 | 43.67 | 16 | 3(I) 4(V) | Y |

| HopD1 | 10.0 | 7.50 | 14 | 3(P) 4(L) | Y |

| HopQ1 | 13.6 | 14.67 | 24 | 4(P) | Y |

| HopAM1-1 | 5.6 | 23.33 | 16 | N | Y |

| HopAA1-1 | 11.4 | 7.25 | 18 | 3(I) | Y |

| HopAF1 | 5.9 | 5.50 | 26 | 3(L) | Y |

| HopP1 | 10.4 | 19.25 | 20 | N | Y |

| HopAB2 | 15.2 | 19.43 | 18 | 4(I) | Y |

| AvrPto1 | 19.3 | 36.00 | 16 | 4(I) | Y |

| HopE1 | 16.0 | 46.00 | 14 | 4(V) | Y |

| HopAA1-2 | 6.8 | 1.79 | 20 | 3(I) | Y |

| HopAR1 | 7.7 | 6.50 | 20 | 3(P) 4(L) | Y |

| HopI1 | 7.9 | 17.83 | 14 | 4(L) | Y |

| HopAM1-2 | 5.6 | 25.50 | 16 | N | Y |

| Group 2 | |||||

| HopO1-1 | 5.1 | 14.50 | 24 | 4(I) | Y |

| HopV1 | 5.4 | 10.00 | 6 | N | N |

| HopO1-2§ | 11.4 | 1.00 | 28 | 3(I) | Y |

| HopF2 | 12.3 | 1.83 | 20 | 3(I) | Y |

| HopN1 | 6.0 | 8.67 | 14 | 3(I) | Y |

| HopM1 | 3.0 | 23.00 | 10 | N | Y |

| HopB1§ | 8.0 | 25.50 | 12 | 3(P) 4(V) | Y |

| HopA1 | 6.7 | 18.00 | 10 | 3(P) 4(I) | Y |

| Group 3 | |||||

| HopR1¶ | 12.8 | 3.13 | 18 | 4(V) | Y |

| AvrE1¶ | 11.2 | NT | 16 | 4(P) | Y |

| HopX1∥ | 4.2 | 1.67 | 14 | 3(I) | Y |

| HopG1∥ | 10.4 | 19.33 | 10 | 3(I) | Y |

| HopB1§ | 1.00 | 12 | 3(P) 4(V) | Y | |

| HopO1-2§ | 1.00 | 28 | 3(I) | Y | |

| Pph6 | |||||

| Group 1 | |||||

| AvrB3 | 8.7 | 20.83 | 20 | 4(I) | Y |

| HopAB2 | 0.5 | 3.00 | 16 | 4(I) | Y |

| HopAU1 | 9.1 | 11.60 | 10 | 3(P) 4(V) | Y |

| HopG1 | 8.1 | 9.67 | 14 | 3(I) | Y |

| HopK1 | 16.78 | 24 | 4(I) | Y | |

| HopAW1 | 7.7 | 22.40 | 10 | 3(V) | Y |

| AvrB2-3 | 9.1 | 18.33 | 26 | 4(V) | Y |

| HopQ1 | 13.6 | 11.00 | 22 | 4(P) | Y |

| HopW1-1 | 6.4 | 16.00 | 18 | 3(P) | Y |

| HopAV1 | 7.8 | 2.25 | 14 | N | Y |

| HopAF1 | 7.0 | 17.67 | 24 | 3(L) | Y |

| HopD1 | 10.0 | 21.25 | 14 | 3(P) 4(L) | N |

| HopI1 | 7.4 | 23.00 | 16 | 4(L) | Y |

| HopAT1 | 1.2 | 13.20 | 8 | 4(I) | Y |

| HopR1 | 9.9 | 4.73 | 16 | 4(V) | Y |

| Group 2 | |||||

| HopX1 | 9.2 | 23.22 | 20 | 3(I) | Y |

| HopF2 | 9.6 | 17.50 | 22 | 3(I) | Y |

| Group 3 | |||||

| HopM1∥ | 3.6 | 4.67 | 4 | 4(P) | Y |

| AvrE1∥ | 10.0 | 1.67 | 10 | 3(L) | Y |

Proteins in bold are encoded by genes identified in our screen. Genes from each strain are divided into three groups: group 1, expressed as single genes; group 2, expressed in an operon downstream from putative chaperone-encoding genes, except HopB1 and HopX1(Pph6), which were expressed downstream from hrpK; group 3, inconsistent translocation results.

Criteria as defined in refs. 8, 9, 14, and 15. Criteria that did not correlate to those of a type III effector protein are underlined

Bit score for the hrp-box; scores >2.0 are considered reliable; <2.0 are underlined. Scores <0 are not listed

Fold Induction = mean FACS-derived GFP fluorescence of the positive peak divided by the mean fluorescence of uninduced cells. Negative control, empty vector; 1-fold induction. Positive control, AvrRpm1 upstream of GFP; 122-fold induction. NT, not tested

Elicited strong HR in 2/3 experiments as both gene and operon fusions, and therefore included in groups 2 and 3

Could not construct full-length fusions to Δ79AvrRpt2

Caused tissue collapse in only one of three experiments

The DFI Screen for Pph6 HrpL-Regulated Genes. We also screened Pph6 and identified 41 HrpL-induced genes or operons (Table 2), including 23 of the 30 predicted hop genes in Pph6 (16). Forty-five genes/operons were fused to Δ79avrRpt2::GFP3 (Table 2). We elected not to retest seven other predicted candidate hop genes (16); two corresponded to hrpZ and hrpK of the hrp/hrc cluster, the other five were not identified in our screen and have no functional characteristic of a type III effector gene ascribed to them. We confirmed that 36 of 45 fusions were HrpL-induced (Tables 1 and 3). These defined 35 genes, including 21 of the 23 predicted hop genes of Pph6 identified in our screen.

Characterization of HrpL-Induced Proteins for Delivery into Plants. TTSS-dependent translocation of full-length proteins into plant cells is the most direct and most stringent test for defining type III effector proteins (14). All full-length fusions to Δ79AvrRpt2 derived from Pto and Pph6 described above (in wild-type Pto), were infiltrated into leaves of RPS2-expressing plants, relying on induction of the endogenous HrpL by in planta conditions. This experiment determines which candidate genes encode type III effector proteins, but it will not identify helper proteins. We also analyzed the translated sequences of all of the genes for putative TTSS-dependent sequences (Tables 1 and 3 and refs. 8, 9, 14, and 15). These characteristics include >10% serine or proline in the first 50 aa, an aliphatic amino acid or proline at position 3 or 4, and the absence of negatively charged amino acids in the first 12 residues. We found a high correlation between experimentally translocated proteins and those having amino acids consistent with at least two of the proposed secretion signal rules (Table 1). Proteins that were unable to deliver Δ79AvrRpt2 generally had discordance with these rules or were not HrpL-regulated (Table 3).

Twenty-five proteins from Pto reliably elicited RPS2-dependent HR in multiple experiments (Table 1). Twenty of these were identified in our screen; five were missed for reasons defined above. Thirty-two of the 61 fusion proteins consistently failed to elicit the HR (Table 3). AvrPphEPto (HopX1) and HopG1 elicited weak, inconsistent HR. Nevertheless, we classified them as type III effector proteins. We were unable to clone full-length genes of hopR1 or avrE1Pto, but we cautiously list them as type III effectors based on orthology to known type III effector proteins. The sum of our HrpL-dependent expression data and Δ79avrRpt2 translocation data (Tables 1 and 3) suggests that the previous informatics-based predictions significantly overestimated the number of type III effector genes in Pto (www.pseudomonas-syringae.org and refs. 7, 14, and 15). We conclude that Pto has at least 24, and possibly 28, HrpL-regulated, translocated type III effector proteins, plus hopO1-2, which is apparently translocated but HrpL-independent.

Seventeen fusion proteins from Pph6 reproducibly elicited an HR (Table 1). Twelve of these proteins had been predicted based on homology to other Hops (16). We additionally found a member of the AvrB family (28) not previously identified in Pph6 (16); we named this protein AvrB3Pph6. HopM1Pph6 and AvrEPph6 fusions to Δ79avrRpt2 did not elicit reliable HR phenotypes, but were cautiously classified as type III effectors based on orthology to known proteins that traverse the TTSS (Table 1 and ref. 29). Twenty-seven Pph6 fusion proteins consistently failed to elicit an RPS2-dependent HR (Table 3). Twenty corresponded to genes/operons identified in our screen, and are therefore HrpL-regulated, but not delivered to host cells. One of them, HopV1Pph6, did not give a reliable HR, and its translated sequence is not similar enough to the translocated HopV1Pto to use orthology in classifying HopV1Pph6 as a type III effector protein. The N-terminal regions do not align and HopV1Pph6 is ≈244 residues longer than HopV1Pto. The remaining seven proteins correspond to predicted Pph6 homologs of Pto candidate type III effector genes (Table 3). We conclude that Pph6 encodes at least 17, and possibly 19, HrpL-regulated and translocated type III effector proteins.

Identification of Four Previously Undescribed Type III Effectors in Pph6. We identified four previously undescribed type III effector proteins in Pph6 (Table 1 and Table 4, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). HopAT1 is predicted to be only 88 aa long. HopAU1 and HopAV1 have homology to predicted proteins from two pathovars of Xanthomonas and Ralstonia, respectively. A HopAV1 ortholog was identified in a screen for HrpB-induced genes of Ralstonia (30). HopAW1 has homology to the translated product of the so-called ORF3 from the pAV511 plasmid of Pph race 7 (31), except that ORF3 from Pph race 7 has a 10-bp deletion relative to that of Pph6, potentially truncating the protein to 90 residues.

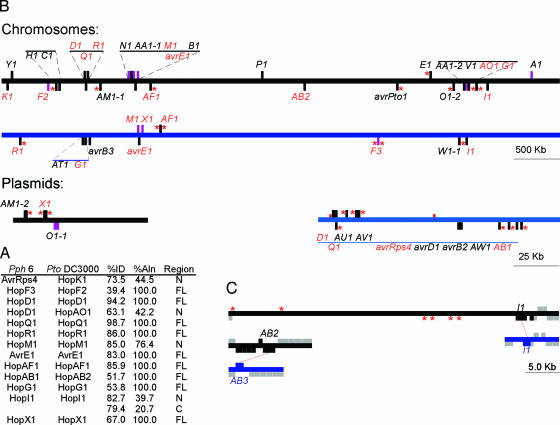

Pto and Pph6 Share 13 Type III Effector Proteins. These common proteins are, largely, highly related, and homology in most cases spans the length of the deduced protein (Fig. 2A). However, when we compared the genomic context of all of the type III effector genes (Fig. 2B and Supporting Text) only the avrE1 and hopM1 genes from each strain are immediately flanked by orthologous ORFs. Both of these genes are adjacent to the hrp/hrc cluster, within the conserved effector locus of each strain (27). Two other orthologs share one common flanking ORF, but have rearrangements relative to one another on their other side. In this case, the five predicted ORFs 5′ to hopI1Pto and hopI1Pph6 are orthologous and colinear (Fig. 2C). In contrast, although only 2.5 kb of DNA separates hopI1Pph6 from its 3′ neighboring ORF, 40.2 kb and six mobile element-like genes separate hopI1Pto from the same 3′ orthologous ORF. Interestingly, the chromosomal virPphAPto (hopAB2Pto) is flanked by ORFs that are orthologous to those flanking the nontranslocated virPphAPph6 (hopAB3Pph6) gene located on the Pph6 chromosome (Fig. 2C), but not to those that flank the translocated virPphAPph6 (hopAB2Pph6) that resides on the Pph6 plasmid.

Fig. 2.

Genome context of type III effector genes in Pto and Pph6.(A) Orthologous type III effector proteins were compared by using blastx analysis of deduced Pph6 proteins against the translated sequences from Pto. Significant homologies are given as % identity (%ID), % of the proteins that aligned (% Aln) and regions of alignment; n, amino terminal, FL, full-length entire protein; C, carboxy terminal. (B) Type III effector genes are depicted along horizontal bars representing the bacterial chromosome or plasmid (black, Pto; blue, Pph6). Marks above and below the bar are the genes encoded on the top and bottom strand, respectively. Black and purple marks represent genes encoding type III effector genes and operons, respectively. Letter abbreviations correspond to the unified naming nomenclature of type III effector genes. Orthologous type III effector genes are highlighted in red. Predicted mobile elements are denoted with a red asterisks. (C) The orthologous copies of HopI1 as well as hopAB2Pto and hopAB3 occupy similar regions in their respective genomes. Flanking ORFs had >80% identity along the length of the sequence. Orthologous genes are connected by dotted red lines. Gray boxes, orthologous flanking ORFs; black bars or boxes, Pto; blue bars or boxes, Pph6; red asterisks, mobile elements.

AvrPphEPph6 (hopX1) is part of the hrpK operon. By contrast, avrPphEPto (hopX1) is located on an endogenous plasmid (15). Likewise, avrPphD (hopD1), hopQ1, and avrRps4 (hopK1) are located on the plasmid of Pph6, but orthologs are found on the Pto chromosome (Fig. 2B). AvrPphD (hopD1) and hopQ1 are separated by 116 bp in both Pto and Pph6. The 116-bp spacer regions differ by only 3 bp between the two strains. However, there is no other apparent conservation of flanking orthology between these genes as they have shuttled between chromosome and plasmid. The remaining common type III effector genes were found scattered throughout the chromosomes of their respective strains and do not share common flanking ORFs with their orthologs.

Discussion

P. syringae pathovars rely on their suites of type III effector proteins to colonize evolutionarily diverse plant hosts spanning ≈200 million years of evolution (32). These proteins manipulate the eukaryotic host cell to suppress host defense responses, facilitate nutrient acquisition, and contribute to colony size and spread (33, 34). A detailed understanding of the sets of type III effector genes in strains across this bacterial species will help unravel how host range is determined. For example, Pto is an aggressive Arabidopsis pathogen, but no strain of Pph is able to cause disease or trigger hypersensitive cell death on this host. Pto and Pph share 13 type III effector proteins. We reason that this set in Pph6 is insufficient for pathogenicity on Arabidopsis. This finding implies that one or more of the 16 extra-Pto type III effectors, perhaps in combination with the shared set, would render Pph6 pathogenic on Arabidopsis. Conversely, Pph6 is a pathogen of bean, and its set of 19 type III effector proteins is sufficient for pathogenicity, apparently in combination with the right set of host target alleles. However, Pto triggers an HR on bean. This finding suggests either that one or more of the 16 extra-Pto type III effectors is recognized by bean plants or allelic differences in one or that more of the 13 shared type III effector proteins in Pto allow for its recognition by bean. Only through definition of the entire type III effector gene suite can these hypotheses be evaluated carefully.

Horizontal transmission is likely a mechanism by which P. syringae pathovars acquire type III effector genes. All but three of the 13 sets of orthologs common to Pto and Pph6 are found scattered throughout the genomes and plasmids, with almost no flanking colinearity. Consequently, few extant type III effector genes were likely present before the divergence of these two strains. In contrast, two helper genes not linked to the hrp/hrc cluster, hopAJ1 and hopAK1, are flanked by orthologous ORFs, suggesting that they may have been present before the divergence of the two pathovars (data not shown). These data support a mix-and-match strategy used by P. syringae to acquire type III effector genes. The observation that several type III effector genes are associated with remnants of mobile elements (Fig. 2B, red asterisks) supports the notion that horizontal transmission is a key mechanism for acquisition of type III effector genes (35, 36).

Alternatively, or in addition, intra- and intergenic changes can also contribute to the evolution of type III effector suites of P. syringae strains. The plasmid of Pph6 (Fig. 2B) carries five type III effector genes and ORF4 in common with, and colinear to, orthologs on pAV511 of Pph race 7 (Pph7) (31). However, the avrPphF (hopF3Pph6 and hopF1Pph7) operons are found in different locations between the two strains: on the chromosome of Pph6 (Fig. 2B) and between avrD1 and avrPphC (avrB2) on the plasmid in Pph 7 (31). The respective ORF1 and ORF2 proteins encoded from the avrPphF operon in Pph6 are quite different from their counterparts in Pph 7 (27% and 39% identity, respectively), hence the subclassification of avrPphFPph6 as hopF3 (16). Interestingly, another copy of ORF4 is located on the chromosome, just 3′ to hopF3Pph6. This finding suggests that a pathogenicity island located on a plasmid was common to an ancestral pathovar of Pph6 and -7, and that subsequent rearrangements have occurred since their divergence. Pph6 also carries two identical HrpL-regulated genes of 433 bp (hopW1–2Pph6 and -3Pph6) that are homologous to hopW1–1 (blastn = 1.0 × 10-83, Table 3 and ref. 16). The two fragments are oriented in the same direction and flank a total of five type III effector genes and a HrpL-regulated shikimate kinase-encoding gene (Fig. 2B, red asterisks). This structure may indicate a recombination mechanism by which the plasmid could integrate/excise from the genome, like the PAI plasmid pFKN from P. syringae pv. maculicola M6 (37).

The recognition of any single type III effector protein by a plant R protein will render that individual bacterium avirulent on an otherwise normally susceptible host plant. One method to avoid “recognition” is inactivating the relevant type III effector genes. The genomes of these two P. syringae are graveyards of inactive type III effector genes. Both pathovars carry HrpL-expressed pseudogenes interrupted by transposable elements. When fused to Δ79AvrRpt2, none of these fusion proteins elicited an RPS2-dependent HR (Table 3). Pph6 carries a nearly identical copy of AvrB3 elsewhere in the genome, but it too has a transposon insertion. We did not identify this gene in our screen and consequently did not test it for HrpL-regulation or its protein for translocation. HopAB3 encodes a functional gene, but not a functional type III effector protein, likely because of the loss of the secretion signal (Table 3 and Fig. 4, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Finally, Pph6 carries an inactivated ortholog of hopAA1. Although it has an identifiable hrp-box, it is not expressed in a HrpL-dependent manner, has a premature stop codon, and is not delivered into plants. Strains may also carry type III effectors that mask the perception of other type III effector proteins (38–40).

We confirmed fewer type III effectors from Pto than previously predicted both experimentally and by informatic-based analyses (www.pseudomonas-syringae.org and refs. 7 and 15). This variance is likely due to different assays and criteria for defining type III effectors. Our definition is stringent, based on HrpL-dependent expression from native promoters and the ability to translocate full-length fusion to Δ79AvrRpt2 directly into plant cells. Previous analyses used, for example, secretion of candidate type III effectors into media after expression from the strong, constitutive npt II promoter (8). These approaches may resurrect transcriptionally silent or HrpL-independent ORFs as Hops (14) or lead to misclassification of helper proteins as type III effector proteins.

In some cases, protein fusions expressed from the promoter of an endogenous type III effector gene may be insufficient to produce enough protein for delivery of an RPS2-dependent HR. This may be the case for avrPphEPto and avrEPph6, which had some of the lowest fold-induction ratios and maximum mean GFP fluorescence values (1.67/25 and 1.67/50, respectively) of the HrpL-induced genes in our experiments (ranges of fold-induction and maximum GFP-fluorescence were 1.14–46.67 and 25–2,160, respectively). However, very little protein needs to be expressed and delivered to elicit the RPS2-dependent HR (14). These weakly HrpL-induced genes will nevertheless be identified in our screen because of their HrpL-dependent gene expression. These genes may require more sensitive assays than fusions to Δ79AvrRpt2, which rely on their endogenous promoters, for proper classification as type III effector proteins.

Nearly all Δ79AvrRpt2 protein fusions gave reproducible positive or negative RPS2-dependent HR results. However, a few results were inconclusive. Some fusions to Δ79AvrRpt2 might be unstable, unable to pass through the TTSS, or misfolded to preclude triggering of RPS2-dependent HR. Arguing against this is our finding that HopR1Pph6 (>200 kDa before the addition of Δ79AvrRpt2) did elicit RPS2-dependent HR. Therefore, we believe that few, if any, of the higher expressed proteins were incorrectly categorized.

In summary, we created a high-throughput, near-saturating screen for type III effector genes of P. syringae and corroborated our biological results with bioinformatics analyses. The expeditious nature of our screen enabled thorough screening for type III effector genes, and our isolation of all five hrp promoters from each strain suggests that the screen is probably saturating. Our results with P. syringae pv. tomato and phaseolicola indicate that this method will be useful for identifying entire suites of type III effector genes from diverse pathovars of P. syringae whose genomes have not been sequenced. We have targeted 13 additional strains for analyses based on their phylogenetic relationships (32), maximizing both evolutionary distance among strains and their respective hosts. We envision that comparisons between pathovars will be useful in understanding the function and evolution of type III effectors throughout this species. These findings should be generalized to all pathogens that rely on type III systems to colonize a wide variety of host species.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Brittain Fish and Dr. Han-Suk Kim for technical assistance, Drs. Jurg Schmid and Steve Goff and Syengenta Biotechnology for support, and the members of the J.L.D., S.R.G., and F.M.A. laboratories for their insightful comments. We thank The Institute for Genome Research (TIGR) for providing Pto and Pph6 genomic sequences before publication. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1GM066025 (to J.L.D. and S.R.G.) and RO1GM48707 (to F.M.A.). J.H.C. was funded by National Institutes of Health/National Research Service Award Fellowship F32-GM20296-02S1.

Abbreviations: TTSS, type III secretion system; R, disease resistance; HR, hypersensitive response; Pto, P. syringae pv. tomato race DC3000; Pph6, P. syringae pv. phaseolicola race 6-1448a; Psy, P. syringae pv. syringae; DFI, differential fluorescence induction; Hop, Hrp-dependent outer protein.

Data deposition: Sequences corresponding to genes identified in Pph6 have been deposited in the GenBank database [accession nos. AY803993 (avrB3), AY803994 (hopAT1), AY803995 (hopAU1), AY803996 (hopAV1), AY803997 (hopAW1), and AY803998 (HrpL-regulated gene)].

References

- 1.Bogdanove, A. J., Beer, S. V., Bonas, U., Boucher, C. A., Collmer, A., Coplin, D. L., Cornelis, G. R., Huang, H. C., Hutcheson, S. W., Panopoulos, N. J., et al. (1996) Mol. Microbiol. 20, 681-683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hueck, C. J. (1998) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62, 379-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindgren, P. B., Peet, R. C. & Panapoulos, N. J. (1986) J. Bacteriol. 168, 512-522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dangl, J. L. & Jones, J. D. G. (2001) Nature 411, 826-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiao, Y., Heu, S., Yi, J., Lu, Y. & Hutcheson, S. W. (1994) J. Bacteriol. 176, 1025-1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Innes, R. W., Bent, A. F., Kunkel, B. N., Bisgrove, S. R. & Staskawicz, B. J. (1993) J. Bacteriol. 175, 4859-4869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schechter, L. M., Roberts, K. A., Jamir, Y., Alfano, J. R. & Collmer, A. (2004) J. Bacteriol. 186, 543-555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petnicki-Ocwieja, T., Schneider, D. J., Tam, V. C., Chancey, S. T., Shan, L., Jamir, Y., Schechter, L. M., Janes, M. D., Buell, R., Tang, X., et al. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 7652-7657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guttman, D. S., Vinatzer, B. A., Sarkar, S. F., Ranall, M. V., Kettler, G. & Greenberg, J. T. (2002) Science 295, 1722-1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boch, J., Joardar, V., Gao, L., Robertson, T. L., Lim, M. & Kunkel, B. N. (2002) Mol. Microbiol. 44, 73-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buell, C. R., Joardar, V., Lindeberg, M., Selengut, J., Paulsen, I. T., Gwinn, M. L., Dodson, R. J., Deboy, R. T., Durkin, A. S., Kolonay, J. F., et al. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 10181-10186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zwiesler-Vollick, J., Plovanich-Jones, A. E., Nomura, K., Bandyopadhyay, S., Joardar, V., Kunkel, B. N. & He, S. Y. (2002) Mol. Microbiol. 45, 1207-1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fouts, D. E., Abramovitch, R. B., Alfano, J. R., Baldo, A. M., Buell, C. R., Cartinhour, S., Chatterjee, A. K., D'Ascenzo, M., Gwinn, M. L., Lazarowitz, S. G., et al. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 2275-2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenberg, J. T. & Vinatzer, B. A. (2003) Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6, 20-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collmer, A., Lindeberg, M., Petnicki-Ocwieja, T., Schnieder, D. J. & Alfano, J. R. (2002) Trends Microbiol. 10, 462-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindeberg, M., Stavrinides, J., Chang, J. H., Alfano, J. R., Collmer, A., Dangl, J. L., Greenberg, J. T., Mansfield, J. W. & Guttman, D. S. (2005) Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Valdivia, R. H. & Falkow, S. (1997) Science 277, 2007-2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mudgett, M. & Staskawicz, B. (1999) Mol. Microbiol. 32, 927-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guttman, D. S. & Greenberg, J. T. (2001) Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 14, 145-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huynh, T. V., Dahlbeck, D. & Staskawicz, B. J. (1989) Science 245, 1374-1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newman, J. R. & Fuqua, C. (1999) Gene 227, 197-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kovach, M. E., Elzer, P. H., Hill, D. S., Robertson, G. T., Farris, M. A., Roop, R. M., Jr., & Peterson, K. M. (1995) Gene 166, 175-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cormack, B. P., Valdivia, R. H. & Falkow, S. (1996) Gene 173, 33-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Syn, C. K. & Swarup, S. (2000) Anal. Biochem. 278, 86-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maniatis, T., Fritsch, E. F. & Sambrook, J. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual (Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press, Plainview, NY).

- 26.Mackey, D., Holt, B. F., III, Wiig, A. & Dangl, J. L. (2002) Cell 108, 743-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alfano, J. R., Charkowski, A. O., Deng, W. L., Badel, J. L., Petnicki-Ocwieja, T., van Dijk, K. & Collmer, A. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 4856-4861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamaki, S., Dahlbeck, D., Staskawicz, B. J. & Keen, N. T. (1988) J. Bacteriol. 170, 4846-4854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DebRoy, S., Thilmony, R., Kwack, Y.-B., Nomura, K. & He, S. Y. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 9927-9932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cunnac, S., Occhialini, A., Barberis, P., Boucher, C. & Genin, S. (2004) Mol. Microbiol. 53, 115-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson, R. W., Athanassopoulos, E., Tsiamis, G., Mansfield, J. W., Sesma, A., Arnold, D. L., Gibbon, M. J., Murillo, J., Taylor, J. D. & Vivian, A. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 10875-10880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sawada, H., Suzuki, F., Matsuda, I. & Saitou, N. (1999) J. Mol. Evol. 49, 627-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang, J. H., Goel, A. K., Grant, S. R. & Dangl, J. L. (2004) Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 7, 11-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Espinosa, A. & Alfano, J. R. (2004) Cell Microbiol. 6, 1027-1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rohmer, L., Guttman, D. S. & Dangl, J. L. (2004) Genetics 167, 1341-1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim, J. F., Charkowski, A. O., Alfano, J. R., Collmer, A. & Beer, S. V. (1998) Mol. Plant–Microbe Interact. 11, 1247-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rohmer, L., Kjemtrup, S., Marchesini, P. & Dangl, J. L. (2003) Mol. Microbiol. 47, 1545-1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mackey, D., Belkhadir, Y., Alonso, J. M., Ecker, J. R. & Dangl, J. L. (2003) Cell 112, 379-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ritter, C. & Dangl, J. L. (1996) Plant Cell 8, 251-257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsiamis, G., Mansfield, J. W., Hockenhull, R., Jackson, R. W., Sesma, A., Athanassopoulos, E., Bennett, M. A., Stevens, C., Vivian, A., Taylor, J. D., et al. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 3204-3214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.